Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 39

December 1, 2016

The Image in the Age of Pseudo-Reality

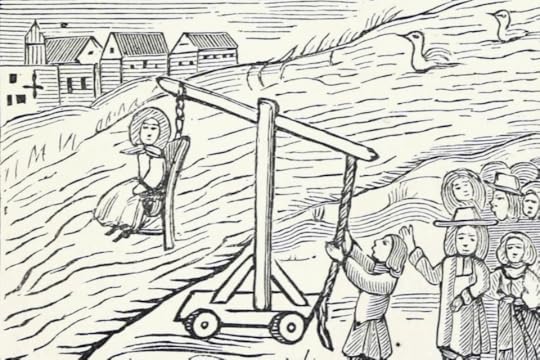

Phineas T. Barnum once displayed, in his American Museum in New York City, the corpse of a “mermaid” that was in fact the preserved head of a monkey sewn onto the preserved tail of a fish. He once advertised a large but otherwise extremely average elephant as “The Only Mastodon on Earth.” He once “displayed” a woman named Joice Heth as the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington (and as “The Greatest Natural & National Curiosity in the World”). He then wrote to newspapers to make a confession: Joice was not, actually, Washington’s nurse. She wasn’t even, in fact, human—but merely “a curiously constructed automaton, made up of whalebone, india-rubber, and numerous springs,” operated by a hidden ventriloquist.

An autopsy conducted just after her death would reveal that Joice Heth was, indeed, a person, one who was around 80 years of age. Barnum would admit to that, and to the many other tricks he had pulled in the name of public spectacle—or rather, he would boast about them—in a series of newspaper articles and, later, in Life of P.T. Barnum, the first of his four books. It was published in 1854, the same year Thoreau published Walden.

Barnum was one of the original creators and commercializers of the pseudo-event, the vaguely real-but-also-not-real thing that, the historian Daniel Boorstin argues, has been the fundamental fact of American culture since the days of Barnum himself. Or, at least, in the years between those days and the days of the mid-20th century. Boorstin’s book on the matter, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, was first published in 1962; it was, in its time, a blistering indictment of newspapers and television and Hollywood and the habit they all had of turning mortals into gods. (The indictment was so blistering that, when the book’s publication date found Boorstin abroad for a longstanding lecture engagement, a reviewer suggested that perhaps the author had simply decided to flee the country that he had so recklessly libeled.)

Boorstin, in The Image, coined not just the term “pseudo-event,” but also the epithetic descriptions “famous for being famous” and “well-known for well-knownness”; he was, it would turn out, an extremely reluctant herald of postmodernism. While The Image may have arrived on the scene, chronologically, before the comings of Twitter and Kimye and an understanding of “reality” as a genre as much as a truth, the book also managed to predict them—so neatly that it reads, in 2016, not just as prescience, but as prophesy.

P.T. Barnum understood, intuitively, how many things Americans find to be more enjoyable than reality.

“The image” is, in Boorstin’s conception, both literal (pictures, photographs, etc.) and figurative: a short-hand for images’ cultural primacy, and for an approach to reality itself that is blithely Barnumesque in its assumptions. The image, strictly, is a replica of reality, be it a movie or a news report or a poster of Monet’s water lilies, that manages to be more interesting and dramatic and seductive than anything reality could hope to be. The image is the spectacle that is most spectacular when it is watched on TV. It is the press conference and the press release—the media event that finds news being created rather than simply reported. It is the logic of advertising, with all its aspiration and transaction, insinuating itself into culture at its depths and its heights. It is the public expectation, even preference, for celebrities who are manufactured, as goods and as gods, because the only thing more compelling than stars themselves is our ability to question their place in our arbitrary firmament.

And, so: The image is fundamentally democratic, an illusion we have repeatedly chosen for ourselves until we have ceased to see it as a choice at all. The image gives rise, Boorstin argues, to a “thicket of unreality which stands between us and the facts of life.” It is not necessarily a lie, but—and here is the driving anxiety—it always could be.

Boorstin, before his death in 2004, taught history at the University of Chicago and served for more than a decade as the librarian of Congress; his polemic about Americans’ “feat of national self-hypnosis” is, then, fittingly panoramic in its vision. Boorstin traces our “arts of self-deception” to, specifically, the rise of photography in the mid-19th century, and to the public’s attendant ability “to make, preserve, transmit, and disseminate precise images—images of print, of men and landscapes and events, of the voices of men and mobs.”

Related Story

How Pop Culture Tells Women to Shut Up

Boorstin dubs this ongoing state of affairs the Graphic Revolution—images, he claims, are to us moderns what the printed word was to our forebears—and he attributes to its influence a dizzying array of pseudo-realities: the cheapening, and thus the wide availability, of printed books and magazines in the 19th century; the rise of the digest as a literary and journalistic form in the early 20th; the churning public demand for news and entertainment that arose from a glut of media sources; the rise of the celebrity as fodder for public conversation and speculation; the advent of image-driven modern advertising, which has encouraged, in turn, “our mania for more greatness than there is in the world.”

What those developments amount to, Boorstin argues, is a cultural attitude toward reality itself that is implicitly, and primarily, suspicious. (On advertising: “We think it has meant an increase of untruthfulness. In fact it has meant a reshaping of our very concept of truth.” On art: “As never before in art it has become easy for the great, the famous, and the cliché to be synonymous.”) We are living, still, he suggests, within the sparkle and the spectacle and the epistemic fog of P.T. Barnum—whose core insight, after all, was not just that people could be fooled, but that, in fact, they wanted to be fooled. Barnum set about to make people question not just his exhibits, but also him, as their creator. He paid rivals to publicly declare his antics to be false. He boasted that “the titles of ‘humbug,’ and ‘prince of humbugs,’ were first applied to me by myself.” He knew, long before many others would learn from his tricks, the profound power of epistemic destabilization. He understood, intuitively, how many things Americans find to be more enjoyable than reality.

And, so, the defining figure of the current technological and political moments—Boorstin, in the manner of his contemporaries, assumes that these moments are inextricably bound—might well be a guy who took the desiccated corpse of a monkey and called it a mermaid. It might also, however, be the many, many people who gave their money to Phineas Barnum in exchange for the thrill of being lied to. Today, living as we do in the shadow of a man who is most readily associated with gaudy circuses, Americans tend to take performance for granted as a feature of political and cultural life. We often assume that, since we ask politicians to entertain us as celebrities do, they will probably pretend like them, as well. Our leaders have, and indeed they are, “public images.” They are concerned primarily with that most ancient and modern of things: “optics.”

Boorstin worried that we don’t know what reality is, anymore. And, worse, that we don’t seem much to care.

It is no coincidence, Boorstin notes, that it was around 1850—the early years of the Graphic Revolution—that the word “celebrity” came to refer to a particular person rather than to a particular situation. Nor is it a coincidence that the revealing term “non-fiction” arose a little later: That was a response, Boorstin suggests, to the sudden explosion of fictional worlds that came, via books and magazines, to a democratized and newly literate American culture. The image, the stereotype, the ad, the manufactured spectacle, the cheerful lie … these are, he argues, all of a piece. They are evidence of Americans’ constitutional comfort with illusions—not just in our cultural creations, but in our everyday lives. Deceptions are our water: They are everywhere, around us and within us, palpably yet also, too often, invisibly.

Boorstin, with all this sweeping cynicism, occasionally veers into nostalgia and its common companion, cultural conservatism; his discussions of pseudo-events are often predicated on a definition of “event” that values high art, high ideals, and “authentic” experiences over other products of messy democracy. He conflates, sometimes, mass culture with pseudo-reality. He is anxious about artistic reproductions. He compares today’s image-oriented celebrities, unfavorably, to the action-oriented heroes of yesteryear. He harbors a sneaking suspicion, long before Barthes suspected the same, that the author is dead; he wonders whether authenticity itself might be, too; he looks around and is pretty sure that he sees, just beyond the haze, Hollywood starlets and their legions of fans dancing merrily on the grave.

And yet Boorstin also understood, long before Zuck and Jack and Ev were born, that “fake news” might one day help to win American elections, and that American journalists might soon enough find themselves arguing about whether tweets can be counted as news events. He knew that our penchant for illusions would change us, inevitably and irrevocably. He feared, far earlier than it occurred to others to fear it, that the center could not hold—that “The Greatest Show on Earth,” which is not a description so much as a dare, might portend an end of greatness.

Boorstin surveyed history and warned that, “long before Hitler or Stalin, the cult of the individual hero carried with it contempt for democracy.” He examined all the ways the world had devised to understand itself and concluded that, while “propaganda oversimplifies experience, pseudo-events overcomplicate it.” In his work, the anxieties expressed by Walters Benjamin and Lippmann—and, indeed, the wide-scale adjustments of vision made necessary by dictators and innovators and performers and frauds—culminate in a broad reality: We don’t quite know what reality is, anymore. And, more worryingly, we don’t seem much to care. Boorstin took history and philosophy and injected into it a clear-eyed assessment of human nature. He gathered Barnum and Mussolini and David Ogilvy and Marilyn Monroe and FDR and Plato, consulted with them, learned their lessons, and then came to a final, tragic conclusion: If Americans are living in a cave of our own making, even if we are offered the benefit of firelight, we might still choose the shadows.

November 30, 2016

The Sweeping Effects of Trump's Deal With Carrier

Donald Trump’s vow to stop Carrier from closing a factory in Indiana wasn’t the most ambitious promise he made during the presidential campaign, and it wasn’t the most prominent. But it was one of the most persistent. The tale of the company deciding to shut down the plant and move the jobs to Mexico became a standard element of Trump’s stump speech. It wasn’t just the Carrier plant, of course: His vow either to convince the company to stay in the United States or else slap it with a huge tariff was symbolic of the protectionist view he expounded for trade. It was also a key test for his claim that the negotiation skills he said he’d honed in years of business could produce results.

Related Story

Why It’s So Hard to Know What to Make of the Carrier Deal

That makes the deal that Trump has apparently struck to keep the jobs in Indiana a major political win—the president-elect fulfilling a major promise well before he takes the oath of office. He is a successful bully even before he takes his pulpit. It’s a sign that the theatrical, blustery persona that Trump struck on the stump can be translatable, in at least some cases to the presidency.

As my colleague Alana Semuels writes, there’s still a great deal to question about the deal and its implications. For one, Trump had unusual bargaining power in this case, because Carrier’s parent company, United Technologies, depends heavily on federal-government contracts. For another, Trump seems to have gotten the deal by promising tax credits to Carrier. That creates a potential moral hazard, since while some executives may decide not to outsource to avoid a public battle with the president of the United States, others may reason that by threatening to move jobs out of the country, they may also be able to extract profitable benefits. Meanwhile, Fortune reports that Carrier is still moving 1,300 jobs to Mexico, versus 1,150 that will be preserved in Indiana.

Even if the long-term benefits are limited, however, the immediate political win for Trump is big. The workers whose jobs are preserved, and their families, and everyone else in the community, will feel the immediate impact of those jobs staying, while the pain will be spread widely and over time.

It may be a qualified win, but the Carrier deal suggests that Trump’s promises of greater federal intervention in the economy were not just posturing. It could open the door for Trump to take a much more active role in the economy, not simply through fiscal policy but through direct involvement with specific companies.

To see just what a shift this is, it’s useful to look back to the end of George W. Bush’s presidency and the beginning of Barack Obama’s. Late in George W. Bush’s term, the federal government reached a deal to bail out financial institutions. Shortly after taking office, Obama reached a deal to save General Motors. Each of these cases was treated as exceptional, a view that was generally accepted even by those who opposed the actions the government took. The argument for these serious deviations from orthodoxy was that both the financial system and GM were systemically important to the American economy, and that allowing either to fail would have grave domino effects.

Carrier is different. The case at hand involves a single factory, with a limited number of jobs that, while important to those involved, are not a linchpin of the national economy. The strongest case for national impact that can be made is that Carrier can be made an example that will dissuade others, a tenuous argument.

Trump’s direct involvement is striking because the Republican Party has traditionally been so resistant to government meddling in private enterprise. But even the Democratic Party, which is generally far more friendly to regulating business, has avoided many direct interventions as public as Trump’s in this case. That held true even at the height of the recent financial crisis.

Trump may have more political leeway to act for a few reasons. Unlike Obama, he is not likely to be labeled a socialist. Moreover, despite then-Obama aide Rahm Emanuel’s famous declaration that “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste,” Trump may paradoxically benefit from the fact that the economic sky is not falling. At the height of the crisis, panic constrained Obama’s ability to act. After eight years of stability and slow but steady economic growth, however, there’s no longer the same sort of constant scrutiny on government actions.

There’s one other element that makes Trump’s negotiation with Carrier politically intriguing. One of Trump’s innovations was to espouse economic populism without actively courting unions, which are both loathed by many Republicans and deeply enmeshed the the Democratic Party. Instead, he looked to court voters who were members of unions, splitting them from labor’s leadership, which was largely telling them to support Hillary Clinton.

During the GM bailout, the United Autoworkers were a central player in negotiations. Autoworkers agreed to a pay cut as part of the deal, and a health-care trust for UAW retirees, whose leaders are partly appointed by the union, received shares in the reorganized company. In contrast, the head of the union representing Carrier workers complained on Wednesday that he and other leaders had been kept entirely in the dark about the deal. If Trump demonstrates that he can and will save manufacturing jobs without union involvement, it will further undermine the strength of organized labor. In the long run, that may be bad for workers, since higher rates of unionization correlate with a range of benefits for workers. But in the short term, it will be much worse for the Democratic Party, because it will sap strength from one of the party’s most important constituencies.

Incorporated Is a Timely Drama About Corporations Gone Wild

The timing of Incorporated, SyFy’s chilly new show about a dystopian future ravaged by climate change and corporate power, is certainly interesting. On the one hand, its repeated nods to current events—a wall constructed by Canada to keep out American refugees, self-driving cars, Miami falling into the ocean—land with sometimes unnerving emphasis. On the other, the series is the exact opposite of the escapist fodder many TV viewers might be craving. But the seven-part show, debuting Wednesday night and executive produced by Ben Affleck and Matt Damon, is surprisingly compelling, even if its premise and motifs are nothing new. And the performers, including Julia Ormond as a ruthless CEO and Dennis Haysbert as her head of security, add nuance to a plot that isn’t as transparent as it initially seems.

The conceit for Incorporated, rolled out perfunctorily via a few opening title cards, is that the year is 2074, and climate change has ravaged the planet, toppling governments and devastating once-powerful nations. Corporations, stepping in to fill the power void, now control 90 percent of the world. In Milwaukee, where the drama is set, their senior employees and executives live in sterile, neatly manicured Green Zones; everyone else lives in Red Zones, which are grimy and sordid approximations of an internet black market come to life, teeming with drug dealers, sex workers, orphan children, and techno.

Ben Larson (Sean Teale) is an executive at Spiga, a multinational biotech company run by his mother-in-law, Elizabeth (Ormond). His wife, Laura (Allison Miller) is a plastic surgeon suffering from PTSD after she was kidnapped in the Red Zone years ago. But Ben is also a sleeper agent infiltrating Spiga for reasons that aren’t entirely clear in the first few episodes. His main goal seems to be to find Elena (Denyse Tontz), a childhood friend of his from the FEMA camp they were both housed in as children, but given the extent of his subterfuge (marriage, potentially children, working a bazillion hours a day for a company that regularly tortures its own employees at the slightest hint of malfeasance), it’s likely there are other factors at play.

If Incorporated shares a sense of cynicism and misanthropy with another speculative sci-fi show, Black Mirror, it has none of that series’ bleak humor or psychological horror. Instead, it feels more inspired by USA’s Mr. Robot, with Peale’s dark-eyed allure and his character’s shaky motivations dominating much of the action. It also shares that show’s sterile treatment of corporate stooges, contrasting the trappings of wealth and power (clean, sanitized design; $600 cuts of meat) with the ugliness of life on the other side. But Incorporated seems intent on emphasizing that no one in the Green Zone is free—their lives come courtesy of the companies they work for. Even the most personal decisions (whether or not to procreate) are subject to approval, and even minor transgressions at work are potential grounds for catastrophic punishment.

Although the primary plot of Ben’s mission to find Elena isn’t particularly absorbing, the subplots and extras are mostly intriguing. In one episode, a woman for a rival firm informs Elizabeth that, having seen how her own firm indoctrinates the children of its workers, she wants to defect to Spiga. The operation to help her abscond is a thrilling one that further blurs lines between heroes and villains. The opening sequence of the fourth episode is narrated entirely in Japanese, filmed as a pastiche of a fundraising appeal to help starving children like “Johnny” in America, now one of the world’s poverty-stricken nations. And the show’s continual references to the effects of global warming (the best champagne is now Norwegian, Anchorage is a balmy coastal paradise, Ivy League schools have moved west) are as anxiety-inducing as they’re imaginative.

Incorporated is created by the Spanish screenwriting brothers Alex and David Pastor, who tackled similar themes of economic disparity and futuristic nightmares in the flat 2015 movie Self/Less, starring Ryan Reynolds. While their new show offers a vision of the future that isn’t particularly original, its plot is energetic, and its visuals are sleek and appealingly stylized. Depending on how its nightmarish scenarios play out, it has the potential to be a bracing drama set in a world only a few degrees removed from this one.

The Anxiety of a Starboy

What a perfect name the Weeknd’s new album has: Starboy. Abel Tesfaye, the 26-year-old Torontonian whose Michael Jackson-like croon and Marquis de Sade-like lyrics have become ubiquitous on the radio in the past few years, says the term is inspired by David Bowie’s “Starman” and refers to “a braggadocious kind of character who we have inside all of us.” But on its own, “starboy” sounds like a sneer meant for certain male celebrities, guys whose macho pretensions are—fairly or not—undercut by fame. You can imagine hecklers calling Drake “starboy” as he grunts on stage about how wrong all those memes about his wimpiness are. You can imagine hearing a “starboy” comment from the glowering method actor Christian Bale, who once described his profession as “sissy.”

And now Tesfaye is grappling with starboydom. His career began in 2011 with a string of indie releases that took R&B’s sex obsession to a dark and lewd extreme; the mannered, almost angelic quality of his voice made his narratives about disposable women and expensive drugs seem all the more sinister. The music’s appeal as noir was powerful, but it was niche. Yet last year’s Beauty Behind the Madness enlisted superproducer Max Martin in an all-out effort to turn Tesfaye into the biggest singer in the world; the resulting blend of catchiness and depravity worked better than most people predicted. As drive-time listeners shouted along to Tesfaye’s line “When I’m fucked up, that’s the real me,” the production—muffled screams, damp-cave echoes—signaled it wasn’t simply a carefree partying slogan.

A year later, though, he’s back with a newly squeegeed sound that pays crisp homage to Off the Wall disco and yacht rock. As fun-time pop, the songs frequently deliver. But as art and as marketing, problems have started to seep in: Does anyone believe a guy describing his sociopathic sexual habits when he’s doing so over smooth, lavish bubblegum? Sometimes, it sounds like Tesfaye’s overcompensating for his new direction, throwing out horrible lines like “David Carradine, I’ma die when I cum” to prove he’s still got edge. The more effective moments have him flirting with self-deprecation. On “Reminder,” he sounds embarrassed to have won a Teen Choice Award for a song about “a face numbing off a bag a blow” (you probably know the one). For the title track, as a Daft Punk beat patters behind Tesfaye’s overtly campy puns about cars and coke, he chides the world for having turned him into a “motherfucking starboy.”

The tradeoff Tesfaye has made is in the name of musical freedom, allowing him and his producers to sound as perky as they want while they borrow tropes from the late ’70s and the ’80s. For “False Alarm” Tesfaye dons an amusing Oi! punk costume; on “A Lonely Night” he goes Bee Gees, crooning his syllables so quickly that they blur. The excellently bittersweet “Secrets” explicitly references to a clutch of New Wave classics, and “Rockin” repackages some of the flavor of Jackson’s “Rock With You” for a modern raver’s palette. Even the more traditional-seeming Weeknd songs about being a cad feel polished: “Party Monster” is like a trap-rap take on the Stranger Things soundtrack, with a chorus that turns a boilerplate Tesfaye line—“woke up with a girl, I don’t even know her name”—into a “Ring Around the Rosie”-style chant.

The shine of these songs only slightly distracts from the maddening character who’s always been at the heart of the Weeknd, a character who unapologetically embodies many of pop culture’s pathologies, especially around gender. Outside of his own promiscuity and luxury tastes and general dead-insidedness, his favorite lyrical topic is the promiscuity and luxury tastes and general dead-insidedness of certain women—women who, unlike him, are on the wrong side of the line between wicked and wicked-cool. Tesfaye does sometimes seem aware of the double standard, and he might argue he’s not dissing the girl-about-town archetype but rather paying tribute: game recognizing game. A few songs late in the album complicate his persona—“tell ‘em this boy wasn’t meant for lovin’” he once sang—by yearning for monogamy from someone too cool to commit. “You made me fall again, my friend,” he sighs over door-knocking percussion and moony synths on “Love to Lay.” “How can I forget when you said love was just pretend?”

The you, intriguingly, is embodied by a specific person throughout the album: Lana Del Rey, the singer who has seemed to serve as Tesfaye’s female foil when it comes to ravishing pop music about super-regressive relationships. In an interlude, she is identified as a “stargirl,” who can only, it’s implied, find happiness with a starboy like Tesfaye. But the comparison between them is more interesting for its contrasts. Her career has seen her wander further and further away from radio-readiness as she commits ever-more-fully to the queasy persona she’s constructed. His has seen him aim for bigger and bigger audiences while straining to maintain his antiheroic shtick. The difficulty of that task colors Starboy, adding hints of anxiety to songs meant to telegraph confidence. Which, again, fits the album’s name.

'Officer Vinson Acted Lawfully When He Shot Keith Scott'

Officer Brentley Vinson will not face any criminal charges in the shooting death of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina, in September, a prosecutor announced Wednesday morning.

Mecklenburg County District Attorney Andrew Murray said during a press conference that Vinson, an officer with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department, had acted reasonably in firing on Scott, whom Murray said had a handgun and was brandishing it in view of the officers. He said he had met with the Scott family earlier on Wednesday and that relatives had been “gracious.” He said the event was tragic and that no one should have to deal with it.

“It is my opinion that Officer Vinson acted lawfully when he shot Keith Scott,” Murray said. He said that 15 career prosecutors had unanimously agreed on the decision.

The shooting set off several days of protests, some violent, in Charlotte this fall. They laid bare strains in the relationship between the Charlotte-Mecklenburg police and the city’s African-American population, as well as lingering racial and socioecononic tensions in the rapidly growing economic center. Scott’s was one in a string of cases in which police officers shot a black man under debatable circumstances, and protestors suggested that police had been too hasty in firing.

Murray gave a detailed timeline of the shooting, which was captured in part by police body cameras, at Wednesday’s press conference. He said that two officers, including Vinson, who is black, were in an unmarked van and wearing plainclothes, doing surveillance, when Scott pulled up next to them. They believed he was trying to look into the car, but then drove away. Murray showed surveillance video from a convenience store, and said that a bulge visible on Scott’s right ankle was a holster. According to police, Scott returned to the scene and parked next to the unmarked van. He opened his door and emptied tobacco out of a cigarrillo, then proceeded to roll a blunt with marijuana.

The officers said they did not intend to apprehend Scott for such a minor offense, but then saw him with a gun in his car, and decided to leave the scene and return with marked cars. While Scott, a convicted felon, was not legally allowed to own a gun, officers did not know that at the time, and North Carolina is an open-carry state. Murray said police returned and made contact with Scott. Officers said they saw Scott reach for his holster. The prosecutor rejected speculation, based in part on analysis of photos from the scene, that Scott was unarmed, saying that several officers saw the gun and it was recovered, with Scott’s DNA, at the scene, although Murray acknowledged that videos do not show the gun in Scott’s hand. Murray said officers ordered Scott to drop his gun at least 10 times, which he did not do as he exited his SUV, and so Vinson shot Scott four times, striking him in the wrist, abdomen, and shoulder. Murray said that no other officers fired.

Scott was taking several medications, and officers said that he appeared to be in a “trance-like” state, consistent with the side effects of some of those medications.

It’s unclear whether Murray’s report with satisfy critics of Scott’s shooting. Vinson, who shot him, is African American, but several high-profile cases of shootings of black men around the nation have involved black police, and activists point out that the race of officers has no bearing on statistics that suggest disparate use of deadly force against black men in the United States. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Chief Kerr Putney, who is also black, said ahead of the announcement that his officers were ready for whatever reaction met the decision.

On Wednesday, Murray said, “I know that some out there are going to be frustrated. I want everyone in this community to know that we meticulously, thoroughly reviewed all of the evidence in this case, made sure it was credible evidence, in order to make the decision that we made today.” He also scolded the public, calling on them to read his full report and warning them not to “react viscerally on news snippets.”

But Murray acknowledged “long-simmering frustration” in the community, and rejected the refrain, sometimes heard in the midst of protests, that the demonstrations did not reflect the city as it was known.

“This is Charlotte. This is where our friends, families, neighbors, and colleagues felt so passionate that they marched on our streets to call for change,” he said.

He said he would not hesitate to prosecute an officer in a case where it was justified, and added, alluding to race, “Throughout our justice system people should have the same experience.”

Tom Brady, Sociologist of Religion

It turns out football players aren’t half-bad sociologists. Religion of Sports, a new TV documentary series, is the work of three odd bedfellows: Tom Brady, the ultra-famous New England Patriots quarterback; Michael Strahan, the former New York Giant and current Good Morning America co-host; and Gotham Chopra, the filmmaker and son of Deepak Chopra, the New Age, self-help, alternative-medicine-advocating guru. Over six episodes, the show, which airs on DirecTV’s Audience network, follows athletes and fans from the worlds of NASCAR, rodeo, Mixed Martial Arts, baseball, soccer, and online multi-player video games. The theory, as you might guess from the title, is that sports, broadly constructed, are a kind of religion. As Chopra intones during the introduction, with images of stadiums and religious pilgrimages rolling by, sports “have believers, priests, and gods. They have rituals, miracles, and sacrifices. Sports unite us. They are a calling.”

Chopra is, at best, working in loose metaphor. Defining “religion” is devilishly difficult, and broad categories like “Hinduism,” “Islam,” “Christianity,” “Judaism,” and “Buddhism” encompass immense diversity of belief and practice. The new series stretches the word “religion” almost to the point of meaninglessness; likewise, “priests” and “gods” may be poetical ideas and useful figures of speech, but they’re not very precise descriptions for figures like the racing giant Dale Earnhardt Sr. or the revered MMA fighter Anderson Silva.

This conceptual nitpick isn’t meant to undermine the project, though. In parsing “the religion of sports,” Chopra and his star-powered co-producers are trying to understand a resilient form of meaning making and community formation in the United States. It seems a little silly to group Chopra and co. with social theorists like Alexis de Tocqueville and contemporary scholars who worry that America’s community structures are fraying. But, incredibly, that’s the project they’ve created: a sort of jock’s guide to civil society. While the series can, at times, come across as a rosy-eyed passion project, its central insight—that sports can be understood as a way that people find belonging—reveals a rich theme for artists who seek to grapple with the strong sense of cultural division and isolation experienced today by Americans of different ethnic, class, and political backgrounds.

While Strahan and Brady apparently brought athletes’ perspectives, along with prestige and access, to the series, Chopra seems to be the project’s main driver. When he set out to make the documentaries, he told me, he was inspired by shows like This American Life: “Sports is the backdrop, but we’re trying to find great stories.” In one early episode, a Marine who lost both his legs in Afghanistan, Joey Jones, describes how important NASCAR is to his family. In another, Cat Zingano, an MMA fighter, describes the way her husband’s suicide made it difficult for her to keep competing. Scenes toggle between emotional interviews and action on the field or in the ring; shots of sweat-filled training sessions are mixed with archival footage of hospital visits and home movies. The series apparently wants to be artsy enough for the documentary crowd with sufficient drama to satisfy casual channel flippers—intriguing for sports fans and sociology nerds alike.

“The sports fan is the easy audience. [The nerds] are more the audience that I’m interested in,” Chopra said, going on to describe himself as the lone sports enthusiast in a family of intellectuals. He sees this series in part as an answer to people such as his wife, who couldn’t understand why he spent weeks in despair after the Red Sox lost to the Yankees in 2003. His father, Deepak, is “not only … not involved in the project—he’s not a sports fan, at all,” Chopra said. “He’s one of those people who’s like, ‘Wait, what? Why do these guys get paid so much money, and why do people care so much? Why are they wearing their hats backward?’”

“I hate the word ‘self-help,’ which is ironic [given] the family I’ve grown up in.”

At times, the series seems to draw directly from the Chopra family tradition; each episode opens and closes with Gotham’s voice pronouncing wise-sounding aphorisms like, “As long as there are those who dare, there will be those who soar,” and “Sacrifices often go unanswered. No matter how much is given, the answer is silence.” Despite this tendency, Chopra claims to “hate the word ‘self-help,’ which is ironic [given] the family I’ve grown up in.” Most of the time, he avoids diagnosing and narrating his subjects’ spiritual lives, instead letting them describe their own relationships to sports. And that’s where things get interesting.

“Sometimes, especially when money isn’t very prevalent, and the way you make money is hard-earned, it’s a 9-to-5 paycheck, you need something that brings your community together,” says Jones, the Marine, in the NASCAR episode, which aired before Thanksgiving. “There are a lot of places where that’s ... religion, and going to church on Sunday. But for this part of the world—for where I grew up at—your church is on Saturday night."

It’s possible Jones chose that comparison because he was being interviewed for a documentary about religion and sports, but it’s fascinating nonetheless. In a lot of ways, sports do resemble the structure of religion and other communal activities. For fans, they lend a rhythm to the calendar year; they provide a space for meeting and socializing with people who have common interests; and they offer shared experiences of excitement and disappointment and hopefulness. For athletes, sports can provide spiritual-like experiences of “being in the zone,” and they require extreme amounts of physical and mental discipline.

Chopra takes this literally: “Sports is an actual faith. It’s not even metaphor. It’s real. You practice these things,” he said. This is debatable—Chopra is looking at religion purely as a matter of practice, while discounting the importance of belief. Sports are not about the metaphysical nature of the universe; they provide no guidebook for the self or community in navigating life.

But, to embrace Chopra’s interpretation of “religion” for a moment, it’s curious to consider the ways in which sports participation has not followed the same trend line as other communal activities. According to organizations like Pew, traditional religious affiliation is steadily declining in the United States; participation in civil-society groups like bowling clubs or parent-teacher organizations has gone down significantly as well. As Americans have pulled away from these kinds of community institutions, their love of sports has stayed relatively constant: According to Gallup, the percentage of Americans who call themselves “sports fans” has hovered around 60 percent for at least the last 15 years.

One reason Americans’ steady interest in sports doesn’t mirror their declining interest in fraternal groups or religious organizations might lie in the nature of the activity: While sports are a form of communal bonding, they are also a form of consumption and entertainment. Although public polling is an imperfect tool for understanding people’s identities, Gallup has found that people with incomes greater than $75,000 are significantly more likely to identify as sports fans compared to their less wealthy peers. And this makes sense: Things like season football tickets or rodeo gear require a lot of cash. Just as many people’s religious experiences are mediated through fallible institutions, many sports fans and athletes give their money, time, and bodies over to large, profit-making companies like NASCAR and the National Football League. It’s a privileged kind of communal bonding, a fact that Chopra, who calls himself a “true believer” in the religion of sports, doesn’t necessarily emphasize.

Romantic though Chopra’s take on sports may be, it’s still a satisfying starting point for artistic investigation. The series takes leisure seriously as a way that people of different backgrounds might find kinship, at a time when doing so seems nearly impossible. Every year, Chopra said, he tries to hit up a Red Sox game at the opening of the season. “I sit in those stands, and I look across the ‘congregation’ … and I’m like, ‘I don’t know how much I have in common with these people anymore,’” he said. “And yet in this one thing, for these three hours, we have something in common: We share a mythology. We share a belief system. We share an experience. ... I wish we could have more of it right now. I think we need it.”

November 29, 2016

In Scientology and the Aftermath, Leah Remini Strikes Back

The last ten years haven’t been easy for Scientology. After the religion/self-knowledge practice/tax-exempt corporation arguably peaked in 2006 with the spectacular Italian wedding of its most famous congregant, Tom Cruise, the Church since then has faced a barrage of reports alleging nefarious practices—from physical violence committed by senior executives to widespread harassment of people seen as enemies of Scientology. Going Clear, a meticulously reported book about the organization by The New Yorker’s Lawrence Wright, was a finalist for the National Book Award for Nonfiction, while a documentary based on the book by Alex Gibney was nominated for an Academy Award. And several of Scientology’s celebrity members—the Church’s most powerful recruitment tool—have quit, none in a more high-profile and outspoken fashion than Leah Remini.

Remini, the former star of The King of Queens, left the Church in 2013, after a series of incidents that she says compelled her to question the integrity and hierarchy of an institution she’d grown up in. In 2015 she published Troublemaker: Surviving Hollywood and Scientology, a biographical account of her personal history with Scientology, and the events that led Remini and her family to abandon it. In the introduction, Remini seems to anticipate that the Church’s well-documented practice of attacking its critics might make her a target, and lists her own personal failings in considerable detail. “After the Church of Scientology gets hold of this book, it may well spend an obscene amount of money … in an attempt to discredit me by disparaging my reputation,” she writes. “So let me save them some time.”

Remini’s fierceness, her unshakeable resolve, and her attack-dog instincts certainly make her a worthy opponent for the “religious system” founded by the science-fiction author L. Ron Hubbard in 1954. As the most high-profile public figure to denounce Scientology, she has the ability to reach audiences who don’t read The New Yorker, or watch HBO. It’s this reality that makes her new eight-part documentary series on A&E, debuting Tuesday night, noteworthy, even if it isn’t particularly artful. Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath seems to be aimed at an entirely different audience, mired as it is in the reality and true-crime formats of shows like Intervention and The First 48. Almost everything Remini reveals in the show’s first episode has already been reported. But by continuing to speak about her own experiences within the organization, and by seeking out others to tell their stories, Remini offers some insight into the tactics of an institution whose power and cultural impact seem to be on the decline.

That said, the legal might of Scientology remains forceful, at least judging by the lengthy disclaimers that precede each segment of the show. (“The Church disputes many of the statements made by Leah Remini” becomes as reliable a presence in the first episode as Remini herself.) For 35 years, Remini explains, she was a faithful Scientologist, but she became compelled to expose the truth about this “billion-dollar corporation/cult/religion.” She was nine, growing up in Brooklyn, when her mother joined the organization. “The promise is that you will reach your full potential in every aspect of your life,” Remini explains. “This is an organization that will save the planet from crime, from war, from people hurting each other.” After her stepfather left, the family moved to Los Angeles. Once Remini became an actress, her personal success and her success within Scientology were inextricably linked, thanks to the organization’s emphasis on using its techniques to reach your highest goals.

Remini’s presence is compelling (and frequently wacky), while her outrage at the institution she grew up in seems deeply felt.

From there, Remini briefly details her disillusionment with the Church following Cruise’s wedding to Katie Holmes in 2006, after which Remini was taken to task by Church leaders for asking why the rarely seen wife of Scientology’s leader, David Miscavige, wasn’t present at such a high-profile event. (Remini eventually filed a missing-person report for Shelly Miscavige, which the LAPD closed in 2013.) “The response spoke to the person in me that doesn’t like to be bullied,” she says. While her departure wasn’t as instantaneous as the show makes it seem (it was seven years before she left for good), her public disavowal of Scientology led others to contact her for help, leading her in turn to seek out their stories. And that’s basically the format of the show: Remini, in a car, driving to meet ex-Scientologists and to record their experiences.

It isn’t hugely dynamic as a viewing experience, with a heavy reliance on talking-head interviews, archival footage of Scientology events, schlocky B-roll footage, and basso profundo sound effects to indicate tension. But Remini’s presence is compelling (and frequently wacky), while her outrage at the institution she grew up in seems deeply felt. Among the allegations made by interview subjects in the first episode are statutory rape and emotional and physical abuse. There’s also some analysis of a practice called “disconnection,” in which Scientology forces members to cut off any family or friends who turn against the Church. “I feel a lifetime of responsibility,” Remini says at one point. “I helped to promote this organization, I defended it, I helped people stay in it. I have some making up to do.” While Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath isn’t as intricately reported or as compelling as some of the recent exposés about the Church, it’s a valuable continuation of efforts to shed light on some of its most egregious practices.

The Republican Vogue for Stripping Citizenship

Another day, another Trump tweet sending the political discourse into a tizzy. The president-elect’s latest outburst concerns flag-burning:

Nobody should be allowed to burn the American flag - if they do, there must be consequences - perhaps loss of citizenship or year in jail!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 29, 2016

The proximate cause for his tweet seems to be a contretemps at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, where earlier this month students lowered the American flag to half-staff in protest of Trump’s victory in the presidential election. One student reportedly burned a flag as well. In response, the college decided to remove the flag. On Monday, veterans staged a protest of that action.

As usual, who knows how serious Trump is? The Supreme Court has been clear that flag burning is a constitutionally protected right. There have been various attempts to amend the Constitution to bar it, with the last failing by a single vote in the Senate in 2006. If you take Trump’s imprecations about “political correctness” during the campaign seriously, it’s hard to square them with such a draconian reaction to flag burning.

Related Story

What’s more interesting is the sanction that Trump proposes: “loss of citizenship or year in jail,” an almost comical equation of the penalty for, say, forging a notary seal with the forfeiture of citizenship, and all of this simply for a speech act, albeit one that many Americans find deplorable. Depriving someone of their citizenship is one of the harshest sanctions a government can levy—not as lastingly grave as execution or life imprisonment, perhaps, but still very serious, especially for someone who is not a dual citizen and would therefore be left stateless. (It’s a situation that Edward Everett Hale dramatized in his famous short story “The Man Without a Country,” published in The Atlantic in December 1863.)

Yet recent years have seen a vogue among Republicans for proposing to strip citizenship as a punishment for various crimes. In 2014, Senator Ted Cruz, a Trump frenemy-turned-enemy-turned-supporter-turned-rumored-appointee, proposed stripping citizenship from any American, native-born or naturalized, who declared allegiance to a foreign terrorist organization, became a member of such an organization, or provided training or material assistance. Senator Rand Paul floated a similar proposal around the same time. Earlier this year, Newt Gingrich, a close Trump adviser, called for stripping citizenship from and deporting any Muslim who believes in sharia law, a proposal that is impractical, nonsensical, and virtually guaranteed to be unconstitutional. Somewhat more perplexingly, Ben Carson called in a 2014 column for non-citizens who vote fraudulently to be stripped of the citizenship they don’t possess.

A different but related current is the occasional call, usually from Republicans, for an end to birthright citizenship, which grants American citizenship to anyone born in the United States—most notably to the children of immigrants, whether authorized or not. Ending birthright citizenship was one of the earliest policies that Trump rolled out in the summer of 2015, saying, “This remains the biggest magnet for illegal immigration.” Several of his rivals for the Republican nomination announced that they agreed with him.

The frequent proposals from conservatives and Republicans to strip citizenship as a punishment for a range of crimes—or in the case of birthright citizenship, for the crimes of one’s parents—illustrates a partisan difference in how citizenship is viewed. Progressives tend to think about citizenship as a right that, if acquired legally, cannot be taken away, even for heinous crimes. It is nearly absolute. Conservatives, however, tend to view it as a privilege, and while it might be the default, it can still be withdrawn, as in the case of Americans who join terrorist groups. The right tends to view the left’s version as insufficiently patriotic, but it’s simply a different view of patriotism, and perhaps one that is more constitutionally grounded.

(In a separate and controversial move, President Obama decided he could kill American citizens fighting for terrorist groups overseas, such as the radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, without trial—thus depriving Awlaki of another of his rights—a decision that was decried by civil libertarians.)

Birthright citizenship is one of those areas in which the United States is unusual—even exceptional. Just 33 countries around the world offer it. The legal matter has been more or less settled since 1898, when the Supreme Court ruled that children of foreigners who are born in the United States are, according to the 14th Amendment, citizens, though some scholars have argued that does not cover unauthorized immigrants.

Stripping citizenship is another area in which the United States has taken an exceptional stance. Governments from oppressive Middle Eastern police states to Western European countries have used the tactic as a punishment for various crimes. Libertarian journalist Matt Welch suggested in late 2015 that there’s a global trend toward it. In 2014, the United Kingdom established the maneuver for terror suspects, and Australia did the same a year later. French President Francois Hollande this year dropped a similar proposal, brought up after terror attacks in 2015, in the face of opposition.

Doing the same in the United States would likely be impossible. The Supreme Court ruled in Afroyim v. Rusk in 1967 that American citizens could not be stripped of their citizenship involuntarily. Wikipedia has a useful though incomplete list of those who have had their citizenship stripped. Generally, those cases in recent decades fall into a three clear, sometimes overlapping, groups: spies, former Nazis, and those who acquired their citizenship fraudulently, i.e., by lying during the naturalization process. Even Emma Goldman, the famed anarchist leader, was stripped of her citizenship not explicitly for being an anarchist, but on a technicality: She had obtained citizenship through marriage to a man who was a naturalized citizen, and the government determined that the ex-husband had fraudulently obtained his citizenship, thus invalidating hers as well.

Throughout the 1950s, as Atossa Araxia Abrahamian wrote in Dissent in 2013, there were plenty of cases of Americans, both naturalized and native-born, who were stripped of their citizenship for having various foreign ties. But the Supreme Court eventually stamped that practice out in Afroyim. Some conservative legal scholars have argued for a new legal regime in which citizenship could be stripped in certain circumstances. Richard Epstein, a law professor at the University of Chicago, frames the conservative case for citizenship as a privilege this way:

Think of the United States as a quasi-partnership, which has to set its rules for the admission and exclusion of its member citizens. I know of no private association that states that an individual can lose his place in the firm only if he voluntarily resigns. Virtually every well-drafted agreement understands that these relationships depend upon trust, an thus allows a forcible removal for cause.

Epstein reasons, “The same for-cause rule applies to common carriers who have to take all customers on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms. Even they can exclude rowdy or drunken individuals.” Whether something as fundamental as citizenship should be treated similarly to the right of an unruly, besotted patron to get one more nightcap is a matter on which people are likely to disagree.

In any case, adopting Epstein’s point of view would require a Supreme Court decision overruling the Afroyim precedent and returning the United States to the system more as it was in the 1950s and 1960s. Trump is likely to have a chance to make some at least one Supreme Court appointment; perhaps this is the America to which his campaign slogan suggested returning.

Manchester by the Sea Is a Stunning Meditation on Grief

Manchester by the Sea begins with a happy memory—Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck) horsing around with his young nephew Patrick on their fishing trawler, as his brother Joe (Kyle Chandler) looks on laughing. But the action unfolds from a distance; the camera hovers far up in the sky, backed with a melancholy choral score. It’s telling of how grim Kenneth Lonergan’s new film is that, even its early, happier recollections of Lee’s life feel haunted.

Manchester by the Sea goes on to be a fantastic meditation on the long tail of trauma, but one that doesn’t wallow needlessly: There’s such humor and humanity at work that the film manages to be cathartic. Rather than focus on the lowest point in Lee’s life—the tragedy that drove him from the film’s titular town and estranged him from his wife Randi (Michelle Williams)—Lonergan moves back through time freely, showing specific moments in Lee’s past, even as he struggles with a new challenge: being a surrogate father to the now-teenaged Patrick after Joe dies.

It’s a simple-seeming setup for a family drama. Lee, who works as a janitor for an apartment complex near Boston and appears to live an emotionally spartan existence, is summoned back to the fishing town of Manchester to take care of Patrick (Lucas Hedges). The shock of Joe’s death is blunted somewhat by the knowledge that he suffered from a congenital heart condition. In flashbacks, viewers see Joe, affably played by Chandler, as the warm lynchpin of his extended family, a steadying figure whose absence feels immediate and profound. Where Joe was reliable and garrulous, Lee is prickly and taciturn, going through the mourning process as though he’s done it before.

As an actor, Affleck is terrific at showing his characters’ inner workings without saying a line—you can always see the gears ticking behind his eyes. In Lee’s case, there’s a darkness he clearly can’t shake, and the simple fact of being back in Manchester seems to be pressing in on him at every moment. Slowly, Lonergan unfolds Lee’s past, in parallel with his present efforts to abide by Joe’s wishes and serve as a guardian to Patrick, eventually revealing the nightmare that drove Lee from his hometown. It’s a sad film, but Manchester by the Sea feels like neither “misery porn” nor some academic exercise in misfortune.

That’s mostly because Lonergan keeps a firm grip on his characters, none of whom feel defined by their pain. Patrick may have just lost his father, but he remains a wise-ass 16-year-old, and his scenes with Lee have a hilarious bristle to them. Hedges is a revelation as Patrick, a willful teenager who’s juggling two girlfriends and is devoted most of all to his terrible rock band. His built-up grief spills out suddenly at random prompts, and vanishes just as quickly, startling Lee, who has gotten used to locking his feelings away.

Together, Affleck and Lonergan have made a drama of rare power.

In Patrick, Lee witnesses the grieving process playing out naturally—there’s an end in sight, even if the loss of Joe is intensely felt. For Lee, the grieving process seems more entrenched, a hard truth that’s compounded by the fact that his ex-wife Randi (Williams, extraordinary in a brief role) has gotten back on her feet with less difficulty than him. It’s best to go in to Manchester by the Sea knowing as little as possible about the Chandler family history, but it’s no spoiler to say that what transpired is horrifying enough that random townspeople in the film say, “So that’s the Lee Chandler” at the mere sight of him.

The vague mystery structure of Lonergan’s screenplay is ingenious: Run chronologically through its pile-up of family horrors, Manchester by the Sea might be too much to take. But by starting with Joe’s death, then softening the blow with flashbacks to his life, Lonergan reels viewers in rather than repelling them with hopelessness. The story of Lee’s forced exile from town becomes something you want to understand, not just another chapter of despair. It also helps that Manchester is ferociously funny throughout, thanks largely to Lee’s terse attempts at parenting Patrick.

At 2 hours and 17 minutes, the film is perhaps a bit overstuffed, meandering into some side-plots in its final act that don’t quite pay off. Lonergan’s last film, the messy 2011 masterpiece Margaret, was sprawling in all the right ways, jumping from vignette to vignette as it explored the mind of a teenager wrestling with her own psychic pain. Manchester by the Sea is a more focused work, one about Lee’s efforts to overcome his past, and his sadness at the comparative ease with which those around him have done so. In the brooding Affleck, Lonergan has found a perfect leading man, and together they’ve made a drama of rare power—a tale of human suffering that succeeds because of its love for its characters, rather than for their misfortunes.

An Updated Company for an Era of Single Women

Before the Broadway premiere of Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s Company in April 1970, American musicals mostly had a single purpose: to bring a man and a woman together in romantic (and melodic) harmony. But Company upended this tradition, offering instead a collection of vignettes featuring marriages in different states of (un)happiness, seen from the perspective of a flaky 35-year-old bachelor named Bobby. Bobby’s ambivalence toward marriage frustrated his friends and shocked early audiences, as did the fact that he ended the show still single. So much so that Company, Rob Kendt wrote in The Los Angeles Times in 2004, “represented a full-scale assault on two venerable institutions, marriage and the musical theater.”

Bobby’s apathy about marriage in 1970 also represented a shift in the national psyche that had been brewing since the end of the Second World War. As women gained power in society and the free-love movement distinguished sexuality from marriage, questioning the institution itself became more commonplace. And as the decades went on, Company, which had once scandalized theatergoers, became less provocative. But the announcement that a new production of the show will reimagine Bobby as a female character makes the almost 50-year-old musical suddenly timely again. Bobbie, a single woman in her mid-thirties who’s reluctant to commit, has the potential to illuminate the benefits and restrictions of modern relationships, just as her male counterpart did half a century ago. Her changing gender also shifts the dynamic of every other relationship in the show, challenging assumptions about power, sexuality, and the nature of marriage in the 21st century.

Gender has long been a flexible construct in theater, from men playing women’s roles in Shakespeare’s time to women in the 21st century playing King Lear and Henry IV. But for Sondheim, notoriously intractable when it comes to productions of his shows, the decision to make Bobby female is entirely unprecedented. He’s reportedly involved in the new production, which will debut in London in 2017 in a staging by the Tony-winning director Marianne Elliott (War Horse, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time). Elliott had been considering adapting the show for a while, she told the Daily Mail, but was put off by its anachronistic nature, until the producer Chris Harper suggested she reimagine Bobby as a woman. “Suddenly, it became much more now,” she said.

Recent revivals of the show have struggled with the fact that it’s so intentionally a study of shifting marital mores in the early 1970s. (“Company, written today, would surely include at least one gay marriage,” The Washington Post’s Peter Marks wrote of a 2013 production.) But as a character, Bobby has been hard to pin down since his inception. This is partly deliberate: Company was created by the playwright and librettist George Furth as a series of one-act plays written as an exercise prescribed by his therapist, each intended to be performed by the actress Kim Stanley. “In each playlet there were two people in a relationship and a third person who often acted as a catalyst,” Sondheim told The Paris Review in 1997. “We realized that what the show should be about is the third person. So we invented the character of Bobby, the outsider in five different marriages.” By his nature, Bobby is nothing more than a cipher—he’s a plot device who offers a window into the marriages of others.

The show begins and ends with Bobby’s 35th birthday celebration; the scenes that happen in between precede his birthday in no particular order, and the question of why Bobby is unmarried seems to shed more light on his friends and their own frustrations than it does on his desires. “Boy! To be in your shoes, what I wouldn’t give!” his male friends sing as a chorus on “Have I Got a Girl for You”:

The freedom to go out and live!

And as for settling down and all that,

Marriage may be where it’s been, but it’s not where it’s at.

The irony of the show is that its most fascinating characters are women, from the bitter, acerbic Joanne (her diatribe against wealthy married women, “Ladies Who Lunch,” is one of Company’s showstoppers) to the manic, neurotic Amy. Bobby’s love interests, though, who pop up to berate him, Greek chorus-style, fit more neatly into stock character archetypes: April, a naive flight attendant; Marta, a hipster; and Kathy, a small-town girl. In the song “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” they opine together that since Bobby flatters and charms them without committing, he must be mentally unstable. “A person that / Titillates a person and leaves her flat / Is crazy, / He's a troubled person, / He’s a truly crazy person himself,” they sing.

The musical’s generalized anxiety, and its recurring emphasis on psychoanalysis, show it to be very much a product of the 1970s. “Through the ’60s there was increasing anxiety about masculinity,” Stacy Wolf, a professor of theater at Princeton University and the author of Keeping Company With Sondheim’s Women, told me. “In some ways Company is about this crisis—what does it mean to be a man? Does a man have to be married? It was very much in the air at the time, and so the show was very edgy and threatening to its audiences, partly because of these issues, but also because it was one of the very first musicals that was set during the period it dealt with.”

In the years since Company premiered, many critics, directors, and fans have deduced that Bobby is gay, and that the unspoken nature of his sexuality is what contributes to his two-dimensionality as a character. Neither Sondheim nor Furth was out of the closet in 1970, but by 1995, when Company was revived, they took pains to write a scene into the updated show that clarified that Bobby is straight. Still, “the question of his sexuality, the ambivalence and the ambiguity, is one of the most interesting things in the musical,” said Wolf. A female Bobbie, updated for audiences who have a more fluid understanding of sexual desire, offers the opportunity to further expand the musical’s ambitions.

In some ways, Sondheim’s female characters are a better fit for this era than they are of the times they were originally written in.

This connection with contemporary theatergoers is what makes the prospect of a female Bobbie so potent. In 2016, as Rebecca Traister documented earlier this year in her book All the Single Ladies, unmarried women have more power and cultural impact than ever before. In 2009, for the first time in recorded history, the percentage of married women in the U.S. dropped below 50 percent. “We are living through the invention of independent female adulthood as a norm, not an aberration,” Traister wrote, “and the creation of an entirely new population: adult women who are no longer economically, socially, sexually, or reproductively dependent on or defined by the men they marry.”

Elliott’s production of Company will have to reckon with this new reality, in a culture that still tends to label unmarried adult women over 35 spinsters, and to define famous adult women who haven’t borne children as personal failures. But in some ways, Sondheim’s female characters are a better fit for this era than they are of the times they were originally written in. From Into the Woods’s Cinderella to Gypsy’s Mama Rose, his women tend to strive for something far beyond motherhood and marriage, even if it leads them to disaster. Sondheim, Laurie Winer wrote in The New York Times in 1989, “imagined in these women a development that goes far deeper than economic independence ... He has depicted a sea-change in their approach to life.”

The specific evolution of female desire that Sondheim’s heroines expressed has now become commonplace. Transforming Bobby, perhaps theater’s most notorious heterosexual (ostensibly) bachelor, into Bobbie, a woman with profound ambivalence toward societal norms regarding marriage and children, offers Company a chance to be what it was in 1970: revolutionary. “The degree to which the production will feel relevant and contemporary will have to do with all of the pieces that go into it,” Wolf says. “There are endless choices in terms of what kind of woman she’ll be.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower