Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 49

November 3, 2016

The Heartbreak and Joy of Being a Lifelong Cubs Fan

It was October 15, 2003, ten days before my tenth birthday. The previous night, the Chicago Cubs had been five outs away from returning to the World Series for the first time in 58 years, before the most infamously cataclysmic half-inning in the history of the franchise had forced a Game 7.

There were two outs in the bottom of the second and a runner on third, the Cubs were down 3-1, and the pitcher was up to bat. Kerry Wood was an exceptionally good hitter for a pitcher, but he was still a pitcher, and this was still the National League Championship Series, and these were still the Cubs.

I was sitting at home on the couch with my mom, my hands clasped together, my chin resting on my hands, watching Wood go deeper and deeper into the at bat. 0-1 … 1-1 … 1-2 … 2-2 … Full count. And then: a swing, a hit, a long fly ball to left center, Wood running around the bases, Wrigley going wild, the announcers going wild, me going wild, our phone ringing.

My mom ran over to pick it up, and it was my dad, who was at Wrigley Field with my older brother, on the other side of the line. She could barely hear his words over the crowd, still cheering as Wood walked off the field: “Do not emotionally surrender to this team.”

What my dad didn’t know, but probably suspected, was that I already had.

I had surrendered because I loved that team—in fact, it was the first team I had ever loved. I loved Moises Alou out in left, and I was worried he felt guilty about the Bartman incident in Game 6. I loved Mark Prior and Wood, no matter if they were throwing strikeouts or giving up home runs. I loved Alex Gonzalez, having quickly forgiven him for letting that ground ball go through his legs the night before. I loved Mark Grudzielanek and Corey Patterson, Aramis Ramirez and Hee-Seop Choi, Kyle Farnsworth and Damian Miller, all despite their flaws. I loved Sammy Sosa and was adamant he wasn’t on steroids. (He was.)

What my dad didn’t just suspect, but probably knew, was that that team, the one I loved, was going to lose, and it was going crush me.

They did, and I was.

In mid-October 2003, I had never driven a car, left the country, or dyed my hair. I was yet to cast a ballot, open a bank account, go though a breakup, or even go on a date. I doubt I had ever done a load of laundry. At nine years old, I hadn’t experienced much, and the Chicago Cubs—by losing that game 9-6 and dashing the dream of a World Series on the North Side—had just taught me about heartbreak.

But even for a die-hard 9-year-old Cubs fan, baseball isn’t everything. That night turned into the next day, and that day turned into the next week. Nine turned into ten. October to November. 2003 to 2004. Elementary school to middle school. Middle school to high school and high school to college. I still went to games, I still cheered, and I was still a fan. But now, when Alfonso Soriano dropped a ball out in left, I wasn’t so quick to forgive. When Derrek Lee struck out in a big moment, I wasn’t so quick to forget. I had learned that being a Cubs fan was about balancing naïve optimism and relentless pessimism, and I was determined to never again let the former eclipse the latter.

Then, came this year.

For the first time in 13 years, I found myself a little too excited. I was a little too happy when they won, a little too sad when they lost. The advantage of supporting a team that hasn’t won since a decade before the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire is that you barely notice losing most years. When other teams are bad, their fans are sad. When the Cubs are bad, we just are.

The author in 2003

We watch the games, we pick our favorite players, we talk about the farm system, we drink our beers, and of course we cheer when they win, but we rarely expect them to. But every once in a while, when a really good team comes along, you find yourself thinking, just thinking, that maybe, just maybe, this might actually be the year. While this alone isn’t dangerous, the inevitable loss after you dare to hope—as I had learned back in 2003—will crush you with the weight of a thousand defeated Yankees, Giants, Marlins, and Phillies teams. So when I came home for Easter this past spring and went to Wrigley, and it smelled a little too good and the hot dogs tasted a little too fresh, I was worried. But then again I wasn’t, because I was still a Cubs fan, and this team was just so good.

By the time October rolled around this year, I had lost the battle—I was stoked. On the night they won the NLCS, my roommate and I started looking at tickets to fly home for that weekend and Games 3, 4, and 5. We thought we might be lucky enough to be in Chicago the night the Cubs won the World Series. Of course they went down 3-1. And of course we were fools—we’re Cubs fans.

They were going to lose, I told myself. But it was okay because I was prepared this time. But then they won Game 5. And Game 6. And suddenly, we found ourselves facing another Game 7.

Last night, as I watched Kris Bryant field that final out to make the Chicago Cubs the World Series Champions for the first time since 1908, I realized it was only then, in that very moment, that I was finally able to forgive that 2003 team. It sounds ridiculous, because it is. And now that I’m typing it, I wish I weren’t. But for more than a decade I had refused to truly love the Cubs, because when I was nine years old they had broken my heart.

Every Cubs fan has a story, and this is just mine. But it’s my suspicion that many of us are forgiving some team or another today. And if not some team, then some player, or some coach, or some umpire for that series, or that game, or that play that taught us to never emotionally surrender again. And that’s not a totally terrible thing.

The Secret Joy of Baseball Curses

For generations, the Chicago Cubs and the Boston Red Sox were twins in misery. Here were two of the most beloved teams in the league, both steeped in baseball folklore, both suffering epic championship droughts. We’re talking losing streaks so bad that they could only be explained by dark, supernatural forces.

The tales of those forces, like the pain of the losses they apparently perpetrated, were handed down from one generation to the next, woven into the identity of fandom. This is how curses become almost sacred, something to be cherished as much as despised. From 1918 to 2004, Boston endured the curse of the Bambino, a hex on the franchise that began with the loss of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees and lasted 86 long years, until the Sox finally won the World Series.

But the Cubs suffered even longer. The team’s World Series win Wednesday night marks its first championship in 108 years, a dry spell that’s often been blamed on the Curse of the Billy Goat. (To cut a long story short: A pub owner who was made to leave Wrigley Field during a World Series game in 1945, on account of the smelly pet goat he had with him, declared a curse on the team as a result.)

For those who doubt the ruthlessness of the baseball gods, consider the Bill Buckner tragedy of 1986, one of the most infamous moments in postseason history—and an incident that represents an overlap in the two team’s curses. Buckner, who had previously played for the Cubs, was blamed for throwing away the Red Sox’s chance at winning the World Series when he let a ball roll through his legs at first base, enabling the New York Mets to score a winning run.

An error so grave, at a moment so key, had to be evidence of the curse on Boston. But there’s a twist: Buckner was wearing his old Cubs batting glove under his mitt when he screwed up. “No wonder Buckner missed that ball,” Paul Lukas wrote in an essay for ESPN. “He never had a chance.”

And that’s the thing about curses. They attempt to reorder people’s sense of destiny, a carefully constructed fiction in sports fandom as it is. In reality, championships are won and lost with some combination of talent, physics, meteorology, and dumb luck. But to a fan, everything—really, everything—can be meaningfully connected to the outcome of a game. Wishing for a team to win isn’t enough, but wearing the right shirt—or growing the right beard, or partaking in the proper pre-game ritual—sometimes is.

In the end, a fantastic baseball game, or an ominous curse, is nothing more than a great story. But a great story, told the right way, can be everything.

And when that’s still not enough? It must be a curse. What else could explain the crush of defeat against all hope? A curse is more powerful than any player’s abilities, bigger than the team, greater even than the fandom. Which means a curse narrative runs counter to so much of how people otherwise engage in sports fandoms, in which individual control—or the illusion of it—is seen as paramount.

Contradictory though it may seem, this is all part of “a beloved, time-honored game steeped in nostalgia,” Mickey Bradley and Dan Gordon wrote in their book, Haunted Baseball. “[Curse stories] provide a lens through which to view a team’s past—usually a heartbreaking past—that connects disappointment to tradition and legacy.”

By their very nature, curse stories transcend a single championship or season. This speak’s to baseball’s deepest cultural value, and the way a person’s love of it is shared—often quite intimately—with the people they love most.

If baseball can be poetry, and it can, then why shouldn’t it be subject to the narrative rules of epic literature? Belief in a curse speaks to something deeper about the game. It has the power to elevate a team’s history, and a fan’s devotion, to an art form. Mourning yet another loss, inheriting lifetimes of disappointment, and rooting for the team anyway—this isn’t just a form of obsession or blind optimism. It’s an act of devotion.

In the end, a fantastic baseball game, or an ominous curse, is nothing more than a great story. But a great story, told the right way, can be everything.

* This article originally mischaracterized the timing of the Bill Buckner incident in 1986. It occurred during the World Series, not earlier in the playoffs. We regret the error.

What Beyonce's ‘Daddy Lessons’ Had to Teach

Beyoncé’s foray into country music, “Daddy Lessons,” is a song about going to war, about fighting the cads, about shooting before you get shot. But in the context of her album Lemonade, it’s also a moment of self-reflection about broken trust being passed down through generations. It’s a pivot point on the album’s journey from anger to peace.

Perhaps Beyoncé came to the Country Music Awards to put up a fight: a fight for the song’s legitimacy as country, for the black lineage of a genre typically thought of as white, and/or for some play on rural airwaves. But watching her joyous, wide-screen hoedown with the Dixie Chicks—followed by the release of a great new collaborative version of “Daddy’s Lesson”—it seemed more like she was on a mission of togetherness and friend-making, which is not an insignificant thing in this current moment.

Rumors that the pop superstar would perform at the Nashville ceremony hit the internet shortly before before the show began. Watching the telecast’s first two hours—a sprightly, revue-like affair highlighting the show’s 50-year history, anchored affably by Brad Paisley and Carrie Underwood—it was clear that the CMAs themselves didn’t want to make a big deal about Beyoncé: Paisley only mentioned her once or twice, quietly, when talking up the night’s coming attractions, and the CMAs official Twitter account never mentioned her at all.

This might have been a result of Beyoncé’s own penchant for mysteriousness. Or it might have been the producers playing to the culturally conservative portions of country’s fanbase, the people on social media airing their outrage that Beyoncé was there at all. (Of course, plenty of other country fans and performers expressed enthusiasm.) On Twitter, Paisley seemed to be doing pre-emptive explanation, writing, “Frequently, country crosses over. But every now & then a major pop superstar wants to be a part of this too. Welcome, Beyoncé.” The first reply: “fuck Beyoncé she supports thugs plus her music is garbage.”

Paisley is right that pop stars sometimes cross into country, with Nick Jonas, Justin Timberlake, and Rihanna having played the CMAs in previous years. But Beyoncé has a better claim than many. Raised in Houston with a mom from Louisiana, she recorded “Daddy Lessons” not as a pastiche—not as pop-rock with a cowboy hat on like Lady Gaga’s Joanne—but as a meticulous tribute: New Orleans brass, concrete-yet-mythic storytelling about fathers and lovers and whiskey and tea, whoops and harmonica and foot stomps. The Dixie Chicks have taken to covering the song on their recent comeback tour.

At the CMAs, “Daddy Lessons” fit right in, save a few factors. One was the size of the performance. In typical Beyoncé fashion, she led a regiment, filling the stage for a backyard-barbecue that became a Bourbon Street parade with a fabulous sax solo in the bridge. It also stood out for another reason: She and her musicians were some of the only black people at a ceremony celebrating an art-form whose origins, as is well documented, were nowhere near entirely white.

Reading the online blowback to Beyoncé’s CMAs presence, though, highlights how many Americans’ issues with her are less about songs than politics. Her music remains big-tent, entertaining fare, but has recently been threading in more and more explicit nods at her racial identity, which is apparently not a neutral move in 2016. No song denigrates white people; no song denigrates cops; and yet upon Beyoncé’s performance, the conservative commentator Toni Lahren tweeted, “Just know most country fans #BacktheBadge #BacktheBlue.”

Beyoncé has already addressed this sort of rhetoric in an Elle interview: “Anyone who perceives my message as anti-police is completely mistaken. I have so much admiration and respect for officers and the families of officers who sacrifice themselves to keep us safe. But let's be clear: I am against police brutality and injustice. Those are two separate things." These aren’t the words of someone reveling in divisiveness—they’re of someone with a political point of view who’s trying to persuade others not to fear it.

Much of the audience was thrilled to have her; maybe the others began to see how they might all get along.

In a way, the night felt like a cleanser after the recent controversy surrounding Amy Schumer’s video cover of “Formation” featuring Goldie Hawn, Wanda Sykes, and other stars. “Formation” is, famously, Beyoncé’s big black-pride statement of 2016, and many viewers felt it was offensive for Schumer and other white women to seem to claim it for themselves. I really wonder what Beyoncé thinks, though. As Schumer pointed out when defending herself, she had Beyoncé and Jay Z’s approval, as her video premiered exclusively on Tidal. Moreover, Beyoncé’s cultural primacy owes to the fact that she’s conquered the listening habits of everyone—she’s making money off of white people lip syncing to “Formation” at home as well as black and brown people. Schumer was dancing along; she was also bowing down.

What Beyoncé sells with her music is, in part, a swaggering, powerful persona anyone can inhabit for a few minutes at a time. The political statement lies in the realization that this magnetic persona is a black woman's in a culture where black women so often don’t get their due. A performance like the CMAs one shares in this dynamic. On stage with the Dixie Chicks, she flexed her might, showed the versatility of her gift, highlighted country’s musical lineage, and let everyone partake. Much of the audience was thrilled to have her; for the others, maybe some could begin to see how they might all get along.

A Blow to Brexit

The U.K. High Court’s ruling Thursday that the government does not have the authority to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty—the formal mechanism that would begin negotiations for the country’s departure from the European Union—is a blow to Prime Minister Theresa May. The ruling, which the government says it will appeal to the Supreme Court, contends that doing so without seeking parliamentary approval, which May had argued was within her power, would effectively erode parliament’s sovereignty, which is enshrined in U.K. law. In other words: U.K. lawmakers must vote on whether to invoke Article 50.

This puts the government in an awkward position. Her predecessor as prime minister, David Cameron, had staked his political future letting voters decide on the U.K.’s continued membership in the EU. And despite dire warnings about the economic and social costs of Brexit, polls remained close and tightened during the final days. Still, Cameron and others—even those championing Brexit—suspected the “Remain” side would eventually triumph in the June 23 referendum. But it wasn’t even close: 52 percent voted to leave versus 48 percent who wanted to stay. Cameron resigned as prime minister and, subsequently, as a member of Parliament. After much political jockeying, and backstabbing, among the more high-profile proponents of Brexit within Cameron’s Cabinet, May, who had tepidly supported “Remain,” emerged as the candidate to replace him. As prime minister, she said she would respect the wishes of the voters, stacked her Cabinet with prominent “Leave” campaigners, and said that she would invoke Article 50 in March 2017, thereby setting in motion an expected two-year process to negotiate the U.K.’s future relationship with the EU.

But a legal challenge, which was partially crowdfunded, on whether the government had the authority to do so complicated that plan.

The government’s position was that Parliament had, in fact, assented to the government’s authority on Article 50 when it approved the European Communities Act in 1972. That’s the law Parliament passed to allow the U.K. to join what would eventually become the EU. Not so fast, the High Court said Thursday: “[W]e decide that the government does not have power under the Crown’s prerogative to give notice pursuant to Article 50 to withdraw from the European Union.” Furthermore: “Parliament is sovereign and can make and unmake any law it chooses.”

The legal action against the government’s position was brought by Gina Miller, an investment-fund manager. Miller has said that the question in the referendum on whether to “Leave” or “Remain” in the EU was “far too binary.” She was, she told Business Insider, for “remain, reform, and review.” She argued that if Article 50 were invoked without the proper steps, it would weaken the U.K.’s negotiating position during Brexit talks with other EU nations. But perhaps more pertinent was her argument that the government's invocation of Article 50, without Parliament's buy-in, would set a dangerous precedent.

“We must remember that the U.K. doesn’t have a written constitution—it is made up of precedent,” she told Business Insider. “If we set the precedent that a government can use their royal prerogative to take away people’s human rights, that is taking us into a very dangerous political environment.”

What does all this mean for Brexit? If the U.K. government wins its appeal at the Supreme Court, it will mean the government does have the authority to invoke Article 50, presumably next March. But even if it doesn’t, and lawmakers indeed do get a say in the matter, it’s highly unlikely they will undo the decision of a majority of voters—no matter what the U.K.’s elites think of Brexit.

Still, the court’s decision is likely to heighten the political and economic uncertainty triggered by the Brexit vote. Although some of the most dire warnings about the impact of a vote for Brexit have yet to materialize, the costs have already been high for the U.K. economy and its currency, mostly because it’s unclear what shape the U.K.’s future relationship with the EU will take. While some Brexit proponents had argued that the U.K. would continue to have free trade with the bloc after it leaves, EU officials have dismissed that idea unless the U.K. allows the free movement of EU citizens—a highly unlikely proposition given that many Brexiters listed immigration from the EU as their primary reason for voting “Leave.” Nor is the EU’s ability to forge the sort of agreement that will satisfy all sides assured. As it showed during recent trade negotiations with Canada—which nearly failed due to the objections of a single region in Belgium—the EU is not a monolithic entity. Free trade, while popular in the 1990s when the bloc was born, is now facing a backlash globally, and imposing political costs on many of its most ardent supporters. So while the High Court’s ruling was a major twist in the Brexit saga, in one respect the court has left the situation much the same as it was before: The U.K.’s future remains very unclear.

Obama Sweats Out the Last Days of the Election

CHAPEL HILL, N.C.—Every time Barack Obama comes to campaign for Hillary Clinton in North Carolina, he starts off with the same spiel. It goes something like this: “I just like North Carolina. I love the people in North Carolina. When we used to campaign here, I used to say even the people who aren't voting for me are nice.” Then there’s usually a riff about basketball, or barbecue, or both.

The president has had ample opportunity to workshop this bit, because he’s been a frequent visitor to the Old North State, campaigning for his would-be successor. His first appearance on the campaign trail this year came alongside Clinton in Charlotte. Just a few weeks ago, he was in Greensboro. On Wednesday, he was in Chapel Hill, and he’ll be back on Friday for stops in Fayetteville and Charlotte.

Related Story

The Joshua Generation: Did Barack Obama Fulfill His Promise?

Obama’s affection may be genuine—he also vacations near Asheville—but it’s not the reason he’s been visiting so often. His sojourn was strictly what he repeatedly insisted was “bidness” (as opposed to “business.”) With less than a week to go, the polls show a very tight race in North Carolina.

“We don’t win this election, potentially, if we don’t win North Carolina,” he said. “So I hate to put a little pressure on you, but the fate of the republic rests on your shoulders. The fate of the world is teetering, and you, North Carolina, are going to have to make sure that we push it in the right direction.”

The president was joking, only he sort of wasn’t. There’s been a discernible change in his tone over the course of his appearances. When he came to Charlotte, in July, he just seemed happy to be out on the trail, and focused on how great Clinton was. By the time he got to Greensboro on October 11, Clinton was at perhaps her acme. After two debates, one tape of Donald Trump boasting about sexually assaulting women, and several accusations out there, the Republican seemed cooked. Obama was in high spirits, ready to close the deal with a series of jokes at Trump’s expense.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the landslide. With five days left, the race looks as close as ever, both nationally and in North Carolina. Hence Obama’s effective message on Wednesday: Are you kidding me, America?

“This choice actually is pretty clear, because the guy that the Republicans nominated—even though a bunch of them knew they shouldn’t nominate him—the guy they nominated who many of the Republicans he is running against said was a con-artist and a know-nothing and wasn’t qualified to hold this office—this guy is temperamentally unfit to be commander in chief and he is not equipped to be president,” Obama said.

He’s said things like that before, but now he was just getting started. This was Obama as media theorist, a role he seem to enjoy, subscribing to the claim that Trump’s long spree of bizarre comments has produced a sense of fatigue.

“And this should not be a controversial claim,” Obama continued. “It really shouldn’t. I mean, it’s strange how, over time, what is crazy gets normalized and we just kind of assume, well, you know what, he said a hundred crazy things, so the hundred-and-first thing we just don’t even notice.”

Obama didn’t mention the controversy that has precipitated a crisis of confidence for Democrats—the letter written by FBI Director James Comey last week, informing members of Congress of the discovery of new emails potentially related to the investigation into Clinton’s use of a private email server. Obama is caught in a tricky triangle between Comey, the Republican who he selected to lead the FBI, and Clinton, his designated heir. In an interview published earlier Wednesday, Obama offered veiled criticism of the FBI.

“I do think that there is a norm that when there are investigations we don't operate on innuendo and we don't operate on incomplete information and we don't operate on leaks,” Obama said. “We operate based on concrete decisions that are made.”

In Chapel Hill, he stuck to criticizing Trump, methodically laying out an indictment of the Republican nominee’s character, temperament, and preparedness.

“We don’t win this election, potentially, if we don’t win North Carolina. So I hate to put a little pressure on you, but the fate of the republic rests on your shoulders.”

“Look, we have to acknowledge, he’s got support,” Obama said. “He’s got support here in North Carolina. He’s got support in other states. And part of it is, is because he’s been able to convince some people that he’s going to be their voice.” But he insisted: “We have to stop thinking that his behavior is normal, that it’s within the bound of what has, up until this point, been our normal political discourse.”

Now Obama was rolling, unspooling his disbelief, laughing in that way one does when something is funny, but more funny-strange than funny-haha, his voice cracking into a higher register.

“You've got some Republicans in Congress who are already suggesting they will impeach Hillary,” he said. “She hasn’t even been elected yet. It doesn’t matter what evidence, they just—they'll find something. That's what they're saying already. How does our democracy function like that?”

The Democratic Party seems somewhat shellshocked by the state of the race—even if Clinton has an edge, Democrats still can’t quite believe that they have to fight this hard against this opponent. One culprit is Clinton’s acknowledged charisma gap. Obama remains a bigger draw, and fire marshals said that 16,200 people attended the rally, making it the second-biggest Clinton campaign event of the year. Several attendees told me that while they were With Her, they had cut class or cut work mostly for one last chance to see Obama as president. It was an unseasonably warm November day, topping 80, and volunteers handed out water or assisted attendees who overheated during a brief performance by James Taylor. The line to get in stretched as far as the eye could see, away from the Astroturf where a stage had been assembled and past the Frank Porter Graham Student Union, named for the godfather of North Carolina liberalism.

That political tradition faces a turning point on Tuesday. One can make a case for the state going either way. Obama won narrowly in 2008 and lost narrowly in 2012, and Clinton has led most polls in the last month, but a couple recent polls have shown Trump leads. The New York Times’ Upshot finds evidence of a Clinton lead in early voting; elsewhere, the newspaper sees softer turnout among African American voters, the cornerstone of the Obama coalition.

Clinton’s prospects in North Carolina will rise or fall based on turnout among black voters and in young, white, liberal bastions like Chapel Hill—home to the University of North Carolina, many of whose students came out Wednesday—and the rest of the Research Triangle. Those are also two groups with which Obama remains popular.

Geoffrey McGee, a junior at UNC, was playing hooky to attend the rally, though he did carry a well-worn paperback copy of Passage to India with him in line. Although he was to the left of Clinton on a range of issues, he was excited about her, which he said might be atypical in the broader student body. “There’s excitement about stopping Trump,” he said. “To say there’s excitement about Clinton might be overstating it.” He was nervous about the recent tightening of the polls, but not panicked. “I just like to believe it couldn’t happen here,” he said. “I think there’s a sense of decency, just mutual cooperation, left in this country.”

As for African American votes, the reasons behind the drop-off are disputed. Some decrease was expected once Obama was off the ballot—though he argued that although he is not on the ballot, his legacy is—but the decrease has been sharper than expected. Some of that is probably lesser enthusiasm for Clinton, but it may also have to do with voting rules. While a law limited early voting and requiring voter ID to vote, among other provisions, was struck down by a federal court in July, some counties still have fewer early-voting locations than in 2012. Guilford County, home to Greensboro and many African American voters, had a single early-voting location for the first of two weeks of voting, though more are now open.

One black voter Clinton needn’t worry about is Cynthia Edwards Paschall, who had taken the day off work and come out with her sisters (“a bunch of nasty women!”) to see one last appearance by an African American president—a sight she thought she’d never witness. She was a little more confident about voting.

“I think North Carolina is really a blue state at heart,” she said. “We need to change out the formula of the Jesus juice they’re drinking so they’re not so righteous they’re wrong.”

“We need to change out the formula of the Jesus juice they’re drinking so they’re not so righteous they’re wrong.”

As Paschall implied, the presidential race isn’t the only contested spot on the ballot. Attorney General Roy Cooper, who is seeking to unseat Republican Governor Pat McCrory, also spoke at the rally. That’s a little bit unusual—he has made himself scarce at many Clinton campaign events, even though many polls show him with a narrow lead. But Deborah Ross, who’s running for U.S. Senate, has been a frequent presence at Clinton events. Once considered a long shot, Ross has narrowed her gap with Senator Richard Burr far enough that some Democrats think she could win, buoying hopes that a President Clinton would enter office with a Democratic Senate.

Obama went hard on Burr, returning again and again to take shots at him. “He and I came in together when we were in the Senate, and personally he’s a decent guy,” Obama said. “But when I hear him say there’s not a separation between me and Donald Trump—that’s troubling. Either he actually means it, in which case he agrees with everything Donald Trump says; that what it says—that’s what you mean when you say there’s not a separation. Or he doesn’t mean it and he’s just saying it to get elected. That’s not good either way.”

He spent some time going over a recording published by CNN this week in which Burr joked about Hillary Clinton being shot and pledged to work to block any Clinton appointee to the Supreme Court if she won. “Eleven years ago, Richard Burr said a Supreme Court without nine justices would not work,” Obama said. “Well, what changed? What, only Republican presidents get to nominate judges? Is that in the Constitution? I used to teach constitutional law. I've never seen that provision.”

While liberal commentators and national Democrats spent the day pondering whether to enter full-blown panic or stick with mere serious digestive distress, there was no sign of such extreme worry in Chapel Hill. Perhaps it was just too nice a day and people were too excited to see Obama. As he wrapped up his remarks, the president tried to strike a balance.

“You have a chance to shape history,” he said. “What an amazing thing that is. If Hillary wins North Carolina, she wins. And that means that when I said the fate of the republic rests on you, I wasn’t joking. But that shouldn’t make you fearful, that should make you excited.” Sometimes, however, it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.

November 2, 2016

In Hacksaw Ridge, Faith Is a Bloody Business

Desmond Doss, the true-life hero of Mel Gibson’s new film Hacksaw Ridge, has a few things in common with the director’s other favorite protagonists. He’s stoic to a fault, a Seventh-day Adventist who’s eager to volunteer for World War II but refuses to carry a weapon, infuriating his commanders. He’s a man of deep faith, a combat medic who won the Medal of Honor because of his daring rescue of 75 comrades while under fire at the Battle of Okinawa. He’s someone who suffered through unspeakable horror—exactly the kind of nightmare Gibson takes strange relish in depicting—and managed to survive.

Hacksaw Ridge, like most of Gibson’s other films, is a fairly simplistic work. But it’s undeniably effective, a movie about the power of religious conviction that batters viewers with depictions of horrific violence and chaos. Like the lead characters of The Passion of the Christ or Braveheart, Doss represents Gibson’s admiration for rigidity and sheer force of will. But unlike Gibson’s previous true-story protagonists, Doss’s life has a happier ending, lending an extra note of triumph for Gibson to use as a cudgel. It’s hard not to feel euphoric when Hacksaw Ridge is over—but that’s more because the brutality has finally come to an end, and less because it’s offered any great insight.

Before the movie gets to the climactic events at Okinawa, though, it spends 75 hokey minutes with Doss growing up in Lynchburg, Virginia. As played by Andrew Garfield, Doss is an appealing protagonist—he’s a kindly, soft-spoken beanpole who tends to his family’s ranch and tries to keep his haunted father (Hugo Weaving), himself a veteran of World War I, from raging at his deeply religious mother (Rachel Griffiths). Doss falls for a local nurse named Dorothy (Teresa Palmer) and is eventually motivated to enlist in the U.S. Army, despite his father’s deep trauma and his mother’s pacifist objections.

Doss is a fascinating bundle of contradictions, and Garfield captures this by projecting an almost alien (or perhaps divine) quality in Doss’s baleful smiles. Here is a conscientious objector who nonetheless believed World War II was a just battle against evil, a man who refused to commit violence but wanted to aid those called on by their country to do so. It’s the perfect project for Gibson, a director who invests his heroes (William Wallace, Jesus Christ, and Apocalypto’s Mayan warrior Jaguar Paw) with one-dimensional goodness that endures even as they are besieged on all sides by intense (and very cinematic) cruelty.

First, Doss suffers through basic training, bullied by his company (who view him as a coward for not picking up a rifle) and his commanding officers (who see him as an insubordinate for not following orders). Vince Vaughn brings nothing original to the role of a foul-mouthed drill sergeant, but he does provide some pep to the film’s saggy middle act, and the jarheaded Sam Worthington is perfectly believable as the group’s commanding officer. The rest of Doss’s unit is filled out with relative nobodies, a cast of grunts ready to either meet their grim death on the battlefield or get dragged to safety by the hero. The philosophical dispute over Doss’s pacifism is rendered in the broadest possible terms (he’s frequently bathed in heavenly light as he sticks up for his beliefs). He’s branded disobedient by every level of authority, but Gibson is obviously stacking the deck against all of Doss’s detractors, confident in the knowledge they’ll all be proven wrong.

Hacksaw Ridge works best as a film devoted to Doss, and a replication of the horror of the Pacific Theater.

When the film reaches Okinawa, Hacksaw Ridge grabs viewers and shoves them headfirst into an hour of bloody chaos. Gibson has long excelled at spectacular set-pieces of battle, but one reason Hacksaw Ridge stands out is because its war scenes are largely free of cliché. The carnage is unsparing and shocking, the military tactics (a push to take the island’s titular mountainous ridge) hard to understand, and the loss of life frustratingly random. Gibson’s veneration of Doss’s faith makes sense, but it’s difficult to tell whether the director is also using the movie to reflect on the amorality of violence.

Too often, Gibson leans heavily on Christ-like imagery as Doss proves his bravery—carrying wounded men on his back through artillery fire, even rescuing Japanese soldiers (who are mostly portrayed as a terrifying, faceless horde). As Doss repeatedly proves his devotion to saving lives without bloodshed, repeating his mantra of “Dear God, just let me get one more,” Gibson cuts to American soldiers breaking through the Japanese front and setting their enemies aflame—it’s a disturbing dichotomy the director seems to only have a slim grasp of. Ultimately, Hacksaw Ridge works best as a film devoted to Doss, and a replication of the horror of the Pacific Theater. For all the film’s verisimilitude, and its compassion for Doss, its larger message about war unfortunately feels as obscure as its hero’s own motivations.

The Message of Newtown: Please Don't Forget

To say that Newtown is difficult to watch is as insufficient as saying that the events of December 14, 2012, were difficult for the country to get through. The murder of 20 first-graders and six adults who were trying to save them at Sandy Hook Elementary School by a 20-year-old with a Bushmaster semi-automatic assault rifle and a history of behavioral disorders is one of the darkest stains on the recent history of America. After that day, the nation grieved. People mourned, and even marched. But, eventually, by necessity, they also moved on.

The point of Newtown, a new documentary by Kim Snyder airing in theaters nationwide November 2, is, in the rawest terms, to reopen old wounds. On the surface, the film’s intent is to try and understand how Newtown, Connecticut, is recovering four years later—to examine how, if at all, a community might process such a horrific event. But for viewers, its purpose is simpler. To watch it is to suffer through something again, perhaps even more acutely than before. And that seems to be Snyder’s goal: to assert that something this unspeakable—the mass murder of children—shouldn’t be forgotten. To find it bearable is to normalize it, and to normalize it is to accept the possibility that it might happen again.

This isn’t to say that Newtown is gratuitous, or excessive in its appeals to audiences on an emotional level. It isn’t interested in rehashing the explicit details of what happened, or reinvestigating anything (the shooter is never referred to by name, and considered only briefly). Instead, Snyder focuses on the people most affected by that day: the parents of children who were killed, the police officers and EMTs on the scene, the religious leaders and doctors left trying to heal impossible injuries. She also considers, with thoughtful care, the guilt of the parents whose children survived. In the movie’s most heart-rending scene, early on, the camera hovers over an idyllic neighborhood street while superimposed text reveals emails from frantic community members. Parents communicate that their kids are OK. Then a single word: “Guys.” There’s a pause, followed by the rest of the message. “I’m so sorry to say our sweet little angel Daniel did not make it out.”

“Daniel” is Daniel Barden, who was seven years old when he was killed. His father, Mark, is one of the film’s primary subjects, along with Nicole Hockley, the mother of Dylan Hockley. Snyder also interviews Rick Thorne, a janitor at Sandy Hook, Laurie Veillette, a volunteer EMT, and Father Robert Weiss, a Catholic priest, among many others. Each subject seems almost baffled by the scale of the tragedy, as if it’s in an order of magnitude that can’t be fully comprehended. Parents talk about making spreadsheets to keep track of 26 individual funeral services and wakes. An emergency-room doctor from Newtown describes how most of the victims were so badly wounded they didn’t even make it to the hospital. “When you have such horrific injuries to little bodies, that’s what happens,” the doctor says, visibly shaking. A bullet of the kind used by the shooter “explodes through the body, it doesn’t go in a straight line. It goes in and then it opens up.”

Snyder weaves together on-camera interviews, archive footage from home movies, and aerial shots of the town to present a compelling portrait of a community struck by the unimaginable. She films teachers from the school having a kind of potluck meeting that has all the familiarity of a book club, or a PTA dinner, which makes the fact that they’re coming together to discuss their trauma all the more poignant. And she deftly manages the tricky task of not sensationalizing the events in any way, capturing their emotional impact without veering into voyeuristic territory. “I don’t think that any of us feels like people need to know specifically what we saw,” says Bill Cario, a police officer who arrived on the scene that day. “Emotionally they need to know, to understand it, but I don’t think they need to know graphically what occurred in there.”

There isn’t anything hopeful or cathartic in the kind of pain that comes with hearing people talk about the worst day of their lives. What makes watching Newtown bearable, though, is that it feels like the closest thing to a tribute audiences can pay to the children and adults who died, and the town that continues to grieve them. To want to forget what happened that day is understandable, but the only way anything remotely hopeful can emerge from it is if we remember. “There is no closure,” Nicole Hockley says toward the end of the film. “I don’t want closure. How could I ever possibly say, ‘I’m over this now’?” But she accepts her son’s legacy, and that she has to be the one to fulfill it. That mission isn’t one that offers the luxury of forgetting and moving on. Not for Hockley, and, Newtown hopes, not for America.

Atlanta's Brilliant Reckoning With Money

Atlanta, FX’s finely detailed and gloriously unpredictable comedy about striving within and near Atlanta’s hip-hop scene, waited until the very final moments of its first season’s final episode to feature the godheads of Atlanta hip-hop: Outkast. Walking alone at night, the protagonist, Earn (played by the show’s creator, Donald Glover), puts on his headphones and listens to the duo’s 1996 single “Elevators (Me & You).” A dry, minimal beat gives Earn’s journey rhythm as André 3000 describes his rise in the rap world. Earn arrives at a storage yard, opens the door to one of the units, walks in, turns on a light, lays down on a futon, and pulls $200 out from his sneakers. Andre raps this:

True, I've got more fans than the average man

But not enough loot to last me

To the end of the week, I live by the beat

Like you live check-to-check

If it don't move your feet then I don't eat

Over the course of its 10-episode season, Atlanta has repeatedly shifted shape, driven less by plot than by its creators’ restless creativity. But one constant and crucial element has been the notion of not having enough loot to last to the end of the week. The stakes of so many of the show’s situations—whether about dating, drug tests, rap lyrics, jail, nightclub adventures, mansion soirées, or an inexplicably black Justin Bieber—has been in the question of whether the outcome would help ease the characters’ barely disguised financial desperation or only make it worse. In the context of TV sitcoms’ well-documented fondness for people who can afford spacious urban apartments or well-appointed suburban homes, this is one way Atlanta stands out. In the context of wider American social and racial conditions, it’s one reason why the show has come to seem so relevant.

The quietly magnificent season finale took the show’s long-running motif of money troubles to a new, moving place. Earn wakes up in the aftermath of a house party and realizes his blue bomber jacket is gone, kicking off a quest to regain it. Why does he need his coat back so badly? He doesn’t say, but by this point in the series, we know he can barely afford a restaurant dinner—losing outerwear, the viewer might assume, isn’t an option. But it turns out he’s in even direr straits than it first seemed. It’s only later in the episode that it’s revealed he believed the jacket contained the keys to his storage unit. And only at the very end of the episode do we realize that that storage unit is Earn’s home.

The day of searching is filled with reminders of not only his near-empty wallet but of the wallets of those around him. As Earn staggers away from the scene of the party, he passes people dressed as cows—a typically surreal image for Atlanta, but one grounded in the chilling reality that one day a year Chick-fil-A will give you a free sandwich if you dress like a bovine. At the strip club he visited the previous night, he can’t get in to look for his jacket unless he pays a $10 cover—and once he does he has to negotiate with a stripper thirsty to be cast in a music video. In his cousin Alfred’s Snapchat story, he relives the previous night of drunkenness in which he threw dollar bills around and sang along to Nelly’s “Ride Wit Me” (“hey, must be the money!”). Then he calls his Uber driver, who turns out to have the jacket, but will only come return it for $50.

At the height of Earn’s frustration, his friend Darius tells him to stop worrying about spending money. He says black peoples’ problem, in fact, is that they’re too worried about not spending money. Earn is not amused, even though Darius is describing the same craving for dignity that Earn has shown in apparently hiding his homelessness from others in his life.

The Uber saga leads to one of the most shocking and strange moments of the series when Earn, Alfred, and Darius go to meet up with the driver but find themselves in the middle of a police stakeout. The cops pull over the trio and begin to frisk them, but then their Uber driver emerges from a house, running away. He’s the one the cops want. They shoot him to death.

It’s a classic Atlanta moment where the show’s flair for Seinfeldian bleak nonsense meets its social relevance, realism, and racial consciousness. Earn, Alfred, and Darius seem to mostly keep calm as the cops point guns at them and pat them down; the larger national context of police brutality against black people comes from the viewer, who has to be frightened that this encounter could go fatally wrong. And it does go fatally wrong, but for someone we’ve never met. Earn sees the driver running, realizes he’s wearing his jacket, and then it’s bang-bang-bang—a moment of horror and comedy at once. The dead man’s loved ones—a woman and a child—come outside and begin bawling, while Earn presses an officer to check the jacket pockets on the corpse.

Afterwards, Alfred and Darius agree that the encounter was “crazy” but also “cool.” If they’re deeply shaken, they don’t let on. This sort of peril is a fact of existence for them. Life goes on.

Earn’s low-key desperation all along makes it so when payday comes, it’s an almost gutting feeling of relief.

Counterintuitively, the emotional climax of the episode comes not from this eruption of violence but from a quiet moment between cousins, when Alfred hands Earn a wad of cash. It’s his management fee. While the show’s previous nine weeks certainly hadn’t felt like a linear story of sweating for a paycheck, it suddenly crystallizes into a narrative of Earn hustling—booking TV shows, club appearances, charity PR efforts, and in this finale, a tour. Such is life, less a straightforward A-to-B journey than a collection of events that only gain shape in retrospect. Earn’s low-key desperation for cash all along makes it so when actual cash appears, it’s an enormous—almost gutting—feeling of relief.

He then heads to hang out with his daughter and her mother, Van, with whom he seems to have rekindled a romance after a harrowing encounter with socialites in the previous episode. He gives most of the cash to her, and she replies that he’s a good dad—a long-sought title that, it’s clear here, is related to money. Earn’s coworker from the airport comes to the door and asks if he’ll be at work the next day; we’ve not seen him at that job since episode one, but Earn says yes. Van offers to let him stay the night, but Earn declines and heads to his storage unit, apparently determined to prove he’s providing for himself.

It’s a hopeful ending but not a happily-ever-after: Earn’s further along than where he was before, but where he was before was further back than anyone realized. The trope of glory through hip-hop isn’t on offer here, and neither is the American Dream of decisively conquering your conditions. Andre said it best—now and forever, if you don’t move your feet you don’t eat.

Mel Gibson Is Not Sorry

“Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world,” Mel Gibson, drunk and angry, muttered to a police officer on the evening of July 28, 2006. It was a comment that would make the famous man, for several years, infamous, but it was by no means the only evidence that darkness might lurk behind that wide Gibsonian grin. The actor and Oscar-winning director has also been recorded making disparaging remarks about Latinos and African Americans (guess which words he used for each?) and about gay men. He fumed, after the journalist Frank Rich criticized his film The Passion of the Christ, that “I want to kill him … I want his intestines on a stick … I want to kill his dog.” Gibson called a female police officer “sugar tits.” He referred to an ex-girlfriend as a “pig in heat.” He hit her. And then he told her, “You fucking deserved it.”

Gibson, on the occasion of his new film, Hacksaw Ridge—his first directorial effort in 10 years, and the one meant to mark his official re-entry into Hollywood’s warm embrace—is currently engaged in the publicity tour that any such movie will demand. Only this one, under the circumstances, doubles as an apology tour, one designed not just to generate buzz for the film, but also to test the American public’s vaunted capacity for forgiveness.

One strategy, it seems, that Gibson and his long-suffering PR team have come up with to lubricate public pity is to emphasize the role that forgetfulness plays in the “forgive and forget” equation: to wash away the lesser-known of Gibson’s offenses, distilling his mistakes down not to the violence or the racism or the misogyny or the homophobia, but rather to the thing on display that night in 2006: the anti-Semitism. “One mistake” and “one bad night”—indeed, one “nervous breakdown”—have run like refrains as Gibson has embarked on his tour. They echoed even as Gibson made an appearance, on Tuesday, on the late-night show of his fellow affable charmer, Stephen Colbert.

Colbert went out of his way to offer Gibson a chance to publicly wrestle and reconcile with his past.

In Colbert, Gibson might have had a particularly sympathetic audience. Colbert, like his guest, is Catholic; the man who teaches Sunday school in his spare time has been known to use his nationally broadcast platform to discuss matters of theology and dogma—and, with them, matters both of sin and forgiveness. And Colbert, indeed, went out of his way to offer Gibson a chance to publicly wrestle and reconcile with his past, and, in that, to demonstrate the ways he has made himself worthy of the public’s forgiveness. During “Big Questions with Even Bigger Stars,” a cheeky introductory segment that called to mind Colbert’s skit with Michelle Obama—this one featured the host and the star lying down and talking as they stared dreamily up toward the heavens of the Ed Sullivan Theater—Colbert asked Gibson, “Hey, Mel-Mels? When you look back on your life, do you think you’ll have any regrets?”

“No,” came the reply. “Not one.”

The audience laughed at this, knowing enough about Mel-Mel’s past to understand that it was meant to be a laugh line.

“Really? Not one?” Colbert persisted.

“No, not one,” came the reply. The audience laughed some more.

Soon, though, they moved on to the real “elephant in the room.” After an obligatory joke about the bushy beard Gibson has been sporting of late (it’s for another movie he’s shooting, The Professor and the Madman, because Hollywood has already, it seems, forgiven him on behalf of everyone else), Colbert turned to the matter at hand. “How are you doing?” the host asked his guest, gently. “You had some rough patches over the last 10 years.”

“Yeah, rough patch,” Gibson said. He used the singular.

“And how was that?”

“Not my proudest moment,” Gibson replied, again singularizing. “Not my proudest moment, Stephen. But, you know, 10 years go by, I worked a lot on myself, I’m actually happier and healthier than I’ve been in a long time. So that’s cool. And”—Gibson barely took a breath between the two thoughts—“I’m fortunate, you know.”

“How are you fortunate?”

Related Story

Can Ryan Lochte Redeem Himself on Dancing With the Stars?

“I get to do what I love to do,” Gibson replied. “I get to do that—I’m grateful. I get to tell stories. So that’s good.”

This was not the kind of response you might expect from someone who’s had 10 years to think about what he might say to the world on behalf of his many well-documented mistakes. So Colbert tried again. “Now, you’re a Catholic, and I’m a Catholic,” the host said, going on to explain their shared religion’s conviction that suffering can, in its way, offer a means to self-improvement. “Did you learn anything from that,” came Colbert’s extremely leading question, “and”—here Colbert actively goaded his guest into self-reflection—“did you become a better man in any way?”

And then things got weird. Very, very weird.

“Yeah,” Gibson replied to the question of whether he had become a better man through the scandals: “gravel-rash suffering. Well, less time in the meat rack after it’s all done, right?”

“I don’t know what that means,” Colbert replied.

Gibson laughed, rather maniacally. He offered no clarity on the matter of the meat rack.

“That must be Australian Catholicism,” Colbert said. Then he tried again: “What does ‘less time in the meat rack’ mean?”

“Meat rack in another realm,” Gibson replied, purring his words dramatically.

“Oh, like purgatory,” Colbert said.

“Yeah, that’s it!”

“Oh, temporary suffering before we have the presence of God.”

“Yeah,” Gibson said: “temporal punishment before the main course.”

Colbert tried to give Gibson yet another chance to do what he had come there, ostensibly, to do: to express regret, to demonstrate self-improvement, to make a case for pubic forgiveness. To, at the very least, recite the talking points his publicists must have provided for him. “Was there a moment,” Colbert asked, trying a different tack, “when you thought, ‘Okay, I’m gonna get through this’?”

“Yeah!” Gibson replied. He did not elaborate.

Colbert followed up: “What was that moment, Mel Gibson? Was there a moment where you could say, ‘Okay. this is gonna be okay’? People are going to accept the apology and we’re going to move forward’?”

“Just when I apologized, I think,” Gibson said, rapidly stroking his beard, and referring ostensibly to the statements he made in 2006, to the Jewish community. “And, you know, you take a hiding. And that’s okay. But it’s interesting—”

“You’re saying you took to hiding?”

“No, you take a hide-ing.” At this, Gibson pantomimed a whipping motion over his chest and back.

“Oh, you take a hide-ing.”

“Yeah. A beating!”

“Oh, okay,” Colbert said. “Yeah.”

Gibson continued:

“So, you know, you take the shots. You try not to yell too much. You be manful about it. Don’t react too much. You know, it’s interesting. But it’s a moment in time. It’s a pity that one has to be defined with a label from, you know, having a nervous breakdown in the back of a police car from a bunch of double tequilas, but that’s what it is. Now, you know, this is not—that moment shouldn’t define the rest of my life.”

And there it was again. “A moment in time.” “That moment.” Singular. Softened. Evidence not of repeated bigotry and violence, but rather, simply, of one bad night. And who, come on, hasn’t had one of those?

In Catholic practice, divine forgiveness demands that most human of things: simply admitting that you screwed up.

And, at this, the crowd erupted into cheers. It was the closest thing to an apology, they seemed to realize, that Mel Gibson was going to give them.

Colbert seemed to realize the same. “No, I don’t believe any person—no person is their worst moment,” the host replied, as the crowd cheered again, and the notion of the single mistake settled even more neatly into the narrative.

Colbert was right, of course. The crowd was right, too. We are all better, certainly, than we are at our worst. No one deserves to have a lifetime of human interaction distilled down to individual mistakes. But it’s remarkable as well that, 10 years after the fact, Gibson has undertaken what would otherwise seem to be a classic apology tour without seeming to have any intent of actually apologizing. Instead, he defended himself. He pitied himself. He has never taken any action, he insisted to Colbert, that “ever supports that label they put on me.” He added: “It’s just not who I am, so.”

That, at least, was a well-worn talking point. As Gibson told USA Today in an interview this week,

None of my actions bear that sort of reputation, before or since. So it’s a pity, after 30 or 40 years of doing something, you get judged on one night. And then you spend the next 10 years suffering the scourges of perception.

One night. And then you spend the next 10 years suffering. Note who the victim is in Mel Gibson’s assessment.

Gibson added,

People are tired of petty grudges about nothing, about somebody having a nervous breakdown (after) double tequilas in the back of a police car. Regrettable. I’ve made my apologies, I’ve done my bit. Moved along. Ten years later. Big deal.

It’s a sentiment he has suggested before. (To The Hollywood Reporter, in 2014: “It’s behind me; it’s an eight-year-old story. It keeps coming up like a rerun, but I’ve dealt with it and I’ve dealt with it responsibly and I’ve worked on myself for anything I am culpable for.” He added: “All the necessary mea culpas have been made copious times, so for this question to keep coming up, it’s kind of like ... I’m sorry they feel that way, but I’ve done what I need to do.”)

He makes a fair point. What more can he do but apologize?

And yet that, in the end, is precisely the problem: Mel Gibson hasn’t, really, apologized. He has given statements. He has said some words. He has, to his credit, checked into rehab. But Tuesday’s appearance, with all its talk of “meat racks” and “hide-ing” and, ultimately, Mel Gibson’s own suffering, was a reminder of how little sorry-saying the star has actually engaged in.

Gibson sat down with a host who, perhaps like many Americans, seemed desperate to forgive him. If only he would just—truly, actually, fully, honestly—apologize. And Gibson, finally, would not. In common Catholic practice, the sacrament of Penance requires one first to list, vocally, one’s sins, the idea being that even that most transcendent of transactions—divine forgiveness—demands that most human of things: simply admitting that you screwed up. But Gibson, depicter of the crucifixion of Jesus and, perhaps sometime soon, also of the resurrection, could not, on Colbert’s easy chair, enact his own version of that sacrament. Instead, the disgraced star underplayed his mistakes, wallowed in his own suffering, and then offered that classic answer of those who are, finally, #sorrynotsorry: I apologize that you are upset.

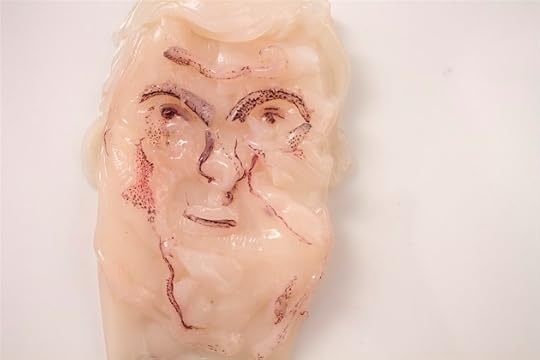

Donald Trump, Circus Peanut

“I laugh because I must not cry,” Abraham Lincoln said. “That is all, that is all.”

The artist Lauren Garfinkel knows that all too well, which is why, as the 2016 campaign has stretched far beyond the calendar year that was supposed to contain it, she has found a way to embrace mirth: via Circus Peanuts. And salmon. And baby carrots. Garfinkel has been steadily producing a series of food-based sculptures—usually portraits of the campaign’s primary figures—and documenting them on her Instagram feed, @ediblegovernment (and on the website of the same name). Her creations are Lincoln’s observation, essentially, only with a dollop of hair-hummus.

Garfinkel doesn’t have a culinary background; she trained at the Rhode Island School of Design, and by day works in fashion and textile design. Edible Government offers, for her, a kind of qualified catharsis: It’s civic engagement and escapism at the same time. Its works are generally quite partisan—Garfinkel first got the idea to experiment with food, she told me, in the aftermath of George W. Bush’s “heckuva job, Brownie”—and often feature punny titles. (One version of Trump, fabricated by elements of Chinese take-out foods, is titled “Take Out Trump.” And Garfinkel has also created works titled “Disenfranchfries,” “Putinesa,” and “History Reheats Itself.”)

Food being what it is, Garfinkel has to work fairly quickly to complete each project; each one takes, she told me, multiple hours to produce, but is usually finished within a single day. And there’s very little food whispering involved in the process: She usually starts with the idea she wants to convey in each piece, and then finds the food item or items that will help her to realize it. (Some pieces require more thought than others: For Trump-as-sashimi—on display, as are many of her other ones, at Lucky Peach—Garfinkel says, “the fish itself, for that hair, it just kind of had the texture on it. That’s what I call a gimme.”)

Garfinkel’s projects operate in the tradition of Sandwich Monsters and Harley’s Food Art: works that are absurdist and delightful and edible. But they’re all that, while also making a point. She approaches each work, Garfinkel told me, “just thinking about how we are all connected to our individual choices that have this great impact, and we have to have ownership of our choices.” It’s the Michael Pollan idea, basically—food as politics, and vice versa—taken to its logical (and literal) conclusion.

And so, with that, the 2016 campaign—as food:

1. Donald Trump, composed of sashimi

Lauren Garfinkel

2. Hillary Clinton, composed of fruits

Lauren Garfinkel

3. Trump and Vladimir Putin, composed of blini

Lauren Garfinkel

4. Bernie Sanders, composed of gum

Lauren Garfinkel

5. Trump, composed of a Circus Peanut

Lauren Garfinkel

6. Trump, composed of fondant

Lauren Garfinkel

7. Ted Cruz, composed of turkey

Lauren Garfinkel

8. Marco Rubio, composed of canned goods

Lauren Garfinkel

9. Jeb Bush, composed of baked potato

Lauren Garfinkel

10. Trump, composed of baby carrot

Lauren Garfinkel

11. Clinton, composed of mushrooms

Lauren Garfinkel

12. Trump, composed of mushrooms

Lauren Garfinkel

13. Sanders, composed of mushrooms

Lauren Garfinkel

14. Trump, as a pig-in-a-blanket

Lauren Garfinkel

15. Trump, composed of candy

Lauren Garfinkel

16. Newt Gingrich, composed of squid

Lauren Garfinkel

17. Chris Christie, composed of squid

Lauren Garfinkel

18. Mitch McConnell, composed of squid

Lauren Garfinkel

19. Paul Ryan, composed of squid

Lauren Garfinkel

20. Reince Priebus, composed of squid

Lauren Garfinkel

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower