Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 29

December 23, 2016

When A Monster Calls, Just Ignore It

Every Christmas season, there’s at least one film that rumbles into theaters with the sole purpose of yanking tears from its most cold-hearted viewers. Enter A Monster Calls, a story about a young boy wrestling with his mother’s terminal illness. In a way, the film succeeds; it’s hard not to get choked up at a premise like that. But as the movie rumbled toward its inevitably devastating conclusion, the chief emotion I felt wasn’t sadness but annoyance at the dashed grander potential.

A Monster Calls is a visually inventive piece of magical realism that sets out to unravel the cloying narratives people often weave around their own grief. It mixes the intimate sorrow of 12-year-old Connor (Lewis MacDougall), whose mother Lizzie (Felicity Jones) is dying, with the painterly CGI extravaganza of a titanic tree monster (voiced by Liam Neeson) who visits Connor in the night to tell him strange folk stories. Directed by J.A. Bayona (the Spanish filmmaker behind the artful horror movie The Orphanage and the overwrought disaster epic The Impossible), A Monster Calls is at once trying to subvert children’s fairytales and become a classic in that genre. But it ends up succeeding at neither goal, instead leaning on obvious, manipulative storytelling tactics to ineptly tie its two narratives together.

Bayona’s The Orphanage was a fine haunted-house movie, and A Monster Calls could honestly benefit from more subtle menace, given that its best moments are its most quiet. As his mother spends much of her time in the hospital, Connor moves to his grandmother’s manse, which is creepily decorated with porcelain dolls and not-to-be-touched antiques. Bayona conjures something gently unsettling from Connor’s life with his stuffy grandma (played, with a regrettable English accent, by Sigourney Weaver), but whatever nuance he might be aiming for is quickly dispensed with when a giant tree monster rips off Connor’s bedroom wall and starts talking to him.

The dynamic between Connor and the monster is simple: The monster says he will tell Connor three stories and then will want a story in return. Neeson lends his gravelly Irish brogue to the creature, but these scenes feel disappointingly weightless otherwise. The monster might roar, grab Connor with his spindly limbs, or even smash property around him, but his emotional impact is negligible, and his purpose in Connor’s life is kept shrouded in mystery for too long.

Their relationship is openly antagonistic for most of the film. Connor doesn’t understand why the monster keeps bothering him at night, since all he wants is help for his mother. The monster’s repeated mentions that he will eventually need “a story” from Connor ultimately make the purpose of their encounters depressingly clear: This creature of the subconscious is trying to get Connor to realize, and acknowledge, some dark truths. Over the film’s 108-minute running time, Connor and the monster bark the same demands at each other, to little avail. It’s no surprise A Monster Calls is based on a children’s book: The narrative is so simplified the movie exhausts itself trying to keep a minimum level of momentum until its conclusion.

A Monster Calls is a tear-jerking mishmash, a collision of high fantasy and sobering reality.

Outside of his relationship with his mother, viewers get very little sense of what Connor is like as a person. A schoolyard bully repeatedly taunts him for having his head in the clouds, which seems implausibly cruel even by the standard of 12-year-old boys, given that his mother’s illness is public knowledge. The oppressive dreariness of Connor’s real life might work if it were balanced against something more fantastic, but the monster’s scenes are bland and devoid of humor or childlike wonder.

Bayona’s visual sense does come to life in depicting the monster’s fables. Each one is a warped version of a bedtime story, where the heroes and villains seem indistinguishable (Connor’s frustration with his colossal companion comes in part from his disappointment with the tales). Though their purpose to the larger narrative is vague, the stories—rendered in vivid, eerie watercolors—are the most arresting part of the movie. When Connor’s “story” finally arrives, however, in the form of a terrible nightmare, it’s drawn-out and far too reliant on crummy CGI, lacking both the magic of the animated sequences and the heartbreaking fact of his mother’s illness.

The ending still hits home—of course it does, given the upsetting subject matter and the skill of the actors involved (MacDougall makes for a fine young foil to Jones and Weaver). But it’s a poignant blow that the movie doesn’t come close to earning. A Monster Calls is a tear-jerking mishmash, a collision of high fantasy and sobering reality that can’t build its disparate elements into something greater. If you’re looking for a good holiday cry, it’ll likely do the trick; but you may walk out of the theater feeling that its emotional gut-punch was more of a sucker punch.

And, Scene: The Lobster

Over the next two weeks, The Atlantic will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy moment and unpacking what it says about 2016. Today: Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Lobster. (The whole “And, Scene” series will appear here.)

The “choice” that forms the premise of The Lobster is like a curdled Buzzfeed quiz, or a cute personality test from the back of a magazine, that’s been placed in the hands of a Kafkaesque bureaucracy. In the world of the Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos’ fifth film (his English-language debut), anyone who isn’t married by a certain age gets turned into an animal and released into the wild. As the deadline for transformation approaches, the remaining singletons gather in a resort hotel where they’re given 45 days to find a partner. On the plus side, if they can’t, they at least get to choose what animal they want to be for the rest of their lives.

The Lobster is set in a dystopia as dense and in need of exposition as some of 2016’s biggest sci-fi franchises, and an early scene provides exactly that. The hotel’s manager (Olivia Coleman) sits down with the protagonist David (Colin Farrell) to psychologically prepare him for possibly not finding a mate. “The fact that you’ll turn into an animal if you fail to fall in love with someone during your stay here is not something that should upset you, or get you down,” she says. “Just think: As an animal, you’ll have a second chance to find a companion.”

It’s an darkly apt message for a year when apocalyptic predictions have become as common as emoji. Things may seem dire to some in the wake of a horribly divisive election, but think of the ratings! (There’s something laughably unsatisfying about such silver-lining thinking, especially in 2016.) Though the world of The Lobster has the aesthetics of a post-Soviet state, its internal logic is more reminiscent of Gary Shteyngart’s novel Super Sad True Love Story, where romantic partnerships are based on superficial online personae and manic obsessing over one’s own flaws. The rules of The Lobster are clear, even if why they exist is harder to crack.

For David, the choice is clear—if he fails to find love, he wants to be a lobster. “Lobsters live for over 100 years, are blue-blooded, like aristocrats, and stay fertile all their lives,” he intones. “I also like the sea very much. I water-ski and swim quite well, since I was a teenager.” Farrell lists his interests with a robotic lack of feeling. His wonderful performance in the film is almost alien-like: He’s emotionally stunted as everyone else in Lanthimos’s cruel world, but nonetheless he clearly yearns for affection and partnership.

Of course, Lanthimos is satirizing the brutality and horror of searching for romance (not unlike the “dating-app fatigue” my colleague Julie Beck wrote about this year). The Lobster’s hotel is Tinder writ small, with the same singletons bumping into and rejecting each other over and over again for the littlest reasons. One guest (Ben Whishaw) obsesses over his limp, which he acquired when trying to locate his mother at a zoo (she had been turned into a wolf). Another (John C. Reilly) is doomed by his lisp. David is worried that his own brother, who now accompanies him everywhere in dog form, makes him seem doomed. Outside of the hotel, unwed folk who fled to avoid their transformations roam the grounds, a horde of non-conformists fated to live apart from society.

Lanthimos, whose stories always have a strange period tone to them, never directly analyzes the foibles of the modern world. But his films address the pernicious flaws of today’s performative culture better than anyone. In Dogtooth (2009), three adult children raised in an enclosed compound and who have never seen the outside world grow violently obsessed with a secreted pile of VHS tapes, defining their rebellion in terms of the pop culture they’re suddenly inhaling. In Alps (2011), a group starts a business where they impersonate the recently deceased to help people through the grieving process. There’s no artist who better understands the fictitious worlds and personalities we build around ourselves, whether for protection or as a weapon.

The Lobster is also incredibly, drily funny, with unmistakable visuals (just watch this “dance” sequence) and strange, flat dialogue. In the hotel of the film, being basic practically amounts to criminality, as its owner notes when she congratulates David on his unusual choice of creature in the introductory scene. “The first thing most people think of is a dog, which is why the world is full of dogs,” she says with a sigh. How better to mock the supreme superficiality of today’s online life, where people enjoy boiling themselves down to one broadly defined trope, be it a spirit animal or a Hogwarts house? The meta-textual joke came full circle when The Lobster was released. Its official website lets you take a quiz to find out what animal you’d turn into; I, of course, got a dog.

Previously: Everybody Wants Some!!

Next Up: Moonlight

The Scare Quote: 2016 in a Punctuation Mark

Earlier this month, the New York Times reported on Richard Spencer, the white nationalist who is a leader of the alt-right movement. Spencer, the paper noted in its summary, “calls himself a part of the ‘alt-right’—a new term for an informal and ill-defined collection of internet-based radicals.”

The Times, in this instance, used quotation marks to make clear that “alt-right” is not just a term of discussion, but a term of contention: Do not, the floating commas make clear, take this at face value. The story was one more piece of writing that relied on humble quotation marks, during and especially in the aftermath of an election that so often framed facts themselves as matters of debate, to do a lot of heavy lifting—not just as indications of words that are spoken, but as indications of words that are doubted. “Alt-right,” in recent months, joined “fake news” and “post-truth” and “politically correct” and “identity politics” and “normalization” and many, many other buzzterms of this contentious political moment: It got, in the media, scare-quoted.

Scare quotes (also known, even more colorfully, as “shudder quotes” and “sneer quotes”) are identical to standard quotation marks, but do precisely the opposite of what quotation marks are supposed to do: They signal irony, and uncertainty. They suggest words that don’t quite mean what they claim to. “Question,” they say. “Doubt,” they dare. They are, as Greil Marcus recently said, “a writer’s assault on his or her own words.” They signal—really, they celebrate—epistemic uncertainty. They take common ground and suggest that it might, but only just “might,” be made of quicksand.

Quotation marks are “one of the great achievements in human history.”

That signaling is relatively new, though, and in its own way ironic. Quotation marks, for much of their history, represented precisely the opposite of all that chaos: They suggested, even promised, rationality and objectivity—the triumph of the written word as a means of mediating the world. They developed, the linguistic anthropologist Ruth Finnegan argues in her 2011 book Why Do We Quote? The Culture and History of Quotation, in response to the modernist notion that ideas could be separated from their authors and their speakers—and were so significant in that regard, she notes, that many have seen them as “one of the great achievements in human history.” But quotation marks’ ironized permutations are decidedly less great. Those little, hovering semicircles, doubled and curved and opened and closed, suggest not an ordered world, but its inverse: instability, uncertainty, the lack of an axis. In that, scare quotes are elegantly revealing of the moment that gave rise to them. They are the punctuation of the post-truth “post-truth” age.

Quotation marks vary, in their appearances, across languages. German has „“, and » «, and ‹ › to indicate quotation; it also, along with French, Spanish, Italian, Vietnamese, and many more languages, uses the « », or guillemets (named after the 16th-century French printer Guillaume Le Bé). Those marks, like their English counterparts, all evolved from a single origin: the ancient Greek mark known as the diple (“double”). It looked like this: >. And it was added to the margins of texts not to suggest quotation, but rather to signal significance—a kind of proto-underlining. In the same way that many scare quotes today are used, delightfully, simply to call attention to a word or phrase or name—“Happy Birthday, ‘Stephanie,’” a card will say, probably not meaning to cause poor Stephanie existential anxiety; “‘Food & Beverage,’” a sign will announce, pointing the way to the “edible” goods—the diple served to draw attention to a document’s most important words and sections. It persisted in that role for centuries, even after the advent of print. (Gutenberg’s Bible, notably, features no quotation marks.)

It was the rise of the novel in the 18th century, Finnegan argues in Why Do We Quote?—and of romanticism, with its emphasis on the value and the validity of the individual voice—that helped quotation marks to take their modern form. As literature (and, with it, literacy) spread, printers availed themselves of a graphical variation of the diple—still doubled, but with the hash marks now separated—to indicate the authors’ reporting of others’ experiences. The new marks may well have been, Finnegan notes, “a necessary part of modernization, with its ability to separate out the words of others within a logical system that facilitates abstraction and precision.” They arose with democratization—and are, in many ways, necessary for democracy. They allow people to talk to each other, and a nation to talk to itself.

Related Story

Have We Hit Peak Punctuation? :(

Not so scare quotes. The ironized version of the ancient invention is a distinctly 20th-century phenomenon. The Oxford English Dictionary’s first recorded use of “scare quote” came in 1956, from the Cambridge philosophy professor Elizabeth Anscombe, a young colleague of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s, in an issue of the journal Mind: “So nothing is or comes about by chance or ‘whichever happens,’” Anscombe wrote, of Aristotle’s text. She then clarified: “‘Whichever happens ’: the Greek phrase suggests both ‘as it may be’ and ‘as it turns out.’ ‘As the case may be’ would have been a good translation if it could have stood as a subject of a sentence. The “scare-quotes” are mine; Aristotle is not overtly discussing the expression ‘whichever happens.’”

The next year, in his Mental Acts: Their Content and Their Objects, Peter Geach, Anscombe’s collaborator (and, also, her husband), repeated the term: “There is indeed a particular tone of voice that is conventionally represented by using quotes,” Geach wrote, “as in ‘He introduced me to his “wife”’; but such quotes (which are sometimes called ‘scare-quotes’) are of course quite different from quotes used to show that we are talking about the expression they enclose.”

Geach continued: “In this work I have tried to follow a strict rule of using single quotes as scare-quotes, and double quotes for when I am actually talking about the expressions quoted.”

But then! To that last sentence the logician added a footnote: “There is very little practical risk of confusing the two uses of quotes,” Geach confessed, “so [the] reader may find this precaution rather like the White Knight’s armoring his horse’s legs against possible sharkbites. But once bitten, twice shy—I have actually been criticized in print for lack of ‘rigor’ because I used scare-quotes in a logical article without warning my readers that I was doing so.”

Scare quotes suggest that the atomic unit of democracy—the word, with a commonly understood meaning—may no longer be fully stable.

So Geach, one of the coiners of “scare quote,” warned against its misuse in the very act of coining the term. Geach tried to distinguish, graphically—single quotes meaning one thing, double meaning another—between quotes that are used simply to designate the declaration of terms and quotes that are used to signal the debate of those terms. He seemed to have anticipated, almost, how his coinage would become weaponized in the decades that followed—how scare quotes would have, as the Columbia Journalism Review noted in 2013, “exploded in recent years, being brought to bear especially in politics, as ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ campaigns used their own ‘scare’ tactics.”

Geach couldn’t have anticipated the current moment of truthiness and post-factiness and generalized political postmodernism. Yet he seems to have hazily foreseen the media outlets serving up heady, hedged reports about the emboldening of the “alt-right.” And offering heated, but also notably lukewarm, discussions of “white supremacists.” And of “identity politics.” And of “fake news.” What, exactly, do the quotes around those terms mean—and how, exactly, do they affect the words that are coddled and/or stifled in their doubling embrace? What does “fake” mean, precisely, when applied to news? Invented? Incorrect? What about “‘fake’”? When the term “alt-right” comes to the American public swaddled in ironic quotation marks, should we be soothed … or, indeed, as Elizabeth Anscombe warned, scared?

The answers are—and this is the problem—unclear. Scare quotes, used for purposes of mordancy or obscurity or something in between, are inherently ambiguous. They are ironic in the most basic sense—they say one thing while meaning another—but they are ironic, too, in a broader way: They inject doubt into the action of the saying itself. They can confuse readers, and can whiff of intellectual indolence. (“The scare quote,” Jonathan Chait wrote in The New Republic, in 2008, “is the perfect device for making an insinuation without proving it, or even necessarily making clear what you’re insinuating.”) A 2010 parody of science journalism in The Guardian summed it up like so: “In this paragraph I will state the main claim that the research makes, making appropriate use of ‘scare quotes’ to ensure that it’s clear that I have no opinion about this research whatsoever.”

Or, as Keith Houston, the author of Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, told me: “I’ve heard scare quotes described as tongs.” They allow for a kind of moral distancing—for someone to touch a contentious idea without fully engaging with it (or, indeed, getting dirty by association).

Scare quotes can also, on the other hand—invoking the “sneer” more than the “scare”—suggest partisanship on the part of the scare-quoter. To put terms like “identity politics” or “rape culture” or, yes, “alt-right” in scare quotes is not just to highlight those terms as matters of open debate, and thus to place them within the sphere of legitimate controversy; it is also to make, in that placement, a political declaration. Scare quotes can be inviting to some readers and alienating to others. In 2014, Slate declared hashtags to be “the new scare quotes” (on the grounds that both devices represent “a strategy for announcing distance”); the comparison proved apocryphal, but it did highlight the way the sharing of irony, whether by way of hovering commas or cross-hatched little lines, can signal, and serve, the niche at the expense of the collective.

When the term “alt-right” comes to the American public swaddled in ironic quotation marks, should we be soothed … or, indeed, scared?

So what’s to be done to mitigate that? One solution could be to replace the scare quote with another fraught-but-also-comparatively-less-fraught device: the hyperlink. Digital writing, instead of scare-quoting “alt-right,” could simply link to the comprehensive and nuanced definitions of the movement provided by the Southern Poverty Law Center, or the Anti-Defamation League, or even Wikipedia. They could point to this video of the alt-right in action.

Another solution could be to follow the advice of the literary critic I.A. Richards, who in 1968, a decade after Peter Geach’s attempt to streamline the meanings of quotation marks, declared that “we overwork this too serviceable writing device,” and tried to introduce more specific options into the English vernacular. (Richard offered nine iterations, all of them adopting the open-mark/closed-mark formula, including “?— ?” (indicating the sense of a query), “i — i” (indicating ambiguity), and “! — !” (indicating a tone of disbelief—the contemporary sense of the scare quote).

Or you could just adhere to the words of the Associated Press, which allows, in its guide to discussing the “alt-right,” that the term “may be used in quotes or modified as in the ‘self-described’ or ‘so-called alt-right’ in stories discussing what the movement says about itself,” but which also cautions to

avoid using the term generically and without definition, however, because it is not well known and the term may exist primarily as a public-relations device to make its supporters’ actual beliefs less clear and more acceptable to a broader audience. In the past we have called such beliefs racist, neo-Nazi, or white supremacist ….

We should not limit ourselves to letting such groups define themselves, and instead should report their actions, associations, history, and positions to reveal their actual beliefs and philosophy, as well as how others see them.

Language, certainly, evolves, and in many ways it bends toward ambiguity. So scare quotes, to be sure, are in one way simply a part of the same movement that found “literally” now meaning both “literally” and “not at all literally,” and that finds

December 22, 2016

Hallmark Holiday Movies: The Quiz

Ah, the pleasure that is the Hallmark/Lifetime holiday movie. Each film, regardless of its channel of origin, regardless of its story, regardless of its star, is holiday escapism at its purest and least apologetic. The Hallmark/Lifetime holiday film (can we just call it, as a collective unit of culture, the Halltime movie?) is a place where the culture wars have not yet dared to do battle, where “diversity” refers to trees that are decked in twinkly ornaments of both silver and gold, where women are workaholics until they are taught by men who are square of jaw and pure of intent that there is so much more to life than work.

How much do you know about the holiday movies that air each year, so reliably and so reassuringly? How much do you want to dare to know? Here’s a quiz to find out:

How Did North Carolina's Deal to Repeal H.B. 2 Fall Apart?

DURHAM, N.C.—Christmas is a time for stories about unity overcoming divisions, about miracles that can bring everyone together with a heartwarming conclusion.

This is not one of those stories.

Last week was a bruising one for North Carolina politics. After returning to Raleigh for a special session intended to pass disaster relief, the Republican leaders in the General Assembly used the occasion to ram through a series of measures to strip the incoming governor, a Democrat, of powers they had afforded the outgoing governor, a Republican. It was brazen power politics, a fact the GOP didn’t dispute, and it brought widespread national disapprobation on the state.

This week started out looking more positive: There were signs of a deal to repeal H.B. 2, the “bathroom bill” that had fiercely divided the state and produced hundreds of millions of dollars in economic losses. In February, the city of Charlotte passed an ordinance barring LGBT discrimination, including a provision that mandated that transgender people be allowed to use bathrooms corresponding with the sex with which they identify. The GOP-led General Assembly quickly called a special session in which it barred cities from passing LGBT nondiscrimination ordinances (or, for good measure, higher minimum wages), and mandated that transgender people use bathrooms corresponding to the sex on their birth certificate in any public facilities. The law set off boycotts, protests, and acrimony, and is one reason Governor Pat McCrory, a Republican, lost his bid for reelection last month.

On Monday morning, with no advance warning, Charlotte’s city council convened and (reportedly) passed a repeal of the offending ordinance, contingent on the General Assembly repealing H.B. 2. Governor-elect Roy Cooper, a Democrat, issued a statement saying that the GOP leaders in the General Assembly had promised him they’d convene a special session on Tuesday to fully repeal H.B. 2. Cooper had reportedly also lobbied city-council members to repeal the ordinance.

It was a big gamble for the governor-elect: If he won, he would have his first major victory under his belt even before he was sworn in, slaying an unpopular law. But to do that, he had to rely on the same GOP leaders who had stealthily hatched a plan to strip Cooper of his gubernatorial powers the week before.

The first sign that Cooper’s gamble might be ill-advised came Monday afternoon, when Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger and House Speaker Tim Moore issued a joint statement. “For months, we’ve said if Charlotte would repeal its bathroom ordinance that created the problem, we would take up the repeal of H.B. 2,” they said. “But Roy Cooper is not telling the truth about the legislature committing to call itself into session—we’ve always said that was Gov. McCrory’s decision, and if he calls us back, we will be prepared to act. For Cooper to say otherwise is a dishonest and disingenuous attempt to take credit.”

Though Cooper had initially said the General Assembly would meet Tuesday, the special session was pushed back to Wednesday. Even before the meeting occurred, pessimism began to well up. Republicans hold large majorities in both houses of the legislature, and it was not clear that there were GOP votes for repeal in both chambers—or even in either one. That meant leaders would either have to rely on Democratic votes or, more likely, caveat “full repeal” to win Republican votes.

There was trouble in Charlotte as well. First, the city council may have violated public-notice laws with its sudden meeting, which is one reason that it was not immediately apparent that rather than repeal the whole ordinance, the council had only repealed the bathroom provision. Second, the city risked arousing the legislature’s ire, both by making their repeal contingent on H.B. 2 repeal, and with a statement in which the council more or less promised to just pass the same ordinance again once H.B. 2 was gone. “The City of Charlotte is deeply dedicated to protecting the rights of all people from discrimination and, with House Bill 2 repealed, will be able to pursue that priority for our community,” members said in a statement. Members of the Durham city council also said they would quickly pass nondiscrimination bills as soon as H.B. 2 was repealed.

Christmas is also a time to celebrate faith, but by Wednesday, the only faith on hand was bad, with Charlotte distrustful of the General Assembly, and the General Assembly distrustful of Charlotte. Nonetheless, on Wednesday morning Charlotte’s city council met again and fully repealed the city’s ordinance, this time without a contingency clause.

By the time the General Assembly gaveled into session in Raleigh, tempers were high and hopes were sinking. It took quite some time for anyone to introduce a bill to actually repeal H.B. 2. A Republican legislator argued, apparently with a straight face, that the whole special session was unconstitutional, since they could just put the whole thing off until next month. He wasn’t wrong, but it was exactly the same argument that Democrats had made to object to the special session stripping Cooper’s powers last week.

Finally, Democrats introduced a simple bill that repealed H.B. 2. Republicans, with their large majority, ignored it and filed their own bill, which repealed H.B. 2 but also created a “cooling-off” period in which cities would not be allowed to pass any new ordinances on employment activities or public shower and bathroom accommodations.

Democrats were furious, saying the moratorium was a violation of the original deal, which was full repeal. What was even the point of repealing the law if cities still couldn’t pass the ordinances they wanted to? Debate on the Senate floor devolved into ad-hominem attacks. It started to appear that even with the moratorium, Republicans didn’t have the votes to pass the repeal. After all, many GOP members of the legislature still think H.B. 2 was a good idea.

Just before 7 p.m., Berger offered a last-ditch idea: He’d divide the bill into two parts, with separate votes on repeal and on the cooling-off period. But the senate soundly rejected the repeal part. That was the end of the road. The senate couldn’t pass anything, and the house adjourned without even voting.

It’s unclear what happens now. While some of North Carolina’s political embarrassments over the last year—from passing H.B. 2 to the stripping of gubernatorial powers—are clearly Republican affairs, Wednesday’s acrimonious saga ends with everyone looking bad. Cooper now limps toward his governorship looking weaker after his big push fell apart. The state remains saddled with a law that is unpopular with voters, economically costly, and nationally embarrassing. The failed special session will likely poison the well in any repeal attempt going forward. Perhaps Charlotte, bitter over the General Assembly reneging, will decide to re-enact its ordinance, even if it’s still superseded by state law.

This year in North Carolina politics has been especially cringeworthy: In addition to H.B. 2, there were federal court rulings that deemed a state voting law blatantly racist and a state redistricting plan unconstitutional; political rallies where protesters were punched; a bitter governor’s race that dragged on for nearly a month of pointless recounts; and then the special session to undermine Cooper. It only seems fitting that the state’s politicians should manage to squeeze in a final embarrassing fiasco before the year ended. There are still 10 days left, though, so there might be time for one more.

And, Scene: Everybody Wants Some!!

Over the next two weeks, The Atlantic will delve into some of the most interesting films of the year by examining a single, noteworthy moment and unpacking what it says about 2016. Today is Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!! (The whole “And, Scene” series will appear here.)

When it was released in March, Everybody Wants Some!! may have seemed desperately out of step with the moment. Set in 1980, at the dawn of the Reagan era, Richard Linklater’s film (billed as a “spiritual sequel” to his Dazed and Confused) follows the exploits of a college baseball team over a weekend as they go to parties, hit on women, trade philosophical observations through a haze of bong smoke, and generally try to have a no-strings-attached good time. They succeed on all counts. Linklater’s bet—that viewers would care about the frivolous antics of these overflowing fountains of testosterone—was a pretty risky one.

But there’s something special about Everybody Wants Some!! (so-named after the Van Halen song that is the centerpiece the film’s spectacular soundtrack): a strangely egalitarian sense to the gang’s low-stakes capers. They mingle with every social clique—jocks, fraternity brothers, punks, theater kids—but do so on the group’s terms. If the main characters get rejected by a woman, they take it in a stride; their baser energies are directed toward competitive sports and healthily mocking each other. No scene more sums up the film’s simple joys than the scene when, during a beer run, The Sugarhill Gang’s pioneering 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight” comes on the radio, and everyone starts to rap along.

The new pitcher Jake Bradford (Blake Jenner), the star of the film, is sitting in the backseat with Dale (J. Quinton Johnson) and Tyrone (Temple Baker). Kenny (Ryan Guzman) is driving while the energetic Finn (Glen Powell), who’s clearly been at school for more than a few years now, launches into the song’s first verse. “See, I am Wonder Finn, and I’d like to say hello,” he haltingly raps, subbing in his own name for Wonder Mike’s. “To the black to the white, the red and the brown / The purple and yellow.”

Dale is the only African American in the car, but there isn’t a hint of awkwardness for any of the characters. For the 2016 audience, Finn’s rapping might feel more strange if he weren’t so carefree. Quickly, everyone in the car joins in, and the scene goes on for a hilariously long time, with everyone taking one of the many solos in “Rapper’s Delight.” It’s the kind of scene that starts out fun, starts to feel weird the longer it lasts, and then loops back around to being fun again. The moment underlines the appeal of Everybody Wants Some!!’s ensemble—their lack of self-awareness only adds to their charm.

The film is an autobiographical work for Linklater, who attended a Texas college on a baseball scholarship. He’s said the film’s depiction of race relations was intended to echo his own experience of an America that he perceived, from an admittedly limited perspective, as far less divided. As such, Everybody Wants Some!! is a portrait of an innocent time that may never have quite existed, though the fantasy offers a powerful point of contrast.

“It was the end of the ’70s. Anything that smacked of racism felt so dumb, from a different era. It’s pre-Reagan, pre-‘welfare queen.’ Reagan turned the clock back on racism,” Linklater said in an interview with Buzzfeed. “You know, when Reagan announces his presidential candidacy in Philadelphia, Mississippi—as we know, the home of the [Freedom Summer] murders—talking about states’ rights, he’s declaring: We’re going backwards. And they did! Between that and the Moral Majority, there we are today.”

To Linklater, America is getting more divided, and his films have become increasingly nostalgic as a result. The Reagan-era politics he decried have snowballed into daily insults from the country’s president-elect and a newly amplified discussion about racism. It’s no accident that 2016 feels far more fraught than Linklater’s backward-looking stories, though perhaps the dissonance can be instructive for viewers today. But even if you consider it as a bit of pure period escapism, Everybody Wants Some!! works beautifully.

Previously: Mountains May Depart

Next Up: The Lobster

December 21, 2016

Sing, a Sad Meditation on Show Business, for Kids

Midway through Sing, while the plot is limping dejectedly through its motions, you may find yourself wondering what, exactly, is happening. Was this sad but honest meditation on the fickle nature of show business originally pitched as being quite so bleak? Was it always supposed to be animated? Was it intended to be a kid’s movie? Is that why all the characters are animals? Is that Scarlett Johansson playing a crested porcupine punk-rocker in an emotionally abusive relationship? Is this the best work Matthew McConaughey’s done in years?

The concept of the movie is so baffling that it seems to have been cobbled together, madlibs-style, from pieces of other projects, and girded with a bewildering array of A-list actors who mistook filming for a hazy karaoke night at Reese Witherspoon’s ranch in Ojai. McConaughey plays Buster Moon, a producer and a koala, whose beloved theater is crumbling due to a series of ill-advised flops. In a wild attempt to save it, he decides to stage a singing competition, offering a grand prize of $1,000 to the winner. But his assistant, a myopic iguana (Garth Jennings, who also directed), accidentally adds two zeros to that figure on promotional posters, resulting in a stampede of mammals all after the cash winnings, which don’t exist, and a quandary for Buster, who’s broke.

The auditions, nevertheless, bring him a motley crew of wannabe stars: Rosita (Witherspoon), a neglected housewife who’s also a pig; Ash (Johansson), the aforementioned punk-rock porcupine; Mike (Seth MacFarlane), a mean and arrogant mouse; Johnny (Taron Egerton), a gorilla with a soft heart; and Meena (Tori Kelly), an elephant who suffers from crippling stage fright. There are inevitable complications, most prompted by the fact that Buster is a terrible producer whose plan for redemption is a show featuring amateurs covering Stevie Wonder.

Sing gathers some much-needed momentum in the third act, mostly because it’s the only part that really features singing. Rather than follow the time-tested model of movie-musicals, which parcel out big numbers throughout the film to keep the audience engaged, Jennings lumps all his together in one big medley, piling Elton on top of Sinatra on top of Taylor Swift. This is the point where you might realize they only rehearsed fragments of Carly Rae Jepsen and Katy Perry in order to keep (the still estimable) licensing costs down. You might also imagine our Lady of Swift herself hitting up Moon Theatre with a cease-and-desist order given that her biggest hit of 2015 is being performed live onstage by an overweight German pig (Nick Kroll) wearing a tiny spangled leotard.

Much more baffling than the main plot of Sing is the world Jennings visualizes: a geographically accurate version of Los Angeles in which animals live in harmony, koalas are American, and gorillas are British. The computer-animated scenes of Beverly Hills mansions and suburban streets are filled with eye-catching detail, but there’s still no good reason for the abundance of species other than the fact that Zootopia was such a big hit. The conceit hums with questions, but also missed opportunities. Why have a sheep sing a Seal song? Why is Mike a mouse, given that his oeuvre is so exclusively Rat Pack songs? How come instruments are scaled to fit the differently sized animals but microphones are one-size-fits-all?

Sing is Jennings’s first major feature since 2005’s A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. As one half of the duo Hammer & Tongs, he’s directed a variety of music videos, including Blur’s “Coffee and TV,” which was an ingenious animated short about a milk carton looking for a missing person. So it’s strange that Sing feels so uninspired. It doesn’t seem like a concept intended to resonate particularly with kids (the ones in the screening I attended laughed exactly twice, both times at fart jokes), or one that’s sly enough to wink at all the adults in the room. It does feel like a jukebox musical without a theme. McConaughey gives Buster some unexpected pep as a character, but Sing is more half-hearted cover than genuine smash hit.

Sing, a Sad Meditation on Showbusiness, for Kids

Midway through Sing, while the plot is limping dejectedly through its motions, you may find yourself wondering what, exactly, is happening. Was this sad but honest meditation on the fickle nature of showbusiness originally pitched as being quite so bleak? Was it always supposed to be animated? Was it intended to be a kid’s movie? Is that why all the characters are animals? Is that Scarlett Johansson playing a crested porcupine punk-rocker in an emotionally abusive relationship? Is this the best work Matthew McConaughey’s done in years?

The concept of the movie is so baffling that it seems to have been cobbled together, madlibs-style, from pieces of other projects, and girded with a bewildering array of A-list actors who mistook filming for a hazy karaoke night at Reese Witherspoon’s ranch in Ojai. McConaughey plays Buster Moon, a producer and a koala, whose beloved theater is crumbling due to a series of ill-advised flops. In a wild attempt to save it, he decides to stage a singing competition, offering a grand prize of $1,000 to the winner. But his assistant, a myopic iguana (Garth Jennings, who also directed), accidentally adds two zeros to that figure on promotional posters, resulting in a stampede of mammals all after the cash winnings, which don’t exist, and a quandary for Buster, who’s broke.

The auditions, nevertheless, bring him a motley crew of wannabe stars: Rosita (Witherspoon), a neglected housewife who’s also a pig; Ash (Johansson), the aforementioned punk-rock porcupine; Mike (Seth MacFarlane), a mean and arrogant mouse; Johnny (Taron Egerton), a gorilla with a soft heart; and Meena (Tori Kelly), an elephant who suffers from crippling stage fright. There are inevitable complications, most prompted by the fact that Buster is a terrible producer whose plan for redemption is a show featuring amateurs covering Stevie Wonder.

Sing gathers some much-needed momentum in the third act, mostly because it’s the only part that really features singing. Rather than follow the time-tested model of movie-musicals, which parcel out big numbers throughout the film to keep the audience engaged, Jennings lumps all his together in one big medley, piling Elton on top of Sinatra on top of Taylor Swift. This is the point where you might realize they only rehearsed fragments of Carly Rae Jepsen and Katy Perry in order to keep (the still estimable) licensing costs down. You might also imagine our Lady of Swift herself hitting up Moon Theatre with a cease-and-desist order given that her biggest hit of 2015 is being performed live onstage by an overweight German pig (Nick Kroll) wearing a tiny spangled leotard.

Much more baffling than the main plot of Sing is the world Jennings visualizes: a geographically accurate version of Los Angeles in which animals live in harmony, koalas are American, and gorillas are British. The computer-animated scenes of Beverly Hills mansions and suburban streets are filled with eye-catching detail, but there’s still no good reason for the abundance of species other than the fact that Zootopia was such a big hit. The conceit hums with questions, but also missed opportunities. Why have a sheep sing a Seal song? Why is Mike a mouse, given that his oeuvre is so exclusively Rat Pack songs? How come instruments are scaled to fit the differently sized animals but microphones are one-size-fits-all?

Sing is Jennings’s first major feature since 2005’s A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. As one half of the duo Hammer & Tongs, he’s directed a variety of music videos, including Blur’s “Coffee and TV,” which was an ingenious animated short about a milk carton looking for a missing person. So it’s strange that Sing feels so uninspired. It doesn’t seem like a concept intended to resonate particularly with kids (the ones in the screening I attended laughed exactly twice, both times at fart jokes), or one that’s sly enough to wink at all the adults in the room. It does feel like a jukebox musical without a theme. McConaughey gives Buster some unexpected pep as a character, but Sing is more half-hearted cover than genuine smash hit.

The Lena Dunham Cycle of Internet Outrage

On Tuesday, news outlets from New York magazine to Fox News to Man Repeller to Pop Sugar found some celebrity news to share: Lena Dunham, during the latest episode of her podcast Women of the Hour, had made a comment about abortion that was … not in good taste. The episode, “Choice,” was meant to highlight the idea that, as Dunham put it in her introduction to the episode, “it’s your body, and you choose the best look for it at every stage of your life.” But Dunham, introducing one of the women who would share her story in the episode, started with a confession: She was a little bit of a hypocrite, she suggested. Telling the story of a visit to a Planned Parenthood in Texas, she recalled how she had wanted to make clear to the people there that “as much as I was going out and fighting for other women’s options, I myself had never had an abortion.”

The tone of all this was confessional. It was, after all, a podcast. And it was, after all, Lena Dunham. The problem came when, after admitting the work she still wanted to do to de-stigmatize abortion in her own mind, Dunham concluded: “Now I can say that I still haven’t had an abortion, but I wish I had.”

Dunham is a reminder of how thin the line has become between the world of entertainment and the world of “everything else.”

And, with that, Dunham—a young woman who is in the enviable position of being a celebrity, and who is in the unenviable position of being a celebrity in 2016—became the stuff, once again, of controversy. In this case, by giving voice to some of the American political right’s worst caricatures of the American political left. News outlets jumped on the story, using Dunham’s “I wish I had” in their headlines. People on Twitter and Instagram seethed, many of them taking it upon themselves to inform Dunham, on those same platforms, that perhaps she herself should have been aborted. “Lena Dunham is having her ass handed to her right now on the internet,” Man Repeller summed it up. And so, late on Tuesday, Dunham took to Instagram—specifically, to a caption for an image she posted of the word “Choice” scrawled in chalk on a blackboard—to offer an apology:

My latest podcast episode was meant to tell a multifaceted story about reproductive choice in America, to explain the many reasons women do or don’t choose to have children and what bodily autonomy really means. I’m so proud of the medley of voices in the episode. I truly hope a distasteful joke on my part won’t diminish the amazing work of all the women who participated. My words were spoken from a sort of “delusional girl” persona I often inhabit, a girl who careens between wisdom and ignorance (that’s what my TV show is too) and it didn’t translate. That’s my fault. I would never, ever intentionally trivialize the emotional and physical challenges of terminating a pregnancy. My only goal is to increase awareness and decrease stigma.

Thus, another revolution in a cycle that has become extremely familiar: Lena Dunham says something that offends people; Lena Dunham apologizes; Lena Dunham carries on. Sometimes the process will feature one more element (Lena Dunham learns a valuable lesson); the basics, though, will be the same in their ebbs and flows. Dunham is, with all this, engaging in an age-old ritual: She is doing the sacred stuff of young personhood, which is to say making mistakes and correcting them, over and over again—but she is carrying them out in public.

That’s why Dunham’s “delusional girl” explanation rings hollow. While Dunham, the writer and actor and creator, may have a persona, in the broadest, Goffmanian sense, her particular strain of celebrity is based on her apparent impatience with the notion of “persona” itself. She’s free-wheeling. She’ll, you know, go there. She is someone who, for better or (occasionally) for worse, insists on presenting the “realest” possible version of herself, for all the world to see.

Related Story

How Disappointment Became Part of Fandom

Which means on the one hand that, sure, a headshot of Dunham might as well accompany the term “overshare” in the dictionary. But it also means that Dunham has framed herself, repeatedly, not just as a role model for young feminists—via Girls; via Lenny Letter, her newsletter; via Not That Kind of Girl, her memoir; via a podcast titled, yes, Women of the Hour—but also as a political advocate. She appeared at the Democratic National Convention this summer, making an impassioned speech for the potential presidency of Hillary Clinton. She is outspoken in her defense of Planned Parenthood and reproductive rights. She is the emblem, personified if not fully persona-ed, of how thin the line has become between “entertainment” and “everything else.”

Dunham isn’t alone in that, of course. There’s Beyoncé, whose art, increasingly, doubles as political exhortation. There’s Solange, whose art is doing the same. There’s #kanye2020. There’s Amy Schumer, who also campaigned for Hillary, and who, on top of that, lobbies for gun safety, gives speeches about body positivity, and stars in politics-themed Bud ads. There are approximately 250 others. Celebrities have long held political power, via the attentional affordances of fame; now, though, they are exercising it not just as before, in the pages of People and on the stages of awards shows, but also on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram. They are famous in the holistic manner of the internet, mixing artistic creation and personal revelation and political messaging into presences that double as brands.

Their words are an important part of those brands—because celebrities are living, like the rest of us, in a world in which every comment can be made, so very easily, into sharable media. In that world, especially where celebrities are concerned, a podcast will be a conversation, until suddenly it’s a broadcast. A gaffe will be a gaffe, until suddenly it’s a news cycle-long matter of debate.

That’s the new way of celebrity, and it’s one that Dunham, to her credit if also, sometimes, to her detriment, seems to be embracing. She seems to see herself not just as a writer or actor or public figure, but also as—perhaps foremost as—a political advocate. So the real mistake she made this week, in her telling of it, was to let the acting—the stuff of the “‘delusional girl’ persona”—infiltrate too much into the other stuff. In her Instagrammed apology, the young celebrity best known for her TV show concluded her message with a direct address to “the women who have placed their trust in me.” “You mean everything to me,” Dunham told them. She added: “My life is and always will be devoted to reproductive justice and freedom.”

Dunham sounded like a woman who had learned her lesson. She also sounded like a politician.

The Best Books We Missed in 2016

“So many worthy books, so little space.”

I type those words all too often, as I wrote in this space last year, and the year before, when the list-making season arrived—and nothing has changed this year. So I’ll sigh once more over the predicament. Again and again, I have to deliver some version of that message to the many publicists who excitedly email me about the rich season of titles ahead. I tell reviewers, eager to share their views of this or that author’s latest effort, the same thing. Ditto authors themselves, a surprising number of whom come right out and ask: Can they expect any coverage in The Atlantic? The phrase, as I’ve admitted before, is sometimes a white lie, yet always the truth, too: We have room for only 30 or so book pieces a year in the Culture File. That means an awful lot of notable books go unnoticed by us.

In the holiday spirit, now is a moment to mention a sampling of 2016 books we wish we hadn’t missed—including two that my colleague Sophie Gilbert had hoped to write about. (So many worthy books, so little time!) And the brand new culture editor on our digital side, Jane Yong Kim, weighs in on poetry, a genre we’ve been especially remiss in attending to. We’ve asked their authors to pay it forward, and single out a few books themselves. What recent work has caught their expert eye? What book, however old, helped them write the one they’ve been busy promoting? —Ann Hulbert

Fiction

George Baier IV / Penguin / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

One of the questions Mona Awad’s 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl prompts, through a series of vignettes about the same woman, is how rich life might be if all the energy women expended in service of skinniness could be redirected toward more life-affirming pursuits. In high school, Lizzie is already conscious of her size, becoming more acutely so with every personal relationship. Later, as Beth, she starves herself into submission. But it’s as Elizabeth, married, slender, and miserable, that the toxicity of her obsession becomes most apparent. Awad tells Lizzie’s story from a variety of different perspectives and in different scenes, some deeply funny, some dreamlike, many tragic. Throughout, her prose is lively, while her insight into the often-baffling complexities of being a woman is touching and sharp. —S.G.

Vintage / House of Anansi

Mona Awad: Teva Harrison’s In-Between Days is an extraordinary graphic memoir about the author’s struggle with metastic breast cancer. Combining text and image, Harrison navigates the complex terrain of living with terminal illness in an intimate, honest, and remarkably brave voice that moved me deeply. The illustrations are particularly stunning, ranging from poignant titles like “Cancer Fraud” and “Trying on Small Talk” to truly heartbreaking ones such as “What I Want” and “Cancer Doesn’t Care.” There is great humor, vulnerability, fear, pain, life, love, and hope here. Like the greatest memoirs, Harrison goes right into the dark spaces and, in doing so, lets in the light.

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis really made an impression on me, though I can’t say that I was consciously aware of it as an influence when I was working on my book. I think it’s a brilliant, very disturbing, and complicated portrait of a monster, who is at the same time a product of his culture and his age. Certainly my main character, Lizzie, is no Patrick Bateman, but I do think I was interested in exploring a kind of monstrousness, a psychosis that our body-image-obsessed culture can bring out in us. Another favorite is The Remains of The Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. Not only is it a wonderful story with an incredibly rich and nuanced first-person voice, but I love the way Ishiguro can create a narrator who is so blind to certain truths inside himself, truths that are available to the reader to recognize, but that the narrator can’t access due to his own psychological and emotional blinkers.

Criticism

Roderick Aichinger / Pantheon

In a fall when so much political commentary has so quickly come to look dated and deluded, it is especially thrilling to read cultural commentary that spans more than a decade and is anything but. Mark Greif writes in his preface that as a child “I taught myself to overturn, undo, deflate, rearrange, unthink, and rethink.” That protean persistence of mind drives his essays, most of which first appeared in n+1, the journal he founded in 2004 with friends. His title may suggest obstreperousness, but Greif is above all fiercely curious. Whether he has the notorious Octomom in his sights, or our obsession with exercise, or confrontations with the police, he delivers insights about 21st-century America that will take you by surprise. As a guide to “what we call ‘experience’ today and what we name ‘reality,’” as he puts it, Greif will help you unthink and rethink, and who doesn’t need to do that? This gathering of his essays could not be better timed. —A.H.

FSG / Punctum / Routledge / Scribner

Mark Greif: The best novel I read this year—Aravind Adiga’s Selection Day—was published in England and Europe, but won’t come out in the U.S. until January. In its primal triangle of rival brothers and a maniacal father, hell-bent on success in cricket in India, Adiga grips the passions while painting an extraordinary panorama of contemporary sports, greed, celebrity, and mundanity. As a literary master, Adiga has only advanced in his art since his Booker Prize-winning The White Tiger. Reaching back to books that could easily be missed because they came out just as 2015 was ending, I really admired Lester Spence’s sharp and mind-changing Knocking the Hustle: Against the Neoliberal Turn in Black Politics, a volume that’s both personally acute and analytically profound about black life and black insurgency in contemporary America. I’d recommend it to everyone. And a book that came out at the start of 2016, Ben Ratliff’s crystalline Every Song Ever, likewise dug under familiar categories of description—here, from aesthetics and music criticism—to open the reader’s eyes to truer visions of our artistic situation and experience.

As for older books that influenced me in writing Against Everything, there’s a long list of writers and thinkers to whom I wish I could pay tribute. But from within the literature of police sociology I read for my chapter on “Seeing Through Police,” let me just single out for praise the theorist and ethnographer Peter K. Manning, whose Democratic Policing in a Changing World (2010)—one exemplary title from his long career of superbly illuminating writings on police, security, and surveillance—would still be transformative reading for anyone who worries about police power and police integration into a fairer and better democratic social fabric.

Poetry

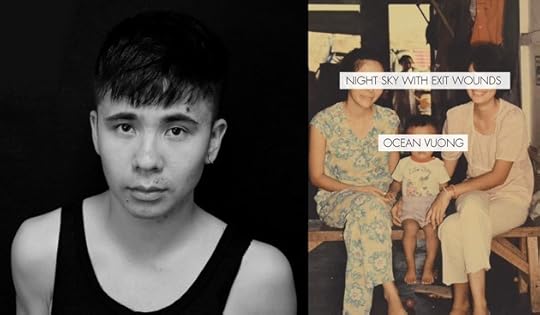

Peter Bienkowski / Copper Canyon Press

Ocean Vuong’s poems trace the sometimes messy contours of a life born of conflict and trauma, of a body animated by the love of mothers and strangers. Pulling from his family’s harrowing recollections of the Vietnam War, and from his own charged adolescent memories, he experiments confidently with different ways of expressing yearning. He places his subjects in bomb craters, on baseball fields, and even inside a ship-in-a-bottle, crafting live-wire imagery (“this is how we loved: a knife on the tongue turning into a tongue”) that gets at how weapons can be internalized, or foreign objects made familiar. Vuong, a 2016 Whiting Award winner, seems keenly aware of love as both a cost and an enduring extract of violence. His collection this year, with its impassioned pulse and shifting micro-geographies, offered me a radiant dose of just that insight. —J.Y.K.

HarperCollins / Wesleyan

Ocean Vuong: The book that remains on my desk, even after many re-readings, is Peter Gizzi’s Archeophonics, a National Book Award finalist this year and, arguably, his most ambitious and wildly thrilling achievement to date. The poems explore the world via sound: the way it disperses from an epicenter, touching hard surfaces only to return as an echo—changed, enriched, and bearing a history. “I’m just visiting this voice,” Gizzi begins, and throughout the collection it’s this notion of a transient self and of shifting speech that gives these poems their urgent currency. I have been carrying Archeophonics with me these past few months not as mere balm, but also as a trusty companion that might brush up against my own hard edges: “The old language is / the old language. It don’t mean shit. // It’s not where you begin / it’s how you finish.” For Gizzi, as long as language is used and rearranged, it can, despite its contradictions, pave a way forward and fashion an affirming architecture for the present. “I make sounds,” he writes, “[then] forget to die. I call it living.”

My family has a long history of learning disabilities, particularly dyslexia, and I myself came to reading quite late. But at 11, finally able to read at length on my own, I found the Scary Stories series by Alvin Schwartz. What immediately stunned me about the three volumes was how grotesque and surreal they were (despite their fourth-grade reading level). In one story, a boy, while digging in his backyard, finds a toe sticking out of the dirt. When he shows it to his mother she, without hesitation, tosses it into the pot of soup she’s making. The family goes on to eat the toe at dinner as though nothing is out of the ordinary. I learned later why I had such a strong connection to these stories. Schwartz had scoured books of folklore, collecting ghost stories and urban legends, some of them centuries old and originating from oral traditions. Because of its graphic nature, the series was, for years, at the top of the American Library Association’s list of most challenged books. But I grew up in a house rich with storytelling and Schwartz’s tales, in all their visceral, enigmatic brutality, echoed the ones my grandma used to tell of Vietnam. While I was writing Night Sky With Exit Wounds, these stories resurfaced as vital players from my formal reading education, serving as a testament to the imagination’s potential to transform violent and discordant histories into art.

Biography

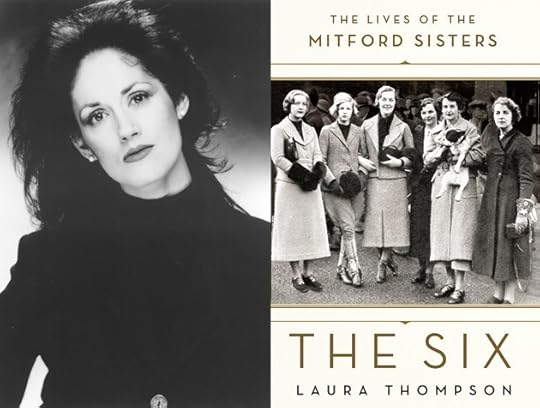

Richard Blower / St. Martin’s Press

I kept wondering, reading Laura Thompson’s The Six, what the Mitford sisters might look like if they were coming of age in the 21st century rather than in the 1930s. Thompson’s meticulously researched, elegantly written book is a thorough history of one of England’s most eccentric families, gratifying to both Mitford enthusiasts and puzzled newbies. You might be familiar with Nancy, the eldest, and the author of Love in a Cold Climate and The Pursuit of Love, in both of which she sketched a hazily autobiographical account of her oddball childhood. But then there’s Diana (left her lovely husband for Oswald Mosley, head of the British Union of Fascists), Unity (friend of Hitler), Jessica (communist), Deborah (duchess), and Pamela (the quiet one). Thompson rifles through every skeleton in the Mitford closet while treating her subjects with great sympathy, even in their ugliest moments. It’s an artful history of a most enthralling family. —S.G.

Laura Thompson: Truthfulness is a peculiarly precious concept in these days of fake news, fake sincerity, and fake thought, which is why I particularly treasure the writing of Rachel Cusk. In both her novels and nonfiction she is fearless in saying what she means, rather than what readers might want to hear. She has been excoriated in some quarters for her books about motherhood (A Life’s Work) and separation (Aftermath), but the hysteria that she stirs up is of course a tribute to her honesty.

FSG

Her latest novel, Transit, is my book of 2016. It follows the brilliant Outline in being a series of encounters between the narrator—a writer, intermittently visible as she goes about her ordinary business—and assorted characters who in different ways offer her their story. That’s it. It is, as I see it, a literary quest to fathom the mystery of how to live. What is extraordinary is how this produces something so readable. Cusk is an admirer of D.H. Lawrence (as am I) and although, on the face of it, her extreme rigor with words couldn’t be more different from his vivid splurging prose, she has the same gift of making the numinous into something concrete.

I tend to prefer nonfiction that’s written by novelists. They know how to tell a story, what to emphasize and what to leave out. Nancy Mitford—also pretty fearless, beneath the aristocratic politesse—was a wonderful historical biographer, notably of Madame de Pompadour and Louis XIV, because she deployed all the same gifts that she used in her fiction: the entrancing authorial voice, the firm grasp of human motivation, the narrative flow into which research was so easily absorbed. So when writing my book about the Mitford sisters, I had Nancy in my head, not just as subject matter but as delightful inspiration. Rather as she, in turn, had been inspired by the words of her own biographical subject, Voltaire, who once wrote, “The secret of being a bore is to tell everything.”

[image error]

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower