Tania Kindersley's Blog, page 2

January 4, 2020

Gratitude: Day Four.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 17.0px} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

I’m grateful today for patience and belief.

Just over a year ago, I took on the training of a Connemara mare for my great-niece. The sweet pony was christened Clova and we all adored her from the moment she arrived and she was so dear that I thought I’d be able to get her soft and relaxed and happy in a heartbeat.

It didn’t turn out like that. She’d had a lot of different homes, as ponies often do, and the move to us seemed to be a bridge too far for her. It was as if she’d given her trust to humans one too many times, and just as she was starting to feel settled, the horsebox would arrive and she’d have to move on. So she had, entirely logically, decided to defend herself from and brace herself against the world. She wouldn’t even entirely trust that my mighty red mare, the most devoted protector of the herd, would look after her.

So we had many, many steps backwards. There were times when I thought I’d over-faced myself, and that I would never find the key. I felt a keen responsibility to the very youthful human who was going to ride the little mare, and I was terrified I was going to let her down. (The small human, who has the heart of a lion, was never worried. She had, from the start, more faith in me and more faith in her pony than either of us had in ourselves.)

I plugged on through the doubts, trying this, trying that, asking for help, desperately attempting to build belief. And in the end, with a lot of encouragement and advice, I found it. The pony found it. Patience and time and not giving up paid off. This morning, the youthful jockey and her sweet mare galloped up a Scottish hill as if they could fly.

We’ve still got a way to go. Clova can still have her doubts. Her confidence can wobble and she can become slightly overwhelmed. But I think she knows that we are her people now, and this is her home, and the good herd is her herd. And that is a beautiful foundation stone on which to build.

Patience and belief. These are two of the singing virtues that my horses teach me every day. And the mares do have to teach me every day, because I can waver and wobble and forget. So I am grateful to them too.

And I’m grateful to the enchanting children who come and play with the horses, who amuse Clova and remind her that life can be fun, who make the field a place of laughter and merriment and adventure. These young horsewomen are natural believers, and they teach me something every day too.

Belief is hard, I think. It’s too easy to lose faith. You have to push yourself into believing, into keeping hope alive. But what I have found is that if something is worth it - if it’s a heart thing and a soul thing and spirit thing - then I will keep on pushing, however much of a flake and a failure I sometimes feel. That’s why horses are such inspiring teachers. You have to do it for them. They need you to be brave, and because they don’t speak English or have the prefrontal cortex for complex ideas, you can’t explain to them why you think you don’t have it in you.

I think children are a little the same. They have the same straightforward authenticity. I can’t let the young ones down, just because I’m feeling a little bashed and bruised and frayed around the edges. So I dig down and scrape up the last remnants of belief and put my faith together with cussedness and binder twine.

And then - then - we are all galloping up that literal and metaphorical hill, as if nothing in the world can stop us.

I’m grateful today for patience and belief.

Just over a year ago, I took on the training of a Connemara mare for my great-niece. The sweet pony was christened Clova and we all adored her from the moment she arrived and she was so dear that I thought I’d be able to get her soft and relaxed and happy in a heartbeat.

It didn’t turn out like that. She’d had a lot of different homes, as ponies often do, and the move to us seemed to be a bridge too far for her. It was as if she’d given her trust to humans one too many times, and just as she was starting to feel settled, the horsebox would arrive and she’d have to move on. So she had, entirely logically, decided to defend herself from and brace herself against the world. She wouldn’t even entirely trust that my mighty red mare, the most devoted protector of the herd, would look after her.

So we had many, many steps backwards. There were times when I thought I’d over-faced myself, and that I would never find the key. I felt a keen responsibility to the very youthful human who was going to ride the little mare, and I was terrified I was going to let her down. (The small human, who has the heart of a lion, was never worried. She had, from the start, more faith in me and more faith in her pony than either of us had in ourselves.)

I plugged on through the doubts, trying this, trying that, asking for help, desperately attempting to build belief. And in the end, with a lot of encouragement and advice, I found it. The pony found it. Patience and time and not giving up paid off. This morning, the youthful jockey and her sweet mare galloped up a Scottish hill as if they could fly.

We’ve still got a way to go. Clova can still have her doubts. Her confidence can wobble and she can become slightly overwhelmed. But I think she knows that we are her people now, and this is her home, and the good herd is her herd. And that is a beautiful foundation stone on which to build.

Patience and belief. These are two of the singing virtues that my horses teach me every day. And the mares do have to teach me every day, because I can waver and wobble and forget. So I am grateful to them too.

And I’m grateful to the enchanting children who come and play with the horses, who amuse Clova and remind her that life can be fun, who make the field a place of laughter and merriment and adventure. These young horsewomen are natural believers, and they teach me something every day too.

Belief is hard, I think. It’s too easy to lose faith. You have to push yourself into believing, into keeping hope alive. But what I have found is that if something is worth it - if it’s a heart thing and a soul thing and spirit thing - then I will keep on pushing, however much of a flake and a failure I sometimes feel. That’s why horses are such inspiring teachers. You have to do it for them. They need you to be brave, and because they don’t speak English or have the prefrontal cortex for complex ideas, you can’t explain to them why you think you don’t have it in you.

I think children are a little the same. They have the same straightforward authenticity. I can’t let the young ones down, just because I’m feeling a little bashed and bruised and frayed around the edges. So I dig down and scrape up the last remnants of belief and put my faith together with cussedness and binder twine.

And then - then - we are all galloping up that literal and metaphorical hill, as if nothing in the world can stop us.

Published on January 04, 2020 11:33

January 3, 2020

Gratitude: Day Three.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 17.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Today, I am grateful for the weather.

The British famously talk about the weather. Even though I know this is the most terrible cliché of Britishness, like queuing, saying sorry, and enjoying a nice cup of tea, I still do it. I do it at the garage and in the post office and in the shop. Everyone in the village does it. Quite often, they will refer to some mysterious authority.

‘They say snow is coming in.’

‘They say it’s going to get bitter next week.’

‘They say that February will be bad.’

The ‘they’ is never specified. I often imagine it is some old farmer, a sort of ancient mariner type, who can simply look up at the sky and sniff the wind and know whether it will be sleet or gales.

We also talk a lot in my neighbourhood about our own curious little micro-climate. Our weather forecasts are often dramatically wrong. We regularly have the highest or lowest, wettest or driest. (This actually is probably confirmation bias. I don’t notice when Kidderminster or Ashby-de-la-Zouch is the hottest or wettest, but I feel oddly proud and pay close attention when my village gets the prize.) Famously, when it is pouring with rain down the valley in Aberdeen, or when the entire seafront is blanketed in haar, the sun shines brightly on our little village.

The great irony is that the British always talk about the weather but we don’t really have weather. We don’t have three year droughts or tornado seasons. We don’t have dust storms or ice storms or bitter blizzards which last for days. We tend to grumble if the mercury tips over thirty degrees in the height of summer, and if a little snow falls on London, half the public transport grinds to a halt.

And the reason I am grateful for that today is that the plight of Australia is at the forefront of the national consciousness. A whole country is burning, and it’s almost beyond imagination. I read stories about people sheltering on the beach with their horses and dogs, of a man who went to help a neighbour save his house, only to come back to find his own burnt to the ground, of city-dwellers unable to breathe. I’ve talked to Australians who are in mourning for a whole nation, who fear their beloved land will never be the same again. My heart aches and breaks for them.

And even as I remind myself to be grateful, I go down to the horses and hear myself say, ‘Oh, this wind is bitter.’ A little bit of bitter wind! That is the worst of my weather problems.

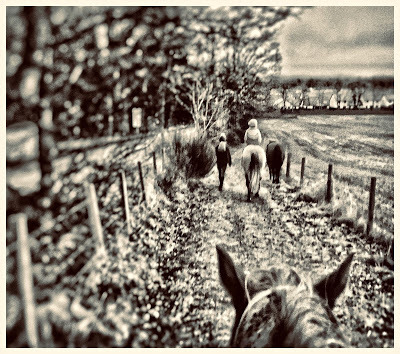

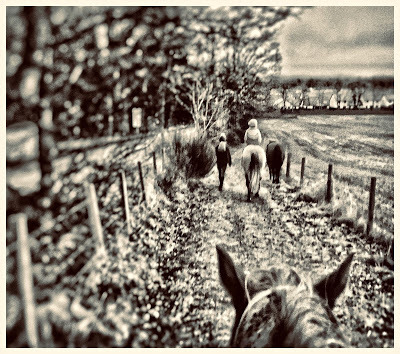

But there was no rain or sleet or snow, so my posse of young horsewomen and I took the mares up the hill. The sky was clear and singing with colour and the hills were indigo in the afternoon light. It’s the funeral today of a dear friend, five hundred miles away in the south. I could not go, so I cantered my red mare up to the top of the hill and I said my own goodbye. These hills are my cathedral, and I’ve committed many spirits to them, when I could not go to the formal service. I did it for my godfather, and a young cousin who died in a pointless accident, and an old cousin who went full of years. I did it for my mum, who refused to have a funeral, so I gave her one of my own. I rode the mare and sang a song and recited some Yeats. It was one of the greatest funerals I ever went to.

And on all of those days, on all of those sad farewells, the weather was kind. The sun shone and the mountains were bright with majesty. There was peace and stillness, so the souls could fly to the heights.

So my gratitude today is to this dear old temperate climate, which never throws too much at us. It’s easy to forget how lucky you are until you see what other people have to face. I’ve never been to Australia, but my heart is there today.

Today, I am grateful for the weather.

The British famously talk about the weather. Even though I know this is the most terrible cliché of Britishness, like queuing, saying sorry, and enjoying a nice cup of tea, I still do it. I do it at the garage and in the post office and in the shop. Everyone in the village does it. Quite often, they will refer to some mysterious authority.

‘They say snow is coming in.’

‘They say it’s going to get bitter next week.’

‘They say that February will be bad.’

The ‘they’ is never specified. I often imagine it is some old farmer, a sort of ancient mariner type, who can simply look up at the sky and sniff the wind and know whether it will be sleet or gales.

We also talk a lot in my neighbourhood about our own curious little micro-climate. Our weather forecasts are often dramatically wrong. We regularly have the highest or lowest, wettest or driest. (This actually is probably confirmation bias. I don’t notice when Kidderminster or Ashby-de-la-Zouch is the hottest or wettest, but I feel oddly proud and pay close attention when my village gets the prize.) Famously, when it is pouring with rain down the valley in Aberdeen, or when the entire seafront is blanketed in haar, the sun shines brightly on our little village.

The great irony is that the British always talk about the weather but we don’t really have weather. We don’t have three year droughts or tornado seasons. We don’t have dust storms or ice storms or bitter blizzards which last for days. We tend to grumble if the mercury tips over thirty degrees in the height of summer, and if a little snow falls on London, half the public transport grinds to a halt.

And the reason I am grateful for that today is that the plight of Australia is at the forefront of the national consciousness. A whole country is burning, and it’s almost beyond imagination. I read stories about people sheltering on the beach with their horses and dogs, of a man who went to help a neighbour save his house, only to come back to find his own burnt to the ground, of city-dwellers unable to breathe. I’ve talked to Australians who are in mourning for a whole nation, who fear their beloved land will never be the same again. My heart aches and breaks for them.

And even as I remind myself to be grateful, I go down to the horses and hear myself say, ‘Oh, this wind is bitter.’ A little bit of bitter wind! That is the worst of my weather problems.

But there was no rain or sleet or snow, so my posse of young horsewomen and I took the mares up the hill. The sky was clear and singing with colour and the hills were indigo in the afternoon light. It’s the funeral today of a dear friend, five hundred miles away in the south. I could not go, so I cantered my red mare up to the top of the hill and I said my own goodbye. These hills are my cathedral, and I’ve committed many spirits to them, when I could not go to the formal service. I did it for my godfather, and a young cousin who died in a pointless accident, and an old cousin who went full of years. I did it for my mum, who refused to have a funeral, so I gave her one of my own. I rode the mare and sang a song and recited some Yeats. It was one of the greatest funerals I ever went to.

And on all of those days, on all of those sad farewells, the weather was kind. The sun shone and the mountains were bright with majesty. There was peace and stillness, so the souls could fly to the heights.

So my gratitude today is to this dear old temperate climate, which never throws too much at us. It’s easy to forget how lucky you are until you see what other people have to face. I’ve never been to Australia, but my heart is there today.

Published on January 03, 2020 08:53

January 2, 2020

Gratitude: Day Two

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 17.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Today, I was profoundly grateful for the internet.

I had been asked to do a podcast with my friend Jane Pike on creativity. I’m a bit late to the podcast party, but I’ve been catching up like mad. I love the whole idea, and I love the amazing variety, and I love that funny and fascinating people can put their thoughts out into the world. So being asked to do one was rather thrilling. That the invitation should come from Jane was especially delightful.

Jane works as a mental coach for riders and horse people in general. She’d observed that what was holding a lot of people back with their horses was not lack of technical skill, but the blocks in the human mind. (It’s all the usual suspects - fear, shame, terror of being judged, the committee in the head which tells you that you will never be good enough.) So she started a programme where people could work on those brutal mental blocks. I adore her wisdom and generosity and good-heartedness, and I find that her teaching helps me as much with life as it does with horses.

And this evening, even though she lives in New Zealand and I live in Scotland, we were chatting merrily away about creativity and imagination and authenticity and courage and letting your inner three-year-old come out to play. All through the miracle of the internet.

The truly wonderful thing is that we have never met in life, but I think of her as my friend. We communicate a lot through FaceTime and messages and the general back and forth which the internet makes possible. If it were not for this astounding technology, she would be on her side of the world and I would be on mine, and we would never know the other even existed. The thought of not having her brilliant mind and her rebel sense of humour in my life makes me sad. But I don’t have to be sad, because there she is, on the other end of a line that travels over thousands of miles of ocean and time and space. That is something to be grateful for.

I’m also grateful to my red mare. I’m always grateful to my red mare, because she is so beautiful and comical and interesting and fine, and because she teaches me something every day. Today, though, I’m grateful to her for a very specific reason. Because of her, I have made connections with human beings I would otherwise never have met. This is true in my real life, and it is true in my internet life. She’s been like a little heart connector, busy introducing me to new people and new ideas and new groups. It was because I needed to be a better person for her that I sought out Jane. It is because of her that strangers have become friends.

The older I get, the more I think that connection and love are everything. And because this grand thoroughbred canters about the internet - she has her own Facebook page, as she is too marvellous to be confined to a small Scottish community - she connects me with minds and hearts all over the world. That really is something quite extraordinary. And I am more grateful than I can say.

Today, I was profoundly grateful for the internet.

I had been asked to do a podcast with my friend Jane Pike on creativity. I’m a bit late to the podcast party, but I’ve been catching up like mad. I love the whole idea, and I love the amazing variety, and I love that funny and fascinating people can put their thoughts out into the world. So being asked to do one was rather thrilling. That the invitation should come from Jane was especially delightful.

Jane works as a mental coach for riders and horse people in general. She’d observed that what was holding a lot of people back with their horses was not lack of technical skill, but the blocks in the human mind. (It’s all the usual suspects - fear, shame, terror of being judged, the committee in the head which tells you that you will never be good enough.) So she started a programme where people could work on those brutal mental blocks. I adore her wisdom and generosity and good-heartedness, and I find that her teaching helps me as much with life as it does with horses.

And this evening, even though she lives in New Zealand and I live in Scotland, we were chatting merrily away about creativity and imagination and authenticity and courage and letting your inner three-year-old come out to play. All through the miracle of the internet.

The truly wonderful thing is that we have never met in life, but I think of her as my friend. We communicate a lot through FaceTime and messages and the general back and forth which the internet makes possible. If it were not for this astounding technology, she would be on her side of the world and I would be on mine, and we would never know the other even existed. The thought of not having her brilliant mind and her rebel sense of humour in my life makes me sad. But I don’t have to be sad, because there she is, on the other end of a line that travels over thousands of miles of ocean and time and space. That is something to be grateful for.

I’m also grateful to my red mare. I’m always grateful to my red mare, because she is so beautiful and comical and interesting and fine, and because she teaches me something every day. Today, though, I’m grateful to her for a very specific reason. Because of her, I have made connections with human beings I would otherwise never have met. This is true in my real life, and it is true in my internet life. She’s been like a little heart connector, busy introducing me to new people and new ideas and new groups. It was because I needed to be a better person for her that I sought out Jane. It is because of her that strangers have become friends.

The older I get, the more I think that connection and love are everything. And because this grand thoroughbred canters about the internet - she has her own Facebook page, as she is too marvellous to be confined to a small Scottish community - she connects me with minds and hearts all over the world. That really is something quite extraordinary. And I am more grateful than I can say.

Published on January 02, 2020 13:27

January 1, 2020

Gratitude: Day One

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 17.0px} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Cochin; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

I’m absolutely hopeless at New Year’s resolutions. I have a cussed streak which makes me kick against anything obligatory or mandated. But this year, I would like to make a change. I’m conscious that I have so much good fortune in life, and I don’t want to fritter that away with pointless worries and thoughtless frets and negative thinking. I like to think that I’m a roaring optimist, and so, in some ways, I am, but I am keenly aware that I have a fatal tendency to run doomsday scenarios in my head. So I spend lunatic amounts of energy worrying about things which have not happened and which might never happen.

I’ve been reading a lot about gratitude over the last few years. I understand its power and I understand that it is a discipline which can change your life. Yet I never quite practise it. I throw a sop here and there to the gratitude gods, but I don’t devote myself to their service. And I think I would like to.

I’m rather cautious about doing this on the blog, because I fear it may get frantically dull. I really am grateful, almost every day, for my fingers and toes. Especially my fingers. They are typing these words now, at seventy words a minute. Imagine that. They really are my life and my livelihood. I think I might be grateful to them every day. There may come a moment when you wish I would shut up about my damn fingers.

There will be other regular loves. I love my opposable thumbs. I’m idiotically grateful that I have legs which can walk. They carried me down to the field this afternoon, where I stood with my mares and breathed in their peace and life in the gloaming. I looked up at the new moon, and I was grateful for the moon, and the sky, and Scotland, and the stillness, and the beauty, and the fact that I don’t live in a noisy city.

I was grateful for my eyes, which allowed me to look at the beauty. And come to think of it, I am grateful for the people who invented spectacles and the people who make spectacles, so that I can see the beauty in clear focus.

I was grateful for my funny lurchers, bounding about with merriment and joy. Even though one of them ate a whole camembert this morning. I was looking forward to that nice bit of cheese. But it is only a bit of cheese.

I’m grateful that I can sit in my quiet room with heat and light. I think I might be writing that sentence quite a lot in the next year.

I’m grateful that there are kind people on social media and that there is racing on the telly and that there is good in the world. I’m grateful that there are dedicated humans out there who have rescued the Duke of Burgundy butterfly from extinction. I didn’t even know there was such a butterfly until today, and I did not know that it was in mortal peril. And now I know that thousands of devoted souls have worked to save it. That really is something.

I’m grateful for my mind. I’d like to expand it this year. I’ve got an idea that I should try and learn something new every day. I’m not sure whether this will be possible, but I’ll give it a go. Today, I learnt about the butterfly and its saviours. (Yesterday, I learnt that some horses are prone to holding their breath, and that you can get them to relax and breathe by using the canter. That is a rather niche fact, but it is the kind of thing that gives me pleasure.)

Perhaps the new thing every day might stop the gratitude list from growing stale and dull, but I still think there may be rather a lot of repetition. Because of this, I’m going to start it quietly. The blog had rather gone into hibernation anyway, and I’m not sure how many people come here any more. So I feel that I can write things here which are almost private. I need the discipline of publishing, but I don’t want to be stymied by the terror of boring an audience into losing the will to live.

So, if you are reading this, it will be our secret. Who knows? It might be more fascinating than I think. I’ll obviously try not to be a crashing bore, but I can’t make any guarantees. And if you are kindly accepting that risk, then I am grateful for your forbearance.

I’m absolutely hopeless at New Year’s resolutions. I have a cussed streak which makes me kick against anything obligatory or mandated. But this year, I would like to make a change. I’m conscious that I have so much good fortune in life, and I don’t want to fritter that away with pointless worries and thoughtless frets and negative thinking. I like to think that I’m a roaring optimist, and so, in some ways, I am, but I am keenly aware that I have a fatal tendency to run doomsday scenarios in my head. So I spend lunatic amounts of energy worrying about things which have not happened and which might never happen.

I’ve been reading a lot about gratitude over the last few years. I understand its power and I understand that it is a discipline which can change your life. Yet I never quite practise it. I throw a sop here and there to the gratitude gods, but I don’t devote myself to their service. And I think I would like to.

I’m rather cautious about doing this on the blog, because I fear it may get frantically dull. I really am grateful, almost every day, for my fingers and toes. Especially my fingers. They are typing these words now, at seventy words a minute. Imagine that. They really are my life and my livelihood. I think I might be grateful to them every day. There may come a moment when you wish I would shut up about my damn fingers.

There will be other regular loves. I love my opposable thumbs. I’m idiotically grateful that I have legs which can walk. They carried me down to the field this afternoon, where I stood with my mares and breathed in their peace and life in the gloaming. I looked up at the new moon, and I was grateful for the moon, and the sky, and Scotland, and the stillness, and the beauty, and the fact that I don’t live in a noisy city.

I was grateful for my eyes, which allowed me to look at the beauty. And come to think of it, I am grateful for the people who invented spectacles and the people who make spectacles, so that I can see the beauty in clear focus.

I was grateful for my funny lurchers, bounding about with merriment and joy. Even though one of them ate a whole camembert this morning. I was looking forward to that nice bit of cheese. But it is only a bit of cheese.

I’m grateful that I can sit in my quiet room with heat and light. I think I might be writing that sentence quite a lot in the next year.

I’m grateful that there are kind people on social media and that there is racing on the telly and that there is good in the world. I’m grateful that there are dedicated humans out there who have rescued the Duke of Burgundy butterfly from extinction. I didn’t even know there was such a butterfly until today, and I did not know that it was in mortal peril. And now I know that thousands of devoted souls have worked to save it. That really is something.

I’m grateful for my mind. I’d like to expand it this year. I’ve got an idea that I should try and learn something new every day. I’m not sure whether this will be possible, but I’ll give it a go. Today, I learnt about the butterfly and its saviours. (Yesterday, I learnt that some horses are prone to holding their breath, and that you can get them to relax and breathe by using the canter. That is a rather niche fact, but it is the kind of thing that gives me pleasure.)

Perhaps the new thing every day might stop the gratitude list from growing stale and dull, but I still think there may be rather a lot of repetition. Because of this, I’m going to start it quietly. The blog had rather gone into hibernation anyway, and I’m not sure how many people come here any more. So I feel that I can write things here which are almost private. I need the discipline of publishing, but I don’t want to be stymied by the terror of boring an audience into losing the will to live.

So, if you are reading this, it will be our secret. Who knows? It might be more fascinating than I think. I’ll obviously try not to be a crashing bore, but I can’t make any guarantees. And if you are kindly accepting that risk, then I am grateful for your forbearance.

Published on January 01, 2020 09:29

December 27, 2019

Life Lessons Can Come in the Most Unexpected Ways.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

The day after Christmas, I did something wrong. It was also pretty stupid. I do wrong and stupid things all the time, but this one was in public.

I idiotically waded into a fox row.

There is a barrister on Twitter whom I follow. He tweeted something about having killed a fox. It sounds almost impossibly thick of me, but I didn’t pay much attention to that. He has always seemed an intelligent and humane man, so I think I assumed he was either exaggerating for shock effect, or had done it to put a wounded animal out of its misery, or was protecting his chickens. It was the responses that drew my attention. They were all very much on the side of the fox. And this triggered something deep inside me.

I know now what I did not know then: it was a core belief. A very kind person sent me a fascinating article about this later in the day. Core beliefs are ideas that are so much a part of you that, when they are challenged, your brain feels it like a physical attack. Your amygdala fires up, and you go into the fight reflex, just as if you were protecting yourself from a marauder with a gun. This is why you sometimes react disproportionately to something which, really, in the wide scheme of things, does not matter that much.

One of my core beliefs, I realise, has always been that foxes are bastards. I had never examined this or challenged this. I grew up in the countryside, and had seen the pitiful corpses of chickens and bantams after a fox had been. Everyone around us had such stories. I knew also of the tiny lambs carried off by what I grew up to see as ruthless predators.

Another of my core beliefs is fairness. To my childish mind, it was incredibly unfair not only that foxes picked on vulnerable creatures who had absolutely no chance of fighting back, but that they did not - or so I believed - kill to survive, but for pleasure. Why else would they kill every single poor chicken, but take only one?

This childhood belief was bolstered, as I grew older, by the fatal outrider of confirmation bias. I only paid attention to stories about foxes behaving badly. There! I thought. See! They are the serial killers of the animal world. The shining knights in armour were the beleaguered farmers, desperately trying to protect their flocks and fowl from a wily enemy. The stories we tell ourselves are crazy powerful, and this one had an almost mythical strength in my mind.

Everywhere I looked, it seemed, there were defenders of the fox, taken in by the fluffy cuteness, whilst nobody seemed to be standing up for the chickens and the lambs. And that was what was I believed was happening on Twitter, as the furious hordes weighed in.

I’ve been struggling this Christmas. One of my oldest and dearest friends died suddenly not long ago, and I’ve been wrangling with my old companion, grief. There can be a fury in grief, but I told myself I had no anger at the unfairness of a light gone out too soon. I was going to mourn my friend in a straight, honest way. I would look the sadness in the whites of its eyes, and accept my own vulnerability. Of course, it’s never as simple as that. I don’t think I was doing good, straightforward grieving at all. I was pretending that I was managing, when in fact I was drowning, not waving.

And all that hidden, denied anger over the profound unfairness of a wonderful person taken from the world found its release on social media. (There are several levels of stupidity in what I did, but to march into a public row when I was missing a layer of skin was possibly the most foolish. I’m far too sensitive at the best of times, but in sorrow I have absolutely no defences against anything.)

So I said something asinine about not understanding why everyone was defending the fox when foxes are the Charles Manson of the animal kingdom. What about the chickens? I said. Then, in the middle of what I did not realise was an amygdala hijack, I compounded the error by adding two tweets on my own timeline. I deleted them all once I realised my absurdity, but I think I said something about how I did not understand why people were allowed to dislike any animal except the fox. You can not be fond of cats, I said, but you have to love the adorable fox.

As you can see, pretty much everything I wrote was factually inaccurate. I was also anthropomorphising, a sin I sternly try to avoid in all other circumstances. But my blood was up; my core beliefs had been threatened by the crowd; I was beyond rational thought.

What happened next was horrible at the time, but is really interesting to me now. The mob - and that was what it felt like - turned on me. It felt like they were the foxes, and I was the chicken in the coop. I was 'disgusting' and 'moronic' and 'a revolting hypocrite'. This was partly because of the Charles Manson thing, I think, but also because of the context. It read as if I was cheering on the bloke with the bat. I believed, in my folly, that I was sticking up for the chickens. (You can see from this how clouded my brain was.)

I felt stunned and flayed and frightened. I tried to gather my wounded wits. I remembered that I had seen a truly beautiful thing on Facebook not long ago. A gay man was attacked by a women who made a violently homophobic remark. Instead of scolding her or shaming her, he met her with extreme empathy and kindness. By the end, they were friends, and she was no longer making horrible remarks about homosexuality. The power and grace of that response, and the courage too, stuck with me.

I could not reply to all the angry strangers, but I did engage with a few. I took the kind gentleman (I wish I could remember his name) as a model. ‘Thank you so much,’ I wrote, pushing myself to be genuine and not passive-aggressive, ‘for pointing that out’ and I went on to find something good in the fury. There were good things, if one bashed through the abuse. There was passion and honesty and directness, so I emphasised those. I admitted my tweet was badly-worded and impulsive, which it was, and I ended up in harmony with a vegan who started off being incredibly angry, and ended up being gentle and courteous.

Among the rage and the insults, there was good information. Inspired by this, I went and looked up some facts about foxes. One of the good arguments was that they are only following their natural instinct when they kill, and that to give them human intentions of ruthlessness, or murderous glee, or evil cunning was a category error of the worst degree. And that is quite correct. My core belief, which I had never tested, was wrong. I learnt something about the natural world.

I think I will always feel sorrow and pity when I see a group of decapitated chickens, but I won’t ascribe it to some malicious delight on the part of the predator. Pretty much everything I said yesterday was wrong. It’s quite painful to let go of a profound belief, but it’s liberating too. And I can still believe in fairness, I just don’t have to lay unfairness at the feet of the foxes. Nature, after all, is red in tooth and claw, and that is a reality, not a moral choice.

What I also learnt was to think before I type, most especially in times of vulnerability. I had been trying to protect myself, as I navigated the stormy seas of painful emotion, and instead I laid myself bare. I ruined my own Boxing Day, which is usually one of my favourite days of the year. I managed to feel a wash of joy when the beautiful, bold Clan Des Obeaux won the King George, but the bruised, battered feeling of having been set upon returned almost at once.

I was upset by the venom and the intemperate language, and I was also upset by my own wrongness and folly. The fury that rained down on me, I saw, was because those other people probably had their own core beliefs threatened. I kept thinking - why can’t they just tell me they don’t agree, or they think I am in error, rather than calling me names? I see now that this is the red mist of the amygdala, which goes straight for ad hominem. It is the most ancient part of the brain, and the least under the control of modern humans. It does not deal in ‘Perhaps you might find you are mistaken’. It goes straight for ‘You are a truly bad person and must be destroyed.’

I rather wish the people who turned on me in outrage might read this, so they can see that, although their methods were brutal, they did teach me a lesson. They taught me not to go on the offensive or the defensive, but to part the curtains of pain and see whether there is a greater truth. Which, of course, there was. I’d been trading in non-truth, in this particular area, and now I am enlightened. They won’t read it, because they don’t follow me. They are part of the wider Twitter universe, and they will have moved on to the next big story by now. But I’d like them to know that they did me a favour. Another of my core beliefs is of the absolute majesty of good manners. I have discovered that sometimes a bit of rudeness can shock open the hard nut of an entrenched belief.

I write my mea culpa anyway, even if it will only be read by seven people and a goat, because here is yet another of my core beliefs - you have to embrace your mistakes. You have to lean into them, you have to bash through the humiliation, you have to make amends.

I also learnt something beautiful, in all my wrongness. I learnt that there is a huge amount of kindness and restraint in the turbulent waters of the social media. There must have been many, many people among my three thousand and something followers who thought, ‘Goodness, she’s got in a frightful muddle on this one.’ Only one of them (one!) was critical, and that criticism was very mild. The others either politely ignored my raddled thinking or could see that I was not quite myself and held their fire. Many, which is astonishing, were gently sympathetic, as if they could tell that I'd got myself into a fix of my own making.

I have not said much publicly about my lost compadre. I do not want to make a parade, and also I have this powerful feeling that it’s not my grief to write about. It belongs first to his family, and there is a matter of privacy and respect. It is, truly, not all about me. I always want to write about everything, because that is how I make sense of the world. It is how I have always mended my broken heart. But this was not my story to tell. (I mention it cautiously here, because I think it’s an important strand in this parable, for about three different reasons. It’s an example of how grief can make you clumsy, and how denied parts of sorrow will find their route out in curious ways, and how just trying to be stoical and British does not always work.)

I had, however, referred to it in oblique ways, and I think my thoughtful, good-hearted Twitter band must have sensed there was something going on. So they gave me a pass on the moment of fox madness. And that in itself is a truly remarkable thing, and something that touches me very much.

There, it is all out now. I wish I had been able to make it pithy, and funny, and wry. But it wasn’t really any of those things. It prompted a new perspective, and a great wash of tears which I had been bottling up inside, and a rueful, relieved acknowledgement of my own flawed humanity. So perhaps Boxing Day was not ruined after all. One learns good life lessons in the most unexpected ways.

The day after Christmas, I did something wrong. It was also pretty stupid. I do wrong and stupid things all the time, but this one was in public.

I idiotically waded into a fox row.

There is a barrister on Twitter whom I follow. He tweeted something about having killed a fox. It sounds almost impossibly thick of me, but I didn’t pay much attention to that. He has always seemed an intelligent and humane man, so I think I assumed he was either exaggerating for shock effect, or had done it to put a wounded animal out of its misery, or was protecting his chickens. It was the responses that drew my attention. They were all very much on the side of the fox. And this triggered something deep inside me.

I know now what I did not know then: it was a core belief. A very kind person sent me a fascinating article about this later in the day. Core beliefs are ideas that are so much a part of you that, when they are challenged, your brain feels it like a physical attack. Your amygdala fires up, and you go into the fight reflex, just as if you were protecting yourself from a marauder with a gun. This is why you sometimes react disproportionately to something which, really, in the wide scheme of things, does not matter that much.

One of my core beliefs, I realise, has always been that foxes are bastards. I had never examined this or challenged this. I grew up in the countryside, and had seen the pitiful corpses of chickens and bantams after a fox had been. Everyone around us had such stories. I knew also of the tiny lambs carried off by what I grew up to see as ruthless predators.

Another of my core beliefs is fairness. To my childish mind, it was incredibly unfair not only that foxes picked on vulnerable creatures who had absolutely no chance of fighting back, but that they did not - or so I believed - kill to survive, but for pleasure. Why else would they kill every single poor chicken, but take only one?

This childhood belief was bolstered, as I grew older, by the fatal outrider of confirmation bias. I only paid attention to stories about foxes behaving badly. There! I thought. See! They are the serial killers of the animal world. The shining knights in armour were the beleaguered farmers, desperately trying to protect their flocks and fowl from a wily enemy. The stories we tell ourselves are crazy powerful, and this one had an almost mythical strength in my mind.

Everywhere I looked, it seemed, there were defenders of the fox, taken in by the fluffy cuteness, whilst nobody seemed to be standing up for the chickens and the lambs. And that was what was I believed was happening on Twitter, as the furious hordes weighed in.

I’ve been struggling this Christmas. One of my oldest and dearest friends died suddenly not long ago, and I’ve been wrangling with my old companion, grief. There can be a fury in grief, but I told myself I had no anger at the unfairness of a light gone out too soon. I was going to mourn my friend in a straight, honest way. I would look the sadness in the whites of its eyes, and accept my own vulnerability. Of course, it’s never as simple as that. I don’t think I was doing good, straightforward grieving at all. I was pretending that I was managing, when in fact I was drowning, not waving.

And all that hidden, denied anger over the profound unfairness of a wonderful person taken from the world found its release on social media. (There are several levels of stupidity in what I did, but to march into a public row when I was missing a layer of skin was possibly the most foolish. I’m far too sensitive at the best of times, but in sorrow I have absolutely no defences against anything.)

So I said something asinine about not understanding why everyone was defending the fox when foxes are the Charles Manson of the animal kingdom. What about the chickens? I said. Then, in the middle of what I did not realise was an amygdala hijack, I compounded the error by adding two tweets on my own timeline. I deleted them all once I realised my absurdity, but I think I said something about how I did not understand why people were allowed to dislike any animal except the fox. You can not be fond of cats, I said, but you have to love the adorable fox.

As you can see, pretty much everything I wrote was factually inaccurate. I was also anthropomorphising, a sin I sternly try to avoid in all other circumstances. But my blood was up; my core beliefs had been threatened by the crowd; I was beyond rational thought.

What happened next was horrible at the time, but is really interesting to me now. The mob - and that was what it felt like - turned on me. It felt like they were the foxes, and I was the chicken in the coop. I was 'disgusting' and 'moronic' and 'a revolting hypocrite'. This was partly because of the Charles Manson thing, I think, but also because of the context. It read as if I was cheering on the bloke with the bat. I believed, in my folly, that I was sticking up for the chickens. (You can see from this how clouded my brain was.)

I felt stunned and flayed and frightened. I tried to gather my wounded wits. I remembered that I had seen a truly beautiful thing on Facebook not long ago. A gay man was attacked by a women who made a violently homophobic remark. Instead of scolding her or shaming her, he met her with extreme empathy and kindness. By the end, they were friends, and she was no longer making horrible remarks about homosexuality. The power and grace of that response, and the courage too, stuck with me.

I could not reply to all the angry strangers, but I did engage with a few. I took the kind gentleman (I wish I could remember his name) as a model. ‘Thank you so much,’ I wrote, pushing myself to be genuine and not passive-aggressive, ‘for pointing that out’ and I went on to find something good in the fury. There were good things, if one bashed through the abuse. There was passion and honesty and directness, so I emphasised those. I admitted my tweet was badly-worded and impulsive, which it was, and I ended up in harmony with a vegan who started off being incredibly angry, and ended up being gentle and courteous.

Among the rage and the insults, there was good information. Inspired by this, I went and looked up some facts about foxes. One of the good arguments was that they are only following their natural instinct when they kill, and that to give them human intentions of ruthlessness, or murderous glee, or evil cunning was a category error of the worst degree. And that is quite correct. My core belief, which I had never tested, was wrong. I learnt something about the natural world.

I think I will always feel sorrow and pity when I see a group of decapitated chickens, but I won’t ascribe it to some malicious delight on the part of the predator. Pretty much everything I said yesterday was wrong. It’s quite painful to let go of a profound belief, but it’s liberating too. And I can still believe in fairness, I just don’t have to lay unfairness at the feet of the foxes. Nature, after all, is red in tooth and claw, and that is a reality, not a moral choice.

What I also learnt was to think before I type, most especially in times of vulnerability. I had been trying to protect myself, as I navigated the stormy seas of painful emotion, and instead I laid myself bare. I ruined my own Boxing Day, which is usually one of my favourite days of the year. I managed to feel a wash of joy when the beautiful, bold Clan Des Obeaux won the King George, but the bruised, battered feeling of having been set upon returned almost at once.

I was upset by the venom and the intemperate language, and I was also upset by my own wrongness and folly. The fury that rained down on me, I saw, was because those other people probably had their own core beliefs threatened. I kept thinking - why can’t they just tell me they don’t agree, or they think I am in error, rather than calling me names? I see now that this is the red mist of the amygdala, which goes straight for ad hominem. It is the most ancient part of the brain, and the least under the control of modern humans. It does not deal in ‘Perhaps you might find you are mistaken’. It goes straight for ‘You are a truly bad person and must be destroyed.’

I rather wish the people who turned on me in outrage might read this, so they can see that, although their methods were brutal, they did teach me a lesson. They taught me not to go on the offensive or the defensive, but to part the curtains of pain and see whether there is a greater truth. Which, of course, there was. I’d been trading in non-truth, in this particular area, and now I am enlightened. They won’t read it, because they don’t follow me. They are part of the wider Twitter universe, and they will have moved on to the next big story by now. But I’d like them to know that they did me a favour. Another of my core beliefs is of the absolute majesty of good manners. I have discovered that sometimes a bit of rudeness can shock open the hard nut of an entrenched belief.

I write my mea culpa anyway, even if it will only be read by seven people and a goat, because here is yet another of my core beliefs - you have to embrace your mistakes. You have to lean into them, you have to bash through the humiliation, you have to make amends.

I also learnt something beautiful, in all my wrongness. I learnt that there is a huge amount of kindness and restraint in the turbulent waters of the social media. There must have been many, many people among my three thousand and something followers who thought, ‘Goodness, she’s got in a frightful muddle on this one.’ Only one of them (one!) was critical, and that criticism was very mild. The others either politely ignored my raddled thinking or could see that I was not quite myself and held their fire. Many, which is astonishing, were gently sympathetic, as if they could tell that I'd got myself into a fix of my own making.

I have not said much publicly about my lost compadre. I do not want to make a parade, and also I have this powerful feeling that it’s not my grief to write about. It belongs first to his family, and there is a matter of privacy and respect. It is, truly, not all about me. I always want to write about everything, because that is how I make sense of the world. It is how I have always mended my broken heart. But this was not my story to tell. (I mention it cautiously here, because I think it’s an important strand in this parable, for about three different reasons. It’s an example of how grief can make you clumsy, and how denied parts of sorrow will find their route out in curious ways, and how just trying to be stoical and British does not always work.)

I had, however, referred to it in oblique ways, and I think my thoughtful, good-hearted Twitter band must have sensed there was something going on. So they gave me a pass on the moment of fox madness. And that in itself is a truly remarkable thing, and something that touches me very much.

There, it is all out now. I wish I had been able to make it pithy, and funny, and wry. But it wasn’t really any of those things. It prompted a new perspective, and a great wash of tears which I had been bottling up inside, and a rueful, relieved acknowledgement of my own flawed humanity. So perhaps Boxing Day was not ruined after all. One learns good life lessons in the most unexpected ways.

Published on December 27, 2019 10:13

October 30, 2019

The Russian.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

A Russian philologist wants to be my friend.

I stare at the request on Facebook. The first thing I think is: mafia. Isn’t that terrible? I don’t think War and Peace, or The Cherry Orchard, or Torrents of Spring. I don’t think of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, or of the 1812 Overture, or of anything by Rimsky-Korsakov. (I don’t actually know any music by Rimsky-Korsakov, but it’s the most brilliant name in all of classical music and I just love typing it.)

I am appalled. I have accidentally become a Russian bigot. And after everything I tell myself about not making assumptions. There is lovely Eugene the philologist, and I at once think that he must have done something extremely dodgy in oil and gas. It would be like him looking at me and thinking that because I am British I must be a football hooligan and drink tea all day and hang upon every word of Nigel Farage. Only worse.

I’m making a bit of a joke to cover up how appalled I really am at my own thought processes.

And here is the even more terrible thing - Eugene looks incredibly nice. He is young and smiling, with an open, friendly face. There are pictures of him with an extremely pretty and equally smiley young woman. (Just the kind of thing, says my subconscious, which is still on the dodgy oil and gas kick, that a mafioso would put up, to throw people off the trail. The real Eugene is probably about sixty and lives with his mother.)

I want to say - ‘when did we all get so suspicious?’ - but it’s not we, it’s me. I can’t shuffle this off onto the universal we. This is my own shocker. And it’s not only suspicion of strangers, it is a peculiar and particular national stereotyping. I don’t look at all French people and think: garlic, Sartre, cinq à sept. I don’t think that they are all intellectual snobs who practise infidelity like the old time religion and smoke forty Gitanes a day. I don’t look at the Italians and think ‘mafia’, even though they invented the mafia.

What the hell is going on?

I suppose it may be the wicked work of the availability heuristic. I love the availability heuristic and speak of it often. (You can see what fun I am at parties.) I don’t love it for what it does, which is bad, but for how it sounds on the ear, which is good.

The availability heuristic makes you believe what you last heard and what you most heard. That’s why if you do hang upon the words of Nigel Farage and his cohort you probably believe that all the problems in dear old Blighty are due to Johnny Foreigner coming over here and taking our jobs and stealing our women, and that the moment we get rid of those pesky Eurocrats we benighted Britons shall be free. I watch a lot of news and I’m very interested in American politics, so I see a lot of Putin. I see him with his glassy face-lift and his dead, assassin’s eyes and I think of his days in the FSB and I know perfectly well that there is something rotten in the state of Denmark. I think of all his cronies and how they got their money and I don't think it was by working hard and going to bed early.

And I know someone who knows someone who was married to one of the oligarchs, and I know that this someone had to take six bodyguards and four black Range Rovers every time she wanted to go to the shop for a pint of milk.

The last time I was in London, there were new Russians everywhere and there was something about the way they spent their money which made me uneasy. (It was very weird. They were all young men in extremely sharp and slightly too shiny suits, and they lounged about, smoking cigarettes and casting sidelong glances at the women who passed by, and they gazed at their spanking new Ferraris and Porsches with lascivious eyes. I was brought up to dislike overt adoration of money, and they made me very, very uncomfortable.)

So those are my availability hubristics, and they are all bad. The days when I used to go to see Uncle Vanya at the Donmar and Ivanov at the Almeida are far behind me. In those days, I thought all Russians had poetry in their soul. I thought they were the most romantic and the toughest people on earth. They could sing ancient folk songs with tears in their eyes but they could still survive Stalingrad and the war and the long years of Soviet oppression. I remember a friend of mine coming back from a train trip to Russia in the late eighties and saying that every time he got off the train he would be approached by enterprising, youthful Russians, beaming at him and saying, ‘Hello, young Western peoples. You sell shoes?’

They survived the queues for bread and the no shoes and the daily terrors of dictatorship. They somehow kept their spirit when they were surrounded by drabness. And they still had poetry in their soul. What people could do that?

And now, because of Putin and the thugocracy, the first thing I think is mafia. That’s my own cheap laziness, but it’s also their fault, those thugs that run Russia now and who are always in the news. And maybe it’s a little bit the fault of the news itself. They don’t tell us the good stuff any more, if they ever did. The newshounds are too interested by the strange president with his unreadable face and the billionaires who own half of Mayfair and the shady men with the polonium near Salisbury cathedral. And who can blame them? Those are incredible stories. But they are not the only story.

This is the second time this week that I have had to talk myself down from the window ledge of false assumptions. Being back on the blog is very good for my self-awareness. (Although it’s slightly tiring, finding out that my flawed self is so very flawed.)

I feel better, so I decide I shall be friends with Eugene and stop jumping to such horrid, unfair conclusions about someone I have never met. I think: I’ll just look up Cherkasy University, where he studies. Just to see.

Cherkasy University looks enchanting. The students appear to do wonderful things with folk architecture, and flora and fauna, and differential equations. Everything looks very sunny.

I’ll just see where it is, I say to myself, imagining it to be in some glorious, wild part of the Urals.

It’s in Ukraine.

Eugene is not a Russian at all. He’s a plucky Ukrainian, who almost certainly would like the Crimea back. He’s not a front for the old and gas hoods, or a mafia bot who wants to be friends with me because he wants to steal the election. He is a saintly freedom fighter standing up for his beloved homeland.

I look at what I have just written.

I’ve never met a Ukrainian in my life, but, in my mind, it appears, they are all plucky. And patriotic. And ready to fight for liberty. I’m sure that if I dug a little further, I’d probably find I believed they all played the balalaika and were cheerful in the face of adversity.

And there I was, all this time, thinking I was a lovely small-L liberal, with my open mind and my ability to see both sides of the argument and my refusal to give in to stereotypes.

This not making assumptions business is going to be harder than I thought.

PS. I suddenly realise that just because you go to university in the Ukraine, it does not mean you are Ukrainian. It's perfectly possible that Eugene comes from Vladivostok. In the end, it doesn't matter, because he's taught me a most valuable lesson.

A Russian philologist wants to be my friend.

I stare at the request on Facebook. The first thing I think is: mafia. Isn’t that terrible? I don’t think War and Peace, or The Cherry Orchard, or Torrents of Spring. I don’t think of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, or of the 1812 Overture, or of anything by Rimsky-Korsakov. (I don’t actually know any music by Rimsky-Korsakov, but it’s the most brilliant name in all of classical music and I just love typing it.)

I am appalled. I have accidentally become a Russian bigot. And after everything I tell myself about not making assumptions. There is lovely Eugene the philologist, and I at once think that he must have done something extremely dodgy in oil and gas. It would be like him looking at me and thinking that because I am British I must be a football hooligan and drink tea all day and hang upon every word of Nigel Farage. Only worse.

I’m making a bit of a joke to cover up how appalled I really am at my own thought processes.

And here is the even more terrible thing - Eugene looks incredibly nice. He is young and smiling, with an open, friendly face. There are pictures of him with an extremely pretty and equally smiley young woman. (Just the kind of thing, says my subconscious, which is still on the dodgy oil and gas kick, that a mafioso would put up, to throw people off the trail. The real Eugene is probably about sixty and lives with his mother.)

I want to say - ‘when did we all get so suspicious?’ - but it’s not we, it’s me. I can’t shuffle this off onto the universal we. This is my own shocker. And it’s not only suspicion of strangers, it is a peculiar and particular national stereotyping. I don’t look at all French people and think: garlic, Sartre, cinq à sept. I don’t think that they are all intellectual snobs who practise infidelity like the old time religion and smoke forty Gitanes a day. I don’t look at the Italians and think ‘mafia’, even though they invented the mafia.

What the hell is going on?

I suppose it may be the wicked work of the availability heuristic. I love the availability heuristic and speak of it often. (You can see what fun I am at parties.) I don’t love it for what it does, which is bad, but for how it sounds on the ear, which is good.

The availability heuristic makes you believe what you last heard and what you most heard. That’s why if you do hang upon the words of Nigel Farage and his cohort you probably believe that all the problems in dear old Blighty are due to Johnny Foreigner coming over here and taking our jobs and stealing our women, and that the moment we get rid of those pesky Eurocrats we benighted Britons shall be free. I watch a lot of news and I’m very interested in American politics, so I see a lot of Putin. I see him with his glassy face-lift and his dead, assassin’s eyes and I think of his days in the FSB and I know perfectly well that there is something rotten in the state of Denmark. I think of all his cronies and how they got their money and I don't think it was by working hard and going to bed early.

And I know someone who knows someone who was married to one of the oligarchs, and I know that this someone had to take six bodyguards and four black Range Rovers every time she wanted to go to the shop for a pint of milk.

The last time I was in London, there were new Russians everywhere and there was something about the way they spent their money which made me uneasy. (It was very weird. They were all young men in extremely sharp and slightly too shiny suits, and they lounged about, smoking cigarettes and casting sidelong glances at the women who passed by, and they gazed at their spanking new Ferraris and Porsches with lascivious eyes. I was brought up to dislike overt adoration of money, and they made me very, very uncomfortable.)

So those are my availability hubristics, and they are all bad. The days when I used to go to see Uncle Vanya at the Donmar and Ivanov at the Almeida are far behind me. In those days, I thought all Russians had poetry in their soul. I thought they were the most romantic and the toughest people on earth. They could sing ancient folk songs with tears in their eyes but they could still survive Stalingrad and the war and the long years of Soviet oppression. I remember a friend of mine coming back from a train trip to Russia in the late eighties and saying that every time he got off the train he would be approached by enterprising, youthful Russians, beaming at him and saying, ‘Hello, young Western peoples. You sell shoes?’

They survived the queues for bread and the no shoes and the daily terrors of dictatorship. They somehow kept their spirit when they were surrounded by drabness. And they still had poetry in their soul. What people could do that?

And now, because of Putin and the thugocracy, the first thing I think is mafia. That’s my own cheap laziness, but it’s also their fault, those thugs that run Russia now and who are always in the news. And maybe it’s a little bit the fault of the news itself. They don’t tell us the good stuff any more, if they ever did. The newshounds are too interested by the strange president with his unreadable face and the billionaires who own half of Mayfair and the shady men with the polonium near Salisbury cathedral. And who can blame them? Those are incredible stories. But they are not the only story.

This is the second time this week that I have had to talk myself down from the window ledge of false assumptions. Being back on the blog is very good for my self-awareness. (Although it’s slightly tiring, finding out that my flawed self is so very flawed.)

I feel better, so I decide I shall be friends with Eugene and stop jumping to such horrid, unfair conclusions about someone I have never met. I think: I’ll just look up Cherkasy University, where he studies. Just to see.

Cherkasy University looks enchanting. The students appear to do wonderful things with folk architecture, and flora and fauna, and differential equations. Everything looks very sunny.

I’ll just see where it is, I say to myself, imagining it to be in some glorious, wild part of the Urals.

It’s in Ukraine.

Eugene is not a Russian at all. He’s a plucky Ukrainian, who almost certainly would like the Crimea back. He’s not a front for the old and gas hoods, or a mafia bot who wants to be friends with me because he wants to steal the election. He is a saintly freedom fighter standing up for his beloved homeland.

I look at what I have just written.

I’ve never met a Ukrainian in my life, but, in my mind, it appears, they are all plucky. And patriotic. And ready to fight for liberty. I’m sure that if I dug a little further, I’d probably find I believed they all played the balalaika and were cheerful in the face of adversity.

And there I was, all this time, thinking I was a lovely small-L liberal, with my open mind and my ability to see both sides of the argument and my refusal to give in to stereotypes.

This not making assumptions business is going to be harder than I thought.

PS. I suddenly realise that just because you go to university in the Ukraine, it does not mean you are Ukrainian. It's perfectly possible that Eugene comes from Vladivostok. In the end, it doesn't matter, because he's taught me a most valuable lesson.

Published on October 30, 2019 02:57

October 29, 2019

An Unexpected Poet and a Meeting in the Woods.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} span.Apple-tab-span {white-space:pre}

I call, merrily, ‘Goodbye, Gilly. Lovely to see you.’ I wasn’t at all merry an hour earlier. I woke up, as I sometimes do, with a sense of pressure and portent. I usually put into action a potent combination of hippy dippy and spit-spot to deal with this waking doom. Some days it is easier than others.

I’m wrestling with a big piece of work, which is in danger of winning the fight. I have lost all faith in my elected representatives. The Brexit omnishambles makes me want to chew my own arm off. And I made the mistake of watching some American political programmes last night, and came face to face with the latest Trumpish incarnation. (I often think of the brilliant and extremely naughty Evelyn Waugh line about James Joyce and Ulysses. ‘You can hear him going mad, sentence by sentence.’ Mr Trump makes Joyce look like an amateur in the bonkerness stakes.)

Oh, and I’m in the middle of the dear old menopause, so there are hormonal storms which blow up out of nowhere.

Which is why, this morning, I had to bring all my Mary Poppins and all my Blitz spirit and all my All You Need Is Love to bear. I had to hunt for the silver linings like a truffle hound. I had to go out and forage for the good stuff.

This blog is called The Small Things for a reason. It is in the small things that I find my daily salvation. And today I found my first consoling small thing on Twitter, of all places.

Someone had retweeted a poem by a man called Nick Asbury. It was so good that I didn’t have any words for it, and I live by words. All the usual superlatives I use - brilliant, dazzling, stunning - somehow felt gaudy and gimcrack.

I went and investigated this Mr Asbury. It turns out that he has written daily poems about the news, and Brexit, and the current political madness. That sounds rather mundane and demoralising, but he’s somehow turned base metal into gold.

I can’t even begin to express how human, funny, melancholy and lyrical the poems are. He’s taken some of the things that make me feel slightly sick every day, and turned them into the stuff of dreams. I know a bit about writing, but I have no idea how he does that.

And, as if the universe was giving me an extra present, it turns out that there is also a Sue Asbury, who makes ravishing pictures which match the poems in spirit and soul. So there is prose beauty and visual beauty.

I don’t understand, I thought, how I have lived in the world and not known about the Asburys.

The sense of doom lifted. There is goodness and fineness out there, if only one digs a little. And I went out into the woods with a little lift of hope in my heart. The dogs ran about in their usual giddy way, filled with the hilarity of living, and the sun was shining and the air was clear and the colours were gleaming and beaming. I made some videos for the writing group I run. ‘Get momentum into your sentences,’ I said. ‘Give them somewhere to go. Let them dance.’

I thought about my own sentences. I thought of letting them run across the open plains like Mongolian ponies. (My current favourite writing metaphor.)

It’s all right, I thought. I shall make it through this day. It won’t be a masterpiece, but it is saved. The Asburys saved it, and the Scottish sunshine saved it, and the woods saved it, and the lurchers saved it; all the small things saved it.

And that was when we saw Gilly. I was absurdly pleased. Gilly is a very big, extremely handsome and comically friendly dog. We see him often in the woods, and he likes to play with my boys whilst I have a chat with his human. This morning, he was not with his usual person and the smiling woman walking him looked slightly surprised when he bounded up to me and I greeted him with cries of joy. I explained how we usually see him with his other human. Her face cleared, as if reassured that I was not a complete freak.

And we talked for a moment, about our dogs, about how funny and sweet Gilly is, about the bright autumn weather and how lucky we are to have it. The smallest of small things. We did not speak of the meaning of life or the secrets of the universe. It was a tiny, ordinary interaction, a matter of quick minutes. But it meant something. It was a little fillip, a reminder that not everyone is shouting and arguing and accusing each other of treachery. Some people are walking their dogs and being polite to strangers in hats.

And that was why, when I waved in farewell and called out, ‘Goodbye, Gilly,’ I said the words merrily. You can’t just expect loveliness to be there, waiting for you each day, when you wake from troubled dreams. You have to go out and find it.

I call, merrily, ‘Goodbye, Gilly. Lovely to see you.’ I wasn’t at all merry an hour earlier. I woke up, as I sometimes do, with a sense of pressure and portent. I usually put into action a potent combination of hippy dippy and spit-spot to deal with this waking doom. Some days it is easier than others.

I’m wrestling with a big piece of work, which is in danger of winning the fight. I have lost all faith in my elected representatives. The Brexit omnishambles makes me want to chew my own arm off. And I made the mistake of watching some American political programmes last night, and came face to face with the latest Trumpish incarnation. (I often think of the brilliant and extremely naughty Evelyn Waugh line about James Joyce and Ulysses. ‘You can hear him going mad, sentence by sentence.’ Mr Trump makes Joyce look like an amateur in the bonkerness stakes.)

Oh, and I’m in the middle of the dear old menopause, so there are hormonal storms which blow up out of nowhere.

Which is why, this morning, I had to bring all my Mary Poppins and all my Blitz spirit and all my All You Need Is Love to bear. I had to hunt for the silver linings like a truffle hound. I had to go out and forage for the good stuff.

This blog is called The Small Things for a reason. It is in the small things that I find my daily salvation. And today I found my first consoling small thing on Twitter, of all places.

Someone had retweeted a poem by a man called Nick Asbury. It was so good that I didn’t have any words for it, and I live by words. All the usual superlatives I use - brilliant, dazzling, stunning - somehow felt gaudy and gimcrack.

I went and investigated this Mr Asbury. It turns out that he has written daily poems about the news, and Brexit, and the current political madness. That sounds rather mundane and demoralising, but he’s somehow turned base metal into gold.

I can’t even begin to express how human, funny, melancholy and lyrical the poems are. He’s taken some of the things that make me feel slightly sick every day, and turned them into the stuff of dreams. I know a bit about writing, but I have no idea how he does that.

And, as if the universe was giving me an extra present, it turns out that there is also a Sue Asbury, who makes ravishing pictures which match the poems in spirit and soul. So there is prose beauty and visual beauty.

I don’t understand, I thought, how I have lived in the world and not known about the Asburys.

The sense of doom lifted. There is goodness and fineness out there, if only one digs a little. And I went out into the woods with a little lift of hope in my heart. The dogs ran about in their usual giddy way, filled with the hilarity of living, and the sun was shining and the air was clear and the colours were gleaming and beaming. I made some videos for the writing group I run. ‘Get momentum into your sentences,’ I said. ‘Give them somewhere to go. Let them dance.’

I thought about my own sentences. I thought of letting them run across the open plains like Mongolian ponies. (My current favourite writing metaphor.)

It’s all right, I thought. I shall make it through this day. It won’t be a masterpiece, but it is saved. The Asburys saved it, and the Scottish sunshine saved it, and the woods saved it, and the lurchers saved it; all the small things saved it.

And that was when we saw Gilly. I was absurdly pleased. Gilly is a very big, extremely handsome and comically friendly dog. We see him often in the woods, and he likes to play with my boys whilst I have a chat with his human. This morning, he was not with his usual person and the smiling woman walking him looked slightly surprised when he bounded up to me and I greeted him with cries of joy. I explained how we usually see him with his other human. Her face cleared, as if reassured that I was not a complete freak.

And we talked for a moment, about our dogs, about how funny and sweet Gilly is, about the bright autumn weather and how lucky we are to have it. The smallest of small things. We did not speak of the meaning of life or the secrets of the universe. It was a tiny, ordinary interaction, a matter of quick minutes. But it meant something. It was a little fillip, a reminder that not everyone is shouting and arguing and accusing each other of treachery. Some people are walking their dogs and being polite to strangers in hats.

And that was why, when I waved in farewell and called out, ‘Goodbye, Gilly,’ I said the words merrily. You can’t just expect loveliness to be there, waiting for you each day, when you wake from troubled dreams. You have to go out and find it.

Published on October 29, 2019 06:06

October 28, 2019

In Which The Asda Man Teaches me a Life Lesson

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 16.0px} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 14.0px Georgia; color: #000000; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} span.Apple-tab-span {white-space:pre}

One of the things I really enjoy in life is thinking that I am a pretty decent person. I can’t tell you how much pleasure it gives me. I sit about and say to myself, ‘You know, you really are quite decent.’ I would be incredibly happy if, after I died, someone said, ‘She was pretty decent and she tried her best.’ I’d also like it if they mentioned the hats. I’m very proud of my hats.

And here is one of the things that pretty decent people don’t do: they don’t make assumptions. My dad taught me that, not by word but by example. He took people exactly as they came. If they made him laugh, he loved them. If they didn’t, he didn’t. (He didn’t hate them. I don’t think he was capable of hate. But he could not love the bores.)

This morning, I realised that I make assumptions all the time.