Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 30

December 21, 2016

Martin Scorsese’s Radical Act of Turning Theology Into Art

The face of Jesus appears early in Silence, Martin Scorsese’s new film about 17th-century Jesuits in Japan. The missionary priest Sebastião Rodrigues, played by Andrew Garfield, is speaking at length about his faith and feeling God’s call. Instead of cutting to metaphorical imagery, or to scenes of an actor playing Jesus, Scorsese displays an ancient-looking portrait. Jesus, expressionless in his crown of thorns, stares straight at the audience for what feels like 10 seconds or more. It’s a striking cinematographic choice and an apt metaphor for Scorsese’s depiction of faith: Humans can attempt to describe, emulate, and revere God, but ultimately, this is only imitation, the director seems to say. As the priests discover, sometimes it is impossible to know what this imitation should look like. Yet, no matter how they implore God to speak and show them the way, he is often as loud as a painting. He is, in other words, silent.

Scorsese has been wanting to make Silence for a long time—Paul Elie wrote in The New York Times Magazine that since 1989, when the director read the Shusaku Endo novel upon which the movie is based, “hardly a day [has gone] by without his mentioning the project to the people around him: actors, friends, and even his old parish priest.” The Catholic filmmaker certainly hasn’t stuck to piety in previous projects: Movies like Goodfellas and Wolf of Wall Street are almost gratuitously violent and graphic. Scorsese brings the same sensibility to Silence: We see the blood trail of a decapitated head as it rolls across soft sand; we hear a woman’s screams as she is burned alive. In the context of a movie about faith, though, these gory details create a sense of theological seriousness: Silence is about faith in a world that is broken and appalling, not uplifting and kind.

This is what makes Scorsese’s film so radical, and so unlike many other movies about religion: It’s actually art. The high-quality production, rich with color and historical detail, doesn’t hurt—so often, films with religious themes look hack-y, making them difficult to enjoy.

More importantly, though, Silence engages with ambiguity. “Faith-based film” is the label typically used to describe movies with an agenda: Some, like 2016’s Risen, exist to proselytize, while others, like 2014’s God’s Not Dead, seek to make a narrow argument about politics or culture. For some audiences, this kind of work may be satisfying, and that’s fine. But ultimately, movies in this genre usually aren’t designed to complicate or challenge people’s worldviews; they’re not created to deepen people’s understanding of themselves and the world. Silence, by contrast, treats faith not as a simple point to be made, but as a heart-wrenching puzzle.

The film tells the story of two Portuguese priests who travel to Japan in the 17th century to discover what happened to their missing mentor—Cristóvão Ferreira, played by Liam Neeson—who reportedly committed apostasy after being tortured by the Japanese government. (At that time, Christianity was outlawed in Japan.) Along the way, they find villages full of peasants who had converted under the guidance of previous missionaries, all of whom had died or been driven from the country. Because it is so dangerous to openly practice the religion, the two priests must minister to these nascent Christians in the dead of night, hearing confession and celebrating mass under the cover of darkness.

Rodrigues and his companion, Francisco Garupe, played by Adam Driver, witness the incredible price these converts must pay for their newfound faith. Imperial officers routinely come through the villages and challenge residents to denounce Christianity by stepping on a plate depicting Jesus. The priests are divided on how the peasants should respond: At one point, Rodrigues instructs them to give in and “trample,” while Garupe urges them to resist. The two priests watch as peasants are murdered in gruesome ways—three are hung from crucifixes built by the shore so that waves can pummel them as they slowly succumb to exposure and dehydration. Eventually, both men are apprehended, and they, too, are asked to renounce their savior. As long as they resist, the Japanese officials keep murdering more peasants.

“Fake spirituality is the kind of stuff you see on Hallmark or Lifetime, where if you only believe in God, everything will be fine.”

Scorsese went out of his way to frame these conflicts not as generic crises of faith, but as questions to be explored in a specifically Catholic, Jesuit frame. He hired Father Jim Martin—the priest who serves as editor-at-large of America magazine, the longstanding Jesuit magazine, and who famously pastored to the comedian Stephen Colbert—to consult on the theological language in the script and to work with Garfield. “Andrew came in interested in the Jesuit spirituality, and had asked about Jesuit prayer, and I had given him some introductory prayers,” Martin told me. “It became obvious to me very quickly that this man was being drawn into the Spiritual Exercises, which was a surprise.”

The Spiritual Exercises are central to Jesuit training: The series of prayers and meditations is drawn from the experiences of the order’s founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola, as he discerned his relationship with God. Although lay people do go through the Exercises, it’s not a typical feature of method acting. “To see someone who had had little formal training in prayer enter into the most demanding retreat experiences and give himself to it, and come out on the other side fulfilled and changed, I would say, is something of a miracle,” Martin said.

As Garfield immersed himself in Jesuit spirituality, Martin also reviewed the script for errors of tone and of theology—to more accurately describe the way a Jesuit priest might relate to suffering, for example. The result is a rare deep dive into the Catholic order, whose priests became known in the 17th and 18th centuries for their ability to venture into foreign territories and establish relationships with scholars and dignitaries. It’s catnip for anyone who is interested in Jesuit history or teachings; in late November, the Vatican screened the movie for 300 Jesuit priests, and Scorsese even met the pope.

But to Martin, the appeal wasn’t just in seeing his Jesuit brothers depicted on screen. As a priest, he appreciated that the film does not offer a rosy or simplistic view of religion. “This is real spirituality, not fake spirituality,” he said. “Fake spirituality is the kind of stuff you see on Hallmark or Lifetime, where if you only believe in God, everything will be fine, and no need to worry.” As the characters find out, bad things do happen, even to people who are intensely devoted to their faith, and it’s not always clear what they should do.

The coup is that Scorsese legitimized these questions as fair game for mainstream art.

Among the many questions Silence raises is one concerning the moral ambiguity of mission work: The priests must grapple with the violence they bring upon the peasants. Throughout the film, characters subtly question whether Christianity can truly travel across cultural borders. Imperial officials insist that Christianity cannot “take root” in Japan, and eventually, Ferreira and Rodrigues come to see the country as a “swamp,” a place where the religion could never thrive.

Rather than using Silence as a bully pulpit for a critique of colonial power, though, Scorsese probes the missionary question for ambiguity, portraying the priests’ choices as morally complex. In the end, it isn’t clear that the missionaries, who treated the peasants with dignity, did more harm than good, even though their actions inadvertently resulted in many people’s deaths. Even after some of the peasants chose to step on the plate, imperial soldiers often continued to torture them—the priests brought their faith into a country whose state forces were already, in many ways, hostile to the well-being of the poor. It’s also not clear what they accomplished: Ferreira, the so-called “fallen priest,” offers up the fact that the peasants understood “son of God” to literally mean “sun” as evidence of their misapprehensions about Christianity. This is the power of Silence: It leaves no protagonists free of moral burden, and proposes no firm conclusions to the ambitious questions it takes on.

