Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 297

November 14, 2015

By the Sea: When Ennui Is Très Jolie

By the Sea is not a film for everyone. For an hour or so, it doesn’t even feel like a film at all so much as a 132-minute perfume ad; a two-hour-plus Vogue shoot in stereo; an almost microscopic view of the pores, particles, and presence of one of the most famous women in the world. It takes a mighty amount of charisma to make Brad Pitt feel like an afterthought, but Angelina Jolie, who wrote and directed the movie, and who stars as one half of its central married couple, makes no bones about the fact that she’s the star here—and rightly so, given that it’s hard to imagine By the Sea being anything but insufferable with a less magnetic actress as its focal point.

Jolie is canny enough to recognize that beauty frequently trumps endeavor in art, and By the Sea is extraordinarily sumptuous, exploring the physical qualities of its stars and their surroundings in almost voyeuristic detail. At the film’s opening, Roland Bertrand (Pitt) and his wife, Vanessa (Jolie), are driving in a vintage silver Citroen convertible through the French countryside, she in a leopard-print fur hat and YSL shades, he sporting a porn-star mustache and an air of unease. When they finally arrive at the seaside hotel they’ve booked for a lengthy stay, they bring with them all the accoutrements of luxury travel born by the extraordinarily privileged: Louis Vuitton luggage, stacks of hat boxes, couture nightgowns, and marital tension that cuts through the briny air like a straight razor.

The movie is set in the 1970s, but it takes a while to pinpoint the era, given the sheer extravagance of old-world glamour stretched out across the frame. And for the first hour of the movie, that’s pretty much all there is, as the camera lingers on Vanessa’s furious desolation and Roland’s alcoholic escapism. (There’s a tiny moment of levity when Roland tries to make nice with the owner of a bar beneath the hotel as they check in, and Vanessa, painfully fretful, downs her verre de vin blanc in a single gulp.) The elephant in the room is a traumatic event that’s hinted at but not spelled out, even though it’s fairly obvious. Vanessa weeps silent tears, guzzles pills, and takes solace in a series of ridiculously fabulous diaphanous robes; maybe a full third of the movie consists of scenes of her lounging on a sunchair, clutching a magazine, so in thrall to ennui and despair that she can barely hold her cigarette.

This kind of self-indulgent misery and poisonous anguish is, depending on your perspective, either absurdly overwrought or a hallmark of the French New Wave. Certainly, it’s an ambitious project for a still-green filmmaker, and one that’s enhanced by its $10 million budget, and by the lavish cinematography of Christian Berger. Jolie’s direction isn't just confident, it’s brazen: The movie has the audacity to proceed at a truly glacial pace for the first half and waddle only slightly faster toward a conclusion in the second. But there’s true pleasure to be mined from the visual elements on display, from the treacherous landscape surrounding the hotel (Malta, standing in from the South of France) to the opulence of the gilded cage Vanessa confines herself in.

Still, By the Sea isn’t purely superficial, particularly when Vanessa and Roland become interested in the couple staying in the room next door, Lea and François (Melanie Laurent and Melvil Poupaud). When Vanessa discovers a peephole, she begins watching them when Roland goes to the bar. Her voyeurism is, in uncomfortable ways, mimicked by the audience, whose primary motivation for watching the film is surely to observe the real-life couple onscreen (the last time Jolie and Pitt were together in a movie was a decade ago in Mr. and Mrs. Smith). Jolie is canny enough to implicate us in her character’s curiosity about the young, vibrant honeymooners in the next room—about their lovemaking, sure, but also their more banal moments, like how they celebrate their two-month anniversary, or how François wants Lea to do her hair. She surely knows that when it comes to curiosity about beautiful people in love, no detail fails to intrigue.

This kind of self-indulgent, rich person misery is, depending on your perspective, either absurdly overwrought or a hallmark of the French New Wave.The problem is that Roland and Vanessa, by contrast, are dull—their relationship is only slightly enlivened by what becomes a shared tendency for staring through the peephole, and bizarrely, they have no chemistry whatsoever. The main flaw in Jolie’s direction is the performance given by her husband, who’s wooden at best and hopelessly unconvincing in his worst scenes. Pitt has proved himself to be an capable actor in the past, so maybe his defiant refusal to really connect with his Jolie in scenes comes from a desire to hold something back: to not expose any more of himself and his relationship than he has to.

Perhaps the movie could have been more of a success with a different actor, and a couple less determined to show that their marriage really is nothing like what’s happening onscreen. Perhaps it’s an expensive, long-simmering vanity project (Jolie has been working on the screenplay since her mother’s death eight years ago, and Roland and Vanessa in fact share her mother’s surname, Bertrand). But it’s a fascinating experiment, and proof that Jolie truly has directorial chops and an extraordinary eye for imagery. Since art house is particularly lacking when it comes to female auteurs, it’s at the very least reassuring that there’s a woman with the authority and the self-possession to get something like this made.

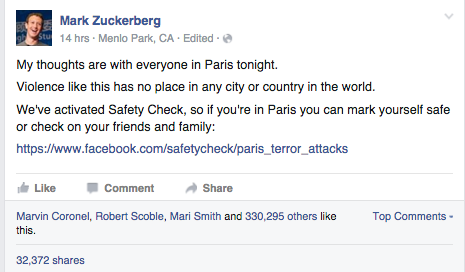

A New Use for Facebook’s Safety Check

Just hours after coordinated attacks left at least 127 people dead in Paris, Facebook activated its “Safety Check” feature. This was the first time Safety Check has been used outside of a natural disaster setting.

Facebook

Facebook The feature works like this: Facebook uses geolocation to identify users who live or may be traveling in an area affected by a disaster. The social-media network then sends these users a notification asking about their safety, and encouraging them to “check in” to let friends know that they are safe.

According to Facebook, Safety Check was inspired by the use of social media during the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Launched in October 2014, the feature was first activated following the Nepal earthquake in April. It has since been activated in other natural-disaster circumstances, including the earthquake in Chile in September and Hurricane Patricia and the earthquake in Pakistan, both during October.

Indeed, it seems Facebook’s Safety Check was initially intended for information and status sharing following natural disasters, not terrorist attacks. Facebook’s statement at the launch of Safety Check nebulously identifies the feature as something to be used in times of “disaster”—however, as you can see below, branding of the tool elsewhere is more specific.

Facebook

Facebook Of course, as the Paris attacks prove, Safety Check could be a valuable feature for a broader range of crisis situations moving forward. However, because the feature must be manually activated by Facebook’s “social good” team, there is some level of human discretion involved in deciding when a given disaster merits the activation of the feature.

If the Paris attacks mark an expansion of Safety Check beyond natural disasters, it will be interesting to see how Facebook decides when and where to use it.

Master of None and Authenticity: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Can a Trip Ever Be ‘Authentic’?

Pico Iyer | The New York Times Style Magazine

“Our notion of places—which is to say the romances and images we project onto them—are always less current and subtle than the places themselves. That’s why we work to screen out the many shopping malls and signs for McAloo Tikki in Varanasi as we search for dead bodies near the ghats.”

2015: The Year Asian Americans Finally Got a Shot on TV

E. Alex Jung | Vulture

“Master of None, in particular, has deftly tackled the issues of race: Its easy, conversational tone belies how cleverly it dismantles racial tropes. Moreover, it manages to acknowledge systemic racism toward people of color while refusing to be defined by it ... It could just be fine—mediocre, even—and we don’t have to agonize over whether the show was worth defending because it was ‘the only one.’ It could simply be left alone, and that, in some ways, might be the biggest gain of all.”

I Analyzed 10,000 Craigslist Missed Connections. Here’s What I Learned.

Ilia Blinderman | Vox

“That there exists a digital town square where lonely hearts can declare their feelings without fear of public rejection is both lucky and improbable, but the hit rate, by all accounts, is low ... Still, if it seems strange that a quirky section of a website that prides itself on an aggressively dial-up-era design has gained such traction in popular culture—all in spite of the scarce likelihood of finding love—look no further than the motivations of gold miners or oil prospectors.”

It’s Raining Menswear

Joshua Rothman | The New Yorker

“How plausible is it that, a few years from now, men on the streets of New York will be wearing capes designed by Antonio Banderas? The answer is ‘very’; it’s easy to name the combination of factors—heritage marketing, Game of Thrones, Kanye—that could make it happen.”

Scandal Has Turned Olivia Pope Into TV’s Best Anti-Hero Since Walter White

Alan Sepinwall | Hitfix

“But Rhimes and company have instead turned the show’s crazy history to their advantage. They’re not running away from every wild plot twist from prior seasons, but turning that into the very subject of the series ... Scandal isn’t sprinting away from its over-the-top past, but diving right back into it, and asking how those events would shape the people who endured them.”

The Inside Story on What Makes Spotlight So Extraordinary

Mike Ryan | Uproxx

“Cynicism aside, filmmakers often have a problem with falling in love with their subjects, especially if that subject is still living and breathing. It’s human nature to trust that the person they’re making a movie about is telling the whole story ... this isn’t journalism. But what happens when a filmmaking team doesn’t just take its protagonists’ word for it?”

Peak Inequality: Investigating the Lack of Diversity Among TV Directors

Maureen Ryan | Variety

“When it comes to the issue of diversity in Hollywood, non-white women are the proverbial canaries in the coalmine. A meaningful commitment to inclusion will mean they are hired regularly, along with white women and men of color. Their near-absence hints at much deeper institutional problems in the TV industry.”

The New Cool Girl Trap: Why We Trade One Set of Rigid Rules About Who’s “Likable” For Another

Arielle Bernstein | Salon

“If the ‘cool girl’ performs a fantasy for men, the ‘fuck likability girl’ performs a fantasy for other women: the idea of a female creature so fabulous and free that she just doesn’t care if other people like her at all. Like ‘no makeup’ selfies and the trend of supermodels raving about how much junk food they eat, the anti-likability moment is a layered performance, one part critique of social norms, one part buying right back into them.”

Why Is Othello Black?

Isaac Butler | Slate

“It’s an understandable question. Shakespeare’s writing mostly predates the transatlantic slave trade and the more modern obsession with biological classification, both of which gave rise to our contemporary ideas of race. When Shakespeare used the word ‘black’ he was not exactly describing a race the way we would. ”

You’re the Worst Is the Realest Cartoon on TV

Eric Thurm | Wired

“What’s much more realistic, and more interesting, is forcing the characters to contend with the many projections of themselves, then giving up and going to snort more cocaine. We’re all going to die, and no matter what we won’t stop distracting ourselves with pointless trivialities like ‘connecting with other people’ and ‘happiness,’ something the show prods us with once or twice an episode. What could be more realistic than that?”

The Subtle, Psychological Horror of The Park

It is impossible to play Funcom’s The Park without thinking of recent psychological horror films like The Babadook and Session 9. Though it may be inelegant to bifurcate the horror genre into two categories—the grotesque and grand guignol films of, say, Wes Craven, against smaller, more intimate films—it’s worth doing so to note the way in which these divergent categories reflect two opposite approaches towards fear. In one approach, terrible things happen to the happy-go-lucky teenagers of A Nightmare on Elm Street or Until Dawn, and all the horror is external—at times literally so, in the shocking displays of violence and the presence of gangrenous monsters that haunt the forest and the neighborhood.

But in the latter category, we are the monsters: The horror is internal and it is impossible to delineate where our flaws end and the nightmare begins. The former is predicated on shock and surprise; the latter on the eerie familiarity we find in depression, grief, or loss. Where does the monster in Session 9 ultimately live? “I live in the weak and the wounded, Doc.”

MORE FROM KILL SCREEN Nighttime Visitor Brings Cell Phone Horror to Video Games Bloodborne and the History of Horror The Loving Horror of Let the Right One In Lives on in This Vampiric Video Game

The Park takes the player through a leisurely two-hour (or hurried one-hour) tour of the fictional Atlantic Island Park, a dilapidated place that shut down due to the accidental deaths of employees (of course) and the murder of patrons (de rigueur). From the very first ride onwards, the general theme of the park—and by extension, the video game itself—is one of curdled joy: good times made grotesque, fun made freakish. The protagonist, a single mother by the name of Lorraine Maillard, has taken her son Callum to the local amusement park for the day, only to return in the evening when they realize they’ve forgotten his teddy bear. Out of frustration, Callum runs into the park ahead of the player and then disappears. What follows is an unsettling search through the park: the photo negative of a more conventional day out, where you ride the rides and sample the atmosphere, without lines or crowds or the other mundane inconveniences, all while Lorraine monologues about Callum, her past, and her increasing resentment towards the burden that is her son.

The atmosphere of loneliness and isolation is as essential and tangible an experience as the Ferris wheel or the roller coaster, but is made more central to the video game by the one marginally innovative element offered by The Park: the ability to, at almost any point, call out the name of your missing son. The ubiquity of this gesture is to be noted. Right-clicking at the beginning of the game captures the early sense of harried irritation with the hint of a Bostonian accent: “This isn’t a game, Callum.” As the tension grows and the park becomes more and more unnerving, the voice grows more desperate and accusatory: “Give me back my son!”

But the real cleverness here is how it fills up the empty, atmospheric space of the game. Walking between rides (and you will do a lot of walking) and exploring the weed- and rust-strewn paths of an abandoned amusement part is an empty experience: There’s only so much tension that the half-heard voice or dissonant music can supply. The need to click and call and click and call becomes a way to interact with this empty space—in the same way that players run and jump toward an objective in any other game—that reinforces the terrible gravity of the situation. This woman’s son, after all, is missing in this place. Callum will respond, of course, encouraging his mother to follow him, to come and play, to rescue him—until he stops calling back at all.

The atmosphere of loneliness and isolation is as essential and tangible an experience as the Ferris wheel or the roller coaster.In other media, we have a superfluity of morsel-sized horror stories: Lovecraft made his reputation from the ability to churn out short eldritch narrative after short eldritch narrative; Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” was monocle-poppingly shocking to the genteel readers of The New Yorker in 1948; yearly anthologies are released by small presses that specialize in horror fiction across the world. The idea expressed in the aphorism “had I more time, I would have written you a shorter letter” is an expression of the difficulty posed by concision and preciseness. Length and breadth are, if not safe, then at least comfortable; a curt and crisp piece cannot afford padding: It must be all edge, and no handle. This is not to argue that The Park is a brilliant example of innovation in an industry of bloat, or a novel piercing chill in a medium that loves horror. It’s that, when you realize that the haunted house looks eerily like a gingerbread house, or that your path is a perpetual, literal spiral, you see how damn careful The Park is about using its limited reach to great effect.

As noted above, this game is impossible to play without thinking specifically of the Australian horror film The Babadook. The comparison is illustrative of the thematic hook the video game tries to bury into your heart: Without revealing too much, The Park and The Babadook share similar analogies, and their respective characters (in both works a mother and her child) undergo similar struggles and share similar afflictions. However, it’s where they differ that The Park shows its distinct and dark strength. As the player spirals toward the haunted house, and continues spiraling downwards ever afterwards, the sheer weight of The Park’s curdled hope and joy denies the optimistic ending of its double from down under: In the end, grief and loss cannot be grappled with. Sometimes they cannot be withstood. The monsters win, the humans lose, and the uneasy fact is that both those creatures are the same person.

One Direction, Justin Bieber, and the Sound of Pop’s Future

The Verve famously saw the profits from its biggest song siphoned away by a copyright claim from the Rolling Stones; perhaps they can now pay it forward by suing One Direction. The boy band’s new album Made in the A.M. opens with a string pattern and kitchen-sink rhythm that’ll be awfully familiar to anyone who remembers the ’90s—it’s like a big-budget karaoke version of “Bittersweet Symphony.” The sheet music for the two songs no doubt differs, but now that the “Blurred Lines” verdict has made sonic “feel” actionable, who knows what Richard Ashcroft might try in court?

Then again, the One Direction guys probably don’t have to worry. They and their team are pros at turning classic rock into bubblegum and getting away with it. How can you hear “Steal My Girl” and not think of Journey’s “Faithfully”? What is the opening of “Live While We’re Young” if not the Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” Perhaps because of One Direction’s major-label muscle and scary-energetic fanbase, or perhaps because all involved are very aware of where the legal line is, there are no confirmed cases of aging rock stars writing cease-and-desist letters on the matter. In fact, responding to preemptive Twitter attacks from Directioners, both Pete Townshend and members of Def Leppard took the time to announce they wouldn’t sue the band.

Theft, tribute, remixing are essential elements of pop, of course—especially in 2015, when technology has made the past more accessible and nostalgia more profitable. And it’s worth appreciating that there’s a kind of novelty in One Direction’s music. The influences they raid—Baby Boomer guitar bands, mostly—aren’t the same as the ones raided by other chart-toppers at the moment, and no one else reliably serves quite the same mix of candylike melodies, multipart harmonies, cheeky attitude, and grinning self-awareness.

Made in the A.M. is the group’s first album after the departure of Zayn Malik, and the last one before a planned hiatus. Accordingly, there’s a bit of a wistful, mourning vibe throughout—ballads galore—which is perhaps not One Direction’s best mode, even though the “Bittersweet”-biting of “Hey Angel” is quite pretty. The fun moments are very fun, though. “Never Enough” zanily takes barbershop a cappella and adds stadium shouting; the next track, “Olivia,” is the Beatles after an energy drink; “What a Feeling” revisits the groove from Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams,” which is never a bad thing. The most uproarious pastiche, though, is the most mind-meltingly meta one: “Perfect” is basically a cover of Taylor Swift’s “Style,” which itself was an ’80s throwback whose lyrics appeared to be about One Direction’s Harry Styles. Now, Styles is singing back at her on her own beat. Does originality matter when the drama is this delicious?

But anyone who finds all this recycling and referentiality a distressing sign of stagnancy in pop music can cheer themselves up with—don’t laugh—the new Justin Bieber album. Released the same day as Made in the A.M. and thereby creating a friendly-rivalry narrative to rile up fandoms and media coverage, it’s the work of a young male star who’s struggled more visibly with fame than the guys of One Direction have—and has responded by pushing himself musically in a way that they never would.

The publicity blitz around Purpose has not been subtle: Whether by weeping at the VMAs, putting crucifix imagery on his album cover, or releasing a single called “Sorry,” Bieber wants people to realize he’s atoning after a few years of purple-sweatshirt “swagginess” and teenage hijinks. Humbler, more overtly Christian, not a kid anymore—you probably can understand the concept without sitting through Purpose’s spoken-word segments and keyword-soup lyrics like “The meaning of forgiveness / People make mistakes / Only God can judge me.” The overdetermined earnestness keeps the album from being as straightforwardly enjoyable as One Direction’s. But the music’s still worth a listen as a rare example of a new sound in pop music.

To be sure, it’s not a radical departure: Veteran songwriters are still involved, and there are still uptempo grooves and aching ballads and exercises in hip-hop drag. But while many of Bieber’s past efforts have been in line with production styles of the moment—insistent, bombastic, neon, dripping with hooks—Purpose is airy, open, and surprisingly restrained. The “tropical house” genre has been invoked to talk about the album, and indeed there are textures and rhythms—merry brass sections, reggae-derived rhythms—that should remind listeners of warm latitudes. But producers like the EDM punk Skrillex, the indie-electronica creator formerly known as Blood Diamonds (now just “Blood”), and Bieber’s confidante Jason “Poo Bear” Boyd wrap those elements with studio gauze to make them feel muted, angelic, and a bit futuristic. Sprinkled about are highly manipulated vocal snippets, little ghost choirs that heighten the otherworldly vibe. The same tricks have shown up on recent albums from Demi Lovato and Ellie Goulding, but Bieber’s version of it is actually more distinctive and less cluttered.

The sound, obviously, suits Bieber’s message; quoth Blood about the song “Sorry,” “The beat is saying moving forward, and apologizing, can be exciting and fun.” But even more than that, the production suits his vocals. Out of all the reasons people hate Justin Bieber, I’d submit that one of the important ones is the sound of his voice—especially when it was more kidlike—in the context of chipper, sing-songy tunes like “Baby.” On Purpose though, his smooth, still-high tone is given lots of space, and he delivers his words slowly. Which is to say, he sounds spiritual, even when he’s not singing about Jesus.

The music’s not all about inner enlightenment and PR rehab, either: Girls figure in, as you’d expect. The loping, electro-reggaeton of “Company,” is undeniable as body music, and Bieber’s seductive crooning is convincing enough. At least two songs—the tick-tocking No. 1 hit “What Do You Mean?” and the clever acoustic R&B of “No Pressure”—could be classified as “consent ballads,” which is another sign of potential evolution in pop music. But the best song dealing with romance might be “Love Yourself.” It sounds like Bieber’s singing by a campfire, with his voice up close to the mic, dewy. But the lyrics are anything but mushy; the song’s directed to someone who exploited him, and the “love” of the title should actually be read as another four-letter word. It’s an old pop genre—the kiss-off—given a twist, offering another bit of evidence that Justin Bieber has become the most interesting big-time pop star of the season.

November 13, 2015

Reports: Several Shot and Killed in Paris

Several media outlets are reporting attacks that killed several people in central Paris on Friday evening.

Report: Several people killed, injured in Paris shooting. https://t.co/m6Mxow3SvZ

— CNN Breaking News (@cnnbrk) November 13, 2015

While the reports have not been officially confirmed, the BBC is reporting that at least one gunman “opened fire at the Cambodge restaurant” in the 11th arrondissement. A BBC reporter on the scene relayed that he or she could “see 10 people on the road either dead or seriously injured.” Le Figaro is reporting that 18 people are dead.

The AP is adding that two explosions were heard from the Stade de France, the country’s national stadium, where France was hosting Germany in a soccer match. The sounds of several exchanges of gunfire and what might have been an explosion were captured on a video on Periscope near the Bataclan club in Paris. Police were also heard directing people to flee the scene.

Agence France-Presse and others are now reporting that there is a hostage situation unfolding there.

#BREAKING Hostages taken at Paris Bataclan concert hall, police say

— Agence France-Presse (@AFP) November 13, 2015

This story is still developing. We’ll have more details as they become available.

A Pro-Democracy Landslide in Myanmar

The movement to challenge more than five decades of military rule in Myanmar received a significant boost Friday when results from the country’s first free elections in 25 years were released.

The overwhelming winner was Aung San Suu Kyi, whose National League for Democracy party (NLD) captured an outright majority in the country’s parliament and is now free to choose its next president.

The extent of the drubbing by the opposition was a major shock given the entrenchment of the military institution, which is still allocated one-fourth of the seats in both chambers of parliament. Suu Kyi, both a Nobel Prize winner and once a longtime political prisoner, has also been constitutionally barred from holding the office of president because her children hold U.K. citizenship.

“Her party’s sweep was so thorough that one candidate who died before the vote still defeated his ruling-party rival,” The New York Times noted.

Despite a gradual loosening of the military’s grip in recent years, concerns remain about whether the junta will truly relinquish power. Suu Kyi’s party previously won elections held in 1990, but the results were invalidated and she was placed under house arrest for 15 of the next 21 years.

Ahead of the results, President Obama called Suu Kyi to congratulate her. However, the readout from the call kept a slightly restrained tenor, a nod to the potential uncertainty of a power-sharing dynamic with the military.

“The two leaders discussed the importance for all parties to respect the official results once announced and to work together in the spirit of unity to form an inclusive, representative government that reflects the will of the people,” the announcement read.

So far, however, the signs are promising. Earlier this week, Myanmar’s military-backed president, Thein Sein, said he would respect the results and the country’s army chief, Min Aung Hlaing, offered that the military would “do what is best in cooperation with the new government during the post-election period.”

The Presidential Race Turns Ever More Bizarre

Wasn’t this supposed to be the week that the presidential race stabilized?

The furor over debate hosting was dead—or at least dormant. The Republican debate in Milwaukee was long on policy and short on personal conflict, and it didn’t seem to offer any real race-changing shifts. Marco Rubio was finally rising to the top of the establishment field, as had long been predicted.

As the week ends, things look very different and far more acrimonious. And unsurprisingly, the catalyst for the chaos—as it has been so many times before—was Donald Trump. First, Trump delivered a rambling 95-minute speech (though is there any other kind of 95-minute speech?) in Iowa, lambasting Ben Carson for factual discrepancies in his autobiography, calling the press scum, and hectoring voters in the all-important first-caucus state: “How stupid are the people of Iowa? How stupid are the people of the country to believe this crap?” Referring to Carson’s story of trying to stab a friend and hitting his belt, Trump offered this:

Then, on Friday morning, the mogul—that’s also his self-chosen Secret Service code-name—released a video attacking Carson as either a “violent criminal” or a “pathological liar”:

A video posted by Donald J. Trump (@realdonaldtrump) on Nov 13, 2015 at 8:07am PST

Trump’s bizarre diatribe has some pundits asking whether he has finally gone too far; but then, people have been saying that since July.

After more than a week of this, Carson is an old pro at responding to this sort of thing—he’s spent a week fending off queries from the media. Carson seems to have in many cases successfully turned the story into a discussion of media ethics and bias. The reason Trump is attacking Carson, of course, is that Carson is the first Republican to seriously challenge Trump’s lead in the polls. (How durable is Carson’s support? There have been no polls released since Tuesday’s debate, but Carson might already have peaked—his numbers have slightly dipped recently:

Many political observers are still confident that neither Trump nor Carson has any shot at the nomination. Among the more standard candidates, Jeb Bush delivered a passable performance at the Milwaukee debate, but hasn’t arrested his slide; John Kasich’s bellicose approach was widely panned. So that leaves Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz battling for support. The smart money seems to be on Rubio—helped by the personal antipathy many in the GOP feel toward the Texas senator.

The result has been a steadily intensifying offensive by Cruz against Rubio. It started in earnest during the debate, where Cruz took a hardline against immigration reform and demanded deportation of unauthorized immigrants. He also took a shot at sugar subsidies. While he didn’t name Rubio in either case, the Floridian was clearly his intended target—he was a central element of the failed push for immigration reform, and is close to sugar executives who want the subsidies to stay in place.

On Thursday, Cruz continued to ratchet up the pressure, telling Laura Ingraham that on the issue of immigration, “talk is cheap.” “You know where someone is based on their action,” he said. “When politicians say the exact opposite of what they've done in office and I'd treat that with a pretty healthy degree of skepticism.”

The Washington Post reports that the continued success of Carson and Trump—to say nothing of Cruz’s resilience—has started to freak out Republican Party mandarins.

The party establishment is paralyzed. Big money is still on the sidelines. No consensus alternative to the outsiders has emerged from the pack of governors and senators running, and there is disagreement about how to prosecute the case against them. Recent focus groups of Trump supporters in Iowa and New Hampshire commissioned by rival campaigns revealed no silver bullet.

How bad are things, really? “According to other Republicans, some in the party establishment are so desperate to change the dynamic that they are talking anew about drafting Romney—despite his insistence that he will not run again.”

It’s hard to imagine that Romney could make it any more clear that he’s not running—and hard to imagine that many Republicans would really be eager to see the return of a man whose campaign in 2012 was widely lambasted, beset by bad messaging, strategic miscues, and technological failures.

This must be comforting to Democrats for a couple of reasons. First, they’d love another shot at Romney. Second, it’s a reminder than the Democratic Party doesn’t have a monopoly on “bedwetters,” David Plouffe’s colorful term for party loyalists who scare easily about the party’s chances and candidates. What’s going on with Republicans seems similar. Despite the turbulence this week, it really does seem to have been a better week for the GOP, and the race is still—yes, still—early.

Democrats, meanwhile, are gearing up for their second debate Saturday night. The first encounter proved unexpectedly friendly: Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton were positively chummy, Martin O’Malley failed to make a dent, and Lincoln Chafee and Jim Webb—well, the less said about them the better, but both left the race for the Democratic nomination soon after. The buzziest moment in the debate came when Sanders assured Clinton, “The American people are sick and tired of hearing about your damn emails!”

Since then, the Democratic race seems to have stabilized a bit—and not in ways that Sanders likes. Clinton’s polling nationwide ticked up, she gained on Sanders in Iowa, and some polls showed her back neck-and-neck or even ahead of him in New Hampshire. That’s led the Vermonter to take a more aggressive tack against her. He’s begun pointedly criticizing her and his team says he’s ready to do more Saturday. It’s a risky strategy for Sanders: His campaign has been built in large part on his nice-guy appeal, so going after Clinton could either reverse the trend and improve his numbers, or it could accelerate his return to earth.

Clinton has other worries besides Sanders. After her commanding performance before the House select committee on Benghazi, questions about her email faded a bit from view. But reports this week from Politico and Fox News suggest that investigations are ongoing, and could still do serious damage to her.

That’s the 2016 race so far, in a nutshell: Even the boring weeks turn out to be pretty exciting.

How Home Alone Ruined John Hughes

In a three-year period during the 1980s, John Hughes solidified his place as the great teller of adolescent tales on film. Five years ago, Vanity Fair noted the irony in the fact that “a baby-boomer born squarely in the middle of the 20th century had somehow laid claim to the title of Teen Laureate,” after writing, producing, and in some cases directing odes to teen angst including Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. Those movies are part of an oeuvre that have led the likes of Tina Fey and Judd Apatow to cite Hughes as an influence or pay homage to him on screen, and that make him beloved by both Gen Xers and Millennial figureheads like Taylor Swift. For many, Hughes captured the experiences of young people with the kind of empathy and nuance no other filmmaker had before.

1990 marked the beginning of a particularly lucrative time for Hughes with the release of his biggest film to date. A departure from the teen movies that made Hughes famous, 1990’s Home Alone would nonetheless go on to be the third highest-grossing film ever at the time. This was thanks to a simple formula: Take a precocious, adorable, misunderstood kid, put him in a situation where he can get into good old-fashioned trouble, but make sure everything turns out alright in the end (Hughes would later use this formula for dogs as well).

Home Alone succeeded because the heavy doses of schmaltz and whimsy necessary for a family film were balanced out by the slapstick violence. Macaulay Culkin’s Kevin McCallister doesn’t come of age or really learn much besides how to aim paint cans at the heads of the two burglars trying to break into his house—but he does have to take on grownup responsibilities until his parents get back. While he gets to set up a number of elaborate booby-traps throughout his house, he also has to buy groceries and cook for himself. After all that, it seemed like Kevin could just return to his old life. But the man who created him found it harder to do the same after Home Alone’s massive success.

After the success of Home Alone, Hughes’s movies noticeably changed their focus to appeal to a broader audience. They grew more polished, but missed the originality and distinct appeal of his earlier works. Home Alone signified a change of direction for Hughes, and a shift in focus away from the fertile terrain he’d explored in his earlier films. While the McCallisters live in the Chicago suburbs where nearly every other Hughes film is set, the conceit is notably different from the more formulaic films of the 1980s (starting with 1984’s Sixteen Candles and continuing through 1989’s Uncle Buck).

Hughes himself said that he envisioned his characters all living in the same universe, the fictional town of Shermer, Illinois (based largely on the Chicago suburb of Northbrook where Hughes lived as a teenager). But the world of Home Alone doesn’t bear any resemblance to the Shermer of his other films; it was filmed and takes place in the real village of Winnetka along Lake Michigan. In many ways, it’s Hughes leaving Shermer behind.

* * *

The triumph of the first Home Alone movie marked the end of Hughes’s great run, one that included three National Lampoon’s Vacation films starring Chevy Chase and Beverly D’Angelo, the teen movies, and Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. Those films, untouchable by many standards, helped redefine comedy, but they didn’t make nearly as much money as Home Alone did. For a comparison, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, one of Hughes’s most successful films both financially and critically, made an admirable $70,136,369 when it was released in 1986. Home Alone had a final gross of $285,761,243 just four years later.

Financially speaking, it probably would have been difficult for Hughes to go back to making those kinds of films, the ones with curse words and teenagers realizing they were on the terrifying cusp of adulthood. A scathing 1992 article by Richard Lallch for Spy magazine took a behind-the-scenes look at what it was like working in “Hughesland” just two years after Home Alone came out. The piece portrayed Hughes as a “crazed, scary, capricious bully” who was “getting at least $10 million a year to crank out consistently mediocre money losers.” Hughes Entertainment wasn’t the seemingly fun and loose hangout that you imagined his earlier films coming from, but after a string of failures all released in 1991—Career Opportunities, Only the Lonely, Dutch, and Curly Sue—Lallch surmised that Hughes “badly” needed a hit. The result? Home Alone 2, which netted $173 million in the U.S. alone.

Over the following decade, Hughes went on to write and produce critical duds like the 1993 adaptation of Dennis the Menace, 1994’s Baby’s Day Out, and a quirky but forgettable remake of The Absent-Minded Professor starring Robin Williams, 1997’s Flubber. None of these films resonated the way his earlier works did, but they made a lot of money (1996’s 101 Dalmatians netted $136,189,294, while Flubber took in $92,977,226). But there are some bright spots in Hughes’s post-Home Alone filmography, like the film’s sequel and the surprisingly dark and sad 1994 remake of Miracle on 34th Street that Hughes wrote and produced.)

Many artists enjoy creative golden ages before hitting a peak, or a plateau, or fizzling out entirely. So why is Hughes’s decline so exceptional? After all, he’s not a critical heavyweight like Alfred Hitchcock, he’s not associated with any film movement, he never won any major awards for his work, and he was never quite an indie darling. Hughes was always commercial to an extent, something that shouldn’t be too surprising since he was writing copy at major advertising agencies before he got into film. And yet his movies are seen as definitive tales of the ’80s, proof that Hughes had something special to offer audiences.

Hughes was a writer before all things; for him, the story came first. But after Home Alone, he just relied on that same formula, or worked on adaptations and remakes that already had built-in stories. In other words, there wasn’t as much to create, which might explain why his ’90s output just doesn’t hold up as well as his work from the previous decade. Hughes himself said he was disillusioned by his time spent in Hollywood; his post-Home Alone success gave him a chance to move on. And yet he hadn’t lost his creativity: According to David Kamp’s Vanity Fair piece, the hyper-prolific Hughes left behind hundreds of notebooks filled with new stories, some completed, others just the seeds of ideas.

His movies are seen as definitive tales of the ’80s, proof that Hughes had something special to offer audiences.There’s ample reason to wonder how Hughes and his work would be viewed if he’d gone down a different path and not simply chased the broad box-office appeal. There’s an undeniable urgency and energy to the movies from the 1980s that bear his name that you just don’t find in his later work. The formula he came up with for Home Alone, the one he found the most success with, was structurally sound and easy to replicate, but ultimately empty. It’s Frank Whaley and Jennifer Connelly in Career Opportunities forced to defend a Target store against two dimwitted robbers, Dennis the Menace doing battle with a burglar named Switchblade Sam, the baby in Baby’s Day Out outsmarting three kidnappers, and the very forgettable third Home Alone film.

Though his teen films continue to have an indelible hold on pop culture today, it’s Home Alone that might ultimately be Hughes’s most enduring movie. It spurred studios to clamor for high-yield, family-friendly movies while elevating the man who directed it, Chris Columbus. Hughes passed the torch to Columbus, whose greatest success before 1990 was Adventures in Babysitting—a film people often wrongly associate with Hughes because it’s a story about teens in Chicago in the 1980s and features a Hughesian happy ending.

After directing the first two Home Alone films, Columbus went on to make hits like 1993’s Mrs. Doubtfire and 1996’s Jingle All the Way. He also kicked off the aughts by directing the first two Harry Potter films, and much like Hughes, he stepped out from behind the camera and into the role of producer for the third installment of the boy wizard’s story. Yet with his string of popular all-ages films, Columbus succeeded at making great post-Home Alone movies where his mentor failed. As Jed Gottlieb pointed out in Paste, Columbus presented the stories of Potter and his friends with the same “honesty, insight and humor” as Hughes did in the 1980s.

Hughes’s influence on Columbus can be felt throughout the biggest film franchise of the century so far. So although his career following Home Alone might be interpreted as a disappointment given the brilliance of his earlier films, his legacy is undeniable. Perhaps that, more than anything else, can be of some solace to fans who wonder what might have been.

Brooklyn: A Personal Tale of Immigration

From its first moments, Brooklyn is both helped and blunted by its accessibility. John Crowley’s adaptation of Colm Tóibín’s novel about a young Irish immigrant’s journey to America and struggle to acclimatize is a restrained, lovely work that’s low on thrills and spills. The story of Eilis Lacey isn’t suffused with the kind of impoverished anguish one might associate with stories of postwar immigration, but it still doesn’t lack for emotion and quiet wit, rendered sensitively by Crowley and the screenwriter Nick Hornby and anchored by a confident lead performance from Saoirse Ronan as Eilis, who saves the film whenever it threatens to veer into formulaic territory.

Related Story

Wild: A Deeper, Smarter Sob Story

That’s a frequent risk, given how straightforward Eilis’s story is. A smart girl trapped in a mundane town in economically depressed Ireland, she leaves her mother and sister to move to Brooklyn with the sponsorship of her local parish. She goes to night school to become a bookkeeper, stays at a boarding house with a clucking, well-meaning matron (Julie Walters, who can do this in her sleep), and eventually meets a nice Italian plumber named Tony (Emory Cohen) who clumsily tries to sweep her off her feet before realizing she’s too level-headed for all that. Though homesickness pulls at her heartstrings, Eilis is not a tormented figure, but she is a universal one: She’s caught between her comfortable, traditional upbringing and the land of opportunity.

In a less experienced actress’s hands, Eilis might seem vapid or dull—she always takes a few seconds to react to every query lobbed at her, processing each new life experience through the many filters of guilt and cautiousness she’s built up through her journey to America. But Ronan has been holding the camera to rapt attention since her astonishing debut as the mercurial young Briony in 2007’s Atonement, and she imbues Eilis with warmth and ambiguity. Her romance with Tony is hardly swooning, but sweet; you can tell that Eilis is herself unsure of whether she loves him at first, or merely appreciates the company he’s brought to her previously lonely life. This could feel like an airport romance novel about a girl whose life is transformed by love, but Ronan complicates Eilis’s otherwise simple story arc as much as she can.

Hornby’s script is a loving adaptation of Tóibín’s hit book that thankfully steers clear of every Irish immigrant stereotype imaginable (with this and 2014’s Wild, he’s on a roll when it comes to turning other people’s books into films). Yes, there’s a kindly priest (Jim Broadbent) and a scene where a homeless man sings a folk song in beautiful Gaelic, but Crowley never leans into the obvious. The Ireland that Eilis leaves behind isn’t some squalid, rain-soaked backwater; rather, it’s a dull but well-kept country town, insidious only in the lack of opportunities it represents. Eilis doesn’t yearn to journey to America in search of freedom, but has to be nudged to leave by her family who want the best for her; a later plot turn that sees them try to lure her back is motivated by their own understandable selfishness rather than malice.

Still, the film starts slow and ends even slower. Eilis’s journey to New York and early months settling in are light on action and heavy on her vague melancholy and homesickness, and it’s only once she meets Tony that some real stakes get introduced. But Brooklyn is still very much worth its running time. It’d be foolish not to praise a film that shows this much restraint in telling such a common story and places its entire weight on the shoulders of a well-drawn, empowered female protagonist who nonetheless feels congruous with the times. This is no sweeping, big-budget epic; rather it’s a small story with bearing on the experiences of millions more, and it gets that across without ever losing sight of the personal scale on which it’s being told.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower