Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 53

October 25, 2016

Could the World Series Help Clinton (or Trump) Win Ohio?

In the near future, two implacably opposed forces will collide in Ohio. The two sides are backed by long-suffering supporters hailing from places that have not always been served well by the last decade—or decades. Many of them have been left behind by triumphs in other parts of the country, but hope the right outcome in November could mark a change of luck. The result, either way, will be historic.

I speak not of the presidential election, but of the World Series, pitting the Cleveland Indians against the Chicago Cubs. But what if the outcome on the baseball field could influence the results at the voting booth?

Sure, coverage of elections increasingly resembles SportsCenter, but that’s not the issue at hand. Because social scientists have too much free time on their hands or because they are sports fans—but we repeat ourselves—there’s some research into the connection between the results of sporting contests and the results of elections.

Political scientists often counterpose pocketbook voting—am I better off than I was four years ago?—and sociotropic voting: Are things better in general than they were four years ago? Sports seems to affect sociotropic voting patterns, making voters feel better in general and then aiding incumbents. The most directly useful study is by Andrew J. Healy, Neil Malhotra, and Cecilia Hyunjung Mo, who sought out to explore how “irrelevant” events can have a bearing on the way voters decide. They started with local college-football games:

We find that a win in the 10 d[ays] before Election Day causes the incumbent to receive an additional 1.61 percentage points of the vote in Senate, gubernatorial, and presidential elections, with the effect being larger for teams with stronger fan support. In addition to conducting placebo tests based on postelection games, we demonstrate these effects by using the betting market's estimate of a team's probability of winning the game before it occurs to isolate the surprise component of game outcomes. We corroborate these aggregate-level results with a survey that we conducted during the 2009 NCAA men's college basketball tournament, where we find that surprising wins and losses affect presidential approval.

Some of the results seem practically comical. During 2009 March Madness, an upset victory by a team translated to a 2.3-percentage point bump in approval of Barack Obama by that team’s fans. For comparison, Obama’s overall approval only went up 7 points when Osama bin Laden was killed. (Now, imagine if Obama had managed to kill Duke. That’d be good for for at least a double-digit rise.)

In another study, Michael K. Miller studied 39 mayoral elections in American cities between 1948 and 2009 and found that the wins produced a larger effect even than unemployment rates, a commonly used metric for electoral predictions: “Winning sports records boost incumbents’ vote totals and likelihoods of reelection, exceeding in magnitude the effect of variation in unemployment.”

That offers us some rough ideas about how important game results can be to elections, but it requires some extrapolation and guess work, since there’s not a true incumbent in the presidential race, and since neither study covers baseball.

Really, a win for either the Cubs or the Indians would be somewhat unexpected. Both teams have had strong seasons, though the Cubs entered the season as a juggernaut, while the Indians have been consistently underestimated. Nonetheless, both teams are famously hapless. The Indians last won a championship in 1948, and has only gotten far enough to lose in 1954, 1995, and 1997. Yet the Tribe’s track record of futility pales in comparison to their rivals. The Cubs haven’t won a Fall Classic since 1908; they haven’t even appeared in one since 1945.

But for the purposes of this exercise, the Cubs’ fortunes are largely irrelevant. A win for the Cubs might break a longer drought, but it’s hard to imagine it having much effect on the election, since Illinois is a lock for the Democrat, Hillary Clinton. There could be some downballot effects, though. In the U.S. Senate race, Mark Kirk, the Republican incumbent, is expected to lose to Democrat Tammy Duckworth, but a Cubs win might give him a little wind at his back. Cubs territory also stretches into Indiana, a solid-red state, and one where there’s no incumbent in either the Senate or gubernatorial elections; and west into a small portion of Iowa, a closely contested swing state.

More important is what happens in the Ohio election. The state is always a closely fought swing state, and this year it has swung back and forth, with Donald Trump, the Republican, looking like the probable winner, only to see his standing erode in the last couple of weeks. FiveThirtyEight now gives Clinton a small edge in the state. No Republican has ever been elected without winning Ohio. When Democrats win, they do so by running up their margins in a few urban centers—especially Cuyahoga County, home to Cleveland.

If the Indians were to win the World Series, one would expect it to be a boost for the Clinton campaign. (It is, however, only a coincidence that the team plays at Progressive Field.) First, it would be unexpected: The Cubs are heavy favorites coming into the series. Second, while there is no incumbent in the race, Clinton is seeking to replace a president from her own party, meaning warm feelings about the status quo would redound to help her. If the series took all seven games, the Fall Classic would end on November 2 in Cleveland, and six days later still-jubilant Clevelanders might jauntily skip to the polls to vote Clinton.

“With a small percentage of people who are on the fence, that could be the extra little piece of the puzzle that will get them to the polls,” says Edward Horowitz, a professor of political communication at Cleveland State University. “Ohio is very tight right now. In a very close election, 1 percent of the vote, a half a percent of the vote can make a difference.”

“There’s a sense around here that this is Cleveland’s year, from the Cavs to successfully hosting the Republican National Convention to the Indians doing so well.”

If the Indians lose, however, one would expect it would feed anti-incumbent feeling and give Trump a boost—plus it might drive down turnout among glum Tribe fans in Cuyahoga County.

Horowitz speculated that even if the Indians can’t break their dry spell, though, Clinton may already be enjoying some sociotropic bounce in the Forest City.

“Here in Cuyahoga County, people are unbelievably excited about the Tribe being in the World Series,” he said. “There’s sort of a sense around here that this is Cleveland’s year, from the Cavs [winning the NBA Championship in June] to successfully hosting the Republican National Convention to the Indians doing so well. It’s like Cleveland has officially made the turnaround from the Mistake on the Lake to being one of America’s prime cities.”

Since the Indians have had so little championship success, it’s hard to find good parallels to the present day, but that 1948 win might shed some light. The 1948 Indians had limped to the World Series, only winning the pennant in a one-game playoff—although by some accounts, they were seen as favorites over the Boston Braves. The Indians won the series in six games, wrapping up on October 11 (the season, and the postseason, were shorter then.) A month later, incumbent Harry S Truman defeated Thomas Dewey in one of the great upsets in modern history—and he did so while carrying the state of Ohio.

Clinton grew up in the Chicago suburbs and is a lifelong Cubs fan, but over the years, her allegiance has seemed to waver for political reasons, including a flirtation with the Yankees during her time running for office and serving in New York. If there were ever a time to be Cubs fan, it would be now, with the team’s return to the World Series. But if there were ever a time for Clinton to put political expedience over longtime loyalty, this might be it, too. However much joy a Cubs win might bring the girl from Park Ridge, an Indians win could hand her the White House.

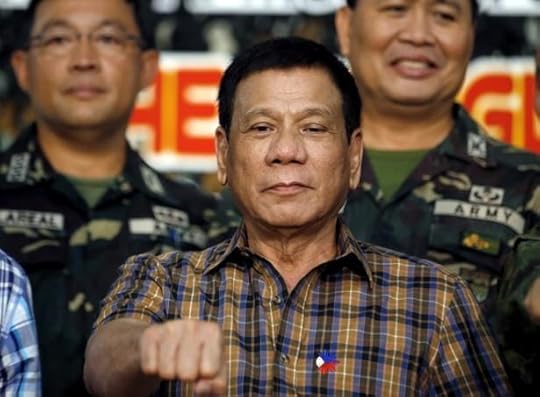

What Is Rodrigo Duterte Trying to Achieve?

Just what is Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte thinking? Last week Duterte visited with China’s leader, Xi Jinping, and then appeared to trample on his country’s relations with the U.S., telling 200 Chinese business leaders in the Great Hall of People, "In this venue, your honors, in this venue, I announce my separation from the United States."

"Both in military—not maybe social—but economics also, America has lost," he said.

The Philippines has been the U.S.’s closest ally in Southeast Asia since it became independent in 1946. It once celebrated its independence on July 4 (now June 12), and for a while that day was also called Filipino-American Friendship Day. Filipinos hold America in such high regard, in fact, they have a more favorable opinion of the U.S. than the U.S. does of itself. That’s why Duterte’s words have puzzled so many people: Are they the words of a politician who’s pitting two superpowers against each other? Are they another controversial comment from a man who specializes in them? Does this signal the end of the U.S.-Philippines relationship? Maybe. Yes. Too soon to tell.

Duterte, the leader of the PDP–Laban, the left-wing populist party, has praised Adolf Hitler’s efficiency in mass murder, bragged about his sexual prowess, pondered why he wasn’t the first to assault a raped woman, insulted the pope for causing traffic delays, and boasted about personally executing three men—to name just a few of his controversial statements. But it’s his bloody war on crime—and the rhetoric that backs it—that has drawn the most criticism since he took office in June.

Duterte was previously the mayor of Davao, where he ran an anti-crime campaign that human-rights groups say used death squads to kill more than 1,000 people without trial. When he ran for president, he promised to do the same in all the Philippines.

“You drug pushers, hold-up men and do-nothings, you better go out. Because I'd kill you,” he said. “I'll dump all of you into Manila Bay, and fatten all the fish there."

He has been true to his word: Some 3,500 people have died in his war on crime, many extrajudicially. Western nations expressed concern. Duterte responded to one such criticism by saying: “I read the condemnation of the European Union against me. I will tell them fuck you.” In that same vein, he called President Obama a “son of a whore.” The U.S. has mostly been mild in its responses (Obama called him a “colorful guy”) though on Monday a senior State Department official said the Filipino president’s consistently contentious remarks have created “uncertainty about the Philippines’ intentions” and its future with the U.S.

The Philippines is now one of Southeast Asia’s strongest economies with GDP growth at about 6 percent a year and trade with the U.S. at $18 billion last year. But even as Filipinos are seeking a more independent voice in global affairs, China’s regional ambitions have many people worried. Never warm, China-Philippines relations had grown worse, exacerbated by the dispute over the South China Sea, which Beijing claims in its entirety. Looming over this tension is the 1951 U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty under which the U.S. will aid the Philippines in the event of an attack by China. But many Filipinos say they believe the U.S. “does not do anything with, in and for the Philippines unless it serves U.S. interests,” wrote the Manila Times, in an op-ed. Indeed, just before he took the oath of office in June, Duterte said he’d asked the U.S. ambassador to Manila if the U.S. would step in if the dispute with China escalates. "Only if you are attacked," Duterte recalled the envoy saying. That apparently wasn’t a satisfying answer, and Duterte said he’d start talking to China, and while he’s at it, with Russia.

So far, it seems Duterte’s decision has paid off. In a four-day trip last week to China, where he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Duterte came away with $24 billion of funding and pledges of infrastructure investment in exchange for shelving the dispute over the South China Sea.

“I've realigned myself in your ideological flow,” Duterte said to Chinese leaders, “and maybe I will also go to Russia to talk to Putin and tell him that there are three of us against the world— China, Philippines, and Russia.”

The U.S. wasn’t pleased; neither were some of Duterte’s advisers.

"Let me clarify. The president did not talk about separation," Trade Minister Ramon Lopez said, shortly after Duterte had used the specific word, “separation,” to describe his intended breakup with the U.S. That prompted Josh Earnest, the White House spokesman, to say, “I’ve dubbed that person the Filipino Mike Pence”—a reference to Donald Trump’s running mate who has found himself in the position of walking back Trump’s words. And like with Trump in the U.S. election, Duterte’s novel approach to politics has kept people guessing if what he said is what he means. So I spoke with Steven Rood, the Philippine Country Representative of the Asia Foundation, who told me Duterte is treating world leaders like he treated people when he was mayor of Davao.

“It’s his style,” Rood told me, “to push people away and try and let them get back on his good side.”

Despite what he’s said about the U.S., Duterte may simply be playing two superpowers against each other. Rood said Duterte might express strong views, but he doesn’t get in the way of experts carrying out policy. So while he might threaten to kick the U.S. military out, as he did earlier this month, it doesn’t mean he’s talked it over much with his secretary of defense, or that there’s a high likelihood of this happening.

“He just let’s people get on with their jobs and doesn’t interfere,” Rood said, adding “there is a fair amount of flexibility in the bureaucracy.”

And because Duterte says so many contrary things, no one can hold him to any of it. In fact, last Friday, a day after he returned from China, Duterte took it all back. He said he did not want to separate from the U.S., that it now seemed to be “in the best interest of my countrymen to maintain that relationship.”

If Duterte has proven anything—and if we can gain any insight into his latest moves— it’s that he will say whatever is expedient. Duterte admitted as much last August, when he recounted to reporters how upset the U.S. Embassy became after he called Ambassador Philip Goldberg a “gay son of a bitch.” U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry then came to visit Duterte and Delfin Lorenzana, the Philippines secretary of national defense.

"Kerry came here,” Duterte said, “we had a meal, and he left me and Delfin $33 million. I said, ‘OK, maybe we should offend them more.”

October 24, 2016

The Joy of David S. Pumpkins

This weekend’s episode of Saturday Night Live offered a mini masterpiece: a gloriously silly Halloween-themed piece revolving around a “Haunted Elevator” ride and its unusual star attraction. Beck Bennett and Kate McKinnon played a couple looking for spooky thrills who instead found something far more bewildering: a pumpkin-suited man who would randomly appear alongside two cheerful skeletons and perform a dance routine. “Who are you?” asked a frustrated Bennett after the man (played by Tom Hanks) appeared for the second time. “I’m David Pumpkins!” came the reply.

McKinnon followed up: “Yeah, and David Pumpkins is … ?”

“His own thing!”

“And the skeletons are … ?”

“PART OF IT!” the skeletons shouted triumphantly.

Who is David S. Pumpkins? Why does he have a middle initial? Why is he featured in 73 of the Haunted Elevator’s 100 floors? What do the dancing skeletons have to do with any of this? The sketch was written by SNL’s writer Streeter Seidell and performers Mikey Day and Bobby Moynihan (who played the skeletons), and it’d have been goofily funny without the self-analysis. But once Bennett and McKinnon started asking questions, it felt like one of the standout SNL sketches of the year. “Is he from a local commercial?” McKinnon asked trying to make sense the strange character. “I am so in the weeds with David Pumpkins!” Bennett cried.

The sketch has since become an internet sensation. It was overall a very strong night for SNL: The episode featured another star turn from Alec Baldwin as Donald Trump, a brilliant “Black Jeopardy” that inverted the sketch’s typical premise, and a mocking commercial for the premium cable “sadcoms” that have taken over the Emmys comedy category. But David Pumpkins was so simple, and so memorably self-aware, that his costume has already sold out on Amazon. It’s the rare sketch that I immediately rewound on my DVR to watch again, the kind where viewers are instantly struck by as many questions as Bennett and McKinnon were. Just where did this demented nonsense spring from?

The show’s topical sketches are its lifeblood, of course, along with the reliable zingers of Weekend Update and its celebrity impressions, but there’s nothing like an out-of-nowhere classic to pore over again and again. The best kind of Saturday Night Live sketch is often one that starts analyzing itself. I’ve shown everyone I know my favorite SNL sketch of all time—“Robot Repair,” starring Phil Hartman—because it has the same perfect mix of originality and reflexiveness, and begins to deconstruct its own premise about halfway through.

“Haunted Elevator” also reminded me of “FBI Simulator,” a sketch from last season that saw Larry David playing an orange-suited weirdo who keeps popping in front of cadets during their firearm training. David’s character, Kevin Roberts, had a weird catchphrase (“can a bitch get a donut?”) and an incongruity with the rest of the sketch. “I’m pretty sure that kind of man does not exist in society,” Kenan Thompson complained of Roberts in the sketch. “I mean, he looks like he came out of a 1980s computer game.” But that sketch worked partly because everyone in it seemed on the verge of breaking character (all the actors involved visibly swallowed a laugh at one point or another). A video posted after the fact that showed David bursting out in peals of laughter during rehearsal is just as funny as the sketch itself.

“Haunted Elevator,” meanwhile, only worked because everyone was 100 percent committed to the silliness. Hanks, already in the pantheon of SNL’s greatest hosts (this was his ninth go-round in the job), somehow fully embodied the character of David S. Pumpkins—whoever that is. His dance moves were perfectly in sync with the inane synth music. There was a gleeful tone to his voice every time he asked “Any questions?” The only time I’ve seen Hanks more locked into a bit is when he got caught in a dry-cleaning bag on an edition of Celebrity Jeopardy.

