Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 355

September 1, 2015

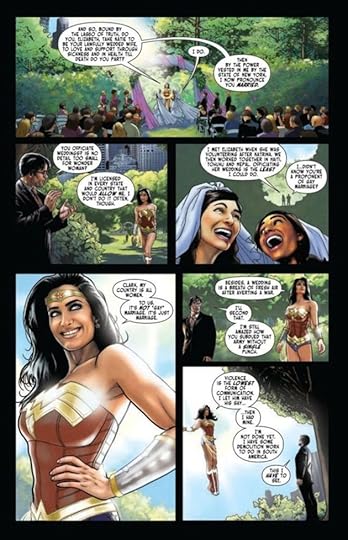

Wonder Woman Endorses Marriage Equality

In the latest Wonder Woman comic (released in digital format on August 20), the feminist icon becomes the first DC hero to officiate a marriage between characters of the same gender.

After performing the ceremony, Wonder Woman schools Clark Kent on his provincial view of marriage. “I … didn’t know you’re a proponent of gay marriage?” Superman stammers. “Clark, my country is all women,” she retorts. “To us, it’s not ‘gay’ marriage, it’s just marriage.”

(Jason Badower / DC Comics)

(Jason Badower / DC Comics) This scene marks an important moment in the world of DC comics. Just two years ago, in 2013, the writers of DC’s Batwoman—the brand’s first openly gay mainstream hero—resigned after DC refused to allow them to show Batwoman’s marriage to the Gotham cop Maggie Sawyer.

More From Quartz Meet the First Pakistani Cartoon on Indian TV: A Burka-Clad Female Superhero Hollywood’s Superhero Movie Binge Explained in Four Charts DC and Marvel Are Waging an Epic War Over Superhero Supremacy in CinemasRegarding Wonder Woman, “I was a little hesitant, but I had two things,” the comic’s Australian author and illustrator Jason Badower says. “My story was pitched after the Supreme Court decision, and the other thing is that my story has Wonder Woman officiating rather than getting married.”

Like Catholic priests, heroes are generally prevented from getting married by their duties. The proverbial ball and chain, Badower explains, is “a death sentence” for a hero’s plotline. For example, if Clark Kent marries Lois Lane (which he did, in 1996), he can’t date or be romantically involved with Wonder Woman. (“It’s not like superheroes to get a divorce,” Badower notes.)

Instead, comic writers have to wait for a reboot of the brand’s universe, something DC does on average every eight years, or create an alternate universe in which the hero is unmarried and is thus free to engage in romantic dalliances. Romance and mystery are central to the hero genre, so taking away the potential for heroes to explore new love affairs leaves writers’ hands tied.

In the case of the Batwoman plot line, DC’s choice to bar the marriage wasn’t based on an ideological position, according to Badower. Rather, it was a business decision that led to some bad PR.

“The people at DC are some of the most open minded, creative, educated people I have ever met,” he said. “You’re dealing with characters that are global icons with an audience. It’s not about what DC wants to do, it’s about what the audience will respond to.”

But a commitment to storytelling doesn’t mean there can’t be—or shouldn’t be—some socio-political overlap. In fact, the very best comics have long found ways to weave current events and issues into their story lines. After all, the Wonder Woman creator William Marston described the character as “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.” And X-Men creator Stan Lee once said, “The whole underlying principle of the X-Men was to try to be an anti-bigotry story.”

Badower’s latest comic aims to hit the same sweet spot as these examples, making a political statement while staying true to Wonder Woman’s storyline and character. (Wonder Woman is a princess of the Amazons, and, as such, is tasked with performing marriages between members of the all-female tribe.)

“My audience is intelligent people looking for examples of how to behave in this new society. And because it’s in her character, I got a great response,” he says.

The King of Couture

September 1 marks the 300th anniversary of the death of King Louis XIV, France’s longest-reigning monarch. Logging 72 years on the throne, Louis eclipsed Queen Victoria by a decade. But this tercentenary also commemorates a beginning: the birth of haute couture as people know it today, seasonal, corporate, media-driven, and—above all—French.

Related Story

When Louis came to the throne in 1643, the fashion capital of the world wasn’t Paris, but Madrid. Taste tends to follow power, and for the past two centuries or so Spain had been enjoying its Golden Age, amassing a vast global empire that fueled a booming domestic economy. Spanish style was tight and rigid—both physically and figuratively—and predominantly black. Not only was black considered to be sober and dignified by the staunchly Catholic Habsburg monarchy, but high-quality black dye was extremely expensive, and the Spanish flaunted their wealth by using as much of it as possible. They advertised their imperial ambitions, as well, for Spain imported logwood—a key dyestuff—from its colonies in modern-day Mexico. While Spain’s explorers and armies conquered the New World, her fashions conquered the old one, and Spanish style was adopted at courts throughout Europe.

Just as French aristocrats imported their fashions from Spain, they bought their tapestries in Brussels, their lace and mirrors in Venice, and their silk in Milan. They didn’t have much choice; France simply wasn’t producing luxury goods of a comparable quality, and it didn’t have the political, economic, or cultural clout to dictate fashions to other countries.

Louis XIV set out to change that, and, over the course of his long reign, he succeeded brilliantly. Luxury was Louis’s New Deal: The furniture, textile, clothing, and jewelry industries he established not only provided jobs for his subjects, but made France the world’s leader in taste and technology. His shrewd finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, famously said that “fashions were to France what the mines of Peru were to Spain”—in other words, the source of an extremely lucrative domestic and export commodity. Louis’s reign saw about one-third of Parisian wage earners gain employment in the clothing and textile trades; Colbert organized these workers into highly specialized and strictly regulated professional guilds, ensuring quality control and helping them compete against foreign imports while effectively preventing them from competing with each other. Nothing that could be made in France was allowed to be imported; Louis once ordered his own son to burn his coat because it was made of foreign cloth. It was an unbeatable economic stimulus plan.

As he waged a never-ending series of expensive wars across Europe, the French luxury goods industry replenished his war chest and enhanced the king’s reputation at home and abroad. Louis transformed Versailles—a dilapidated royal hunting lodge buried in the countryside 12 miles from Paris—into a showplace for the best of French culture and industry; not just fashion but art, music, theater, landscape gardening, and cuisine. A strict code of court dress and etiquette ensured a steady market for French-made clothing and jewelry. Louis has been accused of trying to control his nobles by forcing them to bankrupt themselves on French fashions, but, in fact, he often underwrote these expenses, believing that luxury was necessary not only to the economic health of the country but to the prestige and very survival of the monarchy. France soon became the dominant political and economic power in Europe, and French fashion began to eclipse Spanish fashion from Italy to the Netherlands. French was the new black.

The king and Colbert employed the full range of available media in service of their fashion propaganda campaign. As the art historian Maxime Préaud writes in the catalogue to the current Getty Research Institute exhibition A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, “from the very beginning of Louis’s reign, he ... recognized that images had the power to shape perception.” Louis subsidized the production of fashion plates by major French artists and engravers in order to promote French luxury goods and culture, both at home and abroad. Rather than being purely descriptive and informative, the captions of these plates—aimed at an affluent and sophisticated international audience—are arch and amusing, laced with sarcasm and sexual innuendo. Many give the figures elaborate backstories and interior monologues wholly unsupported by the innocuous images, while letting the clothes speak for themselves. They set the tone for countless fashion plates that followed, and such verbiage can still be found today in Vogue, Elle, and Marie Claire (to name three English-language publications that owe more than just their titles to France).

Louis believed luxury was necessary not only to the economic health of the country, but to the prestige and very survival of the monarchy.The king himself was the ultimate arbiter of style. A theater buff, Louis took his self-selected sobriquet “the Sun King” from his youthful performances as Apollo in lavish court ballets, and his love of dramatic artifice and splendor infused his offstage wardrobe. The fashions he introduced were colorful, voluminous, and ornamental, the antithesis of austere Spanish style. His idealized likeness appeared in fashion plates and his fashion choices were breathlessly reported in fashion magazines. With his distinctive mane of curls and signature high, red-heeled shoes, Louis combined the incontestable authority of an Anna Wintour with the charisma of a supermodel.

One of Colbert’s most effective and far-reaching innovations was to mandate that new textiles appeared seasonally, twice a year, encouraging people to buy more of them, on a predictable schedule. Fashion prints were often labelled hiver or été for winter or summer, with corresponding props like parasols, face masks, and fans for summer; for winter, there were furs, capes, and muffs for men and women alike. Lightweight silks were reserved for summer; velvet and satin for winter. Due to the changeable French climate, there had always been a certain seasonal rhythm to the textile trade, but now it became formalized and inescapable. Regardless of the weather, the summer fashion season began promptly on Pentecost (the seventh Sunday after Easter; that is, mid- to late-May), with winter clothes donned on November 1, All Saint’s Day. Woe betide the woman who showed up at court in a summer gown on November 2. Other countries took note of the happy economic results of this planned obsolescence and began to impose similar seasonal schedules on their own weavers.

Fashions, too, changed seasonally in France. Whereas Spain had taken pride in the continuity of its fashions—a sartorial stability artificially enforced by sumptuary laws, which restricted certain garments and textiles to specific social classes—the French found this stagnation baffling. Not only was the fashion industry enriched by the constant updating of wardrobes, but the French tended to get bored if a trend lasted too long. As the economist Jacques de Savary observed in his 1675 treatise Le Parfait Negociant, “the French are naturally changeable”; fashion as we know it today is a reflection of the national character, conveniently aligned with the king’s economic goals.

The lavish standard of living and the intricate program of etiquette the Sun King introduced continued to define the French monarchy right up until the French Revolution of 1789. Louis’s name remains synonymous with the ancien regime or old regime the Revolution dismantled: political absolutism, unparalleled luxury, military glory, and grand artistic and architectural schemes. But while many of his innovations and reforms didn’t survive the Revolution, the high-end fashion and textile industry Louis founded is still going strong, bringing fame and fortune to France.

In the highly regimented and specialized haute couture industry, artificial flowers, embroidery, tapestries, buttons, and even fans continue to be handmade using the traditional skills and techniques passed down from the 17th century. More importantly, Louis’s legacy is evident in modern France’s attitude toward fashion; it isn’t a frivolous or trivial industry but an utterly serious one, inseparable from the country’s economic health and national identity. As Susan Sontag once observed, “The French have never shared the Anglo-American conviction that makes the fashionable the opposite of the serious.”

Is There an Audience for Electronic Dance Music Movies?

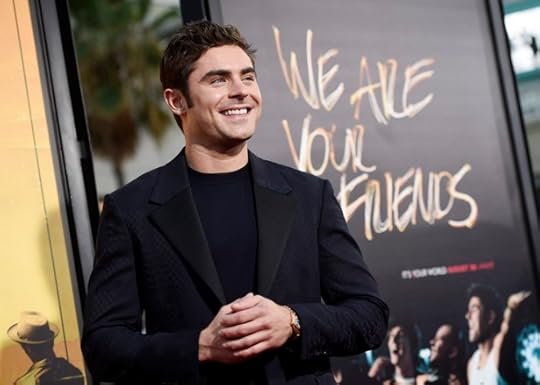

Many of the young festival-goers who’ve helped make electronic dance music into a $6.9 billion industry, presumably, have some fondness for Zac Efron. The actor starred in the smash franchise High School Musical at the exact same time many of them were of the right age to be watching the Disney Channel.

But We Are Your Friends, a movie combining EDM and Efron, has failed spectacularly. Its $1.8 million haul over the weekend means, according to EW, it had the third worst wide-release opening since 1980.

I wrote about the film last week, noting how it portrayed an ambitious DJ in much the same way pop culture likes to portray visionary rockers and other artists. I said the film is “surprisingly watchable,” but I didn’t really get into why: the dead-on depiction of suburban Southern California malaise, the appealing performances, and the pulse-quickening soundtrack. The worst thing you can say about the movie is that it’s too slick, shot like a credit-card commercial targeting the Coachella crowd.

On Twitter, the music critic Philip Sherburne asked his followers for thoughts on why the film tanked, saying that “a bad opening weekend doesn’t reflect on the quality of the film so much as whether there’s even an audience for it.” Some of the theories that resulted say that most EDM fans ...

… enjoy their music as a weekend activity, not an identity marker (the cultural influence by the genre is too total for this to feel true to me). … were too busy raving to get to the theater (haha). … are part of a generation that has “a sense for when its homegrown culture is being co-opted” and the movie “was interpreted as cynical and condescending by many in the EDM community” (definitely true to some extent, judging by the YouTube comments on WAYF’s trailers).At Esquire, Matt Patches suggests that the not-so-cinematic nature of DJ performances—wubba-wubba bass is better felt than watched—contributed, too. But the most fascinating reading of the film’s failure comes from Jia Tolentino at The Awl. Like many critics, she points out that the movie’s big Hollywood backing and Ken Doll-like star keeps it from feeling fully authentic, but she also picks up on an element of it that I sensed but never quite put a name to. “It’s dark,” she writes:

The movie’s structured like a comedy, but no one is having fun. They are in constant pursuit of fun, but they can’t get on top of it, or recognize it, or are too drugged out to remember. The only moment of tangible good emotion comes directly from festival molly; otherwise, everyone’s too nervous, too sure that there’s something better, always on their way up or down. They’re choked with entitlement and dissatisfaction, the L.A. signature that defines [protagonist] Cole Carter’s posse: four demanding, lazy hustlers always gunning for a break. Distinctly white in the tenor of their aggression, these guys know it’s gonna be better; they’re gonna be famous; if you say otherwise, they’ll knock you out.

She compares the film with her own experiences as a dance-music consumer, talking about how the joys provided by the music are also, at some point, “ordinary, or something even grosser.” To its credit, We Are Your Friends comes close to nailing this. The movie’s “crucial ambivalence,” Tolentino writes, “is painted over by the scene’s real-life participants to a degree that will prevent many of them from enjoying the movie.”

August 31, 2015

What the Arrest of Two Journalists Tells Us About Turkey—and Vice

Under Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s presidency, Turkish journalists have increasingly been badgered, intimidated, threatened, and punished. Now, however, the Turkish government is going after two foreign journalists.

Britons Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury, working for Vice News, were originally detained in southeast Turkey, along with a translator and a driver, for not having proper identification. But now they’re being accused of “engaging in terror activity” and having connections to ISIS.

It’s not difficult to see why the Turkish government might not want journalists in the area. Kurdish fighters, some backed by the U.S., have been battling ISIS in Iraq for months. While Turkey opposes ISIS, it’s also terrified of emboldened Kurds pushing for an autonomous state in the region. For decades, Ankara has fought a protracted war against Kurdish guerrilla groups in southeastern Turkey. After long trying to avoid being drawn into the conflict against ISIS, Turkey, a U.S. ally, has begun to take action, but it’s fighting against both ISIS and the Kurds, a strange case where, for the Turkish government, the enemy of my enemy might still be my enemy.

And now it seems like the Vice reporters have been caught in the center of it. So far, there appears to be no hard evidence on offer connecting them to ISIS. They have denied any connection, and Vice released a statement labeling the accusations as “baseless and alarmingly false charges.” Based on what’s known right now, the Turkish arrest seem foolish and paranoid at best, and like a dangerous intrusion on journalism at worst.

It is also an example of how Vice has changed over the years. In a famous moment in the documentary Page One, about the media desk at The New York Times, the late great David Carr dresses down a team of Vice journalists who he thinks have demeaned his paper’s reporting. “Before you ever went there, we’ve had reporters there reporting on genocide after genocide. Just because you put on a fuckin’ safari helmet and looked at some poop doesn't give you the right to insult what we do,” Carr rasps. The Vice team, chastened, apologizes.

Carr was right—then. But Vice’s coverage of ISIS has demonstrated that whatever other charges may be levied at Vice, it is taking foreign coverage more seriously these days. Yes, there’s sometimes an exaggerated, performative bad-assery to Vice productions, but their reporting from the Middle East has been essential. Most notably, in 2014, Vice released a five-part documentary series from the ISIS capital, Raqqa, an unprecedented look into the terror group’s heartland. The series won a Peabody Award.

But any Americans who might look at the Turkish arrests with a certain smugness about U.S. protections for the press might be well-advised to tread carefully. In a post for The Atlantic in October, Andrew F. March, a political scientist at Yale, warned that American law was written so broadly that Vice could be prosecuted for giving aid to terrorists with the documentary:

That decision means, for example, that Jimmy Carter and his Carter Center could be in violation of federal law for giving peacemaking advice to groups on the State Department’s FTO list. Any private individual who coordinates with a group on that list, or a group that the individual ought to know engages in terrorism, with the purposes of providing it advice or assistance—even on how to pursue an end to its campaign of violence—is guilty of a crime by the logic of the Roberts Court.

As March acknowledged at the time, it was unlikely that Vice’s journalists would be prosecuted. But of course, that’s not much protection: The question is whether or not they could be. Journalism should not be a crime, whether that’s in Tehran, Turkey, or Tennessee.

How Wes Craven Redefined Horror

To see a Wes Craven film was, above all, to have your expectations met and subverted. The director, who died yesterday at 76, worked primarily in horror—a genre steeped in formula, where any film that makes the slightest progress is imitated for years after. Throughout his career, Craven was the one engineering that kind of progress, pushing against the bounds of taste and predictability, never letting his work settle into a groove, and repeatedly setting new benchmarks for imitators to strive for, decade after decade.

Craven died in Los Angeles after a battle with brain cancer, and his last work as director was the somewhat disappointing Scream 4, a quasi-reboot of the horror trilogy that had given his career new life in the late 1990s. He was primed for another reinvention, and if it weren’t for his advancing age, Craven would no doubt have pulled it off as he had so many times before, producing horror films with one foot in his influences and one foot in the future. Other masters of the genre might have been more visually inventive (Dario Argento), or more focused on harnessing tension (John Carpenter), or real-world commentary (George Romero), but Craven tried it all. Unafraid to experiment with tone, he was impossible to pigeonhole even at the end of his career.

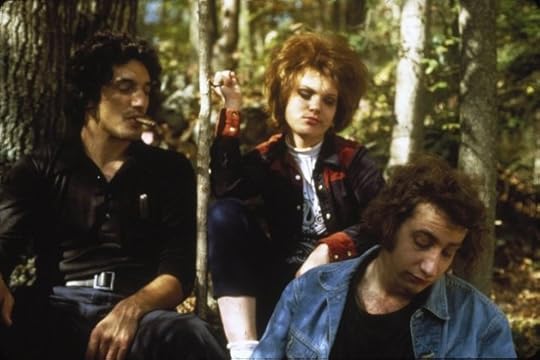

The revolutionary luridness of Craven’s early work may have owed a debt to his beginnings in the adult-film industry. Raised in a strict Baptist household, Craven briefly worked as a professor before developing interest in film, working as a sound editor, then a writer and editor for pornographic films (under various pseudonyms). He scraped together $90,000 to make The Last House on the Left, which was originally planned as a “hardcore” film before being upgraded to a slightly less graphic B-movie. Its inspiration was the 1960 Ingmar Bergman drama The Virgin Spring, about a medieval man’s crisis of faith over the revenge he exacts when confronted with the criminals who raped and killed his daughter.

Last House on the Left / MGM

Last House on the Left / MGM The Last House on the Left, 43 years on, remains a uniquely unsettling viewing experience, partly because of its amateurish tinge. The acting is largely stilted and the score is downright perplexing, lurching from atonal synth noises to calm country ballads over distressing scenes of violence and murder. The film was so shocking that it became a word-of-mouth success based on tales of people passing out in the theater. Advertised with the famous catchphrase “To avoid fainting, keep repeating, ‘It’s only a movie, only a movie,’” it was a landmark work of exploitation cinema, a disturbing reflection of the senseless violence (particularly the Manson Family murders) that had capped the previous decade.

His 1977 follow-up, The Hills Have Eyes, had a similarly brutal quality and a simple premise. A family is targeted by random murderers, but rather than the aimless hippies of The Last House on the Left, these new villains are savage, inbred mountain folk, the most memorable of whom is a giant, bald cannibal named Pluto (Michael Berryman). His terrifying visage became the film’s most enduring image, making him the first of many Craven villains whose faces became immortal in popular culture (along with Freddy Krueger’s burned skin and the Edvard Munch-inspired Scream mask).

Craven struggled to transition from these brutal early works to more mainstream commercial success. At the time, low-budget horror cinema was gaining legitimacy following the 1978 release of John Carpenter’s Halloween, which is credited for inventing the “slasher movie.” After a few failed efforts, Craven finally found his foothold in 1984 when he wrote and directed A Nightmare on Elm Street: a strangely funny, deliberately surreal take on the slasher model about a dead criminal who murders people in their dreams.

A Nightmare on Elm Street / New Line Cinema

A Nightmare on Elm Street / New Line Cinema Besides casting a young Johnny Depp in his breakout role, Elm Street’s legacy includes a lasting franchise of sequels that range from paint-by-numbers to the weirdly memorable. But alone, it stands as Craven’s best work. Its heroes are teenagers roiled by hormones and normal anxieties, its death scenes are radically bloody and strange, and the nightmare sequences are orchestrated with clever filming tricks. Made for less than $2 million, the film was a box-office sensation, and one Craven again struggled to equal for years.

His work in the intervening years ranges from the terrible (The Hills Have Eyes Part II, a sequel he later disowned) to the formulaic (the zombie flick The Serpent and the Rainbow) to the fascinating (The People Under the Stairs, a smart but disturbing commentary on Los Angeles’s slums in the early ‘90s), but it wasn’t until the 1994 release of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare that he entered the final stage of his career. New Nightmare saw Freddy Krueger invade the set of Craven’s latest movie, and served as a self-reflexive look at the horror film industry and its penchant for cannibalizing what has come before, be it through sequels, remakes, or simple rip-offs.

This led Craven to Kevin Williamson’s Scream script, in which teenage serial killers murder people in accordance with the laws and tropes set down by the very slasher movies Craven and his ilk had created years earlier. Funny and self-referential, but still filled with gore, good old-fashioned jump scares, and playful suspense, it made $103 million at the domestic box office, an unheard-of bonanza for an R-rated horror film, and spawned a thousand imitators that were half as scary and one-tenth as intelligent. The perfect person to satirize Craven’s work was Craven himself, and though its three sequels (all directed by Craven) weren’t as compelling, they never dropped the meta-textual angle (like New Nightmare, Scream 3 saw a killer stalking a horror movie set).

Scream / Dimension Films

Scream / Dimension Films Outside of Scream, Craven’s later horror output was less interesting. The long-delayed horror-comedy Cursed, also written by Williamson, flopped in 2005, and 2010’s My Soul to Take was dismissed by audiences and critics. His most unconventional choice was the sweet-but-sappy inspirational music-teacher drama Music of the Heart (1999), which netted an Oscar nomination for Meryl Streep but mostly drew confused shrugs from critics, who were shocked that Craven would make such a formulaic movie. Though Craven wasn’t particularly known for his action chops, the 2005 drama Red Eye, starring Cillian Murphy and Rachel McAdams, featured some high-wire antics on an airplane (though its best moments came in the suspenseful opening scenes).

Even with all those career bumps, the announcement of a new film from Craven was always weighted with expectation—that perhaps this would be the latest project to reshape how moviegoers thought about horror, long one of cinema’s least heralded genres. The form owes its critical legitimacy and studio respectability to Craven and his unwillingness to churn out something derivative, even if that’s what was expected of him. Most horror directors are defined by the field they work in, but for Craven, it was the other way around.

Why Doesn’t Serena Williams Have More Sponsorship Deals?

The U.S. Open begins today (August 31), and Serena Williams has a chance to make tennis history. A win would put her at 22 career Grand Slam titles, tying Steffi Graf for second most, behind only Margaret Court. Her astonishing ability prompts arguments that she’s the sport’s greatest female player of all time, and currently the most dominant U.S. athlete in any sex or sport. Katrina Adams, the president of the U.S. Tennis Association, recently posited that Williams is the greatest athlete ever—period.

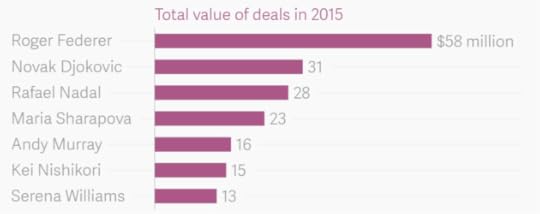

More From Quartz Serena Williams Is Way Better Than Maria Sharapova—Why Do We Keep Calling Them Rivals? Tennis Is the Latest Sport to Chase Money Around the World Americans Should Care Much More About Women’s Soccer Than Men’s. Here’s Why We Don’t.Not everyone will agree on each of those points, particularly the last one, but there’s no disputing that Williams has been among the top handful of athletes on the planet for years now. Yet, on Forbes’s list of the highest-paid athletes, Williams ranks 47th. And of the seven tennis players on the list, she ranks last in endorsement dollars, making $13 million annually.

The top-earning male player, Roger Federer, will bring in an estimated $58 million in endorsements this year. The number-four ranked men’s player, Kei Nishikori, also brings in more than Williams, as does Maria Sharapova, who will out-earn her by $10 million despite not having been a genuine rival to Williams for years. The only logical explanation for this gap points to long-held prejudices regarding female sports stars and how people feel they should look.

Endorsement Deals for the World’s Highest-Paid Tennis Players

Quartz

Quartz You might be tempted to explain away the immense gap between Williams and Federer by saying Federer has been far more dominant in his sport. But he hasn’t. Federer has 17 Grand Slam titles. Williams has 21. Federer has spent a record 302 weeks ranked at number one. Williams just passed 250, and she’ll likely eclipse Federer’s tally before too long. Williams also has a better win-loss ratio. Over his career, Federer has 1,041 wins and 234 losses, or about 4.4 wins per loss. Williams currently has 732 wins and 122 losses, or 6 wins per loss.

In fact, if Williams clinches a U.S. Open victory, she’ll become just the sixth person in history, male or female, to win all four major tournaments—Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and U.S. Open—in a single year, a feat tennis hasn’t seen since Graf did it in 1988.

Mick Tsikas / Reuters

Mick Tsikas / Reuters It also doesn’t explain why the other men’s tennis stars earn more. One might claim men’s tennis has more viewers, so sponsors are willing to pay men more. But the gap between the top men and Williams is too large for that explanation to hold up. In fact, the women’s finals of the U.S. Open have had higher television ratings than the men’s finals the last two years, and this year, fans were so excited at the prospect of watching Williams rewrite tennis history that the women’s final of the U.S. Open sold out before the men’s for the first time ever. Williams is expected to be a huge ratings draw at the U.S. Open, and it was largely due to excitement over her and her sister Venus that in 2001 the U.S. Open women’s final was first broadcast in prime-time.

Experts have said that male athletes are more marketable because they help advertisers reach the coveted 16-to-30-year-old-male demographic, but that implies women aren’t worth marketing to even though sportswear brands know that convincing women to buy their products is crucial. Women control $29 trillion in buying power globally and make 64 percent of household buying decisions. Skechers, in part by marketing to women, has become the number two sneaker brand in the U.S., and Nike thinks that by targeting women it can add $2 billion in annual sales by 2017.

Actually, Nike is one sponsor that has long supported Williams. In her honor, it just released the “Greatness Collection,” which Williams helped design and which she’ll be wearing at the U.S. Open. She also has her own signature sneaker, though it From the “Greatness Collection” (Nike)

It’s not news that female athletes don’t earn as much as male athletes in endorsements—even in tennis, which is otherwise the most equitable sport. But another woman, Maria Sharapova, also earns significantly more, and it’s likely because she’s willowy, white, and blonde, while Williams is a black woman with prominent, athletic muscles—as is often pointed out, sometimes disparagingly.

This claim, it’s worth noting, isn’t particularly controversial. A New Yorker article commented on the reason sports fans don’t love Williams as they should. “Part of this is owing to the dueling isms of American prejudice, sexism, and racism, which manifest every time viewers, mostly men, are moved to remark on Williams’s body in a way that reveals what might most charitably be called discomfort.”

The suggestion is that female athletes are marketable only insofar as they look a certain way.In June, Forbes looked at the reasons why Sharapova is set to earn more in endorsements than Williams this year. “Does ethnicity and ‘corporate bias’ play a partial role in explaining the endorsement gap?” the article asked. “In all likelihood, yes.”

Williams, who has faced outright racism and sexism on multiple occasions, is aware of the factors at play. “If they want to market someone who is white and blond, that’s their choice,” she recently told The New York Times Magazine. “I have a lot of partners who are very happy to work with me.”

As the story pointed out, Eugenie Bouchard, an up-and-comer in women’s tennis currently ranked number 24, topped a different list of the most marketable athletes. Like Sharapova, she’s white, blonde, and thin. The suggestion is that female athletes are marketable—which is to say that the public can connect with them, and be persuaded to buy things by them—only insofar as they look a certain way.

There’s no doubt that Williams has been controversial at times, that she’s already paid well, and will likely be paid better still still if she wins the U.S. Open. But there’s also no doubt that she’s one of the greatest athletes of her generation, that she’s one of the most exciting to watch, that she has the ability to draw crowds, and that she would be paid far more if she were someone other than who she is.

She’s a dream athlete for sponsors. It’s a shame, in the most literal sense, that they don’t adequately recognize it.

Alaska's Great White Mountain

There are many disorienting things about traveling to Alaska in the summer; the long daylight hours are only the most obvious. But during a vacation to the land of the midnight sun, I also found myself perplexed: Why did people keep pointing at Mount McKinley and calling it “Denali”? Wasn’t that just the name of the national park where it was located?

As of today, the name of the mountain and of the park will be the same. For all the ruckus aroused by President Obama’s decision to rename the nation’s tallest peak, the name change may mean the least for Alaskans, the people who most frequently discuss it. The greatest outcry against the name change,

How Katrina Sparked Reform in a Troubled Police Department

The New Orleans Police Department had a reputation for corruption long before Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the summer of 2005. For decades, the department was infected by a culture of discrimination, abuse, and lawlessness. That culture spilled out into the open in the week after the storm. During that brief period, police officers shot and killed three unarmed civilians.

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New Orleans

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New OrleansRead More

As Katrina’s flood water receded, the department's dysfunction was laid bare for all to see. A Justice Department investigation found that the police department was loosely held together by an even looser code of conduct. Soon after, the city was forced into an agreement to reform its police department. It seemed a uniquely awful situation.

In the years since Katrina, though, the Justice Department has launched investigations into numerous other police departments. The dysfunction of the New Orleans police began to look less like an exception, and more like an example of widespread issues that happened to be noticed and addressed earlier in New Orleans than elsewhere. Ironically, the depth of the department’s dysfunction has set it up to be a model for reform. As it continues to improve almost every area of its operation, it is becoming an example for other troubled police forces seeking to clean up their own acts.

The New Orleans Police Department’s Long, Troubled History

“New Orleans was a city where the general population had a fair degree of skepticism coupled with outright fear of the police department. It was quite justified,” says Pam Metzger, a New Orleans resident and a professor of criminal law at Tulane University Law School. “That made this a place where one’s view of the police depended largely on one’s race and socioeconomic background.”

The department earned that reputation through a series of high-profile incidents of police violence against black suspects and the city’s black community at large. In 1980, officers went on a rampage through the largely black Algiers section of the city that ended in the deaths of four civilians and left nearly 50 others injured. The 90s were full of shocking news stories about the NOPD’s abuse, misconduct, and criminal activity. Perhaps the most outrageous example came in 1994 when a woman was killed at the behest of an NOPD police officer after she reported that he’d beaten up a teenager in her neighborhood. The hit was recorded in the process of a federal investigation into a cocaine ring involving that officer.

In 1996, The New York Times described the New Orleans police as “a loose confederation of gangsters terrorizing sections of the city.”

Katrina Blew the Lid off the NOPD

When Katrina struck on August 29, 2005, the department found itself understaffed and overwhelmed. Many of its officers evacuated the city before the storm hit and couldn’t come back to help secure the city. Police were without power, vehicles were under water, stations were flooded along with 80 percent of the city, and the police radio system had completely shut down.

Despite the force’s reputation and the tremendous odds officer faced, many rose to the occasion. Michael Harrison, the current superintendent of the NOPD, says officers coordinated and performed search-and-rescue operations for days, many working around the clock. During this time, however, rumors of widespread violence and looting spread throughout the force. While officers scrambled to save stranded residents, there was a growing sentiment that the city was being overrun by its criminal element.

“I heard stories and I heard rumors but I didn’t see it and I never talked to anybody else who saw it,” says Harrison, who was a commander in the department during Katrina.

In the week after Katrina hit New Orleans, police officers shot at least 10 civilians, killing three.“Yes, we saw people looting stores that didn’t flood for supplies and clothes. We saw people taking it upon themselves to get whatever necessities they needed; people were in survival mode,” he says.

Somewhere in all of the chaos, ProPublica later reported, officers were told they had the authority to shoot looters.

“It's not clear how broadly the order was communicated. Some officers who heard it say they refused to carry it out. Others say they understood it as a fundamental change in the standards on deadly force, which allow police to fire only to protect themselves or others from what appears to be an imminent physical threat,” reported A.C. Thompson.

In the week after Katrina hit New Orleans, police officers shot at least 10 civilians, killing three.

Police Shootings the Weeks After Katrina

Suspected of committing robbery days after the storm, Keenon McCann was shot by police and arrested but released on his own recognizance and never charged with a crime. Matthew McDonald was shot in the back and killed by officers after allegedly threatening them with a gun. Police shot and killed Danny Brumfield, Sr. outside of the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center. The officers involved say they thought they saw something shiny in one of Brumfield’s hands as he, according to witness accounts, attempted to wave them down for help.

Perhaps the most infamous of the post-Katrina police shootings, however, was the incident on Danziger Bridge in which officers, having heard that police were being shot at near the bridge, drove to the scene and opened fire. Six civilians were shot. Seventeen-year-old James Brissette and Ronald Madison, a 40-year-old mentally handicapped man, were killed. A federal investigation into the incident found that none of the people shot on the bridge were armed.

One case that didn’t get much national attention, however, was just as appalling. On September 2, Henry Glover was shot in the chest in a strip mall parking lot while reportedly picking up stolen goods. Glover’s brother hailed a good Samaritan to drive them to a hospital after the shooting, but the driver took them to a makeshift police station where they expected to get medical attention for Glover, who was still alive by some accounts. Instead, the men say they were handcuffed by officers and severely beaten. The vehicle used to transport Glover was then driven away by officers with Glover still in it. Days later, the car was discovered by private security consultants completely burned out with Glover’s charred remains inside. It was later uncovered that the person who initially shot Glover in the parking lot was an NOPD officer.

While Harrison says he can’t get into specifics of the investigations, he can confirm that Glover was shot by a police officer and another officer did burn his remains.Chief Harrison was with the public-integrity bureau during the use-of-force incidents that followed Katrina. A New Orleans native, he joined the force in 1991 at the height of the crack-cocaine epidemic, and of the department’s dysfunction. Good police work on the street led to a job in the Narcotics unit where he often worked undercover and, on a few occasions, ensnared corrupt cops who were involved in the city’s drug trade. In 2000, Harrison was recruited into the department’s public-integrity bureau, where he was tasked with fighting corruption on the force and ensuring accountability. He was involved with some of the post-Katrina investigations, in particular the death of Henry Glover. While Harrison says he can’t get into specifics of the investigations, he can confirm that Glover was shot by a police officer and another officer did burn his remains.

The Department of Justice Steps In

If it wasn’t clear before the storm, the behavior of police officers in the days after revealed how troubled the department really was. In May 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice announced an investigation into the New Orleans Police Department.

After a year of community meetings, interviews with officers, and a review of police documents, the Justice Department issued a 158-page report on the state of the department. Expert say it is one of the most comprehensive reports the agency has ever released after a police-department investigation. Investigators concluded that the NOPD had a pattern and practice of unconstitutional conduct and violation of federal law in several areas, including: use of excessive force; unconstitutional stops, searches, and arrests; racial and ethnic profiling; LGBT discrimination; failure to investigate sexual assaults and domestic violence; and failure to provide effective policing services to persons with limited English proficiency. The Justice Department also determined that broken systems for evaluation, inadequate training and supervision, ineffective systems for accountability, and a lack of sufficient community oversight all contributed to the department’s lawlessness. In short, just about every area of the department was broken.

Related Story

Justice Department officials said their probe was completely unrelated to any of the Katrina-related cases, but Metzger and Harrison agree that incidents of police misconduct following the storm shone a light on a culture that really needed to be changed and exposed the department’s flaws to a national audience.

In January 2013, after years of negotiations, the Department of Justice and the City of New Orleans entered into a consent decree to reform the police force. The agreement required that the department make sweeping changes to the way officers use force and conduct stops, and searches and interrogations. It also required it to revamp its recruitment, training, supervision, evaluation, and investigation practices in addition to its paid details, which the report called the “aorta of corruption” in the department. Finally, the consent decree mandated more transparency and greater civilian oversight of the department.

A Department on the Road to Reform

Recent reports issued both by the independent Consent Decree Monitor and the police tell the story of a department working to put systems in place that will make it more efficient, transparent, accountable, and just. In keeping with the consent decree, the department is tasked with an overhaul of most of its practices and procedures. Arguably the most progress has been made in the department’s transparency. Chief Harrison says that increased transparency from the police is essential to establishing trust with residents while his department continues to reform. For its efforts, the department was recognized this year by The Sunlight Foundation.

Two of the biggest reforms in the years since Katrina, though, didn’t actually come as the result of the consent decree. In 2009, the city created the Office of the Independent Police Monitor, a civilian oversight agency. The department worked with the Monitor to create a protocol and process for sharing information, one of only a few such systems in the country. In addition, last year it became the first police department in the country to outfit its entire police force with body cameras. The body camera program has been criticized for its accountability loopholes, but many agree that it’s an important addition to the department’s reforms.

“All of the things in the consent decree can ultimately only be maintained if there’s a robust accountability and oversight system in place.”“All of it working at the same time is turning us now into a model police department,” Harrison says. “We were slow moving getting started but we're feeling traction and momentum now going forward.”

He adds that crime has come down in recent years and the department has become more efficient because of the consent-decree requirements around documentation and transparency.

“The progress is incremental. It’s here and there,” says the Independent Police Monitor, Susan Hutson. “Keeping in mind all of the shootings that occurred during Katrina, use of force is always our number one focus and we’ve put a lot of energy into monitoring cases and how they’re investigated,” she adds. “We’ve been watching [the department] grow for the past few years and they’re doing a much better job.”

Despite the progress made by the department, the police shootings that followed Katrina still cast a pall 10 years later. Charges were never filed against officers in the McCann or McDonald cases. The officers involved in the killing of Brumfield were both charged with crimes for lying about what happened that night, but not charged with murder. One was convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice. Officers involved in the killing of Glover and subsequent cover up were found guilty at trial, but an appeals court later vacated those convictions. The incident at Danziger Bridge spawned a series of charges, convictions, trials, and reversals. Ten years later, five officers are currently in prison for their role in the shooting and cover up. After convictions and mistrials, six others await their day in court.

Indeed, the New Orleans Police Department still has much more work ahead if they hope to turn around the department for good and win the trust of residents. With just two years of the consent decree under its belt, Hutson says there’s still a need for basic, fundamental changes.

“All of the things in the consent decree can ultimately only be maintained if there’s a robust accountability and oversight system in place after the consent decree is gone,” she says. “If not, we’re back where we started.” And among the many lessons that the department has to offer other police forces around the country, that may be the most important of all.

This project was made possible with support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Nicki Minaj, Miley Cyrus, and the VMAs: A Tone-Policing Palooza

Nicki Minaj didn’t, in the end, say much to Miley Cyrus at all. If you only read the comments that lit up the Internet at last night’s MTV Video Music Awards, you might think she was kidding, or got cut off, when she “called out” the former Disney star who was hosting: “And now, back to this bitch that had a lot to say about me the other day in the press. Miley, what’s good?”

Related Story

Drake, Taylor Swift, and the Triumph of the Fake

But to really understand the moment, you need to watch the tape.

To summarize: When Minaj’s “Anaconda” won the award for Best Hip-Hop Video, she took to the stage in a slow shuffle, shook her booty with presenter Rebel Wilson, and then gave an acceptance speech in which she switched vocal personas as amusingly as she does in her best raps—street-preacher-like when telling women “don’t you be out here depending on these little snotty-nosed boys”; sweetness and light when thanking her fans and pastor. Then a wave of nausea seemed to come over her, and she turned her gaze toward Cyrus. To me, the look on her face, not the words that she said, was the news of the night:

It’s fitting that the moment was more about delivery more than content. After all, the entire battle had turned into one about manners. In July, Minaj had sent out tweets implying that her work hadn’t been nominated for Video of the Year because, unlike favorites such as Taylor Swift, she wasn’t white and skinny. For an article published days before the VMAs, The New York Times’ Joe Coscarelli asked Cyrus for a reaction. “If you do things with an open heart and you come at things with love, you would be heard and I would respect your statement,” Cyrus said about Minaj’s tweets. “But I don’t respect your statement because of the anger that came with it … What I read sounded very Nicki Minaj, which, if you know Nicki Minaj is not too kind. It’s not very polite.”

This was a textbook example of what’s come to be known as “tone policing,” a common term in feminist and anti-racist circles—shifting the focus from what was said to how it was said, using the pretext of concern that someone’s style might undermine substance to, well, undermine that substance. It’s also an example of an opinion that appears informed in part by stereotype (BET: “Miley Cyrus Basically Calls Nicki Minaj an Angry Black Woman”) or maybe some un-publicized bad blood; Minaj’s initial tweets about being snubbed were laden with smiley faces and LOLs and jokes—passive-aggressive, perhaps, but not outright angry. Cyrus’s comments were also, ironically, pretty rude: She went beyond the scope of the question she’d been asked to make a comment about Minaj’s character in general, telling one of the biggest newspapers in the world that a popular guest at the ceremony she was about to host is “not too kind.” Was Minaj supposed to go on the same stage as her and not respond?

Was Minaj supposed to go on the same stage as Cyrus and not respond?If the moment was, as some have speculated, “faked”—ratings-chasing collusion between all pop stars involved—it was a bad PR move for Cyrus. She looked legitimately freaked out when Minaj said her name; her reply was incoherent and shaky, blaming the press for manipulating her words (even though the Times had published her comments as part of a lengthy Q&A in which she ignored the reporter’s invitations to de-escalate). Then she tried to claim moral superiority by saying that she never thought it was a big deal when she lost VMAs, a move that ignores the racial and physical component of the point Minaj had tried to make.

For an example of what it looks like when MTV openly tries to capitalize on intra-celebrity beef, check out the various, stilted Taylor Swift moments of the night—squashing the tension that arose over the same set of tweets Cyrus had referred to by performing with Minaj, putting to rest any resentment from the famous “Imma let you finish” moment by presenting a lifetime achievement award to future presidential candidate Kanye West. But for an example of an actually classic awards-show moment, one that reveals some unspoken rules about civility, and race, and speech, watch the clip of Minaj’s acceptance speech—and be glad that in that moment you weren’t Miley.

The Air Force Tees Up a Battle of the Fighter Jets

If you’re the Pentagon, how do you choose between an aging, but dependable, fighter jet and a brand new aircraft that you’re not quite sure is up to the job? You have them fight it out, naturally.

That’s essentially what the Air Force said it would do when it announced that starting in 2018, it would pit the A-10 “Warthog” against the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter in a series of tests to see if the new F-35s can adequately replace the A-10s, which the military wants to retire. A 40-year-old platform, the A-10 has been described by Martin Dempsey, the joint chiefs chairman, as “the ugliest, most beautiful aircraft on the planet.” It may be old, but as a

On the other hand, if the Air Force’s position is that the F-35A will not cover some parts of the A-10’s CAS mission, the onus is on the Air Force to tell Congress and our ground troops what platform will meet those close air support requirements.

McCain spokesman Dustin Walker echoed those concerns. “Comparison tests on the close-air support mission will be an important step in assessing the capability of the F-35,” he said. “However, serious concerns remain about the Air Force’s capacity to perform the close-air support mission with the oldest and smallest fleet in its history, and when less than half of its fighter squadrons are completely combat ready.”

The F-35 is not going away, of course. As James Fallows wrote in his cover feature last year, the program is “a triumph of political engineering.” McCain and Ayotte have supported it publicly. Unlike other disputes between Congress and the Pentagon over a major defense program, their support for the A-10 doesn’t appear tied to parochial concerns, like the loss of a base or jobs in their state; they aren’t advocating for producing new planes, just to keep the current ones in service.

An added concern for lawmakers is timing. The Pentagon has said that it plans to finish phasing out the A-10 by 2019, but the F-35s won’t be completely ready until 2021. McCain and Ayotte say they haven’t received adequate answers on what the military will do if the U.S. is engaged in ground combat overseas within that gap. (Both Republicans, incidentally, have said that a more aggressive and prolonged U.S. military campaign against ISIS is needed.) Gilmore told reporters that other aircraft could be included in the close-air support testing as well. Given the political loyalty to the aging A-10, the Pentagon’s battle of the fighter jets could be aimed at proving the F-35’s capability to Congress—as much as to itself.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower