Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 354

September 2, 2015

Taylor Swift, ‘Wildest Dreams,’ and the Perils of Nostalgia

Taylor Swift’s music video for “Wildest Dreams” isn’t about the world as it exists; it’s about the world as seen through the filter of nostalgia and the magic of entertainment. In the song, Swift sings that she wants to live on in an ex’s memory as an idealized image of glamour—“standing in a nice dress, staring at the sunset.” In the video, her character, an actress, falls in love with her already-coupled costar, for whom she’ll live on as an idealized image of glamour—standing in a nice dress, staring at a giant fan that’s making the fabric swirl in the wind.

The setting for the most part is Africa, but, again, the video isn’t about Africa as it exists, but as it’s seen through the filter of nostalgia and the magic of entertainment—a very particular nostalgia and kind of entertainment. Though set in 1950, the video is in the literary and cinematic tradition of white savannah romances, the most important recent incarnation of which might be the 1985 Meryl Streep film Out of Africa, whose story begins in 1913. Its familiarity is part of its appeal, and also part of why it’s now drawing flack for being insensitive. As James Kassaga Arinaitwe and Viviane Rutabingwa write at NPR:

To those of us from the continent who had parents or grandparents who lived through colonialism (and it can be argued in some cases are still living through it), this nostalgia that privileged white people have for colonial Africa is awkwardly confusing to say the least and offensive to say the most [...] She should absolutely be able to use any location as a backdrop. But she packages our continent as the backdrop for her romantic songs devoid of any African person or storyline, and she sets the video in a time when the people depicted by Swift and her co-stars killed, dehumanized, and traumatized millions of Africans. That is beyond problematic.

It’s hard to imagine that Swift intended to get this reaction, or even anticipated it. But the all-white “Wildest Dreams” video is, in fact, the culmination of a current running throughout her recent output—a powerful but vague nostalgia, defined less by time period than by particular strains of influence that just happen to be affiliated with a certain skin color.

Related Story

The Nicki Minaj/Miley Cyrus Feud at the VMAs Was About Manners

As The New York Times’ Jon Caramanica pointed out in his review of 1989, the music on the album contrasts with modern pop by harkening back to when hip-hop hadn’t yet infiltrated the mainstream (the only thing she has made in this album cycle that could be thought of as current or futuristic was the “Bad Blood” remix—which, perhaps not coincidentally, included rap). The “red lip, classic thing that you like” and the “James Dean daydream” that are glorified explicitly in “Style” and implicitly in the lyrics of other songs, including “Wildest Dreams,” are old-school, definitionally white images of beauty. And the hunky, chiseled love interests of her recent videos (“Style,” “Blank Space,” and now “Wildest Dreams”) have all been white, and all been associated with the past: Gatsby-like aristocracy for “Blank Space,” Miami Vice and Instagram-ish memory haze for “Style.”

Pointing out these things is not to call Taylor Swift racist, but to emphasize how nostalgia can be inherently political. Swift is white, and she was raised in a society where certain symbols of white dominance and a more-segregated past have been glorified. Popular culture exists in large part to comfort, and the omission of black people from a story set in Africa certainly helps distract from the uncomfortable history of colonialism. But in 2015, there’s a growing popular awareness that things often considered “classic” were directly enabled by oppression, and that looking away from the uglier parts of the past will only perpetuate old problems. If that awareness hadn’t completely reached Swift with regards to windswept colonial romances set in Africa, the backlash to the video will almost certainly be a lesson.

MTV’s Scream: The Kids’ Guide to Slasher Flicks

“#Mindblown”—pronounced “hashtag, mindblown”—is a hell of a line for a serial killer to deliver after revealing his or her true identity. It’s also an incredibly MTV-in-2015 way to unravel a mystery: ridiculous, meme-obsessed, self-mocking, and fun if you don’t think about it too much. Which basically sums up the first season of the network’s Scream, a TV reboot of Wes Craven’s 1996 film that follows Emma, a high-school student, and her friends as they’re targeted by a mask-wearing psycho murderer.

Related Story

'I’m Into Survival': A Nightmare on Elm Street’s Nancy, 30 Years Later

Tuesday’s finale ended with the unmasking of a killer, plenty of blood spatter, a long victim list, and an even longer roster of survivors. In other words, the show, which was renewed for a second season, didn’t stray much from convention. As with the original movie, kids and adults were picked off one by one in gleefully graphic fashion, the town’s blundering police force couldn’t keep anyone safe, there was a requisite film nerd who was constantly analyzing the story through the lens of cinema history, and mysterious phone calls from a killer with a voice changer. Only instead of “Hello, Sidney,” the taunt was, “Hello, Emma,” and the call was coming from an iPhone, not a landline with an antenna.

In many ways, Scream set itself an impossible task in trying to replicate the self-referential winkiness of its predecessor, given that audiences are more fluent in pop-cultural references these days than ever, and horror specifically is a genre that’s constantly adapting and manipulating other works in an effort to stay fresh. It was certainly buoyed by its connection to Craven, an executive producer who had little involvement in the show, and whose recent death has prompted multiple reflections on his uncanny ability to constantly reinvent horror. In that sense, Scream the show failed to offer any new insight into what’s changed in slasher stories over the past 20 years—its conclusion: not much—even if it was nevertheless pretty fun to watch.

If you could get over the smugness of the premise—and accept the dearth of diversity and improbable levels of attractiveness among the main characters—the soap-opera feel, gross-out deaths, and measured campiness made it work. In many ways, Scream was more enjoyable and cohesive than the second season of True Detective (an opinion that gained surprising traction on Twitter during TV’s summer doldrums) as well as the latest season of American Horror Story.

The show had some clunkier moments, mostly in its attempts to point to how much technology’s been updated since the original: There’s something weirdly un-threatening and un-cinematic about bargaining with a killer via text message. But on a more positive note, it attempted to follow through on how technology can turn people into predators and victims. Some girls were cyber-bullied and slut-shamed after videos of secretly filmed intimate encounters went viral (usually in the form of everyone at a single high school getting a text of the video at the exact same time). And in another modern touch, Emma agonized over the ethics of outing someone without their permission after a video of her bisexual friend kissing a girl went viral.

In many ways, Scream set itself an impossible task in trying to replicate the self-referential winkiness of its predecessor.Like its predecessor, Scream was replete with nods to horror forebears (Saw, Halloween, The Faculty, and The Castle of Otranto) as well as contemporaries (Hannibal, American Horror Story, The Walking Dead). And it also constantly tried to spell out its relevance to viewers by liberally name-checking current pop-culture references: Daenerys Targaryen, Etsy, The Babadook, hybrid cars, Taco Tuesday, texting and driving PSAs, and Taylor Swift as a verb. (As in: “Maybe Audrey will Taylor Swift her anger into creative energy.”)But at times, the referentiality felt less like a tribute and more like a crutch. The curated, seen-it-all-before teenage hipness was perhaps the defining attitude of the show, but it also served to preempt any criticism for unoriginality (think of all the sequels, good and bad, that use self-awareness in this way too).

Indeed, there’s something hypocritical to the entire effort of satirical slasher-movie stories; this is something both Screams have in common. Their cynicism is mostly an act—it’s just a way to convince the audience that the creators are in the joke, and that they know the audience is in on the joke too. It’s a cover for their sincere and inherently optimistic belief that audiences can still be amused or scared by something they’ve seen so many times before.

It might be misguided to willfully trot out old tropes—where the police never call for backup, where a group stupidly splits up—until the end of time and expect people to be charmed by it as long as they’re reassured by filmmakers, “We know.” But combined with a mystery filled with red herrings, betrayals, the occasional HAIM song, and a Bechdel-Wallace Test-passing script, sometimes it works. When the killer was unveiled at the end of Scream, the show seemed to miss the fact that a lot of people had already pegged the culprit. But the surprise or the twist isn’t always what makes a story worth watching, and for those who saw the ending coming, Scream can simply, rightfully say: “Well, what else did you expect?”

An Elegy for McDonald’s Breakfast Hours

To fully gather the vital feathers of the Egg McMuffin, you first have to start with Eggs Benedict.

The Benedict is an American invention. While its origins are disputed, the dish is generally credited to Lemuel Benedict, a Wall Street stockbroker and society gadabout who wandered into the Waldorf-Astoria with a hangover one morning in 1894 and made a fussy order. The alchemy of buttered bread, egg, pork, and hollandaise was undeniable. A variation of the dish became a staple on the hotel’s menu, before eventually becoming ubiquitous at breakfast spots—from white-cloth napkin joints to paper napkin downtown diners—across the globe.

One man who loved Eggs Benedict was Herb Peterson. Three-thousand miles from Park Avenue, the former ad man and McDonald’s franchisee futzed around in a kitchen in Santa Barbara, California in 1971 and created the Egg McMuffin. It was designed to be a quick-service version of the Benedict, an homage that replaced poached eggs and hollandaise, respectively, with eggs cooked in a Teflon ring and cheese. American cheese, naturally.

Related Story

How the McDonald's Arches Can Be Golden Again

Though we may revel in regional cuisines, somewhere between Betsy Ross and economic deregulation, the Egg McMuffin became America’s national breakfast sandwich. By 1987, 25 percent of all breakfasts eaten outside of the American household were consumed at McDonald’s.

On Tuesday, in a yield to customer demands and some business struggles, the company finally announced that next month it would begin offering some of the items in its breakfast arsenal all day. “America’s breakfast prayers have been answered,” one lede crowed. “Now, McDonald’s has heard our call,” another added.

But this news should also make us sad. As breakfast’s gyre widens, a national ritual will be lost. A sacred context of time, place, and sustenance will be betrayed, and a nook where something inviolable once fit will be filled in.

On the off-chance you don’t have an example, memory, or regimen, I’ll spot you one that an old coworker of mine posted on Facebook on Tuesday.

Breakfast before daycare with Mama is one of my earliest memories. We had just moved to Chicago and she was both working overnight ER and going to medical school in the daytime. Our quality time was in the mornings. Sometimes between buses on our schlep to my daycare in Skokie, we would stop at the McDonald’s Play Land. Every time I passed her on the carousel she’d give me a bite of a hash brown or some sausage. What a boss—achieving her career goals while making sure my ass was full of energy and love and play. Sometimes I do a McMuffin with the dog and nostalgic flavonoids transport me to being three. The standardization of the sandwich has allowed me to have that sensory memory so many years and miles away. And that’s why I love corporations.

Part of why we now demand breakfast at all hours is because the old strictures of workday and place have been shed. “In our 24/7 world, consumers want what they want, when they want it,” a Dunkin’ Donuts executive told Slate in May. “We are seeing breakfast permeate through the entire day.”

Indeed, earlier this year, Taco Bell, which got into the breakfast game just last year, launched a dystopian ad campaign, “The Routine Republic,” likening the ubiquity of the McDonald’s breakfast ritual to a Communist regime. The virtuous were a group called the Breakfast Defectors, who broke with conformity by decamping to a dacha where Egg McMuffins were not welcome. (As of this writing, Taco Bell’s breakfast still ends at 11 a.m.)

Despite all this terrifying freedom, the cruel breakfast cut-off was something that not only kept order, but also united us as eaters. Over the past few weeks, as speculation about the expansion of breakfast has grown, many have referenced the famous McDonald’s scene from the 1999 comedy Big Daddy in which Adam Sandler and his adopted son scramble and fail to get to McDonald’s before breakfast ends. Semi-hilarity ensues:

Big Daddy, you might remember, is about a grown-up child upon whom adulthood is unexpectedly thrust when he hastily adopts a boy to win back the heart of Kristy Swanson. The McDonald’s scene works because most of us know the frustration of missing the cut-off for breakfast. Many of us also know the joy of making it and the slyly intimate experience of quietly sharing breakfast with a room full of strangers. The subtext here is that adulthood consists of both knowing that breakfast ends at 10:30 a.m. and getting there in time.

The seeming injustice of Big Daddy isn’t why McDonald’s is turning breakfast into an every hour affair. The fast-food breakfast freakout scene in Falling Down, the 1993 Michael Douglas drama, feels like a better representation of what’s actually happening here.

“Every act of rebellion expresses a nostalgia for innocence and an appeal to the essence of being,” Camus once wrote.

In demanding eternal breakfast, America is reverting to its adolescence. It wants what it wants and cares not for the rules or the structures that kept us together. Or to put it another way: “This is the consumers’ idea,” one McDonald’s executive told The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday. “This is what they want us to do.”

Server-less Restaurants Might Be the Future of Dining

Before there were fast-food restaurants, and long before there was fast-casual, there was a dining experience that was faster and casual-er than anything that would follow it. The automat, the original server-less restaurant, took the logic of the vending machine to a social extreme: It offered, generally, a wall of small cubbies that contained food both fresh and less so, prepared by unseen humans. Patrons could drop a few coins into the slots, and out would pop a cheeseburger or a tuna salad or a candy bar, instantly and readily and just a little bit magically.

Automats were convenient and fast and, for a time in U.S. history, extremely common; the main thing about them, though, was that they were extremely cheap. They were places you went, generally, when you had no place else to go, and were particularly popular in cities, providing sustenance to laborers and artists. Neil Simon once called the automat “the Maxim’s of the disenfranchised,” which sums the whole thing up pretty well. For most of American history, the dining-out experience has been closely tied with the social experience of being served; take away the servers, and what you were doing was less “dining” than simply “eating.”

The efficiencies are maximized; the serendipities are minimized. You are, as it were, bowl-ing alone.Today, of course, automats have all but disappeared—victims, for the most part, of the quick rise of fast food. Except: They may be coming back. We might be seeing a renaissance of the automat—one aimed, this time, not at the poor, but at the rich. This week sees the opening of Eatsa, a San Francisco restaurant that claims to be “fully automated.” The ordering takes place via iPad; the picking up takes place via a wall of glass-doored cubbies. The food—all served in bowls—is vegetarian, with quinoa as its base; customers can order standard concoctions like the “burrito bowl” and the “bento bowl,” or they can customize their own.

Eatsa, contra its branding, isn’t actually “fully automated.” The food, of course, still has to be prepared by human hands; it’s just that the messy business of the prep and assembly is conducted behind the scenes, preserving the automat-esque illusion of magic. The core premise here, though, is that at Eatsa, you will interact with no human save the one(s) you are intentionally dining with. The efficiencies are maximized; the serendipities are minimized. You are, as it were, bowl-ing alone.

That in itself, is noteworthy, no matter how Eatsa does as a business—another branch is slated to open in Los Angeles later this year. If fast food’s core value was speed, and fast casual’s core value was speed-plus-freshness, Eatsa’s is speed-plus-freshness-plus-a lack of human interaction. It’s attempting an automat-renaissance during the age of Amazon and Uber, during a time when the efficiency of solitude has come to be seen, to a large extent, as the ultimate luxury good. Which is to say that it has a very good chance of success.

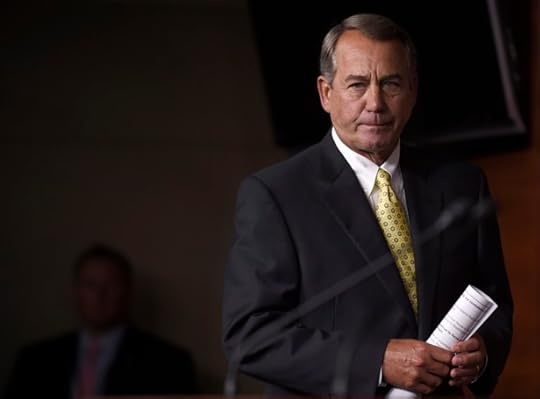

The Plot Against Planned Parenthood and John Boehner

It has become an annual harbinger of autumn in this era of divided government: The calendar swings from August to September, Congress returns from its long summer break, and Republican leaders try to figure out how to keep the federal lights on past the end of the month.

In 2013, John Boehner gave in to Senator Ted Cruz and his conservative allies in the House, and the government shut down for two weeks in a failed fight over Obamacare. A year ago, Boehner and Mitch McConnell succeeded in twice putting off a losing battle over immigration until after they could wrest control of the Senate from the Democrats.

With federal funding set to expire on September 30, conservatives are once again demanding a standoff that Boehner and McConnell are hell-bent on avoiding. This time around, the issue that might prevent an orderly—if temporary—extension of funding is Planned Parenthood. Along with Cruz, House conservatives insist that any spending bill sent to President Obama’s desk explicitly prohibit taxpayer dollars from going to the women’s health organization, which has come under fire over undercover videos that purportedly show its officials discussing the sale of fetal tissue. Democrats have rallied around Planned Parenthood, and an effort to ax its approximately $500 million in annual funding is likely to fall short, either by running into a filibuster in the Senate or a presidential veto.

So what makes this fight any different? For starters, conservatives who once acknowledged the futility of the 2013 shutdown have become emboldened by the anti-establishment fervor sweeping the Republican presidential race, where political novices Donald Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina are all surging in the polls. And second, these same members are now openly threatening a revolt against Boehner through a rarely-used procedural maneuver that could—conceivably—oust him from power.

The latter idea was the brainchild of Representative Mark Meadows, a second-term Republican from North Carolina, and it began in July on something of a lark. Shortly before the August recess, Meadows introduced what’s known as a “motion to vacate the chair.” If successful, it would trigger the election of a new speaker. Republican leaders briefly considered calling a vote on the measure to prove Boehner retained enough support to remain in office. Yet Meadows—or any other member—has the power to force a floor vote within 48 hours through the introduction of a “privileged resolution.” Such a move hasn’t worked in the House in 105 years, but after initially dismissing Meadows’s move as poorly-timed and somewhat bizarre, his allies now see it as something else: leverage.

Representative Mark Meadows (J. Scott Applewhite / AP)

Representative Mark Meadows (J. Scott Applewhite / AP) “I was originally against Mark’s doing what he did,” Representative Mick Mulvaney, a South Carolina conservative, told me by phone. But after hearing from angry constituents in August, he said he’s come around. “Now folks know that the issue of a vote of no confidence is on the table and that if the leadership doesn’t change its course, then it’s sort of hanging over their head like a sword of Damocles.”

For Republicans like Mulvaney, the rise of Trump and the strength of other anti-establishment candidates like Carson, Fiorina, and, Cruz is proof that GOP leaders like Boehner and McConnell have been vastly underestimating the party’s grassroots. What Boehner and McConnell like to dismiss as the fringe, in other words, is actually the majority.

Anti-abortion conservatives view the defunding of Planned Parenthood as a no-brainer, both substantively and politically. “This is so wrong that there is no way we can allow taxpayer money to continue to go to this organization,” said Representative Jim Jordan, who leads a newly formed group called the House Freedom Caucus. Like Mulvaney, he rejected the idea that conservatives were pushing the GOP down the same perilous road seen in 2013. “This is a completely different dynamic here," he argued. “You’ve got an organization on video advocating and engaged in activity that everyone knows is wrong and that appears to be criminal.”

“Our leadership has probably one chance left to save the party, and it’s on Planned Parenthood.”There’s no question the videos have been damaging to the organization, and there’s little dispute among Republicans that it shouldn’t receive government support, especially when the money could simply be shifted to other women’s health groups that are less contentious. But as has been the norm for Republicans in recent years, a debate over tactics has taken on outsized significance. “Our leadership has probably one chance left to save the party, and it’s on Planned Parenthood,” Mulvaney told me. “And if they don’t, if they put up a show vote, or if they sort of say they’re going to fight but then don’t because they knew that’s what they’re going to do anyway, then the party is done, and Donald Trump will be our nominee, and it will redefine what it means to be a Republican. I don’t know if they get it.”

A Boehner spokesman said no decisions on the spending bill, known as a continuing resolution, would be made until lawmakers return to Washington next week. McConnell has been more blunt. Since taking over in January, the Senate majority leader has been in the business of managing expectations while Obama remains in office. He’s sworn off another shutdown, and on Tuesday he conceded that the conservatives’ Planned Parenthood strategy is destined to fail. “We just don’t have the votes to get the outcome that we’d like,” McConnell told WYMT in Kentucky.

I would remind all of your viewers: The way you make a law in this country, the Congress has to pass it and the president has to sign it. The president has made it very clear he’s not going to sign any bill that includes defunding of Planned Parenthood, so that’s another issue that awaits a new president hopefully with a different point of view about Planned Parenthood.

To many Republicans, that’s just an honest assessment of the political reality. To conservatives like Cruz, Mulvaney, and Jordan, it’s defeatist. Cruz, who accused McConnell of lying to Republicans earlier in the summer, has already vowed an aggressive fight to defund Planned Parenthood in December. And how many of the other 16 Republican presidential candidates join his call could determine the level of outside pressure McConnell and Boehner will face. McConnell, however, has a firmer hold on his position than Boehner, who lost a record 25 Republican votes when he was reelected as speaker in January and has shown a tendency to underestimate the level of opposition within his conference.

Would Meadows actually pull the trigger and force a vote to try to remove Boehner? He was vague during an interview on Tuesday, saying that his resolution was designed to prod the leadership into including more conservative voices in its decision-making and agreeing to other process reforms. “For me it’s more about changing the way that we do business as opposed to changing the actual person,” Meadows told me. “A lot of it will depend on what happens during the month of September and maybe the few weeks that follow that.” Meadows, who was briefly stripped of a subcommittee chairmanship for voting against the leadership, has criticized a “culture of punishment” in the House GOP, but he said his effort was not aimed at retribution for himself. The Planned Parenthood fight, he said, would be “a huge factor” but not “a litmus test” in his decision.

Boehner’s allies have scoffed at Meadows’s maneuver, in large part because neither he nor any of his conservative colleagues have put forward a plan—or an alternative Republican candidate—if the speaker is actually deposed (which remains an unlikely scenario). Representative Tom Cole of Oklahoma likened it to “blackmail” and said it was “a very reckless strategy” that could empower Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats. “If they want to bring it up, bring it up,” Cole said. “I’m tired of people threatening members of their own team. What’s wrong here is Republicans treating other Republicans like they’re the enemy.”

“Go win some elections ... You get a different president, we’ll take care of Planned Parenthood.”On Planned Parenthood, Cole said he strongly supported defunding the group, but not if it led to a government shutdown. “Just because you want to do something doesn’t mean you actually have the political power to accomplish it,” he said. “Go win some elections. I think we’re always inclined to reach beyond what we can do. You get a different president, we’ll take care of Planned Parenthood. But having a fight this fall that you can’t win? That strikes me as unrealistic.”

Whether victory is realistic or not, the question of when and how far to fight has divided Republicans for four years. And as the debate over Planned Parenthood and government funding will soon show, that battle rages on, as strong as ever.

September 1, 2015

Saturday Night Live’s Talent Problem

Since the departure of many of its biggest stars two years ago, Saturday Night Live has mostly avoided major cast changes. Yesterday, NBC announced the show would add only one new cast member for its 41st season—the near-unknown stand-up comic Jon Rudnitsky. SNL is, of course, a sketch-comedy show, but it keeps hiring mostly white stand-ups who have a markedly different skill set, with limited results. As critics and viewers keep calling out for greater diversity on the show, it’s hard to imagine the series’s reasoning in sticking to old habits.

Related Story

What's Wrong With Saturday Night Live's 'Weekend Update'?

As is unfortunately typical today, controversy has already arisen over some tasteless old jokes from Rudnitsky’s Twitter and Vine feeds, similar to the furore that greeted Trevor Noah’s hiring at The Daily Show this summer. But Rudnitsky was apparently hired on the back of his stand-up performances, not his Internet presence, similar to the other young stand-ups the show has hired in recent years: Pete Davidson, Brooks Wheelan (since fired), and Michael Che. It’s a peculiar route to the show, because SNL is 90 percent sketch acting, and unless you’re hosting Weekend Update (like Che), you’re not going to do a lot of stand-up material. So why hire Rudnitsky?

The simplest answer is that SNL already has plenty of great sketch actors. The current stable of stars includes Kate McKinnon, Taran Killam, Cecily Strong, and Jay Pharoah, along with old hands Bobby Moynihan and Kenan Thompson. Their forte is impressions and wild recurring characters, and newer hires Beck Bennett and Kyle Mooney have taken up the more esoteric humor of the digital shorts pioneered by Andy Samberg. What SNL is looking for is another Seth Meyers, or Jimmy Fallon, or Norm MacDonald, or Dennis Miller—a magnetic personality who can serve as a straight man in sketches, and perhaps eventually take over the Update desk.

The current co-host of Update alongside Che is the show’s head writer, Colin Jost (also a stand-up), but he’s never quite settled into the role. It’s hard to imagine Jost and SNL showrunner/producer Lorne Michaels are looking for a replacement this early, but Rudnitsky will have a chance to find his place and join the pool of potential understudies. Some stand-ups have struggled to take to sketch acting—Wheelan, hired in 2013, left a year later after barely appearing in any sketches and only managing to get a few Update monologues onto the show. Davidson, hired last year, has made a smoother transition, although he also got the most attention for his Update appearances.

More than anything, Rudnitsky’s hiring demonstrates that despite last year’s creatively rocky season, SNL still has no intention of changing its strategies too much, even two years after its big shake-up. Rather than bring in a big stable of brand new talent, Michaels is making little alterations here and there, moving Che up from the writer’s room to Update (a work in progress), and also promoting writer Leslie Jones to cast status (a major success). More tweaks may come as the season gets under way, or perhaps Jost and the cast will finally gel after a year of working together. But more likely is that the show’s producers will eventually have to start plumbing other arenas of comedy again to find some fresh faces. Outside of established improv troupes like The Groundlings and talent stables like the UCB, there’s the wider world of the Internet, which Michaels has so far been slow to mine. But if one more white stand-up comedian in the cast doesn't help SNL find its groove, there may not be any other choice.

Saturday Night Live's Talent Problem

Since the departure of many of its biggest stars two years ago, Saturday Night Live has mostly avoided major cast changes. Yesterday, NBC announced the show would add only one new cast member for its 41st season—the near-unknown stand-up comic Jon Rudnitsky. SNL is, of course, a sketch-comedy show, but it keeps hiring mostly white stand-ups who have a markedly different skill set, with limited results. As critics and viewers keep calling out for greater diversity on the show, it’s hard to imagine the series’s reasoning in sticking to old habits.

Related Story

What's Wrong With Saturday Night Live's 'Weekend Update'?

As is unfortunately typical today, controversy has already arisen over some tasteless old jokes from Rudnitsky’s Twitter and Vine feeds, similar to the furore that greeted Trevor Noah’s hiring at The Daily Show this summer. But Rudnitsky was apparently hired on the back of his stand-up performances, not his Internet presence, similar to the other young stand-ups the show has hired in recent years: Pete Davidson, Brooks Wheelan (since fired), and Michael Che. It’s a peculiar route to the show, because SNL is 90 percent sketch acting, and unless you’re hosting Weekend Update (like Che), you’re not going to do a lot of stand-up material. So why hire Rudnitsky?

The simplest answer is that SNL already has plenty of great sketch actors. The current stable of stars includes Kate McKinnon, Taran Killam, Cecily Strong, and Jay Pharoah, along with old hands Bobby Moynihan and Kenan Thompson. Their forte is impressions and wild recurring characters, and newer hires Beck Bennett and Kyle Mooney have taken up the more esoteric humor of the digital shorts pioneered by Andy Samberg. What SNL is looking for is another Seth Meyers, or Jimmy Fallon, or Norm McDonald, or Dennis Miller—a magnetic personality who can serve as a straight man in sketches, and perhaps eventually take over the Update desk.

The current co-host of Update alongside Che is the show’s head writer, Colin Jost (also a stand-up), but he’s never quite settled into the role. It’s hard to imagine Jost and SNL showrunner/producer Lorne Michaels are looking for a replacement this early, but Rudnitsky will have a chance to find his place and join the pool of potential understudies. Some stand-ups have struggled to take to sketch acting—Wheelan, hired in 2013, left a year later after barely appearing in any sketches and only managing to get a few Update monologues onto the show. Davidson, hired last year, has made a smoother transition, although he also got the most attention for his Update appearances.

More than anything, Rudnitsky’s hiring demonstrates that despite last year’s creatively rocky season, SNL still has no intention of changing its strategies too much, even two years after its big shake-up. Rather than bring in a big stable of brand new talent, Michaels is making little alterations here and there, moving Che up from the writer’s room to Update (a work in progress), and also promoting writer Leslie Jones to cast status (a major success). More tweaks may come as the season gets under way, or perhaps Jost and the cast will finally gel after a year of working together. But more likely is that the show’s producers will eventually have to start plumbing other arenas of comedy again to find some fresh faces. Outside of established improv troupes like The Groundlings and talent stables like the UCB, there’s the wider world of the Internet, which Michaels has so far been slow to mine. But if one more white stand-up comedian in the cast doesn't help SNL find its groove, there may not be any other choice.

‘The Meatball’ vs. ‘The Worm’: How NASA Brands Space

“It’s a design nightmare,” Greg Patt, a publishing contractor for NASA, sighed. He was talking about the logo that’s been the space agency’s official one since 1992: the blue sphere meant to suggest both Earth and other planets, its interior sprinkled with stars of white and and belted with the letters N-A-S-A, all of it connected by a swoopingly aeronautical chevron of red.

That logo, making news because of a Kickstarter campaign to create a hardcover version of the old, be-bindered NASA Graphics Standards Manual, has come to be known as “the meatball.” That’s in part because of its connection to aeronautics—the optical approach nicknamed the “meatball landing system” has long helped Navy pilots to land on aircraft carriers—but it’s also because of its visual clunkiness. The meatball, originally created to suggest NASA’s ability to move the nation forward into new frontiers, now reeks of retrofuturism.

As such: The meatball has been, long before 1992, a subject of disagreement at the space agency. Its biggest competition? NASA’s other long-time logo, its now-unofficial one: the logotype, sleek and rounded of edge, that came to be known as “the worm.”

[image error]

The worm came about in 1974. The Apollo program had just ended, and NASA, which had become almost as skilled at public relations as it had become at space exploration, was in need of an image revamp. The agency hired professional designers through the National Endowment for the Arts’s Federal Graphics Improvement Program, which sought to revamp government agencies’ visual branding. The designers’ charge? To come up with a logo that would speak to NASA’s future rather than its past. To get people excited, once again, about what a national space agency could achieve.

The design the studio Danne & Blackburn came up with—N-A-S-A spelled out in thick, red lettering, the edges of its As curved to call to mind the noses of rockets—was aggressively simple. And that was the point. The logo’s stark clarity suggested that, whatever NASA would do going forward, its history would speak for itself. In 1975, the agency officially adopted the logo whose peak-and-valley letters, reminiscent of limbless locomotion, came to be known as “the worm.”

Related Story

The Gmail Logo Was Designed the Night Before Gmail Launched

The logo, Wired notes, “was a hard sell to an organization full of engineers who couldn’t care less about kerning and color swatches”—many of whom were, despite their agency’s PR needs, nostalgic for the NASA of the moon-walking years of the 1960s and early 1970s. Among designers, however, the worm quickly became beloved. “If the meatball shows us what made NASA so thrilling—rockets, planets, and sexy-sounding hypersonic stuff,” the design critic Alice Rawsthorn notes in her essay “The Art Of The Seal,” “the worm simply suggests it, and does so with such skill that it’s become the design purists’ favorite.”

The next decades, however, found NASA, at least in the public imagination, limiting its ambitions. From the heady days of the “giant leap for mankind” came Skylab, and with it the shuttle program, and with it the Challenger disaster. By the early 1990s, NASA was in need of yet another public image overhaul. It started, yet again, with its logo.

This time, the rebranding came almost by accident. In 1992, the new NASA administrator Daniel Goldin paid a visit to Virginia’s Langley Research Center. Langley’s hangars had retained the pre-1975 NASA logo, its red, white, and blue insignia still painted onto their doors. Langley’s director, Paul Holloway, saw an opportunity. As Goldin recalls to The New York Times, “He said, ‘If you want to really excite NASA employees about changes coming, why don’t you tell them we’re going to de-worm NASA and bring back the meatball?’”

Goldin asked a White House official traveling with him whether he could, indeed, just re-meatball the space agency. Yes, the reply came, he could. And so, in an address to Langley employees, Goldin announced the change: NASA was bringing back the meatball. (He added, confidently if optimistically: “The magic is back at NASA.”)

And: “They went wild,” Goldin says. “It was an incredible reaction.”

Which is why the NASA of today—the agency that sent a spaceship to the edges of the solar system, the agency that is making plans to put colonists on Mars—has a logo that celebrates the past. Nostalgia is a powerful thing.

Subverting the Rule of ‘Write What You Know’

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean Angela Flournoy set out to write The Turner House, a novel about Detroit, with great unease. Detroit was her father’s city, a place she’d visited but never lived, and she felt unqualified to take on a vast, complex metropolis and its people. In a conversation for this series, Flournoy explained how she came to grant herself permission: A line from Zora Neale Hurston’s book Mules and Men taught her that any subject is fair game. Writers always have license, she told me, as long as they’re willing to do the hard work of building fully realized characters.

Related Story

How Literature Inspires Empathy

The Turner House is a family saga, an urban history, and a ghost story. The novel concerns a small house in East Detroit, the couple who bought it, their 13 children, and the supernatural presence that seems to live there with them. When the book opens, in 2008, the city has seen better days, and the house—thanks in part to the subprime mortgage crisis and a flailing auto industry—is only worth one tenth of its mortgage, bordered by vacant lots and squatters’ camps. Moving back and forth through a 50-year period, Flournoy portrays a family against the backdrop of a quickly changing city, asking how we got from there to here.

Flournoy’s work has appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Times, and The New Republic; The Turner House, her debut, is a finalist for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she lives in Brooklyn and teaches fiction at St. Joseph’s College. She spoke to me by phone.

Angela Flournoy: I first read Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men when I was in the early stages of writing The Turner House—the story of one family’s relationship, over the span of 50 years, with a house in the city of Detroit. At the time, one of the things I was struggling with was: Who do you think you are to be writing this book in the first place? I mean, who do you think you are?

My dad’s from Detroit, but I’m not from there. And I have certainly never seen a haint—the specifically Southern-tradition ghost that’s in my book—in my whole life. In my research, I found many helpful nonfiction books about Detroit but not much fiction—certainly not a lot of fiction about the everyday, working-class black people who make up 80 percent of the population of that city. So I immediately felt the burden of representation: If I write this book, this will be the book that people look to. Who knows when the next novel set in Detroit and focused on working-class black folks will be? When I realized that, I felt more pressure—and more doubt.

But it wasn’t just writing convincingly about an unfamiliar city and its people. I was also concerned about the supernatural element of my story. I didn’t understand the folkloric background of it; I just knew the kind of stories that had been told in my own family. So I started reading everything I could about African American folklore. One of the books I turned to was Mules and Men, which I checked out of the Iowa library.

The book is the result of Hurston’s anthropological research in the South—she went back to transcribe and collect the stories she heard growing up—as well as an account of her time as an apprentice for “hoodoo” practitioners in New Orleans. It’s important to consider the context in which the book was written: At the time, as far as black literature and black scholarship were concerned, there wasn’t much interest in this material. This was the height of the Great Migration. People were leaving the South and trying to prove themselves “worthy,” whatever that might mean, in the North. Part of that meant not being what someone might describe as superstitious. Not having any spiritual beliefs that fell out of the accepted norms. Not being at all messy. But Mules and Men is a book that’s unapologetically messy.

To me, that’s one of the most appealing things about Zora Neale Hurston’s fiction: She’s never been big on cleaning up black lives to make them seem a little more palatable to a population that’s maybe just discovering them. She’s just not interested in that. Even today, in 2015, I know a lot of writers probably struggle with wanting to represent us in a “good light.” The fact that she didn't care, 80 years ago, is just amazing.

One line from the book, from an early section where Hurston is explaining her methods for collecting folklore in the South, stuck with me especially:

Mouths don’t empty themselves unless the ears are sympathetic and knowing.

This line changed how I thought about the work I wanted to do. It’s not about having a background that lines up with the characters you’re writing about, I realized. That’s not the responsibility of the fiction writer. Instead, you have the responsibility to be sympathetic—to have empathy. And the responsibility to be knowing—to understand, or at least desire to understand, the people you write about. I don’t think the quote means you need to handle your characters with kid gloves—I think it means you have to write something true by at least having a baseline of empathy before you start writing it.

I immediately put that line on an index card and stuck it on my cork board. It lived above me for the four years it took to write the book. It was a daily reminder that I would never be able to access these characters, or make them feel real, if I didn’t have in the back of my mind that my job is to be sympathetic and knowing. And it reminded me that, if I managed to be sympathetic and knowing, I would be free to do whatever I wanted.

Readers only balk at writers depicting people who aren’t like them when it feels like the characters are types. It’s when you’ve somehow failed to make fully nuanced and three-dimensional characters that people start to say, what right do you have? But when the characters transcend type, no one questions the author’s motives. Characters’ backgrounds, their gender—these things are only aspects of their personality, just as they are for real people. If the writer pulls it off, if they make you see the humanity in the character, that stuff falls away—no matter who you’re writing about.

Of course, it’s hard when you’re worried about representation, or whether or not you have the right. But at a certain point, you have to be kind to yourself as a writer and trust your own motives. You have to have confidence that you’re coming from the right place. You have to allow yourself to let loose, pursue a good story, and create people who feel real. Not good, not bad, certainly not perfect—just real.

It’s also about following the story, no matter how hard it gets, so that the characters have time to go where they need to go. You have the right to write the characters you choose, but you also have the responsibility to see those characters through—to give them time to become nuanced and real. Once you’ve started you have to go all the way. You can’t go half way.

I’ve found that, if I focus on doing the work every day, the imagination part starts to take care of itself. The beautiful thing about imagination is how it keeps opening doors for your characters to walk through. You’ll be surprised—they’ll walk through these doors, if you free yourself to allow that to happen.

The beautiful thing about imagination is how it keeps opening doors for your characters to walk through.I spent four years with my characters in this novel. The ones I felt I did not know the most were the ones I tried the hardest to know. People always say that, in order to get to know your characters, you need to know what they want, what their needs and desires are. But, in this novel, I went about it in a different way: I was very interested in what they didn’t want, and making them contend with that. I thought about the music they dislike, the people they dislike, how they would never act in a crowd. Maybe that’s a negative way to think about people. But I think, in fiction, the magic often happens when the thing you don’t want to happen happens to you.

It’s interesting because, now, when people tell me which characters they felt they knew the best—they tend to be the ones I felt like I knew least. There were certain characters that I was chasing, trying to get to know better. Even though to me they were always hiding, peeking around a corner, readers say they felt they understood them best. Somehow I was able to transmit more than even I understood about them. I guess, because I was conscious of those characters feeling elusive, I tried harder on the page.

The biggest challenge, for me, though, is to not take this understanding too far. I’m someone who errs too much towards the sympathetic. Even when my characters, based on their actions, could probably be called “bad” people, I still try to find the good in them, know it, and communicate that. In revision and editing, that was one of the things I kept trying to take out. Readers come to the book with all sorts of backgrounds, and they don’t need me to communicate how they should feel about a character. They don’t need me to suggest a character should be excused for his actions because of X, Y, and Z. They’ll make their own decisions. So I’ve always challenged myself, especially if I’m writing from a third person narrator, to editorialize less about the actions that are happening.

People are still reading Zora Neale Hurston because she knew how to strike that balance. She has empathy for her characters, she is deeply knowing, but she never sanitizes or romanticizes them. She lets them be real, and we see ourselves in them as a result.

Kanye West the Millennial

The technical definition of “Millennial” depends on who’s technically defining it, but rare are the generational experts who would say the 38-year-old Kanye West deserves the label that usually applies to people born sometime after 1980. Do you think he cares? Eleven minutes into West accepting the Video Vanguard Award at Sunday night’s VMAs, he placed himself into the same cohort as Justin Bieber: “We are Millennials, bro. This is a new—this is a new mentality.”

Related Story

Nicki Minaj, Miley Cyrus, and the VMAs: A Tone-Policing Palooza

The “we” appears to be any and all artists who don’t censor themselves at awards shows; the “bro” is, despite appearances, a gender-neutral everylistener, the 2015 version of Charlotte Brontë’s “reader.” As for what he means, exactly, by Millennial, the opening line to Pew’s 2010 survey on the matter is instructional: “Generations, like people, have personalities, and Millennials … have begun to forge theirs: confident, self-expressive, liberal, upbeat, and open to change.”

It’s all too easy to line up West’s attributes with those listed above. He’s not just confident; he says he’s a god. He’s not just self-expressive; he receives lifetime achievement awards in self-expression. Liberal? Ask George W. Bush about what he thinks was the worst moment of his presidency. Upbeat? Well, despite his distaste for smiling, West was giggling and dancing in Miley Cyrus’s audience. And as far as open to change—just compare his outfit at the 2008 American Music Awards to the one he wore on Sunday.

West’s kinship with artists who are more traditionally thought of as Millennials is also easy to see. In hip-hop, he’s credited with allowing for a new kind of authenticity—emotionally vulnerable, swaggering but not necessarily street—and on VMAs night, younger emcees like Big Sean and Vic Mensa were seen expressing their gratitude for him; Chance the Rapper tweeted, “Kanye West taught me to be fearless.” Outside of rap, he’s been an influence too. To pick one example from MTV’s stage: Taylor Swift’s vertically integrated brand management owes something to West’s total image control, as does the way she politicizes her personal life, claiming her friends as feminist symbols much as he talks about his marriage as a symbol of racial progress.

In unmooring personality from age bracket, West asks us to see Millennial as a state of mind.And, crucially, like Millennials in many a survey, West is both upbeat about his personal potential even as he’s open-eyed about structural obstacles facing both his progress and humanity’s. Technology and a mysteriously rooted sense of competence have instilled a can-do attitude that doesn’t quite jibe with other peoples’ perception of reality; of course he can conquer the fashion industry in spite of establishment skepticism toward him and his lack of experience, just like of course kids now are optimistic about the future despite living paycheck to paycheck.

Best of all, West asserting himself as a Millennial messes with some of the rhetoric surrounding generational labels—the one-size-fits-all condemnations and celebrations of a hugely diverse group of people who have little in common other than age. Earlier this year, in an Aeon magazine article called “Against Generations,” Rebecca Onion wrote that “Overly schematized and ridiculously reductive, generation theory is a simplistic way of thinking about the relationship between individuals, society, and history. It encourages us to focus on vague ‘generational personalities,’ rather than looking at the confusing diversity of social life.” In unmooring personality from age bracket, West asks us to see Millennial as a state of mind, on that some young people subscribe to and some people don’t. Listen to the kids, bro, no matter when they were born.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower