Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 266

December 25, 2015

The Hateful Eight Is a Gory Epic in Search of Meaning

If you see The Hateful Eight in glorious 70-millimeter format, as it’s being presented in limited engagements around the country, it begins with a soaring overture and has an intermission halfway through its three-hour-plus running time. It’s the perfect moment to get up, stretch your legs, and perhaps chat with a nearby friend, as I did. Because the first half of The Hateful Eight begs a question that the second half doesn’t really answer, namely: What’s the point of all of this?

Related Story

The Amorality of 'Django Unchained'

Quentin Tarantino has long revered the epic trappings of the cinema-going experience more than most directors, and for all of its flaws, the experience of seeing The Hateful Eight in 70mm is a genuinely thrilling throwback to an era when a night at the pictures was intended as a real event. But for this wide-screen event he’s chosen an uncompromisingly nasty, brutish story even by his standards: a bloody tale of America reckoning with itself that takes place almost entirely in a large room in post-Civil War Wyoming while a blizzard rages outside. At moments, it feels like Tarantino is really trying to say something about the bizarre, angry jigsaw of people who help make this country the polarized mess it remains today, but once the film shifts into an expected cacophony of violence, whatever that might be slips through his gore-stained fingers.

The Hateful Eight is part-Western, part-drawing room mystery, part-exploitation film, but shot with the most gorgeous lenses imaginable and scored with an epic sweep by Ennio Morricone. The main characters, such as they are, are the bounty hunter Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson), a legendary Union soldier who expertly wields two pistols; John Ruth (Kurt Russell), another bounty hunter looking to claim the price on the head of the brutish criminal Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh); and the Southern renegade Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins), an avowed racist who claims he’s the new sheriff of the town Warren and Ruth are headed toward. A blizzard drives them to take shelter in a nearby haberdashery, where they meet an assortment of odd characters already hunkering down, and from there, the action very slowly unfolds.

Tarantino has long been a self-indulgent filmmaker, but in a way that plays to his unique strengths, spinning gold from long tangential exchanges of dialogue or curious flashbacks that eventually snap into his films’ main plotlines with a satisfying click. The Hateful Eight never quite finds the delightful rhythm that makes Tarantino’s shaggy masterpieces Jackie Brown and Inglourious Basterds so lovable, despite their many digressions. Most of the film’s eight major characters get a ploddy introduction, with fifteen minutes of windy expositional dialogue devoted to their convoluted backstories so that audiences know exactly where everyone stands (or, at least, purports to stand) when the climax arrives. Warren escaped a Confederate prison under mysterious circumstances; Mannix rode with a scary-sounding band of Southern renegades committing atrocities; many more such yarns are exhaustively recounted, and the only real tension comes from trying to guess at what’s true and what isn’t.

His actors mostly dig into their roles with real relish. Goggins is, right now, the screen’s greatest slack-jawed Southerner, whether he’s playing a buffoon (as in Spielberg’s Lincoln) or a wily mastermind (TV’s Justified). Here, he’s a fascinating mix of both, never quite tipping his hand either way. Jackson, too, finally gets a showcase role again from Tarantino—his first since he was the slimy, villainous lead of Jackie Brown—and shows just what an electrifying actor he can be given a weighty role. Warren is handed the film’s worst moment, an absurdly long monologue about the violation and murder of an offscreen character, and just about manages to sell it even though it indulges all of Tarantino’s worst impulses to shock his audience with embarrassingly gross content.

Leigh clearly relishes her character’s villainy, almost as much as the film takes pleasure in raking her over the coals, subjecting her to constant verbal abuse, beatings, and much worse (I’ll steer clear of specifics to avoid spoiling the film’s incredibly demented conclusion). But for all the exposition and flashback, The Hateful Eight struggles to explain exactly what makes Domergue so evil, and why she’s the focal point the film’s plot eventually begins to revolve around as characters like the hangman Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), the grunting Mexican caretaker Bob (Demian Bechir), and the soft-spoken cowboy Joe Gage (Michael Madsen) sniff around on the sidelines. After a lot of setup, Tarantino does set the gears of his overarching story in motion, and the film’s conclusion is undeniably arresting, and maybe the most shockingly violent work of his career. But the point remains elusive.

As Warren, Ruth, Mannix, and Domergue arrive at Minnie’s Haberdashery, one of the men they meet is a retired Confederate General, played with grumpy relish by Bruce Dern. Of all the film’s characters, he immediately poses the least threat, but his bloody legacy in the Civil War is much discussed, unsurprisingly reviled by Warren and revered by Mannix. That toxic atmosphere pervades the film, and as seeming enemies are forced to strike uneasy alliances later in the film, it feels like Tarantino is trying to talk about the bizarre patchwork that makes up modern American society, and the dark history underpinning its modern conflict. It doesn’t work. The Hateful Eight is too extreme, too ghoulishly violent, too besieged by its ensemble’s overriding villainy, to feel like anything but a dark chamber piece. Its ultimate pitch is this: If you lock a bunch of angry, wounded, and evil creatures in a room, they’ll tear each other apart. The only mystery is to how it’s going to happen, and that’s not enough to justify this three-hour symphony of flowery dialogue and explosive gore.

'Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming' Is a Musician's Christmas Carol

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs : an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming is an easy carol to write about, because I do not have to convince you it is beautiful. Pull up any choral recording, slide over to the penultimate phrase—“amid the cold of winter”—and listen hard to that last word. Between the first and second syllable of winter, the minor chord blossoms into major.

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

I mean this seriously: What else is there to say? Here is the chill of winter transfigured into an ardent flame; here is theology as harmony. Lo, How a Rose even includes an extended pastoral analogy and an allusion to the Book of Isaiah. I’m not a Christian, but I’m at a loss as to what more you could want from sacred music. Kazoos?

Most Christmas carols, and most of our popular music generally, exist for the rhythm or melody. Consider how much mileage “Angels We Have Heard on High” gets out of its cascading glorias, or how much of the fun of “Carol of the Bells” springs from its icy intervals or insistent tempo. But Lo How a Rose exists for the chords. There is almost no rhythmic variation: The four voices move together, syllable after syllable, in patient homophony. This is a hymn about beholding and listening. It’s about watching revelation flourish.

It’s been about this since the beginning. Many Christmas tunes date back centuries, but what’s striking about Lo How a Rose is that it is old as a coherent piece of music. However ancient it is, “Greensleeves” has changed a lot: The lyrics used to talk about a prostitute, now they talk about Jesus. But Lo How a Rose has pretty much been the same since its inception in the early 17th century.

The tune we now know first appears in a regional hymnal in 1599 as Es ist ein Ros entsprungen. Michael Praetorius, a court composer in central Germany, writes the familiar harmonization ten years later. Such ends the meaningful musical history of Lo How a Rose. There have been a few changes to the text since then—more German verses were added in the 19th century, and the most common English translation was written in 1894—but essentially none to the music. Hear the song today—in church or in a mall—and you’ll almost certainly hear the exact chords Praetorius picked, in the order he picked them.

As it was written for choir, there’s no good solo version. Sting’s sometimes-cited 2009 cover isn’t the exception that proves the rule here. Rather, it’s the the embarrassment—of pizzicato strings, of whispered text, of bizarro pronunciation—that should convince all future artists not to test the rule, ever.

Even Sufjan Stevens’s cover is less a solo version than an instrumental version that happens to include singing. Stevens’s doubled vocal is lovely, sure, but I’m moved more by hearing his distinct orchestration—glockenspiel, banjo, guitar—brush its way into each chord after scintillating chord.

These versions are lovely, but they’re not exactly justifying corporeal existence. For that, we have to turn to the Swedish composer Jan Sandström’s more recent choral arrangement, Det är en ros utsprungen. Every harmony has been taken from Praetorius’s original and extended, embellished for maximum ethereality.

I’ve heard it said that, when written music succeeds, you enter a single life-world designed by the composer and awakened by the performers. We don’t only enter Sandström’s version, though. He gives us time to wander around, look at the decor, and settle into a sofa made of well-tuned vowels. If you can ignore the screensaver-style visuals, here is a fine recording, from the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge:

Perhaps later generations, less hung up on attention than ours, will find other ways to ornament Praetorius’s score. Maybe their arrangements will dwell less in meditation and more in quickly oscillating rhythm. Yet the core will still remain. For more than 400 Decembers, singers have waited on Lo How a Rose. It is a text in sound, it is a set of tones and pauses, it is a cogent path of breath and time.

An Unexpected Stop in Pakistan

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made a surprise visit to Pakistan to meet with his counterpart, Nawaz Sharif—the latest step in an often-fragile process of rapprochement between the two neighbors.

Modi, who was returning home to India after a visit to Kabul, stopped in Lahore to meet with Sharif, ostensibly to offer the Pakistani leader wishes on his birthday.

Spoke to PM Nawaz Sharif & wished him on his birthday.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) December 25, 2015

Looking forward to meeting PM Nawaz Sharif in Lahore today afternoon, where I will drop by on my way back to Delhi.

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) December 25, 2015

Dawn, the Pakistani newspaper, reported that Sharif and Shahbaz Sharif, the prime minister’s brother who governs Punjab province, Pakistan’s largest, received Modi at Lahore’s Allama Iqbal International Airport. The two leaders then flew by helicopter to Nawaz Sharif’s private residence in Raiwind, Dawn reported.

The visit is the first by an Indian leader to Pakistan since 2004, but this meeting capped months of diplomacy between the two neighbors, whose relations since near-simultaneous independence in August 1947 have mostly been tense. They have fought three wars, engaged in countless skirmishes, and hurled claims and counterclaims over support for terrorist groups and border violations. Diplomacy between the two countries is often the victim of politics and public mood, but ties have been on a relative upswing since Modi was elected in 2014.

Sharif, and other regional leaders, attended the ceremony at which Modi was sworn in, and diplomacy has continued despite regular finger-pointing. Modi and Sharif met briefly last month on sidelines of the climate-change conference in Paris, and, earlier this month, Sushma Swaraj, India’s external affairs minister, visited Pakistan for talks with her counterparts. Modi’s visit to Pakistan caps those efforts, but it’s unclear what the long-term implications of such a visit are besides the initial groundswell of optimism for better relations. Pakistan’s military, which often holds the trump card in the country’s political process, was silent about the visit.

Manish Tiwari, the spokesman for the centrists Congress Party, which headed the previous government, called it a “misadventure.”

PM's misadventure to Lahore is worst manifestation of Spectecalisation of Diplomacy Last time Vajpayee went to Lahore Kargil!this time what?

— Manish Tewari (@ManishTewari) December 25, 2015

The reference is to a previous visit by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who also belonged to Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, to Pakistan in 1999. That meeting, also with Sharif, who was prime minister at the time, was met with great optimism both countries, but later saw them come close to a fourth war in Kargil.

Others in India were more optimistic.

Omar Abdullah, who heads the National Conference in India’s Jammu and Kashmir state, tweeted:

The re-engagement with Pakistan is a good step & a very welcome development. However more than grand gestures we need consistency.

— Omar Abdullah (@abdullah_omar) December 25, 2015

Indo-Pak relations have been plagued by knee-jerk reactions & a lack of consistency. Looking towards two PMs to correct this this time.

— Omar Abdullah (@abdullah_omar) December 25, 2015

Dawn, the Pakistani newspaper, added:

Meanwhile, Prime Minister's Adviser on Foreign Affairs Sartaj Aziz told the National Assembly that the foreign secretaries of Pakistan and India will meet soon to discuss modalities regarding the bilateral dialogue which will include matters related to peace and security, Jammu and Kashmir, Siachen, Sir Creek, Wullar Barrage, Tulbul Navigation Project, economic and commercial cooperation, counter-terrorism, narcotics control and humanitarian issues, people to people exchanges and religious tourism.

The Mysteries of 'The Twelve Days of Christmas'

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

For a crash course in the strange and ever-changing nature of holiday traditions, head to the Wikipedia page for “The 12 Days of Christmas.” There, you will find that the exact origin of the counting carol are murky, but probably involve French folk songs for the New Year. You will find no agreement about the meaning of the 12 individual gifts—the partridge in a pair tree, the ladies dancing—though you will find speculation; one persistent but unsubstantiated claim says the song was invented to allow persecuted Catholics to practice the catechism in secret. You will find a staggering number of variants in the kinds of objects mentioned, the number of items, and even the syllables in some verses, depending on where and when the song is sung. You will learn that “four calling birds” were once “four colly birds,” colly being an old regional English word for “black.”

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

“The 12 Days of Christmas” is probably the best song to encapsulate the fragmented thing that Christmas has become across culture and across the centuries. By counting to 12 days, it reminds of Christmas’s larger religious-seasonal context, connecting December 25 and January 6, Epiphany (though depending on when you start counting, the beginning point might be Boxing Day, December 26, and the end point might be Feast of Epiphany, January 5). But the extreme specificity of its lyrics, and the way that they are a bit bizarre to a modern audience—who gives one lord a’leaping, much less eight?—reminds carolers that they are taking part in something much older and bigger than them, something essentially unknowable. It turns the sometimes crass-seeming practice of Christmas gift-giving into something noble and lovely and weird; its extremely repetition nature might even convey something about the recurrence of the holidays, or at least about their dull inevitability.

The musical structure, set in place by a 1909 English composer’s sheet music, is a an impressive example of how repetition in music best succeeds when accompanied by variation, hence you have moments like when the time-signature changes for “five golden rings.” This makes the song as fun as it is to sing, and maybe even more fun to rewrite. All major Christmas songs have been covered and deconstructed countless times, but “12 Days of Christmas” updates—or defacements—are especially potent because of the song already seems like a Mad Lib. Earlier this year, the RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant Katya released a filthy/funny parody, which is very much in line with a tradition of vulgarizing “The 12 Days of Christmas”: Think Fay McKay’s “12 Daze of Christmas,” where the gifts are alcohol and the performer gets drunker as she goes along.

Which made me wonder whether there’s an counter-tradition from the other side of the culture wars, of churches rewiring the cryptic, antique-like words of the song to be more straightforwardly evangelical. Sure enough, there are a lot of “Christian 12 Days of Christmas” on YouTube. The first on-stage choir I watched opened this way: “On the first day of Christmas my savior gave to me / the light so the blind can now see.”

December 24, 2015

A Christmastime Pardon for Robert Downey Jr.

California Governor Jerry Brown has pardoned 91 people, including Robert Downey Jr., the actor, who spent more than a year in prison following a drug conviction in 1996.

Downey was sentenced in November 1996 for possessing a controlled substance, carrying a concealed weapon in his vehicle, and driving under the influence. He spent a year and three months in prison. Downey, as well as the 90 others who were pardoned on Thursday, had, according to Brown’s office, “all completed their sentences and have been released from custody for more than a decade without further criminal activity.”

California’s pardons are granted to those people “who have demonstrated exemplary behavior following their conviction,” Brown’s office said. The pardon does not seal or expunge the criminal record of Downey or the others. It does, however, among other things, restore voting rights and allow those pardoned to serve on juries. Downey’s pardon said he had “lived an honest and upright life, exhibited good moral character, and conducted himself as a law-abiding citizen.”

Downey is now one of Hollywood’s most bankable actors, having starred in the Iron Man and Avengers franchises that have grossed billions of dollars worldwide. The Sacramento Bee adds:

Downey, Jr. contributed $5,000 to Brown’s 2014 re-election bid and was inducted this year into the California Hall of Fame. He also gave about $50,000 this year to a charter school the Democratic governor started when he was mayor of Oakland – the Oakland School for the Arts.

Brown typically issues his pardons around Christmas and Easter. The Bee adds: “He has far outpaced his predecessors in the Governor’s Office, and Thursday’s batch brought his total to 683 since 2011.”

Storms Strike the South

Updated on December 24 at 2 p.m. ET

At least 10 people are dead and dozens injured as unusual pre-Christmas tornadoes ripped through three Southern states on Wednesday, and threatened more areas on Thursday.

In Mississippi, at least six people were killed and 60 injured in the storms, the state’s Emergency Management Agency said. Three people died in Tennessee, and one person in Arkansas.

Parts of Georgia and southeast Alabama were placed under a tornado watch until mid-morning on Thursday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Storm Prediction Center.

“A more marginal widely dispersed risk for severe thunderstorms exists from parts of the mid-Atlantic region southwestward across the southern Appalachians to East Texas,” the center said.

At least 14 tornadoes hit Mississippi on Wednesday, the center said, but it was a single one that did the most damage. Here’s CNN:

It started in northern Mississippi and didn't lift up until western Tennessee. The National Weather Service said it may have been on the ground 150 miles.

Several small communities in northern Mississippi were affected. Two people, including a 7-year-old boy, were killed in Marshall County; four people were killed in Benton County. In Tennessee, all three deaths were in Perry County, southwest of Nashville. In Atkins, Arkansas, an 18-year-old woman was killed when a tree crashed into the bedroom she was sharing with her 18-month-old sister. The toddler was rscued.

Greg Carbin, a meteorologist at the national Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma, told NPR the storms are unusual, but “certainly not unprecedented.”

Tornadoes in southeast Mississippi at this time last year killed four people.

The Adorable Grandiosity of ‘O Come All Ye Faithful’

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

Adore is a curious word. In English, it’s become a cutesy toss-off, best used around baby chicks (“Adoooorable!”) or under-$50 Christmas presents (“Oh, I just adore Yankee Christmas Candles!”). It denotes obsession, but in a sugar-high kind of way—a burst of intense affection that doesn’t necessarily reach the depths of the soul.

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

But the word comes from a serious root: the Latin, adorare, to speak or pray. It is a worship word, one of prostration that lifts the eyes up rather than turning them to the ground. And it is the central idea of “O Come All Ye Faithful.” Oh, come, let us adore him: a straightforward call to prayer, urging everyone to drop what they’re doing and gather round, for “born the king of angels.”

It’s slightly disorienting to hear this exhortation in present-day, though. With its contemporary connotations, Adore feels more like a descriptor of Jesus’s baby-ness than his divinity-ness. Babies are undeniably awesome, but Jesus is supposed to be awe-some; his general-variety cooing is not quite what Christmas is about.

That’s why composition is everything. I tend to find contemporary Christmas music baffling, if not outright terrible; give me the boys’ choirs and magisterial organ-playing, please. For “O Come All Ye Faithful,” I always get a little tingly listening to this version, by the famous choir of King’s College, Cambridge:

Listening to this, there’s no mistaking adore as a synonym for squeal with glee; it is an expansive adore, enough to reach the rafters of a towering Gothic chapel. This seems like the best beyond-aesthetic justification for turning up one’s nose at the Faith Hills and Elvises and Weezers of the world: In remixing the archness of the traditional version, they lose a little of its existential grandness. Yes, even Weezer:

To be sure, their version is catchy. But it lacks the gravity of earlier renditions, first known to be published in 1751. Sometimes, the sweetness of adoration can obscure the heft of the act, one that can be such an important part of human life. Adoration: the joyful, wondrous experience of humans in relation to God.

A Possible Threat to Westerners in Beijing

The U.S., British, and other embassies in Beijing warned their citizens to be vigilant in the popular Sanlitun neighborhood on or around Christmas Day.

“The U.S. Embassy has received information of possible threats against Westerners in the Sanlitun area of Beijing, on or around Christmas Day,” the U.S. Embassy said in a statement issued on Thursday. “U.S. citizens are urged to exercise heightened vigilance. The U.S. Embassy has issued the same guidance to U.S. government personnel.”

Neither the nature of the threat nor its origin was specified.

The British Embassy issued a near-identical warning. Warnings were also issued by the embassies of Australia and France.Sanlitun is an area in Beijing’s Chaoyang district. Popular with tourists, it has several bars and restaurants. It is also home to several foreign embassies, though the U.S. Embassy is located elsewhere.

Xinhua, the state-run Chinese news agency, reported that Beijing police had initiated on Thursday a yellow security alert malls and supermarkets during the Christmas season. Here’s more:

A yellow alert is the second mildest under the four-coded alert system, which goes from green, yellow, orange to red in order of severity. It means 60 percent of the security personnel in those shopping malls and supermarkets should carry out security checks on suspected personnel, materials and vehicles, according to a government security prevention regulation.

All trash bins in public areas should be checked every 30 minutes, according to the regulation.

The BBC adds armed police were deployed Thursday outside shopping malls in Sanlitun.

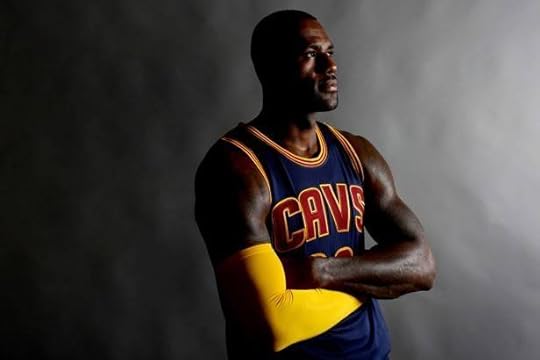

LeBron James: Player, Coach, or Both?

One early November night, during a game in downtown Cleveland, LeBron James received a pass on the left wing. Actually, “received” may not be the right word here, because instead of catching the pass with both hands James simply palmed it for an instant in his left and, with a flick, sent it arcing across the court. The defense had shifted in James’s direction, as defenses are wont to do, and he had spotted his teammate Richard Jefferson alone in the opposite corner. Some 50 feet of distance separated James from Jefferson, a gap populated by all five opponents, but James’s pass spanned it safely, curving over the defenders’ reaching hands and landing in Jefferson’s, who needed only to make an open three-pointer. He did so, extending the Cavaliers’ lead.

Perhaps five players currently in the NBA have the vision and tactical aptitude to spot an opportunity like the one James did that evening. Fewer have the combination of strength and touch necessary to pull off a pass like the one he threw—with his weaker hand, no less. Special as it was, though, the play was just one entrant into a catalog of impossible feats that he’s added to nightly since his arrival in the league in 2003. Standing six feet, eight inches tall and weighing 250 pounds, James looks like he’s made of pure steel and runs like he’s made of pure tendon. He does most everything that can be done on a basketball court. He spins around some defenders and shoulders through others, rams home violent dunks and coaxes in feathery fadeaways, passes like a point guard and rebounds like a center. James is a marvel of ability and acumen, the type of player that Jules Verne may have dreamed up, were he a basketball fan.

This season, James is playing the way he has throughout his 12-year career. Once again, he leads a team at the top of the Eastern Conference, figures in the Most Valuable Player race, and does something almost every night that makes basketball fans rewind their DVRs and scramble to upload Vines. Increasingly, though, and through tactics largely unprecedented in contemporary professional sports, he’s begun to expand his already sizable influence within his organization. He now contains components not only of the point guard and the center, but also of the coach, the general manager, and the owner. This evolution isn’t unanimously lauded; the sports world celebrates the quasi-militaristic selflessness that’s central to the mythos of The Team. But in a career full of rising stakes, these may be the highest yet: James is trying to bring a championship to Cleveland and, simultaneously, to reshape the scope of athletic superstardom.

* * *

At 30 years old—he turns 31 on December 30—James has already gone through plenty of iterations. He’s played in six NBA Finals, winning two, and has left and returned to his hometown team. The fans who worshipped him as a teenager cursed him in his late 20s and now praise him again. Last year, James’s first back in Cleveland after the sabbatical in Miami that brought him his two titles, he dragged an injured and shorthanded Cavaliers team to the championship round. It was the start of a phase that local fans hope lasts a while, that of the prodigal icon bent on ending the city’s six-decade championship drought.

It was also the start of a consolidation of power that even James hadn’t attempted before. LeBron James now is the Cleveland Cavaliers, the team’s engineer and engine, responsible for most every aspect of its design and execution. When he came back to Ohio, he signed a two-year deal with an opt-out clause after the first year—a contract that gave him substantial leverage that he’s since parlayed into a level of sway unheard of in recent basketball history. He can leave again any offseason, in theory, so ownership and management have an ever-present incentive to cater to his vision of a contending team.

James is commonly understood to have a significant say in personnel decisions. In his announcement of his return in Sports Illustrated, he mentioned several Cavaliers but omitted the recent number one overall draft selection Andrew Wiggins; within a month, Wiggins was traded to Minnesota for Love. Last season, after a slow start, he reportedly approved the team’s deals for a group of complimentary players who, upon their arrival, helped the Cavs play their best basketball of the season. This past offseason, the power forward Tristan Thompson, who shares an agent with James, held out of training camp in the hopes of a longer-term contract; James publicly advised the team to “get it done!”

James now is the Cleveland Cavaliers, the team’s engineer and engine.James is also considered the closest thing in the present NBA to a player-coach. The arrival of the Cleveland head coach, David Blatt, coincided with James’s return, and the relationship between the two has been far from the Hoosiers vision of instructor and pupil. Rumors of James’s overruling Blatt or conferring with an assistant coach circulated throughout last season, and after the Finals, the ESPN reporter Marc Stein published a lengthy piece criticizing James’s treatment of the man nominally in charge. Other outlets, including Deadspin, pushed back against Stein’s interpretation, arguing that James’s taking control afforded the Cavaliers their best chance to win.

If the rumors of James-Blatt conflict have quieted this season, it’s not because of any new deference from the player. Indeed, scan Cleveland gamers, and you’ll find James’s quotes where the coach’s usually are. He tells reporters what strategic deficiencies need shoring up and when the level of focus has slipped. After an early-season win over the Memphis Grizzlies, James told Cleveland.com about the team’s emphasis on involving Love in the offense: “I told you Kevin is going to be our main focus. He’s the focal point for us offensively.” Following a mid-November loss to the Detroit Pistons, he said, “We are too relaxed and too nice. We need to get tougher ... We’ve got some guys who do that all the time, and some guys who don’t.”

* * *

The popular understanding of professional sports is, in many ways, a celebration of hierarchical organization. Athletes, the thinking goes, perform at their best when they sublimate their instincts into the refined visions of their coaches. Some version of this argument is made nightly, by television announcers, by fans in bars, by reporters in the premises of their questions. A play goes wrong, and the ready explanation is that some player along the line failed to obey instruction, out of foolishness or selfishness or hubris.

Such sentiments aren’t found only in the rapid-fire output of modern-day media. David Halberstam’s canonical piece of basketball literature, 1981’s The Breaks of the Game, contends early on, “Power was for the coaches an illusory thing ... It was these players who could, if they listened and obeyed, make the coaches seem more successful and thus more effective, yet it was these players over whom it was impossible to exercise authority directly.”

Winners obey; losers defy. This is how sports stories tend to be told. There’s no hero more valuable to this narrative than the one who finds ultimate success only with a certain mentor, like Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant under the tutelage of Phil Jackson. Per this understanding, talent alone doesn’t get it done; in fact, too much talent may be a poison, a threat to the ability to take direction. Players must be brought in line.

Winners obey; losers defy. This is how sports stories tend to be told.These notions rest on certain assumptions: that a team’s best player can’t also have an organization’s keenest basketball mind, or that a superstar capable of dismantling or overrunning a defense can’t simultaneously consider the macro-problems of game and season. The thrill of James, at the present moment, lies in his ability to supersede this conventional thinking. He explodes the binaries with which we position our athletes. His occasional resistance to coaching might lump him in with players deemed “selfish” if his gift for passing didn’t immediately refute such a charge. His influence regarding personnel decisions could make him seem “pampere,” if his team-building instincts weren’t so often proven correct. The top-down, traditional organization is one well-tested way to find success in the NBA, but another viable one seems to be: Employ LeBron James, and let him do as he pleases.

* * *

As they do on every team, certain issues arise in Cleveland from time to time—injuries, ill-fitting personnel, the general tribulations of a team without much experience at basketball’s highest level trying to find its way. James has provided the solutions for most every one of them. He envisions an offense that makes the best use of the Cavaliers’ players, advocates for acquisitions that shore up roster deficiencies, and, when all of that doesn’t quite do the trick, takes it upon himself to fix things.

The Cavaliers entered their December 8th game against the Portland Trail Blazers in a bit of a funk. They had lost three in a row, the last of which James missed for the purposes of rest, and had arrived at their lowest win percentage since a season-opening loss put them at 0-1. Though the situation was explicable and hardly dire—Cleveland’s preferred starting backcourt had been wholly absent to that point, recovering from offseason surgeries, and their record still put them among their conference’s elite—a win that night would have been more pleasant than usual.

James played 40 minutes against Portland, scoring 33 points, grabbing 10 rebounds, and adding in three assists, three blocks, and two steals. He was at his omnipresent best, draining stepback jumpers and tearing to the rim, bellowing out orders on defense and materializing to snuff a shot when a Trail Blazer slipped through. With a minute left and the Cavaliers holding a six-point lead, James stepped past his defender, drew a foul, and, falling to the floor, tossed in a parabolic floater, ensuring the victory. He lay there a second, smiling, before his teammates ran over to lift him up.

James explodes the binaries with which we position our athletes. It seemed almost as if James were providing an allegory of his own importance, although, of course, that gets it backwards. James has always been able to play like he did that evening. His off-court, behind-the-scenes stature is what’s been added; his ability to steer an entire organization as deftly as he negotiates a pick-and-roll.

On Christmas day, as part of the NBA’s traditional slate of marquee games, James and the Cavaliers will play the Warriors for the first time since last season’s Finals. The game will present a contrast in styles. Despite what their respective nicknames connote, the Warriors play a whirling brand of basketball, while the Cavaliers rely on a buttressed defense and a more stolid offense.

The biggest difference, though, may be ideological. The Warriors won their title last June and have flourished so far this season by adhering to the model that fans and commentators everywhere can recognize. Their head coach, Steve Kerr, installed a system so thorough and stable that their assistant coach, Luke Walton, can run it with great success in his stead (Kerr has missed all of this season following complications from a summer back surgery). The Warriors’ players, in a piece of line-toeing that would make Halberstam rejoice, have vocally and unanimously supported the substituting Walton. Though they have the reigning MVP Stephen Curry, who seems likely to garner the award again this year after a torrid start, they play in the sort of elegant, clock-gear fashion that inevitably leads to thoughts of its designer.

Cleveland, meanwhile, leans largely on the on-court ability and large-scale understanding of one transcendent player. This model predisposes James and the Cavaliers to certain common criticisms. Poring over their losses, the sports world treats them as a fable’s vain fool, the hare to the league’s wiser and more temperate tortoises. When they win, though, they seem like bringers of some sporting revolution, wherein duties are fashioned to fit abilities, not the other way around. If James can lead Cleveland to a title, he won’t merely have delighted a city. He will also have staked out new ground for the athlete-dissident, that player who dares go rogue in the field where the public most adores order.

Jingle Bells: A Racy Drinking Song (For Thanksgiving)

Welcome to The 12 Days of Christmas Songs: an attempt to uncover the forgotten history of some of the most memorable festive tunes. From December 14 through 25, we’ll be tackling one secular song and one holy song each day.

“Jingle Bells”: It’s the most wonderful song of the year (maybe). There are bells on bobtails ringing, and horses dashing through snow, and spirits made bright, and laughter galore. Its tune and lyrics are synonymous with Christmas, not to mention the sound of sleigh bells, which are so festive at this point that everyone from Eels to Low throws them into their indie Christmas jams.

The 12 Days of Christmas Songs Reflections on the music of the season, both secular and sacredRead more

There’s only one problem: “Jingle Bells” doesn’t mention the word “Christmas.” And according to the checkered history of the song and its composer, it was written for Thanksgiving. As a drinking song. And a Sunday school song. And a jaunty tune about frolicking with ladies. Written in Massachusetts. And Savannah. By a Bostonian who lost all his money in the California Gold Rush, and who followed up the success of “One Horse Open Sleigh,” as his magnum opus was then known, by writing battle songs for the Confederacy, even though his father and brother were both abolitionists.

Not all of this can be true, of course, although the last part is perhaps the most reliable. “Jingle Bells” is attributed to James Lord Pierpont, who was born in Boston in 1822 and grew up in New England. His father was a reverend and a poet; his uncle was the financier John Pierpont Morgan, better known by his initials, J.P.

Pierpoint Jr. was something of a wayward youth, running away to join a whaling ship, and pursuing various ventures during his life, most of which were unsuccessful. “Jingle Bells” is his undisputed greatest professional achievement. The Medford Historical Society claims that in 1850, Pierpont composed the song “Jingle Bells” in the Simpson Tavern in Medford, Massachusetts. Savannah, for what it’s worth, also claims ownership of the song, and it was indeed in Georgia that Pierpont first published the song in 1857, and where it was reportedly first performed at a Thanksgiving Sunday School service.

But here, again, it gets sticky. The original lyrics of “One Horse Open Sleigh” are a little, well, racy. The second verse, for example:

A day or two ago

I thought I'd take a ride

And soon, Miss Fanny Bright

Was seated by my side,

The horse was lean and lank

Misfortune seemed his lot

He got into a drifted bank

And then we got upsot.

Upsot! And the fourth verse:

Now the ground is white

Go it while you're young,

Take the girls tonight

and sing this sleighing song;

Just get a bobtailed bay

Two forty as his speed

Hitch him to an open sleigh

And crack! you'll take the lead.

“Go at it while you’re young!” It’s difficult to imagine fresh-faced children singing this for a Unitarian Thanksgiving service in the 1850s. Funny, but difficult. There are also claims that “Jingle Bells” was a popular song to drink to in the 19th century, and that guests as parties would “jingle” the ice cubes in their glasses while they sang along.

What’s certain about the song is that its big moment came in 1943, when Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters recorded a version so popular it’s still played at Christmastime now. More to the point, Barry Manilow has covered it. And Bart Simpson, albeit with slightly different lyrics.

So the next time you hear “Jingle Bells” in church, or at a holiday party, or on the radio in one of its several thousand popular renditions, it’s worth remembering the uncertain history of the song, its fast-and-furious imperative, and how things worked out for James Lord Pierpont, who died at the relatively senior age of 71 in Florida, far away from the snowy sleigh rides of his feckless youth. Seven decades after his death, the work he’s best-known for became the first song to be broadcast from space. Dream on, dreamers.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower