Foster Dickson's Blog, page 88

November 1, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #91

In short, for a crucially large number of Southern whites, segregation is not as important as any one or a combination of the following: economic profit, political power, good government, an absence of violence, food, recreation, an education, keeping a job.

Furthermore, there is also the powerful force of conformity, both to society at large and to close friends and associates. Conformity is a favorite target of intellectual disdain; few liberals will confess that it is not conformity in the abstract which they abhor, but conformity to certain values which they find reprehensible. Liberals would be delighted, for instance, to have conformity to the principle of free speech. And there is a world of difference between conformity to racism and conformity to the idea of equality. The tendency of people to seek security in the approval of their peers and superiors can be used as a great moral weapon as well as a divisive tool.

– from the chapter “Is the Southern White Unfathomable?” in Howard Zinn’s The Southern Mystique, published in 1964

Filed under: Civil Rights, Social Justice, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

October 29, 2015

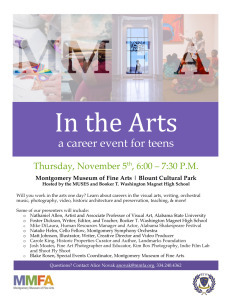

In the Arts @ MMFA, November 5th from 6 – 7:30 PM

October 27, 2015

Apologia, re: Whitehurst

Those familiar with the literary term apologia will know that it only loosely ties to our English word apology. In English, to make an apology focuses on regret and the desire to seek forgiveness; the Latin apologia means something more like a defense, a justification, an explanation of circumstance, with perhaps a some measure of regret attached to it. An apologist writes with the sense that some justification is needed, rather than with the sense that forgiveness is sought.

Two and half years ago, I began what might be the most difficult work I’ve ever encountered: telling the story of the Whitehurst Case. When Bernard Whitehurst III called me about writing this book, then met me soon after with his mother Florence to discuss the project, I had virtually no knowledge of this historical episode, which occurred from late 1975 until mid-1977. The Whitehurst Case is true crime, Southern history, Hollywood action-flick, and family-struggle story all rolled into one. The story has all the makings of a Hollywood thriller, or of a Lifetime movie. Yet, this time it’s real, not manufactured— before Michael Brown, before Rodney King, there was Bernard Whitehurst, Jr.

The conundrum of the Whitehurst Case is archetypally American: a post-Civil Rights era police shooting of an unarmed black man, who turned out not to be the suspect they sought, followed by a sundry array of democratic efforts and public outcries to obtain justice for the man and his family, which all failed in one way or another. The convoluted scenario offered little promise of that justice: allegations of a planted gun, erased dispatch tapes, conflicting accounts, fearful witnesses. Yet, a young lawyer stood up to the local power structure, filing a civil case against the city. Later, one city councilman proffered a resolution to compensate the family. The upsurge in tension had the district attorney at odds with the police and the newspaper belittling the mayor. The wild situation soon caused the state’s attorney general to intervene. However, when the dust settled, the mayor, the police chief and a number of officers had resigned from their jobs, though no one paid out any money and no one went to jail. The city moved on, and the Whitehurst family had to, too.

Since June 2013, I have been sifting through the rubble of the Whitehurst Case, trying to piece together a coherent narrative that could rest between two covers. The combination of spotty cooperation, lost records, and faded memories have made the work exceptionally difficult. Many of the key players in the Whitehurst Case have passed away, and the few who remain hardly want to rhapsodize about those events. Some people have expressed quite bluntly that they’d rather I left this subject alone. However, what remains are a smattering of people still willing to talk, a cumbersome process of scrolling through news archives, and the slow grind of piecing together a mosaic out of broken shards. Sometimes I spend hours in my office, re-reading documents, comparing articles to interviews, going back over my list of unfinished tasks. I know it must seem, to the family and to the people I’ve interviewed, as though I disappear for long stretches of time; the somber truth is: writing is slow, methodical work, and a person has to love it to do it all.

Now two-and-a-half years in, with about 55,000 words written, I’m gearing up to finish. I’ve stepped away from the manuscript for a bit – the start of a school year is always hectic – yet the time has allowed the fog in my mind to clear. (Anyone who has ever stared at a computer screen for too long will know what I mean.) There are still important people left to talk to. Others, whose silence I’ve not failed to notice, need to be contacted again. I want this telling to be as full and complete and accurate as possible, and the only way I can do that is if people talk to me. My goal is to have the manuscript completed by the summer of 2016. Hearing some long-lost perspective after the book is published won’t do anyone any good.

This book needs to be written— frankly, it needed to be written years ago. I didn’t really begin this project until it was almost too late, with so many of the men involved now gone. But it’s getting written, and it will be published, and that’s what matters.

This December 2 is the fortieth anniversary of the killing of Bernard Whitehurst, Jr. That morning, at 10 AM, the city will dedicate a second historic marker to the Whitehurst Case; this one will be at 546 Holcombe Street, the address where a Montgomery police officer shot Whitehurst. (The first marker, seen above, stands in Lister Hill Plaza, adjacent to City Hall.) The ceremony is open to the public.

Filed under: Civil Rights, Social Justice, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

October 25, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #90

They will not know I have gone away to come back. For the ones I left behind. For the ones who cannot out.

– the entire last paragraph in the novel The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

Filed under: Literature, Social Justice, Teaching, Writing and Editing

October 22, 2015

Book Arts in New Orleans

Last weekend, the New Orleans Advocate ran a nice little profile piece on book artists in New Orleans, including The Southern Letterpress, titled “In an age of e-readers and mass production, book artists create volumes by hand.” It seemed worthy of sharing.

Filed under: Arts, Louisiana, The Deep South

October 20, 2015

Two printers at Kentuck

This last weekend, the Kentuck Festival of the Arts in Northport, Alabama featured something like two or three hundred artists, as well as a couple dozen musicians, bands, readers and storytellers. Among all those folks, with their colorful and sometimes bizarre wares spread out among the tall pines, I’m insatiably drawn to the printers: letterpress, screen printing, block cuts, I don’t care. Quirky little print shops seem to be popping up like mushrooms around the South – or maybe I’m just noticing more of them – but no matter how many I see, I still have to stop and gawk. Scott Peek at Standard Deluxe, Jessica Peterson’s The Southern Letterpress, and the University of Alabama Book Arts folks are three of my favorites who display at the festival, but this year, I might have found a new favorite or two.

I had walked about halfway around the festival’s outer loop, when I stopped at Debra Riffe‘s booth. The endearing simplicity of her work caught my eye; her curt though unique socially conscious adages are stated in bold blocky letters, some with images iconically African American. As I was browsing the broadsides, I overheard her explaining to another customer that all of her work is made from block cuts, even the lettering, which was surprising. We started talking after that customer gone, about our common interest in literacy and food equity and about letterpress printer Amos Kennedy when I told her that her work reminded me a little of his. Debra Riffe is another printer to keep an eye on; originally from Tupelo, Mississippi and now living in Birmingham, she will next be displaying at the Yellowhammer Fair on November 8.

Then I found another new printer that I really liked right near the main gate, after I had basically gone full circle. Green Pea Press had their screen printing equipment set up right in front of their little booth, and the smiling folks manning the booth had the standard fare: t-shirts, broadsides, postcards. Where the seriousness of Debra Riffe’s work had drawn me in, the opposite was true of Green Pea Press. As I looked over a t-shirt that read “Support LocAL,” emphasizing the state’s name in the final letters, I looked up at an apron, hanging on the wall, which featured a line drawing of a Weber kettle and the words: Why you all up in my grill? I laughed out loud! I couldn’t help it. I won’t spoil the witty, comical surprises in the rest of their work, but I’d say to go take a look. Based in Huntsville, Green Pea Press calls itself a “printmaking collective” and is part of Dustin Timbrook’s Lowe Mill project.

Now, if I just had a couple thousand-hundred-million dollars to buy all the stuff that I liked . . .

Filed under: Alabama, Arts, The Deep South

October 18, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #89

A literary work also arouses expectations that it needs to fulfill or it will cease to be read. The deepest anxieties of literature are literary; indeed, in my view, they define the literary and become all but identical with it. A poem, a novel, or a play acquires all of humanity’s disorders, including the fear or mortality, which in the art of literature is transmitted into the quest to be canonical, to join the communal or societal memory.

from “An Elegy for the Canon,” the opening chapter of Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages

Filed under: Education, Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

October 15, 2015

Them Damn Super Chickens!

A friend posted this TED talk to Facebook a few days ago, and I had to share it, too. These talks may not give the Moses-with-stone-tablets truth of all things, but they do give some truly fine ideas to consider. Maybe it’s time that we all agree on something: Nobody likes a super chicken!

Filed under: Education, Social Justice, Teaching

October 13, 2015

Sallie Mae and Me, part three: Lesson learned

*Continued from two previous posts: “Running down the Devil, or Sallie Mae and Me” and “Sallie Mae and Me, part two”

After speaking with customer service reps from both entities, I gave up on reaching any satisfactory answers about my student loans from Sallie Mae/Navient or FAFSA. I also knew that calling the Department of Education to dispute my school’s Title I status was pretty pointless. If it were possible for my school to have received Title I funds, I feel certain that someone in our school system would have arranged for that . . . it was time to give up on the Teacher Forgiveness program. That dog won’t hunt.

Having to look elsewhere, I found The National Consumer Law Center, whose motto (or subtitle) is: “Advancing Fairness in the Marketplace for All.” Atop the NCLC’s page on student loans, I found this within the page’s mission statement:

We also seek to increase public understanding of student lending issues and to identify policy solutions to promote access to education, lessen student debt burdens and make loan repayment more manageable.

These sounded like my kind of folks.

On their slightly intimidating list of “Hot Topics,” two reports with long, academic titles caught my eye: “The Sallie Mae Saga: a Government-Created, Student Debt Fueled Profit Machine” from January 2014, and “The Student Loan Default Trap”— look out, Lee Siegel!

The “Introduction” to “The Sallie Mae Saga” reveals some scary shit about the student loan giant. First, Sallie Mae was created during the Richard “I am not a crook” Nixon administration, and it “became a fully private company in 2004”, during the presidency of George W. Bush, who also tried to privatize Social Security. A little further down the “Introduction,” we learn that Sallie Mae “has been extraordinarily profitable,” and their “return on equity” is “one of the highest among American companies.”

Continuing through “The Sallie Mae Saga,” I learned about the immensity of the corporation that I’m struggling against. From its Nixonian inception in 1972 until 1988, the company’s “assets grew from $1.6 billion to $28.6 billion.” From 2010 through 2013, as I’ve plugged away with my monthly $204, Sallie Mae’s “net income” has risen from hundreds of millions to well over a billion dollars annually. To ensure continuity of these trends, they spent more than $22 million on lobbying efforts from 2007 through 2013.

So while I’ve been sending my little piddling payments month after month, the folks at Sallie Mae/Navient are earning and squirreling away amounts of money that are unfathomable to me. Let’s take a minute to remind ourselves of what a billion dollars looks like when it’s all written out— $1,000,000,000.00 According to this report, Sallie Mae/Navient has a couple dozen of those.

Curious too about the “The Student Loan Default Trap” report, I downloaded it and began with the Executive Summary. As I read the first paragraph, I thought, You’ve got to be kidding!

The United States government has responded to growing levels of student loan debt by creating an array of borrower assistance programs. Getting this relief, however, is rarely easy. Government programs are unnecessarily complex and borrowers too often confront an impenetrable bureaucracy that prevents them from accessing their rights. To compound these problems, there are few reliable resources borrowers can turn to if they need help.

That sounds distinctly familiar . . . As an ordinary guy, a John Q. Taxpayer, just scratching the surface of this conundrum has been frustrating. Reading on, I saw that this report has little to do with my situation. It mainly details abuses and predatory practices related to customers who are in default. Apparently, a whole other side of the industry exists, which preys on uninformed, desperate or easily duped people whose debt is completely out of hand. I may be aggravated by my situation, but I’ve still got it in hand (for now).

Also on the NCLC’s student loan webpage was a report titled “Statement before the Middle Class Prosperity Project: Tackling the Student Loan Debt Crisis.” In this report, a lawyer for the NCLC outlines their hopes about student-loan reform, beginning with an assertion that “despite some declines in profits, the federal government is still expected to produce $110 billion in profits over the next decade.” Should a public-sector program, which was designed to help low-income people get an education, be turning massive profits? No, what we need is “a government agency that clearly puts students first.” While I understand and respect that Sallie Mae and all other student-loan providers must turn a profit to stay capitalized and to pay their employees, keep the lights on, etc. . . . a billion dollars a year in profits seems a little much.

Once again, however, this report has little to do with me. The NCLC’s mission, stated overtly, is to help low-income people, and I’ll be honest: I’m not living in poverty. The programs that help people stand up against the student-loan system are mainly designed to fight abusive and predatory practices against the most vulnerable folks. While I agree with that mission, and I applaud it, I still have to ask, what about people like me?

Essentially, this brief stint of research has revealed that I have no viable options. The Teacher Loan Forgiveness program is not open to me, nor is any other program like it. I have not found any non-governmental or non-profit grant programs that would help me. Other than repayment, consolidation remains my only other choice.

Yet, using the Federal Direct Loans Consolidation website, my best option under consolidation would be to pay $224 per month for 240 months. If the aggravating Sallie Mae/Navient rep from the frustrating phone call is correct, then I’ll have Sallie Mae/Navient paid off in eighteen years. So the moot question is: would I rather keep my current plan, or should I send more money for a longer period of time? Let’s see:

consolidation: $224 x 240 months = $53,760

or

my current plan: $204 x 216 months = $44,064

That’s a no-brainer. Loan consolidation would actually set me back further, causing me to pay nearly $10,000 more than sticking with my current plan. Sadly, the interest that Sallie Mae will earn on my student loans would pay for a year or two of college for one of my children . . . who will probably have to get student loans, because I won’t be able to save as much for their education.

Bringing this discussion closer to home: because our per-capita incomes and cost-of-living are lower in the Deep South, being strapped with debt is even harder. We don’t earn as much money down here – Alabama’s per capita income is 83% of the national average – so a monthly payment that might be feasible by national standards can be excessive in the Deep South. In “2015’s Best and Worst States for Student Debt,” WalletHub.com ranks my home state of Alabama among the worst, at 44th. Sadly, that same report ranked Alabama 50th, just ahead of dead-last Mississippi, in “Highest Unemployment Rate for People Aged 25 to 34,” and our Deep Southern neighbors in Louisiana and Mississippi ranked in the dubious bottom-five for highest default rates.

According to The Institute for College Access & Success, the average Alabamian who carries student loans has a balance of $28,895. That number has a complicated context since many of the Alabamians with that much debt didn’t complete a degree. A similar page on the Debt.com website gives the same average dollar-amount and ranks Alabama as the 12th worst state for student loan debt. I think about a person who owes that kind of money but only earns a pittance of salary at a low-wage job. Paying it back would be virtually impossible.

For more on how student-loan debt affects the larger economy, read “The Ripple Effects of Rising Student Debt” from the New York Times (May 24, 2014).

What have I learned from this brief foray into the satanic netherworld of the student loan industry?

Hindsight is 20/20— I should have started paying back my loans on the day I got them. I should have been sending money every month while I was working on my teaching certificate and while I was working on my master’s degree. At the time, the stash of cash to pay all-at-once tuition bills wasn’t there, but most months, I could have sent a few bucks to Sallie Mae to chip away at my loan balance. Yet, I handled it the way most people would: I didn’t have to make a payment, so I didn’t. And that interest on those unsubsidized loans was accruing the whole time . . . It will be a very expensive err in judgment. I’ll know how expensive when I’m nearly sixty.

All said and done, I’d be better off without my master’s degree, because the bump-up in teacher pay multiplied by the number of years I’ll earn that bump-up won’t be worth what I’ll spend (principle and interest) to have the degree. In short, unless I get another higher-paying job that requires a master’s, I’d be better off if I were less educated.

I’ve also learned that two “pro-business” Republican presidents, Nixon and Dubya, took a good government program and turned it into a for-profit system. When ordinary people like me see a government program that provides low-interest education loans, we assume that we are entering into an agreement with an institution that serves the public good. Not so. These companies are earning billions of dollars on the backs of hard-working people who try to better themselves. Unless a grantee is able to pay back the loans quickly, accepting student loans is making a deal with the Devil.

Filed under: Alabama, Education, Social Justice, The Deep South

October 12, 2015

Suitcase Junket on “Folk Alley” last night

I heard this guy on “Folk Alley” on NPR last night, driving home from the hellish Atlanta airport, and thought he was worthy of a share. The project is called Suitcase Junket. He’s got this one-man band thing going on, but it’s a long way from what you’d call vaudeville.