Margot Note's Blog, page 45

January 9, 2018

Letter #1: Arriving in Scranton

From January to June 1940, my paternal grandparents corresponded with each other until they were married. I only have the letters that my grandfather sent my grandmother, which have been chronologically organized and preserved in acid-free enclosures, using the methods I discuss in detail in my book, Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs.

For the next six months, I'll be scanning and transcribing the letters on the dates they were posted so we can follow their courtship in real-time. I'm excited to share these lovely family treasures with you!

At the time, my grandmother Ann was working in a textile factory in Paterson, New Jersey, and my grandfather Ray had traveled to Scranton, Pennsylvania with his friend Otto to work at a factory there. Ray and Ann had met in Paterson and were planning to live there after they were married.

Ray, Ann, and Otto at Rockaway Beach on July 16, 1939

What I love most about these letters is that I get to experience a different side of my grandparents than when I knew them--young, lovesick, and dreaming of their future.

The first letter describes how my grandfather arrived in Scranton, met his foreman, and settled in at a boarding house. From what I gather from the letter, Otto might have already worked at the factory and encouraged my grandfather to work there to make money before his marriage.

I should also note that my grandmother's name was Americanized to "Ann Warren" from

"Anna Varasinskas" and my grandfather's name was Americanized to "Ray" from "Renee." They were both eager to get away their poor, rough upbringings.

"Newt" was my grandmother's nickname for my grandfather.

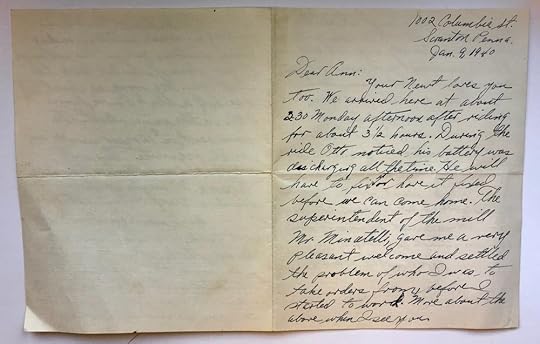

1002 Columbia St.

Scranton Penna.

Jan. 9, 1940

Dear Ann:

Your Newt loves you too. We arrived here at about 230 Monday afternoon after riding for about 3-1/2 hours. During the ride Otto noticed his battery was discharging all the time. He will have to fix it or have it fixed before we can come home. The superintendent of the mill Mr. Minatelli, gave me a very pleasant welcome and settled the problems of who I was to take orders from before I started to work. More about the above when I see you.

I had no trouble in finding a room as Otto's boarding house mistress gave us the addresses of two places of which I took the first one. My room is about one half a block down from Otto's on the same street. The room rent is $15.00 per month in weekly payments. This will amount to a little less than $3.50 per week. No meals are served to boarders therefore I am eating out.

As I mentioned on my post card, I do not definitely know whether or not we will come home this weekend. As it no doubt will be a last minute decision I may not be able to tell you in time to expect me.

Even though it isn't Wednesday night yet I miss you very much already, my beloved. What I wouldn't give now for just one of your sweet kisses. And if I don't see you this weekend heaven knows what I will feel like next week. If it weren't for your picture, I know I would feel much more love-sick.

I must write home yet before I go to bed so may your dream sweet dreams of us and our future together.

Good night beloved.

Ray

***

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

Ready to get started creating your family archives? Here are some of my favorite products:

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

January 8, 2018

Organizing a Zine Collection

A zine (short for magazine or fanzine) is a small-circulation, self-published work. Zines come in a variety of styles: photocopied, printed on cheap paper, or professionally printed. They could and were about any topic imaginable. My favorites were the punk and true crime-related ones. Extreme Noise in Minneapolis had a free zine bin that I happily dug through every time I visited, and I'd leave with the most interesting ones. Zines were particularly popular in the mid- to late-1990s, and were later replaced by blogs and social media.

Zines hold a special place in my heart because I created them in high school and college. By trading them with others around the United States, I felt more connected to a subculture and a little less lonely in the hellscape of suburban Minnesota that was my adolescence.

One of my zines was reviewed in Flipside, a punk zine I read cover-to-cover for years. My future husband, Bill Florio, editor of the somewhat infamous Greedy Bastard, traded zines with me and started writing to me while I was in highschool. We met in person near the end of college, dated long-distance, and then I moved in with him. The rest is history--and almost 20 years together!

(In the interview below, I talk about a Greedy Bastard interview with the Candy Snatchers that angered me so much I stopped writing to Bill for awhile. But he persisted and sent me the next issue. I looked back at the offending issue recently and realized that it's my favorite! Bill, of course, thinks this is hilarious).

Your zine acted like your calling card. When you traded or sold one, you were asking, "I'm into this. Are you into this too?" That simple act started a number of friendships, relationships, and marriages, I imagine.

[image error]

Bill "Greedy Bastard" Florio. Photo by Jewel Frankfeldt Photography (Learn more here: hellojewelphoto.com)

I recently organized Bill's zine collection. Before that, I wrote a post about preserving band flyers, and stated:

Part of the mission of Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs is to bring archives to the people. Perhaps you're not interested in your genealogy or family history. The collections that hold the most meaning to you could be ephemera related to bands you've been in or watched live. The punks who regularly attended ABC No Rio or the Sunday matinee at CBGB's may have become your real family. Whatever your passion, preserve it!

I brought a similar attitude to this project. Not everyone is interested in family history, but you can apply the methods used to preserve family items to your personal history.

The zines were stored in piles in four plastic bins with no order and had been stored under a bed for about twenty years. Here's what they looked like when I started:

A bin of zines, including a Romper Stomper poster!

Another bin of zines

The covers of the bins had kept dust out, but some zines had been torn or damaged because of improper storage. Due to the zines' ephemera-like nature and their DIY aesthetic, I didn't get too precious about their conservation. For instance, I'm not fixing anything that's torn or interleaving pages with acid-free paper (as you would for older booklets or photo albums). Instead, I focused on stopping future damage by organizing, foldering, and rehousing them in better storage containers.

I worked in a small space, laying a blanket on the floor so I could maximize my work area. In an ideal world, I would work on a large, clean work surface; I know for my individual clients, especially, that that type of workspace is impossible. I believe in working within the limitations you have and making the most of them!

I divided everything alphabetically into 5 groups (A-G, H-L, M-Q, R-T, U-Z), then I organized each group alphabetically.

Sorting zines into alphabetical piles

I bought archival-quality banker's boxes and archival folders with a tab that goes across the length of the folder. The latter are my favorite because the length of the tab gives me a lot of room to write. I wrote the zine title on the folder in pencil so I could easily erase the title if needed. Pen isn't used in archives work because it can fade or smear and it can accidentally transfer onto the archival materials. I also don't use labels in archival work because the adhesive can loosen over time. I grouped the zines in folders by name and organized them chronologically by issue number.

I wrote the title on the folder, but the finding aid I created had the title, issue number, month and year, if I could find it. I'm a big fan of minimal labeling on folders. The purpose of a finding aid is to include as much information as you wish that you can update as you learn more information. Having to also change the information on folders is unnecessary.

In the middle of labeling and foldering

Zines don't include easy-to-find information like title, author, date, page numbers, location, and publisher the way books do. Whenever it wasn't obvious, I skipped information. For example, some zines didn't have dates or volume or issue numbers. I guessed at publishing dates if I could find postmarks or other dates.

I purposely didn't catalog the zines fully for a number of reasons. The first reason is because it is unnecessary. In my personal work and my archival work for clients, I aim for minimal viable processing because it keeps labor and resource costs low.

Another reason is a person's right to be forgotten. I don't believe something that someone created before the Internet should necessarily be easily findable on the web, especially when Googling their name.

Here's a real-life example: my best friend growing up wrote zines that are included in a university's zine collection as part of someone else's donated collection. She has since changed her name and has become an Orthodox Jew. A zine that she self-published as a teen explored her sexuality and gender that she sent to a small group of people is now cataloged for the world to access. I imagine that if she asked the university not to list it online, they would comply. Perhaps she doesn't know about it or doesn't care.

I chose not to include personal names of the editors or creators in my finding aid. The title is enough.

Download the Bill Florio Zine Collection Finding Aid.

Maximum Rocknroll, a magazine that Bill had a column in for many years, made up the about a third of the collection. Many issues were in poor shape and were missing covers. I organized them the best I could.

Organizing the zines brought up a surprising amount of emotions. I saw a lot of zines of my friends. I thought about the zines that I used to read and the ones that I created that I threw away years ago. I forgot about some of my favorite zines and issues.

The Black Issue of Ben Is Dead is my absolute favorite issue ever.

The Black Issue of Ben is Dead featuring Boyd Rice, Anton LaVey, Timothy Leary, Robert Anton Wilson, John Wayne Gacy, and Nicole Panter (manager of the Germs) is amazing. I also loved the second and third issues of Answer Me!, which are brilliant but I sold them for a nice price on eBay years ago.

The end result of zine organizing is a easy-to-find collection that takes up half the space that it originally did. More importantly, the materials are in safer storage, so that they can last longer without the risk of damage.

Have you ever gazed upon a more beautiful sight?

After I processed the collection, I interviewed Bill about his zines. The sound quality is not the best because I recorded it on my iPhone and our heater started banging crazily mid-interview. I've included timestamps to aid in listening.

00:05 "How do you define at zine?"

00:38 "When were they most popular?"

01:20 1996: The year zines broke

01:57 "What's the first zine you remember seeing?"

02:59 "Tell me about Smashin Through and Greedy Bastard."

05:10 "Fanzine ordering at Reconstruction Records was a thankless job."

06:09 "I can do better than these zines in a day."

06:30 Finding an authentic voice

07:10 Getting his sense of humor

07:50 How the issue of Greedy Bastard that made me stop talking to him is now my favorite!

08:40 "How were zine distributed?"

10:10 How being distributed by Tower made lifelong friends across the United States

12:30 "How many copies of each issue did you usually make?"

13:30 "It wasn't worth printing less than 2000."

14:00 How selling zines at shows for a quarter was a genius move.

15:00 Selling Bugout Society records at the Nassau Coliseum: "What the hell is this?"

16:00 Selling at a canceled Beastie Boys show to people on whippits

16:40 The best, the worst, the weirdest zines

16:50 Rev. Norb and (Sic)Teen

19:10 "Record reviews are horrible to do."

19:50 Answer Me's Jim Goad as a wrestling heel

20:51 "The GG Allin of publishing"

21:40 Murder Can Be Fun and thesis-level articles

23:09 Riot Grrrl influence (?)

25:30 The Riot Grrrl Showcase at ABC No Rio

28:40 Angry letters

29:14 "Do you want to talk about specific zines?"

29:22 Bullshit Monthly

30:40 Carter

31:35 Scam

32:28 Squat or Rot

33:25 "Don't-take-a-bath zines"

33:54 Combat Stance

34:40 Cotton Mouth

35:22 From the Diane Files

36:00 Hessian Obsession

36:21 Hickey and catfishing

37:15 Hit List as the anti-Maximum Rocknroll

39:10 "Tim [Yohannan] liked that reaction."

39:25 How to Stage Dive

39:40 Being threatened with violence from Ian MacKaye, Jerry Only, Paul Bearer, and Jello Biafra

40:24 Winning fanzine of the year by New York Press

40:45 Nice Hair

40:59 Nine Inch Toenails

41:18 Panty Line Fever

41:33 Surprised by the nakedness

42:10 Generational changes

43:49 Probe: "One of my favorite zines not because of the nudity."

44:30 Roessiger

44:40 Beer Frame

45:01 Zine writers who got book deals

47:00 "If someone is a good writer, they can write about anything."

48:09 Snak Fud

48:20 Weston's zine

48:39 Touch 'n' Go

49:00 Fake hate letter

49:32 David Duke's "zine" and a racist carpenter

51:00 "What are the lasting effects of zines?"

56:00 Punk rock Italians and Punk rock Jews

57:40 Calling Dee Ramone, Henny Youngman, and Mike D.

58:56 "The absence of malice is truth."

I loved working on this project because it combined a subject that I loved with my skill set as an archivist. Do you have a collection that needs similar organizing? Do you need help with determining priorities and a preservation plan? Or would you like for me to archivally process a collection for you? Contact me and we can discuss how I can help!

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items), read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter:

Read more about zines with some of my favorite books:

Ready to get started creating your family archives? Here are some of my favorite products:

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

January 3, 2018

Call for Manuscripts: Women & Collections

I'm so excited to guest-edit an upcoming issue of Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals. I've included our CFP below. If you have any questions, please leave comments or email me at margot@margotnote.com.

CALL FOR MANUSCRIPTS

Women & Collections

A Focus Issue of the journal

Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

Guest Editors: Consuelo Sendino, Natural History Museum, London, Janet Ashton, British Library, and Margot Note, Independent Consultant

Women have not been only inspiration for the cultural world, but been also active as collectors or researchers in collections. They have left their mark in science, natural history and art. Important contributions to cite chronologically are those of Catherine the Great of Russia (1762-1796, art collector), Frances Mary Richardson Currer (1785-1861, book collector), Mary Anning (1799 - 1847, fossil collector) and Gertrude Bell (1868-1926, archaeologist who helped with the establishment of the National Museum of Iraq with one of the best collections of Mesopotamian antiquities).

Although the role of women has been important in collections, it has not been so popular as with males. This issue will display different roles in which women have been active in collections such as active collectors, known by their input in collections or for inspiration.

Articles might be focused on any role played by women regarding collections:

Women as collectorsWomen as collection researchersWomen as inspirational point of view Women as collection subjectFor this issue, we are seeking articles and case studies of 15-25 pages, reviews, technical columns, and observations. See https://rowman.com/Page/Journals for more information about the journal. For more information, contact the journal editor, Juilee Decker, jdgsh@rit.edu.

Published by Rowman & Littlefield, Collections is a multi-disciplinary journal addressing all aspects of handling, preserving, researching, interpreting, and organizing collections. Established in 2004, the journal is an international, peer-reviewed publication that seeks timely exploration of the issues, practices, and policies related to collections. Scholars, archivists, curators, librarians, collections managers, preparators, registrars, educators, emerging professionals, and others are encouraged to submit their work for this focus issue.

Authors should express their interest by submitting a 150-word abstract to the journal editor by February 15, 2018.The deadline for submission of final papers is April 1, 2018. Publication is anticipated for volume 14 or 15 with an issue date of 2018 or 2019.

Like this post? Never miss an update when you sign up for my newsletter:

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

January 2, 2018

Best of Project Management Blog Posts

Here's a collection of my best blog posts on project management. If you're interested in reading more on the topic, please check out my book:

Project Management for Information Professionals

By Margot Note

Access my FREE resource library of the most used and popular project management templates:

January 1, 2018

Research Methods Blog Post Roundup

Here's a roundup of my best blog posts on Research Methods. I love learning and teaching these tips to make people into better scholars and writers.

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

December 28, 2017

Catching Up with Career Advice

The past year for me has been a journey. I started my own consulting business, worked with a number of clients, and expanded my professional network substantially. I also shared some of the lessons I learned from working as a self-employed archivist. Here are some of my most popular posts on my career advice.

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

December 26, 2017

My Most Popular Archival Management Blog Posts

I've compiled some of my best post posts on archival management. I love being a consultant who can help organizations fund, set up, or expand their archives programs. Interested in learning more about what I do? Check out my services.

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

December 25, 2017

Peruse Creating Family Archives Blog Posts

I've written a lot about family archives over the past year, but sometimes my readers miss a post or are new to my community. I've listed my posts related to how anyone can learn methods to save their personal and family history.

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items), read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

If you like archives, memory, and legacy as much as I do, you might consider signing up for my email list. Every few weeks I send out a newsletter with new articles and exclusive content for readers. It’s basically my way of keeping in touch with you and letting you know what’s going on. Your information is protected and I never spam.

December 18, 2017

Catch The Christmas Spirit

What I like most about Christmas is that it's a time that everyone decides to relax and recharge. From about the beginning of Christmas week to after the new year, everyone steps away from their normal day-to-day work and home lives and reconnects with friends and family. Time is slower. You can snuggle up to read a book, take a nap in the middle of the afternoon, and watch movies late into the night.

The best part of the season is that you reconnect with family, friends, and business acquaintances. Family is most important, of course, especially when you look back on past Christmases.

Some of my favorite Christmas memories are:

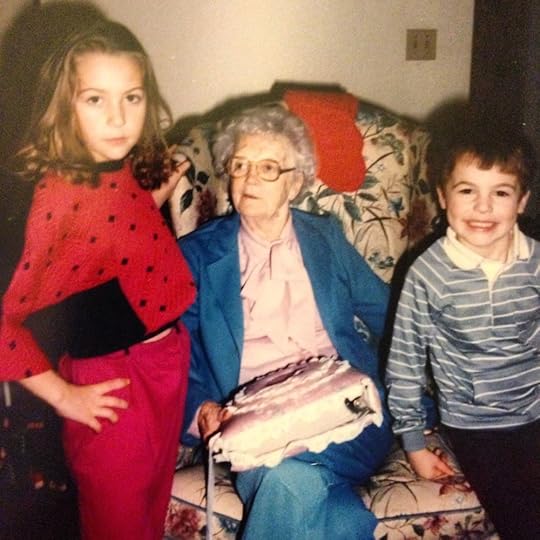

My grandparents and great-aunt used to stay over Christmas Eve, so that they could wake up and watch my brother and I open Christmas presents. I remember one year getting SO MANY Barbie accessories. I hate Christmas decorations (and still do). My family called me the Grinch because I preferred to read in my room when they set up the tree. However, I always liked these wooden clothespin doll ornaments my mom made when I was little to hang on a mini-tree we had. In high school, every Christmas list I wrote requested The Anarchist's Cookbook, a how-to manual on the home preparation of weapons, electronics, drugs, and explosives. (!!!) My parents had the good sense not to buy it for me, and I find this request hilarious in retrospect. I remember celebrating Christmas in Yonkers with my husband's family when I first moved to New York. Everyone is Italian; I thought they were fighting until I realized that everyone is just loud! A friend of the family made rum balls that would knock you off your chair.My favorite Christmas tradition is visiting the Bronx Christmas House, which defies description. #bronxpride I love watching my niece and nephews open their presents so I can relive the Christmas excitement through their eyes. I love seeing how excited children get this time of year!I also want to take the opportunity to share some hilarious Christmas photos from years ago. In third grade, I was obsessed with acting like a model. All our holiday photos from the year feature extreme looks and poses. Aunt Reese is looking at me like I'm nuts, and Marty is just too adorable for words.

Now it's your turn!

I've created a guide of 40 Family Christmas Questions so you can share your memories with your loved ones. This time of year provokes so many emotions of yesteryear, while also letting you think about the new year.

As with all my oral history kits, use my questions as a guide to start a conversation. Record the remembrances on your phone, take notes, or simply listen. You'll get to know members of your family and their history better after sharing your stories.

Interested in my other oral history kits? You can also download:

300+ Personal History Questions Workbook

Family History for Mothers Kit

Family History for Fathers Kit

50+ Halloween Family Memory Questions

Enter your name and email address to gain access to 40 Family Christmas Questions, as well as a subscription to my newsletter:

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Ready to get started creating your family archives? Here are some of my favorite products:

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook

December 11, 2017

Celebrate the Festival of Lights

Hanukkah commemorates the victory of the Maccabees, a group of Jewish freedom fighters, over the Syrian Greek army. Although they were outnumbered, the Maccabees were able to retake the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. They gathered together in the temple to read the Torah, but there was only enough lamp oil to last a day. The lantern burned for eight nights, and they saw this as a sign of God. Hanukkah is celebrated to keep the memory of this miracle alive and also to honor the heroic feat of the Maccabees.

Families gather together to celebrate the Festival of Lights because it brings warmth, hope, and coziness to our lives. Hanukkah is traditionally celebrated by lighting the menorah, playing dreidel, and eating foods like latkes, or potato pancakes. Chocolate gelt, a candy that gets its name from the Yiddish word for money, is another popular treat.

Hanukkah candles are lit as dusk is falls. Their flame serves as a beacon in the night. No matter how dark it seems, a single candle can light the way.

As each successive candle of the menorah is lit, the flickering flames assure us never be afraid to stand up for what's right. The Maccabees faced daunting odds, but won. All you need is a little faith.

Download my 40 Family Hanukkah Questions to start documenting your favorite family stories about the holiday. What are your most loved traditions? How has your family celebrated these eight days of togetherness over the years?

Many families exchange gifts each night throughout the holiday. I'm always curious to know each family's gift giving practices. Do they get the big gift on the first night? Is there a slow and steady build up to that last night? Is the gift giving like a bell curve, with the most important gift given on the fourth or fifth day? Is it completely random? I'd love to know your gift giving practices!

Interested in my other oral history kits? You can also download:

300+ Personal History Questions Workbook

Family History for Mothers Kit

Family History for Fathers Kit

50+ Halloween Family Memory Questions

Enter your name and email address to gain access to 40 Family Hanukkah Questions, as well as a subscription to my newsletter:

To learn the preservation secrets used by libraries, archives, and museums to protect their priceless materials (that you can also use for your family heritage items) read my book:

Creating Family Archives: How to Preserve Your Papers and Photographs

By Margot Note

Ready to get started creating your family archives? Here are some of my favorite products:

Follow me on Pinterest | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook