MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 154

August 25, 2015

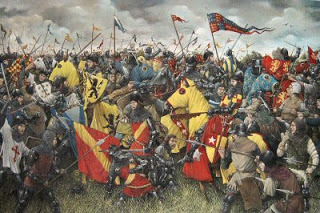

History Trivia - Battle of Crecy - English victorious

August 25

357 Julian Caesar defeated the Alamanni (alliance of German tribes) at Strousbourg in Gaul.

1346 Edward III of England defeated Philip VI's army at the Battle of Crecy in France.

1549 Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI. The rebellion was in response to the enclosure of land. It began in July 1549 but was eventually crushed by forces loyal to the English crown when the Earl of Warwick attacked and entered Norwich on August 25.

357 Julian Caesar defeated the Alamanni (alliance of German tribes) at Strousbourg in Gaul.

1346 Edward III of England defeated Philip VI's army at the Battle of Crecy in France.

1549 Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI. The rebellion was in response to the enclosure of land. It began in July 1549 but was eventually crushed by forces loyal to the English crown when the Earl of Warwick attacked and entered Norwich on August 25.

Published on August 25, 2015 01:30

August 24, 2015

United States Navy Band - Selections from Jersey Boys

Published on August 24, 2015 05:56

The Diane Turner Show on More Music Radio - 23-08-15

Published on August 24, 2015 05:41

9 weird medieval medicines

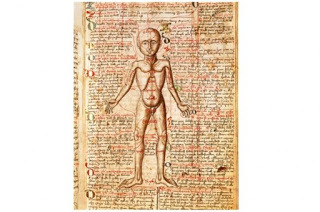

Anatomical chart of the human body, from 15th-century Tractatabus de Pestilentia (Treatise on Plague) © The Art Archive / Alamy

History Extra

Just as we do today, people in the medieval period worried about their health and what they might do to ward off sickness, or alleviate symptoms if they did fall ill. Here, historian Toni Mount reveals some of the most unusual remedies commonly used…

Medicines in the medieval period were sometimes homemade, if they weren’t too complicated. Simple medicines consisted of a single ingredient – usually a herb – but if they required numerous ingredients or preparation in advance, they could be purchased from an apothecary, rather like a modern pharmacist.

Although some medical remedies were quite sensible, others were extraordinarily weird. They all now come with a health warning, so it’s probably best not to try these at home...

1) St Paul’s Potion for epilepsy, catalepsy and stomach problemsSupposedly invented by St Paul, this potion was to be drunk. The extensive list of ingredients included liquorice, sage, willow, roses, fennel, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, cormorant blood, mandrake, dragon’s blood and three kinds of pepper.

Although this sounds like a real witch’s brew, most of the ingredients do have some medicinal value: liquorice is good for the chest – it was and continues to be used to treat coughs and bronchitis; sage is thought to improve blood flow to the brain and help one’s memory, and willow contains salicylic acid, a component of aspirin. Fennel, cinnamon and ginger are all carminatives (which relieve gas in the intestines), and would relieve a colicky stomach.

Cormorant blood – or that of any other warm-blooded creature – would add iron for anaemia; mandrake, although poisonous, is a good sleeping draught if used in small doses, and, finally, dragon’s blood. This isn’t blood at all, and certainly not from a mythical beast! It is the bright red resin of the tree Dracaena draco – a species native to Morocco, Cape Verde and the Canary Islands. Modern research has shown that it has antiseptic, antibiotic, anti-viral and wound-healing properties, and it is still used in some parts of the world to treat dysentery – but I’m not sure it could have done anything for epileptics or cataleptics.

2) A good medicine for sciatica [pain caused by irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve, which runs from the back of your pelvis, all the way down both legs]A number of medieval remedies suggested variations of the following: “Take a spoonful of the gall of a red ox and two spoonfuls of water-pepper and four of the patient’s urine, and as much cumin as half a French nut and as much suet as a small nut and break and bruise your cumin.

Then boil these together till they be like gruel then let him lay his haunch bone [hip] against the fire as hot as he may bear it and anoint him with the same ointment for a quarter of an hour or half a quarter, and then clap on a hot cloth folded five or six times and at night lay a hot sheet folded many times to the spot and let him lie still two or three days and he shall not feel pain but be well.”

Perhaps it was the bed rest and heat treatments that did the trick, because I can’t see the ingredients of the ointment doing much good otherwise!

3) For burns and scalds“Take a live snail and rub its slime against the burn and it will heal”

A nice, simple DIY remedy – and yes, it would help reduce blistering and ease the pain! Recent research has shown that snail slime contains antioxidants, antiseptic, anaesthetic, anti-irritant, anti-inflammatory, antibiotic and antiviral properties, as well as collagen and elastin, vital for skin repair.

Modern science now utilises snail slime, under the heading ‘Snail Gel’, as skin preparations and for treating minor injuries, such as cuts, burns and scalds. It seems that medieval medicine got this one right.

4) For a stye on the eye“Take equal amounts of onion/leek [there is still debate about whether ‘cropleek’, as stated in the original recipe, in Bald’s Leechbook, is equivalent to an onion or leek today] and garlic, and pound them well together. Take equal amounts of wine and bull’s gall and mix them with the onion and garlic. Put the mixture in a brass bowl and let it stand for nine nights, then strain it through a cloth. Then, about night-time, apply it to the eye with a feather.”

Would this Anglo-Saxon recipe have done any good? The onion, garlic and bull’s gall all have antibiotic properties that would have helped a stye – an infection at the root of an eyelash.

The wine contains acetic acid which, over the nine days, would react with the copper in the brass bowl to form copper salts, which are bactericidal. Recently, students at Nottingham University made up and tested this remedy: at first, the mixture made the lab smell like a cook shop, with garlic, onions and wine, but over the nine days the mixture developed into a stinking, gloopy goo. Despite its unpromising odour and appearance, the students tested it for any antibiotic properties and discovered that it is excellent. The recipe is now being further investigated as a treatment against the antibiotic-resistant MRSA bug, and it looks hopeful.

The ancient apothecary was right about this remedy, but it was one that needed to be prepared in advance for sale over the counter.

The apothecary's shop. From Johannis de Cuba Ortus Sanitatis, Strasbourg, 1483. © Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy

5) For gout“Take an owl and pluck it clean and open it, clean and salt it. Put it in a new pot and cover it with a stone and put it in an oven and let it stand till it be burnt. And then stamp [pound] it with boar’s grease and anoint the gout therewith.”

Poor owl! I can’t think that this would have helped the patient very much either…

6) For migraines“Take half a dish of barley, one handful each of betony, vervain and other herbs that are good for the head; and when they be well boiled together, take them up and wrap them in a cloth and lay them to the sick head and it shall be whole. I proved.”

Betony [a grassland herb] was used by the medieval and Tudor apothecary as an ingredient in remedies to be taken internally for all kinds of ailments, as well as in poultices for external use, as in this case. Modern medicine still makes use of the alkaloid drugs found in betony for treating severe headaches and migraine.

Vervain’s glycoside [a class of molecules in which, a sugar molecule is bonded to a ‘non-sugar’ molecule] derivatives too are used in modern treatments for migraine, depression and anxiety, so once again the apothecary knew what he was doing with this recipe!

7) For him that has quinsy [a severe throat infection]“Take a fat cat and flay it well, clean and draw out the guts. Take the grease of a hedgehog and the fat of a bear and resins and fenugreek and sage and gum of honeysuckle and virgin wax. All this crumble small and stuff the cat within as you would a goose. Roast it all and gather the grease and anoint him [the patient] with it.”

With treatments like this, is it any wonder that a friend wrote to Pope Clement VI when he was sick, c1350, to say: “I know that your bedside is besieged by doctors and naturally this fills me with fear… they learn their art at our cost and even our death brings them experience.”

8) To treat a cough“Take the juice of horehound to be mixed with diapenidion and eaten”

Horehound [a herb plant and member of the mint family] is good for treating coughs, and diapenidion is a confection made of barley water, sugar and whites of eggs, drawn out into threads – so perhaps a cross between candy floss and sugar strands. It would have tasted nice, and sugar is good for the chest – still available in an over-the-counter cough mixture as linctus simplex.

9) For the stomach“To void wind that is the cause of colic, take cumin and anise, of each equally much, and lay it in white wine to steep, and cover it over with wine and let it stand still so three days and three nights. And then let it be taken out and laid upon an ash board for to dry nine days and be turned about. And at the nine days’ end, take and put it in an earthen pot and dry over the fire and then make powder thereof. And then eat it in pottage or drink it and it shall void the wind that is the cause of colic”

Both anise and cumin are carminatives, so this medicine would do exactly what it said on the tin – or earthen pot. The herbs dill and fennel could be used instead to the same effect – 20th-century gripe water for colicky babies contained dill.

This remedy would have taken almost two weeks to make, so patients would have bought it from the apothecary, as needed.

Toni Mount is an author, historian and history teacher. She began her career working in the laboratories of the then-Wellcome pharmaceutical company [now GlaxoSmithKline], and gained her MA studying a 15th-century medical text at the Wellcome Library. She is also a member of the Research Committee of the Richard III Society.

Published on August 24, 2015 05:31

History Trivia - Mount Vesuvius erupts burying the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum

August 24

49 BC Julius Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio was defeated in the Second Battle of the Bagradas River by the Numidians under Publius Attius Varus and King Juba of Numidia. Curio committed suicide to avoid capture.

79 Mount Vesuvius erupted. The cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae were buried in volcanic ash Pliny the Elder died of asphyxiation at age 56 while witnessing the scene from the coast.

410 Alaric, leader of the Visigoths, sacked Rome, but spared its churches. This was first hostile occupation of the city since the fourth century BC.

49 BC Julius Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio was defeated in the Second Battle of the Bagradas River by the Numidians under Publius Attius Varus and King Juba of Numidia. Curio committed suicide to avoid capture.

79 Mount Vesuvius erupted. The cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae were buried in volcanic ash Pliny the Elder died of asphyxiation at age 56 while witnessing the scene from the coast.

410 Alaric, leader of the Visigoths, sacked Rome, but spared its churches. This was first hostile occupation of the city since the fourth century BC.

Published on August 24, 2015 01:00

August 23, 2015

Mr. Chuckles bumped into Sheffield author E.L.Lindley when stirring The Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard speaks:

One of my favourite people in Indie is back today - Sheffield's finest E.Lindley. E is well known on the circuit for the long running Georgie Connelly series, which combine the thriller genre with character and comedy. E is also developing a reputation for punchy, angry, claustrophobic short stories about real life (some drawing on her experience as a teacher), on her blog -stories I highly recommend.

Her novels have a real BBC quality, dramatic and talky, more like plays than novels in parts, and I thoroughly enjoy mentally casting her characters, because, as you will see today, E's serious passion is cinema - if you ever need to know what a new film is like, drop E a line, because it is odds-on that she's already seen it.

I caught up with E on the Wizphone - naturally, she was off to the flicks! Here's what she had to say.

You can find and read E's first visit to the Cauldron here, on the Wizard's Cauldron Index

http://wizardscauldronindex.blogspot.co.uk/

Read the entire interview

Published on August 23, 2015 05:35

History Trivia - Mount Vesuvius begins to stir

August 23

79 Mount Vesuvius ( a stratovolcano on the Bay of Naples, Italy) began to stir, on the feast day of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire.

406 Battle at Florence: Stilicho's Roman army beat Radagaisus' Barbarians. Radagaisus King of the Goths (East Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin) was captured and executed.

686 Charles Martel, grandfather of Charlemagne, was born.

79 Mount Vesuvius ( a stratovolcano on the Bay of Naples, Italy) began to stir, on the feast day of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire.

406 Battle at Florence: Stilicho's Roman army beat Radagaisus' Barbarians. Radagaisus King of the Goths (East Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin) was captured and executed.

686 Charles Martel, grandfather of Charlemagne, was born.

Published on August 23, 2015 01:30

August 22, 2015

In case you missed it... Treachery: what really brought down Richard III

History Extra

David Hipshon, whose book on the controversial Yorkist monarch is out now, has a new perspective on the reason for Richard’s death at the battle of Bosworth in 1485

On 22 August 1485, in marshy fields near the village of Sutton Cheney in Leicestershire, Richard III led the last charge of knights in English history. A circlet of gold around his helmet, his banners flying, he threw his destiny into the hands of the god of battles.

Among the astonished observers of this glittering panoply of horses and steel galloping towards them were Sir William Stanley and his brother Thomas, whose forces had hitherto taken no part in the action. Both watched intently as Richard swept across their front and headed towards Henry Tudor, bent only on eliminating his rival.

As the king battled his way through Henry’s bodyguard, killing his standard bearer with his own hand and coming within feet of Tudor himself, William Stanley made his move. Throwing his forces at the King’s back he betrayed him and had him hacked him down. Richard, fighting manfully and crying, “Treason! Treason!”, was butchered in the bloodstained mud of Bosworth Field by a man who was, ostensibly at least, there to support him.

Historians have been tempted to see Stanley’s treachery as merely the last act in the short and brutal drama that encompassed the reign of the most controversial king in English history. Most agree that Richard had murdered his two nephews in the Tower of London and that this heinous crime so shocked the realm, even in those medieval days, that his demise was all but assured. The reason he lost the battle of Bosworth, they say, was because he had sacrificed support through this illegal coup.

But hidden among the manuscripts in the duchy of Lancaster records in the National Archives, lies a story that provides an insight into the real reason why Thomas, Lord Stanley, and his brother William betrayed Richard at Bosworth during the Wars of the Roses. The records reveal that for more than 20 years before the battle, a struggle for power in the hills of Lancashire had lit a fuse which exploded at Bosworth.

Land grab

The Stanleys had spent most of the 15th century building up a powerful concentration of estates in west Lancashire, Cheshire and north Wales. As their power grew they came into conflict with gentry families in east Lancashire who resented their acquisitive and relentless encroachments into their lands.

One such family were the Harringtons of Hornby. Unlike their Stanley rivals the Harringtons sided with the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses and remained staunchly loyal. Unfortunately, at the battle of Wakefield in 1460, disaster struck. The Duke of York was killed and with him Thomas Harrington and his son John.

The Stanleys managed, as ever, to miss the battle. They were very keen, however, to pick up the pieces of the Harrington inheritance and take their seat at Hornby, a magnificent castle that dominated the valley of the River Lune in Stanley country.

When John Harrington had been killed at Wakefield the only heirs he left behind were two small girls. They had the legal right to inherit the castle at Hornby, but this would pass to whomever they married. Stanley immediately sought to take them as his wards and to marry them as soon as possible to his only son and a nephew.

John Harrington’s brother James was equally determined to stop him. James argued that his brother had died before their father at Wakefield and so he himself, as the oldest surviving son, had become the heir, not John’s daughters. To make good his claim he took possession of the girls, and fortified Hornby against the Stanleys.

Unfortunately for Harrington, King Edward IV – striving to bring order to a country devastated by civil strife – simply could not afford to lose the support of a powerful regional magnate, and awarded the castle to Stanley.

However, this was by no means the end of the matter. James Harrington refused to budge and held on to Hornby, and his nieces, regardless. What’s more, the records show that friction between the two families escalated to alarming proportions during the 1460s.

In the archive of the letters patent and warrants, issued under the duchy of Lancaster seal, we can see the King struggling – and failing – to maintain order in the region. While James Harrington fortified his castle and dug his heels in, Stanley refused to allow his brother, Robert Harrington, to exercise the hereditary offices of bailiff in Blackburn and Amounderness, which he had acquired by marriage. Stanley falsely indicted the Harringtons, packed the juries and attempted to imprison them.

Revolt and rebellion

This virtual state of war became a real conflict in 1469, when, in a monumental fit of pique, the Earl of Warwick – the most powerful magnate in the land, with massive estates in Yorkshire, Wales and the Midlands – rebelled against his cousin Edward IV.

The revolt saw the former king, the hapless Henry VI, being dragged out of the Tower and put back on the throne. Stanley, who had married Warwick’s sister, Eleanor Neville, stood to gain by joining the rebellion.

There were now two kings in England – and Edward was facing a bitter battle to regain control. In an attempt to secure the northwest, he placed his hopes on his younger brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III.

This had immediate consequences for Stanley and Harrington, for Richard displaced the former as forester of Amounderness, Blackburn and Bowland, and appointed the latter as his deputy steward in the forest of Bowland, an extensive region to the south of Hornby. Even worse, from Stanley’s point of view, the castle of Hornby was in Amounderness, where Richard now had important legal rights.

During the rebellion Stanley tried to dislodge James once and for all by bringing a massive cannon called ‘Mile Ende’ from Bristol to blast the fortifications. The only clue we have as to why this failed is a warrant issued by Richard, dated 26 March 1470, and signed “at Hornby”.

It would appear that the 17-year-old Richard had taken sides and was helping James Harrington in his struggle against Stanley. This is hardly surprising as James’s father and brother had died with Richard’s father at Wakefield and the Harringtons were actively helping Edward get his throne back. In short, it seems that the Harringtons had a royal ally in Richard, who could challenge the hegemony of the Stanleys and help them resist his ambitions.

The Harringtons’ support for Edward was to prove of little immediate benefit when the King finally won his throne back after defeating and killing Warwick at the battle of Barnet and executing Henry VI.

Grateful he may have been, but the harsh realities of the situation forced Edward to appease the Stanleys because they could command more men than the Harringtons and, in a settlement of 1473, James Harrington was forced to surrender Hornby.

Richard ensured that he received the compensation of the nearby property of Farleton, and also land in west Yorkshire, but by the time Edward died in 1483 Stanley had still not handed over the lucrative and extensive rights that Robert Harrington claimed in Blackburn and Amounderness.

A family affair

One thing, however, had changed. The leading gentry families in the region had found a ‘good lord’ in Richard. He had been made chief steward of the duchy in the north in place of Warwick and used his power of appointment to foster members of the gentry and to check the power of Stanley.

Only royal power could do this and Richard, as trusted brother of the King, used it freely. The Dacres, Huddlestons, Pilkingtons, Ratcliffes and Parrs, all related by marriage to the Harringtons, had received offices in the region and saw Richard, not Stanley, as their lord.

When Richard took the throne he finally had the power to do something for James Harrington. The evidence shows that he planned to reopen the question of the Hornby inheritance.

This alone would have been anathema to Stanley but it was accompanied by an alarming series of appointments in the duchy of Lancaster. John Huddleston, a kinsman of the Harringtons, was made sheriff of Cumberland, steward of Penrith and warden of the west march. John Pilkington, brother-in-law of Robert Harrington, was steward of Rochdale and became Richard III’s chamberlain; Richard Ratcliffe, Robert Harrington’s wife’s uncle, was the King’s deputy in the west march and became sheriff of Westmorland. Stanley felt squeezed, his power threatened and his influence diminished.

With Richard at Bosworth were a close-knit group of gentry who served in the royal household: men like John Huddleston, Thomas Pilkington and Richard Ratcliffe. They were men whom Richard could trust, but they were also the very men who were instrumental in reducing Stanley’s power in the northwest.

By Richard’s side, possibly carrying his standard, was James Harrington. When Richard III sped past the Stanleys at Bosworth Field he presented them with an opportunity too tempting to refuse.

During the 1470s Richard had become the dominant power in the north as Edward’s lieutenant. He served his brother faithfully and built up a strong and stable following. The leading gentry families could serve royal authority without an intermediary. The losers in this new dispensation were the two northern magnates, Henry Percy and Thomas Stanley.

Richard challenged their power and at Bosworth they got their revenge. When Richard rode into battle, with Harrington by his side, loyalty, fidelity and trust rode with him. Like the golden crown on Richard’s head they came crashing down to earth.

Published on August 22, 2015 06:44

History Trivia - Richard III killed at the Battle of Bosworth

August 22

476 Odoacer was named Rex Italia (King of Italy) by his troops. His reign is commonly seen as marking the end of the classical Roman Empire in Western Europe and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

565 St. Columba reported seeing a monster in Loch Ness, Scotland.

1485 Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth and Henry VII became the first king of the Tudor dynasty.

476 Odoacer was named Rex Italia (King of Italy) by his troops. His reign is commonly seen as marking the end of the classical Roman Empire in Western Europe and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

565 St. Columba reported seeing a monster in Loch Ness, Scotland.

1485 Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth and Henry VII became the first king of the Tudor dynasty.

Published on August 22, 2015 01:30

August 21, 2015

History Trivia - Dundee's rising in Scotland

August 21

1165 Philip II (Philip Augustus) the first king of the Capetian dynasty in France was born.

1689 The Battle of Dunkeld in Scotland was fought between Jacobite clans supporting the deposed king James VII of Scotland and a government regiment of covenanters supporting William of Orange, King of Scotland, in the streets around Dunkeld Cathedral, Dunkeld, Scotland, and formed part of the Jacobite rising commonly called Dundee's rising in Scotland.

1165 Philip II (Philip Augustus) the first king of the Capetian dynasty in France was born.

1689 The Battle of Dunkeld in Scotland was fought between Jacobite clans supporting the deposed king James VII of Scotland and a government regiment of covenanters supporting William of Orange, King of Scotland, in the streets around Dunkeld Cathedral, Dunkeld, Scotland, and formed part of the Jacobite rising commonly called Dundee's rising in Scotland.

Published on August 21, 2015 01:30