Tania Kindersley's Blog, page 76

July 1, 2013

Drama; or, the arrival of the black helicopters

High drama in the night, as helicopters with searchlights hover low over the village. The Horse Talker wakes up at 3am to find her entire house is shaking. Thinking only of what the horses must be making of this unexpected airborne activity, she rushes up in her pyjamas to check on the herd, whilst Stanley the Dog and I sleep through it all.

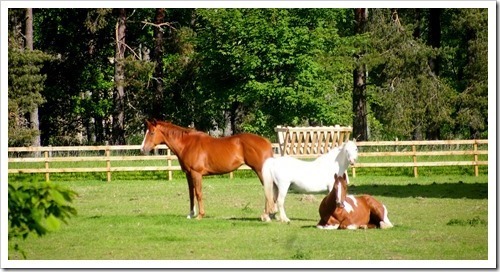

She finds the little band amazingly calm. Red the Mare has taken up her familiar station at the head of the pack, in protective stance.

Red does this when there is any fracas or hullabaloo. When unexpected fireworks go off, and I race to the paddock myself, I always find her staunchly in place, between her two charges and the potential danger.

It touches me amazingly how seriously she takes her duties as lead mare, and it is one of the things I love most in her. She has never been a boss in her life, and had to learn it all as she went along. At first, she over-compensated madly, preening and prancing and dancing round the field with her tail stuck vertically in the air and her head stretched to the sky, performing impossible bucking and rearing combinations to indicate her dominance. Now she gently moves her two girls round the field from time to time, to remind them she is in charge, and doggedly keeps them safe from any perceived harm.

It turns out that a poor old lady wandered from the local care home in the night and lost herself on the hill. Police, sniffer dogs and mountain rescue all joined in the search, and she was found and taken to Aberdeen Infirmary. It astonished us all how much manpower was hurled at the problem and how quick and efficient the effort was. But since the most noise we hear in the night is usually the cry of the oyster-catchers and the occasional chilling death-yell of the owls as they hunt small creatures, it has been a bit of a shock all round. In the newsagent, they can talk of nothing else.

The touching thing, from a personal point of view, is the joint custody of our field. Whilst I slumber, the Horse Talker is on full vigil. First thing in the morning, I take up the baton, and go to check the herd myself. Autumn the Filly has suffered some mysterious stiffness and imbalance, we are not sure whether coincidental or not, and I spend half an hour checking her before sending off reassuring emails. Then, the two of us meet to survey our girls, relive the night’s events, and give everyone a soothing pick of the lush grass in the set-aside.

Sole responsibility for equines is a heavy burden to carry; we are both lucky enough to have each other to lean on. It’s not just when things come out of a clear sky, as they literally and metaphorically did last night; it’s also that it’s lovely to have a witness, to share the progress and the triumphs and the enchanting, funny things that the girls do. It would not be nearly so lovely if there were only one set of eyes to see all that. It goes back a little to my previous theme; it is Look, look, and the giving of time and attention. It is why, I suspect, people put up their horsey pictures on Facebook or share links on Twitter. The horse love is a consuming one, and sometimes it spills over and needs to be shared.

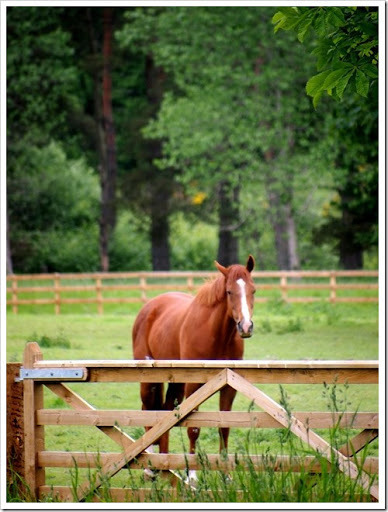

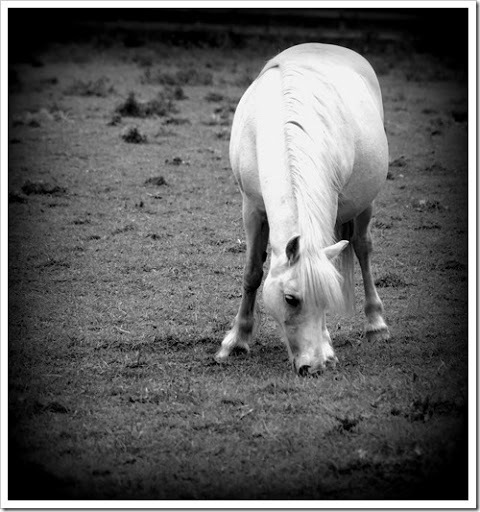

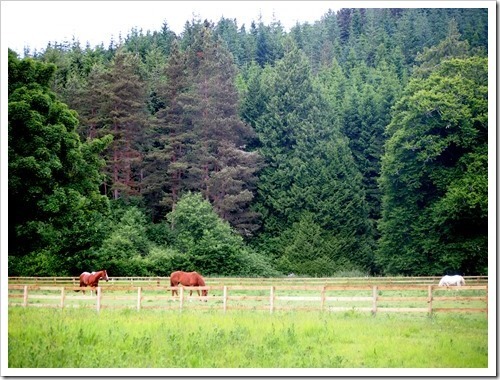

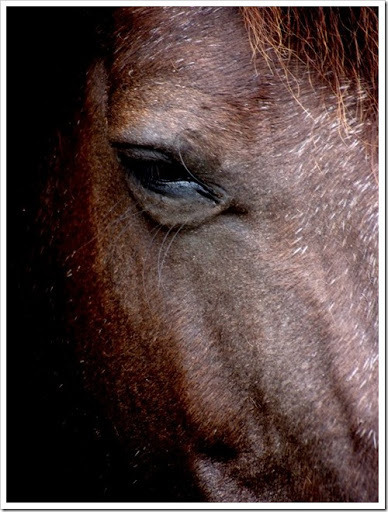

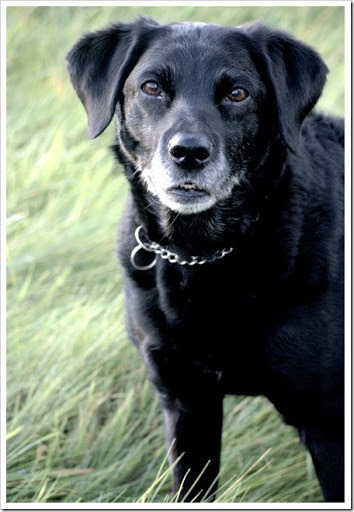

The day is cantering away from me now, so just time for one picture today. I have not managed to catch a good herd photograph lately, so this one is from a couple of weeks ago, showing my dear girl watching over her little herd. One should not get sentimental about horses; they are not sentimental about us. But it does bring a tear to my eye:

June 30, 2013

Look, Look.

‘Look, look,’ I cry to the Horse Talker, like an eager six-year-old child. ‘Watch this.’

She kindly watches.

I break into a run. Red trots gently by my side. I slow to a walk. She at once walks. I run again; she trots. I walk, she walks. I stop, she stops.

‘ISN’T SHE CLEVER?’ I yell.

The answer can only be yes. The Horse Talker sweetly supplies it.

I very rarely use the Universal We. It drives me nuts, most of the time, especially when it comes to women. We, say ladies on the radiophonic device, or in the magazines, or in the newspapers, all want X and Y and a bit of Z. What We want is often negative: to banish wrinkles, lose six pounds, get rid of cellulite.

Bugger off, I shout; I don’t want any of those things. I may have ovaries, but I have no interest in diets or shoes. Don’t tell me what I want; we have not even met.

But I dare to venture that We, as humans, almost all have a little voice in us which says: Look, look. Watch this. And what interests me is the things we choose to shout about. It may be: look, look, I can write a thesis, or make a million pounds, or drive a shiny car. It may be: I can make a garden or write a sonnet or do fascinating things with an old Fairy liquid bottle and some sticky-back plastic. (Or, in that case: look what I can do with nostalgic Blue Peter references.)

I suspect that possibly the road to inner peace leads to the quiet prairie of not having to prove oneself. Perhaps really, We should all try to get past the Look, Look voice. It is a form of pride and showing off, really. But on the other hand, it is very human. Someone said to me the other day that she thought life could be boiled down to needing three As: affirmation, affection and attention. The most generous thing you can give to a person is your time. You can watch, you can pay attention; you can be a witness.

For some reason, I quite like the fact that my current Look, Look involves something so basic that it would never make a YouTube hit. The other day, I watched a video on the internet of a young New Zealand woman putting a horse into counter canter without a saddle or a bridle. It was skill of a dazzling degree, and so natural and relaxed that it made me gasp.

I have to accept that I shall never be able to do that, just as I shall never be able to play a Mozart sonata, or sing like Nina Simone, for all my private efforts in the kitchen with only Stanley the Dog to hear. (I can, if the light is coming from the right direction, get a little blues break into my voice, and when that happens I flush with idiot pride.)

Yesterday, I did another kind of Look, Look. I had a two pound bet on four horses. My old dad loved nothing more than an accumulator and I do one pretty much every day, for fun, for the challenge, for the memory of the auld fella. I imagine him laughing his head off in the great William Hill in the sky.

My four lovely horses won. The bet paid £207.96. I was beside myself. I took at once to Twitter, to tell everyone. Well done, my racing posse said kindly; you deserve it, they tweeted, generously. Then I felt slightly ashamed. I metaphorically cleared my throat and shuffled my shoes. Of course, I wrote, I don’t tell you all about my utter catastrophes. I was incredibly proud, and flushed with the thrill of the thing, but then I felt a bit bogus, boasting about it.

I’m not quite sure what the point of all this is. I did have a good point, when I started. I like to tell you small stories which have a moral to them. I like to dig out the life lessons, over and over, to remind myself. I learn things and then forget them and have to go back, endlessly, to the beginning.

I think perhaps the point was something about the small things, my enduring theme. I think it was that there will always be a bit of Look, Look, and even though I would love to be able to do complicated steps and championship manoeuvres, I rather like it that my current totem of utter achievement is that my horse and I may move in harmony. It’s not fancy, but it’s real.

Today’s pictures:

Are of the past week:

Ha. Just as I was about to send this, an email dropped into my inbox, from one of my various Google Alerts. It was from CNN. CNN, without fear or favour, was asking the big questions this morning. Are women foolish to love stilettos? it wanted to know. Talk about the utter idiocy of the universal we. There are about eight-seven things wrong with that question. I almost jumped onto the highest of my high horses, ready to gallop off in all directions. Then I thought: it’s a Sunday. The birds are singing. Stanley the Dog is stalking a fly in the next room, amusing himself mightily. I put the horse away. I laughed, instead.

June 28, 2013

A little bit of The Other.

I am in wandering, pondering mood today. I am interested in thought processes and the mazy meanderings of the human condition and how it is that people define and redefine themselves. I was thinking about this because one of the things about my work at HorseBack is that it demonstrates to me that I am a bit Other. I meet a lot of new people there all the time, and, after years of sticking quietly to my own cohort, I am suddenly exposed to the eyes of strangers.

I see a lot of revealing looks in those eyes. There is surprise, amusement, that particular indulgent look which I sometimes see in the glance of my mare, the one that says: ah, the old girl is off on one again. I say things which to me seem quite ordinary, and watch people take a metaphorical, sometimes even literal, step backwards. Sometimes I can identify the thing which causes a faint shiver of shock; sometimes I cannot, and go home and wonder about it.

I am aware that I have something of the idiotic about me. I don’t mind this. The absurd bit of my brain even quite likes it. When I meet the very grown-up, organised, proper, capable people I do have a momentary, almost melancholy sense of envy and wonder. How lovely it must be, I think, to do things well in the world, to have a plan, to know where your car keys are. I told someone yesterday that last week I spent half an hour looking for my keys, only to find them in the flower bed. She is a very polite person, and masked her utter astonishment well.

The pondering on this makes me think of my dad, where some of it comes from. On paper, he was a very peculiar person indeed. He got away with his absolute refusal to live by any of society’s rules through a raging, entirely authentic, natural charm. His charm was not of the Charm School variety; he never remembered people’s names or asked them suavely about their lives. He did not tick the ABCs of polished behaviour. His charm was a sort of innocent enthusiasm, a constant subliminal laughter at his own absurdity, a self-deprecating jokiness, an open generosity of heart.

I used to go and stay with people when I was a little girl, and meet fathers who did serious nine to five jobs, often ones which required a suit and tie, and I remember a confused feeling of mild envy and utter strangeness. I had absolutely no clue what it might be like to have a respectable parent. My dad drank for Britain, sang Irish rebel songs using an upturned tea chest as a double bass, gambled so hard that he sometimes left a racecourse with cash by the case, flirted with every woman he met, rode so wildly that many of my childhood memories are of being told to be quiet by strict matrons in hospital corridors. My early youth was filled with antic stories, like the time that a storied Irish band came to stay, and went on such a bender that the only way Dad could get them back to London for a gig was to load the musicians into the horsebox with three crates of Guinness and send them off up the M4, still singing.

Because when you are small you accept what you live with as utter normality, these proper fathers who earned regular salaries and allowed themselves one small Fino before lunch seemed entirely alien to me, a fascinating life-form to be studied from a distance, dissected for clues of how The Other Half lived. I really liked them, and sometimes wanted one for myself, but I could not quite imagine living in their good, ordered world.

Our world was not ordered. The house burst with people, song, the veering highs and lows that go with racing; my father smelt of earth and dung and a lovely citrussy hair oil from Mr Trumper, which is what men in the seventies used to wear. (Hair oil; that really is the mark of a lost world.) The conversation was almost exclusively about equines; I felt most at home in the tack room, with the scent of leather and saddle soap in my nostrils. Gambles were landed and lost; horses celebrated and mourned; the fortunes of the house shot up and down like crazed Mexican jumping beans.

No wonder that sometimes people give me looks. I think that I thought for quite a long time that if I watched carefully I could learn to fit in, and behave in an expected manner. But you can only work with what you have been given. The faint otherness persists, and I don’t think that it matters so very much. And I also suspect that even behind the most respectable facade, even under the neatest tailoring, even in the midst of the most regular life, everyone, secretly, has their own goofy little star, which they quietly follow.

Today’s pictures:

Dreich and rain today. HorseBack morning:

A lot of new flowers and growing things are out in the garden:

Best Beloveds:

Where the hill should be:

June 27, 2013

Small but mighty.

Ha. It turns out we do not need Miss Marple after all. The Dear Readers are on the case of The Mysterious Incident. One of them, to my delight, turns out to be an ex-copper and has put her considerable forensic and analytical skills to work. She concludes that a possible explanation may be rogue deer.

‘Oh, yes,’ I say out loud, as I read the clever comment. At once, this makes the most sense of all the crackpot theories that are jostling in my brain. My current favourite was that a psycho rambler, who, furious that I have put up a fenced paddock in the middle of the old rambler’s route up into the hills, which is rudely not marked on any Ordnance Survey map, had come in the night to wreak his revenges. You can see why I never applied to the police force.

This makes me think of the shining marvellousness of the Dear Readers. When I started this blog, I wanted to make my book go viral, build a brand, make some commercial hay. It was a hard-nosed business decision. Of course, none of that happened. I built a small readership, but nothing like enough to have any effect on sales.

I did, even so, for a long time become obsessed with numbers. All the graphs did go reassuringly upwards, and I checked them mercilessly and castigated myself if I ever suffered a little dip. I was always racing to the internet to see how many views I had received and comments I had got. If there were fewer than the day before, I felt quite awful.

Then, as HorseBack came into my life, and my working day became chewed up by trying to fit in volunteering and day job and mare and family and dog and exigencies of ordinary existence, I, without even meaning to, just stopped looking at the figures. The last I looked, a few months ago, the graphs had gone down a bit, probably because the blog has become more inward-looking and less polished and, in an odd way, less needy. When I was busking for custom, I did sometimes get it. Now the thing exists easily, in itself, not trying to gain anything or prove anything or score points. The dear old blog does not mind if the numbers are small. It is just what it is, comfortable in its own skin, operating without fear or favour.

But what is so lovely is it seems, in some serendipitous way, to have found its perfect level. The Dear Readers may not be counted in vast marching battalions, but oh, feel the quality. They can solve mysteries; they fall openly in love with Stanley the Dog. They remember, tenderly, the Pigeon, and allow that my heart still aches for her. They put up with long ramblings about racing, which they do not follow themselves. (Some of them, who have never watched a race in their lives, even turned on the television for Ascot.) They come and wave hello from America and New Zealand and Austria and Sri Lanka, and all points in between.

Perhaps it comes back to my middle-aged obsession with the small things. I do not disdain worldly success, but the profound satisfactions of the heart are now all in the minute, the minuscule, the barely visible. The delicate barometers of Red’s mood and the merest wibble of that famous lip; the flight of Stanley the Dog’s left ear; a particular expression on Myfanwy’s face; the sight of the Scottish light on an old oak tree; the leap of a lamb in the field; these are things which mean the most.

The cohort of the Dear Readers is small, but oh, it is mighty.

And that is my happy thought for the day.

Hardly time for pictures, as I am, as always, racing the damn clock. Here is just a little something on which you may rest your kind eyes:

June 26, 2013

In which a mysterious event occurs.

Here is the ridiculous story I was promising you.

It took place two nights ago.

At 9.31pm, on a quiet Monday, I hear the four words I dread the most. ‘The horse are out.’

The Horse Talker and I like to lean over the gate and watch our little herd with adoring eyes, and discuss at vast length how calm, how tractable, how happy, how unshockable they are. This is faintly self-indulgent, since it is partly due to the work we have done with them. We had fabulous raw material to work with, but the daily groundwork, desensitising, attention to detail has paid off, and we are not above the occasional naughty clap on the back. We are only human after all.

Then suddenly, out of the blue, they go nuts in the night and completely trash a strong wooden post and rail fence.

The neighbour who lives next to the field hears an almighty crash, and looks out to find the two bigger mares racing at full speed past his window. What is so funny, in retrospect, is that having got out into the wide yonder of the rolling set-aside, they choose to rush back to the top gate and try to get back into the paddock, as if in apology for their errant behaviour.

I tear down and round them up and get them back in. The Horse Talker arrives, and we survey the devastation. One whole bottom rail has come completely off, two discrete top rails have been trashed and smashed and are at crazy, splintered right angles. But the really, really weird thing is that they are facing inwards, as if the force which broke them came from the outside.

The Horse Talker and I turn at once into a pair of equine Miss Marples. We examine the hoof prints, the skid marks on the grass, the trajectories. I actually attempt to reconstruct the incident, but we cannot see how it was done, with the angles of the breaks the way they are, and also the position of the scratches on Red’s body. Autumn the Filly, true to her amazing, laid-back, get away with anything nature, has come away almost entirely unscathed, except for one tiny scrape on her off fore, which has barely even broken the skin.

None of it makes any sense. Miss Marple herself would be baffled and have to eat her cloche hat. Quite apart from the puzzling nature of the broken fence, which appears to defy the laws of physics, horses would have to get into a terrible state to crash through a sturdy post and rails.

Tractors, trailers rattling with blocks of granite, and a variety of thundering diggers come in and out of that field all the time. There is a random person who lets off loud gunshots in the woods. Strange groups of ramblers appear, rustling their Ordnance Survey Maps. The herd does not bat an eye.

When the shelter was being built, the shattering noise of the nail gun did not even cause them to lift their heads from their hay. Close by, the old Coo Cathedral, a palace built for cows in the 19th century and now used for weddings, sees firework displays on the occasional Saturday night which sound as if civil war has broken out. When this last happened, two weeks ago, I tore down to the field in the pitch dark, expecting to find the girls going nuts. Instead, Red had gathered her little band in the farthest corner, under the soothing shelter of the wooded hill, and was standing between her two charges and the devastating noise. She was alert and scanning the horizon for possible threats, but there was no sense of terror. She was just on watch, that was all.

Who knows what will frighten a flight animal? Red will walk calmly up to a huge, clattering scarlet digger and stick her nose in the cab to say hello to the Young Gentleman, whom she loves, but the other day decided she was really quite shocked by a pair of blackbirds.

Even so, one of the things that I have taught her is not to go into a rising escalation of fear. That’s what the desensitising is for. Slightly paradoxically, it is to teach horses that fear is all right; it is just a thing, it will not kill them. So you crinkle a plastic bag, for instance, and they start and tremble and shoot their heads in the air, and then you indicate by your own body language that the thing is not, in fact a mountain lion, and after a moment, they believe you. There’s also a dance of bringing the terrifying object in, and then removing it; more of the pressure release principle. At the end, we always say to our girls: ‘See? It did not eat you.’ They learn to feel a moment of alarm, but this does not then soar into a rising arc of panic. They come back to us. It does not mean they will never spook, but it means that a three act drama is then much less likely.

And yet, something, something, happened in that field, which must have terrified them out of their wits, a mystery which we may never unravel.

For two nights, it disturbs me so much I cannot sleep. I hate it when anything happens to upset the herd, and I hate to see my beloved Red with Wound Cream all over her beautiful body. Wound Cream, which really is its name, is the most miraculous thing I’ve ever found. It’s by Royal Appointment, and quite right too; I imagine the Queen loves it. You put it on that nastiest cuts and scratches, and the next day, they are healed. Red has one determined cut which is still on the mend, but almost all of her scars are already fading.

I suddenly realise this morning that because I am unsettled by her being unsettled, and because I cannot work out what the hell went on, and because I have not slept for two nights, she is picking up on all that – what the Beloved Cousin calls, descriptively, being jangly. The Horse Talker and I look anxiously at our girls and say to them: ‘Oh, if only you could speak.’ We long for them to tell us the story.

But now, I see this is not the point. I’ve being babying and gentling Red for two days, but this in fact is not what she needs. So I do some proper work with her. Out in the wide three acre field, I work with her at liberty, and she hooks on at once, and drops her head, and follows my feet exactly – a move to the right, a circle to the left, four paces backwards, stop, start, quick slow. There it is, the harmony again. Everything in her big red body relaxes; she has her Good Leader back. That’s all she wanted.

She loves love, and will present herself for it. She will make a sweet face and offer her head for scratching. She will stand for long minutes by my side, leaning on my shoulder as I rub her dear cheek. But this is secondary, for her. Horses experience love in a very different way than humans, and their version of what we call love is mostly based on feeling safe.

She doesn’t want me jangly and fretful. She wants me leading her round a field, confident and certain. Then she can relax. I’d forgotten this for a bit, and this morning I remembered, and my lovely girl let go her nightmares and followed me willingly and with gratitude.

The Bizarre Event starts to fade. I hate mystery. I love explanations. But we have to chalk this one down in the category of May Never Be Solved.

Still, we were lucky. The kind neighbour mended the fence; the other kind neighbour is on full night patrol in his monster truck, just in case any random human agency was involved. Our little herd is protected by the kindness of the compound, their scratched bodies are mending, and they revert to their usual, happy, dozy state.

I have to put away the ghastly imaginings of what might have been, of the potentially catastrophic injuries they might have suffered, and feel grateful that the ending was really a happy one. The best horseman I know, my cousin’s Old Fella, lost a horse not long ago when it crashed through the gate from its field for no known reason, and broke its shoulder. The fates were kind to us; we got off miraculously lightly. I must remember that, and not dwell on the horrors which might have been.

Today’s pictures:

This is an absurd picture of some clouds I took by mistake. But I rather love it. It’s a bit like a painting of the sky:

The herd, grazing calmly, as if Great Escapes never crossed their dear minds:

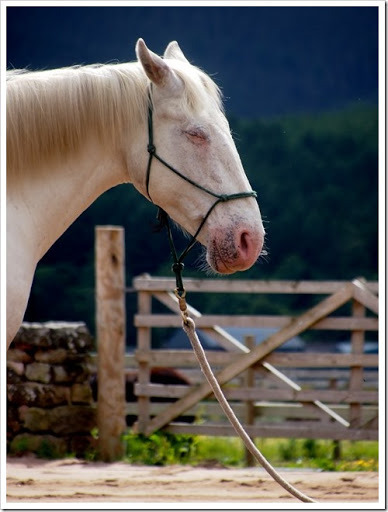

My poor girl, getting back to normal:

Although she would like to show me all her battle scars, masked by the wonder Wound Cream:

M the P, unfazed by the entire event:

And Mr Stanley the Dog is most concerned with catching bluebottles:

The hill, which stays unchanged through it all:

June 25, 2013

No time, but a lot of pride.

I have a good drama story for you but I’ve run out of day in which to tell it. The imaginary equivalent of the Countdown Clock has bibbled and bobbled its way to the end of my round, with that cheery yet rather ominous sound, and that’s all she wrote.

I will tell the story tomorrow, because it is actually a proper mystery and perhaps the Dear Readers might be able to solve it. In the meantime, there is just enough time to say -

LOOK AT WHAT THE OLDEST GREAT-NIECE CAN DO:

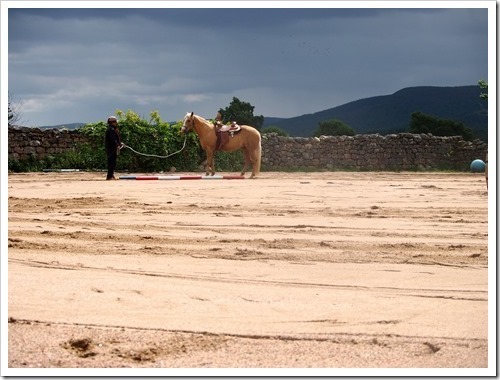

This small person was not the rider in the family. Before Myfanwy had to be retired from being ridden, The Oldest Great-Niece sat on her a couple of times, but she never felt at home in the saddle. That was perfectly fine. She had other areas of brilliance. No one gets pushed, in this family. Then, one day, without telling me, she went up into the hills and started taking secret lessons, and NOW LOOK.

I am so proud I could burst.

Story, all polished and in forensic detail tomorrow. In the meantime, a couple of pictures for you:

This was the view the World Traveller and I saw as we watched the miraculous riding lesson:

Back home:

Herd:

HorseBack morning:

Oh, the nobility of Mr Stanley the Dog:

My own dear old hill:

June 24, 2013

Pith. And pictures.

And back to normal we go, the old routine swinging out on a Monday dawning with skies as black as pitch. Up to HorseBack, back to the computer, 916 words of book, do Red, walk the dog, breakfast with the Mother and Stepfather. The wild highs and lows of the Royal Meeting recede, and I must remember that I am a grown-up.

You’ve had to read far too many words in the last few days, so today there are some soothing pictures instead. Although, I would like to express special thanks to the Dear Reader who outed himself as a male and a racing journalist (both are welcomed keenly on these pages) and who paid me possibly the best compliment I’ve ever had. He said that the Ascot reports reminded him a little of Audax. J Oaksey was an old friend of my father’s, from schooldays, and he wrote emotional, fluent reports of great races, sometimes even from the very saddle, where he had a bird’s eye view. People remember them forty years on.

No one could have said a kinder thing, or a more reassuring one, since I generally suffer from mild angst when I bang on about the horses. I seem unable to help myself, but it is quite a lot for you to wade through. Anyway, I just wanted to say thank you to that anonymous reader, who made my exhausted heart swell with pride.

This week, my darlings, you shall have pith. Or at least, that is the plan.

Here is some of what I saw last week, when I tore my eyes from the television set and walked outside in the good Scottish air:

And as I was going through the pictures files today, I found these, which made me both happy and sad, equally:

I’m entirely biased. But I’m not sure there was ever someone quite as beautiful as that Pigeon.

June 22, 2013

Ascot, Day Five. Looking back on the lovely Sky Lantern, and ahead to the beloved question mark that is Mad Moose, and the streak of lightning that is Society Rock.

The Queen won her race. The memory of Sir Henry Cecil was honoured, with his widow showing the absolute definition of courage, which Hemingway once described as grace under pressure.

The new boys had their moment in the sun, with Olly Stevens in his very first season as a trainer, and George Baker in his fifth, sending out winners, and the youthful James Doyle racking up a quick-fire treble.

But perhaps the memory of the dancing fillies is what I shall most hold dear – Riposte and Estimate on Thursday, and then, yesterday, the lovely grey Sky Lantern.

I have loved Sky Lantern since I followed her career as a two-year-old. She just held on to win the Guineas, but yesterday she had a much harder task, drawn out wide in a big field. To add to her troubles, Richard Hughes, her jockey, has been having an awful week, meeting trouble in running, making one controversial decision to switch right across the track which he himself admits was not his finest hour. All the armchair jocks were up in arms.

How they howl and carp, these online cavaliers, most of whom have never sat on a thoroughbred in their lives, let alone one that is going at forty miles an hour. Every jockey, like every human, will make a mistake once in a while. Racing is as much an art as a science, and tactics cannot be perfect in every single race. But the punters are merciless and shriek with their pockets, accusing good jockeys of riding to lose or stitching a race up, as if these tough, hard-working professionals are metronomic machines who should never make the slightest error.

I stuck with Sky Lantern in the end, because I love her, and even though I convinced myself the draw would defeat her, and the Irish raider might have the edge, I could not desert her now. I got her at a happy five-to-one, and Hughes dropped her out the back, let her find her own pace, picked up her up about three out, went right past the field in the straight, and won as he liked, easing up.

It was the prettiest of finishes, that delightful thing where the jockey does not even need to wave the whip, but can just keep the mighty animal balanced, riding with hands and heels. Hughes was patting her neck and pulling her ears before he even passed the winning post.

‘Well,’ said my mother this morning, as we relived the race. ‘She can do anything now.’

The second most satisfying moment of the day was a little whimsical each-way shout on Forgotten Voice, trained by Nicky Henderson.

It’s always rather funny seeing the National Hunt trainers at Ascot, all guyed up in their top hats and morning coats instead of a dented old Trilby and thorn-proof tweeds.

For some reason, I love these dual-code horses almost more than anything. I don’t know why. I suppose I am an admirer of versatility. Forgotten Voice had once been high class on the flat, but that was years ago. He’s gone for hurdling now, and to come back to the Royal Meeting is something of a stretch.

Yet he was the pick of the paddock by a country mile, his coat so shining and gleaming you could see your face in it, his head held high with bright spirits, his massive quarters packed with muscle. He was 12-1 and who knows what old form a genuine horse may pull out of the bag? It was worth a bit of anyone’s money.

And the dear old fellow damn well did pull it out of the bag, hanging on for the line against all comers, and I shouted so loudly that this morning my throat is quite hoarse.

Today, my own private dramas will revolve around two horses who could not be more different. One is another of the dual code fellas. Mad Moose is a chaser who is pretty good, but not quite in the very top class. His greatest moment over the sticks came when he chased home the majestic Sprinter Sacre.

He is perhaps the quirkiest horse currently in training, and there are days when he gets it into his mysterious, horsey old head not to go. The commentator starts the call, the field jumps off, and the camera pans back to a slightly disconsolate-looking Sam Twiston-Davies, with Mad Moose standing stock still as his compadres gallop off into the distance, a faintly mulish, bugger you gleam in his eye.

‘Nope,’ he is saying. ‘Not today. No thank you.’

Nigel Twiston-Davies is nothing if not imaginative, so, in a rather radical move, he sent his idiosyncratic old fellow off to the flat, at Doncaster. To have your first run in a flat race at the age of nine is a pretty rare thing in racing. To everyone’s utter amazement, Mad Moose won, at 28-1.

He then went to Chester, where, on a dank afternoon, he finished a plugging-on second to the runaway winner, Mount Athos, with some pretty decent horses in behind.

Suddenly, Mad Moose was everybody’s darling. Hopes were high on a sunny Yorkshire day on the Knavesmire, where he lined up again. The stalls rattled open, and the mighty Moose took two slow steps forward and then stopped. Willy Twiston-Davies flapped his reins a bit at the old fellow and then admitted defeat. Mad Moose stood defiantly still, looking quite grumpy and entirely unrepentant.

Twitter went mad with delight. It’s a horrid thing for the owners, and all the connections, and York is a long way from the Cotswolds, but it was just so terribly funny.

The stewards did not think it amusing. The dry post-race report noted: ‘future similar behaviour may result in the gelding being reported to the British Horseracing Authority.’ Everyone else was beside themselves with delighted hilarity. For some reason, it made his public adore him more keenly.

‘We’ve all had days like Mad Moose,’ wrote one tweeter; ‘where we think ‘fuck it, just can’t be arsed.’

‘What next for Mad Moose?’ said another wag. ‘Dressage, equestrian, rugby union?’

Even his jockey could not help seeing the funny side. Willy Twiston-Davies tweeted: ‘Moosey was naughty.’ His hashtag for the day was #doeswhathewants. The Twitterverse was rocking with laughter. ‘Just makes me love him more,’ said one fan.

I suspect there is something peculiarly British about it all. Of course the people of Blighty love a mighty champion, but what they love the most is the underdog. And an unpredictable, cussed underdog with a mind entirely of his own is exactly what the people of these islands cannot resist.

To see a fellow like that at the Royal Meeting is not exactly what one might expect, and it brightens the gaudy carnival that is the summer flat season. I shall back him for sheer love. The good girls have won me enough money this week, so I can afford some caprice today.

My second big hope is another old-timer, Society Rock. He’s six now, and has been round the block. He could not be more different from Mad Moose if he tried. He is a fleet, strong, shiny sprinter, fast as the wind.

He has, however, had similar travails at the start. At this meeting last year, he reared up in the stalls, missed the break catastrophically, and did well to finish as close as he did to the imperious Australian star, Black Caviar. His trainer, James Fanshawe, took him back to stalls school, worked patiently with the colt, and produced him at York this spring for a thrilling victory first time out.

I’d love him to win because he is a brave, tough, genuine horse. He also comes from one of the smaller yards. James Fanshawe is a supremely talented trainer, admired by his peers, popular in his community. But he is not a household name. He does not pitch up at the sales with a prince or a sheikh or an Irish plutocrat by his side, able to hurl cash around. He does not have two hundred horses to choose from like the massive operations which now hold sway. His yearlings will usually cost tens rather than hundreds of thousands.

I’ve got nothing against the big boys, and admire the skill and success of the Hannons and the Ballydoyle posse. But it’s a lovely thing to see the smaller operations outdo the big guns, and it’s good for racing. It’s a mark of real dedication and skill, to be able to produce top-class winners when you can’t just throw money at the problem.

And Fanshawe has had a cruel blow recently, when his other stellar sprinter, Deacon Blues, succumbed to a recurring injury, and had to be retired just as he was on the come-back trail.

The particularly nice thing was that, even in the midst of that crushing disappointment, all thoughts at the Pegasus yard were of the horse’s future well-being. They wrote on their website: ‘He will make a lovely riding horse as he has impeccable manners and he is very easy to do anything with. His owners will make sure that he has a wonderful home and will be well looked after. He certainly won’t want for anything.’

Beyond all that, Society Rock is owned by Simon Gibson, a gentleman in his eighties who has done a huge amount for Newmarket over the years. No owner would deserve victory more.

So that’s why he would be my happiest story of the day. He’s in a big field, so he will need luck in running. He’s got some exceptionally good horses up against him. But he has the talent and speed and the heart to win, and I hope he does. His dear name will be the one I am shouting at the top of my lungs, at 3.45 this afternoon.

June 21, 2013

Ascot: Day Four. Or, two brave fillies and two remarkable women, and dreams coming true.

Author’s note: this is very, very long. It is about racing. But it is also about the human heart. There were too many stories here to be told, and I could not skimp them. So forgive the length. Indulgence if you like, but glory too.

All meeting, there are two things I quietly, almost secretly, dreamed might happen. They were in the hardly-dare-hope category. Then, after all the drama of the week so far, they suddenly both happened, as if they had been inevitable all along.

Yesterday morning, with my forensic betting hat on, I had picked Lady Cecil’s nice filly Riposte for the Ribblesdale, because she was the only one of the principles who had winning form over the distance. Ascot is a deceptively testing course. From a distance, on the television cameras, it looks gorgeously smooth and flat, but in fact it has nuanced undulations and a stiff uphill climb.

Trainers are not idiots. They do not want to be disgraced on this biggest of stages. They will not send horses here if they think they will not stay. But still, that little D by the side of Riposte flashed at me like a beacon.

I took eights first thing, for a paltry amount. I was still flinty and scientific, admitting doubts; the filly was stepping up in class, she had something to prove. I was damn well not going to let my heart rule everything.

I’ve been watching the Cecil horses all week, hoping and hoping, longing for the memory of Sir Henry to set the crowd alight. There has been a close call with Tiger Cliff, but as the days went on, I started to resist the siren song. Dick Francis once wrote: ‘There are no fairy tales in racing.’ I bashed down the fired expectations.

But as the off grew closer, even as Winsili wavered and then hardened as the favourite, I decided that my lovely Riposte would give the best riposte of all. I threw last-minute cash at her, in the way I often do, as if the horse herself would detect my lack of loyalty if I ratted.

I did not say any of this out loud. I did not want to raise my mother’s hopes. I said, diffidently: ‘I quite like the look of this Riposte.’ And that was all.

As the stalls smacked open and Simon Holt began his call, Riposte imitated her close relation Frankel in his last start on this very course.

She fell out, completely missing the break. Oh, well, I thought, privately, that’s that. It’s very difficult to remedy that lost start. Tom Queally had to roust her along without setting her alight. For a moment, as he pushed her into the race, it looked as if she might boil over. But then the good girl came back to herself and settled into her running. She was still on the outside, towards the back, but she had found her rhythm.

At half way, she had settled and was running well within herself. But there were still only two horses behind her. Then Queally, cleverly, patiently, started to creep into the race, his sympathetic hands nursing his girl along.

And then, at about two out, he did something radical, even rash. He gave Riposte a great push, asking for a huge burst of speed. Again like her illustrious relation, she put on her sprinting shoes, passed five horses in a matter of seconds, and hit the front. In a flash, she was out on her own; nothing in front of her but a wide, searching sward of green.

Would she last up that testing incline? Would that intense effort have taken too much out of her? Would she get lonely out in front, all on her own?

All these questions muddled through my mind. But the lovely filly had every answer. She never deviated, running straight and true to the line under only hands and heels, spread-eagling her field.

Without at all meaning to, I burst into tears. I do this in big races in which I am absurdly emotionally invested. I did it for Desert Orchid, all those years ago, when he defied a mud-splattered afternoon and fought his way up the murderous Cheltenham hill, running on fumes and guts and glory. I did it for Kauto Star’s great comeback at Haydock on that dour autumn day, when everyone said he was finished. I did it for Frankel at York, when people were not quite sure if the wonder colt would see out the mile and two.

It is what my old Irish godmother describes, vividly, as ‘tears coming out at right angles’. I don’t think I’d realised until that moment how much I had put into this good filly, how the memories of Sir Henry rode on her honest back, how the thought of that grieving team at Warren Place had infected my racing spirit.

Normally, when a jockey passes the post in front at the Royal Meeting, there is the instant flashing smile of victory. It is the dream of every rider on the flat to win here. But Tom Queally did not smile.

He did that thing with his mouth that you do when you are fighting tears. The muscles tightened and the corners turned down and the face set. He is not a man of public emotion. One sensed that if he had been alone he would have cried like a baby. As it was, he was fighting to hold it together on this most public of stages.

He just put his hand out, and ran it over Riposte’s ear, with the exact gentle touch that Sir Henry had for his fillies. As the camera angle shifted, the jockey’s back was slumped and head bowed, as if in defeat.

The microphone was stuck in his face, and he said, on a long breath: ‘It’s been a tough, tough week, and I know a lot of people are struggling. But it’s great she did as well as she did and I’m sure Henry’s looking down and helping us.’

Queally had that raw, disbelieving look on his face that I remember so well from when my father died. The lovely victory must have brought it all back for him. Sir Henry’s death was not a surprise; he had been ill for years. But with men like that, impossible thinking sets in. You believe they will defy the docs and live forever. I had a message from someone who lives in Newmarket only today, saying she still could not believe that she would walk down the street and not see him. Men like that are institutions, stitched into the life of the place they embody. Death seems stupid and impossible.

The camera pulled back to show the stalwart travelling head lad, his face bleak as granite. The young lass, leading in her conquering heroine, was unable to keep up the facade and dissolved into open tears.

Then came the most poignant moment of all. Lady Cecil, who has taken over the licence from her late husband, rushed forward in the winner’s enclosure, going straight for Queally. The two hugged, and in that hard embrace you could see all the tension that comes with great loss. There must have been so many moments on the Heath when it was the three of them, so many breakfasts, so many post-mortems, of triumph or disappointment. There is a thing, when you lose someone, of wanting the person who understands the most. In that winner’s circle, at Ascot, with the colours of Prince Khalid Abdullah shining like a beacon just as they had in Frankel’s last, mighty victory, I think that for Lady Cecil, Tom Queally understood the most.

At this stage, Lady Cecil’s face had the raw, undefended look of someone who has suffered tearing loss. But she was in front of the world. She had to step up to the microphone. Clare Balding, with every inch of her sensitivity and professionalism, conducted what must have been one of the hardest interviews of her career. She knew all these people; she had grown up with them; there was no disinterested distance for her. But she was on national television; she had to ask the questions.

Looking back on it now, I am amazed that Lady Cecil did not just walk away. Connections who have nothing like her excuse have; I’ve watched famous owners ruthlessly snub post-race interviewers. And yet, in one of the most graceful acts I have seen on a racecourse, she generously offered herself, in all her loss, squaring her shoulders and lifting her face up in its naked emotion.

She looked up to the sky, gathered a faltering smile, and said: ‘First of all, that was for Henry.’

There was a terrible pause.

‘For the Prince, and for all the staff at Warren Place.’

Then she rallied. ‘I don’t really have the words to say what I am feeling.’

Bugger everything, I thought; there are no words. And yet this tremendous woman kept on. ‘He was just adored, by so many people. I mean, people who’ve never met him, just loved him. And...’ She shook her head, running out of words. ‘What can I say?’

Another sympathetic question from Balding; another brave answer.

‘We hardly dared dream that we would have a winner. I just thought, God he would have been relishing this. Everyone knows how he loves Ascot.’

And there it was, the present tense. The most revealing, moving moment of all; the marker that the master of Warren Place is not yet gone in the minds and hearts of those who loved him.

And then she tailed off, and Clare Balding moved in to rescue her. ‘You need say nothing more, you’ve been so brave, so strong. Well done.’

But Lady Cecil was not finished. Like her lovely, fighting filly, she took another run at it. ‘Keeping busy, is what’s keeping us all going. If we had nothing to do, I think we’d all fall to bits.’

Clare Balding, the seasoned pro, faltered herself, in the midst of that boiling cauldron of emotion. Suddenly hardly able to get her own words out, she said, almost in a whisper: ‘It’s the best result of all.’

And the sweetest thing was that the cameras then cut to Riposte, being led away, her intelligent ears pricked, her kind eye gleaming and bright, her head held high. The good ones, the competitive ones, tend to know when they have won. Tom Queally said once of Frankel that as the colt seasoned and grew in stature, he began to understand that the noise and acclamation which should really alarm a flight animal was in fact a homage. ‘He soaked it all up; he knew it was for him,’ Queally said after York.

Riposte is not in that legendary category. She is a nice filly, with a lovely talent and a willing attitude; she may rise to some heights, but perhaps she will not go down in history like her imperious relation. But all the same, in that moment, she had a little look of eagles in her fine eye.

There were many things for which Sir Henry Cecil was famous. One of them was being good with fillies. Wining the Oaks eight times was not a fluke. Bizarrely, there is sexism in the horse world just as there is in the human. People talk of fillies and mares being difficult, unpredictable, hormonal. Mare-ish is a horrid, lazy insult, casually hurled. But I think what Henry Cecil knew is what anyone who has loved and worked with a female equine carries in their heart. If you are gentle and kind and patient with a filly, she will give you everything, every last inch of loyalty and trust and fighting spirit. So it was intensely appropriate that in this dramatic week, in this Royal Meeting which started with a minute of silence for its native son, it was one of his girls who came good for the old fellow.

At which point, there was the rushing realisation that this was not yet the end of the drama of this extraordinary day. The very next race was the Gold Cup, the showpiece of the week. In some ways, it is a ridiculous race. It is two and a half miles, which is a distance some jumpers struggle to manage. Most flat horses are simply not bred to run this far. There was a huge field, although, because of the fast ground, runners were dropping like flies. The promising High Jinx was out; Dermot Weld decided he could not risk the delicate legs of Rite of Passage. At the top of the market, driven there by a combination of sentiment and hope, was the little bay filly, Estimate.

Estimate belongs to the Queen. Last June, I was there to watch her win the Queen’s Vase, to extravagant emotion, in the jubilee year. I fell in love with her then and I have followed her ever since. She is a lightly-built filly; she does not look like a mighty stayer. But she has a dreamy temperament and the will to win, and she is improving all the time.

Still, on paper, she had something to find. The trip was four whole furlongs into the unknown; on strict official ratings, she was well down the field of fourteen. She would have to produce a rampant career best.

As I had with Riposte, I resisted my stupid soft heart, and tried to find the rivals who would bring her low. Simenon was the danger, I decided, with proven form at course and distance, and the wizard that is Willie Mullins in charge.

But again, as the start neared, I gave in to the heart, and bashed all my money on the little mare. Yes, she was up against the boys; yes, it was a fairy tale too far; yes, she had something to find on the book. But blast it, I wanted her more than anything, and if anything could find that little bit extra for the big occasion, she could.

She is such a kind and genuine horse. Channel Four showed a clip of her in her stable, and she was as dopey and dreamy and affectionate as a dear old donkey, nuzzling up to her lass, making silly faces, soaking up the love of her faithful companion. It’s not often you see a top-class racehorse do that, and it made me fall more in love with her than ever. Bugger the book I thought; this is my girl.

And I switch into the present tense, because it feels in my head like it is happening all over again.

As Estimate goes round the paddock, with her owner watching intently, she impresses with her big race temperament. On a warm day, there is not a hint of white sweat on her bay flanks. Then, suddenly, without in any way becoming flighty or over-wrought, she gives two little bucks. They are balanced perfectly on the fulcrum of exuberance and determination. They sketch an arching parabola of intent. My mother and I look at each other, hope rising in our eyes.

‘She’s ready,’ we say. ‘Oh yes. She is ready.’

The late cash comes pouring in, who knows from where. The seasoned paddock watchers, the sentimental royalists. Estimate shortens into 7-2, veering violently from sixes this morning. I add my cash to the party. I’ve loved this horse for a long time; I damned if I am going to let my old loyalties lapse. I can see all the doubts for what they are. But my money must be where my mouth is.

Estimate comes out onto the course, on her own. She canters down to the start with her head high and her ears pricked, collected and balanced, looking around her as if taking in every inch of the fine spectacle. She has a little white snip on her dear nose, and in my fevered mind, it starts to blaze like a flashing sign.

And, they are off.

The sultry summer’s day turns misty, and through a sudden murk, Estimate’s snip shows brightly. She takes up a good position, one off the rail, four lengths off the pace. Ryan Moore, a jockey who is currently riding out of his skin, lets her down and gets her beautifully settled, so her natural rhythm can assert itself. Her long, narrow ears go back and forth in time with her hoofbeats.

Past the packed stands they go. The faint sounds of whistles and applause can be heard, before they are off again into the country, where the race will begin to unfold.

The massive white-faced German raider is running strongly in front, tracked by the two staying stars, Colour Vision and Saddler’s Rock. Estimate is tidily tucked in behind. Into Swinley Bottom, she is perhaps the most well-balanced of the entire field, happy in her running.

Four out, the field bunches up. ‘There is Estimate,’ says Simon Holt, his voice rising, ‘with every chance.’

Jockeys are starting to crouch lower now, not yet kicking on, but indicating an increased momentum. Ryan Moore is rocking Estimate gently into a quicker rhythm. Colour Vision, who won this last year but has been disastrously out of form ever since, is suddenly full of running. The brilliant Johnny Murtagh is releasing Saddler’s Rock. Simenon is suddenly unleashing a withering run down the outside. In the midst of this, in a small pocket of her own, Estimate is quietly running her race.

And then Moore asks the question, after over two miles of searching turf, and Estimate answers. The answer is: Yes.

She surges forwards, chasing the mighty grey in the Godolphin colours. She gets past him, inch by inch, but the race is not done. Two big fellas come charging at her, down the outside; the Irish Simenon, the French Top Trip.

All three horses are now in full cry. They are so close together you could not put a cigarette paper between them. For a horrible moment, I think that the filly will be swallowed up by the roaring colts.

At home, in our house, with the blue Scottish hills visible though the window and the bluebirds questing at the window, everything erupts. The Younger Brother and I are on our feet, bawling at the tops of our voices. My old mum, who has seen Nijinsky and Mill Reef and the Brigadier, is shouting: ‘COME ON RYAN’. Stanley the Dog, who clearly believes we have suffered some kind of catastrophic event, is howling and jumping and barking his head off. Only the sensible Stepfather is sitting quietly, riveted to the action, a small oasis of calm in the storm.

I look away, unable to watch, convinced the brave filly is beat. It’s too much to ask; it’s too much to hope. She’s never been anywhere near this distance before; only the very best fillies are capable of beating the colts. She’ll fade, fold up, be done on the line.

But I turn back, and there she is, with her little head stuck out, her glorious stride lengthening not shortening, every atom in her body speaking of her will to win. I gather one last stupid howl of hope. GO ON GO ON GO ON, I shout, ignoring the family, ignoring the leaping dog, ignoring everything except the fierce battle of those last, terrifying strides.

Simenon’s determined head comes up to Estimate’s shoulder, the great momentum of his powerful quarters pushing him forward. Will the bloody finishing post ever come?

But then, with no dramatics at all, the good filly just keeps going, and there is the line, and she has a precious neck in hand, and Ryan Moore is crouched up almost at her ears, carrying her over the finish.

‘I CAN’T BELIEVE IT,’ I shout.

As if my entire family is deaf, I yell again: ‘I CAN’T BELIEVE IT.’

We hug, we jump in the air, we weep idiot tears of joy.

It’s just a horse. It’s just an old lady in a lilac dress. It’s just a race.

On any rational level, it is hard to know which is more absurd: the racing of horses or the hereditary monarchy. But humans are not rational animals. Even in the most empirical of us, the magical thinking sometimes overwhelms. I can’t help it: I love the Queen. I love her for her dignity and restraint and good old British stoicism. I love Estimate, for her sweetness and strength and bloody-minded determination not to give up. I swear she had a Fuck You Boys look in her eye as she flashed past the post. And I love racing, where these beautiful herd animals may show all their mighty, fighting qualities.

And so I shouted and cried and leapt in the air, even though I am forty-six years old and I should know better.

The filly came in, the Queen walked down to greet her, the crowd went insane. People did not know what to do with themselves. The little golden cup was presented, and the Queen, who really has been around the block more than most, who has been coming to Ascot since the fifties, who knows all about the dreams of horses not quite coming true, stared at it as if she had never seen it before. She looked as delighted and disbelieving as a child.

And that, my darlings, was Ladies’ Day at Ascot, when four tremendous females, two equine and two human, wrote a story that will stay stitched into the memory of everyone lucky enough to have witnessed it.

June 20, 2013

Bonus post: I pay homage to Estimate. Or, memories of the Queen’s Vase.

You will know by now that the scriptwriters threw away caution and probability, and wrote the fairy tale.

Estimate won the Gold Cup for the Queen: a brave little filly sticking her neck out to see off the big boys. I’ll write about it tomorrow at extravagant length, because it was one of the best things I’ve ever seen in racing. Sometimes I have to resort to cliché, because only cliché will do: there was not a dry eye in the house.

In honour of the great moment, I’m putting up the post that I wrote during this week last year, when Estimate won the Queen’s Vase.

I remember vividly going down to see her in the pre-parade ring, and fearing for her; she was so slight and mere compared to the great, muscled colts that she was up against. She’s grown bigger and stronger with age, but she is still a delicate-looking sort of lady, and today she had a packed field and a doughty set of stayers taking her on. But whilst she may not be physically huge, what she does have is a bottomless, never-say-die, mighty racing heart.

This is what I wrote, one year ago:

In the Queen's Vase, the Queen herself had a nice filly called Estimate. She'd won well at Salisbury last time out but this was a big step up in class and trip. She went off favourite, mostly I think because of sentimental Jubilee year bets. I had thought she might have the right stuff, but then I saw her in the ring, and she was a small mare, narrow in the neck, with a sweet but plain face. It was two miles, and the other horses looked so big and muscled and powerful by comparison.

And, I thought, it really would be too good to be true, on this Diamond Jubilee.

The ordinary little brown mare galloped to the front and did not stop and won as she liked. The crowd went mad. Posh gentlemen took their hats off and waved them in the air as if they were at a football match.

I rushed to the winner's enclosure. There was Estimate, suddenly looking rather beautiful, flushed with her great victory. 'Where is she? Is she there?' said people in the crowd, looking around for the Queen. Would her Majesty descend from the Royal box? Yes, she would. There she was, walking across the grass, and cheers and whoops and roars rang out.

Suddenly, everyone realised it was the Queen's Vase, which meant the cup would be presented by a member of the royal family. 'I suppose she can't really present it to herself,' said the lady next to me, laughing happily. 'Your Majesty, here is your cup, well done. Oh, thank you Your Majesty.' Everyone was very excited by this stage. The Queen, serene in lilac, was smiling all over her face, and giving Estimate a regal pat.

Then, the ramrod nautical figure of Prince Philip appeared, and picked up the trophy, and gave it to his wife. I know it's silly to get soft about the Queen, but I am quite silly, and I have to say I had a tear in my eye. There was something so touching about the two old people and the young filly and the cup and the delirious crowd. The lady next to me was wiping her eyes.

My mother, when I rang an hour later, was still misty with emotion. 'You know,' I said, 'there really was nothing to her, that filly, but she ran like a titan.'

'Oh, she was glorious,' said my mother.

'But then,' I said, 'it's sometimes the way with those great mares. Dunfermline wasn't much to look at; Quevega is just an ordinary brown mare.'

'Yes,' said my mother. 'Sometimes, if they look too much like flashy colts, they are not much good.'

I told her the story of the Queen and the crowd in the winning enclosure, and the whoops and the cheers and the clapping.

I walked away with a big fat smile on my face, even though I had not a penny on that filly. I probably should be a grouchy old republican, but I can't help it, I love the Queen. Her untrammelled delight when her brave little horse won her that shiny cup really was one of the sweetest things I've seen in racing.

So, it was a great day.

A great day indeed. And now we have had another to match it.