Artistically, it’s difficult to pull off—to architect a nuanced, respectful interrogation of moral, religious questions in a way that’s compelling and accessible. But the truly counter-cultural coup is that Scorsese has legitimized these questions as fair game for sophisticated, mainstream art. God’s silence is not just a matter for church halls and cathedrals, Scorsese has declared. Any moviegoer can grapple with the meaning of Jesus’s blank stare.

[image error]

And, Scene: Mountains May Depart

Over the next two weeks, The Atlantic will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy moment and unpacking what it says about 2016. Today: Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart. (The whole “And, Scene” series will appear here.)

The director of the 2015 drama Mountains May Depart, Jia Zhangke, has clashed with the Chinese government over the content of his films throughout his career. That’s in part because Jia belongs to the so-called “sixth generation” of Chinese cinema—a more anti-establishment and confrontational approach to filmmaking that emerged in the late 1990s. So it’s not surprising that the director begins his latest film (released in the U.S. in February) in 1999, a year weighted with symbolic and actual importance for a resurgent China preparing to dominate the global stage.

With Mountains May Depart, Jia is telling a story about his country that feels at once hopeful and bleak. This duality is perfectly reflected in the film’s opening and closing scenes, two very different dance sequences set to the same song. As the opening credits roll, the camera pushes in on the protagonist Shen Tao (Zhao Tao) and her friends as they dance to the Pet Shop Boys’ “Go West.” It’s a vision of optimism and youth, simultaneously choreographed and spontaneous; the group is dancing in formation, but with a seemingly joyous lack of practice. Even watching the clip entirely free of context, it’s hard not to be delighted by Shen’s abandon (she’s the woman in denim who eventually leads the conga line).

A satiric anthem for the capitalist western world, “Go West” has lyrics that might feel a bit on the nose for a film about China’s past, present, and future. (Set in Jia’s home province of Shaanxi, an industrial part of central China, Mountains May Depart takes place over three time periods: 1999, 2014, and 2025.) “There where the air is free / We’ll be what we want to be,” Neil Tennant sings. “Now if we make a stand / We’ll find our promised land.”

The movie begins on a jubilant note and ends on a bittersweet one. Its characters are in search of some “promised land,” be it financial success or romantic fulfillment, but as time passes, that goal appears to be stuck forever on the horizon. In the film’s opening, Shen is dancing to “Go West” with her friends, excited for a future that seems limitless. In the final scene, she’s dancing alone to the same song while estranged from her son, husband, and hometown—but not without appreciation for the places her life has taken her.

“The choice of that song comes from my memories of being young, people of my generation being young in 1999,” Jia said in an interview with The A.V. Club. “Whenever it hit midnight, the DJ would play this song and we would start dancing. So when I try to evoke memories of my past, and what I felt like in my body and my mind during that time, it’s interconnected with this song. So it’s not only a personal history that I’m trying to evoke, but a collective history for that generation.”

Mountains May Depart sometimes stumbles in its effort to convey the past of a generation, partly because it also takes on the difficult task of predicting its future. But the film’s ambition is staggering, and the distance it travels between its bookended dance sequences is admirably vast. As the film begins, Shen is a woman caught between two love interests—a poor mine worker and a stuck-up young capitalist—and in telling her story, Jia charts the complicated path the Chinese government has struck in its efforts to modernize and unite its people. Crucial to Mountains May Depart is language and the erasure of local dialects. By 2025, Jia perceives a future in which citizens will need to keep Google Translate open at all times just to talk to each other.

The opening sequence of Mountains May Depart is striking not only in the celebration it depicts, but also in its curious presentation: Jia shoots the entire 1999 story in a 4:3 ratio, the square video frame of ’90s television. It’s the same projection that Jia made his first movies in, and it gives the film a saturated, nostalgic feel, less muddied by the sight of smog or construction (the country’s air pollution, seemingly non-existent in the 1999 sections, seeps in as the film goes on). The later sequences are shot with wider-screen lenses, looking more like a modern blockbuster with every jump forward in time even as Shen’s life begins to feel more limited and frustrating.

Mountains May Depart is a fascinating window into a country that, even today, is still grappling with the legacy of its industrial revolutions and its role in a larger geo-politics. It’s a country that still seems poised to dominate the 21st century, but one where millions of its people, and even its cities, are being forgotten or ignored—a nation where specific cultures are being swallowed up in the name of progress. In Mountains May Depart’s simplest, broadest moments, like the “Go West” scenes, Jia underlines the appeal and the dangers of the future, while cementing his status as a brilliant storyteller for a whole generation.

Next Up: Everybody Wants Some!!

Passengers Is a Journey Best Skipped

Jim Preston wakes up alone. Not your ordinary, alarm-clock-goes-off-in-the-morning alone. Really alone. Series-premiere-of-a-Walking-Dead-franchise alone. The hibernation pod in which he has been sleeping for decades pops open and a hologram of a woman appears to inform him that his 120-year interstellar voyage to the human colony of Homestead II is all but complete.

The hologram guides Jim (Chris Pratt) to his cabin to freshen up in preparation for meeting some of the 5,000 other thawed-out colonists who’ve accompanied him on the starship Avalon. But when he shows up for “Learning Group 38,” he’s the only attendee. Likewise, when he stops by the automated cafeteria, there’s no one else there. Even the “Grand Concourse” mall is devoid of shoppers. What’s going on?

What’s going on, alas, is that the Avalon took damage crossing an asteroid field, which, among other minor glitches, caused Jim’s pod to short-circuit, waking him—and only him—90 years too early. So Jim tries all the obvious fixes: He talks to several of the ship’s computers; but none can even fathom the possibility that he has been awakened early—this has evidently never happened before—let alone offer him any meaningful assistance. He attempts to wake the ship’s crew; but they are deep in their own slumber and locked behind an utterly impregnable bulkhead. He is, as noted, alone.

Well, not completely alone: The ship’s lounge features a cheery robot bartender who is named Arthur and played with twinkly charm by Michael Sheen. (He is, essentially, a less ominous version of Lloyd from the Overlook Hotel.) Arthur offers Jim some generic bartender sentiment about taking each day as it comes—I should warn that this greeting-card-level bromide will make a return appearance later in the film—and Jim takes the advice to heart. As days cycle into weeks, and weeks into months, Jim avails himself of the ship’s luxury amenities, moving into a nicer cabin, shooting hoops, playing a video dance game, and growing a Tom-Hanks-in-Castaway beard. And, with Arthur’s help, he drinks. After all, as Elton John long ago noted, it’s lonely out in space. And given that it’s gonna be a long long time, Jim figures he might as well be hi-i-igh as a kite.

I’d like to offer a brief digression here to point out that none of this setup makes a lick of sense. (Those who prefer can skip to the next paragraph.) A whole ship fully up and running—the pool, the mall, the game arcades, the French and Mexican restaurants with their crudely accented robotic waiters, the self-serve space-walk facilities(!), and, of course, cheery old Arthur—despite the fact that no human being is supposed to be awake for another 90 years? And not a single one of these systems is capable of sensing that anything is wrong with Jim’s premature presence or of rousing the crew? It’s utterly ridiculous—though, I suppose, no more ridiculous than the fact that Jim spends a whole year drinking crummy coffee because he doesn’t have the “gold level ticket” required for macchiatos, but this in no way prevents him from relocating from his tiny, assigned cabin to a posh duplex penthouse.

Passengers is at its most evocative when capturing a state of utter tedium.

But back to the story. One day, when Jim is at a particularly low ebb, he happens to gaze into the pod of one of his many fellow passengers and see a pretty blonde named Aurora Lane (Jennifer Lawrence). Smitten, he looks her up in the ship’s files and discovers that she is a writer (though all available evidence suggests a rather bad one) whose sense of adventure led her to travel to Homestead II in search of a great story.

Ever more convinced that Aurora is his dream girl, Jim agonizes for months over whether or not he should wake her. (Yes, this is way, way stalker-y. Also, I’ll note that while Pratt is good at many things, conveying a state of agonized deliberation is not among them.) On the one hand, Jim would be stealing Aurora’s future from her, dooming her to live, and die, alone on the ship with him. On the other hand, it’s been a whole year and he’s really really lonely. Arthur, meanwhile, is no help at all with this massive, ethical dilemma. “Jim,” he explains, “these are not robot questions.”

Jim eventually does wake Aurora, of course, because paying Jennifer Lawrence $20 million to lie asleep in a tube all movie long would be money ill-spent even by Hollywood standards. At first, Jim conceals what he did from Aurora, and the two begin to fall in love. Later, she finds out, and she is appropriately nonplussed. And a bit later than that, the ship’s ongoing malfunctions start to escalate, necessitating a series of life-or-death action sequences involving our heroes. I’ll leave the details to the curious, with the caveat that nothing that happens is particularly compelling or unexpected.

So what kind of a movie is Passengers? It’s difficult to say. Directed by Morten Tyldum (The Imitation Game) from a script by Jon Spaihts (Prometheus, Doctor Strange), it begins as a kind of high-concept science-fiction film, but ultimately does very little with its initial premise. (Jim and Aurora do not, for instance, contemplate rousing further passengers, or follow any of several other potentially intriguing narrative paths.) Once Aurora is awakened, the movie takes the shape of a romance. But this storyline feels half-hearted and unfinished as well, and it is not helped by the decidedly meager chemistry between the leads. And as for the big action finales, well, the less said, probably, the better.

Ironically, Passengers is at its most evocative when capturing a state of utter tedium, in the early scenes where an ever-more-bearded Jim is eating a bowl of cereal, or lazily shooting hoops, or even sitting in the ship’s movie theater, facing down eternity. In those moments, I felt I was right there with him.

December 20, 2016

The Curious Case of Nile Rodgers's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Award

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame perpetually starts fights about respectability and credibility, and the new class of inductees just shows how shifty and disputed those two words can be. The late rapper Tupac and the grunge band Pearl Jam are in, marking recognition for two ‘90s musical moments whose legacies are still in the making. The folk singer Joan Baez joins; she accepted by saying “I never considered myself to be a rock and roll artist,” a sentiment many rock fans no doubt agree with. Journey, the mega-selling arena act whose coating of cheese has kept them far from critical acclaim, has made it in. So have Yes and Electric Light Orchestra, two bastions of prog-rock musical nerdiness.

The strangest announcement of the day is about the guitarist/songwriter Nile Rodgers, who will receive the Award for Musical Excellence, a recognition that’s only occasionally given out and decided by “special committee” (rather than by the more than 900 musicians, historians, and industry members whose votes determine which five of each year’s nominees get inducted). Rodgers played with Chic, the hugely successful disco act that has been nominated 11 times for the hall of fame but has still not been inducted. Rodgers’s Musical Excellence award recognizes achievements outside of Chic, which includes important work Rodgers did with Sister Sledge, David Bowie, Daft Punk, and others. But still, there’s the air of disagreement behind the accolade for Rodgers: The entire body of hall-of-fame voters evidently doesn’t think Chic belongs, but the smaller group in charge of lifetime achievement awards perhaps does.

Rolling Stone has a somewhat heartbreaking interview with Rodgers today, in which he repeatedly tried to split the difference between gratitude for his award and disappointment that the rest of his band has been left out. “I want to be happy, but I'm perplexed at the same time,” he said. “How do you pluck me out and say I'm worthy of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but this band of mega players is not?

One of the likely suspects for why the hall keeps rejecting the creators of “Le Freak” and “Everybody Dance” is the the endurance of the “Disco Sucks” attitude: Some voters’ late-’70s genre/tribal allegiances may be so strong that it keeps out a group of accomplished instrumentalists and songwriters even as the hall’s definition of “rock” expands to include the likes of Madonna and NWA. This despite the fact that, as Rodgers pointed out to Rolling Stone, Chic recorded lots of music that wouldn’t have played at Studio 54. The unavoidable truth is that gatekeeping institutions have arbitrary biases—as seen in the fact that it took until 2014 for Rodgers to win a Grammy, and it was for a song recorded with two French guys nostalgic for Chic’s heyday:

I am very, very grateful and honestly shocked every time I win an award. When I won the first Grammy with Daft Punk [for "Get Lucky"], I said to the guys, "This is amazing. This is it." They looked at me and thought I had a whole closet full of Grammys. As we were sitting in the audience they kept saying, "You didn't get a Grammy for 'Let's Dance?' You didn't get a Grammy for 'Like a Virgin?' They started naming all these songs. "You had to get a Grammy for 'We Are Family!'" I'm actually very accustomed to not winning stuff. So it's fine with me when I don't win stuff. It's actually shocking when I do.

Another band to be shut out from Grammys for the entirety of a very successful career is Journey, who the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame will now recognize. It might be a stretch to say that such an induction means that with time, everything uncool will become cool—perhaps better to say that many things uncool will eventually be recognized by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

What Is The OA Actually About?

This article contains spoilers through all eight episodes of The OA.

The OA, which was released in its entirety on Netflix this month, is one of the more divisive shows the streaming service has debuted in its history, with critics calling it “a strange, haunting mess,” “beautiful bullshit,” and “a two-hour movie with a seven-hour-plus run time.” For the record, I loved it, though I can understand what might put many viewers off. The very qualities that mark the series as distinctive and ambitious—its labyrinthine plot, its mutating style, its interpretive dance moves—are the ones that also make it potentially infuriating. The finale, which saw the protagonist Prairie’s visions finally manifested in the real world even as they also seemed to reveal her as a fraud, could be either maddeningly ambiguous or offensively clumsy, depending on your worldview.

The OA is dense with clues, allusions, and imagery, some of which contribute to a better understanding of the show, and some of which are still totally baffling. Still, you can come to your own interpretation of the series based on how you relate to the story. For some, the show might be a complex meditation on the aftermath of trauma, as its creators, Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij, have suggested. For others, it might be a meditation on the power of storytelling, and how different cultures have, since the earliest days of language, passed down myths to foster a sense of community. In that, the finale’s ambiguity about whether Prairie (or OA, as she calls herself) was truthful about what happened to her while she was missing is deliberate: It doesn’t matter, since her story serves a larger purpose for the people she tells it to.

But there are also definitive signs throughout all eight episodes that at least some of OA’s visions are real—and, as predicted earlier in the show, they help prevent a great evil from occurring. Since a series as complex as this one seems intended to be forensically analyzed by viewers (and since Batmanglij has directly referenced the clues buried in episodes), it’s worth focusing on some of its smaller pieces to build a greater comprehension of what The OA was trying to do.

For starters, having rewatched most of the season’s episodes, it’s clear that the cafeteria shooting in the finale doesn’t come totally out of left field, even if seems like an odd, sideways lurch. In the very first episode, OA tells Betty Broderick-Allen, or BBA (Phyllis Smith), that Steve’s (Patrick Gibson) aggression and violence is an instinctual response to his surroundings. “It’s not really a measure of mental health to be well-adjusted in a society that’s very sick,” she says. This is emphasized again in the seventh episode when he stabs OA in the leg with a pencil (after, she digs a piece of lead out of her skin that seems to portend her being shot outside the cafeteria). Steve’s tendency to use violence as an outlet to express his deeply rooted pain is felt throughout the series, as are the isolation and trauma of OA’s other misfit followers.

The school shooting itself is also foreshadowed as an event that OA must try to stop. In the fourth episode, when she dies after Hap hits her with his rifle, Khatun tells her, “All five of you must work together as one to avert a great evil.” In the fifth episode, while Betty stares at her reflection in the mirror, a news report in the background mentions a shooter at the mall who escaped after killing seven people. And at the beginning of the sixth episode, OA’s nightmare features a dropped tray, “a clanking sound, like silverware,” and gunshots. “I feel like something terrible is coming, and if I can just solve the puzzle in time, I can stop it from happening,” she tells the FBI agent Elias (Riz Ahmed). He responds by telling her that being psychic, perhaps, is just being able to pick up on tiny cues that others miss. But in her last vision, while she’s lying asleep in the bath, she pieces it together, after a conversation with Alfonso in which he suggests that maybe Crestwood is the missing piece of the puzzle. “I had the dream again,” she tells Abel. “I know. I know what it is now.”

Even if you dismiss OA’s stories about her captivity as a fantastical narrative devised by a deeply traumatized person trying to conceive of a way out, certain elements are indisputable. She was blind when she went missing but could see seven years later, when she returned. Whatever happened to her during those seven years led to malnourishment and vitamin-D deficiency. And she has a vision that causes her to run to the high school, where a shooter is standing with a loaded assault rifle in the cafeteria.

Capping a narrative that has hinted at the possibility of a more spectacular, multidimensional conclusion—one that involves the rescue of OA’s four fellow captives in Hap’s basement—a school shooting understandably feels stark, even cheap, by comparison. But it isn’t unearned. And the group’s silent agreement to perform the movements OA taught them, rather than to run and hide, is a leap of faith—a gesture of desperation, perhaps, but also of hope. Again, whether you find the scene incredibly moving or utterly ridiculous will depend on your tolerance for interpretive dance. (The lovely, haunting music scoring the scene includes Nina/Prairie’s violin solo from episodes prior.) Either way, it confuses the shooter enough to allow the cafeteria worker to tackle him.

The scene also contains moments that seem to suggest OA’s stories about near-death experiences aren’t totally fantastical. At the beginning, when Jesse’s friend is staring out the window, frozen, the shot warps and wobbles a little, as if reality is shifting. After the five complete the movements, the trees blow in the wind and the light changes on Steve’s face, before the camera cuts to OA behind a pane of shattered glass, as if to symbolize her freedom after being behind glass walls for so long. “You did it,” she tells them. “Don’t you see? I have the will.” Then, as the ambulance doors close, Steve hears a whoosh in the air, just like the sound Hap described as the soul leaving the body.

The finale definitively offers more questions than answers. Is OA actually able to read the books that were under her bed, given that in her goodbye note to Nancy and Abel she was barely able to write her name in block letters? What was her FBI counsellor doing in the house in the middle of the night? Why does the color purple recur so much throughout the show? Why can’t OA tell the FBI everything that happened at Hap’s—all the evidence she and her friends supposedly wrote down in their note on the Verizon envelope—in order to help identify him? If her story isn’t true, where did her scars come from?

But as an allegory for the power of faith and community, it all functions surprisingly neatly. Steve, Buck, Jesse, Betty, and French are saved, literally and metaphorically, by their union as a group. The students are freed from their glass-walled, locked-down cafeteria, just like OA hoped to free Hap’s prisoners from their cages. Whether OA’s stories are true or not (“I’m scared, Homer, that’s why I think I made you up,” she says in the first episode), they got her through her imprisonment. “How did you survive so long down there?” Steve asks her after he stabs her in the leg. “I survived because I wasn’t alone,” she replies.

While the rational response to OA’s stories is to assume that they’re fictitious, there’s imagery throughout the show that lends them weight. The wolf sweatshirt she wears when she’s shot could be construed as pointing to Veles, the Slavic god of the underworld, often imagined taking the physical form of a wolf. OA’s three names also have significance: “Nina” means dream, or dreamer, “Prairie” implies earth, and “OA,” or “original angel,” points to heaven.

The ambiguity of the final episode seems intended to reinforce the theme of the show: that we tell ourselves stories in order to live. OA’s stories are steeped in mythology that dates back millennia, and her therapeutic conversations with the FBI counsellor are no different in helping her process what happened to her than her stories in the abandoned house. The five movements (choreographed by Ryan Heffington, who’s worked with Sia on five of her recent videos) may look ridiculous to Western audiences, but they tie into a history of group movement that can be seen in the Maori haka and rainmaking rituals traditional across continents. Even the basic structure of the finale seems directly inspired by the ending of A Prayer for Owen Meany, John Irving’s 1989 novel, in which a series of rehearsed movements help prevent the mass murder of children.

For now, a conclusive interpretation of The OA might depend on whether there’s a second season. Marling herself has implied that there is one answer to take away from the show. “I would never want to deprive anyone of their interpretation of the ending,” she told Marie Claire. “The thing I will say is this: if we should be so lucky to have a season two, there are answers to all of the questions. That's the delicious thing about the gap between seasons. People watch and take it in, revel in the mystery, argue about it online. And then, if they should be so lucky, the storytellers get to meet the audience when the story continues.”

Flint's Emergency Managers Face Felony Charges Over Lead in the Water

Michigan’s attorney general on Tuesday charged four more people with crimes in connection with the Flint water crisis, including two former emergency managers appointed by Governor Rick Snyder to run the city.

Darnell Earley was the city’s state-appointed manager when Flint made the decision to switch its water source from the Detroit municipal system to the Flint River. The new water source corroded pipes, leaching lead into the water that poisoned many people in Flint. Gerald Ambrose, who was also charged Tuesday, was Earley’s successor. Schuette, a Republican, also charged the former head of the Flint public-works department and his deputy with felony false pretense and conspiracy to commit false pretense.

Earley and Ambrose are charged with felony misconduct in office, false pretense, and conspiracy to commit false pretense, two of which are felony charges that carry up to 20 years in prison. They are also charged with misdemeanor willful neglect of duty. Howard Croft and Daugherty Johnson, the public-works employees, could also face 20-year sentences.

Schuette has previously brought charges against nine people in the Flint crisis, including three low-level city bureaucrats and six state officials, but critics have complained that those charges focused too much on functionaries, letting the real authorities off the hook. Earley is the highest-profile person to face charges. He was installed as emergency manager of the city of Flint in 2013, under a controversial state law that allowed Snyder, a Republican, to hand over control of struggling cities. Flint residents have complained that the law meant that the city’s leaders were not accountable to voters. Earley left in 2015, when Snyder appointed him to manage Detroit’s schools.

Flint residents are still being advised not to drink tap water without using a filter, and many continue to use bottled water instead.

What Glenn Beck’s Full Frontal Interview Says About Samantha Bee

Glenn Beck’s recent conversion to political moderation has an almost suspiciously Dickensian quality to it. Here is a man once deemed too out-there for Fox News, who would bark right-wing conspiracy theories at his viewers every night, who now placidly preaches about the division he helped sow and says he’s very worried about the impending Trump administration. It’s an oddly dramatic turnaround. After all, Beck wrote a recent op-ed in The New York Times preaching empathy for the Black Lives Matter movement, while being credited at the bottom as the author of the book Liars: How Progressives Exploit Our Fear for Power and Control.

His appearance on Monday night’s Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, though, wasn’t just an opportunity for Beck to make another mea culpa; it was also a moment for him to try to share his new gospel of unity with a figure he saw a lot of himself in. Beck’s public change of heart might have made him 2016’s Scrooge, suddenly recanting his past cruelty, but on Full Frontal, he was like a Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, warning Bee of the dangers to come if television, including her show, becomes more polarized. Beck may be an imperfect messenger—an anchor lecturing a comedian—but he still offered a surprisingly resonant idea for the moment.

“My audience hates your guts,” Bee and Beck told each other, while clad in ridiculous Christmas sweaters. “My audience wants to kill me for normalizing a lunatic like yourself,” Bee added, receiving baleful nods from Beck, who once called Barack Obama “a racist” but more recently took that statement back and claimed that “Obama made me a better man.” To many of Bee’s viewers, Beck surely represents the kind of extreme divisiveness that helped figures like Donald Trump gain a toehold in the Republican primaries. What distinguishes him from his peers, perhaps, is his self-awareness after the fact.

“I believe you actually don’t want to do damage. As a guy who has done damage, I don’t want to do any more damage. I know what I did. I helped divide,” he told Bee, pressing the message of, “Please don’t make the mistakes I made.” Beck talked about the problems with cable television and social media in the seven-minute interview, noting that on Facebook, “We don’t see the human on the other side,” which makes it easier to attack people.

Full Frontal with Samantha Bee doesn’t come near the kind of divisiveness that Beck promoted every day on The Glenn Beck Program. For one, her show is satirical, and even her nastiest insults are presented with a comic edge. There’s a distinct and important difference between a political comedian training her fire on a target and a news anchor calling the nation’s first black president a racist. A hint of false equivalence filters through the entire segment, but what’s interesting about that is that Bee was the one inviting the comparison—it’s her show, and she’s obviously intrigued by the notion that Beck sees his “catastrophist” personality in her hosting style.

Bee’s interview with Beck said much more about her as a host than it did about his ongoing apology tour.

Bee also seems to believe in Beck’s conversion, pointing out his recent charity work for women abused by ISIS and the children of undocumented immigrants. “I’m trying to teach my audience—they’re children,” he told Bee. “Yes, you can be against illegal immigration but they’re children, and they’re here, and they’re humans.” His catastrophism remains intact, he said (his fears about Trump border on the apocalyptic), but he doesn’t want Bee to follow in his footsteps. “You’ve adopted a lot of my ... traits,” he said. “Jesus Christ,” she sighed. “Glenn Beck is gonna make me cry.”

The interview was somewhat similar in intent to Trevor Noah’s recent dialogue with the conservative-media commentator Tomi Lahren (who, it should be noted, works on Beck’s network TheBlaze)—another effort to reach across the aisle. But Noah and Lahren’s conversation was quietly combative, mostly because she’s broadcasting the extreme, often offensive positions Beck took several years ago. In their conversation, Noah was making an effort to impress Lahren with his own moderation and willingness to hear her out. On Monday, Bee demonstrated self-awareness about her own talk-show fury, having Beck on to, essentially, give a testimonial about the hazards of polarized political broadcasting.

Bee probably won’t sustain the intensity of her vitriolic style post-election—her propensity for calling Republican lawmakers “dildos” and airing her understandable anger about politics at large helped make a name for Full Frontal in its debut season. All that means for 2017 is that the battle lines have been clearly drawn, and Bee, to her credit, isn’t interested in staying behind them. Her interview with Beck said much more about her as a host than it did about his ongoing apology tour. The segment suggested there was plenty of room for one of 2016’s most exciting late-night hosts to grow as the Trump administration takes shape.

The Best Television Shows of 2016

From Catastrophe and Fleabag to High Maintenance and Insecure, The Atlantic’s writers and editors pick their favorite television shows of 2016. (For a deeper dive, there’s also a roundup of the year’s best TV episodes.)

Atlanta

Matthias Clamer / FX

It may be clichéd to say that a show is “like nothing else on TV,” but in Atlanta’s case, it’s true. When Donald Glover’s half-hour FX dramedy debuted in September, it immediately defined its own visual language (polished, meticulous), narrative style (loose, like a dream), and tone (seductive or somber, depending on the scene). The pilot feinted in the direction of a rags-to-riches hip-hop story before hitting viewers with a daisy chain of mesmerizing tangents. It delivered the year’s best experimental show-within-a-show episode (“B.A.N.”—sorry, Mr. Robot). It turned the city of Atlanta itself into a character, with its own idiosyncrasies and banalities. It went weird without cribbing from the Twin Peaks playbook—a deceptively tricky achievement—and gave pop culture the surreal gift of a Black Justin Bieber. It foregrounded the kinds of nuanced conversations and problems that almost never get airtime on prestige TV; relatedly, almost no white people appeared in front of the camera, with hilarious exceptions (“Juneteenth”). From start to finish, thanks to its vision and confidence, Atlanta had one of the best debut seasons in recent memory.

—Lenika Cruz

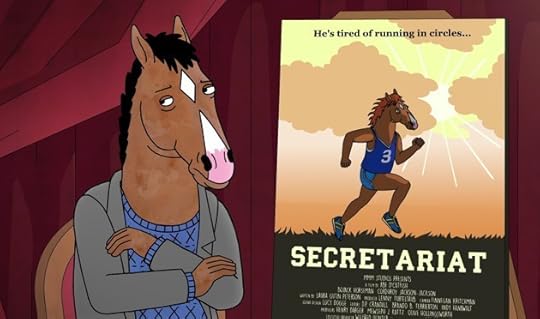

BoJack Horseman

Netflix

In its very first episodes, BoJack Horseman felt nearly indistinguishable from every other series out there about a washed-up, middle-aged celebrity. But by the middle of season one, the show’s shallow comedy turned out to be a false front. Under the kaleidoscopic animation and increasingly inventive animal puns lay a carbon-black cynicism about Hollywood, human beings, and love itself—a bleak outlook that only made the rare moments of beauty and hopefulness all the more blinding. Season three doubled down on many of the show’s serious themes (mental illness, substance abuse, grief, loneliness) while managing to be various shades of laugh-out-loud funny (vulgar, cerebral, juvenile, dark). With the help of a peerless vocal cast, this season also delivered some of BoJack’s, and 2016’s, best moments: an underwater silent film, the most unapologetically pro-choice abortion episode I’ve ever seen, and one of the year’s saddest deaths.

—Lenika Cruz

Catastrophe

Amazon Prime Video

Catastrophe has it both ways, in the best ways: It’s a rom-com that systematically mocks rom-coms. While the standard-bearers of that genre have their meet-cutes, the Amazon show presents a frenzied hookup in a hotel room. Where the typical rom-com treats children as evidence of social-Darwinian success, Catastrophe presents a new mom plagued with the fear that she might not actually love her infant daughter. Again and again, from its title on down, Catastrophe has taken the easy (and often pernicious) cliches of the rom-comic world and slyly, subtly subverted them. But! Catastrophe, too, is a rom-com; it, too, firmly believes—or, at least, firmly wants to believe—in the power of love. That desire is on display during Catastrophe’s second season, which jumps ahead several years after Series 1 took place to find Sharon and Rob still together, and still all warm and googly for each other—but also, now, navigating the needs of children and the demands of careers and the looming threat, on both sides, of infidelity. This time around, the “will they or won’t they” that will give any rom-com its defining tension isn’t a matter of “will they get together?”; instead, for Catastrophe, it’s “will they stay together?” It’s a loaded question that left me hoping, with an intensity that was mildly embarrassing considering the fictional nature of these characters, that the answer would be—could only be—“yes.”

—Megan Garber

Documentary Now!

Jordan Althaus / IFC

This niche Saturday Night Live spinoff produces six parodies of famous documentary films a year, so it’s hardly surprising that it’s never been a smash hit despite the big names attached (Seth Meyers, Bill Hader, Fred Armisen, and John Mulaney make up the writing staff). But its second season was a triumph of exacting detail and brilliant, subtle comedy. The spoof series thrived because of its obvious love for its subjects: “Juan Likes Rice and Chicken” was a heartwarming take on Jiro Dreams of Sushi; “Parker Gail’s Location Is Everything” was a paean to the work of monologist Spalding Gray, and “Final Transmission” was a live concert homage to The Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense. Each half-hour special had a perfect grasp on its singular tone, and watching the show change shape week to week was one of the biggest thrills of 2016.

—David Sims

Fleabag

Amazon Prime Video

On the face of it, an irreverent and exceedingly filthy comedy about grief might sound like a catastrophic premise for a TV miniseries, but Amazon’s Fleabag not only justified the premise, it also offered a model for what other shows might do within the same, tight, six-episode framework. Adapted by Phoebe Waller-Bridge into a BBC show from her one-woman stage play of the same name, Fleabag’s narrator is a beguilingly profane, whip-smart Londoner reeling from the accidental death of her best friend, who seeks solace in uncomfortable sexual encounters. Waller-Bridge plays Fleabag with a faux-angelic degree of lunacy that sets her apart from other car-crash heroines of modern raunch humor, and the show’s uproarious comedy is only made more affecting by the acute sadness that underpins it.

—Sophie Gilbert

The Girlfriend Experience

Starz

After a couple of years in which everyone and their mother seemed to be making a ten-hour Netflix series with elegant visuals but notable pacing problems, Starz’s The Girlfriend Experience stood out for embracing a format few modern TV shows favor: the half-hour drama. Executive produced by Steven Soderbergh, and inspired by his 2009 movie of the same name, the 13-episode series followed Christine (Riley Keough), a law student in Chicago who gets drawn into the world of high-class sex work. Keough’s enigmatic performance made Christine mesmerizing to watch: detached to an almost sociopathic extent, and attracted to her new profession in a way she can’t—or won’t— explain. Directed by Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz, the show’s compact structure, psychological complexity, and distinctive style set it apart from anything else on a streaming service this year.

—Sophie Gilbert

Halt and Catch Fire

Tina Rowden / AMC

For its third season, Halt and Catch Fire moved the action to mid-’80s Silicon Valley to explore a theme that could not have been more crucial to 2016 America: The way the internet opens new lines of communication for people around the country, while simultaneously isolating us from each other. As Donna and Cameron’s proto-social network company Mutiny hit the big time and their partnership began to disintegrate, Halt reached its greatest heights, mixing dark personal drama into a grander ballad of the tech world’s fatal flaws. Increasingly, Halt and Catch Fire feels like the worthiest successor to Mad Men in the Peak TV era—a period show about the changing fabric of American society that can turn a board meeting into some of the tensest drama on television.

—David Sims

High Maintenance

David Russell / HBO

In a year when it felt like much of the country had flipped its middle fingers toward urban America, High Maintenance offered the densest precincts a burly hug. The brilliant former web series that expanded to a half-hour HBO format uses the device of a New York City marijuana delivery guy to tour different lives unspooling in cross proximity: In one episode, a Muslim girl rebels against her parents while polyamorous drama unfolds in the apartment next door; in another, a shut-in finally gets to know his many fascinating neighbors. The HBO episodes did present the weed man with some gnarly only-in-a-metropolis setbacks, but even in its darkest moments, the show’s consistently funny, cinematically adventurous vision insisted that a thriving city is quite the opposite of an echo chamber.

—Spencer Kornhaber

Insecure

HBO

Insecure looms large in part because it appreciates the power of smallness. Adapted from Issa Rae’s web series, The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl, the HBO show revels in the minute details that twist and tangle to define people’s lives, from the clothes characters wear, to the food they eat, to the apartments and offices and other places where they spend their time. Issa, after fighting with her best friend, Molly, brings a peace offering to Molly’s door: a bag of Cheetos and a jar of dip. An early set piece finds Issa trying on different lipsticks before going out one night, each color—red, magenta, deep blue-black—suggestive of a different kind of evening. One episode revolves around the couch in Issa and her boyfriend Lawrence’s apartment; the object the show uses for that purpose, yellow and slightly lumpy and frayed in precisely the way an old and much-used couch will be, allows it to serve as a metaphor for both the security and the anxiety of long-term relationships. Insecure doesn’t elevate the mundane details of life so much as it simply celebrates them, as they are, in all their glorious banality. It sweats the small stuff—and, even and especially on the small screen, that’s a rare, and very big, thing.

—Megan Garber

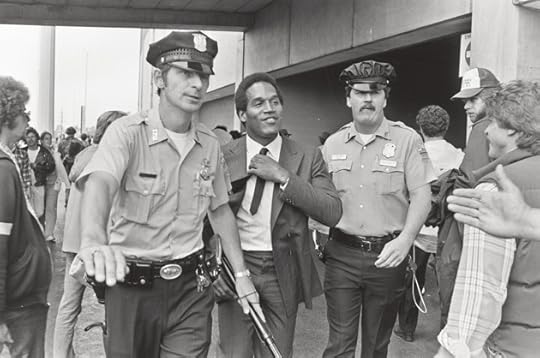

The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

Ray Mickshaw / FX

The arc of history is long, but it bends towards being packaged by Hollywood into snackable narratives that erase complexity. Yet Ryan Murphy’s The People v. O.J. Simpson miraculously ended up paying tribute to reality’s mess. Sure, the show had a point of view, positing that long-brewing racial resentment explained a verdict that left much of the country flabbergasted— strong theory that reverberated in strange ways after November’s electoral surprise. But as it unfolded a story most viewers remember well, it avoided calling out heroes and villains, giving an all-angles view that stretched from the jury box to the street corner to (even) Kim Kardashian’s childhood bedroom. In doing so, it also restored a bit of credibility and grace to the medium that the Simpson trial helped lend a trashy reputation to: television itself.

—Spencer Kornhaber

And, Scene: Hail, Caesar!

Over the next two weeks, The Atlantic will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy moment—whether a bank robbery gone wrong or a history-changing phone call—and unpacking what it says about 2016. First up is the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar! (The whole “And, Scene” series will appear here.)

It might have been because of its early release date (February 1), or its airy, vignette-heavy plot, but when it came out Hail, Caesar! was dismissed by many as a minor Coen Brothers comedy—a satire of Hollywood’s “Golden Age” of moviemaking that felt largely trapped in amber. But its veneration of vintage pop art turned out to have one foot in the present, reminding viewers that all art is political, no matter how milquetoast the branding might be.

The film’s ostensible storyline saw studio executive Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin) shepherding the production of an epic period drama with the same title, an obvious homage to 1959’s Ben-Hur. In one scene, Mannix gathers four religious leaders—a Protestant minister, a Greek Orthodox patriarch, a Catholic priest, and a Jewish rabbi—to consult them on his film’s portrayal of Christ. “We don’t want to send it to market except in the certainty that it will not offend any reasonable American regardless of faith or creed,” he intones.

It’s a silly goal, one that could succeed only if the film in question is presented as blandly as possible. Still, even the biggest, most mainstream films regularly lead to outrage, as 2016 proved again and again: The all-female casting of Ghostbusters prompted a wave of sexist backlash from critics who had yet to see the movie, and Rogue One sparked a debate over whether its story was meant to be a commentary on the presidential election.

The Hail, Caesar! scene quickly ramps up into a theological argument, underlining the absurdity of Mannix’s goal. Immediately, the debate extends beyond the fictional film’s merits and into the nature of Jesus himself. The priest notes that Christ is not God, nor God Christ. “You can say that again! The Nazarene was not God!” the rabbi interjects. “He was not not God,” the patriarch replies. “Part God!” the minister argues. The dialogue bounces around faster and faster as Eddie’s brow furrows: “There is unity in division ... and division in unity,” the priest and the patriarch yell at each other in an exchange that could practically serve as a slogan for the last year in American culture.

Mannix seems genuinely invested in trying to chart a middle way for his studio’s film, but in the end, he can take satisfaction only in having not obviously offended anyone further. “I haven’t an opinion,” the rabbi ultimately demurs when asked if the film bothered him; after all the angry debate, it’s the perfect laugh-line to end on. The meta-joke, of course, is that much as in Ben-Hur, Hail, Caesar! only depicts Jesus fleetingly, and with no personality outside of a general holy glow. The idea that anyone could be offended is as ridiculous as it is sadly plausible.

Hail, Caesar! is loaded with funny, disconnected scenes like this one, including an actor-director showdown over the line “Would that it were so simple” and a stupendous, innuendo-laden musical number starring Channing Tatum. In each one, Mannix is tinkering around in the background, keeping the gears of the Hollywood machine well-oiled. In the film’s climactic moment, Hail, Caesar!’s star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) declares to Mannix that he’s converted to Communism, ranting about the evils of the capitalist machine providing yet another opiate for the masses. He receives a vigorous slap for his troubles, with Mannix barking at him about the importance of what they do. “The picture has worth, and you have worth if you serve the picture!” he yells.

In making a satire of 1950s Hollywood, the Coen Brothers struck on the inherently ridiculous dichotomy at the heart of all mass-market entertainment: the simultaneous pointlessness and deep value of pop culture, impressive in its ability to reach the lowest common denominator if nothing else. So much has changed in the intervening decades (indeed, this year’s edition of Ben-Hur was pitched right at Christian audiences and was hardly a hit), but the general thrust of the Coens’ argument remains the same. The picture has worth, no matter how trivial it might seem, and in 2016 there was no piece of pop culture that wasn’t primed to become a battleground under the right circumstances.

Next Up: Mountains May Depart

December 19, 2016

The Best Movies of 2016

Like the last couple of years (and in contrast to 2013), 2016 was light on great films but offered a solid share of good ones—so many, in fact, that I’ve considerably expanded my list of honorable mentions. As always, my favorites are somewhat eclectic and the individual awards that follow more eclectic still. And I should again caveat the entire enterprise with the note that, while I saw a great many films this year there are still quite a few of the more than 700 movies released domestically that I missed. If a favorite of yours goes unmentioned that may be why. And with that…

1. Arrival

Paramount

At once epic and intimate, director Denis Villeneuve’s film accomplishes what science fiction cinema often strives for by rarely achieves: It makes us think and feel in equal measure.

2. La La Land

Lionsgate / Summit Entertainment

Damien Chazelle revitalizes the movie musical with a film that is just shy of a masterpiece. Keep an eye on the door beneath the “window from Casablanca” for the movie’s most important cinematic reference.

3. Manchester by the Sea

Roadside Attractions

Pitch perfect from first frame to last, Kenneth Lonergan’s portrait of working-class New England is sensitive but unsentimental. The long-underrated Casey Affleck delivers the performance of his career to date.

4. Hell or High Water

CBS Films

A magnificent neo-Western that understatedly captures the current economic moment and features powerful performances all around—in particular by Jeff Bridges.

5. The Lobster

A24

A stunning exercise in dystopian absurdism and pitch-black comedy. The English-language debut of Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos offers a precise and novelistic metaphor for love and couplehood.

6 . Moonlight

A24

Tender and meticulously observed, Barry Jenkins’s film is a marvel of intimate portraiture. Mahershala Ali dazzles in a supporting role.

7. The Handmaiden

Amazon Studios / Magnolia Pictures

Director Park Chan-wook’s elegant story of lust and betrayal in Japanese-occupied Korea holds back at first before gradually allowing its perversion and depravity to rise to the surface.

8. Zootopia

Disney

Seamless noir mystery, moral fable and, yes, Disney animal cartoon, Zootopia is the best animated film of the year.

9. O.J.: Made in America

ESPN Films

Television series? Feature film? Ezra Edelman’s documentary may defy easy categorization, but its brilliance is beyond dispute.

10. Loving

Focus Feautures

Featuring an extraordinary performance by Ruth Negga, Jeff Nichols’s film about the marriage that led to Loving vs. Virginia movingly captures the trope that the personal is political.

11. Hail, Caesar!

Alison Rosa / Universal

A sharp, underrated offering from the Coens, and arguably their most compassionate film to date.

12. Sing Street

The Weinstein Company

A lesser cousin of John Carney’s great Once, this Dublin-based musical charmer about a teen boy and his 1980s-era band is one of the year’s genuine delights.

Honorable Mentions:

The Birth of a Nation; Captain America: Civil War; Don’t Think Twice; Elle; Elvis & Nixon; Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them; Fences; God Knows Where I Am; Green Room; Hacksaw Ridge; The Jungle Book; Kubo and the Two Strings; Life, Animated; Love & Friendship; Moana; A Monster Calls; The Nice Guys; Operation Avalanche; Rogue One: A Star Wars Story; Tallulah; 10 Cloverfield Lane; Weiner; The Witch

And the Rest…

Best Use of a Song: Tommy James and the Shondells’ “I Think We’re Alone Now,” played in an underground bunker after a presumed extinction-level event, 10 Cloverfield Lane

Worst Use of a Song: Harry Nilsson’s “Can’t Live,” as special forces kill a group of terrorist insurgents, Whiskey Tango Foxtrot

The Please Don’t Use “Fortunate Son” in Another Motion Picture Ever Again Award: (tie) Suicide Squad, War Dogs

The “Girl in the Title” Award for Novel-Based Thriller that Most Needed to Be Directed by David Fincher: The Girl on the Train

The “Seven Pounds” Award for Ugly, Cynical Will Smith Vehicle Posing as an Uplifting Holiday Charmer: Collateral Beauty

Longest Expository Voiceover: J.K Simmons, The Accountant

Most Overrated Female Performance: Natalie Portman, Jackie

Most Underrated Female Performance: Amy Adams, Arrival

The Mel Gibson Award for Blood-Drenched Christian Pacifism: Hacksaw Ridge

Scariest Dogs:

Green Room

Scariest Goat:

The Witch

The Bobby Ewing Award for Lamest Misleading Dream Sequence: Hacksaw Ridge

Runner-up: Sully

Second runner-up: Sully, again

Meanest Mother: Isabelle Huppert, Elle

Meanest Daughter: Isabelle Huppert, Elle

Best Septopus:

Finding Dory

Best Heptapod:

Arrival

Best Ursine Mobsters:

Zootopia

Worst Ursine Mobsters:

Sing

Best Video Brochure for Florence: Inferno

The Third Actor to Play a Superhero in 10 Years Award: Tom Holland (Spiderman), Captain America: Civil War

The Fifth Actor to Play a Superhero in 25 Years Award: Ben Affleck (Batman), Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice

The Chronic Misuse of Voiceover Award: Knight of Cups

Best Elephants:

The Jungle Book

Best Coconuts:

Moana

Greatest Mileage Out of a Single Line of Dialogue: “Would that it were so simple,” Hail, Caesar!

Best Hollywood Inside Joke: Isla Fisher Playing a Fictionalized Version of Amy Adams, Nocturnal Animals

Worst Hollywood Inside Joke: “Jack Ryan and Jack Reacher—tonight’s going to be a total jack-off!” Zoolander 2

The Arrested Development “I Blue Myself” Award for Body Painting: Tom Hiddleston, High-Rise

Film That Most Completely Vanished From Memory: Jason Bourne

Best Villainous Jemaine Clement Vocal Performance: Tamatoa, Moana

Runner-up: Fleshlumpeater, The BFG

Best Cover of A-ha’s “Take On Me”: The acoustic piano solo in Sing Street

Worst Cover of A-ha’s “Take on Me”: Sebastian’s ’80s band in La La Land

The Liam Neeson Award for Fearsome Father Figures: A Monster Calls

Best Argument Against Prepared Meats: Sausage Party

Best Villain in a Terrible DC Comics Movie: Margot Robbie (Harley Quinn), Suicide Squad

Worst Villain in a Terrible DC Comics Movie: Jesse Eisenberg (Lex Luthor) Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice

Film with the Most Awful Real-Life Sequel: Weiner

Best Homoerotic Dance Number:

Hail, Caesar!

Best Seasonal Sex Montage:

Deadpool

Worst Hot-Tub Experience: The Lobster

Worst Diner Experience: The Lobster

Best Film About an Evil Conspiracy to Produce Tickle-Fetish Films: Tickled

Best Fix of a 50-Year-Old Bad Ending: The Jungle Book

Best Brooklyn-Queens Bonding: Captain America: Civil War

Best Limited Use of Laura Linney:

Nocturnal Animals

Worst Limited Use of Laura Linney:

Sully

The William Tell Award for Two Innocents Accidentally Killed with a Single Arrow: X-Men: Apocalypse

Worst Box Office: Pet, $70

Runner-up: Satanic, $252

The “You’re Lucky My Mother Was Named Martha” Award: Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice

Worst attempted reboot:

Blair Witch

Runner-up:

The Magnificent Seven

Fastest Evolution from Widely Anticipated to Intensely Argued Over to Largely Forgotten: Ghostbusters

Least Promising Franchise Arc: Dan Brown / Robert Langdon films (The Da Vinci Code: $217 million; Angels & Demons: $133 million; Inferno: $34 million)

The “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex” Award: “I just don’t know if it’s possible for you to love me,” Lois Lane, Batman v Superman

Worst Spy: Brad Pitt, Allied

Best Triple Cross: Kim Min-hee, The Handmaiden

Saddest Posthumous Appearance: Garry Shandling as the porcupine in The Jungle Book

Creepiest Posthumous Appearance: Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin in Rogue One

Best Unintentionally Self-Critiquing Quote: “Needless to say, the whole thing was a bad idea,” Suicide Squad

Runner-up: “You should shut it down,” Suicide Squad

The Frank Welker Award for Voice Work Omnipresence: Alan Tudyk (Zootopia, Moana, Rogue One)

Breakthrough Performances (Grownup Division): Mahershala Ali (Moonlight), Tom Bennett (Love & Friendship), Alden Ehrenreich (Hail, Caesar!), Ruth Negga (Loving), Alison Sudol (Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them).

Breakthrough Performances (Young ’Uns Division): Michael Barbieri (Little Men), Lucas Hedges (Manchester by the Sea), Lewis MacDougall (A Monster Calls), Angourie Rice (The Nice Guys), Anya Taylor-Joy (The Witch).

(Previous Best Movies Lists: 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2009, 2008, 2007)

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower