MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 156

August 15, 2015

History Trivia - Sistine Chapel consecrated

August 15

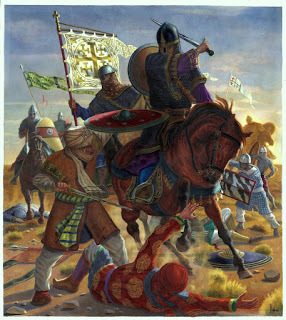

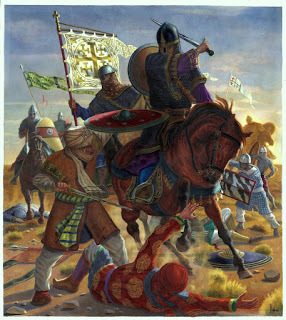

778 The Battle of Roncevaux Pass (Pyrenees on the border between France and Spain), at which Roland (commander of the rear guard of Charlemagne's army) was killed. The battle was romanticized by oral tradition into a major conflict between Christians and Muslims, when in fact both sides in the battle were Christian. The legend is recounted in the 11th century The Song of Roland, which is the oldest surviving major work of French literature, and in Orlando Furioso, which is one of the most celebrated works of Italian literature.

1309 – The city of Rhodes surrendered to the forces of the Knights of St. John, completing their conquest of Rhodes. The knights established their headquarters on the island and renamed themselves the Knights of Rhodes.

1483 Pope Sixtus IV consecrated the Sistine Chapel.

778 The Battle of Roncevaux Pass (Pyrenees on the border between France and Spain), at which Roland (commander of the rear guard of Charlemagne's army) was killed. The battle was romanticized by oral tradition into a major conflict between Christians and Muslims, when in fact both sides in the battle were Christian. The legend is recounted in the 11th century The Song of Roland, which is the oldest surviving major work of French literature, and in Orlando Furioso, which is one of the most celebrated works of Italian literature.

1309 – The city of Rhodes surrendered to the forces of the Knights of St. John, completing their conquest of Rhodes. The knights established their headquarters on the island and renamed themselves the Knights of Rhodes.

1483 Pope Sixtus IV consecrated the Sistine Chapel.

Published on August 15, 2015 01:00

August 14, 2015

The Roman invasion: Whose side were the Britons on?

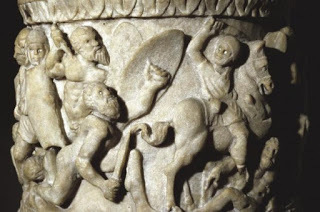

Romans and their enemies clash in a second-century relief sculpture. (Credit: AAA Collection)

History Extra

The Roman invasion of Britain is an old, old story. However, the reconstruction and display of the Hallaton helmet – a ceremonial Roman helmet found in an Iron Age shrine – in 2012 reminds us that relations between the invaders and the Britons were more complex than we normally imagine. Did Britons really, as the helmet’s discovery implies, fight side by side with the Romans against their own people? Why might they have swapped their loyalties? And, even with local support, was it really an easy ride for the Romans?

By combining the latest archaeological discoveries – such as the Hallaton helmet – with reports written by ancient historians, we can piece together the events and motives of the time. From these, startling questions arise: were the Britons more prepared than the Romans who first marched into this unexplored world? And what opportunities for personal advancement did some Britons seize, while others continued to put up such a determined resistance that, in 400 years of Roman occupation, Britain never truly lost its identity as a military frontier province? Just what was the real story?

The Hallaton helmet was discovered in 2000 near Hallaton, Leicestershire. It was possibly made between AD 25 and 50, making it one of the earliest Roman helmets ever found in Britain. (Credit: Rex)

Why did Caesar only come, look and leave again?Rome first invaded Britain back in 55 BC. Julius Caesar had just spent three years conquering Gaul, but he knew that Britons were supporting the Gallic resistance there. A punitive attack to put the interfering Britons in their place was due. He intended not only to prove Rome’s might, but to return laden with booty and with military and political glory for himself – for the invasion and the conquest of a new, untamed land was an accepted traditional route to political success.

So he led two legions across the channel and arrived on the south coast of Britain in August 55 BC. However, the tidal waters at Deal made it impossible to beach his ships and his army was forced to wade ashore in full armour, leaving them in no state to meet the local warriors who were waiting for them. The Romans survived but victory eluded both sides because the Britons used guerrilla tactics and avoided a pitched battle of the kind that the Roman army was accustomed to.

When the weather worsened and the Roman fleet was virtually destroyed in a storm, Caesar retreated and limped homehaving underestimated the resistance he would meet. He returned the following year, 54 BC, for a face-saving expedition, this time with more soldiers and the addition of cavalry to counter the Britons’ devastating, whirling war chariots. Shocked, the Britons buried their differences and united together under Cassivellaunus, the king of the Catuvellauni tribe. Tribal enmities proved too ingrained though and Cassivellaunus was betrayed: Caesar extracted tribute and eventually returned triumphant to Rome, but he never came back to Britain.

What led Claudius to invade?It was nearly 100 years before Rome invaded Britain again. After Caesar’s expedition, the geographer Strabo had written, rather defensively perhaps, that “although the Romans could have held Britain, they scorned to do so, because they saw that there was nothing at all to fear from the Britons (for they are not strong enough to cross over and attack us), and”, he continued, “they saw that there was no corresponding advantage to be gained by seizing and holding their country”.

Nonetheless, the limping, trembling and militarily inexperienced Emperor Claudius knew (like Caesar) that he needed military success to thrive in power, and that a prestigious invasion could provide him with the greatest honour any Roman could hope for: a triumphal procession in Rome and all the glory and popularity that went with it. A victorious invasion of a barbarian land would also serve to boost Roman morale and to distract from troubles at home.

He was well equipped. Three years earlier, Emperor Caligula had drafted legions specially to invade Britain but had never used them. They were idle and dangerously restless, so, when a request for help came from Verica of the Atrebates tribe (who had been ousted from power by Caratacus, king of the Catuvellauni tribe), Claudius was ready.

Celtic coins like this one aped the style of their Roman counterpart. (Credit: Scran)

How did the invasion commence in AD 43?The emperor gave command of the invasion to the general Aulus Plautius, who led legions, cavalry and auxiliary troops across to Britain. They arrived unopposed in three groups – though it is not clear where they landed: Richborough and the Solent have been suggested – defeated Catuvellaunian attacks and reached a river, perhaps the Medway or the Thames. The Britons were carelessly encamped on the west side, thinking the Roman army couldn’t cross the fast, wide river without a bridge, but the Romans had recruited Celts who were practiced at swimming in full armour. These auxiliary troops crossed to the enemy camp and maimed the horses that drew the formidable battle chariots. The Roman advance towards London continued and the Catuvellaunian king Caratacus fled to Wales (where he instigated opposition to Rome for years).

No other tribe could come close to the military strength of the Catuvellauni and, one by one, they surrendered to Rome. Aulus Plautius now sent a message to Claudius, inviting him to come to Britain and to personally make a triumphal entry into Colchester. Some weeks later, Claudius arrived, together with war elephants. This wasn’t just for show, for their smell was known to drive enemy horses mad and the Britons’ skill in chariots was likely to be a real threat, even now. Colchester was taken, and Claudius declared Britain conquered. After just 16 days, he headed home to receive the applause and glory of a triumphal entry into Rome. Plautius was left to consolidate the conquest across the rest of Britain.

How strong was the Roman army?Aulus Plautius commanded perhaps up to 40,000 professional soldiers in Britain. This army’s true strength, though, lay not just in numbers or in the mix of regular legionaries and skilled auxiliaries but in the way the soldiers trained together, spent their adult lives in military service together and, following precise orders, fought in a disciplined and controlled manner. The Britons, on the other hand, were fierce warriors who fought for individual honour, as and when required.

The contrasts were highly visual too: the Romans were heavily armoured (one legionary alone probably wore more iron in his helmet, breastplate and weaponry than most Britons saw in their lifetime) and they advanced as a unified whole, shields protecting neighbours, and with short, stabbing swords that encouraged close teamwork and close combat. The Britons, however – so the Romans tell us – looked more like beasts than men: they howled battle shrieks and cries and fearlessly stripped off for battle, painted themselves with the blue dye of the woad plant, and caked their long wild hair and tousled beards and moustaches with limed water into white spikes. They excelled at ambushes and quick strikes, and fought so skilfully that they could launch spears and wield shields and swords at full gallop, leap on and off the chariots at speed, and even in mid-battle stand on the pole and run up and down from the chariot to the rugged but agile ponies.

The Romans’ speed was more measured: despite the weight of equipment they carried, they were hardened to long and swift marches, after which they would dig ramparts and set up marching camps each night. They would build strategic wooden (and later stone) forts for a more permanent presence – theirs was no hit and run invasion. The message was clear – they were here to stay.

This second-century bronze statuette shows the dress of a typical Roman legionary. (Credit: The British Museum)

Did the Britons know the Romans were coming?The arrival of the Romans was not a surprise to the Britons. Previous contact between them certainly existed: trade had, for decades, brought cultural influences such as coins and amphorae of wine to Britain; some Britons had fought with the Gauls against Rome in Caesar’s Gallic War – the military might and ambitions of Rome were not just recognised but had been experienced; and Caesar tells us some tribes, learning of the invasion from traders, sent envoys to him in Gaul to sue for peace.

Nonetheless, the channel must have provided a buffer, a sense of protection, not just for the Romans, but for the Britons too who were engrossed in their own local tribal disputes. The first Romans may have seemed like just another border challenge.

After Caesar’s failed incursions, the Britons may even have felt rather superior. It was only the arrival of around 40,000 soldiers in AD 43 that prompted them to work together: either they were shocked into it (and therefore not so prepared after all), or perhaps they had already considered and prepared for the undignified possibility of having to join forces against the common enemy.

A Celtic relief of a chariot, which the Britons employed as a formidable weapon. (Credit: National Museum of Archaelogy France)

What did the Romans think Britain would be like?The Romans viewed the Britons as deeply barbaric. Rumours of druidic rites and human sacrifices, and tales of enemies being headhunted were so rife that Claudius’s soldiers refused to set sail across the channel until his freedman, Narcissus, was sent to shame them into action – it took the humiliation of a telling-off by an ex-slave to overcome their fear and to get them moving. Some 15 years later, Roman soldiers would again be rooted to the spot in terror when attacking the druid stronghold of Anglesey: the Romans were definitely leaving their comfort zone and entering an alien land.

Tacitus, the Roman historian, would express their fear when he imagined a Briton chief pronouncing “our very remoteness, in a land known only to rumour, has, until now, protected us”.

It was such rumours of barbarism that inspired the Romans to believe they would be doing these Britons a favour by conquering them, occupying the country and enforcing the civilised ways of Rome on them.

Did the Romans have support from native Britons?The traditional view of the invasion is a straightforward tale of the organised Romans sailing over, marching across the land, and subduing the primitive Britons. The reality appears less clear-cut.

The Britons’ loyalties were divided: a warrior people, they sought status by violently taking other tribes’ lands and their people as slaves, and their inability to abandon the traditional in-fighting of these tribal rivalries weakened them and indirectly helped the Romans.

While the Britons were certainly tough and warlike, they were also opportunistic and capable of changing loyalties as it suited them: the cut-throat inter-tribal conflicts often provided the Romans with allies. Celtic soldiers even served in the Roman army, either to help to defeat a tribal enemy or to get ahead personally – a conscious decision to side with the potential winners and to receive a reward (such as the Hallaton helmet, perhaps?). Indeed, some tribal chiefs openly surrendered to the Romans in order to share the victory and to acquire power and status, for being a puppet chief of the Romans would rake in the material benefits and luxuries of the empire and could be preferable to honourable defeat and slaughter.

Despite this, the Britons were no walkover: their warriors’ skills in chariot warfare and guerrilla tactics were highly effective in reducing the efficiency of the trained Roman units. It was only in the south-east that the Romans really silenced the opposition.

The Roman conquest of Britain was never a foregone conclusion though: even nearly 20 years on, an excessively heavy Roman rule would prompt the rebellion of the Iceni, led by Queen Boudica, whose followers would raze the new Roman towns of London, St Albans and Colchester to the ground in an uprising in which 70,000 people would be killed before the Romans regained control. Further north and in Wales, the Britons continued to resist violently. They were never really settled or Romanised at ground roots level, and the army remained an active presence throughout the occupation.

Because we talk of ‘Roman Britain’ we tend to forget that most of Scotland, despite some Roman incursions, remained unconquered and was never truly won over. And Ireland was never invaded. ‘Roman Britain’ was essentially only Roman England and (less securely) Wales.

When did the invasion finish and the occupation begin?Claudius considered the occupation of Britain to have begun as soon as Colchester fell: the tribes encountered up to that point had capitulated and he ordered inscriptions to be set up around the empire glorifying his defeat of 11 tribal kings.

There was still much work to be done though. An army headed northwards, from Colchester and the Catuvellauni territories into the Midlands, while Vespasian (the future emperor) led an army west, taking 20 Iron Age forts including Maiden Castle. By AD 47, the Romans held England from the river Humber in the north to the estuary of the river Severn in the south-west. It was a remarkable achievement.The concept of a ‘Roman Britain’ can be applied only to urban life. It might be said to have existed once the Britons began to accept and adopt Roman ways; when they considered themselves part of the empire and made Rome work to their personal advantage.

The peaceful and thriving south did truly adopt Roman culture, but the north remained a military zone, and Wales was frequently troublesome. Roman Britain was a land linked by a web of forts and military roads and it is telling that, unlike any other Roman provinces, no Briton who ever went to Rome itself made it big there.

Nonetheless, right from the moment when the first British chiefs yielded, Rome’s eagle had them in her grip. Roman Britain had tentatively begun and, from now on, the everyday life of urban Britons would look increasingly Roman.

Maiden Castle in Dorset, an Iron Age hill fort abandoned after the Roman conquest. (Credit: Alamy)

How much do we really know about this story? The archaeological evidence for the invasion years is sparse, yielding little more than shadows of wooden forts and echoes of violent warfare, such as the artillery bolts that litter Maiden Castle. This is why the Hallaton helmet, ritually buried at a Leicestershire Iron Age shrine within a mere two years of AD 43, is so important. This rich gift from Rome, heavy with ‘victory’ symbols, suggests serious collaboration by the locals.

Of course, it could have been stolen, a trophy of a raid, but archaeology combines with Roman literature (there were no writers in the illiterate British Iron Age) to reveal that some ambitious Britons were quick to seize opportunities for personal advancement. The Greek historian of Rome, Cassius Dio, recorded that Celtic soldiers served in the Roman army, but even before Claudius’s invasion, Strabo reckoned that dues from British trade were richer pickings than any invasion might supply.

Through such trade, Roman culture seeped in. Iron Age coins mimicked Roman coinage (one chief’s coins bore the image of a Roman-style helmet – an interesting symbol when we consider the Hallaton helmet) and archaeologists found fine Roman dining ware even in the royal huts of the northern Brigantian stronghold at Iron Age Stanwick.

Within a few years of the invasion, buildings like Fishbourne Palace and Brading Villa and towns like London and St Albans would appear, but the Romans didn’t have it all their own way. Even as victors they recorded continuing tales of frightened Roman soldiers and terrifying resistance. The Britons were clearly fierce, headstrong and independently minded.

Rome may have declared herself the master of Britain, but many Britons made Rome serve their own purposes. As more details, like the Hallaton helmet, emerge from archaeology, each new clue adds to the complex and fascinating story that is the Roman invasion of Britain.

Gillian Hovell is the author of Roman Britain (Crimson Publishing, 2012). For more information, visit www.muddyarchaeologist.co.uk

Published on August 14, 2015 08:29

Decaying and Looted Pompeii Gets a Big Infusion of Care from the Italian Government

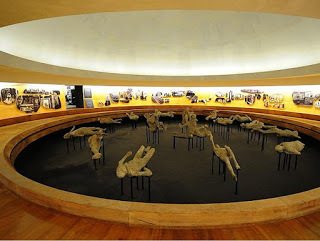

Pompeii, the city frozen in time by a super-hot gas cloud and ash that erupted from Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, has been placed under the protection of the Italian government from degradation by the elements and looters, including possibly the organized-crime group the Camorra. There are numerous restoration and construction projects underway, and the director of the site says it is an exciting time for Pompeii.

Pompeii, the city frozen in time by a super-hot gas cloud and ash that erupted from Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, has been placed under the protection of the Italian government from degradation by the elements and looters, including possibly the organized-crime group the Camorra. There are numerous restoration and construction projects underway, and the director of the site says it is an exciting time for Pompeii.The restorations of the ancient city are being carried out with a 130 million euro ($143 million) budget that is also being spent on putting on exhibit plaster casts of some of the bodies of people frozen in their last moments of life as the gas cloud overwhelmed the city, after which it was buried in ash. The cultural and historical richness of the town cannot be overstated. Many artworks, statues, frescos and papyrus scrolls were preserved by the volcanic eruption that inundated the town, which had 2.7 million visitors in 2014.

The ancient city of Pompeii, Italy. (BigStockPhoto)The United Nations had threatened to remove Pompeii from UNESCO's World Heritage Site status, but that threat appears to have been rescinded as the Italian government, under archeologist Massimo Osanna, who has turned around the project in two years.

The ancient city of Pompeii, Italy. (BigStockPhoto)The United Nations had threatened to remove Pompeii from UNESCO's World Heritage Site status, but that threat appears to have been rescinded as the Italian government, under archeologist Massimo Osanna, who has turned around the project in two years.The Houses of Pleasure in Ancient PompeiiFrozen in Time: Casts of Pompeii Reveal Last Moments of Volcano VictimsGiraffe and Sea Urchin on the Menu for People of PompeiiPompeii fresco depicts hapless Priapus with a painful conditionDegradation included damaged and fading mosaics and frescos on floors and walls of houses, buildings that were decaying and even falling apart and vandalism, said the World Socialist Web Site in 2012. The problems stemmed from over-exploitation for commercial use, bad archaeological methodology and restoration techniques and natural erosion.

“This is a really exciting time for Pompeii,” Osanna told AFP. “Thousands of people are working together. We currently have 35 construction areas on the site. “We have followed UNESCO’s advice to extend projects beyond the initial deadline of 2015. We have the resources and we will carry on working.”

A video of the 2015 restoration of the casts can be seen here:

In ancient times, Pompeii had a population of as many as 20,000 in its 163 acres (65 hectares), most but not all of which have been excavated. Pompeii is just south of Naples on the southeast Italian coast.

The exhibition of plaster casts of 20 victims of Mount Vesuvius' eruption are on display in a wooden pyramid in an ancient amphitheater through September 27, 2015. The people and some animals were carbonized by a gas cloud of 300 degrees C (572 degrees Fahrenheit). The actual bodies, which were ossified by the heat, will not go on display but rather the plaster casts that show the exact position the bodies were found in.

Pompeii was a flourishing Roman city from the 6th century BC until it became frozen in time, preserved by the layers of ash that spewed out from the great eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Although Pompeii was initially rediscovered at the end of the 16th century, it was only properly excavated in the 18th century.

Excavators were startled by the sexually explicit frescoes they were unearthing, quite shocking to the sensibilities of medieval citizens of Rome, so they quickly covered them over.

Raunchy frescoes uncovered in Pompeii. (BigStockPhoto)When excavations resumed nearly two centuries later, archaeologists found the city almost entirely intact – loaves of bread still sat in the oven, bodies of men, women, children and pets were found frozen in their last moments, the expressions of fear still etched on their faces, and the remains of meals remained discarded on the pavement. The astounding discovery meant that researchers could piece together exactly what life was like for the ancient Romans of Pompeii – the food they ate, the jobs they performed and the houses they lived in.

Raunchy frescoes uncovered in Pompeii. (BigStockPhoto)When excavations resumed nearly two centuries later, archaeologists found the city almost entirely intact – loaves of bread still sat in the oven, bodies of men, women, children and pets were found frozen in their last moments, the expressions of fear still etched on their faces, and the remains of meals remained discarded on the pavement. The astounding discovery meant that researchers could piece together exactly what life was like for the ancient Romans of Pompeii – the food they ate, the jobs they performed and the houses they lived in.The recent efforts to restore the city of Pompeii are necessary and will help ensure that the story of the site remains available to future generations.

Featured Image: The bodies of about 20 victims of the volcanic eruption of 79 AD are on display through September 27, 2015, in an ancient amphitheater. (Photo by Mario Laporta of AFP)

By Mark Miller

Ancient Origins

Published on August 14, 2015 08:22

Knitters, Crocheters... we need you! heart emoticon Mainely Hugs, a chapter of the Knitted Knockers

Mainely Hugs is a new chapter of the Knitted Knockers organization that provides knitted and crocheted breast forms to women who have had a mastectomy. These knitted and crocheted breast forms are lightweight & soft. The materials are donated and there is no charge to the women who receive them. As we are only beginning to grow, we are seeking volunteer knitters and crocheters. Additionally we ask for donations of yarn, soft stuffing, double point knitting needles, straight knitting needles & crochet hooks. About 50 yards of yarn is needed to make one (50 gram ball or skein of yarn makes two). Crocheting takes a bit more yarn to keep stitches loose and soft. The breast forms come in all sizes and colors. We use no wool, only soft yarns such as sport or baby yarn. We are mindful of allergies and itching issues caused by some natural fibers. We provide patterns for both knitting and crocheting and have how to videos online to simplify. Crafters will master these patterns quickly. It takes only about 3-4 hours to make each one. If you or someone you know can help, please join us. Our goal is 150+ by end of October. Make just one or one hundred, we appreciate all efforts big and small. We are grateful for any materials or supplies that are donated. We strive to make sure nothing goes to waste. Help us make a difference in the lives of women recovering from breast cancer.

Thank you, Kim Scott

Email: MainelyHugs@gmail.com

Click on this link for more info

Published on August 14, 2015 07:10

History Trivia - Duncan, King of Scots murdered by Macbeth

August 14

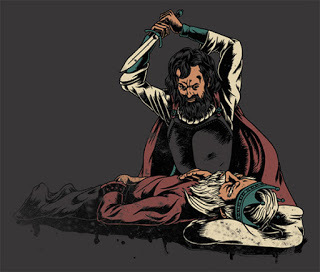

1040 Duncan, King of Scots was murdered by Macbeth, who became king.

1457 The first book ever printed was published by a German astrologer named Faust. He was thrown in jail while trying to sell books in Paris because authorities concluded that all the identical books meant Faust had dealt with the devil.

1040 Duncan, King of Scots was murdered by Macbeth, who became king.

1457 The first book ever printed was published by a German astrologer named Faust. He was thrown in jail while trying to sell books in Paris because authorities concluded that all the identical books meant Faust had dealt with the devil.

Published on August 14, 2015 01:00

August 13, 2015

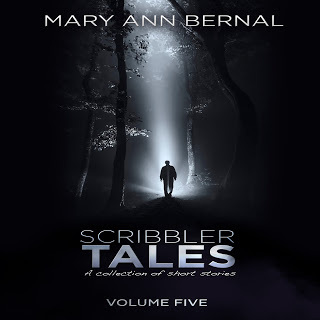

Audio Book Launch - Scribbler Tales, Volume Five now available

Written by: Mary Ann Bernal

Narrated by: Roberto Scarlato

Length: 1 hr and 12 mins

Unabridged Audiobook

Audible Link

In her quest for immortality, Lilly considers a Satanic covenant before the portal closes on All Hallows' Eve in "Bloodlust". When Felicity meets exotic Seth on a flight to Luxor, her fairy-tale vacation is threatened by tomb robbers in "Illusion". "Manhunt" finds Tami and Mick suspecting the newest member of their team while planning one final heist at the Diamond Exchange. Dr. Brenda Lancaster must develop a cure for a mutated pathogen before mankind becomes extinct in "Pandemic".

Published on August 13, 2015 07:50

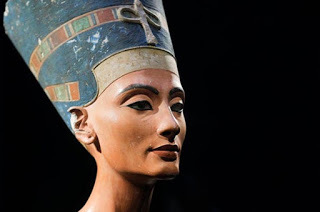

The Elusive Tomb of Queen Nefertiti may lie behind the walls of Tutankhamun's Burial Chamber

An archaeologist studying electronic scans of the walls of the ancient Egyptian King Tutankhamun's tomb thinks he has found a false wall that may lead to the tomb of Nefertiti, the famous successor to Akhenaten and the probable mother of Tutankhamun. The location of Nefertiti's tomb has been one of Egyptology’s biggest mysteries, and archaeologist Nicholas Reeves thinks further exploration behind the walls of King Tutankhamun's tomb at the Amarna Royal Tombs in the Valley of Kings is warranted.“Cautious evaluation of the Factum Arte scans over the course of several months has yielded results which are beyond intriguing: indications of two previously unknown doorways, one set within a larger partition wall and both seemingly untouched since antiquity,” writes Reeves in a new paper on his study of the scans. “The implications are extraordinary: for, if digital appearance translates into physical reality, it seems we are now faced not merely with the prospect of a new, Tutankhamun-era storeroom to the west; to the north appears to be signalled a continuation of tomb KV 62 and within these uncharted depths an earlier royal interment—that of Nefertiti herself, celebrated consort, co-regent, and eventual successor of pharaoh Akhenaten.”

An archaeologist studying electronic scans of the walls of the ancient Egyptian King Tutankhamun's tomb thinks he has found a false wall that may lead to the tomb of Nefertiti, the famous successor to Akhenaten and the probable mother of Tutankhamun. The location of Nefertiti's tomb has been one of Egyptology’s biggest mysteries, and archaeologist Nicholas Reeves thinks further exploration behind the walls of King Tutankhamun's tomb at the Amarna Royal Tombs in the Valley of Kings is warranted.“Cautious evaluation of the Factum Arte scans over the course of several months has yielded results which are beyond intriguing: indications of two previously unknown doorways, one set within a larger partition wall and both seemingly untouched since antiquity,” writes Reeves in a new paper on his study of the scans. “The implications are extraordinary: for, if digital appearance translates into physical reality, it seems we are now faced not merely with the prospect of a new, Tutankhamun-era storeroom to the west; to the north appears to be signalled a continuation of tomb KV 62 and within these uncharted depths an earlier royal interment—that of Nefertiti herself, celebrated consort, co-regent, and eventual successor of pharaoh Akhenaten.” The Wilbour Plaque, Brooklyn Museum. Nefertiti is shown nearly as large as her husband, indicating her importance. Image source:

Brooklyn Museum

.The paintings on the walls of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, which Factum Arte scanned and which the University of Arizona's Reeves studied, obscure the surface. But Reeves says there are telltale signs in the cracks and fissures of the wall that may indicate rooms behind the walls, which have been assumed to be solid limestone.Howard Carter found Tutankhamun's tomb intact in 1922 with more than 5,000 artifacts.

The Wilbour Plaque, Brooklyn Museum. Nefertiti is shown nearly as large as her husband, indicating her importance. Image source:

Brooklyn Museum

.The paintings on the walls of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, which Factum Arte scanned and which the University of Arizona's Reeves studied, obscure the surface. But Reeves says there are telltale signs in the cracks and fissures of the wall that may indicate rooms behind the walls, which have been assumed to be solid limestone.Howard Carter found Tutankhamun's tomb intact in 1922 with more than 5,000 artifacts.The paintings within this [burial chamber] room document the principal stages in Tutankhamun's physical and spiritual transition from this world to the realm of the gods. Although affected by serious mould growth, these painted surfaces remain both sound and intact. Covering as they do virtually every inch of the walls, the underlying architecture is almost wholly obscured. Carter, followed by all Egyptologists since, seems to have accepted that beneath lay only bedrock, influenced in this understanding by the fact that four eccentrically placed amulet emplacements cut through the decoration to expose solid limestone.The Mysterious Disappearance of Nefertiti, Ruler of the NileThe Quest to find Nefertiti, Queen of the NilePharaoh AkhenatenThe Art of Amarna: Akhenaten and his life under the Sun

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Reeves posits that when Tutankhamun died in 1332 BC, his tomb displaced part of Nefertiti's tomb and assumed some of her burial goods and space because of his untimely and unexpected death. Further, though he says it can't be proven yet, he speculates Nefertiti herself “will have inherited, adapted, and employed the full, formal burial equipment originally produced for Akhenaten.”Though King Tutankamun's tomb was richly decorated and appointed, it was small for a king. Reeves says it may be an extension of Nefertiti's larger tomb.Nefertiti is one of the most famous queens of ancient Egypt, second only to Cleopatra. While many aspects of her life are well-documented, there are many mysteries surrounding her death and burial. While hundreds of royal mummies have already been recovered in Egypt, Nefertiti’s mummy has remained elusive.

Screenshot from a Factum Arte scan of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber, behind which, a researcher says, may lie the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. (

Factum-arte.org scan

)Reeves posits that when Tutankhamun died in 1332 BC, his tomb displaced part of Nefertiti's tomb and assumed some of her burial goods and space because of his untimely and unexpected death. Further, though he says it can't be proven yet, he speculates Nefertiti herself “will have inherited, adapted, and employed the full, formal burial equipment originally produced for Akhenaten.”Though King Tutankamun's tomb was richly decorated and appointed, it was small for a king. Reeves says it may be an extension of Nefertiti's larger tomb.Nefertiti is one of the most famous queens of ancient Egypt, second only to Cleopatra. While many aspects of her life are well-documented, there are many mysteries surrounding her death and burial. While hundreds of royal mummies have already been recovered in Egypt, Nefertiti’s mummy has remained elusive. Theban Mapping Project's diagram of King Tutankamun's known tomb, in gray, and two possible new rooms in yellow and red, one of which, a researcher says, cold be Queen Nefertiti's burial chamber.Neferneferuaten Nefertiti lived from 1370 BC until 1340 BC. She was married to the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten, who gave her many titles, including: Great Royal Wife, Hereditary Princess, Great of Praises, Lady of Grace, Sweet of Love, Lady of The Two Lands, Great King’s Wife, Lady of all Women, and Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt. Nefertiti was known for being very beautiful, and her name means “the beautiful one has come.” While little is known about Nefertiti’s origins, it is believed that she was from an Egyptian town known as Akhmim and was closely related to a high official named Ay. Others believe Nefertiti came from a foreign country.In an interview with The Economist, Reeves said: “If I’m wrong, I’m wrong; but if I’m right this is potentially the biggest archaeological discovery ever made.”Featured image: The iconic bust of Nefertiti, discovered by Ludwig Borchardt, is part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, currently on display in the Altes Museum.

Image Source

.By Mark Miller

Theban Mapping Project's diagram of King Tutankamun's known tomb, in gray, and two possible new rooms in yellow and red, one of which, a researcher says, cold be Queen Nefertiti's burial chamber.Neferneferuaten Nefertiti lived from 1370 BC until 1340 BC. She was married to the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten, who gave her many titles, including: Great Royal Wife, Hereditary Princess, Great of Praises, Lady of Grace, Sweet of Love, Lady of The Two Lands, Great King’s Wife, Lady of all Women, and Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt. Nefertiti was known for being very beautiful, and her name means “the beautiful one has come.” While little is known about Nefertiti’s origins, it is believed that she was from an Egyptian town known as Akhmim and was closely related to a high official named Ay. Others believe Nefertiti came from a foreign country.In an interview with The Economist, Reeves said: “If I’m wrong, I’m wrong; but if I’m right this is potentially the biggest archaeological discovery ever made.”Featured image: The iconic bust of Nefertiti, discovered by Ludwig Borchardt, is part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, currently on display in the Altes Museum.

Image Source

.By Mark MillerAncient Origins

Published on August 13, 2015 07:39

History Trivia - Treaty of Noyon signed

August 13

523 John I was elected Roman Catholic pope. He ended the Acacian Schism, bringing reunification of the Eastern and Western churches by restoring peace between the papacy and the Byzantine Emperor Justin I. He also set the rules for the Alexandrian calendar computation of the date of Easter, which was eventually accepted throughout the West.

1415 Hundred Years War: King Henry V of England army landed on mouth of the Seine River, and organized the siege of the town of Harfleur (now part of Le Havre).

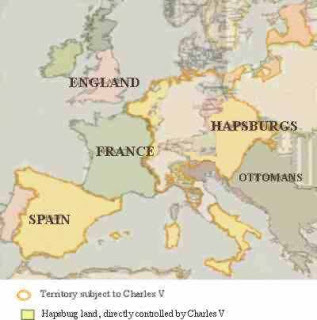

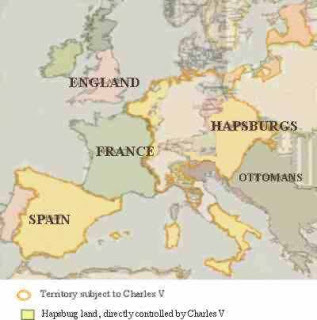

1516 The Treaty of Noyon between France and Spain was signed. Francis I of France recognized Charles's claim to Naples, and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor recognized Francis' claim to Milan.

523 John I was elected Roman Catholic pope. He ended the Acacian Schism, bringing reunification of the Eastern and Western churches by restoring peace between the papacy and the Byzantine Emperor Justin I. He also set the rules for the Alexandrian calendar computation of the date of Easter, which was eventually accepted throughout the West.

1415 Hundred Years War: King Henry V of England army landed on mouth of the Seine River, and organized the siege of the town of Harfleur (now part of Le Havre).

1516 The Treaty of Noyon between France and Spain was signed. Francis I of France recognized Charles's claim to Naples, and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor recognized Francis' claim to Milan.

Published on August 13, 2015 01:30

August 12, 2015

Ancient Route of Famous Anglo-Viking Battle Unearthed in England

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists have discovered an ancient road and route along which Saxon troops retreated in 1066 when they were defeated by a Viking army in the Battle of Fulford. The finding has provided new insights into the famous battle.

Culture24 reports that experts from the Battle of Fulford Project made the discovery of a section of clay meeting a peat-filled ditch while investigating the site of the Battle of Fulford near York in England. The aim of the project is to piece together the full story behind the battle site in Fulford, which has caused much debate between historians.

According to Chas Jones, leader of the project, the section of road uncovered was the main route heading south from York that the English army retreated along when they were outflanked by the Vikings. Numerous relics were also uncovered including pieces of iron and bits of bone.

The Headless Vikings of DorsetThe 10th century chronicle of the violent, orgiastic funeral of a Viking chieftainWaves of invaders came to Britain but left few genes, new study saysIs the Period of the Vikings older than what believed?“It will take a few months to analyze all of the material,” Chas Jones told Culture24, “but there can be no doubt that this road was the axis for the battle fought at the ford in 1066.”

The view towards Fulford Hall in the village on the outskirts of York. (Paul Glazzard / geograph.org.uk (CC license))The Battle of Fulford was fought between King Harald III of Norway, also known as Harald Hardrada ("hard ruler"), and the Northern Earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, who were loyal to Harold Godwinson, the usurper to the throne following the death of Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor. Harald Hardrada, like William of Normandy, and King Harold Godwinson, was another claimant to the throne.

The view towards Fulford Hall in the village on the outskirts of York. (Paul Glazzard / geograph.org.uk (CC license))The Battle of Fulford was fought between King Harald III of Norway, also known as Harald Hardrada ("hard ruler"), and the Northern Earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, who were loyal to Harold Godwinson, the usurper to the throne following the death of Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor. Harald Hardrada, like William of Normandy, and King Harold Godwinson, was another claimant to the throne.Harald was also supported by his English ally Tostig Godwinson, the exiled brother of Harold Godwinson. Tostig made a pact with Harald and agreed to support his invasion of English.

Norse leader Harald Hardrada led his troops to victory. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Hardrada and Tostig sailed along the River Ouse towards the city of York in September 1066. The Norse Vikings, along with their English ally, were met by the Saxons on 20 September. While there were heavy casualties on both sides, the battle was a decisive victory for the Vikings.

Norse leader Harald Hardrada led his troops to victory. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Hardrada and Tostig sailed along the River Ouse towards the city of York in September 1066. The Norse Vikings, along with their English ally, were met by the Saxons on 20 September. While there were heavy casualties on both sides, the battle was a decisive victory for the Vikings.Newly-discovered ancient fortress reveals architectural accomplishments of VikingsNot just about the booty: New study sheds light on reasons for Viking raidsArchaeologists Discover 1,000-year-old Viking 'Parliament' in ScotlandThe Viking Berserkers – fierce warriors or drug-fuelled madmen?Following their victory, Harald and his army retired to Stamford Bridge, located 7 miles (11 km) east of York. Meanwhile, Harold Godwinson sent his troops from London to York to meet them and just five days after the Battle of Fulford, the Saxons launched a surprise attack on the Viking army and defeated them. During the battle, Harald Hardrada sustained a hit to the neck from an arrow, but survived.

Featured image: The recently discovered ancient route associated with the Battle of Fulford. (Chas Jones)

By April Holloway

Published on August 12, 2015 07:37

History Trivia - Cleopatra commits suicide

August 12

30 BC –Cleopatra VII Philopator, the last ruler of the Egyptian Ptolemaic dynasty, committed suicide, allegedly by means of an asp bite.

1099 First Crusade: Battle of Ascalon: Crusaders under the command of Godfrey of Bouillon defeated Fatimid forces led by Al-Afdal Shahanshah. This is considered the last engagement of the First Crusade.

1332 Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of David II, infant son of Robert the Bruce and rebels supporting the Balliol claim in 1332, and is a significant battle of the Second War of Scottish Independence.

30 BC –Cleopatra VII Philopator, the last ruler of the Egyptian Ptolemaic dynasty, committed suicide, allegedly by means of an asp bite.

1099 First Crusade: Battle of Ascalon: Crusaders under the command of Godfrey of Bouillon defeated Fatimid forces led by Al-Afdal Shahanshah. This is considered the last engagement of the First Crusade.

1332 Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of David II, infant son of Robert the Bruce and rebels supporting the Balliol claim in 1332, and is a significant battle of the Second War of Scottish Independence.

Published on August 12, 2015 01:30