Brandon Sanderson's Blog, page 30

September 25, 2017

Way of Kings Prime Chapter 17: Merin 4

Note: This chapter contains minor spoilers for Words of Radiance.

Merin stood perched on the side of the stone wall, looking down. Kholinar’s walls were lofty and thick. Their sides smoothed by the drippings of winter storms, the wall’s blocks seemed to have melded together—almost as if the structure were formed of a single massive stone. The rock was dark, the color of crom buildup and winter lichens—similar to the buildings of Merin’s home village. Unlike many of Kholinar’s buildings, the walls could not be scrubbed clean or whitewashed. However, the unrefined look felt right—it made the walls seem more like a natural force than a man-made barrier.

Merin took a breath, then jumped off the side.

He had chosen a lower section of the wall—one of the shorter side bastions that ran parallel to the main structure. Even still, it was a daunting distance to the ground, thirty or more feet. Merin plummeted like a boulder. He tried to keep his eyes open as he fell, watching the ground approach. His feet slammed against it, the weight of his Shardplate throwing up chips of broken stone. He stumbled slightly, falling back against the wall and steadying himself.

He took a couple of deep breaths. Even after several tenset repetitions, jumping off the wall still unnerved him. Experience had proven that the fall would not hurt—though the impact shook a little, it was manageable. Still, there was something unsettling about falling from such a height.

Merin sighed, heaving himself away from the wall’s support to begin jogging back up the wall’s steps. Only sixty more to go. . . .

When he reached the top again, he was surprised to see Aredor waiting for him. Dalenar’s heir wore his customary well-tailored outfit, and stood leisurely with his back resting against the battlement. “My older brother once visited Shinavar,” he noted. “He said that there were animals there that could fly—strange, colorful creatures, some as large as a pig. I do not think, however, that they gained the ability through sheer force of repetition.”

Merin snorted, walking to his jump point, looking over the edge. A cool breeze was blowing, though the day was hot. Summer had almost reached the Searing, the forty-day stretch at its center when rain was scarce. The Searing was broken by only a single highstorm at its center—the Almighty’s Bellow, the most furious storm of the year.

Merin turned back to Aredor, removing his helmet and wiping his brow. “Vasher told me to jump off the wall a hundred times,” he explained.

Aredor raised an amused eyebrow. “Ordering you to eat in your armor for a week wasn’t enough for him, eh?”

“Apparently not,” Merin replied, shivering slightly at the memory of wearing his Shardplate to evening meals at Dalenar’s palace. Visiting lords had given him some very odd looks, but had received no end of mirth from the experience once Aredor filled them in.

“A hundred times, eh?” Aredor said. “What number are you on?”

“Forty-one,” Merin said.

Aredor grimaced. “You’ve been at it for several hours already!”

“It takes time to get up those steps,” Merin said.

Aredor just shook his head. Merin could see the amusement in his eyes, however.

“I know,” Merin grumbled. “I should have chosen one of the masters you picked for me.”

“Oh, I would never gloat over a friend’s misfortune,” Aredor said.

“I’m sure.”

“I’m certain Brother Vasher knows what he’s doing,” Aredor said. “Why, if you keep at it, and he might actually let you fight with a sword.”

Merin snorted, and threw himself off the top of the wall again. The uncoordinated jump, however, flung him off-balance, and he dropped on his side, crashing to the ground in an unceremonious clang.

With the hard landing, it happened again—just like the first time he had put on the armor, and several times after. The air around Merin changed, becoming viscous to his sight, patterns forming and flowing. The air was still transparent, yet keenly discernible to him—like the waves of heat rising above flames.

Merin sat stunned for a moment. The Shardplate had cushioned his fall, leaving him a little dazed—but that was not why he remained motionless. He still had no explanation for why the armor changed his sight—Aredor seemed befuddled, and Renarin said he’d rarely worn Shardplate. However, every time it happened, it lasted briefly. Any motion disturbed the experience, ending the surreal moment.

He did not want it to end. There was something . . . transfixing about the motions in the air. The patterns were not random—they moved with the air. In fact, it was almost as if he could see the wind itself, flowing around him, pushed by people who passed, falling in currents beside the wall’s shadow, only to rise when it reached sunlight again. The air seemed to whisper to him, drawing him to it, embracing him. . . .

Almost reflexively, he reached upward with a gauntleted hand. The experience ended as suddenly as it had come, plunging him back into normality. He lay dazed on the stones below the wall. Above, he could barely make out Aredor’s concerned face looking down at him.

Merin sighed, heaving himself to his feet to show that he was unharmed. Several minutes later, he puffed his way to the top of the wall again. The armor might increase his strength, but it was still difficult to make the climb over and over again.

“That was quite a jump,” Aredor noted.

“Are you here for a reason?” Merin asked. “Or did you just come to mock me?”

“Oh, mocking, mostly,” Aredor said with a yawn. “You know, you look like you could use a break. Why don’t you leave the rest of your . . . training for tomorrow?”

Merin glanced over the side of the wall. He had a dueling session with Vasher in another hour or so. It probably wouldn’t be a good idea to arrive fatigued from the jumping—the monk’s training was hard enough as it was.

“All right,” Merin said. “Let’s go get something to eat.”

“They said they were too busy with the harvest,” Merin said as he, Aredor, and Renarin made their way toward Shieldhome for evening sparring. “Or at least that’s what their letter said. The scribe says she copied down their words exactly, though.”

Aredor frowned. “Why wouldn’t your parents want to come to Kholinar? With a Shardbearer’s stipend you could surely give them a better life here.”

Merin shook his head. “It’s . . . difficult to explain.” His parents’ words, while disappointing, had not been surprising. “My parents are . . . happy as farmers, Aredor. Stonemount is a tiny village. Its people have no concept of the difference between tributing lords, ranking lords, landed nobility, and unlanded nobility. They’ve heard of Shardbearers, but none of them really know what that means. To them, what I’ve become is . . . something strange, something that shouldn’t affect one of their children. They do know that they have to get the harvest in, however, before the Searing arrives.”

“Still seems strange,” Aredor said. “You’re their son. Don’t they want to see you?”

Merin had visited once. Once their training as spearmen was completed, they had been allowed two months to visit their families before going off to Prallah. Even then, Merin’s visit had been awkward. None of his brothers had traveled further than the next two villages over. They had been fascinated by the stories he told, but reserved toward him. He had been . . . foreign. Merin remembered the awed hesitance he had seen in the eyes of his three friends that morning when he awoke to find himself a Shardbearer. He had no desire to see the same in the eyes of his parents.

“I’ll visit them once summer is over,” Merin said. “There’s no hurry—I’ve been away for three years now.”

They entered the monastery, where Aredor and Renarin split to walk toward the noblemen’s side of the courtyard. Merin was still a little surprised that Renarin came to the monastery—he would have thought the duels would be too strong a reminder of the lost Shardblade. Renarin, however, didn’t seem to mind—he and his brother spent many of their evening spars practicing with each other, using regular swords.

Something Merin still hadn’t been allowed to do. He sighed, setting his Shardblade against the far wall where he could keep an eye on it, then removing his slippers. He wore training clothing—a sencoat and loose trousers, much like the outfits the monks wore, though his was noticeably finer in make.

Vasher stood with his monk companions, drinking from a water barrel. Several of the monks nodded to Merin as he joined them. During his time training with Vasher, Merin had begun to understand a little bit of the politics of the monastery. At first it seemed like the only stratification in the courtyard lay in the division between lords and citizens. However, there was a more subtle distinction—one among the monks themselves.

While most of the monks ate together, shared the responsibilities of cleaning, and interacted with each other civilly, they always trained with the same group of men. The groups did not intermix on the sparring yard; they maintained strictly stratified cliques.

Vasher’s group seemed to be near the bottom. All its men were about the same grizzled age. They were different from the calm-minded weapons masters that trained in other parts of the courtyard. Vasher’s companions spoke less, and seemed to hide more within their troubled eyes. Most of them bore scars or other hints of battle. They were Oathgiven monks—men who had joined the monastery of their own will, after becoming adults. Merin wondered what it was these men wanted to escape, and whether the monastery provided the shelter they sought.

“How did the jumping go?” Vasher asked, lowering his ladle and wiping his mouth with a towel, then picking up his practice sword.

“I got about halfway done,” Merin said.

Vasher nodded, waving for Merin to follow him toward an open patch of sand. “Show me your stance,” he said once they arrived.

Merin fell into the dueling stance as he had been trained, hands held forward as if gripping a sword’s hilt. Vasher walked around him, eyeing the stance with a critical eye. Eventually, he nodded. “Good,” he said, tossing Merin the practice sword.

Merin smiled broadly, catching the wooden weapon. Finally! During the weeks of training, he had begun to desire the simple wooden blade with nearly the same zeal some men chased Shardblades. However, instead of power or title, the acceptance of this blade brought something else: validation.

Vasher walked over to the pile, picking through the practice weapons, acting as if nothing important had transpired. “Back into your stance!” he snapped, shooting a glance at Merin.

Merin did as ordered, falling into the stance, feeling the weight of the wooden sword in his hands. Regardless of its material, it was a fine weapon, well weighted and sturdy, bearing the nicks and bruises of countless matches. It felt good.

Vasher approached—bearing, Merin noticed with interest, a long, hook-ended polearm instead of a sword. Rather than falling into a stance when he arrived, Vasher simply reached out with the weapon, hooked the back of Merin’s leg, and flipped him off his feet. Merin toppled to the sand with a surprised grunt.

“Up!” Vasher said. “Quickly. Into the stance!”

Merin scrambled up, sand trickling from his sencoat as reassumed the stance.

“Not quickly enough,” Vasher said. “Again.” He hooked Merin’s leg with a quick gesture, throwing him to the sand again.

Merin did as commanded, this time making better time, jumping up and raising his sword as quickly as he could manage.

“Far too slow,” Vasher informed. “I want you to fall down and get up a hundred times.”

Merin groaned, lowering the practice sword. “I thought that since I had a sword now, you’d actually let me spar,” he complained.

Vasher snorted. “I just didn’t want you to get too accustomed to the stance with the wrong weight in your hands,” he said. “Now go.”

Merin sighed, falling to the ground, then scrambling back up. Vasher stood back, nonchalantly leaning against the polearm and watching as Merin worked. Sweat-stained sand was plastered to Merin’s forehead by the time he finished. However, he could already see improvement. Now, instead of rising and then assuming the stance, he could nearly step right into it from the moment he began to rise.

As he finished his hundredth rise, Vasher suddenly attacked, jumping forward with his hooked weapon. He swung the polearm like a staff, coming at Merin with both ends swinging in a flurry of attacks.

Merin yelped, bringing up the practice sword to block what blows he could. Vasher’s fury pushed him back across the sand, forcing him to retreat.

“Maintain the stance!” Vasher snapped between blows. “It will think for you. All of your strikes flow from the stance, all of your motions are fluid within it. In the stance, you are nolh, free as air, flowing into the next attack. If you break the stance, you become taln, and stone cannot change shape. Even a rock can be broken with enough force or persistence. The wind, however, can never be defeated.”

Merin tried to do as commanded, tried to keep his feet positioned as he had been taught, tried to step in the motions he had repeated hundreds of times. Even with the confusion of Vasher’s attacks, however, he could immediately see the truth of the monk’s words. When he didn’t misstep, when he managed to keep his sword placed in one of the five defensive positions, his body seemed to move without thought. The parries and retreats he had been taught came naturally, and Vasher’s blinding strikes were somehow blocked. However, when Merin misstepped, stumbled, or lost his focus for just a moment, a tenset blows seemed to strike his skin.

Vasher stopped eventually and Merin tumbled backward, stumbling and dropping to the sand, the practice sword falling from nearly numb fingers. He sat in the sand for a moment, gasping for breath.

Vasher planted the staff’s end in the sand and extended a hand, pulling Merin to his feet. “Go get something to drink,” he said.

Merin nodded thankfully, jogging over to the water barrel and grabbing a ladle. He drank thankfully, but sparingly. He probably didn’t need to be so frugal with water—not here in Kholinar, with its river and its lushness. However, his instincts still told him it was summer—back in Stonemount, water would be scarce until the fall highstorms began to pick up.

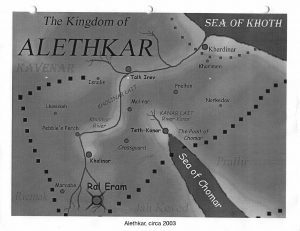

As he drank, Merin glanced across the courtyard, toward the sparring noblemen. Aredor and Renarin were there, as was Meridas and several of the other men Merin knew from the court. Apparently, many noblemen from Ral Eram came to Kholinar to train with Shieldhome’s respected master monks.

“I can’t help wondering if I should join those noblemen, Vasher,” Merin noted as his teacher approached. “When I was a spearman, the captains always emphasized how important it was to know the men you were fighting with, so you could trust them. How can I be expected to defend Alethkar in war if I don’t have the camaraderie of the other lords?”

Vasher shook his head. “When you were a spearman, your life depended on your neighbor’s ability to protect your flank. You’re a Shardbearer now; you can depend on no one. Even on a battlefield of a hundred thousand men, you will fight alone.”

“Yes, but shouldn’t I at least spend a little time sparring with them?” Merin asked. “Seems like it would help me learn how to duel.”

“I’m not teaching you how to duel,” Vasher said.

“What?” Merin asked, turning with surprise.

“I’m teaching you how to fight,” Vasher said.

“And the difference is?”

“One is contained in the other,” the aging monk said, turning to walk back across the sand. “Go and get your arrow.”

Merin sighed, putting away the ladle and walking over to the weapon pile to do as commanded. When he joined Vasher, the monk had retrieved a dark-colored sheath from the wall inside one of the rooms along the wall. The monk slid a bright steel sword from the sheath, its sheen reflecting the setting sun.

Vasher fell into his stance. “You wanted to spar?” he said. “Very well.”

Merin stood hesitantly, looking down at his arrow, then back up at Vasher’s sword. Its edge did not look dulled. “You have a very strange teaching style, old man,” Merin informed.

Vasher snorted. “Come on. Find the stance.”

Merin sighed, doing as instructed, holding out the long arrow as if it were a sword. He had pulled off the fletchings long ago, and held it in one hand as instructed by Vasher, but ready to use the second hand for power if necessary.

“This is the difference between dueling and fighting,” Vasher explained, stepping forward to strike. Merin jumped backward reflexively, resisting the urge to use his arrow to parry.

“Your noble friends,” Vasher continued, “they can only fight one way, with one weapon. If they lose their Shardblades on the battlefield, they become useless. Disarm them, and you’ve won. A real warrior, however, depends on himself, not on his weapon.” He struck again; Merin dodged backward, beginning to sweat. The sword stroke had passed far too close—did Vasher realize how dangerous his ‘training’ was becoming?

“You will study with the sword,” Vasher said. “And you will use a Shardblade. It will become part of you, like a limb of your own flesh. Sometimes, however, limbs must be lost to save the life. If you get too accustomed to the Blade’s lightness and power, it will become a crutch.” He swung again; Merin dodged.

“Come on,” Vasher chastised. “Fight me.”

“If I try to parry, you’ll just cut my weapon in half,” Merin complained.

“Then find another way,” Vasher challenged.

Merin continued to dodge, gritting his teeth. Each swipe was more frustrating, and Vasher’s comments began to sound like taunts. How did the man expect him to fight? This wasn’t a spar—it was a ridiculous farce.

Finally, Merin could stand it no longer. Vasher swung, and Merin struck, desperately lunging forward, driving the point of his arrow toward the man’s chest. The monk easily flipped his sword around, shearing the front off the arrow. Then he kicked, sweeping Merin’s feet out from under him and throwing him to the sand yet again. When his vision cleared, Vasher stood above him, sword placed against Merin’s neck.

“I want you to remember this,” Vasher said. “This is how every Shardless opponent will feel when he must face you. After a time, you will begin to think you’re invincible. But remember this feeling—the feeling that drove you to attack an expert swordsman with nothing but an arrow. That frustration, that hopelessness, drives men to recklessness and heroism. Perhaps, if the man you killed had remembered that, you would be dead and Alethkar would be part of Pralir, rather than the other way around.”

Vasher extended a hand, helping Merin to his feet. He nodded toward Aredor and the other noblemen. “They like to pretend that their duels are fair—they contrive ways to make them balanced. But no fight is ever balanced, Merin. One man is always better trained or better equipped. Some days, you will have to defend your life with a sick stomach, or with a dire thirst, or even after some woman has spurned you. It will never be fair. Honor and Protocol are fine ideals, but at the end of the fight, the one who is still alive usually gets to decide who was the more honorable. When you fight, you need to use every advantage you have. Understand?”

Merin nodded, reaching down to pick the arrowhead up off the ground so that no one would step on it.

“Good,” Vasher said. “Now, go jump off the wall some more.”

September 22, 2017

Annotation The Way of Kings Prelude

In classic Sanderson fashion, the beginning of this book was the part to see the biggest edits. I usually start a novel, write from beginning to end, then go back and play heavily with my beginning to better match the tone of the book.

Here, one of my big decisions was to choose between two prologues I had written out. One was with the Heralds, and set the stage for a much larger story—I liked the epic feel it gave, and the melancholy tone it set. The other was Szeth’s attack on Kholinar. This was a great action sequence that set up some of the plots for the novel in a very good way, but had a steep learning curve.

I was very tempted to use both, which was what I eventually did. This wasn’t an easy decision, however, as this book was already going to start with a very steep learning curve. Prelude→prologue→Cenn→Kaladin→Shallan would mean five thick chapters at the start of the book without any repeating settings or viewpoint characters.

This can sink a novel quickly. As it stands, this is the most difficult thing about The Way of Kings as a novel. Many readers will feel at sea for a great deal of Part One because of the challenging worldbuilding, the narrative structure, and the fact that Kaladin’s life just plain sucks.

It seems that my instincts were right. People who don’t like the book often are losing interest in the middle of Part One. When I decided to use the prelude and the prologue together, I figured I was all in on the plan of a thick epic fantasy with a challenging learning curve. That decision doesn’t seem to have destroyed my writing career yet.

September 20, 2017

Way of Kings Prime Chapter 12: Merin 3

Note: This chapter contains minor spoilers for Words of Radiance.

Merin stood uncomfortably, trying not to blush in embarrassment as the tailor pulled out yet another seasilk cloth—this one red—and draped it over Merin’s shoulders. The thick-mustached man turned, eyebrows upraised questioningly.

Aredor tapped his cheek musingly. The room was well lit and crafted of typical Kholinar granite, with woven mats on the floor and decorative pillars along the walls. Aredor leaned against one of the room’s pillars, watching the tailor work.

“Well, ladies?” Aredor asked, turning to the six young women who sat, arrayed in bright-colored tallas and jewel-riddled hairbuns, to his side.

“Better,” one of the women said. Merin still struggled to remember all of their names—he thought her name was Irinah. A creature with dark hair and a plump face, she was the daughter of one of Lord Dalenar’s trusted Shardbearers.

“I agree,” said the one with light hair and a greenish dress. Rahnel, he thought. “But he doesn’t look good in colors that bright. Try something darker, master tailor.”

The other women agreed, nodding and chatting among themselves. Merin flushed at the attention as the tailor removed the cloth and waved his aides to bring him some other choices. It seemed ridiculous to Merin that people could spend so much time worrying about clothing. Before the colors, Merin had spent the better part of an hour trying on different cuts of shirt and trousers behind the changing screen, then presenting each new combination for Aredor and the women to judge.

Yet Aredor and the ladies didn’t seem to find the experience boring. As a matter of fact, they appeared to be enjoying themselves immeasurably. Of course, they weren’t the ones standing on tired legs while the entire room gawked—if it hadn’t been for his military training, Merin was certain his legs would have given out long before.

“Hang in there, Merin,” Aredor said, reading Merin’s expression with a chuckle. “You’ll be glad for the effort—these ladies are the finest judges of apparel in the court. When they’re finished with you, your wardrobe will be the envy of the city.”

The women laughed demurely at the compliment. It seemed to Merin that they were paying more attention to Aredor than the clothing selections. That, however, was not a problem—better Aredor than Merin.

“It certainly is good to have you back in the court, Lord Aredor,” Irinah said as the tailor draped another cloth across Merin’s shoulders, letting it fall around his body like a cloak. Irinah seemed the leader of the women, though from what Merin understood, she was one of the lesser ranked of the four. That was another thing he couldn’t quite figure out, though—noble ranks.

“Oh?” Aredor said with a raised eyebrow. “I wasn’t certain the court would even notice my absence.”

“Lord Aredor!” one of the other ladies said with indignance. “Why, the court wasn’t the same without you!”

Aredor chuckled, nodding toward Merin. “Don’t get distracted, ladies.”

They turned their attention to Merin again, studying the new colors—a deep charcoal draped with grey.

“Far too dreary,” Rahnel pronounced. “Lord Merin is somber enough without covering him in greys.”

“Besides,” Irinah said, “black reminds of Awakeners. No court-conscious man should wear anything too similar to it.”

The tailor nodded, rifling through his cloths again as his assistants pulled off the black and grey. Somber? Merin thought.

“Have you heard the story of Lord Merin’s bravery on the battlefield, ladies?” Aredor asked. “You know he saved the king’s life?”

Merin flushed at the comment, but the women only grew more excited. “Oh, yes,” said one of the more quiet women—Merin had forgotten her name, though she had a thin frame and wide eyes. “We’ve heard of it.” She sighed wistfully.

Merin’s flush deepened. Of course she’d heard of it—everyone had. In fact, most of the people he met couldn’t stop talking about his heroic rise to nobility. To them, his exploit was as something out of the ballads. They didn’t know how hasty and uncoordinated it had been. Of course, most of them seemed more fond of moaning over its dramatic power than actually congratulating Merin on his success. It was as if there were two Merins—one the romanticized lord, the other the awkward peasant-made-nobleman.

“Did you really defeat a Shardbearer without even a dagger?” one of the girls asked.

“Not exactly,” Merin said with a sigh, his voice muffled as the tailor pulled a cloth over his head—this one had a hole in its center so it fell evenly around his body. “I just pulled him off his horse. Someone else actually killed him.”

“Lord Merin is too modest,” Aredor informed. “The Prallan Shardbearer had broken Protocol, and was about the strike the king down. Everyone else scattered, and we were sure His Majesty was doomed. Only one man was brave enough to come to his king’s rescue.”

The women turned properly amazed expressions toward Merin, mouths forming Os of wonder. The tailor stepped back, regarding Merin critically.

“No brown or tans, master tailor,” Irinah said, frowning. “Lord Merin has only recently become a Shardbearer. Brown is too mundane a color—there is no reason to give a reminder of what he once was, now is there?”

The tailor nodded, moving to remove the cloth. Merin sighed to himself. “Aredor,” he said as the tailor worked. “Isn’t there something more important I should be doing?”

“A man has to look good,” Aredor replied. “Half of being a lord is looking the part.”

“That’s the thing,” Merin said. “I’m still not sure what it means to be a lord. What is it I’m supposed to do? Surely there’s more to it than dressing well.”

Aredor chuckled. “You’re always so concerned about what you should be doing. People aren’t going to tell you what to do all the time anymore. Being a lord isn’t so much about what you’re supposed to do as it is about what you feel you need to do. Besides, having a Shardblade doesn’t mean you can’t relax once in a while.”

Standing and being draped with cloth didn’t seem much like ‘relaxing’ to Merin. However, he simply sighed and decided to bear it—Aredor probably knew what he was doing. The tailor finished again and stepped back.

“That’s perfect!” Lady Irinah proclaimed, a sentiment that the others agreed to after a moment of discussion.

Merin looked down. The chosen color was a dark maroon, crossed with a sash of deep navy. It was only one of four color combinations the women had decided they liked. All of them were darker colors—maroon, dark green, and several shades of blue.

“Yes,” Rahnel said with satisfaction. “Well done, master tailor.” The man bowed at the compliment, motioning for his assistants to gather up the cloths and repack them.

Merin looked questioningly toward Aredor, eyebrows raised hopefully. Aredor nodded, waving him down off the raised platform. Just then, the door opened and Renarin stepped in, a customarily dazed expression on his face. Immediately the room fell silent, as the women stopped their chatting.

Renarin stood for a moment, looking across the room. His hair was disheveled, as it often was, and he somehow managed to stand halfway in shadow despite the room’s brightness. The women sat in silence, shooting glances at each other. They tried to maintain their smiles, but even Merin could see that they were uncomfortable.

“I’m . . . sorry to interrupt,” Renarin said, turning to go.

“Nonsense, brother,” Aredor said, waving him forward. “We were finished here anyway, weren’t we, ladies?”

The women rose, smiling and offering belated welcomes to Renarin. They bid Aredor farewell, each getting promises from him that he would call upon them soon.

Renarin watched them go, then turned to Aredor as the door closed behind them. “It didn’t take them long to start fighting for your affection,” he noted.

“Ah, you’re too cynical, brother,” Aredor said, still watching the door, shaking his head wistfully. “We’ve been gone too long. There haven’t been any men here to give them attention. Poor things.”

“They could have come with us to Prallah,” Renarin replied. “The winds know, we could have used a few more scribes.”

Aredor chuckled. “That lot would never have survived the stormlands. This is their element—and now that we’re back, our dear Merin had better watch out.”

Merin frowned as he joined the two brothers, picking up his Shardblade as the tailor and his assistants left out the back door.

“What was that?” Merin asked. “Why do I have to watch out?”

“Unmarried Shardbearer?” Aredor asked. “Savior of the king? Newly adopted into house Kholin? You’re a prime catch, my friend. If you don’t watch yourself, one of those ladies’ mothers will have you wedded before you realize what happened.”

“And, knowing my brother,” Renarin added, “he’s doing everything he can to help them out. You realize half the reason he held this little tailoring session was to introduce you to the local eligible women.”

“A little socializing never hurt a man,” Aredor said. “You should try it sometime, Renarin.”

Merin fastened on Dalenar’s cloak, testing the new length—Aredor had ordered one of the tailor’s assistants to hem it, and they had returned it when they arrived. “I appreciate the help, Aredor,” Merin said. “But the truth is, I don’t know if I’ll be able to afford much clothing this month. I planned to send the stipend your father gave me to my parents in Stonemount.”

“Oh, don’t worry,” Aredor said with a wave of his hand. “If you need more, I’ll lend it to you. Now, are you ready for today’s other activity?”

Merin frowned. “There’s more?” he asked, stretching his tired limbs.

“You’re the one who’s always asking what his duties are,” Aredor reminded. “Well, it’s time to start them. If you’re going to compete in Elhokar’s dueling competition, you’ll need to learn how to use that Blade and Plate of yours.”

“Dueling competition?” Merin asked, feeling a twinge of excitement. “Me?”

“Of course,” Aredor explained. “The king ordered all Shardbearers to attend, and you’re a Shardbearer. Unless you want to be made a fool of, you’ll want to learn how to duel a bit before you get thrown into a ring.”

Merin smiled. Finally, something that made sense. The ballads made one thing clear: Shardbearers dueled. “When do we start?”

Aredor nodded. “To your room,” he said. “We’ll start with the Plate, then we’ll go find you a dueling instructor.”

“Father thinks it was a group known as the Rantah,” Renarin explained.

“Rantah?” Aredor asked as he unpacked Merin’s Shardplate, arranging the various pieces on the floor.

“It means ‘Distant Mountain,’” Renarin said. “When he founded Pralir, King Talhmeshas had to conquer a number of smaller nations—he had to hold both the Prenan Lait and the western coast of Prallah if he wanted to found a kingdom with any measure of stability. Rantah is an underground rebellion populated by the noble lines of those conquered kingdoms. They’ve been a stone in Pralir’s shoe for the last two decades, burning villages, attacking caravans, and destroying soldiered garrisons.”

“An underground rebel group?” Aredor asked skeptically. “That doesn’t sound like the kind of organization who could destroy an army of twenty thousand. If they could do something like that, why stay underground? In fact, if they had those kinds of numbers, I doubt they could have stayed underground.”

Renarin shrugged. “The old nobility of Pralir—the ones who have made peace with Elhokar, hoping that he’ll let them retain a margin of power—are convinced it was the Rantah. They say the group has been hiding in Distant Prall for a few years, gaining strength. If they attacked at the right time, as an ambush, it’s conceivable they could have destroyed the Traitor’s secret force. At least they had motive—if there was a group out there who hated Talhmeshas Pralir more than Elhokar, it was the Rantah.”

Aredor shook his head, not convinced as he regarded the Shardplate. Merin’s room was relatively small, but it was blessedly big compared to the simple floor mat and crowded troop tent he had used during his time in the military. There was a bed, a table, and a stool—and while the floor was empty of rugs or mats, Aredor said Merin could purchase either whenever he wished. Right now, the stones were covered with the array of metal Shardplate sections. There were over a tenset pieces, and all had leather straps, but strangely no buckles. Merin looked down, bewildered—he didn’t even know where to begin.

“Shardplate is kind of a misnomer,” Aredor began, selecting a piece of armor—the largest piece, a breastplate-shaped cuirass. “It doesn’t really bond to a person the way Shardblades do. It probably got the name because Shardbearers were the ones who tended to wear it.” He motioned for Merin to hold his arms out, then fitted the breastplate across Merin’s chest.

The leather straps constricted quickly, and Merin cried out in surprise. The piece of armor felt like something living, clamping onto his chest like the jaws of an animal. It halted a moment later, however.

Merin wiggled slightly, amazed at how freely he could breathe. The metal was heavy, but weighed far less than the metal breastplates he had occasionally trained with as a spearman. In fact, despite being a single sheet of metal, it felt less constrictive than even his layered wooden spearman’s armor.

“Shardplate fits to its owner,” Aredor explained, reaching for the shoulder guards. “However, it doesn’t bond to you—if you take it off, it will fit to the next person just as quickly as it did you.” Aredor placed the shoulder guards, and they too immediately locked into place, their straps clamping on and fitting to Merin’s body.

“You can put the armor on by yourself, but it’s a bit awkward,” Aredor explained, moving on to the left arm. “If you want to take it off, you can touch the clasp underneath each piece and it will unlock. The armor will stop pretty much any weapon, as long as it doesn’t manage to slide into a chink between two pieces. Shardblades are the exception—Plate will only stop a Shardblade on the first blow. If you get hit squarely in the same place twice, the plate will probably give way.”

“Then what?” Merin asked as Aredor affixed pieces of Plate to both arms. “Is my armor ruined?”

Aredor shook his head, picking up some pieces of armor that fit around the bottom of the chestplate, protecting his sides and waist. “It will repair itself, molding back into its original shape. That takes time, though, so you’ll want to avoid getting hit.”

Merin nodded as Aredor handed him the codpiece, then moved onto helping him attach the leg pieces and metal boots. When he was done, Merin was covered completely in steel except for head and hands. It was a strange feeling, like he had been dipped in a pool of molten metal.

Merin wobbled slightly. It was awkward—that was for certain. However, not because of the weight. Strangely, he felt no more burdened than when Aredor had affixed the first piece. Instead, it was just . . . different. There were tugs on his body in irregular places, and his balance felt slightly irregular.

He raised an arm, and it swung up with ease. Carefully he tested his motion, squatting down and standing up again. Then he tried a small jump. He cried out in surprise as he went higher than expected—almost as high as he would have gone if he weren’t wearing several tenset brickweights of metal. Aredor steadied him as he teetered maladroitly.

“It takes some getting used to,” Dalenar’s heir said with a chuckle. “The Shardplate was made by Awakeners, like your Blade. It compensates for itself, making you stronger and quicker. If you know how to balance the combination of awkwardness and enhancement, you can actually be more fluid in the Plate than you would be normally. You’ll definitely be stronger. The Plate also cushions you from blows—wearing this, you could probably take a catapult boulder in the chest and come out alive.”

Aredor bent over, picking up the last three pieces of armor. “These are the most important pieces of equipment,” he explained. “The gauntlets and the helmet. Most people who attack you will go for your head—it’s the most exposed part of the body. We don’t know why, but no suits of Shardplate were made with faceplates. Some people try affixing them with regular steel faceplates, but many prefer visibility instead. No Shardbearer following Protocol will swing for your face, though they may attack the side of your head. Spearmen and other citizens, however, will always go for the face—that’s practically the only place they can hurt you.”

Merin nodded, accepting the helmet and placing it on his head. Like the other pieces, it immediately sized to fit him, and rested more snugly than his spearman’s cap ever had.

“The gauntlets are designed to give you flexibility,” Aredor explained, holding out the left gauntlet for Merin to slide his hand into.

The gauntlet was crafted from what appeared to be a heavy leather glove fitted with intricate plates of steel running along the back. However, flexing his hand, he realized he could feel through the leather as if it were extraordinarily thin. “It’s amazing,” Merin whispered.

Aredor smiled, holing out the other gauntlet, and Merin slid his hand into it as well.

Immediately, the room pitched around him. Merin stumbled, disoriented, at the strange sensation. The air seemed . . . thick, somehow. Liquid. It rippled and shifted, like—

It stopped. Merin shook his head uncertainly, lifting a gauntleted hand. “Is that supposed to happen?” he asked.

“What?” Aredor asked with concern.

“I . . . I’m not sure,” Merin said. “The room suddenly felt different. I can’t explain it.”

Aredor looked toward Renarin. The younger brother shrugged. “It’s probably just the initial surge,” Aredor explained. “Every time I put the last piece of Plate on, I just feel a slight burst of strength as the Plate completes itself.”

“Maybe that was it. . . .” Merin said slowly.

“Well,” Aredor said, standing. “That’s your armor. Now that you know how to put it on, take it off. We’ve got to get to the monastery while there’s still some light left for training.”

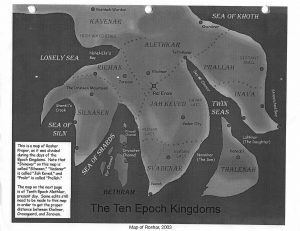

Kholinar was beautiful. Merin couldn’t remember a day when it had been the capital of Alethkar, but it had an Oathgate, which meant it dated back to the days of the Epoch Kingdoms.

Before his ascension to nobility, Merin had never visited a lait. He had known that there were valleys where rivers ran down the center. The idea of a constantly running river itself was amazing enough—back in Stonemount, water had only flowed right after a highstorm. Rain had to be collected carefully, so that there would be water to drink between storms.

Merin had imagined the river to be like the waterways back home—small and swift-running, flowing through cracks with the quick energy of a storm. He had never imagined such a broad, rushing mass of water. It passed by a short distance from Kholinar—far enough away that floods following highstorms wouldn’t be a problem. There was so much water that when he had first seen it the week before, Merin had stood stunned for at least ten heartbeats before Aredor was able to get his attention.

The Lait itself was a valley, one with relatively stiff sides. They were smooth, worn by countless highstorms, but the incline was steep enough for Merin to finally understand just why laits were so perfect for cities. In Prallah, his squad had been taught to avoid narrow canyons for fear of being in one when a highstorm caused a flash flood. The lait valley, however, was wide enough not to be dangerous, but still steep enough that it weakened storms greatly. Indeed, the highstorms that had come since Merin’s arrival in Kholinar had been almost laughably docile.

The result was fertility. Rockbuds lined the sides of the valley—so many of them, in fact, that he could barely see the rock underneath. All of them were in bloom, despite the fact that the last highstorm had been several days before. The landscape was green instead of stoneish tan—it had been unsettling at first, all of that color, but he was quickly growing to appreciate it. Aredor said that the rockbuds only withdrew into their shells during the very height of summer—when the air grew too dry for even the humid valley—or the dead of winter, when the rains fell so steadily that many plants had to withdraw lest the moisture rot them.

The roads of the city were kept free of rockbuds, and the ground was so smooth that Merin had begun copying Aredor, wearing only a pair of comfortable slippers. Back in his village, most buildings had been allowed to give in to the elements. Rockbuds were not removed, and continual buildup of cromstone from winter storms formed stalactites on overhangs, making the buildings look almost like natural formations of stone. In Kholinar, however, everything was sculpted with neat lines. Triangular shapes predominated, with peaked arches and doorways, and many buildings were constructed on grand scales, with massive columns and large open foyers—something only possible in a place where the highstorms lacked fury.

Aredor led Merin toward the edge of town, where they would find Shieldhome Monastery. As they traveled the smooth streets, Merin shook his head in wonder. Two years earlier, he had traveled to a monastery to learn to wield a spear. What would he have thought, had he known he would be returning several years later to take up dueling as a nobleman and a Shardbearer?

Such thoughts were banished, however, as Merin idly caught sight of a passing building. He froze immediately, staring with awe—and more than a little apprehension. The large black structure was crafted in a bulbous shape that seemed to defy regular architectural conventions. It almost looked like an enormous pyre—a massive burst of flame that had somehow been captured and transformed into rock.

Aredor and Renarin paused beside him. “It’s the Kholinar Kablan,” Aredor said. “Hall of the Awakeners. A little eerie, isn’t it?”

Merin nodded. He’d heard of Kablans before, of course, but they didn’t have one in Stonemount—or in any of the nearby villages. In the rare instance an Awakener was discovered in a rural area, they were always sent to a larger city, and the village was paid a percentage of the profits that came through the Awakenings the creature performed.

A group of servants were driving a line of carts toward the Kablan, each one bearing a large block of stone. A couple of figures stood at the base of the marble building—and they wore black. Merin shivered as one of the figures turned toward him. Merin couldn’t see what it looked like because of the distance, but he knew the stories. Awakeners weren’t quite human, not anymore. Their arts . . . changed them.

“I’ve always wondered what the inside looked like,” Renarin noted, looking at the Kablan.

Aredor shivered visibly. “I have absolutely no idea, and no desire to find out. In fact, if I never had to see an Awakener except on the day of charans, it would be fine with me.”

“They are the fuel of our economy,” Renarin said in his unassuming voice. “Without them gemstones would be useless, and we would be paupers, my brother.”

“Well, that’s fine,” Aredor said. “Let them fuel the economy—as long as they do it from within their building.”

Merin nodded. “I agree,” he mumbled. The figure was still looking at him. He had only seen an Awakener once, during his charan. It had been a young man, one who hadn’t been an Awakener very long—only the unlearned were wasted on the charan. That Awakener hadn’t looked any different from a regular person, but he would change. Apparently they all did, eventually.

Merin could still remember the glowing bit of quartz hovering above the Awakener’s hand. He could remember his fear as the quartz floated forward, still glowing, to touch Merin’s skin. It had shattered, sending a strange sensation through his body—a sudden vibration, a feeling like each of his bones had been scraped against rough stone at once. Supposedly, that one experience made Merin immune to Awakening for the rest of his life. There was no reason to fear the creatures, for they no longer had power over him. Even still, when the day of the charan came each year thereafter, he had found a way to be out in the fields when the Awakener arrived to perform the ritual on the children of age that year.

“Be thankful, Brother,” Renarin noted, “that the Almighty didn’t decide to make you an Awakener.”

Aredor snorted. “Come on, let’s get to the monastery while there’s still light.”

Merin nodded eagerly, joining Aredor as they walked away. Renarin lingered for a moment, then followed. Soon they had left the Kablan behind, and a structure with a familiar architecture rose up before them.

Aredor said that Shieldhome Monastery was one of Kholinar’s most famous landmarks. Founded during the Ninth Epoch, the monastery contained the most skilled masters of dueling in all of Alethkar. As they walked through the broad, glyph-covered gates, Merin immediately felt a familiarity. Two years earlier, when he had first joined the military, he had been taken to a Strikehome Monastery in Norkedav for initial training. While the city had been much less grand than Kholinar, the monasteries were nearly the same. The ground was covered with sand for training, and the monastery was made up of four walled courtyards with quarters for the monks lining the outer perimeter.

Aredor kicked off his slippers, motioning for Merin to do the same. “I need to go speak with the monks,” Aredor explained. “And have them gather their masters to see if any are willing to train you. Go over and watch the men spar, if you like. It will give you a feel for the training.”

Merin nodded as Aredor wandered off. There were several groups practicing in the courtyard, including one to his left that was composed of men in colorful clothing—obviously lords. Merin wandered their direction, curious.

Several pairs dueled with Shardblades—an action that Merin would have considered dangerous, had Aredor not explained that once a Shardblade was Bonded, it could be dulled for sparring. The majority of the men, however, dueled with regular swords. As Merin approached, he realized with a sinking feeling that he recognized several of these men.

“Well,” Meridas said, holding up a hand to stop his duel. “Greetings to you, peasant Shardbearer.”

Merin frowned, wishing he’d recognized the man earlier. What was he doing in Kholinar? Meridas was attendant to the king; he should have remained in Ral Eram.

“Come to learn how to duel, little citizen?” Meridas asked, sword held casually at his side as a few other noblemen gathered around him with interested expressions. “You’ll have to be careful. Wouldn’t want to get . . . hurt by accident. Then someone else would have to be given that pretty Blade of yours.”

Merin sighed, turning away from Meridas and the others. He felt their laughter on his neck as he walked away. Every time that he felt like he was growing to be accepted in Dalenar’s court, someone reminded him that he didn’t really belong. Aredor and Renarin could only do so much—they had their own lives, and their own duties. They couldn’t watch out for Merin forever—eventually he would have to find his own way.

You won’t be able to make everyone like you—but you might be able to make them respect you. Dalenar’s words from before returned to him. Merin looked down at his Blade. Perhaps dueling was the way to earn that respect.

He wandered across the courtyard, looking for other duels to watch. Most of the noblemen were near Meridas, so Merin instead found himself watching a group of older monks. Like many monks who followed the Order of Khonra, they wore long tan skirts and loose shirts instead of traditional robes. They fought with swords, though they weren’t necessarily noblemen—monks were considered to have neither class nor gender, and they could practice any art they wished, whether it be painting or dueling.

The monks were very good. They fought with wooden practice swords, and their motions were fluid. Rhythmic. Watching their smooth, controlled motions seemed to calm a bit of the chaos in Merin’s recent life.

After a few moments, one of the monks noticed him watching. The man paused, regarding Merin with the eyes of a warrior. “Shouldn’t you be practicing with the other lords, traveler?”

Merin shrugged. “I don’t really fit in with them, holy one.”

“Your clothing says that you should,” the monk said, nodding to Merin’s fine seasilk outfit.

Merin grimaced.

The monk raised an eyebrow questioningly. He was an older man, perhaps the same age as Merin’s father, and had a strong build beneath his monk’s clothing. He was almost completely bald, save for a bit of hair on the sides of his head, and even that was beginning to grey.

“It’s nothing, holy one,” Merin said. “I’m just a little bit tired of hearing about clothing.”

“Maybe this will take your mind off it,” the monk said, tossing him a practice sword. “And don’t call me ‘holy one.’”

Merin caught the sword, looking down at it blankly. Then he yelped in surprise, dropping his Shardblade and raising the practice sword awkwardly as the monk stepped forward in a dueling stance. Merin wasn’t certain how to respond—all of his training in the army had focused on working within his squad, using his shield to protect his companions and his spear to harry the opponent. He’d rarely been forced to fight solitarily.

The monk came in with a few testing swings, and Merin tried his best to mimic the man’s stance. He knew enough not to engage the first few blows—they were meant to throw Merin off balance and leave him open for a strike. He retreated across the cool sand, shuffling backward and trying not to fall for the monk’s feints. Even still, the man’s first serious strike took Merin completely by surprise. The blow took Merin on the shoulder—it was delivered lightly, but it stung anyway.

“Your instincts are good,” the monk said, returning to his stance. “But your swordsmanship is atrocious.”

“That’s kind of why I’m here,” Merin said, trying another stance. This time he managed to dodge the first blow, though the follow-through caught him on the thigh. He grunted in pain.

“Your Blade is unbonded,” the monk said. “And you resist moving to the sides, as if you expect there to be someone standing beside you. You were a spearman?”

“Yes,” Merin said.

The monk stepped back, lowering his blade and resting the tip in the sand. “You must have done something incredibly brave to earn yourself a Blade, little spearman.”

“Either that, or I was just lucky,” Merin replied.

The monk smiled, then nodded toward the center of the courtyard. “Your friend is looking for you.”

Merin turned to see Aredor waving for him. Merin nodded thankfully to the monk and returned the practice sword, then picked up his Shardblade and jogged across the sands toward Aredor. Standing with Dalenar’s son was a group of elderly, important-looking monks.

“Merin,” Aredor began, “these are the monastery masters. Each of them is an expert at several dueling forms, and they’ll be able to train you in the one that fits you best. Masters Bendahkha and Lhanan are currently accepting new students. You can train with either one of them, though you’ll need to pay the standard hundred-ishmark tribute to the monastery out of your monthly stipend.”

Merin regarded the two monks Aredor had indicated. Both looked very distinguished, almost uncomfortably so. They regarded Merin with the lofty expressions of men who had spent their entire lives practicing their art, and who had risen to the highest of their talents. They stood like kings in their monasteries—not condescending, but daunting nonetheless.

Merin glanced to the side, a sudden impression taking him. “Holy ones, I am honored by your offer, but I feel a little overwhelmed. Could you tell me, is the monk I just sparred with accepting students at the moment?”

The masters frowned. “You mean Vasher?” one of them asked. “Why do you wish to train with him?”

“I . . . I’m not certain,” Merin confessed.

One of the masters waved for a younger monk and sent him running off toward Vasher’s group. As he did so, Aredor pulled Merin aside with a concerned face.

“What are you doing?” Aredor asked quietly.

“Those masters make me uncomfortable, Aredor,” Merin said.

Aredor rolled his eyes. “You’re going to have to get over that, Merin. You’re a lord now.”

“I’m trying,” Merin replied. “But . . .”

“The man you sent for isn’t even a proper monk,” Aredor said. “He’s Oathgiven, not Birthgiven. He joined the monastery by choice, rather than being given by his parents before the age of his charan. He won’t be a dueling master—he probably just came here by happenstance.”

“Aredor,” Merin said frankly, “I came here by happenstance.”

Aredor just sighed as the young monk approached, the man Merin had spared with—Vasher—following behind. “What is this about, masters?” Vasher asked in a calm voice.

“This child wishes you to be his master,” the senior master said, waving toward Merin. “He wishes to know if you are taking any students.”

Vasher snorted. “You really don’t know what you’re doing, do you, little spearman?”

Merin just shrugged.

“Very well,” Vasher said. “If he is willing to do what I say, I’ll train him.”

Aredor groaned quietly, but the masters just nodded and began walking away. Vasher turned back toward the corner of the monastery, where the monks he had been sparring with still practiced. Uncertain what else to do, Merin tagged along behind. Once they reached the place he had dueled before, Merin set aside his Shardblade and reached for a practice sword.

Vasher reached out a foot and placed it on the sword just as Merin began to lift it. “No,” he said.

Merin rose uncertainly, watching as Vasher walked over to the weapons pile and selected an object. He returned with a large, thick-hafted horsekiller arrow and handed it to Merin.

“An arrow?” Merin asked slowly.

“A little spear,” Vasher said. “For a little spearman. I don’t want you thinking you are a duelist—you haven’t earned a practice sword yet.”

“You let me fight with one before, master,” Merin protested.

“That was before you were my student,” Vasher informed. “And don’t call me ‘master.’ My name is Vasher. From this moment on and until I declare your training complete, you are not to duel with anyone unless I give you permission. You may not swing a sword—even that Shardblade of yours—unless it is under my direction. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir!” Merin snapped, spearman training returning.

“And don’t call me ‘sir’ either,” Vasher said with a bitter scowl. “You’re a lord, not a footman. Follow my rules if you wish, learn from me as you wish, and leave as you wish. I care not.”

“Okay . . .” Merin said, eyeing the arrow with skepticism.

“Good. Now, watch.” Vasher turned, falling into a stance and raising his sword. He stood there for a moment, then turned expectant eyes on Merin.

Merin quickly mimicked Vasher’s stance. The monk walked over to him, nudging Merin’s foot forward a few inches, correcting his posture, and showing him how to grip the arrow.

“Good,” Vasher said. “How high can you count?”

“Uh, I don’t know,” Merin confessed, holding still in the stance. “As high as I want, I suppose.”

“Good,” Vasher said, turning and walking back toward his dueling partner. “Hold that stance for a thousand heartbeats. When you’re done, let me know and we’ll do another.”

Merin frowned, but the monk said nothing further. A bead of sweat rolled down Merin’s cheek in the sunlight. What have I gotten myself into? he wondered, sighing internally.

September 19, 2017

Salt Lake Comic Con & LDSPPA

Hey, all! Oathbringer’s release feels like it’s just around the corner–some of you may disagree with me on that–and for those of you who are reading the excerpts on Tor.com, you can now read chapters 10–12 on their website.

My other project, The Apocalypse Guard, is moving along nicely. I recently finished the first draft and submitted it to Random House. Huzzah!

In the meantime, however, I wanted to let you know that I’ll be attending Salt Lake Comic Con this weekend and LDSPPA on Saturday. Like other years at SLCC, I’ll have a full-blown booth with T-shirts, signed hardcovers, and lots of other swag for sale—including the convention exclusive hardcover of Snapshot and Dreamer.

Here are my schedule and booth details. You can see my full schedule here.

Dates: Thursday–Saturday, September 21st–23rd

Address: Salt Palace Convention Center,

100 S W Temple,

Salt Lake City, UT 84101

Booth: 1611

Thursday, September 21st

Magic: The Gathering – The Chess of Card Games

Time: 4:00–5:00 p.m.

Location: 251A

Fantasy: Blending Realism with Magical Systems

Time: 5:00–6:00 p.m.

Location: 250A

Signing

Time: 7:00–9:00 p.m.

Location: Booth 1611

Friday, September 22nd

Writing Excuses: Salt Lake Comic Con Edition

Time: 12:00–2:00 p.m.

Location: 151D

Signing

Time: 2:30–3:45 p.m.

Location: Booth 1611

Saturday, September 23rd

LDSPPA

Time: 1:00–1:50 p.m.

Location:BYU Salt Lake Center

Room: 101

The Brandon and Dan and Brandon and Mary and Howard Show

Time: 3:00–4:00 p.m.

Location: 151D

Spotlight on Brandon Sanderson

Time: 4:00–5:00 p.m.

Location: 151D

Signing

Time: 5:30–7:00 p.m.

Location: Booth 1611

September 18, 2017

Way of Kings Prime Chapter 5: Merin 2

Three days after the battle, clinging to his horse’s saddle as the ground blurred by below, Merin had cause to regret his oath to Lord Dalenar. Every hoofbeat jostled, threatening to hurl him to the deadly stones below. White-knuckled, he gripped the saddle and whispered lines from The Arguments—inside, however, he doubted it would help. The Almighty allowed fools to bring their own fates, and Merin had certainly been a fool for climbing on the back of such a dreadful beast.

Finally—blessedly—the horse lurched to a stop. Merin carefully raised his head, hands still gripping the saddle. Lords Aredor and Renarin had stopped their horses, and his own animal had followed their lead. Merin had been half afraid that the creature would just keep on going into eternity, bearing a long-decayed Merin in its saddle.

Lord Aredor swung off his horse, dropping to the stones below. “See,” he said, looking back with a broad grin. “That wasn’t so bad.”

Merin shivered. “Aredor, that was the most horrible experience of my life.” The first few hours, traveling at a moderate speed, had been bad enough. Aredor hadn’t suggested a gallop until they neared their destination. Merin should have known better than to ask what exactly a ‘gallop’ was.

Aredor laughed, handing his reins to an approaching soldier as his brother dismounted as well. “You’ll get used to it.”

Merin looked woozily down at the ground, not trusting his legs to move just yet. “I think not. Man wasn’t meant to travel that fast, Aredor. It was terrifying.”

“Ha,” Aredor said, walking over to offer Merin a hand. “This from the man who fearlessly attacked a Shardbearer with no weapon but his own hands?”

“Yes,” Merin said, carefully sliding out of the saddle. “But I did that on my own feet.”

Aredor chuckled again, moving over to speak with the nearby squad captain. Merin stood unsteadily for a moment. There was a dull ache through the lower part of his body, reminiscent of that first horrible day when he had joined the army and begun his training with the spear. Soreness would set in before too long.

He sighed, turning back to his horse and untying his Shardblade from the back of the saddle. The roan beast looked back at him, watching with an almost amused expression—as if it received no end of pleasure from torturing those who saw fit to climb on its back.

Though several days had passed, Merin still felt a strange numbness regarding his new position. It just didn’t seem possible that he was a lord. Who was he, Merin of Stonemount, to carry a Shardblade and ride with Lord Dalenar’s heir? Yet whenever Merin slipped and called Aredor ‘my lord,’ the older man was quick to correct him. In fact, Aredor treated Merin like an equal. Like a friend. True, Aredor had been ordered to help Merin adapt, but the man hardly needed to be as accommodating as he was.

Merin tried to maintain his perspective—as Meridas had said, he wasn’t really a lord, not like the others. However, Aredor’s affable personality was disarming; Merin couldn’t help treating the man like one of the spearmen from his squad. Or at least a very well-dressed and mannered spearman.

Merin sighed, hefting his Shardblade and resting it on his shoulder. That seemed to be the best way to carry the weapons until they were bonded. He turned, studying the landscape. The scenery was familiar—the barren stones and distant cliffs proved that he was still in Prallah. The main bulk of the army had moved on toward Orinjah, the once-capital of Pralir, creeping at the pace of the unwieldy creature it was.

Merin was looking forward to leaving the third peninsula, traveling through the Oathgate back to Alethkar. He’d never seen an Oathgate before, but apparently one could use one to transport instantly back to Ral Eram, the capital of Alethkar. Ground that had taken years of fighting to cross could instead be covered in a few heartbeats. However, Orinjah would have to wait, for the moment. Dalenar had ordered his sons and Merin to return to the scene of the battlefield several days before; Aredor had yet to explain their errand to Merin.

“It’s so cold here,” Renarin said in a quiet voice.

Merin paused as a young soldier led his horse away. Renarin stood a short distance away, beside a small hill.

“Cold?” Merin asked. While the stormlands were generally a bit cooler than Alethkar, it was still midsummer. It was rarely ‘cold,’ except maybe following a highstorm.

Then, however, Merin noticed the smoke. Ahead of them, just over a slick-topped hill, several dark trails crept toward the sky. Burning stations—the places where those soldiers unfortunate enough to draw corpse duty were gathering and burning the bodies of their fallen comrades. Thousands of men had died on this battlefield—many more Prallans than Aleths, but in death all were treated the same. Their corpses were transformed through fire, their souls sent to the Almighty, continuing the cycle of Remaking.

Renarin stared quietly up at the columns of smoke. He was so different from his brother. Short with dark, curly hair, Renarin was as unpretentious as Aredor was outgoing. Yet both had a strange way of drawing one’s attention. Aredor did it with sheer force of personality, Renarin with his unnerving, somber eyes. Apparently Merin and Renarin were the same age, but Merin always felt like a child before those eyes.

Merin shivered slightly, reaching for his glyphward—then realizing he didn’t have it on. Aredor had given him some nobleman’s clothing to wear beneath Dalenar’s cloak. The seasilk was unusually soft on his skin, not to mention amazingly tough. It wasn’t as lavish as his cloak, but it was noble, and he had decided not to wear the crom-stained glyphward his mother had given him the day he left for the war. Now, he wished he hadn’t been so prideful. He stood uncomfortably beside Renarin, glad when Aredor finished his conversation and approached.

Aredor paused beside the two of them, growing subdued as he regarded the trails of smoke. “Come on,” he said, nodding to the horses.

Merin groaned. “You’re kidding.”

“Just a short distance this time,” Aredor promised. “The second battlefield isn’t far away.”

So this is it, Merin thought, looking across the simple field of rock. This is the place where Renarin lost his Shardblade. Like everyone else in the army, Merin had heard the stories of the strange midhighstorm battle. Five thousand Aleth troops and three Shardbearers had faced down and defeated a troop of twenty thousand, killing the Traitor and the Pralir king in the process.

Merin looked down at his Shardblade. It seemed unfair to him that Renarin should bear the king’s anger, losing his Blade on the same day Merin had gained one. Merin’s weapon still showed the markings of its previous owner, though they were hidden by the impromptu ‘sheath’ Aredor had given him. The sheath was little more than a folded piece of metal, shaped so that it could be placed over the sharp edge of the Blade and tied tight at the back. The sheath was another remnant from Epoch Kingdom days—it had been fashioned from the same metal as Shardplate, to be used by men during their hundred-days bonding period.

Set in the pommel, held by four clasps, was a medium-sized opal. Merin eyed the stone carefully, looking for some sort of change in its color. He could find none—it still glistened with the same multi-colored sheen as before.

Aredor chuckled, clasping him on the shoulder. “It’s only been a couple of days, Merin,” he said. “You won’t be able to notice anything yet.”

“How long?” Merin asked.

Aredor shrugged. “You should begin to see a change in ten days or so. Don’t worry, it’s working. When the stone has turned completely black, one hundred days will have passed, and you’ll have bonded the Blade.”

Merin nodded. Ahead, Renarin was already walking down the trail to the battlefield. Merin grimaced slightly as the wind changed, bringing with it the stink of death. While the main battlefield was mostly clean of bodies, this one had barely been touched. A small squad of men worked at a burning station short distance away, but most of the corpses still lay where they had fallen.

“Aredor,” he asked, frowning. “What winds brought us here?”

“You were a spearman, right?” Aredor asked, handing Merin a seasilk handkerchief that smelt strongly of perfume.

“Yes,” Merin replied, thankfully holding the cloth to his face as they followed Renarin toward the battlefield.

“Father wants you to look at the uniforms and armor of the dead men,” Aredor explained, voice slightly muffled by his cloth. “Look for anything . . . odd.”

“Odd how?”

“I’m not sure,” Aredor confessed. “Anything irregular or out of place—discrepancies that make you think the men might not actually be from our army.”

“What?” Merin asked, frowning.

Aredor paused, eyeing the battlefield distrustfully, then turning toward Merin. “Something very strange happened here, Merin. You were a footman. How would you feel, facing a force four times your size? How likely would you have been to win?”

Merin shivered. Four to one? Two to one was practically an assured loss. “The king says that the Almighty gave them victory,” Merin replied.

“The king says a lot of things,” Aredor replied. “He doesn’t believe my father’s suspicions—he claims that one Aleth soldier is easily worth four Prallans. In a way, he’s right. Our men have far better training, superior equipment, and strong morale . . . but even still, four to one?”

“But what other explanation is there? The Prallans wouldn’t have killed themselves.”

“No, but someone else might have done it,” Aredor explained. “Father thinks there was a third force in this battle. One of the arguments against a third army is the fact that they left no bodies behind. Or at least that’s what it seemed like originally.”

“Lord Dalenar thinks they were disguised?” Merin asked.

“It would answer a lot of questions,” Aredor said. “The third force could have approached the battlefield wearing Prallan uniforms. Once they attacked, their dead would have been indistinguishable from those they killed.”

Merin nodded, turning toward the battlefield again. Several Aleth soldiers approached, bowing and giving them rods to use for examining the bodies. Even still, it was grisly work. Merin, however, had been assigned to corpse detail before. After a while, he was able to ignore the faces and focus on the uniforms.

He picked across the field, Aredor doing likewise. Merin tried to look for anything unusual or suspicious. It was difficult work. Footmen were given weapons and armor at the beginning of their training, and cared for their own equipment—oiling and polishing after highstorms, fitting and padding to improve flexibility and reduce discomfort. It was difficult to distinguish what might be odd, and what was simply personalized.

The Aleth soldiers wore leather skirts and vests covered by wooden plates running down the chest. It was relatively cheap, but still effective—the leather and wood could be created easily through Awakening, and required no further smithing. The Prallans wore similar materials, though it was more piecemeal and of a far lesser quality. Merin didn’t know the enemy uniforms well enough to determine if they were odd or not. All of them seemed similar enough.

Merin picked his way across the field. Most of the men appeared to have died from crushing blows. He knew to recognize spear wounds, and most of these wounds weren’t caused by spears. The corpses were bloodied and mangled, but they weren’t cut. Other than that, he had difficulty discerning anything strange.

Eventually, Aredor approached him, waving his hand. They retreated to the peripheral of the battle. “Anything?” he asked.

Merin shook his head. “I don’t know, Aredor. I keep seeing things that might be odd, but then again they might just be individual peculiarities.”

“I agree,” Aredor said. “I did a quick count, and there appear to be about five thousand Aleths—which is the number Renarin sent. If the third force imitated our men, they didn’t leave enough dead behind to make it noticeable.”

“And if they imitated the Prallans?”

Aredor sighed. “I looked. I can’t see anything—I don’t think even the Prallans could. They were forced to stretch for resources during the last part of the war. A lot of their soldiers had makeshift armor, or none at all. You can’t find inconsistencies where there’s no regularity.”

Merin nodded.

“We could count the enemy numbers,” Aredor continued, musing to himself, “but we never did have a very accurate count in the first place. Of course, it would make sense for a third force imitate the Prallans, since they’re less uniform.”

Merin nodded, looking across the field again. He and Aredor stood near the western edge, beside a rift in the ground. At first, Merin thought it might have hid some secret, but the chasm was obviously empty. Its empty bottom was smooth and well-lit in the afternoon sun—no caves or other secrets hid in its sides.

“There is one thing,” Merin said.

Aredor raised an eyebrow.

“These men weren’t killed by spearmen.”

Aredor nodded. “Father noticed that too. The third force must have been very well-equipped with heavy infantry.”

“Yes,” Merin said. “But I think it’s more than that. There should have been fields of sliced-up bodies where the Shardbearers fought.”

Aredor paused. “By the Truthmaker!” he said. “You’re right. I didn’t see any bodies killed by Shardbearers—yet we know there were at least five on the battlefield. Our three, the Traitor, and the Pralir king. The Prallans probably had a couple more too.”

Aredor stood with a dissatisfied posture, regarding the battlefield again. As he thought, Renarin approached. Dalenar’s second son paused a short distance from Merin and Aredor, however, choosing to turn and stand apart from them as he began his own contemplations.

Dalenar’s second son had looked through the battlefield as well, but his movements had been more erratic. He hadn’t examined bodies like Merin, or made counts like Aredor. Eventually, Renarin whispered something to himself.

Aredor turned. “What was that, Renarin?”

“I said that this is my fault,” the younger son repeated. “I sent these men to their doom. The king was right to take my Blade away.”

Aredor walked over, placing a comforting hand on his brother’s shoulder. “You didn’t do anything wrong, Renarin. The king would probably have done exactly what you did.”

Renarin shook his head, falling silent.

Merin joined them, studying the battlefield with a careful eye. He was no military expert, but he had spent several years fighting, and had seen large battles before. “I don’t know much, Aredor,” he said, “but I think your father might be right about the third army.”

“Yes, but the king will want evidence,” Aredor said, stepping up beside Merin. Behind them, Renarin sighed and sat down on the ground, staring down at the rocks in front of him. “Elhokar can be winds-cursed stubborn, and he doesn’t want to bother with the possibility of a third army.”

“Then we have to find a way to prove that some of these corpses in Prallan uniforms weren’t part of the Traitor’s army,” Merin said. “That has to be the answer.”

“No,” Renarin whispered from behind.

Merin turned, then shivered. Renarin was doing it again, looking at him with those eyes of his. Staring, yet unfocused.

“These corpses were all either men from our army, or men from the Traitor’s force,” Renarin said.

Aredor frowned. “You’re saying there wasn’t a third army?”

Renarin shook his head. “There was. It just didn’t leave any bodies behind. They must have taken their corpses with them.”

Merin frowned, looking back at the battlefield. That seemed like an awful lot of trouble to go through—not to mention the time factor. The highstorm had been only a couple of hours long. It would have been near impossible to kill twenty-five thousand men in that time, let alone pick out the corpses of the fallen and transport them somewhere.

Merin turned skeptical eyes toward Aredor. The elder brother, however, was regarding Renarin with interested eyes.

“You’re sure, Renarin?” Aredor asked.

Renarin nodded, looking a bit sick. “I can see it in the patterns of their bodies. There were dead here that are gone now.” He waved distractedly toward a section of the battlefield. “The two sides had begun to disengage, in preparation for the highstorm. Then someone else came—over there, on the southern side. After that, our men and the Traitor’s army fought together. They’re all dead now, though. Every one.”

Aredor stood for a moment, contemplative. Renarin volunteered no more.

“Let’s go back,” Aredor finally said.

As little as Merin wanted to admit it, the trip back to the army was nowhere near as arduous as the previous ride had been. Perhaps the growing soreness and fatigue in Merin’s body distracted him from the unnatural motions, or perhaps the ‘gallop’ before had shown him that regular horse speeds were comparably sane.

As the hours passed, his grip relaxed, his mind too tired to bother being terrified. Evening was approaching by the time they reached the location of the army’s morning campsite. It was, of course, now empty—the army had moved on, leaving behind remnants of cloth, trash, fire scars, and cesspits.

The three continued riding. Aredor was confident that they could reach the army by nightfall—Orinjah was supposed to be less than a day’s march from the campsite. Indeed, as they moved on, Merin began to notice a gradual shift in the landscape. They had already begun to leave the stormlands behind, and as they moved further to the southeast, the scenery became eerily familiar.

The barren rock of the highlands changed to the more sheltered hillsides of common farmlands. The rocky hills lay in belts of land sheltered by the higher grounds nearby, which weakened highstorms. The lower the elevation, the more prevalent rockbuds became, until the stonelike polyps could be seen growing here and there on nearly every surface. Roshtrees hung from overhangs—they appeared as wide tubes of stone at the moment, but after highstorms they would let down vines covered with foliage, and sometimes fruit. A few of the more sheltered ones even had their vines down in the evening coolness.

The most telling sign of the farmland, however, was the hills that had been cleared of rockbuds and other plant life. Though barren at the moment, they bore ringlike scars made by inavah polyps, which had clung to the hillsides before the summer harvest. They were so similar to the fields of Stonemount that they could have been in Alethkar, if it hadn’t been for the ragged highlands behind them and the absence of the Mount of Ancestors in the distance.

The road itself was clean of polyps, and beyond that it was easy to see where the army had traveled. Rockbuds were resilient, but their shells were far more brittle than regular stone. A large swath of them lay shattered—shells broken, delicate stalks inside smashed flat—by tromping soldiers bearing metal-heeled boots. The remnants had already dried in the arid summer air.