Foster Dickson's Blog, page 80

May 1, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #117

May I never want a merely prosperous life,

accepting pain or great wealth at the expense

of happiness here in my heart.

— spoken by Medea, to Jason, in Euripides’ classical tragedy Medea, translated by Ian Johnston

Filed under: Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

April 28, 2016

For Job Creation, Local is Better

In his 1993 book The Selling of the South " target="_blank">The Selling of the South, historian James C. Cobb writes about Southern states’ Depression-era invention of using tax breaks, free land, and cheap labor to woo businesses to locate new industrial facilities in our region to remedy the desperate unemployment of the period. The innovator responsible for putting this strategy in motion in the mid-1930s was Mississippi’s governor Hugh White, and at the time, his state desperately needed any help it could get. The Mississippi Historical Society’s History Now website explains:

" target="_blank">The Selling of the South, historian James C. Cobb writes about Southern states’ Depression-era invention of using tax breaks, free land, and cheap labor to woo businesses to locate new industrial facilities in our region to remedy the desperate unemployment of the period. The innovator responsible for putting this strategy in motion in the mid-1930s was Mississippi’s governor Hugh White, and at the time, his state desperately needed any help it could get. The Mississippi Historical Society’s History Now website explains:

By any measure, Mississippi entered the Great Depression far behind the rest of the nation. The mere 52,000 industrial jobs the state claimed in 1929 fell to 28,000 by 1933. Bank deposits dropped from $101 million to $49 million over the same three-year period. Nearly 1,800 retail stores closed as sales shrank from $413 million to $140 million. Farm income was reduced by 64 percent. The average annual income, already the worst in the nation at $287, fell to an unbelievable $117. On a single day in 1932, one-fourth of the state’s farm land was sold for taxes.

White’s “Balancing Agriculture with Industry” program (BAWI), which was adopted in various forms all over the South, combined the state government’s power to organize and negotiate with a reliance on local chambers of commerce recognizing and offering up their own communities’ resources. Essentially, local leaders would identify unused land, untapped labor, and money available for investment, and the state would help the community find a company that could use what they had. BAWI may have been a viable engine for economic recovery in a mostly agrarian society— but as a long-term solution in the modern Sun Belt South, not so much.

Cobb’s final two chapters are titled “The Price of Progress” and “A New South with Old Problems.” To begin the final chapter, he relays that the 1960s and 1970s were marked by rampant environmental pollution by these out-of-state corporations, and thus by the 1980s,

southern leaders found themselves confronting the question of how cheap labor, low taxes, and minimal constraints on growth could be rationalized in the face of expectations of rapid improvement in the general standard of living, expanded social services, social stability, and all the other factors that influence the quality of life in any region. (254)

The 1980s were three decades ago, and we’re still trying to answer that question: how do you sell Southern workers without selling them out?

In the eighty years since 1936, this unfortunate modus operandi for decreasing the South’s interminable poverty has yielded its fair share of negative results, prime among them the consequence of having our natural and human resources exploited and the profits shipped elsewhere in the country. The South may have gained jobs here and there for a time, but the extractive capitalists who have taken us up on our offers (reduced taxes, free land and improvements, government-sponsored job training) do so with the plan of taking the real booty home with them. Drive around the rural Deep South, and you will find our countryside littered with near-empty small towns that have a boarded-up industrial facility nearby.

The states of the Deep South have been touting this job-creation strategy for eight decades, through three or four generations of workers, but our leaders somehow haven’t seen – or at least haven’t acted on – the obvious truths: these outside companies suck out the little economic sustenance we do have, and when they’re done with us, they shutter the operation, write off the loss, and move on. Yet, the bulwarks stand firm, protecting the negotiations until, every couple of months, at some sparsely attended ribbon-cutting ceremony they brag that a new employer is coming to town. We always hear about the jobs, and we never hear about what we gave away to bring them. In the long run, BAWI-style initiatives do not offer viable solutions to Southern economic problems.

In February, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) released a new report titled “State Job Creation Strategies Often Off Base”. The report, which isn’t specific to the South, is the culmination of a study that tracked job creation over several decades, even reaching back into the 1980s, and their conclusions are simple:

The vast majority of jobs are created by businesses that start up or are already present in a state — not by the relocation or branching into a state by out-of-state firms. Jobs that move into one state from another typically represent only 1 to 4 percent of total job creation each year, depending on the state.

and

During periods of healthy economic growth, startups and young, fast-growing companies are responsible for most new jobs.

The evidence seems overwhelming, when we read that:

fully 87 percent of all 1995 – 2013 gross private-sector job creation was “home grown” — it came from startups, the expansion of employment at existing establishments, and the creation of new in-state locations by businesses already headquartered in the state.

If you’re still skeptical, just look at the state-by-state numbers on page 8 of the report. There isn’t much variance from one to the next. The facts are obvious, thus investing state money and favor on bolstering small, locally owned businesses makes far more sense than traveling far and wide with giveaway offers. Alabama, where I live, is a state of four-and-a-half million people with a 6.2% unemployment rate – well above the national rate of 4.9% – and a multi-year pattern of budget shortfalls. What we need are thousands of good-paying jobs and millions of dollars in tax revenue.

Just this month, we had another announcement in Alabama, three hundred jobs coming from a company with offices in five other states. While I’m sure that the three hundred people who get the jobs will be glad, we aren’t told in the press release what those jobs will cost our state.

The leaders in the Deep South who continue with this job-creation strategy don’t seem to understand in 2016 what one historian understood in the early 1990s. The CBPP has tracked it across three recent decades, and it seems pretty clear: giveaways to out-of-state companies aren’t worth the few jobs they bring. If Deep Southern state leaders truly want to improve quality of life, there are far better ways that are right under their noses: develop and support local businesses, work with the EPA to forbid pollution, give all working people a living wage, and ensure access to healthcare for everyone. I’d say that’s all that most working people ask for: a good job, a decent salary, and a healthy and safe place to call home.

Filed under: Alabama, Local Issues, Social Justice, Sun Belt, The Deep South

April 26, 2016

CNN’s “United Shades of America”

If you missed Sunday night’s premier of W. Kamau Bell’s “United Shades of America,” then you missed one the most important shows to come along in a long time. In the opening episode, Bell, who is an African-American comedian, seeks out the Ku Klux Klan in three different small-town locales, and goes to interview members onsite.

Here’s a link to the trailer:

Filed under: Civil Rights, multiculturalism, Social Justice

April 24, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #116

Think about tackling the problems when you don’t have the answers. Once you get in gear, you’ll be surprised how easily some of the solutions appear.

– from chapter six, “Prototyping is the Shorthand of Innovation,” in IDEO " target="_blank">The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm by Tom Kelley, with Jonathon Littman

" target="_blank">The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm by Tom Kelley, with Jonathon Littman

Filed under: Critical Thinking, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

April 21, 2016

The 2016 Alabama Book Festival

On Saturday, April 23, the Alabama Book Festival will held in Montgomery’s Old Alabama Town. The website offers plenty of information about the authors who are presenting and the vendors and exhibitors who are showing off their wares. My students and I will have a display table in the exhibitors’ area so be sure to come by and see us, too!

Filed under: Alabama, Education, Literature, Local Issues, Poetry, Writing and Editing

April 19, 2016

Listening: Sturgill Simpson’s “A Sailor’s Guide to Earth”

Led off by his cover of Nirvana’s “In Bloom,” which was released in advance, Sturgill Simpson’s new album “A Sailor’s Guide to Earth” came out on Friday, April 15. I woke up that morning to a notification on my iPhone that I could now access my pre-ordered copy— woohoo! Simpson has been a darling of alt-country for some time now, and Garden & Gun‘s recent article pairing him with Merle Haggard billed him as a “rising outlaw country star,” the heir apparent to the recently deceased singer. (In an eerie coincidence, when the subject of playing a show together came up, Haggard replied, “Yeah. We’re going to do a lot more shows together, I think, if I don’t die or something.”)

I was a late-comer to country music, not really even dabbling in it until my late teens. Though I was fortunate enough to be an impressionable youngster when Kenny Rogers was singing “The Gambler” and when Waylon could be heard weekly opening up for “The Dukes of Hazzard,” I had the misfortune of reaching my formative musical years during the ultra-cheesy era of Reba McEntire, Garth Brooks, and Trisha Yearwood. As a teenager, I was more interested in AC/DC than in Allen Jackson. It wasn’t until I was about-grown that Johnny Cash broke through my musical prejudices, via Rick Rubin a la Trent Reznor. I had heard The Grateful Dead’s version of “Mama Tried” before I ever knew that Merle sang it, and it took me a while to get over my clean-cut mother’s biting remarks about Willie Nelson’s nasty long hair and beard to give him a good listen. (I’ve now seen Willie live four times.) But, once I finally did discover this music for myself, great country music – not Shania Twain, and definitely not Luke Bryan – I’ve fallen head over heels in love with it.

So, I was quite pleased to find Sturgill Simpson among the current wreckage. When I tune in to country radio, I can’t help but wonder what’s out there beside The Band Perry and Little Big Town – this is what wins CMAs? – and I also have to wonder why alt-country and Americana acts like Jason Isbell are getting ignored. But there is hope beyond the airwaves and CMT. Sturgill Simpson’s sound and style are so much truer to what country music should be than Big & Rich could imagine in their wildest dreams. When I first heard Simpson’s voice, I found myself wondering whether he sounded like Randy Travis, Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard, or a mixture of all three. Matt Hendrickson put it well in Garden & Gun:

the Kentucky native has struck a nerve by defying Nashville expectations, with many seeing him as a modern antidote to everything that’s wrong with country music these days—the glitz, the beer-’n’-truck bros, the dance beats, the blandness.

That Friday morning, I got up and made my coffee, then scrambled around with the kids to get them ready for school, before I took a minute during the scurrying on that gloomy, cool morning to answer the call of iTunes and listen to the first track on “A Sailor’s Guide to Earth.” After a faint bell-ringing intro, the album begins with piano, and then comes Simpson’s voice, raw and pure. “Welcome to Earth (Pollywog)” starts out as an old-school country lament, but quickly shifts into ’60s-soul number, complete with horns blasting and shaky tambourines.

After a slow and eerie track two, “Breakers Roar,” Simpson returns to that good ‘ol barroom soul music in “Keep It Between the Lines,” this time adding in that Allman Brothers-style slide guitar, similar to what we heard on the previous album’s “Living the Dream.” The next song, “Sea Stories,” moves us into pure country with strumming guitars and pedal-steel accompaniment.

Track five is the pre-released Nirvana cover. During my anti-country teenage years, Nirvana’s Nevermind was a staple of my senior-year-into-college musical diet, and to hear this really nice interpretation of it— yep, I was thinking, he did that . . . and it works. Revamping a post-punk classic from an album that almost every Gen-Xer owns into a dynamic country song where the horns bust in halfway through and drive it forward— that’s risky. But it works. Bravo, Mr. Simpson.

He follows up that four-minute triumph with a swaggering, guitar-driven Southern rock tune called “Brace for Impact (Live a Little).” This one was also pre-released. At nearly six-minutes, the instrumental sections run a little long, but not too bad. One of things that I have liked about Sturgill Simpson’s music is his ability to combine things I’ve heard before into something new that I haven’t heard. In “Brace for Impact,” the vocals reminded me of Bad Company in the ’70s, while the music side kind of reminded me a little bit of JJ Cale’s “Ride Me High,” though not as funky.

Rolling into the final third of “A Sailor’s Guide to Earth,” Simpson settles into the really nice thing that he has created. The Hammond organ-heavy “All Around You” could easily have been an Otis Redding song, and after that, “Oh Sarah” moves along softly with accompaniment from a strings section.

Closing out, Simpson cranks up the electric guitars for “Call to Arms.” We’re back in the barroom for track nine. In this one, the instrumental sections are perfect, jumping from solo to solo, jacking up the energy, and quieting down only to ramp back up. We get the feeling that he has waited until the end to really cut loose, to show us what he and his band can do.

“A Sailor’s Guide to Earth” was worth the wait. From his previous work, I’ve been partial to “Livin’ the Dream” and “Voices,” back to back songs on his Metamodern Sounds in County Music album, and frankly, I had just about worn out what I already had. “A Sailor’s Guide” is not necessarily a pure country album, but hell, is there such a thing as pure country? If Johnny Cash can put miriachi brass on “Ring of Fire” and still be called country, then Simpson’s strays into soul and Southern rock won’t hurt his chances.

If you want to hear more from Sturgill Simpson before you buy “A Sailor’s Guide to Earth,” you can listen to him on NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts or on Live on KEXP. Both programs are from 2014.

Filed under: Arts, kentucky, Music, the South

April 17, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #115

Inquiry, finally, is intrusive. It slides into impacted formations of social and public experiences that will seek to divert or receive the intruding gesture, but such spaces do not accept the critical gesture easily. Perhaps this is why poetry provides an opportune genre of linguistic inventiveness and moral certitude. Poetry plays into a contradictory public imagination of the art’s power to produce revolution or voiced dissent. Poetry can put forward the affective possibilities that motivate existing situations.

– from the “Afterword: Poetry as a Modality of Rhetoric in Modernist Inquiry” in Poets Beyond the Barricade " target="_blank">Poets Beyond the Barricade: Rhetoric, Citizenship, and Dissent after 1960 by Dale M. Smith

" target="_blank">Poets Beyond the Barricade: Rhetoric, Citizenship, and Dissent after 1960 by Dale M. Smith

Filed under: Critical Thinking, Poetry, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

April 14, 2016

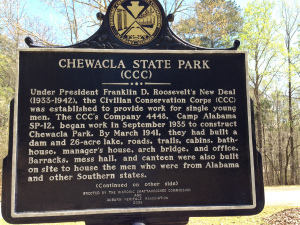

Chewacla State Park, early spring

April 12, 2016

Alabamiana: The Murder of Sloan Rowan, 1912

According to the Atlanta Constitution‘s coverage of his murder, Sloan Rowan was sitting on a stopped train in Montgomery’s Union Station, waiting to head home to the small community of Benton, in Lowndes County, when C. Walter Jones boarded the train, found Rowan, and unloaded both barrels of a shotgun “at close range.” As one could guess, “Rowan died almost immediately.”

At the time of the murder, in July 1912, Sloan Rowan was a merchant in Benton and a grand jury witness in an arson case against Jones, who was accused of burning several stores there. The accused man’s opposition to Rowan’s participation is evident in its degree of violence. That startling and grisly image of the shotgun-blast killing from the ominously titled article, “Hunted His Foe and Killed Him,” leads into an explanation of Jones’ next move, which may be even stranger than the first: rather than flee or try to shoot his way out, Jones then “walked to the county jail and gave himself up.” He was charged with murder.

I found the narrative about this startling event in Alabama history when I was thumbing through The Heritage of Lowndes County book in the Alabama Department of Archives & History’s Research Room. My mother’s maternal family line, the Taylors and the Deans, lived in Lowndes County through half of the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, and I was fishing for information about them when I went right past the bold heading “The Murder of Sloan Rowan,” and flipped back. Though the tale of Rowan and Jones has nothing to do with my family, it was too compelling to ignore.

That section in The Heritage of Lowndes County is fairly short, only spanning a little more than one half-page column, and its content is heavily laden with quotes from news sources of the time. Jones, it says, was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death within two weeks, and his was “the first execution of a white man in Montgomery County since the Civil War.” Toward the end of the section, I learned that C. Walter Jones must’ve been a man to steer way clear of. Jones had killed another unarmed man from Benton, Charles Miller, in 1901, and he had shot a black man (but not killed him) in Montgomery in the 1890s. He was also known for “selling illegal whiskey.”

Despite his criminal predilections, Jones occupies an unenviable and fortuitous place in Alabama history: his botched hanging was a catalyst for Alabama’s use of the electric chair. When Jones was executed in April 1913, hanging was the method that Alabama used to carry out a death sentence. However, in his case, the rope that was used was either too long or it slipped, and Jones’ feet touched the ground. Rather than having his neck snapped by the impact the taut rope, which would have meant a quick and sudden death, Jones was strangled by the noose for more than thirty minutes.

According to coverage from Winston County, Alabama, at the time, that scene was common:

Under the system now in vogue, condemned men are hanged by the sheriff of the county in which they are convicted. Very often the hanging is a failure and the victims die horrible deaths.

I don’t know how smart a person has to be to cut a piece of rope seven feet shorter than the distance to the ground, but it seems that some lawmen couldn’t do that math. Seeking a “more humane” way to execute convicted criminals, then-governor Emmet O’Neal called for the use of the electric chair, which was supposed to be better.

It was ten years after the botched execution of C. Walter Jones before Alabama’s legislature yielded to O’Neal’s suggestion. In 1923, the state’s governing assembly changed the form of execution, though the change was not implemented until 1927, and the so-called Yellow Mama become Alabama’s preferred tool for officially sanctioned ending of human lives. (According to al.com, Yellow Mama was painted that color because the highway department that constructed it used its abundant supply of road-striping paint.) Use of Yellow Mama continued until 2002.

Among its plethora of ongoing legal quagmires, Alabama’s continued employment of the death penalty is another questionable and still-unresolved matter. If news sources from a hundred years ago are to be believed, the logistical realities of the death penalty have long been recognized as flawed. While we must recognize the tragedy of the murder of an unarmed father and husband who was trying to play his role in serving justice against a well-known menace to society, the state’s role in carrying out justice for Sloan Rowan was no less tragic. (Remember, in 1913, Alabama was still in the thick of its cruel and highly immoral convict-lease system, which wasn’t abolished until 1928— roughly the same time as Yellow Mama was brought on the scene.) C. Walter Jones may have been a bootlegger, arsonist, and murderer, but what was done to him at the hands of the law was not much better than what he did to others.

Filed under: Alabama, Black Belt, The Deep South

April 10, 2016

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #114

Start with your own interests. You should be curious about people, events, documents, or problems considered in the course. This curiosity should make you pose some questions naturally. [ . . . ] The good historian is a questioner.

– from the section, “Step 1: Find A Topic,” in chapter four, “Gathering Information and Writing Drafts,” in A Short Guide To Writing About History, Third Edition by Richard Marius

Filed under: Teaching, Writing and Editing