Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 56

October 18, 2016

When Novels Frustrate, and Enthrall

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

When the novelist Jonathan Lethem discovered Kafka’s The Castle, as a bookish high-school kid in the late ’70s, his initial response was obsession—followed by rage. At first, the novel’s sudden ending seemed like sacrilege. But Kafka’s narratives of thwarted progress became a major influence on Lethem’s own fiction, as he explained in a conversation for this series.

In particular, Lethem pointed to Kafka’s leopards in the temple, a three-line parable about unruly cats who become central to a ritual they once disrupted. For Lethem, the piece is small but immensely meaningful: In a handful of lines, it offers rich insights into the nature of artistic influence, the novel’s role in culture, and the value of facing private shame on the page.

Lethem’s latest novel, A Gambler’s Anatomy, begins in Germany, where an aging backgammon hustler named Bruno develops an alarming affliction: a black spot slides across his vision, partially blinding him. (He calls it the “blot,” which, we learn, is also slang for an unprotected checker.) Parceled out in 36 short chapters—the number of possible outcomes from a pair of tossed dice—the book follows Bruno from Berlin toward a potential cure in Berkeley. It emerges that Bruno regaining his sight will mean giving up other, deeper facets of himself.

Lethem is the bestselling author of two story collections, two essay collections, and nine other novels, including Motherless Brooklyn, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. A MacArthur Fellow, his writing has appeared in magazines including The New Yorker and Harper’s; his critical prefaces introduce works by writers like Philip K. Dick, Shirley Jackson, G.K. Chesterton, and Nathanael West. He spoke to me by phone.

Jonathan Lethem: When I first read Kafka’s The Castle, I think I was fifteen. The copy I had was an old Shocken hardcover edition I found in the library of my high school, Music and Art—New York City’s public school for musicians and visual art students. I was a denizen of the Music and Art library, which was not a very lively joint at that point. It was full of incredible hardcovers of all kinds, many of them mouldering. At the same time, I was also going to lots of used bookstores all over the city, which, back then, was still filled with them. Rent was so cheap that these eccentric, clubhouse sort of used bookstores proliferated: whole rooms full of books, manned by some old bookseller who wasn’t trying very hard and scared away half his customers with his crankiness.

I was right in the middle of a phase where I just wanted to read as many novels of as many kinds as I could. I had no compass. I was just trying to read everything, and I was hot on the trail of Kafka. I’d been reading science fiction, and I’d already discovered Borges, and in a certain way I associated Kafka with these things—I’d gotten the hint that if I liked morbid, fantastical things, gothic stuff, that he might work for me. So I read The Castle, read it fast and in a fury, to find out what happened at the end. I took it as a given that every book was headed somewhere, and obviously this book was headed to the castle. There was going to be a great, grand finale up there—because what book called The Castle wouldn’t have some incredible culmination up in the castle? As I read, it was total cathexis. I was with K., every inch of every paragraph, waiting for revelation. And when the story falls off the cliff at the end, I was enraged. I wanted my money back. (Except I hadn’t spent any money.) I couldn’t believe there could be a famous book that was so radically unsatisfying. I remember thinking, how can he even be a famous author if he fucks you over this badly? It just seemed like a disaster.

And then—at some point not shortly after this violent sensation of having been misused by the book—I guess I wanted more. I needed to be in that headspace again. So I read The Trial.

The Trial was one of the key reading experiences of my teenage years. It made me a writer; it made me who I am. And if I never encountered another book by Kafka—if I hadn’t then gone on to learn about the short stories, and the aphorisms, and the diaries, and the letter to his father, all of which I eventually devoured in my twenties—even if there were only The Trial, and The Castle lurking there in the background, I would have talked about Kafka as one of my favorite writers for the rest of my life anyway. I was just his.

But the other part of my incredibly deliberate program was that, if I liked a writer, I had to read every word. (I’d already done it with Graham Greene, Shirley Jackson, and Philip K. Dick.) I didn’t necessarily do it right away—of course, sometimes I couldn’t even find all the titles right away. But I knew I would exhaust their shelf. I think I was probably done with everything I could find of Kafka’s by the middle of my twenties. I would have encountered the leopards aphorism around then.

Leopards break into the temple and drink to the dregs what is in the sacrificial pitchers; this is repeated over and over again; finally it can be calculated in advance, and it becomes a part of the ceremony.

It would have been one of the last things of his I read, just because of my nature as a reader. I dig narrative. I wouldn’t have been shopping for aphorisms, which have nothing to do with what brought me to literature in the first place. I was a very literal reader. I wanted stories with characters, lots of occurrences and situations. That’s what I was reading for, and how Kafka first netted me: with this extreme, perverse, but very compulsive narrative. Borges writes about Kafka in a way that turns the Greek philosopher Xeno into his precursor, because Kafka’s narrative is all based on Xeno’s paradox: the idea that you’re always closing half the distance to your target, but you never fully arrive. It’s a consummately frustrated form of narrative progress, but it is one, and it has a labyrinthine, compulsive, hypnotic quality to it. That narrative quality is what gets me in a position to become a reader of Kafka’s language and someone who identifies with his philosophical implications (though it’s hard to say just what those are). It begins with story.

The novel is always gobbling up the language of the street.

In its way, the leopards in the temple is a tiny little story. There’s a violent and exciting plot that takes place over a certain amount of time. But one of the things that's entrancing is: well, how long does it take to incorporate the leopards into the ceremony? Did it take hundreds of years of civilization to incorporate the leopards our forefathers once bemoaned? Or is it—well, last Wednesday we thought it was a problem but this week we decided to work around it? However long the span of time is, there’s a sort of intensely embedded kind of narrative situation with characters who make a decision to resolve a kind of conflict in favor of incorporating chaos into their worldview.

