Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 44

November 17, 2016

Fantastic Beasts Charts a New Path Through a Familiar World

“Anything edible in there?”

The query, by a 1926 New York City customs official, is directed toward a somewhat befuddled British arrival with a shock of red hair who goes by the name Newt Scamander. And truth be told, there is nothing in the valise in question that I imagine anyone in his or her right mind would want to eat.

The suitcase does however contain: a nifler (a platypusial creature with a fondness for snatching shiny objects); an erumpent (rhino-like when it comes to size and temperament and, inconveniently, in heat); several occamy (winged serpents with an aptitude for size-shifting); a demiguise (simian, and blessed with powers of invisibility and precognition); a thunderbird (pretty much what is sounds like, only larger); and a variety of other, shall we say, fantastic beasts.

And I suppose we might as well say that, because the title of the film is Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. A spinoff of J.K. Rowling’s universe-transcending Harry Potter series, it is very loosely based on a fictional “textbook” of the same name that Rowling published in 2001. The conceit of the movie is that Newt (Eddie Redmayne) is in the process of compiling said textbook by collecting and cataloguing various magical fauna. Or, as he himself describes his mission: “Rescue, nurture, and protect them. And gently try to educate my fellow wizards about them.” Picture a Hogwartian Dr. Doolittle and you won’t be far off.

Alas, shortly after his arrival stateside, Newt mixes up his suitcase with that of a No-Maj—this is the American term for “muggle,” or non-magical individual, we colonials being rather more literal than our British cousins—named Kowalski (Dan Fogler), an amiable cannery worker who aspires to open a bakery. Inevitably, several of the creatures escape and begin causing minor mischief in Manhattan.

But they are not the only otherworldly beings that are afoot (a-claw? a-wing?) in the city. Something far more powerful and sinister has been tearing its way through the pre-war buildings and cobbled streets, in the process setting the local wizard higher-ups—played by Carmen Ejogo and Colin Farrell—on high alert. Worse still, an anti-witchcraft movement, the “Second Salemers,” is on the march. The stage is set for a civil war between the magical and No-Maj communities, a civil war it appears someone may be secretly trying to stoke.

So it falls to Newt to restore the missing beasts to his luggage—which, like Dr. Who’s TARDIS, is much larger on the inside than it is on the outside—while also persuading everyone that he is not the would-be war-stoker. In these tasks he is aided by an unlikely trio: the No-Maj Kowalski; Porpentina “Tina” Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), a sympathetic investigator for the Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA, which whether or not by coincidence is pronounced an awful lot like “yakuza”); and her kind but flighty sister, Queenie (Alison Sudol).

To its considerable credit, Fantastic Beasts is not the Potter retread it could easily—and very profitably—have been. There are echoes, of course: MACUSA bears a notable resemblance to the Ministry of Magic, and the script, by Rowling herself, features one or two pleasantly Rowlingesque reversals. But overall the film charts a new path through familiar magical terrain. Instead of schoolchildren learning their craft, the protagonists here are fully formed wizards—with the exception of Kowalski, the No-Maj, who is himself a welcome addition.

Fantastic Beasts demolishes the 1926 Big Apple as comprehensively as The Avengers did the 2012 version.

And of course, we have traded a Hogwarts tucked away in the Scottish Highlands for the urban bustle of pre-depression New York. This Americanization of the Potter canon is no doubt smart business. (Likewise, the presence of so great a volume of toy-ready beasties.) But for the most part the new setting is refreshing, with period details lovingly applied by the movie’s director, David Yates, who also helmed the last four Potter movies. If there’s a flaw in the transatlantic translation, it’s that it seems also to have entailed a customarily overwrought CGI climax, in which Fantastic Beasts demolishes the 1926 Big Apple as comprehensively as The Avengers did the 2012 version.

Apart from that, the film’s largest shortcoming is that it feels like three hours of material squeezed into a two-hour running time. And while this was true of most of the Potter films as well, they at least had the books to lean upon for anyone inclined to take a deeper plunge. There are numerous elements here that could have used further unpacking: the plight of the wretched children enlisted into the Second Salemers by the group’s fanatical leader (a sorely underutilized Samantha Morton); a wafer-thin storyline involving a newspaper magnate (Jon Voight) and his two sons; and a charming but slight romantic subplot between Kowalski and Queenie.

But even if the characters are somewhat underdeveloped, the cast does what it can to bring them to life. Redmayne is excellent as the committed but awkward magizoologist Newt, his eyes shying away from direct contact whenever possible. Fogler (Balls of Fury) is lovably lunky as Kowalski, and singer-songwriter Sudol is an unexpectedly charismatic presence as Queenie. Among the principal quartet, only Waterston’s Tina fails to make a deep impression, and this is a consequence more of the script than of her performance.

But never fear. There is time enough ahead (and more) to get to know these characters, to learn about Newt’s mysterious past love and discover whether Queenie and Kowalski have romance in their future. Originally proposed as the opening chapter of a trilogy, Fantastic Beasts has already been upgraded to serve as the first of a planned five-movie series. What could be more American than that?

November 16, 2016

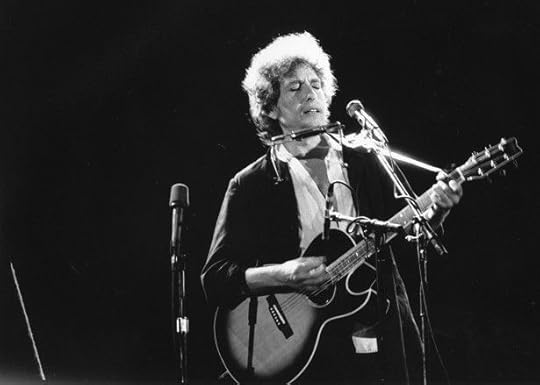

It Pays to Be a Jerk, Bob Dylan Edition

Last month, the Nobel Committee announced that it had awarded Bob Dylan its prize for literature. Amid the speculation that ensued—are song lyrics literature? what is literature? what is the Nobel Prize for?—another thing, a much pettier thing, took place: Bob Dylan proceeded to totally ignore the Nobel Committee. Voicemails went unanswered. Emails went un-replied to. “Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature” was briefly added to Dylan’s website, then quickly removed. A member of the Nobel committee, frustrated, called Dylan “impolite and arrogant.” The whole thing was awkward and weird and a timely reminder that even the echelons of art and culture are occupied by humans and their lizard brains. Here was Emily Post’s worst nightmare, played out on a global scale—albeit with many, many “his answer is blowin’ in the wind” jokes thrown in for good measure.

Wednesday, it turned out, brought a new twist to what The New York Times has taken to calling “the saga of Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize”: Dylan, it seems, finally communicated with the Nobel committee—to inform them that he will not,in fact be attending the prize ceremony with his fellow laureates. Which is, in the end, not at all surprising. After all, this kind of thing is what Dylan does, as an artist and a person. He’s a “screw the establishment” kind of guy; ironically, that political positioning is what helped him to win the Nobel in the first place. And it’s how members of the media have justified his behavior on his behalf. “‘That’s just Dylan being Dylan,’” James Wolcott, a columnist for Vanity Fair, tweeted about the whole episode. “You could substitute any egotist’s name in that formulation.” The Telegraph noted of the erstwhile radio silence that Dylan “always does the unexpected.” The Guardian praised his “noble refusal of the Nobel prize for literature.” The New York Times compared Dylan, in his reticence, to Jean-Paul Sartre, who himself famously declined his own Nobel in 1964. And then the paper declared that Dylan’s behavior “has been a wonderful demonstration of what real artistic and philosophical freedom looks like.”

Here was Emily Post’s worst nightmare, played out on a global scale—albeit with many “his answer is blowin’ in the wind” jokes thrown in.

Noble! Philosophical! Wonderful! The other way to see things, however, is that Bob Dylan has simply been acting, if you’ll allow me to put it very poetically, like an enormous and overgrown man-baby, refusing to acknowledge his being awarded one of the most prestigious prizes in the world in a way that manages to be both delightfully and astoundingly rude. Perhaps, sure, Dylan has done all this on principle. Perhaps he has been, with his preemptive ghosting, trying to make a point. The trouble is that until today, all anyone could do was speculate about his intentions, because Dylan had simply refused to engage in that most basic transaction of civil society: to send an RSVP. He may have been embracing the role of renegade/rebel/independent artist; he was also, however, embracing the role of a jerk.

It’s striking, all in all, how readily he has been rewarded for that. Dylan is noble! He’s principled! He’s just like Sartre! Hell, as Dylan’s fellow semi-laureate suspected, may well be other people; it’s notable, though, how much more hellish other people can be when they fancy themselves too fancy for basic courtesy. And it’s even more hellish when the people at the culture’s echelons—the ones we look up to, the ones we celebrate, the ones whose songs we sing—are the same people who can’t be bothered to pick up a phone when it rings, or to give a simple “sure!” or “no, thanks” when offered an honor on behalf of the world.

There are many people in that group—the vaunted jerks, the ascendant assholes, the men (it is, alarmingly often, men) who flout basic conventions of courtesy and respect, and who are then rewarded for it. There’s Steve Jobs, about whom it was written, after his death, “Steve Jobs Was an Asshole, Here Are His Best Insults” and “Steve Jobs didn’t care if people thought he was an asshole. Why should we?” and “Steve Jobs Was A Jerk. Good For Him.” There’s Elon Musk. There’s Mel Gibson. There’s the country’s new president.

Related Story

There’s a sliding scale in all this, certainly. Some of them are actively bad: Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin and Thomas Edison were wonderful to humanity, but occasionally terrible to its individual members. Today, for the most part, we turn a blind eye to their interpersonal failings, preferring instead to judge them in the gleam of history. But what’s in some ways even more worrying is the accumulation—the celebration—of small slights, shortcomings that are not obviously immoral so much as they are … sloppily inconsiderate. The Dylan-like situations that find celebrities being celebrated specifically for their jerkiness—as if their assholery doubles as a kind of bravery. As if they fail to follow the mandates of civic decency not because they are ignoring those rules, but because they are transcending them.

It’s the logic that helped to cement Lyndon Johnson as a political legend. (Did you hear about the toilet thing? Or, lol, when he ordered those pants?) It’s the logic that has helped to ensure that Steve Jobs will remain a kind of secular prophet. It’s the logic that sees Donald Trump as, above all, a truth-teller, loved by his legions of fans for “telling it like it is.” The Atlantic, last year, ran a long, research-based feature on those people. It was called “Why It Pays to Be a Jerk.” There are, it will probably not surprise you, many—so many—of those reasons.

And so here is Bob Dylan, being not actively Bad but rather, more simply and more confusingly, rude. And here he is, being celebrated for it. “There is a good deal of poetic justice in this turn of events,” the Times enthused. And “for all the speculation over the last two weeks about the reasons behind his blanket silence on the Nobel award,” The Telegraph put it, “I can only say that he is a radical personality—which is why he has remained of so much interest to us over six decades since he first emerged on the Manhattan music scene in 1962—and cannot be tied down, even by the Nobel Prize committee.”

There was one group, however, who was less breathless about Dylan’s recent antics. The Nobel committee, in announcing that Dylan would not come to the party they will be throwing in his honor, offered an abundance of kind words about the artist and the prize he is being awarded. “He underscored, once again, that he feels very honored indeed, wishing that he could receive the prize in person,” the committee noted. The committee’s frustration, however, shone through, even in an otherwise standard press release: “We look forward to Bob Dylan’s Nobel Lecture, which he must give—it is the only requirement—within six months counting from December 10, 2016.”

An Outsider's Bid for the French Presidency

Emmanuel Macron announced Wednesday an independent, centrist bid for the French presidency, throwing his hat into a competitive ring that is seeing tight primaries in both the center-left and center-right parties.

In a speech in Bobigny, a Paris suburb, Macron, a former protege of François Hollande, the deeply unpopular Socialist president, called for a “democratic revolution,” vowing to move the country away from what he called an obsolete and clan-based political system.

“This transformation of our country is not a fight against someone, against a camp, against a part of France. It is a struggle for all of us, for the general good, for our children,” Macron said, calling for unity between the left and the right. “I can only carry it out with you.”

Macron is an outsider. The former investment banker was virtually unknown in French politics before 2014, when he was appointed the minister of economy, industry, and digital affairs by Prime Minister Manuel Valls. During his two-year tenure, Macron branded himself as business-friendly, pushing several business reforms aimed at boosting economic growth through his Macron Law. Despite his brief stint in Hollande’s socialist government, the 38-year-old is not a member of any political party, nor has he ever held elected office. It is this separateness that Macron capitalized on when he resigned from the Cabinet in August to launch his own centrist political movement En Marche!, or “Forward.”

The nascent party faces a tough test as it goes up against the French establishment. On the center-right, Macron pits himself against Alain Juppé, the former prime minister who in an Opinionway poll this week leads both former President Nicolas Sarkozy, and François Fillon, the former prime minister, by 8 percentage points. On the left, Macron could face Hollande, who, faced with slumping approval ratings, hasn’t yet announced whether he will seek a second term. Macron could also face his former boss, Valls, who previously dismissed him as promoting “populism-lite.”

If Macron is representing himself as an alternative to France’s establishment politicians, he certainly is not alone. Marine Le Pen, the head of France’s far-right National Front, has positioned herself as a contender to represent France’s populist sentiments, calling the victory of Donald Trump in the U.S. presidential election “a sign of hope.” Le Pen, however, did not appear fazed by Macron’s announcement Wednesday, calling him a “banks’ candidate” who “will not be stealing any of our voters.”

Although it’s unclear how Macron would fare in an actual election, an Elabe poll following his resignation from the Hollande government in August found that 34 percent of voters wanted the former economy minister to make a presidential bid. An Ifop poll from that same period showed that 47 percent of voters wanted Macron to run.

Pop Culture Resents ‘The Establishment’ Too

Dave is a peculiar movie. It’s a fairy tale at its core—a Cinderella story, only with the princess who’s rewarded for her patience and kindness being, in this case, a middle-aged guy named Dave. The film goes like this: Dave Kovic (Kevin Kline) runs a temp agency outside of Washington, D.C. Because he bears an uncanny resemblance to the sitting president, William Mitchell, Dave is tapped to stand in for Mitchell as he’s leaving public events and whatnot, for “security” purposes. But then, one evening, Mitchell has a stroke, and suddenly the president’s body double—on the advice of administration officials who don’t see a coma as a reason to relinquish their hard-fought power—finds himself playing the role of … the actual president. Yes, of the United States.

Are you ready for the extremely predictable spoiler? The outsider—the guy who has no political training at all, and who’s never run for office, let alone been elected to one—ends up being a much better politician than the man who was duly elected to the presidency. Bill Mitchell is cold and calculating and criminal and (even worse, in the movie’s eyes) uncaring about the needs of ordinary Americans; “Bill Mitchell,” though, is compassionate and dedicated. He’s also really fun! He likes performing! He does the hula with a robot at a factory as the workers cheer him on! He does, in the end, the thing that politicians so often claim they do: he cares about people’s lives. Dave, the movie named for him argues, is constitutionally, if not Constitutionally, fit to govern the nation. He is good at politics precisely because he is not, in any of the ways that end up mattering, a politician.

Dave is constitutionally, if not Constitutionally, fit to govern. He is good at politics, in the end, because he is not, really, a politician.

Dave, an otherwise airy confection of a movie, manages nevertheless to articulate one of the most enduring paradoxes of American political life: the simmering assumption that the only way to succeed in politics is to avoid, when at all possible, actually becoming a politician. In the earliest days of the Republic, campaigning—and, really, any declaration of one’s intention to represent the people at all—was considered improper. You didn’t seek office; office, the logic went, should instead seek you. It was a vestige perhaps of a system that assumed that leaders were selected for mortals by the hand of the divine, but it’s an idea that lives on in contemporary pop culture, whose products, for decades, have both celebrated the Dave-style outsiders and, at the same time, resented them. Movies and TV shows may be fantasies and fairy tales and fictions, but they also prime people in their approach to a world that is non-fictional. In the assumptions they’ve made about the morality of politicking, movies and TV shows may shed just a little bit of light on why, in the most recent presidential election, the outsider won … and the insider was rebuked.

In the weeks leading up to the 2016 presidential election, some readers and colleagues at The Atlantic and I got together to watch a series of politics-themed movies. We called it Political Theater. My boring-but-constant takeaway from the exercise was the depth of mistrust those movies and shows had for establishment politicians, often simply on the basis of their being establishment politicians in the first place. Again and again, the films (selected by readers, for the most part, and ranging in decade from the ’70s to the aughts) took for granted three things. First, that the American political system is fundamentally broken. Second, that those who are inside that system are fundamentally part of, and to blame for, the brokenness. And, third, that the other two things being true, the only hope for redemption must come from the outside.

Related Story

Hillary Clinton, Tracy Flick, and the Reclaiming of Female Ambition

There was Dave, yes, with its Beltway Cinderella story, but there was also The Candidate, the semi-satire that found an outsider running for a California Senate seat (against an establishment opponent named Crocker Jarmon, to hint at his Peak Establishment-ness). There was Head of State, which took a similar story—the political outsider, proving to be better at politics than any establishment candidate ever could hope to be—and applied it to the highest office in the land. Even The West Wing, the ultimate endorsement of the power of political institutions, morally ratified the presidency of Jed Bartlet by making clear that his campaign for that office was also an insurgent one. Bartlet, too, was an outsider candidate. Bartlet, too, earned office by … not, in the hierarchical manner preferred by the establishment, really earning it.

The movies we watched also realize that same logic in reverse: Instead of celebrating the political outsiders, they simply assume the worst of the insiders. Wag the Dog, the dark satire of the late ’90s that is perhaps the most cynical vision ever presented of American democracy, reduces the idea that politics is pageantry to an ultimate absurdity, with its president creating a Hollywood-produced war simply to win re-election. Its fellow product of the late ’90s, Election, takes for granted the age-old idea that political ambition itself must be evidence of selfishness and moral turpitude and unfitness for office. Dave, too, takes an inside-out approach to outsiderism: Just as Dave himself is successful as a politician precisely because he’s not political, the cronies that put him in power manage to be at once obsequious and power-hungry. The “pit-vipers,” as Dave’s First Lady calls them, are so corrupt that it never crosses their minds that “puppet government” is generally understood to be an insult. Washington corrupts, gradually but absolutely.

Washington, the swamp in dire need of draining. Congress, the cesspool where nothing gets done. American government, bloated and dirty and contagious. These are themes that find reflection far beyond the handful of movies we happened to watch for Political Theater. There’s All the President’s Men, which takes as evidence for its mistrust of politicians the facts of history itself. There’s Legally Blonde: Red, White & Blonde, which finds Elle as the principled outsider fighting against corrupt Congressional leaders. There’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. And The Manchurian Candidate. And The Distinguished Gentleman. There is, on television, Veep, which rivals Wag the Dog in its cynicism about the efficacy of the federal government. And Designated Survivor, which is premised on the Dave-like idea of the relative political novice (Kiefer Sutherland) ascending to the leadership of the country, literally overnight—and (spoiler!) proving to be more principled than any establishment politician could ever hope to be.

Governing is dirty work: It demands compromising and selling out and never being, fully, satisfied.

These are, yes, fairy tales, though they’re more akin to the Hans Christian Andersen versions than to those stories’ happily Disneyfied updates. They are dark and bleak and often end in death. Some double as articulations of the political exceptionalism of ordinariness itself. Most, though, do something more basic, and more pessimistic: They assume the fundamental dirtiness of politics, and the related idea that any hope we’ll have of purifying the system must come from outside of it. They leave very little room for optimism about the hulking beast that is “the establishment,” very little room for hope that the system in place—one populated by career politicians—can take compassion and make it scale. They prefer Dave Kovic over Bill Mitchell. They prefer Jed Bartlet over John Hoynes. They prefer, yes, Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton. Not because they are partisan, but because they are biased against partisanship itself: They mistrust politics. They mistrust the system. They want, in some small but meaningful way, a revolution.

During the climactic scene in Head of State, Mays Gilliam (Chris Rock) debates the sitting vice president—and the consummately establishment politician—Brian Lewis (Nick Searcy).

“When it comes to paying farmers not to grow food, while people in this country starve every day,” Gilliam says, “yes, I’m an amateur.”

The crowd, at this, erupts into cheers.

“When it comes to creating a drug policy that makes crack and heroin cheaper than asthma and AIDS medicine—yes, I’m an amateur.”

More applause.

“But there’s nothing wrong,” Gilliam continues, “with being an amateur. The people that started the Underground Railroad were amateurs. Martin Luther King was an amateur. Have you ever been to Amateur Night at the Apollo? Some of the best talent in the world was there!”

He has a point. And it’s a point that bleeds over from pop culture into political culture. Governing is dirty work: It demands compromising and selling out and never being, fully, satisfied. “Politics as usual” may be the only way for government to work; “as usual,” though, is neither inspiring nor gratifying. That’s in part why nearly every victorious presidential candidate in recent memory has won with an outsider platform. Bill Clinton, the Southern insurgent who ran on a motto of “for people for change.” George W. Bush (“reformer for results”). Barack Obama (“hope and change”). Donald Trump, with his pledge to dismantle the system from within. Americans are, by their nature, dissatisfied with the status quo; we are impatient and indignant and convinced, above all, that the world can be so much better than it is. “A more perfect union” may be the founding paradox of American political life; it is also the most enduring one. It plays out in politics, and in pop culture—in voting booths and on screens.

Arrival's Timely Message About Empathy

This post contains spoilers about the ending of the film Arrival.

The masterful sci-fi film Arrival is ultimately a story about communication. It follows the linguistics expert Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) as she tries to connect with a race of aliens who’ve landed spacecraft all over the globe for some mysterious purpose. But Louise’s most crucial breakthrough isn’t with the seven-legged, squid-like “Heptapods” that have come to speak with humans. It’s with the Chinese government—in particular, the stoic General Shang (Tzi Ma), who brings his country to the brink of war with the aliens out of his fear that they pose a threat. In the film’s arresting climax, with the help of Heptapod technology that lets Louise simultaneously glimpse the present and future, she calls Shang and gets his attention by telling him something she couldn’t possibly know: his wife’s dying words.

In Arrival, the motivations of the visiting Heptapods are vague—they simply tell Louise they will need humanity’s help to avert a great crisis thousands of years from now. But their strange written language, when properly learned, allows the speaker to experience time in a non-linear way and access all past, present, and future moments at the same time. In bringing this language to Earth, the Heptapods are doing more than granting the planet an incredible new technology: They’re also seeding humankind with empathy, pushing them together, distributing their language in pieces to different countries and demanding they cooperate to assemble it. It’s an extraordinarily hopeful message for a particularly grim moment in global affairs, where isolationism and nationalism are on the rise in the U.S. and elsewhere.

That’s something Arrival’s screenwriter Eric Heisserer thought about when crafting his script, which was adapted from the short story “Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang. Adding the “geo-political panic element” helped him translate that small, emotional tale into something grander, Heisserer said in an interview with The Atlantic that also touched on how he crafted the enigmatic visual look of the Heptapod language and expanded the emotional thrust of his story. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

David Sims: What was the initial spark for you after reading “Story of Your Life”?

Eric Heisserer: I didn’t get any sort of cinematic reaction from the story at all. It was a total emotional connection where I just was gutted and heartbroken, while my head was just full of giant ideas. I had learned something about Fermat’s principle of least time, and Snell’s law, and non-linear orthography, and I didn’t even know what any of those terms were before reading this story. And I wanted to share that with the world. I had a lot of heavy lifting to do [on the visual side], because the story works so well as a literary piece, and doesn’t worry about the things that make a movie work.

Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) and Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner) surrounded by images of the Heptapods’ written language in Arrival. Paramount Pictures

Sims: How did you construct the Heptapods’ language when writing the script? Were you working on what that would look like from the beginning?

Heisserer: I had some of my own formally uneducated ideas about the Heptapods’ language. I dabbled as an amateur language-builder, in as much as I knew what I wanted the [Heptapod] logograms to look like. I wanted that non-linear sense. So I knew I wanted it to be circular, and I wanted questions, or any other kind of intent, to be [rendered as] modified curls and loops that emanated from the circle. I did a lot of graphic work early on, and I had maybe seven or eight different logograms I designed in the script.

Sims: Did they change at all from script to screen?

Heisserer: Oh sure, yeah. They got artists and professionals far smarter than I on board, and they took the ball and ran with it. The logograms still remain circular, some of the founding principles I toyed with are there, but the artists made sense of them. Patrice Vermette [the film’s production designer] and his wife helped design the language, and they have a fully fleshed-out language, with 100 symbols that actually make sense. The analysis you see in the film, where the symbols are run into a scanner and translated into words, that’s Vermette making it work.

Sims: How did the film differ from the short story otherwise?

Heisserer: In the short story, the Heptapods communicate simply by dropping technology called “looking glasses,” which are basically intergalactic viewscreens, over a couple hundred places around the planet. And humans have Skype calls with the Heptapods and start to learn their language.

Sims: So it’s a little more mundane.

Heisserer: It is, and there’s a real lack of conflict or tension. And I realized quite soon that if I had this movie take place over a series of nine months to a year of them just talking on TV screens, that I was in trouble. So having the Heptapods arrive [in giant ships] at our front door gave me the geo-political panic element and the rising tension of a public that would want an answer.

Sims: The geo-political panic feels appropriate to this moment in history, where everything has to be immediate, where an answer has to come right away, where there’s an importance placed on speed in everything. The thing that’s working against Louise in the movie is not how the aliens behave, but how the human structures of power are reacting.

Heisserer: Right. And this is the essence of a linguistics expert. A linguist has this essential problem to solve with people, because patience is the only real virtue in that career, and our increasing need for the immediate understanding, the knee-jerk reaction, the false equivalence, all that happens right away, and is our downfall.

Sims: A scene that really stuck out for me was the conversation between Louise and General Sheng. It felt like the lynchpin for the film’s message of understanding and communication, because we’ve only seen him as a stereotypical figure: the stern Chinese general that you see on the TV.

Heisserer: Right! And why? Because we’re seeing it through the filter of the U.S. intelligence network; it’s their version of him. We’re not seeing a person. It’s our misinterpretation of what we think China is doing. So it falls into a bit of a trope, again, simply because we’re the U.S., the military-industrial complex, whatever you want to call it. We’re think of them as a potential enemy. And we’re taking whatever’s being said in Chinese, whoever’s translating that is taking it to the U.S. news and saying, “Oh, this is the big bad general.” No. We don’t know what’s going on with him until we see him in person. We realize he’s not the character we thought him to be: He’s really honored to meet Louise, and something really poetic and personal has happened there.

For the longest time in the script, for the scene where they’re on the phone, I had just written, “She says something in Mandarin to him, and we know this is his wife’s dying words.” And I just found it lovely and poetic, and I didn’t think about it further until [the actor] Tzi Ma calls me and says, “Eric, Eric. What does she say?” And I reply, “Well, she says something in Mandarin!” And he replies, “This is the most important line in the film, this saves the world, Eric! What is the line?” So I kept bringing him ideas, and he would say, “Eric, I love you, but this is terrible.” So finally, I gave him something, and he said, “I deeply love this, this is the line, this is exactly what should be said, I will use this.” And I finally see the final cut of the film, and we get to that scene, and she says the line, and [the director] Denis [Villeneuve], the scoundrel, does not use subtitles. So nobody knows, unless you speak Mandarin, what she says to him.

