Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 34

December 13, 2016

The Best Albums of 2016

A year of surprising headlines was accompanied by a year of surprising music, one that saw the trend of “event releases” escalate. Instead of albums merely dropping without warning as they have in the last few years, now we get mysterious HBO premieres, or days-long webcast construction projects, or arena fashion shows. We get albums revised after they’ve been released; we get albums whose existence was possibly a secret even to the creator’s record label. More than one venerated icon released a landmark set of songs and died shortly after. Another had his voice, sounding as vibrant as ever, show up from beyond the grave.

Presuming to declare the best and worst of these, by some universal standard, is a losing game—these are just my personal 10 favorite releases from the past year.

1. Frank Ocean, Blond(e)

Frank Ocean

In Westworld—just one of the year’s many cultural products indicting the limits of mankind’s empathy—artificially intelligent robots recall their memories in perfect clarity, which means they have a hard time distinguishing between what’s happened to them and what’s happening to them. It’s one of the ways the machines feel alien: For us humans, the past lives on not as HD video but as a collection of waterlogged cassettes. For us humans, memories abstract themselves into big life lessons, or they harden into hyper-specific scenes, or they rearrange themselves by a logic other than chronology.

Frank Ocean has approximated the mess of human memory on the staggering Blond(e), an album that represents a rebellion against record labels and against spelling but more than anything against musical convention. To nail the beauty and ache and confusion of combing through one’s own past, he liquified genre barriers, recorded his voice with a variety of distorting techniques, treated the entire concept of rhythm as optional, and ditched the pop directive to simplify life experiences into relatable, salable units. The results are intuitively moving and intellectually confounding: You’re mesmerized, then annoyed, then mesmerized, then crying, then crying, then hyped up, then crying, and so on.

It’s the kind of album that teaches you how to listen to it, and the ultimate lesson is simply about the person who made it. Ocean is vulnerable, perceptive, and arrogant at once. He’s trying to live up to certain ideals of purity, but cars and drugs and flesh still have their allure. And he’s left behind a lot of constraints—the most famous of them heteronormativity—but hasn’t solved the problem of human connection: “Wish we’d grown up on the same advice,” he says to some lover on “Self Control,” maybe the most heartbreaking line on a generally heartbreaking album. Entirely bridging the gulf between one person’s mind and another’s remains impossible, but it’s still the job of art’s great innovators to propose new ways to approach the task. That’s what Ocean has done.

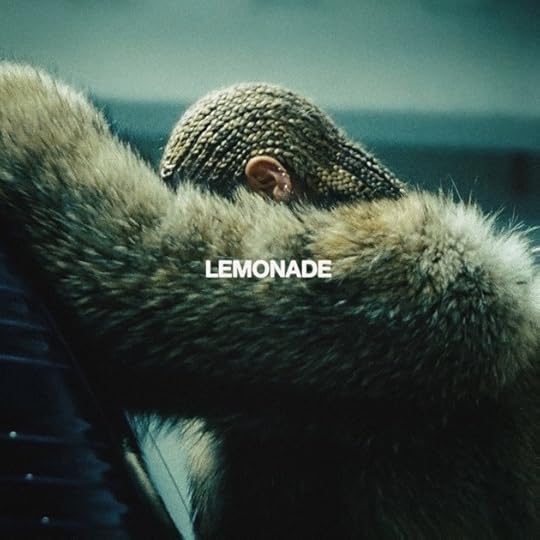

2. Beyoncé, Lemonade

Columbia / Parkwood

The Lemonade era saw Beyoncé cement her credibility as social critic, political symbol, film director, businesswoman, publicity master, and possessor of Serena Williams’s phone number, but every achievement has been built on the unshakeable foundation of her brilliance as an entertainer. Her knack for locating the sound, the statement, and the aesthetic swerve that will be most fascinating for any given moment—and will remain fascinating on the strength of execution—has only grown stronger over the course of her career.

Which explains why Lemonade, even when considered separately from the many conversations it has inspired, is a thrill from front to back. These songs open up mysteries and slowly solve them, revel in cliffhangers and twists, and betray the same eye for stylistic juxtaposition that a veteran fashion-magazine editor might have. When Beyoncé tackles a new sound—rock on “Don’t Hurt Yourself,” country on “Daddy Lessons,” spiritually drained dance-floor assassin on “Sorry”—she commits entirely. And if haters want to level accusations of self-seriousness, the pop idol most associated with professionalism and control answers with moments of giddy, rude humanity: “Suck on my balls, pause!”

Then there’s the content itself, so layered with relevance as to keep her omnipresent in the cultural conversation, from the Super Bowl “Formation” debut till now. A near-mythic story cycle gives new vibrancy to the theme of infidelity, further supercharged with intrigue by Beyoncé appearing to air out her very-public marriage. The accompanying film deftly connects that personal struggle to a social one, honoring black female resilience in the face of generations of disrespect. The message came at the right time: Solange, Jamila Woods, and others have since released strong albums carrying on not only Lemonade’s themes but also Lemonade’s insight that to change lives with music, you need music that people want to live with.

3. Leonard Cohen, You Want It Darker

Columbia

One of the advantages Leonard Cohen always maintained over his many mordant male imitators was a voice that became only more distinct with age. The spare, unflinching You Want It Darker uses that instrument to its most extreme purpose; after 82 years, Cohen’s singing seemed to scrape against the very floor of the human hearing range, commanding attention for his deadpan indictments of the universe. It’s been a good time to listen. Released weeks before his death, in a year filled with unsettling events, Cohen’s final songs offer weary comfort: If things are bad, he always counseled, that’s generally the will of God.

4. Mitski, Puberty 2

Dead Oceans

“You're the sun, you've never seen the night / But you hear its song from the morning birds,” Mitski sings about a boyfriend too secure in his own skin, too encased in privilege, to ever really relate to her. I bring this up not to use the word “privilege” one more time in 2016 but because the line is a perfect bit of poetry, no? On her fourth album, the rising rocker Mitski Miyawaki proved her talent at every level of crafting sad/smart singalongs: Jagged noise often cuts through the mix, but the musical hooks are sharper, and the words even more so.

5. A Tribe Called Quest, We Got It From Here... Thank You 4 Your Service

Epic

“The world is crazy and I cannot sleep,” Q-Tip says, “But melatonin good enough to eat.” I’ve lately thought a lot about that line, the kind of relatable detail that deepens Tribe’s ever-pulsing, shape-shifting We Got It From Here: Even legendary rappers, it turns out, have news-related insomnia these days. Tip, the late Phife Dawg, and Jarobi White were snuggly plugged into the political moment while they recorded their comeback-and-farewell release, and while the results describe plenty of dread and discord, the music’s warm, irrepressible sound rejects the possibility of defeat. Take natural sleep supplements so as to fight another day.

6. Chance the Rapper, Coloring Book

Chance the Rapper

Chance the Rapper has done what a musical superstar in the making needs to do: Offer something new and irresistible. That something is sly and smart inspirational music, rooted both in Christianity and secular reality, in dialogue with the wider pop culture world but also implicitly critical of it. Equally clever whether addressing Harry Potter or overpolicing, boasting a singular and humane voice, Chance’s music pushes ahead while also accomplishing the vital job of making the listener feel, deep down, safe.

7. Lambchop, FLOTUS

Merge

Bon Iver was neither this year’s only nor best indie-folk dude reinventing his sound by running his voice through machines. Kurt Wagner of the veteran alt-country act Lambchop, inspired by hip-hop’s innovative disinterest in sounding “natural,” bought a TC-Helicon Voicelive 2 and created a supremely chill set of songs embracing the potential of singing beyond the constraints of vocal cords. The title came partly from a meditation on husbands and wives, colored by the notion that America’s next FLOTUS could have been male. After the election, the name’s other meaning—For Love Often Turns Us Still—retains its resonance, as impressionistic and gentle as the music itself.

8. David Bowie, Blackstar

Columbia

David Bowie’s final album, as far as I can tell, is about attention: the black star of ego commanding certain special people to live lives that attract the eyes of the masses. It’s a subject Bowie obviously knew a lot about. “I’m dying to push their backs against the grain / And fool them all again and again,” he explained on “Dollar Days,” a relatively straightforward acoustic reverie amid a set of trembling, gorgeous jazz odysseys. On its own, Blackstar reinvented his sound to inspire wonder and obsession. Then, three days after the album’s release, his death raised a new question: Did he plan for this to be his finale? The mystery will hold our attention forever.

9. Weval, Weval

Kompakt

It may not sound like a compliment to say that the Dutch electronica duo Weval seems destined to soundtrack really great car commercials and dark dystopian HBO title sequences. But any batch of perfectly executed atmospheric dance music is life-improving stuff; you might as well hope for it to get popular. If in need of some drama with your daily routine, these sleek soundscapes with snatches of heavy-lidded vocals do the trick. But the real fun is in listening closely to, and marveling at, Weval’s craftsmanship. No two measures are exactly the same, the melodies draw memorable shapes, and the rhythms approach and recede in the ear—all part of a very successful effort to engage the listener’s brain and level out their mood.

10. Kamaiyah, A Good Night in the Ghetto

Kamaiyah

In a year when the rap world had playfulness to spare thanks to the apparent influence of nursery rhyme (see: Lil Yachty, and no I’m not criticizing), the Oakland newcomer Kamaiyah’s debut collection of feel-good hip-hop still stood out. With terse and funny punchlines, choruses of sing-songy taunts, and echoes of G-funk, she offered escapism while telling stories about thriving in a tough environment. Fun biographical fact No. 1: As she memorably informs her rivals, her name rhymes with “please reti-yah.”

What Is America’s Next Top Model Without Tyra Banks?

The host of a reality competition is often a hybrid creature: a judge, a coach, a friend, a foe, an imparter of lessons, a decider of fates. No host, however, has played so many roles for her particular show as Tyra Banks has played for America’s Next Top Model—for which she has served not only as presenter, but also as creator and executive producer, as first mover and final force. Top Model, the Tyra Banks Show even before there was an actual Tyra Banks Show, has been infused with the supermodel at every level. Photos of her have decorated the rooms that have housed the contestants during their time on the show. Challenge winners have been rewarded for their successes with stays in the (similarly Banks-bedecked) “Tyra Suite.” Models have received communiques in the form of “Tyra Mail,” and have found themselves on the receiving end of “Ty-Ty tips.” They have used “fierce” as a noun. They have lived in—and invited the rest of us to enter—a Tyracentric universe.

Top Model, after 12 years and 22 seasons (or “cycles,” in the show’s fanciful parlance), was canceled in 2015; in February of this year, VH1, which had long served as a home for its reruns, announced that it had acquired the show—and that it would resurrect the series with one notable change: Banks would no longer be the show’s host. Instead, Top Model would be presented by Rita Ora, the singer/actor/model/personality/brand. It was a shakeup that would put Top Model’s distinctive physics to the test: Could the show continue intact, even without its center of gravity? Could Top Model keep on spinning, even without Tyra acting as its axis?

Monday evening brought both the show’s return and a tentative answer: Yes, Top Model lives on, and distinctly Top Model-y. And that’s because the version of the show that is not hosted by Tyra looks, it turns out, so much like the show that was hosted by her. Banks remains, for one thing, Top Model’s executive producer, but she is not, for the moment, merely a behind-the-scenes presence; on Monday’s show, she made an entrance even before Ora did—first via a video, a montage of Tyra-isms (“FIERCE,” “BYOB—BE YOUR OWN BOSS”), and then in person, where she and the contestants carried out the traditional starting-the-cycle ceremony that has been practiced since Top Model’s premiere: Tyra appeared on a stage, at which point the gathered girls screamed and cheered and generally lost their minds.

What started as a show about modeling one’s body has become a show about modeling one’s brand.

“Do you understand where the modeling industry is right now?” Tyra asked them, as they tried and failed to calm themselves. “I’m not looking for a traditional model, and I’m not looking for a social media model. I’m looking for both.”

She reiterated that idea, using herself—coach, judge—as the example to emulate: “A personal brand is so important, and I really worked my entire career to make sure that I could be in control of my destiny and my own boss. That I was about beauty, business, and badassery, not just a pretty picture.”

But it wasn’t just Tyra who stressed all the dimensions that Top Model professes to highlight. When Ora, and then her fellow judge-coaches—the supermodel Ashley Graham, the stylist Law Roach, and Paper magazine’s creative director, Drew Elliott—made their appearances, the quartet discussed, with the stilted spontaneity of unscripted TV, the new Top Model regime.

“This competition is revamped,” Ora announced, to her fellow judges and to the show’s audience. “What I hope the girls learn is how to be a 25-year old boss.”

She continued, a few moments after that: “As you know, we’re looking for the model with the triple B: business, boss, and brand.”

Graham agreed, echoing Banks’s decree: “It’s not just about a pretty face anymore.”

This was all extremely heavy-handed, but with good reason. Top Model, when it appeared in 2003, came with a built-in challenge: to be at once about modeling and also about so much more than modeling. The series claimed, like so many of its fellow skills-based reality series, to be about the work that goes into the illusion—“I want to take someone from obscurity to fame,” Tyra told her audience in the show’s premiere, “and I want to chart the entire process and show America how it happens”—but it was also, unavoidably, about finding a girl who was visually striking. The show, especially since it coincided with a moment in which feminist blogs were ascendant, and during which the rise of social media meant that critics suddenly had platforms for their criticisms, needed to figure out how to navigate its own internal pitfalls, to celebrate the superficial without also celebrating superficiality itself.

Related Story

The Tyra Banks Matriarchy: A Scholar's Take on America's Next Top Model

It took time for the show to strike that balance. In the beginning, there were makeovers (Tyra unilaterally deciding to lop off a girl’s long hair, or to dye another’s black) and, in the very beginning, bikini waxes. Some girls cried. Some girls left, breaking under the pressure. Judges were blunt in their assessments of contestants’ appearances; they were so blunt, sometimes, that they verged on cruelty. Top Model, at first, justified a lot under the logic that in modeling, the industry that is also an attitude, the superficial is the substance.

But its decade-plus on the air found Top Model reconciling, sometimes slightly desperately, with its own central conflict: The show moved farther away from the find-a-pretty-person premise, and toward a more holistic examination of the fashion industry. It experimented with gimmicks, including “Guys and Girls” versions of the show and a “British Invasion” (veterans of the British version of Top Model competing against American novices); it periodically swapped judges and coaches. It added “social media scores” to its assessments of its models, and gave viewers, in the vague manner of American Idol, the ability to help determine those assessments. Toward the very end, in cycle 22, Top Model removed its controversial height requirement—opening the door for models who might not be of runway height, but who would be effective for, say, social media campaigns.

So Top Model, cycle after cycle, has undergone its own makeover: What started as a show about modeling one’s body has become a show about modeling one’s brand. And the new, Ora-cular version of the show—business, boss, and brand—continues that emphasis, and doubles down on it. “The model of today,” Ora reiterated to her fellow judge-coaches, “has to be able to be a boss, has to be able to act, move, have a following.” She paused. “We’re gonna find a star, you guys!”

Her excited comment represented a full-circling: In Top Model’s first episode, too, Tyra had declared, “What I’m looking for is a star. That’s all.” And, in that, it suggested all that has not changed within a show that has been on the air for decades and spawned so many imitators: namely, Tyra herself. As she told the contestants who had gathered in New York to re-make themselves in her image, at the start of the show she technically is no longer hosting: “I won’t be here. But I will be watching you.”

December 12, 2016

The Electoral College Is John Podesta's Last Hope

John Podesta, the chairman of the Hillary Clinton campaign, is famously fascinated with UFOs. In the days when Clinton looked like the next president, alien conspiracy theorists hoped he’d be able to push for the disclosure of state secrets about extraterrestrial visitors.

But Clinton lost, and now Podesta is left to press for more mundane disclosures. On Monday, a group of 10 presidential electors led by Christine Pelosi, the daughter of House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi, demanded to be briefed on Russian hacking into the election. The CIA and other U.S. intelligence agencies have concluded that Russian agents were interfering with the election, and the CIA now believes the goal was to aid Trump. The electors write:

The Electors require to know from the intelligence community whether there are ongoing investigations into ties between Donald Trump, his campaign or associates, and Russian government interference in the election, the scope of those investigations, how far those investigations may have reached, and who was involved in those investigations. We further require a briefing on all investigative findings, as these matters directly impact the core factors in our deliberations of whether Mr. Trump is fit to serve as President of the United States.

They write that this is a bipartisan demand, though that’s somewhat misleading: Chris Suprun, the lone Republican to sign, has already said he will not vote for Trump.

Later on Monday, Podesta issued a statement backing the electors. “The bipartisan electors' letter raises very grave issues involving our national security. Electors have a solemn responsibility under the Constitution and we support their efforts to have their questions addressed. Podesta also goes on to decry a lack of media attention during the campaign to the prospect of Russian interference (a subjective call, and one that’s open to argument) and calls for further investigation and disclosure to the public (reasonable).

It’s the support for briefing the electors that sticks out. What is it that entitles electors to a briefing on classified material that other citizens cannot view? Electors don’t really have any particular qualifications in intelligence; for the most part, they are simply politically active people chosen by their state parties, or sometimes they are elected. In any case, they’re not elected to assess intelligence. They are elected for one purpose, which is to vote for whomever their state’s voters select. That points to a second question: What would the electors going to do with whatever information they glean from such a briefing?

The answer is unlikely to make anyone feel good. Even in the extremely unlikely scenario that enough electors decided to flip their votes to Clinton and hand her the presidency, the ensuing political and constitutional crisis would be brutal, even if one believes a Trump presidency will also produce a political and constitutional crisis.

Democrats are understandably upset about an election in which, for the second time in five elections, their candidate won the popular vote and lost the electoral vote. There are some people who believe that the Electoral College ought to be abolished, a legitimate political goal. But the electors’ letter, and Podesta’s just-asking-questions endorsement of it, seems to be geared toward changing the rules in the middle of the game, in the hopes of convincing electors to change their votes in defiance of the intentions of voters as expressed in the existing system, and sometimes in defiance of laws that bind them.

The public deserves to know as much as it can about any interference in elections without endangering national security. But why should should electors learn that separately?

Teen Vogue’s Political Coverage Isn’t Surprising

On Saturday morning, Teen Vogue published an op-ed by Lauren Duca titled “Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America.” The tone and message of the piece, which compared the ways in which the president-elect talks about his record to the ways abusive spouses psychologically manipulate their partners, struck a notable chord with readers on social media, garnering almost 30,000 retweets from Teen Vogue’s account, and getting shared by personalities from Patton Oswalt to Dan Rather. Many people tweeting the story did so with an incredulous tone, seeming surprised that a teen-oriented magazine was publishing incisive political coverage rather than makeup tutorials or One Direction interviews.

.@teenvogue may be an unlikely source for a detailed look at "Gaslighting" + Donald Trump, but there you have it...https://t.co/mgh534J8AG

— Dan Rather (@DanRather) December 11, 2016

Did not expect this exegesis of gaslighting and its relationship to current day politics from Teen Vogue https://t.co/cwNhZ6wvJH

— David Folkenflik (@davidfolkenflik) December 10, 2016

But the tone of Duca’s piece was representative of a larger shift Teen Vogue has made over the last year. In May, 29-year-old Elaine Welteroth took over as editor from Amy Astley, who helped found the magazine in 2003. Welteroth, the digital editorial director Phillip Picardi, and the creative director Marie Suter have moved the magazine more aggressively into covering politics, feminism, identity, and activism. Together, the three have shepherded a range of timely, newsy stories, including an interview exploring what it’s like to be a Muslim woman facing a Trump presidency, a list of reasons why Mike Pence’s record on women’s rights and LGBTQ rights should trouble readers, and a video in which two Native American teenagers from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe discuss the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

The pivot in editorial strategy has drawn praise on social media, with some writers commenting that Teen Vogue is doing a better job of covering important stories in 2016 than legacy news publications. But the move is also an intelligent one from a business perspective. Teenagers who’ve grown up on the internet are as likely to be informed about social issues as their parents are, and just as eager to read and share stories that reflect their concerns about the world. While some casual observers might seem surprised that a teen fashion magazine is focused on racism and sexism rather than on “hairstyles and celebrity gossip,” their assumptions dismiss how attentive young readers are to politics—an interest Teen Vogue is astutely capitalizing on.

Teen Vogue was founded in 2003 at the behest of Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Anna Wintour, who tasked Astley, the magazine’s beauty editor at the time, to conceive test issues of a spinoff publication for teens. The publication’s early focus was fashion. “We are going to do what we do well, which is fashion, beauty, and style,” Astley told The New York Times’s David Carr shortly before its launch. “A lot of other teen magazines are focused on relationships, boys, sex, and embarrassing moments. That is not our equity.”

At the time, Carr noted, many rival teen publications were struggling. And since Teen Vogue debuted, a number of them—Elle Girl, Cosmo Teen, Teen People, Teen—have folded. One of the challenges is that teen audiences tend to evolve faster than the adults catering to them can catch up. “It’s always been such a volatile market because your audience morphs so rapidly,” John Harrington, a publishing consultant, told The Times in 2013. The genius of the current iteration of Teen Vogue is that it’s caught on to its current readers’ enthusiasm for topical issues in a timely enough fashion to actually engage them.

“I think in 2016 we found our footing and our voice as a publication in a strong way,” Picardi, the publication’s digital editorial director, told me via email. “Obviously, the election has provided unique circumstances and a real need for someone to dissect the news for young people. Since we are, in particular, a brand that speaks directly to millions of young women, we have a responsibility to do right by them and view the news through that very specific lens.”

The September issue featured a personal essay by Hillary Clinton, a conversation between Amandla Stenberg and Gloria Steinem, and an interview with Loretta Lynch.

Teen Vogue’s two strongest traffic days in 2016, Picardi says, were November 9, the day following the election, and Sunday, as Duca’s piece about Trump picked up steam. (The publication’s traffic is up 208 percent over the last 18 months; it reached 9.4 million uniques in November.) But he notes that the publication’s coverage of politics is of a piece with its coverage of fashion, beauty, and entertainment. Its top five most-read pieces of the year speak to the myriad subjects Teen Vogue covers, as well as the diverse interests of teen girls:

1. Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America

2. How to Apply Glitter Nail Polish the Right Way

3. Netflix Arrivals October 2016: See the Full List

4. Mike Pence’s Record on Reproductive and LGBTQ Rights Is Seriously Concerning

5. Dark Marks and Acne Scars: Your Complete Guide

In engaging with social issues, though, the magazine isn’t breaking entirely new ground. On Sunday, Tavi Gevinson, the editor of Rookie, appeared to acknowledge other publications’ debt to the magazine she founded at the age of 15. “Why should it be shocking that mainstream pubs reckoning w/ accountability culture & the rising currency of feminism are suddenly feminist?” she tweeted. (Gevinson was on the cover of the September issue of Teen Vogue, in a shoot styled by the longtime Vogue creative director Grace Coddington.) Later, she followed up with a lengthier statement:

Good will can and does coexist with wanting to make profit. I am saying that as the cultural currency/relevance of feminism goes up, confusing fiscal interest with moral interest and keeping our expectations of mainstream women’s mags so low will make us more and more likely to confuse magazines doing what they need in order to stay relevant, with advancing the cause of feminism. Media literacy is more important now than ever, and we should never stop asking ourselves, after everything one reads, “how does it benefit this publication to post this?” this is an exciting moment in which places with lots of money and reach—in many industries: publishing, film, TV, art, etc.—have finally understood that women and teens do not, in fact, want to see stuff that makes them hate themselves. What a relief! But I would be remiss not to enjoy it all with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Rookie was launched in 2011 as a deliberate counterforce to much of the existing journalism for teenage girls. In creating Rookie, Gevinson—whose ability to connect with her peers and whimsical approach to clothing drew both praise and irritation within the fashion world—aimed to respect “a kind of intelligence in the readers that right now a lot of writing about teenage girls doesn’t.” Over the past five years, Rookie has published work by writers including Sady Doyle, Amy Rose Spiegel, and Jenny Zhang, in themed issues covering topics from “Action” to “Work” to “Consumption” to “Invention.” But while traffic to rookiemag.com has declined recently, with Gevinson pursuing other acting and music opportunities, Teen Vogue’s has been steadily climbing. This fall, Condé Nast announced its print magazine would be reduced to four issues a year, with the publication focusing more on digital readers.

Teen Vogue’s recent September issue, typically the month in which fashion magazines focus on upcoming trends, was noteworthy for its politically oriented content. It featured a personal essay by the presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, a conversation between the actor Amandla Stenberg with the feminist Gloria Steinem, and an interview with the U.S. attorney general Loretta Lynch, conducted by the black-ish star Yara Shahidi. The issue also introduced “21 Under 21,” the magazine’s “official guide to the girls and femmes changing the world.” The list of young activists, artists, and advocates featured few household names, but a notable majority of young people of color.

If the magazine is finally gaining recognition among adults for its thoughtful, nuanced coverage of topical issues, it’s less surprising to teen readers who’ve been for months taking in (and sharing) stories about the Standing Rock Protests or Texas’s campus-carry laws. In many ways, Teen Vogue is simply doing what a fashion magazine does best: observing trends, and disseminating them. But it’s also giving young women valuable information about issues they care about, not to mention taking them—and their manifold interests—seriously.

“When it comes to news and politics, we look at ourselves as an ally and a platform—particularly to young women, and young people from marginalized communities,” Picardi said. “I think young people, and perhaps particularly young women are so wildly underestimated by the world at large, and I want us to be a platform that challenges that idea.”

It's a Grand Old False Flag

Time was, the phrase “false flag” was fodder for Twitter jokes and fringe conspiracy theorists. These days, the president-elect is a Twitter superuser, and the conspiracy theorists are in his inner circle.

A case in point is the raging debate over whether alleged Russian hacking was intended to influence the course of the presidential election. The CIA has decided the answer is yes, delivering that judgment to legislators and President Obama based on a what The New York Times reports is a circumstantial but sizable collection of evidence.

Related Story

Five Questions About Russia's Election Hacking

That conclusion has divided both left and right. Many Democrats are eager to seize on the conclusions as an explanation for Hillary Clinton’s defeat last month, while some liberals—notably Glenn Greenwald—call for more skepticism of the intelligence community, in light of its past record. (An interesting case is Senator Ron Wyden, an outspoken advocate for tighter oversight of U.S. intelligence who has also defended the agency against recent attacks from Donald Trump.)

The fact that Republicans, the erstwhile party of hardline Cold Warriors, is divided over whether to believe the intelligence about Russia, and unsure how to respond, is an epochal shift, as Peter Beinart wrote this morning. Yet even since Beinart wrote that piece, there have been some signs of movement among traditional establishment Republicans. Russell Berman reports that Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced that the Senate will investigate claims of Russian interference. (Republican senators including John McCain and Lindsey Graham were clamoring for investigation.) Speaker Paul Ryan issued a more tepid statement, saying that on the one hand, “We must condemn and push back forcefully against any state-sponsored cyberattacks on our democratic process,” while on the other hand warning, “We should not cast doubt on the clear and decisive outcome of this election.”

But some of Trump’s closest allies, by contrast, aren’t just trying to push back on investigations, and they’re aren’t just skeptical of the intelligence, like Trump, who flatly rejected it on Sunday: “I think it’s ridiculous. I think it’s just another excuse. I don’t believe it.” (Incidentally, he also copped to skipping intelligence briefings, saying, “You know, I’m, like, a smart person. I don’t have to be told the same thing in the same words every single day for the next eight years.”) The president-elect seems to have forgotten that he publicly asked Russia to hack Clinton’s emails.

Instead, these are making a very public claim that the hacking is a false-flag attack, which has either fooled the CIA and other American intelligence agencies or, even worse, in which they may be complicit.

Appearing on Fox News Sunday evening, John Bolton suggested that someone might have tried to imitate the Russians so as to shift blame onto the Kremlin for the hacks. “It is not at all clear to me, viewing this from the outside, that this hacking into the DNC and the RNC computers was not a false flag operation,” Bolton said, adding that “a really sophisticated foreign intelligence service would not leave any fingerprints.” Fox’s Eric Shawn pressed Bolton to say who he thought might be behind such an attack. Bolton seemed to imply an inside job, saying, “We just don’t know. But I believe that intelligence has been politicized in the Obama administration to a very significant degree.” Monday morning, Bolton told Fox and Friends he did not mean to suggest that the administration itself was behind the false flag. Bolton did, however, break with Trump in suggesting an investigation into the matter.

Bolton isn’t just some commentator, and he’s also not just the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. He’s also reportedly Trump’s likely pick as deputy secretary of state. Another possible Trump appointee is former GOP presidential candidate Carly Fiorina, who met with Trump today and is reportedly under consideration for director of national intelligence.

Upon emerging from her meeting with Trump, Fiorina, offered a rather opaque, brief statement, which could be read as suggesting China was the culprit. “We ... spent a fair amount of time talking about China as probably our most important adversary and a rising adversary,” she said. “We talked about hacking, whether it's Chinese hacking or purported Russian hacking.” She may also have been referring to prior cases of U.S. officials concluding China had hacked government computers.

Meanwhile, Carter Page, a former Trump adviser whom the FBI reportedly investigated him for communicating with senior Russian officials, has been in Moscow recently. On Monday, he spoke at a Russian state-owned media company. Page spent large chunks of his 30-minute address railing against what he called “fake news,” though his definition seemed to encompass plenty of reporting he simply didn’t like or agree with, rather than made-up, intentionally fictional content, as well as Wikipedia, which is not a news site at all. During a question-and-answer session afterwards, he was asked about reports of Russian hacking. His answer, flagged by the Times’ Ivan Nechepurenko, was that he suspected a false flag.

“It’s very easy to make it look exactly like it was country X, in this case Russia, that did this,” he said. “I think that’s very much overestimated and personally I think until there’s serious evidence, you know it’s very similar to what I’ve personally been through. A lot of speculation but nothing there.”

“Are you saying it was a setup? A deliberate attempt to make it look like Russia?” someone asked. Page replied:

I think it very well could have been, certainly. I’ve talked with various IT experts that have suggested that that could very well be a serious possibility. These guys are pros to make certain paths that can mislead. Again, we’ve seen certain, many mistakes from an intelligence standpoint previously.

There’s a rich irony here. The CIA’s assessments should absolutely be questioned and prodded, and congressional investigations are a welcome addition. But even as Bolton and Page and even Trump—who said, “They have no idea if it's Russia or China or somebody sitting in a bed some place”—argue that the intelligence community has not provided enough public evidence to prove their point to satisfaction, they are offering entirely speculative alternative scenarios, without any evidence of their own.

In casting doubt on the going theory, however, these figures are at least in good company. Alex Jones, the radio host who is America’s leading proponent of false-flag theories, has finally found a shadowy connection he’s unwilling to believe. Speaking of the CIA conclusion blaming Russia, Jones tweeted Monday afternoon, “Absolutely no evidence has been produced to substantiate the conspiracy theory.”

Bob Dylan’s Subversively Humble Nobel Speech

Bob Dylan’s silence upon being named the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature earlier this year was widely taken as a statement in itself. Some people saw it as a classic moment of Dylan-esque mystery and disdain for pomp; others took it as, per one Swedish Academy member, “impolite and arrogant.” Of course, it could be both, as it often has been for him. There’s a reason the first words of Todd Haynes’s film I’m Not There, a Dylan tribute, are “There he lies, God rest his soul … and his rudeness.”

But Dylan now has suggested that his delayed reaction was simply out of shock. “I was out on the road when I received this surprising news, and it took me more than a few minutes to properly process it,” he wrote in his Nobel acceptance speech, delivered at the prize banquet over the weekend by America’s ambassador to Sweden. The speech in general is a performance of humility, projecting an unassuming, workmanlike persona in response to being granted the literary world’s highest accolade—and implying that such accolades are more a reflection on consumers of art than on artists themselves.

“Being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is something I never could have imagined or seen coming,” he said toward the start of the speech. “From an early age, I've been familiar with and reading and absorbing the works of those who were deemed worthy of such a distinction: Kipling, Shaw, Thomas Mann, Pearl Buck, Albert Camus, Hemingway. These giants of literature whose works are taught in the schoolroom, housed in libraries around the world and spoken of in reverent tones have always made a deep impression. That I now join the names on such a list is truly beyond words.”

The language there and elsewhere in the speech would not, on its face, inspire the description “literary.” It’s plain and almost school-age, moonily referring to “giants of literature” and a feeling “beyond words.” He went on to say that he imagines William Shakespeare spent less time concerned by abstract ideas than by practicalities: “‘Who're the right actors for these roles?’ ‘How should this be staged?’ ‘Do I really want to set this in Denmark?’” Dylan relates:

But, like Shakespeare, I too am often occupied with the pursuit of my creative endeavors and dealing with all aspects of life's mundane matters. "Who are the best musicians for these songs?" "Am I recording in the right studio?" "Is this song in the right key?" Some things never change, even in 400 years.

Not once have I ever had the time to ask myself, "Are my songs literature?"

So, I do thank the Swedish Academy, both for taking the time to consider that very question, and, ultimately, for providing such a wonderful answer.

It’s not that he doesn’t want to question whether his songs are literature, it’s that he hasn’t had the time. This sort of indifference to the act of interpretation has been a feature of his career, and the image of the Nobel ceremony—a tuxedoed crowd, a lavish venue, the queen of Sweden in a sparkling gown—certainly supports the notion of analysis as luxury, rather than as essential labor. It remains to be seen whether he’ll deliver the lecture he’s required to give in order to officially accept the Nobel and its prize money (8 million Swedish krona); all his camp has apparently said about the matter is that he might be able to give a lecture when he next swings through Stockholm on tour.

The ceremony itself did, in the end, broach the philosophical question that Dylan said he’s never had a moment to consider. Academy member Horace Engdahl gave an address whose rhetoric and whose ambitions presented a polar contrast with the singer’s speech. He began by asserting that literary evolution happens often “when someone seizes upon a simple, overlooked form, discounted as art in the higher sense, and makes it mutate.” Dylan’s feat: “From what he discovered in heirloom and scrap, in banal rhyme and quick wit, in curses and pious prayers, sweet nothings and crude jokes, he panned poetry gold.”

Synthesis between accolade and art, between high critical thought and catchy folk music, then came courtesy of the rock poet and Dylan friend Patti Smith. She delivered an aching rendition of his song “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” during which she forgot the words to the second verse and had to start again—a mistake that only heightened the lyrics’ mystery and power. Over the years, listeners have spun various interpretations of the song, with one common thought being that Dylan was imagining nuclear fallout. But his own explanation is not nearly so neat. “Every line in it, is actually the start of a whole song,” he said in the liner notes for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. “But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.” Then as now, he professes that his only focus is on the process itself. It’s for everyone else to focus on what the results of that process mean.

Donald Trump Starts a Dogfight With the F-35

It’s another week and time for more plane speaking from the president-elect.

Last week, Trump took on Boeing and its contract to produce a new Air Force One. Monday morning, it was Lockheed Martin and the controversial F-35 Joint Strike Fighter:

The F-35 program and cost is out of control. Billions of dollars can and will be saved on military (and other) purchases after January 20th.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 12, 2016

I’ve been trying to develop a three-question triage approach for each of these tweet-driven fire drills. First, why is Trump talking about this now? Second, how close is he to the truth? Three, are his ideas at all plausible, and if so, who will benefit?

The answer to the first question is almost always a news report somewhere, and speculation Monday morning immediately turned to reports about Israel taking possession of two F-35s today, complete with a visit from Defense Secretary Ash Carter to mark the moment. Since Trump has shown no sign that his early-morning tweets are systematic, and since the plane hasn’t been in the news much otherwise, that seems like a safe bet. It’s actually not the first time Trump has criticized the F-35, though. Last October, before he was really taken seriously as a candidate, Trump told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt he was skeptical of the plane.

Related Story

The Tragedy of the American Military

“I do hear that it’s not very good,” he said, prompted by Hewitt. “I’m hearing that our existing planes are better. And one of the pilots came out of the plane, one of the test pilots, and said this isn’t as good as what we already have.”

Second, how close is Trump to the truth? Many observers have deemed the F-35 a boondoggle suffering from enormous cost overruns and serious underperformance. James Fallows wrote in his deep dive into the U.S. military’s weaknesses last year:

The condensed version of this plane’s tragedy is that a project meant to correct some of the Pentagon’s deepest problems in designing and paying for weapons has in fact worsened and come to exemplify them. An aircraft that was intended to be inexpensive, adaptable, and reliable has become the most expensive in history, and among the hardest to keep out of the shop.

The plane started out running roughly $135 million a piece, though that figure has slowly decreased as more are built. In total, Fallows noted, the project has cost about $1.5 trillion, around the same as the war in Iraq. “The F-35 is an ill-starred undertaking that would have been on the front pages as often as other botched federal projects, from the Obamacare rollout to the FEMA response after Hurricane Katrina, if, like those others, it either seemed to affect a broad class of people or could easily be shown on TV—or if so many politicians didn’t have a stake in protecting it,” he wrote.

Third, Trump’s apparent stance on the F-35—it’s hard to tell how thought-out or permanent any of these notions are—is one of his positions that cut across party lines. The plane’s critics range from lefties who see it as just another case of Pentagon bloat to conservative hawks who see it as good money spent on a bad project. Its defenders similarly run the gamut, from the military contractors who benefit from the plane to the members of Congress who want the plane constructed in their constituencies.

Some progressives will view Trump’s attack as a welcome broadside against the military-industrial complex, though they’re probably misguided if they expect to find much of an ally in Trump. He has made repealing the Defense sequester a priority, and wants to expand every branch of the armed forces by large amounts. Estimates of what all that would cost run around $100 billion—or about 1,000 times the cost of an F-35. While the F-35’s supply chain stretches around the country and around the globe, final assembly takes place in Fort Worth, in ruby-red Texas.

Last week, I noted that the heavy concentration of Army and Marine generals in Trump’s inner circle might be a cause of consternation for brass in the Air Force and Marines; the Air Force will be the biggest consumer of the F-35.

Conservatives may also blanch at Trump interfering—yet again, after his deal with Carrier and his jabs at Boeing—with free enterprise. Trump’s tweet sent Lockheed Martin stock into a nosedive (or a stall, or a tailspin, or… well, pick your own aviation cliche), dropping nearly 3 percent before U.S. markets opened. Something similar happened to Boeing last week, but the stock basically recovered after the initial shock. (Lockheed had been trading high before; just Sunday, Motley Fool was remarking on what a great boon the F-35 had been for the contractor.)

It doesn’t take much creativity to start spinning conspiracy theories about Trump messing with the market for financial benefit, his own or someone else’s. Forbes last week ran a column about how one might try to game the stock market by anticipating who Trump might assail on Twitter. Peter Cohan wrote that if you could guess effectively, that would be profitable, although trying to anticipate Trump is generally a fool’s errand. What if you didn’t have to guess, though? What if you knew what Trump was going to tweet before he did it? Trump has been accused of securities violations before and settled suits with the government. He could go a long way toward dampening speculation of skullduggery here by providing the measures of transparency he has so far refused, including releasing his tax returns, putting his own finances in a blind trust, and providing proof he has in fact sold off all his equities, as an aide claimed last week that he had done this summer.

As for the airplane, the question here is whether Trump can kill a project that others have tried in vain to stop? Past efforts have tended to founder because the F-35’s critics have assumed that huge costs and obviously underwhelming performance was enough to slay the beast. What they misunderstood was the effect to which the plane’s high costs and sprawling manufacturing scheme are features as well as bugs. Since the project provides large sums of money to congressional districts around the country, it has lot of quiet defenders in Congress. As with many government programs, but perhaps even more vividly, the public tells pollsters it want less defense spending in the abstract but won’t take to the streets to cut the Pentagon budget when push comes to shove.

Trump acts immune to these political pressures, but there hasn’t been a good test of whether he really is. Republicans in Congress have responded meekly to some of his provocations, but he also isn’t in the White House and making real policy yet.

But it also may be too late for Trump to make a difference—no matter how little he cares about breaking china. Many of the reporters who have looked most closely at the F-35, including Fallows, Kelsey Atherton, and Mark Thompson, have concluded that it’s probably too late to block it. The program is simply too far entrenched. If Trump truly wants to save military money, he’d be better served by looking forward and killing the next F-35 before it gets too big. But that’s harder and less fun that watching the morning news and firing off tweets about it.

Related Video:

La La Land and Moonlight See Golden Globes Love

The Golden Globe Awards, Hollywood’s annual kick-off for the Oscar race, announced its nominees Monday morning and anointed La La Land, Moonlight, and Manchester by the Sea as the year’s big contenders, with seven, six, and five nominations respectively. On the television side, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association lavished attention on popular new shows like Westworld, Stranger Things, The Crown, and This Is Us. The winners will be announced at a Jimmy Fallon-hosted ceremony on January 8.

Outside of recognizing the three leading favorites, the Globe nominations indicated a confused Oscar season ahead, giving multiple nominations to films like Mel Gibson’s war drama Hacksaw Ridge, the airy British comedy Florence Foster Jenkins, and Tom Ford’s moody Nocturnal Animals, all of which had seemed on the outskirts of the race. Expected awards darlings like Arrival and Jackie were largely ignored outside of their leading performers, and Martin Scorsese’s long-awaited period drama Silence was entirely shut out, perhaps doomed by its late release date. In fact, the nominations heavily favored films that came out earlier in the fall, indicating that the traditional Oscar tactic of waiting until Christmas to release a major film is prone to backfiring.

Awards season has always seemed endless, but it used to drag on through the end of March or the beginning of April, when the Academy Awards were traditionally held. Now that the Oscars air in late February, the “precursor” season has become more compressed, and the Globes have shifted their ceremony date earlier and earlier as a result; January 8 is the earliest they’ve ever been scheduled. That makes December an almost irrelevant month for groups like the HFPA. Though La La Land (released last weekend) was acclaimed enough to break through, films like Silence, Paterson, Patriot’s Day, Gold, and Live By Night have been relegated to also-rans.

The continued success of Hacksaw Ridge, which got nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor (Andrew Garfield) is somewhat surprising given Gibson’s many past transgressions, including making anti-Semitic remarks when he was arrested for a DUI, making racist remarks to his ex-girlfriend, and pleading no contest to a misdemeanor spousal battery charge. Gibson has acknowledged his past on his publicity tour for Hacksaw Ridge, telling Stephen Colbert on The Late Show that his anti-Semitic rant was “not my proudest moment.” But his “apology tour” has largely lacked in apologies, a strategy that has nonetheless propelled his film to the top of the awards pile so far.

Other films that gained a foothold with the Globes were the inspirational drama Lion, recognized in the Best Picture category and for Dev Patel and Nicole Kidman’s performances; the sleeper bank-robber drama Hell or High Water, which was one of the summer’s most acclaimed films; and the aforementioned Nocturnal Animals, which is the kind of stylish, star-laden affair perfectly pitched at the Hollywood Foreign Press, the 92-member award body that decides the Globe nominations. Florence Foster Jenkins dominated in the “comedy or musical” categories (alongside La La Land), though its path to Oscar success will be less clear without the help of genre distinctions. The satirical superhero movie Deadpool also got two comedy nominations in recognition of its breakout year.

On the TV side, the Globes have always favored new shows, as a way of elevating contenders for next summer’s Emmys. Netflix’s The Crown got nods for its performers Claire Foy and John Lithgow, NBC’s surprise hit This Is Us edged its way into a field dominated by streaming and premium cable networks, and HBO received expected attention for Westworld as well as a heartening nomination for Issa Rae in Insecure. Rae and Black-ish’s Tracee Ellis Ross were both nominated for Best TV Actress in a Comedy this year, the first time an African American woman has made that field since 1985 (Isabel Sanford for The Jeffersons). FX’s critically acclaimed Atlanta also made the comedy cut, as did its creator and star Donald Glover in the Best Actor category.

The full list of nominations below:

Best Picture (Drama)

Hacksaw Ridge

Hell or High Water

Lion

Manchester by the Sea

Moonlight

Best Actor (Drama)

Casey Affleck, Manchester by the Sea

Joel Edgerton, Loving

Andrew Garfield, Hacksaw Ridge

Viggo Mortensen, Captain Fantastic

Denzel Washington, Fences

Best Actress (Drama)

Amy Adams, Arrival

Jessica Chastain, Miss Sloane

Isabelle Huppert, Elle

Ruth Negga, Loving

Natalie Portman, Jackie

Best Picture (Comedy/Musical)

20th Century Women

Deadpool

La La Land

Florence Foster Jenkins

Sing Street

Best Actor (Comedy/Musical)

Colin Farrell, The Lobster

Ryan Gosling, La La Land

Hugh Grant, Florence Foster Jenkins

Jonah Hill, War Dogs

Ryan Reynolds, Deadpool

Best Actress (Comedy/Musical)

Annette Bening, 20th Century Women

Lily Collins, Rules Don’t Apply

Hailee Steinfeld, The Edge of Seventeen

Emma Stone, La La Land

Meryl Streep, Florence Foster Jenkins

Best Supporting Actor in a Film

Mahershala Ali, Moonlight

Jeff Bridges, Hell or High Water

Simon Helberg, Florence Foster Jenkins

Dev Patel, Lion

Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Nocturnal Animals

Best Supporting Actress in a Film

Viola Davis, Fences

Naomie Harris, Moonlight

Nicole Kidman, Lion

Octavia Spencer, Hidden Figures

Michelle Williams, Manchester by the Sea

Best Director

Damien Chazelle, La La Land

Tom Ford, Nocturnal Animals

Mel Gibson, Hacksaw Ridge

Barry Jenkins, Moonlight

Kenneth Lonergan, Manchester by the Sea

Best Screenplay

La La Land

Nocturnal Animals

Moonlight

Manchester by the Sea

Hell or High Water

Best Foreign Language Film

Divines (France)

Elle (France)

Neruda (Chile)

The Salesman (Iran)

Toni Erdmann (Germany)

Best Animated Film

Kubo and the Two Strings

Moana

My Life as a Zucchini

Sing

Zootopia

Best Original Song

“Can’t Stop The Feeling,” Trolls

“City Of Stars,” La La Land

“Faith,” Sing

“Gold,” Gold

“How Far I’ll Go,” Moana

Best Original Score

Nicholas Britell, Moonlight

Justin Hurwitz, La La Land

Johann Johannsson, Arrival

Dustin O’Halloran & Hauschka, Lion

Hans Zimmer, Pharrel Williams, and Benjamin Wallfisch, Hidden Figures

Best Television Series (Drama)

The Crown

Game Of Thrones

Stranger Things

This Is Us

Westworld

Best Television Series (Musical/Comedy)

Atlanta

Black-ish

Mozart In The Jungle

Transparent

Veep

Best Actor in a Television Series (Drama)

Rami Malek, Mr. Robot

Bob Odenkirk, Better Call Saul

Matthew Rhys, The Americans

Liev Schreiber, Ray Donovan

Billy Bob Thornton, Goliath

Best Actress In A Television Series (Drama)

Caitriona Balfe, Outlander

Claire Foy, The Crown

Keri Russell, The Americans

Winona Ryder, Stranger Things

Evan Rachel Wood, Westworld

Best Actor in a Television Series (Musical/Comedy)

Anthony Anderson, Black-ish

Gael García Bernal, Mozart in the Jungle

Donald Glover, Atlanta

Nick Nolte, Graves

Jeffrey Tambor, Transparent

Best Actress in a Television Series (Musical/Comedy)

Rachel Bloom, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Veep

Sarah Jessica Parker, Divorce

Issa Rae, Insecure

Gina Rodriguez, Jane the Virgin

Tracee Ellis-Ross, Black-ish

Best Limited TV Series

American Crime

The Dresser

The Night Manager

The Night Of

The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

Best Actor in a Limited Series or Motion Picture Made for Television

Riz Ahmed, The Night Of

Bryan Cranston, All The Way

Tom Hiddleston, The Night Manager

John Turturro, The Night Of

Courtney B. Vance, The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

Best Actress in a Limited Series or Motion Picture Made for Television

Felicity Huffman, American Crime

Riley Keough, The Girlfriend Experience

Sarah Paulson, The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

Charlotte Rampling, London Spy

Kerry Washington, Confirmation

Best Supporting Actress in a Series, Limited Series or Motion Picture Made for Television

Olivia Colman, The Night Manager

Lena Headey, Game Of Thrones

Chrissy Metz, This Is Us

Mandy Moore, This Is Us

Thandie Newton, Westworld

Best Supporting Actor in a Series, Limited Series or Motion Picture Made for Television

Sterling K Brown, The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

Hugh Laurie, The Night Manager

John Lithgow, The Crown

Christian Slater, Mr. Robot

John Travolta, The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story

December 11, 2016

Finding Wisdom in the Letters of Aging Writers

In 1975, a 63-year-old Elizabeth Bishop wrote to her long-time friend and fellow poet Robert Lowell, who was then 58 and just two years from his death. “I’m going to be very impertinent and aggressive,” she wrote. “Please, please don’t talk about old age so much, my dear old friend! You are giving me the creeps.” In many ways, Bishop’s admonition of Lowell is the perfect expression of a particular antagonism toward the changes and challenges brought on by aging. This discomfort isn’t simply garden-variety fear, or even denial, but an insurgency-like resistance.

You see this attitude about growing older reflected in pop culture today. A recent USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism study looked at the 100 top-grossing films of 2015 and found that older characters were often discussed with ageist and “troubling” language, and that senior citizens are underrepresented in the medium. Popular music is, and has always been, dominated by the young, and TV rarely focuses on the lives of people older than 60 with the same nuance it reserves for the young. There are exceptions of course, but because of this broader cultural antipathy, the inner lives of late-middle age and elderly Americans remain the unexamined deep sea of the culture.

Even the TV shows, songs, or works of fiction by or about an older person don’t necessarily represent the artist’s private experience of the world. This is where the late letters of great artists, particularly writers, can offer a valuable window into the realities of older age. It’s through his letters that we learn that Saul Bellow realized even the world’s best fiction and drama could not truly capture the personal side of aging. In 1996, Bellow wrote to the critic James Wood, “I had, as a fanatical or engagé reader, studied over many decades gallery after gallery of old men in novels in plays and I thought I knew all about them.” Bellow then mentions a number of characters, including Prince Bolkonsky in War and Peace and King Lear, before concluding, “But all of this business about crabbed age and youth tells you absolutely nothing about your own self.”

Meanwhile, the epistolary collections of famous writers suggest that the ordinary letter, freed from the self-consciousness and professional considerations of the manuscript, can offer rare insights into aging. This year saw the publication of the fourth and final volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters, The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1966-1989, representing his correspondence from the age of 60 to his death at the age of 83. This marvelous volume follows two equally important collections of letters from the past decade, Saul Bellow: Letters (2010) and Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell (2008), which have been singled out by critics as works destined to become classics.

As 21st-century writers have transitioned from letter writing to email, a specific literary tradition seems to have come to its end, one that offered a slower, more meditative, and writerly microscope into all aspects of life, including the aging process. Reading these letters is meaningful, not so much because some elderly people are “wise.” Rather, there is much practical and intellectual guidance to be gleaned from spending time with imaginative, highly articulate individuals as they face the existential realities of illness, declining productivity, the death of friends, guilt, and, finally, letting go of cherished activities and passions.

Reading the late letters of Samuel Beckett, it becomes clear his youthful pessimism positioned him quite well for the physical and mental challenges of aging. In his introduction to Beckett’s letters, the editor Dan Gunn writes, “There is a sense in which if ever anyone were suited to, and prepared for, the inevitable winnowings of old age, that person is Beckett, harbouring as he seems to have done, practically from the outset, an old man within him.”

Whereas Lowell and Bellow were prone to ruminate philosophically on aging, Beckett would only mention it occasionally, and matter-of-factly, with little reflection or prejudice. Writing in 1968 about his ongoing eye troubles in his early 60s, Beckett notes: “Nothing to be done about eyes for the moment. They are perhaps very slightly worse, hard to say. Well there it is, old age in all its beauty, funny I didn’t see it sooner.” Certain instances in the letters, such as the preceding one, read as if Beckett had achieved a kind of Zen Buddhist “Middle Way,” where aging was neither something to resist nor analyze, neither good nor bad. It is a rather uncomplicated outlook, and possibly a sensible curative to a cultural impulse to preserve youth at all costs.

Beckett understood the nursing-home as a place where loneliness could be fodder for redemption.

But despite the benefits of Beckett’s attitude, he’s not quite an exemplar of healthful aging: His “lifestyle” was that of a Parisian Bohemian, and he seemed unconcerned about the harmful physical effects of smoking and drinking. After an illness in 1969, he writes, “I am almost quite well again. I have not smoked for nearly a year, but hope to light up again soon. Whiskey too was out for a time but has now resumed its kind offices.” This all may sound deliberately reckless and irresponsible in 2016, but in the final analysis, Beckett lived until he was 83 and was active and productive late into life. His letters are a reminder to avoid seeking out a single cookie-cutter approach to living a long and active life, since everyone must draft their own map through trial and error.

Letters also give readers glimpses into the little everyday indignities and mishaps that anyone over 60 is familiar with. It’s comforting, at times humorous, and even liberating to read about the kind of falls and mishaps that are commonly left out of the biographies of Nobel Prize winners. “Might have damaged myself beyond repair last night in the bathroom,” Beckett writes at the age of 69 to his life-long mistress Barbara Bray in 1975. “Had got out of the bath & was drying myself with my back to it when my feet slipped & I fell in backward.” Two years later he writes, “I slipped & fell in the street yesterday, but could pick myself up & go on cursing God & man.” This elliptical sentence exemplifies what is great about Beckett’s letters, and about his approach to growing old. He falls down—he of course gets up. But then, in a perfect Beckettian flourish, he curses both God and man, though one can almost hear the wink-and-nod of Irish sarcasm, tossed in for the benefit of his reader.

The onset of middle age, and beyond, often prompts the second-guessing of old decisions. Some feel guilty about relationships pursued (or not pursued), while others wish they had followed an early passion or artistic impulse. In three separate letters, Beckett discusses his remorse about not going to work for the Guinness beer company in Dublin just as his middle-class father had repeatedly suggested. It’s a detail that many unfulfilled workers should ponder: A life as a successful musician, or All-Pro quarterback, or even as a Nobel Prize-winning writer for that matter, does not exempt one from the pangs of occupational regret. You can be brilliant; you can write Waiting for Godot, you can have an apartment in Paris and a house in the French countryside, and still wonder if you’d be happier being a 9-to-5 drone in a Dublin office cubicle.

In 1988 Beckett’s life took its most severe turn when he entered a nursing home in Paris. He understood this was his final home. He writes, “Still here with the old crocks [Beckett’s slang for old people], it sometimes feels for keeps.” A year later, during his final year, his letters become shorter, terser, more like emails than epistles. In one of the more touching lines, he ends a letter to his friend Rick Cluchey by writing: “Silence is my cloister.” A long life, by its very nature, ensures that one will witness the death of close of friends, potentially even a spouse, and many others who have formed one’s community. And when one is removed to a nursing home, social isolation becomes a reality—and there is no roadmap for such challenges. But perhaps Beckett did understand the nursing-home experience as something of a monastery-like place of contemplation, a place where loneliness and isolation could, perhaps, be spiritual fodder for personal redemption.

Like Beckett, Bellow lived into his 80s, facing a type of decline that both Bishop and Lowell avoided by dying in their 60s. Yet with Bellow, aging takes on a much different look, and a distinctly American one at that. Though born in Canada to Russian immigrants, Bellow’s work ethic, passions, and “adolescent ambition” (his words) seemed to perfectly mirror his adopted nation’s exuberant rise during the so-called “American Century.”

The joy of Bellow’s letters is that they often combine geriatric insight with his customary literary flare.

Aging forces many people to modify their work habits and face the reality of diminished energy and output. Bellow was a man whose rise to literary fame was accelerated by his endless reserves of energy. He could write all day like a fury, and as he aged, he began to watch this productivity falter. In 1975, at the age of 60, he writes of arriving in Spain in an exhausted state: “I let myself go, here, and let myself feel six decades of trying hard, and of fatigue.” In 1984 he writes in a similar vein: “To age is to understand that the powers of total recovery are gone, are no longer anticipated (except by those who, having lost their marbles, no longer know what to anticipate).” Yes, Bellow wrote well into his 80s, publishing Ravelstein in 2000. But along the way, he had to curb his famous output, make compromises and admit limitations. In 1991, at the age of 76, he writes his friend and fellow writer John Auerbach:

I am trying to meet a deadline imposed by a contract that I signed in order to spur myself to work more quickly. But I haven’t got the energy I once had. Well into my late sixties I could work all day long. Now I fold at one o’ clock. Most days I can’t do without a siesta.

The joy of Bellow’s letters—in contrast to Beckett’s straightforward correspondence—is that they often combine geriatric insight with his customary literary flare. In a 1997 letter where he mentions a recent ICU stint, he adds, “Then there is the stamp of old age on the face, head, hands, and ankles. These blue-cheese ankles—what a punishment for narcissists!”—a perfect image of how the human body changes and how this process agonizes the ego. And then, astutely describing the sense of both violation and intimacy one feels toward aging, he writes two years later, “I often feel these days that death is a derelict or what Americans nowadays call a street person who has moved into the house with me and whom I can find no way to get rid of.”

And if aging feels like an unwanted visitor, it is a visitor who offers seemingly endless opportunities to wistfully compare and contrast the present with the alien landscape of one’s youth: It is the pull of nostalgia, loss, and fascination with time’s passing that creeps in. This was ground Lowell often returned to; at the age of 48 he wrote: “This part of our lives has something of the real changing quality of childhood, more enjoyable on the whole, but with—not here yet, thank God, but ahead—diminishment, disappearance of friends, our own disappearance, etc., waiting. Premature old age! I feel we are now what the young inevitably look on as alien, but real.” Lowell reminds readers of the mixed blessings of aging: There is a certain satisfaction derived from maturity and lessons learned, yet it can be accompanied by the sour realization that most of one’s life has already been lived.

“The end was gentle. The very end. Before the first rest at last.”

Yet Lowell didn’t stop with nostalgia—he was just as comfortable ruminating on the future and his own death. In his early 50s he writes, “I still feel I can reach up and touch the ceiling of one’s end,” and then four years later, he deploys another image of looming obstacles: “There’s a steel cord stretch[ed] tense at about arms-length above us, and what we look forward to must be accompanied by our less grace and strength.” Lowell suffered frequent hospitalizations for manic depression during his lifetime, and it is little wonder he had a tendency toward morbidity.

Bishop offers a counterbalance to this preoccupation with aging. She didn’t spend much time writing to Lowell with observations on the process, which suggests aging wasn’t at the top of her mind; and perhaps this was a more prudent approach, considering Bishop outlived Lowell by eight years. At one point she mentions her arthritis (“the only thing for it is ASPRIN—in huge doses”), but she generally seems unaffected by getting old. “I simply hate talking about myself, more & more, the older I get,” she writes in 1968, perhaps understanding that self-centeredness is often a barrier to achieving happiness.

Aging is undoubtedly an intensely personal experience that gives everyone an opportunity to resist and accept its challenges in equal measures. No one can predict how they will feel upon turning the age that is like, in Lowell’s words, “the ceiling of one’s end.” Yet one can hope to possess, for example, the sound, sensible approach of Bishop, who wrote at the age of 56, “I minded being 35 very much, I remember, but haven’t been able to give a damn since—there are too many other things that one can do a little something about, possibly.” Then of course there is the Beckettian approach, which assumes you’ve been fortunate enough to have lived as long as he, and to have cultivated a certain gentlemanly détente with life and death, so that you have the perspective to confidently write, as he did about his wife’s death in 1989, “The end was gentle. The very end. Before the first rest at last.” He was writing about Suzanne Beckett, but once you’ve read and reflected on the man in these letters, it’s easy to suspect it is how he experienced his own last moments, his own gentle end, on a winter day in Paris, and just a few days before Christmas.

December 10, 2016

García Márquez and Hollywood Hackers: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Fifty Years of Disquietude

Joel Whitney | The Baffler

“As García Márquez’s great novel turns 50 and panels and thinkpieces debate its legacy, and as the book’s U.S. boosters focus on its mechanics, its inspiration, and its influence on future writers and those who influenced it, it’s high time to unravel the novel’s incidental and almost invisible weaponization in the Cold War—its politics and the politics that helped García Márquez write it.”

This Was the Year America Finally Saw the South

Jesmyn Ward | Buzzfeed

“My generation has felt half-seen for years. We’ve had glorious moments when we’ve been sharply in focus, reflected back in the faces of our artists, our ambassadors to elsewhere. UGK. Erykah Badu. Outkast. But when our favorites with national exposure semi-retire (E. Badu and Outkast) or die (Pimp C), then we do what we’ve always done. We retreat to our locals. Seeing ourselves in Southern hip-hop comforts in some respects. It gives us a sense of cultural cohesion, of identity, of common language.”

Why There’s No Millennial Novel

Tony Tulathimutte | The New York Times

“The generational novel, like the Great American Novel, is a comforting romantic myth, which wrongly assumes that commonality is more significant than individuality … The experience of identity—whether it’s race, religion, nationality, gender or generational membership—is certainly necessary for a full portrait of a person, but never sufficient. There’s also memory, thought, feeling, perception, neurochemistry, mood, and everything else.”

Mr. Robot Killed the Hollywood Hacker

Cory Doctorow | MIT Technology Review

“It’s about time. The persistence until now of what the geeks call ‘Hollywood OS,’ in which computers do impossible things just to make the plot go, hasn’t just resulted in bad movies. It’s confused people about what computers can and can’t do. It’s made us afraid of the wrong things. It’s led lawmakers to create a terrible law that’s done tangible harm.”

The ‘Soft Power’ of Art

Ric Kasini Kadour | Hyperallergic

“We live in a time of historic, global wealth inequality and increasing political turbulence ... It feels, at times, as if Western Civilization, as we have known it, is unraveling into the dark muddle it found itself in 100 years ago. What are artists to do?”

Bertolucci’s Justification for the Last Tango Rape Scene Is Bogus

Jessica Tovey | The Guardian

“The argument that the action is justified for the sake of an authentic reaction is bogus. It is called ‘acting’ for a reason. It’s not supposed to be real, it is pretending. The magic of an incredible performance comes when an actor delves into their imagination and taps into emotions that are very real; it often leaves us physically and mentally drained but we accept it as part of the job because we know the power of stories and we want to share them with the audience.”

The Year that Culture Disappeared

Ryu Spaeth | The New Republic

“The problem is not only that culture was displaced by what was quite possibly the craziest political campaign in American history. That is understandable, especially given the real-world consequences that will ensue from the spectacle. It is that our cultural institutions—Hollywood, television, book publishing, the news media, the recording industry, the big three sporting leagues—were so impotent in the face of Trump’s rise.”

Listening as Activism: The Sonic Meditations of Pauline Oliveros

Kerry O’Brien | The New Yorker

“Considered as a healing practice—or a ‘tuning of mind and body’—Oliveros’s ‘Sonic Meditations’ are, to an extent, unique in the history of musical experimentalism. In these works, experiments were not conducted on the music; the music was an experiment on the self. Anyone searching today for the complete box set of ‘Sonic Meditations’ won’t find it, because, as the composer wrote, ‘music is a welcome by-product’ of this composition. The experiments remain in each listener.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower