Eoin Stephens's Blog, page 3

April 30, 2024

Robert Emmet

Born into a Protestant Ascendancy family, Emmet was influenced by his father’s support for American independence and friendships with Irish patriot leaders like Wolfe Tone. Emmet excelled in academics and oratory at Trinity College Dublin, where he engaged in political discussions. After exposure as a United Irishmen supporter, he withdrew from Trinity but later became involved in rebuilding the organization’s military structure.

Emmet’s early life was privileged, but his commitment to Irish independence led him to take drastic action. His belief in the people’s right to representation and reform, combined with disillusionment with British rule, fueled his revolutionary zeal. Despite suspicions of manipulation by political elites and setbacks in securing foreign support, Emmet pressed ahead with his plans for rebellion.

Emmet’s Proclamation of the Provisional Government urged the Irish people to assert their independence without relying on foreign aid, emphasizing the need for self-reliance. The document outlined a broad political agenda that included not only democratic reform but also the abolition of tithes and the nationalization of Church of Ireland land. Despite its universal appeal across class and religious lines, only two copies of the proclamation are known to survive, as the government sought to suppress its distribution.

The 1803 uprising led by Emmet was marred by setbacks and failed to achieve its objectives. Poor planning and premature actions prevented the rebels from executing their plan to surprise Dublin Castle. Emmet’s forces were outnumbered and ill-equipped, and the uprising quickly fizzled out. Sporadic clashes ensued, resulting in casualties on both sides, including the stabbing of Lord Chief Justice Lord Kilwarden.

Emmet’s capture followed, and he was tried and convicted for high treason. Despite overwhelming evidence against him, Emmet refused to offer a defence, choosing instead to make a poignant closing statement from the dock. His eloquent speech and defiant demeanor left a lasting impression on many, including Chief Justice Lord Norbury and even the Chief Secretary for Ireland, William Wickham.

Emmet’s execution on September 20, 1803, marked the end of his tumultuous journey. His remains were initially buried in a Dublin hospital’s burial ground, but family tradition holds that they were later re-interred in the family vault. Emmet’s legacy endured, with poets like Percy Bysshe Shelley immortalizing his memory in verse and highlighting his role as a martyr for Irish independence.

Despite the failure of his uprising, Emmet’s unwavering commitment to the cause of Irish nationalism inspired future generations to continue the struggle for independence. His name became synonymous with the resilience and determination of the Irish people in their quest for self-determination.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

William of Orange

William III, Prince of Orange, was born in November 1650, just eight days after his father, William II, passed away. Despite being the son of royalty, William faced political hurdles from the start due to the Act of Seclusion in 1654, which barred him and his descendants from holding office in the Netherlands. In 1672, amidst the threat of invasion by France and England, he was appointed as captain general, tasked with defending the Netherlands during a tumultuous time. Despite initial setbacks, William’s leadership during the crisis earned him popular support, leading to his appointment as stadholder and captain general.

His reign was marked by military campaigns against France, where he orchestrated alliances with unlikely allies such as Pope Innocent XI to counter Louis XIV’s expansionist ambitions. In 1677, William married his cousin Mary, which strengthened his position in England. Eventually, he intervened in English affairs when James II’s rule provoked public outcry amongst Protestants, leading to the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. William and Mary took the English throne, solidifying Protestant governance.

William’s reign saw domestic and foreign challenges, including conflicts in Scotland and Ireland. He faced criticism for his handling of the Glen Coe massacre in Scotland and the Irish war, but his campaign here secured Ireland for the Protestant settlers. The Battle of the Boyne, fought on July 1, 1690, pitted King William III against the exiled King James II in Ireland. James sought to reclaim his throne through an alliance with Ireland and France, but William’s victory reassured his allies of his commitment to counter French-aligned forces. The battle, although not decisive, marked a turning point in the conflict.

The Williamite victory in Ireland had lasting effects. It ensured James II wouldn’t regain his thrones by force and solidified British Protestant dominance over Ireland, leading to the “Protestant Ascendancy” rule. Irish Catholics maintained loyalty to the Jacobite cause, viewing James as their rightful monarch promising self-government and Catholic tolerance. Many Irish soldiers fought for the Stuarts abroad. The war saw Irish Protestants rise in the British army’s officer ranks. Protestants celebrated the Williamite victory as a win for liberty, depicted in murals in Ulster and commemorated by Protestant Unionists on the Twelfth of July through events like those held by the Orange Order.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

Bono

Bono, born in Dublin, Ireland, on May 10, 1960, is renowned as the lead singer of the globally acclaimed rock band U2 and for his activism in human rights causes.

Raised by a Catholic father and a Protestant mother who passed away when he was just 14, Bono’s upbringing was marked by a blend of faiths. In 1977, he, along with David Evans (later known as “the Edge”), Larry Mullen Jr., and Adam Clayton, formed U2.

U2’s breakthrough came in 1983 with “War,” followed by even greater success with “The Unforgettable Fire” in 1984. Bono’s star turn for Band Aid seemed to inspire the band to take an interest in human rights activism. They joined the “Conspiracy of Hope” tour in 1986, organized by Amnesty International USA. Bono’s experiences in war-torn Nicaragua and El Salvador further fueled his interest in global issues.

U2’s album “The Joshua Tree” (1987) became a monumental success, ranking 26th in Rolling Stone magazine’s list of top 500 albums of all time. Over the years, U2 continued to produce chart-topping albums, including “How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb” (2004) and “Songs of Experience” (2017), solidifying their status as one of the most influential bands of all time. Their activism also earned them numerous accolades, including more than 20 Grammy Awards and a Kennedy Center Honor in 2022.

Outside of music, Bono embarked on a second career as a global activist. In 2002, he co-founded Debt, AIDS, Trade, Africa (DATA), an organization dedicated to eradicating poverty, hunger, and AIDS in Africa through advocacy and partnerships. Despite criticism for his willingness to collaborate with leaders like President George W. Bush, Bono remained committed to securing funding for AIDS programs and debt relief for impoverished African nations.

Although Bono’s activism became less visible during the 2010s, he continued to work behind the scenes to advocate for global issues. Around the same time, the band were criticised for avoiding tax. The bands license their copyright to companies that they set up in the Netherlands, which in turn license it to companies in other countries. While the Netherlands companies receive the bands’ global royalties, they only pay tax on what is earned in the Netherlands itself, allowing the groups to cut their tax bills.

In 2022, he released his memoir, “Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story,” reflecting on his journey as both a musician and an activist. Bono’s enduring impact as a musician and a humanitarian underscores his commitment to using his fame for positive change on a global scale.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

April 29, 2024

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O’Connell, born in 1775 in County Kerry, Ireland was the preeminent Irish figure of the 19th century. After leaving the Roman Catholic college at Douai due to the French Revolution, O’Connell pursued law studies in London, where he was called to the Irish bar in 1798. Despite his early involvement with the Society of United Irishmen, a revolutionary group, he abstained from participating in the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and was vocally hostile to it.

The Act of Union in 1801, which dissolved the Irish Parliament, prompted O’Connell to demand the repeal of anti-Catholic laws by the British Parliament to validate its representation of Ireland. He opposed several Catholic relief proposals from 1813 onwards, fearing that they would grant the government veto powers over Catholic bishoprics in Britain and Ireland. Despite the illegality of permanent Catholic political organizations, O’Connell organized mass meetings across Ireland to advocate for Catholic emancipation.

In 1823, O’Connell and Richard Lalor Sheil founded the Catholic Association, gaining support from the Irish clergy, educated Catholic laymen, and lawyers. The Association’s membership grew rapidly, making it difficult for the government to suppress it. In 1828, O’Connell, though ineligible to sit in the House of Commons as a Catholic, won the County Clare election, pressuring the British Prime Minister, Arthur Wellesley, to concede to Catholic emancipation. Following the passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829, O’Connell took his seat in Westminster.

In 1835, O’Connell played a role in toppling Sir Robert Peel’s Conservative ministry and entered the “Lichfield House compact” with the Whig Party leaders, promising a period of calm in Ireland in exchange for reform measures. His support, along with his Irish followers known as “O’Connell’s tail,” helped keep the Whig administration in power until 1841. However, disillusioned by the Whigs’ limited efforts for Ireland, O’Connell founded the Repeal Association in 1840, aiming to dissolve the Anglo-Irish legislative union.

O’Connell’s campaign for repeal culminated in his arrest for seditious conspiracy in 1843, following a series of mass meetings across Ireland. Although he was released on appeal after three months’ imprisonment, his health deteriorated rapidly afterward, and leadership of the nationalist movement passed to the Young Ireland group.

Daniel O’Connell’s legacy as a pioneering Irish nationalist leader endures, marked by his advocacy for Catholic emancipation and his efforts to repeal the Act of Union between Britain and Ireland. His opposition to violence and slavery distinguished him from some of his nationalist successors however his vision of an explicitly Catholic Irish identity has aged less well.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

Éamon de Valera

Eamon de Valera played a pivotal role in shaping Ireland’s history during the 20th century. Born in New York City in 1882 to a Spanish father and an Irish mother, de Valera was sent to County Limerick, Ireland, at a young age after his father’s death. He received his education in Ireland, eventually becoming a mathematics teacher and a fervent supporter of the Irish-language revival.

De Valera’s involvement in Irish politics began in 1913 when he joined the Irish Volunteers, a group organized to resist British opposition to Home Rule for Ireland. He gained prominence during the Easter Rising of 1916, commanding an occupied building and becoming the last commander to surrender. Due to his American birth, he escaped execution but was sentenced to penal servitude.

After his release in 1917, de Valera was elected president of Sinn Féin and led the party to a landslide victory in the 1918 general election. Controversially, he travelled to America during the Irish War of Independence and delegated the ceasefire negotiations with Britain to others, allowing him to ultimately reject the treaty that established the Irish Free State.

De Valera’s political career continued as he led the opposition to the Irish Free State government during the civil war. Despite imprisonment, he organized the Fianna Fáil party, which entered Dáil Éireann in 1927, advocating for the abolition of the oath of allegiance and other changes.

In 1932, Fianna Fáil defeated the incumbent government, and de Valera became Taoiseach. During his time in office, he focused on severing connections with Britain, withholding payment of land annuities and engaging in a disastrous “economic war” to achieve national self-sufficiency.

In 1937, de Valera oversaw the ratification of a new constitution that transformed the Irish Free State into Ireland, a sovereign and independent democracy. He also negotiated the Anglo-Irish defence agreement, ensuring Ireland’s neutrality during World War II while providing covert assistance to the Allies.

De Valera’s political dominance continued until 1948 when opposition parties formed a coalition government. However, he returned to power in 1951 and served multiple terms as Taoiseach and President of Ireland until his retirement in 1973. His tenure is associated with extreme social conservatism, reactionary fiscal policies and docility to the Catholic church. He passed away in 1975, leaving behind a legacy as the dominant figure of mid-20th century Ireland.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

James Connolly

James Connolly was an Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader who played a significant role in the 1916 Easter Rising against British rule in Ireland, ultimately being executed for his involvement. Born in Scotland in 1868 to Irish parents, Connolly became involved in socialism and moved to Ireland in 1896, where he established the country’s first socialist party, advocating for Irish independence from both British rule and British capitalism.

Connolly’s early life was marked by hardship and military service, but he eventually found his calling in socialist activism. His involvement in the Dublin lock-out of 1913 and his leadership in the ICA exemplified his commitment to workers’ rights and Irish independence.

From 1905 to 1910, Connolly organized for the Industrial Workers of the World in the United States, focusing on syndicalism over doctrinaire Marxism. Upon his return to Ireland, he worked alongside James Larkin in organizing the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

Connolly’s efforts to unify Protestant and Catholic workers in Belfast were unsuccessful, but the 1913 industrial unrest in Dublin provided a new avenue for his socialist vision. He committed the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a union militia, to support the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s plans for an insurrection in 1916.

In the lead-up to the Easter Rising, Connolly’s support for armed resistance against British rule intensified. He played a crucial role in planning and executing the rebellion, despite disagreements with other leaders over strategy and tactics.

During the Easter Rising, Connolly commanded the ICA from the General Post Office in Dublin. Despite being wounded, he played a significant role until the rebels surrendered. Alongside six other leaders, he was executed for his part in the rebellion.

Following the failure of the uprising and his subsequent execution, Connolly became a symbol of resistance and martyrdom for Irish nationalists. His death, along with other rebel leaders, sparked outrage and condemnation both in Ireland and abroad, ultimately contributing to a shift in public opinion towards independence.

Connolly’s legacy has been contested, claimed by various political factions in Ireland, including Communist and Labour parties, as well as the Provisional Republican movement. Throughout his life, he maintained connections to both Scotland and Ireland, embodying a unique blend of Irish nationalism and international socialism.

Despite his controversial reputation and the ongoing debates over his legacy, James Connolly remains an iconic figure in Irish history, revered for his unwavering dedication to the cause of Irish freedom and social justice.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland until his death in 1658. Often characterized as ruthless, he led successful efforts to remove the British monarch from power, earning him the label of a dictator. Cromwell, a devout Puritan, harbored strong intolerance towards Catholics and Quakers, yet some credit him with steering Great Britain towards constitutional governance.

Born into wealth in 1599 near Cambridge, Cromwell married into a Puritan family and later joined the sect. Despite his political success, he faced financial troubles and struggled with depression. Cromwell entered Parliament in 1628, but King Charles I’s suspension of the legislative body in 1629 cut short his tenure until it reconvened in 1640 due to rebellion.

The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 thrust Cromwell into military leadership despite lacking formal training. He distinguished himself in battles like Edgehill and Naseby, rising to prominence within the Parliamentarian forces. His religious fervour and belief in divine support fueled his actions, including the harsh siege of Catholic stronghold Basing House.

After Parliament’s victory in the First English Civil War, Cromwell negotiated unsuccessfully with Royalists, leading to the outbreak of the Second Civil War in 1648. Following the decisive Parliamentarian win, Cromwell played a key role in the execution of Charles I during Pride’s Purge, leading to a shift in Parliament’s composition.

Cromwell’s military campaigns extended to Ireland, where his forces engaged in brutal massacres at Drogheda and Wexford, leading to the confiscation of Catholic-owned land and persecution of Irish Catholics.

In March 1649, Westminster appointed Oliver Cromwell to lead an invasion of Ireland in order to crush all resistance to the new English Commonwealth and to avenge the alleged massacres of Protestant settlers in 1641-2. Irish land was also a valuable commodity, almost 70% of which was still held by Catholic landowners. Cromwell arrived in August, with 12,000 troops and a formidable train of siege artillery. Over the next four years his army defeated most military opposition in a series of bloody sieges and battles, which included notorious massacres at Drogheda and Wexford in late 1649. Catholic Irish resistance proved very stubborn and the English army resorted to scorched earth tactics to deny the enemy any sustenance or shelter. Between 1650 and 1652 Ireland suffered a demographic disaster with at least 25% of the population dying as a result of deliberately induced famine, which also encouraged the spread of diseases such as dysentery and the plague.

By 1653, when the last formal surrenders of the war took place, the country had been devastated, the population decimated, the economic infrastructure destroyed.

Cromwell’s death in 1658 paved the way for his son Richard to assume power briefly, but his lack of support led to his resignation. George Monck’s actions initiated the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, with Charles II ascending the throne. Cromwell’s posthumous fate saw his body exhumed, beheaded, and displayed, symbolizing the triumph of the monarchy over his republican ideals.

Are you enjoying Stair Wars? If so, you might like some of my other products. Visit the shop here.

April 26, 2024

Grace O'Malley

Gráinne O’Malley, also known as Grace O’Malley, was a formidable figure in 16th-century Irish history, renowned for her leadership of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland. Born around 1530 into a seafaring clan in Clew Bay, County Mayo, she inherited her father’s leadership role upon his death, despite having a brother. Her marriage to Dónal Ó Flaithbheartaigh enhanced her wealth and influence, establishing her as a significant figure in Irish society.

O’Malley’s life is mostly documented through English sources, particularly in records related to her interactions with Queen Elizabeth I. In Irish folklore, she is celebrated as Gráinne Mhaol, the fearless “Pirate Queen.” Her early years were marked by a desire for adventure, exemplified by her determination to join her father on trading expeditions despite societal norms.

Marriage played a significant role in O’Malley’s life. Her union with Dónal Ó Flaithbheartaigh connected two powerful families and bore three children. However, her husband’s ambitions were thwarted, leading to his assassination. After his death, O’Malley returned to her lands and remarried Richard Bourke, further consolidating her influence.

O’Malley’s reputation as a fierce leader grew with her actions against rival clans and English encroachment. She defended her territories, even attacking Doona Castle to avenge her lover’s death. Despite facing opposition, she maintained an autonomous status, engaging in diplomatic negotiations with the English crown to secure her family’s release from captivity.

Her most famous encounter was with Queen Elizabeth I, whom she petitioned for the release of her sons and brother. The meeting, surrounded by courtiers and guards, has been embellished in folklore, depicting O’Malley as a proud and independent figure who refused to bow before the English queen.

Despite initial resistance from English officials, O’Malley’s persistence paid off when Queen Elizabeth ordered the release of her family members and granted her lands and protection. However, ongoing conflicts with English authorities and internal strife within Ireland continued to challenge her authority.

In her last years, O’Malley faced increasing pressure from English governors like Sir Richard Bingham, leading her to seek refuge in Munster and petition further assistance from English officials. As the Nine Years’ War escalated, she aligned herself with the English crown, urging her son to fight against Irish lords in support of the Crown.

The exact details of O’Malley’s death remain uncertain, with conflicting accounts placing it around 1603, the same year as Queen Elizabeth’s demise. However, her legacy as the Pirate Queen of Ireland endures, immortalized in folklore and historical accounts as a symbol of Irish resilience and defiance against foreign rule.

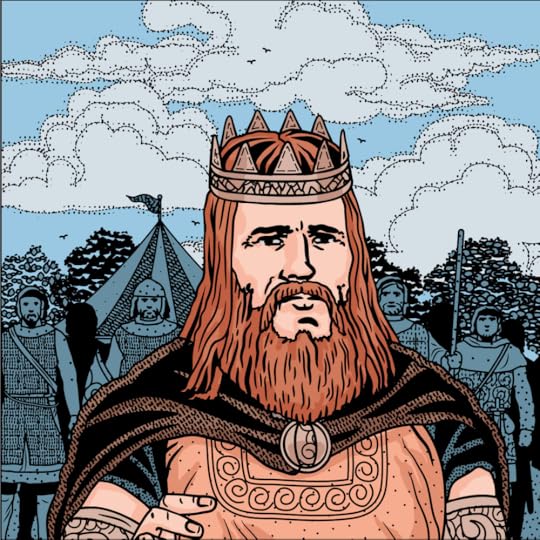

Brian Boru

Brian Boru was born around 941. He hailed from the Dál gCais dynasty and became renowned for ending the Uí Néill dominance over the High Kingship of Ireland. Boru’s rise to power was marked by strategic alliances, military campaigns, and political maneuvering that ultimately solidified his position as one of Ireland’s most successful monarchs.

Initially, Boru focused on consolidating power within his home province of Munster, following the footsteps of his father and elder brother. His military prowess and diplomatic skills enabled him to extend his influence over neighboring regions, culminating in his ascension to the High Kingship of Ireland in 1002. Boru’s reign ushered in a period of relative stability, marking the decline of Viking invasions and the assertion of Irish sovereignty.

Throughout his reign, Boru faced numerous challenges, including resistance from rival Irish kings, particularly in Leinster and Ulster. However, his adept leadership and military acumen allowed him to quell dissent and expand his authority. Boru’s determination to unite Ireland under a central monarchy led to extensive military campaigns, including two full circuits of the island in 1005 and 1006, demonstrating his unwavering commitment despite his advancing age.

Boru’s vision of a unified Ireland extended beyond mere military conquests. He strategically aligned himself with influential institutions such as the Church, particularly the monastery of Armagh, to solidify his legitimacy as High King. By leveraging religious authority and patronage, Boru sought to establish a new form of kingship modeled after European monarchies, thereby centralizing power and diminishing regional autonomy.

However, Boru’s aspirations faced significant opposition, notably from rebellious factions in Leinster led by Máel Mórda mac Murchada. The ensuing conflict escalated into the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, a watershed moment in Irish history. Despite emerging victorious in the battle against Leinster and Viking forces, Boru was himself killed, marking the end of an era.

Boru’s legacy remains ingrained in Irish folklore and historiography, celebrated for his role in unifying Ireland and thwarting external threats. His strategic foresight, military prowess, and political astuteness continue to inspire admiration and debate among scholars and enthusiasts alike.

The Battle of Clontarf, while heralded as a triumph for Irish unity, also underscored the complexities of medieval Irish politics and the enduring legacy of regional rivalries. Boru’s death, though a blow to his supporters, did not diminish his impact on Irish history. Instead, it paved the way for subsequent rulers to navigate the intricate web of alliances and conflicts that defined medieval Ireland.

In death, Boru transcended mere historical figurehead status, becoming a symbol of Irish resilience and perseverance. His burial in Armagh and the enduring legends surrounding his life serve as a testament to his enduring legacy as one of Ireland’s most iconic leaders.

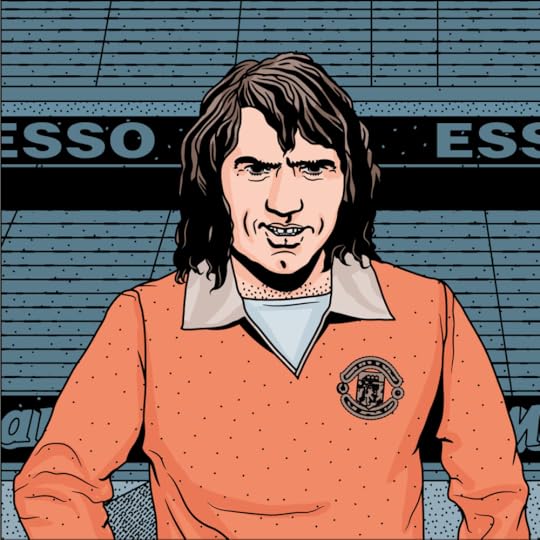

George Best

George Best (22 May 1946 – 25 November 2005) was a Northern Irish professional footballer who played as a winger, spending most of his club career at Manchester United. A skillful dribbler, he is considered one of the greatest players of all time. He was named European Footballer of the Year in 1968 and came fifth in the FIFA Player of the Century vote. Best received plaudits for his playing style, which combined pace, skill, balance, feints, goalscoring and the ability to get past defenders. His style of play captured the public’s imagination, and in 1999 he was on the six-man short-list for the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Century. He was also an inaugural inductee into the English Football Hall of Fame in 2002.

Born in Belfast, Best began his club career in England with Manchester United, with the scout who had spotted his talent at the age of 15 sending a telegram to manager Matt Busby which read: “I think I’ve found you a genius”. After making his debut at age 17, he scored 179 goals in 470 appearances over 11 years and was the club’s top goalscorer in the league for five consecutive seasons.[5] He won two League titles, two Charity Shields and the European Cup with the club. He was an immediate sensation, scoring acrobatic goals and helping United to a league title in his second season. He led the club to another league championship during the 1966–67 season. In 1968 he helped United become the first English club to win the European Cup. Best scored a total of 178 goals in his 466 career games with United.

In international football, Best was capped 37 times for Northern Ireland between 1964 and 1977. A combination of the team’s performance and his lack of fitness in 1982 meant that he never played in the finals of a major tournament. He considered his international career as being “recreational football”, with the expectations placed on a smaller nation in Northern Ireland being much less than with his club. He is regarded as one of the greatest players never to have played at a World Cup. The Irish Football Association described him as the “greatest player to ever pull on the green shirt of Northern Ireland”.

Called the “Fifth Beatle,” the handsome Best had long hair that was an anomaly among footballers but was reminiscent of the “mop tops” of England’s preeminent rock and rollers, the Beatles. Like them, Best was a colossal celebrity. His fame transcended the football world—Best was the first of many footballers to become a regular subject of the British tabloids—but it also helped foster a drinking problem that would prove to be his undoing. After a bitter departure from United in 1974, he played for numerous lesser teams in Britain, Spain, Australia, and the United States until 1983. His drinking continued to affect his play, however, and he became as well known for his squandered talent as for his undeniable brilliance. Best underwent a liver transplant in 2002 but ultimately was unable to overcome his alcoholism, and he died from a series of transplant-related infections that his compromised immune system could not combat.