Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 12

February 5, 2022

The Spire by William GoldingMy rating: 3 of 5 starsNot su...

The Spire by William Golding

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Not sure what to say about this book, except that it reminded me a bit of Malone Dies, which I re-read last year.

I kept thinking I was missing something, and went back to read certain bits, and then back to the beginning to see if I could pin it down, but I haven't been able to so far.

One of my first impressions, when I started reading it, was that it was a kind of parable for the Covid pandemic. The builders kept warning the dead, ?Jocelin, that it was not possible to build such a spire on such shaky foundations, but he urged them to go ahead anyway. And I thought of Donald Trump in the USA, telling people that it wasn't serious, and that anyway a vaccine would soon be developed that would solve the problem, and when the vaccine was developed, many of his supporters refused to take it. It seemed to be that kind of folly.

Experts on writing fiction (often self-proclaimed experts) warn against including too much of the backstory in a novel -- get on with the action. But reading The Spire I keep wishing for more of the backstory. Jocelin thinks about his angel, his demon, a witch and other things, as if the author expects readers to be familiar with the background, background that I seem to have missed on my first reading, and am still missing in the second.

Eventually there is some kind of commission of inquiry, and they tell him that he can go back to the deanery, where he goes, apparently to die. Other than that, we are not told their findings. Is he still dean, or has he been replaced? But he goes to his room, like in Malone Dies, but keeps getting up and wandering around, and eventually gets taken back to bed to die. Like Malone.

What have I missed?

January 29, 2022

Wildlord -- another novel in the tradition of Alan Garner

Wildlord by Philip Womack

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is the second novel I've read this month that seems to have been written in the tradition of the early Alan Garner, which is what I was hoping it would be after reading about it on Twitter. The first was Wildwood by Helen Scott Taylor, with the review immediately preceding this one

In this story Tom Swinton, an orphan, is invited by his uncle to spend his holidays on his farm in Suffolk, and he is keen to go, because the alternative is to spend the holidays alone at the empty school, even though he has never met the uncle. When he arrives, he is met by a strange taciturn boy who seems to be his own age, and a somewhat more talkative but equally strange girl. His uncle, and the house are more strange still, and seems almost paranoid about setting up magical barriers to keep some fairy-like creatures at bay.

The more he learns about the place and his uncle, the less Tom likes it, and Tom wonders whether it might not be better to spend his holiday at school, but then there are obstacles to his leaving. His uncle seems to have invited Tom there for a sinister purpose, though it is difficult to find out what that purpose is, but Tom also discovers that he had magical powers of his own, which seem to run in the family. The only think that seems normal abut the place is the dog, which helps to keep Tom sane, and he also receives some support from a human girl who had joined the fairy-like Samdhya people.

I had to order this book specially, because the local bookshop did not stock it, but I learnt of it through a favourable mention on Twitter. Those who enjoyed the Harry Potter stories and early Alan Garner stories might also enjoy itmight also like it. It's a good and exciting read, though I thought some of the scenes at the climax were a bit over the top, and debated whether to give it four or five stars, but in then end thought it deserved five.

I might have made more comments on the story, the plot and the characters, but I see that there have been very few other reviews, and so I'll save that kind of discussion for when more people have read it.

View all my reviews

January 6, 2022

Wildwood, a novel in the tradition of Alan Garner

Wildwood by Helen Scott Taylor

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

More than fifty years ago I read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner, and went on to read his other children's books, and wished he'd written more, or that someone else would, and now someone else has. This book is certainly in the same genre, though see below for a discussion of what exactly that genre is. The protagonist, Todd Hunter, is a teenager, but the story had more in common with Alan Garner's children's novels than his teenage ones like The Owl Service and Red Shift.

Todd Hunter's father has been missing for five years, and he doesn't get on well with his mother's new boyfriend, so when the rest of the family go to spend their holidays with the mother's boyfriend's family in France, Todd goes to stay with his paternal grandfather in a small Cornish fishing village. There he hopes to learn more about his father, and even perhaps to learn something about the mystery of his disappearance.

Todd's grandfather John runs a grocery shop, in which Todd helps out occasionally. There are few young people of his own age in the village. He meets a rather unpleasant boy of about his age, Andrew Bishop, who, like Todd, doesn't get on with his stepfather. But soon after Todd's arrival, Andrew disappears, and Todd discovers his body at the foot of a cliff. The police rule his death accidental, but Todd suspects that he was murdered by his stepfather, perhaps reflecting his dislike of his own stepfather, and decides to investigate Andrew's death on his own. He also meets a teenage girl, Marigold, whom he finds quite attractive, but is rather wary of, because he discovers that her mother is reputed to be a witch.

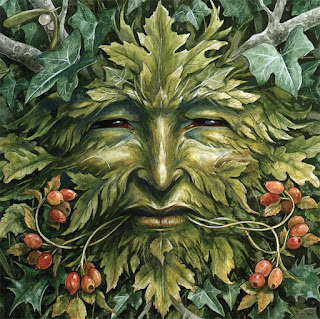

Before he has been in the village a week, Todd find himself investigating several mysteries -- his father's disappearance, Andrew's death, and a cult of the Green Man, which several people seem to be involved in. He also befriends an artist, Shaun, and his pet dog Picasso. Shaun, like Todd, is not originally from the village, and sometimes Todd finds his outsider's point of view refreshing. The longer he spends there, the more he feels he wants to get out, and the more he learns about the place and its history, and the activities of its present inhabitants, who seem determined to keep him there forever, the more he wants to leave.

Before he has been in the village a week, Todd find himself investigating several mysteries -- his father's disappearance, Andrew's death, and a cult of the Green Man, which several people seem to be involved in. He also befriends an artist, Shaun, and his pet dog Picasso. Shaun, like Todd, is not originally from the village, and sometimes Todd finds his outsider's point of view refreshing. The longer he spends there, the more he feels he wants to get out, and the more he learns about the place and its history, and the activities of its present inhabitants, who seem determined to keep him there forever, the more he wants to leave. I found it an exciting book, full of unexpected plot twists, though towards the end some of them became too inconsistent and inexplicable, with some characters shifting a bit too rapidly back and forth between loyalty and betrayal to be convincing.

The book seems to be only available on Smashwords, and if you like juvenile books with adventure, mystery, ghosts and a touch of supernatural magic, it's definitely worth a read. You can see a fuller description on the Smashwords site here.

As I said at the beginning, I thought this book would appeal to people who liked Alan Garner's children's books. I would say that this one is roughly in the same genre. But what genre is that, and how does one describe it? On Smashwords, Wildwood is described as "Y/A Paranormal" and I don't think I've ever seen Alan Garner's books described as "paranormal" before. I have written a couple of children's books in the same genre, and described them as "children's adventure/fantasy", though one of my reviewers did classify one of them as "paranormal-fantasy". In adult books with similar themes, the novels of Charles Williams have been described as "supernatural thrillers", but never, as far as I am aware, as "paranormal".

The problem here seems to be that for many people "fantasy" implies that the story is set in a location out of this world, and these stories are not (with the partial exception of Alan Garner's Elidor). The problem with "paranormal", for me at least, is that it evokes images of movies like Ghostbusters, and rather misguided attempts to measure spiritual phenomena with material instruments, like using a photographic light meter to measure the light from the transfiguration of Jesus, or parlour tricks like Uri Geller bending teaspoons.

Anyway, whatever you want to call this genre, I like it, and am glad to see other people writing it, and hope to write some more in it myself. Another book in the same genre is The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper, which I had read a few months before reading this one. As I explained in my review of The Dark is Rising, one of the things I didn't like much about that book was that the protagonist was not really human, but had superpowers, and there is a hint of that in Wildwood, where we are frequently told that Todd Hunter has a "hunter's instinct" that makes him different from everyone else. It's one of the reasons I gave the book four stars rather than five, not because it makes it a bad book or anything, but the star rating is subjective, how much a particular reader likes a book, and I don't much like books where the protagonist has superpowers, even when, as in the case of Todd Hunter, they so often fail at a critical moment.

December 31, 2021

The Plumed Serpent

The Plumed Serpent by D.H. Lawrence

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

Meh.

A long rambling waffling book about two men who found a neopagan religion in Mexico and an Irishwoman who marries one of them, and spends half the book trying to decide whether to marry him, and the other half wondering whether she ought to have done so.

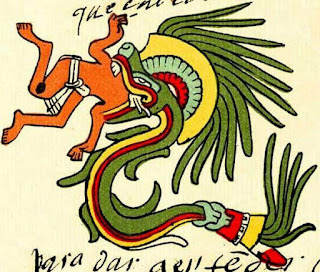

Kate Leslie, a wealthy middle-aged Irish tourist on holiday in Mexico, meets a Mexican general, and his friend, a wealthy landowner, and goes to visit their part of the country, where she extends her stay indefinitely. She helps to rescue the landowner from some would-be assassins, and is asked to marry the general and join the pantheon of their neopagan religion, in which the landowner is Quetzalcoatl, the eponymous plumed serpent deity, while the general is Huitzilopochtli. Kate is ambivalent about her assigned role as divine consort to Huitzilopochtli, and remains so to the end.

There are some good descriptive passages in the book, but they are spoilt by going on for too long, being repetitive, and eventually becoming boring. Lawrence seems to get carried away by his own verbosity, and doesn't know when to stop. And the descriptions of the neopagan religion also become very preachy, overdone and boring (see what I did there? That's one of Lawrence's little tricks -- as I repeated "boring", so Lawrence repeats key words in his descriptions).

There are some good descriptive passages in the book, but they are spoilt by going on for too long, being repetitive, and eventually becoming boring. Lawrence seems to get carried away by his own verbosity, and doesn't know when to stop. And the descriptions of the neopagan religion also become very preachy, overdone and boring (see what I did there? That's one of Lawrence's little tricks -- as I repeated "boring", so Lawrence repeats key words in his descriptions).So why, if it was so long-winded, preachy and dull, did I bother to buy and read this book?

The answer goes back to my youth in the early to mid-1960s, when I was a student at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg. The university English department had made its own literary neopagan religion, in which D.H. Lawrence was the chief deity, with a supporting cast of Joseph Conrad, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and Shakespeare, and their very own incarnate Huitzilopochtli, H.W.D. Manson, the greatest playwright since Shakespeare. I didn't earn any brownie points with my tuto, Christina van Heyningen, when I said that I liked Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter and Eugene Ionesco better than Manson's The Counsellors.

But I still thought I ought to read at least one D.H. Lawrence novel to see what all the fuss had been about, and I picked this one because it was exotic, at least to Lawrence, and wasn't full of coal mines, the English Midlands, and the early 20th-century working class.

As Kate is indecisive throughout the book, Lawrence (or at least his characters) can't make up their minds and they often expound inconsistent ideas, as does Lawrence when giving his omniscient narrator's opinion. The white and the dark-skinned races should never meet, and should have their own religions, their own cultures, their own way of life -- "own affairs" as the old apartheid ideology used to put it. But this will eventually lead to a new man, with new blood and all will be one. Oh yes, there's lot about blood in this story. It's a very bloody book, starting from the opening bullfight scene and drifting off into the obscure philosophy about how white blood and black blood should never mix, but will eventually become one, or something.

White blood is superior to dark blood, but the time of supremacy of dark blood is coming. And aristocratic blood is better than the blood of peons. Lawrence appears to believe in a kind of Nazi uebermensch:

The star which is a man's innermost clue, which rules the power of the blood on the one hand and the power of the spirit on the other. For this, the only thing which is supreme above all power in a man, and at the same time, is power; which far transcends knowledge, the strange star between the sky and the waters of the first cosmos; this is man's divinity. And some men are not divine at all. They have only faculties. They are slaves, or they should be slaves.Read it quickly, and it can sound profound. Read it paying more attention, and its profundities are as empty as those of the Unman in C.S. Lewis's Perelandra, and the only bit that actually says anything, other than meaningless symbols and abstractions, is the last sentence: Lawrence believes that some men are born slaves and others are born masters, and that's as it should be. It was probably passages like this that led some critics to say that Lawrence was being fascist here. But half the book is like this -- boring pretentious pseudo-spiritual twaddle.

December 30, 2021

The day Desmond Tutu rode on my bus

When Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu died at Christmastide 2021, lots of people were sharing their memories of him on social media, and I hope those memories are preserved, at least for the use of a biographer, for someone like Desmond Tutu surely needs a biography. The life and times of Desmond Tutu are the most critical in South African history. He saw the whole period of apartheid, and more than 25 years of what followed, and much in his life illustrates and epitomises that period.

I had already written most of my memories of him when he retired, and I've mentioned him quite a lot in my blogs, but there is one incident that perhaps deserves to be told in a little more detail, as illustrating his life and the times he lived in. It was Tuesday 5 December 1961, the day Desmond Tutu rode on my bus.

In 1961 I began working as a bus conductor for the Johannesburg Transport Department,. It was the year when South Africa switched to decimal currency in February, became a republic at the end of May, and held a general election in October, the fourth since the coming of apartheid, in which the National Party increased its majority. For the National Party it was a triumphant year. Not only had they achieved their Republic, but they had had the first general election since Union in which black voters had no say at all, because the "Natives Representatives" had been abolished the previous year.

In 1961 the Johannesburg Transport Department had three-way apartheid. There were buses for "Europeans Only", buses for "Non-Europeans Only" and buses for "Asiatics/Coloureds Only".

And on 5 December 1961 Desmond Tutu got on the Parktown North bus on which I was conductor. The bus was a two-man operated BUT 6-wheeler trolley bus, with a staircase at the back leading to the top deck, and long sideways seats over the back wheels, where Desmond Tutu was sitting. When I had finished collecting the fares, I stood on the back platform, because there were few new passengers whose fares needed to be collected, and my job was simply to give the right-of-way signal to the driver (two rings of a bell), when all the passengers had safely disembarked. So when I wasn't doing that, I chatted to Desmond Tutu.

And on 5 December 1961 Desmond Tutu got on the Parktown North bus on which I was conductor. The bus was a two-man operated BUT 6-wheeler trolley bus, with a staircase at the back leading to the top deck, and long sideways seats over the back wheels, where Desmond Tutu was sitting. When I had finished collecting the fares, I stood on the back platform, because there were few new passengers whose fares needed to be collected, and my job was simply to give the right-of-way signal to the driver (two rings of a bell), when all the passengers had safely disembarked. So when I wasn't doing that, I chatted to Desmond Tutu. I had known him for a little over two years then, mainly from Shoe Parties at St Benedict's House in Rosettenville. In 1959 Desmond Tutu had been a student at St Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville, and as it was just over the road from St Benedict's House, many of the students came to the monthly Shoe Parties, as did people from Anglican parishes all over Johannesburg. We had also both been members of the Postulants Guild, for those in the Anglican Diocese of Johannesburg who thought they might be called to serve in the ordained ministry of the Anglican Church.

He was then a deacon, and was on his way to see the bishop, Leslie Stradling, to discuss his ordination as a priest, which took place 12 days later, on 17 December.

The bus trip to the stop for the bishop's house, near the Johannesburg Zoo, only took about 20 minutes, of which we only chatted for about 10 minutes, when I'd finished collecting fares. Our chat was mainly about church things -- his impending ordination as a priest, what Leslie Stradling was like as a bishop (he was relatively new at the time, having been enthroned as bishop only two months before). Neither of us envisaged that within 25 years Desmond himself would be Bishop of Johannesburg.

What was significant about our conversation was not what we said, but that it took place at all, especially in the year of the triumph of the Spirit of Apartheid.

When Desmond got off the bus and we waved goodbye and I said I would see him at his ordination, and as soon as the bus pulled away from the stop, the other passengers began asking me "Who is that man? How do you know him? Why were you talking to him? Where does he come from? Where do you come from?"

If I had had foresight I could have said "That man is the future Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town," but of course I didn't and I just said that he was a deacon going to see the bishop about his future ministry as a priest.

But where did he come from? Where did I came from?

I said we both lived in Johannesburg, but he was originally from the Northern Cape, and I was originally from Durban.

The passengers didn't believe me. We must have come from overseas somewhere.

"Where are you from? France? Germany? America? Is that man an American Negro?"

It was simply inconceivable to the man on the Parktown North omnibus that a black South African and a white South African could have a normal human conversation in Johannesburg in 1961, the year of the triumph of apartheid. In 1961 South Africa was indeed a very strange society, in which normal behaviour seemed abnormal, even to normal people. But that was the society in which Desmond Tutu lived half his life, a society in which we used to sing at the time:

When I'm walking down the streetI

I must be careful not to greet

people of a different pigmentation

lest the government suspect

or the Special Branch detect

a dark affiliation -- to a communist organisation

December 17, 2021

On publishing half-baked ideas

One of the purposes of this blog, stated in the header ever since it started, is the publication of half-baked ideas. Perhaps something more needs to be said about that. The thought comes from an article that I read more than 50 years ago in a publication called Theoria to Theory, which advocated the publication of half-baked ideas.

It noted that "There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in any of the philosophies currently in use. Nil illegitime carborundum, which is hot dog

Latin for 'Don't let the bastards grind you down'".

In the article Irving John Good lists the kinds of people who might be against the publication of speculations:

People who are more concerned with development than research. This is a perfectly legitimate professional bias if it is not applied all the time; Perfectionists. A perfectionist is a person who does not like to be slapdash on ANY occasion. This is the sort of person who says that if a thing is worth doing at all it is worth doing well; People who think it is fatal to make a mistake, especially in print. Many senior civil servants;People without a sense of humour; People who have been unlucky enough to suffer personally through too much credit being given to someone else's half-baked idea, which they themselves had baked.And those likely to be in favour...

People who recognise the importance of vague thinking, including those who are incapable of exact thinking; Zen Buddhists; People who have more ideas than they have time to exploit, possibly because they are getting old, or cluttered up with administrative responsibilities;Cranks and geniuses (is a genius a crank who turns out to be right?); People who think that if a thing is worth doing at all, it is worth half doing;People who see that their reading would give a better return for a given expenditure of time if the literature emphasised ideas more than technical details.But it seems to me that we had to wait another 30 years from the publication of the article for the ideal medium for the publication of half-baked ideas to appear -- the blog.

So there is generally a difference between a blog post and a scholarly article that appears in an academic journal. Peer-reviewed academic journals don't usually favour the publication of half-baked ideas and those articles that contain half-baked ideas are rarely recommended for publication. I recently had to decline an invitation to write an article for a scholarly journal because to do it justice I would have had to do a great deal of research, including, probably, travelling to various parts of sub-Saharan Africa. But I no longer have access to an academic library (owing to bureaucratic bungles over renewal of books at the Unisa library) and can't afford to travel to all the necessary places, even if we weren't living in a time of Covid.

But I think the publication of half-baked ideas in media such as blogs can stimulate discussion, and perhaps stimulate other people to bake them. The discussion can begin in blog comments, and the debate can continue in other media, like mailing lists and other forums, online or offline.

November 19, 2021

Fantasy, ecology and children's literature

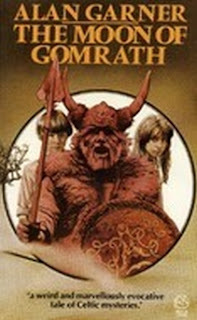

Immediately after the webinar I happened to finish reading the third volume of The Spiderwick Chronicles, and it ended with a trope that seemed very applicable: children meet elves who are hostile to humans because of the damage that humans cause to the environment. The same trope may be found in The Moon of Gomrath by Alan Garner, where the elves of Sinadon come to Fundindelve, and show a similar hostility to human children for the same reason.

Lucinda's Secret by Tony DiTerlizzi

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is the third book of the Spiderwick Chronicles. I've read the first, but the second was not in the library, so I'm having doubts about whether I'll be able to read and review the whole series, in which the Grace family go to live in an old house belonging to a great aunt, and find it has some strange inhabitants.

The main character seems to be Jared Grace, aged nine, with his twin brother Simon, and their older sister Mallory, aged 13. They discover a book about faeries, which apparently belonged to their great uncle, who disappeared many years before. But the faeries, or some of them, want the book, and seem determined to get hold of it, by fair means or foul. Each volume in the series is fairly short, about 100 pages, of which nearly half are taken up with illustrations. The ecology trope is seen here:

The leaf-horned elf sniffed. "We have long known that mankind is brutal. Once, at least, humans were ignorant. Now we would keep knowledge of our existence from you to protect ourselves.""You cannot be trusted. You cleave the forests." Lorengorm scowled and his eyes flashed. "Poison the rivers, hunt the griffins from the skies and the serpents from the seas. Imagine what you could do if you knew all of our weaknesses."

In The Moon of Gomrath the same trope appears:

... no elf has a natural love of men; for it is the dirt and ugliness and unclean air that men have worshipped these two hundred years that have driven the lios-alfar to the trackless places and the broken lands. You should see the smoke-sickness in the elves of Talebollon and Sinadon. You should hear it in their lungs. That is what men have done.

There is a similar trope in Prince Caspian by C.S. Lewis:

He remembered that he was, after all, a Telmarine, one of the race who cut down trees wherever they could and were at war with all wild things; and though he himself might be unlike other Telmarines the trees could not be expected to know this.

For more on this and similar themes see Inside Prince Caspian. Though in that case it is trees rather than elves, the theme of ecological damage is similar.

Another similarity in all three instances is that the children, though not necessarily personally responsible for the evil, nevertheless belong to the the race that has caused the evil, and are hated or feared for it. In other contexts, this phenomenon is known as "white privilege". In all three instances mentioned here, the children belong to a class that has been enriched by damage they have inflicted on the environment that others depend on, and the children have benefited from that enrichment. The children were not aware of the damage, having been insulated from it by their privileged position.

Another similarity in all three instances is that the children, though not necessarily personally responsible for the evil, nevertheless belong to the the race that has caused the evil, and are hated or feared for it. In other contexts, this phenomenon is known as "white privilege". In all three instances mentioned here, the children belong to a class that has been enriched by damage they have inflicted on the environment that others depend on, and the children have benefited from that enrichment. The children were not aware of the damage, having been insulated from it by their privileged position.In the webinar nobody mentioned capitalism as being responsible for damage to the environment, yet Alan Garner alludes to the Industrial Revolution as being responsible for the damage, and explicitly mentions the Age of Reason -- the Enlightenment, and thus the mentality of modernity.

In C.S. Lewis the context is more colonialism -- the Telmarines are conquerors, and implicitly propagate an ideology of Telmarine supremacy. A similar ideology characterises Weston, the villain of his adult science fiction series, with capitalism being represented by his partner Dick Devine who, while not an allegory of Cecil Rhodes, is at least cut from the same cloth. Both are combined in Prince Caspian.

I'm sure other instances of this trope could be found in children's literature -- environmental destruction, children as unconscious beneficiaries, and the resentful victims.

November 14, 2021

The Hollow Hills

The Hollow Hills by Mary Stewart

The Hollow Hills by Mary StewartMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

The second volume of Mary Stewart's Arthurian trilogy, written as an autobiography of Merlin the Enchanter and Prophet. In this volume, having engineered the conception of Arthur Merlin makes himself responsible for the young prince's upbringing though largely indirectly, as much of it is in the care of others he chooses.

The period in which the story is set has sometimes been called "the Dark Ages" by historians, because there are very few historical sources available for it. That period lasted from about AD 400 to AD 800, when applied to the British Isles, though other pares of Europe were less "dark", as there are is more historical source material available. But much of what happened in that period in Britain is anybody's guess, and that gives great freedom to a novelist who wants to write about it.

The problem of the Arthurian legend is that it was really only fully developed in the High Middle Ages, but Mary Stewart tries to make the setting authentic for the 5th century rather than the 12th. She tries to portray the relations between the different cultural groups in the British Isles -- the Celts, the Romano-British, and the old British. The Saxons, at this stage, appear only on the periphery, as a threat.

At one point Merlin becomes a hermit, looking after a chapel or shrine in the woods. He takes over the shrine when the previous guardian, Prosper, dies, and there is some ambiguity about which God or gods the shrine belongs to. I found this particularly interesting because a long-lost play by Charles Williams, The Chapel of the Thorn was recently found and published -- see my review here. Though the country that is the setting of Charles Williams's play is never named, its situation is sufficiently similar to the Green Chapel in Stewart's story to make an interesting comparison. I suspect that Mary Stewart's perceptions of the relations between Christianity and paganism at that period may owe more to 19th-century folklorists and is not as nuanced as that of Charles Williams.

The characters of Arthur and Merlin are well developed, and Merlin seems to have gained some confidence since the first book, because he is older and more mature, and also because of his travels, which are rather briefly described.

View all my reviews

November 9, 2021

On writing fiction

Here are two articles that may be of interest to writers, or potential writers of fiction.

I've sometimes wondered whether there's any point in writing stories that no one will want to read anyway. Is it just a way of filling in time between retirement and death? "Why kill time when you can kill yourself?" as one character said in a film I saw a long time ago. So this article is an encouragement to carry on writing:

But there is also the question of what to write, and, even more important, what not to write, and that is where this article comes in:

... which is a criticism of those who write fan fiction (fanfic) and write on National Novel-Writing Month (NaNoWriMo).

Now I have in the past challenged people to join NaNoWriMo and write a novel in the genre of Charles Williams.

I don't regret giving that advice, but I do see its limitations, having taken my own advice and tried to write such a novel. The critique I received, comparing it with other stories I had written, showed that trying to write a 50000-word novel in a month is not a very good idea, at least not for people who write stories the way that I do.

The problem is that journalism has deadlines, but novel-writing shouldn't, unless you are suffering from a terminal illness or are under a death sentence.

No matter how much editing, rewriting and revising one does, a novel written in a month is likely to have a lot of shortcomings that no amount of patching can fix, unless, perhaps, you are one of those people who can outline a plot well beforehand, and simply write to fill in the outline. But I'm not one of those. I often start writing a story and have no more idea than the characters in the story where it will end up.

Now I'm writing a story that leads me into unfamiliar territory, and so I have to check other books to see if I've got the background information right. One can't do that in a month when one is dependent on fortnightly.trips to the library. But I'd still like to see more stories in the genre of Charles Williams and the early Alan Garner, so, to my friends who like those authors I say: please get writing, but do find your own well and don't try to write fan fiction.

Most of the fiction I have tried to write have been children's stories (like the early Alan Garner), and some of my reviewers have compared them to Enid Blyton's "Famous Five" stories. I don't find the comparison flattering, because I never liked the Famous Five as a child, finding the very term "Famous Five" rather pretentious and silly, and preferred Blyton's "Adventure" and "Secret" series, which had more interesting plots, even if they weren't better written. And it surely doesn't take much to write better than Enid Blyton (What a surprise!)

An online friend, whose own writing was cited in the first article mentioned above, commented that he had written a few children's books, but was deterred from preparing them for publication, or self-publishing them on a site like Smashwords, because as an academic he would not be able to put them on his CV.

Now my academic field is one where works of fiction wouldn't be much use on one's CV, so I don't face his particular problem, but I still say don't let your manuscript moulder in a drawer or on a hard disk somewhere, but publish it on a site like Smashwords where anyone who wants to can read it.

I mention Smashwords because publishing there is dead easy.

They give you a template. You format your manuscript according to the template, upload it and it is done. The first time I did it, it was sent back for a few tweaks, but my subsequent books were accepted first time. And, if you want to publish on Amazon's KDP, a simple Search and Replace, on a copy of the manuscript, changing every instance of "Smashwords" to "Kindle", will do it for you though Smashwords also produces the MOBI format used by Kindle readers.

If your first few readers spot any typos you missed, you can upload a corrected version, and offer those readers a free coupon for the corrected version too.

How does this compare with commercial publishing?

If you don't need to put it on your CV, I think it compares quite well.

For my first children's novel I queried dozens of literary agents who said they handled children's books. I didn't get any rejections slips. None of them rejected it, they didn't want to read it at all. I thought writing books was more fun than writing query letters, and gave that up.

I have had a couple of academic books published by university presses. The most recent one, where I collaborated with two other authors, did not produce a single review, at least not any that I have seen. My most recent children's book, The Enchanted Grove, has had several reviews on the GoodReads site and elsewhere.

OK, these are not reviews from academic specialists in children's literature (I'd love to have a couple of those, if any such people could be persuaded to read it), and even more I'd love to have reviews from kids in the target age group (9-12), but at least there are reviews, whereas the book published by traditional academic publishers produced none. And while not all reviews are useful, a good review (which is not necessarily the same as a flattering one), can show you how to write better next time.

November 3, 2021

The Crystal Cave: an autobiography of Merlin the magician

The Crystal Cave (Merlin, #1) by Mary Stewart

The Crystal Cave (Merlin, #1) by Mary StewartMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

The first part of a biography of Merlin the prophet and magician, mentor of King Arthur, based on the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

It reads like a historical novel, though Merlin is not a figure of history, so it is probably most accurately described as a fantasy in the form of a historical novel. It is said that Geoffrey of Monmouth created the figure of Merlin by combining elements of the stories of two earlier prophets and adding a few bits of his own. Mary Stewart adds several details of her own to round out the figure of Merlin.

In this story he is the bastard son of a daughter of the King of South Wales, who refuses to reveal who is father was, and does not deny rumours that he was the son of the devil. In Stewart's story Merlin meets a hermit-prophet Galapas, who becomes his tutor, but runs away from home at the age of 12, fearing members of his own family.

As a fictional autobiography it makes a good story, but since it is written in the first person it gives a definite impression of the character of Merlin, which differs from that of other writers. Given the basic outline of the legend of Merlin (of which Mary Stewart gives a summary at the end, an author is given great freedom to shape that character as they wish, and in this book Merlin is shown as rather diffident and lacking in self-confidence. He has to be told by other people what he has prophesied, and even how he interpreted it.In this respect a more appropriate title for the book might have been The Reluctant Shaman.

Perhaps the weakest part of the book is the end, dealing with the conception of Arthur. I haven't read Geoffrey of Monmouth's original, so I'm not sure how much of the blame is his, and how much Mary Stewart's but it felt like an inauspicious beginning for a predicted marvellous reign. Merlin's grand scheme seems pointless, as does Uther's reaction

Other authors, medieval and modern, have written Merlin with a very different character, and I've wound some of them more convincing than this one.

View all my reviews