As happens with many hit SNL sketches, viewers will probably be sick of David Pumpkins in a week. Perhaps Halloween parties will be filled with amateur attempts at the costume (though if you don’t have two skeleton partners, why bother?). But happily, the sketch appeared to be a one-off, and unless Hanks is joining the show’s cast anytime soon they won’t have a chance to run it into the ground. Either way, now is the time to cherish David S. Pumpkins. Any questions?

Drake’s Ill-Conceived Digs at Mental Illness

When the rapper Kid Cudi announced he’d checked himself into rehab for depression and suicidal thoughts earlier this month, it sparked a social-media conversation about stigmas around mental illness in America generally, and among black men specifically. The hashtag #YouGoodMan went viral, people shared their favorite hip-hop songs about mental health, and many praised Cudi for his courage in going public.

Now, a new track from Drake makes clear how powerful the stigma Cudi defied remains. In “Two Birds, One Stone,” the rapper seems to describe Cudi, saying,

You were the man on the moon

Now you just go through your phases

Life of the angry and famous

Rap like I know I'm the greatest

Then give you the tropical flavors

Still never been on hiatus

You stay xanned and perked up

So when reality set in you don’t gotta face it

The lines come across as not-quite-explicit disses about Cudi’s struggles, implying that those struggles are a sign of him being weaker than Drake. In this, Drake is answering a call-out from Cudi, who in September included the Torontonian superstar in a Twitter tirade about emcees who talk up their abilities but rely on ghostwriters and who have proven to be false friends to him.

Drake’s developed a habit of replying to rappers who snipe at him, so it’s not surprising that he’s hitting back against Cudi. The rest of “Two Birds, One Stone” defends Drake against accusations of fakeness—“They try to tell you I'm not the realest / Like I'm some privileged kid that never sat through a prison visit”—and dismisses rivals who exaggerate their pasts. These are battles, for the most part, about the substance of what rappers do. It's the kind of boasting and negging that Drake has built a career on.

But the mental-illness stuff is different. He’s ridiculing a sensitive personal issue for millions of people, one that’s only made worse when people ridicule it. On social media, many listeners have expressed disapproval:

kid cudi is struggling with depression/is getting help but drake makes a diss track mocking him for his depression...drake is trash for that

— #1 kimberly hater (@apunkgrl) October 24, 2016

Drake just reinforced the black stigma that mental illness is a weakness, a flaw and not the disease it is. Get well Kid Cudi

— Hiiiiiiiiii :) (@CulturallyAlive) October 24, 2016

Reactions like those have in turn kicked up debate about whether anything should actually be “off limits” in rap battles. Some of the genre’s most famous feuds have involved death threats and deeply homophobic language, after all.

You could plausibly argue that it’s a different time now than when those feuds were happening. But you might not even need to go that far in order to say Drake misstepped. For one thing, his lines about Cudi would seem close to hypocrisy, undercutting his own virtues as a rapper famous for emotional venting and vulnerability. For another, he’s highlighted what made Cudi’s decision to go public with his struggles so remarkable. Drake’s attacking the guy for something he did exactly in spite of these kinds of attacks. He’s proving just how much guts his rival had—not the sign of a good diss.

Drake's Ill-Conceived Digs at Mental Illness

When the rapper Kid Cudi announced he’d checked himself into rehab for depression and suicidal thoughts earlier this month, it sparked a social-media conversation about stigmas around mental illness in America generally, and among black men specifically. The hashtag #YouGoodMan went viral, people shared their favorite hip-hop songs about mental health, and many praised Cudi for his courage in going public.

Now, a new track from Drake makes clear how powerful the stigma Cudi defied remains. In “Two Birds, One Stone,” the rapper seems to describe Cudi, saying,

You were the man on the moon

Now you just go through your phases

Life of the angry and famous

Rap like I know I'm the greatest

Then give you the tropical flavors

Still never been on hiatus

You stay xanned and perked up

So when reality set in you don’t gotta face it

The lines come across as not-quite-explicit disses about Cudi’s struggles, implying that those struggles are a sign of him being weaker than Drake. In this, Drake is answering a call-out from Cudi, who in September included the Torontonian superstar in a Twitter tirade about emcees who talk up their abilities but rely on ghostwriters and who have proven to be false friends to him.

Drake’s developed a habit of replying to rappers who snipe at him, so it’s not surprising that he’s hitting back against Cudi. The rest of “Two Birds, One Stone” defends Drake against accusations of fakeness—“They try to tell you I'm not the realest / Like I'm some privileged kid that never sat through a prison visit”—and dismisses rivals who exaggerate their pasts. These are battles, for the most part, about the substance of what rappers do. It's the kind of boasting and negging that Drake has built a career on.

But the mental-illness stuff is different. He’s ridiculing a sensitive personal issue for millions of people, one that’s only made worse when people ridicule it. On social media, many listeners have expressed disapproval:

kid cudi is struggling with depression/is getting help but drake makes a diss track mocking him for his depression...drake is trash for that

— #1 kimberly hater (@apunkgrl) October 24, 2016

Drake just reinforced the black stigma that mental illness is a weakness, a flaw and not the disease it is. Get well Kid Cudi

— Hiiiiiiiiii :) (@CulturallyAlive) October 24, 2016

Reactions like those have in turn kicked up debate about whether anything should actually be “off limits” in rap battles. Some of the genre’s most famous feuds have involved death threats and deeply homophobic language, after all.

You could plausibly argue that it’s a different time now than when those feuds were happening. But you might not even need to go that far in order to say Drake misstepped. For one thing, his lines about Cudi would seem close to hypocrisy, undercutting his own virtues as a rapper famous for emotional venting and vulnerability. For another, he’s highlighted what made Cudi’s decision to go public with his struggles so remarkable. Drake’s attacking the guy for something he did exactly in spite of these kinds of attacks. He’s proving just how much guts his rival had—not the sign of a good diss.

The Walking Dead Might Be Its Own Villain

Lenika Cruz and David Sims discuss the first episode of the new season of The Walking Dead. While they won’t be reviewing weekly episodes this season, they will be covering any noteworthy developments, so stay tuned.

David Sims: There’s a simple way to figure out when a popular TV show has gone bad, and that’s when it seems to exist only to punish its audience. The Walking Dead spent the entirety of its last season building up the arrival of Negan (Jeffrey Dean Morgan), a baseball bat-wielding villain who promised to tear the show’s group of heroes asunder. The show spent months promising at least one major death at his hands. Characters we met spoke of him in portentous tones; Chris Hardwick, the energetic host of the show’s propaganda organ Talking Dead, helped tease fan excitement; and writers online made elaborate predictions about who would survive.

Negan finally arrived in the show’s April finale, kidnapping many of the main characters and killing one of them with his barbed-wire bat after a drawn-out game of eeny meeny miny moe. Viewers didn’t find out who; Negan simply struck the camera until blood ran down the screen, an eerily apt metaphor for the show’s treatment of its audience. Sunday night, in the episode “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be,” fans finally found out who his victim was, after 20 further minutes of further drawn-out tension. The episode flashed forward to a traumatized Rick (Andrew Lincoln), watched Negan’s theatrical build-up to the murders two more times, and then finally, revealed the truth. Abraham (Michael Cudlitz) was the first to go, serving almost as a misdirect, since Negan then beat the fan-favorite character Glenn (Steven Yeun) to death as well.

Both murders were horrifically gory, with Negan pausing to behold his deformed victims after one strike of the bat, before then furiously mashing their head into paste. Just as in the comics, Glenn’s eye popped out of his skull—his death mirrored the notorious 100th issue of the comics almost exactly, with Negan using the murder to demonstrate his supremacy over Rick’s group. But it’s hard to know where the show can go from here. If the idea is to build Negan into a grand villain you want to see toppled, then mission accomplished. But given The Walking Dead’s history of dragging out such stories, it’s likely we’ll get a whole season or more of Negan dominating and brutalizing the group while they devise plans to strike back.

In essence, it all seems far too obvious. This is forgivable in a pulpy comic book, which is just 22 pages per month; story arcs can be forgivably slow, since they come in such short, intense bursts. But even one hour-long episode of Negan proved too much for me—I don’t know that I’d really want to check back in with him for 60 minutes every week. There’s not much to his character outside of his sheer cruelty. Jeffrey Dean Morgan is a grade-A ham who can turn the thinnest antagonist into a magnetic screen presence just by playing him with gusto, but that doesn’t forgive the inherent weakness of Negan’s character. He’s a bully, the leader of a grand protection racket who takes care of zombies and in return demands food and goods from nearby communities. If people step out of line, he beats them to death.

The Walking Dead has long been interested in exploring man’s inhumanity. Even though it’s set in the zombie apocalypse, its chief villains have always been people, tyrants who turn the new world to their advantage. Negan is just another one of those, someone you’d like to see dispatched in three episodes. But the entire point of “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be” was that his character isn’t going anywhere. The ritualized murder of Glenn and Abraham was part of a larger scheme to convince Rick never to rebel against him. One assumes Rick will eventually regain his nerve, but after this week’s nightmarish violence, that will likely take a whole season. Lenika, you’ve been watching and reviewing The Walking Dead with me for years now—do you have the stomach to stay on board for this upcoming season?

Lenika Cruz: If I’m being honest, it’s hard to say definitively. Yes, even after declaring in April that we were fed up with this show, we both tuned in to find out what happened. How could we not? It’s hard to quit watching a show solely on principle, or out of righteous anger, after sticking with it for six seasons through good and bad. Though I was still incensed about the way The Walking Dead left things off in the season-six finale, I wanted to find out whether the new story arc would indeed justify the show’s disastrous cliffhanger (as the show’s executives had insisted it would).

This show doesn’t really need to tell a consistently good story in order to get people to tune in.

Like you David, I don’t think it did. The season-seven premiere answered the central question—who will Negan kill?—but gave already disgruntled viewers plenty else to be frustrated by. The episode dragged out the reveal of Negan’s first victim, Abraham, for a full 22 minutes. The emotional impact of watching Glenn later get his skull bashed in was diminished by the messiness of the moments leading up to that moment, plus the finale cliffhanger, plus the dumpster fakeout. I felt as though I had already grieved Glenn back in season six and couldn’t bring myself to do that again. (Unfortunately, I had heard about Jeffrey Dean Morgan confirming that Negan would kill more than one person in the premiere, so the Abraham death wasn’t much of a misdirect for me.)

I recognize that the purpose of the episode was to break Rick Grimes, to extinguish any remaining belief in him that he was the alpha. But unlike in a more decentralized but comparable violent show such as Game of Thrones—where few heroes are safe, and where the power dynamics can always shift dramatically—The Walking Dead is limited in terms of plot reversals. While it could be interesting to explore how the group deals with living in total submission to Negan and his Saviors, it’s hard to imagine a future for the show in which Negan doesn’t get his comeuppance and Rick’s rule is restored in some form or another. Sunday’s episode did very little to sell me on the idea that a smart, complex season lies ahead.

Let’s be real—no one still watching this show today has a weak tolerance for violence. So the fact that so many people (judging from social media) were disgusted by the sheer gore on display suggests that The Walking Dead veered into something much darker; call it torture porn or sadism or cruelty for cruelty’s sake. There’s nothing stopping bloodshed from coinciding with or even amplifying good storytelling (the comics handled the bat-bashing scene much differently and more elegantly, even if it was still graphic). But the grisly theatrics, combined with the awkward momentum, were difficult to accept as a necessary cost in service of some higher-minded, novel idea.

I’ve come to realize that I don’t watch The Walking Dead because I think it’s a holistically great series (even though it has had many moments of brilliance). On some level I regret all the hours I could have invested in a different, better show—but I keep coming back out of habit, out of hope that something will change, because I still genuinely care about many of the characters. I’m far from the only person who feels this way, and AMC and the show’s executives know that all too well. Which is why they can take advantage of the show’s massive viewership and pull stunts that defy narrative integrity in the name of artistry. The show doesn’t really need to tell a consistently good story in order to get people to tune in (though I know there are fans who genuinely thought this was a terrific premiere episode that exceeded their expectations). If I keep paying attention, it’ll be out of something far closer to empty resignation than love.

SNL’s Surprisingly Affectionate Portrayal of a Trump Supporter

SNL’s ongoing “Black Jeopardy” series has been, in part, about divisions. In each edition, black American contestants answer Kenan Thompson’s clues with in-jokes, slang, and their shared opinions while an outsider—say, Elizabeth Banks as the living incarnation of Becky, Louis C.K. as a BYU African American Studies professor, or Drake as a black Canadian—just show their cluelessness.

When Tom Hanks showed up in a “Make America Great Again” hat and bald-eagle shirt to play the contestant “Doug” this weekend, it seemed like the set-up for the ugliest culture clash yet. The 2016 election has been a reminder of the country’s profound racial fault lines, and SNL hasn’t exactly been forgiving toward the Republican nominee on that front: Its version of Trump hasn’t been able to tell black people apart, and it aired a mock ad painting his supporters as white supremacists—which, inarguably, some of them really are.

But this time the Black Jeopardy contestants came to be pleasantly surprised as Doug answered the questions correctly. SNL’s viewers might have felt a similar sense of amazement as they realized that this particular sketch didn’t quite come at the expense of Trump’s supporters. Smartly and hilariously, it suggested an idea that’s novel in 2016: Maybe America isn’t as helplessly divided as it seems.

Part of the common ground is economics—many white Trump supporters are as familiar with financial desperation as many black Americans are. Thompson’s host Darnell Hayes asks Doug whether he’s sure he wants to play black Jeopardy; Doug says he’s just hoping to win some money, so “get ’er done.” When lottery scratcher tickets get mentioned, Doug chimes in, “I play that every week.” On a question of what to do when your brakes are busted, Doug correctly answers, “You better go to that dude in my neighborhood who’ll fix anything for 40 dollars” (Hayes: “You know Cecil?!” “Yeah, but my Cecil’s name is Jimmy”).

But the sketch goes further, pointing out that social conditions shape worldview and culture. Everyone on stage distrusts the idea of giving their thumbprint to an iPhone. Everyone on stage agrees that elections are decided by the elite (the Illumanti?) before the votes are cast. Doug’s lifestyle even means he’s come to love Tyler Perry movies: “I bought a box set at Walmart. And if I can laugh and pray in 90 minutes, that’s money well spent.”

Hanks and Thompson’s performances help nail the sketch’s humor and strange poignance. The gravelly Doug seems matter-of-fact as he battles his nervousness, stumbling into the occasional questionable remark about “you people.” The host Hayes, meanwhile, goes from dismissal to total delight. At one point, he comes over to shake Doug’s hand; Doug recoils, scared Hayes has been offended, but then they awkwardly embrace.

A vision of healing? Not quite. The final Jeopardy question category is “Lives That Matter.” Everyone freezes, knowing that Doug’s answer—which we don’t see—might not be so agreeable as his previous ones. “Well it was good while it lasted, Doug,” Hayes says. One implication is race isn’t just an illusory divide. Another is both hopeful and a bit depressing: People casting opposing ballots in November might not realize just how much they have in common.

October 22, 2016

Black Mirror’s ‘Hated in the Nation’ Considers Online Outrage

Sophie Gilbert and David Sims will be discussing the new season of Netflix’s Black Mirror, considering alternate episodes. The reviews contain spoilers; don’t read further than you’ve watched. See all of their coverage here.

Sophie, I’m not sure quite what to make of the recurring song outside of the general observation that Charlie Brooker loves his Easter eggs. There are lots of funny little examples of cross-pollination between each of his episodes, even though they ostensibly take place in separate worlds, and though some episodes are set in the real world and some in very different dystopian futures. I, too, really enjoyed “Men Against Fire,” even though it was grim beyond belief. It told its story cleanly, explored real issues about augmented reality, and left a lot more to puzzle over in its aftermath. It might be my second favorite of the season.

“Hated in the Nation” is more similar to “Nosedive” for me. It’s a little too long (running 90 minutes), and it makes its point very repetitively, unfurling a plotline about social-media shaming where a Twitter witch hunt becomes a daily game of real-life death. What’s the main message? That the online hive mind condemns without thought of consequence, laying into targets with the same ferocity, whether they’ve committed crimes or simply made an offensive joke. How best to symbolize that? Killer robot bees flying into people’s brains, of course!

The metaphor was so obvious I almost respected it—especially because there’s a deeper message at work to “Hated in the Nation” about the growing surveillance state. The episode plays like an extra-long episode of The X-Files (down to the bees), crossed with a gloomy Nordic crime thriller. The wonderful Kelly Macdonald is Detective Karin Parke, a grumpy murder cop with the same grim demeanor as a character out of The Bridge or The Killing. Faye Marsay (recently the Waif on Game of Thrones) is her tech-savvy partner, one who quickly realizes that the murder they’re investigating of a much-despised newspaper columnist somehow relates to an online hate campaign. And, well, bees.

The procedural “cop show” helps mitigate the episode’s extreme length—it’s plotty enough to forgive the repetitive exposition about just how people tweeting #DeathTo was somehow leading to actual murders. Led by one vengeful soul angry at the online mob, the #DeathTo game is designed to make them feel the consequences of their actions. Whoever leads the hashtag tables at the end of a day dies rather horribly, as a mechanical bee flies up their nose and causes such unbearable pain that they’ll cut their own throats open to get it out.

The X-Files inspiration seems very clear in the bees—a recurring image through much of that show’s run, and a key element in the first X-Files feature film. In “Hated in the Nation,” the mecha-bees are a government project created to address the extinction of the real thing; these drones disperse pollen to keep our planet’s ecosystem alive. Of course, since they’re government-sponsored robots who fly all around the U.K., they’re also easily manipulated into misbehaving.

The episode is blunt, but its target is diffuse: Everyone’s a little culpable, and thus no one can be put on trial.

The bees are a fun stand-in for the insidious nature of state surveillance, a particularly prevalent concern in the U.K., a country blanketed with CCTV cameras. Throughout the episode, the fictional “National Police Force” uses all kinds of shady methods to track down suspects and potential victims of the evil bee swarm. That’s what I liked most about “Hated in the Nation”—the subtle ease with which civil rights are stepped around, to minimal protest within the government, simply because there’s a ticking clock to get ahead of.

Brooker has himself been at the end of an online backlash before, which he admitted inspired this episode. In 2004, he bemoaned the potential re-election of George W. Bush in a Guardian column, concluding his thoughts with “Lee Harvey Oswald, John Hinckley Jr.—where are you now that we need you?” Even in the U.K., where Bush and the Iraq War were tremendously unpopular, the remarks prompted a public outcry, and Brooker retracted the column and apologized.

But to Brooker’s credit, “Hated in the Nation” doesn’t just feel like a lecture about the evils of ganging up on people online. At the end of the episode, the #DeathTo phenomenon turns on its users, and the bees swarm against everyone who dared jump on the bandwagon; the punishment Brooker might have wished on his online detractors in his darkest moments is taken to a logical extreme, and the result is horrifying. “Hated in the Nation” is blunt, but its target is diffuse: Everyone’s somewhat culpable, and thus no one can be put on trial, which is just how these social media mobs function. It’s a depressing note to end Black Mirror on, but a fitting one—a caution to its audience to never feel too high and mighty about your conduct online. The bees might be coming for you next.

Westworld and VR Gaming: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

The Meta-Politics of Westworld

Emily Nussbaum | The New Yorker

“Self-cannibalism and the snake that eats its own tail: That’s a fair description of Westworld, a come-hither drama that introduces itself as a science-fiction thriller about cyborgs who become self-aware, then reveals its true identity as what happens when an HBO drama struggles to do the same.”

Translation as a Practice of Acceptance

Anita Raja | Asymptote

“A text tethers readers tightly within its web, even if, when we read a book we love, it is difficult to tell where we end and the characters begin, where we submit to the author’s will and where we impose our own. To translate is to accept this inequality, to see the text clearly, and to willingly let ourselves be trapped in its web.”

Paintings of a Homegrown Black Superhero

Sarah Rose Sharp | Hyperallergic

“It’s a bit of a sticky moment for emotional realism. The politics of this election cycle—and, increasingly, global politics in general—seem geared toward amassing social capital and influence through the exploitation of lies that ‘feel’ true. But it’s striking that the highly subjective interpretations of relations between police and citizens of color, as laid out in Williams’s bold and colorful tableaus, feel representative of a facet of reality that is increasingly validated by social and mainstream media, after centuries of going largely unrecognized.”

Michael Moore’s Limp Stand

K. Austin Collins | The Ringer

“You almost miss the crazies. It’s a movie called Michael Moore in TrumpLand — where are the pitchforks? There’s no danger here. Perhaps because of that, Moore performs free of the nervousness or tension that might have made the project contentious or brave, or which might have made his low-hanging satirical jabs more risky and discomforting.”

Strangely Enough

Teju Cole | The New York Times Magazine

“The surreal image caught on the fly can remind us of our vulnerability much more powerfully than manipulated photographs can. A double exposure that gives a man two heads is too definite, like something from a horror film. Its heavy-handed ‘surrealism’ robs it of pathos. But a protuberance on the trunk of a tree, or a chair with a missing leg, or a twisted metal railing in the midday sun, being more ambiguous, can be more surreal.”

How Game Makers Are Struggling to Make VR Fun

Chris Baker | Rolling Stone

“Simply moving around in VR presents even more conundrums. If your eyes and ears tell you that you are racing across a scorched field in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, but your other senses tell you that you are kicking back on the couch in your living room, it can undermine the illusion. Or worse—it can lead to motion sickness.”

The Truth About Photoshop Shame

Aimee Cliff | The Fader

“Rather than liberating women, intensely scrutinizing their images for Photoshop use has become just another way we can police them. It also doesn’t take into account the fact that women may use tech trickery as an artistic tool.”

The Second Coming of South Park

Eric Thurm | GQ

“Even at its sharpest, South Park won’t enjoy the level of influence it had in its less mature days; it’s never going to be ‘relevant’ or ‘important’ again, but that's probably for the best. Many of the series’ worst moments have stemmed from a heightened sense of moral superiority masquerading as cynical detachment, a commitment to the idea that everyone with skin in the game is an idiot rather than just a person fumbling around trying to do the right thing.”

Black Mirror’s ‘Men Against Fire’ Tackles High-Tech Warfare

Sophie Gilbert and David Sims will be discussing the new season of Netflix’s Black Mirror, considering alternate episodes. The reviews contain spoilers; don’t read further than you’ve watched. See all of their coverage here.

What a relief “San Junipero” was after the actually nightmare-provoking “Shut Up and Dance.” (I really did have a dream about a bugged bottle of wine that was sending videos to Russian hackers, because that’s just the kind of week it’s been.) It isn’t often Black Mirror takes such a heartwarming, optimistic view of things, although naturally the episode had sharp undertones about the dangers of perpetual pleasure seeking (the Quagmire was as apt a portrait of the dark underbelly of the internet as you’ll ever find) and the allure of nostalgia.

I loved the narrative freedom offered by a new location, though, and now that we’re almost through all six episodes, I wanted to take a minute to think about how season three of Black Mirror has been different. The shift to Netflix from the U.K.’s Channel 4 has opened the show up to different locations, yes, but also different environments. In its first two seasons the show seemed to be set in Britain—even the more unrecognizable worlds of “15 Million Merits” and “White Christmas.” But in expanding its geographical horizons, Black Mirror is also able to expand its scope with storytelling, exploring themes that might not have made sense before. Like falling in love. And going to war.

“Men Against Fire” is one of the better episodes of the series, I think, because it actually featured a sharp twist with a message, and one that wasn’t as obvious as the show’s usual sermons (technology: bad, mob mentality: bad, brain implants: v. v. bad). Stripe (Malachi Kirby) is a soldier fighting in what appears to be Eastern Europe, only the enemy forces he’s targeting are zombie-like mutants known as “roaches.” After a band of roaches raid a nearby village in search of food, the American soldiers pay a visit to a local eccentric who’s believed to be helping the mutants out of a belief that all life is sacred. Searching through some hidden rooms in his house, Stripe encounters several aggressive roaches and kills two, but not before one of them shines a mysterious light in his face that causes his brain implant, or “mass” (a device that allows his commanding officer to transfer visual information to him instantaneously), to start acting peculiarly.

After the ringing in his head affects his performance at a shooting range, Stripe reports to medical, and is sent to a unit psychiatrist (Michael Kelly), who quizzes him on what it felt like to kill the roaches, and how he’s coping. The next day, while infiltrating a roach compound, Stripe is shocked when he sees his fellow soldiers murdering civilians, all of whom seem to be pleading for their lives. He helps a woman escape with her young son, and learns the truth: the implant in his head causes him to see ordinary people as gruesome mutants, and to interpret their peaceable actions as violent ones that threaten his life.

It’s a terrific, unexpected twist, mostly because it seems so plausible: What could be more enticing to an advanced military power than a device that allows soldiers to kill without suffering any guilt or emotional repercussions? In a horrifying conversation in Stripe’s cell after he’s recaptured, the psychiatrist reveals that the technology was pioneered because humans are “genuinely empathetic as a species. We don’t want to kill each other, which is a good thing, until your future depends on wiping out the enemy.” The blood sickness the soldiers were taught to believe was the reason for eliminating the roaches is actually their genetic differentiation, the doctor explains: higher rates of cancer and muscular dystrophy, substandard IQ, higher criminal tendencies and sexual deviance.

The episode made me think about augmented reality, and the ethical boundaries that don’t exist when it comes to showing people things that aren’t there.

With this unexpected lurch toward the subject of eugenics, “Man Against Fire” alludes to a wealth of different prejudices still rife among humankind, particularly institutionalized racism, tribalism, and fear of refugees (the villagers don’t see the roaches as other, it’s worth noting—they’ve simply been taught to see them that way). And it veers into darker territory still toward the end, when Stripe is adamant he doesn’t want his mass reset, and the doctor informs him that if he refuses, he’ll be forced to relive his murder of the two “roaches” on a permanent loop via the implant while he sits in a jail cell. It’s the kind of particularly inconceivable psychological torture Black Mirror likes to throw out once in a while, like being stuck in a log cabin alone listening to Christmas music for what feels like several million years. And it persuades Stripe: At the end of the episode, he’s shown returning home in uniform to a ramshackle house and a woman who most likely is an illusion created by his device.

The episode made me think about augmented reality, and the ethical boundaries that don’t yet exist when it comes to showing people things that aren’t there. It was also a persuasive and nuanced exploration of military valor, and the potential might of an army that could fight without morality getting in the way. But it also seemed to point toward the drone technology that exists now, and how much easier it makes eliminating large groups of people remotely at the flick of a switch, without the smell or the sound of warfare. Without the implant, the doctor tells Stripe, “you will see and smell and feel it all. Is that what you want?”

Praise to Malachi Kirby, fresh off his performance in the Roots remake, who was similarly stellar in this, and to Kelly, who always imbues every performance with extraordinary menace. What did you make of it, David? Should we note that when Stripe’s fellow soldier sang “Anyone Who Knows What Love Is (Will Understand),” that’s the third time this fairly obscure track has been featured in the series? What’s up with that?

Read David Sims’s review of the final episode, “Hated in the Nation.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower