Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 353

September 4, 2015

The Next Great TV Show (If Someone Will Make It)

Fifteen years ago, when I finished reading Patrick O’Brian’s magisterial 20-novel Aubrey-Maturin series for the first time, I remember thinking, damn you, Horatio Hornblower. C.S. Forester’s renowned nautical protagonist was at the time enjoying the starring role in the British TV series Hornblower, and given the close similarities to O’Brian’s oeuvre—both concern the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic era—it seemed unlikely bordering on inconceivable that anyone would try to adapt the latter for television.

That was, of course, at a time when it almost went without saying that a project of such scope and pedigree would have to be British. But the televisual times have since changed immeasurably for the better on this side of the Atlantic, and now it’s easy to envision O’Brian’s books—which The Times Book Review has hailed as “the best historical novels ever written”—being adapted by any number of networks: HBO, obviously, but also AMC, FX, Netflix, USA … the list grows longer by the month.

Which is a very good thing, because if someone would merely get around to undertaking them, the Aubrey-Maturin novels could easily provide material for exquisite television, offering the action and world-building scale of Game of Thrones, the social anthropology (and Anglo-historical appeal) of Downton Abbey, and two central characters reminiscent of (though far more deeply etched than) Rust Cohle and Marty Hart in the first season of True Detective. Someone really needs to make this happen.

I was reminded of this when I rewatched Peter Weir’s 2003 big-screen O’Brian adaptation, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, on a recent transatlantic flight. It is a fine film (I reviewed it here), but it scarcely attempts to scratch the surface of its principal characters, let alone the rich supporting populations who orbit them.

Those principal characters are Captain Jack Aubrey—brave, gregarious, impetuous, not infrequently subject to romantic indiscretion—and his ship’s surgeon, Stephen Maturin, an accomplished but introverted scholar and naturalist. (He’s also gradually revealed to be a high-level spy, as well as an uncommonly gifted duelist and assassin.) The two meet-ugly at a concert in Minorca on April 1, 1800—Maturin is infuriated by Aubrey’s tapping to the beat “a half measure ahead”—but quickly become fast friends in part thanks to their shared love of music. Together they form what Christopher Hitchens described as “one of the subtlest and richest and most paradoxical male relationships since Holmes and Watson.”

In Weir’s film, Aubrey and Maturin were played, respectively, by Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany. And while both actors offered solid performances, neither was particularly well-suited to his role: Crowe is too dark for Aubrey, and Bettany not dark (or small) enough for Maturin. Properly cast—a pairing such as that of Chris Hemsworth and Daniel Brühl in Ron Howard’s underrated Rush would be closer to the mark—both are potentially career-defining roles, Maturin in particular.

Aubrey and Maturin form “one of the subtlest and richest and most paradoxical male relationships since Holmes and Watson.”Though you wouldn’t know it from Weir’s film, which took place entirely at sea, O’Brian provides solid female roles, too, in Aubrey and Maturin’s contrasting love interests, Sophie Williams and, especially, Diana Villiers. (It’s no coincidence that the author to whom O’Brian is most frequently compared—more than Melville or Conrad or Forester—is Jane Austen.) Outwards from this core are found an absurdly generous constellation of supporting characters: Tom Pullings, Barrett Bonden, Preserved Killick, Padeen (if he wasn’t an inspiration for George R.R. Martin’s Hodor, the resemblance is a remarkable coincidence), Sam Panda, Mrs. Broad, Clarissa Oakes, Heneage Dundas, Capitaine Christy-Pallière, the poor, doomed Lord Clonfert, and on and on.

There would be some narrative issues to untangle in adapting O’Brian’s work for television—chief among them the long, alternating storylines at sea and on land—but material this rich and vast could be sewn together in innumerable ways. And while it would inevitably be an expensive production, Hornblower showed that a similar feat could be pulled off way back in 1998. (Moreover, if financing can be arranged for an excellent but decidedly eccentric literary adaptation such as Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell—well worth checking out, incidentally, for those who haven’t—surely it could be found for a series with the relative commercial appeal of Aubrey & Maturin.)

So if you happen to know a network executive (or, better yet, are one yourself), please raise the idea with all available alacrity. The possibility of historic television, in both senses of the word, awaits. Until then, we will make do with O’Brian’s novels—which, if it is not already apparent, I recommend wholeheartedly to anyone who has not already had the good fortune to encounter them.

Ben Carson Gets His Bounce

The Ben Carson surge that everyone was waiting for is finally here.

The conservative neurosurgeon has been a source of fascination for both the Republican grassroots and the media ever since he critiqued President Obama, who was seated only a few feet away, at the National Prayer Breakfast in 2013. He’s been a steady, if middling, presence in GOP primary polls for most of the year—always earning at least 5 percent, but rarely more than 10. Yet over the last two weeks, Carson has secured a second-place spot after Donald Trump, both nationally and in the crucial opening battleground of Iowa, where he is a favorite of the state’s sizable evangelical community. A Monmouth University poll released this week even showed him tied with Trump for the lead in Iowa, at 23 percent.

That Carson is a different kind of Republican presidential contender is obvious both by his race and his biography: Raised in poverty by a single mother in Detroit, he went to Yale and then worked a series of odd jobs before going to medical school and becoming a world-renowned pediatric neurosurgeon. His best-selling book is taught in home-school classrooms throughout Iowa, which has helped him gain a foothold in the state long before he returned as a presidential candidate.

Related Story

Carson’s popularity with the conservative grassroots has never been in doubt, but the question hovering over his candidacy is whether he would ever become more than a curiosity for GOP voters. An early-June story in The Washington Post lent credence to those suspicions, reporting that Carson’s campaign had been “rocked by turmoil,”which included the departures of several senior staffers. The article gave the impression that the campaign was flying by the seat of its pants, operating as a magnet for political operatives to make money off Carson’s popularity as much as a serious bid for the presidency.

In the three months since, as Carson has dipped and then bounced in the polls, there remains an ongoing debate about whether he has built the kind of campaign infrastructure that can translate grassroots enthusiasm into actual votes. Nowhere is organization more important than in Iowa, where the caucus format demands more time and candidate loyalty from voters.

Matt Strawn, a former state party chairman who is one of the few remaining neutral Republican operatives in Iowa, said he was impressed by the “robust organizational effort” he’s seen from Carson on the ground, both from his official campaign and the super PACs supporting him. “If there are five Republicans in Iowa that are getting together someplace, odds are you’re going to see a Ben Carson person there trying to sign them up,” Strawn told me. The co-chairs of Carson’s Iowa campaign are Rob and Christi Taylor, respected veterans who are influential in Des Moines. Carson’s supporters boasted last year that they had already signed up precinct captains in each of Iowa’s 99 counties.

“If there are five Republicans in Iowa that are getting together someplace, odds are you’re going to see a Ben Carson person there trying to sign them up.”“I think his appeal is firm,” said Steffen Schmidt, a longtime caucus-watcher at Iowa State University. Carson, he said, was picking up support from conservatives who previously backed Mike Huckabee in 2008 and Rick Santorum in 2012—two candidates struggling to recapture the momentum of their previous bids.

Carson’s paid staff in Iowa has grown to 10 since the start of May when it was half of that, said Doug Watts, the campaign’s chief spokesman. “We’ve never had any chaos in the campaign,” Watts said by way of disputing the “turmoil” reported by the Post. “The campaign has sort of incrementally moved and proved and done what campaigns do—fill out and grow from the beginning.” Carson aides have boasted in recent days of raising $6 million in August, more than double the previous month. And in contrast to the money sources of the more experienced Republicans in the race, almost all of Carson’s contributions have come from small donors giving $200 or less. Watts said the campaign had recently received its 400,000th donation and had 275,000 “unique donors,” providing a broad base to which the campaign hopes frequently to return. “We’ll never be hurting for money,” he assured me.

“He won’t go below. He won’t go above. His floor is his ceiling.”Yet despite the protests of the Carson camp, doubts about his organization haven’t totally gone away. “I still think he’s not a threat,” said one veteran Iowa operative with a rival GOP campaign, who also called Carson’s campaign in the Hawkeye State “a smokescreen.” Carson, the operative said, has benefitted from enthusiastic support among the evangelical, home-school community. “The home-school group is motivated. They’re close-knit, and they organize themselves,” the operative said. But he’s also facing more competition for that bloc than did Huckabee in 2008 or Santorum in 2012, and the rival operative argued that Carson has less of a presence in Iowa both in terms of his staff and his own personal visits, which rank in the middle of the pack among the many GOP contenders. “I think that come caucus night, you’ll see him get 12 or 13 percent,” the operative said. “He won’t go below. He won’t go above. His floor is his ceiling.”

Carson’s organization has long relied on direct-mail marketing, and in February he announced that he had hired Mike Murray, the CEO of a direct-mail firm, TMI Direct, as a senior adviser. Murray’s company has gone on to earn more than $1 million from Carson’s campaign, nearly one-fifth of the total it spent during the first half of 2015. Watts said Murray was no longer receiving a salary from the campaign and served only as an outside adviser. “If we didn’t pay it to him, we’d be paying it to somebody else,” he said. Yet to the rival operative I spoke to, Carson’s reliance on direct mail was another red flag in a state where voters are famous for wanting a personal connection with the candidates they caucus for. “That never works in Iowa,” the source said.

The debate over Carson’s organization won’t be settled until caucus time, but why is he cresting in the polls now? He did not seem to stand out in the first Republican debate last month, but he has shot up in the polls since then more than any other hopeful, including Carly Fiorina. As with most other things in this year’s race, the answer might come back to Donald Trump. Conservative voters are clearly looking for outsiders at the moment, and Carson’s anti-Washington message is “Trump without the fireworks,” Strawn observed. He’s a genial man, with a demeanor that’s almost too soft-spoken for a politician.

Carson’s campaign is also perfectly happy to credit Trump. “It’s probably succeeded a little faster than we expected, and quite honestly we owe a little bit of that to Donald Trump,” Watts told me. “He pulled the attention of a lot of Americans to the presidential primary races.”

I think people are realizing, ‘Oh, there are two people singing the same song, but in different keys.’ Quite honestly, that’s accrued to our benefit.

While Trump’s is a “New Yorker style,” Watts said, Carson delivers a similar message in a more “professorial, intellectual way.” Perhaps, then, the Carson boomlet is the first sign of the GOP turning away from Trump, or at least testing out a less bombastic alternative.

And the Carson campaign seems well aware of the GOP electorate’s recent history of elevating candidates only to discard them weeks later—recall that in 2012, Michelle Bachmann, Herman Cain, and Newt Gingrich all topped the polls at one point or another. “We’re realists. We know the game well,” Watts said. “It takes a lot to sustain the effort, to sustain a foothold at the top of the heap or near the top of the heap, and we understand that.” Trying to demonstrate their seriousness, he said the campaign was “ramping up our major donor activity,” although he added that they weren’t ready to announce any big money fish they’d reeled in. For Ben Carson, being a celebrity and the candidate of the grassroots is nice, but it can be both a boon and a burden. And in a crowded, 50-state race for the presidency, it will only take you so far.

September 3, 2015

Mario, Everyman

In what’s become one of the more iconic stories from video-game history, everyone’s favorite Italian plumber was almost named “Jumpman.” Minoru Arakawa, the first president of Nintendo of America, had clashed with the company’s landlord over several months of unpaid rent. Recounting the tussle with his colleagues, Arakawa reportedly joked that their irascible landlord bore some resemblance to the protagonist of the company’s latest arcade game, Donkey Kong. So first in office lore, and then in subsequent games, “Jumpman” was rechristened in honor of their landlord’s given name: Mario.

MORE FROM KILL SCREEN Why We Love Mario The 100 Million Deaths of the Martyr We Call Mario Forget Mario. Let's Talk About Peach.

Mario’s miraculous evolution from office joke to cultural phenomenon has paralleled the development of video games as a creative medium. So it’s worth asking, 30 years after the debut of Super Mario, why and how Mario commands the kind of cultural influence he does. The simplest but least gratifying explanation is simply Mario’s popularity: As of 2015, the character has been featured in more than 116 distinct titles (not counting remakes and re-releases), with over 220 million copies sold. Still, other franchises have sold in similar numbers yet their characters cannot hope to match Mario’s cultural power; sales alone can’t explain Mario’s privileged place in the pantheon of video-game characters.

More important is the immense range of references to Mario in games and other media. When Jonathan Blow designed Braid, his artful deconstruction of the video-game protagonist, he chose Mario—single-minded, hopelessly devoted Mario—as his referent. And though the visual artist Cory Arcangel could have hacked virtually any ‘80s game cartridge, he chose Super Mario Bros. as the basis for his famous image-generator Super Mario Clouds, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Impressive though these statistics and litany of allusions are, they can at most establish the truth of Mario’s popularity. Pressed to explain “why?,” they fail to yield compelling answers. Why should Mario, an “average Joe” if there ever was one, have achieved greater fame than Donkey Kong, the eponymous antagonist in Mario’s debut? How is it that Mario, whose vocational history (plumbing, carpentry, sanitation, etc.) hardly lends itself to world-saving antics, has established himself as the spokesman for an entire medium?

The “secret” to Mario’s popularity lies in his profound average-ness, which allows him to easily adapt to virtually any context. More than once, I’ve heard Mario referred to as a video-game “Ur-Symbol.” This prefix isn’t idle, and helps explain why Mario first garnered and has maintained such cultural power.

Depending on what etymology you accept, “Ur-” is derived from the Sumerian metropolis of the same name, whose recurrent appearance in Western philosophy testifies to the ancient city’s central role in European myth-making, as well as its tremendous conceptual flexibility. When Hegel laid out his teleology of human civilization, he modeled history as a Western tide that originated in the “Near East” but settled on the shores of Europe—Ur to Rome, in other words. The appeal of Ur, in this sense, lies in its evocation of a primal moment, distant enough to be irrefutable but still capable of relevance in changing cultural contexts.

Paradoxically, the Ur-symbol is both eternal and protean. It can be assigned a variety of traits without losing its distinctness. Its qualities are not internal, but external: It means what we need it to. The most famous manifestation of the Ur-symbol is likely the image of Jesus Christ, which has proved an endlessly adaptable anchor of an imagined spiritual community. In his own way, Mario has become a gaming Ur-symbol: His continued relevance through nearly every major paradigm shift in the medium’s history—arcade to console, two dimensions to three, subcultural hobby to ubiquitous pastime—attests to Mario’s unparalleled ability to remain relevant in an ever more heterogeneous community of players and games.

Consider the cast of recurring characters—Peach, Luigi, Bowser, etc.—that accompany (or antagonize) Mario in games set in the Mushroom Kingdom. Though many have starred in their own titles, the identity of each is typically constructed in terms of their relationship to Mario: Luigi is Mario’s brother, Peach, Mario’s lover, Wario, Mario’s anti-hero, and so on. When we call supporting characters’ own titles spin-offs, we acknowledge that there’s something off which they are spinning: that something is, of course, Mario.

In this sense, social life in the Mushroom Kingdom is centered on and around Mario. By extension, the narratives derived from these relations can never escape Mario’s influence, whether or not he is present. And because of the center-periphery relationship between Mario and his acquaintances, games (WarioWare, Inc., Luigi’s Mansion, etc.) that center on any other character than Mario inevitably have a sense of novelty about them.

It’s no surprise, then, that Mario is nearly always the “default” in games that offer multiple playable characters. On the character selection screen of each iteration of Mario Kart, Mario Party, and Super Smash Bros., Mario occupies the first (that is, top left) position in the character grid. Moreover, in games that offer differing stats and abilities for their characters, Mario is nearly always the “standard” character—no particular strengths, but no glaring weaknesses either. When in Mario Kart Toad is labeled as “light” and Bowser as “heavy,” it’s the regulatory presence of oh-so-normal Mario that makes such value judgments possible.

How is it that Mario, whose vocational history hardly lends itself to world-saving, has become the spokesman for an entire medium?Mario’s cardinal trait is simply his “default-ness.” Other characters are inevitably judged on Mario’s terms, and some of their otherness is simply that they are not Mario. The process of establishing their own identities depends, in part, on making it clear that they are not Mario. At the same time, this opens up tremendous flexibility for Mario in terms of the identities he can assume. Over time, this has enabled Mario to pursue a peripatetic vocational itinerary, changing careers like the rest of us change clothes. When other characters are “marked” by the fact that they are not Mario, then Mario himself may be “marked” in any number of ways—Paper Mario, Dr. Mario, Baby Mario ... the list goes on. Perhaps for that reason, Mario has been able to bear the ideas, dreams, and criticisms of countless designers, writers, and players. Perhaps for that reason, he is gaming’s only Ur-symbol.

This is not, however, to discount the role that Mario’s social normativity—a white, straight, middle-class, salt-of-the-earth working man—has played in establishing his place atop the hierarchy of game characters. It is no coincidence that Mario looks like he could belong to one of the demographics that the game industry has served most closely. Books could be written about how Mario, intentionally or no, has reflected and participated in debates over the political values embedded in games and gaming culture.

If that seems a bit unfair to poor Mario, who was never meant as a political statement (except, perhaps, in his turn as a semi-willing ecological activist in 2002’s Super Mario Sunshine), I am surely sympathetic. Realistically, Mario’s race and gender have more to do with the technical challenges designers faced in the early 1980s than with any conspiratorial marketing ploy. Yet to have a legacy is to outlive one’s best and worst intentions. This is the nature of symbols, especially Ur-symbols, which are defined by their capacity to outlive and transcend their “originary” meanings. How else can something so “old” perpetually seem so “new”?

The point isn’t that games need a spokesperson who represents the diversity of the gaming populace (such a spokesperson would surely be impossible), or that Nintendo should be shamed for decisions made so long so, back when the company could barely pay its rent. Rather, it’s that if we have accepted Mario as the putative social and formal center of gaming’s most iconic franchise, then we players also inhabit his periphery at least as much as Nintendo’s other characters do. Our “otherness” is simply that we are not Mario.

And yet.

As players, writers, and fans we all have our claim to him, at least as much as he has a claim on us (just as Jesus, or even Ur, may still matter for those who believe they do). What we know and say about Mario is a measure of what we know of the “other” in ourselves. The diversity of ideas that emerge from Mario speak to our desire to make meanings of his image, eternal and protean, like that mythic capital of an imagined past. To Ur, of course, is human.

Hegel thought as much with his notion of “Urteil,” a concentration of meanings bound within an object that may be teased out over time. These meanings, though, exist sui generis: It is the beholder’s job to reveal them, like Michelangelo seeing his angels trapped in marble. Yet Hegel, in some ways, misstates the truth: The meanings have always been our own. The myth of Ur was always already an image of something lost, mediated not only by the passing of time but by the changing needs of its beholders. Myth, then and now, needs to be animated to be meaningful. Meaning, in other words, needs a player. Mario means nothing until he’s in our hands, wielded and wound up through controllers and keyboards. He’s any man, he’s every man; he’s no man at all.

We Are All Mario

In what’s become one of the more iconic stories from video-game history, everyone’s favorite Italian plumber was almost named “Jumpman.” Minoru Arakawa, the first president of Nintendo of America, had clashed with the company’s landlord over several months of unpaid rent. Recounting the tussle with his colleagues, Arakawa reportedly joked that their irascible landlord bore some resemblance to the protagonist of the company’s latest arcade game, Donkey Kong. So first in office lore, and then in subsequent games, “Jumpman” was rechristened in honor of their landlord’s given name: Mario.

MORE FROM KILL SCREEN Why We Love Mario The 100 Million Deaths of the Martyr We Call Mario Forget Mario. Let's Talk About Peach.

Mario’s miraculous evolution from office joke to cultural phenomenon has paralleled the development of video games as a creative medium. So it’s worth asking, 30 years after the debut of Super Mario, why and how Mario commands the kind of cultural influence he does. The simplest but least gratifying explanation is simply Mario’s popularity: As of 2015, the character has been featured in more than 116 distinct titles (not counting remakes and re-releases), with over 220 million copies sold. Still, other franchises have sold in similar numbers yet their characters cannot hope to match Mario’s cultural power; sales alone can’t explain Mario’s privileged place in the pantheon of video-game characters.

More important is the immense range of references to Mario in games and other media. When Jonathan Blow designed Braid, his artful deconstruction of the video-game protagonist, he chose Mario—single-minded, hopelessly devoted Mario—as his referent. And though the visual artist Cory Arcangel could have hacked virtually any ‘80s game cartridge, he chose Super Mario Bros. as the basis for his famous image-generator Super Mario Clouds, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Impressive though these statistics and litany of allusions are, they can at most establish the truth of Mario’s popularity. Pressed to explain “why?,” they fail to yield compelling answers. Why should Mario, an “average Joe” if there ever was one, have achieved greater fame than Donkey Kong, the eponymous antagonist in Mario’s debut? How is it that Mario, whose vocational history (plumbing, carpentry, sanitation, etc.) hardly lends itself to world-saving antics, has established himself as the spokesman for an entire medium?

The “secret” to Mario’s popularity lies in his profound average-ness, which allows him to easily adapt to virtually any context. More than once, I’ve heard Mario referred to as a video-game “Ur-Symbol.” This prefix isn’t idle, and helps explain why Mario first garnered and has maintained such cultural power.

Depending on what etymology you accept, “Ur-” is derived from the Sumerian metropolis of the same name, whose recurrent appearance in Western philosophy testifies to the ancient city’s central role in European myth-making, as well as its tremendous conceptual flexibility. When Hegel laid out his teleology of human civilization, he modeled history as a Western tide that originated in the “Near East” but settled on the shores of Europe—Ur to Rome, in other words. The appeal of Ur, in this sense, lies in its evocation of a primal moment, distant enough to be irrefutable but still capable of relevance in changing cultural contexts.

Paradoxically, the Ur-symbol is both eternal and protean. It can be assigned a variety of traits without losing its distinctness. Its qualities are not internal, but external: It means what we need it to. The most famous manifestation of the Ur-symbol is likely the image of Jesus Christ, which has proved an endlessly adaptable anchor of an imagined spiritual community. In his own way, Mario has become a gaming Ur-symbol: His continued relevance through nearly every major paradigm shift in the medium’s history—arcade to console, two dimensions to three, subcultural hobby to ubiquitous pastime—attests to Mario’s unparalleled ability to remain relevant in an ever more heterogeneous community of players and games.

Consider the cast of recurring characters—Peach, Luigi, Bowser, etc.—that accompany (or antagonize) Mario in games set in the Mushroom Kingdom. Though many have starred in their own titles, the identity of each is typically constructed in terms of their relationship to Mario: Luigi is Mario’s brother, Peach, Mario’s lover, Wario, Mario’s anti-hero, and so on. When we call supporting characters’ own titles spin-offs, we acknowledge that there’s something off which they are spinning: that something is, of course, Mario.

In this sense, social life in the Mushroom Kingdom is centered on and around Mario. By extension, the narratives derived from these relations can never escape Mario’s influence, whether or not he is present. And because of the center-periphery relationship between Mario and his acquaintances, games (WarioWare, Inc., Luigi’s Mansion, etc.) that center on any other character than Mario inevitably have a sense of novelty about them.

It’s no surprise, then, that Mario is nearly always the “default” in games that offer multiple playable characters. On the character selection screen of each iteration of Mario Kart, Mario Party, and Super Smash Bros., Mario occupies the first (that is, top left) position in the character grid. Moreover, in games that offer differing stats and abilities for their characters, Mario is nearly always the “standard” character—no particular strengths, but no glaring weaknesses either. When in Mario Kart Toad is labeled as “light” and Bowser as “heavy,” it’s the regulatory presence of oh-so-normal Mario that makes such value judgments possible.

How is it that Mario, whose vocational history hardly lends itself to world-saving, has become the spokesman for an entire medium?Mario’s cardinal trait is simply his “default-ness.” Other characters are inevitably judged on Mario’s terms, and some of their otherness is simply that they are not Mario. The process of establishing their own identities depends, in part, on making it clear that they are not Mario. At the same time, this opens up tremendous flexibility for Mario in terms of the identities he can assume. Over time, this has enabled Mario to pursue a peripatetic vocational itinerary, changing careers like the rest of us change clothes. When other characters are “marked” by the fact that they are not Mario, then Mario himself may be “marked” in any number of ways—Paper Mario, Dr. Mario, Baby Mario ... the list goes on. Perhaps for that reason, Mario has been able to bear the ideas, dreams, and criticisms of countless designers, writers, and players. Perhaps for that reason, he is gaming’s only Ur-symbol.

This is not, however, to discount the role that Mario’s social normativity—a white, straight, middle-class, salt-of-the-earth working man—has played in establishing his place atop the hierarchy of game characters. It is no coincidence that Mario looks like he could belong to one of the demographics that the game industry has served most closely. Books could be written about how Mario, intentionally or no, has reflected and participated in debates over the political values embedded in games and gaming culture.

If that seems a bit unfair to poor Mario, who was never meant as a political statement (except, perhaps, in his turn as a semi-willing ecological activist in 2002’s Super Mario Sunshine), I am surely sympathetic. Realistically, Mario’s race and gender have more to do with the technical challenges designers faced in the early 1980s than with any conspiratorial marketing ploy. Yet to have a legacy is to outlive one’s best and worst intentions. This is the nature of symbols, especially Ur-symbols, which are defined by their capacity to outlive and transcend their “originary” meanings. How else can something so “old” perpetually seem so “new”?

The point isn’t that games need a spokesperson who represents the diversity of the gaming populace (such a spokesperson would surely be impossible), or that Nintendo should be shamed for decisions made so long so, back when the company could barely pay its rent. Rather, it’s that if we have accepted Mario as the putative social and formal center of gaming’s most iconic franchise, then we players also inhabit his periphery at least as much as Nintendo’s other characters do. Our “otherness” is simply that we are not Mario.

And yet.

As players, writers, and fans we all have our claim to him, at least as much as he has a claim on us (just as Jesus, or even Ur, may still matter for those who believe they do). What we know and say about Mario is a measure of what we know of the “other” in ourselves. The diversity of ideas that emerge from Mario speak to our desire to make meanings of his image, eternal and protean, like that mythic capital of an imagined past. To Ur, of course, is human.

Hegel thought as much with his notion of “Urteil,” a concentration of meanings bound within an object that may be teased out over time. These meanings, though, exist sui generis: It is the beholder’s job to reveal them, like Michelangelo seeing his angels trapped in marble. Yet Hegel, in some ways, misstates the truth: The meanings have always been our own. The myth of Ur was always already an image of something lost, mediated not only by the passing of time but by the changing needs of its beholders. Myth, then and now, needs to be animated to be meaningful. Meaning, in other words, needs a player. Mario means nothing until he’s in our hands, wielded and wound up through controllers and keyboards. He’s any man, he’s every man; he’s no man at all.

Harry Potter and the Never-Ending Story

September 1st, 2015 marked a curious footnote in Harry Potter marginalia: according to the series’ elaborate timeline, rarely referenced in the books themselves, it was the day James S. Potter, Harry’s eldest son, started school at Hogwarts. It’s not an event directly written about in the books, nor one of particular importance, but their creator, J.K. Rowling, dutifully took to Twitter to announce what amounts to footnote details: that James was sorted into House Gryffindor, just like his father, to the disappointment of Teddy Lupin, Harry’s godson, apparently a Hufflepuff.

Related Story

The Harry Potter Personality Test

It’s not earth-shattering information that Harry’s kid would end up in the same house his father was in, and the Harry Potter series’ insistence on sorting all of its characters into four broad personality quadrants largely based on their family names has always struggled to stand up to scrutiny. Still, Rowling’s tweet prompted much garment-rending among the books’ devoted fans. Can a tweet really amount to a piece of canonical information for a book? There isn’t much harm in Rowling providing these little embellishments years after her books were published, but even idle tinkering can be a dangerous path to take, with the obvious example being the insistent tweaks wrought by George Lucas on his Star Wars series.

Rowling published Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in 2007 as the final entry in a seven-part series, and to emphasize the finality, its last chapter jumps forward in time (to 2017) as Harry sends his second kid off to Hogwarts and reassures him that he’ll be fine no matter what house he ends up in. Every loose end is tied up: the book’s students are older, married off, in varied jobs that suit their personalities, with kids laboriously named after fallen heroes and departed friends. Even within the novel, it reads a little like “fan fiction,” the literary subgenre produced by devotees of existing series that often imagines future adventures and romantic pairings for favored heroes.

So it’s no surprise that Rowling never quite put the saga to bed after Harry Potter came to a close. In interviews after the publication of Deathly Hallows, she pointed out the subtext implying that Professor Dumbledore was gay, although within the books, it’s merely hinted at. In Q&A sessions conducted on Twitter, she routinely drops other pieces of information, some monumental, others ridiculously inconsequential (here’s Rowling describing the location of a bookstore within her magical world). Many of these snippets have come through the Pottermore website (Rowling even wrote a Daily Prophet gossip column as Rita Skeeter). It seems to keep the books’ most devoted fanbase happy, but it also adds to a swelling database of unwritten information that couldn’t find its way into the stories she told.

After all, that’s how Rowling made her name in the first place: writing books whose richly detailed fantasy world powered her storytelling. After finishing Deathly Hallows, Rowling wrote a few other books (one under her name, three under a pseudonym), but she seems drawn back to the extensive universe she created, and to fiddling away on its sidelines. Her efforts parallel George Lucas’s work on Star Wars, a film trilogy he finished in 1983 and took a long break from before returning to it in the mid-1990s in advance of a prequel trilogy.

Though Lucas didn’t write and direct every Star Wars movie, he was at its creative center, and when he decided to remaster the films using more modern special effects for a 1997 re-release, he threw in scenes he’d previously deleted and used CGI to pepper in more creatures in the foreground of his alien landscapes, all to deleterious, distracting effect. Even worse, once his maligned prequel trilogy was released, he returned to the original films again, swapping in newer actors to have them line up with the creative decisions he’d made more than 20 years later. The original cuts of Star Wars are now harder and harder to find, and Lucas’s general influence has been so destructive that fans greeted the 2012 acquisition of the Star Wars brand by Disney with cheers, because it meant the movies were finally out of their creator’s hands. Lucas’s initial interest in adding detail to his world snowballed to the point where he was no longer taken seriously by fans as the creator of his own work.

Can a tweet really amount to a piece of canonical information for a book?Though Rowling isn’t going back to cram new information into her books, her tweets and interview tidbits amount to annotations in the margins, little snips and changes that either sidetrack or highlight whatever points she was originally trying to make. As Lucas has shown, such an impulse can lead to larger changes that are detrimental to the original work. And given that much of the joy in falling in love with fictional characters comes from being able to envision new stories from them, by continuing to embellish her stories long after publication, Rowling is arguably chipping away at that imaginative freedom.

The motivation for Lucas to futz with his own films seems to have been his need to answer questions no one had really asked, in the most obvious ways possible. Mysterious figures like Boba Fett received extensive, plodding backstories, and the romantic decline and fall of the mysterious Jedi was dramatized as being the result of dull bureaucracy. Rowling’s coloring in backstory to inform her actual story is similarly unnecessary—if it really matters that Hagrid couldn’t summon a Patronus, or that Dumbledore remained celibate after a youthful affair gone bad, then presumably those details would have found their way into the writing, rather than being tacked on later.

Rowling has already begun to formally return to the Harry Potter books, writing a play called Harry Potter and the Cursed Child that will be staged in London in 2016. She insists it’s neither a sequel nor a prequel, but more adventures in the Potter world are planned, including a trilogy of films called Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, scripted by Rowling herself, and set 70 years before the books. More formal additions could be on the horizon, considering how much interest Rowling still has in the world she created, but hopefully said works can stand on their own, rather than plugging into a fan-service feedback loop. The more Rowling enhances and embellishes her Harry Potter universe, the less room she leaves for readers to fill in the gaps with their own imaginations.

The Revision of Steve Jobs

An iPhone is a machine much like any other: motherboard, modem, microphone, microchip, battery, wires of gold and silver and copper twisting and snaking, the whole collection assembled under a piece of glass whose surface—coated with an oxide of indium and tin to make it electrically conductive—sparks to life at the touch of a warm-blooded finger. But an iPhone, too, is much more than a machine. The neat ecosystem that hums under its heat-activated glass holds grocery lists and photos and games and jokes and news and books and music and secrets and the voices of loved ones and, quite possibly, every text you’ve ever exchanged with your best friend. Thought, memory, empathy, the stuff we sometimes shorthand as “the soul”: There it all is, zapping through metal whose curves and coils were designed to be held in a human hand.

Related Story

Jobs's Great-Man Theory of Technology

No matter how many years have passed since 2007, and no matter how many generations of iPhone have come and gone, there is still something, in the machine’s anthropology and in its alchemy, a little bit magical. And a little bit mystical. Which is probably why one of the most long-standing clichés about iPhones, and the iPods and the Macs that preceded them, is that they were the first pieces of technology to inspire not just loyalty, but love—love!—among their users. It is probably also why the man who helped to will those products into existence has become not just a kind of secular saint, but also a figure whom history has already included in its pantheon of world-changers and paradigm-shifters. Gutenberg, Lovelace, Darwin, Einstein, Edison … and Steve Jobs. People who, as Jobs liked to say, “put a dent in the universe.”

And there is very little argument to be had here: That’s exactly what Jobs did.

But how, exactly, did he do it? The method in the magic is the subject of Alex Gibney’s new documentary Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine—think Going Clear, but about a person—which offers a decidedly unsympathetic treatment of the man who insisted that “computer” should be spelled with an “i.” The film isn’t arguing against Jobs’s membership in history’s elite cadre of Dent-Putters; it is arguing, though, that he—and we—deserve more than the empty conveniences of hagiography. It’s attempting to rethink Jobs’s legacy in a way that implicates the legend and complicates the lore. The film opens with images of the makeshift memorials erected in Jobs’s honor after his death in 2011. “It’s not often,” Gibney (the film’s narrator as well as its director) remarks, “that the whole planet seems to mourn a loss.”

Cut to a clip of a YouTubed tribute to Jobs starring a kid who looks to be about 10 years old. “He made the iPhone,” the young eulogist says. “He made the iPad. He made the iPod Touch. He made everything.”

It’s quite fair to say, with due respect to both the networked nature of invention and the severe limitations of the great man theory of history, that the kid is right: The iPhone, and the many other devices Apple has produced over the years, exist because of Steve Jobs. He may have been more of a “tweaker,” as Malcolm Gladwell put it, than an inventor, but he was the vision guy. And he was the sell-the-vision guy. Gibney acknowledges that. “He had the ability,” Regis McKenna, who designed Apple’s earliest and most ground-breaking marketing campaigns, tells the director in an interview, “to talk about what this computer could be … He gives people this feeling of forward movement.”

Jobs could be a jerk in the normative sense because he could be a jerk in the narrative. His successes justified his failings.Jobs’s vision—informed by Buddhism and Bauhaus and calligraphy and poetry and humanism, a willful fusion of ars and techne—led to the machines into which so many of us pour our souls and our selves. He staffed Apple with people who “under different circumstances would be painters and poets,” but who in the digital age would choose computers as the medium through which “to express oneself to one’s fellow species.” He emphasized artistry, and spirituality. As Gibney’s voice-over points out: An iPhone’s screen, when the power has gone off and the light from beneath it has been extinguished, ends up reflecting its user.

All of which makes it tempting to ignore another thing about Steve Jobs: He could be, on top of so much else, a terrible person. Not just a jerk, occasionally and innocuously, but a bully and a tyrant. (“Bold. Brilliant. Brutal,” The Man in the Machine’s tagline sums it up.) Jobs regularly parked his unlicensed Mercedes in handicapped spots. He abandoned the mother of his unborn child, acknowledging his daughter only after a court case proved his paternity. He betrayed colleagues who stopped being useful to him. He made the still-useful ones cry. This is on top of the apparent disdain for charitable giving and the Gizmodo fiasco and the stock fraud suit and the many failings of Foxconn.

Those things—and the many other ones that live under the broad category of Steve Jobs’s Personal Failings—are well-documented, in blog posts written both before and after his death, in in-depth biographies both authorized and not, and in Jobs, the feature film released in 2013. Some of those takes treat his shortcomings as mere inconveniences, justifying them away as the common costs of uncommon genius. Others insistently minimize them, seeming convinced that the flaws will tarnish the sheen of their beloved universe-denter.

Others, though, do something that is arguably much worse: They suggest that Jobs’s failings as a person, rather than impeding his legend, actually bolster it. His uncompromising vision, his unapologetic bullying, his tendency to prioritize the needs of computers over the needs of people—all of that, the thinking goes, was somehow necessary. Jobs’s assholery, like his mock turtlenecks and his New Balance running shoes, made him who he was, and thus helped to make Apple what it was. Jobs could be a jerk in the normative sense because he could be a jerk in the narrative. His successes justified his failings.

As Gibney puts it: “How much of an asshole do you have to be, to be successful?”The Man in the Machine rejects those easy tautologies. Here Jobs’s flaws are not just a footnote, but a focus. They are unrelenting. Gibney interviews both Jobs’s confederates and his betrayees, including former bosses (the Atari founder Nolan Bushnell), former friends (the early Apple engineer Daniel Kottke), former girlfriends (Chrisann Brennan, the mother of his daughter), and former employees (the engineer Bob Belleville). He interviews Sherry Turkle, the author of Alone Together and a critic, in particular, of technology’s ability to isolate users even as it promises connection. We get analysis after analysis of Jobs the Jerk, some of them frank (Turkle: “He was not a nice guy”), others accommodating (Bushnell: “He had one speed: full on”), others resigned (McKenna: “I think that Steve was very driven and would very often take shortcuts to achieve those goals”), others indignant (Belleville: “Steve ruled by a kind of chaos: He’s seducing you, he’s ignoring you, and he’s vilifying you”), others angry (Brennan: “He didn’t know what real connection was, so he made up another form of connection”).

Each summation, each person, is a reminder of the sacrifices Jobs imposed on others in the name of human connection. As Gibney puts it: “How much of an asshole do you have to be, to be successful?”

The most intriguing interviewee, though, and perhaps the most damning, is Jobs himself. Gibney obtained previously unseen footage of the deposition Jobs gave to the SEC in 2008 about Apple’s options-backdating scandal—and it functions as a kind of refrain throughout the film. In it, Jobs, clearly annoyed at having to submit to such questioning, occasionally cooperates with the SEC lawyer, but mostly fidgets and sulks and glares. At one point, he tucks his jeans-clad legs up onto his chair, reconfiguring his body into an upright fetal position. At another, when asked why he would want Apple’s board to offer him backdated options, he replies, “It wasn’t so much about the money. Everybody likes to be recognized by his peers,” and “I felt that the board wasn’t really doing the same with me.”

There is, in this SEC interview of the CEO of the one of the world’s most powerful companies, a distinctly pouting petulance. And that somehow puts everything else—the betrayals, the bullying, the blithely self-centric worldview—into human perspective. Jobs was, maybe, a Great Man who was also, in many ways, a small child: self-absorbed and desperate to please, those two things not contradicting but instead, in ways productive and not, informing each other.

Does any of that matter, in the end? Was Einstein, too, something of a man-child? Would Edison, when questioned and challenged, have tucked up his legs in a silent, sulking tantrum? We don’t really know, mostly because these Great Men did their Great Things in the age before video, before social media, before depositions and the documentaries that convert their proceedings into media. They lived in a time that afforded people the luxury of being remembered, and defined, for the What of their lives rather than the Who. Steve Jobs did not have that luck. He lived in a time—we live in a time—when a new holism is being brought to bear on history, when our assessments of our heroes can take into account not just their achievements, but their smaller, human-scaled contributions. We live in an age of complicated idolatry. The irony is that we do so, in large part, because of Steve Jobs.

The Big Question: Reader Poll

We asked readers to answer our question for the October issue: What was the most consequential sibling rivalry of all time? Vote for your favorite response, and we’ll publish the results online and in the next issue of the magazine.

Create your own user feedback surveyComing up in November: What science-fiction gadget would be most valuable in real life? Email your nomination to bigquestion@theatlantic.com for a chance to appear in the November issue of the magazine and the next reader poll.

September 2, 2015

Mr. Robot’s Lies and Liars

Over the 10 episodes of its first season, it became increasingly clear that Mr. Robot is less about hacking computers than about hacking everything—characters, cultures, the audience itself. Whether portraying a tense heist or a psychological breakdown or a corporate climb, the keyword has been “manipulation”: fiddling with reality, and perceptions of it, to get ahead.

Related Story

Whose Side Is Mr. Robot On, Anyway?

Some of the show’s manipulators are better at their jobs than others. Wednesday’s season finale opened with a social-media-enabled adulterer trying to guilt his ex, a therapist, into breaking her client’s right to privacy ... to punish that client for violating other people’s right to privacy. He did not, in the end, persuade her, though the scene itself apparently went through some postproduction tweaks to include a reference to the very-recent Ashley Madison leak. Later, an executive for the data-compromised conglomerate E-Corp aborted his mission—lying to the public about an unfixable crisis—with a gunshot to his head, on live TV.

But then there are the experts, the savvy operators. In the finale, the vigilantes of fsociety covered up their massive cybercrime by fiddling with the physical world—holding a public party to smudge fingerprints at their HQ, repurposing a puppy oven as a hard-drive disposal. E-Corp CEO Philip Price, meanwhile, appeared to be running some sort of scheme to infect the mind of enemy-turned-employee Angela. He frankly told her of his own ruthlessness, and changed the subject when she said he must be interested in her for reasons other than her youthful spunk. The epilogue (you did watch after the credits, right?) hinted that he might use her as leverage against hacker-leader Elliot, provided that’s who he’s fingered as the person behind fsociety (though he might have been talking about the fired exec Tyrell Wellick, or someone else entirely).

Elliot himself appears to have been hacked, with some combination of mental illness, drugs, and desire having bifurcated his conscience: There’s the hoodie-wearing junkie, and there’s the fearless political radical played by an avatar of his dead father. In the show’s ninth episode, that radical, Mr. Robot, indicated that Elliot’s confusion came about by deliberate overmedication from his therapist. But that might be a lie, a self-deception that allows Elliot to undertake dark, difficult tasks under moral cover of amnesia. In the finale, Mr. Robot tried to hack Elliot further, forcing him to face the fact that he’s got a revolutionary living in his head.

What does that revolutionary want? To reveal that all of modern society is a manipulation. With a preacher’s fervor, amid possibly hallucinated throngs of people in Uncle Moneybag masks, he ranted out a grab bag of anti-capitalist talking points—which are also, theoretically, the facts theoretically enabling E-Corp’s power:

Look at it: a world built on fantasy. Synthetic emotions in the form of pills. Psychological warfare in the form of advertisements. Mind-altering chemicals in the form of food. Brain-washing seminars in the form of media. Controlled, isolated bubbles in the form of social networks. Real? You want to talk about reality? We haven't lived in anything close to it since the turn of the century. Took out the batteries, snacked on a bag of GMOs while we tossed the remnants in the ever-expanding dumpster of the human condition. We live in branded houses, trademarked by corporations, built on bipolar numbers jumping up and down on digital displays into the greatest slumber mankind has ever seen. You have to dig pretty deep, kiddo, before you can find anything real. We live in a kingdom of bullshit, a kingdom you've lived in for far too long. So don't tell me about not being real. I'm no less real than the fucking patty in your Big Mac.

Perhaps Mr. Robot’s most potent hacker of all is the showrunner, Sam Esmail. As a piece of TV, the finale was mostly brilliant, packed with images likely now seared into viewers’ longterm memory banks: the cold, unblinking eye of the TV camera facing the suicidal E-Corp exec; the strange, faux-casual mannerisms of Elliot and Joanna Wellick as they sized each other up; Elliot, choking himself in a cyber cafe during a delusional fit; Elliot, choked by Mr. Robot up against the NYPD’s American flag lights in Times Square. Even more powerful was the use of music, whether it was Alabama Shakes’s airy “Sound and Color” accompanying Elliot’s new worldview or Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s “Got Your Money” playing on the hackers’ dance floor.

Esmail’s vivid filmmaking is not merely impressive; it’s of a piece with the rest of the show’s themes about misdirection and mood-massaging.The vivid filmmaking style of Esmail and his team is not merely impressive; it’s of a piece with the rest of the show’s themes about misdirection and mood-massaging. A favorite trick of Esmail’s is to let small, possibly vital info drips be overpowered in the audience’s mind by a jolt of wide-screen awesomeness. Take the opening of the finale, when Lenny says that Elliot has proxy servers in Estonia, and “short of that country falling apart, we’re never going to get any real evidence” of his crimes. In the very next scene, a news broadcast indicates Estonia is indeed on the verge of collapse because of the fsociety hack. I missed that fact the first time I watched, because I was too caught up in the goosebump-inducing joy of hearing Time Zone’s bouncily anarchic single “World Destruction” fading in over footage of global protests. But the truth is, we may have been given a vital clue about next season: The big hack could incriminate Elliot in a much smaller one, which could in turn incriminate him in the big one.

Much of the chatter surrounding the first season of the show centered around Mr. Robot’s identity. Now that that question’s been answered—with a winking musical tribute to Fight Club, no less—the show can turn its focus to the big, meaty conflicts set up by this finale. A post-financial-apocalpyse drama, showing the messy and glorious effects of a global reset, is likely to come. So is high-camp corporate conspiracy, telegraphed by the epilogue that showed the hacker known as Whiterose sipping Champagne with what appeared to be the world’s puppetmasters. Elliot, now somewhat aware of what’s happening in his brain, could become a Snowden type—hounded by the people he undermined, becoming famous and messianic in the process. The missing Tyrell might be dead, or he might be the person behind all the chaos, the one arriving at the door in the season cliffhanger. The only certain thing is that the show will keep messing with viewers, as surely as characters mess with one another, as surely as people everywhere mess with people everywhere.

Samantha Bee Disrupts the Late-Night TV Boys Club

For all the changes happening in late-night comedy, and the new hosts taking the chairs of retired veterans like David Letterman and Jon Stewart, the genre remains one of television’s most homogenous fields, populated almost entirely by men. That’s a fact Samantha Bee notes in the official announcement for her new show Full Frontal, which debuts on TBS in January. With Chelsea Handler currently off the air (though prepping for a Netflix show) and The Grace Helbig Show in limbo, Bee will be the only female late-night host on the air.

“Don’t watch my new show just because I’m a woman,” Bee jokes in the promo. “Watch because of my nuanced perspective on world events, my repartee with newsmakers across the ideological spectrum, and of course, these,” she says, lifting her skirt to reveal some comically large prosthetic testicles. It seems ridiculous that in 2015 a gag about needing a Y chromosome to host a late-night talk show would be so cutting, but that’s how slow change has been in coming to this particular school of television.

Bee, of course, has the chops for late night, and is a much safer choice than TBS’s last hire, the stand-up comic Pete Holmes, whose show aired in the slot following Conan for 80 episodes from 2013-14. Holmes’s show was frequently brilliant and made a real effort to subvert the formulas of the talk show genre, but he was a largely unproven name in TV and sadly floundered in the ratings. Bee worked on The Daily Show for 12 years and became one of its best-known correspondents, and if she’s following Conan O’Brien (still unconfirmed for now), is more likely to mesh with his younger-skewing basic-cable audience.

Still, it’s remarkable that Bee is the first female host to emerge in the great late-night shakeup. When David Letterman announced his retirement, CBS and Craig Ferguson also parted ways on The Late Late Show, leaving two big network openings that went to Stephen Colbert and James Corden. Colbert’s hiring was, in many ways, a no-brainer. Interviewed in The New York Times today about The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, CBS’s CEO, Les Moonves, said, “I know people were clamoring: ‘Well, why don’t they get a woman? Why don’t they get somebody diverse?’ All of which we considered.” But when he learned Colbert was available, he realized, “There’s not anything better than that.”

Related Story

James Corden Exemplifies Late Night’s Cheerful New Generation

Moonves doesn’t address what led him to pick Corden for The Late Late Show, although he’s previously commented that he found the British comedian “so appealing” and liked his mix of classic vaudeville comedy with newer, online-friendly stunts. Other recent hires were similar fait accompli to Colbert’s; Lorne Michaels had long had Seth Meyers in mind for Late Night on NBC, thanks to his long work at Saturday Night Live, and Jon Stewart personally picked Larry Wilmore to take Colbert’s place on Comedy Central at 11:30pm, where he’s since thrived. The South African comedian Trevor Noah, who takes over The Daily Show this month, remains the biggest unknown, and one of the most agreeably surprising choices by a network in this era.

How Noah and others will fare remains to be see, and the specifics of Bee’s show are still to be announced, but on paper, she’s a safe bet with tons of behind-the-scenes experience. That such a smart, obvious hire can signal a major change in the late-night landscape shows just how much progress remains for TV comedy in the 21st century.

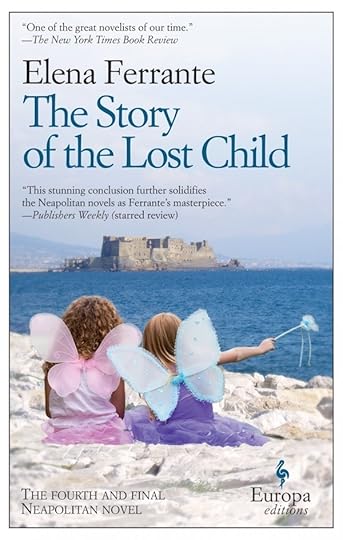

The Story of a New Language: Elena Ferrante’s American Translator

The literary labors of three women have brought American readers the best-selling Neapolitan novels, which have met with a level of acclaim rare for serious fiction of non-English origins. We know the most about Elena Greco, an Italian woman in her mid-60s who responded to the inexplicable disappearance of her friend Lila by painstakingly recording the story of their decades-long friendship, a “story that [she] thought would never end.” She narrates that story through four volumes: “bold, gorgeous, relentless novels,” as one reviewer has called them.

But Elena Greco is fictional. She is the creation of Elena Ferrante, who is herself a creation. Readers know little more about the author than her name, which isn’t her name at all but a pseudonym. She doesn’t go on book tours or give journalists in-person interviews; the resounding success of her novels is due almost entirely to the merits of the text and the glowing reviews they’ve inspired among critics and lay readers alike.

Last, but certainly not least for those of us who don’t read Italian, is Ann Goldstein, a real woman who lives in New York, goes by her legal name, and is the known translator of the mythical Italian Elenas’ penetrating prose.

Ann Goldstein

Ann Goldstein Ann Goldstein has a friend who has a theory that she, Goldstein, is “the real Elena Ferrante.” Goldstein, for her part, firmly denies this theory—one of many about Ferrante’s “real” identity that abound in literary circles these days, as devoted readers welcome the publication of the fourth and final Neapolitan novel, The Story of the Lost Child, in English this month. Goldstein, who is an editor at The New Yorker by day, has used her nights, weekends, and vacations to translate Ferrante’s books into English for Europa Editions since Ferrante’s pre-Neapolitan novel days. (She’s the translator of a number of other Italian works, too, including The Complete Works of Primo Levi, also out this fall.) Translated books, Goldstein says, “hardly ever get this much attention.” And when they do, it’s unusual for much of that attention to be directed at the translator. But Ferrante, by insisting on preserving her own anonymity despite her international audience’s growing curiosity, has (perhaps unintentionally) managed to create an unlikely spotlight for her American translator. “It’s a little odd,” Goldstein told me. “It’s very odd.”

In Ferrante’s world, however, such a dynamic—an author remaining obscure while her translator fields interview requests—seems fitting. As Judith Shulevitz aptly demonstrates in her Atlantic review of The Story of the Lost Child (which will be posted online in mid-September, when the October issue of the magazine comes out), Ferrante does not consider storytelling to be an act anyone truly undertakes alone. The problem of transmission—of stories, of bodies, and lives—preoccupies the author and her narrator through all the layers of metafiction the two “Elenas” offer up. Are daughters bound to become their mothers? Can once-intimate friends ever really separate from one another? To what extent does a writer’s literary achievement render her indebted to the friend who is her muse? Ferrante challenges our ideas about the act of writing itself, so that we are left wondering if a writer’s work always and inevitably contains traces of the words and stories of others that came before it.

Europa

Europa Goldstein is careful to emphasize that she does not, and never could, serve as a stand-in for Ferrante, nor does she consider translating to be a reinterpretation or recreation of Ferrante’s work. Still, she sees the enormous popularity of these novels, and the peculiar circumstances of their Italian author, as endowing her with a responsibility of sorts. “Translated books,” she explains, “get so little attention, and I think the idea that this book is a translated book—I think it’s kind of important for the translator to be a presence.” Goldstein wants American readers to know that works translated into English are not, by any stretch of the imagination, lesser works. And being the public face of Ferrante in America seems as good a way as any to go about reinforcing that notion. “It’s a good advertisement,” Goldstein says, “for translated literature, or for literature in translation, of which there is a surprising amount.”

In many ways, what’s different for Goldstein about this book is not that she doesn’t know the author; it’s that people care so much. The endless speculation about who, where, and what Ferrante is does not make much difference to Goldstein’s translation process. In the past, she tells me, “I’ve worked either with dead authors or with people who haven’t been very interventionist.” Ferrante is no exception, as living authors go. “She hasn’t complained about anything,” Goldstein says. When she has questions, Goldstein can email Ferrante’s publishers, who forward them on to the author; Ferrante can respond via email, through her publishers, who forward the responses to Goldstein. As far as Goldstein knows, Ferrante can read English, but does not read drafts of the translated manuscripts. Ferrante’s translator, in short, knows no more about who she is, really, than any of her other readers do. And Goldstein is fine with that.

“I have the idea of the person—of someone who is writing these books, whether this is her life or not,” Goldstein says, and that’s enough. She feels no need to meet Ferrante. “My view of the writer of these books is [that she’s] a woman of the same generation that I am … I guess I picture her, in a way, most clearly, as the person at the very end of the fourth book. Because that’s after all the person who’s writing the books.” To Ann Goldstein, then, Elena Ferrante’s power lies in the person of Elena Greco, whose bracing, thorough examination of her own life through public narrative is a testament to the power of narrative itself. That Greco’s public narrative is fictional hardly matters. For “many of the people who read Ferrante, whether we’re women or men,” Goldstein says, the reading experience involves “looking into our lives … I think she gives you a way of doing that, or a challenge to do that.” Ferrante issues the challenge; but the way in, for English-speakers, is all thanks to Goldstein.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower