MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 157

August 11, 2015

Medieval Sword Carries Mysterious Inscription

This 13th-century sword with a gold inscription was likely made in Germany, but was found at the bottom of the River Witham in 1825.Credit: The British Museum

This 13th-century sword with a gold inscription was likely made in Germany, but was found at the bottom of the River Witham in 1825.Credit: The British MuseumA medieval sword inscribed with a mysterious message is stumping researchers and causing a stir among armchair historians.

The 13th-century weapon was found in the River Witham in Lincolnshire, in the United Kingdom, in 1825. It now belongs to the British Museum, but is currently on loan

to the British Library, where it's being displayed as part of an exhibit on the 1215 Magna Carta.

to the British Library, where it's being displayed as part of an exhibit on the 1215 Magna Carta.The sword looks fairly ordinary at first glance. Weighing in at 2 lbs., 10 ounces (1.2 kilograms) and measuring 38 inches (964 millimeters) long, the weapon is steel, with a double edge and a hilt shaped like a cross. But on one side of the sword is a mysterious inscription, made by gold wire that has been inlaid into the steel, which reads, "+NDXOXCHWDRGHDXORVI+." [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

What does this strange group of letters mean? No one knows for sure, according to the British Library, which recently posted information about the weapon on its website, along with a request for readers to help crack the seemingly incomprehensible code.

Is the message some kind of magical incantation, meant to empower the weapon's owner with mystical abilities during battle? Perhaps the inscription is a religious blessing, or maybe it's just the complicated signature of whoever forged the weapon. Those who read the British Library's blog post put these and many other theories forward regarding the sword's enigmatic message.

[image error]

[image error]

A close up of the sword's mysterious inscription.

A close up of the sword's mysterious inscription.Credit: The British MuseumView full size imageDozens of commenters chimed in to help solve the mystery. And luckily, one of those commenters had a lot of insight into the history of inscribed swords in Europe. Marc van

Hasselt, a graduate student of medieval studies at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, has studied similarly inscribed swords and said that these weapons were "all the rage" in 13th-century Europe. The British Library recently updated its blog post with more information from van Hasselt.

Hasselt, a graduate student of medieval studies at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, has studied similarly inscribed swords and said that these weapons were "all the rage" in 13th-century Europe. The British Library recently updated its blog post with more information from van Hasselt.Wordy weaponry

Many inscribed swords have been found in countries including Poland, France, Sweden, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, making the River Witham sword "part of a large international

family," according to van Hasselt.

family," according to van Hasselt.In 2006, researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden (as well as several other institutions) started the Fyris Swords Project, a research project dedicated to figuring out the historical context in which these inscribed medieval swords were used.

The River Witham sword was forged in Germany, which was then the blade-making center of Europe, according to the British Museum. And pre-Christian Germanic tribesman inscribed runes onto their swords, axes and armor to "endow the items with magical powers," the Fyris Swords Project researchers wrote in a paper published in the journal Waffen- und Kostümkunde (Weaponry and Costumes) in 2009.

It's possible that this ancient tradition was carried over to Christian times and that the inscriptions on the blades were therefore meant to "invoke God’s holy name and his grace to gain support and protection

in battle," according to the researchers.

in battle," according to the researchers.Such swords were likely owned by wealthy warriors, according to the British Museum, which speculates that the River Witham sword belonged to a knight or some other rich individual who rode into battle during the crusades of the late medieval period. The British Museum also suggests that such swords may have been a part of the ceremony in which a man became a knight and vowed to defend the church.

Cracking the code

Even though historians are fairly certain why inscribed swords were popular in the medieval period and who owned them, they still aren't sure just what these swords actually say. Interpreting the inscriptions on the blades is like "trying to crack a mysterious code," according to the Fyris Swords Project researchers.

While historians aren't entirely sure what language the letters on the sword represent, they are fairly certain that the letters are a short-form version of Latin, according to van Hasselt, who said that Latin was the "international language of choice" in 13th-century Europe. The first two letters on the River Witham sword are ND, which van Hasselt said might be a kind of invocation that stands for "Nostrum Dominus (our Lord) or Nomine Domini (name of the Lord)."

The XOXcombination that follows could refer to the Holy Trinity of the Christian faith. And the two plus sign-shaped symbols before and after the inscription are likely Christian crosses, according to the Fyris Swords Project researchers.

This sort of speculation about what the sword's inscriptions might represent has been going on for more than a century (researchers have been publishing their interpretations of the inscriptions in the journal Waffen- und Kostümkunde since 1904). The variety of the letter sequences on the swords makes it clear that the inscriptions are not general statements (i.e., a standard blessing written out in short form). Quite the opposite is true, according to the researchers.

"[The] inscriptions (even though sometimes showing a constancy of letters) are extremely variable and appear to be very personal. One might say the individual secret of every sword bearer. It must have been a special dictum [saying] so obvious and so self-evident to him that it was not necessary to spell out its significant meaning," the researchers said.

Commenters on the British Library website have suggested a number of possible interpretations of the River Witham sword's inscription (which you can read under the library's blog post). But just as with the other inscribed swords found throughout Europe, it's unlikely that anyone will be able to say with complete certainty just what message this medieval sword conveys.

Live Science

Published on August 11, 2015 07:11

9 unsolved historical mysteries

History Extra

Who was Jack the Ripper, what happened to the Mary Celeste, and did Richard III really murder the princes in the Tower? These are some of the biggest historical mysteries of all time. Here, after scouring 1,000 years of public records at the National Archives in search of answers, Dr David Clarke, the author of Britain’s X-traordinary Files, charts nine of the greatest unsolved puzzles of modern times

1) The Mary CelesteWhat became of the crew and passengers of this British-American brigantine remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the sea. The name has since become synonymous worldwide with derelict ‘ghost ships’.

The Mary Celeste was found drifting 400 miles east of the Azores by the crew of another cargo-carrying vessel, the Dei Gratia, on 5 December 1872. The leader of the boarding party told a British board of inquiry at Gibraltar he found the ship was “a thoroughly wet mess”, with possessions left behind and the lifeboat missing.

No trace of Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs, his wife and their young daughter or the seven experienced crew members has ever been found. Many ingenious theories have been put forward by writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle to explain what happened to them. My favourite comes from a 1965 episode of the BBC series Dr Who, where the frightened crew jump overboard when the Daleks materialise on the ship while chasing the occupants of the TARDIS.

2) Jack the RipperThe true identity of this Victorian serial killer continues to elude us 126 years after the gruesome killing spree in London’s East End in 1888. In the latest development, an ‘armchair detective’ claims DNA evidence from the shawl of one of the five known victims has identified Polish émigré Aaron Kosminski – one of a list of key suspects – as the man also known as ‘Leather Apron’, or ‘the Whitechapel Murderer’.

A small cottage industry, Ripperology has grown up around the murders with investigators such as Patricia Cornwell and Russell Edwards sifting through surviving evidence in search of a ‘prime suspect.’ Among the wild theories that have become legends is one that depicts Jack as a deranged surgeon who killed the women as part of a conspiracy to protect a member of the royal family.

Professor William Rubinstein describes this story as “palpable nonsense from beginning to end”. He believes it is the very elusiveness of the solution that continues to make the Ripper mystery so attractive to writers and historians.

3) Kenneth Arnold’s ‘flying saucers’The birth of the modern UFO phenomenon can be traced to a sighting by private pilot Ken Arnold of nine peculiar-shaped flying objects over the Cascade Mountains of Washington on the afternoon of 24 June 1947. Arnold told newsmen the bat-wing shaped objects moved like a saucer would “if you skipped it across the water”. He calculated their speed as faster than the most advanced jet aircraft of that time.

A sub-editor came up with the phrase ‘flying saucers’, and the media coverage that followed triggered off an epidemic for seeing things in the sky that continues to this day. Two weeks after Arnold’s sighting, the US Army Air Force announced that wreckage from a ‘flying disc’ had been recovered from a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico.

A modern myth was born, but ever since controversy has raged about what it was that Arnold actually saw. In my opinion, the most likely explanation is a flock of American white pelicans flying in echelon formation. But no one will ever know for sure.

4) The Devil’s FootprintsEarly on the morning of 9 February 1855, people in towns across southern Devon awoke to find a single line of hoof-like marks in the deep snow as if they had been branded with a hot iron. The Times said the marks were found over a distance of 40 miles on both sides of the Exe, as if “some strange and mysterious animal endowed with the power of ubiquity” had created them during the night.

Explanations ranged from an escaped kangaroo, badgers and mice, to a balloon trailing a horseshoe-shaped grappling rope. Superstitious people preferred to believe they were the work of the devil himself. In its summary of the popular theories at the time, a writer in The Illustrated London News said “no satisfactory solution” had been found, and “no known animal could have traversed this extent of country in one night… neither does any known animal walk in a line of single footsteps, not even a man”.

5) The Shroud of TurinThis piece of linen cloth kept in the Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Turin, northern Italy, is one of the most closely investigated objects in human history, yet it retains its secrets. The sacred relic is believed by many Christians to be the shroud in which Jesus of Nazareth was buried.

There is no doubt that it bears a negative imprint of the face and outline of the body of a man who has suffered injuries consistent with crucifixion, but scientists have been unable to reach a consensus about how it was created. Radiocarbon testing by three laboratories in 1988 dated the cloth to the Middle Ages, and this was proclaimed by some as proof it was a medieval fake. But this interpretation remains the subject of intense debate, leading a former editor of Nature, Philip Ball, to declare that the relic remains shrouded in mystery.

6) Richard III and the princes in the TowerIn 2012 the skeleton of the last Plantagenet king of England, Richard III, was unearthed from beneath a council car park on the site of Greyfriars in Leicester city centre. The dig that unearthed his remains was instigated by Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society as a direct result of a “strange feeling” she had when visiting the site.

This apparent example of psychic archaeology is not the only mystery that surrounds Richard’s life and death. His precise role in the fate of his two nephews – popularly known as ‘The princes in the Tower’ – remains a subject of enduring mystery. The 12-year-old Edward and his nine-year-old brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, the sons of King Edward IV, were lodged in the Tower of London by their uncle, Richard, at the time of their disappearance in 1483.

No one knows exactly what happened to them, but a box containing two small human skeletons was found near the White Tower in the 17th century and, at the time, was widely believed to be the remains of the princes.

7) The Solway SpacemanOn the afternoon of 23 May 1964, an employee of the Cumbrian fire service, Jim Templeton, took photographs of his wife and daughter during a day out at a local beauty spot on the Solway Firth. When he collected the photographs from a chemist, the assistant told him it was a shame one was “spoiled by the man in the background wearing a space suit”.

Sure enough, one image of his youngest daughter Elizabeth clearly shows an enigmatic ‘figure’ floating behind her head. The ‘spaceman’ is dressed in a white suit that resembles those worn by NASA astronauts at the time.

The photograph was examined by Kodak and scrutinised by detectives from the Cumbrian police, who were unable to explain it. Jim Templeton died in 2011 without learning the true identity of the ‘Solway spaceman’. The image remains one of the most perplexing in the history of anomalous photography.

8) MothmanOne dark night in November 1966, four American teenagers claimed they saw a huge bird-like monster with glowing red eyes while cruising along a back road near Point Pleasant in rural West Virginia. They claimed it rose into the air, unfolded its bat-like wings, and pursued them as they sped away in terror. The next morning the sheriff’s office held a press conference, and the media dubbed the creature ‘Mothman’ after the Batman series that was showing on TV.

Encounters with the demonic ‘bird’ inspired the 2002 movie The Mothman Prophecies, directed by Mark Pellington. The film was based upon journalist John Keel’s book that chronicled an outbreak of uncanny experiences in the Ohio Valley. He believed the creature was linked in some mysterious way with the collapse of the Silver Bridge in Point Pleasant in December 1967 that killed 46 people, including some mothman witnesses.

9) Monsters of the DeepDo the depths of our oceans hide undiscovered species of animal such as the great ‘sea serpent’ that was sighted by the captain and crew of HMS Daedalus near the island of St Helena in 1848?

Among the files at the National Archives and the Natural History Museum I found first-hand reports of similar creatures in records from the late 19th to the early 20th century, including one by Arthur Conan Doyle, author of The Lost World. Could it be that, as the museum’s former keeper of zoology, William Calman, told a puzzled witness in 1929: “…we are not so rash as to suppose that we yet know all of the inhabitants of the sea and it is within the bounds of possibility that you saw some animal that has never been captured or described”.

If so, where have they all gone?

Dr David Clarke is the author of Britain’s X-traordinary Files, published by Bloomsbury on 25 September. To find out more, click here.

.

Published on August 11, 2015 06:59

History Trivia - Rodrigo Borgia becomes Pope Alexander VI

August 11

480 BC Greco-Persian Wars: Battle of Artemisium – the Persians won a naval victory over the Greeks in an engagement fought near Artemisium, a promontory on the north coast of Euboea (island of central Greece in the Aegean Sea).

1492 Rodrigo Borgia became Pope Alexander VI. One of the most notorious men to sit on the papal throne, Alexander VI was worldly, ambitious and ruthless. However he was a patron of the arts (Raphael, Michelangelo and Pinturicchio) and also encouraged the development of education as evidenced by the issuance of a Papal Bull at the request of William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen, and King James IV of Scotland, founding King’s College, Aberdeen.

480 BC Greco-Persian Wars: Battle of Artemisium – the Persians won a naval victory over the Greeks in an engagement fought near Artemisium, a promontory on the north coast of Euboea (island of central Greece in the Aegean Sea).

1492 Rodrigo Borgia became Pope Alexander VI. One of the most notorious men to sit on the papal throne, Alexander VI was worldly, ambitious and ruthless. However he was a patron of the arts (Raphael, Michelangelo and Pinturicchio) and also encouraged the development of education as evidenced by the issuance of a Papal Bull at the request of William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen, and King James IV of Scotland, founding King’s College, Aberdeen.

Published on August 11, 2015 01:30

August 10, 2015

Stoner Shakespeare? Scientists say pipes from playwright's garden contain cannabis

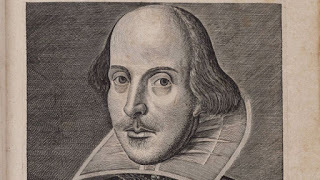

This engraving of a man identified as William Shakespeare appears on the front of a First Folio of Shakespeare's plays dating from the early 17th century (Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)

This engraving of a man identified as William Shakespeare appears on the front of a First Folio of Shakespeare's plays dating from the early 17th century (Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)Fox News

Did the greatest playwright the world has ever known have a taste for the wacky tobaccy? Did William Shakespeare have a case of the munchies while penning "Macbeth"?

The answer may very well be "yes" after a group of South African scientists found that clay pipes recovered from the garden of the Bard's home contain traces of cannabis.

The researchers examined fragments of 24 clay pipes that were recovered from the garden of Shakespeare's home in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, as well as from surrounding houses. After examining the fragments using a gas chromatography technique, the scientists found that eight of the pipes contained traces of cannabis, one contained nicotine, and two contained traces of cocaine derived from Peruvian coca leaves. Four of the pipes containing cannabis came from Shakespeare's property.

Professor Francis Thackeray of the University of Witwatersrand, who headed the study, writes that several kinds of tobacco were known to early 17th-century Englishmen. The earliest specimens of nicotine and coca leaves may have been imported by explorers Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake, respectively.

Thackeray has a longstanding interest in Shakespeare's possible use of drugs. The Sydney Morning Herald reports that in 1999, he wrote an academic paper titled "Hemp as a source of inspiration for Shakespearean literature?"

This may all be much ado about nothing, as there's no conclusive evidence that Shakespeare ever used cannabis himself. However, Thackeray notes that early performances of Shakespeare's works likely took place in smoke-filled rooms full of puffing members of the Elizabethan gentry.

"One can well imagine the scenario in which Shakespeare performed his plays in the court of Queen Elizabeth, in the company of Drake, Raleigh and others who smoked clay pipes filled with 'tobacco'," he writes.

A case of smoke them if you've got them, perhaps?

Published on August 10, 2015 07:54

Medieval tourism: pilgrimages and tourist destinations

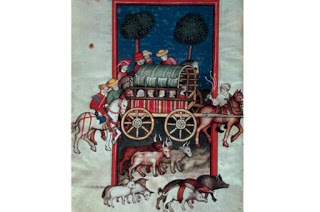

Jacob’s Journey, manuscript illumination, c1411. Hospitals and monastic houses would spring up alongside popular travel routes. (Credit: AKG Images)

History Extra

Recent research suggests medieval tourism was widespread, writes Paul Oldfield, and existed in a world of pilgrimage and classical curiosities.

One enduring perception of medieval Europe is of a static, confined world in which most people rarely travelled beyond their immediate locality, and when they did, movement was undertaken primarily for pragmatic reasons. Research in recent decades has significantly revised this picture – high numbers of people regularly travelled both short and long distances, and, more interestingly, some of this movement was driven by motivations which we might today associate with the modern-day tourist. If we readjust our modern understanding of tourism, and place it into a medieval context, we can soon see that many medieval people travelled for renewal, for leisure, and for thrill-seeking, and that an abundance of medieval ‘tourist’ services catered for these activities.

Southern Italy and Sicily, in the 11th and 12th centuries, offers a particularly vivid illustration of this phenomenon. Due to its position in the central Mediterranean, the region has always been pivotal to wider currents of movement and travel. And from the later 11th century it began to attract even more European visitors for three main reasons. Firstly, southern Italy and Sicily was conquered by bands of Normans who unified a region which had previously been politically fragmented and host to a patchwork of Greek Christians, Latin Christians, Jews and Muslims. Indeed, by 1130 the Normans had created a powerful new monarchy in the middle of the Mediterranean which had for centuries been dominated by Muslim sea-power. The Normans, therefore, enabled Christian shipping and travellers to move more securely and freely.

Secondly, various factors converged to boost the popularity of international pilgrimage, and after the beginning of the crusading movement in 1095 Europe experienced its golden era of devotional travel, much of which moved through southern Italy and Sicily en-route to Jerusalem.

Thirdly, in the 12th century, Europe underwent a cultural renaissance; learned individuals travelled further afield to seek knowledge, to uncover classical traditions, and to encounter alternative experiences. Southern Italy and Sicily, steeped in classical history and with a Greek and Islamic past,attracted visitors avid to imbibe both ancient and eastern learning. The result of these three combined strands saw an influx of visitors to the region, who were not migrants, conquerors, or traders, but travellers in their own right, what we might identify as tourists.

Scenes from the Life of Saint Stephen: Pilgrims at the Saint’s Tomb by Bernardo Daddi (c1290–1350). (Credit: Scala)

Pilgrimage offers perhaps the most apparent medieval equivalent of the tourist trade. Some pilgrims travelled not solely for pious motivations – a pilgrimage might cloak political and economic agendas, or be imposed as a judicial punishment. But whatever the incentive, adopting the pilgrim’s staff conferred a theoretical and universal status in which the individual acquired a new identity forged in the act of the journey to a particular shrine.

Between the pilgrimage’s start and end points, while the pilgrim was traversing alien territories, he was encouraged to imitate Christ, to experience challenge and hardship and to consider his own salvation. Indeed, at many shrines along their way, pilgrims practised an act known as incubation, in which they stayed and slept near the holy tomb, sometimes for days, in order to receive cures or divine revelations. In this sense, the pilgrim in his fundamentals was comparable to many modern-day travellers: an experiential traveller, absorbed in the act of journeying, partaking in a detox – not merely of the body as at a luxury spa, but also of the soul – like a modern meditative retreat achieved while on the move.

As international pilgrimage expanded dramatically in the central Middle Ages, southern Italy took on a key role in the pilgrim’s journey; it acted as a bridge to salvation by connecting two of the greatest shrine centres of the Christian world: Rome and Jerusalem.

This ‘bridge’ was a geographic reality. Southern Italy possessed one of medieval Europe’s more sophisticated travel infrastructures. Being so close to the heart of the former Roman empire, it still boasted several functioning Roman roads – the motorways of the Middle Ages – which linked into the Via Francigena, the main route that brought travellers from western Europe across the Alps to Rome. Roads such as the Via Appia and Via Traiana enabled travellers to move across the south Italian Apennines to the coastal ports of Apulia, while the Via Popillia wound through Calabria and directed visitors to the bustling Sicilian port of Messina. Thanks also to the Norman conquest, the region equally offered relatively safe maritime travel.

South Italian ports hosted fleets of well-informed local ships as well as those of the emergent commercial powers of Genoa, Pisa and Venice that traded in them.

Strong foundationsThe pilgrim could therefore rely on secure, efficient and direct travel connections. At the same time new hospitals, inns, bridges and monastic houses emerged along southern Italy’s main pilgrim routes, or near shrines which foreign visitors would attend.

The junctions at Capua, and Benevento, and the major Apulian and Sicilian ports (which often hosted pilgrim hospitals belonging to Holy Land military monastic orders – the Templars and Hospitallers), were full of such buildings offering shelter and sustenance to the traveller.

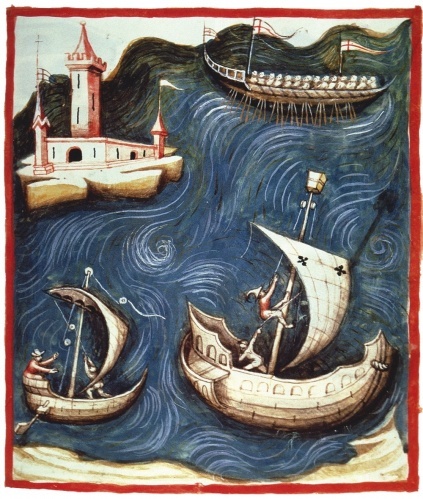

Unfortunately, as no reliable statistical data exists on how many travellers, pilgrims and crusaders (the three often indistinguishable) traversed these roads, and sailed to the Holy Land from these south Italian ports, we must rely on indirect evidence that suggests the region was one of the most frequented in the medieval world. This evidence can be found in the creation of all that travel infrastructure, and in contemporary accounts of the region’s ports teeming with travellers.

One commentator of the First Crusade noted that “many went to Brindisi, Otranto received others, while the waters of Bari welcomed more”. The Spanish Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr, passing through Messina in 1184, described it as a frenetic port adapted to foreign travel; it was a “market of the merchant infidels [ie Christians], the focus of ships from the world over, and thronging always with companies of travellers by reason of the lowness of prices… Its markets are teeming, and it has ample commodities to ensure a luxurious life. Your days and nights in this town you will pass in full security.”

A 14th-century tin alloy pilgrim’s badge depicting the Madonna with child. (Credit: AKG Images)

Later, in the mid-13th century, the English chronicler Matthew Paris produced a superb illustrated strip-map showing a travel itinerary from London to the Holy Land in which he pinpointed Apulia and the port of Otranto as the best route, orientating the reader to Otranto pictorially through a series of symbols and the image of a boat.

The foreign visitors to the region were of diverse social status. Most of the surviving evidence focuses on elite travellers – kings, counts, bishops – primarily because their status and wealth drew comment. But travel, and pilgrimage in particular, was also undertaken by the very poorest. Monastic rules outlined their monks’ duty to offer free hospitality to travellers, and we have many instances of poor pilgrims visiting Christendom’s most far-flung shrines. One poverty-stricken man, for example, from southern Italy had been able to visit the Holy Sepulchre and the shrine of St Cataldus at Taranto primarily through the proceeds of begging. It was also good advertising for shrine centres to be seen to cater for all backgrounds. Indeed, attracting foreign visitors was, as it is today, desirable and lucrative – they spent money on local services and profitable tolls. Like today’s travel agents, the guardians of many of southern Italy’s shrine centres targeted, and competed for, travellers.

The iconography within some shrine complexes catered for the pilgrim’s transcendental mindset with images echoing the theme of salvation and depicting Christ as a pilgrim. Texts were also produced to show, for example at the shrine of St Nicholas the Pilgrim at Trani, that the saint entombed within had a particular penchant for saving pilgrims. The city of Benevento produced a treatise in c1100 which attempted to divert pilgrims to its own shrines and away from the popular one of St Nicholas’ at Bari by slandering the latter city’s hospitality towards foreign visitors; it claimed Bari was a “merciless land, without water, wine and bread”.

But many south Italian shrines did not need to produce such ‘travel brochures’, as they were already renowned across Europe. The likes of St Nicholas’ at Bari, St Matthew’s at Salerno, St Benedict’s at Montecassino and St Michael’s at Monte Gargano, received a vast influx of visitors, and provided vital spiritual release points as the pilgrim travelled to wherever his final destination may be.

Unsurprisingly, the Norman rulers of southern Italy were eager to portray themselves as protectors of pilgrims, and issued legislation to back this up. However, the need for protection also revealed the dangers of travel. The threat of robbery, shipwreck and disease was omnipresent. In the 1120s, the north Italian St William of Montevergine aborted his pilgrimage to Jerusalem after he had been mugged in Apulia; no wonder pilgrims often travelled in groups.

Many pilgrims suffered from debilitating conditions, and struggled to cope with the demands of medieval travel. Many died passing through southern Italy. One chronicler of the First Crusade saw the drowning of 400 pilgrims in Brindisi harbour. At least dying as a pilgrim brought the hope of salvation – the medieval equivalent of travel insurance.

Southern Italy also served not merely as a logistical bridge to salvation, but as a metaphorical one too. These potentially fatal outcomes were indeed part of the experience and attraction of travel that many pilgrims embraced. Redemption required suffering and this could certainly be found in the demanding setting of southern Italy and Sicily. In modern terms the region provided a superb outdoor adventure experience for the thrill seeker, a sinister landscape steeped in supernatural, classical and folkloric traditions which were channelled back to western Europe as travel increased in the central Middle Ages.

Fearsome tidesSouthern Italy’s landscape was characterised by features that elicited wonder and fear. Its surrounding seas could be treacherous, especially the busy Straits of Messina, full of whirlpools and tidal rips. The Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr described the waters as boiling like a cauldron, and suffered a near-fatal shipwreck in the Straits in the 1180s.

Unsurprisingly, it was here that classical legend located the two sea monsters named Charybdis and Scylla, a vortex and a giant multi-headed sea-dog respectively. Commentators like the Englishman Gervase of Tilbury attempted to de-bunk these legends in the 12th century (he believed the whirlpools were created by the release of winds trapped below the seabed) but in doing so showed that many believed them to be real and/or were avidly interested in such tales. Indeed, the famous Hereford Mappa Mundi, dating to the late 13th century, offers a particularly vivid portrayal of the two sea monsters lurking in Sicilian waters.

Boats on the Sea, 14th century. The treacherous waters around southern Italy gave rise to many myths and legends. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

Southern Italy, as today, was also a hotspot for seismic activity. Several eruptions were attested in the Middle Ages at Vesuvius and Etna, while earthquakes were a regular feature: one which struck Sicily in 1169 was said to have killed 15,000 people at Catania. While some medieval commentators tried to analyse these events in a natural, scientific framework, many still viewed them as portentous signs, often indicating God’s disapproval.

The region’s volcanoes were endowed with even greater potency through a set of myths connecting them to the entrance to hell. Increased medieval interest in Virgil, the ancient poet and author of the Aeneid, led to renewed Vesuvius and the gateway to the Underworld; for it was there that Virgil’s hero Aeneas appears to have located it. Gervase of Tilbury noted the “spine-chilling cries of lamenting souls” heard in the vicinity of Vesuvius and who were apparently being purged in the Underworld.

Medieval commentators also spoke metaphorically of the “infernal torments” and “cauldrons” of Sicily. In the 12th century the diplomat Peter of Blois said that the island’s mountains “are the gates of death and hell, where men are swallowed by the earth and the living sink into hell”.

Land of legendsA strange and beguiling world materialised in 12th-century southern Italy, one that seemed to exist halfway between heaven and hell, and must have challenged the medieval visitor’s psychological landscape to its very core.

The reviving 12th-century interest in the classical past also contributed to the aura of curiosity, danger and attraction which southern Italy exerted on visitors. Alongside those ongoing tales of Scylla and Charybdis, we find the revival of legends on Virgil and his supernatural protection of Naples (where he was allegedly buried).

Gervase of Tilbury recorded some of these in detail: Virgil’s protection of the city from snakes, an Englishman who found Virgil’s bones in the 1190s with a book of magic, and the city gate where Virgil bestowed good fortune on those passing through the correct side.

Dante and Virgil, the Dragon and the Sea Monster, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

In c1170 a Spanish Jewish traveller, Benjamin of Tudela, passed Pozzuoli near Naples and marvelled at the sight of an ancient city submerged just off the coast where “one can still see the markets and towers which stood in the midst of the city”. Benjamin also noted Pozzuoli’s famous hot spring baths which “all the afflicted of Lombardy visit [...] in the summertime” to benefit from the restorative properties of its waters. Indeed, many travellers also came to the region to access and benefit from cutting-edge medical knowledge, the fusion of Arabic and ancient Greek learning, available at the great medical school of Salerno.

Another 12th-century English author, Roger of Howden, also included within one of his chronicles a literary tourist guide highlighting sites in southern Italy associated with Pontius Pilate and Virgil. The great 13th-century preacher Jacques de Vitry railed against people travelling to witness the bizarre, and it is clear that many of the accounts we have mentioned were tailored for an inquisitive audience, a segment of which were more than likely to visit southern Italy.

It would seem therefore that medieval travellers displayed traits which reflect aspects of our modern understanding of tourist travel, and particularly the trend for travel which produced transformative and morally meaningful experiences. Of course, to avoid obvious anachronism, the parallels between medieval and modern must remain loose, and account for the multiple differences that developed in the intervening centuries.

Nevertheless, medieval people travelled regularly, and sometimes long distances, encountering lands that were unfamiliar and challenging. But these challenges and new experiences were actually often sought as ends in themselves. Southern Italy encapsulated these trends – and offered an experience for travellers in all their guises. It had developed travel and service infrastructures, it catered for those seeking spiritual detox, for those who were interested in the distant past and in intellectual nourishment, and for those who sought physical and psychological tests – its volcanoes, earthquakes, volatile seas, and entrances to the Underworld made the region akin to a modern-day theme park.

For the medieval traveller, salvation, life enrichment and damnation all sat together in southern Italy – helping to create an alluring travel hotspot.Dr Paul Oldfield is a senior lecturer in medieval history at the University of Manchester.

Published on August 10, 2015 07:42

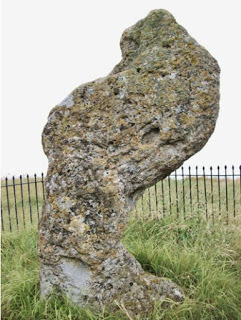

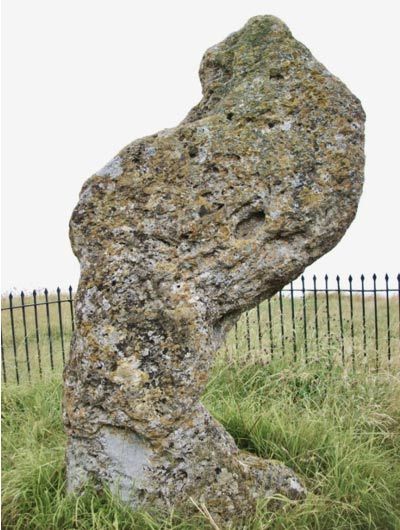

Skeleton of a High Status Spiritual Woman Unearthed Near Rollright Stones in England

Ancient Origins

Legend has it that centuries ago a witch turned a would-be king of England and his men and knights to stone, which still stand and are among the Rollright Stones circle at Warwickshire. Now a new legend has cropped up: A 7th century AD skeleton recently unearthed at the site is being called the witch who turned the ambitious men to stone.

The woman stood between 4 feet 11 inches and 5 feet tall (about 152 cm) and was buried with a Roman patera or bronze drinking vessel, a large amber bead and an amethyst set in silver. The patera is only the fifth found in England. She also had with her a large spindle whorl, which ITV.com says indicates that “Rita,” the Saxon pagan Rollright Witch, as she is being called, was a spiritual woman of high status.

The person who found the grave is Charles Wood. He was using a metal detector at the Rollright Stones with friends. He explains to ITV:

'This was more of a social event as we weren't expecting to find much. The ground is difficult to dig and you normally just find bottle caps from the Rollright Fayre they hold here. When my metal detector made a faint murmur I knew I'd have to dig down deep, but thought it would only be a plough tooth that had been pressed into the ground. I got 14 inches down and a small bronze rim appeared, but it seemed in too good condition to be anything significant. As I dug further though I saw it had a handle and it soon became obvious it was a patera, which is a very significant find. There's a myth around here of the Rollright Witch, and this find is certainly very interesting because of the spiritual element. I'm not saying anything for sure, but there's no smoke without fire. It was a once in a lifetime find. I could detect for the next 14 years and not find anything like it.'The Weird Wolds of Yorkshire: Inside the Mysterious Wold Newton TriangleMetal detectorist uncovers Roman treasure hoard in EnglandElevated Origins: Radical new theory suggests Stonehenge was base of an above-ground celestial altarBritish Archaeologists Take on Treasure HuntersAnni Byard, a British antiquities official, said in a report:

"The location of the grave is of significance, and the items found with her were possibly religious in nature. She was definitely somebody of importance at that time, but this will take further investigation. We are currently trying to raise grants to examine the soil of the grave, this might be able to tell us something more."The Bronze Age Rollright Stones have much lore and myth surrounding them to this day. RollrightStones.co.uk is a website devoted just to the stone circle that gives the legend of the king and his entourage. The site says many stone circles in the British Isles were supposedly revelers petrified by God or the devil for dancing and fiddling or picking turnips on the Sabbath. The Rollright Stones legend is different.

There lived a king who aspired to rule England. He got as far as the Rollright Stones when he encountered a witch, possibly Mother Shipton of Shipton-under-Wychwood, who lived from 1488 to 1551 AD. (Mother Shipton is another story, but suffice to say she is England's most famous prophetess who in childhood was a strange girl raised in a cave and who went on to become an accomplished herbalist and seeress who foretold many calamities of English history.)

The King's Men stone circle at Rollright Stones (Photo by Midnightblueowl/

Wikimedia Commons

)According to the legend reported by Rollrightstones.co.uk, the witch challenged the king:

The King's Men stone circle at Rollright Stones (Photo by Midnightblueowl/

Wikimedia Commons

)According to the legend reported by Rollrightstones.co.uk, the witch challenged the king:“Seven long strides shalt thou take And if Long Compton thou canst see, King of England thou shalt be.”

The king continued on toward Long Compton, which is not far from the Rollright Stones, and as he strode along he shouted:

“Stick, stock, stone as King of England I shall be known.”

The King Stone at Rollright Stones in Warwickshire, England (Poliphilo/

Wikimedia Commons

)When he hit his seventh stride, the ground rose up before him in the form of what is now sometimes called the Arch-Druid’s barrow. The witch said:

The King Stone at Rollright Stones in Warwickshire, England (Poliphilo/

Wikimedia Commons

)When he hit his seventh stride, the ground rose up before him in the form of what is now sometimes called the Arch-Druid’s barrow. The witch said:“As Long Compton thou canst not see King of England thou shalt not be. Rise up stick and stand still stone for King of England thou shalt be none; Thou and thy men hoar stones shall be And I myself an eldern tree.”Then legend says she turned him into the King Stone, his men into the King's Men Stone Circle and his knights into the Whispering Knights.

Henge of the WorldIs treasure hoard found in Germany linked to Nibelung legend?Two thousand year old Mercury figurine found in Yorkshire

The Whispering Knights, a Neolithic dolmen at the Rollright Stones in the Cotswolds, England (Midnightblueowl/

Wikimedia Commons

)Rollrightstones.co.uk says it is unknown what the king did to incur the witch's wrath or why she turned herself into a witch-elder tree, which is said to still grow in a nearby hedge.

The Whispering Knights, a Neolithic dolmen at the Rollright Stones in the Cotswolds, England (Midnightblueowl/

Wikimedia Commons

)Rollrightstones.co.uk says it is unknown what the king did to incur the witch's wrath or why she turned herself into a witch-elder tree, which is said to still grow in a nearby hedge.The site says folk tales tell of caves under the King Stone and King's Men that are the haunt of fairies or the little folk who dance around the stones at midnight. When people go into the caves, tales say, they report being in the fairy realm for years but only a few hours have passed outside. Similar tales are told of other stone circles and megalithic monuments in the British Isles.

Rita's remains and her grave goods were shipped to the British Museum in London for further study.

Featured Image: The skeleton of the Rollright Stone “witch” (News Team International photo)

By Mark Miller

Published on August 10, 2015 07:34

Ancient Ceremonial Site 10 Times Bigger than Stonehenge Hits the Archaeological Spotlight

Ancient Origins

Ancient OriginsUntil recently, Marden Henge was a little known archaeological site, barely visible from the ground and from above. However, recent excavations have thrown this historically important area into the spotlight and archaeologists are now calling it one of the most significant sites in Britain. Researchers are trying to unravel just what prompted the enormous outpouring of time and wealth that went into the creation of Britain’s largest henge.

Marden Henge is a late Neolithic site dating back some 4,500 years, which is located halfway between the World Heritage sites of Stonehenge and Avebury. It consists of giant earthworks that once stood ten feet high and encircled nearly 40 acres of land – ten times the size of Stonehenge.

Lying just a few miles south of Stonehenge, researchers have even suggested that the inhabitants of Marden Henge may have helped to haul the giant stones that make up Stonehenge’s world famous stone circle.

Last month, the University of Reading, in partnership with Historic England, began a three-year excavation of the ancient henge, and they have already made some stunning discoveries.

Researchers unearthed the remnants of a 4,400 year old house at the site, which is thought to be one of the oldest homes discovered in the country, as well as the remains of at least 13 pigs, flint blades, decorated pottery with food residue still preserved within them, copper bracelets, and the remains of a 4,000 year old adolescent who was buried in the fetal position with an amber necklace.

National Geographic reports that they have also now found a stone building that once contained a frequently used fire pit that reached very high temperatures. Researchers have speculated that the it may have served as a place for feasts on a grand scale, where pigs were roasted over a spit. Other interpretations are that the building served as a sweat lodge for special ceremonies, or even the place where people of the Neolithic made first efforts to smelt metal.

Body of 4,000-year-old teenager near Stonehenge may give clues about Bronze Age lives 4,400-year-old ruins found near ceremonial site may be the oldest house ever found in Britain Henge of the World

Jim Leary, lead archaeologist, with the remnants of the walls and the floor of the ancient home at Marden Henge. (University of Reading)

Jim Leary, lead archaeologist, with the remnants of the walls and the floor of the ancient home at Marden Henge. (University of Reading) The teenager's skull after excavation; scientists hope to determine a lot about the person buried, such as diet, place of habitation, any diseases and cause and year of death. (

Daily Mail

)According to the new report in the National Geographic, archaeologists are now looking for clues into what prompted the enormous building boom in Stone Age Britain, which included the construction of Marden Henge, Stonehenge, Avebury, and other great monuments.

The teenager's skull after excavation; scientists hope to determine a lot about the person buried, such as diet, place of habitation, any diseases and cause and year of death. (

Daily Mail

)According to the new report in the National Geographic, archaeologists are now looking for clues into what prompted the enormous building boom in Stone Age Britain, which included the construction of Marden Henge, Stonehenge, Avebury, and other great monuments.“It was insane, utterly unsustainable,” Jim Leary, director of the archaeology field school at the University of Reading, told National Geographic. “We tend to think of people during the Neolithic as somehow being at one with their environment, but they appear to have been just as bad as we are. They were clearing, felling, digging, and consuming their environment at an unsustainable rate in building these huge projects.”

Leary maintains that Marden Henge was too big for any practical purpose, and religious fervor may have played a role, or it may have been to show off power and wealth.

“Certainly something big was going on in this part of Britain during the late Neolithic to have prompted the rash of monument building and outpouring of wealth,” reports National Geographic.

Excavations being carried out near Marden Henge. (Sarah Lambert-Gates/University of Reading) The excavations at Marden Henge constitute the first serious research at the site since the 1960s. It is hoped that the three year project may provide new insights into the mysterious Neolithic culture that once inhabited the historically rich region around Stonehenge.

Excavations being carried out near Marden Henge. (Sarah Lambert-Gates/University of Reading) The excavations at Marden Henge constitute the first serious research at the site since the 1960s. It is hoped that the three year project may provide new insights into the mysterious Neolithic culture that once inhabited the historically rich region around Stonehenge.Featured image: The site of Marden Henge in Wiltshire ( Snip View )

By April Holloway

Published on August 10, 2015 07:25

The Diane Turner Show for 9-8-15

Published on August 10, 2015 07:17

History Trivia - Battle of Maldon - Vikings victorious

August 10

955 Battle of Lechfeld: Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor defeated the Magyars (Hungarians), ending 50 years of Magyar invasion of the West.

991 Battle of Maldon: the English, led by Byrhtnoth, Ealdorman of Essex, were defeated by a band of inland-raiding Vikings near Maldon in Essex.

1316 The Second Battle of Athenry during the Bruce campaign in Ireland. The Second Battle of Athenry marked the definitive end of the power of the Ua Conchobair (O'Connor's) as Kings of Connacht. The decades following marked the high point of Norman rule in Connacht, and the rise of the towns of Athenry and Galway as centers of economic and political power and wealth. Unlike the First Battle of Athenry in 1249, no account is given of the battle itself in any surviving account, and even the site of the battle itself is uncertain.

955 Battle of Lechfeld: Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor defeated the Magyars (Hungarians), ending 50 years of Magyar invasion of the West.

991 Battle of Maldon: the English, led by Byrhtnoth, Ealdorman of Essex, were defeated by a band of inland-raiding Vikings near Maldon in Essex.

1316 The Second Battle of Athenry during the Bruce campaign in Ireland. The Second Battle of Athenry marked the definitive end of the power of the Ua Conchobair (O'Connor's) as Kings of Connacht. The decades following marked the high point of Norman rule in Connacht, and the rise of the towns of Athenry and Galway as centers of economic and political power and wealth. Unlike the First Battle of Athenry in 1249, no account is given of the battle itself in any surviving account, and even the site of the battle itself is uncertain.

Published on August 10, 2015 01:30

August 9, 2015

Mr. Chuckles talks shop with Canadian author Eden Baylee while stirring the Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard says:

Eden Baylee is a name many fans Stateside and beyond will be familiar with. A Canadian (one of the first to appear around the Cauldron, if not the first), Eden creates full time and took the brave decision to leave a promising career in finance to pursue a career as an author following a serious illness that caused a panoply of life-is-too-short reflections.

She is an absolute delight to talk to - upbeat, positive, witty and fun, and for a music beast like your second favourite Wizard, meeting someone as passionate about music as I am was always going to something to savour.

I've read two of her pieces and there is no doubt she can write - crisp, clean, linear, unfussy prose that airport thriller readers and fans of, er, the saucy side of the industry would devour in a couple of sittings. She's a natural for the spinner racks.

Throw a stick in any direction somewhere in Toronto and you'll hit a cool coffee shop full of artists and the bijou...and that's where I found Eden. Here's what she had to say.

Read the entire interview here

Published on August 09, 2015 05:52