But it also it looks to me like an M.C. Escher drawing, which is another thing I thought was extremely cool when I was 15 years old. In some oblique way, this topological quality is still what I respond to in Kafka. The leopards are a piece of the outside that ultimately fit on the inside. Somehow, they complete a shape that initially seems like it's meant to be a negative space, but actually the negative space becomes essential to the completion of the positive space. The temples and the chalices are like the drawing that Escher would render in lighter colors with cutout shapes of negative space that you begin to see look like a leopard, and then you realize: wait a minute, the leopard is the drawing. There's a yin-yang quality to it, the way these two things become interdependent spatially.

To me, the leopards in the chapel are a beautiful allegory of high and low culture. I wear on my sleeve a definition of the literary project of the novel: its signature is the incorporation of the demotic. The novel is always gobbling up the language of the street and of commerce and of popular culture—in fact, it's driven by the need to replenish itself by what might seem at first to be its nemeses. People are always wanting to put the novel on a pedestal and make it a kind of exalted art form, as if it's a Mark Rothko painting in a chapel, or a Beethoven symphony. They want it to be a purified high form, which is a meaningful desire, because when novels change your life they make you feel exalted. But in fact novels are just organically made of the rabble of the everyday. You can't purify them. You can't extract the demotic material. So you could take the leopards and the chalices as a symbol of the novelist's impure position—as a negotiator of high impulses and low sources.

Pretty much every generation of fiction writers has to find a way to invite in the leopards: the stuff that’s objectionable to the older generations. When I started incorporating so much of the stuff of the vernacular culture and commercial that excited me—advertising, comic books, genre, pulp, rock and roll—even I thought I was, in some way, fouling the nest. But I couldn't keep from doing it. And then I began to become defiant about that project. I thought, wait a minute, that's what Dickens did. And I incorporated it into the ceremony.

You could also read the aphorism as about the folly of trying to protect yourself—as a person, or as an artist—from the things that frighten and threaten you. Because what a boring ceremony without the leopards, right? Who wants to see the ceremony without the leopards, once you know that they might come? I was saying this to students last night in a fiction workshop: The impulse to make the ritual safe, to put characters in play who are ultimately admirable and can be redeemed, is extremely boring and also suspect. There's something that you're protecting yourself from—and why bother? Damage is in the mix, and it should be. What was the ceremony for before the leopards came along? It was probably for hoping the leopards wouldn't come along. But you don't really want it to succeed. Your damage and your dismay are the best things you’ve got going, and you've got to open yourself to it.

The animal is an uncrackable code, and yet carries a message that we have to abide in some way.

I learned that, in a way, by writing my two Brooklyn books—Motherless Brooklyn and Fortress of Solitude—which manage the anxiety and the trauma associated with where I was from. I took my most turbulent and confused feelings about that, my defiance and pride and embarrassment, as well as proprietary feeling that I could never justify, especially since I'd run fast and far away from the scene. So what was it that I was entitled to claim as my own? But I opened that door—and I did it accidentally, in a way—by introducing Brooklyn into this cute, clever postulate I'd come up with about a detective with Tourette's Syndrome. It needn't have been a Brooklyn book, and I hadn't ever written one before. But by putting him in that environment, I found myself tapping those anxieties, and in that book I managed them pretty completely. That was how I announced to myself that the leopards really needed to drink the chalices.

Fortress of Solitude is where I let the leopards in. Ever since, for me, disappointment and embarrassment are among my most vivid subjects. (And I might say that disappointment and embarrassment are primary in Kafka as well.) One of the things that happens in the aphorism is that the chalices are drained, which again raises the question of: who was supposed to drink it originally? And if it was just going to waste, what were you saving it for? It's a partly a parable about this foolish notion that you have anything to protect in the first place.

Despite all these symbolic and metaphorical layers, I love that the aphorism features real animals. It’s not ghosts. It’s not gargoyles, or a golem. They’re leopards—and this isn’t inconsequential. That’s something that connects to a curiosity of mine, one I had never articulated until recently, that probably starts with Alice in Wonderland, which is the first book I fell in love with at age 11, and was really my doorway out of children’s books and into literature. It was also there in Jack London, and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, some of the books that meant the most to me shortly thereafter: this presence of the real animal as a mystery or rebuke or cipher for the human to contemplate. The animal is an uncrackable code, and yet carries a message that we have to abide in some way.

I was slow to notice how much animals meant to me as a literary emblem. Of course my first novel, Gun with Occasional Music, is full of talking animals. (It’s very much a hardboiled detective/Alice in Wonderland mashup.) And then, in Chronic City, the presence of this tiger in New York City seems to have some kind of leopards-in-the-temple kind of message: the creature making all of these intrusions on the life of the city. He represents a message no one can translate. Almost my favorite Kafka of all is "The Burrow,” with this mole-like creature, whom the narration totally transubstantiates. He becomes the mind of the writer lurking in a tunnel, both inside and outside of life, underground and terrified to come out, and at the same time guarding some cavern of incredible, indefinable value. Kafka’s also got the ape in “Report to the Academy”, and “Investigations of a Dog,” and then the cockroach in Metamorphosis. Kafka was an animal writer. Against all odds. He was an animal writer like Jack London or Thornton Burgess. It’s the compulsion of an urban mind towards what's been pushed to the periphery, to what's lurking at the farthest edge. I don't think it’s a projection to say the leopards here are part of the world of our animal cohort, whose indifference or hostility we're permanently excluded from—but feel we must understand, because it must hold some key to ourselves.

All this, in these three short lines. It’s the kind of thing that sounds almost biblical, once you read it. How could this belong to one writer? That’s true of a number of Kafka’s aphorisms—they seem somehow emblematic of consciousness itself, and they just carve themselves into the human source code. I don’t have a feeling of first reading this. I have a feeling of having always known it.

October 17, 2016

Sympathy for the Melania

As more women come forward with allegations of harassment against Donald Trump, more scrutiny is also being directed toward the women who are still standing with him. Female ally No. 1 is Trump’s wife, Melania, and even though she’s remained relatively quiet throughout the presidential campaign, her cultural footprint seems to be growing. The caricature that’s arisen is both empathetic and insulting, rooted in horror at what Trump represents but also in stereotypes about trophy wives and Eastern European women and beautiful people being vacant.

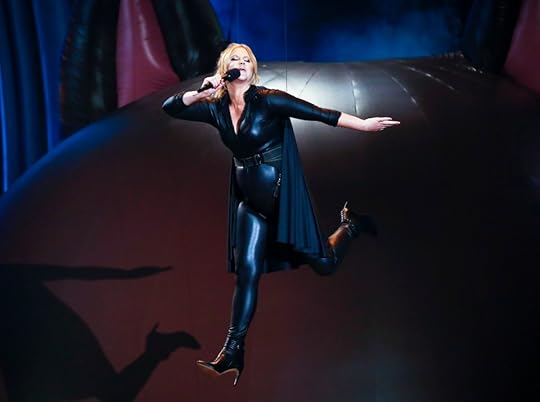

Melania has been among the more reserved political spouses in recent memory, making only sporadic campaign appearances with speeches notably lacking in specific details. Her most famous moment so far was plagiarizing Michelle Obama in her speech at the Republican National Convention—a gaffe that only accentuated the feeling of blankness at the heart of her image. And so the first round of satire directed at Melania was about this blankness, as with Laura Benanti’s impersonation on Colbert or Super Deluxe’s sublime stump-speech remix, which suggested she’s a robot or hypnosis victim.

The second kind of satire, though, has tried to go deeper, taking the blank slate and filling it with speculation about Melania’s inner life. The author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‘s New York Times fiction piece about the Trump family took on this task. (“Donald admired in his daughter qualities he would not abide in a wife. Not that Melania minded, she told herself, watching them.”) So have Saturday Night Live’s recent portrayals.

In the NBC show’s ongoing Melania Moments segments, SNL imagines the potential next first lady as the subject of a new-agey VHS vignette, the kind of format that the show’s Jack Handey bits sent up in the ‘90s. This past weekend, Cecily Strong’s Melania gazed at her housemaid and imagined trading places with her, The Prince and the Pauper-style. “She thought, ‘I could go out into the world,’” the narrator said. “‘See a bus. See a hill. Or even feel the texture of sand. She’d stay here and lay under Donald. Not a fair trade, but oh how I’d love to touch sand.’”

The two previous Moments have also made Melania out to be a luxurious captive, isolated from the world, deeply and passively unhappy. In the first such skit, Melania looked down from the Trump Tower and wondered about the world below (“Is there a Sixth Avenue?”). In the second, she sensed her “replacement” being born in rural Latvia. “I must find this girl and vanish her to the woods, she thought to herself,” the narrator said. “Not for my sake, but for hers.”

SNL’s version of Melania also starred in this week’s Melanianade sketch, which reimagined Beyoncé’s “Sorry”—a kiss-off to a reckless husband—as coming from the women in Donald Trump’s life. In it, Melania, Ivanka, Tiffany, Kellyanne Conway, and Omarosa sang about being fed up: “Without us you wouldn’t be standing there / You’d just be that guy with the weird hair.” At one point, Melania took a baseball bat to a TV showing news about sexual-misconduct allegations against Donald. But at the end, Alec Baldwin’s Donald showed up and gave the women orders—and they obeyed. Melania’s rebellion was just a lark.

Real-life photo shoots of Melania forking up jewels as if they’re spaghetti, and quotes about striving to serve her husband without “nagging” him, have certainly contributed to this characterization. But the actual Melania probably deserves more credit for making her own choices. She’s often described the way she met Trump with an anecdote that emphasizes her agency: At a Fashion Week party in 1998, Donald reportedly asked for her number but she insisted that he be the one to give her his contact info. But a different origin story has been following her around, in which it’s falsely implied she was basically a mail-order bride. Here’s Strong’s Melania in an SNL sketch from a year ago: “I was in Slovenia and Donald saw a picture of me in magazine and he called me and he said, ‘Hey, come to America.’”

A fiction like that allows for an image of powerlessness, servitude, and pure transaction. SNL’s ongoing joke plays on both sides of the line between sympathy and mockery, expressing awareness of the underlying human being but also showing distain rooted in the assumption she’s not in charge of her own life. It’s a projection resulting from being unable to believe that someone could happily stay married to someone like Donald Trump.

Which is understandable, given what’s transpired in this campaign. But this mix of sympathy and sneering also reflects, at base level, the culture war over gender roles. At a Tidal concert over the weekend, Nicki Minaj went on a riff about White House women, praising Hillary and Michelle Obama before saying, “You better pray to God you don’t get stuck with a motherfucking Melania. You niggas want brainless bitches? To stroke your motherfucking egos? Well, fuck you.” On Twitter, she later denied she’d been “dragging” Melania, writing “She seems nice. But a smart man knows he needs a certain ‘kind’ of woman when running for President/attempting greatness.” It’s hard still not to read that clarification as another diss against Melania—and moreover, against other women of her “kind.”

The Easy Political Escapism of Graves

Richard Graves, the subject of the new Epix comedy Graves, is such a pitch-perfect stereotype of a former Republican president that the show veers close to parody. Played by a particularly craggy Nick Nolte, he whiles away his days on a ranch, growling at his staff in a coarse, gravelly voice. He attends ribbon-cutting ceremonies and delivers vague platitudes, and is treated like an fossil for party loyalists to gawp at rather than listen to. But in the show’s hokey pilot episode, Graves shakes himself out of this reverie and starts expressing guilt over his legacy as a tax-cutting, warmongering, anti-gay rights leader of the country. It becomes clear that this is going to be a show about empathy in politics—which means at times it feels like a total fantasy.

Graves, part of the premium channel Epix’s play for prestige viewers in a saturated landscape, has hit screens at a particularly bizarre time—it feels simultaneously very topical and hopelessly out of sync with the current political moment. Graves seems to stand in for the establishment legacy of the Reagan/Bush Republican era, one that’s being largely ignored by the party’s current presidential candidate. Given the vagaries of TV development, it’s most likely a coincidence that Graves, a suddenly compassionate conservative, is showing up just as Donald Trump is in the grip of his historic real-life meltdown. But the comparison is hard to ignore, and Graves feels like the latest and most obvious piece of political wish fulfillment in what’s become a growing genre. Graves is a politician who’s suddenly struck with an overwhelming sense of principle and accountability—concepts that seem largely absent from this election.

The show feels especially ironic in this moment given that it features a guest appearance from former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who’s become one of the Trump campaign’s liveliest and most controversial mouthpieces. Here, Giuliani’s presented in the spirit of bipartisanship, shown accompanying Graves to a ceremonial event with the former New Mexico Governor (and Democrat) Bill Richardson and assuring Graves that he should be proud of his legacy. Graves is “the very model of what a former president should be—a statesman,” Giuliani intones while introducing him at a rally, which feels hilarious in the context of some of the former mayor’s more recent actions.

Graves, though, is sick of being a statesman, and the crucial moment in the pilot episode comes when he Googles his name and considers his legacy, reading criticism about his positions on oil drilling, border politics, civil rights, funding schools, and tax cuts with tears in his eyes. Later, he visits his presidential library and breaks down inside a memorial dedicated to a war he initiated, saying the soldiers he sent overseas “were just kids.” It’s obvious stuff, and it’s mixed in with scenes that are played strictly for laughs, like Graves developing an appetite for marijuana, or harassing his pipsqueak of an assistant by drawing epithets on his face with a pen.

The overall purpose of the show feels like wish fulfillment. The show’s creator, Joshua Michael Stern, seems to crave straight talk—he made a whole movie, 2008’s Swing Vote, that was geared towards wringing the truth from politicians. Wouldn’t it be interesting, Graves asks, if George W. Bush all of a sudden, started acknowledging his critics and contending with his unpopular legacy as president? In a grander sense, wouldn’t it be something if politicians could admit to feeling guilt, or shame, or regret—something that rarely happens when they’re in office, and almost as rarely when they’re out of it? It feels part of a larger phenomenon where some political TV is no longer trying to reflect what’s happening in office, but instead reshape government into a more palatable fantasy.

Shows like House of Cards, Scandal, and Veep are shot through with negativity about the country’s current state. But newer entries like Designated Survivor feel like pie-in-the-sky fantasies of drastic change—what if our current system was reduced to rubble and rebuilt from the ground up by an apolitical guy from outside the Beltway? In Graves, the ex-president acknowledges at a cancer research event that politicians are reticent to fund research for deadly diseases because they won’t win over many voters.

Stern is playing in a very simplified fantasyland, though. In Swing Vote, a bizarre electoral situation places a presidential race in the hands of one man (played by Kevin Costner). That film mocked the cynical speed with which politicians will change their views to encourage voters, and featured a fairytale ending where such craven behavior was finally set aside for the good of the nation. Graves is a similarly broad, goofy salve for a dark, polarized moment in electoral politics. But its escapism feels too simplified, and Graves’s awakening feels too easy, for the show to make the impact it so badly wants to.

Amy Schumer: The Comical Is Political

“The show became political,” Ryan Atwood explained of his dissatisfaction with Amy Schumer’s Sunday-night show in Tampa, Florida, after some 200 members of the show’s audience walked out in protest of jokes she made about Donald Trump. “I don’t want to hear that,” said Bryon Infinger, who added that “we wanted to have a good night without distractions with the politics.” Bryon’s wife, Chrissy, agreed: “It’s a bit much,” she said.

It’s unclear, though, why the people who left the show were surprised by its slant. Schumer has never been a “what’s up with airplane mirrors?” kind of comedian; her jokes, even when they haven’t been expressly partisan, have almost always been intensely political. Schumer’s work has vilified rape culture and endorsed gun safety and celebrated a woman’s right to choose the fate of her own body. Her jokes, whether they’ve appeared in her stand-up sets or on her Emmy-winning TV show or in her feature film or in her recent memoir, have revolved around the broad question of the interplay between the collective culture and the individual. They have taken for granted that age-old feminist rallying cry, a cry that only grows more broadly relevant: “The personal is political.”

This wasn’t an intimate Comedy Store situation. It was Amy Schumer, bona fide superstar, performing to a crowd whose size fit that stature.

Sunday’s problem seems to have started, as problems so often will, with Trump jokes. In her set, Schumer referred to the GOP presidential contender as an “orange, sexual-assaulting, fake-college-starting monster.” According to the review of the show from Jay Cridlin, the Tampa Bay Times’s pop-music and culture critic, things went like this:

Schumer scanned the crowd for Trump voters, and invited one up to the stage. He identified himself as Dave, an attorney and RINO (Republican In Name Only) who hadn’t voted for a GOP candidate since Reagan. He said he just felt safer with the country in Trump’s hands than Clinton’s.

“Do you get worried at all with how impulsive he is,” Schumer asked, frustration in her voice, “that he gets so fired up from Saturday Night Live doing a skit on him … do you worry he’ll be impulsive and get us in a lot of f---ing trouble we can’t get out of?”

At this, people booed. They also booed when Schumer proclaimed that she would be voting—and actively working for the election—of Hillary Clinton. This, again, was no surprise: Not only has Schumer proclaimed her affinity for Clinton on every social-media platform available to her, but she also spent time right before Sunday’s show outside Tampa’s Amalie Arena, registering voters to take advantage of Florida’s voter-registration extension.

But: “Of course, we’re in Florida, you’re going to boo,” Schumer said, in reply to the audible push-back on her comments.

She added: “I know you’re here to laugh, but you choose how you’re going to live your life, and it’s just too important.”

She further added: “Just so you know, from now on, if you yell out, you’re gonna get thrown out.”

And so: People left. They left, it seems, because they were looking for a respite from the sour debates of the current moment; they left, it also seems, because Things Got Political. As Cridlin noted of Schumer’s skewering of Dave the RINO, “This was risky business for a comic. This wasn’t some fun roast, where the fan was hoping to be ripped a new one.”

Related Story

How Comedians Became Public Intellectuals

It’s true. And it’s particularly true given that this was a huge arena show—set, either ironically or fittingly, in the same massive theater that hosted, in 2012, the Republican National Convention. This wasn’t an intimate Comedy Store situation. It was Amy Schumer, bona fide superstar, performing to a crowd whose size fit that stature.

Then again: Ostensibly, if you’ve paid your hard-earned money to attend an Amy Schumer show, it seems reasonable that you would have some sense of what Amy Schumer is all about. Recent episodes of Inside Amy Schumer have, again, tackled gun safety, abortion, rape culture, and many other topics that are, whatever else they might be, intensely partisan. But it’s not just Schumer’s jokes that have been political; it’s Amy Schumer, the person. Schumer has long used her celebrity to advance “political” causes. She has lobbied Congress alongside her distant cousin, Chuck Schumer. With her comedy, it’s almost impossible to distinguish where the political ends and the personal begins.

Schumer’s set acknowledged that the personal and the political cannot be neatly separated from each other.

Schumer is not at all unique in that. Indeed, it’s hard to think of any popular comedy of the moment that is apolitical, or even simply non-partisan, in the way Schumer’s Tampa detractors seem to have hoped for. Whether it’s Louis C.K. or Sarah Silverman or Whitney Cummings or Key & Peele or Poehler & Fey or Patton Oswalt or Sam Bee or Leslie Jones or Ali Wong or Trevor Noah or John Oliver or any of the other comics who are ascendant at the moment, their work is almost uniformly political. That is what makes it relevant, and urgent, and worth talking about. Comedy now is operating in the tradition established by George Carlin and Joan Rivers and Richard Pryor and other greats—performers who understood comedy’s great capacity not just to make us laugh, but to make us think. And re-think. And act. The kind of apolitical comedy that Schumer’s walk-outs seem to long for may have last been realized by Gallagher; he achieved that by largely eschewing words in favor of the cathartic smashing of watermelons.

Gallagher got name-checked, fittingly, during Schumer’s Sunday set: “The first four rows, you are going to see my entire vagina,” she said of her miniskirt. “It’s like a Gallagher show.” But then, just as fittingly, he got dismissed in favor of jokes that recognized that some moments—when so many things are at stake—call for more than mallets. Schumer’s set, ultimately, did what most comedy will, nowadays: It grappled with the tangled connection between the body politic and the individual body. It acknowledged that the personal and the political cannot be neatly separated from each other.

Which is also to say that it recognized what the founders assumed to be true: Politics isn’t, and has never been, just about government. Americans tend to talk about “politics” as if it were its own taxonomic category; the truth, though, is that politics infuses the personal and the cultural and the everyday and the intimate. That is why Beyoncé urges us to “get in Formation”; it’s why celebrities so often get into retail politics; it’s also why nobody should be surprised when Amy Schumer gets up onstage and uses her own platform to make a political point. Donald Trump’s accumulated statements, whether they insult Mexicans or Muslims or African-Americans or the disabled or the female or the human, are repugnant not just because they seem to suggest a desire for despotism, but because they use the intimacies of politics against themselves. They assume that politics is about bodies, but also that some bodies owe more than others do. Schumer was simply acknowledging all that—using not a speech or a statement or some other, more traditional method of “political” discourse, but one that is now just as powerful: comedy.

How 'Unprecedented' Are Trump's Claims of a Rigged Election?

Donald Trump spent much of the last few days insisting that the presidential election is rigged. The press, in turn, spent the same days warning darkly that Trump’s statements could gravely undermine faith in American democracy, even if—especially if—he loses in November. Many news stories quoted Republican officials dismayed by Trump’s comments.

Somehow, that did not dissuade Trump, who started the day off with another piquant, and more specific claim:

Of course there is large scale voter fraud happening on and before election day. Why do Republican leaders deny what is going on? So naive!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 17, 2016

Trump’s claim, you will be surprised to find out, is unsupported. (Later in the morning, Trump retweeted a story from Alex Jones’ 9/11 Truther site, InfoWars.)

Cases of voter fraud certainly exist. But by and large, they are not the sorts of lawbreaking that the public imagines, nor are they on the scale proposed. Some, as my colleague Yoni Appelbaum wrote Sunday, involve things like poll workers futzing with numbers around the margins. Cases of invalid registration are fairly common. Not a cycle goes by without a splashy story about someone registering his or her dog to vote, only to be deluged with campaign mailers from candidates.

But these registrations seldom produce actual fraudulent votes, for the obvious reason that no poll worker is going to let Fido go into the booth. Dead voters are also often on voter rolls, but evidence of people fraudulently voting on behalf of the deceased is also rare.

In 2007, Loyola University Law Professor Justin Levitt produced a comprehensive report about fraud and concluded:

Allegations of widespread voter fraud, however, often prove greatly exaggerated. It is easy to grab headlines with a lurid claim (“Tens of thousands may be voting illegally!”); the follow-up—when any exists—is not usually deemed newsworthy. Yet on closer examination, many of the claims of voter fraud amount to a great deal of smoke without much fire. The allegations simply do not pan out.

One common rejoinder from those who believe voter fraud is a widespread problem is that such studies only show that few people are being caught for fraud. Given the cottage industry around fraud, though, one would expect widespread voter fraud to show up, which it does not. The few examples that exist tend to be sting operations like James O’Keefe’s. Others fall back on largely illusive arguments like the New Black Panther Party, a case I detailed here. Trump himself has offered no evidence to back his claim.

Trump’s claims, and those of allies like Rudy Giuliani, are the real fraud—baseless, and deleterious to democracy, because they undermine faith in the legitimacy of the political process. Just ask Ohio Secretary of State Jon Husted, a Republican who on Monday blasted Trump for “irresponsible” rhetoric.

“I can reassure Donald Trump: I am in charge of elections in Ohio, and they're not going to be rigged. I'll make sure of that,” he said. “Our institutions, like our election system is one of the bedrocks of American democracy. We should not question it or the legitimacy of it. It works very well. In places like Ohio, we make it easy to vote and hard to cheat.”

But the rhetoric is working. Four in 10 respondents in a new Politico/Morning Consult poll said they believed the election could be “stolen” from Trump, including three-quarters of Republicans.

The all-out attack on the legitimacy of American elections is being described as “unprecedented.” The New York Times quoted historian Douglas Brinkley saying that it represented the single greatest instance of delegitimizing government since the eve of the Civil War. How accurate is that, really?

Conservatives, including those not supporting Trump, have reacted with a raised eyebrow and suspicion of cynicism. What about the 2004 election, for example? In December, The New Yorker’s David Remnick reported that John Kerry suspected fraud had cost him the election:

In 2004, when Kerry lost the Presidential race to George W. Bush, who is widely considered the worst President of the modern era, he refused to challenge the results, despite his suspicion that in certain states, particularly Ohio, where the Electoral College count hinged, proxies for Bush had rigged many voting machines.

A lengthy Rolling Stone piece by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in 2006 also argued the election had been stolen. Rumors of conspiracy were rife before the election, too, with arguments that Diebold, a major manufacturer of voting systems whose CEO was a GOP donor, would throw the election. In July 2004, 21 percent of Americans were not all that confident about election systems; by mid-October, that was up to 27 percent.

These claims are both pernicious and different from what Trump said. First, they came well after the election, rather than being rolled out ahead of time to preemptively guarantee that many voters will reject an election’s results; after all, Remnick notes that Kerry suffered his conspiracy theories in silence, conceding publicly the morning after the 2004 election, before Bush declared victory.

Trump, by contrast, has been darkly hinting that he might not concede if he loses on November 8. (His running mate Mike Pence said on CBS, “We’ll respect the outcome of this election,” putting him somewhat at odds with the other half of the ticket.) Some of Trump’s supporters warn of rebellion in the event of a Clinton victory. It’s unclear whether this view is widespread, but even the open discussion is concerning: Peaceful transfer of power is a key aspect of democracy, without which the system collapses.

There’s another way in which claims of electoral fraud have already done quite a bit to poison American democracy, however, and they have for the most part done so without widespread condemnation. Using the pretext of supposed voter fraud, a number of states across the United States have, over the last decade or so, imposed a range of laws that are ostensibly designed to combat such fraud. They include requirements that voters show ID, shorter early-voting periods, and purges of voter rolls.

Critics of these laws point out that given the scant evidence of fraud, these measures represent a solution in search of a problem. Yet they also introduce their own problems, because they disproportionately disenfranchise minority voters.

Usually, advocates of voting restrictions argue that such laws an unfortunate but necessary measure to guarantee clean elections, though others frequently trip up and say that the goal is to elect more conservative candidates. Courts have, in several cases, found these laws to represent unconstitutional voter suppression. In July, a federal appeals court struck down a North Carolina law, saying it intentionally disenfranchised blacks.

“In what comes as close to a smoking gun as we are likely to see in modern times, the State’s very justification for a challenged statute hinges explicitly on race—specifically its concern that African Americans, who had overwhelmingly voted for Democrats, had too much access to the franchise,” wrote Judge Diana Gribbon Motz.

Restrictive voting laws are only the most visible example. After losing the 2012 election, some Republicans briefly flirted with a plan to reform the electoral college, awarding electoral votes based on congressional districts—a change that would have boosted GOP chances yet produced a much less democratic result, thanks to congressional redistricting that favors Republicans.

It is heartening to see officeholders and officials on both sides of the aisle denouncing Trump for dangerous and baseless claims. But the Politico/Morning Consult poll isn’t just the product of one election cycle’s worth of allegations about voter fraud.

Many of Trump’s most widely decried claims—about immigrants, or crime rates, or government unemployment statistics—represent distorted, caricatured forms of arguments that have long circulated in political discourse, mostly on the right, for long, often with little challenge. Those arguments have produced policies that have prevented Americans from exercising their right to vote, an effect arguably closer to election rigging than anything else that has happened this cycle.

October 16, 2016

Behind-the-Scenes Bollywood

Bollywood is known for its sumptuous costumes, elaborate dances, and catchy songs. Mark Bennington was interested in something else: What did the Indian acting community look like off the screen? His new book, Living the Dream: The Life of the 'Bollywood' Actor, features interviews and photographs of 112 personalities, from students to superstars. They are pictured reading their lines on the train, sipping falooda, and trying to make it in Mumbai. The interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity.

October 15, 2016

The Charged Protest of the Swet Shop Boys

On “Din-e-Ilahi,” the last track of a new album by Swet Shop Boys, the Queens-born rapper Himanshu Suri (Heems) observes the hypocrisy in how the West tends to perceive South Asian culture:

They comin’ for the culture man, like they was on a mission

Ask me bout the Kama Sutra, different sex positions

Used to hate the clothes, they ask where’d I get the stitchin’

Used to call me curry now they cook it in their kitchen

The facility with which Heems collapses the anxieties of a global South Asian diaspora into just a couple of bars is emblematic of the mission of Swet Shop Boys, a bold bunch of hip-hop iconoclasts who use irreverent humor and sharp satire to make serious political points about desi identity in the post-9/11 West. On its debut record, Cashmere, the group—which consists of the American-born Heems, the English rapper and actor Riz Ahmed (Riz MC), and the London-based producer Redinho—reclaims racial stereotypes and throws them back at listeners, via a colorfully chaotic album that explores serious concerns with deceptively laid-back swagger.

Both Heems and Riz MC have a history of employing comedy in their music. Heems’s former group, Das Racist, leapt to internet fame in 2008 with “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell,” a song about missed connections at a fast-food restaurant that led to the act being labeled as “joke rap”—a descriptor that undermined its fusion of absurd humor and social commentary. Riz MC, perhaps better-known to American audiences for playing Naz in the hit HBO show The Night Of, attracted controversy in 2006 for a song he released titled “Post 9/11 Blues.” The track, an almost childish sing-along with flutes, and xylophones, featured the chorus “Blair and Bush sitting in a tree / K-I-L-L-I-N-G,” and was deemed so inflammatory it was banned on British radio. While seemingly frivolous, the song considered the very real rise in violence against Muslims in the immediate wake of the attacks in New York.

Cashmere arrives in another era of heightened Islamophobia both in the U.S. and in Britain, but its humor feels different. There’s an underlying urgency behind all the jokes, a sense that the stakes are higher than they’ve ever been, but while the satire is grounded in the political moment, Swet Shop Boys also sound like they’re having fun. Heems and Riz’s divergent cultural upbringings—Heems is a first-generation American born in New York to Hindu-Punjabi parents while Riz was raised by Pakistani immigrant parents in the suburbs of London—afford them common ground on which both rappers are able to draw on the familiarity of shared experiences to tackle issues of racism and tokenization.

Like airports. Or, specifically, the experience of going through international borders as young men of South Asian descent. On “T5,” the opening track on Cashmere, Swet Shop Boys tackle racial profiling with a nonchalance that feels both deliberate and poignant, while a shehnai, a wind instrument, sounds off in the background. “Oh no we’re in trouble,” the duo raps, “TSA always wanna burst my bubble / Always get a random check when I rock the stubble.” The tightly-wound, minimally-percussive “No Fly List” picks up where “T5” leaves off, with Heems’s refrain echoing an unfortunate paradox over a rumbling synth: “Like I’m so fly bitch / But I’m on a no-fly list.” On “Shoes Off,” Riz raps over an airy synth line and muffled kick drum about the irony of being detained and interrogated at a London airport days after winning an award at the Berlin Film Festival for portraying an accused jihadist in the The Road to Guantanamo.

Swet Shop Boys proffer a vocabulary that has never really existed in rap music before.

On Cashmere, airports become transitional spaces where identity is threatened and people of color are constantly forced to justify their presence on Western soil. As first-gens, Riz and Heems have dwelt in these in-between spaces their whole lives. Their approach to dealing with the absurdity of racial profiling is to turn around and laugh at it; they understand how their humor acts not only as a means of protest but also as a way of providing comfort in a shared experience.

On many tracks the jokes are less heavy, although no less sharp, particularly when they skewer cultural appropriation. The largely white, Westernized Hare Krishna sect of Hindus is a particular focus: On the pounding party-anthem “Zayn Malik,” named for the sole Muslim member of the boy band One Direction, Riz paints an elaborate picture of forcing a ponytail onto the head of a skinhead to turn him into a devotee, while Heems describes feeling more out of place in a crowd than a brown guy would at a Hare Krishna temple. Later, he calls out the double standard in popular culture’s commercial attraction to the aesthetics of the Indian lifestyle, but not to its people or history, calling it “Hinduism in the bottle / Marketed and sold like fairness cream by the model.”

The language and references on Cashmere proffer a common dialect that will particularly resonate with Indians, Pakistanis, and those caught in the dualities. Even the name of the album is a sneaky pun on Kashmir, the hotly contested political region in the subcontinent that India and Pakistan have fought over since 1947. The group’s name, too, is a nod to the British pop duo the Pet Shop Boys, the commercial exploitation of cheap labor in the subcontinent, and maybe even Indian dessert stores, often referred to as “sweet shops.” By cracking inside jokes about the expectation to be doctors, using Urdu and Hindi slang, or making references to Afghani beef and sloppy saag, to Mowgli and Bagheera, to Mughal emperors and cult Bollywood tunes, Heems and Riz take instantly recognizable pop-cultural cornerstones for South Asians and turn them into motifs for the everyday discrimination that brown people face. It’s a vocabulary that has never really existed in rap music before.

On the ominous “Half Moghul Half Mowgli,” Riz acknowledges this. He mentions that growing up, his only heroes were black rappers, so to him, “Tupac is a true Paki.” On Cashmere, Swet Shop Boys are taking up, albeit a little facetiously, the mantle of sub-continental icons who are marking a way forward for inclusive rap. The jokes on the album may feel tailored to a desi audience, but in packing so much that’s familiar, painful, and unspoken into the space of 35 minutes, they make the record more generally human. Cashmere feels like a homecoming for the Swet Shop Boys, who seem to have finally found an unlikely place perfectly equidistant from India, Pakistan, New York, and London: hip-hop.

Bob Dylan and Oscar Bait: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Bob Dylan, Master of Change

Greil Marcus | The New York Times

“Songs move through time, seeking their final form. What happens on that path is only partly up to the writer, the singer, the musicians. It may be partly up to the audience hearing the songs, watching them as they are performed, reshaping the song. That is why, perhaps, it is the fact of Bob Dylan’s songs moving through time, and the way they have taken on elements of those times as they moved through them, that matters most on this interesting occasion.”

Bob Dylan Is a Genius, But He Shouldn’t Have Gotten the Nobel

Stephen Metcalf | Slate

“The distinctive thing about literature is that it involves reading silently to oneself. Silence and solitude are inextricably a part of reading, and reading is the exclusive vehicle for literature.This is historically contingent in every way: Literature as a silent and lonely activity is scarcely older than the printing press.”

City of Women

Rebecca Solnit | The New Yorker

“In a subtler way, names perpetuate the gendering of New York City. Almost every city is full of men’s names, names that are markers of who wielded power, who made history, who held fortunes, who was remembered; women are anonymous people who changed fathers’ names for husbands’ as they married, who lived in private and were comparatively forgotten, with few exceptions.”

The Long Coming-Out of the NBA’s First Openly Gay Male Referee

Kevin Arnovitz | ESPN

“In Kennedy's mind, it was no real deprivation to stay in the closet on the court—for a while, at least. He might not have declared himself openly gay, but when did referees publicly declare anything about themselves? They are the most visible, least known people in sports—always present, never heard.”

What’s Love Got to Do With It?

Emily Gould | The New Republic

“We watch these shows the way we spread dark gossip, as an inoculation against our worst fears about marriage and ourselves. These shows tell the truth about what happens in the months and years after the papers are signed, the wine is drunk, the guests scattered.”

Sin, Cinema, and Nate Parker

Alissa Wilkinson | Vox

“The most important and even appropriate thing a film like The Birth of a Nation could do now, in the wake of all this mess and morass, is to convince just a few people that just because the Bible is quoted by someone, even a powerful guy with a lot of money and an out-of-control will to power, doesn’t make whatever it’s supporting true, right, or just.”

Is There Even Such a Thing as ‘Oscar-Bait’?

Mark Harris and Kyle Buchanan | Vulture

“Sometimes, ‘Oscar bait’ is just a careless catchall meant to describe all fall films, but more often, it’s used the same way a snooty critic might say ‘Sundance movie’ as a pejorative: There’s an implication that what appears to be prestigious is, in its own way, as formulaic as a Marvel blockbuster.”

How Steph and Ayesha Curry Became the ‘Good’ Black Family

Israel Daramola | Buzzfeed

“The Currys have become exemplars of an innocuous, extremely marketable family—close-knit, attractive, Christian, and charming with a tendency towards corniness. But their popularity has proven controversial. Any family would buckle under such pressures—and so, the cracks in the Currys’ image have begun to show.”

October 14, 2016

The Thwarted Domestic Terrorist Attack on Somali Refugees

NEWS BRIEF Federal prosecutors charged three Kansas men Friday with domestic terrorism for planning an attack on Somali immigrants.

The three men from Liberal, Kansas, in the southwest part of the state, were targeting a nearby meatpacking town, planning to detonate bombs in an apartment complex where around 120 Somali immigrants reside.

According to the affidavit:

This is a militia group whose members support and espouse sovereign citizen, anti-government, anti-Muslim, and anti-immigrant extremist beliefs.

This comes after an eight-month investigation into the militia group called “The Crusaders.” The FBI even used an informant, who attended their meetings. Mother Jones adds:

Curtis Allen, Gavin Wright, and Patrick Stein allegedly contemplated murder, kidnapping, rape, and arson before settling on a different plan: They would obtain four vehicles, pack them with explosives, and set them off at the four corners of an apartment complex in Garden City, Kansas, that housed a mosque and 120 Somali refugees.

The three men were arrested with nearly 2,000 pounds of firearms and ammunition. They were planning to attack on November 9, one day after the election.

Why a Connecticut Judge Tossed the Sandy Hook Lawsuit

NEWS BRIEF A Connecticut judge threw out a lawsuit against the gun manufacturer who made the weapon used in the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, which left 20 children and six teachers dead in 2012.

Barbara Bellis, the state Superior Court judge, said Friday the families of the victims who were slain at the hands of Adam Lanza could not prove there was a relationship between gunmaker Remington Outdoor Company, which produces the Bushmaster AR-15 rifle, and the shooter. Bellis argues in her decision there was no “negligent entrustment of a firearm.” The families had argued the rifle should never have been available to the public.

Josh Koskoff, one of the lawyers representing the families, said Friday:

While the families are obviously disappointed with the judge’s decision, this is not the end of the fight. We will appeal this decision immediately and continue our work to help prevent the next Sandy Hook from happening.

If the lawsuit, which was filed by the families of 10 of the victims in January 2015, had gone forward, it could have been a devastating blow to the gun industry, which has long been protected by federal laws and not held liable for mass shootings.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower