Tania Kindersley's Blog, page 74

July 28, 2013

Love, hate and Twitter. Or, the good and bad of the internet.

Yesterday, someone called me a pompous, sanctimonious arse.

I was ill for three days; that is why there has been radio silence. There was a fairly ordinary state of health one moment, and then – hit all over with hammers. It’s that kind of thing when you can hardly move or speak, just groan. It made me think of how I take health for granted. I always say of course, of course it’s the most precious thing, but I’m not sure I really stop to appreciate the actual truth of that. When your entire body hurts and you can’t move, nothing is worth anything. You could have a cellar full of rubies downstairs, and it would not matter a damn. I thought of all those people who struggle with chronic pain every day of their lives, and felt very small and very grateful.

Anyway, it’s a Sunday, so I’m going to tell you a rambling story. Yesterday, I was a bit better, but still very tottery, so I lay in bed with my swimmy head and Stanley the Dog gazing at me with his best Florence Nightingale eyes, and watched the racing. I still get rather grumpy with Channel 4 for aspects of their coverage – they have the maddening habit of putting banging, non-specific music over all their montages and even across Clare Balding saying interesting things about the history of Ascot, almost drowning out her accomplished words – but I do appreciate that they allow me to watch the racing live on their website. (I have no television in the bedroom.) It was good racing and even though my eyeballs felt like boiled sweets I was enjoying it.

A mighty German horse called Novellist absolutely hosed up in the big race of the day, under the great Johnny Murtagh, and, because it is that time of year, all thoughts turned to the Arc.

Twitter is fascinating in its sociological and cultural make-up. Quite unexpectedly, the racing community has adopted it wholesale, and you will find everyone there from jockeys to betting shop managers to clerks of the course to work riders. One of my favourite Twitter friends turns out to be the head of Coral, which I find rather grand. It’s clever too; he is so nice that I now bet with Coral as well as with William Hill, which is my default account.

So, immediately after the race, where the classy French horse, Cirrus des Aigles, underperformed, and the German horse smashed the track record, a great post-mortem broke out. One gentleman got very shouty and I suddenly could not deal with it, in my weakened state. Instead of sensibly just unfollowing him, I announced it.

This is the danger of social media. It’s in its infancy, and the rules and mores and small etiquettes are still being worked out. Also, I find that when I am in a Twitter storm, which happens usually during sporting events, I often type before I think. I get into a zone, and everything goes public. Some of my kind followers find this faintly diverting, but sometimes it is dangerous.

I did not mention the gentleman by name. I just wrote something like: ‘Am unfollowing cross people. Too weak.’

The cross people clearly knew who they were. Back came the reply: ‘Good riddance.’ Hm, I thought, mazily. Ungracious. I pondered what to do. He is a stranger, and I generally do not have conversations with him; the online ones who have the power to hurt are those with whom one has struck up a relationship. I was not wounded, but perhaps my pride, or something, was a little dented. Foolishly, I wrote another tweet. It went something like: ‘Don’t take it personally, cross people. Festivals of crossness must not be stopped. Just not my thing. Each to each.’

I admit, this was a bit passive-aggressive. The rational part of me knows that some people find a bit of expressed fury marvellously cathartic and invigorating. I believe ardently that speech must not be shut down. On a purely subjective level though, I really do hate it. I do wish that everyone was polite and minded their Ps and Qs. So I was being a little disingenuous. If I had been entirely honest, I would have said: oh, for God’s sake, Cross Person, stop being so grumpy and shouty and rude. I was especially narked because he was shouting at another racing person whom I rather like, and for not much reason.

And that was when he got really cross. ‘You are a pompous sanctimonious arse,’ he wrote.

Well, I thought, that’s that. I went back to the racing, and felt happy as clever, canny Sir Mark Prescott, one of most idiosyncratic characters in the whole of racing, had a quickfire double, with two tremendous, doughty campaigners, Big Thunder and Alcaeus, both of whom are on an unstoppable winning streak. I had them in doubles and trebles and a fivefold accumulator, and I won a shed-load of money, even with my viral load, and I felt that that would show the cross person.

But it’s slightly scratched away at me ever since. I was not hurt, because, as I have discovered online, you need to have built up a degree of intimacy for a sudden attack to hit the target. I am vulnerable on the blog, and on my Facebook page, but not to random Tweeters. On the other hand, there was a part of me that really did want to punish that rude person for being so disobliging and intemperate. I wanted to smack him back and hang him out to dry, even though I knew that would be ridiculous, and the only thing to do was gently move on.

Just as I was examining all these feelings, I came, rather late, to the saga of the Jane Austen hate club. I don’t know if you have followed this story. A woman called Caroline Criado-Perez started a campaign to get dear Jane on the British banknotes, and succeeded, and all was lovely, until she started getting a vicious, concerted set of tweets, some of them containing rape threats.

This put my little spat in perspective. I at once went over to sign a petition for Twitter to put up a Report Abuse button, so that these kind of haters can be dealt with. This felt meaningful and pointful, and I forgot my own tiny pinprick.

The whole thing made me think again about the nature of life online. I choose to regard the internet as a benign place, and treat it as such. Most of my blogs and tweets and Facebook posts are positive; I try to resist the temptation to let my inner bitch come out and dance. I feel I should confine her to the privacy of my own room. Unless Channel 4 Racing drives me to a pitch of distraction, which I admit it sometimes does, I attempt to emphasise the positive and skip over the negative.

In particular, when writing racing tweets, I have a very strict rule not to criticise jockeys, even if they do make a hash of a race, because I grew up with a jockey and I know damn well that even the most brilliant will have an off moment, run into traffic, misjudge the pace, and that they will be far too busy criticising themselves to have any need for outside help. Besides, I suspect that the armchair jocks have absolutely no idea what it must be like to have to make split-second decisions whilst going at forty miles an hour on half a ton of youthful thoroughbred, perched on a saddle the size of a postage stamp.

Generally, I find that I get back what I put in. At the very same time the cross man was calling me names, another lovely gent, with whom I have bonded over our mutual love of lurchers, was sending messages of ineffable funniness and sweetness. The good and bad were marching there together, and I chose to let the good win.

But I am perhaps a little naive, even wilfully so. As the blameless Caroline Criado-Perez found, you can do something which seems utterly ordinary and uncontroversial, and suddenly insane people are threatening to violate your very body.

As always, I’m never quite sure what to make of all this. I shall bash on in my hopeful view of the online world, because 90% of it is charming and funny and illuminating and generous and kind. I get glimpses of other lives, radically different from my own. I get sudden belly laughs from complete strangers when I am feeling low. People I shall never meet ask after Stanley the Dog. Properly useful information is shared. There really is wit, and quite often wisdom too.

There are moving collective outpourings, such as the very touching concern for St Nicholas Abbey, as he recovers from a life-threatening injury and two complicated surgeries. He is a great horse, not much known to the general public, but hugely beloved by racing aficionados, and the hope for his welfare touches my heart.

If the price I pay for this is the occasional sanctimonious arse, I think I may count myself lucky.

As for the real, vicious haters, the ones who attack women from behind the craven cloak of anonymity, the interesting thing about them is they do seem far outnumbered. The majority has risen up against them, pointed the finger and said no. They may never go away. We shall never know what private miseries and bitternesses drive them to their own twisted outpourings. But I do know this: they shall not prevail.

Today’s pictures:

Pouring with rain outside and still too tottery for pictures, so here are some quick beloveds:

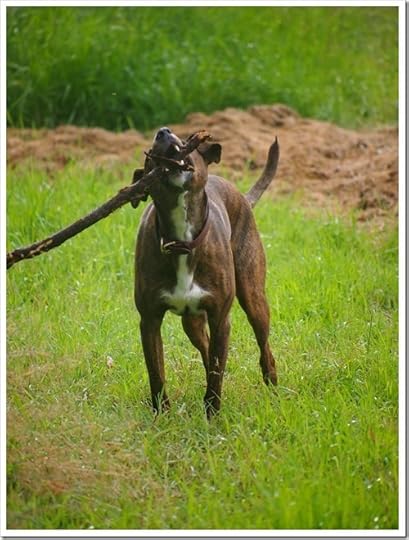

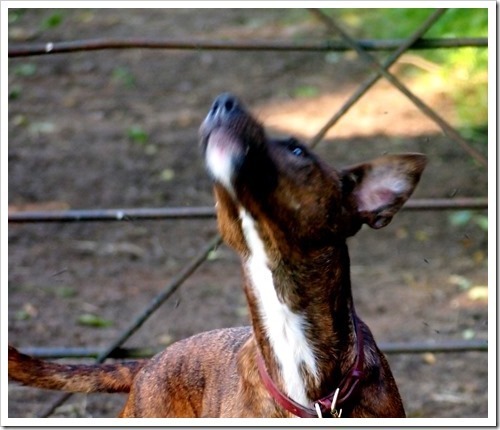

Stanley the Dog does not give a bugger about the internet, BECAUSE HE HAS A GREAT BIG STICK:

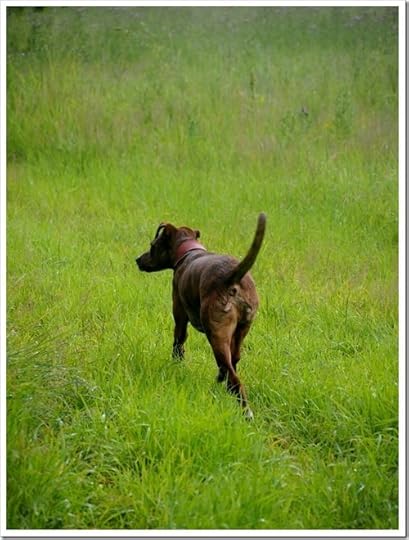

And now he is going to look for another one. You can’t keep a good dog down:

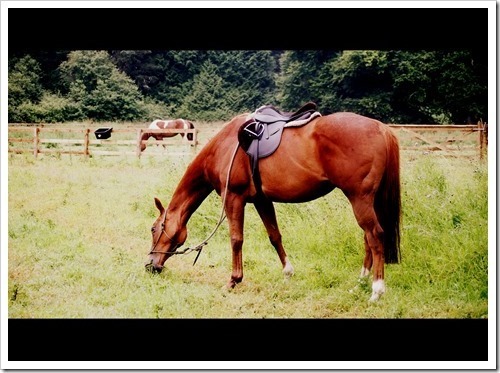

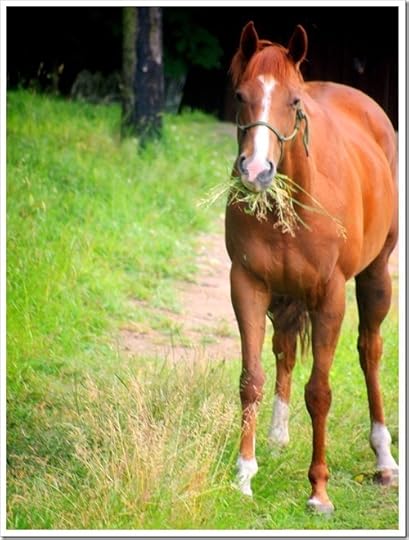

And Red the Mare, after our last lovely ride, thinks only of the green, green grass:

July 24, 2013

No time

The hours have defeated me. There just are not enough of them. Also, there is a bug going round the village and I can feel it trying to get me, its crabbed old fingers stretching and clutching at my poor body. Bastard. I cannot be ill. I have too many responsibilities. I shall dose with Echinacea and iron tonic and chicken soup and, if that fails, bottles of whisky. The bugger shall rue the day.

Just time for two very important pieces of equine news:

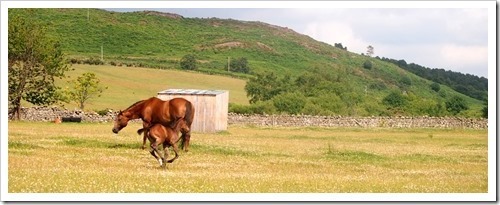

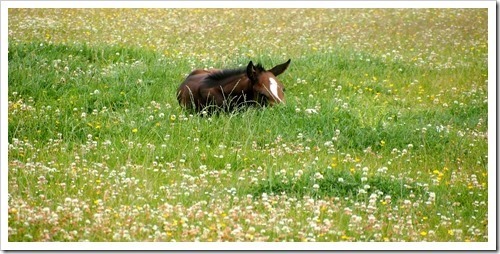

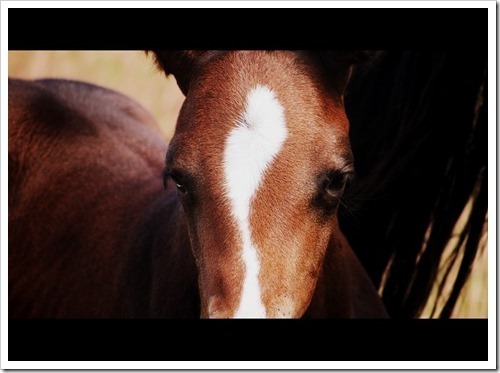

THE HORSEBACK FOAL HAS LEARNT TO GALLOP:

She just figured it out yesterday. She is so overcome with delight at this new skill that she suddenly takes off, zooming round the field like a barrel racer, squealing with delight as she goes. Then she stops and stares at us, incredibly pleased with herself, asking DID YOU SEE THAT????

Her dear, calm mum, who has seen it all before, looks at her as if to say: steady on, small person, don’t run before you can walk. But the two-week-old filly foal will not be quelled. Two, three, four times she makes the circuit, at top speed, cornering as if she is on rails. Then comes the Look at Me whinny again, which is hysterical, because she may be fast, but she has not worked out the voice thing at all. The whinny comes out pitched high, rather ragged, completely unsyncopated. It slightly startles her, because it is clearly not the sound she intended, and she takes on a thoughtful look, as if she knows she must go back to the drawing board.

There is something irresistibly comical about her. If she were a human, she would be Lucille Ball.

And then there was my own mare, who was at her peak and crest of delightfulness and dearness this morning. We did extended walk, quick transitions, yielding the hindquarters, backing one foot at a time. I am teaching her all this on a long rein, hardly using my hands at all. It’s coming from the body. The idea is to teach her to stretch out her neck, which would have been carried taut and high most of her working life, and develop a new set of long, low muscles. She learns so quickly, and pays such good attention, and is so willing to give me a try, even when she is not entirely sure what I am asking, that it makes me want to explode with pride and gratitude.

After her brilliant work, I got off and stood with her for a while, just communing. She put her head on my chest and we contemplated the green world.

I love her every day, but there are times when the love is so intense that I can’t find words for it, when I think that my beating old heart will just lift off into the ether, and float away into the blue sky. This was one of those days.

July 23, 2013

The bells ring; or, in which I refuse to be a cynic.

The day escaped me. There was a lot of loveliness and a lot of rushing about. My beautiful mare had her back done by a brilliant woman. Red was at her sweetest, kindest and best, and it makes my heart sing that now she shall be free from tension and muscle strain.

I have no time for writing now, hardly time for thought. I am still finishing my day’s work and trying to write this blog at the same time. But I did have one thought. It is: I am singingly glad that the bells rang out, and there was a forty-one gun salute, and that the band of the Scots Guards played Congratulations for the royal baby.

I was oddly touched by a picture of happy people waiting outside a London hospital door, sheltering under practical British umbrellas, holding out banners of celebration. The sneerers will sneer, and the mockers will mock, but I think they reveal themselves as nothing more than snobs. They think they are being frightfully clever and egalitarian, wheeling out their republican complaints and their buckets of cold water. What they are really saying is – you, you idiot crowds, you sheep-like rejoicers, are less discerning, less clever, more easily gulled than we are. We, we sophisticates and intellects, see through the flim-flam, the absurdity, the paper-thin circus, to what really matters. You are just being fooled by bread and circuses.

I’m with the Ordinary Decent Britons on this one. I think it is enchanting to have a day of national delight. I’m all for collective celebration. A young prince is born; let the trumpets ring.

Of course it is an oddity to be born a princeling; of course it makes little rational sense. But it is stitched into the national tapestry; it has echoes of Shakespeare in it. It is a happy, gaudy, historical absurdity, and it brings joy in its wake, and I never, ever look the gift horse of joy in the mouth.

If you dissect anything too much, you can reduce it to flimsy. Cricket is nothing more than five long days with a bat and a ball, with rules no one can understand, with commentators saying ‘my dear old thing’, with silly mid-ons and leg before wicket. Yet it brings the same wild uprush of happiness.

A new life has arrived, and if he gets forty-one guns blasting off in Hyde Park instead of a bunch of petrol station carnations, I say hurrah for that. Sometimes I think being a cynic is a cop-out; it’s a defensive crouch, a cheap shot, a drawing back. Expressing uncomplicated enthusiasm is more of an emotional challenge, because it lays you open to mockery; balloons exist to be burst.

The bells are ringing now, as I write this last sentence. I smile as I hear them. Let them ring.

No energy left for proper pictures now. Just a very small selection:

This HorseBack mare is called Red. I love her. She worked her magic on a visitor this afternoon:

Stanley the very Manly has a sodding big stick:

And he’s off to find another one, EVEN BIGGER:

The HorseBack foal:

A delphinium:

My own ridiculously beloved Red, never afraid to look goofy, even with her own excessively posh bloodlines:

If she were a human, she would be a princess, and I let off metaphorical 41 gun salutes for her in my head every day.

July 22, 2013

This land

Warning: crazed insomnia last night, so there is a very real danger none of this may make any sense at all.

I read something today about how humans miss the natural world without even knowing what it is they lack. Most people in Britain live in cities or towns. Cities are glorious, thrilling things. I think they are good things, because they must surely decrease fear of The Other. The Other is there every day, in the streets, on the tube, waiting for the bus. Insularity must be more difficult, in that great melting pot. And there is culture and entertainment and architecture and all the other sophisticated pleasures of which city life is made. When I lived in London, I loved her like a sister. I used to refuse invitations to go away for the weekend because I wanted to mooch about in the sunny streets of Soho, or go to a double bill at The Electric. I wanted smoke and pavements.

People still think it mildly eccentric that I should live so far north, so deep in the hills, at such a distance from the theatre and good Chinese food. But I’ve been thinking about the whole love and trees thing (and love of trees), which is probably why the article on missing the earth caught my eye.

I struggle, as does every sentient human in the middle of life, with all kinds of frets, profound and superficial. I battle with mortality. I worry about all the usual things: money, death, illness, work. I feel the mid-life regret at the scattering of friends. Some live very far away, across wide oceans. Some are only in the south, but might as well be in Ulan Bator. It’s logistically demanding to get a family of four onto an aeroplane to Aberdeen for the weekend. We rely on the fact that we can pick up where we left off, because we have twenty years of hinterland behind us. But still, I miss them.

And yet, for all the frets, I am mostly cheerful. I am occasionally haunted by the spectres of loss, but I do not wake every morning with the black dog of despair snapping at my heels. I read something lately too about depression, the proper kind, not the mild down-in-the-mouth to which people sometimes carelessly apply the word. This was about the real thing, the kind that makes the sufferer feel as if they are in a dank, slimy pit and may never climb out. I feel incredibly blessed that I do not have to crawl out of that pit. Even among all the worries and fears, I find daily joy. I laugh a lot, often at myself. I have a lot of love. I love my mare, I love my family, I love my dog.

I wonder, suddenly, whether this oddly cheery resilience is lent to me by the place itself. I know I bang on about the hills, but it does lift the spirit to see them each day. I regard green things, growing things, ancient earthed things. On Saturday night I sat outside under a venerable stand of oaks and ate sausages and drank beer. It was the glorious trees that gave the evening its savour. I walk on grass and smell clean air. I hear birdsong. I watch the swallows fling and play, as they teach their young ones the mastery of aerodynamics. I stare at lichen and dry stone walls and bark. I happily observe the sheep.

Everyone, even the most fortunate human, needs a little help. Life is baffling and inexplicable and sorrows are inevitable. No one may insulate themselves from loss and heartache. Everyone needs an existential walking stick, to negotiate the rocky paths. I think this dear old land is my stick. Perhaps that is why I show you the daily pictures of it. Look, look, I am saying: this is what saves me.

I think far too much, always have. This is a good thing, and a bad thing. Too much thinking can lead to despair. There are too many unfairnesses, tragedies, inexplicable cruelties, for one paltry mind to reconcile. Love and trees, my darlings, love and trees. And hills and sheep. And Stanley and Red, out in the gentle Scottish air, where they may stretch and play and become one with the majestic landscape they inhabit.

Today’s pictures are a little selection from the past few days. No time for the camera today. I’ve been doing actual work, 1648 words of it. Something, as always, has to give.

In random order:

July 21, 2013

A quiet Sunday dream

The smallest, sweetest, quietest, most private thing: a Sunday ride through the green grass, with my horse and my dog.

The dog is a novel addition. Usually, he does not come with. He can get fractious and excitable when I put the mare into a trot on the ground. When I get up on her, his separation anxiety reaches a fighting pitch. Today, everything was so slow and low-key – it was not as if I were going for A Ride, I was just getting on and ambling about – I thought I would let him roam and see what happened. The horses are so used to him now that if he jumps and freaks they merely raise their heads and look down their elegant noses at him. I could get off and put him in a place of safety if it all went Pete Tong.

But as the red mare and I moved off down the wide grassy track, another calm russet figure trotted at our heels. I turned. He looked up at me, grinning. Yeah, he said, that’s all just absolutely completely fine.

We wandered down to the end where the cows browse on the farther slope. ‘Stanley,’ I said. ‘Don’t go near the cows.’ Stanley did not go near the cows. He turned and followed, in step with the horse.

I put Red into a trot. Stanley the Dog broke into a lope.

I had seen pictures of this, I suddenly realised. For some reason, I think they are in places like Africa, out on some veld or other. It’s a vague sense memory.

I always felt envious when I saw people who could go out with their horse and their hound. My antic sight-dog, I always thought, would forever be too barky and leapy to do that faithful heel-trot. It turns out I was wrong. Without it being a big thing, the impossible happened, and there I was, with my two best beloveds, on a little veld of my very own, living the dream.

I laugh as I write that. It’s such a very, very small dream. It’s not winning the pools, or being awarded a glittering prize, or making the headlines. But I suppose the really good dreams are the ones you can achieve on a quiet, sunshiny, Scottish Sunday, with no one there to watch or clap.

The small private dreams are potent, because they really can come true.

The mare was lovely, and happy. We did a lot of ambling, on the end of a loose rein, because I think of all that hard racing and polo work she did in her previous lives, and I want ambling to go into her muscle memory.

We practised moving one foot at a time. She can do this on the ground, in her sleep; now we are doing it under the saddle. It has utility; it will be brilliant should we ever go out into the wilds and find a tight spot or a tricky gate. But the truth is, I love teaching her that for its own sake.

‘Back one,’ I say, giving her a little signal, and she moves a discrete foot. She is so damn clever, I want to shout, to the hills.

It is a movement so minute as to be hardly discernible, yet it fills me joy. It’s hard to describe in words. It’s the stillness and ease and kind responsiveness of it that delights. It’s like dancing a Jane Austen quadrille.

We did a slow trot and a fast trot and a little canter and some fast, tight turns. Barrel racing, I whooped, in my head.

We had fun. It would win no rosettes, but it was lovely. I wanted to write it because it was one of those things that is contained and entire and perfect in and of itself. It exists for nothing else except to exist; two hours of intense, plain pleasure and communion.

It’s easy to think everything has to be for something: to prove something, signify something. I’m always looking for significance. This just was what it was: three sentient creatures in a green field, having a nice time.

I wanted to record that.

The Best Beloveds:

The quiet green field, where the loveliness happened:

July 19, 2013

A quiet Friday

Ha. After spending all week telling my students about how they may drive off the dark, destructive critical voices, defy The Fear, and believe in their own true selves, I spent all last night tossing and turning, convinced that every single word I wrote here about writing was utter buggery bollocks. The irony elves were busy in the small hours, the little tinkers.

It’s probably because bone-tiredness has set in. I have used up all my energy, so today I am going to sit very still, with a bottle of iron tonic and Test Match Special on at full volume. The voice of Blowers will restore me to sanity and calm.

The dear mare gave me a restorative morning too. Even though the sun started to beat hard from the moment I woke, the set-aside was still cool and shady. We have new neighbours; the sheep have been moved into the high east field, and are wandering and calling as they get used to their new home. I had a long, soothing chat with the farmer this morning. One of his girls was in distress on Wednesday, and I got a message to him so that he could come and get her, and before breakfast he roared up in his dark blue Landrover to thank me. ‘Is she all right, your ewe?’ I asked, concerned. I am very fond of these sheep. The good news is that it was a vitamin B thing, and she will be fine. I love talking to the farmer. I love people who do good things on the land, people who know livestock and weather patterns and are rooted in the earth.

After that lovely beginning, I went down to Red, who is finding the savage sun all a bit too much. She has a heat rash, so I cooled her off with buckets of water, and a little witch hazel, and spent fifteen minutes soothing her poor coat. She does a very touching thing when I do things like this for her. Whether I am anointing a scratch with wound cream, or applying citronella for the flies, or giving her this water treatment, she seems to know that I am doing something for her. She submits with a sort of gentle gratitude, standing very still, offering me her head, looking at me with soft eyes. I am almost certainly making this up in my addled brain, and she is not thinking anything at all. She is a horse, after all. But it does often feel as if she understands that I am here to help.

Then I let her out into the wide set-aside for a pick at the lush grass. I used to take her out on a rope, but now I let her wander freely. She is not going anywhere, and comes at once when I whistle. It was an enchanted thing, watching her find her way through the shady trees, searching out the most delicious patch of grass. She was her most peaceful, equine self, at one with her surroundings; just a horse, at home in a green world.

Neither of us is going to do any work today. We are going to have a lovely Friday holiday. We are just going to be.

Today’s pictures:

The farmer, on the right, coming to have a morning chat:

Red’s blissful morning:

Look at that happy face:

Do you want me to come now?

The hill:

Housekeeping note:

It has been brought to my attention that there are Dear Readers who have broadband that is less than whizzy, and find the blog slow to download, on account of the pictures. I love putting up lots of photographs, so you can see the full Scottish beauty. On the other hand, I imagine it must drive you mad, waiting waiting waiting, for the damn thing to appear on your screen. I’m not quite sure how to resolve this. Too tired to work it out today, but those of you who are seasoned bloggers might have ideas.

In the meantime, have a lovely, sunny Friday. And if you are cricket fans, fingers crossed. Australia about to bat.

July 18, 2013

Writing Workshop, Day Four. Thirty things I know about writing.

I feared I might only turn out to know four, and would have to crawl away with my tail between my legs. But in the end, I did manage to hit the golden number. So, among other things – a bit of a riff on language, a good dose of Prufrock, without which no writing workshop is complete – this is what I told my students today:

1.

Writing is hard work. It should be hard work. This is the language of Shakespeare and Milton you are messing with.

2.

The difference between writers and non-writers is that writers rewrite. Then they rewrite again. Sometimes, the seventeenth draft has to be wrangled from their crabbed, pedantic hands.

3.

Good writing is like jazz. It has a rhythm, and a syncopation. Listen to your writing as you would listen to music. One syllable too many can throw the rhythm off.

4.

Don’t be afraid of playing with metaphor. Be adventurous; be antic. This can bring writing alive and lift your words off the page. But don’t strive too hard for effect. The pudding can swiftly become over-egged.

5.

Writing should be a passion. It might even be an obsession. That’s all right. You need that to get you through the doldrums. And there will be doldrums.

6.

Don’t take yourself seriously, but take your writing very seriously indeed. You might want to keep this fact secret from your family and friends, especially if they are British. They may laugh. Or point. But you must know it, in your secret heart.

7.

Read everything you can get your hands on. If you don’t read, you won’t write. I heard one writer, modishly successful in the nineties, boast at a literary festival that he did not read books. His name has now entirely disappeared from the bookshops. Coincidence? I don’t think so. Reading is fuel for your writing; it is petrol in the tank.

8.

Some people say read the bad as well as the good. They say it cheers you up, because you may know that you can do so much better than this published charlatan or that bogus best-seller. I think you need to be really careful with bad writing. It can depress you and make you want to comfort eat and send your battered brain into a kind of fugue state. Whereas three paragraphs of Fitzgerald will send you racing to the keyboard, inspired by the possibility of brilliance.

9.

Love words. Be bold with them. Throw them up in the air and let them fall as they will. If you don’t love words, you have no business writing a sentence. I’m very hard line on this.

10.

The best piece of writing advice I ever saw, and I think it was from Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird, was: allow yourself to do a really crappy first draft. This is wonderfully liberating. Nobody need ever see it. It can be as baggy and saggy and meandering and nonsensical as you like; there will be no walk of shame. Then you take the thing out behind the bike shed in the second draft and show it who is boss.

11.

The only rule in writing is: there are no rules.

12.

Except: you must never, ever dangle a modifier. Ever. It is not clever and it is not kind.

13.

If someone asked me, which they have not, what the two most important things in writing are, I would say clarity and authenticity. But if that same someone asked me tomorrow, I might say something quite different.

14.

Know the rules. It is important to know them so that you may break them. If you are breaking them through ignorance, you will end up with a mess. If you are breaking them on purpose, you are an iconoclast. If you do break them, make sure they damn well stay broken.

15.

Grammar is important because it shows respect for the reader. Most grammatical notions are not the idiot ravings of a crazed pedant, but designed for the comfort of the reading eye. Bad grammar usually means that the reader has to stop, frown, go back and read the sentence again to make sure of the meaning. This is not polite. We are back to clarity again.

16.

Practice, practice, practice. That is the only thing that will make the difference. I don’t know why people think they can write without practice. A concert pianist would not fail to do her arpeggios. Do your arpeggios.

17.

Don’t talk about writing, except to other writers. It’s quite a dull subject for those who don’t do it, and if you give too much of your passion away in talk, you may lose urgency on the page.

18.

Understand that you will fail. You will fail professionally. Books will be rejected; agents will sack you; critics will maul you. You will fail in the privacy of your own head, because the perfect book that lives there will never quite make it to the page.

19.

Mozart can really help. If you are having a bad morning, and your brain is filled with mud, put the 40th symphony on at full blast and see what happens. There is some research to show he lights up the creative areas of the brain.

20.

Finish. That’s another difference between writers and non-writers. Writers finish. 90,000 words is a long slog. Get good sturdy walking boots.

21.

Find a subject you love, and write about it. Tell the story you want to read. The best way to work out what book to write is to think of the book you search for in the bookshop, but can never find. Make sure your subject really does fascinate you. You are going to spend a very, very long time with it. Someone clever once said something like: if your book doesn’t keep you up nights, it sure isn’t going to keep anyone else up either. (I should probably look up the correct quote, but there is no time. A Dear Reader will doubtless know.)

22.

You don’t have to feel sorry for writers, but in some ways they choose a hard life. All their youthful dreams will be smashed, one by shattered one. Most of them will never win a prize, will never have a best-seller, will barely make a living. Even the ones who are successful in worldly terms will still have to face the melancholy fact that they shall never quite become their heroes. (Their heroes are quite often alcoholic, dead, misanthropic humans, so this may not be entirely a bad thing.)

23.

Jokes are very tricky things in books, but humour is important. My theory is that only the very brilliant can embrace unremitting seriousness. In ordinary hands, a humourless book is half-dead on arrival, and will drag itself around with a lumpen, melancholy refrain.

24.

Write what you know is slightly defeatist advice. There is The Google after all. There is the imagination. Write what you love, what you fear, what comes to you in the night and won’t let you sleep.

25.

I’m not much for the dogmatic You-Must-Do-This. (All evidence to the contrary.) I’m more a shuffle my foot in the dirt and make a mild suggestion sort of person. Imperious advice can be confining and patronising. But if a novice came to me and asked for one single thing to help her become a writer, I would say: learn to touch type. It means your fingers can keep up with your thoughts. It’s the most useful skill I ever learnt. I use it every day and I never stop feeling grateful.

26.

Trust the reader. Not everything has to be spelt out. Readers are clever. They can read between the lines.

27.

There is something quite peculiar about the writing process. There are days when you feel as if you are wading through sand, when you are prodding and heaving and dragging yourself up to a respectable word count. You are almost typing for the sake of it. When you go back and re-read those words, they are often really quite good. On the other hand, when you feel flushed with brilliance, and coruscating sentences fly from your fingers, and you are privately convinced that perhaps you are Scott Fitzgerald after all, you often go back and find the work is thin and gimcrack. I have no idea why this is.

28.

You do have to kill your darlings. Everyone says so, because it is true. I make a special dead darlings file, so the murder is less agonising. That way, they are not quite bloody corpses on the floor, but in a gentle Darling limbo, where I may go and visit them whenever I like. I never do.

29.

Be yourself. The moment you start writing like anyone else, your words go dead on the page.

30.

This is the serious one. I hope you will forgive me.

Writing is frustrating, often unrewarding, financially stupid, exhausting, misunderstood and bizarrely difficult. But it is also a privilege. You get to think thoughts for a living. You get to be interested in everything. No person on the bus is wasted. You may ransack your own tragedies, so at least they are good for something. No heartbreak shall go unexamined. You are also in a fine cohort. You are doing the same job as Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf. I’ve said it before, and I shall say it again: you are playing with the language of Shakespeare and Milton. That is something to brighten a morning.

The course is over. My students were brave and good and willing. I sprung oddities on them, made them reveal themselves, took them, at one stage, on a forced march. (There was a good reason.) They had to listen to me repeat myself, race off on interminable tangents, and mix my metaphors, which is what I do in speech when I get excited. They produced surprising and enchanting work, and I did make them work. I even took them to see the horse. (There was no good reason.)

I salute them all.

No photographs again today. No time. Just the dear foal with her semaphore ears, playing hide and seek with her dreamy mum:

Oh, and PS: Some of this does sound rather grandly prescriptive. There is a bit of must and should. The disclaimer of course is: only if you really want to. Take what you like and leave the rest. I may sound tremendously decided and certain. In fact, the only thing I really know as I grow older is that I know nothing.

PPS. Thank you to the Dear Reader who spotted a typo in the first draft of this. It has now been corrected. My eyes were squinting too much with tiredness to proof-read correctly. It is almost inevitable that when one writes about writing, one will make a howler. The hubris gods, laughing at my puny plan.

July 17, 2013

Writing Workshop, Day Three. Structure, character and opening lines.

Bit of thinking. Small pause. ‘Well, yes,’ they said, tentatively, almost as one. ‘How to write a book.’

Of course they did not quite say that, but that was the gist. So, I decided to tell them, in under three hours. I like a challenge.

I could have said: you start, you keep going, and when you are finished, you stop. And then we could have gone to see the horse.

This is facetious, but it is also slightly true. That really is what you do. It’s gloriously simple and fabulously hard. You need, I think, some hows to help with it. That is what I was trying to provide.

This is a truncated version of some of the things I said. It will not be the most beautiful thing you read today, because I’m trying to convey information, not dazzle you with my prose style. (As if I could.)

1. Structure.

Structure bores me witless, which is probably why I’m not very good at it. But there are things about it I do know. Your book needs a spine. Books with no spine collapse in a mashed soufflé of their own muddle and self-indulgence.

A beginning, middle and end sounds absurdly obvious, but it really does help. How much you know of the spine before you start depends on you. Some people have wall charts and index cards and plot points all worked out. This makes them feel safe, and they write from point to point, like those first steeplechase riders who galloped from spire to spire.

Some people find this too prescriptive, and merely require a more general direction. Then they can play around in between. I generally begin with a vividly-known opening scene; this is the germ of the book that gets me going. I’ll have in my mind three or four pivotal scenes along the way, and a definite finale. Within that, I make it up as I go along, so the journey is one of discovery.

Find the method that suits you. But you should know where you are going, or you will, at some stage, run into the sand, and get lost, and wish you had brought a map.

I include momentum under the heading of structure. A book should have a strong forward motion, which pulls the reader along with it. Sol Stein called this the engine of the book, and he always said that he listened carefully for the moment when the engine started. In a perfect world, it should turn over in the very first sentence.

Even if you are playing about with flashbacks or being cavalier with time, the pulling thread of the book should remain tight. Everything should strain forward, to that inevitable end. It sounds rather old-fashioned and blatant, but the question in the reader’s mind should be: what happens next? You should have a good answer to that question.

You can learn a lot about structure from the art of the screenplay. The strict three act construction, with its set-up, amplification, reversal and resolution can feel a little formulaic, but it’s not a bad thing to hold in your mind, especially if you are a novice. The classic screenplay moment at the end of act two, when it seems that all is lost, followed by the eureka moment when the heroine regains her mojo and sets out once more on her quest, is almost archetypal. It is drawn from the ancient myth form, with a faint Jungian aspect, and that is the reason it is so powerful. It’s something you might like to consider.

As a side note, thinking about film can help in another way. If you are stuck on a particular scene, run it in your head like a film clip. Then you may easily transcribe what you have just watched. Most of the writing advice that I dispense is shamelessly cadged from greater writers than I. This tiny trick is something I came up with all on my own. I’m stupidly proud of it.

2. Character.

Character is vital, and it’s really where a book should start. You can have the cleverest, most intricate story in the world, but if it is not happening to someone vivid and human it will be flat as twenty-seven squashed pancakes. The reader needs someone to root for. What happens is not the most important thing, it is who it happens to.

So, you have to start the very idea of a book with a strong character. It doesn’t matter how brilliant your plot is, if the reader is not caught by the protagonist, she will not care what happens, even if it involves fireballs and flying spaceships.

Sol Stein once said that when he was an editor and he was sent a manuscript, his first hope was that he would fall in love. This does not mean that the character needs to be lovable. You can create a monster, an anti-hero or heroine. The only thing I would say about that is that it is difficult. It takes a master to persuade the reader to stay with someone loathsome. Dostoevsky did it, and Nabokov, but they were flying at the very top of their game. I’m not suggesting you cop out. If you are fascinated by the ghastly, go with it. But if you want to make your passage into fiction easier, the best approach is to invent someone with whom you can fall in love, just as Stein hoped to. The likelihood then is that the reader will too.

Don’t make the mistake of creating a shining, perfect character. People rarely love the perfect, even if it did exist, which it does not. The very idea of perfection repels; it is distant and impervious. It is up on a high plinth. The moment in High Society when the Grace Kelly character becomes truly lovable is when she says: help me down from my pedestal. The ones people love are usually keenly human: flawed, contradictory, struggling, aware of their own folly.

I do think plot comes from character. You may have a ripping yarn in your head, and that is fine. But normally a plot starts with a human doing something. The woman picked up the ringing telephone; the man tore the bandage from his eyes. It is the person who begins the action and starts the motor of the plot.

If you try to impose a story on a person you have built to fit, the thing will always have an air of bogusness about it. Readers will only ask the what happens next question when there is a living, breathing, believable human in the vortex of all that happening.

And it is the knowledge of your character that will make your plot make sense. If you try to shoehorn a character into your set story, making him do something entirely out of character in the process, the fourth wall is broken, and the suspension of disbelief is lost.

Don’t be afraid of complexity. Humans are contradictory and complex and often hardly explicable. Fictional characters may be as complex as you like, just as real people are, but they should also have a sort of consistency. If you pull a stunt where a protagonist suddenly behaves completely against all previous form, you risk losing your reader. The protagonist may do the unexpected, but there should be a little foreshadowing, so the reader may look back and say: ah, yes, I see.

Characters should always want. The essence of plot is – a protagonist desires something, and has to overcome a series of obstacles to achieve it. The obstacles do not have to be visible or actual even; they can be internal. But they must be there. Kurt Vonnegut said the cleverest thing I ever read about character. He said: ‘Make your characters want something right away, even if it's only a glass of water. Characters paralyzed by the meaninglessness of modern life still have to drink water from time to time.’

I try not to be too prescriptive, because really the only rule of writing is that there is no rule. You only have to read Ulysses to see that. But I do think that you should know your central characters better than you know yourself. It is for this reason that I never base fictional characters on real people. Even if you live with someone for forty years, she will suddenly surprise you. You will never truly know your great-aunt Mabel in the way you know Ethel Sambora, who grew up in the back-streets of Buenos Aires and now breeds chickens just outside Lowestoft, because you made Ethel up, and she is yours.

How you get to know your character depends on you. I live with mine. They are with me when I fall to sleep at night, and with me when I wake. I take them to the supermarket and to do the horse. Some people like to do a strict Paxman-style interview; some people set their characters twenty questions. A really good way to find your characters’ true selves is to put them under extreme pressure; then their inner core is revealed.

If you do not know your characters, your plot will stutter and fail. Learn them, love them, hate them, fight with them. Make them unexpected and eccentric and not quite normal. It helps if they amuse you, because you are going to spend an awful lot of time in their company.

3. The importance of openings.

The start of a book is the most important part of it, and the opening sentence is the crux of that. This is vital for two reasons. One is practical and vulgar. There are thousands of books on the market and people have little time and short attention spans. If you do not get them at Hello, your book will not sell and you will have to eat grass.

In a more high-flown, artistic sense, your opening sentence may perform many creative tasks, sometimes at the same time. It can introduce character, paint a picture, set a tone. It can create a mystery, pose a question, serve up a shock. It should, at the very least, interest and intrigue. I did not use to pay much attention to openings, but just went on instinct. This was a mistake. It is now something of which I am keenly aware.

I remember ages ago being struck by a piece of advice from a clever person whose name I have lost. It went something like this: always start a scene halfway through. The same goes for the beginning of a book. To start a book in a thrilling way, you can plunge straight into the action, the middle of a scene, an act of violence or love or wrenching loss. Trust the reader. You do not have to set the stage, explain things, map out what you are going to do. Let her see it, taste it, feel it, sense it. If there are loose ends, you can loop back later and tie them up. Hit the ground sprinting. The reader will go with you. She is quite brave like that, if she senses she is in safe hands.

Don’t forget that writing, even though it is composed of one-dimensional scratches on a page, is a vivid, visual medium. A good question to ask about openings is: what can the reader see? All the senses may be used: a good opening can invoke smell, taste, touch.

But don’t make promises you can't keep. If you begin on a note of high drama, of intense action, the book cannot then lapse into a dreamy, static examination of the human condition. If you want to write a contemplative book, begin on a contemplative note. That way the reader does not ask for his money back. Never write a cheque you can’t cash. Remember Chekhov’s gun. If you load the gun, and it never goes off, your reader may feel puzzled and short-changed.

Here are some of my favourite opening lines:

It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York.

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

LP Hartley, The Go-Between.

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton.

Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises.

On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about halfway between Marseilles and the Italian border, stands a proud, rose-colored hotel.

Scott Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night.

Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway.

Under certain circumstances there are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea.

Henry James, Portrait of a Lady.

I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills.

Karen Blixen, Out of Africa.

It was clearly going to be a bad crossing.

Evelyn Waugh, Vile Bodies.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice.

In a village of La Mancha,

the name of which I have no desire to recall, there lived not so long ago one of those gentlemen who always have a lance in the rack, an ancient buckler, a skinny nag, and a greyhound for the chase.

Cervantes, Don Quixote

Midway in our life's journey, I went astray from the straight road and woke to find myself alone in a dark wood.

Dante, The Divine Comedy

James Bond, with two double bourbons inside him, sat in the final departure lounge of Miami Airport and though about life and death.

Ian Fleming, Goldfinger

This is the saddest story I have ever heard.

Ford Maddox Ford, The Good Soldier.

This is a tale of a meeting of two lonesome, skinny, fairly old white men on a planet which was dying fast.

Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions.

It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.

Paul Auster, City of Glass.

When Farmer Oak smiled, the corners of his mouth spread till they were within an unimportant distance of his ears, his eyes were reduced to chinks, and diverging wrinkles appeared round them, extending upon his countenance like the rays in a rudimentary sketch of the rising sun.

Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd.

I said an awful lot more. (My poor students. At least there was cake.) I’m not going to write any more now, because I’ve gone on long enough. Also, my fingers are tired.

And here, to reward you after all those damn words, is the now-traditional foal picture. Nine days old today:

July 16, 2013

Writing Workshop, Day Two. The Good Critic and the Bad Critic. Clue: one of them wears a white hat.

I spoke to my group today about the good critic and the bad critic. This idea is closely related to The Fear, of which I wrote yesterday.

I am crazy for utility, as I get older. I really, really like things that work, that have purpose, that do something in the world. I’ve always hated waste, but as I reach middle age and the hours whoosh past my ear, I particularly hate the waste of time. I like utility for many reasons, but one of them is that it saves time.

The good critic has utility. It is the voice of humility, which has a tenderness in it. The good critic, who should arrive, wearing her white hat, when you start on the second draft, says kindly, but very firmly: ‘Well, you are not very good at that, but we’ll work on it.’

The good critic is the one who makes you practice. Just as great musicians still practice their scales and arpeggios before they go out to perform an intricate sonata, so proper writers should practice the basics. Any form of daily writing will do it. I’m afraid I sometimes see this blog as my daily practice. I say afraid, because really it should be a selfless thing, devoted to the Dear Readers. But it builds my muscles; it builds the muscle memory that is needed for writing to stay fluent.

The good critic may say: chapter two does not quite work, or that character is flat on the page, or that passage is overwritten. The good critic does not say these things in glee or malice, but in a spirit of improvement and possibility. The good critic keeps you honest and keeps you grounded. It does not let you float into the fiery heights of hubris.

The good critic comes with a charming suitcase full of solutions. The solutions are not easy. They almost always are: work, and effort. And time too. And dedication and thought and care. Do it again, do it better, think about it harder. Don’t skimp. Don’t think you can cheat your readers, or cheat the process. The process must be honoured, and it is slow. The good critic is not about fleeting tips or quick shortcuts; the good critic has no magic wand. She is quite stern, and she should be.

The good critic is the voice of the possible.

The bad critic has no utility. It is really important that you trust me on this. I know her well, and she is a bitch. She is the wrecking voice of contempt. She smashes and trashes and laughs as she stomps all over your fledgling hopes with her beastly stiletto heels. She will grind you underfoot, if you let her. And then she will bugger off to torment some other innocent.

The bad critic is the bearer of shame. Shame is a wholesale destroyer. It does not say: you are weak at dialogue, so let us work on that. It says: you are entirely hopeless and you could not write fuck on a dusty blind and you should probably not be allowed out in public.

The bad critic is also relentless. It is the voice that never stops. It does not just home in on one area of frailty, but gallops from one field of idiocy to the next. Not only can you not write dialogue, but your office is a mess, your hair is a fright, and you can’t cook. You are too fat, too thin, too boring, too verbose, too shy, too garrulous. Whatever you do, it will be the wrong thing. The bad critic says: you might as well give up, because you will never amount to anything.

The wonderful thing about all this is that you have a choice. You are a sentient adult; you have agency. Every time you hear that barking voice of shame, you may choose to listen to it. If you really want, you can let it in, pull up a chair for it, give it a cocktail, and listen to its screeching song. You can do that. Or, you can say, no thanks, not today. I’m busy, and I’ve run out of gin. So fuck off.

Use whatever strategy suits you best. Sometimes, as you may have gathered, I find excessive swearing helps. You may imagine yourself punching the bad critic in the nose. Whatever gets you through the night.

The bad critic is cunning and invasive as bindweed. It may not be possible to banish the sound of shame from your entire life with one act of will. Like almost anything to do with writing, it involves daily practice, building up that particular muscle set through patient repetition. So you may wish to start small. Just tell it to bash off for half an hour. Promise yourself one single morning, with the door shut, whilst the bad critic hammers fruitlessly at the door. She may soon get bored and leave.

The most important thing to know is that this bad critic will not help your writing in any way. Shutting her out is the most generous thing you can do for yourself. With her in the room, your creative self will never be able to unfurl its wings, and you will never know how high you may fly. And that really is a waste.

You have the power. You have the choice. You can fly, if you let yourself.

No time for pictures again. Just the obligatory foal photograph. Because IT’S A FOAL:

July 15, 2013

Writing: The Fear

I am running a small writing workshop this week. It is a keen pleasure, and it is amazingly hard work at the same time. I sit here now, in the afternoon sun, all energy wiped from me, hardly able to string a sentence together. This is ironic, because all I have been talking about all morning is the art of stringing sentences.

I suspect it is because I am an introvert, so anything which involves a group takes it out of me. I am also ransacking my brain for every single thing I know, every tiny particle of knowledge and experience which may help, every last notion which may provide inspiration. These people can already write. I don’t really need to tell them the technical stuff. They know about semi-colons and rhythms and playing with language. I have to give them something bigger than that.

Mostly, I think, people come to workshops because they have run into the sand. Their inspiration has dried up, their drive stutters and fails. They know they want to write, they know they love to write, and yet they do not write. Why? That is the profound question, and I must scrabble about for answers.

This is why I always start not with structure or narrative or anything concrete or specific, but with the big abstract idea I call The Fear. The Fear is what stops you writing. It may stop you living. The Fear is all the old voices in your head which tell you that you are not good enough, clever enough, interesting enough. You are useless and pointless and feckless, and you should go into the garden and eat worms.

The Fear is mean and ruthless and transforms itself like a shape-shifter. It takes a myriad of forms. It may be the stern schoolmistress who told you that you could not break the rules of grammar, or the recent friend who kindly informs you of the pitfalls of the writing life. It could be your family, who tease you just a little too much. It is the internalised voice from the culture itself, which says that A Writer must be a certain sort of person, from a certain sort of background, with a certain sort of education and a certain sort of brain. This voice, which is bossy and pernicious, may even suggest that A Writer wears a certain sort of clothing. Oh, yes, there is a dress code. This is the voice of the Members Only; the one with the clip-board and the velvet rope, only lifted if you arrive in the company of Tom Stoppard. It is the one that says you have to be on The List.

The Fear callously informs you that even if you can push past all these horrid obstacles, you will still have to face derision. The Fear says that people will laugh and point, that you are running on idiot hubris, that you do not have what it takes. You? With your puny plan and your paltry adjectives and your pathetically limited life experience? Have you stalked big game on the Serengeti, or run from rifle fire in the dust of the Helmand Valley, or penetrated the Hindu Kush? You have neither enough high life or low life. Your life is too small, too ordinary, of no possible interest to man or beast. The Fear says you will fail, and that people will mock, and that those people will be right.

The dangerous aspect of The Fear is that it has a point. You will fail. All writers fail. The pristine prose that exists in your head never quite makes it to the page. The perfect novel that dances in your mind is sullied and trashed by the time you write the opening chapter. Someone very clever once said: after the first page, it’s just damage limitation.

The secret of this is to keep buggering on anyway. I sometimes think what makes a writer is that cussed determination to keep buggering on. The non-writers are the ones who fold. They might be able to write a perfectly lovely sentence, they might have an ear for prose and a feel for language, but they do not persist. Persistence, perhaps, and cussedness and doggedness and a refusal to be beaten, are the marks of those who go on to write.

And The Fear is right in another aspect. People will laugh and point. Until you are published, they may find your ambitions risible. ‘Ah, your writing,’ they may say, in a special voice. Even after you are published, there will still be pointing and scoffing. No matter how hard you work or how talented you are, some people just won’t like what you have produced, in the same way that some people don’t like artichokes or loathe lentils.

The secret to this is (as you may have guessed by now) to keep buggering on anyway. You can’t stop the laughing and pointing; you cannot convince critics out of their mockery. You can arm yourself, however. There is no magical thick skin which can be grown to resist the slings and arrows, but you can learn how to absorb them, and carry on. You can factor them in. You can learn to roll with the punches, but don’t think for a moment there will be no punches.

So that was today’s theme.

Ah, The Fear, I think, as I sit to write this. My old, old friend. I’ve bashed through a bit of it, after all these years. I have given myself permission to be a writer, which was initially troublesome. I came from a house of horses; the bookshelves were filled with old copies of Timeform, the tables littered with The Sporting Life, not the London Review of Books. There were no poets holding forth in the kitchen, but people discussing what would win the 3.30 at Newton Abbot.

I got over that, after a few years of practice. I still fear the not being good enough. I can carry a tune, make a paragraph dance off the page, if the light is coming from the right direction. Yet I still have to struggle incredibly hard with narrative. Even after all this damn practice, my narrative drive is pathetically weak. I’m good at dialogue but appalling at story structure. I have to work very hard at absorbing failure, which is a mangy hound trotting and snapping at my heels. The discipline and management of time needed to write 90,000 words, and then rewrite them and rewrite them again, is still a daily challenge. I have about six different ideas jostling in my head at any one time, and I can’t get them all organised. Some will never see the light of day. Criticism can send me into a spiral of self-loathing, and hurts like a physical thing. I learnt to talk myself down off the ceiling, but I have never caught the trick of not hitting the ceiling in the first place.

But I am pretty good at buggering on. It’s a learnt skill, and a good one. You can’t wish The Fear away, I have discovered. You cannot make it dissipate through a sheer act of will. You have to stare at the whites of its mean old eyes, and bash on through. With writing, and with life, perhaps.

No time for pictures today. Just one shot of the little HorseBack foal, who is now a week old and growing bonnier and sweeter and stronger and more antic by the day: