Sawyer Paul's Blog, page 194

May 24, 2011

Editing Fair to Flair. Should be done in a few days. Our copy...

Editing Fair to Flair. Should be done in a few days. Our copy editor at Gredunza Press, who is not a wrestling fan at all, did a great job making the language and grammar consistent. It's going to be a great issue. If we only ever do this one (and we won't, don't worry), then I'll still be incredibly proud of everyone who contributed, everyone who reads it, and everyone it touches.

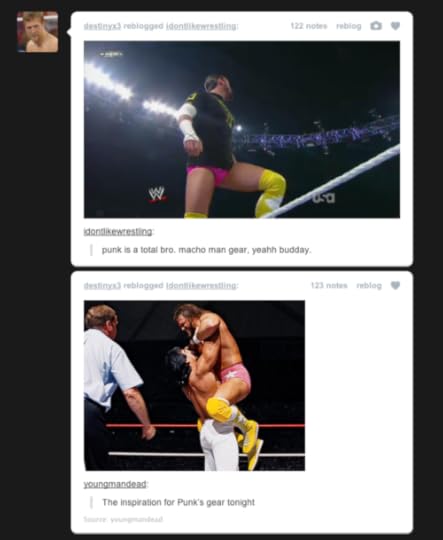

At its apex, Macho Man was wrestling

Of course, you never stop liking wrestling. When word broke last week that a car accident had claimed Savage, I couldn't believe how many people emailed me about it. He lasted 58 years, forever by wrestling standards, but it still felt too soon. I liked knowing Savage was out there, giving insane interviews and leaving people generally perplexed. The scope of his career can't compare to those of Shawn Michaels or Ric Flair, but you won't find a more meaningful apex: He peaked right as wrestling peaked, ushered in a more athletic era and introduced eye candy (Elizabeth) to a fan base that desperately needed it. We look back at the '80s ironically now — everything is much funnier now than it was then, whether it's outfits, haircuts, movie plots, political incorrectness or even a sweeping lack of self-awareness. Savage tapped into those faults better than anyone. He was the '80s, for better and worse.

May 23, 2011

Checks and Balances, Volume 1

I listened to the monthly Fair to Flair show this week, and I'll get the requisite gushing and biased stuff out of the way because I'm way more curious in reacting to K Sawyer Paul's points about the F4W/Observer and its faults/successes in how it treats wrestling. I want to be (oh god) fair to the sides I think can seem reactionary, but I also know that there are a lot of completely accurate problems.

Trey goes on to transcribe some of our points from the podcast (this was deep into the second hour, so you know he's interested) and adds fuel to the fire we started.

I feel I should perhaps give a quick memo to everyone who thinks I'm out to discredit Bryan Alvarez or anyone who works in the mainstream-approved corners of the IWC. I'm not. I wish them well, and I know they have their good points, and I don't ever want to hurt someone's ability to make a living. What I am out to do is discredit this notion that we get in terms of content from the "professional" wrestling journalists is what we, the "lesser" wrestling journalist, should emulate, admire, and support, simply because these people have been doing this for a long time. In fact, I think if they should be considered more professional than we are, then we should hold these writers to a higher standard. They should be consistently delivering quality content that makes us happy to be wrestling fans. And while I believe they are certainly capable of doing so, I don't believe they are. I believe they coast on platitudes of longstanding complaints, longheld beliefs, and oft-misunderstood ideas of this art form (if they have ever even considered it as such is unknown to me).

The fact is, The Observer, PWI, and others have held a very high spot in wrestling media for a long, long time. I, for the life of me, have no idea why. Have you read one of their printed magazines or newsletters lately? It makes your goddamn eyes bleed. They pander, patronize, and insult our intelligence, and I honestly don't know who they're targeting or trying to fool.

Their sole value, as far as anyone can defend them to me, is that they are somewhat adequate historians. They are pretty good at telling you what happened, yes, but only if you look at wrestling as a fake sport. Mainstream wrestling reports often miss the important things. Go read Powell's review of Wrestlemania and then compare it with this. You want to tell me you prefer it the first way?

I don't know how to end this rant, other than to say, keep reading. I'll have more on this soon.

"I need money for bourbon and anime."

- Jamie Bryan Dobbins

It is therefore easy to understand why out of five wrestling...

It is therefore easy to understand why out of five wrestling matches, only about one is fair. One must realize, let it be repeated, that 'fairness' here is a role or a genre, as in the theater: the rules do not at all constitute a real constraint; they are the conventional appearance of fairness. So that in actual fact a fair fight is nothing but an exaggeratedly polite one: the contestants confront each other with zeal, not rage; they can remain in control of their passions, they do not punish their beaten opponent relentlessly, they stop fighting as soon as they are ordered to do so, and congratulate each other at the end of a particularly arduous episode, during which, however, they have not ceased to be fair. One must of course understand here that all these polite actions are brought to the notice of the public by the most conventional gestures of fairness: shaking hands, raising the arms, ostensibly avoiding a fruitless hold which would detract from the perfection of the contest.

Thus the function of the wrestler is not to win; it is to go...

Thus the function of the wrestler is not to win; it is to go exactly through the motions which are expected of him. It is said that judo contains a hidden symbolic aspect; even in the midst of efficiency, its gestures are measured, precise but restricted, drawn accurately but by a stroke without volume. Wrestling, on the contrary, offers excessive gestures, exploited to the limit of their meaning. In judo, a man who is down is hardly down at all, he rolls over, he draws back, he eludes defeat, or, if the latter is obvious, he immediately disappears; in wrestling, a man who is down is exaggeratedly so, and completely fills the eyes of the spectators with the intolerable spectacle of his powerlessness.