Sims: So I’m going to have to get a translator? That feels appropriate.

Heisserer: Precisely.

A Tribe Called Quest and the Shadow of Trump

A Tribe Called Quest’s “The Donald,” the final track on their first album in 18 years, is not about Donald Trump. Maybe. With playful DJ scratches, jazzy keys, and patois all radiating the warmth of friendship, the song is the group’s final goodbye to its member Phife Dawg, who died at age 45 from complications of diabetes earlier this year and who had claimed the nickname “Don Juice.” Still, you don’t call a song “The Donald” and release it three days after the presidential election without knowing the implications. You don’t sample a newscaster saying “Donald” over and over again without wanting to conjure up the billionaire who in his campaign’s final days made hip-hop yet another non-white scapegoat for America’s problems. You don’t create a song like this without wanting to draw a comparison between Don Juice and The Donald, or really, in this case, a contrast.

Great albums eventually transcend the conditions that surrounded their release, and the excellent We Got It From Here … Thank You 4 Your Service, recorded over the past year, may indeed succeed at that. But first, it’s a document of its time. The hack of John Podesta’s emails revealed that the band’s brilliant frontman Q-Tip reached out to help the Clinton campaign; here, he makes multiple references to the glory of female leadership, a particularly poignant gesture now. There are plenty of other chillingly relevant lyrics inspired by the news in 2015 and 2016. And grief for the recently passed Phife (as well as his his own voice) permeates the ever-morphing funky medley even in its most joyful moments. But maybe the album’s deepest resonance, its great connection and clash with the moment, is the music itself: its celebration of intellect and teamwork, its collage of multiracial influence, its liveliness in the face of sorrow.

These virtues announce themselves in neon within moments of the album’s start, with “The Space Program” staging a verbal passaround game as balletic and energizing as an Avengers fight scene. Q-Tip and Phife Dawg work together for the chorus about working together, and then Jarobi White joins in the verses, his deep voice like a sharpie complementing Tip’s fine colored pencil. An extra layer of crisp rhythm adds in as the syllable count rises, but the display of complexity is more about emotion than technical impressiveness. “Mass un-blackening, it’s happening, you feel it y’all?” Jarobi asks. The answer has to be “yes” in the week when an election was decided by white turnout and white solidarity, but the song makes you feel the irreversibility of that outcome a little less than you would otherwise.

The album just gets more explicitly relevant from there. “We the People” lumbers in with sirens and synths before Tip mutters a chorus telling black people, Mexicans, Muslims, and gays to leave the country. The song’s title is either a statement of pessimism about our democracy or a call for unity, cemented by Tip’s observation that “when we get hungry we eat the same fucking food, the ramen noodle.” Next comes “Whateva Will Be,” whose slow-rolling funk features Phife lamenting black men being marked as lesser at birth—a sentiment especially heavy when heard from beyond the grave. It’s not the only time that words Phife recorded in life sting more now than they would have then: “CNN and all this shit why y'all cool with the fuckery?” he says on “Conrad Tokyo.” “Trump and SNL hilarity / Troublesome times kid, no times for comedy.”

Never is this protest and mourning a drag to listen to. Rather, the music embodies Tip’s coinage of “vivrant”—vibrant + vivacious—with a meld of live playing, programming, and samples that maintain a groove as the sonic palette shifts. Agitated electro sounds power the Andre 3000 showcase “Kids,” spacey reggae accompanies Tip imagining Phife’s ghost for “Black Spasmodic,” and Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets” becomes earthquaking psychedelia for “Solid Wall of Sound.” The music’s ever-searching, dot-connecting mentality fits the lyrical outlook. Toward the end of the album, Tip offers his grand humane diagnosis of the world by using the song title “Ego” to refer to the quality that motivates him in the face of disrespect but also motivates tyranny. Smart.

My favorite track of the moment is one of the more subdued ones, “Melatonin,” which could exist out of time but is all the more powerful because it doesn’t. As the band moves from stop-start-stop-start passages to smooth reveries and back, Tip raps about anxiety keeping him awake. “The sun is up, but I feel down again,” he says, and for the song’s length the only remedies are sex and sleeping pills. He’s not exactly offering solutions here; he’s offering forgiveness for feeling the need to momentarily recharge. The miracle of the album is that it’ll help listeners do just that, even as it does quite the opposite of distract from the world.

November 15, 2016

Stephen Colbert Finds Refuge in Punditry

On Monday evening, Stephen Colbert, television host and comedian, engaged in some light explanation of the political and cultural significance of the alt-right movement in the United States. Colbert, in the opening monologue of the Late Show, summarized for his audience the meaning of Steve Bannon, Trump’s newly appointed chief of White House strategy. “Bannon is considered a leader of what’s known as the alt-right,” Colbert said—“an extreme online movement with ties to white supremacy.” The comedian paused. “Here’s how to understand the alt-right: Think about what’s right, then think about the alternative to that.”

Bannon, Colbert added, for more context, “is best known for running something called Breitbart News. If you’ve never read Breitbart, it’s the news your racist uncle gets sent to him by his racist uncle.”

It was a recycled joke—“if you haven’t heard of Breitbart News,” Colbert declared in August, “that means you do not have a racist uncle on Facebook”—but one that has taken on renewed relevance now that the man who provides the news to the racist uncles of the racist uncles finds himself in a position to influence American policy. It was also a joke that hinted at what Colbert’s show will look like during a Trump administration: indignant, explanatory, vaguely journalistic, highly partisan. The stuff of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report, ported over to network TV.

On Monday, Colbert played the most powerful character of all: himself.

Late-night comedy has revolved around political humor for decades. Traditionally, though, the jokes offered up by the likes of Leno and Letterman and O’Brien were decidedly bipartisan in their flavor: They were focused on mocking those in power, regardless of their political party or affiliation. Clinton and his Big Macs, George W. Bush and his misunderestimations, Barack Obama and his dad jeans … the jokes, in general, were light of tone and bipartisan of scope, offering not just low-key lols, but also a reassurance to their audiences that things can’t be that bad, because, hey, we can still laugh, right?

Colbert, though, has long chafed—just a little—against those “please everyone, the country is big and this is network TV” mandates. Colbert is partisan. He is passionate. He is principled. And he has tried to find ways, in the year-and-change since he first became a late-night host on network TV, to combine all those truths in a way that simultaneously satisfies himself/his audience/his CBS bosses—one persona, basically, to rule them all. In that attempt, Colbert has experimented with emphatic humanism; he has taken refuge in role-playing (as The Hunger Games’s Caesar Flickerman, paying tribute to the fallen of the 2016 campaign); he has taken refuge in the past (as his Comedy Central alter-ego, “Stephen Colbert”).

On Monday, though, Colbert played the most powerful character of all: himself. He played the role of a Catholic, coastal Democrat who is frightened and horrified and still processing what happened last week. He played the role of someone who is commiserating, openly and emotionally, with his audience. He used the word “we” a lot. He took his own, and his viewers’, partisanship for granted. “Now, we are all surprised that Trump is going to be president,” Colbert said in his monologue, as the crowd cheered him on. “It’s weird. It just feels weird.”

Related Story

How Stephen Colbert Tried to Process Trump’s Victory

It was an echo of the sentiments he expressed on Wednesday, the day after the election. “You know, I’m a man of some faith,” he told his audience, then. “But when bad things happen like this—and this does feel bad—I’ve got to ask, How could God let this happen?”

He added: “We have to accept that Donald Trump will be the 45th president of the United States,” Colbert told his audience on Wednesday, the day after the election.

The crowd booed, loudly.

“No, no listen,I get that feeling completely,” Colbert said. “I just had to say it one more time … I just have to keep saying it until I can say it without throwing up in my mouth a little bit.”

Monday’s show continued that vom-com ethic—this time, though, it did it with facts and evidence. Colbert laid into Bannon. He listed, for his audience, some of the headlines that Breitbart ran while the site was under the direction of Bannon:

WHY EQUALITY AND DIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS SHOULD HIRE ONLY RICH, STRAIGHT WHITE MEN

WOULD YOU RATHER YOUR CHILD HAD FEMINISM OR CANCER?

HOIST IT HIGH AND PROUD: THE CONFEDERATE FLAG PROCLAIMS A GLORIOUS HERITAGE

BILL KRISTOL: REPUBLICAN SPOILER, RENEGADE JEW

And then, Colbert addressed the matter of fear—the fear being felt not just by people who may be deported under a President Trump, but by people of all races and creeds and genders who, at this point, have no idea what to expect from a Trump administration. Colbert made a joke about the “illegal alien” ET. But then he got more serious. “Don’t be afraid,” Colbert said, aping the message of the president-elect. “That’s kind of serial-killer talk. I don’t remember any new president ever having to say that out loud.” He paused. “After all, it was FDR who said, ‘We have nothing to fear, don’t be afraid, it puts the lotion on its skin.’”

“I’m paraphrasing! I’m paraphrasing, obviously,” Colbert said. “I’m not a historian.”

He’s not. But he is a pundit, in his way. He has a platform that gives him political influence. And late-night comedy, like so much else, will likely be forever changed by a Trump presidency. As Colbert told his viewers the day after the election, choosing civics over comedy: “Don’t stop speaking up. Don’t stop speaking your mind. Don’t ever be cowed by what happens in the next four years.”

Elena Ferrante’s Right to a Pseudonym

The writing life has always been a risky business. Writers have dodged kings and popes, tyrants and megalomaniacs. But for female writers, the cruelest judge of all has often been society. Society has been quick to criticize ambitious women, a tendency Charlotte Brontë challenged in her work, including in her masterpiece Jane Eyre. It also ostracized those who dared to enter relationships outside marriage, as George Eliot found when she lived as the unmarried partner of George Lewes. Among the various tools in their arsenal of self-protection, writers have historically relied on the ability to write under a different name. Like Eliot, the Brontë sisters famously wrote as men, because, as Charlotte ultimately explained, “we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.”

But this trusted tool of writers—the pseudonym—may now have become unreliable. In the era of Google and Facebook, it’s extraordinarily difficult for public figures to hide from scrutiny or, in the case of authors like the Italian novelist who publishes as Elena Ferrante, to keep their true identities a secret. Ferrante built her career around an imagined and assumed name, and her publisher assisted her in maintaining the veil of pseudonymity. But, as is now well known, she was “outed” in October by an Italian journalist, Claudio Gatti, who published his findings in four venues, in four different languages, around the world. Perhaps to his own surprise, his revelations generated a great deal of acrimony. He has been accused of everything from violating privacy to instigating a form of virtual sexual assault.

Nevertheless, for all the condemnation that Gatti has faced, he hasn’t been accused of the one crime of which he is probably guilty: violating the moral right of the author.

Moral rights are a part of copyright law. The entire discussion surrounding Ferrante, which has so captivated the media, fails to address copyright—something that is, from an author’s point of view, very important. Copyright came into being, long before Disney and Spotify, for the fundamental purpose of guaranteeing and protecting an author’s rights. In most countries—including Italy, home to both Ferrante and Gatti—copyright law protects an author’s right to be acknowledged as the creator of his or her own work. This right is known as a “moral” right, to contrast this special, non-economic prerogative of authors with the economic benefits of owning a work, which is usually acquired by a publisher, producer, entertainment company, or other corporate entity. The right to write under a pseudonym—to choose the name by which you actually want to be recognized—is widely accepted as intrinsic to the idea of “attribution.” If Ferrante were interested in taking Gatti to court for violating her moral right to write under a pseudonym, suing under Italy’s copyright law, she would probably have a good chance of success.

Curiously, the United States remains possibly the only country in the world not to recognize an author’s right to be named as the creator of his or her own work, despite huge pressure from authors’ groups and legal experts to do so. American law provides for a limited “right of attribution,” as it is called in the U.S. Copyright Act, but only in relation to works of fine art. Writers, musicians, and creators working in other disciplines have no such right at all. Establishing one would bring the United States into line with the rest of the world—a good thing when creative works literally circulate without borders, and reputations must stand or fall on the global stage.

In Italy, the copyright law says that a pseudonym will be treated as equivalent to the author’s true name, unless (and until) the author chooses to reveal his or her identity. Both the language of the law, and its silences, are arguably significant. In no way is any outsider empowered to reveal an author’s “true” identity when the author has chosen to publish under a pseudonym. Italian law wouldn’t seem to condone a concerted effort such as Gatti’s to uncover Ferrante’s identity.

Copyright was one of the first steps that modern democracies took towards guarantees for the liberty of speech.

Why are authors almost universally granted this strange, and strong, prerogative? The answer to this question lies at the heart of copyright history, in a perhaps surprising fact: Modern copyright law originated in the battle for freedom of speech. The first modern copyright law, the Statute of Anne, was passed in the United Kingdom in 1710, and was a crucial precursor to American copyright law. The Statute of Anne mediated the transition from a society where the sovereign could restrict speech by controlling the publication of books and other writings to one where works could be published without the approval or involvement of the state. Early copyright law accomplished this goal by a swift, simple, and surgical step: It took the right to control the publication of written works away from the sovereign, and placed it, instead, in the hands of authors. Authors could decide who would publish their works, and when, and how. Their new right would be held for a limited period, following which, anyone would have the right to re-publish any work of interest. In this way, the public domain was born.

Through these developments, authors effectively became the caretakers and champions of free speech. Early advocates of authors’ rights included eminent writers and thinkers such as John Milton and John Locke. The eventual creation of an author’s copyright was viewed as a victory for freedom of the press. In this sense, copyright was one of the first steps that modern democracies took on the path towards broader guarantees for the liberty of speech of the public.

Those early discussions recognized the value of the works that authors produce, but something even deeper was at stake: authorship. The elemental creative act of the author, and the social role and responsibilities that came with writing, emerged as key factors in the growth of democracy.

Not only do authors create works that are valuable to the public, but they also do so by a peculiar process: an act of free thought and, above all, imagination. Given the intrinsically free-ranging nature of the human imagination, writers often find themselves on the wrong side of power. Authors from Dostoevsky to Ken Saro-Wiwa, Voltaire to Subramania Bharati have criticized their rulers, fought against colonial administrations, railed against the unfairness of social traditions, and satirized local bullies.

In a well-known episode in Russian literary history, two writers of the 1960s, Andrei Siniavsky and Yuli Daniel, were put on trial by the Soviet government for the crime of writing. The trial was a unique occasion where imagined statements drawn from fictional works were used as evidence against the writers. In response to questions from the prosecutor, Siniavski stated firmly, “I am not a political writer … An artistic work does not express political views.” However, the nature of the prosecution confirmed the profoundly disturbing reality underlying the trial: even more than what the writers wrote, it was the fact of writing that was at issue. The very act of exercising a free imagination, beyond the boundaries of official state ideology, was an offense.

A pseudonym is more than a veil; it is also an expression of authorial identity.

Like Ferrante, Siniavsky, too, chose to write under a pseudonym. However, his pseudonym ultimately offered him little protection in a society where the privacy of the individual was not respected. In the modern, democratic context, as the reaction to Gatti’s investigation shows, the public is far less ready to accept violations, not only of privacy, but also, of authors’ creative prerogatives.

For, as many of Ferrante’s readers were quick to realize, a pseudonym is more than a veil; it is also an expression, in its own right, of authorial identity.

Ferrante herself eloquently and comprehensively addresses the issue of her choice to write under a pseudonym in a series of discussions, published in Italian more than a decade ago but appearing in English just now. The book, Frantumaglia, assembles interesting material drawn from interviews and other sources and seems to make clear that the decision to write under a pseudonym is one of the keys to Ferrante’s creative success. In a telling quote offered by Mini Kapoor, writing in The Hindu, Ferrante once responded to the interview question, “Who is Elena Ferrante?,” with the words, “Elena Ferrante? Thirteen letters, no more or less. Her definition is all there.”

Under the protection of this name, Ferrante has written about the lives of people emerging from poverty-stricken backgrounds in Naples. In this light, the revelation of Ferrante’s “true” identity has stirred up particular excitement because it appears that she comes from a different background from that of the people she has written so convincingly about. If Gatti is right, the “real” Ferrante is a talented translator, “the daughter of a German Jewish refugee,” whose husband is also a novelist. Her example is said to stand for the principle that a writer has a right to imagine lives different from his or her own.

Good writing, even when it disturbs us, is a potent reminder of what it means to be a human being.

But this interpretation misses the point. The only real limits to what a writer writes should be determined by his or her own imaginative capacity; and it is the reader who will ultimately judge how successful that act of imagination has been. A writer’s imagination can be powerful, hurtful, and sometimes, so dangerous to society that the works are ultimately proscribed. But this is treacherous ground; except in extreme circumstances, the suppression of imaginative literature represents a fundamental threat to freedom of thought. When writers work, they imagine; and, by affirming freedom of the imagination, a writer asserts, on behalf of every reader, the right to imagine a life beyond the confines of everyday experience. It is an escape, it is an experience, and it can be transcendent. Good writing, even when it disturbs us, is a potent reminder of what it means to be a human being.

When a writer adopts a pseudonym, he or she has embarked upon the ultimate act of imagination. The writer turns the imaginative eye inward—imagining a new, creative self. Not only writers, but also, artists in other fields, and from every culture, have played with the conventions of identity to carry out their work. The street artist Banksy is unidentified; while it is claimed that this is partly because making street art can be illegal, it is also evident that the mystery of Banksy’s identity brings special excitement to his work. Going a step further, this is perhaps what the great classical pianist, Glenn Gould, meant, when he claimed that his own biography might best be approached as a work of fiction.

Depending on how involved this creative act is, how passionately the artist is committed to his or her self-created identity, and how important that identity is to the psyche of the writer, intrusion upon it could be a serious personal and creative blow. Without the transformative magic of the writer’s mask, creativity just may not be possible. No wonder the “real” Ms. Ferrante, and her admirers, ask themselves if she will ever write again.

November 14, 2016

What Westworld's Twist Says About the Show

This post contains spoilers for the most recent episode of Westworld.

For its first seven episodes, Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright) was the closest thing to an audience surrogate on Westworld—a troubled conscience stalking around in the lower decks of the vast virtual theme park he helps maintain. The head of Westworld’s programming department and the designer of the artificial consciousness that powers its android “hosts,” Bernard was the character who seemed most interested in exploring the blurry line between reality and fantasy within the show. So it’s hardly surprising that he turned out to be a robot himself—one entirely under the sway of the park’s increasingly terrifying creator Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) who’s been programmed to murder on command.

Many hardcore fans had guessed that Bernard could be a fake—a “host” unaware of his own artificiality—simply because the premise of the show demanded it. In a world where people and androids are functionally indistinguishable, what better twist than seeing how deep that rabbit hole can go? Beyond that, though, the idea that Bernard is as programmed as the Western characters he creates added a further layer to the show’s meta-text. If this is a show about the sameness of entertainment—the grim violence, and the sexual exploitation that so often seems to come hand-in-hand with it—then surely its creators should be part of the formula as well. To Westworld’s inhabitants, Bernard is like a god—but to the park’s real god, Robert Ford, Bernard is just another plaything following a script. Going forward, much of the show’s narrative tension will lie in whether Bernard can break free.

There were plenty of clues through the first seven episodes to help viewer guess at Bernard’s true nature. His tragic backstory felt almost perfunctory: He was haunted by the death of a child, whom viewers saw Bernard visiting at the hospital in suitably moving flashbacks. His interest in Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood), one of the park’s oldest “hosts” and one showing the earliest signs of self-awareness, was almost pathological, a secret he kept from the other programmers. Most importantly, Bernard seemed trapped in the bowels of Westworld, constantly stalking its glass-lined office hallways, giving no hint of a life outside the park.

Bernard, it turns out, is a thrall of Ford’s, one whose reality can be as easily augmented as the characters he works on. When Westworld’s operations leader Theresa (Sidse Babett Knudsen) shows him damning evidence of Ford’s hidden machinations, Bernard sees nothing at all—because he’s been programmed not to. His entire world is as curated as the one in the park, just in a more mundane, and thus more outwardly human way. Watching that dawn on Theresa (who later died at Bernard’s hands) was a brilliant, fourth-wall shattering moment, where Theresa suddenly saw the seams of Bernard’s experience and the external limits of his reality.

Ford has continued to argue that he’s simply fighting for creative freedom, to stop Westworld’s corporate owners from taking his technology and using it for more nefarious purposes (imagine the military applications of lifelike, flesh-and-blood constructs who can be made to look like anyone). Writing for The New York Times, Scott Tobias took the metaphor a step further and cast Ford as a maniacal Hollywood director, able to conjure his characters into reality and use them to violently battle studio interference. But it’s hard to believe that Ford is just interested in telling hackneyed Western tales. The sight of Bernard beating Theresa to death suggested something deeper, and darker, to be revealed in the last three episodes (though the show is coming back—HBO announced Monday that Westworld had been renewed for a second season).

Bernard’s soul, his morality, will be the real battleground for the next few weeks of Westworld.

This is the kind of twist a show can only pull off so often, since it disrupts the foundation of the show so extensively. While the humanity of the “hosts” is no longer up for debate, preserving their dynamic with “real” humans is crucial to Westworld. (Essentially, if everyone can be revealed to be a robot, then that fascinating tension between “hosts” and “guests” is lost.) Fortunately, the show plainly telegraphed the notion that something was different about Bernard—it helped earn the reveal, while suggesting it won’t happen again, since there’s no other obvious “artificial” candidate in the offices. It was also an extended version of the pilot episode’s “twist” about Teddy (James Marsden), who initially seemed like a human guest in the park but turned out to be a host. As Westworld nears its finale, there are plenty more prominent “fan theories” ready to be confirmed or knocked down, particularly concerning its overarching timeline, which has been kept vague.

But the show is the most thrilling when it’s concentrating on the fundamental humanity of its characters. Bernard’s reveal was shocking and memorable not only because of what it revealed about the show, but also because it left him with blood on his hands. Just like with the park’s other “hosts,” viewers know there are limits to Bernard’s programming, but also the potential for his mind to start expanding beyond them. His future as a “host,” and his chance for self-awareness, is much more compelling than his previous role as a befuddled naysayer within the programming department. Bernard’s soul, his morality, will be the real battleground for the next few weeks of Westworld, and it should make for a far more enthralling watch than a boardroom tussle or an Old West shootout.

Joe Biden, a Meme for All Seasons

A meme, pared of its particulars, is democracy making fun of itself. And during the eight years of the Obama presidency in the United States, there has been no public figure who has lent himself so readily to memery than Vice President Joe Biden. You can attribute that to a combination of factors—his genial, expressive face; his persona’s mixture of frankness and affability; the fact that he occupies an office that lends itself especially well to fan-fictional speculation; his general intolerance for malarkey—but they have resulted, all in all, in Biden becoming, in the worst way and also the best, a running joke.

One of the most common memes goes like this: Take a picture of Obama and Biden together—bonus points if Biden looks giddy, and even more if points if Obama looks reluctant. Add dialogue—usually something that will get at the idea of Biden being childlike and needy and mischievous, and of Obama, decades younger and yet much more the adult, keeping his vice president in check. Apply it to the State of the Union. Or, really, to anything.

The aftermath of the 2016 election has given that time-honored formula renewed life, as people who are disappointed with the outcome of the hard-fought contest have channeled their frustrations through Biden—and through, specifically, the elaborate revenge fantasies they have imagined on his behalf:

Joe: I'm going to ask Donald if he wants something to eat

Barack: That's nice, Joe

Joe: And then I'm going to offer him knuckle sandwiches pic.twitter.com/xYJ0k2QTX6

— Jill Biden (@JillBidenVeep) November 13, 2016

Biden: Ok here's the plan: have you seen Home Alone

Obama: Joe, no

Biden: Just one booby trap

Obama: Joe pic.twitter.com/BgZ4lCoqg4

— Male Thoughts (@SteveStfler) November 13, 2016

Biden: You know he needs an official gov't phone right? Imma give him a Note 7.

Obama: But Joe, don't those....

Biden: Exactly. pic.twitter.com/HFXzpSN9Kj

— Tatiana King Jones (@TatianaKing) November 13, 2016

Biden: Hillary was saying they took the W's off the keyboards when Bush won!

Obama: Joe put-

Biden: I TOOK THE T'S, THEY CAN ONLY TYPE RUMP pic.twitter.com/D6Vh7Zu429

— Josh (@jbillinson) November 13, 2016

biden: cmon you gotta print a fake birth certificate, put it in an envelope labeled "SECRET" and leave it in the oval office desk

obama: joe pic.twitter.com/UTtv1JkE5o

— jomny sun (@jonnysun) November 11, 2016

Obama: Did you replace all the toiletries with travel size bottles?

Biden: He's got tiny hands Barack, I want him to feel welcome here pic.twitter.com/e7NRIZ43Ww

— Josh (@jbillinson) November 11, 2016

Biden: I took a Staples red button & wrote "Nukes" on it

Obama: Joe!

Biden: Tweets to him in Russian when pressed pic.twitter.com/j7rdFd1tXs

— Crutnacker (@Crutnacker) November 13, 2016

Joe: Yes, that was me.

Obama: Please stop.

Joe: I will not stop. This room will smell so bad when he gets here.

Obama: Joe...

Joe: Nope. pic.twitter.com/49WkhsUwvr

— Aaron Paul (@aaronpaul_8) November 12, 2016

Biden: What if we paint the Mexican flag in the office

Obama: Joe, no

Biden: I already ordered the paint

Obama: Joe pic.twitter.com/mCCh6OPQRk

— dan // pinned if unf (@tragecies) November 11, 2016

It’s democratized fan-fiction, basically: The Onion’s absurdist imaginings of “Diamond Joe,” only with this version of the vice president being, basically, an overgrown kid. And, as the best memes will do, all the jokes suggest something at once silly and profound: Over the weekend, they became an excuse for people both to wallow in their sadness and to transcend it. CNN offered “The 11 most soothing Joe Biden memes for a post-election America.” US Weekly announced that “Barack Obama, Joe Biden Memes Rule the Internet Post-Election.” The Huffington Post explained that “Joe Biden Trolls Trump In Bittersweet Post-Election Meme.” Mashable put it more bluntly: “Joe Biden plotting against Trump is the meme America needs.”

“America”—or at least, some significant portion of America—needed Joe because, in the persona they projected onto him, he channeled not just their thoughts about their new president, but also their feelings. Elections, after all, are not simply contests of policy, or dueling visions for the continuation of the American experiment. They are not merely intellectual. They are also personal. They are painful. They tap into, as we have seen, people’s baser instincts, their lizard brains. Campaigns assume, on some basic level, that adult people are immensely capable of behaving like children.

And there, in all that, is Joe Biden—a man in his 70s who has come to stand in for immaturity. A man whose team has lost, but who will, like many of his fellow Americans, take some solace in the fact that “I TOOK THE T'S, THEY CAN ONLY TYPE RUMP.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower