Andrew Collins's Blog, page 22

May 3, 2013

Lost in the stupid market

I cannot tell a lie. I chanced upon this blog entry, originally written in August 2011 at the cusp of the UK’s “double-dip” recession, and realised that it is all still true, and all still relevant, which is quite depressing after 18 months of the world turning and money coming in and going out, so please forgive me if I republish it for anyone who missed it, or remembers it. I’m glad I wrote it. (If, at the end of it, you wish to read the 20 or so comments left under it at the time, they’re here.)

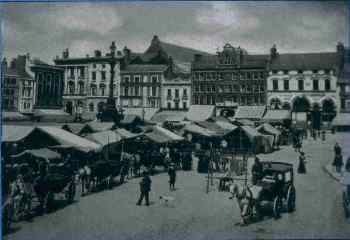

This is a picture of a market. I understand it. On this market, people sell things to other people and the people who sell the things make sure that they sell them for a bit more than they paid for them, so that they can make a profit by which to pay for the opportunity to have a stall on the market and with enough left over to pay for things that they need to buy at other markets. What could be simpler?

This is a picture of a market. I understand it. On this market, people sell things to other people and the people who sell the things make sure that they sell them for a bit more than they paid for them, so that they can make a profit by which to pay for the opportunity to have a stall on the market and with enough left over to pay for things that they need to buy at other markets. What could be simpler?

All the newspapers today are reporting meltdown in the market. But it is a more complicated market. It is the stock market. It is not based upon things being sold, it is based upon the idea of things being sold. It is based upon selling the idea of something. The people who sell these ideas do not meet the people that they sell them to. In fact, most of the selling of ideas is done by third parties, who buy and sell the things that do not exist on behalf of the people who actually own the things, and are paid to do so. Already, this is a more complicated market than the market in the picture.

I am not very good at economics. I understand how much money I’ve got, which is a minus figure, as I owe money to a bank who foolishly lent it to me to buy a house I cannot afford, on the understanding that I will pay the money back to them by a certain date. Unfortunately, I have to pay them back more than the sum they lent me. This is how they make money. I make money by rearranging the English language, mostly by hand, occasionally by mouth, and every month I hope that enough people pay me to do this for me to pay the bank what I owe it for lending me a sum of money. Any money I have left over after paying the bank, I am free to spend on whatever I like, although because I have a house, and a car, there are certain things I have to pay first, to insurance companies and to the council, for instance. It sounds pretty stupid when you lay it out, but I do at least understand it. Once I have bought food and household goods, I might have enough left over to go to the market and buy something nice for myself.

Because I am self-employed, I do not have a boss, and cannot be sacked, but neither do I have any security. Those who pay me today are under no obligation whatsoever to pay me tomorrow, or ever again. Because of this, I tend not to go to the market to buy nice things as often as I’d like. Why? Because there is a recession on.

The recession started in 2007 and really started to get serious in 2008, when house prices fell and people who had been lent more money than they could pay back defaulted on their mortgages, meaning that the whole house of cards came crashing down. The banks and building societies had been lending money for years to people who couldn’t pay it back based upon the idea – another idea – that house prices would just keep going up. They stopped going up and started going down. It turned out that all the countries that thought they were rich and doing well, were only rich and doing well because they expected house prices to keep going up, thereby making everybody richer without actually doing anything. If you watched Property Ladder with Sarah Beeny in the mid-2000s, one thing you knew was that the amateur developers who tried to increase the value of a property but spent too much in doing so by buying stupid taps could have made money by just doing nothing for three months. Because the market went up anyway while they were mucking about with taps.

There was a banking crisis, which I understood, because it was to do with the banks having lent money that wasn’t theirs to people who couldn’t pay it back, so they ran out of money, and the money wasn’t even theirs. It was our money that they had lent to other people. Some people tried to get their money out of the banks but many banks had to be lent money by the government, who used the money we had given them through tax to help the banks. I’m not stupid, but I couldn’t really work this one out. Since 2008-2009, the best thing I could think of doing to beat the recession was spend less of my money. So I did.

There was a banking crisis, which I understood, because it was to do with the banks having lent money that wasn’t theirs to people who couldn’t pay it back, so they ran out of money, and the money wasn’t even theirs. It was our money that they had lent to other people. Some people tried to get their money out of the banks but many banks had to be lent money by the government, who used the money we had given them through tax to help the banks. I’m not stupid, but I couldn’t really work this one out. Since 2008-2009, the best thing I could think of doing to beat the recession was spend less of my money. So I did.

Now, we read the news and find that America, the richest country in the world, cannot afford to pay money back to the people who lend it money. Why is America rich if all its money is borrowed? It is rich because of an idea. The idea is: if everybody works really hard, especially the poor, and if we allow the rich to keep all their money, they will create more money. The stock market deals in ideas. Wealth is an idea. If you do not own the house you live in, your house is an idea. You might own some of it, in that if you ran out of money, you could sell it to pay off the money you still owe, but it’s not yours. Because Greece and Spain and Portugal and Cyprus and Ireland are all in financial trouble based upon an idea – the idea being: all the money we have is borrowed but we might carry on making more money if house prices continue to go up – there are fears that the Eurozone will collapse.

As I believe I’ve mentioned, I’m not very good at economics, but I know that the single currency for some but not all European nations was introduced so that money could be simpler. Instead of lots of currencies which have to be exchanged all the time, some but not all European countries would have the same currency, which would make trading between some but not all European countries easier, and fairer. However, this Utopian ideal seems to be in trouble. Because Greece, which doesn’t really make anything, or Ireland, which doesn’t really make anything, or Spain, which doesn’t really make anything, built the idea of their wealth upon the idea that house prices would continue to go up, and they have gone down, almost an entire continent using the same currency seems to be in more trouble than it might have been if it still had lots of different currencies.

I love Ireland. It is my favourite country. I have been there a lot, and regularly, over the past 20 years. It used to be a small, modest, rural economy, self-sufficient, surrounded by water, and with enough tourism to give it a bit of spare money to buy nice things at a market. It joined the EU, became eligible for all sorts of grants and funding, and built better roads. These were really good roads, and they joined the place up a bit. Having joined the Euro, Ireland started advertising itself as a great place for foreign businesses to move to. So lots of foreign businesses did indeed move there, as rent was low, tax was low, services were almost free, and labour was cheap. And money came in. And Ireland started building houses, which people who couldn’t afford them borrowed money to buy. And people from other countries moved to Ireland to work for the businesses, and rented houses from landlords who had bought too many houses. Then, when it stopped being a good place for foreign businesses to be based in, the employers and many of the employees moved out again, to find a cheaper place to work and be based in, and Ireland’s wealth, based on an idea, disappeared. This is how quickly ideas can disappear. Now the people of Ireland are moving out, which means less tax, and tax is not an idea, it is real. This is why U2 moved their business to Holland. This is what happens if you have actual money. You move it to where people can’t get at it. (This involves not caring about the country you are moving it from, which U2 clearly don’t.)

I love Ireland. It is my favourite country. I have been there a lot, and regularly, over the past 20 years. It used to be a small, modest, rural economy, self-sufficient, surrounded by water, and with enough tourism to give it a bit of spare money to buy nice things at a market. It joined the EU, became eligible for all sorts of grants and funding, and built better roads. These were really good roads, and they joined the place up a bit. Having joined the Euro, Ireland started advertising itself as a great place for foreign businesses to move to. So lots of foreign businesses did indeed move there, as rent was low, tax was low, services were almost free, and labour was cheap. And money came in. And Ireland started building houses, which people who couldn’t afford them borrowed money to buy. And people from other countries moved to Ireland to work for the businesses, and rented houses from landlords who had bought too many houses. Then, when it stopped being a good place for foreign businesses to be based in, the employers and many of the employees moved out again, to find a cheaper place to work and be based in, and Ireland’s wealth, based on an idea, disappeared. This is how quickly ideas can disappear. Now the people of Ireland are moving out, which means less tax, and tax is not an idea, it is real. This is why U2 moved their business to Holland. This is what happens if you have actual money. You move it to where people can’t get at it. (This involves not caring about the country you are moving it from, which U2 clearly don’t.)

If the current “whichever-dip” recession tells us anything about wealth is that it is only real for the wealthy. The rest of us might feel wealthy because we have credit cards and big tellies, but we are just as poor as we were when we didn’t have them. Men in stock markets are moving money that doesn’t exist around a huge, global market, and it’s not our money, and yet the success or failure of the men who move it around affects us all. Why? Because global meltdown affects the amount of extra tax we are expected to pay on goods, and the amount of interest we have to pay the institutions who lent us money we can’t afford to pay back.

If the current “whichever-dip” recession tells us anything about wealth is that it is only real for the wealthy. The rest of us might feel wealthy because we have credit cards and big tellies, but we are just as poor as we were when we didn’t have them. Men in stock markets are moving money that doesn’t exist around a huge, global market, and it’s not our money, and yet the success or failure of the men who move it around affects us all. Why? Because global meltdown affects the amount of extra tax we are expected to pay on goods, and the amount of interest we have to pay the institutions who lent us money we can’t afford to pay back.

The previous government in this country ran it on the basis of an idea, and that idea turned out to be a bad idea. They spent all our money, which was not even money we had in the first place, and then borrowed against money we had not yet paid them to save the banks which had lost all of our money. Luckily, this money didn’t exist, so in a way, we had lost nothing, but we had lost nothing twice. Does that sound ridiculous? It should do. The current government didn’t actually lose our money as they weren’t in power when it was lost, but they have decided that the best way to pay it off is to put quite a lot of us out of work, so that employers won’t have to pay us. But when we are out of work, other people who are in work have to pay us not to be in work, and it’s not very much money, so we can’t afford to go to the market and buy nice things, which cost more because the government have put up tax on nice things in order to pay themselves back for losing all our money, twice.

The bad thing about our government is that is that it is run by men who are rich. They were rich before they went into politics and don’t know what it is like to be poor. (Poor being what nearly all of us are, in reality.) So they have come up with a Plan A that protects people who are rich, but hurts people who are poor. It is a shit plan.

If you are actually rich – in other words, you own the house you live in, something only the rich actually do – you can pay people to prevent you from having to pay the government what you owe them in tax. This is a luxury only the rich can afford. So the rich, the very people who should be paying tax, don’t pay it. While the poor, which is nearly everybody else, pays tax that it can’t afford, but can’t afford not to pay. This is also an idea. This idea is called capitalism.

So all these sweaty men in coloured jackets and on phones we keep seeing on the news – who are, at the end of the day, just men with jobs they could lose as quickly as you could lose yours – are the most powerful men in the world, but unlike the people who work on the market in the picture above, they don’t have anything to sell. They don’t even have a stall. If you went up to the desk and tried to pay for the idea that they trade in with cash, they wouldn’t have anywhere to put the cash, and you wouldn’t have anything to show for it.

I wish the cakes weren’t so pricy in the British Library. But the British Library, which is a public service, pays a private company to make and sell its cakes. This is not a market, as there is only one place to buy cakes inside the Library.

Raymond reviews: bah!

Well, I went in to see The Look Of Love with expectations at ankle-height thanks to all the below-par reviews, which ran the gamut from lukewarm to cold-shower, enough to give anyone a winter bottom. A straightforward biopic of Soho porn baron and property magnate Paul Raymond, built, or so it seemed, around Steve Coogan’s desire to impersonate him (which he does well), and regular collaborator Michael Winterbottom’s desire to capture to pre-enlightenment days of London’s former sex district, The Look Of Love turned out to be very good.

Maybe the critics turned on it because it seemed to arrive rather engorged with self-confidence, as if asking to be pulled down a peg or two. (The string of TV comedy cameos – David Walliams, Matt Lucas, Miles Jupp, Stephen Fry – may have added to the perceived smugness.) Both Coogan and Winterbottom are prolific, and much admired, so it’s easy to knock them while celebrating their other triumphs. So, too, with screenwriter Matt Greenhalgh, who wrote Control, which was feted across the board and given a Bafta, and Nowhere Boy. I actually wondered if I was going to love it after seeing the trailer; it had the hallmarks of being “perfunctory”, as many reviewers maintain that it is. I respectfully disagree with them all.

Aside from David Sexton’s virtual lone voice of praise in the London Evening Standard (well, it is a very “London” film), few could even strain up to a three-star rating. Philip French of the Observer called it “crude”, “shallow” and complained that Raymond’s world and life lacked illumination by a “larger social context”. He also said it lacked “wit … insight and … detail”. Our own Stella Papamichael in Radio Times named Winterbottom “a co-conspirator in Raymond’s objectification of women.” Emma Jones in the Independent reported from Sundance, saying it “lacked soul” and calling it “an interminably dull orgy”, but at least recognised that this was probably Winterbottom’s intention. Tim Robey in the Telegraph, another trustworthy critic, used the words “perfunctory” and “hollow”, not to mention “flaccid”, and wondered aloud what Scorsese would have made of it. (Again, he’s clever enough to spot that a British porn baron’s tale is never going to have the crackle of Boogie Nights or Larry Flynt.) The Mail‘s Chris Tookey stamped it a “turkey” and called it “unobservant, unerotic and dull,” and went further with “dishonest”. Though only awarding three stars, Empire at least identified its “healthy sense of naffness.”

Maybe that’s the problem, although not a problem for me: it does not make apologies for Raymond, as he rises from “entertainer” to impressario, and makes his money through property and pornography. He is plainly depicted as a cad and a sexual cheat, unfaithful in a sort of industrial manner to his first wife (Anna Friel) and his live-in girlfriend Fiona Richmond (a frequently nude Tamsin Egerton) by decree. Yes, he took a showgirl for his wife. Greenhalgh’s script presents Raymond as a man of natural charisma and wit, but doesn’t deify him; he made his living in a sleazy business in what was a sleazy part of town (“welcome to my world of erotica”), using tits to put bums on seats in theatrical sex farce and disrobed revue alike, always pushing against the boundaries of what the Lord Chamberlain allowed.

If he was any part of a libertarian or champion of free artistic impression, this is soon eclipsed by his greed for more flesh as he buys into Men Only (whose coke-snorting editor, Tony Power, is skilfully played by Chris Addison, for whom The Look Of Love may provide a more fruitful shopfront than it ever could for the better-established Coogan, whose Raymond does brings to mind an X-rated combination of Partridge and, as per The Trip, Coogan). It’s grubby stuff, mostly, with any glamour tarnished by a combination of 60s and especially 70s naffness (the space-age telly watched by the almost-beaten 90s Raymond after his daughter’s sad death, brilliantly encapsulates the datedness of that metropolitan notion of James Bond cool that only James Bond could pull off).

In terms of the randy threesomes and the magnetic pull of the shag-pile boudoir, you get the sense that Coogan understands this self-destructive cock-led compulsion. The constant refrain of “house champagne” is a nifty way of exposing the cheapness beneath the largesse. (Raymond does keep insisting he’s the boy from Liverpool who arrived in London with “three bob” in his pocket.) If anything, on occasion, Coogan possibly makes Raymond too amusing and suave, in what must be improvised scenes, including impressions of Brando and Connery. (Maybe he was an excellent mimic, but I doubt as adept as Coogan!)

It’s not life-changing. It is, deliberately, unerotic. And it doesn’t tell us anything new about the history of porn, which was done with more seriousness when Our Friends In The North ventured down south. But at least, for all the flesh on display – including a 70s-appropriate bush of pubic hair that’s foregrounded purely for reasons of nostalgia! – it features a strong, driven, successful woman in Richmond, through whom Egerton rises above the exploitation of her own body and compensates for all the insipid, giggling dollybirds, as they used to be called.

If it has anything to say, it’s that a vast property portfolio, enough money and assets to be named the richest man in Britain at his peak (and before the foreign money took over), doesn’t bring happiness. You’ll still be trying to impress people by telling them that Ringo Starr designed your flat (which Raymond does), and measuring your worth via notches on the bedpost. Raymond ends the film sad and introspective, and minus his beloved daughter (Imogen Poots, who steals much of the film with her rounded, likeable, unspoilt portrayal of a beneficiary of nepotism who rose above it, only to fall victim to cocaine and heroin abuse).

It may sound glib to say it’s a bit of fun, but there’s nothing wrong with that. Winterbottom shoots on the hoof, keeping budgets low, on location (Londoners will love, as I did, the sightseeing aspect), and encourages improv, and while Raymond’s story doesn’t have the innate cool or bangin’ soundtrack of 24 Hour Party People, he may happily file The Look Of Love alongside: a breezy portrait of an essentially naff English success story who charmed his way through a number of scams and left his mark. It’s a bit of a useless title, and it’s a pity Ramond’s estate owned the rights to its intended one, The King Of Soho. What about 24 Hour Porno Person?

May 1, 2013

Orange is not the only suit

Guantánamo Bay is a prison. They might call it a “detention camp”, or a “facility”, but it’s a prison, in Cuba, where people are held, and have been held since January 2002, during the panic after 9/11. It exists outside of US legal jurisdiction. The plan, under “war president” George W. Bush, was for it to operate outside of the tiresome Geneva Conventions, which held until 2006, when the Supreme Court ruined everything by conceding rights to certain protections under Article 3 (which offers “persons not taking active part in hostilities” immunity from various “outrages upon personal dignity” and “judicial guarantees … recognized as indispensable by civilised peoples”).

Amnesty International named Guantánamo a “gulag.” In January 2009, President Barack Obama promised to shut the ghoulish, lawless place down “within the year.” Historians will note that this promise was not fulfilled. Admittedly, this is mainly because a Republican congress blocked it, as it has successfully blocked anything approaching a commonsense debate or ruling since Obama was sworn in.

At a press conference in Washington this week, surely politically engorged by now in his second term, Obama said it was “not sustainable” to keep Guantánamo open. Never mind that it’s an international embarrassment, an insult to all of our freedoms, and a permanent stain on the United States’ standing in the world, that’s not enough of a sell. He had to resort to scare tactics (which is ironic, considering how much fear of fear itself lies at the heart of Guantánamo’s “open for business” status), warning that the gulag’s continued existence was a “recruitment tool” for extremists. So its effect on extremists who are not in the prison is the best reason for releasing those largely unconvicted, uncharged prisoners who are in it.

There are around 160 detainees still inside, rocking the orange jumpsuit of 21st century iconography. Many are now on hunger strike and of those 100 or so, 21 are being force fed. The main effort there currently is to keep its inmates alive. After ten years of institutionalised, unpoliced torture and outrages upon human dignity, it seems like small beer that the prisoners’ protest began over allegations that guards mistreated Qur’ans, rather than human beings, although torture comes in many and various forms, including psychological, emotional, religious and material.

Never mind that the so-called “terror suspects” have not been charged with anything, half of them have been cleared for release. (Only five – five – have gone to trial.) So why are they all still there? It is an outrage. Obama has once again promised to shut it down. Why should we believe him? (And I speak as a non-American who totally bought into the “HOPE” he peddled in 2008.) “I am going to get my team to review everything that is currently being done in Guantánamo,” he said in that press conference, which is a bit like someone you’ve complained to on the phone telling you they will “escalate the issue” and give you a “ticket number”. There’s not much he can promise, I guess, other than to act “administratively” (the government is an administration), but how about acting “physically”? Just going down there and opening the gates, with a few helicopters waiting?

You may same I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. “I don’t want these individuals to die,” Obama said. Good. Guards are said to have attempted to “break the resolve” of the hunger strikers by moving them to single cells, for ease of monitoring. So they’re in solitary? That’s nice. Some of them have been there for the full 11 years, while the world turned without them, and their families started to forget what they looked like.

The Boston “terror attack” – a horrible tragedy whose attendant local and national panic led to some uneasy flag-waving triumphalism when one of the alleged perpetrators was dead, the other unable to speak in hospital – has put “terror suspects” back in the spotlight. But nobody’s rounding up Chechnyan immigrants and sending them in hoods to Cuba past the big sign reading, “You are now leaving US legal jurisdiction, have a nice stay!” So some progress has been made since the dark, dismal days of Bush.

But still Obama will need to win congressional support In order to close Guantánamo and release its inmates. He may not be able to pull it off, but if he doesn’t, it will be a stain on his presidency too. It’s easy for Americans, he said, to “demagogue the issue.” He’s an eloquent, persuasive president, liberal on the whole if not in totality, but if he can’t condemn this unsafe building, who the hell ever will?

According to the Guardian, which penned a stirring leader on the subject today (“An Indelible Stain”), the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union said, “The president can order the secretary of defense to start certifying for transfer detainees who have been cleared, which is more than half the Guantánamo population.” The video of the press conference is here. I say: get to it.

Reprieve, the charity that makes this kind of thing its calling, provides an excellent Guantánamo timeline here.

The world at war

Two films at the weekend which I intend to line up for arbitrary comparison because they are both new, both are foreign language and both were premiered at Cannes last year, where they competed in parallel for the Palme d’Or and Un Certain Regard: from Russia, In The Fog, or В тумане, and from Argentina, White Elephant or Elefante blanco.

They formed a sublime, if challenging and counterintuitive double-bill for me at the Renoir, a subterranean refuge from a sunny Sunday afternoon in London’s Bloomsbury. A barbecue and a beer are not the only ways to celebrate the late arrival of spring; you can retreat underground, on your own, and immerse yourself in Russian and South American poverty. Each to their own!

In The Fog first, a long and courageously ponderous fable set in Nazi-occupied Belarus during the Second World War; 1942, to be precise, where the hanging of three partisans sets the scene in an apparently unbroken tracking shot that discreetly turns away from the moment of death and alights upon a cart piled high with bones instead (animal bones, but you get the idea). Such is the skill and precision of relatively new Belarusian feature director Sergei Loznitsa announced. He previously worked on documentaries, but despite the handheld opening, do not expect a story built with the improvised looseness of photojournalism. In The Fog is in many ways a formal piece, in which three central characters move slowly through the forest, their individual backstories illustrated in flashback.

Not much happens. In this regard, I couldn’t help but think of Waiting For Godot. The three main characters seem also to be archetypes, the central protagonist, Sushenya, played by Vladimir Svirskiy, a stoically noble and fatalistic embodiment of the Russian spirit, perhaps. (I am no student of Russian classical literature – this film was based on a 1989 novel by Vasil’ Bykaw – but I’ve seen the films, and I get a sense of the ideological and political forces that shape the national temperament, particularly in times of war or struggle.) There are few laughs to be had – alright, none – this is a fable of death and punishment and separation and hardship. An early scene has one partisan emptying his boots of water and squeezing out his sodden socks, which seems to sum the film up.

Sushenya’s wife, from whose comfort he is taken early on in the film (he also leaves behind the carved wooden animals he made for his young son and the warm bathwater), begs him to take food when he is called in for questioning by two partisans after a fatal misunderstanding. She suggests some lard, or an onion (“Everything tastes better with an onion”); again, this sets the tone of humility and gratitude for only the bare basics of subsistence living in occupied Belarus. It’s hard going. Between the occasional bursts of action, it’s largely men in hats murmuring in a forest. But it feels oddly poetic and certainly measured and sincere, and although the Nazi occupiers are clearly the “baddies”, the internecine conflicts between partisans and collaborators make it morally ambiguous. My favourite kind of cinematic morality.

For the far more conventional but no less stimulating White Elephant, writer-producer-director Pablo Trapero, who made last year’s memorable ambulance-chasing thriller Carancho (released in Argentina in 2010 but released here last year, and also Cannes-selected), returns to Buenos Aires and to the two excellent stars of that film for a more socially conscious piece about “slum priests”. Ricardo Darín, a big star at home and familiar to international audiences from Nine Queens and The Secrets In Their Eyes, is a likeably crumpled presence with a twinkle in his eyes, here playing what we would call a “community leader” in a shanty town that has grown, like mould, around an abandoned hospital project. (I think I’m right in saying that this is the Ciudad Oculta in real life – it’s clearly a genuine location and the shell of a hospital makes a striking image throughout, a hollowed-out symbol of civic failure and economic collapse – instead of making people better, it houses self-destructive drug addicts.)

We first meet Darín’s Father Julián, a selfless, tireless beacon of commonsense and charity among the dispossessed who live in the slum, when he fetches the younger, Belgian priest, Fr Nicolás (Jérémie Renier) back from a horrific paramilitary massacre at a jungle mission. His own mission is to train up the junior to eventually take his place. It’s a nice touch to show the real-life memorial to Fr Carlos Mujica, shot – and martyred – in 1974; his sanctified spirit lives in Julián, although he cannot perform miracles and make the inevitable drug war go away.

If you’ve seen the Brazilian film City Of God, set in Rio, you’ll know the fatal, bullet-riddled milieu and will not be surprised to see young kids at the centre of it. One school-age addict, Monito (Federico Barga), forms a focus for the priests’ efforts to stem the body count, although their techniques differ: the older priest wants to stay out of the politics of the drug trade, the younger wants to get his hands dirty. Disaster this way comes.

I won’t reveal too much of the plot. The director’s wife and co-producer, Martina Gusman, who was so vital as the flawed emergency-room doctor in Carancho, plays a dedicated but non-Catholic social worker trying to get new housing built, a key player in the conflict between the priests. White Elephant has the same liberal, do-gooder feel as any number of white British or American films about aid workers in Africa, but without the colonial guilt. These slums are local problems on the doorstep of Buenos Aires, and there is something terribly old-fashioned about the Church having to solve society’s ills. The easy banter of the volunteers, and the law-abiding citizens (many of whom must be non-actors) stops it being too earnest or grim, although the conclusion feels a little bit Hollywood.

Still, another important glimpse of life during wartime.

April 30, 2013

Cheers!

So, we’ve reached 100 and nobody’s taken us off the air yet. This is the centennial of Telly Addict. I wrote and read out the first one in May 2011, and have done so pretty much every week (except occasional public holidays and the week I had off when the insanely ambitious Stuart Heritage siezed his opportunity) ever since, for 100 weeks in total, not including the Bake Off special I did at Christmas. That’s a lot of first episodes of a lot of TV programmes that I never watched again, assessed in a pithy and I hope lenient manner while sat at a diagonal from the camera, straining at the Autocue, and taking care to rotate my shirts so that the same one doesn’t appear more often than once every six weeks. (Don’t go back and check, nerds, as I’m more vigilant on this score now than I started out being, and anyway, a lot of those black shirts are different black shirts.)

So, we’ve reached 100 and nobody’s taken us off the air yet. This is the centennial of Telly Addict. I wrote and read out the first one in May 2011, and have done so pretty much every week (except occasional public holidays and the week I had off when the insanely ambitious Stuart Heritage siezed his opportunity) ever since, for 100 weeks in total, not including the Bake Off special I did at Christmas. That’s a lot of first episodes of a lot of TV programmes that I never watched again, assessed in a pithy and I hope lenient manner while sat at a diagonal from the camera, straining at the Autocue, and taking care to rotate my shirts so that the same one doesn’t appear more often than once every six weeks. (Don’t go back and check, nerds, as I’m more vigilant on this score now than I started out being, and anyway, a lot of those black shirts are different black shirts.)

The big celebration is just a normal Telly Addict, except with a rare clip from one of the first shows I reviewed, which I feel sure you’ve all forgotten, Exile on BBC1. From the modern day: the final moments of Broadchurch on ITV; The Politician’s Husband on BBC1; The Wright Way on BBC2; Playhouse Presents: Snodgrass on Sky Arts; Masterchef on BBC1; and a couple of quick nods to Mad Men, and Da Vinci’s Demons.

Cheers!

April 26, 2013

Writer’s blog: Week 18, Friday

A quick bulletin from my daily life. It is the end of the working week, Friday, although I gave myself a day off on Tuesday, as I worked on Sunday. As usual, the lack of blog entries reflects the urgency of the work I should, by rights, be doing. (I should be doing it now. As you’ll have spotted, I’m not. I’m in the coffee shop of a department store where I have come to buy a bag.)

Without giving anything away, I’ve been hard at a pilot script these past couple of weeks for a terrestrial broadcaster, via an independent production company with whom I’ve worked before. I think I’ll go out on a limb and say that it’s a comedy, based on an idea I had in an office when I was in a meeting to pitch ideas but had no ideas that I hadn’t already pitched, so I sort of improvised one and it turned out to be a goer. Fancy that! I’ve stated this for the record before, but some people still don’t seem to know, so I’ll say it again: I no longer write for Not Going Out, which is enjoying its sixth series on BBC1 currently, and although I wish it well, I find it odd to watch it now for personal reasons. The last episode I co-wrote was Debbie for series four, after which the writing team was streamlined down to a number that didn’t include me. (I’m still friends with Lee; he was kind enough to namecheck me on The One Show the other week.)

The reason I bring it up, is because as much as I will be forever grateful to Not Going Out for giving me the chance to write a broad, studio-based audience sitcom for BBC1, and to work on it from the ground floor up, what it made me want more than anything was to write a sitcom on my own. Now, I’ve done that for radio with Mr Blue Sky, which is now cancelled, and I’m rather hoping that one of the three – count ‘em – three pilots I currently have in development will catch fire and get a full commission. This latest one feels like the most likely. As I mentioned on Twitter, teasingly, the script today required me to “research” (ie. look up on the Internet) a number of seemingly random subject areas which included:

England-Scotland Home International games

Job vacancies and job descriptions at a local council (for which I happened upon the website of Essex County Council)

Progressive rock lyrics that mention “time” (for which I alighted, happily, upon the Marillion song Wrapped Up In Time)

My online history would certainly baffle future archaeologists, I like to think. And I’m afraid it will have to baffle you, as I can say no more about it. Writing comedy is hard. It is not the hardest job in the world, and would in fact not make the Top 100, but when you have decided that your best chance of earning a decent living is to write scripts, I would argue that writing comedy scripts is harder than writing drama. Which is why I dream of writing drama and not have to think of jokes.

Talking of comedy, a smart black, leather shoulder bag I bought almost a year ago to the day stopped working the week before last, when two of its zips went. I tried to get it mended, first of all, but neither of the menders I visited could fix a zip on a leather bag. But having ascertained that the bag – quite a pricey one for miserly old me – was under a year old, I decided to take it back to the shop. I really liked the bag and was sad that it had become inoperable. The man in the shop, a department store, was very helpful and took the bag from me to send to the manufacturers to be repaired or replaced. I left the shop with a spring in my step; he had by definition agreed with me that an expensive bag’s zips shouldn’t break within a year, so I felt vindicated.

However, he called me back when I was on the train home and told me that the manufacturers could neither repair nor replace the bag, as they no longer sold that particular model. I was sad again. The store offered me a credit note which I could spend on another, similar bag. I looked at the bags and didn’t like any of them as much as the one I’d had for almost a year. So I asked, firmly, for a refund, not a credit note, and again, no resistance was offered.

I won’t mention the make or the shop, in case it looks like an invitation to exploit their decency. But when you go into a shop with a complaint you go in having rehearsed all the arguments first. When you don’t need those arguments, it’s almost a letdown. But isn’t it nice to get good service occasionally, when most commercial outlets seem to be out to fleece and humiliate you if you rock the boat? The blue bag in the picture above has become my temporary shoulder bag. As you can see, it looks cheap and cheerful, has no special pockets and gives me the air of a schoolboy on a games day. It also says “BADULTS” on it. This is the new, official name for the Pappy’s sitcom I script edited, and which airs on BBC3 in July. The bag – a free, promotional gift of the type I rarely get sent any more – couldn’t have arrived at a more convenient time.

The great thing is, I was carrying it when I went to see Spring Breakers at the Curzon Soho one afternoon last week, and who did I bump into, in the gents? Matthew Crosby of Pappy’s! Not only was he going to see the same matinee of the same film as me, so we could sit together like pals, but he was carrying a red BADULTS bag. Sometimes life is planned out for you by a higher power who can’t be God as God doesn’t exist, but there’s something out there pulling the strings.

In case you’re interested, I am reading a bracing non-fiction book called Going South by the Guardian‘s economics editor and his friend Dan Atkinson, who is the Mail On Sunday‘s economics editor. (As literary aside: I had a meeting at a production company two weeks ago where the head of development I was pitching to recommended a George Orwell book called Coming Up For Air, which I’m looking for a secondhand copy of presently.) Going South is explained by its subtitle: Why Britain Will Have A Third World Economy By 2014. Although I am a bit shot on economics, I’ve been educating myself on this vital area of all our lives – not least by reading the Guardian‘s correspondents, and the New Yorker‘s unstoppably readable James Surowiecki. Elliott and Atkinson paint compelling if gloomy pictures of political, social and financial life in Britain today – in that sense, it’s a kind of self-hating book, but I like those.

I was particularly taken with a passage about the attitude to a car alarm going off. They write that the “common occurrence of the ignored wailing of the car alarm” encapsulates much of what’s up with our society. The alarm is ignored “partly because it is assumed it is sounding in error; partly because, even if the car is actually being stolen, no call to the police is thought likely to produce much in the way of response; and partly because any attempt to confront the suspected car thief immediately puts the citizen in danger.” They conclude that ignoring the alarm is “an entirely rational response to the way the world works.” How depressing, and true, that is.

I am reminded of “broken window theory”, which I first read about in The Tipping Point (how quaint and gradual the examples in that book now seem in the age of YouTube and Twitter). Basically: if a broken window is left broken, it will lead to a decline in the area where the building is, and to worse crime. So fix the window. Here’s the passage from the original 1982 Atlantic Monthly article where the theory was first aired by two criminologists:

Consider a building with a few broken windows. If the windows are not repaired, the tendency is for vandals to break a few more windows. Eventually, they may even break into the building, and if it’s unoccupied, perhaps become squatters or light fires inside. Or consider a sidewalk. Some litter accumulates. Soon, more litter accumulates. Eventually, people even start leaving bags of trash from take-out restaurants there or even break into cars.

I think of this theory often, when I see bags of rubbish left outside charity shops overnight, or on weekends when the shop is closed, or when I see an empty shampoo bottle left on the floor of the showers at my gym, just dropped there by a previous occupant as if perhaps their mum will be round later to pick it up after them. If we don’t pick up our own detritus, we may not complain when crime occurs on our doorstep.

I saw a preview of Iron Man 3 in 3D last Wednesday but reviews were embargoed until this Wednesday. I think it’s pretty good, considering it’s the third part of a franchise – and when Iron Man has been seen in the Avengers movie, too. I still hate 3D, but the film itself, under new management with Shane Black at the helm (he co-wrote it with a British writer Drew Pearce, who wrote No Heroics for ITV2, which just shows that dreams can come true), has a certain wit and verve, and its story is one where all that has been built in the previous two films is destroyed, literally, to bring Iron Man back to basics – and then allow him to defeat the baddie in an even more spectacular way at the end of course. It’s a shame that Gwyneth Paltrow’s character, who is now a CEO of Iron Man’s company, becomes little more than a standard damsel in distress in the end. This happens to Rosamund Pike’s assistant DA in Jack Reacher, which is out on DVD.

Compared to Jack Reacher, which starts promisingly and collapses into boring gunplay and car chases by the end, at least Iron Man 3 has the common decency to sag in the middle and then improve for the climax. And I can’t say why, as it’s a spoiler, but there’s a scene with Ben Kingsley which is almost worth the price of admission alone. That’s all I’m saying.

Have a nice weekend. (It’s been sunny, hasn’t it? I’ve actually worn a soft M&S jacket rather than a big M&S waterproof coat four times this week. I give thanks for the belated arrival of spring. I much prefer not to look like Liam Gallagher between my neck and my knees, but practicality dictates. Not that he’d be seen dead in M&S.)

April 23, 2013

Glock holiday

Spring Breakers, the new sensation from Harmony Korine of Kids, Gummo and Trash Humpers infamy, reminds us once again how different American youth culture is from our own, no matter how hegemonic and irresistible its occupation feels, as our defences fall like pathetic dominoes before exported concepts like prom night, seasons, sweet sixteens, EDM, “Can I get …?” and local elections for police chiefs. Lord, save us from Spring Break. Were this film to be set in this country – or in Ayia Napa, Ibiza or whatever latest fleshpot British sixth-formers and gap-yearers flock to for sun, sex and sexually transmitted disease – it would be called The Easter Holidays. Not quite as alluring, is it?

The very phrase, “Spring Break … Spring Break,” is uttered again and again through Spring Breakers like a mantra, as if it’s Mecca or Oz calling, as opposed to Florida. The film, whose sense of occasion is never in doubt, even if its motives are, depicts a beach babe bingo Bacchanalia, the kind seen in rap videos, or, these days, cameraphone footage, where arse-cellulite vibrates to booming bass, liquid refreshment is siphoned through rubber tubes or simply applied to the skin, and flesh is fancifully fried like a human barbecue. It’s Club 18-30 without a rep in sight.

I have never been on a holiday like this. But you have to hand it to Korine, who’s 40 now: he “gets” what goes on away from prying parental eyes between the second and third semester, and it looks for all the world like the one captured in The Inbetweeners Movie, except without the bidet jokes and the failure to score drugs or have sex.

The music – “Electronic Dance Music” or EDM, the umbrella term over there for house, techno and/or dubstep, so it seems – is key, as it doesn’t just soundtrack these adventures in the skin trade, it provides the pounding, pulsing rhythm of their all-out, non-stop, heads-down hedonism. During their Easter hols, pleasure is their guiding principle and nothing else. If that pleasure might require danger to spice it – cocaine, armed robbery, drive-bys, premeditated murder – so be it. A quick call home to Mom and Dad will cover the cracks. (The wilder this vacation gets, the more demure, innocent and spiritual the calls home become.)

The girls whose story is told in Spring Breakers are played by previously wholesome Mouseketeer types – inspired casting, if you know their CVs, which I’m afraid I didn’t – Candy is Vanessa Hudgens, previously known for High School Musical, Brit is Ashley Benson from Days Of Our Lives, Cotty is the director’s wife Rachel, whose background is less apple-pie, and Faith is Selina Gomez, as famous for being the ex of “the famous pop singer who likes Anne Frank” as being in Disney’s Wizards Of Waverly Place. They are spring broke at the end of term and are forced to rob a Chicken Shack to afford the trip to Tampa, where the action is.

I’m no student of Korine’s work, but I understand that this is being marketed as his most accessible film. It certainly may appeal on a base level to – presumably – the spring breakers whose hedonism it surely seeks to satirise and critique. I certainly felt, at the outset – and the film is a compelling riot of colour, music and movement – that we were in for a debunking of the moral and intellectual vacuum occupied by moneyed American teens. When the film takes its inevitable darker turn – when the Miami PD turn up, basically – and this particularly thin American dream morphs into a nightmare, I thought I knew what was going on.

But, without giving away the plot (such as it is; Spring Breakers feels like a dream sequence unmoored from hard reality come the final reel), Korine winds up complicit in MTV-gangsta-rap fantasies.There may be a price to pay for earlier pleasure-seeking, but there is little redemption or comeuppance.

Although full of flesh, and dictated by a rhythm of grinding hips and bottoms, it’s not as sexually explicit as you might expect, and Selina Gomez, in particular, does not do as much to shock or scorch her own image, as, say, Benson or Hudgens, but as far as you can tell, very little actual sex takes places. Maybe this is a comment? That the lifestyle is all bump and grind and no sexual congress?

If the film is a comment upon “Spring Break” itself, I would argue that, in the end, it’s not much of one. In its favour, it is visually splendid, however, all bright pinks and pastel oranges (and that’s just the skin tones etc.), and runs on a pretty persuasive energy. And James Franco is, as well as unrecognisable, thrilling in the main male role of silver-toothed charmer Alien, a drug dealer who manages to be appealing as well as repellent. His “Look at my shit!” speech, surely improvised by Franco, is a highlight of the film.

Korean opportunities

What interesting connections we can make on this week’s telly on Telly Addict. Brushing Up On … British Tunnels with Danny Baker on BBC4 is essentially a middle-aged man reading out words he has written between some archive clips; Oliver Stone’s Untold History of the United States on Sky Atlantic (from Showtime in the US) is essentially a middle-aged man reading out words he has written between some archive clips; in Panorama: North Korea Undercover, easily the most talked about TV show of last week, reporter John Sweeney attempts, as does Stone, to get under the skin of a country whose propaganda is all-powerful (and in both cases, Stone and Sweeney risk excommunication from the nation which they criticise); 30 Rock‘s Season 6 finale, on Comedy Central, includes jokes – aired in May 2012 on NBC – about the totalitarian quirks of the North Korean regime; Modern Family, an imported US comedy not given to inter-textual cross-media jokes that are the stock-in-trade of 30 Rock, tries one on for size with a coda based on The Godfather on Sky1; and I also review new ITV three-parter The Ice Cream Girls, which has no link whatsoever with the other shows. Ah well. You can’t join everything up.

What interesting connections we can make on this week’s telly on Telly Addict. Brushing Up On … British Tunnels with Danny Baker on BBC4 is essentially a middle-aged man reading out words he has written between some archive clips; Oliver Stone’s Untold History of the United States on Sky Atlantic (from Showtime in the US) is essentially a middle-aged man reading out words he has written between some archive clips; in Panorama: North Korea Undercover, easily the most talked about TV show of last week, reporter John Sweeney attempts, as does Stone, to get under the skin of a country whose propaganda is all-powerful (and in both cases, Stone and Sweeney risk excommunication from the nation which they criticise); 30 Rock‘s Season 6 finale, on Comedy Central, includes jokes – aired in May 2012 on NBC – about the totalitarian quirks of the North Korean regime; Modern Family, an imported US comedy not given to inter-textual cross-media jokes that are the stock-in-trade of 30 Rock, tries one on for size with a coda based on The Godfather on Sky1; and I also review new ITV three-parter The Ice Cream Girls, which has no link whatsoever with the other shows. Ah well. You can’t join everything up.

April 17, 2013

A few sentences

To the National Theatre on London’s South Bank on the first balmy evening of 2013 for an event laid on by the actor David Morrissey (who I can’t pretend I haven’t recently befriended) and his wife, the writer Esther Freud, to promote the good works of the charity Reprieve. I’m not really used to these things, but the idea is to assemble a roomful of media and arts folk who find a social hard to resist and shamelessly talk up a charity with a view to either financial assistance, or some other payment in kind. I consider myself neither a mover nor a shaker, but the guest list turned out to include one or two affable giants of comedy whom I have the pleasure to know – Al Murray, Sean Hughes – as well as other familiar faces like Simon Mayo, Tracey MacLeod and James Brown, so the terror of walking into a room on my own was quickly salved.

(I’m hoping for some official celeb-filled photos, which will jolly this blog entry up no end. Also present: Olivia Colman, Polly Harvey, Peter Capaldi, Sam West, Tom Goodman-Hill, Sinead Cusack, Stephen Campbell Moore, Tom Hollander, Mariella Frostrup.)

Reprieve’s aim is simple enough: to deliver justice and save lives. You shouldn’t really need a charity to cover those two things. But then, neither should you need a charity to prevent cruelty to animals or save the children, but that is the world we live in. Reprieve, founded by unstoppably energetic and courageous human-rights lawyer Clive Stafford Smith, describes itself as “a vibrant legal action charity … that punches well above its weight.” It only has 28 full-time staff, and yet its lawyers were among the first into Guantánamo Bay, a cause that has come to define the charity. They have acted for 83 prisoners there in total, 66 of whom have now been freed and 21 of whom are being assisted by Reprieve’s Life After Guantánamo (LAG) team.

Reprieve hates the death penalty. It does not believe in killing people, full stop. It also hates secret prisons and rendition, whether ordinary or extraordinary. (You’re getting the feeling that Reprieve has its work cut out in a post 9/11 world, and you’re right to.) The charity’s death penalty team have assisted hundreds of prisoners sentenced to death around the world and it knows how to use the media to the advantage of its various causes.

Let’s not be coy, it attracts a lot of celeb supporters, including the aforementioned, and David and Esther – who hosted the evening from behind the lectern and gave impassioned speeches; they also corralled actor chums to read out shocking statistics – and a number of big-name patrons including Vivienne Westwood, Alan Bennett and Jon Snow – and none of this glad-handing hurts.

Clive Stafford Smith’s self-effacing but involving presentation was simply to describe his “average day”, which starts early and ends late, and often criss-crosses continents. Most of the trouble Reprieve seeks out is abroad, for self-evident reasons. We may live in a country whose compassion has been trampled underfoot by market-led politicians, but at least we don’t put prisoners to death. Our American cousins do. Although I learned last night that Pakistan has the most prisoners awaiting death in the world.

You can read more about Reprieve’s work here. It’s ongoing, it’s endless, and their to-do list isn’t going to get shorter any time soon. When the HOPE-defined President Obama reneges on his promise to close Guantánamo Bay, what HOPE is there? Well, it resides with Clive and his team.

Only this week I have been reading about waterboarding in two separate places: in the New Yorker, and a long article (“The Spy Who Said Too Much”) about John Kiriakou, the CIA whistleblower who spoke to the press about the torture used, specifically, on “high-value detainee” at Guantánamo Abu Zubaydah, a suspected Al-Qaeda lieutenant who was waterboarded 83 times, among other nasty “interrogation” techniques, and has never been charged with anything; and in Jason Burke’s The 9/11 Wars, which I’m still ploughing through and which has reached “the Surge” in 2007, by which time George W Bush was in the process of handing over power to his successor, who, to his credit, banned waterboarding. (If only that was the whole picture.)

I spend my days trying to write funny scripts. It’s what I was doing yesterday, and it’s what I’ll be doing today. But I think very seriously about serious matters, and I’m constantly haunted by the wickedness that men do, whether it’s leaving a nail bomb in a bin in Boston, setting fire to a house your own children are asleep in, or signing off on the torture of individuals from behind a desk. Obama is no angel. Blair was a warmonger. If leaders on the left can’t deliver us from evil, where do we turn?

Well, we turn to people like Clive Stafford Smith, whose selfless campaigning and tireless publicising are as much weapons in his peaceful armoury as his legal fleet-footedness. If I can pass on some of his sentiments, then I won’t have wasted another day on writing jokes.

Reprieve links:

Get involved

Buy stuff

Read about their successes

Have a look at this:

Or this:

April 16, 2013

Sterling work

A mere 58,000 viewers tuned in to Sky Atlantic overnight on Wednesday to watch the majestic return of Mad Men, which is down even from the channel’s 98,000 for the start of Season Five last year. It really is one of the least-watched pieces of genius on TV, and it’s the lead review on this week’s Telly Addict, so the Murdoch-intolerant and/or surcharge-averse will at least get to see some majestic clips from its December 1967 incarnation. I also check back in with Game Of Thrones on the same channel (which gets more like 710,000 viewers, by comparison); welcome the first full series of Morse prequel Endeavour to ITV; warm to Victoria Wood’s Nice Cup Of Tea on BBC1; mark the upward turning point of Season 2 of Parks & Rec on BBC4; and applaud Mark Gatiss’s latest period Doctor Who on BBC1.

A mere 58,000 viewers tuned in to Sky Atlantic overnight on Wednesday to watch the majestic return of Mad Men, which is down even from the channel’s 98,000 for the start of Season Five last year. It really is one of the least-watched pieces of genius on TV, and it’s the lead review on this week’s Telly Addict, so the Murdoch-intolerant and/or surcharge-averse will at least get to see some majestic clips from its December 1967 incarnation. I also check back in with Game Of Thrones on the same channel (which gets more like 710,000 viewers, by comparison); welcome the first full series of Morse prequel Endeavour to ITV; warm to Victoria Wood’s Nice Cup Of Tea on BBC1; mark the upward turning point of Season 2 of Parks & Rec on BBC4; and applaud Mark Gatiss’s latest period Doctor Who on BBC1.

Andrew Collins's Blog

- Andrew Collins's profile

- 8 followers