Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 43

November 18, 2016

Zadie Smith on the Politics of Fiction

Zadie Smith is best known as a novelist, but she’s also, in the fullest sense of the term, a public intellectual. Some of her most striking work in recent years has reached outside the realm of fiction, including essays about 9/11 and fear of words, and the soaring language of Barack Obama, and the political soulcraft of Facebook. It’s work that, on top of so much else, serves as a reminder of how profoundly politics is insinuated into literature, and into culture, at all their heights and depths. It’s work, too, that highlights how futile it can be to think about politics as its own category of discourse and experience. Politics is the water we swim in, and the air we breathe. It is around us, whether we choose to acknowledge it or not.

At a discussion in Washington, D.C., on Thursday evening—part of the book tour for Smith’s latest novel, Swing Time—the interviewer and NPR host Michele Norris asked Smith about all that: the connection between the politics and ... everything else. We are living, Norris noted, in “interesting times.” And “I wonder,” she said, “if that changes your approach to your work in terms of feeling some sense of responsibility, but also opportunity, to help people.” Can fiction—and words, in their simultaneous starkness and warmth—“help people see things that maybe they wouldn’t see otherwise?”

Related Story

Zadie Smith’s Dance of Ambivalence

“I guess I look at it historically,” Smith replied. “I think of what happened to writers, or at least British writers, after the second world war.” Those writers became, essentially, politicized: Their times were simply too interesting for them to be anything else. “Writers who are, by temperament, not political writers find themselves in these situations,” Smith said, and they then have little choice but to become, in their way, political actors. Take E.M. Forster, one of Smith’s role models as a writer (On Beauty, she has said, was an “homage” to Howard’s End). “In peaceful times,” Smith noted, he “was not a man to stand up, not a man to make an argument.” But Forster did not live, finally, in peaceful times. So “he ended up on the radio having to speak in a way that he was not quite used to speaking. And I think he did a very effective job. But it was interesting to watch. In another life, he would have been much quieter.”

Today, too, Smith said, writers are playing that same role: They’re offering not just escapism from the world’s realities, but immersion within them. And some of them are doing that not necessarily by being activists or commentators, but by also by doing something both simpler and more complicated. They’re acting, sometimes, as journalists. They, too, are recognizing how thin the line can be: the politics, and the everything else.

It’s a recognition that is especially powerful at this moment—this week, this month, this coming year—as professional journalists, too, are considering their own relationship to the many, many people who see them as “out of touch,” and “biased,” and “elite.” To the many people who mock them, essentially, on grounds that they’ve failed both at objectivity and at empathy. Smith suggested that, as with most things, reporting—which merges objective fact with an honest effort at empathy—can be an answer. She pointed to George Saunders and, in particular, the literary analysis of Trump supporters he published in the New Yorker. To write that story, Saunders went out and spoke to people, Smith noted—he tried to empathize and understand—and because of that effort, in retrospect, he “saw what was obvious.”

Reading that story, Smith said, “reminded me, personally, of my own father, who was a middle-class white man, but not an angry or racist one.” Especially because “many of the things that happened to these people also happened to him”: unemployment, divorce, illness. Things that shatter lives and, too often, break the people who live them. “But those things happened within the context of free health care, free education, and welfare,” Smith noted—so when her father fell ill, for example, it didn’t bankrupt him. There was not one misfortune standing between things are okay and utter despair.

The politics and the everything else, bound inextricably to each other. And the I and the you and the we, similarly fused. “For me,” Smith said, “reading those pieces”—Saunders’s, and similar works—“reminded me to make the connection between those people and someone I knew very well: my own father.” Those stories used reality, rather than fiction, to encourage her to bend her own imagination toward empathy. “That kind of journalism, I think, is very useful,” Smith said. And engaging in it means that writers like Saunders “are ready for the times—and they are essential.”

“I don’t think,” Smith added, contra the many magisterial novels and essays and speeches that would seem to suggest otherwise, “I’m one of those writers.” But “even comic novelists have to find some way to get their act together,” she said. “So I’m surprised, sometimes, by what I write now, by the pieces I write. Because I wouldn’t have thought that I would write on political subjects. But I have, quite a lot. It must just be experimenting with the times, really.”

Finding Meaning in the Mannequin Challenge

Rae Sremmurd’s “Black Beatles” is the No. 1 song in the country, thanks to a trend in which people fantasize about being frozen in time as if the software that runs all of existence has crashed, or as if a new Vesuvius has encased everyone forever in ash. Perhaps you understand the appeal already.

#TheMannequinChallenge began in late October when students at a Jacksonville high school filmed themselves pretending to be stuck motionless, mid-pose, as if they were modeling slacks at Macy’s. The clip gained traction online and other people started to make their own versions, many set to the bubbling-up rap track “Black Beatles” for no real reason at all. (“It’s my favorite song,” the 17-year-old who first paired the tune and the trend told The New York Times.) Even the greatest haters of internet culture, even those who somehow see signs of civilizational decline in planking and the running man, have to admit the meme is a pretty joyful thing, capturing football teams, gymnastic squads, and dogs turning life into fresco.

Colony high school

Donald Trump's CIA Pick Made His Name on the Benghazi Committee

Mike Pompeo, who is reportedly Donald Trump’s choice to head the CIA, is a three-term Republican representative from Kansas who serves on the House energy committee and was a member of the panel that investigated the deadly attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, in 2012.

Pompeo, a conservative backed by the Koch Industries political-action committee, was elected to Congress in 2010 during the Tea Party wave. But he is perhaps best known for two things: His opposition to the recent nuclear deal Iran struck with the U.S. and other Western countries, and his work on the House Select Committee on Benghazi.

Pompeo and Jim Jordan, his ally on the Benghazi committee, felt its final report, approved by Trey Gowdy, the panel’s Republican chairman from South Carolina, did not sufficiently fault the Obama administration and Hillary Clinton, who was secretary of state at the time, for the deadly attacks in 2012 that killed Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans. Pompeo and Jordan released a supplement to the panel’s report that concluded Clinton “misled the public” about the events in Benghazi because of President Obama’s campaign for re-election. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump made Clinton’s actions during Benghazi a centerpiece of his attacks against her.

Pompeo’s thinking is likely allied with Trump on another foreign-policy issue: the nuclear deal with Iran that was signed last year. The Obama administration, its allies, and Russia negotiated the agreement that freezes the Islamic republic’s nuclear program for 15 years. Trump has called the agreement “the stupidest deal of all time.” Pompeo and Senator Tom Cotton, the Republican from Arkansas, had alleged the Obama administration offered Tehran “secret side deals” in exchange for the deal. They said officials at the International Atomic Energy Agency, which is the UN’s nuclear watchdog, told them there were private arrangements with Iran on the inspections of military facilities. The Obama administration countered that this was standard practice in such negotiations.

Pompeo is a strong supporter of the National Security Agency’s mass-surveillance programs, which he has described as “important work.” He also said Edward Snowden, the NSA contractor who revealed the agency’s programs, is a traitor who “should be brought back from Russia and given due process, and I think the proper outcome would be that he would be given a death sentence.” Pompeo has called Guantanamo Bay, where the U.S. holds suspects from the war on terrorism, “critical to national security,” and after a visit there said the detainees there looked like they “had put on weight.”

After the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, Pompeo said American Muslim leaders had a “special obligation” to speak out. He said: “Instead of responding, silence has made these Islamic leaders across America potentially complicit in these acts and more importantly still, in those that may well follow.”

Pompeo graduated at the top of his class from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and served from 1986 to 1991, during the Cold War, as a cavalry officer. He then attended Harvard Law School and edited the Harvard Law Review before moving to Kansas where he and three partners founded Thayer Aerospace, a company that makes parts for commercial and military aircraft. He sold Thayer and became president of Sentry International, an oilfield-equipment-manufacturing company, before running successfully for a House seat in 2010.

What Gwen Ifill Knew About Race in America

Gwen Ifill and I used to exchange hate mail on a semi-regular basis. Not our own, of course. I loved Gwen the way so many people, both in Washington and across the country, loved Gwen, and like so many people, I found myself broken by her death earlier this week. I don’t have the temerity to characterize her view of me, except to say that she cared enough about my happiness, and my reputation, such as it is, to offer up behavioral guidance whenever she felt it necessary. This guidance often consisted of two words: “Stop tweeting!”

The hate mail we shared was directed at us by racists and anti-Semites. Gwen, of course, was a singular figure of extraordinary prominence. Try to name the African American women at the summit of the television news business, and you’ll likely struggle to produce a long list, or, for that matter, a list. Gwen’s fame, her charisma, her obdurate adherence to fact-based standards many people now consider antediluvian, and her top-tier intellect combined to make her a figure of adoration for many, but also a target of loathing for others.

I spent some time this week rummaging through our old email and text exchanges, an exercise that reminded me of her humility, her gift for friendship, her good humor, and also her perspicacity. Because Gwen, it seemed, knew what was coming. I was brought up short by one exchange in particular that grew out of the reaction to an article I wrote in early 2012. The article concerned the practice of dog-whistling, the use of coded, ambiguous language by politicians to appeal to the prejudices of certain voters. Dog-whistling now seems so very 2012; one of Donald Trump’s many campaign innovations was to discard dog-whistling in favor of more straightforward appeals to prejudice. But at the time, Newt Gingrich’s criticism of President Obama as the “food-stamp president,” to cite one example, seemed worthy of comment.

Gwen warned me, soon after this piece was published, “Brace yourself for the crazies.” And the crazies came. Some of the critics believed that my Jewishness disqualified me from commenting on American affairs: “You Jews should remember that this isn’t your country,” one such emailer wrote. “Stop using black criminals to ruin the great United States!” Another correspondent wrote: “You are part of the race problem, not any solution!!! Just keep writing!! Eventually your own specious diatribe will out you for the vitriolic whore that you are!!!”

Gwen found the profligate use of exclamation points amusing, but she also sensed, in this sort of discourse, ominous signs about the direction of our politics. She wrote, “Someday, we will have a drink and I will take your anti-Semites and match them against my racists. If I weren’t a better person … I swear, I would worry about our lovely nation.”

We ended up having lunch a few weeks later, in which we joked about the menagerie of miscreants we seemed to attract. Being with Gwen was always joyful—her smile was a thing of wonder—even when the subject at hand was hatred. As David Brooks wrote earlier this week, “When the Ifill incandescence came at you, you were getting human connection full-bore.”

Gwen’s moral imagination allowed her to worry about all forms of prejudice, and when I was targeted by Jew-haters, she would reach out to check on me. She would sometimes do so in ways that made me laugh: “I found a dreidel in my house the other day and thought of you,” she once wrote.

Gwen’s death is a cruel blow to her lovely nation, which is now in need of her bravery, her farsightedness, and her willingness to tell the truth.

Gwen also had earnest advice for me at lunch that day. “Just keep your head down and keep writing, because that’s what they don’t want you to do.” Like many African American journalists, she was not surprised by the intensity of the invective poisoning the American conversation, but she still seemed a bit shocked, in the way that optimists find themselves periodically shocked by reality. Though she was a hopeful person, Gwen was not the type to believe that the election of Barack Obama heralded America’s entrance into a benign post-racial future.

Earlier this week, I asked Gwen’s great friend, the journalist Michele Norris, if I was correct to argue that Gwen predicted the rise of Trumpism well before the rise of Trump. “I am not so sure I would say that she ‘saw this coming,’” Norris wrote by email, “because she understood that what we see in the open now has always percolated below the surface.” Gwen, Norris went on to write, “knew she had the power to drive not just the narrative around race but to highlight the nuances that most journalists simply missed, even though they were right in front of them … She was very humble and so she might dismiss the notion that she was prescient. She was pragmatic. I can hear her saying, ‘I just saw what should have been obvious.’”

An insufficient number of people have recognized what is obvious. Gwen’s death is a punishing blow to her family, and to her wide circle of friends, to her colleagues and to her viewers. But it is also a cruel blow to her profession, which hasn’t recently covered itself in glory. And it’s an especially cruel blow to her lovely nation, which is right now in need of her bravery, her farsightedness, and her willingness to tell the truth. Hers is an incalculable loss.

Donald Trump's Choice for National Security Adviser Has One Priority: Combatting 'Radical Islamic Terrorism'

Michael Flynn, the retired Army lieutenant general and former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) whom Donald Trump has picked to be his national security adviser, is known for his long and distinguished military career, his unceremonious exit from the DIA, and for his controversial views on Islam, torture, and Russia.

Flynn, a registered Democrat, was an early and ardent supporter of Trump’s improbable presidential run, giving the Republican presidential hopeful a much-needed endorsement from the national-security establishment. He led crowds at Trump’s rallies to chant “Lock her up” about Hillary Clinton, Trump’s Democratic opponent. “Donald Trump is about the future of this country and making sure that we take a direction … that puts us back on a track that we can continue to be the global leader around the world,” he told Fox Business Network in July.

But his tenure at the DIA, as well as his remarks about Islam and torture, made Flynn a divisive figure. He might have had trouble winning Senate confirmation had Trump nominated him for a Cabinet position that requires one; the position of national security adviser does not. Flynn said he believes the Obama administration’s failure to describe the conflict with groups like ISIS as “radical Islamic terrorism” aims to “dumb us down”; said on Twitter that “we are facing violent, but very serious and cunning radical Islamists”; and, also on Twitter, called the fear of Muslims “rational.” Additionally, he once retweeted an anti-Semitic message that read “Cnn implicated. 'The USSR is to blame!' ... Not anymore, Jews. Not anymore.” He apologized and later deleted the message. Flynn has also declined to back away from Trump’s support of the waterboarding of terrorism suspects, telling Al Jazeera that he is a “believer in leaving as many options on the table right up until the last possible minute.”

Before these controversies, however, Flynn was the consummate military man. He distinguished himself during the war in Afghanistan where he was General Stanley McChrystal’s intelligence chief. In the early phases of the war on terrorism, Flynn, as director of intelligence for Joint Task Force 180, was in charge of intelligence-gathering and collection for most of the forces leading the battle against the Taliban and al-Qaeda. As Marc Ambinder noted in The Atlantic in May 2011, McChrystal and Flynn “introduced hardened commandos to basic criminal forensic techniques and then used highly advanced and still-classified technology to transform bits of information into actionable intelligence. … Such analysis helped the CIA to establish, with a high degree of probability, that Osama bin Laden and his family were hiding” in a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. It’s in that position Flynn also angered the U.S. defense and intelligence establishment, writing a report in which he called many intelligence analysts “ignorant,” “incurious,” and “disengaged”—assessments he stood by even when he was criticized for them.

President Obama named him head of the DIA in 2012, but he was forced out two years later, effectively over his management style. He viewed his firing as unfair and as payback for unpleasant truths he spoke about Islamist terrorism in general and the threats posed by ISIS in particular. While at the DIA, Flynn advocated an immediate overhaul of the agency—an initiative that received pushback from the intelligence community. Reuters spoke to unnamed critics of Flynn who expressed concerns “about a management style that alienated some of his subordinates at DIA.” Still, his supporters say his experience in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as his candor, make him the right man for the position of national security adviser to Trump.

“I am, like, Mr. Change,” Flynn said in November 2010. “People that work for me know that we’re going to be innovative and, to a degree, we’re going to be uncomfortable in terms of how far we’re going to go to innovate. Because in war, if you stick with the norm, you’re going to lose.”

Flynn’s controversial views notwithstanding, he has said he is in favor of strengthening some old alliances—as well as building some new ones. He favors a hard line toward Iran, with which the U.S. and others Western nations recently signed an agreement that would freeze the Islamic republic’s nuclear program for 15 years; he supports closer ties with Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the Egyptian president who took power after a military-backed coup toppled an Islamist-led, democratically elected government; and he backs closer ties with Israel. Additionally, in a recent op-ed in The Hill, Flynn argued the U.S. should extradite Fethullah Gulen, the Pennsylvania-based Turkish cleric who that country’s government views as a terrorist leader. Flynn did not disclose at the time that he was a paid lobbyist for the Turkish government.

Flynn also favors close relations with Russia, and prompted criticism when he showed up during the election campaign on RT, the Russian state-funded broadcaster that often serves as a propaganda arm for the Russian government. In one such appearance, he was seated near Vladimir Putin, the Russian president. Flynn has defended his appearances on RT, comparing them to CNN or MSNBC in the U.S. Both Flynn and Trump have said the U.S. needs to work more closely with Russia to combat what they see as the biggest national-security threat the U.S. faces: Islamist terrorism.

Trump “looks at people and leaders of countries and says: ‘Can I work with this guy? Do we have a common threat that we can focus on?’” Flynn told The New York Times in an interview before the elections. “He knows that when it comes to Russia or any other country, the common enemy that we all have is radical Islam.”

Flynn is likely to take on his new position with the same energy and conviction with which he carried out his previous jobs. He suggested as much in remarks last weekend after Trump’s victory. “We just went through a revolution,” he said. “This is probably the biggest election in our nation's history, since bringing on George Washington when he decided not to be a king. That’s how important this is.”

Queer Writers in the Age of Trump

In 1948, when the American writer Patricia Highsmith started writing The Price of Salt, her seminal novel of lesbian love, she knew it would be difficult to find a publisher as an openly queer author. At the time, as she reflected in her 1989 afterword to the novel, it was already difficult enough just to be out as a lesbian in New York. “Those were the days,” she wrote, “when gay bars were a dark door somewhere in Manhattan, where people wanting to go to a certain bar got off the subway a station before or after the convenient one, lest they be suspected of being a homosexual.” It would be career suicide, she feared, to be known as a “lesbian book-writer.” So when the publisher of her first novel, Strangers on a Train, rejected The Price of Salt, she released the latter elsewhere under a pseudonym, Claire Morgan. It went on to become one of the most important works of queer American fiction.

The United States in 2016 is generally more accepting of queer writers than the country Highsmith described. But some of the rhetoric of President-Elect Donald Trump and a number of his supporters paints LGBT people in much the same way that they were seen in Highsmith’s day: as people who don’t deserve the same rights as other Americans. In January 2016, Trump told the Fox News host Chris Wallace that he would “strongly consider” appointing conservative justices who could repeal the ruling of Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court decision that made same-sex marriage legal last year. In June 2015, Vice President-Elect Mike Pence, who has a long history of opposition to LGBT rights, had responded more strongly to the decision, reaffirming his belief that marriage is between a man and a woman.

As a queer American and as a writer, the prospect of a Trump presidency troubles me. Yet Trump’s tenure, ironically, could be a spur to LGBT literature, propelling the development of an even more self-assured literature of American queerness than before.

I came to America from the Commonwealth of Dominica. For me, like many other queer writers in the U.S., particularly those who’ve come from less safe places, America represented a kind of hope. Here was a country I’d decided to stay, as a dual citizen, after coming out. My former home in the Caribbean wasn’t a safe place to be openly queer in, and unlike the U.S., it lacked laws protecting LGBT persons from discrimination or violence. When I immigrated, I felt like a sea-traveler who had escaped from a storm, waves high as Hokusai’s, and who was now in a calmer place, free to fill my eyes with stars.

Of course, the United States was far from perfect. The killing of trans women is in the news so often that I’ve come to expect it. Bigotry against LGBT people is written into innumerable “religious freedom acts” akin to the one Pence signed. But, for all that, America was still a sanctuary, a world that could accept—and even defend—someone like me. Queer people were never fully safe, but here we could be happy and hopeful.

The day Trump was elected, I began to think of Shirley Jackson’s famous New Yorker story, “The Lottery.” In Jackson’s tale, published in 1948—the same year Highsmith began The Price of Salt—a New England town holds an annual lottery, in which each member of the town must pick a piece of paper from a closed box. One unlucky person who gets the single paper with a black dot on it will be stoned to death by the townspeople. Jackson’s story is cool and compressed, revealing the mundane savagery in an ordinary American town that exists when people cling too closely and literally to violent traditions. I had voted, not taken part in a lottery, yet felt like I had pulled out a card with a smudged black dot: an indication that something terrifying, was coming.

The work of queer American writers has taken on a renewed importance and urgency now.

Because the president-elect’s stances on LGBT issues have varied and often differed from the demonstrated record of the vice president-elect, it is still unclear exactly what queer people are up against. In 2000, Trump told the American LGBT magazine The Advocate that “sexual orientation would be meaningless” in a Trump administration. In April, Trump said Caitlyn Jenner could use the women’s restroom in Trump Towers, pushing back against the hardline anti-transgender rhetoric of Texas Senator Ted Cruz and North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory. Yet Trump told Wallace in January that marriage equality “should be a states’ rights issue,” and he appeared to implicitly double-down on his opposition to LGBT rights by choosing the staunchly anti-LGBT Pence as his running mate.

The day after Trump’s win, the National Organization for Marriage, founded in 2007 to oppose same-sex marriage, issued a statement that they would plan to “work with President Trump to nominate conservative justices to the U. S. Supreme Court,” who will “inevitably reverse” Obergefell, as well as to undo Obama’s executive orders protecting transgender individuals. Though Trump recently stated on 60 Minutes that he is “fine” with marriage equality, it’s difficult to trust him, given the variation and vagueness of his answers and the influence of anti-LGBT figures around him, including his top advisor, Stephen Bannon of Breitbart News.

The immediate reaction to the election among my community of queer writers was tinged with feelings of hopelessness, but many writers, such as Yezmin Villarreal, cautioned against wallowing in despair. The work of queer American writers has taken on a renewed importance and urgency now—an urgency that existed in the days before LGBT writers had legal protections. Many of the best-known queer texts, after all, emerged in times and places where being anything other than straight was—or remains—unsafe. The British writer Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 novel, The Well of Loneliness, featured a lesbian couple that Hall gently championed, portraying their queerness as natural and deserving of legal recognition. Despite its tameness, the mere fact that the book did not reproach its lesbian protagonists led to it being condemned as “obscene” in a notorious U.K. trial the year it was published. The book was the subject of another obscenity trial in America, though that case was ultimately dismissed by New York courts. Both Hall’s novel and Virginia Woolf’s gender-shifting novel Orlando—published the same year—later became iconic queer works, yet both emerged in worlds where non-discrimination laws for queer persons did not exist.

From 1913 to 1914, E.M. Forster wrote—but never in his lifetime published—the novel Maurice, which revolves around two men in love. It was only published in 1971, 55 years after it was composed, and it’s now one of Forster’s most widely taught novels. “Publishable. But worth it?” Forster wrote in a comment on his manuscript, revealing that he knew, like Highsmith, that releasing it could ruin his career. Other major texts in queer literature, like James Baldwin’s pioneering affirmation of bisexuality, Giovanni’s Room (1956), Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood (1936), which depicts gender dysphoria, and Rita Mae Brown’s 1973 lesbian classic, Rubyfruit Jungle, appeared at at times when much of America was hostile to LGBT people.

The opposite of hatred is not love, but, rather, compassion or empathy, which is what the best literature tries to instill in us.

These books helped inspire others like them. Many authors were tried in court for obscenity for writing works with queer elements, including Allen Ginsberg’s iconic long poem, Howl, and William S. Burroughs’ hallucinatory novel, Naked Lunch. These trials reinforced the danger of being openly queer, but also gave the texts in question greater visibility. Early LGBT literature in America helped counter a long history of works that portrayed queer people in a negative light: as jokes, as predators, as undesirables, or as monsters, as in the case of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s famous Irish lesbian vampire novella, Carmilla (1872).

Today, it’s still subversive, if not outright dangerous, for many writers around the world to publish books that feature LGBT characters as normal human beings. And yet, these stories continue to be written. Chinelo Okparanta’s 2015 novel, Under the Udala Trees, ends with a note tying it to anti-LGBT discrimination in Nigeria. The Jamaican writer Nicole Dennis-Benn’s recent novel, Here Comes the Sun, features a powerfully rendered queer couple living in a homophobic society. Transgender literature, too, is gaining momentum. Novels like Imogen Binnie’s Nevada, short-story collections like Casey Plett’s A Safe Girl to Love, and poetry collections like Kokumo’s Reacquainted with Life are powerful ways to write ourselves into being at a time when many people claim they have never knowingly seen a trans person before. Zines, journals, and publishing houses dedicated to queer literature, like Topside Press, are multiplying. And while it can still be difficult for queer writers to achieve mainstream visibility, the fact that so many publishers are creating new spaces for us is a critical step toward changing this.

In America, queer writers are no longer the outsiders we once were, but the legal repercussions of a Trump administration may force us back to the sidelines. Certainly, in many ways, Trump’s presidency is a wild card, but it is also clear that the United States itself is increasingly supportive of LGBT rights. In May of this year, a PEW poll revealed that 55 percent of Americans supported same-sex marriage. While transgender rights remain more contentious, our increasing visibility in the media has also slowly begun to tilt public opinion toward acceptance of trans people.

Contemporary America is filled with shadows and ghosts; we have never been free of the bigotries of homophobia, sexism, and racism. But it is also, despite all this, a more tolerant America than the one Highsmith lived in. The title of her novel had come from the biblical story of Lot, whose wife turns into a pillar of salt because she looks back while running away from the fallen city of Sodom. We cannot turn back to the past, either.

There are still places where LGBT Americans fear to go. But at its best, and often in times of the deepest challenges and uncertainties, our literature has offered a vision to the world of the possibilities that may exist within each person, of our ability to resist and persist, of our ability to make and remake ourselves, even in the face of unspeakable pain. Many of us are accustomed to benign ignorance at best and violent hatred at worst—and the opposite of hatred is not love, but, rather, compassion or empathy, which is what the best literature tries to instill in us. In such an atmosphere of uncertainty, we must remember, that even if for many of us the sky seems dark, our art can still be one of the lights leading us through the night.

November 17, 2016

Selfishness Is Complicated in You’re the Worst

This post contains spoilers for the full third season of You’re the Worst .

From its pilot onward, You’re the Worst has defied popular expectations for “rom-com TV.” Its central couple is an awful woman and an awful man, Jimmy and Gretchen, whose collective awfulness at times makes it impossible to root for them. The FX show’s opening theme song consists of the lyrics “I’m gonna leave you anyway” repeated over and over. So the sad twist at the end of the show’s third-season finale on Wednesday was in many ways built into the premise.

In the last scene, the pair (played by Chris Geere and Aya Cash) find themselves in a secluded spot overlooking downtown Los Angeles. Then: Jimmy pulls out a ring and drops to one knee. He delivers an overwrought, passionate speech: “Extraordinary, confounding Gretchen. She who emits more energy than a dying galaxy ... Together we transcend the mundanity down there.” Gretchen cries. They embrace. He asks her to marry him; she says yes. It’s disgustingly, delightfully romantic. As Jimmy heads to their car to get a blanket for them to have celebratory sex on, Gretchen calls after him to note the significance of their engagement. “We’re no longer just us,” she says. “We’re a family now.” And as Jimmy back turns around, his face changes, darkens, the reality of Gretchen’s words sinking in. And he does the only thing that makes sense to him: As fireworks begin exploding above them in the inky night sky, he gets into his car, and he leaves her there.

It’s the kind of reversal You’re the Worst has pulled before: the commitment-phobic Jimmy and Gretchen take a big step forward, whether deciding to move in together or become exclusive, only for the episode to end on their respective looks of what have I done? horror. So it’s a testament to the show’s brilliance that, despite signaling the couple’s doomed-ness from the start, the finale still hit so hard. You’re the Worst’s wonderful third season undoubtedly saw the most psychological and emotional progress yet for its stable of chaotic characters. It built incrementally on the notion that the pathologically selfish Jimmy and Gretchen, along with Gretchen’s best friend Lindsay and Jimmy’s war-veteran friend Edgar, aren’t totally hopeless 30-somethings. In their respective journeys toward becoming better people, each gained a new, more complicated understanding of selfishness—coming to terms with, yes, its pitfalls, but also, its hidden virtues. And yet, as Jimmy’s jilting of Gretchen suggests, this newfound emotional maturity can still have devastating consequences.

After a raucous first season with only hints of darkness, season two surprised many viewers with a full arc exploring Gretchen’s depression. You’re the Worst began its third season with a theme that felt like a logical next step—the difficulty (and humor) of managing mental illness. Over the last 13 episodes, though, You’re the Worst broadened its scope from mental illness to the more general task of self-improvement: of confronting tragedy, taking responsibility, learning from mistakes. Of trying, slowly, frustratingly, to become less “the worst.”

Gretchen started the season by seeking out a therapist (played by Samira Wiley) and, after several disastrous sessions, she finally realized how her mother’s impossibly high expectations fueled her depression. Jimmy, a novelist working on his second book, came to terms with how his desire to please his withholding father influenced his writing—after learning his dad had died of cancer. Edgar (Desmin Borges) discovered that marijuana was the only thing that helped his severe combat-related PTSD, and landed a comedy-writing gig. After trying to force her marriage to work, Lindsay (Kether Donohue) accepted that starting a family with her lovable but nerdy husband Paul would be a mistake, leading her to have an abortion and ask for a divorce.

In trying to think more about others, the characters were paradoxically forced to focus on themselves.

One of the biggest hurdles the characters faced was moving beyond their self-centeredness. Given how terrible Jimmy, Gretchen, and Lindsay are, the comedic effect of all their striving was often like watching cats try to bark: simple in concept, endlessly amusing in execution. And yet, they tried. Gretchen moved out of her comfort zone to support Jimmy after his father’s death (though she had debated not telling him the news so they still could go on their “Famous Pets of Instagram” cruise). Jimmy planned a grand romantic gesture to lure Gretchen to his surprise proposal spot, where he opened up and thanked her for bravely going to therapy, “for us.” As for Lindsay, she tried to swallow her own misgivings about her marriage so as not to hurt her husband, and in another episode, she put her problems aside and helped Edgar have a breakthrough about his PTSD. If these all sound like acts of basic human kindness, that’s because they are—but in the context of the You’re the Worst, they’re virtually Nobel Peace Prize-worthy.

In trying to think more about others, the characters were often paradoxically forced to focus more on themselves. This season, they all learned about that more enlightened form of selfishness known as “self care,” and recognized that putting yourself first can also help those around you. Hence, Gretchen and her therapy-related efforts to practice “mindfulness” in her daily life. Jimmy and his attempts to “find himself” in the latter half of the season by opening himself up to new experiences. Edgar working to get the VA to help him with mental-health treatment, partly because of the toll it was taking on his actress girlfriend, Dorothy. And Lindsay openly communicating with her husband about her sexual needs to preserve their relationship.

Even Edgar, the only main character who couldn’t be credibly labeled “the worst,” was forced to reflect and grow. Though he’d long functioned as the show’s main avatar for generosity, in the later episodes, especially after getting his PTSD under control, Edgar had to confront his own ability to indirectly hurt others. The main conflict between him and Dorothy in recent weeks was how he instantly landed a comedy-writing job, while Dorothy had been repeatedly overlooked despite working for years in a sexist and ageist industry. When Edgar tells her he had considered quitting the job for her, Dorothy—rightly—points out that he pities her, and that pity isn’t the same as love. After they break up, Edgar confides in Lindsay, “I think once she said [she wanted to end things], part of me wanted her to go. She was kinda bumming me out. How horrible is that of me?”

To Jimmy, family is just another kind of societal trap—one that is super normcore, but also one that obscures the way people relate to each other.

But the hard lesson of this third season was that neither selflessness, nor selfishness has entirely good consequences, because it’s impossible to fully disentangle one person’s well-being from that of another. Before, when the characters focused solely on themselves, the interpersonal fallout was expected, a natural consequence of their lifestyles. But by stepping up the moral stakes of the story and the moral capacity of its characters, You’re the Worst moved into more complex territory, one filled with contradictions, spurned good intentions, and a more informed skepticism of traditional bonds between people, including marriage and family.

In addition to self-improvement, the notion of “family” was a focal point of season three. Both Jimmy and Gretchen realize for the first time how their families played a role in screwing them up and making them so self-centered. Lindsay, too, fears striking out on her own, because she wants to be part of a family (a word she dreamily repeats to herself in most episodes). Eventually, Jimmy declares that he is “post-family,” claiming that, “Family is portrayed as a safe harbor, but nay: It is often the very Charybdis that yanks us to the fathoms.” That sentiment leads to the disastrous final act, where Gretchen calling them a “family” is enough to scare him away. Perhaps, to him, family is just another kind of societal trap, one that obscures how people relate to and care for one other. The concept is antithetical, in some ways, to what all the characters are trying to do: to give and take, to be selfish and selfless, but out of desire, not duty.

The season-three finale didn’t undo all the progress the characters made, though. While Jimmy and Gretchen were left in a moment of crisis, reevaluating their choice to break with their narcissistic natures, Edgar and Lindsay found comfort in nurturing one another. In their last scene together, they exchanged words that were somehow more shocking than the expletive-laden quips that fill every episode. “Are you okay?” Lindsay asked Edgar gently as he reflected on his recent breakup. “Are you sure you’re gonna be okay?” Edgar asked Lindsay moments later, as he helped move her into her new tiny, roach-infested studio to start a new life. Are you okay? Are you going to be okay? It was the simplest, smallest gesture of selflessness, but after nearly 40 episodes of watching You’re the Worst’s characters reaching ever new heights of egotism, those words meant everything.

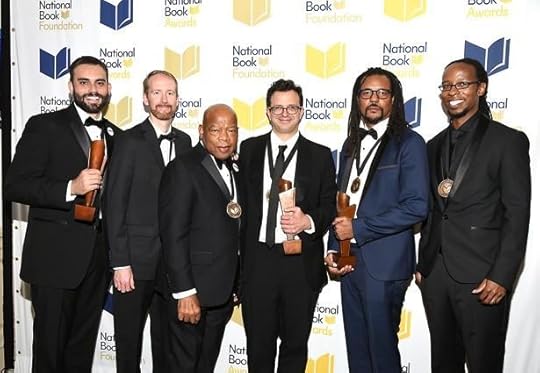

The National Book Awards Make a Powerful Statement

When John Lewis took the stage Wednesday night to accept the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for his graphic novel March: Book Three, the congressman was on the verge of tears. The book, co-authored with Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell, is the final installment in the trilogy that follows the civil rights movement through the eyes of Lewis, who was at its heart. “This is unbelievable … some of you know I grew up in rural Alabama, very poor, very few books in our home,” Lewis said, his voice shaking. “I remember in 1956, when I was 16 years old, going to the public library to get library cards, and we were told the library was for whites only and not for coloreds. And to come here and receive this honor, it’s too much.”

It was a powerful moment that set the tone for the ceremony, which went on to see three out of four of its categories won by African American authors (the Poetry award went to Daniel Borzutzky for The Performance of Becoming Human). It was a night that not only celebrated historically marginalized literary voices, but looked keenly toward what those voices mean, now more than ever. The specter of political turmoil, fear, and uncertainty about the future after a sharply divisive election hung heavy over the ceremony. But after a year when many people have looked to writers to make sense of the country’s political upheaval, the National Book Awards emphasized the importance of recognizing that the stories told by people of color, and African Americans in particular, are indelible parts of the American narrative.

The prize for nonfiction, awarded to The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates last year, went to the historian Ibram X. Kendi for his book Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Kendi’s work is a deep (and often disturbing) chronicling of how anti-black thinking has entrenched itself in the fabric of American society not solely through ignorance, but through a rationalization of inequity in institutional practices. Using the stories of five key intellectual figures—from Thomas Jefferson to Angela Davis—Kendi traces extensively, over the course of 600 pages, how history has woven racism into not just the consciousness of explicitly anti-black figures, but even the more subtly-rooted thinking of what he calls “assimilationists,” a group who oppose and fight racial inequity, but find blame in both the oppressed and oppressors.

Kendi thanked his six-month old daughter Imani in his speech. Her name means “faith” in Swahili, a word that he stated has a new meaning for him now as the first black president is about to leave the White House, and a man endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan is about to enter. Kendi talked about the burden of weariness he’s carried in digging through the darker chapters of American history for this book, and insisted he would keep faith in a new movement of protest against white supremacy and nationalism.

Perhaps the most eagerly-anticipated prize of the night, the award for fiction, went to Colson Whitehead, for his novel The Underground Railroad. The book, by an author previously recognized for his more fantastical work, was a heavy favorite after its glowing critical reception—to Whitehead’s own surprise—since it was published in the summer. The story follows Cora, a slave on a cotton plantation in the antebellum South who’s offered an escape via a secret network of tracks running beneath the ground. Whitehead takes a metaphor for a network of people who helped slaves escape northward, and turns it into a literal mode of salvation, as Cora moves frantically from state to state with a notorious slave-catcher hot on her heels. Accepting the award, Whitehead spoke with resolute hopefulness about what The Underground Railroad and the projection of black voices mean for those who must endure “the blasted hellhole wasteland of Trump-land” outside.

“Be kind to everybody, make art, and fight the power.”

Whitehead wasn’t the only person to reference the president-elect: The former Nightly Show host Larry Wilmore, who hosted the evening’s proceedings, wondered how a Trump presidency might affect the book world, speculating that all copies of the constitution would effectively have to be moved to the Fiction section, and Trump’s own writing re-categorized as Horror.

There are those who question whether or not awards like these are necessarily the means to validate or evaluate the power of literary voices, particularly when those voices are all male. The National Book Foundation—currently helmed by its first woman of color, executive director Lisa Lucas—may indeed represent a prestigious inner circle of an educated elite that was effectively left flailing this election. But there was something powerful about the palpable sense of community that transcended the evening. The Literarian Award, an honorary prize presented for outstanding service to the American literary community, was given to Cave Canem, a nonprofit that cultivates a platform for black poets. And though Whitehead, Lewis, and Kendi all told stories explicitly dealing with notions of black racial identity in America’s past, their works may be even more significant when it comes to navigating the future.

In these times of uncertainty, literature can be instructive, comforting, and inspiring. As Colson Whitehead movingly told the audience in his acceptance speech, his own advice for a Trump presidency is, “Be kind to everybody, make art, and fight the power.”

The Bloody Battle for Aleppo

The residents of rebel-held eastern Aleppo had lived without bombardment and explosions for three weeks. The Syrian and Russian governments placed a moratorium on bombing the city on October 18, a pause meant to let civilians evacuate, and to let weary fighters surrender or flee. Then on Monday, residents received a text message warning them to flee or face aerial attack. On Tuesday, Russian jets rained missiles down on neighborhoods surrounding Aleppo, many of them occupied by U.S.-backed rebel groups. By Wednesday, helicopters had dropped dozens of barrel bombs on buildings, including a children’s hospital and a blood-donation bank. At least 20 people were reported killed in the first two days, including several children, and the figure keeps rising as bodies are pulled from beneath the rubble.

Neither Syria nor Russia took responsibility for the bombings inside the city, but Syrian troops have deployed to the front lines as part of a renewed assault on Aleppo. For the rebels opposing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, the loss of Aleppo would mean their greatest defeat, and surrendering the country’s largest city back to the government. It’s a prospect made more complicated last week with Donald Trump’s election victory in the United States.

Trump has since spoken to Russian President Vladimir Putin, whom he has praised in the past. Details from Trump’s team on the conversations were sparse, but Putin’s spokesman said the Russian leader and Trump share a “phenomenally similar” outlook on foreign policy. On Tuesday, Senator John McCain from Arizona, who serves as chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, issued a statement warning Trump against becoming too close to Putin: “At the very least,” McCain said, “the price of another ‘reset’ would be complicity in Putin and Assad’s butchery of the Syrian people. That is an unacceptable price for a great nation.” The “reset” to which he referred was the ultimately unsuccessful attempt by the Obama administration six years ago to mend relations with Moscow.

Putin’s spokesman made it seem as if the Russian president and Trump were in alignment when it came to foreign policy, and had agreed “to join forces against the common enemy number one: international terrorism and extremism.”

But one of the largest terrorist threats, the Islamic State, has no presence in Aleppo, so the city’s bombardment isn’t about removing the group from Syria. Aleppo is essentially a mass of half-smashed buildings and streets coated in the gray dust of rubble, and the people who’ve remained behind are the holdouts of five years of brutal war—the kind who say they will never leave, and who still send their children to school every day.

When the war began in March 2011, Aleppo was Syria’s commercial hub. The civil war started at the height of the Arab Spring and has pit the government of President Bashar al-Assad, who is supported by Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah, the Shia militia group from Lebanon, against rebel groups that range in ideology from leftist to Islamist. Many, but not all, of these groups are backed by the U.S. and other Western countries, as well as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar, and other regional players. ISIS and groups linked to al-Qaeda are also involved in the fight against Assad. Although the Western nations and Russia are on opposite sides of the conflict, they both, separately, target these two groups and their affiliates.

Both the Syrian government and rebels want Aleppo, which has been divided since 2014. Rebels control eastern Aleppo, which Russia and Syria are targeting. Western Aleppo is under Assad’s control, and the government releases videos showing residents enjoying normal life. In the last year, with Russia’s help, Assad has taken back many of the areas ceded to the rebels and now appears more firmly in charge of Syria than at any point since the civil war began.

Humanitarian groups say Assad frequently targets public markets, mosques, and medical centers. The Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM) estimates that since 2011 more than 700 medical staff have been killed in attacks in Syria, and more than 250 medical facilities bombed. The city is also running out of simple goods like food, water, and medical supplies, and aid agencies say the 250,000 civilians holed up inside are in grave danger.

This week, Assad effectively targeted hospitals that saw around 23,000 people each month, and performed about 1,800 surgeries, UOSSM said.

An air strike hit a hospital on the city’s edge at noon Monday, closing the facility. Two hours later, another bomb hit a hospital, injuring a doctor and eight nurses. It is also now closed. That night, a strike hit a third hospital and killed two staffers. This hospital, too, is now closed.

Western nations, including the U.S. have strongly opposed Assad and say they want him out of power. Indeed, the United Nations condemned on Tuesday what it called the Syrian government’s latest human-rights violations. But with bombs falling “like rain” on Aleppo, the rebels on the back foot, and Assad bolstered, it’s unclear if there is enough international will to stop the carnage in Aleppo—and the rest of Syria.

The Battle Over Adult Swim’s Alt-Right TV Show

At a glance, Million Dollar Extreme Presents: World Peace seems like typical fare for Adult Swim, the alternative, late-night comedy channel that airs on the Cartoon Network after 9 p.m. One of a coterie of bizarre series on the channel, the show lurches from one surreal, sometimes violent, sketch to the next, and describes itself as being set in an “almost present-day, post-apocalyptic nightmare world.” But Million Dollar Extreme, which premiered in August, is also from the mind of Sam Hyde, an unapologetic member of the alt-right. Hyde crafts his comedy with the goal of shocking his young, liberal, Millennial audience while simultaneously appealing to like-minded members of a white-nationalist movement that generally supports Donald Trump.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Million Dollar Extreme has become a cultural battleground for its network since it launched. Though the show is currently off the air and awaiting a second-season renewal, some of Adult Swim’s other stars are demanding the show’s cancellation. Others are drawing attention to the network’s generally poor record on diversity, particularly with regards to promoting female comedians. Though the controversy over Million Dollar Extreme had been roiling before Trump’s Election Day victory, in its aftermath, the debate has become even more charged in the last week. Put simply: Watching Million Dollar Extreme sometimes feels like peering inside the mind of a far-right Twitter troll, as does looking at Hyde’s own feed. The question for Adult Swim is whether that’s enough to justify the show’s cancellation.

Buzzfeed’s Joseph Bernstein has reported on Million Dollar Extreme since it premiered. Bernstein drew attention to some of Hyde’s worst Twitter behavior (calling Lena Dunham a “fat pig,” mocking Black Lives Matter, and predicting the impending death of Hillary Clinton), and pointed out the TV show’s popularity with extreme alt-right communities like My Posting Career. Hyde’s past as a comedian includes an “anti-comedic” set where he read homophobic pseudo-science to a Williamsburg crowd and called them “faggots,” then posted a video delighting in their horrified reactions.

“Anti-comedy” is intrinsic to Adult Swim’s brand—that is, humor that seems to make a deliberate effort to not provoke laughs, to make its audience uncomfortable, and to challenge them with horrifying imagery and themes. Some of the network’s biggest hits, like Aqua Teen Hunger Force, The Eric Andre Show, and Tim and Eric Awesome Show Great Job! are masterpieces of anti-comedy.* Million Dollar Extreme borrows tropes from each of them—it’s abrasive, crammed with strange graphics and inter-titles, and its sketches careen from one weird theme to the next. There’s a political edge to much of the show, but its meaning is often intentionally oblique. Beyond that, of course, the whole enterprise seems cloaked in irony, which makes it easier for Hyde to dismiss any obvious connection to the white supremacy and extreme nationalism of the alt-right. (When Buzzfeed asked about his alt-right connections, Hyde replied, “Is that some sort of indie bookstore?”)

Still, there are plenty of sketches in Million Dollar Extreme that seem to exist only to shock and offend. In one, a man trips a woman and sends her flying head-first into a glass table, covering her face in blood— simply because he deems her too unattractive to marry his brother. In another, Hyde appears in blackface, screaming at a woman in exaggerated vernacular. In another, kids and puppets perform a song called “Jews Rock!” while executives watch, bored, from behind the stage. It’s easy to criticize comedy in isolation, and plenty of comedians from all over the political spectrum have faced ad hominem attacks where the media takes their jokes out of context. But Million Dollar Extreme seems crafted with intent. According to Bernstein, Adult Swim’s standards department have repeatedly found coded racial messages (including swastikas) in the show that they then removed. There’s also a groundswell of pushback within the network urging the executive Mike Lazzo to cancel the show.

The longer the show stays on Adult Swim, the more toxic its presence will be to other creators and comedians.

Brett Gelman, a brilliant and abrasive comic who has done work with Adult Swim in the past, announced this week that he was cutting ties with the network. In a series of tweets, he said that he was leaving out of disgust with Million Dollar Extreme, as well as the network’s poor record of working with women (all 47 listed creators on the network’s new and returning shows this summer were men). Tim Heidecker, the enormously influential comedian behind Adult Swim classics like Tom Goes to the Mayor and Tim and Eric, has voiced his support for Gelman’s decision.

The network’s official statement on the matter has remained consistent—every time Buzzfeed has questioned them about Million Dollar Extreme, the response has been the same: “Adult Swim’s reputation and success with its audience has always been based on strong and unique comedic voices. Million Dollar Extreme’s comedy is known for being provocative with commentary on societal tropes, and though not a show for everyone, the company serves a multitude of audiences and supports the mission that is specific to Adult Swim and its fans.”

According to Bernstein, Lazzo is iconoclastic enough not to care about the public pressure. Million Dollar Extreme is a relative hit for the network, drawing more than a million viewers in its late-night slot, and along with its passionate online fandom, perhaps that will be enough to keep it around. Still, this is a show where alt-right Reddit groups debate the to the former Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard David Duke that they notice in the show. The longer it stays on the network, the more toxic its presence will be to other creators and comedians—and the more the show will seem like a strange bellwether for the current moment in culture, where extremism looks to force its way into the mainstream. Million Dollar Extreme will never be a widely watched show. But after Trump’s surprising win, it’s clear that many comedians are no longer willing to hold their nose and ignore what they once had dismissed as a radical fringe.

Would you like to defend “Million Dollar Extreme” in a substantive way? Please send us a note: hello@theatlantic.com. (We will aim to publish it, anonymously, in Notes.)

* This article originally stated that Wonder Showzen was a show that appeared on the Adult Swim network; it aired on MTV. We regret the error.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower