John Coulthart's Blog, page 41

May 22, 2023

Glaser goes POP

The purchase of big art and design books requires careful consideration round here, what with shelf space being stressed in multiple ways. (One of the shelves bearing the heavier volumes sags alarmingly.) But this one was recommended to me by a couple of people, and I’d also had a book token hanging around unused for over a year so here we are.

Skin types for Seventeen magazine, 1967.

Milton Glaser: POP is a copiously-illustrated 288-page study of the work produced by Milton Glaser and his colleagues at Push Pin Studio, with an emphasis, as the title and cover art suggests, on the company’s prime decade of the 1960s. The book was compiled and edited by the redoubtable Steven Heller, together with Mirko Ilic and Beth Kleber, and presents an overview of Glaser’s remarkable career as designer and illustrator. Glaser was an exceptionally versatile artist, something which has often made appraisal of his career a difficult business. You could easily choose ten of his book or album covers from the many examples assembled by Heller and co., and all would look like the work of different people.

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell; Pocket Books, 1969. I’d much rather have this set than my Faber collection which packages the four books into an unwieldy brick.

Matters are further complicated by the often collaborative nature of the work at Push Pin, and the fact that designers and illustrators aren’t always given credit for their commissions. In the past I’ve gone looking for Glaser’s work then given up when I seemed to be encountering designs that weren’t by him at all. In addition to demonstrating Glaser’s range, Heller, Ilic and Kleber have done everyone a service by showing unused illustrations and crediting work that was previously debatable. Some years ago I wrote a post about the uncredited cover art for the first budget sampler album, The Rock Machine Turns You On (1968), an entry which didn’t manage to resolve the issue of whether or not the cover art was Glaser’s work. It turns out it was by him after all, collage being one of the techniques he employed from time to time.

TIME magazine gets groovy. A fold-out cover from 1969.

On a more personal level, Glaser’s versatility and multi-disciplinary approach is encouraging if you find yourself being led in a similar direction. Designer-illustrators are no longer as rare as they used to be, but illustrators, like many fine artists, still tend to develop a favourable style which they then stay with year after year. Illustrators who change their style according to their mood, or the nature of the brief, or a desire to experiment, remain in the minority. Glaser’s illustration ranges more widely than any other artist I’ve seen, from realistic pen-work and watercolour sketches, through bold, stylised designs, to complete abstraction. He could also be playful and frivolous in a manner you can’t imagine from some of his more serious contemporaries, while also being adept enough at illustrating children’s stories that he might easily have spent his career doing this alone.

Avon Books, 1970.

But the main attraction of Milton Glaser: POP for this reader is the focus on all those bold graphics, especially the commissions that reworked the emerging psychedelic styles for the commercial sphere. The cover illustration is emblematic of many other examples. This drawing first appeared in a New York magazine supplement in 1967 to accompany an article about LSD, before being reused on the dustjacket of Tom Wolfe’s book about Ken Kesey and friends, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Glaser and his colleagues at Push Pin were prime exponents of something I’ve taken to calling “the groovy look“, a term I reserve for commercially oriented quasi-psychedelic art. This isn’t meant to be a serious label, it’s a private term that I used to attach to anything resembling the art styles seen in the Yellow Submarine feature film. Serious or not, the label persists when I continue to feel the need for a suitable descriptor for this type of art. “Psychedelic” is the most common label (and one which obviously suits Yellow Submarine) but it seems inappropriate when discussing magazine adverts for household products or illustrations in children’s books. Steven Heller prefers the term “Pop”, but this strikes me as too loose, risking confusion with the many varieties of Pop Art which seldom resemble the vivid, stylised creations of Glaser et al. Pop would also seem misapplied as a description for commercial art when Pop Art was all about the appropriation (ironic or otherwise) of commercial iconography. If you start to label a swathe of commercial art as Pop along with the gallery art that was borrowing from it then the term becomes so diffuse it loses its meaning. The “groovy style” had a long reach, and evolved beyond the decade it was born in. Plenty of examples may be found in the early 1970s by which time Pop Art (in the gallery sense) had lost its momentum.

Above: Glaser ad art, 1966. Below: Dave Dragon’s cover art for XTC, 1989.

I’ll no doubt return to this question, especially when I’ve just done something in the groovy style myself. (You’ll have to wait a few months before you see the results.) In the meantime there’s a lot to enjoy in this book. I haven’t yet mentioned Glaser’s unused promotional art for the Saul Bass feature film, Phase IV, or the many typeface designs that Glaser created with his associates, and the way one of them—Baby Fat—is used on the cover of the first UK paperback of The Soft Machine. I think this was the first William Burroughs book I ever bought, and it’s been sitting on my shelves all this time without my realising it was a Glaser production. That’s how it often is with graphic designers; they shape our world almost as much as architects do yet their specific influence isn’t always recognised.

Corgi Books, 1970.

And by coincidence, the latest post at The Daily Heller is about a Glaser exhibition tied to the publication of the book. If you’re in New York it’ll be running for the next two weeks.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The groovy look

• Milton Glaser album covers

May 20, 2023

Weekend links 674

The Far Side of the Moon, as photographed by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

• “It goes against centuries of traditional belief to accept that the moon is barren, that it is indifferent, that it is innocent of any role in monthly spikes in the crime rate or in the cycles of menstrual unreason. When telescopic observation had found nothing on the near side (Roger Boscovich had established by 1753 that it lacks even an atmosphere), the far side still remained a site for the projection of fantasies of a different, neighbouring world.” Justin EH Smith working his way towards a history of the dark side of the moon.

• “It shocks me that movies still lean in so hard to all these outmoded gay narrative tropes: coming out, coming of age; very identity-oriented representations of gay characters. It’s much easier to represent a gay boy who’s repressed in high school and comes out and makes friends. It’s very mainstream, and kind of played out.” Bruce LaBruce on cinematic trends in relation to his new film, a gay-porn take on Pasolini’s Teorema.

• At Cartoon Brew: Pavel Sannikau explains how he developed his own techniques of digital animation in order to create the ever-expanding Floor796.

• There’s always more Poe: Mysterium, Incubus et Terror, Poe-inspired music by a variety of artists, plus illustrations by John D. Chadwick.

• At Smithsonian Magazine: The results of a themed contest in the Close-Up Photographer of the Year Challenge.

• Mixes of the week: In Praise of the Saddest Chord at Ambientblog, and The Funky Eno Pts 2 & 3 by DJ Food.

• Steven Heller talks to Hungarian artist István Orosz about his Escher-like drawings.

• At Unquiet Things: Caitlin McCormack’s ghostly chains of knotted memory.

• At Spoon & Tamago: Intricate and organic sculptures by ceramicist Eriko Inazaki.

• New music: Illumina by Call Super with Julian Holter.

• Dark Side Of The Mushroom (1967) by The Chocolate Watchband | Dark Side Of The Star (1984) by Haruomi Hosono | On The Dark Side Of The Sun (live) (2003) by Helios Creed

May 17, 2023

California Images: Hi-fi for the Eyes

More psychedelia-adjacent visuals. California Images (1985) is another of those video collections that pairs computer graphics and animation with music that’s mostly electronic, 54 minutes of cathode exotica aimed at armchair psychonauts with video-recorders. This one was produced by Pilot Video, and is subtitled “Hi-fi for the Eyes”, the term “hi-fi” doing a lot of work there for an NTSC video cassette. The quality, artistic as well as technical, may not be first-rate but I’m still pleased to see videos like this being resurrected. As I’ve said before, nobody would want to reissue these compilations today, especially the present example whose contents don’t always work well together.

All the pieces are presented as separate shorts rather than running into each other, with most of them being very simple computer animation or the products of video feedback plus video synthesis. On the visual side, many of them seem to have had the slit-scan lightshow from 2001: A Space Odyssey as their ideal, while their soundtracks are mostly New-Age synth burblings which range from the okay to the mediocre. Between these clips are a couple of other items which don’t suit the hippy-trippy mood at all, especially the one titled Speed, several minutes of nocturnal driving footage accompanied by harsh industrial rhythms more suited to the TV Wipeout collection released by Cabaret Voltaire in 1984. Oddest of all is the inclusion of Oskar Fischinger’s Allegretto (1936), a classic of abstract animation whose meticulous artistry puts to shame many of the other offerings. The collection ends with Ed Emshwiller’s Sunstone (1979), one of the earliest attempts to push computer animation beyond pattern-making. Emshwiller’s luminous faces look towards the digital future. I remain partial to analogue video effects, however, and Electric Light Voyage, aka Ascent 1, is still my favourite of all the TV lightshows I’ve seen to date. The search for more like this one will continue.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dazzle

• The Gate to the Mind’s Eye

May 15, 2023

X-ray visions

Cover art by George Wilson.

Cosmic weirdness isn’t something you expect to find in the tie-in comics published by Gold Key in the 1960s, but this adaptation of Roger Corman’s film contains a few such traces, as does the film itself. Having watched X: The Man with the X-ray Eyes again recently I was curious to know how artist Frank Thorne would manage with the scenes where Dr Xavier’s vision is showing him more of the world than he wants to see. Despite the general sketchiness of the drawing, in some of the panels these visions are more fully realised than they are in the film, it being easier to draw an unusual effect than capture it on celluloid. Roger Corman had a great idea, a talented co-writer in Ray Russell, and an authentically tormented performance from Ray Milland, but the film is hampered by the limitations of AIP’s budgets. When Xavier complains about the oppressive sight of people above him on the floors of his tenement building only the comic shows us what he sees.

So too with the later scenes, by which time all of Corman’s point-of-view shots are the same combination of a diffracted lens (Spectarama!) and Les Baxter’s wailing theremin. Xavier’s description of a great watching eye “at the centre of the Universe” isn’t conjured so well by Corman’s visuals. The comic gives us an all-too-human eyeball floating in space, but before this there’s a panel of ragged shapes flapping through the interstellar void, as well as something never seen in the film when Xavier looks down into the Earth’s core.

The comic was written by Paul Newman (not that one), and was evidently adapted from a script rather than a print of the film. None of the characters or scenes resemble their cinematic equivalents, while Xavier’s eyes in the comic hardly change appearance. But the additions to the finale make me wonder whether there was a little more in the script than ended up in the film.

Corman made The Man with the X-ray Eyes in 1963, immediately after The Haunted Palace—the first film to adapt HP Lovecraft—and a few years before The Trip—the first feature film devoted solely to the psychedelic experience. Xavier’s journey into nightmare is a curious hybrid of Lovecraft and psychedelia: the titles are set against a swirling violet spiral, while the doctor’s Spectarama visions are precursors of the delirium experienced by Peter Fonda’s Paul in The Trip. (Corman’s initial idea for The Man with the X-ray Eyes had a jazz musician taking too many drugs.) At one stage in his LSD trip Paul looks in a mirror and announces that he can see inside his own brain, but in the earlier film we get to see inside Xavier’s brain for ourselves when he takes his eye drops for the first time, after which the camera passes through the back of the doctor’s head until we’re looking out of his eyes. This is so close to a moment in Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void that I’ve been wondering whether Corman’s film is another of Noé’s cult titles like those you see named at the beginning of Climax.

As for the Lovecraftian quality, The Man with the X-ray Eyes misses an opportunity to do more with the scope of its central concept. Stephen King famously reported a rumour that the film had a suppressed line of dialogue from the very end, when Xavier tears out his eyes then screams “I can still see!” Corman denied that this was the case but admitted it was a good idea. King mentions this in Danse Macabre, in a description of the film which also interprets the story as being far more Lovecraftian—he uses that word—than it actually is. His suggestion (or mis-remembering) is that all the Spectarama effects are Xavier’s growing perception of the Eye at the centre of the Universe, even though Xavier only mentions this presence in the last few minutes.

The implications of this remain unexplored but Xavier’s final vision of cosmic horror is still truer to Lovecraft’s Mythos philosophy—a warning that the human race peers into the void at its peril—than almost anything else in cinema, and the revelation is made all the more disturbing by the appearance of Xavier’s eyes which by this point are solid black orbs. As King suggests, there’s another film altogether lurking under the surface of this one, a horror film with a cosmic reach. Hollywood still struggles to do anything substantial with Lovecraft’s fiction, but you know the way things are today we’ll be lucky to get anything weirder than more CGI monsters and lumbering kaiju. I wouldn’t want to suggest that Gaspar Noé remake The Man with the X-ray Eyes but if he ever wanted to create a psychedelic horror story then the cosmic route is the way to go.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Undead visions

• Trip texts revisited

• More trip texts

• Enter the Void

May 13, 2023

Weekend links 673

Butterfly (1988) by Ay-O.

• “[Mike] Jay says there are notional lessons to be learned about what happens next from the characters who populate Psychonauts but says they would have been of greatest benefit to ‘the legislators, the bureaucrats, the statisticians and social scientists of the early 20th century who created the idea of “good drugs” and “bad drugs”.’ It is the framework of ‘drugs’ itself which needs to be dismantled.” John Doran discussing Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind with the book’s author, Mike Jay. The piece ends with an extract from the book itself. There’s another extract at Nautilus.

• “From the eerie electronics of Earth Calling through to the warp speed crescendo of Master Of The Universe, Space Ritual is like no other live record released at the time or since.” Joe Banks explores the events that led to the recording of the definitive Hawkwind album, Space Ritual, which was released 50 years ago this week.

• “You know, it’s actually all about life, and love, and death, and it’s sexy, and it’s funny and it’s not depressing.” Simon Fisher Turner talking to Emily Bick about Blue Now, a new live staging of Derek Jarman’s final film.

From The Castaway Captives (1934): Mickey Mouse in a deep fix. Ignore the signature, this one was written and illustrated by Floyd Gottfredson.

• New music: Kinder Der Sonne (From Komplizen) by Alva Noto, and S.W.I.M. by Gunnar Jónsson Collider.

• Mixes of the week: Isolatedmix 120 by Lord Of The Isles, and XLR8R Podcast 799 by KMRU.

• Take a radiating, immersive trip into Ay-O’s Happy Rainbow Hell.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: New Queer Cinema 1985–1998 Day.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Hopeless Diamond.

• Rainbow Chaser (1968) by Nirvana | Rainbows (1969) by Rainbows | Rainbow (2006) by Boris With Michio Kurihara

May 10, 2023

Dennis Leigh book covers

Secker & Warburg, 1989.

Most people will know Dennis Leigh—if they know him at all—as John Foxx, the name that Leigh adopted in the 1970s when he was the lead singer and songwriter in Ultravox! (That exclamation mark was a fixture for the group’s first two albums.) Foxx and Leigh maintained parallel careers for a while, or alternating careers in the 1990s when he was working more as an illustrator than as a musical artist.

Routledge/Thomson Learning.

I’ve been asked a few times to consider writing about artists or designers who create covers for literary titles. This is something I often consider myself but the research is never easy. If you’re looking for genre titles you can go to isfdb.org and immediately find entries for hundreds of artists with lists of their credits; Dennis Leigh has an entry there himself. There’s no equivalent source for literary fiction, and nothing for crime novels or non-fiction either. This post is based on a list compiled by a correspondent (thanks, Marc!) to which I added a couple of discoveries of my own. It’s not complete but it ranges through Leigh’s career as a cover artist from the 1970s to the 2000s.

Bloomsbury.

One of the useful things about Dennis Leigh having a more popular alter ego is the amount of interviews in which John Foxx discusses his work outside the music business. While researching this post I found a Smash Hits interview where Foxx mentions having attended Blackpool art college for a short time. This was the same art college that my mother attended in the 1950s, and a place I happily avoided myself. The college is so undistinguished I think Foxx/Leigh may be the only person of any note to have passed through its doors. A more recent interview for Shakespeare Magazine features some discussion of the techniques behind the book covers.

Faber, 1973. Reginald Hill wrote two science-fiction novels as “Dick Morland”, this one and Albion! Albion! (1974). The latter is also listed as having a Leigh cover but the evidence for this is unclear so I’ve not included it.

Missing from this list are covers for novels by Neil Bartlett, Michael Cunningham, Evan Eisenberg, Eva Figes, and Marina Warner, all of which are only available as very low-grade images or not available at all. Another hazard when researching these posts is that artists and designers aren’t always credited, especially on paperbacks, so there may be a few more to be found. Be aware that some covers that might look like Dennis Leigh creations may be the work of somebody else. In the late 80s/early 90s there was a trend for Photoshop montage and what I call “artschool assemblage” (collage riffs on Joseph Cornell and others). If any of the examples here are erroneous attributions let me know.

Faber, 1973.

Vintage, 1990.

Flamingo, 1991.

Flamingo, 1991.

Vintage, 1992.

Flamingo, 1992.

Vintage, 1992.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1993.

Flamingo, 1993.

Sinclair-Stevenson, 1993.

Vintage, 1994.

Vintage, 1994.

Phoenix, 1994.

Orion, 1994.

Bullfinch, 1995.

Minerva, 1995.

Pantheon, 1996.

Instar Libri, 1998.

Phoenix House, 1998.

Harper Perennial, 1999.

Phoenix House 2000.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Holly Warburton record covers

May 8, 2023

Anger Magick Lantern Cycle, 1966

Here’s a rare thing: Kenneth Anger’s programme (PDF) for a Spring Equinox screening of his films in New York in 1966, an event that saw the first public appearance of Magick Lantern Cycle as a collective title. This small publication is described at some length by Bill Landis in the unauthorised Anger biography, while the cover design appears on the first page of the booklet inside the BFI collection of Anger’s films. There are 13 pages in the scan, the original item being a collection of loose sheets inside a folded cover.

Among the many points of interest are Anger’s evocative production notes and dedications for the films, comments which have been recycled ever since in articles about the director and his work. There’s also a page of biographical detail which includes a list of Anger’s preferences and interests, a Crowley-style piece of hyperbolic self-description, and a collage bearing the title The Golden Grope of Marilyn Monroe. The latter features a Gustave Doré illustration which prefigures the appropriation of Doré for the first Lucifer Rising poster.

This being early 1966, LSD was hip and still legal, so the screening information suggests the ideal time for psychedelic voyagers in the audience to ingest their sugar cubes. The evening was to begin with the Anger Aquarian Arcanum, a prelude comprising a display of various magical symbols and iconography. Some writers have taken this to be a lost film but Landis says it was a slide show, presumably with Anger’s explanatory commentary. Enough of the programmes for the event were printed that you can still find them for sale today, although if you want to buy one the cheaper copies start at around £500.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Don’t Smoke That Cigarette by Kenneth Anger

• Kenneth Anger’s Maldoror

• Donald Cammell and Kenneth Anger, 1972

• My Surfing Lucifer by Kenneth Anger

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome: The Eldorado Edition

• Brush of Baphomet by Kenneth Anger

• Anger Sees Red

• Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon

• Lucifer Rising posters

• Missoni by Kenneth Anger

• Anger in London

• Arabesque for Kenneth Anger by Marie Menken

• Edmund Teske

• Kenneth Anger on DVD again

• Mouse Heaven by Kenneth Anger

• The Man We Want to Hang by Kenneth Anger

• Relighting the Magick Lantern

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally

May 6, 2023

Weekend links 672

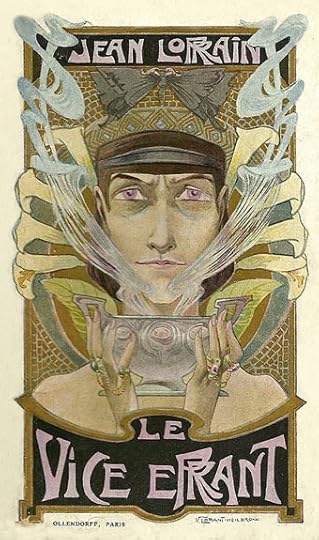

Le Vice Errant (1902) by Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn.

• “So however surreal those cities, the invisible ones that he builds, they have their counterpart in the real. They always have their counterpart in visible cities.” Darran Anderson on Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine on the centenary of The Riddle and Other Stories by Walter de la Mare, with special attention paid to The Vats, a very strange story.

• New music: A Bad Attitude by African Head Charge; Lapsed Gasps by Push For Night + Jon Mueller; Forevervoiceless by Brian Eno.

The strands of medicine, consciousness expansion, intoxication, addiction, and crime were tightly entangled in fin-de-siècle Paris, where ether and chloroform circulated among bohemian demi-mondaines alongside morphine, opium, cocaine, hashish, and wormwood-infused absinthe. These solvents were often carried in small glass vials and medicine bottles by the asthmatic, tubercular, and neurasthenic, added to patent tonics and syrups, and, on occasion, to cocktails: an ether-soaked strawberry floating in champagne produced a heady rush, the fruit preventing the volatile liquid from evaporating too quickly. Literary references to ether abounded, either as a signifier of decadence or as a literary prop to shift a realistic narrative into the landscape of dreams and symbols, where its dissociative qualities became a portal to strange mental states, psychological hauntings, uncanny doublings, and slippages of space and time.

Mike Jay on Jean Lorrain and the ether dreams of fin-de-siècle Paris

• At Aquarium Drunkard: Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan talk about the recording of Silver Haze, their first album as Sqürl.

• James Balmont offers a beginner’s guide to the films of Dario Argento.

• At Unquiet Things: Rachael Bridge’s Luminous, Technicolor Shadows.

• Mix of the week: A mix for The Wire by Erika.

• Ether Ships (1978) by Steve Hillage | Ether (1998) by Redshift | Ether (2000) by Coil

May 3, 2023

The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb

The dark fairy tale turns up often enough in animated film to be a genre of its own, a kind of mutant sibling to the more traditional fare which has been a staple of the medium as far back as Lotte Reiniger. The darkness is especially pronounced in The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb, an hour-long film in which the tale of the tiny boy is combined with that of Jack the Giant-killer. In this version Tom is the product of an accident in an insemination plant, to which he’s returned after being kidnapped by sinister adults, and from which he escapes to join a community of miniature scavengers.

Dave Borthwick’s film owes nothing to the Tim Burton school of Goth fantasy. This is a queasily British take on the Tom Thumb story: kitchen-sink grotesquerie strained through Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and Jan Svankmajer’s savagery; biological experiments, toxic waste, sweating faces, spiders and insects everywhere. There must be more animated houseflies in this film than in any other before or since. The human characters are pixilated throughout, a technique which adds to their lumbering clumsiness while allowing them to blend with the animated figures and other details.

In the previous post I talked about Channel 4’s years of support for underground and experimental cinema. The channel was also a great supporter of animation in its first decade, helping fund films by Jan Svankmajer, the Quay Brothers and many others, as well as regularly screening the kind of child-unfriendly animation which is seldom shown on TV. Having not seen Dave Borthwick’s film since the 1990s I thought this might be another Channel 4 production but it was actually co-funded by the BBC, together with La Sept in France. The BBC’s involvement is surprising considering how weird and unpleasant the film is. The corporation had apparently commissioned a short for their Christmas schedule but turned down the results as unsuitable for the season. (The Christmas connection may explain the detail of a crucified Santa hanging on a wall.) They did, however, agree to help Borthwick and co. make this longer version of the story, a commendable decision that I doubt would pass today. Dave Borthwick died in October last year. His fellow animators regard The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb as his best film. Watch it here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Magic Art of Jan Svankmajer

• Jiri Barta’s Labyrinth of Darkness

• The Web by Joan Ashworth

• Jiri Barta’s Pied Piper

May 1, 2023

Into the Midnight Underground

Browsing Vimeo recently I found a film by Anna Thew, Cling Film, which I remembered seeing years ago on Midnight Underground, a TV series devoted to avant-garde cinema. The series was broadcast by Channel 4 (UK) for eight weeks in 1993, with each episode being screened shortly after midnight. The presenter was the always reliable Benjamin Woolley, sitting before a backdrop resembling one of Verner Panton’s psychedelic environments from where he introduced the cinematic offerings, an eclectic blend of avant-garde and experimental films, unusual dramas plus a couple of animations. Episodes ran for around an hour, with each installment following a different theme. The films were a mix of the old and the new: “classics” (for want of a better term) of underground cinema set alongside more recent works. This was very much a television equivalent of the screenings of avant-garde cinema which Film and Video Umbrella had been touring around Britain’s arthouses since the mid-1980s; one of the founders of FVU, Michael O’Pray, is thanked in the series credits. Midnight Underground was so tailored to my interests at the time it was easy to feel like this was being screened for my benefit alone. I taped everything as it was broadcast but I never got round to digitising all the episodes, so that many of the films shown there, Cling Film included, I haven’t seen for a long time.

Benjamin Woolley.

The discovery of Anna Thew’s film set me wondering whether it would be possible to replicate the contents of Midnight Underground via links to various video sites. Since this post exists, the answer is obviously yes, or almost… Of the 43 films shown in the series only 5 are currently unavailable, with one more being limited to an extract and another as pay-to-view. This was a much better result than I expected, especially for works with such a limited appeal. The majority of the films shown in the series were being screened on British TV for the first time, also the last time for most of them. In 1993 Channel 4 was still maintaining its original brief, offering a genuine alternative to the programming on the other three terrestrial channels. As I’ve often complained here, this didn’t last; the underground remained underground. Woolley’s series was a brief taste of a televisual world where the concept of diversity could apply to form and content as well as identity. It’s a world the corporate channels will never show you, one you have to find for yourself.

* * *

1: Strange Spirits

The opening episode shows why I felt they were broadcasting this for me alone. Derek Jarman’s grainy film of a Throbbing Gristle performance is probably the first (and only?) time the group appeared on British TV. This was the first surprise. The second one was Kenneth Anger’s film being shown with its Janácek score. I’d seen this at an FVU screening a couple of years before with its ELO soundtrack, the so-called “Eldorado Edition”, which Anger later discarded. As for Daina Krumins’ weird and creepy religiose short, I expected this one to be unavailable but the director now has several of her films on YouTube. Don’t miss her even-weirder animated slime moulds, Babobilicons. The angel in Maggie Jailler’s film is artist (and Jarman/TG associate) Cerith Wyn Evans.

• TG: Psychic Rally in Heaven (Derek Jarman, 1981)

• The Divine Miracle (Daina Krumins, 1973)

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (Kenneth Anger, 1954)

• L’ange frénétique (Maggie Jailler, 1985)

2: Music for the Eye and Ear

Bruce Conner’s films are continually elusive on the internet, especially those made to accompany music by Devo and Eno & Byrne. The version of Mongoloid linked here differs slightly from the original but it’s essentially the same film. Versailles II is taped from the Midnight Underground broadcast, and includes Benjamin Woolley’s introduction.

• Eaux d’artifice (Kenneth Anger, 1953)

• Mongoloid (Bruce Conner, 1978)

• Versailles II (Chris Garratt, 1976)

• Stille Nacht II: Are We Still Married? (Quay Brothers, 1992)

• All My Life (Bruce Baillie, 1966)

• Scorpio Rising (Kenneth Anger, 1964)

3: New Sexualities

Stephen Dwoskin’s film is the one that shows a close-up of a woman’s face during the act of masturbation. This is paralleled later in the series by Antony Balch’s masturbatory self-portrait in Towers Open Fire. Cling Film is all about safe sex, and was broadcast in a slightly amended form to avoid being too explicit. The version on Vimeo is uncensored.

• Kiss (Chris Newby, 1992) (no video)

• Kustom Kar Kommandos (Kenneth Anger, 1965)

• Cling Film (Anna Thew, 1993)

• Stain (Simon Pummell, 1992)

• Asparagus (Suzan Pitt, 1979)

• 6/64: Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Mühl) (Kurt Kren, 1964)

• Moment (Stephen Dwoskin, 1969)

4: London Suite

Sundial and Mile End Purgatorio have both appeared here before as a result of my seeing them on Midnight Underground.

• Latifah and Himli’s Nomadic Uncle (Alnoor Dewshi, 1992)

• Sundial (William Raban, 1993)

• The London Story (Sally Potter, 1987) (pay-to-view)

• Mile End Purgatorio (Guy Sherwin, 1991)

• London Suite (Vivienne Dick, 1989) (no video)

5: Little Stabs at Happiness

There are many Robert Breer films online but no sign of Gulls and Buoys, a short animation. Ubuweb has other options.

• Little Stabs at Happiness (Ken Jacobs, 1960)

• Gulls And Buoys (Robert Breer, 1972) (no video)

• Hoi-Polloi (Andrew Kötting, 1990)

• Pull My Daisy (Robert Frank & Alfred Leslie, 1959)

6: The Surreal

Did Midnight Underground give Meshes of the Afternoon its first UK TV screening? Probably. It was the first place I saw it anyway. The same goes for Martin Scorsese’s memorable short made when he was still at film school.

• Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí, 1929)

• Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren & Alexandr Hackenschmied, 1943)

• The Big Shave (Martin Scorsese, 1967)

7: Objects in Motion

Downside Up is another one I’ve linked to before. The Way Things Go seems to get removed as soon as it’s posted anywhere in full but the extract is informative enough.

• Particles In Space (Len Lye, 1966)

• The Way Things Go (Peter Fischli & David Weiss, 1987) (extract)

• Mothlight (Stan Brakhage, 1963)

• Renaissance (Walerian Borowczyk, 1964)

• Shift (Ernie Gehr, 1972–74)

• Downside Up (Tony Hill, 1984)

8: The Sleep of Reason

I was hoping to find a better copy of Towers Open Fire but they all seem to be the same scratched and blurry mess that circulates endlessly. In the 1980s it was enough to see this and the other William Burroughs shorts in any form at all. Today they all seem overdue for restoration if prints still exist somewhere. Bruce Conner made two films scored by tracks from Eno & Byrne’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. America Is Waiting is currently unavailable but Mea Culpa is here (for the time being…).

• Towers Open Fire (Antony Balch, 1963)

• YYAA (Wojciech Bruszewski, 1973)

• Peace Mandala / End War (Paul Sharits, 1966)

• Romantic Italy (Chris Garratt, 1975) (no video)

• America Is Waiting (Bruce Conner, 1981)

• La vache qui rumine (Georges Rey, 1969)

• The Rational Life Films 1-5 (Debbie Lee, 1991) (no video)

• The Return To Reason (Man Ray, 1923)

• Update: Added a link to America Is Waiting.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Sundial and Mile End Purgatorio

• Thot-Fal’N, a film by Stan Brakhage

• Downside Up

• Network 21 TV

• Arabesque for Kenneth Anger by Marie Menken

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers