Margot Note's Blog, page 50

May 31, 2017

Everyone Should Be Laid Off

It's been about a year since I was laid off. When I think back over the past 12 months, I've realized that the event was one of the best things that has ever happened to me. Let me share with you what I learned.

Prepare yourselfIf you expect layoffs, plan. Take stock of your financial situation, and reduce your spending. If you have upcoming conferences, membership dues, or other expenses, submit them as soon as you can. Make sure your resume and LinkedIn profile is up-to-date. Start networking more; go out for coffee or drinks, and schedule informational interviews. Take care of doctor and dentist appointments. Go through your paper and digital files and make copies of anything you'll need; delete anything personal. Finish any big projects so you can walk away freely. Be proactive about your life, so you don't feel small and scared.

The ax is better than its anticipationWhen I finally got the news, it was a relief. I anticipated it for months, wasting so much emotional energy for no good reason. When you get laid off, you leave behind a place with a bad morale and a heavier workload. You feel free.

Take the high roadWhen you get the news, remain as professional as you can. Avoid saying anything negative in person or online. When you leave a job, all you have is your reputation. Don't destroy all the years of good will you've built for a brief moment of emotion.

It's not personal, but it feels that wayBeing laid off has nothing to do with your worth or performance. It's math. You are either making too much or your employer thinks someone can do your job for less. Don't personalize a choice that is economical or feel shame about it. Figure out a way to explain what happened in a neutral, unemotional manner. Practice it until you're comfortable with it. In time, you will be.

Some people won't understandAnyone who's currently employed knows how common being laid off can be. It has either happened to them or will happen to them. Some friends and family members don’t get it and never will. Reassure them, and keep the conversation moving.

DisengageUnsubscribe and unfollow. I even sold the blouse I wore when I got the news because it bummed me out when I saw it! Realize that former colleagues, no matter how much you liked them, are not the same as your friends. Kindly decline any social engagements with them because they'll mostly talk about the office. Complete any work or training required during the transition, then move on.

All press is good pressAs part of your severance package, you'll most likely not be able to talk about what happened. If the restructuring gets press, be thankful. It’s hard to remain silent when the New York Times is reporting! More than one person I know was offered lucrative consulting gigs and jobs once their layoffs made the news.

Take time offWhen I got the ax, I booked trips to visit family members and went on a friends' vacation. My regret is not taking more time off. To avoid the stereotype of a bath-robed, unemployed person, I initially attended a lot of webinars, classes, and meetings. I would've been better served if I watched more movies, took more walks, and read more books. Chill and recharge for a while; you'll feel a shift in your thinking soon enough, and you'll be ready for the next step in your career.

Seek helpSome severance packages offer group or individual career counseling. Take advantage of it. I attended Five O'Clock Club meetings and had individual career coaching, which I've enjoyed so much that I've continued it after the intial package ended. If you need mental, spiritual, or physical help, get it. Apply for unemployment benefits and any special training or programs available to you. Depend on professionals so you don't have to overburden your friends and family.

See the positiveMy layoff was a great gift in lousy packaging, like a Tiffany ring presented in a colostomy bag. With the news, the slate was wiped clean. You no longer have to worry about making the next logical step in your career. During the decade at my former job, I was looking on-and-off for a job with a better culture, better title, and more money without having to move. (In my field, that's like hunting a unicorn). I wasn't desperate to move on, even with the looming layoffs, because the places I explored were not a good fit. I decided instead to become self-employed as a consultant. I never would've gone out on my own unless the rug was pulled out from under me. In the past six months, I've felt happier, more alive, and more confident than I ever have before.

To those who are recently laid off, it gets better. You will become a better, stronger, more empathetic person. I hope you will soon see the experience as positively as you can. I survived, and you can too!

I'd love to hear about your experience in the comments below, or email me at margot@margotnote.com.

May 23, 2017

How to Prepare for an Archives Visit

Using an archives can be intimidating, especially if it’s your first time. When I teach my students how to visit archives, I highlight nine vital questions to ask themselves to make their time in an archives the most productive and fulfilling it can be.

Ask yourself:

Does the archives hold the records I need to consult? Is this the best place to find what I’m seeking?

You’ll have to do some initial research to determine if this archives has the materials you are looking for. Many finding aids are found online. These documents contain detailed information about specific collections, including historical notes, scope and content, date ranges, and restrictions. If you cannot find the information on the archives’ website, a call or email to the archivist will provide more information.

What materials are the most helpful for you to consult?

Prioritize your requests. Since your research time is limited, examine the most important collections first.

Do I need to make an appointment to visit the archives?

The short answer is probably yes. Having an appointment allows the archivist to prepare the documents for your visit, as well as ensuring that there is adequate reference support and security at the archives. This is especially important if you are traveling to visit an archives. Never assume that you can just show up.

Do I need identification? Do I need to provide evidence of my affiliation, such as a letter from a university?

The archives’ website will provide information on what identification you will need to access the archives. In my experience with American archives, I’ve only needed a driver’s license. International or specialized archives may ask for additional requirements.

Are the records I need to consult held on-site? Will I need to order them in advance of my visit? If the latter, how long will that take?

In many cases, the archival records may be held in facilities outside of the archival institution. Deliveries of archival materials may be made once or twice a week. For materials that are held on-site, the call times may be as needed or at certain times of the day. In both instances, these set times allow maximizing the retrieval efforts with limited resources. Finding aids may help you determine where the materials are kept; information on the archives’ website will inform you on call or delivery times. Plan ahead so that you do not spend your visit waiting for the materials to arrive.

What am I allowed to take into the archives? Are items, such as pens, extra paper, cell phones, or cameras restricted?

Often, you will have to check your coats, bags, and other items in lockers during your visit. Always bring pencils because no archives will let you bring in pens. Knowing what items are restricted before you visit reduces any surprises.

How long will it take to read the relevant documents? Is more than one visit necessary?

This question is more about yourself than the archives. How long can you sustain critical reading? Take short breaks as you work. Can your research be completed in one visit? Or would it make sense to schedule more visits? In some cases, if the archivist knows that you are coming back, he or she can temporarily keep the materials on-site for your return.

Is it possible to photograph, scan, or photocopy the documents? Is there a charge for these services?

Some materials may already be digitized online. Others may be scanned or photocopied for you, but will come with a cost. If you’re allowed to bring in a camera or your phone, you may be able to take pictures of the documents for later reference. Always ask about what your options are.

How do I cite these collections?

Note any unique identifications assigned to the materials such as collection titles or call numbers. Finding aids usually note what the correct citation should be. If you need to reference something in the materials again, or if another researcher tries to trace your sources later, citations will help the archival staff locate the materials. Plus, it’s the right thing to do, research-wise.

I hope these pointers allow you to maximize your time and efficiency and to help your research process go smoothly. Always ask the archival staff for help. Archivists are a friendly group of people (yes, really!), and we love helping people conduct stellar research.

I’d love to hear the tips you use during your archival visits.

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

May 8, 2017

Documenting Your Mother's Life

This Mother’s Day, make your family history project all about your mother by conducting an oral history interview designed for her. Capturing her story is an important part of documenting your family history and one you don’t want to miss before it’s too late.

Take a moment to research your mother’s history before you begin. Researching her past before you start the interview process will save you time in the long run.

Begin with what you know about Mom. If you know her family stories, jot them down. Bring old photos and papers of your mother to jog her memories. Talking about the past is also a great time to bring up the subject of family legacies. Your mother's papers and photographs, as well as her oral history interview, can be easily organized in a family archives.

Create an outline before you start. Chronological is best, starting from her childhood to the present. You will likely find that you and mom won’t follow along exactly as stories may cause her to jump around in time. That’s perfect; ask about dates for the stories so you can keep track.

If you’re planning to publish the interview, you will need your mother’s written permission. While this may seem formal, you don’t want to risk of sharing something about her life that she doesn’t wish to share. If you’re going to publish stories, chances are you’ll need a legal agreement. (I discuss copyright fundamentals here). Skip this step if you are only sharing your mother’s story with family members.

Ensure Mom’s stories aren’t lost by transcribing her interview as soon as possible. Whether you used an audio or video for the interview, review what you created and make notes.

I’ve created a list of 40 questions to ask your mother to celebrate her life. They are crafted to give you more than a yes or no answer and tailored to uncover information about the most important woman in your life.

Enter your name and email address to gain access to the Family History for Mothers Kit, as well as a subscription to my newsletter:

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

May 2, 2017

9 Ways to Verify Primary Source Reliability

To produce sound historical research, we need reliable primary sources. Records created at the same time as an event, or as close as possible to it, usually have a greater chance of being accurate than records created years later, especially by someone without firsthand knowledge of the event. When you are conducting research, you want to corroborate the contents of the document you are working with with information from other sources that have been proven to be legitimate.

While this post concerns written sources, one must remember that these questions can also be posed to other types of primary sources. I always advise my students to consider non-textual sources. For example, photographs have captured information about groups of people that the traditional archival record has not. (The development of visual literacy poses its own challenges, which I may explore in future posts).

Interrogate the sources you use. Consider two aspects of reliability. One is the record itself. The other is that each source contains individual pieces of evidence to be considered as well. You may not be able to answer all the questions below. However, by what you can answer, you may be able to determine whether you can accept the information as truthful.

Was the source created at the same time of the event it describes? If not, who made the record, when, and why?Who furnished the information? Was the informant in a position to give correct facts? Was the informant a participant in the original event? Was the informant using secondhand information? Would the informant have benefited from giving incorrect or incomplete answers?Is the information in the record such as names, dates, places, events, and relationships logical? Does it make sense in the context of time, place, and the people being researched?Does more than one reliable source give the same information?What other evidence supports the information in the source?Does the source contain discrepancies? Were these errors of the creator of the document or the informant?Have you found any reliable evidence that contradicts or conflicts with what you already know?Is the source an original or a copy? If it’s a copy, can you get a version closer to the original? Does the document have characteristics that may affect is readability? Consider smears, tears, missing words, faded ink, hard-to-read handwriting, too dark microfilm, and bad reproduction.In a world of “fake news,” we all have to be mindful about the information we consume. Historical records are no different. Some sources may be considered more reliable than others, but every source is biased in some way. Because of this, historians read skeptically and cross-check sources against other evidence. Being a critical thinker who analyzes primary sources creates quality scholarship and a more accurate historical record.

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

April 26, 2017

How to Preserve Polaroids

I was given a Polaroid camera when I was a teenager that I loved. I liked the look of the photos and the ability to have photos developed instantly. In the course of creating my family archives, I found many of those old photographs and wondered what was the best way to preserve them.

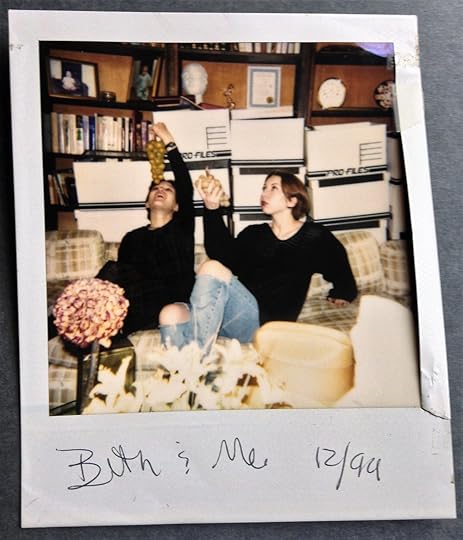

A battered Polaroid from a friend's house, December 1994. Even back then, I was drawn to archives and records boxes!

Polaroids are not archival and were not meant to last forever. They were designed for instant gratification. Compared to other mediums, instant photographs are fragile, especially because the chemicals used in the development process are still in the print and can continue to affect its aging process. As you can see in the Polaroid above, there are rips, tape marks, and stains on this much-loved photo; I know better now.

The process of preserving your instant photos is the same as other photographs. Some Polaroids yellow, fade, or become brittle, but there are steps that you can take to lessen the damage to them over time:

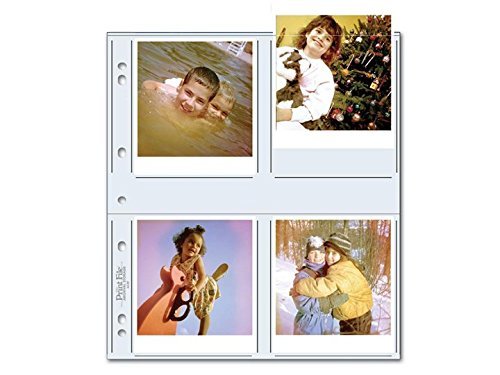

Keep Polaroids out of direct sunlight, moisture (high humidity), and temperature fluctuations.When you’re handling Polaroids, hold them by their corners with clean hands. Oil and dirt from your hands can damage or smudge the photos.Let images dry for several weeks before storing them.Never store them in magnetic albums, or albums made from PVA or PVC, which are types of plastic that can damage photos. If an album smells strongly of chemicals, do not use it.Never cut Polaroids, which can damage them.Dark storage is recommended to prevent fading, although yellowing can occur in lights areas of the print, even when they are stored in the dark.Store them flat, as prints on their side can yellow more than those that are flat.Store them in acid-free photo boxes, enclosures, and albums. Storage items should also pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT), an international standard test for evaluating photo-storage and display products. Archival storage companies sell these items. One possible storage option are pages that store 8 Polaroids per sheet, such as these: Print File 448P 4x4.5 Print Preservers (100 Pack)[image error]

A storage solution if you have many Polaroids that you would like to preserve.

Do you have suggestions on how to preserve your Polaroids?

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

April 20, 2017

What Does "Archival Quality" Mean?

When you are creating your family archives, you will most likely have to rehouse your family treasures in suitable storage containers, such as folders, enclosures, and boxes. These items are often described as “archival” or “archival quality” by their manufacturers, but these terms convey no specifics about their preservation use.

Storage containers should be made of materials that are strong, durable, and chemically stable. Enclosures should be tailored to the size, condition, and use of the items being enclosed. As a home archivist, you will have to evaluate the specific characteristics of each product and chose the appropriate ones. You should consider the acidity, alkalinity, and the presence of lignin.

Acidity and alkalinity are measured by of pH scale from 0–14. The pH of archival storage materials should range between 7 to 8.5, which means it is acid-free.

Although acid-free materials aren’t acidic when they’re manufactured, they can become acidic over time. For this reason, an alkaline buffer is often added during manufacturing to neutralize acids that may be produced over time. Most paper collections will need buffered enclosures. Some types of collections sensitive to alkaline materials, such as blueprints, some photographs, and textiles, should be stored in pH-neutral enclosures.

Storage materials should also be lignin-free. Lignin, a component found in plants and trees, can react with light and heat to produce acids and darken paper if it is not removed during manufacturing.

FoldersAcid-free folders are available in both buffered and unbuffered stock. Heavier weights are available for oversized maps and prints.

BoxesBoxes suitable for long-term storage are available in several types of board that are acid-free, lignin-free, and buffered. They should be sturdy enough to support their contents, have reinforced corners, and have tight covers that prevent dust from entering.

Interleaving MaterialInterleaving sheets of tissue, glassine, paper and polyester film protect items in storage. Acid-free tissue is available with or without an alkaline buffer, as is paper. Polyester film can also be used, as long as it is not used with pastel or charcoal because it creates an electrostatic charge that can damage this media. Use glassine instead.

PlasticClear plastic enclosures are useful for items that are delicate or frequently handled. Clear plastic provides no protection from light, so items in these enclosures should be placed in boxes for long-term storage. Polyester, polypropylene, and polyethylene are three types of preservation plastic. Polyester is used for folders, sleeves, and envelopes. Polypropylene is used for containers. Polyethylene for sleeves and bags is flexible and frosted.

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

[image error]

April 14, 2017

Stop Damaging Your Family Photos and Learn to Protect Them

An essential part of your family heritage is in danger of being lost, and yet few are aware of it.

Most of us have family photo albums in our possession. They are a wonderful way to reconnect with the past as we create our family archives. You would think that storing photos in albums would be the safest way to protect them.

Think again! The kind that you should be aware of because of their damaging nature are magnetic albums. Although they have no magnets, they act that way because they hold photographs in place. Their cardboard pages grip photos on a sticky, adhesive coating, covered by a layer of plastic that is peeled back to position photos. Incredibly, despite the common knowledge that these albums are damaging to images, they are still being sold.

The cardboard gives off chemicals that cause staining. The yellowing doesn’t just affect the page; it can damage the photos too. The plastic seals the photographs in with the cardboard and gives off gasses that attack the images. The adhesive bonds with the photos, curling and tearing them if you try to remove them.

Many of the albums also contain polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a destructive chemical.

These albums tend to hold color images, which are less stable than the black and white film used in previous generations. That’s why many photographs from the 1970s have a color shift that makes them look like an Instagram filter has been applied to them.

If you store the albums in an attic or a basement, the environments expose the pictures to damaging heat, humidity, and temperature fluctuations.

When all of these destructive elements combine in one place, your most prized images won’t last. It’s enough to give this archivist heart palpitations!

There’s hope, if you follow my instructions.

First, remove any family history items out of basements, attics, sheds, or other areas. Ideally, they should be stored in areas of your home that are not in direct sunlight and are the most stable as far as humidity and temperature are concerned. An interior closet is a good choice.

If you have images in magnetic albums, remove the photos if you can without damaging them. Find an acid-free, photo-safe place to store them. The Container Store, for example, sells photographic storage boxes.

Ideally, you should recreate the album in an archival-quality photo album. By doing so, you preserve the way that the album was meant to be viewed, which tells you more about the person who created it.

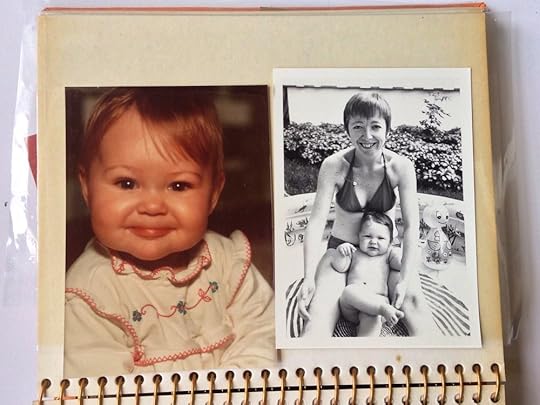

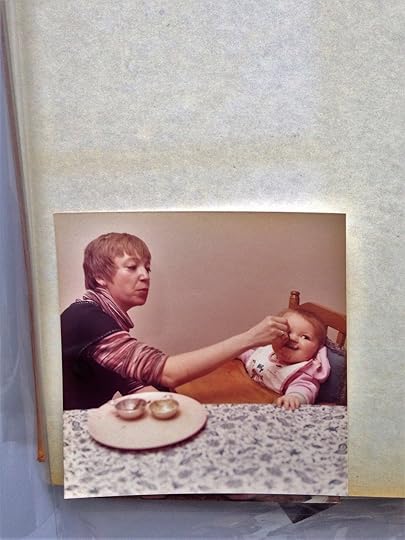

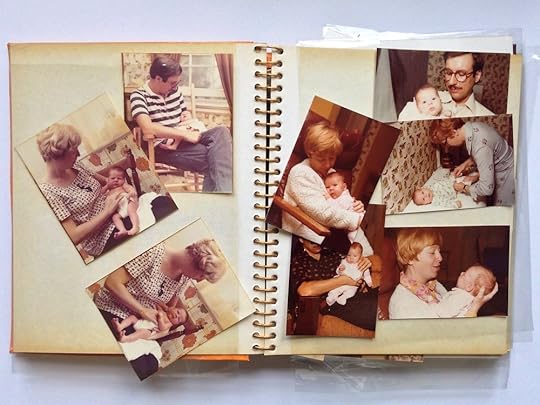

I inherited my grandmother’s photo album; I was her first grandchild. I loved looking at this album at her house when I was a child. I think my love of historic photos can be traced to this artifact.

Let me show you what a magnetic album looks like (and also show off what a cute baby I was!)

[image error]

[image error]

The browning around the edges of this page is typical of highly-acidic paper. Two lines that make me laugh: "The transparent film enhances their appearance and gives them complete protection" and "You can even remove your photos any time after mounting without any damage."

On this page, you can see the yellowing that occurs around the album's edge. I also wanted to highlight how black and white photographs are more stable. The photo on the left seems too orange, while the black and white photo retains its crispness. Look at what a boss I was even back then!

You can see a ghostly outline of where a photo used to be in the upper left part of this image. The photo at the bottom has yellowed around its edges. Damaging chemical transfer occurred within this album.

The saving grace to this album is that no adhesive remains. I don't know if it transferred onto the images, or if it dried out. This makes the photos easy to remove, but they can be damaged by sliding out or sticking out of the album.

If you encounter sticky photos, work with them gently as not to damage or tear them. A piece of dental floss can be used to carefully glide them off the page. If they seem impossible to remove, contact a photo conservator.

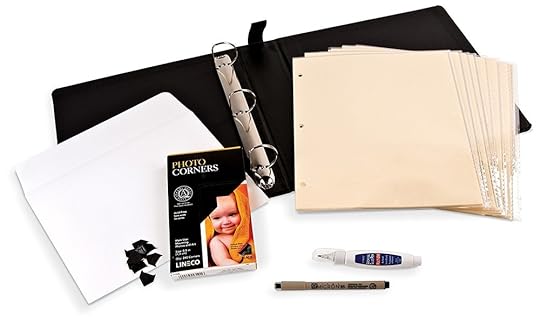

I purchased an archival photo album kit online from Gaylord Archival, as well as a matching slipcase, to keep out the dust. Gaylord is one a handful of companies that sell preservation materials to archives, libraries, and museums. I accidentally ordered the wrong sized slipcase, and a representative called me the next day to correct the order. The company has a good reputation with archivists, and I especially liked this customer service touch.

Gaylord Archival® 1 1/2" D-Ring Photo Album Kit - Cream Mounting Pages[image error]

This post is not sponsored by Gaylord Archival, but the link above is generated through Amazon Associates.

The kit contains 25 mounting pages, two packets of photo corners, an archival envelope, a glue pen, and an archival ink pen (to be used on the pages, not the photos themselves).

[image error]

An example of a page replicated in the new archival-quality album. Once I've decided on the positioning, I would secure the images to the page with mounting corners and write the caption, "10 days old - August 28, 1977" on the page.

I'm in the process of recreating my grandmother's album in my new photo-safe album. Since many images have fallen off the pages or moved, it will take me a bit of time to figure out what image went where. And to be honest, as with many family and personal archives projects, I'm luxuriating in the work. (I save the hustle for when I'm working with my consulting clients!)

Do you have magnetic photo albums? What are you doing to protect your family photos?

To learn the organization and preservation secrets used libraries, archives, and museums to protect priceless materials--the same you can use for your family heritage items--read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today

April 8, 2017

Autographed Copies of Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

I am grateful to everyone who buys a copy of Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs and honored that some people want copies that are signed or have inscriptions. I offer this option for readers who prefer a personal touch over an online transaction.

Autographed copies cost $19, including shipping. Please enter your information below.

Your Name *

Your Name

First Name

Last Name

Email Address *

Payment Options *

PayPal payments should be paid to margot@margotnote.com. Check and money orders should be addressed to Margot Note and sent to PO Box 610112, New York, NY 10461.

PayPal

Check

Money Order

Thank you!

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter. As a gift to you, you'll receive a free, premium download of my Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

April 4, 2017

Jumpstart Your Family Archives Project with a Free Download

Many of us organize a lifelong collection of personal papers and photos either when we have free time, such as in retirement, or when we have to deal with the belongings of a someone who has passed away. Often the project seems daunting because we don’t know where to begin.

Once you jump over that mental hurdle, you will be amazed at what you discover.

The home archivists I work with take inventory of their materials and prioritize the collections that matter the most to them. Then they organize their heirlooms, using the same techniques that professionals at the Library or Congress and the National Archives employ. They work steadily until they create a family archives. You can too.

Are you overwhelmed by organizing your family papers and photos?

Jumpstart your family archives project with the Project Prioritizer. This trusted tool will help you embrace where you are with your collections and start enjoying your family archives more today.

Enter your first name and email address in the fields below to:

Straighten out your messy family history materialsFeel more confident as a family archivist and memory keeper, andDecide exactly what you should work on nextCreating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

March 28, 2017

7 Secrets to Stellar Archival Research

Conducting archival research can be challenging. Unlike libraries, which have assets with consistent information, archives preserve and provide access to unique materials.

Trained as an archivist, I also work as a researcher, so I have a 360-degree perspective on archives. In a graduate-level course on research methods I teach, I offer the following suggestions to my students:

Research the Repository Before VisitingUnderstand the institution's policies and procedures before you arrive to use your time wisely. Each archives is unique, with many different ways of access. Consult the institution's policies on photography, copying, and scanning. Often, there are reasonable scanning and usage fees, so understand those policies as well.

Research Virtually FirstMany repositories have finding aids and collections online. Before your visit, check out these resources. They may be just what you need. Don't depend solely on digital items though. Undigitized and unprocessed collections contain invaluable information. Do what research you can on your own, then reach out to the archivist to see if there are additional collections that you should consult during your visit.

Keep a Research LogIn the course of your research, you will encounter a lot of archival materials. Be kind to yourself, and create a system to log your research. What may seem obvious to you at the moment will be forgotten later, so provide enough information to retrace your steps if needed.

Note information about the repository, contact information, dates you visited, and the collections you retrieved. Write down the order of the boxes and folders you used, as well as the items that you took notes about or photographed.

If the institution allows it, photograph or scan items with your camera or phone. One app I’ve used is CamScanner which creates PDFs (free with Android and iOS). Its paid version performs optical character recognition (OCR) that extracts text from PDFs. Other free or paid apps do the same.

Consider creating a template for yourself so that you capture all relevant information as you work. Notes can be taken on paper or digitally—whatever is best for you.

Standardize Your Filing NamesCreate file naming conventions to organize your digital items and make them easier to retrieve. Free bulk renaming programs allow you to rename many files instantly.

Here's an example of a standardized file name. If I scanned items while researching the Margaret Wright Eadie Papers at the New-York Historical Society, my files may be named: NYHS_Eadie_Box01_Volume01_Item001, Item002, etc.

Use conventions that make sense for you and the collections. Ask yourself, “If another researcher were to see this, would he or she understand it?”

Practice Safe StorageThe best way to keep items preserved is to create backups. Have three backups of your digital items. One collection can be on your desktop that you use as you write, with a backup on Google Drive and another on a personal hard drive.

For physical archival items that you own, you may want to take photographs or scan them so you still have the information they contain if they are damaged, stolen, or lost.

The preservation of analog and digital items is a whole other post (or set of posts). Just remember that nothing lasts forever, especially digital files!

Cite RightFor collections that you will include in your research, locate the proper citation, which is often in the finding aid. Note this as you research to avoid wasting time later when you're facing a deadline for your work.

Say Thank YouIf an archivist has been helpful in your research, send them a handwritten thank you card. Archivists aren’t appreciated enough for the hard work that they do so recognizing their help is important. A shout-out in the acknowledgments section of your article, thesis, or manuscript is also a nice touch.

For additional information, please consult my presentation on using archives and primary sources HERE.

What strategies do you use when conducting archival research?

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter.