Brandon Sanderson's Blog, page 28

October 27, 2017

Oathbringer’s Timeline

[Assistant Peter’s note: This post was written back in March by Karen Ahlstrom, but it fell through the cracks while we were working on Oathbringer.]

I just finished the timeline for Oathbringer, and thought you might like to hear about the process. (Spoiler warning: There may be tidbits of information in this article about the plot of Oathbringer, but I have specifically made up many of the examples I use, so you can’t count on any of it as fact.)

I know that some of you think, “Brandon posted that he had finished writing Oathbringer months ago. Why do we have to wait until November before it’s on the shelf at the bookstore?” This is a natural question. I asked it myself years ago when I heard similar news about a Harry Potter book. The timeline is one small part of the reason, but it will give you a small glimpse of what is going on at a frantic pace here at Dragonsteel trying to get the book ready to go to press.

You may know that I’m Brandon’s continuity editor. I keep records of every character, place, spren, and piece of clothing to name just a few. The next time a person appears, I make sure they have the right eye color and eat the right kind of food. There’s so much more to it than that, but it gives you an idea of the level of detail I try to be on top of.

Another thing I track is the timeline of each book. I have a massive spreadsheet called the Master Cosmere Timeline (I can hear some of you salivating right now, and no, I won’t let you peek at certain corners of it).

In some of Brandon’s books, there are a few main characters who spend most of their time together in the same place. For those books, the timeline is simple. Take The Bands of Mourning for instance. It’s about four days long. Nobody goes off on a side quest. The timeline only takes up 32 lines in the spreadsheet because there are that many chapters. On the other hand, the current spreadsheet for the Stormlight books has over 1100 lines.

Here’s a sample of the timeline spreadsheet. The white columns are the dates, which I have an entirely separate post about. In column F we have an event that happens in the book. Column E tells how long it has been since the last event. Then I have the quote from the book that I used to justify the timing, the chapter the quote appears in, and whether the event happened on the day of the chapter, or sometime in the past or future.

The timeline for Oathbringer starts on day 4 of the new year, and ends on day 100. (Which, for those of you who keep track of such things, makes the date 1174.2.10.5). My day count could change by a day or two here and there, but I’m pretty happy with how I got the different groups of people to all end up in the same place at the same time.

Why bother? Well, sometimes Brandon writes a flashback and someone is looking at a cute baby. It’s important to tell Brandon that this particular kid wasn’t born for another four years. A character might think to themselves, “It’s been a month and a half since I was there,” and though it has been 45 days, a month on Roshar is 50 days long, so it hasn’t even been a single month. Brandon often glosses over those conversions in early drafts.

The most important purpose, though, comes when two groups of characters are apart for some length of time. Let’s take Kaladin and Dalinar in The Way of Kings. Kaladin was running bridges for battles where Dalinar and Sadeas cooperated. Were there the same number of days in Kaladin’s viewpoint between those battles as there were in Dalinar’s viewpoint? The answer is no. I was assigned this job after that book was finished, and as much as we squashed and fudged, there is still a day or two unaccounted for. An interesting tidbit from The Way of Kings‘ timeline is that Kaladin’s timeline has 50 days in it before Dalinar’s starts. Chapter 40, when Kaladin recovers from being strung up in the storm, is the same day as the chasmfiend hunt in Chapter 12.

Going back to Oathbringer, sometimes I’m amazed at the power I have. As I go through the manuscript, I can take a sentence like, “He spent four days recovering,” and simply replace the word four with two. Brandon gives me a general idea of how long he wants things to take, and I tell him what it needs to be to fit. It’s a big responsibility, and sometimes I worry that I’ll mess the whole thing up.

Oathbringer is the first book in the Stormlight series where I worked with a list of the storms from the start. Peter tried on Words of Radiance, but Brandon wrote what the story needed and expected us to fit the storms in around that (A perfectly reasonable process, even if it makes my job trickier). In Oathbringer though, the Everstorm and highstorm are each on a much stricter schedule. We need such exact timing in some scenes that Peter (with help from beta reader Ross Newberry) made me a calculator to track the hour and minute the storms would hit any given city.

Yet another thing we needed to calculate is travel time. How fast can a Windrunner fly? How many days does it take to march an army from here to there? Kaladin might be able to do a forced march for a week, but what about Shallan or Navani? How long could they manage 30 miles a day?

Hopefully now you can see why we’ve needed months of work to get this far, and will need months more to get it finished in time. At some point, we’re just going to have to call it good and turn the book over to the printer, but even though you think you want to get your hands on it now, it will be a much better read after we have the kinks worked out.

Annotation The Way of Kings Chapter 4

This chapter in particular was a challenge to write. My experience with Sazed in The Hero of Ages warned me that a character deep in depression can be a difficult and dangerous thing to write. Depression is a serious challenge for real people—and therefore also for characters. Additionally, it pushes a character not to act.

Inactive characters are boring, and though I wanted to start Kaladin in a difficult place, I didn’t want him to be inactive. So how did I go about making scenes of a depressed fallen hero locked in a cage interesting and active? The final result might not seem like much in the scope of the entire novel, but these chapters are some of the ones I’m the most proud of. I feel I get Kaladin and his character across solidly while having him actually do things—try to save the other slave, rip up the map, etc.

Syl, obviously, is a big part of why these scenes work. She is so different from the rest of what’s happening, and she has such stark progress as a character, that I think she “saves” these chapters.

You might be interested to know, then, that she was actually developed for a completely different book in the cosmere. I often speak about how books come together when different ideas work better together than they ever did separate. Kaladin and Syl are an excellent example of this. He didn’t work in The Way of Kings Prime, and her book just wasn’t going anywhere. Put them together, and magic happened. (Literally and figuratively.)

October 25, 2017

The Way of Kings Chapter 13 (D)

One of Brandon’s largest revisions in the early writing of the 2010 version of The Way of Kings was a restructuring of Dalinar’s first chapters. The reaction from Brandon’s writing group after they finished reading the chapters from Part Two in the first week of 2010 let him know about several issues: Dalinar came across as wishy-washy and contradictory, and the pacing of his chapters was boring. Brandon’s solution was to rewrite many of the scenes from Adolin’s point of view as well as reordering events here, trimming there, expanding here. We’ll now share a few of these original chapters, which you can compare to the published version.

This chapter corresponds to parts of chapter 12 and chapter 15 in the final book.

It was a clear day, storm-free, the white sun blazing unabashedly without clouds to veil its face. A warm day, an honest day. A day to slay a god.

Dalinar rode Gallant at a gallop across the plateau, hoofbeats pounding the stone, rock formations whipping past. His armor clinked as he leaned down, faceplate open, face to the wind. The enveloping Shardplate was inexplicably easy to move in, and was invigorating to wear. Men who hadn’t ever worn a suit of it—particularly those who were accustomed to its inferior cousin, simple plate and maile—could never understand. Shardplate wasn’t simply armor. It so much more.

Ahead, a steep rock formation rose from the plateau like a small tower of stone. When he got near, Dalinar threw himself from the saddle while Gallant was still moving. He hit hard, but the Shardplate absorbed the impact, stone crunching beneath his steel feet as he skidded to a stop. It was a reckless move, but wearing his Plate made him feel twenty or thirty years younger. Perhaps that was why he found excuses to don it so often.

He charged to the base of the rock formation as another horse galloped up behind. Dalinar jumped—Plate legs propelling him up some five feet—and grabbed a handhold in the stone. With a heave, he pulled himself up, the Plate lending him the strength of many men.

He smiled at the thrill of the chase—nearly as grand as the thrill of battle—and grabbed another ledge, climbing. Rock scraped below. Elhokar had begun to climb as well.

Dalinar didn’t look down. He kept his eyes fixed on his goal: the small, flat section of rock at the top of the twenty-foot high formation. He quested with steel-covered fingers, finding another handhold. The gauntlets covered his hands, but the ancient armor somehow transferred sensation to his fingers. It was as if he were wearing only thick leather gloves.

After a short time, scraping came from the side, accompanied by a voice cursing softly. Elhokar, the king, had taken a slightly different path, hoping to pass Dalinar. However, Elhokar had found himself at a section of rock without handholds above, and his progress was stalled.

The king’s golden Shardplate glittered as he glanced at Dalinar, meeting his eyes. Elhokar set his jaw and looked upward, then launched himself in a powerful leap toward an outcropping.

Fool boy, Dalinar thought, watching the armor-laden king hang in the air for a moment before snatching the handhold, dangling, cape flapping below. The king heaved himself up, continuing to climb.

Dalinar began climbing furiously, stone grinding beneath his metal fingertips, chips falling free and bouncing against the sides of the formation. Wind played at his blue cloak. He heaved, strained, pushed himself, and managed to get just ahead of the king.

The top was just feet away. He reached for it, determined to win. He couldn’t lose. He had to—

No, he told himself forcefully.

He made himself hesitate just briefly, letting his nephew get ahead and haul himself to his feet atop the rock formation. Elhokar laughed in triumph, turning toward Dalinar, holding out a hand to help him up. “Stormwinds, uncle, but you made a fine race of it! I thought for certain you had me at the end there.”

Dalinar smiled, then took the younger man’s hand, letting Elhokar pull him up onto the top of the formation. There was just enough room for them both. Breathing deeply, Dalinar slapped the king on the back, metal clanking. “Nicely played, your majesty.”

The king beamed. That was encouraging to see; Elhokar’s mood had been so dark lately. A success—even at something as simple as a this race—might do him some real good.

Dalinar took a deep, satisfied breath, turning to look eastward. From this height, he could scan a large swath of the Shattered Plains. He studied them, trying to pick out their destination. As he did so, however, he had an odd moment of recollection. He felt as if he’d been atop this platform before, looking down at a broken landscape.

He frowned to himself. He’d never been on this particular formation before, had he? The moment was gone in a heartbeat.

He shook his head, glancing at the king. Elhokar’s golden Shardplate gleamed in the noon-day sun; it had belonged to his father before him, though Elhokar had ordered the blacksmiths to weld a golden, crown-shaped set of steel horns to the top of his helm. Men often made such modifications to their Plate. Dalinar himself left his unornamented and unpainted; he preferred the simple, dark slate color.

Elhokar had his faceplate up, revealing a prominent nose and an almost too-pretty face, with full lips and delicate features. Gavilar had looked like that too, before he’d suffered a broken nose and that terrible scar across his face. The young king had proud eyes—perhaps a little too proud—and a clean-shaven face that seemed top-heavy, with that broad forehead and small chin.

Elhokar raised his hand and shaded his eyes. Behind, Dalinar’s soldiers and Elhokar’s attendants rode up to the base of the rock formation. Dalinar noted his outriders on the next plateau over, holding position and waiting for the bulk of the army to catch up.

“We must have seemed of the ten fools, charging across the ground like that,” the king said. “Maybe we shouldn’t have left our bodyguards.”

“You’re safe, Elhokar. I have men watching every nearby plateau. We’ll know if the Parshendi try to strike.

“I’m not worried about the Parshendi,” Elhokar said, expression becoming grim. “I just…I don’t like being exposed.”

Dalinar didn’t reply. This nervousness of the king’s was a new development, but could Elhokar really be blamed, considering what had happened to his father? True, it had been five years, and Dalinar doubted that the Assassin in White was going to return now. But, then, he hadn’t anticipated the assassination in the first place.

I’m sorry, brother, he thought. He did so every time when he thought of the night when Gavilar had died. Assassinated while Dalinar lay in a drunken stupor.

“Well,” the king said. “I’m glad you suggested the race. It felt…good to let myself go.”

Dalinar smiled. “For a moment there, I felt like a youth again, chasing after your father on some ridiculous challenge.”

Elhokar drew his lips to a thin line. Mentioning Gavilar soured him, as if he felt that others were comparing him to the old king.

Most of the time, he was right, unfortunately.

“There,” Elhokar said, pointing with a golden, gauntleted hand. “I can see our destination.”

Dalinar shaded his own eyes, finally picking out a canopy six plateaus away, flying the King’s flag. Wide, permanent bridges led there; they were relatively close to the Alethi side of the Shattered Plains, on plateaus Dalinar himself controlled.

His plateau. His chasmfiend. His hunt. The massive, greatshelled creatures were one of the main motivations behind the Vengeance Pact, at least for most of the highprinces. Elhokar and Dalinar fought for revenge; for the rest, it was about gemstones.

And, in truth, Dalinar himself couldn’t deny the allure of the wealth offered here.

“Your count was accurate,” Elhokar said, lowering his arm, frowning faintly. “You were correct again, uncle.”

“I try to make a habit of it.”

Elhokar snorted. “I can’t blame you for that, I suppose.”

The wind blew across him, and once again, Dalinar had a moment of recollection. Had he been atop this formation before? It seemed so familiar.

No, he thought. It wasn’t here. It was a different peak I stood upon. I saw it during….

During one of his episodes. The very first one. You must unite them. The strange, booming words had told him. The Final Desolation comes….

“Uncle?” Elhokar asked.

Dalinar shook out of his revelry, focusing back on the king. “Yes, your majesty?”

“Did you look into the item I asked you about?”

“I did. None of the guards saw anything.”

“There was someone watching me. In the darkness that night.”

“If so, they haven’t returned, your majesty.”

Elhokar seemed dissatisfied, but let the matter drop. The winds blew across Dalinar again, bringing with them that faint familiarity. Atop a peak, looking out at destruction. A sense of awful, terrible, amazing perspective.

Unite them…. Prepare them….

“Your majesty,” Dalinar found himself saying. “Have you given any thought to how long we will stay at this war?”

Elhokar started, looking surprised. “We’ll keep fighting until the Vengeance Pact is satisfied and my father avenged!”

“Noble words,” Dalinar said. “But you majesty, you’ve been away from Alethkar for five years now! Maintaining two distant centers of government like this…it stresses our means.”

“Kings often go to war for extended periods, Uncle.”

“Rarely do they do it for so long,” Dalinar said, “and rarely do they bring every Shardbearer and Highprince in the kingdom with them. Our resources are strained, and word from home is that the Reshi border encroachments grow increasingly bold.”

Elhokar sniffed, wind blowing at them atop the peaked rock. “Uncle, I can’t believe I’m hearing this! You aren’t seriously suggesting that I abandon the war, are you? You’d have me slink home, like a scolded axehound? Let those savages get away with killing your brother?”

Dalinar hesitated. What am I saying? he thought, suddenly mortified. Abandoning the war? What of the Rabaka, and the need to prepare the souls of men to fight after death? It was a very un-Alethi thing to say.

“Of course I’m not saying we should give up the war, your majesty,” Dalinar said quickly. “Don’t be foolish.”

Elhokar eyed him.

“All I’m saying,” Dalinar continued, “is that we should speed the course of the conflict. I’m tired of Gavilar’s murderers continuing to live free. Can we not encourage the highprinces to stop dallying? Elhokar, they see this war as a game!”

Elhokar appraised him for a moment, then sniffed to himself. “The situation keeps them competitive, and that keeps them focused. If their attention is on winning plateaus, then they don’t spend so much time plotting against one another.”

“I think you give them too little credit,” Dalinar said. “They can do both quite easily at the same time.”

“Bah,” Elhokar said, “you’re just being paranoid.”

Dalinar blinked. Paranoid? He’s calling me paranoid? He couldn’t find the words to respond.

“I must say, uncle,” Elhokar said, looking out over the plains, “I find your odd behavior lately to be disturbing. It has something to do with those…episodes of yours, doesn’t it?”

He gritted his teeth. “They are unimportant, Elhokar.” The words came out stiffly.

The king glanced at him, then nodded. “I’m sorry to bring it up then. Come, let’s get on with the hunt. It will do good for us both.” With that, the king leaped off the top of the rock formation.

Dalinar cursed, leaning over the side, watching the king plummet to the ground. Elhokar landed with an audible crack, throwing up chips of stone and a large puff of Stormlight. But he but managed to stay upright.

Fool boy, Dalinar thought, though the king—at twenty-five—was hardly a boy. He just acted like one at times. Elhokar worried about assassins in every shadow, yet took foolish risks like jumping too far or rushing into battle.

Dalinar took a safer path, climbing down to a lower ledge before jumping. His landing was still jarring, though the Plate softened the stress to his legs and knees.

Nearby, Elhokar climbed into his saddle. His brilliant white horse, Vengeance, was not a Ryshadium—and that was a source of some bitterness to the king. Many men thought that a Shardbearer was not complete until he had all three—Blade, Plate, and steed.

The third was a foolish requirement. Ryshadium could not be forced. They chose their riders, and one counted himself fortunate if picked. Dalinar made his way over to Gallant—who waited patiently where his reins had been dropped—and patted the midnight-colored stallion on the side of the neck. Gallant was a good two hands taller than any other warhorse in the army, a powerful stallion with the bulk and solidity of the finest draft horse yet the speed of a Shin gallhorian.

Was there was a playful look to Gallant’s eyes as he turned to regard Elhokar? It almost seemed as if the animal was amused by the interactions of men. Just my imagination, Dalinar thought, swinging himself into the saddle. Ryshadium were smarter than other breeds of horse, true, but they were still only animals.

He trotted Gallant toward the main body of troops and attendants. Highprince Sadeas—wearing red Shardplate—was with them. With a square of jaw and angular of face, he cut an imposing figure, his Plate ornamented nearly as much as that of the king. He looked much better in it than he did when wearing one of those ridiculous costumes of lace and silk that were popular these days.

Sadeas had the Plate only, no Blade, making him half of a true Shardbearer. One did not point out this deficiency to Sadeas, however—at least not if one wished to avoid a duel.

Sadeas caught Dalinar’s eyes, nodding slightly. My part is done, that nod said.

Dalinar turned to seek out Vamah. As he did, however, a different shardbearer up beside him: Adolin, Dalinar’s elder son. He, Elhokar, Dalinar, and Sadeas were the only Shardbearers on this particular hunt.

“Ho, father,” Adolin said. “Have a nice run?”

“Gallant did most of the work.”

Adolin smiled. He was shorter than Dalinar, and his hair—hidden by his helm—was blonde mixed with black, an inheritance from his mother. At least, so Dalinar had been told. Dalinar himself remembered nothing of the woman. She had been excised from his memory, leaving strange holes, fuzziness where he should be able to recall her face. In places, he could remember an exact scene, with everyone else crisp and clear. But she was a blur. He couldn’t even remember her name. When others spoke it to him, it slipped from his mind, like a pat of butter sliding off of a too-hot knife.

Best not to focus on that, he thought to himself, scanning the line of troops. Renarin—Dalinar’s other son—sat a distance off, solemn, as usual. He was unarmored; he wasn’t Shardbearer. What did his too-quiet, beskpeckled eyes see? He always seemed to be lost in thought.

“How are the troops?” Dalinar asked, turning back to Adolin.

“Father,” Adolin said flatly, “how do you think they are? You left five minutes ago.”

“I know. How are the troops?”

Adolin sighed. “Fit and excited to be on with killing a greatshell. Father, I don’t see why anyone needs to command of a simple march from plateau to plateau.”

“You need experience leading and they need to learn to see you as a commander. I won’t live forever.” The two thousand spearmen and archers on the hunt were from Dalinar’s army; Highprinces Sadeas and Vamah had had brought only a small honor guard each.

The line of troops, four men wide, wound like an eel back across the plateau. “You should be excited,” Dalinar said, turning Gallant. He began riding toward the bridge, Adolin falling in beside him. “When I was your age, I always got the jitters when hunting a greatshell. It was the highlight of a young man’s year.”

Adolin shrugged. “I just can’t see that how hunting an oversized chull could ever be as exciting as a good duel.”

“These ‘oversized chulls’ grow to fifty feet tall.”

“Yes,” Adolin said, “and we’ll sit, baiting it for hours, baking in the hot sun. If it decides to show up, we’ll pelt it with arrows from a distance, only closing in once it is so weak it can barely resist as we hack it to death with Shardblades. Very honorable.”

“It’s not a duel,” Dalinar said, “it’s a hunt. A grand tradition.”

Adolin raised an eyebrow at him.

“And yes,” Dalinar added with a sigh. “It can tedious at times.”

Adolin chuckled. He was a full Shardbearer, having won his own Shardblade in a duel and earned a Ryshadium on his first try. The Plate was a family suit, inherited from Dalinar’s wife’s side of the family.

There were fewer than two dozen full Shardbearers in the entirety of Alethkar, and Adolin was their youngest. He’d managed the feat at a younger age, even, than Dalinar had. The trouble with being parent to an accomplished child, he thought, smiling. We cheer for them when they succeed, but that doesn’t stop us from feeling obsolete.

He was proud of Adolin. Of course, the lad did like to complain. Too bad there aren’t any young women around. The scribes in attendance were older women, and Adolin was always more enthusiastic about duties when there was someone young and female to impress.

“Go and lead the crossing,” Dalinar said. The army was making its way across the permanent bridge to the next plateau.

“I’m hardly needed there, you know.”

“The king is in our attendance,” Dalinar said. “The codes say it is our duty to secure the area before he moves onto it.” It was a lesser part of the Codes, requiring one to go before the king. It just a formality here, as these plateaus were far from the front lines. But it was best to be careful.

Adolin sighed, but knew better than to argue when the Codes were involved. He rode off to lead a team onto the next plateau, where he would check personally to be certain it was safe for the king.

Dalinar had other business to be about. Nearby, the king’s attendants—resignedly accustomed to Dalinar’s strict care for such things—had gathered to wait for the all clear. There were servants to carry food and water, women to act as scribes, and lesser lighteyed men who had obtained enough favor to be invited. Most of the last group were unarmored, wearing dark, masculine colors. Maroon, navy, forest green, deep burnt orange.

Dalinar rode past Sadeas and his bubble of attendants, not looking at the man directly. Did he ornament his Plate so in order to draw attention from the fact that he had no Blade? Many men felt the Blade to be the more superior of the two Shards—though if Dalinar had to give one of the two up, he’d keep the Plate. Men respected the sword for its offensive power, but those types never did understand the strength of a good defensive stance.

Sadeas also didn’t ride a Ryshadium, which wasn’t expected. They were said to look into the hearts of men when choosing riders.

That was unfair of you, Dalinar thought at himself. Sadeas had been a friend, once. They were still allies, tied together in one, powerful emotion.

Guilt.

Dalinar rode on past Sadeas, approaching Highprince Vamah. He was dressed in a fashionable long brown coat that had slashes cut through it to expose the bright yellow silk underneath. The cuts had been put there intentionally; it was supposed to be a subdued kind of fashion, not as flagrant as wearing the silks on the outside. Dalinar just thought it looked stupid.

Vamah himself was a round-faced man who wore his hair cut close to hide his patches of baldness. The short hair that remained stuck straight up. He also had a habit of squinting—which he did as Dalinar rode up.

“Brightlord,” Dalinar said, nodding. “I have come to make certain your comfort has been seen to.”

“My comfort would be best seen to if we could move on with this hunt.” Vamah glared up at the sun overhead, as if blaming it for some misdeed. In likelihood, his foul mood was due to the meeting he’d had with Sadeas earlier on the ride. “Really, Dalinar, must you be so tiresome as to insist that we wait every time we reach a bridge?”

“I like to be careful,” Dalinar said. Vamah was a highprince; he, of all people, should have understood the importance of the Codes. Yet there he sat, out of uniform on a battlefield, complaining about precautions taken to protect the king.

Dalinar said nothing of Vamah’s lapses. The highprinces had complained about the Codes even when Gavilar had been king, and they weren’t about to follow them without direct enforcement. And, as Elhokar himself thought them overly strict, that wasn’t about to happen any time soon.

“It’s a good day for a hunt,” Dalinar said, nodding toward the clear sky.

“I suppose.”

“I hear you’ve had success catching several chasmfiends on your own plateaus. You are to be congratulated.”

Vamah shrugged. “They were small things, barely ten feet long. Not like reports of today’s beast.” His voice indicated skepticism regarding those reports.

“Well, a small gemheart is better than none,” Dalinar said politely. “I hear that you have plans to augment the walls of your warcamp.”

“Hum? Yes. Fill in a few of the gaps, turn it into a real fortification.”

“I’ll be certain to tell his majesty that you’ll need access to the soulcasters.”

Vamah turned to him, frowning. “Soulcasters?”

“For lumber,” Dalinar said, raising an eyebrow. “Surely you don’t intend to fill in the walls without using scaffolding? Out here, on these remote plains, it’s fortunate that we have Soulcasters to provide things like wood, wouldn’t you say?”

“Er…yes,” Vamah said, expression darkening further.

“I’d say the king is quite generous in allowing access to the Soulcasters. Wouldn’t you agree, Vamah?”

“I understand your point, Dalinar,” Vamah said dryly. “No need to keep slamming the rock into my face.”

“I’ve never been known as a subtle man, brightlord,” Dalinar said, nodding. “Just effective.” He turned Gallant, trotting away, leaving Vamah to stew. The man had been heard complaining vocally about the tariffs that Elhokar charged to use his Soulcasters. It was the primary form of taxation the king levied on the highprinces out here on the Shattered Plains. Elhokar himself didn’t fight for, or win, plateaus; he stood aloof from that aspect of the war, as was appropriate.

Soon, Adolin’s soldiers on the other plateau called the all clear. The lighteyes were finally allowed to cross over, and Elhokar lead his attendants first. Sadeas lingered, and Dalinar made his way over to the crimson-armored man. They turned their horses beside one another, riding slowly in the same direction.

“Dalinar,” Sadeas said, eyes forward.

“Sadeas.” Dalinar kept his voice controlled and curt.

“You spoke with Vamah?”

“Yes,” Dalinar said. “He saw through what I was doing.”

“Of course he did,” Sadeas said, a hint of amusement in his voice. “I wouldn’t have expected anything else from you, old friend.

To the side, Vamah watched the two of them ride past. Earlier, Sadeas had approached him, explaining that he was going to have to raise what he charged for lumber. As Sadeas controlled the only large forest in the region, the only other way to get wood was through the king’s Soulcasters.

Vamah’s expression was as thunderous as a highstorm. He likely though the only reason he’d been invited on the hunt was so that he could be maneuvered by Sadeas and Dalinar. He was right.

“Will it work?” Dalinar asked.

“If it doesn’t, we’ll think of something else. But I think it will serve as a strong enough reminder. Vamah is an agreeable enough fellow, when prodded. He just needed to remember how fragile his position is.”

All of the talk about wood was, of course, metaphoric. Vamah’s army—and all of the armies—were fed using Elhokar’s Soulcasters, which could turn rocks into grain. That grain was sold at a high price, but the highprinces had no choice but to buy it. Running a supply line all the way back to Alethkar would have been even more expensive.

“Perhaps we should tell Elhokar about these sorts of things,” Dalinar said, glancing at the king, who had joined Vamah and was chatting with him, oblivious to what Dalinar and Sadeas had done.

Sadeas sighed. “I’ve tried; he hasn’t a care for this sort of work. Leave the boy to his own preoccupations, Dalinar. His are the grand ideals of justice, holding the sword high as he rides against his father’s enemies. This kind of work would simply dishearten him.”

“Lately, he seems less preoccupied with the Parshendi,” Dalinar said. “And more worried about assassins in the night. The boy’s paranoia worries me. I don’t know how he’s come about it.”

Sadeas laughed, causing Dalinar to turn.

“You don’t know where he comes about it?” Sadeas asked, still laughing. “Dalinar, are you serious?”

“I’m always serious.”

“I know, I know. I needn’t even have asked. But surely you can see where the boy comes by it!”

“From the way his father was killed?”

“From the way his uncle treats him! Two thousand guards for a simple hunt well within the army’s defensive perimeter? Halts on each and every plateau to let soldiers ‘secure’ the next one over? Really, Dalinar?”

“I like to be careful.”

“Others call that being paranoid!”

“The codes—”

“The codes are a bunch of idealized nonsense,” Sadeas said, “devised by poets to describe the way they think things should have been.”

“Gavilar believed in them.”

“And look where it got him.”

“And where were you, Sadeas, when he was fighting for his life?”

Sadeas rolled his eyes, ornamented crimson helm reflecting sunlight. “So we’re going to fight now? Like old lovers, crossing paths unexpectedly at a feast?”

Dalinar clenched his teeth, forcing down his anger. “It was not Gavilar’s fault,” he said, “nor the fault of the codes, that he ended where he did. It was our fault. Yours and mine. We both know this.”

Sadeas turned away from him, but—after a moment—nodded curtly. Gavilar was gone. Both blamed the other for that, but at the same time, they both blamed themselves as well. The only thing they had left of the king that had united them, the king that had inspired them, was a son.

“I’ll protect the boy my way,” Sadeas said. “You do it your way. But don’t complain to me about his paranoia when you insist on wearing your uniform to bed, just in case the Parshendi suddenly decide—against all reason and precedent—to attack the warcamps. ‘I don’t know where he gets it’ indeed!”

Dalinar gritted his teeth, turning away. “Let’s get on with this hunt.” He flipped his reins, urging his horse forward, leaving Sadeas behind.

“Dalinar,” the other highprince called from behind.

Dalinar hesitated, looking back

“Have you found it yet?” Sadeas asked. “Why he wrote what he did?”

Dalinar his head. Brother. You must find most important words a man can say.

They’d destroyed the sentence as soon as they’d found it. Had it been some kind of profane trick played by the assassin, or had Gavilar actually known how to write, defiling himself by practicing a feminine art?

And if it was a trick, then how had the assassin known to write out a quote from Gavilar’s favorite book? A book nearly everyone else in Alethkar scorned?

“You’re not going to find the answer,” Sadeas said. “It’s a foolish quest, Dalinar. One that’s tearing you apart. I know the what happens to you during storms. Your mind is unraveling because of all this stress you put upon yourself.”

Dalinar said nothing to that. He just turned and continued to ride across the bridge.

October 23, 2017

Dragonsteel Prime Chapter 37: Bridge Four 7

This chapter comes from the 2000 draft of a book called Dragonsteel. Some of the settings, situations, and characters were repurposed into The Way of Kings (2010).

As soon as Jerick stepped into Ki Tzern’s camp he realized all his assumptions about armies in the Eternal War had been wrong. He had based them on the single, faulty example of Demetris’s camp. Walking through the Tzend camp’s structured ranks, Jerick was able to see what a true army was supposed to look like.

The buildings were all sturdy, permanent structures, as opposed to shacks and tents, with a wooden palisade around the perimeter to serve as both a means of defense and a reminder of place. The guards who stood at the gate’s doors wore uniforms that were without wrinkle or stain. There even appeared to be a temple to the Lords near the center of the camp.

A messenger had been sent ahead to warn of Tzern’s arrival, and a group of healers rushed out to collect the wounded as soon as the camp came into view. The unwounded soldiers saluted one last time to Tzern as they entered the camp; then their officers dismissed them, and they went their different ways. Jerick’s bridgemen, uncertain what else to do, simply followed Tzern’s white and gold form as he walked through the gate.

As they passed into the camp, the sense that this army was a place of order impressed itself upon Jerick. The buildings stood in neat rows, men practiced in formal ranks and sparred in neatly roped-off squares. It was also a place of camaraderie. Men were seen talking in groups—not wandering packs, like in Demetris’s army, but friendly gatherings. Most importantly, Jerick realized that for most of the men he saw, those who were not in uniform, he couldn’t tell if they were bridgemen, footmen, or officers.

They paused after walking just a brief distance, waiting as Tzern met with a group of rushed, worried attendants.

“It’s paradise,” Kep whispered beside him, scanning the camp.

Gathban chuckled. “Perhaps not paradise, but definitely an improvement.”

As Jerick’s men were ingesting their new surroundings, Ki Tzern turned from his adjuncts and waved them over. “Men of the Fourth Bridge,” he said, “I welcome you to my camp. I’m going to assign you to the north division, but for now consider yourselves on leave. After today’s ordeal—not to mention the time you spent with Demetris—you’ve earned it.”

The men regarded Tzern with confusion for a moment. “Leave?” Gathban finally said.

Tzern smiled slightly. “Yes, leave. You’re on vacation. You’ll still get paid, but for the next two weeks you won’t be required to go on any runs. Farrle here will lead you to your quarters.”

A soldier to the side nodded, waving for the crew to follow. They stood for a moment, stunned at the idea of an extended break. Before leaving, they paused, turning collective eyes on Jerick.

“Go ahead, men,” Jerick said, a quiet knot of sorrow twisting in his chest. He knew that would be the last order he ever gave to Fourth Bridge. “You will be well-cared for here.”

Dente cleared his throat. “It was a pleasure, sir.”

Jerick nodded, uncertain how to respond. “I . . .”

“It’s all right, sir. You don’t belong in a bridge crew,” Gathban said in a subdued voice.

“A man belongs where he finds friends, Rock,” Jerick said, resting his arm on the enormous man’s shoulder. “I would rather be a bridgemen with the lot of you than a noble in any king’s palace. Take good care of them, Rock.”

Fourth Bridge stepped back and saluted in one silent motion. Their actions weren’t as fluid or as sharp as those of the soldiers from Tzern’s camp. However, there was no less respect in their eyes. Jerick watched them go, following with his eyes until they disappeared.

“I fear you’ve made me a liar, young Jerick,” Tzern said beside him.

“My lord?”

“I once claimed that no good thing could ever come from Demetris’s training.”

“It almost didn’t, sir,” Jerick responded quietly. “The battle we fought today was little more than sparring when compared to what we had to go through to make Bridge Four what it is.”

Tzern nodded, understanding, as he turned to his waiting adjuncts. “The east division is to go on immediate leave for the next two weeks. After that, begin to rebuild it with new recruits and transfers. Don’t send it on any difficult runs for at least three weeks.”

“Yes, my lord,” a tall man in a white and gold uniform answered.

“Leave. . . .” Jerick said again, shaking his head. In Demetris’s camp there had been no such thing—at least, not for bridgemen.

“Yes,” Tzern said, beginning to walk again as his adjuncts dispersed, “you aren’t the only one to notice a little free time improves morale, young Jerick.”

“Sir!” a voice said. A man, shorter than any Jerick had even seen before, was scurrying down the camp’s main path. He looked like a child, but he had the face of an adult. His legs were short and stumpy, and he wore a simple white outfit.

The tiny man puffed as he approached, moving quickly. “Sir, the bridges?” He spoke with an accent that was sharp and irregular, almost unintelligible. Compared to this man, Tzern spoke Fallin almost as if he had lived in Yolen all his life.

Tzern shook his head. “We lost all four, Sung,” he replied.

“By the Lords!” the little man wailed in despair. “It is a miracle!”

“You mean disaster, Sung,” Tzern corrected.

“Yes, a disaster,” the little man cried. “What will we do?”

“I’m certain you can make us some more, Sung,” Tzern reminded.

“Not unless we get more wood,” the little man said, walking in circles, anxiety coating his face. “What with the disturbance up north, our supplies are plentiful.”

“The supplies are depleted, not plentiful, Sung,” Tzern corrected, informing him of the proper Fallin word.

“Yes, that too!” the little man groaned.

“I don’t suppose you’ve had word from Dellanios?”

“No, sir. Not in months.”

Tzern cursed quietly. “Where is that man? He always disappears when we need him most. Well, just get to work on some new plans, Sung,” Tzern requested. “We need a mechanism to lock the wheels, otherwise the Sho Del will just push them into the chasm every time.”

“Yes sir. A locking mechanism! Of course, that would be completely frivolous! I shall get to work on it immediately.”

With that the tiny man hurried away. Tzern just shook his head, waving for Jerick to follow him.

Jerick nodded, walking down the path beside the general. Eventually they arrived at a rectangular, one story building. Inside was a table with a large map of the Shattered Plains on its top, a smaller table with colored stones on it, and several chairs—not stools, but actual chairs. Tzern took one of these, and gestured for Jerick to take another.

“Now, young Jerick,” Tzern said contemplatively. “You are going to answer some questions for me. First of all, I want to know why the son of a nobleman is pretending to be a common bridgeman.”

Jerick looked up with surprise, objection in his voice. “My lord, I—”

Tzern held up a hand, cutting Jerick off with a gesture and a commanding look. “Understand,” Tzern warned, not dangerously, just firmly, “one thing I expect from all who serve under me is the truth. No amount of bravery or ability to lead will help you in this camp if I cannot trust you.”

“I understand, sir,” Jerick said frankly. “But, I am not a noble.”

“A bastard son, then?” Tzern asked. “Raised by a guilty father, then expelled when you became an embarrassment?”

“No, sir,” Jerick said, pulling out his castemark. “I am a lumberman, though I was trained in the palace of King Rodis of Melerand.”

“I find that difficult to believe, young Jerick, castemark or no,” Tzern said, his voice contemplative. “My homeland may be Tzendor, but I know enough about Yolish politics to be aware of caste temperaments.”

“What this youth says is true, my lord,” a new, familiar voice said from the area of the doorway.

Jerick’s head snapped around. “Frost!” he exclaimed enthusiastically.

The old scholar bowed slightly. “Young Master,” Frost simply returned.

“This is the one you’ve been following, Frost?” Tzern asked with a musing smiled. “Interesting.”

“No doubt, my lord,” Frost said, entering the short-ceilinged room. “I am very curious to know where you found him.”

“Actually, he found me,” Tzern replied. “But that is a story for another time. A lumberman raised in the king’s palace. You must be a special young man.”

Jerick shrugged. “That is where life took me, my lord.”

Tzern didn’t answer immediately, instead sitting with a contemplative look on his face. “All right, then, Jerick,” he finally said. “Now that is resolved, perhaps you can answer a more perplexing question for me. How, in the middle of a cloudless day, did a bolt of lightning strike down that Shen Da rider just before it killed you?”

Jerick felt himself grow cold. “I don’t know, my lord,” he answered truthfully.

“I listened to your men as we marched back to the camp,” Tzern continued. “They say the White One himself attends and protects you.”

“The priests say he watches over all of us,” Jerick responded.

“Isn’t it curious, then,” Tzern continued, “that lightning is not the tool of Oren, but of his brother Keth the Black?”

Tzern’s eyes caught Jerick’s and held them for a long moment, as if searching for something. Finally, the tall Tzend turned away. “Regardless, one thing is obvious. You are no average lumberman. I saw you jump through the center of that Sho Del illusion.”

“Sir?” Jerick asked with perplexment. “It was only an illusion; it wasn’t really there.”

“Ah,” Tzern replied, “but even knowing that, most men cannot force themselves to do such a thing.”

“It has to do with the nature of Sho Del illusion, Young Master,” Frost explained, noting Jerick’s continued confusion. “The Sho Del do not send images themselves, they just project an imprint into your head—a general set of instructions. Your own mind translates those instructions, creating the things you see. Each person who sees a Sho Del illusion is really creating the image in their own mind, assembling it from the things they have seen before. That’s why the illusions seem so real. A person can know logically that he is seeing an illusion, but since his own mind is creating it, filling in every necessary detail, it can still feel completely tangible to him.”

“Men often die from Sho Del illusions,” Tzern added. “Most soldiers, jumping as you did, would have convinced themselves that instead of passing through the illusion, they had run into it. They would have fallen to the ground, as if knocked unconscious.”

“I don’t know how to respond, sir,” Jerick confessed. “I knew it was an illusion and that I couldn’t let it distract me.”

“A good enough answer,” Tzern decided. “All right, Jerick, one final question. I always let men choose how they will serve. You may return to your bridgemen as their leader, and no one will think less of you if you do. You may be trained as an officer, and perhaps some day command a division—or even camp—of your own. Or, you may try something else.”

“Something else, sir?” Jerick asked carefully.

Tzern nodded toward the door, and Jerick turned, looking through the open portal. Just beyond, in one of the roped practice squares, two men were fighting. They wore no uniforms, though one was wearing a green vest and the other a blue one. Instead of practice swords they were holding real weapons. A small crowd of men had gathered around the sparring area, watching quietly.

The match was almost a surreal experience. He couldn’t be certain, not quite, but it seemed as if their motions were a little too quick, a little too fluid, to be a real battle. It wasn’t the blunt, forceful fighting of battlefield soldiers, or even the sparring of a fencing match. It was like a thing rehearsed, with each motion placed in precision.

As Jerick watched, the blue warrior spun, leaping into the air and placing his foot against one of the guard ropes. Though the rope should never have been able to hold such weight, the man pushed off of it into a flip, twirling in the air over his opponent. The green-vested man, however, had begun spinning himself, sticking out his foot as he rotated in an attempt to trip the man who had yet to land. Blue dropped to the ground, then immediately hopped, barely clearing Green’s attack, while at the same time bringing his own sword down.

Metal rang against metal as Green, still spinning from his attempted trip, thrust his sword back, blocking his opponent’s weapon without even looking to know where it was. Still spinning, his foot having yet to complete its trip-rotation, Green thrust his second foot into the air and caught Blue on the side of the head, pulling him to the ground.

Green was on his feet first, his sword plunging at Blue, who was still on his back. Blue paused, watching the sword plunge at his heart. He seemed as if he were going to do nothing. Then the world stopped. Jerick felt drawn into the battle, as if everything about him—the building, the watching soldiers, the sky and the earth—were focused on this one event. The green-vested warrior hung in the air, his blade just inches from Blue’s chest. Blue lay on the ground, his arm pulled back as if in a punch. Nothing moved—nothing could move. Then Blue’s hand suddenly snapped forward with an audible crack, smashing into his opponent’s blade at an incredible speed. The second warrior’s steel blade shattered in two by the blow.

Blue was on his feet a second later, swinging his sword at the now-disarmed Green. For a moment it appeared as if he would behead his opponent. The weapon, however, stopped just before Green’s neck.

“They are called the Tzai,” Ki Tzern said from behind. “My elite soldiers. Your third option, young Jerick.”

“I worried that something might have happened to you, Frost,” Jerick confessed, standing in his new room. He wished he had something to pack in the chest at the foot of the bed. His few possessions—a writing quill, some paper, a few coins, and some clothing—had apparently been confiscated by Demetris, who had branded Jerick a rebel and an insubordinate. Tzern’s officers had barely managed to release the five men left behind from the detention cells.

“I arranged to have myself transferred to another camp as soon as I could,” Frost said, standing on the other side of Jerick’s new quarters. It was a modest chamber, but a large improvement over the cramped tent of Demetris’s camp. It felt good to once again have a room to himself.

Jerick smiled. “You always did see things more quickly than I, Frost,” Jerick said, looking at the empty chest, then shutting it with a shake of his head. “I’m surprised you didn’t head back to Melerand as soon as you realized how hopeless I was.”

Frost smiled slightly. “I realized that before we left, Young Master,” he said. “I checked in on you from time to time—even considered approaching you and suggesting we return home. Each time, however, I sensed that you were not ready, and so I left.”

Jerick sat down on the room’s small mattress, leaning back against the wall. He searched for the words to describe all he had seen and done over the last year, the death, the loss of friends, the nightmares, the pride of seeing his men fight. “Oh, Frost,” he said with a sigh, “I’m glad I came here but . . . what in the name of the Lords was I thinking?”

“You weren’t thinking much, as I recall, Young Master,” Frost said, seating himself on the floor. “You felt as if you had been rejected, that your life had collapsed.”

“It’s been so long.”

“Only a year, Young Master,” Frost noted. “I suspect the world has changed little in such time. You, however, are a completely different matter. Have you looked in a mirror lately?”

Jerick shook his head. “Mirrors are a luxury Demetris’s army did not have.”

“Here,” Frost said, standing and retreating to the room next to Jerick’s—the scholar’s own quarters. He returned a moment later with a medium-sized mirror.

Jerick was stunned by what he saw. When he looked into the mirror, his own face didn’t look back—his father’s did. Firm and experienced, the face before him wore a dark curly beard. The body that accompanied it wasn’t as wide or burly as his father’s, but it was much taller, and powerfully well-muscled in its own right. It also had a litheness that Rin had never possessed. Jerick raised a hand to his face, feeling the beard with hesitant fingers. He’d never actually seen his reflection while wearing it.

“By the Lords. . . .” Jerick whispered. Who had stolen away the boy he knew and left this man in his place?

“You realize, Young Master, that there is another option left to you, one beyond the three Lord Tzern offered.”

Jerick looked away from the mirror. “Returning to Melerand,” he inferred.

Frost nodded, placing the mirror beside the wall.

Jerick thought for a moment. Then he shook his head. “I don’t know,” he finally admitted. “I’m not certain I can do it. Not yet. I’ll have to think about it.”

“You still think you can win enough glory to earn the princess?” Frost asked.

Jerick shook his head. “It’s not Courteth. It’s just . . . I’m not ready yet. Not ready to face them.”

“And?” Frost asked, sensing there was more.

“And . . .” Jerick said, his eyes darting involuntarily toward the practice squares.

“Ah,” Frost said with understanding. “The Tzai.”

“What are they, Frost?” Jerick asked, somehow knowing that Frost would be able to answer. “How do those men do such amazing things?”

“Are you certain you want me to answer that, Young Master?” Frost replied pointedly. “My explanation may go against some of the things you have read.”

“I don’t care,” Jerick informed. “I stopped ignoring truth after my first few months as a bridgeman.”

“Well, then, Young Master,” Frost began. “Your answer lies within an understanding of the Three Realms.”

“That much, at least, is true?” Jerick asked.

“Oh, yes. There really are Three Realms of Existence, Spiritual, Cognitive, and Physical, though they are not what men think them to be. Your scholars tell you the Spiritual Realm is that of the gods, the Cognitive Realm that of the Sho Del, and the Physical Realm that of man. The truth is that most things exist in all three realms.

“Everything you see around you, animals, rocks, and plants, has a Physical nature. You know that, you can touch it with your Physical nature. However, all things also have a Cognitive side and a Spiritual side as well. The Spiritual is its soul, its ideal nature. The Cognitive is the thing that mediates between an object’s Physical side and its Spiritual side.”

“The mind,” Jerick surmised.

“You could call it the mind,” Frost admitted, “though that doesn’t necessarily always hold true. A rock, for instance, has a Cognitive nature—a weak one, but it has one nonetheless. The Cognitive is what determines an object’s placing in the world—in effect, it remembers where the object is in relation to the rest of the universe. When the Sho Del use their minds to speak with one another, they are speaking Cognitive to Cognitive. When they send illusions to your warriors, they are doing the same thing.”

“Then the Sho Del are creatures of the Cognitive,” Jerick noted.

“Not exactly,” Frost corrected, holding a finger into the air. “The Sho Del tend to have powerful Cognitive sides, true, but they exist primarily in the Physical realm, just like humans. Men can have powerful Cognitive sides as well, though humans vary wildly from person to person. Some have more Cognitive power than even the greatest of Sho Del, others have so little they are only slightly better than a rock.”

“I’ve met a few of those,” Jerick mumbled.

Frost smiled. “You, Young Master, appear to have a strong Cognitive side.”

“How can you tell?”

“Because [REDACTED] is Cognitive magic. When you look at the world [REDACTED], what you are really doing is looking through the eyes of your Cognitive self. Almost like you have slipped into the Cognitive Realm for a moment, and are peeking out at the Physical world.”

“And when I use [REDACTED] to . . . change things?” Jerick asked quietly.

Frost paused. “I wasn’t aware you had gotten that far,” he admitted. “The essence of [REDACTED] is changing things—using Cognitive energy to make alterations in the Physical world.”

“And what these Tzai warriors do?” Jerick asked. “Is it the same thing?”

“No,” Frost corrected. “The Tzai go the other way. They use their Cognitive energy to affect the Spiritual realm—though they do it quite innocently.”

“Innocently?” Jerick asked.

“General Tzern is a brilliant man,” Frost explained. “But, like most brilliant men, he doesn’t accept the idea of magic or mysticism. When his men meditate and practice, they are focusing their Cognitive power, but they simply see it as a training technique. When a Tzai shatters his opponent’s sword with his bare hand, what he is really doing is gathering his Cognitive energy and using it to break the sword’s Spiritual aspect. Any alterations made to an object’s Spiritual side have immediate, and often violent, repercussions in the Physical world.

“Tzern’s warriors don’t see that side, however. They think their hand shatters the steel, when it really has little to do with the process.”

Jerick nodded slowly. What Frost was saying was different from what he had been taught. It was like a clearer vision of what the Trexandian scholars were trying to piece together. He only paused briefly to wonder how Frost knew so much. He trusted the words—somehow he innately understood that Frost was speaking the truth. Topaz was right—the old scholar was something much more than one first assumed.

Frost rose, brushing off his simple gray robes. “You should sleep now, Young Master. If what Lord Tzern said is true, then your day has been a difficult one. We will speak again in the morning.”

That night, sleeping was more difficult a proposition than was to be expected. He tried to turn in early, but to no avail. Six months ago he would have given nearly anything for a few extra hours of sleep. Now he found himself completely unable to use the time given to him.

Instead, his mind raced. He thought about his time in the Eternal War, his men, and his suffering. He wondered if he could turn down an opportunity to run when he had the chance, knowing that another year here—even in Tzern’s camp—meant more death, more pain, and more blood. He wondered if Ryalla remembered him.

Just after sunset, a knock came at his door.

“Come,” he said.

The door opened slightly, and General Tzern appeared. Jerick quickly moved to stand and salute, but Tzern waved him to be still.

“I saw your candle burning,” he said with his staccato accent, “and thought I’d drop by.”

“I have much to think about,” Jerick admitted.

“I understand.” Then, Tzern paused, searching Jerick’s eyes in his ineffable way. “You see them, don’t you, young Jerick?” Tzern asked quietly.

“See what, sir?”

“The nightmares and the visions,” Tzern continued. “The deaths of men you knew, the horrors of battle. You see them when you sleep.”

“Every time I close my eyes, sir,” Jerick admitted.

“Then know this. The Sho Del’s illusions aren’t the only visions Tzai are trained to overcome.”

Jerick thought for a moment. “Thank you, sir,” he said quietly.

“Good night then, young Jerick.”

“Sir,” Jerick said as Tzern moved to close the door.

“Yes?”

“I’ve made my decision.”

Tzern’s eyes searched his own, then he nodded. He had seen the answer therein.

“Come to my office in the morning and we will begin your training.”

This marks the end of the Bridge Four sequence in Dragonsteel Prime.

October 20, 2017

How to apply for Brandon’s 2018 BYU Class

Brandon’s assistant Karen here. It’s that time again—time to send in your applications for Brandon’s Winter 2018 English 318R class. We’re going to do things a bit differently this year, so I’ll go over the changes before I go into the details of how to apply.

Because the number of submissions is becoming unwieldy, this year we’re only going to consider the first 65 applications. That means that you cannot wait until 11:59 p.m. on the due date before you hit send. If you are serious about taking this class, you’ll get the application in early.

In theory, applicants should have a novel or two, or at least the first few chapters of a novel, already sitting around. You ought to spend a couple hours proofreading and giving it a once-over edit. Then take about 30 minutes on the application and essay question and hit send. So there should be little need for anyone to take two months to get it ready.

You can submit applications from October 23 until December 20. You’ll need to send me the first chapter of your novel and the application form found here. Follow the directions on that form exactly including filenames and subject line. Remember that you need to be a BYU student—but you can also sign up as a Continuing Education student or Evening Classes student. If you just want to take this one class, register as a student here.

As usual, the English 318R class is limited to the 15 people chosen from among applicants. Everyone is also encouraged to sign up for Brandon’s English 321R section, which is the lecture-only portion of Brandon’s class. Students who have taken the 321R portion in previous years will get some priority for 318R in future years.

For bonus reading, some hints on how to get accepted can be found here, and you might find my wrap-up blog post from last year interesting as well.

Karen

Annotation The Way of Kings Chapter 3

I chose to use Shallan as my other main character in Part One, rather than Dalinar, because I felt her sequence better offset Kaladin’s. He was going to some very dark places, and her sequence is a little lighter.

She is the only ‘new’ main character in this book. Kaladin (under a different name) was in Way of Kings Prime, and Dalinar was there virtually unchanged from how he is now. The character in Shallan’s place, however, never panned out. That left me with work to do in order to replace Jasnah’s ward.

Shallan grew out of my desire to have an artist character to do the sketches in the book. Those were things I’d wanted to do forever, but hadn’t had the means to accomplish when writing the first version of the book. I now had the contacts and resources to do these drawings, like from the sketchbook of a natural historian such as Darwin.

One of the things that interests me about scientists in earlier eras is how broad their knowledge base was. You really could just be a “scientist” and that would mean that you had studied everything. Now, we need to specialize more, and our foundations seem to be less and less generalized. A physicist may not pay attention to sociology at all.

Classical scholars were different. You were expected to know languages, natural science, physical science, and theology all as if they were really one study. Shallan is my stab at writing someone like this.

Kharbranth

The City of Bells is a true city-state. They have no real authority beyond the city itself, and they trade for everything they need. There aren’t Kharbranthian farmers, for example. If commerce were to fail, the city would flat-out collapse.

They do have their own language, as hinted at in this chapter, but it’s very similar to Alethi and Veden. I consider the three languages to really be dialects of Alethi, and learning one is more about learning new pronunciations as it is about learning new words. (Though there are some differences in vocabulary.) I would put them even slightly closer than Spanish and Portuguese in our world.

The city origins are a little less proud than they’d tell you. Kharbranth was a pirate town, a harbor for the less savory during the early days of navigation on Roshar. As the decades passed, however, it grew into a true city. To this day, however, its leaders acknowledge that they’re not a world power—and might never be. They use games of politics, trade, and information to play Jah Keved, Alethkar, and Thaylenah against one another.

October 18, 2017

Edgedancer is out!

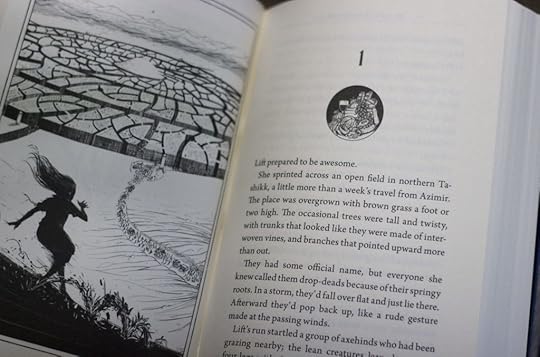

Edgedancer, a novella that was originally published last year as part of Arcanum Unbounded, was just released in eBook and (gorgeous) small hardcover yesterday.

For those of you who don’t know, the events that take place in Edgedancer occur between the closing of Words of Radiance and the forthcoming Oathbringer and is often referred to as Stormlight 2.5. The new release of Edgdancer also includes Lift’s interlude from Words of Radiance as a prologue so you can read all of her story in one place.

Here is a brief introduction to Edgedancer for those of you who haven’t read it yet.

Three years ago, Lift asked a goddess to stop her from growing older—a wish she believed was granted. Now, in Edgedancer, the barely teenage nascent Knight Radiant finds that time stands still for no one. Although the young Azish emperor granted her safe haven from an executioner she knows only as Darkness, court life is suffocating the free-spirited Lift, who can’t help heading to Yeddaw when she hears the relentless Darkness is there hunting people like her with budding powers. The downtrodden in Yeddaw have no champion, and Lift knows she must seize this awesome responsibility.

If you want to read the first few chapters of Edgedancer, Tor.com released the first 3 chapters as a preview last year.

Enjoy!

Dragonsteel Prime Chapter 35: Bridge Four 6

This chapter comes from the 2000 draft of a book called Dragonsteel. Some of the settings, situations, and characters were repurposed into The Way of Kings (2010).

“Look how they stand, men,” Jerick encouraged, gesturing to the plateau in front of them. The human warriors had arranged themselves in a sturdy line, each man prepared to guard the sides of the men around him.

“The important thing is not to break,” Jerick explained as the Sho Del made their attack. “If the line breaks, then the enemy can surround you and attack you from behind.”

The bridgemen nodded to themselves, watching the warriors fight. During the last few months, training during runs had been a success for more than one reason. Not only did it give the men something to do while they waited, but they were also able to see first-hand how their ranks were supposed to be formed. Though Jerick had a little knowledge of swordplay, he knew next to nothing about actual warfare. He learned, as the other men learned, by watching.

“See how each man’s shield partially protects his neighbor’s body,” Gathban noted.

“I doubt there’s a shield large enough to protect you, Rock,” Vessin said, slapping the Kaz’ch on the back.

Jerick chuckled, turning away from the battle. “All right, let’s form our ranks and practice. Remember your postures.”

The bridgemen did as he commanded, falling into two ranks of nine men each, and proceeded to stage a mock battle. Jerick and Gathban stood aside giving suggestions when they could.

Jerick had requested, and been refused, enough wood to make practice swords. The officers suffered Bridge Four’s training, probably because they couldn’t think of any reason to forbid it. Jerick could feel their resentment, however. Trained bridgemen challenged their elitism, breaking down the barriers between what made a man a noble and what made a man a peasant.

The more he thought about it, the more he wondered just why the officers—especially General Demetris—were so wasteful with bridgeman lives. Shields were a simple enough thing to produce, not really requiring that much wood or expenditure. However, such things were called too good for bridgemen. The more he thought about it, the more Jerick realized the entire situation—the bridgeman casualties—were less an issue of money, and more an issue of class. The regular warriors, mostly noblemen, often lost their lives while fighting for Dragonsteel. It would be wrong in their eyes for the peasants to escape unharmed when nobles died. So, the bridgemen were forbidden shields.

There was more to it than that, Jerick was certain. If the statistics he heard were true, then General Demetris was able to put more men on a plateau more quickly than any other general. Most of that success came because of the way he pushed his bridge crews. Giving them shields would just add another element of complexity to his resource management and burden of training. In the end, the simple question was: why protect the bridgemen when there are always plenty more to replace them? Demetris’s willingness to sacrifice men was always compensated by the Fallin emperor sending him more replacements.

Still, Jerick thought poorly of Demetris because of his attitude. Rin’s cardinal teaching had been that of not wasting life, and Jerick could not respect a man who so blatantly wasted his men. Jerick did, however, keep such rebellious thoughts to himself. General Demetris was the bridgemen’s ultimate superior—it would hurt their morale, and sense of purpose, if they knew of Jerick’s disapproval.

“Good,” Jerick noted as Kep jabbed his weapon between his opponents’ shields. The young boy was disadvantaged in many ways, but his size did make him a more difficult target to hit. He almost completely vanished when protected by the shield of his companion, and he moved incredibly quickly.

Kep smiled, an action that immediately earned him a rap on the head from his opponent’s ‘weapon’—a piece of bone approximately the same length of a short sword. Jerick had been right about the weapons—they weren’t as useless as they appeared. Though the short swords weren’t as majestic as longer swords, they worked very well in a tight formation. They much easier to thrust and swing than a longer blade.

“Stay focused, Kep,” Jerick warned, continuing to watch the battle. The men were getting good. Several months of training had made their reflexes quick, and their already strong muscles had provided a good basis for transforming them from servants to warriors. Now, when the members of Bridge Four walked through the camp, they wore their swords as if they knew how to use them. Each man also bore a small shield constructed of Sho Del bones.

Eventually, Jerick called for a break, and the men went to get drinks and rest. There would be no more practicing this day—it appeared as if the Dragonsteel battle was almost finished, and it wouldn’t do for his men to be exhausted from training when it came time to carry their bridge back to camp.

“Ho, Dente,” Jerick called as they approached the camp. “All is well?”

The tall Fallin smiled, nodding. He sat at the fire with four other men, stirring a pot of soup. The twenty with Jerick dropped their bridge in its place and began preparing for dinner.

“It was a quiet day, sir,” Dente explained, handing Jerick a bowl as he approached.

“That’s what it’s supposed to be,” Jerick replied with a smile.

Gaz had actually given him the extra bridgemen he requested—an action that had come as a bit of a shock to Jerick. The excess of five men had given Jerick an opportunity to instigate a plan he had been working on: giving the men a day off. Bridgemen worked all days of the week, and the constant drudgery took its toll. With twenty-five men in his crew instead of twenty, Jerick had been able to put them into a rotation, giving each man one day off in every five.

It was a small blessing, but it had made an enormous change in the bridgemen. Not only did their morale improve, but their bodies grew stronger as well. In addition, the ability to leave five men behind at the tent every day had completely eliminated theft. The camp’s soldiers left Bridge Four alone, for there was much easier prey to be found. As a result, the men had actually been able to save their earnings.

“Look, sir,” Dente requested, pointing back at the tent. The normally white side of the structure was covered with black letters.

“You did that?” Jerick asked, impressed.

“I practiced all day,” Dente explained.

“It’s good,” Jerick said appreciatively. Lacking anything else to write on, he had told the men to use the sides of the tent. The charcoal washed away freely enough. “We’ll have you reading Realmatic Theory by the end of the month.”

“Rel . . . what?” Dente asked, blushing beneath the praise. Then, pausing, he continued in a quieter voice. “Thank you, sir,” he said. “You don’t know what this all has meant to me.”

Jerick placed a hand on the man’s shoulder. Dente’s body was tougher now, lean where it once had been tall and somewhat scrawny. His long, rectangular face bore hope in it—something he had never expected to see from Dente. “I understand,” Jerick said simply.

“I’ve been a wanderer since my family died in that plague,” Dente continued softly. He rarely spoke of his past. “It’s good to have a purpose again.”

With that, the tall, willowy man turned to walk over to the side of the tent, reading the words penned by his own hand with a look of amazement in his eyes.

Jerick smiled to himself, tasting the soup. It was, of course, horrible—Dente couldn’t cook to save his life. Jerick ate it anyway, as did the other men—though he did notice Gathban discreetly adding a few spices to the mix.

Jerick watched them, standing a little off to the side. He felt like Dente, in a way. He was amazed at what Bridge Four had become, unable to believe the transformation. The men were singing a rousing song Vessin had taught them. They were happy, and they were alive. Somehow, as he watched them, he knew he couldn’t take much credit for their success. Just as the words Dente wrote on the tent had first been crafted by creative thinkers long ago, the souls of these men had been given life by a power far beyond Jerick’s own understanding. He had only given them a little bit of a push.

The song was about a boy named Pluke who, through encountering several mishaps and adventures, ended up the king of a nonexistent country. It was a silly song, involving several misadventures in places like brothels, but the theme was encouraging. Pluke won in the end, proving himself not to be the fool everyone had thought him to be. As the second verse began, Vessin called out with a loud voice, changing the name from Pluke to Hook. The men laughed, continuing the verses with this new alteration, and Jerick couldn’t help but chuckle to himself.

“In all my days, I’ve never seen such love for a leader,” a voice noted.

Jerick turned slightly as Gathban moved in the twilight darkness to stand next to him.

“I still don’t really understand why, Gathban,” Jerick said softly under the sound of the music. “I’m amazed every day. How did it happen?”

“I don’t know, sir,” Gathban admitted. “For me, it started on that day you took Dente’s place at the front of the bridge. In my six months in the war, I’d had leaders yell at me, cajole me, and even beat me. However, never once had I ever seen one actually try to lead me. After that . . . well, let’s just say my loyalty was certain the day you forced us to march back to the Plains in the middle of the night to search for Uthkar.”

“We found him dead,” Jerick said with a twinge of sorrow. Uthkar was the last soldier he had lost.

“Yes, but you didn’t know we would,” Gathban continued. “I saw him fall myself, but even I couldn’t be certain he was dead, considering how fast we retreated. That night, as we searched the Plateaus for that one man, despite what old Gaz had told us to do, I knew that you would do the same for any of us. The same for me. You knew we had to retreat when we did, lest the warriors be unable to cross the chasms and escape. But, you didn’t for one moment give up on poor Uthkar. Sir, I’d follow a leader like that anywhere.”

Jerick nodded slowly. “Thank you, Gathban,” he said quietly.

“No problem, sir.”

The song ended with a round of cheers to Jerick’s health and a toast—something which consisted of slapping their bowls of soup together as if they were mugs of saprye. Jerick nodded appreciatively, and the topic changed, turning to stories from the men’s homelands.

The talk had a strange effect on Jerick. He thought of Melerand with increasing frequency lately. Perhaps it was the camaraderie of the men, perhaps it was because of the time of year—his birthdate was quickly approaching. He had been at the Eternal War nearly a year now. He wondered about the King, Courteth, and even Yoharn. He missed them—they had become his second family. He felt guilty at his treatment of Topaz and the others—they hadn’t deserved his anger. He had searched the camp for Frost, but the man had disappeared, and Jerick was frightened for the old scholar’s welfare.

Most of all, however, he found himself wondering how Ryalla was doing. It was odd to him that he should worry about her—if anything, he should be thinking about Courteth. Ostensibly, all of his effort in the war was an attempt at winning the princess’ hand. The more time he spent here, however, the more he realized he had never really known Courteth. Her personality had been a thing of vapors to him—unimportant next to her beauty. Memories of her face faded, and he was left trying to remember any truly enjoyable times he had spent with her. To his surprise, there were none.

Ryalla, however, he could remember well. True, most of the recollections involved her implying he was a fool for one reason or another, but at least they were there. Jerick remembered with fondness the first time she had chastised him—the sentiment had been building for some time, and it had been no surprise to him when she released it. Ryalla, however, had been completely shocked that she would let such thoughts pass her lips. He wondered how she was faring up in Melerand, if Topaz often came to visit, and if they often spoke of how stupid their once friend had been for running off to die on the Shattered Plains.

Jerick continued his reminiscences for a short time, but then, almost unconsciously, his eyes noticed something. Kep was looking off into the darkness, a curious look on his face. Jerick followed the boy’s gaze, picking out a group of dark forms in the twilight. At first, his hand went to his sword, assuming the silhouettes belonged to soldiers come to sport with the bridgemen. Then, however, he realized the postures were much too stooped-over to be those of warriors. They were bridgemen.

Jerick met Kep’s eyes, then looked out into the darkness. The forms stayed a good distance away, listening to the singing. Jerick felt as if he could sense their longing, their jealousy, despite his inability to see their faces.

The music fell silent as the men noticed Jerick staring off into the night. They looked from him to the dark forms, questions on their faces. What should we do? they asked.

“Come closer,” Jerick suddenly called out.

The forms jumped, and looked as if they were going to scurry away.

“Leave if you want,” Jerick said. “But if you do that, we’ll be forced to eat all this soup ourselves.”

Slowly, uncertainly, the forms approached the firelight, not quite entering the circle. They stood for a moment and then, as if in concordance, Jerick’s men burst out into another joyful song, waving for their associates to join them in the light. Kep began gathering bowls and filling them with the remains of the soup, then handing them to the newcomers.