Misha Angrist's Blog, page 4

December 4, 2011

A conversation with writer and troublemaker Carl Elliott, Part II

Introduction and Part I here.

You have criticized your own institution, the University of Minnesota, in print, for being involved in a dubious drug trial in which a patient died. I can imagine that doing a story like that might have saved you on travel, but it probably didn't earn you Employee of the Month. What was that like?

Carl Elliott: It's been pretty ugly.

Can you elaborate? Had you known it would turn out this way, would you still have done it? Has anything good come out of it?

CE: Well, as far as I can tell it has made me a hated figure at the University of Minnesota, at least, in the Academic Health Center. Not a single administrator at the university has said anything supportive or sympathetic, even in private. I've seen people duck in doorways when they see me coming. Last winter, the Board of Regents turned down a request for an external investigation of the suicide. The public affairs office has told reporters I am on a personal crusade against the Department of Psychiatry. Last spring, the General Counsel for the AHC, Mark Rotenberg, met with the Academic Freedom and Tenure Committee to discuss whether academic freedom protects faculty members who make "factually incorrect attacks" on university research.

That said, I've gotten a lot of support from my colleagues in the College of Liberal Arts, and from a handful of my colleagues (not all of them) in the Center for Bioethics. All that has been tremendously reassuring. If not for them, I'd probably be contemplating my next move in a dimly lit room with a bottle of Jack Daniels and a revolver on the table in front of me.

Would I have done it if I had known it would turn out like this? Sure. The trouble with being raised in the South is that you are driven by this twisted sense of shame, and honor compels you to do things that everyone else sees as moronic, insane or self-destructive.

How did you wind up writing for The New Yorker? Did you submit something(s) over the transom? Or did they seek you out?

CE: If you bother them long enough they'll eventually relent and publish something, just to get rid of you.

There are countless MFA grads (myself included) who will be comforted to know that…What about the initial impulse, though? At some point you must have made a conscious decision that instead of sending your work to the Moldavian Journal of Bioethics that you would try for a mainstream magazine. What prompted you to do that?

CE: Unfortunately, I was never able to get an article into the Moldavian Journal of Bioethics. That's a tough nut to crack. I think you need an agent.

Back when I was imprisoned in medical school in South Carolina, looking desperately for an escape route, I used to get The American Scholar in the mail. This was an accident. I had no clue what the magazine was, but it had started arriving after I was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in college. Medical school is a kind of intellectual suffocation, and I was so desperate for air that whenever The American Scholar arrived I would read it cover to cover. It's hard to imagine that now, but it's true. Joseph Epstein used to write an essay for every issue under the name Aristides, usually about something casual but abstract — like, say, name-dropping — and those essays seemed brilliant to me. They were really smart and funny, but also unpretentious. He made writing seem effortless. For years I wanted to write articles like that, for readers like that, but I had no idea how to do it. So I just kept trying and failing, until eventually I stopped failing so often.

I have to ask: what is the deal with your brother, "B. Elliott?" He runs the WCBH website and insults you regularly via blog, twitter and interview. It's quite hilarious, but I imagine that some people don't get the joke–or is it a joke? And what did/does your publisher think?

CE: My brother is a very disturbed man and we can only hope he gets the medication he so desperately needs.

Actually, that website makes me laugh so violently I need medical help myself. My publisher hates it. They think it is juvenile and obscene. They're right, of course, but that's what makes it so funny. It's much better than my book.

You must find yourself mentoring students who, prior to working with you, have been groomed for the sort of bioethics you disdain and who probably don't have much in the way of investigative journalism skills. How do you go about training them?

Over the years I've had a handful of graduate students who seem interested in this kind of writing — by which I mean literary journalism, or narrative nonfiction — and some of those students have been really good, but for the most part, they are pretty set on the standard academic track…which doesn't really make room for this kind of writing.

I did teach a class last year on Investigative Journalism and Bioethics (known informally as "Fear and Loathing in Bioethics.") My co-instructor was Amy Snow Landa, a graduate student here who used to be a health journalist, and we cross-listed the course with the journalism school. You know what bothered the traditional bioethics students the most? Talking to actual human beings. They wanted to write their papers without ever picking up the phone or making an appointment to interview a source. The idea of talking to an actual human being terrified them, especially one who might not welcome their call.

Investigative journalism is a tough job. I admire investigate reporters a lot — the real ones, I mean, not second-raters like me — but they are a special breed. One of the books we read in our Fear and Loathing class was Poison Penmanship, a collection of essays by Jessica Mitford. She quoted an English reporter who said that the only qualities you need for success in journalism are "a plausible manner, ratlike cunning and a little literary ability." To which Mitford added: "plodding determination and an appetite for tracking and destroying the enemy."

That seems about right to me. Investigative reporting is a job where a little bit of malice goes a long way.

December 2, 2011

A conversation with writer and troublemaker Carl Elliott, Part I

In 2009 I attended the annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. The keynote speaker was Carl Elliott. I knew he was a Professor at the Center for Bioethics at the University of Minnesota and I knew he wrote for The New Yorker. I had assigned his piece on the lives of human research participants, Guinea-Pigging, to both my science writing and genomics-in-society classes. But none of that prepared me for his speech, which was eloquent, thoughtful, accusatory, profane, and above all, funny as hell. In 25 years of academic conferences, I can't recall hearing another talk that made me laugh until I cried.

There were hilarious vignettes from Elliott's South Carolina childhood and jabs at "bioethicists for hire" (including many in the audience–at times it was almost as though the National Cattlemen's Beef Association had invited a strident and acerbic member of PETA to deliver its keynote). But in between was a question: why weren't more of us doing what he was doing? Why weren't we investigating egregious, troubling or even benign-but-fascinating practices in medicine? Why weren't we trying to reach bigger audiences to call attention to acute issues in bioethics? Why weren't we, you know, talking to people?

I suspect that the answer is because most of us are neither professionally nor intestinally equipped to do it with the pointed grace and art of Carl Elliott, as evidenced by his recent book, White Coat, Black Hat: Adventures on the Dark Side of Medicine. Part I of our email conversation after the jump.

Bioethicists have written op-eds for a long time. But you went further and began to write long-form narrative nonfiction about corrupt and/or disturbing practices in the pharmaceutical industry (and the "medico-industrial complex"). What led you there? Was it an epiphany or a gradual thing?

Carl Elliott: Well, it wasn't an epiphany. It was probably closer to a slow, simmering anger, at least where the medical-industrial complex is concerned. (That, combined with a sense of shame at being a part of it.) The move to narrative nonfiction was sort of an accident. I just started trying to write more like the writers I admired, and at some point, people started telling me I was doing journalism. Which suits me fine. The occupational hazard of professional philosophy is the suspicion that you are wasting your life.

Who were/are the writers you admired?

CE: That would be a long list, even if you limit it to narrative nonfiction. David Foster Wallace, Jack Hitt and Michael Lewis would all probably be close to the top. Also, Hunter S. Thompson in small doses. The guy had a genius for insults and invective. Right now I am reading a collection of the best nonfiction I have read in a very long time — Pulphead, by John Jeremiah Sullivan.

Has writing in a more literary and accessible style changed your approach to scholarship? Does a publication in The New Yorker "count" as much as one in AJOB in the eyes of your peers? More? Does it matter?

CE: Well, writing for magazines with serious fact-checking departments has definitely changed my approach. I don't think most academics understand how rigorous and obsessive this fact-checking is. It can be painful and humbling. It's way easier to get inaccuracies and mistakes into a peer-reviewed journal than it is into The Atlantic or The New Yorker.

As for what counts: I've never given much thought to it, actually.

Longtime New Yorker writer famously wrote, "Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible…[A journalist] is a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse." Can an investigative journalist defy this fate and if so, how? And is it more difficult for someone whose business card says "ethicist?"

CE: You're calling me an ethicist? Man, that hurts.

There's a lot of truth in what Malcolm says. Personally, I have often found the investigative stories the least troubling of those I have written, because often there is a clear villain. When a powerful doctor has lied, cheated, bullied and exploited vulnerable patients and gotten away with it — bringing those stories to light seems like the right thing to do. The troubling areas are in the grey zones, where honesty seems to require you to reveal unflattering things about people whom you genuinely like.

You call out bioethicists for: explicit/implicit conflicts of interest, out and out corruption, shoddy scholarship, hypocrisy, and what I guess I would call institutional arrogance and narcissism. Are bioethicists doomed to fall prey to the sins you cite?

CE: I'm not sure I'd say bioethicists are doomed. A lot of them seem to be doing just fine, as long as they keep their blinkers on. Most bioethicists are professionally, personally and financially dependent on the medical-industrial complex — which is, let's face it, unjust and corrupt. So bioethicists have to close their eyes to a lot of wrongdoing if they expect to survive. Either that or pretend that they are working behind the scenes to make things better from the inside. That requires a lot of self-deception.

Wittgenstein used to discourage his students from going into philosophy; he said it was it was hard to be both a professional philosopher and a decent human being. It's not that different in bioethics.

Obviously you are not making ad hominem attacks against bioethicists, but neither are you shying away from criticizing their behavior or their stances. What's it like for you at ASBH meetings? Have any of your targets ever said, "Gee, Carl, you're right. I shouldn't have taken that money from Pfizer" or "I've come to realize that commercial IRBs are problematic."? Do they get defensive? Do you think you're seen as a pariah by the bioethics community (if such a thing exists)? Or a useful antiseptic–like a shot of conscience?

Naming names makes me uncomfortable, to be honest. But I'm also ashamed to be associated with a field that has elevated working for powerful, corrupt corporations into a mark of professional status. So speaking out is a way of distancing myself.

Still, I'm often surprised by how many people in bioethics agree with me and tell me so, in private. I just wish that some of them would speak out publicly. But how can you really blame them, when that would mean alienating some of the most powerful people in the field? Maybe they see me as a kind of useful stooge who is dumb enough to say the rude and unpleasant things that nobody else wants to say.

November 26, 2011

You never call

I think those of us (yes, I'm looking in the mirror) who complain loudly when an article we want to read is trapped behind a pay wall have an obligation to call attention to our own work when we–or our generous benefactors–have paid (in this case, $2800) to make it open access. So…here you go. Regular readers will recognize a familiar refrain:

For decades scientists and ethicists have debated the merits and risks of returning and withholding research results from research participants…Recently, those questions have become more acute for genetic data in particular as the cost of DNA sequencing continues to nosedive. Research studies of whole genomes and whole exomes of potentially identifiable people are suddenly everywhere. Thus, even though a given study might be focusing only on the genetic basis of, say, Crohn's disease or epilepsy, a researcher might find that she has every participant's and every control's complete 'cellular hard drive', that is, his or her full set of protein coding sequences and all the variation therein, at her disposal. What's a principled principal investigator to do?

Download the whole thing here.

November 14, 2011

Requiescat in pace

photo source: http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2011/ob...

Dr. Khorana used chemical synthesis to combine the letters into specific defined patterns, like UCUCUCUCU, from which he deduced that UCU encoded for serine and CUC encoded for leucine. His work unambiguously confirmed that the genetic code consisted of 64 distinct three-letter words. He and Dr. Nirenberg discovered that some of the words told a cell where to begin reading the code, and where to stop.

In 1972, Dr. Khorana reported a second breakthrough: the construction of the first artificial gene, using off-the-shelf chemicals. Four years later, he announced that he had gotten an artificial gene to function in a bacterial cell. The ability to synthesize DNA was central to advances in genetic engineering and the development of the biotechnology industry. "He left an amazing trail of technical achievement," said Dr. Thomas P. Sakmar, a professor at Rockefeller University and a former student.

November 13, 2011

Things we said today

In my book, I wrote:

For decades, medical genetics has been criticized as a field akin to bird-watching, whose credo is "diagnose and adios."

That's still true…and even the "diagnose" part is too often elusive.

But change is afoot. Numerous teams of clinicians and genomicists (including two at my own institution) have come together to sequence patients' genomes and/or exomes to identify disease-causing mutations.

Of course, doctors and researchers and genetic counselors are still bickering about when to sequence, whom to sequence, return of results, institutional liability, whether we are confusing research with patient care, and on and on. But for the moment, what everyone can agree on is that parents of kids with serious undiagnosed conditions likely to be genetic absolutely do not give a shit about any of those things.

They want help. They want answers. For two decades we have painted grandiose pictures of personalized medicine. Are we going to keep moving the goalposts? Are we going to tell them that we didn't mean it?

The good news is that the up-and-coming generation of whole-genome sequencing "natives," who are less worried about HIPAA violations than by the prospect having to look heartbroken parents in the eye and shrug and mumble apologies, have begun to organize. Among them are the folks at The Rare Genomics Institute, a nonprofit that raises money for whole-genome sequencing for children with rare or orphan genetic diseases.

One of the reasons I wrote my book was that I thought it was time to move beyond thinking about genetics and genomics as abstractions: a bunch of pea plants 150 years ago, a smear on a gel, a string of letters on a screen, a series of grant applications making vague promises about helping someone with something…someday.

Goddammit, today is the day. Robert, Maya and Gram are not birds in a field guide or case studies in a dysmorphology textbook or entries in a dataset.

They are someone's kids. They could be yours.

Help them.

November 11, 2011

November 10, 2011

All Atwitter II: Seth Mnookin

Thanks again to the immortal Rebecca Skloot for the tweet chat!

I thought I'd do it again by roping in another kick-ass nonfiction writer who's looking at science and its place in the larger world. Seth Mnookin–writer, science maven, blogger, father, pundit, sports fan, dog owner (I could go on)–will join me Friday 11-11-11 aka Nigel Tufnel Day, at 12 noon EST for a chat about his phenomenal SciWriteLabs series, "au courant" nonfiction, poking hornets' nests, and whether we're still sitting shiva for Theo Epstein. Please join us on Twitter on Friday at noon, hashtag #panic

November 9, 2011

"Star by Star"

Many many thanks to Django Haskins and his amazing band, The Old Ceremony. The cacophonous guitar solo stays!

November 7, 2011

Twitter chat with Rebecca Skloot!

Please join us!

Misha

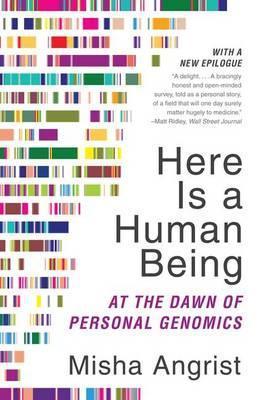

Here is a Human Being redux

This week the paperback edition of my book comes out. To coincide with that, I'm actually going to be present here and on Twitter in a

more substantive way than usual (I know: color you skeptical). As mentioned, I will be having a Twitter chat on creative nonfiction with the incomparable Rebecca Skloot on Tuesday November 8 at 3PM EST. On Friday will be another Twitter event on nonfiction writing about science and its manifestations and other stuff with my sublime PLoG brother, Seth Mnookin (details to come). And another surprise in the interim, assuming I can get my assorted ducks in a row…

Meanwhile, here's the new and improved book trailer:

Music by Sea Cow