Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 16

February 28, 2021

Historical mysteries, adventure tales, and books inspired by them

She by H. Rider Haggard

She by H. Rider HaggardMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

I read this book twice when I was at school, and thought it the best book by H. Rider Haggard that I had read. Reading it again as an adult I could remember little but the horrible end of the eponymous "She", but as I read through it I wondered how it was that I remembered it with such fondness, because there were long passages of religious and quasi-philosophical reflection that must surely have been boring to a child. The actual adventure is mainly in the last 50 pages or so.

Part of the appeal, for me at least, lies in the setting, the meta-story, as it were, which involves a historical mystery. Horace Holly, a Cambridge don, is asked by a dying friend to be guardian of his young son, Leo Vincey, and is given a box to be opened on Leo's 25th birthday. The box contains the story of Leo's descent from an ancient Egyptian priest, and a love triangle that results in his death at the hands of a mysterious woman living somewhere in central Africa.

Part of the appeal, for me at least, lies in the setting, the meta-story, as it were, which involves a historical mystery. Horace Holly, a Cambridge don, is asked by a dying friend to be guardian of his young son, Leo Vincey, and is given a box to be opened on Leo's 25th birthday. The box contains the story of Leo's descent from an ancient Egyptian priest, and a love triangle that results in his death at the hands of a mysterious woman living somewhere in central Africa. As a result Holly and Leo Vincey travel to central Africa in the hope of solving the historical mystery, using clues scrawled on an ancient potsherd in ancient Greek. I suppose that it was enjoying such stories as a child that gave me a taste for history and historical research, so that I still enjoy solving the puzzles one encounters in family history and other historical research, where each mystery solved leads to a fresh mystery that seems to defy solution. And I suppose that is why I still enjoyed this book several decades later.

And such stories of ancient mysteries leading to modern adventures still seem to appeal to later tastes, as the series of Indiana Jones films produced about a century later shows.

View all my reviews

But, as many books do, this one sparked off thoughts that go beyond a mere review. In this case it led me to wonder whether C.S. Lewis had read She, and whether it had given him some inspiration in writing The Magician's Nephew, which is now next on my re-reading list.

But, as many books do, this one sparked off thoughts that go beyond a mere review. In this case it led me to wonder whether C.S. Lewis had read She, and whether it had given him some inspiration in writing The Magician's Nephew, which is now next on my re-reading list. The bit about The Magician's Nephew was sparked off by reading this passage, in which She proposes to marry Leo (whom she confuses with his remote ancestor Kallikrates), go with him back to England, and make him king and herself queen:

“But we have a queen already," broke in Leo, hastily. “It is naught, it is naught,” said Ayesha ; "she can be overthrown."

At this we both broke out into an exclamation of dismay, and explained that we should as soon think of overthrowing ourselves.

“But here is a strange thing,” said Ayesha, in astonishment -- "а

queen whom her people love! Surely the world must have changed since I dwelt in Kôr."

Again we explained that it was the character of monarchs that had changed, and that the one under whom we lived was venerated and beloved by all right-thinking people in her vast realms. Also, we told her that real power in our country rested in the hands of the people, and that we were in fact ruled by the votes of the lower and least educated classes of the community.

“Ah,” she said, "a democracy -- then surely there is a tyrant, for I have long since seen that democracies, having no clear will of their own, in the end set up a tyrant, and worship him.

“Yes,” I said, " we have our tyrants.

“Well," she answered resignedly, we can at any rate destroy these tyrants, and Kallikrates shall rule the land.”

I instantly informed Ayesha that in England "blasting" was not an amusement that could be indulged in with impunity, and that any such attempt would meet with the consideration of the law and probably end upon a scaffold.

"The law," she laughed with scorn -- "the law! Canst thou not understand, O Holly, that I am above the law, and so shall Kallikrates be also ? All human law will be to us as the north wind to a mountain. Does the wind bend the mountain, or the mountain the wind ?

This appears very similar to the attitude of Jadis, the former Queen of the dead world Charn, when she comes to England, and later to Narnia.

And I suppose I was inspired by reading books like this as a child to incorporate the trope of ancient mysteries inspiring or contributing to modern adventures into my own story The Year of the Dragon, where I used the legend of Lobengula's treasure in a similar way.

In this case, the real life event was a story found in the archives about John Jacobs. In 1908 Jacobs persuaded Susman, a Jewish trader at Lialui, and later of Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia, to search for Lobengula's treasure in Portuguese territory. Susman said after travelling for 3 months, Jacobs became more and more hazy about their goal. Eventually Susman flogged Jacobs, and was fined in court. Jacobs was deported from Northern Rhodesia in 1909. Then Jacobs persuaded Samuel Brander (the founder of the Ethiopian Catholic Church in Zion) to go on a similar treasure hunt, and they travelled there in 1917, but left without finding any treasure. On the way back Jacobs was arrested in Southern Rhodesia and charged under the immigration laws This story is found in a Memorandum from the Secretary for Native Affairs in Livingstone, dated 5 Aug 1917, in the Tshwane Archives Depot at NTS 1420 5/214.

In this case, the real life event was a story found in the archives about John Jacobs. In 1908 Jacobs persuaded Susman, a Jewish trader at Lialui, and later of Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia, to search for Lobengula's treasure in Portuguese territory. Susman said after travelling for 3 months, Jacobs became more and more hazy about their goal. Eventually Susman flogged Jacobs, and was fined in court. Jacobs was deported from Northern Rhodesia in 1909. Then Jacobs persuaded Samuel Brander (the founder of the Ethiopian Catholic Church in Zion) to go on a similar treasure hunt, and they travelled there in 1917, but left without finding any treasure. On the way back Jacobs was arrested in Southern Rhodesia and charged under the immigration laws This story is found in a Memorandum from the Secretary for Native Affairs in Livingstone, dated 5 Aug 1917, in the Tshwane Archives Depot at NTS 1420 5/214.And it was just such stories that authors like Rider Haggard used as triggers for adventure. John Jacobs was doubtless a con man, but the fantasies of con men can lead to interesting adventure stories.

February 17, 2021

Historical novel and fantasy subgenre

The Golden Horde by Peter Morwood

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I bought this book cheap on a sale 21 years ago and never read it because when I got home I discovered that it was part of a series, and we did not have the first two parts. Then, with the library closed because of Covid, I took it off the shelf where it had sat all these years, and discovered that it is a mixture of two genres -- the historical novel and the fantasy/fairy story. As most of my attempts to write fiction have been in the same sub-genre, and the one I've been writing most recently has a similar setting, I thought it was time I read it if only to see how someone else handles that particular genre, and how they handle similar tropes.

The Golden Horde is set in Russia in the 13th century, in the time of the Mongol invasions, and to begin with I did not like it very much and nearly abandoned it after the first couple of chapters, but then it seemed to improve. There are references to the preceding volumes in the series, which I still don't have, but it stands up quite well as a stand-alone story.

So much for my actual review of the book -- to say much more would reveal too much of the plot, so if you haven't read it and might want to, stop reading here.

I didn't much like the way Peter Morwood handled some of the historical figures mentioned, and some of the tropes. Perhaps that is prejudice on my part; for example, as an Orthodox Christian I was sorry that he had nothing good to say about St Alexander Nevsky. Now Alexander Nevsky is not my favourite saint, mainly because, as a pacifist, I am not drawn to soldier saints very much, or at least I am more drawn to the ones who, like St Martin of Tours, became conscientious objectors. But the Orthodox Church is not a "peace church" like the Quakers and the Mennonites. It has as both soldier saints and peacenik saints. And in the times in which St Alexander Nevsky lived, it was almost impossible for anyone in political leadership not to be drawn into wars. But Peter Morwood seems to think that sorcery is the better option, and his portrayal of St Alexander Nevsky is entirely negative.

In other tropes, however, there is a hint of the Inklings, especially the novels of Charles Williams and C.S. Lewis in his novel That Hideous Strength. Batu, Khan of the Golden Horde, collects the crowns of the Russian princes he conquers. Those who surrender hand over their crowns voluntarily, in acknowledgement that henceforth they rule at the Khan's pleasure. Those who do not surrender their crowns have them taken by force. And the accumulation of crowns represents a dangerous accumulation of power, which irrupts into the world in Charles Williams fashion when a group of Russian nobles decide to offer a sacrifice to Chernibog, an old Russian pagan god.

To counter this, the Princess and sorceress Mar'ya Morevna uses her grimoire to summon Byelobog, the white god of ancient Russia. As Morwood describes it:

To the Tatars, that was Tangri the Eternal Blue Sky fighting Erlik Khan with his thunderbolt, though Ivan knew there was at least one old servant who had come with him down from Khorlov who would see Othinn or Thorr wielding spear or hammer against their old adversary Jorungandr the Midgarth-serpent. To some of the Russians, it would be Byelobog struggling with Chernobog, but the rest would see the Archangel Mikhail come to do battle against the darkness and the old serpent, not for them alone, but for all thee wide white world.

... echoes of the scene in That Hideous Strength where the gods of the planets descended on Belbury, where all the evil in Thulcandra has gathered.

February 5, 2021

Enid Blyton and the "Famous Five"

Five Go to Demon's Rock by Enid Blyton

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

This book has all the usual Enid Blyton trade marks -- a superfluity of exclamation marks, stilted and unconvincing dialogue, and an adventure that doesn't begin until two-thirds of the way through the book. It also, however, has a weak and unconvincing plot.

So why did I buy it and read it?

We went to the library last Tuesday and it was closed -- a member of staff had tested positive for Covid-19, so all the rest of the staff were in quarantine. So we went to a second-hand bookshop to get something to read. I found a few books, and then asked for their children's book section, but they only pointed me to a teenage books section. Then when I was paying for the other books, I saw this one in a pile on the counter, and picked it up. The woman in front of me in the queue said, "Ah, Enid Blyton, the Famous Five and the Secret Seven" and that started a conversation with a couple of staff members as well, who also recalled the Famous Five and the Secret Seven.

And I wondered about that. As a child, I read and enjoyed some books by Enid Blyton, but the Famous Five and the Secret Seven were not among them. I had read one or two Famous Five books and found them boring and unmemorable, and did not read any more. Now, as an adult, I bought this book mainly to see what the appeal was. And this one had all the faults of Enif Blyton's writing with none of the good points of her better children's adventure stories, like The Secret of Kilimooin and The Mountain of Adventure.

And I wondered about that. As a child, I read and enjoyed some books by Enid Blyton, but the Famous Five and the Secret Seven were not among them. I had read one or two Famous Five books and found them boring and unmemorable, and did not read any more. Now, as an adult, I bought this book mainly to see what the appeal was. And this one had all the faults of Enif Blyton's writing with none of the good points of her better children's adventure stories, like The Secret of Kilimooin and The Mountain of Adventure.Arthur Ransome wrote some children's stories where the "adventure" was simply going and camping out on their own, so the adventure in this case, the children's encounter with some criminals, need not necessarily be the main part of the story, but even the camping part Arthur Ransome wrote so much better. He even, sometimes, included encounters with criminals, for example in The Big Six. But in this one the story was weak, and I didn't much like the characters either.

I bought this one, therefore, partly to see why I hadn't much liked the Famous Five as a child, and to see why the Famous Five were the first thing most people thought of if you mentioned Enid Blyton, or even children's adventure stories in general. And this one was a long way from being among the best of children's adventure stories, and also a long way from being among the best of Enid Blyton's ones.

The other reason for reading this one now is that I wrote a children's adventure story, which some reviewers compared with the Famous Five, and I rather hope that mine was a bit better than this one.

February 3, 2021

The REAL Benedict option

In This House of Brede by Rumer Godden

In This House of Brede by Rumer GoddenMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

When I started reading this book, I did not expect it to be so good. But when bookshops and libraries were closed during the Covid lockdown I began making a list of books on our shelves that I had not read. I don't even know how this one got there -- I think it may have been one I inherited when my mother died. Bit I had no hesitation in giving it five stars.

It's about a fictitious Benedictine monastery in England, and gives what seems to me a remarkably accurate picture of Christian monastic life. I knew some things about Benedictines. I knew a few people who had entered Benedictine monasteries, but found the monastic life wasn't for them. I have even visited the female Benedictine monastery at Inkamana near Vryheid in KZN, and a male one at Egmont in the Netherlands. I knew that male Benedictine monks were addressed as "Dom". But I did not know that professed female Benedictines were addressed as "Dame". nor that they had "claustral" sisters. That I learnt from this book.

It's about a fictitious Benedictine monastery in England, and gives what seems to me a remarkably accurate picture of Christian monastic life. I knew some things about Benedictines. I knew a few people who had entered Benedictine monasteries, but found the monastic life wasn't for them. I have even visited the female Benedictine monastery at Inkamana near Vryheid in KZN, and a male one at Egmont in the Netherlands. I knew that male Benedictine monks were addressed as "Dom". But I did not know that professed female Benedictines were addressed as "Dame". nor that they had "claustral" sisters. That I learnt from this book.In spite of its informativeness, however, it is not simply an "info dump" (that bane of would-be fiction writers), but it is a human story, and the characters stand out as real human beings.

It also brings out clearly how the monastic life, though more intense, is not essentially different from the Christian life in general. One scene that brought this out particularly strongly was when a novice nun receives letters from a man who had been in love with her for a long time. He addressed her by her secular name, pleading with her to leave the monastery, abandon the monastic life and marry him. She would not reply to his letters, saying she would only do so if he addressed her by her monastic name, thus acknowledging her decision and her right to make it. She asked the Abbess if that was not right. "It's right," said the Abbess, "but is it kind?"

That reminded me of the saying, quite commonly uttered in the time that the story is set (the 1950s and 1960s), that it is better to do wrong for the sake of love than to insist on doing right because of my lack of it.

There is sometimes a perception that it is easier to be a Christian in a monastery, because one is protected from the temptations of the world, but this book does nothing to promote that view. Orthodox monastics I have known have often spoken of the monastic life as "my repentance", and that is more its distinguishing feature. In the monastic life it is no easier than anywhere else to become perfect. It is, however, easier to become aware of one's imperfections.

Western monasticism, or perhaps one should rather say "religious life", differs from Orthodox monasticism in having many different forms. There are monks, sisters, canons regular, mendicant friars and a whole lot of others.

By contrast, Orthodox monasteries all work more or less on the same lines. Most, however, seem to agree that Benedictines are monks, and they seem to be the closest to Orthodox monasticism. It is therefore rather strange to see Orthodox Christians advocating something called the Benedict option when it is very un-Benedictine. If you are Orthodox, please read this book to understand what the Benedict option really means. And it might also give some insight5 into Orthodox monasticism too, though I would be interested in hearing the views of Orthodox monastics who have read this book.

By contrast, Orthodox monasteries all work more or less on the same lines. Most, however, seem to agree that Benedictines are monks, and they seem to be the closest to Orthodox monasticism. It is therefore rather strange to see Orthodox Christians advocating something called the Benedict option when it is very un-Benedictine. If you are Orthodox, please read this book to understand what the Benedict option really means. And it might also give some insight5 into Orthodox monasticism too, though I would be interested in hearing the views of Orthodox monastics who have read this book. View all my reviews

January 18, 2021

Travelling in Tibet in the 1990s: colonialism and neocolonialism

Naked Spirits: A Journey Into Occupied Tibet by Adrian Abbotts

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I recently read Magic and Mystery in Tibet, written by a western visitor who illegally entered Tibet in the early 20th century. This book is about a couple of western visitors to Tibet 75 years later, when it was under Chinese occupation. And at the same time I was reading Orientalism, on how to deconstruct western views of "the Orient".

The earlier visitor, [author Alexandra David-Neel], had a couple of advantages. She could speak Tibetan, and she had also spent several years in Tibetan monasteries. And though she was an illegal immigrant, she was seeing a relatively independent Tibet, where Tibetans were free to be themselves. She was, nevertheless, also seeing Tibet through western eyes, and even, at one point, described herself as an Orientalist.

But the authors of Naked Spirits were tourists in the 1990s, when Tibet had been under Chinese rule for 40 years, and while foreign tourists could roam relatively freely in China proper, the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) was closed to all but expensive organised tour groups, who were kept isolated from the Tibetan people, and only allowed to see what their tour guides would allow them to see. Adrian Abbotts and his wife Maria therefore spent a great deal of time applying for permits to go to this or that place, and describe their dealings with Chinese officialdom and bureaucracy, and at that point it all seemed very familiar indeed. Tibet under Chinese rule reminded me of nothing so much as Namibia under South African rule, which I experienced from I went to Namibia in 1969 until I was deported from there in 1972.

The parallels between Chinese rule in Tibet and South African rule in Namibia were amazing, especially the attitudes and reactions of government officials to whom one applied for various permits and permissions to visit or travel through places. There were many parts of the book where I thought "Been there, done that." And Adrian Abbots and his wife evidently learned the lesson that we learned in Namibia: it is easier to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission.

Also similar was the naked racism. The white South African rulers thought themselves superior to the native Namibians just as the Han Chinese rulers saw themselves as superior to the native Tibetans, and tried to make their language dominant.

There are differences too. In Namibia the South African rulers at least pretended to a kind of respect for local cultures, and encouraged them to "develop on their own lines" (the lines, of course, being lad down by the South African government). In Tibet there was no such pretence. Within Tibet all higher education was in Chinese and for Chinese. Tibetans who wanted higher education had to travel to China proper, and be immersed for several years in Han culture before they could return home, a policy that seemed more akin to that of Sheldon Jackson in Alaska than to the South African Department of Bantu Education.

So the book was particularly interesting to read in the light of the recent growth of Chinese economic activity in Africa, which looks suspiciously like neocolonialism. This includes the destruction of Namibian forest by Chinese logging, and, just over the border in Botswana, the threat of fracking in the Okavango Delta by a Canadian mining firm. It doesn't matter if the neocolonialism is Western or Eastern, there is little difference.

View all my reviews

January 16, 2021

A Reading Diary: A Year of Favourite Books

A Reading Diary: A Year Of Favourite Books by Alberto Manguel

A Reading Diary: A Year Of Favourite Books by Alberto ManguelMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

I loved this book.

It looks deceptively simple. The author reads 12 favourite books, one each month, and keeps a diary of the thoughts he has while reading them. Some thoughts are relevant, inspired by the book, and others come from current events, near or far, foreign or domestic.

The cat has not come to be fed for three days now.

But how often, when reading, does a book not inspire thoughts, some worth recording, perhaps, and some not? This is a book of such thoughts.

The cat returned during the night.

In another place there are thoughts inspired by waiting for, and during the Second Iraqi-American War of 2003. Some thoughts seem trivial, like the ones about the cat, while others are profound, but even the ones about the cat spark of my own thoughts and memories of cats I have known.

Silvia, my old schoolmate, tells me that in my school is a plaque to the students murdered by the military. She says I'll recognize several names.

Of the twelve books Alberto Manguel read I had read only two: Kim and The Wind in the Willows; my review of Kim is here Kim revisited: imperialism, Russophobia & asceticism.

Today, at breakfast, my brother tells me that "only" ten percent of the judiciary system is corrupt. "Of course," he adds, "excluding the Supreme Court, where every single member is venal.

While typing that I am listening to Peter, Paul and Mary singing "...and if you take my hand my son, all will be well when the day is done" and I am transported 1500 km away and 50 years back to Windhoek, St George's Church Hall, where Cathy Roark (now Cathy Wood) is teaching that song to the confirmation class, and I wonder where they are today. Not many murdered by the military, perhaps, but some forced into the military to kill.

Half an hour later I pick up Kim where I left off reading yesterday and find these word spoken by the Lama: "Thou hast loosed an Act upon the world. and as a stone thrown into a pool so spread the consequences thou canst not tell how far.

View all my reviews

January 5, 2021

Orientalism

Orientalism by Edward W. Said

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I've been looking for this book for 20 years, and at last found a copy in a 2nd-hand bookshop. Since hundreds of people must have reviewed it in that period, I won't even attempt to write a review, which would simply be repeating what hundreds of other people have said. Rather I will comment on a few of the things that stuck me about it, and that I've learnt from it.

In his book Edward Said examines the Western academic discipline of Orientalism, or, as it is sometimes called, Oriental Studies. He notes that it is entirely a Western discipline. It is a study of the way the people of "the West" study the people of "the Orient", which is that part of the world that lies to the East of "the West". In other words, it is all subjective.

Said also looks at some of the terms the West uses to describe "the Orient" -- Near East, Middle East and Far East. Because they are subjective, these terms are rather vague, and can have different meanings at different times. Like so many subjective terms they tell you more about the people who use and devise them than it does about the people they purport to describe. If someone speaks of a place as "the Near East", that tells you little about the Near East, but tells you a bit more about the person wo whom the Near East is nearer than the Far East. To a person living in India, the "Near East" is actually the "Middle West".

Because of this particular viewpoint, therefore, the people of "the Orient" never get to talk about themselves. In "Oriental Studies" they are described and discussed as seen by outsiders. Actually, as Said points out, Orientalism was originally not much concerned with people at all; it was mainly concerned with literature and manuscripts.

Much of what Said says in this book rang a lot of bells for me, though they are not directly related to the content of the book, which is why I'm writing about them in a blog post instead of in a review on GoodReads.

My own academic field is Missiology, the study of Christian mission, and one of my particular interests in that field is African Independent Churches (AICs). African Independent Churches were studied and defined by academics who belonged to Christian denominations that had been founded by Western Christian missionaries, and therefore, like Said's Orientals, had been studied from the outside and defined from the outside -- see African Independent Churches: Judgement through Terminology.

I wrote that article before I had even heard of Edward Said's book, but what I said in it, it seems to me, is reinforced in many ways by what Said says in his book, even though he is writing about Muslims and I was writing about African Christians.

January 1, 2021

The Last Warrior: book & film review

The Last Warrior by Clair Huffaker

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Fifty years ago I saw a film called The Last Warrior, which I now discover has been renamed to Flap. I enjoyed the film very much, so when I saw the book in a second-hand bookshop last month I had no hesitation in buying it.

In the film a hard-drinking, reckless-living Indian named Flapping Eagle decides that his people have been pushed around by the white man long enough. Mounting his horse H-Bomb, Flap proceeds to hijack a railroad, lasso a helicopter, and begin the Last Great Indian Uprising. His assaults on the Establishment provide an earnest indictment of Indian neglect by the U.S. government. And that pretty much summarises the plot of the book as well. If my memory has not faded too much over the last fifty years, the film stuck pretty closely to the book

The story is both funny and sad, and well worth reading.

So much for the book review, but there is a deeper story behind why I had no hesitation in buying the book when I saw it.

When I saw the film I was living in Windhoek, Namibia, and working at a local newspaper, the Windhoek Advertiser for money, and otherwise for the local Anglican Church whose bishop, Colin Winter had an American secretary named Marge Schmidt. Marge had seen the film in the USA, and insisted that I must see it, so we went together to see it.

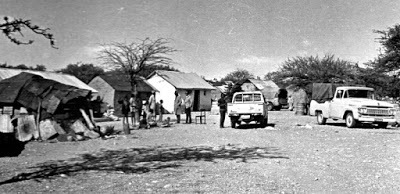

And I could see why she insisted I must see it. The film is mainly set in an Indian Reservation near Phoenix, Arizona (where Marge Schmidt now lives) And almost every weekend I visited poor rural communities like those shown in the film -- the Ovitoto Reserve for Hereros to the north, Rehoboth for Basters in the south, and in between there were small camps for road and railway workers, which closely resembled the places in the film.

Ovitoto Reserve, north of Windhoek, 1971

Ovitoto Reserve, north of Windhoek, 1971The time, 1971, was also a turning point for Namibia. The World Court had just declared South Africa's rule over Namibia illegitimate. The Lutheran Churches, who scarcely ever criticised the government, circulated an open letter declaring, in effect that South African rule of Namibia was misrule. And The Last Warrior was showing at a local cinema, which showed an analogous situation in the USA.

The effect on the cinema audience was profound.

In those days cinema audiences in central Windhoek were all white. And at the end of this film there was dead silence. People left in hushed silence. Usially people chatted with each other when leaving, about the film they had just seen or something else. They would greet people they knew. Some would laugh, some would call to others. But this time there was none of that. It seemed that no one missed the message of the film. It was not far away in the USA. It was here, and now.

I have never seen a cinema audience behave like that before or since. And that is why I think the film was worth seeing, and the book worth reading.

March 20, 2020

Khanya blog has moved

This blog has moved

In future I will be blogging at:

Notes from underground

This is because since February 2020 WordPress has become extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible to use. For details see here: Notes from underground: Reviving an old blog because WordPress is broken.

I originally started blogging at WordPress because the Blogger editor was broken. Now it has been fixed, and WordPress is broken. If the people at WordPress ever get around to fix I may return to blogging here.

Fortunately the existing posts can still be read, so I will still refer to them from time to time, and links to them from other sites should still work.

February 1, 2020

Back in the USSR

I’ve just finished reading two books on Russia, well, actually the old USSR, set 30 years apart — one in the 1960s, and the other in the 1990s when the USSR was falling apart.

[image error]One was Journey into Russia by Laurens van der Post, and the other was The Golden Horde by Sheila Paine.I read them together because I wanted to get a picture of how life in Russia had changed from when it was under Bolshevik rule, and immediately afterwards. I myself visited Russia in the 1990s, roughly at the same time as Sheila Paine, but didn’t travel more than 100 km from Moscow, and wanted to learn what other parts of the country were like, in part as background for a book I am writing, a sequel to my children’s novel Of wheels and witches, and partly because I enjoy reading travel books.

[image error]Journey into Russia and The Golden Horde are both travel books written by foreigners, from a British point of view. Laurens van der Post was originally South African, but had become thoroughly Anglicised by the time he wrote this book, though he uses his African background to compare Russian and Western culture as he experienced them.

Laurens van der Post wrote at the height of the Cold War, when media propaganda in the West tended to present the USSR in the worst possible light. “Even more than these cartoon inaccuracies what alarmed me on my travels were the factors of impersonalization and dehumanization in the pictures countries painted for themselves of other nations.”

So one of his purposes was to get behind the dehumanising Cold War rhetoric and to present Russians as human beings rather than as collective abstractions.

I could understand possibly that a nation might be tempted to bomb a country which it regarded as filled with dire monsters. But I firmly believed the temptation could be resisted the moment it saw the potential enemy as people like itself.

How well does van der Post succeed in this aim?

[image error]In his travels he tries to find out what what makes Russians tick, and he concludes that Russians have a collective mentality that differs from Western individualism. Bolshevism does not on its own account for this, and it goes back a lot further in Russian history, The institution of the collective farm, so common in Russia in the 1960s, can be traced back to the pre-Marxist tradition of the Mir.

That he approaches Russians from the point of view of Western individualism also shapes his perception of them, and I think this is over-simplified; back in the 1930s Stalin forced collectivisation on peasants who strongly resisted it, and one result was that millions died of starvation.

Van der Post concludes from this that Russians, like the African societies he grew up among in South are primitive, in contrast to the civilised societies of the West. “The Russians are naturally a communal people because they are basically a primitive people; and primitive man is naturally collective.”

But van der Post himself acknowledges that his view is over-simplified, when he says,

As a working oversimplification I would suggest that the primitive is a condition of life wherein the instinctive, subjective and collective values tend to predominate; the civilized condition of life is where the rational, objective and individual take command. Throughout history the two have been at one another’s throats because it appears that the value of one depends on the rejection of the other and this Jacob and Esau theme has been played out between the nations and cultures of the world with the reconciliation of the brothers not yet in sight.

Sixty years ago such terminology was common, but now it has generally changed. What van der Post calls “civilized” we now refer to as modern, and what he called “primitive” we are more likely to refer to as “premodern”. Postmodernity allows us to have a different perspective. But around the time that van der Post was preparing his book for publication I was reading, and strongly influenced by, two books that seemed to be making a similar point, The primal vision and The secular city. There’s more about them at Christianity, paganism and literature (synchroblog) | Notes from underground.

Where I think van der Post’s thesis breaks down is that Bolshevism was essentially a modern project. The Bolsheviks sought to modernise Russia, and complete what Peter the Great had started.

Sheila Paine, in The Golden Horde seems to be looking for the primitive of thousands of years earlier. Her book, however, is far more confusing than van der Post’s. Perhaps that’s because it’s more instinctive and subjective. One gathers that she is travelling the former USSR just after it broke up looking for triangular embroidered amulets with three pendants. She never explains why she is looking for them, perhaps because she wrote an earlier book on the topic and assumes that all her readers have read that one too.

[image error]As a travel book I thought it was pretty good, with some lyrical descriptions of places she visited, and giving a good impression of post-Soviet Russia and Central Asia. But while the descriptive bits of scenery are good, the narrative bits are poor and confusing. She gives a rather confused and garbled picture of Orthodox Christianity, which Sheila Paine seems to have made little effort to understand more than superficially. On two occasions she joins groups of Orthodox pilgrims on boat trips along rivers, and attends Holy Weeks services on a Greek island, but her accounts of those are very garbled indeed. And her description of her own search for amulets is the most garbled and confusing of all.She develops theories about the embroidery and amulets she is looking for, and then abandons them, but doesn’t explain why she abandoned them, perhaps because she had failed to explain why she adopted them in the first place, or even what they were. At one point she compares central Asian embroidery with Bulgarian embroidery, assuming that the reader is familiar with Bulgarian embroidery and therefore will know exactly what she is talking about.

Laurens van der Post also attended Orthodox services, in the far more restrictive period when Krushchev was in power, but even though, like Sheila Paine, he was an outsider, at a time when accurate information was much harder to come by, he seems to have had a better understanding of what he was seeing.

The Russians made their conversion to Christianity a sublimation of their finest primitive qualities. The emphasis was on the collective values of religion, on the unifying aspects, the capacity of “bringing together” of Christianity. The Russian word for church of “Sobor” which in the first place means “gathering”, and “Sobornost” (“togetherness”) is one of the most meaningful of all Russian words and the quintessence of what the church tried to promote. It served a vivid primitive instinctive sense of communion in men not only with one another but also mystical participation with all life.

Laurens van der Post has a point; Russia never went through the three key events of modernity — the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment. In that sense it was premodern, and van der Post saw Russians through the eyes of Western modernity. But sixty years later we can see things in a different, and perhaps postmodern perspective, seeing both van der Post and the contemporary Russians through postmodern spectacles. Doing that enables us to make a distinction between “communal” on the one hand, and “collectivwe” on the other. Communalism, “sobornost”, is essentially premodern, a communion of persons. “Collective” on the other hand, is modern, and implies an undifferentiated mass.

Van der Post recognised this to some extent when he wrote:

It was no good pretending that these people did not feel cheated. The revolution had worked a confidence trick on them all. They had revolted in order to have the land to themselves. But no sooner was the revolution consolidated than a far more inflexible landlord, the State, had taken it away from them again in the name of collectivization. And, judging by the show pieces I saw, there were few farmers in charge of farms. Party secretaries, accountants and factory foremen were the types one usually found in positions of command.

I suspect that in the old premodern communal farms of the Mir the ones in charge were farmers. In the new modern collective farms of the Bolsheviks those in charge were not farmers but bureaucrats. And that is why the peasants resisted Stalin’s forced collectivisation.

And perhaps we can see much the same development in the “State-owned Enterprises” (SOEs) in South Africa. The old Electricity Supply Commission (ESC, Escom) was run by electrical engineers; the new SOEs are run by bureaucrats. The essence of modernity is a world run by and for MBAs.