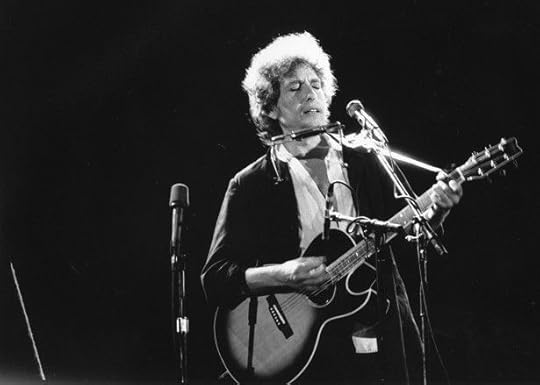

It Pays to Be a Jerk, Bob Dylan Edition

Last month, the Nobel Committee announced that it had awarded Bob Dylan its prize for literature. Amid the speculation that ensued—are song lyrics literature? what is literature? what is the Nobel Prize for?—another thing, a much pettier thing, took place: Bob Dylan proceeded to totally ignore the Nobel Committee. Voicemails went unanswered. Emails went un-replied to. “Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature” was briefly added to Dylan’s website, then quickly removed. A member of the Nobel committee, frustrated, called Dylan “impolite and arrogant.” The whole thing was awkward and weird and a timely reminder that even the echelons of art and culture are occupied by humans and their lizard brains. Here was Emily Post’s worst nightmare, played out on a global scale—albeit with many, many “his answer is blowin’ in the wind” jokes thrown in for good measure.

Wednesday, it turned out, brought a new twist to what The New York Times has taken to calling “the saga of Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize”: Dylan, it seems, finally communicated with the Nobel committee—to inform them that he will not,in fact be attending the prize ceremony with his fellow laureates. Which is, in the end, not at all surprising. After all, this kind of thing is what Dylan does, as an artist and a person. He’s a “screw the establishment” kind of guy; ironically, that political positioning is what helped him to win the Nobel in the first place. And it’s how members of the media have justified his behavior on his behalf. “‘That’s just Dylan being Dylan,’” James Wolcott, a columnist for Vanity Fair, tweeted about the whole episode. “You could substitute any egotist’s name in that formulation.” The Telegraph noted of the erstwhile radio silence that Dylan “always does the unexpected.” The Guardian praised his “noble refusal of the Nobel prize for literature.” The New York Times compared Dylan, in his reticence, to Jean-Paul Sartre, who himself famously declined his own Nobel in 1964. And then the paper declared that Dylan’s behavior “has been a wonderful demonstration of what real artistic and philosophical freedom looks like.”

Here was Emily Post’s worst nightmare, played out on a global scale—albeit with many “his answer is blowin’ in the wind” jokes thrown in.

Noble! Philosophical! Wonderful! The other way to see things, however, is that Bob Dylan has simply been acting, if you’ll allow me to put it very poetically, like an enormous and overgrown man-baby, refusing to acknowledge his being awarded one of the most prestigious prizes in the world in a way that manages to be both delightfully and astoundingly rude. Perhaps, sure, Dylan has done all this on principle. Perhaps he has been, with his preemptive ghosting, trying to make a point. The trouble is that until today, all anyone could do was speculate about his intentions, because Dylan had simply refused to engage in that most basic transaction of civil society: to send an RSVP. He may have been embracing the role of renegade/rebel/independent artist; he was also, however, embracing the role of a jerk.

It’s striking, all in all, how readily he has been rewarded for that. Dylan is noble! He’s principled! He’s just like Sartre! Hell, as Dylan’s fellow semi-laureate suspected, may well be other people; it’s notable, though, how much more hellish other people can be when they fancy themselves too fancy for basic courtesy. And it’s even more hellish when the people at the culture’s echelons—the ones we look up to, the ones we celebrate, the ones whose songs we sing—are the same people who can’t be bothered to pick up a phone when it rings, or to give a simple “sure!” or “no, thanks” when offered an honor on behalf of the world.

There are many people in that group—the vaunted jerks, the ascendant assholes, the men (it is, alarmingly often, men) who flout basic conventions of courtesy and respect, and who are then rewarded for it. There’s Steve Jobs, about whom it was written, after his death, “Steve Jobs Was an Asshole, Here Are His Best Insults” and “Steve Jobs didn’t care if people thought he was an asshole. Why should we?” and “Steve Jobs Was A Jerk. Good For Him.” There’s Elon Musk. There’s Mel Gibson. There’s the country’s new president.

Related Story

There’s a sliding scale in all this, certainly. Some of them are actively bad: Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin and Thomas Edison were wonderful to humanity, but occasionally terrible to its individual members. Today, for the most part, we turn a blind eye to their interpersonal failings, preferring instead to judge them in the gleam of history. But what’s in some ways even more worrying is the accumulation—the celebration—of small slights, shortcomings that are not obviously immoral so much as they are … sloppily inconsiderate. The Dylan-like situations that find celebrities being celebrated specifically for their jerkiness—as if their assholery doubles as a kind of bravery. As if they fail to follow the mandates of civic decency not because they are ignoring those rules, but because they are transcending them.

It’s the logic that helped to cement Lyndon Johnson as a political legend. (Did you hear about the toilet thing? Or, lol, when he ordered those pants?) It’s the logic that has helped to ensure that Steve Jobs will remain a kind of secular prophet. It’s the logic that sees Donald Trump as, above all, a truth-teller, loved by his legions of fans for “telling it like it is.” The Atlantic, last year, ran a long, research-based feature on those people. It was called “Why It Pays to Be a Jerk.” There are, it will probably not surprise you, many—so many—of those reasons.

And so here is Bob Dylan, being not actively Bad but rather, more simply and more confusingly, rude. And here he is, being celebrated for it. “There is a good deal of poetic justice in this turn of events,” the Times enthused. And “for all the speculation over the last two weeks about the reasons behind his blanket silence on the Nobel award,” The Telegraph put it, “I can only say that he is a radical personality—which is why he has remained of so much interest to us over six decades since he first emerged on the Manhattan music scene in 1962—and cannot be tied down, even by the Nobel Prize committee.”

There was one group, however, who was less breathless about Dylan’s recent antics. The Nobel committee, in announcing that Dylan would not come to the party they will be throwing in his honor, offered an abundance of kind words about the artist and the prize he is being awarded. “He underscored, once again, that he feels very honored indeed, wishing that he could receive the prize in person,” the committee noted. The committee’s frustration, however, shone through, even in an otherwise standard press release: “We look forward to Bob Dylan’s Nobel Lecture, which he must give—it is the only requirement—within six months counting from December 10, 2016.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower