Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 292

November 20, 2015

Mali’s Tangled Mix of Jihad and Civil War

A hostage situation in Bamako, Mali, has ended with at least 18 people killed. Details are still streaming in, and much of what has been reported is still tentative. My colleague Adam Chandler has a running post on the facts so far.

The attack has drawn new attention to the West African country, but it’s just one milestone in a long-running conflict that has included a separatist civil war, a split between Islamist allies, a large foreign-military operation, and a comeback by jihadists. Even while Friday’s siege was ongoing, questions arose about whether the Bamako attacks were at all connected to last week’s Paris attacks by the Islamic State, or if they were intended as retaliation for French military intervention in Mali in 2013—just as ISIS portrayed the November 13 attacks in Paris as vengeance for French airstrikes in Syria and Iraq. But there are many facts still unknown, and the situation in Mali is too complicated to allow any simple answers.

Mali is shaped like an uneven bow tie, with Bamako and much of the nation’s population in the smaller, southwestern triangle. The upper, northeastern triangle is more sparsely populated, and includes a swatch of the Sahara Desert. Tuareg people living there have long resisted the Malian government’s control. Their decades-long, low-level rebellion gained firepower in early 2012, as arms streamed across the Libyan border after the death of Muammar al-Qaddafi. In the spring, as an army coup toppled the central government, the Tuareg separatist Mouvement National Pour la Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) declared independence, saying it had formed a new state called Azawad.

Related Story

Hostage Crisis in Mali: What We Know

The MNLA, which includes many secular Tuareg, was bolstered by its alliance with Islamist fighters with ties to al-Qaeda. But the MNLA soon found it was unable to contain its allies. The Tuaregs were pushed aside and some became refugees. The Islamists began imposing an extremely harsh style of rule in northern Mali, forcing many people to flee the area and suppressing those who stayed behind. They destroyed historical shrines and records in Timbuktu, capturing the world’s attention briefly. By January of 2013, The New York Times was counting at least six different Islamist groups operating in northern Mali, including Tuareg-led Ansar Dine, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa.

Having established their power in the north, the now-jihadist-dominated rebels began marching southward. At that point, France sprang into action, driven in part by its colonial ties to the country. The military offensive it launched soon proved successful at dispersing the rebels. There are now some 3,000 French soldiers in the region.

France’s military victory was fast, but perhaps fleeting. The United Nations took over security from the French, but a year later, in March 2014, The Guardian reported that jihadists had slowly begun to creep back into northern Mali. Paul Melly, a Francophone Africa expert at Chatham House, told the BBC Friday morning that the French intervention had successfully scattered the Islamists, but it hadn’t eliminated them, a challenge made harder by geography.

“Jihadist groups dispersed across the desert,” he said. “In the Sahara, it’s very difficult to control people moving around.” They were also able to resupply their stores of money and weapons from Libya, Melly said: “This has sustained jihadist terrorist over the years since that major French intervention.”

“Jihadist groups dispersed across the desert. In the Sahara, it’s very difficult to control people moving around.”The civil war officially ended in June with a signed agreement, but the jihadist forces summoned by the conflict were not gone. They had just turned into a much more decentralized, splintered Islamist movement, which has launched attacks around the country throughout 2015, including some that have reached well into southern Mali. June also brought reports of the death of Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a one-eyed Algerian and leading jihadist figure in the Sahara (he lost an eye in the Algerian Civil War). Belmokhtar is most famous for the January 2013 siege of a gas facility in Algeria, which was carried out by militants in his command. Around 40 people were killed and 800 were taken hostage.

Belmokhtar was a top al-Qaeda commander, but he eventually split from the group over management disagreements. His new organization later merged with the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa to create a group called al-Murabitun. And he apparently patched over his differences with AQIM, because the group released a statement saying he was “alive and well” in June. Belmokhtar’s group has since claimed responsibility for some attacks on behalf of al-Qaeda.

In August 2015, militants attacked a hotel in Sevare, a city in central Mali. The assault presaged Friday’s attack in some ways. A band of gunmen stormed the hotel, where some UN officials were staying, and seized hostages. Thirteen people, including five UN workers and four Malian soldiers, died before the siege was ended. Al-Murabitun claimed credit for that attack. The group also claimed responsibility for a deadly May shooting at an expat bar in Bamako.

Al-Murabitun has now taken credit for the attack Friday at the Radisson Blu in Bamako, though officials have not confirmed the connection. There’s also no evidence so far to tie the attacks to ISIS. Melly told the BBC he was not aware of ISIS being active in Mali. Jean-Hervé Jezequel of the International Crisis Group is similarly cautious:

If [ISIS] turns out to be linked to the Bamako raid, it would be the first time that movement has taken action or been seen to be present there. IS certainly has no official representative or presence in Mali, even if there were rumours this summer that some radical leaders active in the north were looking for an IS affiliation.

One result of the complicated and tangled jihadist landscape in Mali is that figuring out who’s allied with who can be tricky. It’s not just the split between MNLA and their Islamist allies, and not even just Belmokhtar’s on-again, off-again relationship with al-Qaeda. Earlier this year, someone claiming to speak for al-Murabitun announced that the group was pledging its allegiance to ISIS. Several days later, Belmokhtar shot down that report as false.

The Man in the High Castle’s Chilling Alternate Reality

The premise of The Man in the High Castle is undeniably fascinating. What if Hitler had won the second world war? What if America had been conquered by the Axis powers, and partitioned into a German-occupied east and Japan-controlled west? Amazon Studios’s newest show, based on Philip K. Dick’s 1962 virtual-history novel of the same name, is just as strange and horrifying as the dystopian classic, vividly realizing the what-if world Dick created.

Related Story

The Man in the High Castle: When a Nazi-Run World Isn't So Dystopian

Developed by Frank Spotnitz (best known for his many years of work on The X-Files), The Man in the High Castle is a fairly loose adaptation of Dick’s novel, taking in the entire scope of the Americas rather than just focusing on Japanese-controlled San Francisco and the “neutral zone” in the Rocky Mountains, as Dick did. Set in the 1960s, this is a world with swastika marquees in Times Square and a discomfiting (though obliquely remarked-upon) amount of racial harmony. It’s a world where a graying Hitler, now in his 70s, helps maintain a fragile peace with Japan that many think will expire upon his death. On a macro-scale, the series is absorbing, but it takes a few episodes to settle into the smaller stories that are unfolding.

The show’s hero is Juliana Crain (Alexa Davalos), a San Franciscan who gets sucked by her sister into a larger rebellion against the Axis occupiers. On the run from police, she ends up in the neutral zone with Joe Blake (Luke Kleintank), another rebel with secrets of his own (revealed at the end of the pilot episode, which Amazon first aired last January before picking up the series). Juliana knows Aikido and is introduced as a smart action heroine—an impression that’s undercut by her looking constantly confused as she’s swept up by events she doesn’t understand in the early episodes. Meanwhile, the most compelling thing about the square-jawed Joe is his secret, which takes a while to pay off.

Much more interesting is the alternate-history cold war developing between the Nazis and the Japanese, explored through high-powered figures like Nobusuke Tagomi (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa), a Japanese trade minister, and John Smith (Rufus Sewell), the head of the New York SS who’s trying to bring down the anti-Nazi movement. The show does a clever job of showing how rewriting history tends to create new monsters. Sewell in particular is terrifying as Smith—an American raised in a world of tyranny, the only thing distinguishing him from the countless Nazi villains of pop culture is his accent.

This is a world with swastika marquees in Times Square and a discomfiting amount of racial harmony.One of the themes Dick explored in his novel was the depressing sameness of post-nuclear geopolitics regardless of who the global actors are. Spotnitz seizes the opportunity to pick apart the mundane pragmatism of supposedly evil men, drawing fascinating parallels with real-life 20th-century history in his funhouse-mirror universe. As such, Tagomi finds himself caught up in covert efforts to stop Japan and Germany from going to nuclear war with each other over the occupied Americas. As the series progresses, other major plot points start to resonate with reality, despite unfolding in a surreal world.

It makes sense that The Man in the High Castle divides its time between political power players and the citizens whose lives they’re affecting. But outside of Sewell there are no dynamic performers here, and the hour-long episodes afforded by streaming television lead to some dull scenes that may leave viewers feeling antsy. Still, it’s remarkable to see a show like this on TV. There are moments where Amazon’s budget limitations show through—John strolls past a couple of CGI cityscapes that look like obvious green-screen inserts—but the overall attention to detail is admirable, and would have been unthinkable for a television series just a few years ago.

You can tell why Amazon has dedicated its resources here, too: The world of The Man in the High Castle unfolds best as a season-long binge-watch, adding strange, colorful details with every hour. It’s always a challenge to find an original way to depict the evil of Nazism, but the show feels up to the task. The future depicted is simultaneously banal and outlandish—a repressive police state, but one where men in Nazi uniforms appear on cheerful game shows. It’s that originality, building off the arresting premise, that stands out most of all.

Is Donald Trump Serious About Registering Muslims?

Updated on November 20 at 2:10 p.m.

Being Donald Trump means, among other things, never backing down and never saying you’re sorry. He is a Mitt Romney book title come to life.

On Thursday, Yahoo News published an interview in which Trump seemed to assent to reporter Hunter Walker’s suggestions of requiring Muslims to register in a database or giving them a form of special identification attached to their religion. Walker wrote, “He wouldn’t rule it out.” Trump’s own comments were much vaguer: “We’re going to have to—we’re going to have to look at a lot of things very closely. We’re going to have to look at the mosques. We’re going to have to look very, very carefully.”

Trump’s defenders, and some folks who also aren’t Trump defenders, felt this was a little unfair. After all, Walker had fed the ideas to Trump. Were they really Trump’s? It doesn’t seem like too much to ask that Trump repudiate ideas like this, but gaffes happen.

Trump demolished that defense Thursday night. He declined the chance to walk back his comments. At an event in Newton, Iowa, NBC asked him whether there should be a database to track Muslims. “There should be a lot of systems, beyond databases. We should have a lot of systems,” he said.

Then, a reporter asked him how such a system would be different from Nazi Germany mandating the registration of Jews. “You tell me, you tell me. Why don’t you tell me,” Trump replied.

Trump sure doesn’t lack political courage. It’s not uncommon for politicians and operatives to accuse their rivals of espousing Nazi-like ideologies, but it’s hard to remember a time when a supposedly mainstream candidate had no interest in differentiating ideas he’s endorsed from those of the Nazis.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the U.S. Holocaust Museum waded into the debate with a press release on Thursday:

Acutely aware of the consequences to Jews who were unable to flee Nazism, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum looks with concern upon the current refugee crisis. While recognizing that security concerns must be fully addressed, we should not turn our backs on the thousands of legitimate refugees.

The Museum calls on public figures and citizens to avoid condemning today’s refugees as a group. It is important to remember that many are fleeing because they have been targeted by the Assad regime and ISIS for persecution and in some cases elimination on the basis of their identity.

Trump’s antics would seem to be politically suicidal. Who wants to vote for the guy who can’t say how he’d be different from the Nazis? But throughout the campaign, Trump has defied every expectation about what a candidate could say without being banished from polite society, much less the leading position in the Republican Party’s nomination contest. Like clockwork, an NBC poll released Friday morning finds Trump retaking the lead by a wide margin over the balance of the GOP field.

Update: Trump tweets Friday afternoon that these aren’t his ideas; they came from someone else:

I didn't suggest a database-a reporter did. We must defeat Islamic terrorism & have surveillance, including a watch list, to protect America

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 20, 2015

But does he still think they’re good ideas? He hasn’t said anything to suggest otherwise.

Mockingjay—Part 2: A Dull Slog to the Bitter End

Perhaps the greatest surprise of the Hunger Games franchise to date had been the degree to which the films reversed the quality trajectory of the books. The first novel in Suzanne Collins’s trilogy was the best, with the second moderately worse and the third considerably so. The movies, however, got better and better from first to second to third. (The final book was split into two installments, as is the fashion post-Harry Potter.)

Alas, that trend has now been arrested. The Hunger Games: Mockingjay—Part 2 is the least enjoyable of the films by a considerable margin, a dull, grim, slow-moving slog. The plot, for those unfamiliar with it, involves the final assault on the repressive Capitol by Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) and her rebel companions. Katniss and her squad are sent by the rebel leader Alma Coin (Julianne Moore) on what’s supposed to be a relatively safe propaganda mission in areas of the Capitol already pacified by rebel troops. But Katniss’s nemesis, President Snow (Donald Sutherland) has seeded the city with deadly “pods,” containing everything from machine guns to flamethrowers to a tidal wave of oily goo—effectively turning the Capitol itself into another iteration of the “Hunger Games.” “Our gamekeepers,” he cackles, “will make them pay for every inch with blood.”

This storyline, lifted straight from the novel—the apparent idea having been that each volume of the trilogy must have its own Hunger Games of one sort or another—is decidedly ridiculous, and I’m not sure how it could have been rescued without wholesale re-writing. (Obviously, not an option.) But the director Frank Lawrence (no relation to Jennifer) and the screenwriters Peter Craig and Danny Strong do themselves few favors in this outing.

When Lawrence signed on as director before the second installment of the franchise, he (along with his leading woman) brought a moral heft to the proceedings that had been lacking in the first film. His Hunger Games films weren’t merely about a tournament in which children kill one another, they were about repression, revolution, and war on a broad scale. And while those themes are still present in Mockingjay—Part 2, they’re in scarce evidence onscreen. Instead, the movie has narrowed into a tale of a single band of (mostly) young people, lurching from one danger to another. The fact that a substantial portion of it takes place underground—Katniss’s team take to the urban tunnels of the Capitol to get away from the pods—only adds to the claustrophobia.

Scene after scene is held one, two, three beats too long, in an effort to advertise its Great Moral Importance.Moreover, this installment of the saga, the grimmest of the series by far, didn’t need the additional solemnizing that Lawrence brought to its predecessors. Quite the contrary: It could have benefited from an infusion of levity and/or velocity—two qualities conspicuously lacking. Scene after scene is held one, two, three beats too long, in an effort to advertise its Great Moral Importance. The result is a movie that is too silly to be so somber, and too somber to be much fun.

The action sequences are muddy and confused, and the lulls between them—which consist largely of tedious speechifying and long bouts of remorse and recrimination—interminable. The love triangle between Katniss, Peeta (Josh Hutcherson), and Gale (Liam Hemsworth), downplayed in the other films, is heavy-handedly restored to center stage. (Particularly painful is a scene in which Peeta and Gale compare the varying degrees of authenticity of the kisses they’ve received from Katniss.) And the final 20 minutes or so suffer from acute Return-of-the-King-itis, with narrative postscript following narrative postscript following narrative postscript.

Several principal characters from the previous films—Woody Harrelson’s Haymitch Abernathy, Elizabeth Banks’s Effie Trinket, Stanley Tucci’s Caesar Flickerman—make only token appearances in this outing. But it’s the near-absence of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, who died during filming, that is most keenly felt. His ability to ground the series with understated irony was a crucial component of the earlier films’ success. (It borders on cruel that the last we hear from his character, Plutarch Heavensbee, is a letter delivered to Katniss that reads, “I wish I could have given you a proper goodbye.”)

Should committed fans of the franchise go see Mockingjay—Part 2? Of course they should (though perhaps with tempered expectations). Lawrence, as always, makes for a compelling Katniss, and this is, after all, the completion of a long journey. Which is ultimately, I suspect, part of the problem. This is a movie so busy being a final chapter that it frequently forgets to be a movie.

#ActualWorst, Round Three: Marnie Michaels vs. Fitzgerald Grant

Throughout the month of November, we’re soliciting readers’ help to definitively answer an age-old question: Who is the actual worst character on television? We reviewed your submissions, did our own research, and came up with a list of 32 characters across four different categories, who’ll go head to head over the next four weeks until one of them is crowned as the most despicable, unlikable, flat-out awful (fictional) person on the small screen.

This bracket, while intended to determine the relative awfulness of characters on television, is subject to the fact that “worst” is a complex superlative that can incorporate a number of different qualities. In no way are we suggesting that being a narcissistic 20-something is equivalent to, say, killing people and eating them. Rather, our goal is simply to map out which of these fictional characters we love to hate and which we hate to love.

See the bracket in its entirety here.

The Case for Marnie (Girls) HBO

HBO Why this character is the actual worst: When people use “pretty girls” as an epithet, they’re talking about girls like Marnie Michaels. She’s a high-strung, annoying perfectionist who jumps to judge others, while her own life is a professional and moral mess. She manipulates men into having sex with her out of insecurity, including at least two of her best friends’ ex-boyfriends. Worst of all, she’s fake, offering false-toned apologies and always performing for those she’s trying to impress.

Worst moment/s: Being drawn in by the artist Booth Jonathan with the worst pick-up line in all of history; singing a ballad-version of Kanye West’s “Stronger” at her newly successful ex-boyfriend’s work party to get his attention; every time she sleeps with someone else’s boyfriend. And: Marnie and Desi.

Worst trait/s: She’s taken with fame, flattered easily, and willing to make a jerk of herself to win approval—mostly from (really lame) men.

Redeeming moments/qualities: In spite of herself, Marnie can be generous. She’s the first of the girls to be really patient with Shosh; she pays Hannah’s apartment bills. They’re rare moments of non-self-absorption, but they’re redeeming. —Emma Green

The Case for Fitz (Scandal) ABC

ABC Why this character is the actual worst: It’s impossible to beat Linda Holmes’s case for why Fitz is the worst, or Alyssa Rosenberg’s, or Kid Fury’s. Let’s just recap thusly: Fitz is an overprivileged, murderous, man-shaped infant whose libido dictates his foreign policy. As punishment for manipulating the engines of democracy to get him elected, his friends and associates have had to spend his presidency coping with his soul-deep corruption, petty jealousies, and severe allergy to anything that looks like accountability. He has, essentially, everything he’s ever wanted, yet he insists on more, thereby ruining the lives of everyone he says he loves.

Worst moment/s: Sending American troops to war in a bid to save Olivia’s life. Going to the hospital to visit an old friend about to die from cancer, just so he could murder her instead. The fact that he cheated on his wife with at least two different women barely even rates a mention in the long catalogue of Fitz’s sins.

Worst trait/s: He’s one of the richest, most powerful people in the world, with two gorgeous women vying for his affections. Yet this is his only expression.

Redeeming moments/qualities: Olivia and Mellie both out-league Fitz, but he’s nice to look at, preferably without sound/his shirt. —Matt Thompson

The Humanity of Adele's 25

The world has problems, but pop music in the 2010s for the most part only has confidence. Rihanna, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, and Taylor Swift have spent the last few years shaking off haters while popularizing alliterative affirmations—fierce, fabulous, flawless—that have been inherited by a 2015 class of even happier warriors. Hailee Steinfeld: “I love myself!” Rachel Platten: “This is my fight song!” Demi Lovato: “What’s wrong with being confident?” Even when these singers are down, overcoming is usually just a chorus away.

Adele is different from all these people for a lot of reasons, most of which are subsets of the fact that she doesn’t make dance music. Even more important, though, may be the fact that for Adele, overcoming is almost never the point. Wallowing is. Owning your self-loathing is. On her new album 25, she sounds great—her voice is somehow more powerful than ever—but she almost never sounds like she thinks she’s great. In fact, she thinks that she’s terrible, worthless, unlovable. Which is striking, given that her last album sold a lot more than anyone else’s did this decade. 25 won’t repeat that achievement after the pre-release hype dies down: It’s too unsure, too slow, too introspective. But it will surely help a lot of people through hard times.

When it hit the Internet, “Hello” was widely heralded as Adele’s victory lap, which was fair: That slowly cresting, shiver-inducing chorus reminded people of what she can sing and others can’t. But it was also a document of torrential self-deprecation. She’s picking up the flip-phone to apologize, even though she realizes the person she’s apologizing to has mostly forgotten about her. She says she’s embarrassed she talks about herself so much. What’s she sorry for? Oh, just “everything that I’ve done.” No wonder Greg Kurstin included a bell toll in the mix. The kind of guilt she’s dealing with is the kind you go to church for.

Throughout 25, she’s singing up: The “you” she addresses is almost always someone she admires and respects, even if it’s an ex who did her wrong, even if it’s a guy she’s about to leave. The entire first verse of “When We Were Young”—a thinner, weaker “Hello”—is about her working up the courage to approach an old flame who “everybody loves.” Finally, she applies the overapologetic-female-meme to a classic pickup scenario: “If, by chance, you’re here alone, can I have a moment?” The song is another version of the revisitation narrative of “Someone Like You”—she nearly quotes that song’s title—but this time, there’s no “never mind, I’ll find someone else” portion. There’s only her begging for a photo, because she’s worried the future won’t ever be as good as the past was.

That same fear of tomorrow shows up again on the wrenching album highlight “All I Ask,” where, over gently upwards-swirling piano, she repeats a bombshell of a question: “What if I never love again?” That line calls to mind something she told Jon Pareles at The New York Times about the difference between 25 and its predecessor: “How I felt when I wrote 21, I wouldn’t want to feel again. It was horrible. I was miserable, I was lonely, I was sad, I was angry, I was bitter. I thought I was going to be single for the rest of my life. I thought I was never going to love again. It’s not worth it.”

What’s strange is that 21 now sounds relatively peppy. On that album, breakup anger and hurt burned like fuel, powering not only her singing but also the drums—marching and militant on “Rumour Has It,” thumping and crashing on “Rolling in the Deep”—and the hooky, insistent songwriting. For 25, though, there are lots of slow songs, some of which (“Remedy,” “Love in the Dark”) are memorable only because of Adele’s performance. Others rely on interesting juxtapositions. For “Million Years Ago,” she uses the backdrop of Spanish guitar and a familiar torch-song melody to deliver some of the most indelible vocals of her career. The subject is, again, existential regret and shame, but the soul of the song, and maybe the record, is in how she seems on the verge of a sob when singing, “It’s like they’re all scared of me.”

She’s essentially saying she was born this way—unconfident and flawed, probably like most of the people listening.I hear four potential new hits, none as big as anything on 21. There’s the roiling, night-black “I Miss You,” a sex song that’s too bombastic to actually be sensual but will work really well in a dystopian movie trailer. There’s Max Martin and Shellback’s “Send My Love (To Your New Lover),” a playful, faintly hip-hoppy sibling of Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space,” offering the one moment when Adele is righteous towards an ex—though that’s only on the way to forgiving him. There’s the album-closing “Sweetest Devotion,” a self-consciously saccharine ode to eternal (probably maternal) love that blossoms with zig-zagging melodies and somehow evokes “We Are the Champions” in the chorus.

And there’s “River Lea,” a sumptuous gospel song produced by Danger Mouse. It includes a few exquisite examples of Adele trash-talking Adele, including one verse in which she apologizes to someone “years in advance” of whatever horrible crime she expects she’ll commit. But instead of merely relaying her discontent, she analyzes it, looking for the original source. “I blame it on the River Lea, the River Lea,” goes the chorus, the last syllable undulating like the body of water it references, the body of water she grew up near. She’s essentially saying she was born this way, baby—unconfident and flawed, probably like most of the people listening.

November 19, 2015

Enya Is Back to Soothe a Troubled World

It seems somehow insufficient to describe Enya as a singer—just as it wouldn’t be right to describe, say, Jesus as a charismatic fella with a gift for storytelling. Enya is: a gravitational force from the Emerald Isle who’s dominated the world-music charts for several decades, a mysterious sprite who lives in an actual castle, the melodic accompaniment of choice for slightly crunchy Boomers. Enya is also: a synonym for uncool music, South Park’s source of despair, and the soundtrack to a perturbing, vaguely New Age-infused period in the ’90s when the Irish Tiger was roaring. (Michael Flatley was stomping all over Broadway, Pierce Brosnan was James Bond, and Bono was saving Africa with neon-tinted spectacles and Project Red™-branded goods. It wasn’t culture’s proudest moment.)

All that acknowledged, there’s something enormously soothing about Enya’s music—possibly because it sounds like a humanized version of the whalesong they play when you’re getting a massage, or because her lyrics are poetic gibberish, or because her slightly distorted vocals make it sound like Mother Earth herself is struggling to be heard over the bells and the 57 violinists playing the same note. On the new Enya album, Dark Sky Island, there’s a song called “The Forge of the Angels,” and indeed that’s what it sounds like—as if a fleet of haloed beings are making things out of celestial iron while Enya breathes one syllable over and over again and a particularly clumsy piano player tries to master the three notes he’s been tasked with repeatedly adding to the mix.

This is the first new Enya album in seven years. Her last record, 2008’s And Winter Came …, sold more than three million copies, not just because Enya’s been savvy enough in recent years to release all her music right before Christmas so people can buy it for their elderly relatives. And Winter Came … even featured cover art of Enya in a long white ballgown, standing in the snow and holding on to a pure white horse, its mane braided into magical knots. “Aurally, it’s like curling up in front of a log fire with a glass of your favorite Amontillado,” wrote the BBC, proving that Enya’s power subdues even the mighty critical heft of Britain’s most cherished institution. Maybe, if Enya really tried, she could calm down Vladimir Putin, or Donald Trump, or even Guy Fieri. It’s really hard to get het up about things when the dulcet, studio-elongated tones of an Irish chanteuse have lowered your blood pressure to ultra-marathoner levels.

Enya loyalists can rest easy that Dark Sky Island is a distinctly Enyaish album, and that there’s no drastic change in direction or cultural appropriation inspired by her recent move to France. On the song “Echoes in Rain,” she sings the word “Hallelujah” over and over again while a jaunty string section plucks one of two lonely notes in the background. (There’s an odd, seemingly improvised piano solo in the middle that sounds like one of the aforementioned forging angels might have been a jazz fan.) The title track is perhaps the one that will most evoke the glory days of A Day Without Rain and Braveheart. “Come back to me, come back to me,” Enya croons, while what seems to be the opening notes from “Unchained Melody” plays. (To be clear, the opening notes from “Unchained Melody” also feature in another song on the album, “So I Could Find My Way.”)

She’s sold 75 million records by warbling softly over the musical equivalent of someone drumming their knuckles on a coffee table.This is, as should be obvious, music from another era. While listening, you may find yourself thinking of the love affair between Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise in Far and Away, or of the time Harrison Ford helped the Amish build a barn in Witness, or even of the scene in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo where Stellan Skarsgård decides to play “Orinoco Flow” while he’s torturing Daniel Craig to demonstrate the depths of his sadism. But it’s also reassuring in its familiarity. Musicians may grow, and evolve, and take their sound in different directions from time to time; Enya is not one of them. Despite her assurances to The Independent that she feels like her albums are totally different every time, and that she’s broadly influenced by artists including Green Day and P Diddy, her studio is still very much using synthesizers from 1983, and her voice is as fresh and angelic as e’er it was. She’s sold 75 million records by warbling softly over the musical equivalent of someone drumming their knuckles on a coffee table. Why stop now?

In Enya’s defense, this album will undoubtedly give pleasure to millions of people, curled up with their imported sherry and their cashmere hoodies and their dreams of a magical isle seasoned with mist and mellow tunefulness. And, as has been mentioned, Enya is less a musician than a cultural phenomenon, insidiously seeping into therapist’s offices and boutiques and “relaxing” Spotify playlists. She’s been an obvious influence on artists including Imogen Heap, and a less obvious one on Nicki Minaj, who touted Enya as one of the biggest musical inspirations on her album The Pinkprint.

Dark Sky Island might not be as obviously resonant as Shepherd Moons, or Watermark; it arrives, too, in an era that’s probably far too dark and twisty to appreciate her work with any kind of earnest effort. But maybe not. Maybe Enya can soothe a weary, overworked, smartphone-addicted, EDM-exhausted populace with her Latin chants and Gaelic grace. Regardless, she’s back, and as the woman herself would say, hallelujah.

‘Fancy Sweats’ and the Era of Conspicuous Comfort

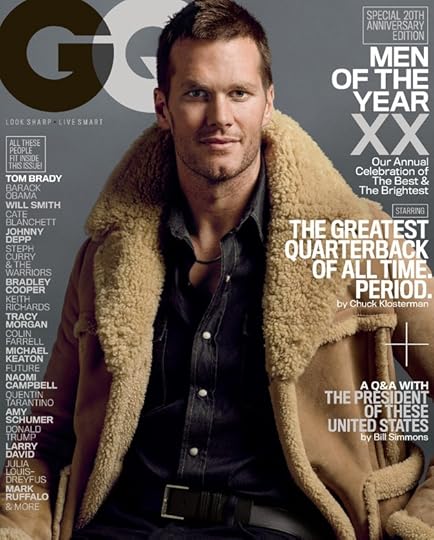

In its naming of Tom Brady as its Man of the Year—yet again, and despite everything—the newest issue of GQ offers a selection of photos of the man it’s dubbed the latest “G.O.A.T.,” or “Greatest of All Time.” The spread, rendered across several pages in the print magazine and as a slideshow of portraits on GQ’s website, features Brady wearing black jeans and a quilted tech vest, frolicking in a meadow; Brady, shot in black and white, lovingly cradling an infant-esque football; Brady in a shearling coat, smiling against a gray backdrop. The photos are both weird and typical in their own unique ways; the most striking of them, though, features Brady clad entirely in a suit of heather gray, splayed come-hitheringly on a couch of muted taupe.

And the most striking thing about that: The suit in question is, effectively, a sweatsuit. Not in the sense of a sweatpants-and-sweatshirt combo, the fruits of lazy looms the nation over, but in the sense of a tailored sports jacket—lapels, sleek pockets, buttons, the whole deal—and not-quite-matching, slim-but-not-too-slim-cut pants. The pants are fabricated in what seems to be thick, soft cotton: Suit in form, sweats in function. And they’re fastened not with a zipper or buttons, but rather tied with a drawstring waistband.

Related Story

Behold, the Short-Sleeved Suit

Firstly: The suit in question looks extremely soft and comfortable, and the fact that Tom Brady gets to wear it in this photo shoot may well be yet another reason to be extremely jealous of him.

Secondly, though: The suit in question is legitimately interesting! GQ is, through one entry in its photographic hagiography, shifting just a little the traditional ideas of what formal luxury is all about. Sweat suits, after all, are the traditional outfits of 1980s-set workouts and 1990s-set episodes of Roseanne, the garb of either extreme comfort or extreme laziness, the thing you wear when you are either working hard or giving up. They are, whatever else you might say about them, all very much not synonymous with historical conceptions of formality, luxury, The Living of One’s Best Life, etc.

However. As worn by the superstar quarterback Tom Brady, as posed in what is ostensibly the opulent mansion he shares with his supermodel wife, GQ’s sweat-suited outfit telegraphs luxury rather than laziness. Which, in the process, telegraphs something else: the new primacy fashion—high fashion, sure, but also fast fashion and all the other forms—has recently given the informal. The whole thing is an outgrowth of what Simon Doonan, a few years ago, dubbed “quiet luxury”: the idea that the one percent, rejecting the thirsty extravagance of the merely rich, have replaced more obvious opulences with subtler forms. The look, Doonan explained, is one of “spare simplicity with foncy labels; it’s a white gold Rolex that resembles a plain old tin Timex; it’s L.L.Bean-style basics with haute-couture prices.”

Fruit of the Loom just released a “professionals collection” designed “to bring the look of success to sweats, without sacrificing comfort.”Today, quiet luxury is, Miranda Priestly-style, filtering into everyday fashion. Its general idea—the foncy, as realized through the basic—is making its way to the world of the normals.

And so: Tom Brady’s fancy-pants sweatpants. Which have become popular not just among NFL quarterbacks, but also among everyday guys. This spring, Business Insider announced that “men are now wearing ‘fancy’ sweatpants to work.” Betabrand sells a pair of “gray dress sweatpants” whose $108 price tag ostensibly accounts for the fact that the products in question offer, Betabrand insists, both “boardroom style” and “bedroom comfort.” This week, Fruit of the Loom released a “professionals collection” featuring formal cuts and casual materials—“the end goal” of this being, the brand explains, “to bring the look of success to sweats, without sacrificing comfort.”

And it’s not just men, of course, who are availing themselves of a new permission to be formal and comfortable at the same time: Women’s fashion lines have been experimenting with their own versions of “fancy sweat pants.” Which include both traditional sweat-pant designs and also their cousins, the track pants—and which tend to be fabricated in silks and microfibers and cashmeres and other quietly luxurious materials, the better to conflate comfort and confidence.

GQ

GQ Those small shifts—bringing some slack to the world of slacks—are all, in turn, a reflection of bigger changes. They come from a culture that reveres the be-hoodied men-children of Silicon Valley, that prizes informality in language and social interaction, that can treat “work” as a dirty word. A culture in which yoga pants have become status symbols. The fancy-ish sweat suit—a yin and yang of the formal and the fun—is the optimal outfit for a time that is replacing an ethos of “conspicuous consumption” with one of “conspicuous comfort.” It is rejecting the longstanding assumption that formality must come with a degree of discomfort (see: corsets and girdles and high heels, top hats and belts and neckties). It recognizes that suits, in particular, are uncomfortable and impractical and generally pretty terrible, and that people have worn them, for the most part, because they have been what people have worn.

Brady’s sweat suit, in its softly heathered way, pushes back against that tautology. And so do its fellow outfits. Together they insist on something humans have long known, but that fashion has been slower to catch on to: that the biggest luxury of all is the ability to be comfortable.

Hillary Clinton: 'Smash the Would-Be Caliphate'

On Thursday, Hillary Clinton joined the Council on Foreign Relations to deliver her plan to battle ISIS in the wake of last week’s Paris attacks.

The violence in France seemed to stunt momentum that she’d regained ahead of the second Democratic debate on Saturday. As we noted, following Friday’s attacks, Clinton faced tough questions about foreign policy at that debate and about her record on issues that set her to the right of her party.

As my colleague David Graham argued earlier today, the Democratic presidential candidates have generally been loath to take the focus off of domestic issues, where the party’s standing is currently strong. Republicans, on the other hand, have been trying to do the opposite.

Providing a detailed strategy to battle the Islamic State presented a number of potential pitfalls for Clinton, who aimed to seem more hawkish than the president under whom she served as secretary of state, but not so critical as to alienate her base or remind voters of her support for the use of force against Iraq in 2002.

And so, in Thursday’s speech, Clinton held President Obama’s anti-ISIS blueprint close, but not too close; she argued for more American involvement, but also more international involvement.

What we have done with airstrikes has made a difference but now it needs to make a greater difference and we need more of a coalition flying those missions with us.

She also argued for more ground troops, but not American ground troops. More American special ops forces, however, were another thing:

To support them, we should immediately deploy the special operations force President Obama has already authorized, and be prepared to deploy more as more Syrians get into the fight.

A question posed right after the speech perfectly crystallized the dilemma facing Clinton. She was asked whether her plan was an intensification of President Obama’s ISIS strategy or a different one entirely. The answer, it turns out, is both.

Well, as I said in the speech, it is, in many ways, an intensification, an acceleration of the strategy. But it has to also intensify and accelerate our efforts in the other arenas.

Clinton called for more firepower from the air and called on Silicon Valley and the private sector to help disrupt terrorist communications, but not at the expense of privacy. She added that arming the Kurds and some Sunni forces in Iraq would be necessary. When given a chance to take a shot at President Obama’s now infamous “ISIS is the J.V. team” remark, she passed, but still sought to distinguish herself as a proponent of arming Syrian moderates during the early days of the civil war when she was the secretary of state.

But even when I was still there, which is publicly known, I thought we needed to do more earlier to try to identify indigenous Syrian fighters, so-called “moderates”—and I do think there were some early on—that we could have done more to help them in their fight against Assad.

For listeners on the left, Clinton stressed her opposition to limit the flow of refugees into the United States. “This is no time to be scoring political points,” she said, taking a shot at Republican candidates. “We must use every pillar of American power, including our values, to fight terror.”

Turning away orphans, applying a religious test, discriminating against Muslims, slamming the door on every Syrian refugee—that is just not who we are. We are better than that.

And remember, many of these refugees are fleeing the same terrorists who threaten us. It would be a cruel irony indeed if ISIS can force families from their homes and then also prevent them from ever finding new ones.

And still yet, Clinton touted her bipartisan bona fides, using the Manhattan venue for her speech to remind everyone that she had also been in power during America’s worst encounter with terrorism.

“When New York was attacked on 9/11, we had a Republican president, a Republican governor and a Republican mayor, and I worked with all of them,” she said. “We pulled together and put partisanship aside to rebuild our city and protect our country.”

Bernie Sanders's Long-Lost Hope of Establishing a Maximum Wage

All three Democratic candidates favor raising the minimum wage up to somewhere between $12 and $15 an hour. But forget, for a moment, the minimum wage—what about establishing a maximum wage?

It’s a question that no candidate is asking at the moment, but it’s one Bernie Sanders used to be preoccupied with, starting in the 1970s. Back then, during one of Sanders’s early Senate campaigns, one local Vermont newspaper wrote that he wanted to “make it illegal to amass more wealth than a human family could use in a lifetime.” Sanders was apparently still batting the idea around until at least the early ‘90s, when he submitted a Los Angeles Times op-ed by the journalist Sam Pizzigati titled “How About a Maximum Wage?” to the congressional record. (The Sanders campaign has been contacted for comment but has not yet replied.)

Here’s how it’d work: Right now, any dollar an American earns beyond a certain amount (about $450,000) is taxed at 39.6 percent. This is America’s top marginal tax rate, and lower marginal tax rates are applied to money earned under other lower thresholds. Sanders’s one-time plan for a maximum wage was simple: Set a threshold above which the marginal tax rate is 100 percent, so that every dollar earned beyond it would go straight to the government.

Sanders has since scaled back his vision. He hasn’t revealed the specifics of his tax plan, but he’s said that his proposed top marginal tax rate will be somewhere between 50 and 90 percent. (Ninety percent, as Sanders has pointed out, is about what the top marginal tax rate was during the tenure of Dwight Eisenhower.) Today, a top marginal tax rate of 100 percent is such a radical proposition that there hasn’t been much academic writing about it (though a British economist supported the idea in a paper 10 years ago).

Decades ago, the notion of a maximum income had much more mainstream support, even if it never really stood a chance of becoming law. In the ‘40s, Franklin Delano Roosevelt recommended instating a maximum income, prompting one famous actress to say publicly, “I regret that I have only one salary to give to my country.” Congress, however, was less enthralled, and it declined to approve Roosevelt’s proposed cap on net income at $25,000, or about $365,000 in today’s dollars.

Sanders, of course, said and wrote many things several decades ago that he doesn’t believe now. One of his pieces published in alternative Vermont newspapers in the ‘70s, as noted by Mother Jones earlier this year, suggested that it isn’t all that unnatural for humans to eat the placenta in a ritual after birth. Other essays he wrote around that time drew attention to the (completely bunk) correlation between “the manner in which you bring up your daughter with regard to sexual attitudes” and “whether or not she will develop breast cancer.”

But while the specifics of Sanders’s economic message may have changed over the years, he has remained true to certain core values. A 1974 newspaper article reporting on his political platform was headlined “Concentrated Wealth is Causing Economic Illness,” a phrase that would not be surprising to hear from Sanders at a debate these days. As Paul Heintz, the political editor of Vermont’s Seven Days recently told the podcast On the Media, “He has been making the same point for 40 years.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower