Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 15

May 30, 2021

The Madonna of Excel;sior

The Madonna Of Excelsior by Zakes Mda

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

A novel that has a little bit of everything, almost -- a sex scandal, sibling rivalry, political chicanery, and believable characters. And so much of it is true, I read it in the newspaper 50 years ago.

It is set in a real small town in the Free State province of South Africa, and is based on real events, so the usual disclaimer about the characters not resembling any real persons, living or dead, is somewhat differently worded. Though the events are a matter of public record, the characters are fictitious. I've written a few books set in a small South African town, but having lived in a small town myself, I didn't dare to use a real town as the setting, but Zakes Mda boldly does so, and his book is all the more realistic as a result.

But the fictitious characters do resemble real people. And the book gives a microcosm of South Africa in the last three decades of the 20th century. Excelsior is a real town, and it really was rocked by a sex scandal in the early 1970s. The neighbouring towns, mentioned in the book, are real and I have been to, or through some of them.

But the fictitious characters do resemble real people. And the book gives a microcosm of South Africa in the last three decades of the 20th century. Excelsior is a real town, and it really was rocked by a sex scandal in the early 1970s. The neighbouring towns, mentioned in the book, are real and I have been to, or through some of them. And at least one of the characters is real, Father Frans Claerhout, a Roman Catholic and artist who lived at Tweespruit just south of Excelsior, and descriptions of whose paintings at the beginning of each chapter form a linking motif for the story.

Popi Pule has two half-brothers; one, Viliki Pule, is black, and the other, Tjaart Cronje, is white, and all three were born in apartheid South Africa, much of whose legislation was calculated to prevent precisely those kinds of relationships. Viliki and Puke's mother Niki had been Tjaart's nanny when he was small, and she is the eponymous Madonna of Excelsior, and had been a model for some of Father Frans Claerhout's paintings.

People sometimes ask, what was South Africa like during apartheid, and during and after the end of apartheid, and in this book Zakes Mda nails it. He tells it like it is, and was. He has written several books set in South Africa, and each of the ones I've read gives an accurate picture of some or other aspect of South African life. There are links to some of my reviews of them here,

If but someone from another country was coming to South Africa from another country, and wanted an introduction to South African life, and history, and social relations, this is the book I would recommend to them. Since it is fiction, it doesn't have all the facts, but it does tell the truth about South Africa, the unvarnished truth. If you want to know what South Africa is really like, read this book!

View all my reviews

May 26, 2021

The Quiet American

The Quiet American by Graham Greene

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I think this is one of Graham Greene's best books. I find Graham Greene a bit like Stephen Kind -- I like some of his books a lot, and others I don't like much at all. This is definitely one that I liked.

Thomas Fowler is a reporter for a British newspaper, reporting on the French colonial war in Vietnam when the Americans are just beginning to get involved. One of the new people at the American embassy, Pyle, tries to befriend Fowler, and falls in love with his girlfriend, Phuong, whom he steals, ever so politely.

Fowler tries to be neutral in his reporting, and to remain uninvolved, but Pyle's role causes him to reexamine his approach, and but he is never sure whether his actions are due to Pyle's political role or his own jealousy.

Fowler tries to be neutral in his reporting, and to remain uninvolved, but Pyle's role causes him to reexamine his approach, and but he is never sure whether his actions are due to Pyle's political role or his own jealousy. Perhaps one reason that the book appealed to me so much is that it reminded me of my time in Namibia in the early 1970s. Namibia was then in a colonial situation, under South African rule, as Vietnam had been under France 15 years earlier, and I was, like the protagonist in The Quiet American, a journalist. And something Greene wrote illuminated a difference that I was aware of, but fund difficult to describe.

In December 1971 there was a big strike of Ovambo contract workers in what was then known as South West Africa. One of the interesting differences in the approach to journalism came on the second day of the strike, Tuesday 14th December 1971. My friend David de Beer and I worked for the local Anglican Church, and I also worked on the local paper, and we were also stringers ("correspondents") for the Argus Africa News service, which supplied most of the South African evening newspapers. But the strike was big news, so some of the newspapers sent their own in-house reporters to cover it, and one of them was Alan Hardy of The Star of Johannesburg.

Pastor Maasdorp of the Lutheran Church had said that one of their evangelists had been arrested in the Ovambo compound, and that Pastor Haufiku was busy trying to bail him out. Alan Hardy immediately phoned Brigadier Brandt, the local police chief, who denied that there had been any arrests. Dave and I went out to see Pastor Haufiku to check up, and he confirmed it, and said he would take us to see the evangelist, Thomas Nalupi. And Thomas Nalupi showed us his admission of guilt receipt.

This ties up with an interesting passage in The Quiet American, where the protagonist, the journalist Thomas Fowler says:

It had been an article of my creed. The human condition being what it was, let them fight, let them love, let them murder, I would not be involved. My fellow journalists called themselves correspondents; I preferred the title of reporter. I wrote what I saw. I took no action—even an opinion is a kind of action.

Alan Hardy was a reporter, Dave de Beer and I were correspondents. And that describes the difference between us. To confirm a report that there had been arrests, the reporter asked the chief of police. That would never have occurred to us correspondents. For us the convincing evidence was the admission of guilt receipt.

There was more, perhaps. Alan Hardy was a bit older than us, but not by much. But he belonged to a different generation. We belonged to the 1968 generation. It had been, for both Dave and me, our last year as full-time students, and that was the year of student power, which had been immediately preceded by the year of flower power. But both hippie flower power and student power shared a distrust of authority. I had even developed a theological rationale for it. One of the slogans was "Don't trust anyone over 30," and I had just passed my 30th birthday, though I thought the least trustworthy age was between 40 and 60, when people were at the most powerful stages of their careers and were most likely to be embedded in and thus wedded to the System.

There was more, perhaps. Alan Hardy was a bit older than us, but not by much. But he belonged to a different generation. We belonged to the 1968 generation. It had been, for both Dave and me, our last year as full-time students, and that was the year of student power, which had been immediately preceded by the year of flower power. But both hippie flower power and student power shared a distrust of authority. I had even developed a theological rationale for it. One of the slogans was "Don't trust anyone over 30," and I had just passed my 30th birthday, though I thought the least trustworthy age was between 40 and 60, when people were at the most powerful stages of their careers and were most likely to be embedded in and thus wedded to the System.Of course the trouble with us was that we seldom adhered to the "audi alteram partem" rule, but then neither did the establishment reporters. They put the point of view of the establishment, businessmen, employers, government officials, whereas we reported what we heard from the underside -- the strikers and ordinary workers and those who ministered to them. And Graham Greene in this book illustrated the difference very clearly.

And perhaps even more clearly he showed the shallowness and folly of much American foreign policy. Pyle, the eponymous "quiet American", was a fan or a particular (fictional) foreign policy wonk called York Harding. And at one point Dave de Beer met just such an American foreign policy wonk by the name of George Kennan, who struck Dave as incredibly naive. Kennan talked as though all he had to do was press some magic button in the depths of the Pentagon and all Namibia's problems would be instantly solved.

I have sometimes wondered since then whether George Kennan was playing some devious game, and trying to appear more naive than he actually was, but since reading Graham Greene's book I wonder if he wasn't the model for York Harding.

View all my reviews

May 25, 2021

Missiology and the colour of fish

One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish by Dr. Seuss

I haven't read this, but GoodReads recommended it to me, based on the books in my Missiology shelf. That intrigued me. I see most of my GoodReads friends who have rated it gave it a high rating, -- perhaps they can tell me what it has to say about missiology.

Here are some of the books on my missiology shelf, and I'm not sure how the Dr Seuss book fits in with these:

I used quite a number of them for writing my doctoral thesis in missiology, but I seem to have missed the Dr Seusss one. Was my missiology thesis any the worse for that?

Actually one of my favourite missiology books doesn't seem to have made the list, so I'll give it a plug here -- it's Orthodox Alaska by Father Michael Oleksa, and you can read more about it here: Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission by Michael Oleksa | Goodreads.

It too seems to have a rather strange list of "readers also liked" books -- only one of those in the top ten seemed to have anything to do with missiology, but some of them nevertheless seemed quite interesting.

So here;s a challenge to fellow missiologists on GoodReeds. Look at the books on your missiology shelf, and share what the top one is, and how many missiology books appear in your top ten. Perhaps it will show how widely-read missiologists are.

And perhaps it ought to show that, because missiology is an interdisciplinary field of study, covering theology, history, sociology, anthropology and several other things as well. But fish?

View all my reviews

May 14, 2021

Over sea, under stone

Over Sea, Under Stone by Susan Cooper

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This book has been on my "to read" list for about four years now, as has the whole The Dark is Rising series. because friends recommended it, or wrote good reviews of it.

My search became more urgent when a reviewer compared my children's books Of Wheels and Witches and The Enchanted Grove to the whole "The Dark is Rising" sequence, and suggested that it might have been an influence on my writing.

It couldn't have been an influence on me, because I hadn't read it yet, but there certainly are similar tropes in both my children's books -- children on a quest, getting separated and searching for each other, an older boy who is a bully, some getting captured by the villains and threatened by them. There is even a hair binding that comes undone causing one character to lose her pony tail. But my influence came more from Alan Garner and I wonder if Susan Cooper's did too. It seems that they did meet, and regarded each other as kindred spirits.

Anyway I found the book a very good read. I liked the characters, the children especially, since more than half the adult characters were evil. It is a story of three children, Simon, Jane and Barney Drew, who go with their parents and a great uncle (who is not really a relative, but rather a friend of the family) to spend a holiday in a house in Cornwall, whose owner has gone off for a holiday somewhere else. They find an abandoned document and map, which they use to play games of seeking treasure, and then find that it is really old, and some evil people are also looking for it.

Anyway I found the book a very good read. I liked the characters, the children especially, since more than half the adult characters were evil. It is a story of three children, Simon, Jane and Barney Drew, who go with their parents and a great uncle (who is not really a relative, but rather a friend of the family) to spend a holiday in a house in Cornwall, whose owner has gone off for a holiday somewhere else. They find an abandoned document and map, which they use to play games of seeking treasure, and then find that it is really old, and some evil people are also looking for it. In the Good Reads page for the book there was a question about why the book was written in such an old-fashioned way, and so I watched out for that while reading it. As some people remarked, it could be because it was written over 50 years ago, and speech was different then. In the book the children wore "plimsolls", but by the time the Harry Potter books appeared, 30 years later, "plimsolls" had become "trainers", so that would probably have appeared old-fashioned even 25 years ago, when the Harry Potter books first appeared. I was particularly aware of that when I went to England in the 1960s, because I thought of "plimsolls" as marks on ships, and we called such footwear "tackies" (sometimes spelt "takkies"), both then and now -- the term is applied to any shoes with canvas uppers and rubber soles.

Some language would have appeared old-fashioned even in the 1960s -- I don't recall any children at that time referring to their male parent as "Father" with a capital F. But what really struck me as an anachronism was that one of the characters found two 50 pence pieces in his pocket, in a book published in 1965. Even in 1968, when the edition I read was alleged to have been published, though two of the new decimal coins were beginning to circulate, a 50p piece was not among them, they were still 10-bob notes. So if 10-bob notes miraculously changed into 50p coins, why did plimsolls not change into trainers? Or Father into Dad?

The edition of Over sea, under stone that I read was illustrated by pen and ink drawings by Margery Gill. The illustrations were appropriate to the text, but though the faces were drawn very well, the legs were not, and looked like those of children in pictures used to illustrate children freed from concentration camps suffering from malnutrition. Such legs could not have carried anyone fast enough to do all the running away they had to do from the villains. This particular picture, however, was one of the ones with more realistic legs.

The edition of Over sea, under stone that I read was illustrated by pen and ink drawings by Margery Gill. The illustrations were appropriate to the text, but though the faces were drawn very well, the legs were not, and looked like those of children in pictures used to illustrate children freed from concentration camps suffering from malnutrition. Such legs could not have carried anyone fast enough to do all the running away they had to do from the villains. This particular picture, however, was one of the ones with more realistic legs. I recently re-read three of Alan Garner's children's books, and comparing his language to Susan Cooper's, I find his more terse and taut, which conveys a sense of urgency in the way it is written.

I was inspired to write my children's (and other fiction) by a conversation between C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, in which they said that if they wanted to see more of the kind of stories they liked, they should have to write them themselves. And I liked stories by Charles Williams and Alan Garner. But it seems that Susan Cooper has also written the kind of stories I like, and all but two of them are waiting for me to read therm.

Her writings are not entirely new to me, however.  Back in the 1960s I did read Mandrake by Susan Cooper, which was adult science fiction rather than children's fantasy. I was reading it on the train from London to Bournemouth at the very time Dr Verwoerd was shot, and it was in fact about an English version of the Verwoerdian dream, where a British prime minister decided that everyone had to go back to their "homeland", and enacted laws to force them to do so. I never saw another book by Susan Cooper in a bookshop after that, though I see she has written quite a lot, and I'm putting more on my "want to read" list.

Back in the 1960s I did read Mandrake by Susan Cooper, which was adult science fiction rather than children's fantasy. I was reading it on the train from London to Bournemouth at the very time Dr Verwoerd was shot, and it was in fact about an English version of the Verwoerdian dream, where a British prime minister decided that everyone had to go back to their "homeland", and enacted laws to force them to do so. I never saw another book by Susan Cooper in a bookshop after that, though I see she has written quite a lot, and I'm putting more on my "want to read" list.

I've spent some time commenting on the language in this review, but that's because I found little else to criticise, and because someone asked a question about it. And now I hope I'll be able to find the rest of the series and renew my acquaintance with the characters.

April 14, 2021

Book cover fashions: the headless torso

I've commented before on the current fashion, in some circles, for having headless male torsos to illustrate book covers -- see Urban fantasy, mediocrity, and the male torso | Notes from underground, but now that I'm thinking of revising and reissuing one of my children's books with a new cover, I'm wondering about the possibilities.

This seems to be a fairly common theme for a cover nowadays...

... though one wonders what the faceless characters are like in the book.

So I'm wondering if my revised children's adventure-fantasy story should follow a similar theme, something upon these lines.

So I'm wondering if my revised children's adventure-fantasy story should follow a similar theme, something upon these lines.How important is it that book covers should follow the latest fashions? Will it enhance sales if the book has a headless torso, and diminish sales if it lacks one? And who is attracted to books with headless torsos anyway? Does anybody know?

If I give that picture to a book-cover designer, would they be able to turn it into a suitable cover design? Does it matter that the kid in the picture is blowing bubbles? The protagonist in my story doesn't blow bubbles, but he doesn't lack a head either, in the story.

Are there any other important tropes in book covers that one needs to take into account? If so, what are they?

April 11, 2021

[Writing a Thriller by Andre JuteMy rating: 4 of 5 starsO...

Writing a Thriller by Andre Jute

Writing a Thriller by Andre JuteMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

One of the things that I am still a bit confused about is literary genres, and people seem to have so many different names for them that it gets very confusing. Some are used by publishers to say what kinds of books they do or don't publish, and those are reasonably clear -- crime, romance, children's etc. So when I found a couple of books on writing thrillers in the local library,I read them to try to answer the question "What is a thriller?"

The first one I read, Writing the Thriller (my review here), was also because I was doing a final edit on my children's book, The Enchanted Grove. My book is an adventure story, rather than a thriller, but where does one draw the line? And even adventure stories have thrilling scenes in them, where the characters are in danger, don't they?

The first one I read, Writing the Thriller (my review here), was also because I was doing a final edit on my children's book, The Enchanted Grove. My book is an adventure story, rather than a thriller, but where does one draw the line? And even adventure stories have thrilling scenes in them, where the characters are in danger, don't they?Writing a Thriller by Andre Jute at least answered that question for me. The adventure story has the characters in danger from external enemies. In the thriller the situation is complicated by betrayal from within. The thriller is therefore more complex.

The only problem with that definition is that many books advertised as thrillers might not actually be thrillers.

I found this book more useful for clarifying that and similar questions that I had. But it is also an older book, and may not be so useful to would-be thriller writers in the information it gives on the publishing process and manuscript submission. Clearly, it was written when word processors were in their infancy, and assumed that most people would be typing their story directly onto paper, and editing the paper typescript, and cutting and pasting literally with scissors and paste, and not in the sense of the Microsoft Windows metaphor.

The book also cites some of the thrillers that the author himself has written as examples, Reverse Negative and Sinkhole, but I notice that neither has a single review or rating on GoodReads. And, on a personal note, the author seems to have a strong prejudice against missionaries, and as a missiologist, I have a particular interest in missionaries, but that is just a personal prejudice and shouldn't affect one's evaluation of the book.

If you're thinking of writing a thriller, it could be a useful book to read, bearing in mind that it deals with dated technology. But the actual writing advice is generally useful.

View all my reviews

April 7, 2021

Earworms and dreams

Odd how thoughts develop. I find myself humming the tune of What a friend we have in Jesus, and the name Joseph Medlicott Scriven pops into my head. He wrote either the words or music, I forget which, and I know that because it was printed in the Methodist Hymn Book that we had at St Stithians College. And I recall that the first line of the preface said "Methodism was born in song". So that is the main thing I know about Methodism. I did learn some things in my six years at St Stithians, and those are some of them.

Then last night I had an interesting dream, well interesting to me at least, it's probably boring to most people.

I was at a conference (why do I always dream about conferences?) where we were all issued with fat books containing a report on South African Foreign Policy, and I rejected it because it immediately made me think of Pik Botha, then wondered why I thought that, because Pik Botha has been dead for years and has had no

influence on foreign policy for a long time.

Anyway, that's what I wrote in my diary today. We write mostly boring stuff like that in diaries because under Covid lockdowns we don't go out much and nothing much happens. We hear what our friends are doing on Facebook and other social media, and we post pictures of sunrises and sunsets, Here's my picture of the sunrise this morning. I posted it on Facebook too. My cousin Jenny in Durban did get out today, however. She went to the dentist. She posted a picture of a tollbooth in the rain which she passed on the way.

Anyway, that's what I wrote in my diary today. We write mostly boring stuff like that in diaries because under Covid lockdowns we don't go out much and nothing much happens. We hear what our friends are doing on Facebook and other social media, and we post pictures of sunrises and sunsets, Here's my picture of the sunrise this morning. I posted it on Facebook too. My cousin Jenny in Durban did get out today, however. She went to the dentist. She posted a picture of a tollbooth in the rain which she passed on the way.Speaking of Pik Botha, one of the best political jokes I've ever heard was about him.

It was when Benny Alexander changed his name to KhoiSan-X, And someone remarked that if Benny Alexander was KhoiSan-X, then Pik Botha must be Guronsan-C.

But then I haven't seen Guronsan-C advertised for a long time. It was advertised as something that could revitalise decrepit old fogeys like me.

But the best thing that happened to me today is that Dan'l Danehy-Oakes read one of my books and wrote a review of it. If you're a member of GoodReads and feeling benevolent, go and read and "like" his review. If you're feeling especially benevolent, you could comment on it.

And then I saw this on Twitter:

Phil Gentry@pmgentry·Apr 5A professor of mine went to go hear Derrida speak once. The entire talk was about cows; everyone was flummoxed but listened carefully, and took notes about...cows. There was a short break, and when Derrida came back, he was like, “I’m told it is pronounced ‘chaos.’”

I once went to hear Derrida speak. Should I put that on my CV?

Have a nice uneventful day!

March 30, 2021

Reading old books

A similar question was asked a few years ago about how many books people have read that were published before they were born. It's similar not in that it has to do with knowledge of a specific historical event, but rather enables one to realise that the past is another country, a different world, with a different culture.

Since then I have tried to keep a record of the books I have read that were published before I was born, and here's my list over the last five years. How many of them have you read, and which others have you read that were published before you were born?

I've also been reading books about writing, and find it interesting to see the contradictory advice given to writers on what they should be reading to imporve their writing. One said that one should only read books published in the last couple of years, because that way you will know what kind of books are currently popular and will sell well.

Others, as I said, point out that your own writing will have greater depth and greater human sympathy if you read books published before you were born.

Want to give it a try?

Read this:

March 17, 2021

Jess by H. Rider Haggard: love story or political rant?

Jess by H. Rider Haggard

Jess by H. Rider HaggardMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

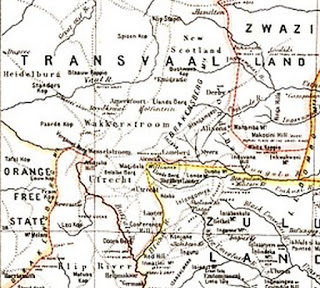

H. Rider Haggard is probably best known for his fantasy-adventure stories of imaginary peoples in unknown lands. This one is romance-adventure in a known land -- known to Rider Haggard anyway -- the Transvaal before, during and after the First Anglo-Boer War.

Rider Haggard was there, for at least part of the time. He was the one who raised the British flag when a litlle group of part-time soldiers ands civil servants from Natal marched to Pretoria and annexed the South African Republic as the Transvaal, with hardly a mutter of protest from the eastwhile republican citizens.

A few years later, however, some of the republicans, dissatisfied with British rule, rebelled, and the result was the First Anglo-Boer War. The war lasted less than six months, from December 1880 to March 1881, and resulted in the retrocession of the Transvaal, which, this book makes clear, was a huge disappointment to Haggard.

In the story, John Niel goes to work on a farm near Wakkerstroom, owned by an old Englishman, Silas Croft, whose two orphaned nieces live with him. John Niel falls in love with both nieces, first one and then the other, and they both fall in love with him, and the main theme of the book is the conflicting romantic interests. The outbreak of war complicates things, and disrupts their relationships, and enables the chief villain of the story, Frank Muller, who has a crush on Bessie, to manipulate things in his favour..

This book, far more than his fantasy stories, is permeated with Haggard's racism and imperialism, and can be seen at one level as a piece of of political propaganda disguised as a love story.

The political background is this: Lord Carnarvon, who was Conservative Secretary of State for the Colonies 1874-1878, impressed by the Confederation of Canada in 1867, wanted to achieve a similar confederation in South Africa, which was then a patchwork of British colonies, Boer republics, and independent African principalities and kingdoms, the most powerful of which was Zululand under King Cetshwayo. Political tensions between these often led to British military intervention at great expense to the British taxpayer, and uniting them under one political authority on the Canadian model would, Carnarvon thought, reduce causes of conflict, and enable them to pay for their own military.

The first step to achieving this was to take over the Boer South African Republic (ZAR), which became the Transvaal Colony, where, as previously stated, H.Rider Haggard had raised the British flag. There had been a border dispute between the ZAR and Zululand, which the Natal colony adjudicated and found in favour of Zululand (the Keate Award), but having taken over the Transvaal they became a party to the dispute and reneged on the agreement. Britain therefore provoked a war with Zululand (the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879) in pursuit of the Confederation ideal, and having neutralised Zulu power also reduced the desire of Transvalers for British rule and protection, hence the rebellion of the Transvaal Boers, which became the first Anglo-Boer War, or the First War of Independence for the Transvaal Boers. During the two wars, in 1879 and 1881, the British military suffered its biggest defeats of the 19th century -- first at Isandlwana in the Anglo-Zulu War, and two years later at Majuba (near Wakkerstroom) in the Anglo-Boer War.

The first step to achieving this was to take over the Boer South African Republic (ZAR), which became the Transvaal Colony, where, as previously stated, H.Rider Haggard had raised the British flag. There had been a border dispute between the ZAR and Zululand, which the Natal colony adjudicated and found in favour of Zululand (the Keate Award), but having taken over the Transvaal they became a party to the dispute and reneged on the agreement. Britain therefore provoked a war with Zululand (the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879) in pursuit of the Confederation ideal, and having neutralised Zulu power also reduced the desire of Transvalers for British rule and protection, hence the rebellion of the Transvaal Boers, which became the first Anglo-Boer War, or the First War of Independence for the Transvaal Boers. During the two wars, in 1879 and 1881, the British military suffered its biggest defeats of the 19th century -- first at Isandlwana in the Anglo-Zulu War, and two years later at Majuba (near Wakkerstroom) in the Anglo-Boer War. At the same time the Conservative government in Britain was replaced by a Liberal one, with William Gladstone as Prime Minister. The Liberals were far less imperialist than the Conservatives, and thought that Lord Carnarvon's Confederation plan was totally impractical and far too expensive, and so handed back the Transvaal to the victorious Boers, much to Rider Haggard's chagrin, expressed throughout Jess.

But the Liberal interlude was merely the calm before the storm. By the mid-1880s the New Imperialism and the Scramble for Africa had got under way, with Haggard's approval, expressed in a footnote in my edition of the book.

.

These words were written ten years ago, but since then, with all gratitude, be it said, a change has come over the spirit of the nation, or rather the spirit of the nation has re-asserted itself. Though the 'little England' party [ie the less-imperialist Liberals] still lingers, it exists upon the edge of its own grave. The dominance and responsibilities of our Empire are no longer a question of party politics and among the Radicals of today [ie the 1890s] we find some of the most ardent imperialists [eg the Conservative Secretary of State for Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, who was a Radical 'gas and water socialist;']. So may it ever be! H.R.H. 1896.

In Jess therefore, Haggard portrays the Boers in the worst possible light, since they are the enemies of the British empire. Most of the Boers in the book are caricatures, including the villain, Frank Muller. The Zulus fare slightly better, having been defeated by the British two years earlier (than the time of the story), but are still, in Haggard's eyes, very much an inferior race compared with the British, as are the Hottentots.

The villain, Frank Muller, seems a bit over the top. He oscillates wildly between uttering flattering endearments and violent threats to Bessie, whom he claims to love. No one in his right mind would imagine that such threats could persuade someone to love them; they are utterly incompatible with any kind of love. But perhaps Frank Muller is a rather extreme example of a psychopath and is portrayed rather well. If a psychopath is someone who has no conception of love at all, but is a person whose every utterance is calculated to manipulate other people, then perhaps Rider Haggard has portrayed Frank Muller very well as such a character.

I enjoyed the book at two levels: first, as a love story, it was well-written and had plenty of drama. Secondly, for its historical interest, it shows the British imperialist reaction to events of the late 1870s and early 1880s. Though his main characters may be fictional, the contemporary political figures Haggard mentions: Carnarvon, Gladstone, Shepstone, Lanyon, Kruger and others, are real, and we can learn something of Haggard's reaction to them as an ardent imperialist. Haggard clearly expected his readers to know who these people were and what they had done, because in this book he tells us in no uncertain terms what he thought of what they had done. On the other hand, Haggard's philosophical asides tend to become rambling and rather tedious, but perhaps that reflects the current taste for the "show don't tell" fashion of fiction writing.

View all my reviews

March 3, 2021

The Enchanted Grove

My new children's book, The Enchanted Grove, is now available in paperback from Lulu Bookshop. It is suitable for kids aged 9-12 (and also for those kids over 25 who enjoy reading children's stories like the Narnia books).

It is also available as an ebook in various formats from most ebook retailers, like Apple, Barnes & Noble, Kobo etc. and from Smashwords. A Kindle version is also available from Amazon.

Jeffery, Janet and Catherine spend their summer school holidays swimming and riding horses in the foothills of the Drakensberg mountains of South Africa. But then they have to deal with bullying teenagers who are into witchcraft, poachers, and the strange guardian of a cave of Bushman paintings. And just when it seems that things couldn’t possibly get worse, the children stumble across a secret government project that the police think they know far too much about.

The story is set in December 1964, in the southern Drakensberg, in the fictional village of Pineville (so no one will be tempted to try to identify any of the characters, other than contemporary political leaders, with actual historical characters).

The Enchanted Grove is a sequel to Of Wheels and Witches, which is about an earlier adventure of Jeffery, Janet and Catherine and their friend Sipho. But each story stands on its own, and they do not need to be read in any particular order.

ISBN

978-1-920707-63-7 Lulu (paperback)

978-1-920707-64-4 Kindle e-book

978-1-920707-65-1 Smashwords ebook

Of Wheels and Witches is at present only available as an e-book, but if The Enchanted Grove sells well, I might bring out a paperback edition of Of Wheels and Witches as well.

If you have read The Enchanted Grove I would be grateful if you write a review, on your blog, or in any journal or magazine you contribute to, or on the Smashwords page or the GoodReads page for the book.