Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 294

November 18, 2015

The Flourishing Black Market in Syrian Passports

Who was Ahmad al-Mohammad?

Was he one of the suicide bombers in Friday’s attacks on Paris who was found with his passport near his body? Or was he a man with the same name—and same passport details—who was arrested Saturday at a Serbian refugee center?

It may turn out neither man was named Ahmad al-Mohammad, and, in fact, there may be several others in Europe with the same name and identical passport details. Indeed, Agence France-Presse reported Wednesday that Ahmad al-Mohammad was born in 1990, served as a soldier in the Syrian army, and died months ago. The passport, AFP reports, bore his details.

The Syrian civil war, and the refugee crisis it has created, has spawned a black market in fake Syrian passports. These documents are highly sought after by Syrian refugees desperate to leave their country, migrants from other nations hoping to enter Europe posing as Syrians, and, apparently, militants who use them to enter Europe for operations such as the attacks on Paris last Friday.

Indeed, even before Friday’s attack, Frontex, the European Union’s border agency, had warned of the proliferation of fake Syrian passports, pointing out that many who possessed them were economic migrants rather than Syrians fleeing civil war.

“There are people who are in Turkey now who buy fake Syrian passports because they know Syrians get the right to asylum in all the member states of the European Union,” Fabrice Leggeri, the head of the agency, told Europe 1, a French radio station, in September.

“People who use fake Syrian passports often speak Arabic,” he added, in comments translated by Agence France-Presse. “They may come from North Africa or the Middle East but they have the profile of economic migrants.”

But Ewa Moncure, a spokeswoman for the agency, told NPR later that month that most of those who sought the documents were in fact victims of the Syrian Civil War. She said:

Well, they are coming from a war-torn country. Probably many had to leave their homes rather quickly. Maybe some didn’t have passports, and obtaining a Syrian passport right now—it’s probably extremely difficult. Many Syrians whom we are seeing in—for example, in Greece right now—have been living … either in Syria but also in camps in Turkey, Lebanon, or Jordan, and they are coming from these camps. These are people who’ve been on the move, sometimes for several years. These are people who some of their children were born outside Syria.

Indeed, as Turkey’s disaster and emergency-management department reported in 2013, only 30 percent of Syrians who entered the country had valid passports. The conflict has only gotten worse since then, creating, in all, more than 4 million refugees, half of whom live in Turkey. This summer, as Europe loosened its rules for Syrian refugees, Syrian passports became a valuable commodity because its holders were automatically accorded protected status.

“Any Arab resident dreams of living in a European country, and they are taking advantage of this wave of forging to get fake documents and pretend they are Syrians,” a Turkish middleman told The Wall Street Journal.

Journalists across Europe have highlighted the ease with which false Syrian passports can be obtained.

Dutch journalist easily buys #fake #Syrian #passport on behalf of the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutten v @Sjon_m pic.twitter.com/pljeWBp1rn

— Elijah J. Magnier (@EjmAlrai) November 14, 2015

The Telegraph reported that for migrants looking to enter Europe, a “quick tap on their smartphone takes them to The Travellers’ Platform, a Facebook page that provides the answers to all their needs.” The cost of a false passport and a trip from Turkey to Greece: about £2,000 ($3,000).

The quality of those passports vary. Some are printed on actual Syrian passports that were stolen, making them seem more authentic. The holders of poorer quality fakes are often stopped in Europe, but are sometimes met by sympathetic officials. One refugee who managed successfully to enter Europe recounted to Reuters the experience of his friend who tried using a bad fake ID to board a plane in Greece.

“The airport lady said to them, literally, ‘Try again,’” he said.

Leggeri, the head of Frontex, said in September that there was no evidence fake passports had been used by potential terrorists to enter Europe.

But Sky News reported as far back as February that foreign fighters “seeking to join Islamic State are using black-market Syrian passports to enter through Turkish border checkpoints.” They now appear to be using them to enter Europe.

A commander for the Islamic State told the Journal that Iraqi and Palestinian militants with the group had used Syrian passports to travel through Turkey. They were taught the dialect of the Syrian town or region listed on their passport, he said, in case they were questioned.

One of those men seems to have crossed into Europe and, eventually, France where he blew himself up on Friday. It’s unclear if we’ll ever know who he was.

Does ‘American Art’ Exist Anymore?

Every other year since 1895, the Venice Biennale has served as an international stage for some of the most interesting, daring artists working today. You might expect the Biennale to be a place where signs of nationalism abound in some form or another: After all, artists undergo a rigorous selection process by their respective countries before they’re sent to essentially compete against their foreign counterparts. (A jury awards a gold medal, the Golden Lion, to the best artist at the fair.)

The event, often referred to colloquially as the “Art Olympics,” is coming to a close this week, but not before making it abundantly clear how little nationalism matters anymore to one pavilion: the American one. Since 2000, the U.S. pavilion has largely featured apolitical works, with many artists finding burdensome implications in the association of their work with their home country. This raises the question: In 2015, what makes art distinctly American?

Indeed, the Biennale reflects a long-simmering shift in contemporary art. Many curators of American museums say they’re moving away from traditional definitions: In the past, the label has been more actively used to decide who does and doesn’t belong in the country’s cultural history. But art reflects identity, and the U.S. national identity has only grown more pluralized in recent decades, thanks to immigration and globalization. As a result, U.S. art museums today are embracing a new, more inclusive use of the “American art” label—one that better captures the rich, cross-cultural influences shaping the country’s artistic output in the 21st century.

“We open our doors very wide,” says Virginia Mecklenburg, the chief curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.—the closest thing the U.S. has to an art museum of national record. “There are many people who remain citizens of their home country, but have an enormous impact on American art and culture.” She points to a forthcoming fall 2017 exhibition of the Mexican semi-abstract painter Rufino Tamayo, who represented his home country at the 1950 Biennale but who worked and taught in New York for 14 years as well. Sixty-five years later, the American Art Museum, Mecklenburg says, is recognizing how “the influences he absorbed and projected played an important [role] in the art history of this country.”

Recent shows at the American Art Museum also illustrate the art world’s firming grasp on how much the Americas as a whole have influenced U.S. culture. As the curator and architectural historian Barry Bergdoll notes, there’s long been a notion that ideas are generated in the north and trickle down. But museums are finally taking Latin American art and U.S. Latino artists more seriously. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 data, Latinos are the largest American ethnic minority, representing 17 percent of the population, and art institutions are making a concerted effort to better reflect the people they serve.

Museums, too, are increasingly using the American label to acknowledge the country’s ugly past—even celebrating the role artists from abroad have played in capturing that uncomfortable history. Earlier this year, the American Art Museum displayed 70 paintings and drawings by the Japanese-born modernist Yasuo Kuniyoshi. He came to the United States in 1906 as a teenager but was barred from becoming a citizen under immigration laws, and the government classified him as an “enemy alien” after Pearl Harbor. He had a complicated relationship with his own identity: During World War II, Kuniyoshi created anti-Japan posters for the Office of War Information and participated in propagandizing radio broadcasts. Reviewing the American Art Museum’s current show, the Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott reflected on how Kuniyoshi’s most productive years coincided with “an ugly age of racism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sentiment,” in which the artist himself played a role. Yet Kennicott describes Kuniyoshi’s art as “deeply American, or at least as American as it is anything else.”

In the past, museums relied on straightforward, inflexible criteria to determine what could be considered American art. In 1986, the Whitney’s then-director Thomas Armstrong sent a letter to the influential dealer André Emmerich declaring that his client, the British-born painter David Hockney, wasn’t American enough for the museum—despite the fact that he was living in Los Angeles, where he created poolscapes like A Bigger Splash that have come to define the city’s mid-century panache. “Unfortunately, our criteria is citizenship, not longevity or residency in the United States. In this period of great change, that is one thing that is not destined to be altered, as far as I’m concerned,” Emmerich said. The Whitney has since featured the works of plenty of non-citizen artists, including Hockney himself.

Curators and art historians let general instinct guide them: Does the art look or sound—does it feel—American?Unlike the Whitney and the American Art Museum, which have had to redefine themselves as they’ve grown, museums founded in the last decade get the benefit of hindsight and a clean slate. “As a young museum building its collection, we look to artists to guide us through the complex issue of nationality. How do or did they define their relationship with the United States?” said Margaret Conrads, the director of curatorial affairs at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, which was founded four years ago in Bentonville, Arkansas. “Place is very important to us, so an artist has to have a substantial connection to the American experience. We recognize that can manifest in different ways.”

What We Want, What We Need,

What We Want, What We Need,2014 (Jeffrey Gibson)

As such, Crystal Bridges is explicit about the prejudices that have shaped American art over time. For example, an exhibition this summer reflected how attitudes toward Native Americans shifted through the course of the 19th century. Artists of European descent used to show the American Indian as a “noble savage,” with classic references to Greek and Roman sculpture. But as federal laws like the 1830 Indian Removal Act forced tribes from their land, some white Americans began to draw and paint more politically aware images. More recently, Crystal Bridges has made efforts to give Native Americans more power as artistic creators, not just the subjects they’ve historically been. One of the latest purchases in the museum’s contemporary collection is a work by Jeffrey Gibson, a Brooklyn-based member of the Mississippi band of Choctaw Indians. The sculpture, a punching bag covered with glass beads and nylon fringe, is titled What We Need, What We Want.

* * *

Though museums are actively grappling with the notion of American-ness in art, the State Department’s Cultural Affairs Division has yet to do the same. In order to represent the U.S. at the Biennale, the federal government still requires artists to hold an American passport, but they’re under no obligation to present any work inspired by or about the United States.

This year, the U.S. State Department selected the 79-year-old pioneer Joan Jonas—an early adopter of video and performance art—as the official U.S. artist representative for the 56th Biennale, to rave reviews. Her show, They Come to Us Without a Word, presented largely universal themes—fragility, loss, nature—rather than specific social or political ones, says Paul Ha, a co-curator of the country’s 2015 pavilion and the director of MIT’s List Visual Arts Center.

They Come to Us Without a Word (Joan Jonas)

They Come to Us Without a Word (Joan Jonas)  They Come to Us Without a Word (Joan Jonas)

They Come to Us Without a Word (Joan Jonas)  They Come to Us Without a Word (Wind) (Joan Jonas)

They Come to Us Without a Word (Wind) (Joan Jonas) Most commissioning curators, Ha says, propose an artist who they believe the 500,000 international Biennale visitors should experience, regardless of national origin—an artist who “speaks to today.” They Come to Us Without a Word includes a series of video projections, as well as freestanding, rippled mirrors and various suspended objects, such as colorful kites, that cast reflections and shadows off one another throughout the exhibit—creating a kind of fanciful Alice in Wonderland effect.

This move away from the regional characterizes other artists whose work has appeared at the Biennale—in an extension of how museum curators have been thinking of categorization. The sculptor Sarah Sze, who represented the United States at the 55th Biennale in 2013, says she felt responsible not to her home country, but to the thousands of international visitors who streamed through America’s pavilion daily during the Biennale. “Either way, I hold an American passport, so whether I choose to or not, I do represent some nationality,” Sze says. But her work, Triple Point, reflected the more universal state of “dystopian anxiety” and appealed to the information overflow people across continents experience on a daily basis.

Triple Point, 2013 (Sarah Sze)

Triple Point, 2013 (Sarah Sze) This isn’t to say that the Biennale—or artists and curators who represent the United States—have come to shy away from themes that invoke politics or social issues. The curator and art historian Lisa Freiman, along with the art duo Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, wanted to directly confront the implicitly nationalist nature of the Biennale. To her surprise, her proposal for a series of installations was accepted in 2010. “I assumed our project was too critical,” says Freiman, the director of Virginia Commonwealth University’s new Institute for Contemporary Art. “We were using all of this American iconography. And as soon as you take a tank and put it in front of the U.S. pavilion, it’s inherently political.”

Gloria (Algorithm) (Allora & Calzadilla)

Gloria (Algorithm) (Allora & Calzadilla) When their project Gloria appeared at the 2011 Biennale, it was among the strongest critiques of American jingoism the competition has ever seen. One of their seven separate installations, Track and Field, showcased a deafeningly loud, overturned tank, a treadmill affixed to its right track, where a U.S. Olympian jogged in uniform for half-hour intervals throughout the day. For their work Algorithm, the artists installed a 20-foot pipe organ reconfigured as a working ATM.

Artists seize on similarly powerful imagery at home, with one example being the artist Sonya Clark, whose work Unraveling ran this summer at New York’s Mixed Greens Gallery. Clark began unraveling the threads of a Confederate flag— a metaphor for racial progress—before the June attack in Charleston, South Carolina, that killed nine black Americans at a church study group. After the massacre and South Carolina’s removal of the Confederate flag from its state grounds, Unraveling has a poignant urgency. Clark’s U.S. nationality and Afro-Caribbean heritage feels inseparable from her work. The same piece, made by an artist from another country, would still reference America’s racial tensions— but would feel more critical and less self-reflective. She asks viewers: How far have we really come since the Civil War?

Gloria (Track and Field) (Allora & Calzadilla)

Gloria (Track and Field) (Allora & Calzadilla) Though the definition and use of the label is shifting, there will always be artists from the past whose work feels quintessentially American, says Stephanie Roach, the director at the FLAG Art Foundation. She points to Jasper Johns, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, and Ed Ruscha, all of whom remixed iconic American staples— such as flags, cowboys, and advertising slogans—creating what are now cornerstones of contemporary art. And there will certainly continue to be shows with distinctly American themes and conspicuously American symbols, even well beyond the reach of the Biennale. Roach described FLAG’s 2011 exhibition by Josephine Meckseper— an artist born and raised in Germany—that referenced America’s over-saturated consumerism, using car and flag imagery throughout.

Unraveling, 2015 (Sonya Clark)

Unraveling, 2015 (Sonya Clark) But is something lost when the art world defines American art so broadly? Have American art institutions abandoned their core purpose if artists need only some appreciable connection to the United States? Or has art outgrown nationality, the way art movements of the 1960s—Minimalism, Fluxus, and Conceptual Art—pushed cultural boundaries forward? The fairly lax interpretation at the Biennale is evidence of a country that doesn’t attempt to control or politicize the production of art. Still, when any label becomes too broad, it risks losing its meaning. In his final book, the late Arthur Danto, a Columbia professor and art critic for The Nation, argued while it’s true that art today is pluralistic, not just anything can be art. “There must be some overreaching properties why art in some form is universal,” he wrote. The same is true for the concept of American-ness, which the art world now challenges freely, and with purpose—expanding its definition as it looks for a new kind of universality.

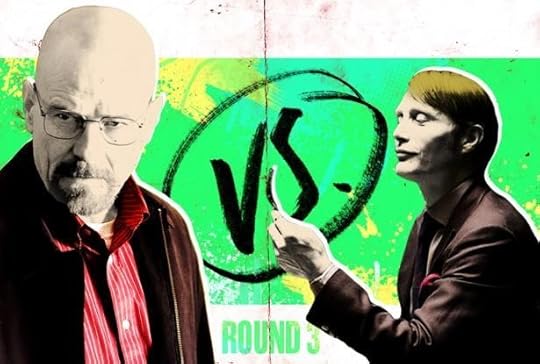

#ActualWorst, Round Three: Walter White vs. Hannibal Lecter

Throughout the month of November, we’re soliciting readers’ help to definitively answer an age-old question: Who is the actual worst character on television? We reviewed your submissions, did our own research, and came up with a list of 32 characters across four different categories, who’ll go head to head over the next four weeks until one of them is crowned as the most despicable, unlikable, flat-out awful (fictional) person on the small screen.

This bracket, while intended to determine the relative awfulness of characters on television, is subject to the fact that “worst” is a complex superlative that can incorporate a number of different qualities. In no way are we suggesting that being a narcissistic 20-something is equivalent to, say, killing people and eating them. Rather, our goal is simply to map out which of these fictional characters we love to hate and which we hate to love.

See the bracket in its entirety here.

The Case for Walt (Breaking Bad) AMC

AMC Why this character is the actual worst: Walter starts out noble enough—he’s a chemistry teacher stricken by cancer, and looking to set up his family after he’s gone, he starts cooking meth to provide some extra bucks. But as his special formula spreads like wildfire through New Mexico, Walter becomes more and more drunk with power, and starts to behave as ruthlessly as the crime bosses who employ him, resorting to coercion and murder to stay alive.

Worst moment/s: When Walter needs to win back his protégé Jesse’s trust at the end of Breaking Bad’s fourth season, he hatches an evil scheme to snatch him from the jaws of drug lord Gustavo Fring. Using a rare flower that grows in his backyard, Walter poisons a young boy who Jesse has befriended, and pins the crime on Gus. Yes, Walter is not above poisoning children to achieve his goals.

Worst trait/s: Arrogance. Walter’s undoing is always his firm belief that he’s better than everyone else: It’s what made him a high-school teacher when he should have been a multi-millionaire industrialist, because he couldn’t play with others. And it’s what makes him try to take down his drug-lord bosses even though they’re paying him millions to cook meth for them.

Redeeming moments/qualities: When the show begins, Walter is a family man, and he gets into the drug biz to provide for them. Though that selflessness shrivels and dies as the series goes on, there’s enough left by the end of the series for him to arrange for his wife and kids to live in some semblance of safety after his misdeeds go public. —David Sims

The Case for Hannibal (Hannibal) NBC

NBC Why this character is the actual worst: Hannibal is a serial killer, which is a bad foot to start on. But he’s a special kind of serial killer who likes to cook and eat his victims after they’re dead, prepare them as gourmet meals, and serve them to guests. He’s also a psychiatrist with a predilection for chaos, who allows the clearly mentally ill FBI agent Will Graham to continue fighting crime even as he slips into madness under Lecter’s watch.

Worst moment/s: The list of Hannibal’s misdeeds is absurdly long. Maybe his grossest trait is serving cooked people up to other people; topping even that, though, is what he does to poor Abel Gideon (Eddie Izzard), a fellow murderer who gets on Hannibal’s bad side by taking credit for his crimes. Hannibal chops his legs off but keeps Gideon alive, and then they share a meal of, well, human leg together.

Worst trait/s: Probably the whole “he kill you and eats you” thing. Still, there are people in Hannibal’s life that he clearly values, and through the course of the series he has to turn on all of them to save his own skin—for all his politeness, he’s as inherently selfish as the rest of us.

Redeeming moments/qualities: There’s a lot to like about Dr. Lecter. He’s a well-read man, a witty conversationalist, a fantastic cook, and he’s sartorially blessed. It’s how he gets away with all that murdering—people just don’t want to think Hannibal could be up to no good. —David Sims

Can Terrorists Really Infiltrate the Syrian Refugee Program?

If you look solely at the U.S.’s long record of taking in refugees from countries torn apart by war, it’s hard to argue that national security should be a top concern in the debate over Syrian migrants.

In the 14 years since September 11, 2001, the United States has resettled 784,000 refugees from around the world, according to data from the Migration Policy Institute, a D.C. think tank. And within that population, three people have been arrested for activities related to terrorism. None of them were close to executing an attack inside the U.S., and two of the men were caught trying to leave the country to join terrorist groups overseas.

“I think I can count on one hand the number of crimes of any significance that I've heard have been committed by refugees,” said Lavinia Limón, a veteran of refugee work since 1975 and the president of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. “It just hasn’t been an issue.”

Yet it is the issue now, as the Obama administration tries to fend off a revolt by Republican governors over its plans to resettle more than 10,000 Syrian refugees escaping the brutality of both the Islamic State and the Assad government. The coordinated attacks in Paris have fanned fears that terrorists could infiltrate the U.S. by slipping in among the refugees—as might have occurred in the case of one of the Paris attackers.

As U.S. officials and refugee advocates point out, that has never happened in modern history. Not when the U.S. took in tens of thousands of Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s. Not when 125,000 Cuban “Marielitos” arrived by boat in 1980. And not in the desperate aftermath of more recent wars in Bosnia, Somalia, or Rwanda. “Those fears have proven unfounded,” said John Sandweg, a former acting director of ICE who previously served as a top lawyer at the Department of Homeland Security.

Is there any reason why Syria should be different?

“I think I can count on one hand the number of crimes of any significance that I've heard have been committed by refugees. It just hasn’t been an issue.”The government and the nonprofit organizations it partners with to resettle refugees cite two main reasons why the answer is no. The first is that there is a key difference between people seeking placement in the U.S. as refugees and the millions of people who have flooded into Europe seeking asylum. The Syrians in Europe in many cases are already at or over the border, having come directly from Syria in to Turkey and then Greece and elsewhere; that situation is more akin to the thousands of Cubans who have fled by boat to South Florida or the migrant workers from Central America who gathered at the U.S.-Mexico border last summer. A refugee applying for resettlement in the U.S., by contrast, must endure a screening process that takes as long as two years before stepping foot on American soil. “Germany doesn’t have the luxury of screening them or vetting them in any way before they arrive, unlike the United States,” said Kathleen Newland, a senior fellow and co-founder of the Migration Policy Institute.

The second reason is that since the program was briefly halted and then overhauled after the 9/11 attacks, refugee applicants are subject to the highest level of security checks of any type of traveler to the U.S. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees initially chooses which refugees to refer to the U.S. after doing its own check. U.S. officials then conduct multiple in-person interviews and verify a refugee’s story with intelligence agencies and by running background checks through several government databases, including DHS and the National Counterterrorism Center. As a result of that extensive process, only around 2,000 Syrian refugees have been resettled in the U.S. since its civil war broke out in 2011—a much lower number than many previous refugee crises. The Obama administration wants to accept at least 10,000 more in 2016, but even that might be too much for the bureaucracy to handle. Once resettled, refugees get housing and monetary assistance for several months. After a year, they can apply for a green card, at which point they undergo another security screening.

More than half of the nation's governors—mostly Republicans—are now urging the federal government to keep Syrian refugees out of their states. But they probably don’t have the final say. Courts have ruled that immigration policy is almost entirely a federal matter, and while the Obama administration says it must “consult” with states as part of the refugee program, the states can’t reject immigrants entirely. Yet as a practical matter, because the benefits that refugees receive are administered at the state level, the government might be unlikely to send them to states where they won’t be welcome.

A central question that Republicans have raised is whether the U.S. has good enough intelligence and data from Syria to determine if a refugee might pose a threat. How extensive is their database? How easy would it be for an applicant to use forged or stolen documents to get into the U.S.? Critics of the refugee policy have gained ammunition from FBI Director James Comey, who acknowledged while testifying before Congress in October that there were “certain gaps...in the data available to us.” He declined to detail those concerns in an open hearing, saying he did not want to provide a roadmap for terrorists. “There is risk associated with bringing anybody in from the outside, but especially from a conflict zone like that,” Comey said.

“There is risk associated with bringing anybody in from the outside, but especially from a conflict zone like that.”Republican governors and congressional leaders (along with a few Democrats) have seized on those remarks in calling for “a pause” in the Syrian refugee program so it can undergo another review, and the House could pass legislation to that effect in the next few days. Refugee advocates, however, say there is little cause for concern. “I just don’t find that argument plausible,” Newland told me. She said the U.S. might have less data on Syria than on Iraq and Afghanistan, where the military has had a presence for more than a decade. “But I don't think there’s less information than there would be any other refugee population,” Newland said. She added that coming from a police state that likes to keep track of its people, refugees from “a well-organized society” like Syria would be more likely to have documentation than those fleeing from impoverished countries where citizens are unlikely to have government-issued birth certificates or passports.

Steven Camarota, the director of research at the right-leaning Center for Immigration Studies, said the key difference between Syria and most other sites of recent humanitarian crises is the heavy influence of a group devoted to the destruction of the U.S. and Western society. He also disputed the blemish-free history that advocates of the refugee program have clung to, citing Somali immigrants in Minnesota who have left the country to join ISIS and the case of the Boston Marathon bombers, who arrived as children after being granted asylum. Yet the process for receiving asylum status is not as stringent as for those applying for refugee resettlement, and those cases all involved people radicalized while they were living in the U.S. “The point here is,” Camarota said, “is it worth the risk?”

Immigration of any kind has caused tension and in many cases outright hostility throughout U.S. history, and refugee crises are no exception. In a 1939 poll recirculated widely on Tuesday, more than three out of five Americans opposed the resettlement of 10,000 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Oftentimes, the concerns have been economic. In the late 1970s, Newland said, fishermen in California feared competition from Vietnamese refugees who would be willing to work longer hours for lower pay than they did. And states and cities have occasionally asked the federal government to steer refugees elsewhere if they didn’t think they'd be able to find jobs in their communities. But the terrorism-fueled fears that have prompted a rush of opposition to Syrian resettlement is something else. “In my experience,” Newland said, “this is unique.”

November 17, 2015

A Threat in Germany

Updated on November 17 at 3:56 p.m. ET

A soccer match between Germany and the Netherlands was canceled Tuesday hours before kickoff in the city of Hanover after a bomb threat.

At a news conference, Boris Pistorius, the interior minister of Lower Saxony, said: “Contrary to reports, no explosives have been found.” Deutsche Welle, the state-run German broadcaster, had previously quoted Volker Kluwe, the Hanover police chief, as saying: “There was a device intended to be detonated inside the stadium.”

The cancellation comes just days after the November 13 attacks on Paris that killed 129 people. Europe has been on high alert since those attacks.

The Associated Press adds government officials, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, had planned to attend the match to show “that Germany wouldn’t bow to terrorism in the wake of the Paris attacks.”

We’ll update this post when we learn more.

The American President: A Most Optimistic Rom-Com

Here is the climactic romantic exchange from the romantic comedy The American President, the one that brings the movie’s central couple—the eponymous executive and his lobbyist girlfriend—to their happy ending:

President Andrew Shepherd: Sydney, I didn’t decide to send 455 to the floor to get you back.

Sydney Ellen Wade: I didn’t come back ‘cause you decided to send 455 to the floor.

Swoon, right? The lines, to put them in their proper context, are uttered in the Oval Office of the White House, epic orchestrals swelling epically in the background, on the day President Shepherd is to deliver the State of the Union to Congress and the American people. The exchange is followed by a passionate kiss, which is itself the culmination of, in rough order: the widower president dating Sydney after a chance run-in at the White House, and their romance damaging his public approval ratings and thus his political capital and thus his ability to get Congress behind him on the crime bill he needs to get reelected, and, finally—I’m not sure whether a decades-old movie deserves an official spoiler alert, but just in case, SPOILER ALERT—the president betraying Sydney to achieve his political objectives, losing her in the process.

Related Story

It’s the stuff of classic rom-com, right? Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy sends 455 to the floor. And if it all sounds extremely absurd, that’s because, to be clear, it most certainly is. (“Dig it, Ms. Wade,” an assistant tells Sydney, with full mid-’90s flair. “You’re the president’s girlfriend!”) The American President, however, was written by Aaron Sorkin, which means that its absurdities have a way of seeming much more epic than they actually are. The movie, for its many flaws, is a rom-com for the ages, its enduring appeal the result of both Sorkinian eloquence and the romance at the heart of the film. Which is about much more, in the end, than a boy and a girl and a carbon-emissions bill.

The American President was released 20 years ago today. The intervening decades brought, among so much else, 9/11, and wars both literal and figurative, and the Great Recession, and the housing crisis, and the White House’s transition from a Democratic administration to a Republican to a Democratic again. They saw the infamy of the “hanging chad” and the rise of the Tea Party and the normalization of the Internet and, in general, widespread public pessimism about the ability of government, at pretty much every level, to make meaningful change in the lives of those most ordinary and mythologized of creatures: “everyday Americans.”

The American President foresaw the anxieties that would follow it. It tried, in its way, to preempt them.The American President foresaw the prismatic political anxieties that would follow it. And it tried to preempt them. This is the other way the movie functions as a rom-com: It assumes that the relationship between the president and the people is itself, in its way, a romantic one. The American President insists that the connections that tie the government and the governed are primarily emotional. It believes that politics caters most readily to those Americans who, as Stephen Colbert put it, “know with their hearts.”

And so: The film makes clear to its audience that President Shepherd is better than his Republican presidential opponent, Bob Rumson, not because of anything we’re told about Rumson’s policies or vision, but because Shepherd is charming and well-educated and appreciative of America in a nerdy, tell-random-stories-about-the-Founders-at-cocktail parties kind of way. (Rumson, we are meant to understand, is not.) Further, we’re meant to understand that the obvious better-ness exists not just on a political level, but a moral one. As Sydney puts it to Andy, exasperated at Rumson’s latest volley, “How do you have patience for people who claim they love America, but clearly can’t stand Americans?” In other words: Shepherd is Good, and Rumson is Bad, and these are truths Sorkin telegraphs over the course of the film—truths that we, too, can know with our hearts.

The American political system caters most readily, the movie believes, to those who “know with their hearts.”The American President is the cinematic predecessor of The West Wing, and it shares with that show not just assorted idealisms and occasional mansplainings and a general veneer of perky partisanship, but also very specific characters and figures. Its president is a former professor who has been goaded into political office by a best friend who also, conveniently, serves as his chief of staff. Its press secretary is a woman who is notable because of both her wit and the fact that she is unusually tall. Its speechwriter is a guy who is idealistic and overzealous and wunderkind-y. Its dialogue is snappy and full of the kind of light eruditions that congratulate and soothe in equal measure. (“Come, friends, let us away,” A.J. McInerney, the best-friend-chief-of-staff, tells his fellow staffers. McInerney is played by Martin Sheen, who plays President Josiah Bartlet on … yeah.)

And the other thing The American President insists on, just like The West Wing, is the moral goodness of big government itself. The film has faith in the convening power of politics. It, too, is progress porn. For all its nominal concentration on the relationship between Sydney and Andy, The American President’s most climactic scenes—and its most soaring lines—are reserved for the passionate and rewarding and occasionally volatile relationship shared between Andrew Shepherd and the American public. “People want leadership, Mr. President,” the speechwriter Lewis Rothschild tells Shepherd in a heated moment, “and in the absence of genuine leadership, they’ll listen to anyone who steps up to the microphone. They want leadership. They’re so thirsty for it they’ll crawl through the desert toward a mirage, and when they discover there’s no water, they’ll drink the sand.”

Later, President Shepherd will tell the American people, in full professorial mode:

America isn’t easy. America is advanced citizenship. You gotta want it bad, ‘cause it’s gonna put up a fight. It’s gonna say, You want free speech? Let’s see you acknowledge a man whose words make your blood boil, who’s standing center stage and advocating at the top of his lungs that which you would spend a lifetime opposing at the top of yours. You want to claim this land as the land of the free? Then the symbol of your country can’t just be a flag; the symbol also has to be one of its citizens exercising his right to burn that flag in protest. Show me that, defend that, celebrate that in your classrooms. Then, you can stand up and sing about the “land of the free.”

That line comes during the other romantic climax of The American President, the one that brings Sydney back to the White House, the one that takes place when Shepherd—who has been stubbornly avoiding engagement with Rumson’s attacks—finally dispatches with his political opponent by way of a surprise press conference on the morning of the State of the Union. Shepherd announces that he’s scrapping his crime bill, re-writing it to create “a law that makes sense.” And he also announces, swoon, that he is sending the environmental bill—hi again, 455!—to the Congressional floor with a call for a 20-percent reduction in carbon emissions (rather than, as previously planned, a paltry 10 percent). He then gives his long exegesis on American democracy. America isn’t easy. America is advanced citizenship.

And he then delivers what is perhaps the most enduring line in a movie that also features Michael J. Fox, as the wunderkind-y speechwriter Lewis Rothschild, uttering the line “no hopping, sir, no hopping!” Bringing the hammer down on Rumson’s repeated declarations of “I’m Bob Rumson, and I’m running for president,” Shepherd closes his game-changing press conference with, “I’m Andrew Shepherd, and I am the president.”

The president does what a romantic lead will always do: redeem himself via a Grand Romantic Gesture.And! In the process of all this, woven into his rebuttal of Rumson and his soaring ode to the productive complications of American politics, President Andrew Shepherd defends the honor of one Sydney Ellen Wade.

Which is also to say: With a single off-the-cuff speech, rendered honestly and passionately, Andrew Shepherd is able to, among other things, save his presidency, save his dignity, save his relationship, and, the partisan would argue, save his country. Which is on the one hand a testament to the Power of Words—a favorite preoccupation of Aaron Sorkin, the writer—but on the other a testament to The American President’s status as a sweepingly politicized rom-com. This is the president, doubling as a romantic lead, doing what the romantic lead will almost always do: excusing himself and redeeming himself via a Grand Romantic Gesture.

This makes The American President delightful as a rom-com; as a forecast of contemporary political culture, however, it’s significantly less appealing. The logic of romance—passion, betrayal, heart-over-head—is awkward, and occasionally dangerous, when applied to politics. It’s the stuff that gives so much agency to “optics,” to the stuff of “I know her heart,” to the stuff of slogans and logos and What’s the Matter With Kansas. The stuff, in the end, of truthiness.

Robert Redford was initially set to play Andy Shepherd in The American President: The actor, it’s said, was eager to be part of a “love story” set in the White House. When Rob Reiner was brought on as director, though, Redford bowed out, leaving the role for Michael Douglas: Reiner and Sorkin, Redford felt, had created a film that was too much about politics, and not enough romance. The irony, 20 years later, is how little merit Redford’s objections seem to have today. There’s love, and there’s government; it’s getting harder and harder, however, to tell the difference between the two.

Putin’s Promise in Syria

When Russia started bombing extremists in Syria last month, news and intelligence reports suggested its missiles were not trained on the Islamic State—the threat it said it was going after—but instead on rebels fighting against the Assad government, Moscow’s longtime ally.

But that was before a plane fell out of the sky, and civilians were shot and blown up in Paris and Beirut.

After days of hedging, Moscow on Tuesday confirmed that Metrojet Flight 9268 was brought down over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula by an“improvised explosive device,” which detonated soon after takeoff and tore the aircraft apart in midair. In remarks that were televised nationwide, President Vladimir Putin set the tone of his country’s air campaign in Syria moving forward.

“We should pursue them without any statute of limitations and should know all of them by name,” Putin said of the perpetrators of the plane crash. “We will be looking for them wherever they would try to hide. We will find them in any part of the world and punish them.”

The Russian investigation into the crash did not place blame on the Islamic State, whose Sinai branch has claimed responsibility. But on Tuesday, Moscow sharply intensified its air strikes against Islamic State targets in Syria.

“A massive airstrike is targeting ISIL sites in Syrian territory,” Russian Defense Minsiter Sergei Shoigu said, using one of the acronyms for the Islamic State. “The number of sorties has been doubled, which makes it possible to deliver powerful pinpoint strikes upon ISIL fighters all throughout the Syrian territory.”

A U.S. Defense Department official told The New York Times the Russian government warned the U.S. it would be carrying out “a significant number of strikes in Raqqa,” the Islamic State’s stronghold in Syria, before the first strikes launched. Putin has ordered Russian naval forces to work with French warships “as allies” in attacking the terrorist organization.

For weeks, Western nations watched with skepticism as Russian strikes targeted areas significantly west of Islamic State strongholds in Syria. As the Institute for the Study of War reported in early October:

The Russian Defense Ministry claimed that the airstrikes targeted eight Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) positions in total. The Syrian regime also released statements confirming Russian airstrikes in Homs and Hama, claiming that the airstrikes targeted both ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliated militants, likely referring to Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra. However, local Syrian sources claim the airstrikes exclusively targeted rebel positions, including the headquarters of Free Syrian Army-affiliated, Western-backed TOW anti-tank missile recipient al-Izza Gathering in the town of Al Latamneh, rather than ISIS-held positions.

On Tuesday, Putin vowed payback for extremists over the deaths of the 224 people aboard the downed jetliner.

“Our air force’s military work in Syria must not simply be continued,” he said. “It must be intensified in such a way that the criminals understand that retribution is inevitable.”

Tragedy + Comedy = Catharsis

Put John Oliver’s name into Google, and the first auto-complete option that follows it now is “Paris,” and for good reason. After Friday’s horrific attacks, Americans may have turned to the news, the Internet, and politicians for information and context, but they turned to comedians for relief. On his HBO show Last Week Tonight, Oliver provided that in its simplest form possible, as one of the first late-night hosts to address the attacks.

“First, as of now, we know that this attack was carried out by gigantic fucking assholes. Unconscionable, flaming assholes. Possibly, possibly working with other assholes—definitely in service of an ideology of pure assholery,” he told the camera. “Second, and this goes almost without saying: Fuck these assholes. Fuck them, if I may say, sideways.”

Vox called Oliver’s rant “exactly the right response.” The New Yorker declared “Vive John Oliver.” Vanity Fair praised him for responding “as no one else could.” There was nothing especially insightful about what Oliver said, but he tapped into the outrage and fury that many of his viewers were feeling. As such, those headlines captured a broader truth about what figures like Oliver do: Late-night comedy, in particular, plays a unique and crucial role in helping people deal with unthinkable tragedies.

“I’m sorry to do this to you. It’s another entertainment show beginning with [the] overwrought speech of a shaken host, and television is nothing if not redundant,” said Jon Stewart on the first Daily Show broadcast after 9/11. “It’s something that unfortunately we do for ourselves so that we can drain whatever abscess is in our hearts and move onto the business of making you laugh.” His speech that day is still widely viewed on YouTube, as is David Letterman’s, and the famous Saturday Night Live intro where Lorne Michaels asks Rudy Giuliani if the show can be funny, and the Mayor responds, “Why start now?” Of course, those were all shows broadcast from New York wrestling with an attack in their city, but each marked a cathartic moment for viewers around the country—and the world—who’d been stunned by the news.

The bar for late-night shows is a deceptively high one to clear. Yes, they need to acknowledge the weight of a tragedy, at least. But there’s a lot of grace required to do that without the traditional cynicism of a late-night host, and then to smoothly transition out of a more somber tone to get back to the comedy at hand. Oliver stuck to his persona as the fearless soapbox king, unafraid to use the starkest language possible, mirroring the anger and frustration that comes with helplessly watching carnage unfold around the world. Saturday Night Live replaced its cold open with a Cecily Strong monologue in praise of Paris, a classy tip of the hat to the city’s endurance.

Stephen Colbert briefly mentioned the attack at the end of his Friday show, but returned on Monday with a more detailed speech that praised France’s long history of brotherhood with America. He also noted the strange power of any action taken in memoriam, even watching the Paris-set (but U.S.A.-made) film Ratatouille. “Is Ratatouille a French film? No. Is it a valid expression? Absolutely,” Colbert mused. “Because watching a cartoon Parisian rat make soup is certainly as valid as anything I will say tonight, I promise you that.”

Late-night comedy plays a crucial role in helping people decompress after unthinkable tragedies.Colbert’s Monday episode also served to highlight how much things have changed since 2001 in terms of political discourse. Less than a week after 9/11, Bill Maher notoriously criticized U.S. military policy in a panel discussion on his ABC show Politically Incorrect, saying, “We have been the cowards. Lobbing cruise missiles from 2,000 miles away, that’s cowardly. Staying in the airplane when it hits the building, say what you want about it, not cowardly.” At a particularly sensitive moment, his phrasing came under fire, and Politically Incorrect was cancelled the following June after losing some major sponsors (Maher moved to HBO).

Yesterday, Maher was the guest on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, where the two had a spirited conversation about the generalizations Maher has made about religion and how he relates Islam’s billion-plus followers to the philosophy of ISIS. The tensions between the two hosts shone through. “You see, my religion teaches me humility in the face of this kind of attack,” Colbert deadpanned after Maher mocked his Catholic faith. “Liberals have to say ‘no quarter’ to these kinds of ideas,” Maher said on the treatment of women in Islam, while dismissing the notion that any kind of war could be waged on ideas alone.

Their conversation went all over the place and touched on sensitive topics without reaching many satisfying conclusions, but it was the kind of thing that’s been virtually absent from network TV in the 14 years since 9/11. Comedy is a place for unpacking emotion and “draining the abscess,” as Stewart put it, but it should also be open to the exchange of deeper ideas, not just polemic. The kind of thoughtful discussion Colbert and Maher had is an early sign that late-night may be heading in the right direction.

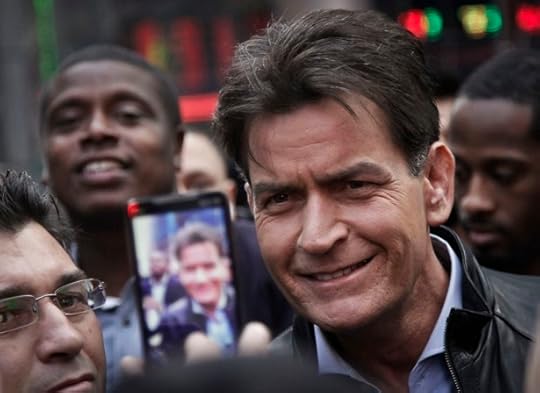

Sympathy and Contempt for Charlie Sheen

Charlie Sheen is a person, and people with problems deserve sympathy. On the Today show this morning, he talked about struggling with the diagnosis of HIV he received “three or four” years ago. “It’s a hard three letters to absorb,” Sheen said. “It’s a turning point in one’s life.” Matt Lauer later read him some of the kind reactions coming in on social media. Sheen seemed touched.

Charlie Sheen is also a celebrity, and celebrities’ words can have public implications. As the most prominent figure to announce a positive status in quite some time, he offers a reminder that even though HIV/AIDS no longer commands the headlines it once did in the U.S., around 35 million people worldwide are living with it. His story also reiterates the idea that it’s not just a “gay disease” and could bring renewed attention to a public-health crisis that has an

What’s the Matter With Belgium?

French authorities say they believe Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a 27-year-old Belgian man, masterminded the November 13 attacks in Paris.

The focus on Abaaoud helps emphasize how tiny Belgium has taken on an oversized role in the European theater of jihad. The country has provided a steady flow of fighters to ISIS in the Middle East—including Abaaoud—and has been the site of planning of attacks in Europe. (The Daily Beast has a good timeline of incidents involving Belgian militants.)

Abaaoud was already suspected of planning a prior attack that was foiled by Belgian authorities in the days after January’s Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris. Two suspects were killed in the operation. At the time, Slate’s Joshua Keating warned: “The Belgian police may claim today to have ‘averted a Belgian Charlie Hebdo,’ but it’s clear that the country’s radicalization problem is much larger, and will take more than police raids to address.” Those words proved prophetic.

Related Story

Belgium has just 11 million people, and Pew estimated that about 6 percent of the population was Muslim as of 2010. But Belgian and French nationals make up around a quarter of the Europeans who went to fight in Iraq in the mid-2000s. While the government has acknowledged that hundreds of Belgians have gone to fight with ISIS or for other groups in the Syrian civil war, Pieter Van Ostaeyen, an independent researcher, calculated in October that 516 Belgians had fought in Iraq or Syria, far higher than the government’s figures. Based on his numbers, Belgium has contributed more fighters per capita to the fight in the Levant than any other European country.

The central figure in Belgian militant Islamism is Fouad Belkacem, a 33-year-old preacher and founder of the group Sharia4Belgium. He was born in Belgium to Moroccan parents, and is a disciple of the British radical Islamist Anjem Choudary. Belkacem, who had been arrested for various petty crimes, organized burnings of American flags after 9/11 and harassed gay Muslims. Sharia4Belgium became a major feeder for fighters in Syria and Iraq, including Jejoen Bontinck, whom Ben Taub profiled in an excellent New Yorker story. Bontinck, a former TV dance-show celebrity, was a convert, as many of the most prominent European ISIS fighters have been. (Van Ostaeyen calculates that only 6 percent of Belgian-national ISIS fighters are converts, however.) Others, like Abaaoud, came from secular or mildly observant Muslim families, but became radicalized. In December 2014, Belkacem and 45 other members of Sharia4Belgium were found guilty of membership in a terrorist group. He is serving a 12-year prison sentence.

Belgian jihadism seems to mimic French Islamist militancy, only more concentrated—as befits the smaller country. Both have large numbers of immigrants who are poorer and isolated from the dominant culture. Both countries have also seen far-right, anti-immigrant parties rise by loudly declaring a Muslim menace. Experts also say it is comparatively easy to acquire illegal guns in Belgium, making it an attractive base for operations. The Washington Post notes that Belgium’s unusual bilingualism—Flemish and French—makes it hard for immigrants who only speak French to find work and assimilate. And deep distrust between French- and Flemish-speaking government officials has created an elaborate and sclerotic security apparatus that doesn’t always deal with threats efficiently and promptly.

In particular, Belgian jihadism is concentrated in Molenbeek. It’s a neighborhood of nearly 100,000 people in Brussels, northwest of the city center, which has had a large Muslim population for many years. There are 22 known mosques in the district. Molenbeek shares some characteristics with the banlieues in French—densely populated, large immigrant populations, very high unemployment, complaints of inadequate government services, isolation from the central city and corridors of power. In other ways, however, Molenbeek is rather different: It has a strong middle class, bustling commercial districts, and a gentrifying artist class.

“I notice that each time there is a link with Molenbeek,” Prime Minister Charles Michel said Sunday. “This is a gigantic problem. Apart from prevention, we should also focus more on repression.” (That unfortunate wording may be a failure of translation.) Interior Minister Jan Jambon added: “We don’t have control of the situation in Molenbeek at present.”

Jambon’s statement has reawakened concerns about Muslim “no-go zones” in European cities. It’s an idea Bobby Jindal, the Louisiana governor and Republican presidential hopeful, was heavily pushing in January. According to the myth, there were large zones that police forces had simply ceded to sharia gangs, and into which neither non-Muslims nor law enforcement dared to go. When I looked into it at the time, there was no evidence that such areas actually existed. Even Daniel Pipes, a leading alarmist about the threat of radical Islamism, argued that Jindal was mistaken in describing the banlieues that way. But there were disturbing reports of gangs of men intimidating or beating non-Muslims or residents whom they deemed insufficiently observant.

Does Molenbeek prove that no-go zones are real? On the one hand, there’s Jambon’s statement. But in other clear ways, Molenbeek doesn’t appear like a Muslim exclave in the middle of Brussels. Jambon himself pointed this out in his remarks on TV on Sunday, mentioning Molenbeek’s non-Muslim mayor and its own constabulary: “I see that Mayor Françoise Schepmans is also asking our help, and that the local police chief is willing to cooperate. We should join forces and ‘clean up’ the last bit that needs to be done, that’s really necessary.” Journalists seem to be having little trouble reporting from the area; Politico sent a reporter and photographer out in the neighborhood, and found that while residents were not eager to speak to the press, it looked in many ways like a typical, somewhat run-down district.

“Daily life in Molenbeek works well—but that’s maybe what has fooled us: that in ordinary life, there are no difficulties,” Schepmans, the mayor, said. “And next to that, there are people living in the shadow. And we have left them living in the shadow. We didn’t ask ourselves the right questions.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower