Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 268

December 22, 2015

No Indictment in the Death of Sandra Bland

A grand jury on Monday decided not to indict anyone in connection with the death of a Chicago woman who was found dead in an apparent suicide in her jail cell three days after she was arrested during a routine traffic stop this summer in Texas.

The Texas jury had considered the death of Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old black woman, and the conduct of the staff at the Waller County jail where she was held, and not other parts of the case, such as the role of Brian Encinia, the white Texas state trooper who pulled Bland over, said prosecutor Darrell Jordan.

Jordan said jurors would reconvene in January to consider other aspects of the case, which may include actions taken by Encinia, who Texas public safety officials say violated policies of professionalism and courtesy in his encounter with Bland. Encinia has been on administrative duty since her death in July.

On July 10, Bland was driving from Illinois to her alma mater, Prairie View A&M University, where she had gotten a new job, when she was pulled over by a state trooper for failing to use a turn signal in Prairie View, northwest of Houston. The encounter, which was filmed by Encinia’s dashboard camera, quickly escalated. The driver and officer exchange heated words, and Encinia eventually threatened to use a stun again against Bland—“I will light you up!”—dragged her out of the car, and arrested her. Bland was taken to Waller County jail, where she was found hanged with a plastic trash bag from a metal barrier in her cell. Medical examiners ruled her death a suicide.

Bland’s family disputed the account that she killed herself. As my colleague David Graham wrote in July:

Almost as soon as Bland died, her family and many black Americans assumed the worst. They were skeptical of official explanations and pessimistic about the odds of a thorough and fair investigation. A popular hashtag, #IfIDieInCustody, became a forum to express that skepticism and the fear of being disappeared into a jail—or, like Freddie Gray, a police wagon—and emerging dead or near death, with no explanation and little evidence to explain what happened beyond the official account.

Cannon Lambert, a lawyer for the Bland family, called the grand jury proceedings a “sham of a process,” and that family members first learned there was no indictment through news reports.

“We would like very much to know what in the heck they’re doing, who they’re targeting and if it has anything to do with Sandy and her circumstances,” Lambert told The New York Times Monday night.

The Bland family in August filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against Encinia and two guards at the Waller County jail; the trial is scheduled for January 2017.

Hollywood's Spotty Record on Improving Racial Diversity in 2015

This year, multi-cultural representations hit a high on television while the silver screen struggled to keep up: Viola Davis became the first black woman to win a Best Actress in a Drama Emmy in the same year that The Hollywood Reporter declared “there are no minority actresses in genuine contention for an Oscar this year.”

Performers like Nicki Minaj, Wyatt Cenac, and Aziz Ansari challenged the entertainment industry’s bias, highlighting their personal experiences with racism. Three comedies featuring families of color, Black-ish, Fresh Off the Boat, and Jane the Virgin, bested expectations and demonstrated audiences’ appetite for diverse entertainment.

Yet as television championed pluralistic programming, films like Stonewall seemingly retreated, re-imagining a multi-ethnic history as all-white. This, unfortunately, is part of a pervasive trend in film-making: A new study by the University of Southern California analyzing the top 100 films of 2014 showed that almost 75 percent of movie characters were white.

How to Write: A Year in Advice From ‘By Heart’

This year, nearly 30 writers shared their favorite passages from literature for “By Heart,” The Atlantic’s series about books, literary influence, and the creative process. If the series has any single theme, it’s that reading has the power to change our minds and transform the way we see things. Each writer tends to tell me a variation on the same story: I read something, and I wasn’t quite the same afterwards. But what was read, what kind of change took place—that part is different every time.

The series is full of writing advice, too—but it’s not “advice” in the typical sense. Most of the people I talk to seem to feel that writing is an idiosyncratic and highly personal process; when they talk craft, they aren’t dispensing one-size-fits-all pointers. They’re usually recounting challenges that are specific to an individual, even to a particular work. Tania James, for instance, couldn’t find the right voice for her narrator, a South Indian elephant poacher; Kevin Barry wanted to pull off a novel written from John Lennon’s perspective.

I think that’s the best kind of advice, actually. No one wants to be told what to do. Instead, we want to see our own (creative) challenges—also individual, also particular—reflected in someone else’s struggles. Sometimes, that second-hand knowledge can help us make better, smarter decisions. Not every insight in this series will help every writer, but every insight has the potential to save some writer, somewhere, some heartache.

Even if every story, essay, poem, has to find its own way, there are still some universal challenges. I think that’s why so many common themes emerged from this year’s conversations, even from a very diverse group of writers reading different books on their own terms. As a group, “By Heart” contributors spoke about the importance of humor, the anxiety of creating fake people, the quest for a proper ending, and much more. Here are the best pieces of writing advice they offered this year.

Sound and (non)sense, ditching grammar and reading out loud

The first writer I spoke to this year was the Harvard cognitive scientist Steven Pinker (whose 2014 book The Sense of Style is a must for any 21st-century wordsmith). Because it was a big-picture conversation—about Shakespeare, human ignorance, and our capacity for moral atrocity—I cut a worthwhile section where Pinker talked about grammar from the original interview. His advice? Ignore the (grammar) police. They usually don’t know what they’re talking about:

Many of the language tenets that the purists and the snobs and the sticklers criticize are in fact perfectly logical according to the grammar of English. One example being so-called “singular they,” as in: everyone return to their seats. A number of the purists would claim this has a grammatical error: namely, the clash of concord between the plural pronoun “they” and the singular antecedent “everyone.” But in fact it would be that the purists that are wrong and error-makers are right—because singular “they” has a long history in English, including Shakespeare and Jane Austen. And if, in fact, you analyze the semantics of it, it is not at all illogical, because “they” in that context is not in fact a plural pronoun but rather a bound variable.

Jesse Ball, author of A Cure for Suicide, argued that you can get away with almost anything if it sounds good—and not just bad grammar. He pointed to Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” as proof that sound matters more than sense. That’s why Ball writes and revises by reading his work out loud:

When I really get going, I’m murmuring what I’m writing in a half-breath as I’m working. It’s probably embarrassing if I’m in some public place, sitting there ranting to myself. (Usually I try to sit far enough away from other people.) They say that after you write a work, and finally look at it, you can’t tell what’s there any more.

How can you actually see the work in order to judge it? One way is to read it out loud—to somebody who you’re a little afraid of, whose opinion matters to you. When you read it aloud, there are parts you might skip over—you find yourself not wanting to speak them. Those are the weak parts. It’s hard to find them otherwise, just reading along. But you can judge the work more clearly when you hear and feel its sound.

Kevin Barry, the author of Beatlebone, said something similar, arguing that—in our bleary-eyed 21st-century—sound is more important than ever. Barry feels we want to be mesmerized by the human voice, so he writes for the ear, not the eye:

My ear is my critical tool as a writer, because it’s what catches the false notes. Your eye can very easily glide across the page, look down at the text and go, “Oh yeah, that’s fine.” But if you read it out and hear it, your ear will very quickly tell you when you’re not quite there.

Writing for the ear is kind of like being an actor: I approach my characters as though I'm approaching roles to play out. Acting out the work, doing all the voices, and reciting it aloud is a very important part of the process for me. I write a lot of dialogue in my stories and novels. Duologues and monologues tend to be the engines of my projects, and I will rewrite the fuckers endlessly. I will do 100 drafts of a dialogue. I’ll constantly take the red pen to it as I act it out, trying to get closer and closer.

If you read through a dialogue twice and it seems fine, that’s something. If you read through it 10 times and it seems okay, that means something. But it’s when you go through it 100 times, and you stop making marks in it, that you know you have it right.

Getting down to business

For many writers, the hardest part is getting started. Several of the people I spoke to this year shared tricks for overcoming inertia and anxiety—techniques that seem to help them get words on the page. Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, found a novel with a narrative feel he wanted to emulate. As he read a bit each morning, it worked like good espresso:

The language itself had some kind of impact on me that was more emotional than intellectual. The book acted as a condensed, compact, extremely powerful substance that woke me up to what I needed to do, each day, as a writer. I thought of it as espresso. It wasn’t coffee—I couldn’t drink it all day long. I could only take small doses, and that was enough. With caffeine, how do you quantify what’s happening with that? You just know you need it. The process was mysterious, and it worked.

For years, Mary-Beth Hughes, author of The Loved Ones, studied dance at Merce Cunningham’s famed Manhattan studio. The experience taught her about discipline, patience, and the importance of showing up—and writing, as she describes it, means working through (and waiting out) the dry spells. Just make the time, even if it means sitting there, she says. Good things, eventually, will come:

I think daily practice is helpful as much as possible, and it’s not always possible. Writing is hard to pick up and put down, and it’s easier when it’s a routine…Because I spent so many years as a dancer, I understand in every part of me how slow it all is. The zillion hours dancers put in so that they can do three steps across the floor.

Patience. Curiosity. Repetition. Looking again and again. Not imposing a story line. Letting composition emerge through pattern, rhythm, shape, sound, movement. Occasionally … you hit upon a moment of grace. You can’t plan for it. You just have to practice enough so that you’re ready when it comes.

Karl Ove Knausgaard, author of the My Struggle series, described writing “naively”—a kind of writing without thinking that’s helped him generate pages and pages. His daily compositional process requires only two things: a limiting constraint or theme, and a resolve not to analyze or evaluate what he’s writing as he works:

Every morning now, I write one page. I get up early and write one page in two hours. I start with a word. It could be “apple” or “sun” or “tooth,” anything—it doesn’t matter. It’s just a starting point—a word, an association—and the restriction that I write about that. It can’t be about anything else. Then I just start, without knowing what it’s going to be about. And it’s like the text produces itself.

I’m not talking about quality. For god’s sake, no. It’s not like this text ever looks good or anything. It’s just sitting there writing. Not thinking, and writing.

When you are not aware of yourself, you start to write things you have never thought about before. Your thoughts do not take the path they would normally have followed, and the thinking is different from your own. The language is in you, but it’s out of you, and it doesn’t belong to you. That’s what literature can do—when you throw something in, something else comes back.

If you have faith in your writing, it’s easy. It’s when you remove that faith that things become difficult—when you start to think, this is stupid, this is idiotic, this is worthless, and so on. That’s the real fight: to overcome those kinds of thoughts.

“It provides a mask”: writing across borders

My conversation with Lorin Stein was about the current state of American short fiction, an outline of the overarching qualities he’s noticed as editor of The Paris Review. Stein suggested that today’s literature—in an age when anyone can broadcast their thoughts and ideas using a range of amplifying platforms—has power because it frees writers to adopt voices and perspectives that aren’t their own.

When it’s done right, fiction provides the authority to speak about deep things; at the same time, it provides a shield, a mask. The mask lets you say things, talk about things, that you couldn’t ordinarily talk about.

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to speak as someone else. Several writers expressed anxiety about representing other people, especially the challenge of making unfamiliar characters real. Angela Flournoy—who was named a National Book Award Foundation “5 under 35” writer shortly after we spoke—wasn’t sure she had license to write about Detroit, a complex city she has never lived in. Writing The Turner House taught her that no topic is off-limits, as long as you’re able to imbue characters with full human complexity:

It’s when you’ve somehow failed to make fully nuanced and three-dimensional characters that people start to say, what right do you have? But when the characters transcend type, no one questions the author’s motives. Characters’ backgrounds, their gender—these things are only aspects of their personality, just as they are for real people. If the writer pulls it off, if they make you see the humanity in the character, that stuff falls away—no matter who you’re writing about.

At a certain point, you have to be kind to yourself as a writer and trust your own motives. You have to have confidence that you’re coming from the right place. You have to allow yourself to let loose, pursue a good story, and create people who feel real. Not good, not bad, certainly not perfect—just real.

Easier said than done, of course—as Tania James can attest. As she wrote The Tusk That Did the Damage, she found her narrator, a Malaysian elephant poacher, to be flat and unconvincing. Then Peter Carey’s novel The Kelly Gang reminded her to loosen up:

Reading The Kelly Gang gave me the permission to be looser, more playful with the poacher’s voice, in spite of his grim circumstances. And Carey reminded me that when characters speak with the irreverence that comes naturally to them, they’re brought into sharper relief.

In order to move beyond my preconceived notions about a certain character type, I realized I needed to focus on what brought that individual person’s voice to life. I stopped asking the question, “What would a poacher be like?” and started thinking about language, especially its capacity for humor and playfulness.

From the beginning, my would-be poacher spoke from a place of conviction and passion and anger, but it wasn’t until I accessed these emotions with a bit of irony and sarcasm that he really came alive for me. Once I introduced that wry humor, he started to feel more like an extension of my personality. That’s when I lost the flat feeling I started with. In the beginning, my sentences were less messy, more lyrical, smoother. But until I relaxed and loosened up, the writing didn’t feel inhabited by a real, feeling person.

It’s a reminder that making a characters or a scenario seem “real” doesn’t necessarily mean being “realistic.” In fact, a book’s most authentic-seeming qualities are often the most invented—and the things that are “realistic,” or plucked straight from life, can strike false notes. Mary Gaitskill, author of The Mare, pointed out this paradox:

In fiction, the things that are realistic or literally true don’t always feel true. It happens in my writing classes over and over and again: the thing that everyone, including me, picks out as unbelievable sometimes is exactly the thing the writer will say, “But it really happened!” And it probably did. But it means they haven’t done enough to make that incident enter the world of the story, which becomes a reality with its own logic. When something genuinely surprising happens in a work of fiction, you have to be very in the story, and very in the moment, to make the reader accept it.

What’s funny? “Find the victim”

What makes humor successful? The graphic novelist Scott McCloud’s “By Heart” post was a treatise on that topic. He described what the comics artist Art Spiegelman taught him about getting laughs, and balancing darkness with light.

“Most humor is a refined form of aggression and hatred,” Spiegelman writes. “Our savage ancestors laughed with uninhibited relish at cripples, paralytics, amputees, midgets, monsters, the deaf, the poor and the crazy.” I’ve taken this idea as a jumping-off point in my own work. Whenever I’m considering why something’s funny or not, I always tell myself: find the victim. Humor is targeted. It may be aimed at an individual, at an institution, or the entire superstructure of rational thinking. But something is always being skewered.

As I wrote The Sculptor, my latest graphic novel, I wanted to balance darkness with levity. In any story, I think the more serious themes benefit from the inclusion of humor. (Shakespeare’s high-minded but irreverent plays are one timeless example.) Humor inoculates a work from being overly solemn and overly self-important. And moments of dramatic magnitude can be bolstered by the inclusion of the ridiculous, or the intimate, or the smallest of human moments.

Productive ambiguity: redacting more than you add

Lorin Stein told me that the contemporary American short story is characterized by a kind of willful ambiguity, a quality he says is especially present in the ending of Denis Johnson’s “Car Crash While Hitchhiking.” For Reif Larsen, author of I Am Radar, good stories withhold more than than they disclose:

One thing I think is true about successful storytelling: There’s as much significance in what’s left out as in what’s actually said. Of course, our initial impulse is to want to give lots and lots of context. Here we are at this location. Here’s how we got here. Here’s what it looks like, and so on. That tends to be the easy stuff. The hard part is non-disclosure. This is really a crucial tenet of narration, perhaps the crucial tenet—and it’s not an innate skill. How do we learn how not to tell things?

We all have this tendency to want to tie up the loose ends. Our brains just sort of fill in gaps and holes automatically, and as a writer it’s tempting to try to do that for the reader—I have to come out and say this or that, we fear, or people won’t “get it.” With my new book, I wanted to resist that impulse. Instead of closing loops, I tried to leave them open. My hope is that this openness is emotionally compelling, but who knows? In this day and age, it’s challenging—particularly as our attention spans collapse—to be comfortable with long-form ambiguity. It can anger people if you take it too far. And yet I think all my favorite books linger with me because they don’t close the loops. If a story’s ending closes out too many possibilities, you risk damaging the potential connections and openings the reader can make. That openness can be a gift.

Fitting endings

T.C. Boyle, author of The Harder They Come, echoed Larsen’s sentiments, reminding us that every work of literature has to find its own way: An approach that succeeds in one piece can fall flat in another. Boyle said that, for him, that’s the pleasure of writing: remaining open to possibilities, trying things, and—every now and then—stumbling on something that ties it all together.

I think the best endings bring you back in, rather than close things off with absolute finality. I’m not saying they necessarily have to be ambiguous, but we don’t always need to know what happens when everyone wakes up tomorrow morning … When I start a story, I don’t know what the ending will be in advance. I very much believe in working organically—that is, I don’t know what the story will be or what’s going to happen.

This is the beauty of the art of fiction, as opposed to laying out an essay or writing a thriller. You remain open to the possibilities throughout the entire story. When they’re lucky, the artist finds one line, one moment that brings it all together. It’s hard to say how certain stories just punch us in the heart and the brain at the same time at the end. I suppose that’s what we’re all looking for.

'Once in Royal David's City': A Staid Victorian Sermon

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

Many Christmas carols can seem Victorian, but few assault the listener with all the extravagant Victorian-ness of Once in Royal David’s City. The carol easily dispatches all the standard duties of the genre—it sets the Nativity scene, summarizes Church teaching, alludes to the Second Coming—and then it moves right into 19th-century accessorizing.

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

Once in Royal David’s City see-saws along with a sing-song-ish sort of melody. It embraces English-language grammatical tics that really only make sense in Latin. And it includes an entire verse that chides parents about how to correctly raise children.

The point is, if you’ve never seen it in action, then Once in Royal David’s City isn’t an easy hymn to admire. It’s a hymn, for one thing, so it prattles on, samey strophe after samey strophe, even after the congregation has gotten bored. Pop musicians don’t seem to know what to do with it, so they’ve turned Once into The Friendly Beasts Lite, without the best part of The Friendly Beasts, which are the arguing beasts.* Even famed liturgy hipster Sufjan Stevens, redeemer of tough carols, gets kinda jaunty in his cover of Royal David.

Once in Royal David’s City yet shines, though. And it does so because, in the world of church music, it has a use so well-loved and well-understood as to be ritualistic.

Every year, the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, opens their Festival of Lessons and Carols with Once in Royal David’s City. For the uninitiated, a Festival of Lessons and Carols is the standard Christmas music service: There are nine short Bible readings, from Genesis to Revelation, but mostly there’s music. And the relationship between the King’s College festival, and every other English-language Lessons and Carols in the world, is analogous to that between the iPhone and every other smartphone.

When King’s College introduces Once in Royal David’s City, it does it by a very specific method: A solo boy soprano chorister sings the first verse, a capella. Then the choir, also a capella, joins on the second verse as choristers process through the middle of the aisle and file into their rows. Until at last, on verses three through five, the organ and the whole Cantabrigian congregation—the arch dons, the gruff dads, the doting mums—join in.

Here’s an older video of it, with a kind of gradually increasing VHS-ized distortion that gives the impression of 30 innocent boys being eaten by a theremin. You’ll notice that the production choices, made at these two different televised performances at least a decade apart, are otherwise identical. Such is the talismanic, reliable power of the King’s College festival. They’ve been opening the service this way for 96 years.

Once in Royal David’s City, as a standalone work, began as a poem by Cecil Frances Humphreys. Better known as C.F. Alexander, she was an Irish Anglican who contributed text after text to English-language hymnody. But in the 1840s, when she wrote Once, she was a well-educated and well-connected woman in her late twenties.

As she told it, Once started as an effort to explain the Apostle’s Creed to a perplexed child. She spun each line of the statement into its own poem. The first line became All Things Bright and Beautiful, eventually its own liturgical blockbuster. The second and third line of the creed—“who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, / born of the Virgin Mary”—became Once in Royal David’s City.

Those hymns and others were published as Hymns for Little Children in 1848. The next year, the English organist Henry John Gauntlett set Once to his tune Irby. The year after that, Humphreys would marry William Alexander. By the end of the 19th century, William was the Anglican Primate of Ireland, and Hymns for Little Children was in its 69th edition.

Let us return again to its Victorian-ness. This was a hymn written to instruct kids in the tenets of faith. Nowhere is that goal sillier than its third verse:

And through all his wondrous childhood

He would honour and obey,

Love and watch the lowly maiden

In whose gentle arms he lay;

Christian children all must be

Mild, obedient, good as he.

“Mild, obedient, good”: Forget about Jesus Christ, Superstar. At least according to Cecil Frances, the living God wasn’t even a free-range kid.

So here is the puzzle of Once in Royal David’s City. When you look at the text, it can seem antiquated. When you listen to the music, it can seem inadequate. So why does the carol still work?

I think because of that sense of dignity. As the hymn proceeds into its conclusion—a standard Christian contrast between the meek infant and the King of Kings—it maintains its sense. There is awe here, and deep religious fortitude, and even stately theatrics, but about all of this it is distinguished and somber. It is a fine mood with which to start a service, and a fine mood to ponder in the late gray light of winter.

'Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas': An Ode to Seasonal Melancholy

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

“There’s no place like home” is a quote from a very different Judy Garland movie, but it encapsulates the spirit of Meet Me in St. Louis just as well. In the 1944 musical, Garland’s character, Esther, is the second-oldest daughter to the Smith family, living happily in St. Louis until her father is called to relocate to New York for work. On Christmas Eve, Esther comes home from a holiday ball to find her younger sister worrying Santa won’t be able to find them after the move.

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

Meet Me in St. Louis was set in 1903, but the song “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” was written in 1943 by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane before filming began, during World War Two. Martin’s original lyrics, he told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2006, were deemed too sad, so he was obliged to rewrite them. The first set went:

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

It may be your last

Next year we may all be living in the past

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

Pop that champagne cork

Next year we may all be living in New York

After Garland protested that it would be unnecessarily cruel to sing these lines to a brokenhearted younger sister, Martin wrote the lines she sang in the film:

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

Let your heart be light

Next year all our troubles will be out of sight

Have yourself a merry little Christmas

Make the yuletide gay

Next year all our troubles will be miles away

It’s a cheerier perspective, for sure, but there’s still a lingering sense of melancholy, which manifests in the film when Esther’s sister responds to the song by running outside in her nightgown and smashing up all the snow-people she’s crafted in the front yard. The song also held special resonance for American soldiers fighting in Europe when the movie came out, and Garland sang it live at the Hollywood Canteen, a club for servicemen on their way overseas.

There’s a particular sadness in the lines Garland sings at the end of the song, implying both loss and the wartime obligation to endure:

Some day soon we all will be together

If the fates allow

Until then we’ll have to muddle through somehow

In 1957, Frank Sinatra asked Martin to write a cheerier update for the song, which prompted the new line, “Hang a shining star upon the highest bough.” And it’s this version that performers typically use now, from Bette Midler to Babyface to Sam Smith. As much as Garland’s version will always be the definitive one, the song has prompted a number of moving interpretations. One of my favorites is by James Taylor, using the original lyrics, because it captures the bittersweet nostalgia and homesickness so many people feel around this time of year.

Barack Obama Blames the Messenger

For a guy who rose to the presidency in large part by relying on his abilities as a communicator, Barack Obama seems to have little regard for messaging. The president evinces a view of public relations as a distasteful business—one that is necessary, he grudgingly acknowledges, but also an essentially cosmetic, irrelevant one.

During an interview with NPR’s Steve Inskeep, Obama again tried to reassure citizens that ISIS is not an existential threat to the United States. “They can hurt us, and they can hurt our people and our families,” he said. “The most damage they can do, though, is if they start changing how we live and what our values are.”

Related Story

The Wrong Side of 'the Right Side of History'

He said one reason for the problem is his own communication. “Now on our side, I think that there is a legitimate criticism of what I've been doing and our administration has been doing in the sense that we haven't, you know, on a regular basis I think described all the work that we've been doing for more than a year now to defeat ISIL,” Obama said. Meanwhile, he blamed “the media” for “pursuing ratings.”

The president also said during an off-the-record conversation with columnists last week that his Oval Office address hadn't gone far enough, a shortcoming he attributed to his own failure to watch enough cable news to understand the depth of anxiety.

In other words, the strategy is working, and the White House just needs to communicate that better. The fights against domestic terror and ISIS alike are going great, if only people would understand it. But Obama’s impatience with the media and messaging is also clear. In some ways he may be right about the strategy. Despite the carnage in San Bernardino (and in Paris), ISIS is losing territory. That may be a long way from defeating them, but things are moving in the right direction. (Obama noted with some satisfaction that “those who are critics of our administration response, or the military, the intelligence response that we are currently mounting—when you ask them, well, what would you do instead, they don't have an answer.”)

This is humblebrag politics: I’m not great at explaining it, but man, am I great at policy. But does it accurately understand the problems, or what messaging entails? Obama views battlefield success against ISIS as the goal, and messaging as a simple process of telegraphing that. Messaging can be something greater than just the wrapping paper on the policy solution he has chosen. It’s about persuading people to come around to your side, not just telling them why your side is right.

This isn’t the first time Obama has insisted that everything’s going great and it’s just the wrapping paper that needs sprucing up. After the 2014 midterm election, which saw defeats for Democrats on all fronts, Obama told Bob Schieffer the problem was that he hadn’t communicated how well his administration was doing:

One thing that I do need to constantly remind myself and my team are is it's not enough just to build the better mousetrap. People don't automatically come beating to your door. We've got to sell it, we've got to reach out to the other side and where possible persuade. And I think there are times, there's no doubt about it where, you know, I think we have not been successful in going out there and letting people know what it is that we are trying to do and why this is the right direction. So there is a failure of politics there that we have got to improve on.

After the 2010 midterm “shellacking,” Obama was somewhat more conciliatory, saying, “I think that what I think is absolutely true is voters are not satisfied with the outcomes.” But even then, he wasn’t saying Republicans were right to oppose his stimulus; he was saying he hadn’t enacted an aggressive enough approach to create enough jobs. He wasn’t saying the price tags for the stimulus were too large; he was saying they seemed too large to many people.

In fact, many economists agree that he should have pursued a larger stimulus. There is widespread support for many components of the Affordable Care Act taken singly, despite the many more people who oppose the law in total. But it’s likely that many people would have opposed these efforts anyway. Some would have done so out of partisan, tribal loyalty, which motivates many people’s political positions. Others would have done so out of essential opposition to big-government programs. (Obama actually got at this, saying, “I think people started looking at all this and it felt as if government was getting much more intrusive into people’s lives than they were accustomed to”—though that “accustomed to” seems to again presume that with enough time and the right wrapping, they could be convinced.)

Many Democrats have long thought that white, blue-collar voters, who have gradually deserted the party since Ronald Reagan was running for president, were just waiting for the right approach to lure them back. Democrats look at them as clear allies who are voting against their own interest, if only they could be made to see that. Obama touched on that idea in his Inskeep interview, too:

But I do think that when you combine that demographic change with all the economic stresses that people have been going through because of the financial crisis, because of technology, because of globalization, the fact that wages and incomes have been flatlining for some time, and that particularly blue-collar men have had a lot of trouble in this new economy, where they are no longer getting the same bargain that they got when they were going to a factory and able to support their families on a single paycheck, you combine those things and it means that there is going to be potential anger, frustration, fear. Some of it justified but just misdirected. I think somebody like Mr. Trump is taking advantage of that. That's what he's exploiting during the course of his campaign.

This is really just a more delicate articulation of Obama’s infamous comments in 2008 about voters who “get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.” (Inskeep, in fact, mentioned those comments later in the interview.) And it’s not unlike Tom Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas? thesis, about citizens voting against what liberals see as their own self-interest.

Many of the disagreements here are about more than messaging. Perhaps those white, working-class voters aren’t getting what they want out of the Democratic Party. (Group identity, rather than policy ignorance, probably goes a long way to explaining the discrepancy.) Maybe people wouldn’t be radically more supportive of Obama’s domestic-policy agenda if they just understood it better. The fact that no one else has a better idea for combating ISIS may indicate the magnitude of the challenge, not vindication for Obama. Explaining to voters why you're right often requires first taking seriously why they think you're wrong, and adapting underlying policies to address their concerns. Someone should figure out how to message that to the president.

December 21, 2015

The Best Food Books of 2015

Adventure: it’s what the writers of this year’s food books want you to have, mostly in your own kitchen. And it’s mostly guys in kitchens—guys who aren’t afraid of moving beyond the chef-bro attitude and revealing feelings beneath the tattoos, along with a more familiar competitive streak they generously aim toward broadening your own geographic and technical range.

If not the book of our generation, as Harold McGee's On Food and Cooking was and is, J. Kenji Lopez-Alt's Food Lab: Better Cooking Through Science is essential for anyone who wants to understand the whys of cooking, and has a little bit of showoff science-nerd—as pretty much every serious cook does. Lopez-Alt, an MIT graduate, developed a following as the obsessively experimenting resident researcher at SeriousEats.com, and this nearly thousand-page collects his findings on most every dish you’re likely to try (except desserts, because he doesn’t like them). He's the kid who’ll never take your word for it: asparagus spears will break off just at the point they get woody (they break off pretty much anyplace you apply pressure, as a harmonica-like arrangement of broken spears shows), you should salt steak a half hour before you sear it (either right before or the night before, in essence), never ever press down on a burger. And he’ll make many, many versions and show you the pictures to prove it.

None of it feels show-offy, though: Lopez-Alt brims with enthusiasm, and can't wait to tell you just how to avoid those floating trails of egg white in poached eggs (if I tell you the answer, an incredibly simple trick he learned from the English science-minded chef Heston Blumenthal, I'll spoil a major reason to buy the book). Or how to reverse-engineer mac and cheese and make yes, great burgers—two questions that seem to burn for every scientist-chef (they took up important real estate for the Modernist Cuisine team led by Nathan Myhrvold). Even know-it-all readers will learn something every couple of pages, like why green vegetables lose their color when boiled (the water becomes acidic and bleaches them out), and the fact that a Maillard reaction isn’t synonymous with caramelization (it comes from browning not just sugars but sugars and protein).

The equipment he uses is blessedly standard, as in the poached-egg trick; his sous-vide section is short and breezy, thank goodness. He's as opinionated as he is engaging, and you're likely to agree with him or take his word for it: In a comprehensive section on steak cuts, “skirt is probably the greatest dollar-to-flavor value there is.” This is the ideal gift for a high-school student who's interested in cooking. But it will make anyone a better and more informed cook—and someone likelier to have more confidence, and more fun, in the kitchen.

You can tell just how nice Michael Anthony, the executive chef of Gramercy Tavern and the new New York City restaurant Untitled, is on every friendly page of V is for Vegetables: Inspired Recipes & Techniques for Home Cooks from Artichokes to Zucchini. (He can't help it, he's from Ohio.) What makes his new book (written with Dorothy Kalins, the founding editor of the US edition of Saveur) so appealing are his simple and right instincts that will make you want to try vegetables you might not ordinarily be tempted by, like salsify and rutabaga. He's not above iceberg lettuce, which he grills with marinated tomatoes, and he finds small twists you want to try right off: toasted walnuts and walnut oil with mashed potatoes; honey and black pepper with braised radishes; simple syrup and dijon mustard to a warm salad of snow peas, cherries, and baby chard.

When he takes on a classic, like onion soup, you know it will work: His recipes have the easy confidence and trustworthiness that make Ina Garten perennially reliable. Though by no means strictly vegetarian (beef in the onion soup, or Korean hot pots, bacon in an onion tart) the majority of recipes casually are. The quotations on opening pages (the oversized picture book is alphabetical) are an honor roll of food writers everyone should read. They're an indication of the editing and taste that are apparent on every page.

“I always learn from Jacques,” the great writer and cooking teacher Paula Wolfert once told me about the great cook and teacher Jacques Pepin. I was reminded of her remark reading every page of Jacques Pepin: Heart & Soul in the Kitchen, billed as “the companion book to his final PBS series,” although it's hard to imagine him even slowing down. This book has memoir-ish vignettes of his house on the Connecticut shoreline, his wife Gloria’s tastes and how they shape his cooking and writing recipes, and his time cooking on and off camera with James Beard and Julia Child. These are charming and cheerful, as Pepin unfailingly is in classes, on TV, in life. His observations on wanting to be able to tell, blindfolded, what he’s eating and to flee endless tasting-menu dinners to “grab a taco and beer” will strike loud sympathetic chords in many (in me); he loves wine, but after a friend gave him two bottles of wine worth $7000 apiece he realized the special occasion he was waiting for would never come and gave them away.

Pepin’s observations on wanting to flee endless tasting-menu dinners to “grab a taco and beer” will strike loud sympathetic chords in many.But the value for any cook is in Pepin's ability to reduce any recipe to its essentials, explain them with dispatch, then build flavorings and presentation into them—the very ability that he says suited him to teaching after a bad car accident in 1974 threatened his ability to continue the punishing shifts of a professional chef. I've long given serious apprentice cooks the two volumes of his La Technique, which he points out with rightful pride are still in print 40 years after they were published (compiled as Complete Techniques). That mastery is what gives his recipes their clarity and simplicity: Anyone teaching him or herself to write recipes could use these perfectly concise ones as a model.

Like any constantly thinking cook, Pepin is alive to trends and the markets around him—here, particularly, the Mexican beachside town where he and his wife long spent a month a year. This book has a chapter on offal, and easy recipes for the New England fish I can get too (fluke, flounder, the supreme bluefish), if not from neighboring fisherwomen who appear at my door. It's what he does on the way to recipes, though, that makes Pepin an inexhaustible source of instruction and that compels you to file away hints: Use tostadas as a base for smoked-salmon starters with plain yogurt spiked with horseradish, and flour tortillas as a base for quick lunchtime pizzas; microwave potatoes for ten minutes, the time it takes to heat an oven to 450, then bake them, stuffed or not, to crisp the skins; do the same for sweet potatoes, but halve them, drizzle with maple syrup and run them under the broiler. His recipes are of the moment, his techniques timeless.

Danny Bowien seems about as far as it's possible to be from Jacques Pepin: profane, often drunk, raised in Oklahoma as the Korean-born adopted son to white parents. His discipline, curiosity, and insistence on always getting better are similar, though, and qualities most successful chefs share. What makes The Mission Chinese Food Cookbook—which Bowien wrote with Chris Ying, the editor of the must-read magazine Lucky Peach—compulsively readable is Bowien's voice: fiercely honest, self-critical, incredibly sympathetic.

Although ostensibly a recipe book, this is as engaging and readable a memoir as Kitchen Confidential; Anthony Bourdain wrote the foreword, and the book is part of a series of books under his imprimatur published by Ecco. David Chang, chef of Momofuku and founder of Lucky Peach, wrote a second foreword; much of the book is structured as conversations with Ying, who also worked on the line at Mission Street Chinese, the San Francisco restaurant where Bowien first won a national reputation; with Anthony Myint, a chef who worked with him opening all his restaurants; and occasionally with Rene Redzepi, of Noma.

What saves it from being a cool-kid boy's club—as much of the scene around Bowien's New York restaurant Mission Chinese Food and Chang's restaurants is—is Bowien's spill-it accounting of how it feels to be naive and taken advantage of (a flawed structure at his first New York City location that resulted in two closings by health inspectors, the second one fatal—the chef and his team looked for a new location for more than a year). There are more than enough triumphs: The reopened New York restaurant had the same acclaim and lines of fans as the original San Francisco and New York locations. But Bowien has often faltered, his passion and lack of experience, and tendency to drink too much and order in too much food, getting the better of him.

What makes The Mission Chinese Food Cookbook compulsively readable is Bowien's voice: fiercely honest, self-critical, incredibly sympathetic.The freewheeling recipes, many of them with the same Szechuan-influenced heat at his first restaurants which diners and critics called satisfyingly head-pounding, some with the Mexican influence of his second New York restaurant, Mission Cantina, will appeal to experimenters and chefs, though even I, who am neither, wanted to buy a deep-fryer to try the Buffalo-style wings, which are parbaked the day before, frozen, then slowly defrosted and fried batterless. The recipes, though, aren't the reason to buy the book for any young cook or high-school fan dazzled by reality-TV cooking shows who dreams of being a chef. It's to show what it's like to earn, lose, and re-earn success, and make a lot of mistakes. Also to discover a voice and a writer you'll remember: It just takes his account of losing his mother (which Vanity Fair excerpted) to know why.

What we know about Israeli cuisine we know from the books of Yotam Ottolenghi, whose Jerusalem, Plenty, and other books are immensely popular for a reason—the recipes are beautiful look at, work exactly the way they're written and look, and are an exotic and alluring amalgam of many Mediterranean cuisines, including Italy. Zahav starts with a somewhat stricter Israeli base, from the early childhood and then teenage years of Michael Solomonov, the chef of the restaurant by the same name in Philadelphia (the name is the Hebrew for "gold"). The oversized picture book, again edited and produced by Dorothy Kalins, is part-memoir of a strongly engaged chef who was galvanized by his brother's death from Hezbollah snipers just days after his service in the Israeli military had ended (he volunteered on Yom Kippur in place of more-observant soldiers).

My reading was slowed by constant emails to friends offering Solomonov's firm, clear advice on questions they'd asked over just the past few months: how to make hummus from scratch (essential, he says, and his rhapsodies over its creamy smoothness make me want to try it), latkes without extra starch to bind them (the only way to go, he insists—a feeling not universally shared), marzipan in a food processor (easy if you have corn syrup; he mixes a few pistachios in with the almonds). If the pages weren't so thick, I would dog-ear half the book for recipes and techniques I want to try: at least two of the Persian rice pilafs Solomonov likes to make; leg of lamb roasted medium-rare in a heavy salt crust, a treatment I've seen only for fish, flavored with the Persian ingredients sumac, dried lime, Urfa pepper, and dried rose petals; rugelach with date filling.

The influences here are Bulgarian, for his father's home country ("I was taught that a key difference between the food of Bulgaria and its Balkan neihbor, Romania, is a ton of garlic"), Yemenite, Persian, general "Arabic," and American. Naturally, there are vegetables and salads everywhere, and pickled persimmons, as well as gluten-free Persian chickpea-flour matzo balls. Solomonov writes with warmth and wit. (“Schnitzel gets a bad rap. If you've ever been on a bus tour of Israel or spent time in an Israeli prison, you know what I am talking about.” “To remove the seeds from a pomegranate, place a deep bowl in your kitchen sink and roll up the sleeves of a shirt you dislike.”) By the time you finish a first read of Zahav, you want to visit Israel, cook a lot from the book, and visit Philadelphia to eat at one of Solomonov and his partner Steve Cook’s four (by my count on the website) restaurants. This is a homey book, but there's nothing ordinary about it.

Nancy Harmon Jenkins and Sara Jenkins are among the breed of Americans who learn Italy better than the Italians (a group I long prided myself as being a member of). In Nancy's case, this resulted from years of living in Rome as part of a foreign-correspondent couple in the 1970s and buying a house in Tuscany. Sara, her daughter, lived for part of her childhood in Rome and summer stints in Tuscany. Nancy turned her bent for scholarship and love of the Mediterranean into several books on the Mediterranean diet, and earlier this year a handsome color-photograph book on olive oil, Virgin Territory: Exploring the World of Olive Oil, in which she provides history, tasting notes, recommendations (she's not above Costco and Trader Joe), and of course recipes. Sara became a professional cook and in 2010 opened Porsena, a restaurant in Manhattan's East Village that specializes in pasta. Like her mother, she's a fine writer, as her posts on the former Atlantic Food Channel demonstrate.

Now mother and daughter have written The Four Seasons of Pasta, which stands to be a definitive book on how Italians make pasta every night and how you should, too. It's the most complete and imaginative guide since Fred Plotkin's Authentic Pasta Book and Anna del Conte's two books on pasta. There's nothing dumbed-down or compromised about the recipes, which are far easier to achieve with real authenticity than when Plotkin and del Conte were writing, 20 or so years ago, given that Italian-produced pastas are as available, as the women say, as if they were made next door, and so many more ingredients essential to the Italian pantry are too.

My favorite recipe instruction this year might be “Unearth the pig.”Cooking through the book is a course in how Italians cook, and regional differences: classics like bucatini all'Amatriciana (with guanciale or pancetta, chili, and tomatoes) and carbonara (maybe the most fun introduction to cooking pasta, in which hot pasta cooks beaten egg that binds with pecorino and more guanciale or pancetta into a coating sauce), and a few exotic wanderings like Turkish pasta with garlic-yogurt sauce and brown butter, Moroccan couscous with seven vegetables, and Sicilian couscous with a rich shellfish sauce. There are techniques for handmade pasta and potato gnocchi that Sara calls the seminal dish of her childhood, but the backbone of the book, as it is with pasta up and down Italy, is store-bought dried pasta. Most dishes are uncompromising, meaning full-on Italian ingredients and methods; but some are pretty quick (all are quick to assemble, of course, as all pasta dishes are once the pasta is cooked) and ones I immediately want to try, like maccheroncini with pumpkin, sage, and toasted pumpkin seeds.

“I’ve discovered as much rigor and range cooking Mexican food as I ever found thumbing through Le Guide Culinaire,” Alex Stupak writes in Tacos: Recipes and Provocations. “I’ve tasted sauces that number their ingredients in double digits, count their cook time in days, and possess a flavor so vast and mystifying it borders on psychotropic. I’ve eaten tortillas that are as careful and calibrated as any crusty ficelle.” This comes fairly late in the book, which he wrote with Jordana Rothman (of whom I'm both friend and fan), in a defense of paying decent money for “street food” that is, as Stupak and Rothman admit in a section called “jolie laide,” usually pretty ugly to look at. The book isn’t just an impassioned defense of a food thought to be humble, though it is. It's a guide to a cuisine Stupak fell so in love with that he threw over his work at the modernist-cuisine shrines of WD-50 and Alinea to open Empellon Cocina in Manhattan's East Village, where he serves, yes, mostly moderately priced Mexican cuisine. But his emphasis is on the cuisine part, and on understanding the complexity of a country whose regional variety other writers and chefs, principally Rick Bayless and Diana Kennedy, have plumbed.

By narrowing the book to tacos, many of them traditional (the pork taco al pastor is “my favorite taco on the planet,” a judgement easy to echo) and many of them not (crab cakes, cheeseburgers—a variation Rothman and Stupak's wife discovered reluctantly loved on a research trip to Mexico, joined by Stupak), the authors provide an education for fellow students of the whole country's cuisine. Adventurous ones willing to “be in constant pursuit of those opiate moments” in habanero peppers “just before the capsaicin rolls in” and “heat locks its jaw around your tongue,” to find food-grade lime and white cornmeal to create the base for masa-harina tortillas, since “the difference between a great taco and a crappy taco is in the tortilla,” and to dig a pib, or fire pit, for roasting a whole pig and follow suggestions for what to do during the long wait for it to cook: “watch Boogie Nights a couple times.” (My favorite recipe instruction this year might be “Unearth the pig.”)

Me, I'll probably head first to the East Village for an Empellon Cocina taco. But you should head to this book for writing like this: “Reach for a chipotle salsa, and its smoky purr will tease depth from a filling of long-simmered meat; choose a fresh green chile salsa, and the same taco can transform into a bright and brisk thing, dazzling with vegetal flavor.” It’ll probably have you looking for chiles right after you finish your Christmas shopping.

Why Some Norwegians Want to Give Finland One of Their Mountains

Some people can be especially hard to shop for during the holiday season. What do you get your picky grandpa who has everything? That guy you’ve only been seeing for a few weeks? The cousin you’ve barely talked to in years, but whose name you drew in Secret Santa?

Or that country with whom you’ve shared a border for hundreds of years?

A group of Norwegians has taken gift-giving to a new level this year by proposing to give one of its mountain peaks to Finland. At 1,324 meters (4,344 feet), Halti is the highest mountain range in Finland. But its 1,365-meter-tall (4,478 feet) summit, known as Ráisduattarháldi in Finland, is actually located right across the border, in Norway, where it’s called Hálditšohkka.

The group’s proposal calls for shifting Norway’s border by about 150 meters (492 feet) north and 200 meters (656 feet) east, which would bring the peak of Halti mountain into Finish territory.

“Let us take Finland to new heights!” a Facebook page for the campaign reads.

The idea comes from Bjørn Geirr Harsson, a retired geodesist and a former chief engineer of the Norwegian Mapping authority, according to Aftenposten, Norway’s biggest newspaper. Harsson, 75, first thought of it in 1972 while surveying the Norway-Finland border in a helicopter.

“We would not have to give away any part of Norway. It would barely be noticeable,” he told Norwegian broadcaster NRK last week. “And I’m sure the Finns would greatly appreciate getting it.”

When Harsson learned this summer that Finland was preparing to mark the 100th anniversary of its independence in late 2016, he decided a mountain peak would be a fitting gift, according to The Telegraph. He sent a letter to Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but hasn’t heard back.

Sondre Lund, 25, who lives in Trondheim, Norway, said he created the Facebook page after seeing a Reddit post about Harsson’s proposal. The user behind the post, Braidedbeard, whom Lund suspects is a relative of Harsson’s, gave Lund the OK to launch the page.

Lund said people find the proposal “amusing” and “generous.”

“Supporters like the idea of doing something nice for Finland, and point out that Norway has got plenty of mountain tops,” Lund wrote in a Facebook message. “Some people have noted how it is a bit sad to walk downwards to Finland’s highest point if you come from the Norwegian side.”

Indeed, Norway boasts nearly 200 peaks towering above 2,000 meters (6,560 feet).

The proposal is a rare gesture in a geopolitical climate better known for taking land away rather than giving it up (cough, Russia). And there’s obviously a host of constitutional, legal, geographical, and mapping considerations. But at least one Norwegian government official seems into it. From The Telegraph:

The proposal has already won the support, if not commitment from Anne Cathrine Frøstrup, the head of the Norwegian Mapping Authority.

“It is a very good idea,” she told Norway’s state broadcaster NRK after receiving an email from Mr Harsson last week. "It is a nice gift to give to a country that lacks a high mountain, where the highest point isn’t even a peak.”

Markku Markkula, from the Land Survey of Finland told Finland’s Hufvudstadsbladet newspaper that there would be few legal obstacles.

“It would be a question of an agreement between the two countries,” he said.

The Finnish embassy in Norway has acknowlegded the proposal on Twitter. The Facebook page has received more than 10,000 likes so far, and commenters are mostly in favor of the gift.

“One guy said he thinks the whole thing is ludicrous, but he seems to either be trolling or a bit weird,” Lund said.

The Best Television Shows of 2015

From Master of None and Black-ish to The Leftovers and Mr. Robot, The Atlantic’s writers and editors pick their favorite TV shows of 2015. (For those seeking a lengthier list, there’s also a roundup of the year’s best TV episodes.)

From Master of None and Black-ish to The Leftovers and Mr. Robot, The Atlantic’s writers and editors pick their favorite TV shows of 2015. (For those seeking a lengthier list, there’s also a roundup of the year’s best TV episodes.) DRAMA

FX

FX The Americans

Some shows have certain inevitable plot developments baked into their central premise. When one of those developments arrives finally, it can be anticlimactic—or it can be a moment of transcendence that allows the show to become freer and scarier and more profound. The latter was the case in The Americans’ third season, when the spy couple at the center of the action were outed to … well, no spoilers. Suffice to say, the emotional landscape of the story suddenly shifted in scenes that wereN’t overly dramatic, that were attentive to the sophisticated inner workings of all the characters involved, and that triggered a journey rich with tension and catharsis. Most surprising was the role of religion. The wild card throughout the season ended up being God, as perhaps on some level it always has been.

FX

FX Fargo

I wrote about Fargo early in the season, and everything I said then still holds. Showrunner Noah Hawley’s second outing was a triumph from start to finish: stylish, witty, inventive, and at times almost painfully suspenseful. His skill in juggling disparate elements was frankly astonishing: gruesome murders, UFOs, Bruce Campbell as Ronald Reagan, and countless nods to the Coen brothers’ oeuvre. (In later episodes, there were lovely homages to Miller’s Crossing and Raising Arizona.) My one early quibble about the show—regarding a moderately mystifying character played by Kirsten Dunst—was very satisfyingly clarified. And the rest of the cast was uniformly terrific, in particular Patrick Wilson, who gave perhaps the best performance of his career to date. Am I eagerly anticipating season three? You betcha.

AMC

AMC Halt and Catch Fire

In its first season, Halt and Catch Fire was a frustratingly flawed retelling of the burgeoning computer industry in the early 80s. This year, it refocused on its two female leads (played by Mackenzie Davis and Kerry Bishé) running a computer gaming startup and their inadvertent creation of instant messaging, and became the smartest show of the year. A relevant and surprisingly gripping tale of connectivity and insurgent entrepreneurship in an industry slowly beginning to tilt against independence, Halt and Catch Fire was a thriller one moment, a comedy the next, and a soapy romance a minute after that. It nailed it all, and yet it remains 2015’s most criminally under-watched show.

HBO

The Leftovers

HBO

The Leftovers

The pantheon of what we might call “weird television” contains some truly remarkable feats of creativity—Rover the menacing balloon in The Prisoner; the black oil in The X Files; Smarf. Now, thanks to The Leftovers, we can add purgatorial karaoke, a smoking cult, and the demon Azazel to the list. The second season of HBO’s post-Rapture drama had the same unscaled ambition and existential questions of the first, but it also seemed to incorporate a lot more self-awareness and humor, leading up to an a entire episode where the show’s dead hero ran around an upscale hotel in the guise of an international assassin, then pushed the spirit of the woman who’d been plaguing him into a well; after which she told him the story of her appearance on Jeopardy! and died. It’s eccentric, often cruel, mind-boggling, and deeply unsettling, but it’s the most ambitious drama on television at the moment, and to my mind, the most well executed, from stellar direction to flawless acting to visuals. To the news that a third and final season is coming, I can only say, “Amen.”

USA

USA Mr. Robot

In the four months or so when I was proselytizing Mr. Robot to anyone who’d listen, I didn’t really know how to describe it. Cyberthriller? Family drama? Hacker drama? Redemption story? Morality play? The first season of Sam Esmail’s stunning TV series for USA managed to meld several genres together while somehow transcending it all. The debut season followed the troubled hacker Elliot Alderson (played by the brilliant Rami Malek) as he got mixed up in an Anonymous-like collective in an effort to bring down a Google/Enron-like conglomerate. The show effortlessly embodied its contradictions: nostalgic yet futuristic, cynical yet idealistic, emotional yet stoic, dark yet vibrant. While Elliot suffered severe identity issues, the show always knew exactly what it was doing (even if the audience didn’t). Not since Breaking Bad had a series so fully seized my imagination with its artistry, confidence, originality, and a captivating (anti)hero. Season two can’t get here soon enough.

Lifetime

Lifetime UnREAL

It’s the show that, before this year, I didn't know I needed: a fiction about the fiction that purports to be “reality.” Lifetime’s dark satire of reality TV (well: “reality,” and now, given streaming, “TV”) is also a systematic takedown of The Bachelor and of, really, the romance industrial complex writ large. It’s a show about romance that is decidedly unromantic. But it’s also engaging drama, cleverly written and subtly acted and accomplishing a meaning-and-message interplay that can only be described as “literary.” Co-created by a former Bachelor producer, UnREAL does, charmingly and compellingly, what satire does best: It takes the conventions of the format it mocks and uses them against its subject.

Honorable mentions: Better Call Saul, Jessica Jones, Mad Men, Game of Thrones, and Transparent.

COMEDY

Comedy Central

Comedy Central Broad City

There is no funnier show than this. It’s tempting to argue that the sweetly asymmetrical relationship between Abby and Alana, the celebration of total female liberation, or the skewering of 2015 social hangups are what make Broad City great—and certainly, that’s all part of it. But the main thing is that Broad City does what all great comedy does, which is surprise. It finds comically rich situations—Manhattan banker cruises, gay dog weddings, coat-check rooms—and then creates sub-situations, wormholes from real-world absurdities into psychedelic, imaginative absurdities. Whoa, you’re shacking up with your dream crush—and, uh, whoa, he’s into what? Whoa, you’re hanging out with Kelly Rip\pa—and, uh, whoa, she’s into WHAT?

Netflix

Netflix Master of None

“Oh, wow, that’s so true” is, I’ll admit, an extremely boring reaction to have to a TV show. But I caught myself saying it—in my head and also, occasionally and embarrassingly, aloud—many, many times while bingeing Master of None. The Netflix show, a fictionalized follow-up to its creator and star Aziz Ansari’s sociology-focused book, Modern Romance, is, yes, a jack-of-all-trades kind of deal: It’s a rom-com and a buddy comedy and a family drama and a cultural critique and a mumblecore-esque exploration of life in one’s early 30s. But! Contra its title, the show manages to be, yes, a masterful execution of all of those things. As it tells the story of Dev and his family and friends and love life and career, it also explores topics—racial representation in Hollywood, cultural discomfort with aging, Millennial anxieties about marriage and children-having, the immigrant experience overall, the second-generation-immigrant experience in particular—that might have been plucked from a college syllabus, and that perhaps as a result are discussed only rarely in sitcoms. Master of None, however, brings its sociology to life with empathy and hilarity and also, Ansari being Ansari, wonderfully impish charm.

ABC

ABC Black-ish

Black-ish, in many ways, is one of the more formulaic sitcoms on TV when it comes to conceit: It’s about a loving and well-off family, the dad is a lovable goofball, the mom rolls her eyes a lot, the kids fall into various categories of cool, smart, popular, and happy-go-lucky. But what makes it exceptional is how it tackles cultural issues in a deceptively casual way, never sacrificing humor for the sake of didacticism. In the 10 episodes of season two that have aired this year, the show’s explored guns, religion, health, class, and the n-word, but it’s done so with irreverence and honesty, making it clear that these are issues that TV comedy can and should engage with. “We are driven by what this family’s story would actually be,” its creator Kenya Barris told The New York Times in October. “[We’re] continuing to tell the stories that this family would experience, in a comedic fashion.” The characters might be recognizable as sitcom tropes, but the wit and originality of the show make it feel truly fresh.

Netflix

Netflix Orange Is the New Black

Netflix's Orange Is the New Black shifted pace in season three after an arch-villain-driven story arc to focus more intently on characters’ interpersonal relationships and dynamics. A series of shorter subplots—Crazy Eyes’s fantasy erotica, Nikki’s heroin stash, Norma’s cult, and most notably, Piper’s fetish-feeding used-panty business—allowed the show to spend more time watching how prison life sparked creativity amongst Litchfield's inmates in a way that remained riveting despite the season’s slower pace. And the season’s gorgeous final scene, where the women walk out of the prison and into the lake, was the show's most poignant expression of humanity yet.

Cartoon Network

Cartoon Network Rick and Morty

Funny plus smart can too often equal mean. Rick and Morty, an animated sci-fi sitcom about the antics of a genius mad scientist and his grandson, isn’t immune to playing up its darker, nastier side. But its creators Justin Roiland and Dan Harmon round out that package with goofiness, self-awareness, and a deep capacity to understand its characters’ pain. In other words, barely buried underneath the chaos and sarcasm, is a whole lot of—as my colleague David Sims pointed out—heart. Add that to some of the most inventive plots you can think of (a remote control that lets you watch TV from an infinite number of realities, alien parasites that replicate by forcing their hosts to recall false memories, a rip in the space-time continuum that plays out on 16 split-screens), and you have one of the year’s hands-down best and bravest comedies.

FX

FX You’re the Worst

If I told you a saucy half-hour comedy had embarked on a dramatic season-long storytelling arc about clinical depression and managed to remain funny throughout, you might not believe it. But the proof is in You’re the Worst’s second season, which saddled the show’s acidic central characters with some scary human emotions to deal with, and got laughs out of the ensuing mistakes. Creator Stephen Falk’s effort to tell a funny, personal story about depression without blunting the terrible impact it can have was admirable on its own, but You’re the Worst is also just the most genuinely winning rom-com on TV in years. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll feel incredibly frustrated, and you’ll cheer at the last episode, which concludes with just a perfect exchange of dialogue.

Honorable mentions: Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Bojack Horseman, Inside Amy Schumer, and Key and Peele.

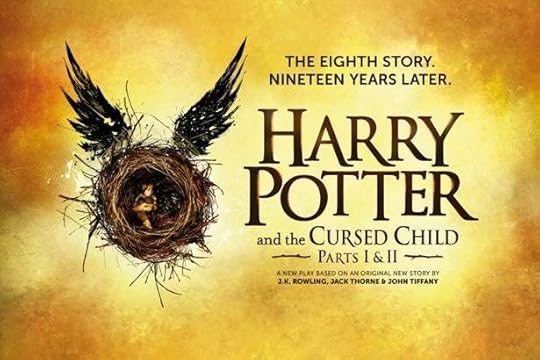

Harry Potter and Theater's Colorblind Tradition

Earlier this year, the director Trevor Nunn sparked uproar when he announced the casting for his fall production of The War of the Roses, an adaptation of three of Shakespeare’s history plays. Of the 20-plus actors chosen for the show, every single one was white. “Can it really be acceptable best practice in 2015 to cast a project such as this with 22 actors but not one actor of color?” asked Malcolm Sinclair, the president of Equity U.K., in a statement. The executive director of Arts Council England, Simon Mellor, added that the production “seems out of step with most of British theatre, where casting that ignores an actor’s race is increasingly the norm.”

Nunn’s decision to cast only white actors, was, the director stated, an attempt to achieve “historic verisimilitude.” But the controversy it prompted served as a reminder that theater has long been ahead of film and television when it comes to colorblind casting. The recent news that a black actress, Noma Dumezweni, has been cast to play the adult Hermione Granger in the forthcoming London play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, continues this tradition. Even though Hermione’s race is never specified in the Harry Potter series, Emma Watson’s casting in the film adaptations confirmed many readers’ assumptions that the character was white, leading to a blockbuster film franchise for children where the only characters of color featured in minor roles. Having Hermione be played by a black actress onstage is both an acknowledgement that the Harry Potter universe has long been lacking in this regard, and an affirmation of theater’s historically progressive attitude toward actors of color.

While theater has long led other creative genres in this regard, it’s done so partly out of good intentions and partly out of necessity—the canon is almost entirely plays written by white men featuring white characters, many of which had to be performed by all-male casts when they were first produced. As the demographics of acting schools shifted in the 20th century, there were an increasing number of classically trained performers looking to tackle theater’s most challenging roles. “The theater was the one place during the McCarthy era where black actors could work,” says Michael Kahn, the artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company. “So there’s always been a more progressive attitude in theater than film. And history, in particular, comes even more alive when you relate it to the community who’s looking at it.”

There’s also a fluidity regarding gender in Shakespeare’s plays that stems from the fact that women weren’t allowed on English stages until the 17th century. The suspension of disbelief required to imagine a male actor being the virginal 13-year-old Juliet, for example, has long made Shakespearian productions more receptive to imaginative casting than many modern shows. “People expect it in Shakespeare,” says the director Julie Taymor, whose recent movie adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream featured black actors playing Helena and Oberon. “It’s oddly enough with him, the great genius playwright, where for a long time now it’s been possible able to do multi-racial casting without anyone blinking an eye, or thinking of his characters as a black person or a white person or an Asian person. They’re just characters.”

Theater’s also had problems when it comes to casting, with the tradition of blackface being prevalent through the 1950s. In 1964, Lawrence Olivier painted his face with ludicrous black makeup to play Othello at the National Theatre in a production whose film adaptation was likened by The New York Times to a minstrel show. It was only this year that the director Bartlett Sher decided not to use blackface for his production of Otello, following the example of a 2014 production at the English National Opera, which was the first major production to cast a white singer in the role and not have him wear makeup. While theater’s led in terms of colorblind casting, it’s taken much longer for the notion to catch on that white actors shouldn’t alter their appearance to try and look like they’re of a different ethnicity.

Nor is casting actors of color in traditionally “white” roles without controversy. In 1997, the playwright August Wilson delivered a speech titled “The Ground on Which I Stand,” in which he analyzed the overarching whiteness of theater in the U.S., stating:

We do not have any theaters of comparable size, quality, and financial resources as our white counterparts that would allow us to support our artists and offer them meaningful avenues to grow and develop their talents and make the contributions to the body of world art of which they are capable. What we have instead is a furtherance of white hegemony and a truncation of our possibilities. Money spent “diversifying” the theater, developing black audiences for white institutions, developing ideas of colorblind casting, only strengthen and solidify this strangle-hold by making our artists subject to the paternalistic notions of white institutions, allowing them to dominate and control the art.

The speech electrified American theater at the time, and led to an impassioned debate over whether black actors should take on historically white roles, or work to create their own canon, as Wilson stated, thus championing “our own causes, our own celebrations, and our own values.” One of Wilson’s most outspoken critics at the time was Robert Brustein, who founded the American Repertory Theater. “Refusing to let black actors play anything but black parts seems narrow to me,” Brustein says. “And it would have robbed us of some of the great performances of our time. One thing we must not do, in theater, is exclude anyone because of race, or because of anything.”

In a creative environment where directors and writers of color are still woefully lacking, the decision to cast a black actress as one of the foremost children’s heroines of the last two decades seems like an acknowledgement of culture’s limitations, and a nod toward trying to make things better. “As a biracial girl growing up in a very white city, I found myself especially attaching to the allegory of Harry Potter’s blood politics,” writes Alanna Bennett at BuzzFeed, who concludes that “painting Hermione as a woman of color [is] an act of reclaiming her allegory at its roots.” A simple nod isn’t enough in and of itself. But casting Dumezweni, an Olivier Award-winning actress, is a start, at least in challenging the default “whiteness” of characters in culture. If theater’s long history allows it to lead, hopefully other genres can learn, and follow.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower