John Coulthart's Blog, page 42

April 29, 2023

Weekend links 671

No. 54 (1915) by Anna Cassel.

• “I called it the treasure hunt: two years of tapes appearing from closets, letters dropping out of attics, persuading a film company to find the rushes of a TV show buried in a warehouse, paying a film director to digitise unused footage and a radio company to surface an old broadcast.” Nick Soulsby on pursuing the ghosts of Coil for his book about the group, Everything Keeps Dissolving.

• “It is likely that af Klint scholarship is on the brink of some radical changes regarding attribution and authorship.” Susan L. Aberth on the researches revealing collaborations between Hilma af Klint and other mystically-inclined women artists. It makes a change reading something about this group that isn’t completely dismissive about the beliefs that informed their work.

• New music: No Highs by Tim Hecker (“a beacon of unease against the deluge of false positive corporate ambient currently in vogue…”), and Seascape–polyptych by Jan Jelinek.

I think an unfortunate effect of Foucault’s work, as it was absorbed by academia, was that it made historians reluctant to call people or sexual acts in the past ‘homosexual’ or ‘gay’ since these terms ‘did not exist at the time’ or were recent creations. This gave some homophobes a spurious defence when suggestions were made as to the inclinations of their heroes, but it also—or so I thought—tended to downplay the reality of non-opportunistic homosexual desire as a constant in history, reducing it to recorded acts performed and then deeming these inadequate evidence anyhow, because they were assumed to have taken place in a fuzzy sexual universe.

If, as it seems to me, and as it seemed to Symonds and Carpenter, terms like ‘homosexual’ were invented in the effort to describe a type of person that has always existed, then they are in essence just a shorthand. Each term has its history, associations and effects, but—and perhaps this makes me an unsophisticated thinker—I think it’s the sexual feelings that fundamentally matter, and that these have existed across time. For that reason, I don’t find the Victorian sexual psyche, as far as it can be defined, alien or outlandish, or hard to speculate on. It is the product of sexual feeling filtered through observable social beliefs and conditions.

Tom Crewe talking to Amia Srinivasan about The New Life, Crewe’s debut novel which explores Victorian sex and sexuality

• “I’ve been tumbling down the rabbit-hole of toy theatre all my life, and I’m tumbling still.” Clive Hicks-Jenkins on the dark art of the toy theatre.

• At Public Domain Review: Jean Baptiste Vérany’s Chromolithographs of Cephalopods (1851).

• “Glass is perhaps the most frequently overlooked material in history,” says Katy Kelleher.

• At Cartoon Brew: Chris Robinson remembers the surreal animations of Run Wrake.

• At Unquiet Things: Of Dreams and Dark Pasts: Surrealist Painter Sofía Bassi.

• RIP Harry Belafonte.

• House Of Glass (1969) by The Glass Family | Heart Of Glass (1978) by Blondie | Slow Glass (1997) by Paul Schütze

April 26, 2023

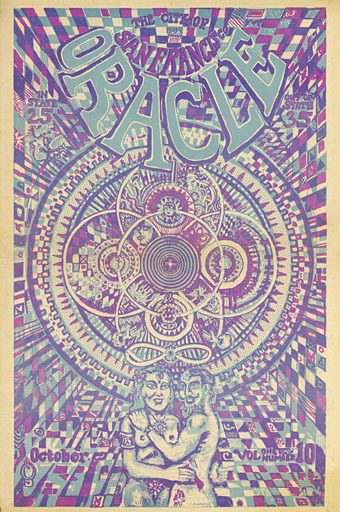

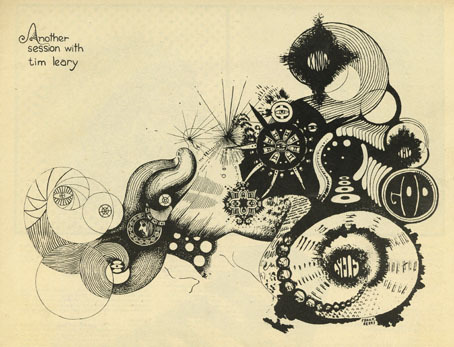

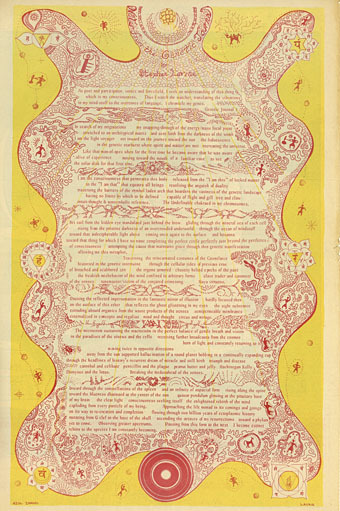

Consulting the Oracle

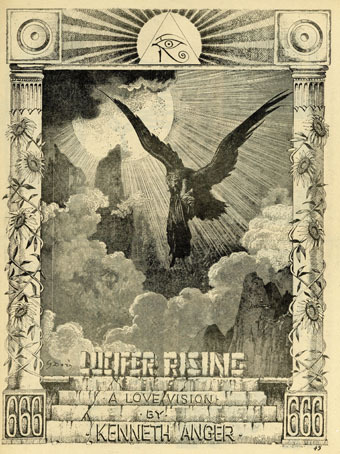

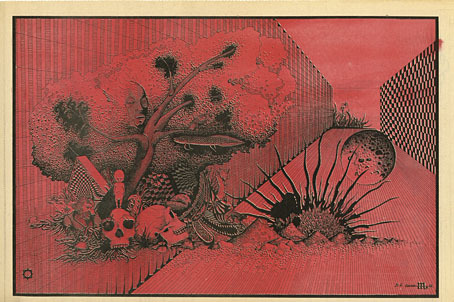

Good to find such a pristine reproduction of this Rick Griffin poster. Kenneth Anger commissioned the design in 1967 when he was putting together a package of promotional items to stimulate the interest of potential investors in his new film. Bill Landis in the unofficial Anger biography says the ploy was a successful one, investors were forthcoming although it would be several years before Anger had enough footage for the ill-fated first version of Lucifer Rising to appear in public. While we’re on the subject, I’ll note again that the Gustave Doré engraving used here is from the Purgatorio section of The Divine Comedy, not Paradise Lost as some people continue to claim. Milton’s Lucifer had wings of his own, as well as god-like powers, he didn’t need to be ferried around by a giant bird.

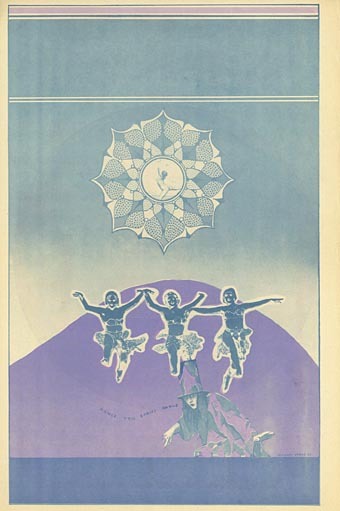

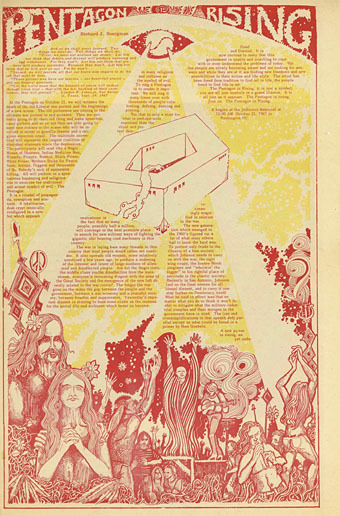

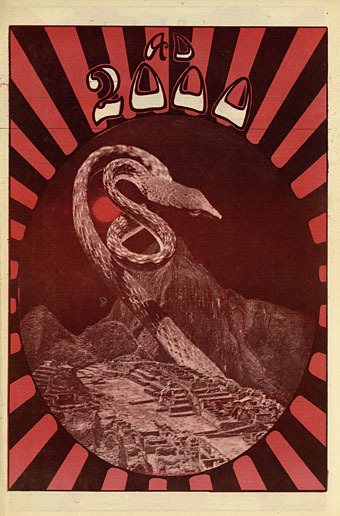

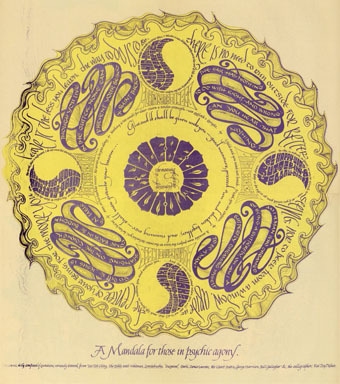

This copy of Griffin’s poster is from issue 7 of the Oracle, or the San Francisco Oracle as it was later titled and known outside the city, an underground newspaper, and one of the best where graphics are concerned.

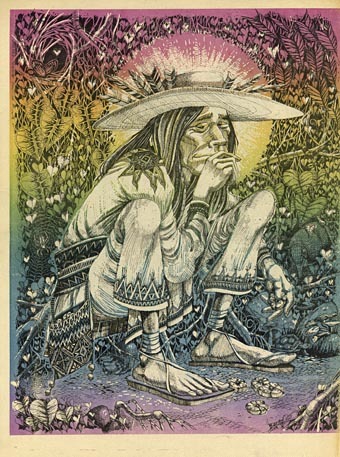

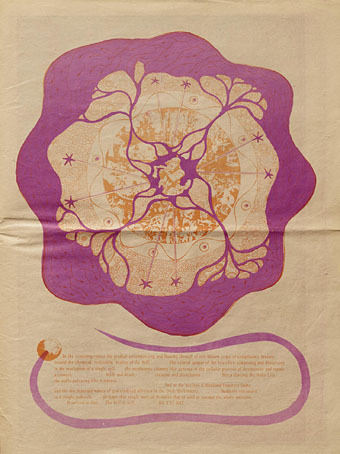

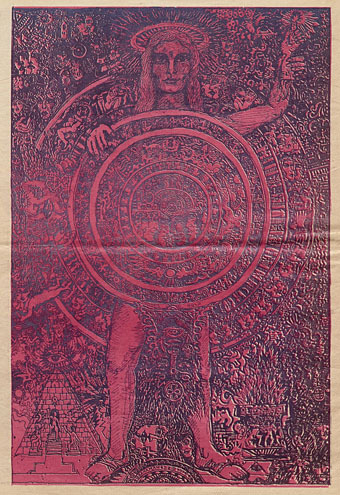

Underground papers and magazines of the late 1960s often followed the form of other amateur or semi-professional publications, with attractive cover art wrapped around more prosaic interiors. The Oracle ran for 12 issues, from 1966 to 1968, and in its later issues gave as much attention to the appearance of its inner pages as its covers, assisted by artists like Griffin and Bruce Conner. Being based in the city that gave the world so many exceptional concert posters was an obvious advantage.

I was hoping the Internet Archive might have a complete run of the Oracle but only four of the highly-decorated issues are currently available. There’s no Wilfried Sätty artwork in evidence either, although I’m not sure he ever worked for the undergrounds despite there being many titles to choose from in the Bay area. Of note in one of the later issues is a full-page announcement for the forthcoming march on the Pentagon, an anti-war protest that took place in October 1967. Kenneth Anger attended the event although the exact nature of his involvement, like so many other Anger stories, varies according to the reporter.

• San Francisco Oracle – Vol 1, No 7

• San Francisco Oracle – Vol 1, No 9

• San Francisco Oracle – Vol 1, No 10

• San Francisco Oracle – Vol 1, No 12

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Gandalf’s Garden magazine

• Oz magazine online

• Lucifer Rising posters

April 24, 2023

Saga de Xam revived

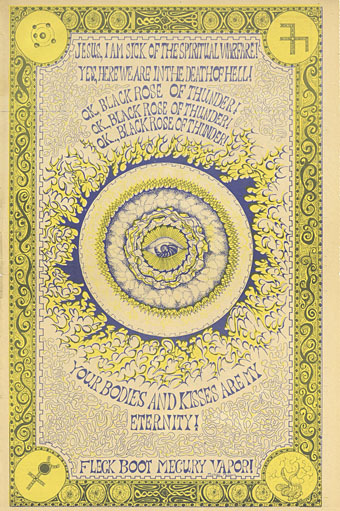

Saga est magnifique. Saga a la peau bleue. Saga est une extraterrestre. Envoyée par la reine de la planète Xam, la voici qui parcourt la Terre à plusieurs époques, traitées dans des styles différents. Son but: découvrir la quintessence artistique, politique et poétique de notre belle Terre. Marquée par l’Art nouveau, le psychédélisme américain, l’érotisme des années 1960 et la contreculture occidentale, Saga est une oeuvre hors norme et inclassable, dessinée sur des formats géants et publiée une première fois par Éric Losfeld en 1967. Hélas, le livre est très vite épuisé et devient un objet pour les collectionneurs. Cette édition reprend l’intégralité des planches de Saga, renumérisées et dotées d’une nouvelle mise en couleurs fidèle à l’originale. Saga peut enfin repartir dans une nouvelle… saga.

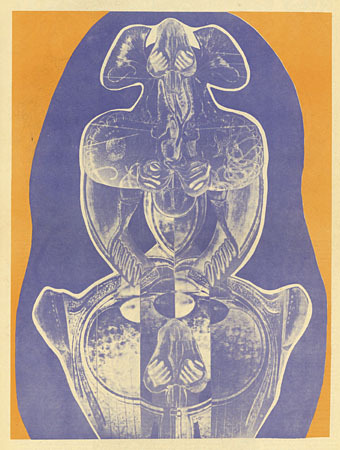

Here’s a book I never expected to see in a new edition. Saga de Xam is a 100-page bande dessinée depicting the time- and space-voyaging adventures of a blue-skinned alien woman, Saga, newly arrived on Earth from the planet Xam. The Xamians are a race of humanoid lesbians (their reproduction is parthenogenetic) whose planet is at war with the masculine Troggs; Saga has been sent to Earth to find a way to combat the Trogg invasion, an expedition that instructs her in the propensity of humans towards conflict and violence. The story was drawn by Nicolas Devil, with contributions from guest artists, and based on an outline by Jean Rollin which had been intended originally for a science-fiction film. There’s no need to go into detail about this cult item, I wrote about it at length several years ago after a couple of its pages stimulated my curiosity when they turned up in an exhibition catalogue. The book was published in 1967 by Éric Losfeld, an edition of 5000 which the publisher said he would never reprint, partly because of the expense, but also because he liked to think of the book becoming a rare object in the future. Rare it still is, although the embargo was broken in 1980, a year after Losfeld’s death, by the publication of a second edition. This was only a partial reprint, however, with a poor cover design and all the interior pages reproduced without their colour overlays.

The new edition from Revival is slightly larger than the original (27.5 x 36 cm to the original 24 x 31 cm), and bound between heavy boards. A lengthy preface by Christian Staebler describes the book’s history, offering a few biographical details about Nicolas Deville (as he was known pre-1967), together with further information about the story’s creation. The wildness of the final pages is explained as an attempt by all involved to capture some of the delirium of an LSD trip, while also bringing the story of Saga’s investigation of the human race and its violent nature into the present day. Jean Rollin was apparently unhappy with this dénouement but I find the ending to be a satisfying one for a story where each chapter explores a different period of time (and of space, when Saga returns to her home planet).

The icing on the cake is the appearance near the end of a few early drawings by Philippe Druillet, together with several beautiful pages by Devil, one of which found wider circulation when reprinted as a poster. The text in the new edition is still in French, of course, and even on slightly larger pages the legibility problem from the original remains. Devil was drawing on boards that were twice the size of their printed equivalents, without caring too much whether the story would be readable when scaled to a printable size. Losfeld’s solution was to provide a magnifying glass with each copy of the book. This isn’t too much of a problem; the story is easy enough to follow once you know the general outline, and for this story it’s the art that counts more than the words.

In addition to history and biography, the preface also describes the efforts required to reprint the book. The original drawings were sold off long ago, while the pages of the original printing were deemed unsuitable for further reproduction. The artist’s son, Stan Deville, decided with Staebler to scan the black-and-white pages from the 1980 reprint then colour them to match the original. This has been very carefully done, with no discernible difference between the old and new printings. Slight differences are evident away from the comic, however, with the title pages that separate each part of the story having been reworked for reasons which aren’t explained. There’s also the anomaly of the stylised pyramid graphic that precedes the chapter set in Ancient Egypt. In the new edition this has been printed upsidedown…or possibly the right way up if the original printing was erroneous, which seems unlikely. If this is an error then it’s a forgivable one when the edition restores such a scarce volume. The book ends with a handful of extra pages showing examples of Devil’s art post-Saga, including the cover of Orejona, ou Saga Generation (1974), another collaborative work, and yet another rare book deserving a reprint. (The French apparently refer to scarce volumes such as these as “UFOs”.) Staebler’s biographical notes confirm that Devil/Deville gave up art when he moved to Canada where he became a professor of philosophy, another reason why his name and his artwork have receded over time. Online examples of his non-Saga drawings are scarce but this page has more than most.

A page featuring unmistakable Druillet figures. He also wrote the accompanying text which refers to Cthulhu and the Necronomicon.

Saga was one of a series of comic-book heroines published by Éric Losfeld in the 1960s (Barbarella, Jodelle, Pravda, et al) whose adult adventures began the evolution in bande dessinée that led eventually to Métal Hurlant and all that followed from that extraordinary magazine. Despite his influence, Losfeld often seems overlooked when the history of French comics is being discussed in Anglophone quarters. Druillet’s first Lone Sloane story, The Mystery of the Abyss, was published by Losfeld in 1966, four years before Lone Sloane was presented anew to a larger readership in Pilote magazine. Losfeld’s intentions in this area were partly exploitational—most of the stories happen to involve young women in sexual scenarios of some kind—but this was a common trend in 20th-century publishing, the publishers of erotica (or outright pornography) being more prepared than reputable publishing houses to push artistic boundaries. Saga de Xam was too lavish a project for the underground press, and too erotic and experimental for other publishers when comics in France were still being produced with a young readership in mind.

Saga de Xam remains fascinating today because it was sui generis, a much more ambitious one-off than Losfeld’s other comic books, and one that made a considerable impression before becoming the bibliographic myth that its publisher intended. Over half a century later the myth is secure enough to sustain a new edition. As Christian Staebler says at the end of his introductory text: “It is finally time to contradict Éric Losfeld and to present Saga de Xam to the eyes of the younger generations, to allow them to discover or rediscover the quintessence of the 1960s.”

I bought my copy of the book from Gallix but you’ll find it at many other French booksellers. And since my French is so poor I scanned the preface then ran it through some translation software. I’ll be keeping this on file so if anyone would like an English copy send me an email.

(My thanks once again to Goldfires for giving me the opportunity to see the pages of the original book, and to Julian for the news about the reprint!)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The groovy look

• The Dracula Annual

• Saga de Xam revisited

• Saga de Xam by Nicolas Devil

April 22, 2023

Weekend links 670

An octopus catching a lobster (1894) by Gustav Mützel.

• RIP Barry Humphries. He emailed me a couple of years ago in his capacity as a collector of fin-de-siècle art, hoping I might answer a question about a very obscure artist. If you require justifications for the blogging habit then add this to the list. Humphries’ first book, Bizarre (1965), is a more cerebral counterpart to Charles Addams’ Dear Dead Days, and a compendium of oddities that I’d buy if I ever saw it in a secondhand shop. RIP also to incendiary singer Mark Stewart.

• “Schulz gets compared to Kafka because of his dreamy, disconcerting stories, but in Balint’s book, a version of Schulz emerges that is closer to one of Kafka’s characters—a man on the run who can’t get past the city walls; an artist exiled by a shape-shifting, unknowable tormentor—than to Franz himself.” Leo Lasdun reviewing a new biography of Bruno Schulz by Benjamin Balint.

• “Instead of asking whether an octopus shows aspects of human intelligence, perhaps the better question is whether humans can show aspects of octopus intelligence.” David Borkenhagen on octopuses and what they might teach us about the perception of time.

• “Uproar was my element, I wanted to get people moving, the more they roared, the bolder I became.” The pioneering theatrical performances of Valeska Gert are explored at Strange Flowers.

• Digital copies of albums by the mighty Earth may currently be purchased at the group’s Bandcamp page for $1 each. I’ve got everything already but you may wish to sample something.

• Charles Drazin on the director who dared to tell uncomfortable truths: Lindsay Anderson at 100.

• Steven Heller on Commercial Art, a magazine from the 1920s that chronicled UK design.

• At Unquiet Things: The luminous drama of Frants Diderik Bøe’s bejewelled floral still lifes.

• New music: This Vibrating Earth by Field Lines Cartographer, and Draw/Orb by Extra.

• Mix of the week: XLR8R podcast 796 by Gold Panda.

• The Strange World of…Andrzej Korzynski.

• The Jewel In The Lotus (1974) by Bennie Maupin | Jewel (1985) by Propaganda | Black Jewelled Serpent Of Sound (1985) by The Dukes Of Stratosphear

April 19, 2023

Eco Del Universo

Eco Del Universo, the ninth album by Mexican band Los Mundos, was released last month on Acid Test Recordings. I designed and illustrated the outer and inner sleeves for an album whose music is described on the group’s Bandcamp page as psychedelic rock. I’ve not seen a physical copy yet but the vinyl disc is available in two pressings that complement the colours of the cover.

The brief for this one was for something based on the concrete fantasia known as Las Pozas, an overgrown park with accompanying hotel that Edward James spent many years and a great deal of money building in the Mexican jungle. James was a British aristocrat who fell for Surrealism in a big way in the 1930s, using his inherited wealth to support artists such as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Leonora Carrington, while creating Surrealist-styled homes for himself, first at Monkton House in West Sussex then at Xilitla in Mexico. James and his jungle resort have been recurrent subjects here so I didn’t need much encouragement to create something based on his constructions. In the past I’ve described Las Pozas as unfinished but this suggests a scheme with a final goal in mind. I don’t think this was ever James’s intention. His creations are more like very large concrete sculptures rather than architecture, even though some of them have a recognisable architectural form. Finished or not, the structures are a unique hybrid of the purposeless architectural folly—a popular indulgence for British landowners of the 18th and 19th centuries—and caprices like the Palais Idéal of Ferdinand Cheval.

My cover art is a fantasy on the fantasy which makes James’s improvisations look a little more planned than they are by mirroring their disposition. I also crowded together several of the constructions which at Las Pozas are in separate areas of the complex. Looking at the artwork again I’m reminded of some of Roger Dean’s views which wasn’t my intention originally. I think it’s the combination of unusual architecture, layered foliage and the treatment of light and shade. If the structures weren’t outlined and the sky was a Dean-like gradient there’d be even more of a similarity. The beautiful stellar photo is from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) whose images of the cosmos are free to use so long as you give them credit. This one was by Stéphane Guisard.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Secret Life of Edward James

• Palais Idéal panoramas

• Las Pozas panoramas

• Return to Las Pozas

• Las Pozas and Edward James

April 17, 2023

Bugged by Jaffee

This one is for my own benefit as much as anyone else’s. Last week, after reading about the late Al Jaffee, I went looking for the panel you see above, a minor item in a much longer Jaffee feature for an issue of Mad magazine from the 1960s. The flatbugs have been one of my favourite Jaffee jokes for many years, but never having kept a note of which issue they appeared in I’ve always had a problem finding them when I’ve wanted to tell someone about them or see them again. On this occasion searches for various combinations of “mad”, “magazine”, “jaffee”, “bugs”, “flatbugs”, “flat bugs” yielded nothing other than a brief mention on a Reddit thread, along with too many articles about insect infestation. Google Books is sometimes useful for search leads but not this time. Twitter still has its uses, however; someone there had mentioned the flatbugs a couple of years ago, as well as the issue they appeared in, Mad no. 107 for December 1966, so here they are at last.

The thing that made the flatbugs so memorable (if not locatable) was that this is a rare Mad joke that’s allowed to extend throughout the rest of the issue. Jaffee’s bug panels occupied two corners of a three-page collection of puzzles and visual gags which is why they’ve always been difficult to track down, you won’t see any mention of them in an index or table of contents. Despite this, issue 107 really ought to be called the flatbug issue. Once you’ve read about the breeding habits of the creatures you start seeing more of them on the pages that follow, even those by artists other than Jaffee; the last of the bugs appears on Jaffee’s fold-in page. This has some precedent in the tiny Sergio Aragones cartoons that appeared in the page margins but I’ve not seen any other one-off gags used like this. Jaffee is lauded for his fold-ins but this shows him playing with the form of the magazine in a different way, suggesting that these were real creatures, albeit motionless and almost two-dimensional.

I only got to see issue 107 a few years ago when scanned copies of the magazine began to turn up online. Prior to this I knew the flatbugs from one of the reprint books which were all you got to see of older copies of Mad magazine outside the US. I might never have seen these either if it wasn’t for a friend at school who collected humour paperbacks. He had a huge stock of the things, not only the Mad books but many of their spin-offs by Al Jaffee, Don Martin and co. The book with the flatbugs, Rip Off Mad, dates from 1973 but most of the material inside is from the previous decade. I’ve not seen a copy of this since the 1970s but I know that the bugs spread throughout the book just as they did in the magazine, even though the contents were different to issue 107.

In 2003 the flatbugs came to mind when I was writing my entry for the Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric and Discredited Diseases. My disease, “Printer’s Evil”, is a fungal growth that infects paper, and thereby passes to anyone who touches an affected page. The entry itself was, of course, contaminated in this way. Ideally one of the pages for this section would have had a frayed edge but there wasn’t the budget for such indulgence. If you do have the budget then the possibilities expand for humorous invention. The first Monty Python book, Monty Python’s Big Red Book, features a die-cut page (below), while Eric Idle’s Rutland Dirty Weekend Book has a parody of Rolling Stone magazine (Rutland Stone) printed on smaller-sized newsprint pages bound into the centre of the book. The Python books were developing a convention established by Mad (and continued in National Lampoon) of parodying print media in exacting detail, matching fonts, layouts, graphics and so on. (See this article.)

From the Python books. Left: Monty Python’s Big Red Book (1971); right: The Brand New Monty Python Bok (1973).

The pinnacle in this sphere is The Brand New Monty Python Bok, with its smudged fingerprints printed on a white dust-jacket (which prompted complaints from booksellers), beneath which you find a cover for a very different book, Tits ’n Bums: A Weekly Look at Church Architecture, a cover that must cause problems for resale if the dust-jacket is missing. Inside the book there’s a tipped-in library card showing the names and signatures of previous owners, while two differently-sized supplemental sections are bound into the pages. In the early 1960s Terry Gilliam had worked for Harvey Kurtzmann’s Help! magazine so there’s a direct line from Python back to Mad, especially when other artists on the Help! staff included Mad regulars Al Jaffee, Jack Davis and Will Elder. The Mad-like quality of The Brand New Monty Python Bok is reinforced by a pair of Gilliam comic strips. Jaffee’s flatbugs would be (immovably) at home there.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Blivets

• The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

• Gilliam’s shaver and Bovril by electrocution

• Portuguese Diseases

• Pasticheur’s Addiction

April 15, 2023

Weekend links 669

Love (1973), a poster by Nicole Claveloux.

• “Warner Brothers had been keen on a Rolling Stones movie. Jagger was keen on being a movie star. But Donald Cammell’s script was no Beatles’ jolly japes musical comedy…” Des Barry examines the ninth minute of Cammell & Roeg’s Performance.

• “…part of what made his 1970s work so original was the degree to which his band cross-pollinated guitar with synthesizer.” Aquarium Drunkard explores the esoteric jazz-rock of Steve Hillage.

• Magma, the cosmic jazz-rock group from France, have been around for 50 years without making a music video. Hakëhn Deïs is their first.

There was half-Tarkovsky embedded in async, “Solari” and “Stakra” and “Walker”, a hand outstretched to those great poems of living and light that we call films. “I had a strange dream last night,” Andrey Tarkovsky wrote in one of the diary entries collected in Instant Light, “I was looking up at the sky and it was very, very light and soft; and high, high above me it seemed to be slowly boiling, like light that had materialised like the fibres of a sunlit fabric, like silken living stitches in a piece of Japanese embroidery.”

David Toop remembers Ryuichi Sakamoto

• “Floor796 is an ever-expanding animation scene showing the life of the 796th floor of the huge space station…”

• The Electrifying Dreamworld of The Green Hand: Dan Clowes on the comic-art of Nicole Claveloux.

• At Bandcamp: Andy Thomas on the post-punk pop subversion of David Cunningham.

• At Unquiet Things: An enigmatic baroness and her collection of skulls.

• New music: River Of Dreams by Romance & Dean Hurley.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Ray Gun.

• Mix of the week: DreamScenes – April 2023.

• RIP Al Jaffee.

• Skulls Of Broken Hill (1996) by Bill Laswell | The Bees Made Honey In The Lion’s Skull (2008) by Earth | Black Skulls (2018) by Jóhann Jóhannsson

April 12, 2023

Kris Guidio, 1953–2023

A self-portrait, 2011.

Farewell to the artist I used to refer to as my partner in art-crime. We weren’t really criminals but in the 1990s we’d both seen our published works for Savoy Books condemned as obscene in British courts of law, a farcical set of circumstances looking back, although it all seemed serious enough while it was happening. Kris and I began working for Savoy in the late 1980s, during which time our creative confederacy might be characterised as familiarity at a distance. He lived in Liverpool, and generally remained there, while the rest of us were in Manchester, so I saw his drawings much more than I saw him in person. I don’t think I ever met him more than 10 times in 30 years, yet his art was as familiar as my own, especially when I was being called upon to add backgrounds to some of his figures. I even ended up making a font based on the lettering he used in his comic strips in order to standardise the captions in the later books.

Kris and I shared a symbiotic relationship with writer David Britton, who pushed the pair of us to take our art into places we might otherwise have avoided, while we opened up artistic possibilities for Dave’s characters and the settings they occupied. We were an ideal team in this respect, each of us having strengths in different areas that suited the titles on which we worked. I brought a greater sense of realism to the Lord Horror comics, while Kris developed a hitherto unexplored flair for satire and caricature in the Meng & Ecker series. Kris was a natural cartoonist, as well as a natural humorist to a degree you wouldn’t have predicted looking at his early strips and illustrations featuring The Cramps.

The Meng & Ecker comics provoked the ire of the authorities, thanks in part to Dave’s frequent digs at the Greater Manchester Police, but there was a lot more to Kris’s art than outrage, a quality which is always easy to generate if you push the right buttons. His Cramps strips are gems of that minor form, the rock’n’roll comic, while his later illustrations for the La Squab character had a lightness of touch that suited Dave’s conception of a world where fairy tales and childhood fantasies collide with adult themes and sensibilities. Kris’s art was analogue to the last (I don’t think he ever owned a computer), drawn with whatever pens he had to hand; watercolour-hued, and fuelled by endless cigarettes. Kris in person was generous, witty, and erudite in the autodidactic manner common to all at Savoy. Remote or not, we’ll miss him here.

Further reading:

• Sinister Legends (1988)

• The Adventures of Meng & Ecker (1997)

• Fuck Off and Die (2005)

• La Squab: The Black Rose of Auschwitz (2012)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• David Britton, 1945–2020

• Posterized

• The Cramps at the Haçienda

• Reverbstorm: an introduction and preview

April 10, 2023

Eco calls on Cthulhu

In which Umberto Eco nods fleetingly to the Cthulhu Mythos near the end of his second novel, Foucault’s Pendulum. I’d show you more of the relevant passage (below) but it’s rather spoilerish if you haven’t read the book. This turned up during a re-reading, my first since the novel appeared in paperback in 1990. A reference like this doesn’t stand out as much as it might elsewhere, not when the text that precedes it is stuffed to the gills with esoterica. Several hundred pages of occult history had made me forget that Eco had hauled Lovecraft into his compendious fabulation along with everything else.

Ishmael Reed was responsible for returning me to Eco’s novel as a result of an earlier re-read of Mumbo Jumbo, Reed’s fictional account of voodoo, jazz, politics and many other things in the America of the 1920s. Eco was already in mind prior to this since I’d been working my way through his many essays and lectures. (As I still am. He wrote a lot of the things.) Mumbo Jumbo‘s exploration of occult knowledge and occult conspiracy summoned vague memories of Foucault’s Pendulum, which made me realise that I didn’t remember very much at all about Eco’s novel even though both books share an interest in the tangled history of the Knights Templar. To the top of the pile it went.

It’s been interesting reading Eco’s novel again. For a start, it was funnier than I remembered, although this may be a result of my being much more familiar with the publishing business than I was in 1990. The story concerns a trio of men who work for a small publishing house in Milan, a division of which is devoted to the works of self-financing authors or “SFAs”. A vanity press in other words. A potential SFA turns up with a crank book rather similar to The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, then abruptly disappears without collecting his manuscript. Curiosity, idleness and invention inspire the trio to improve upon the manuscript’s occult conspiracy in a manner that knits together just about every aspect of Western mysticism there is, and even some of the Eastern ones: Rosicrucianism, alchemy, the Kabbalah, Atlantis, the Illuminati, ley lines, the Hollow Earth, Stonehenge, etc, etc; it’s all in there. This is the thing they eventually call “the Plan”, a kind of Unified Field Theory of esoteric knowledge, and a contrivance whose fabrication is assisted by further SFA manuscripts arriving as candidates for a new line of “Hermetic” books. Problems arise for the publishers when their elaborate intellectual game ends up being taken for a serious revelation by a group of fanatical mystics. Eco’s novel demonstrates the pleasures of creative apophenia—the trio are continually challenging each other to fit a new piece of historical data into their scheme—while also acting as a warning that any halfway plausible Plan has the potential to be taken seriously by credulous cranks. As Lia, the novel’s voice of reason, says:

People are starved for plans. If you offer them one, they fall on it like a pack of wolves. You invent, and they’ll believe. It’s wrong to add to the inventings that already exist.

Eco explored this phenomenon more seriously in a later novel, The Prague Cemetery, which invents an author for the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a Plan whose conspiratorial claims continue to fuel anti-Semitism the world over. The internet has only accelerated Plan-construction, and I imagine Eco would have been simultaneously fascinated and appalled by the feeble imaginings of that ex-football player with the lizard obsession, and the shambling, frothing Q-mob with their Very Important jpegs. (What is it that the latter are always saying? “Trust the Plan”… And having mentioned Mr Icke, I just put his name into Google only to find that the latest extract from his Twitter feed has him talking about the Holy Grail. Welcome to the Crank Zone.)

Upper row: Dell paperbacks illustrated by Carlos Victor, 1975; lower row: Sphere paperbacks illustrated by Tony Roberts, 1976–77. The novel was originally published in three parts but was always intended to be a single book, as it is in later printings.

Someone once said that beneath or behind all political and cultural warfare lies a struggle between secret societies. Another author suggested that the Nursery Rhyme and the book of Science Fiction might be more revolutionary than any number of tracts, pamphlets, manifestoes of the political realm.

Ishmael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo

Reed’s words are paraphrased in an epigraph that appears in the opening pages of Illuminatus! by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, one of the precursors of Foucault’s Pendulum, and a novel with a more generic approach to all-encompassing conspiracy theory. I doubt that the Eco readers who shun “sci-fi” would be aware of this but Eco himself certainly seemed to be; there in his library of references you’ll find mention of a minor occult group that I took to be a veiled nod to Robert Anton Wilson. (Rather than elaborate I’ll leave it as something for Discordian readers to discover.) Where Eco’s invention is (mostly) pieced together from old Hermetic manuscripts with Latin titles like Utriusque Cosmi Historia, Shea and Wilson mine the contents of the 20th-century crank bookshelf along with generous helpings from the popular culture of their time, especially the psychedelic culture of the 1960s. Consequently, there’s a lot more Lovecraftian reference in Illuminatus!—the Pentagon, for example, turns out to have been given its shape in order to contain the bound energies of Yog-Sothoth—while Lovecraft himself turns up as one of the novel’s many characters. The correspondences between the two novels are deepened if you know that Shea and Wilson first had the idea for Illuminatus! while working as associate editors at Playboy magazine in the 1960s. The many conspiracy-obsessed letters they received were fuel for their imaginations in the same way as the manuscripts submitted to Eco’s publishing trio. Illuminatus! was the result of Shea and Wilson asking themselves what it would be like if all these conspiracies were true.

Table of contents from Secret Societies (1961) by Arkon Daraul/Idries Shah.

I remember someone on Twitter a few years ago wondering whether a portion of the current conspiracy mania could be laid at Robert Anton Wilson’s door. I said I couldn’t see it. Illuminatus! is a very self-referential novel which also works to increase the reader’s scepticism rather than undermine it, a process that Wilson continued in his later books. As with Foucault’s Pendulum, most of what Shea and Wilson were writing about was already in the public sphere; someone even complained to me once that there wasn’t anything original about Illuminatus! at all. (I disagreed. fnord) There was plenty of this stuff around before Shea and Wilson arrived, and a lot more that came after them. Secret Societies by Idries Shah (writing as Arkon Daraul) is a book referred to several times in Illuminatus!; in it you’ll find chapters on all the cults and cult figures dealt with in the novels of Eco, Shea and Wilson, together with many lesser-known sects. Pauwels and Bergier’s The Morning of the Magicians is another prior text that Eco, Shea and Wilson all refer to, as well as being a book responsible for entire sub-genres in the Crank Zone. Pauwels and Bergier referred to their methodology as “Fantastic Realism”, a term that allowed some room for manoeuvre when it seemed they were straying too close to outright fiction.

One of Umberto Eco’s favourite writers, Jorge Luis Borges, said he liked to regard metaphysics as a branch of fantastic literature; you can do the same with the crank bookshelf if you’re so inclined, and even make a lot of money if you get the ingredients right. The Indiana Jones franchise is the Crank Zone strained through the conventions of the matinee serial: films 1 and 3 riff on ideas from Trevor Ravenscroft’s Spear of Destiny, and Pauwel and Bergier’s Nazi occultism, while film 4 is all Area 51 and ancient astronauts. Extensions of the franchise in other media have taken in Atlantis and the Hollow Earth. The Eco, Shea and Wilson novels go much further, they share a complexity you seldom find elsewhere in this area. Illuminatus! may be a genre novel but it’s also freighted with serious appendices, footnotes and bibliographic references. The most popular conspiracies are distinguished not by their complexity but by the poverty of their schemata: plots that sound like Gothic melodrama, bad science fiction or Dennis Wheatley after he’s spent the afternoon raiding his wine cellar. The cerebrally-challenged want an elevator pitch, not an intertextual entertainment that rattles on for 800 pages, contradicting itself while it unfolds. Robert Anton Wilson was fond of quoting the famous line from Science and Sanity by Alfred Korzybski: “A map is not the territory”; Umberto Eco, being a good semiotician, uses the same quote as an epigraph for chapter 83 of Foucault’s Pendulum. It’s a simple enough statement but a lesson that many people still have difficulty learning.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Crank book covers

• Morning of the Magicians book covers

April 8, 2023

Weekend links 668

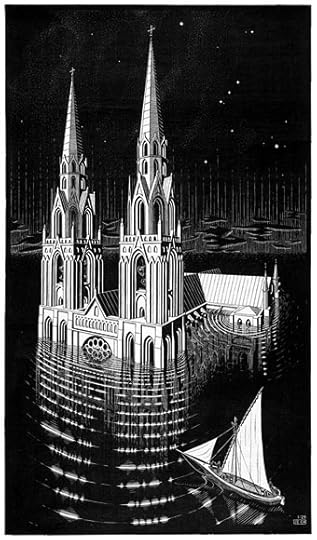

The Drowned Cathedral (1929) by MC Escher.

• “All Saints’ was the last of the seven parish churches to fall headlong into the waves. The drowned church was doomed to lie in a gulley not far out to sea, a habitat for sponges and crabs, and yet it lives on, unvanquishable; for—as the story of Britain’s lost cities, ghost towns, and vanished villages tells us—what has disappeared beneath the sea can rebuild itself in the mind.” Matthew Green explores the history of Dunwich, Suffolk.

• “Why do certain artists endure and become (dread word) ‘iconic’, while some are forgotten or sidelined or only grudgingly acknowledged?” Ian Penman talking to Jeremy Allen about his new book, Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: A new edition of England’s Hidden Reverse, David Keenan’s study of the lives and music of Coil, Nurse With Wound and Current 93.

• “What is electronic music?” Daphne Oram, Desmond Briscoe and David Cain of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop are here to explain.

• New music: Timespan by Majeure, and Microdosing by African Head Charge.

• “Future of Borges estate in limbo as widow doesn’t leave will.”

• Arooj Aftab’s favourite albums.

• Paperback Covers on Tumblr.

• The Engulfed Cathedral (1974) by Tomita | Engulfed Cathedral (1981) by John Carpenter | La Cathédrale Engloutie (2003) by Sora

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers