Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 263

January 1, 2016

New Year, New Wages

Those fighting for a higher minimum wage have cause to celebrate, as the start of 2016 means laws raising the minimum wage go into effect in 12 states. Additionally, the minimum wage in Maryland and DC will go up in July, and inflation adjustments will be made to raise the minimum wage in Colorado and South Dakota as well. A handful of cities and counties, including New York, will also see minimum-wage increases.

Efforts to raise the minimum wage paid off in 2015, and as the movement has gained momentum—the current target for many activists and some economists is $15 an hour—the debate over whether raising minimum wage is a good idea will likely become even more heated in 2016.

On the side for raising minimum wage, labor activists argue that the current minimum wage is not enough to live on. There’s also the argument that raising it might also be beneficial for closing the gender wage gap, as women are more likely to hold minimum-wage jobs. And though raising the minimum wage would raise costs for employers and likely prompt them to eliminate several jobs, the net effect is believed to be positive, because higher wages have the potential to pull many out of poverty.

Those skeptical about raising the minimum wage rightfully worry about it decreasing employment (which happened in Puerto Rico, a commonly cited case study). A recent report from the San Francisco Fed argued another point: that raising the minimum wage helps individuals with low wages much more than it helps impoverished families. This is the camp that believes the issue of inequality is better served by raising the Earned Income Tax Credit, a subsidy for low-income families.

It’s in this context that more than a dozen states are raising or adjusting their minimum wage this year. The next battleground, for both proponents and critics, is likely the debate over raising the federal minimum wage—a debate that’s likely to feature prominently in speeches from 2016’s presidential hopefuls.

All Stories Are the Same

A ship lands on an alien shore and a young man, desperate to prove himself, is tasked with befriending the inhabitants and extracting their secrets. Enchanted by their way of life, he falls in love with a local girl and starts to distrust his masters. Discovering their man has gone native, they in turn resolve to destroy both him and the native population once and for all.

Avatar or Pocahontas? As stories they’re almost identical. Some have even accused James Cameron of stealing the Native American myth. But it’s both simpler and more complex than that, for the underlying structure is common not only to these two tales, but to all of them.

Take three different stories:

A dangerous monster threatens a community. One man takes it on himself to kill the beast and restore happiness to the kingdom ...

It’s the story of Jaws, released in 1976. But it’s also the story of Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon epic poem published some time between the eighth and 11th centuries.

And it’s more familiar than that: It’s The Thing, it’s Jurassic Park, it’s Godzilla, it’s The Blob—all films with real tangible monsters. If you recast the monsters in human form, it’s also every James Bond film, every episode of MI5, House, or CSI. You can see the same shape in The Exorcist, The Shining, Fatal Attraction, Scream, Psycho, and Saw. The monster may change from a literal one in Nightmare on Elm Street to a corporation in Erin Brockovich, but the underlying architecture—in which a foe is vanquished and order restored to a community—stays the same. The monster can be fire in The Towering Inferno, an upturned boat in The Poseidon Adventure, or a boy’s mother in Ordinary People. Though superficially dissimilar, the skeletons of each are identical.

Our hero stumbles into a brave new world. At first he is transfixed by its splendor and glamour, but slowly things become more sinister . . .

It’s Alice in Wonderland, but it’s also The Wizard of Oz, Life on Mars, and Gulliver’s Travels. And if you replace fantastical worlds with worlds that appear fantastical merely to the protagonists, then quickly you see how Brideshead Revisited, Rebecca, The Line of Beauty, and The Third Man all fit the pattern too.

When a community finds itself in peril and learns the solution lies in finding and retrieving an elixir far, far away, a member of the tribe takes it on themselves to undergo the perilous journey into the unknown ...

It’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, Morte D’Arthur, Lord of the Rings, and Watership Down. And if you transplant it from fantasy into something a little more earthbound, it’s Master and Commander, Saving Private Ryan, Guns of Navarone, and Apocalypse Now. If you then change the object of the characters’ quest, you find Rififi, The Usual Suspects, Ocean’s Eleven, Easy Rider, and Thelma & Louise.

So three different tales turn out to have multiple derivatives. Does that mean that when you boil it down there are only three different types of story? No. Beowulf, Alien, and Jaws are ‘monster’ stories—but they’re also about individuals plunged into a new and terrifying world. In classic “quest” stories like Apocalypse Now or Finding Nemo the protagonists encounter both monsters and strange new worlds. Even “Brave New World” stories such as Gulliver’s Travels, Witness, and Legally Blonde fit all three definitions: The characters all have some kind of quest, and all have their own monsters to vanquish too. Though they are superficially different, they all share the same framework and the same story engine: All plunge their characters into a strange new world; all involve a quest to find a way out of it; and in whatever form they choose to take, in every story “monsters” are vanquished. All, at some level, too, have as their goal safety, security, completion, and the importance of home.

But these tenets don’t just appear in films, novels, or indeed TV series like Homeland or The Killing. A 9-year-old child of my friend decided he wanted to tell a story. He didn’t consult anyone about it, he just wrote it down:

A family are looking forward to going on holiday. Mom has to sacrifice the holiday in order to pay the rent. Kids find map buried in garden to treasure hidden in the woods, and decide to go after it. They get in loads of trouble and are chased before they finally find it and go on even better holiday.

Why would a child unconsciously echo a story form that harks back centuries? Why, when writing so spontaneously, would he display knowledge of story structure that echoes so clearly generations of tales that have gone before? Why do we all continue to draw our stories from the very same well? It could be because each successive generation copies from the last, thus allowing a series of conventions to become established. But while that may help explain the ubiquity of the pattern, its sturdy resistance to iconoclasm and the freshness and joy with which it continues to reinvent itself suggest something else is going on.

Storytelling has a shape. It dominates the way all stories are told and can be traced back not just to the Renaissance, but to the very beginnings of the recorded word. It’s a structure that we absorb avidly whether in art-house or airport form and it’s a shape that may be—though we must be careful—a universal archetype.

Most writing on art is by people who are not artists: thus all the misconceptions.

—Eugène Delacroix

The quest to detect a universal story structure is not a new one. From the Prague School and the Russian Formalists of the early 20th century, via Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism to Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots, many have set themselves the task of trying to understand how stories work. In my own field it’s a veritable industry—there are hundreds of books about screenwriting (though almost nothing sensible about television). I’ve read most of them, but the more I read the more two issues nag away:

1. Most of them posit completely different systems, all of which claim to be the sole and only way to write stories. How can they all possibly claim to be right?

2. None of them asks “Why?”

Some of these tomes contain invaluable information; more than a few have worthwhile insights; all of them are keen to tell us how and with great fervor insist that “there must be an inciting incident on page 12,” but none of them explains why this should be. Which, when you think about it, is crazy: If you can’t answer “why,” the “how” is an edifice built on sand. And then, once you attempt to answer it yourself, you start to realize that much of the theory—incisive though some of it is—doesn’t quite add up. Did God decree an inciting incident should occur on page 12, or that there were 12 stages to a hero’s journey? Of course not: They’re constructs. Unless we can find a coherent reason why these shapes exist, then there’s little reason to take these people seriously. They’re snake-oil salesmen, peddling their wares on the frontier.

I’ve been telling stories for almost all my adult life, and I’ve had the extraordinary privilege of working on some of the most popular shows on British television. I’ve created storylines that have reached over 20 million viewers and I’ve been intimately involved with programs that helped redefine the dramatic landscape. I’ve worked, almost uniquely in the industry, on both art-house and populist mainstream programs, loved both equally, and the more I’ve told stories, the more I’ve realized that the underlying pattern of these plots—the ways in which an audience demands certain things—has an extraordinary uniformity.

Eight years ago I started to read everything on storytelling. More importantly I started to interrogate all the writers I’d worked with about how they write. Some embraced the conventions of three-act structure, some refuted it—and some refuted it while not realizing they used it anyway. A few writers swore by four acts, some by five; others claimed that there were no such things as acts at all. Some had conscientiously learned from screenwriting manuals while others decried structural theory as the devil’s spawn. But there was one unifying factor in every good script I read, whether authored by brand new talent or multiple award-winners, and that was that they all shared the same underlying structural traits.

In stories throughout the ages there is one motif that continually recurs—the journey into the woods to find the dark but life-giving secret within.By asking two simple questions—what were these traits; and why did they recur—I unlocked a cupboard crammed full of history. I soon discovered that the three-act paradigm was not an invention of the modern age but an articulation of something much more primal; that modern act structure was a reaction to dwindling audience attention spans and the invention of the curtain. Perhaps more intriguingly, the history of five-act drama took me back to the Romans, via the 19-century French dramatist Eugène Scribe and the German novelist Gustav Freytag to Molière, Shakespeare, and Jonson. I began to understand that, if there really was an archetype, it had to apply not just to screenwriting, but to all narrative structures. One either tells all stories according to a pattern or none at all. If storytelling does have a universal shape, this has to be self-evident.

* * *

When it comes to structure, how much do writers actually need to know? Here’s Guillermo Del Toro on film theory:

You have to liberate people from [it], not give them a corset in which they have to fit their story, their life, their emotions, the way they feel about the world. Our curse is that the film industry is 80 percent run by the half-informed. You have people who have read Joseph Campbell and Robert McKee, and now they’re talking to you about the hero’s journey, and you want to fucking cut off their dick and stuff it in their mouth.

Del Toro echoes the thoughts of many writers and filmmakers; there’s an ingrained belief for many that the study of structure is, implicitly, a betrayal of their genius; it’s where mediocrities seek a substitute muse. Such study can only end in one way. David Hare puts it well: “The audience is bored. It can predict the exhausted UCLA film-school formulae—acts, arcs, and personal journeys—from the moment that they start cranking. It’s angry and insulted by being offered so much Jung-for-Beginners, courtesy of Joseph Campbell. All great work is now outside genre.”

Charlie Kaufman, who has done more than most in Hollywood to push the boundaries of form, goes further: “There’s this inherent screenplay structure that everyone seems to be stuck on, this three-act thing. It doesn’t really interest me. I actually think I’m probably more interested in structure than most people who write screenplays, because I think about it.” But they protest too much. Hare’s study of addiction My Zinc Bed and Kaufman’s screenplay for Being John Malkovich are perfect examples of classic story form. However much they hate it (and their anger I think betrays them), they can’t help but follow a blueprint they profess to detest. Why?

All stories are forged from the same template, writers simply don’t have any choice as to the structure they use; the laws of physics, of logic, and of form dictate they must all follow the very same path.

Is this therefore the magic key to storytelling? Such hubris requires caution—the compulsion to order, to explain, to catalogue, is also the tendency of the train-spotter. In denying the rich variety and extraordinary multi-faceted nature of narrative, one risks becoming no better than Casaubon, the desiccated husk from Middlemarch, who turned his back on life while seeking to explain it. It’s all too tempting to reduce wonder to a scientific formula and unweave the rainbow.

But there are rules. As the creator of The West Wing and The Newsroom, Aaron Sorkin, puts it: “The real rules are the rules of drama, the rules that Aristotle talks about. The fake TV rules are the rules that dumb TV execs will tell you; ‘You can’t do this, you’ve got to do—you need three of these and five of those.’ Those things are silly.” Sorkin expresses what all great artists know—that they need to have an understanding of craft. Every form of artistic composition, like any language, has a grammar, and that grammar, that structure, is not just a construct—it’s the most beautiful and intricate expression of the workings of the human mind.

Did God decree an inciting incident should occur on page 12, or that there were 12 stages to a hero’s journey? Of course not.It’s important to assert that writers don’t need to understand structure. Many of the best have an uncanny ability to access story shape unconsciously, for it lies as much within their minds as it does in a 9-year-old’s.

There’s no doubt that for many those rules help. Friedrich Engels put it pithily: “Freedom is the recognition of necessity.” A piano played without knowledge of time and key soon becomes wearisome to listen to; following the conventions of form didn’t inhibit Beethoven, Mozart, and Shostakovich. Even if you’re going to break rules (and why shouldn’t you?) you have to have a solid grounding in them first. The modernist pioneers—Abstract Impressionists, Cubists, Surrealists, and Futurists—all were masters of figurative painting before they shattered the form. They had to know their restrictions before they could transcend them. As the art critic Robert Hughes observed:

With scarcely an exception, every significant artist of the last hundred years, from Seurat to Matisse, from Picasso to Mondrian, from Beckmann to de Kooning, was drilled (or drilled himself ) in “academic” drawing—the long tussle with the unforgiving and the real motif which, in the end, proved to be the only basis on which the real formal achievements of modernism could be raised. Only in that way was the right radical distortion within a continuous tradition earned, and its results raised above the level of improvisory play ... The philosophical beauty of Mondrian’s squares and grids begins with the empirical beauty of his apple trees.

Cinema and television contain much great work that isn’t structurally orthodox (particularly in Europe), but even then its roots still lie firmly in, and are a reaction to, a universal archetype. As Hughes says, they are a conscious distortion of a continuing tradition. The masters did not abandon the basic tenets of composition; they merely subsumed them into art no longer bound by verisimilitude. All great artists—in music, drama, literature, in art itself—have an understanding of the rules whether that knowledge is conscious or not. “You need the eye, the hand, and the heart,” proclaims the ancient Chinese proverb. “Two won’t do.”

Storytelling is an indispensable human preoccupation, as important to us all—almost—as breathing. From the mythical campfire tale to its explosion in the post-television age, it dominates our lives. It behooves us then to try and understand it. Delacroix countered the fear of knowledge succinctly: “First learn to be a craftsman; it won’t keep you from being a genius.” In stories throughout the ages there is one motif that continually recurs—the journey into the woods to find the dark but life-giving secret within.

This article has been adapted from John Yorke’s book, Into the Woods: A Five-Act Journey Into Story.

December 31, 2015

A Massive Hotel Fire in Dubai

A massive fire engulfed the Address Hotel, a skyscraper in downtown Dubai, on Thursday as the city prepared to ring in the new year. The cause of the blaze, which broke out near the site of planned New Year’s Eve fireworks, was not immediately clear.

Social media reports show flames and smoke billowing from the side of the building facing the Burj Khalifa, the world’s largest building.

#dubai right now pic.twitter.com/7h73ehELhq

— Atieh S (@AtiehS) December 31, 2015

Dubai’s police chief told Agence France-Presse that all of the residents from the hotel had been evacuated. No casualties were immediately reported.

We'll update this story as more information becomes available.

The Carson Campaign's Year-End Collapse

A doctor walks into the examination room and says to his patient, “I have good news and bad news. Which do you want first?”

The doctor is Ben Carson; the patient is his base of support. The good news is that Carson had another great fundraising quarter—hauling in $23 million in the last three months of the year, possibly the best of any Republican, although serious questions remain about the methods he used to raise the funds, and how he has spent them. Campaign manager Barry Bennett confirmed the figure to Politico, and spokesman Doug Watts to The New York Times.

Related Story

Where Is Ben Carson's Money Going?

Now, the bad news: Bennett and Watts both precipitously quit Thursday afternoon. That leaves Carson with a questionable fundraising apparatus, no campaign manager or communications chief, and polling that has been in a steady, inexorable decline since peaking around Halloween, putting Carson in fourth place in the battle for the Republican nomination after running second. Bennett and Watts reportedly resigned over tension with Armstrong Williams, a conservative figure and Carson svengali. Carson’s campaign is in large part Williams’s creation—he cultivated the doctor and convinced him to run for office—but Williams had no formal role on the campaign, and clashed with official aides.

The resignation comes after a tumultuous couple of weeks. First, The Wall Street Journal reported that Carson’s burn rate—the amount of cash his campaign is spending, compared to what it’s bringing in—remains high, even as it takes in huge sums. Carson, under pressure, said he’d shake up his campaign team. Then he changed his mind, telling the Times, “I have 100 percent confidence in my campaign team.” Then he promised to get more aggressive. Then he again hinted at a shakeup.

That was apparently too much for Watts and Bennett. Jennifer Jacobs of the Des Moines Register broke the news:

BREAKING: Doug Watts in statement confirms: "Yes, Barry Bennett and I have resigned from the Carson campaign effective immediately."

— Jennifer Jacobs (@JenniferJJacobs) December 31, 2015

Sources tell me Carson's two top aides quit because of tensions with Armstrong Wiliams, a conservative radio personality advising Carson.

— Jennifer Jacobs (@JenniferJJacobs) December 31, 2015

Things got even weirder:

CHAOS: I am on phone w/ Armstrong Williams as he gets the news. Carson calling him on other phone. "Doctor? Doctor, wait a second. What?"

— Robert Costa (@costareports) December 31, 2015

This isn't the first time staff changes have roiled the Carson campaign. In June, turmoil seemed to imperil his campaign, but that rough patch was followed by his rise in the polls.

To understand Williams’s role in Carson’s rise, it helps to read Jason Zengerle’s sketch of the man. He’s inextricable from Carson, yet he often worked at cross-purposes to the campaign. Take, for example, a damaging story in The New York Times about Carson’s failure to grasp basic elements of foreign policy. The Carson campaign accused the paper of taking advantage of the adviser, Duane Clarridge, “an elderly gentlemen.” But the paper pointedly noted that it was Williams who had referred Clarridge to a reporter. (Williams has not replied to a request for comment.)

The loss of Bennett and Watts doesn’t just come at a terrible time for the Carson campaign—the candidate’s numbers are dropping, and the Iowa caucuses are just 32 days away. It also strips Carson of some of the few advisers he has with real, deep political experience. Watts worked on the Reagan-Bush campaign in 1984. Bennett came to Carson from Senator Rob Portman, the moderate Republican senator from Ohio. He was thought to give real oomph to a campaign badly in need of it—with a staff of inexperienced workers, and a candidate who had a compelling biography and an easy connection with many voters, but no experience in politics or policy to draw on.

One thing to watch is whether the two departures clear the way for a return by Terry Giles, an early Carson confidant and backer who was shunted out of the way during the fall.

Even with Watts and Bennett aboard, Carson was running an unorthodox campaign, viewed by many political sages as hopeless. The campaign wasn’t seeking any endorsements, and relies heavily on small-dollar donations. He hasn’t invested much in TV advertising, either.

“We have a more innovative approach here,” Watts told me in October. “We’re using modern tools that allow us to do things more efficiently .… What they’re talking about is a traditional campaign. It’s only been gone for a couple of years, but it’s long gone. Putting all your money into TV just doesn’t cut it.”

For better or worse, Bennett and Watts’ departures leave in place Carson’s fundraising apparatus, which I noted in October is heavily reliant on pricey telemarketing and direct-mail tactics. The knock on the campaign is that it’s designed to make a lot of money for vendors, many of whom are tied to campaign staffers, and perhaps for Carson. Without experienced operatives atop the effort, donations to the Carson campaign will look like an even worse investment.

The Force Awakens and a Critical Turnaround

As someone who often sees movies more than once, I occasionally have the following experience: I see a film and I’m pleasantly surprised that it’s better than expected; then I see it again, and I’m disappointed that it no longer sustains my upwardly revised expectations. Or the process proceeds in reverse: initial disappointment, followed by a pleasant surprise later on. At least a few times, I’ve had the cycle repeat itself through more than one iteration: disappointment, pleasant surprise, disappointment (or the reverse).

This expectations game poses a particular challenge for people, like me, who write movie reviews. On the one hand, you need to be as clear as you can about how your expectations may have influenced your response to a film. On the other, you need to recognize that the review itself will, at least at the margins, help set viewers’ expectations, for good or for ill. Over-praise and you court backlash; under-praise and you may seem like a wet blanket.

Never have I seen this dynamic more evident than in the response to Star Wars: The Force Awakens—which isn’t surprising, given that it’s the most-anticipated film in recent memory. Since its release two weeks ago, J.J. Abrams’s reboot has seemed to work its way through the expectations game not merely on the level of the individual (myself included), but on the level of vast, cultural consciousness. When the movie first appeared in theaters, the characteristic response by critics was, essentially: Yes, it recycles too much from the initial trilogy—and the original Star Wars in particular—but it so aptly recalls those long-ago delights that this is more a quibble than an existential flaw. (My own version of that case can be found here.)

But over the subsequent two weeks, as the movie has racked up historic box-office numbers, critical sentiment seems to have shifted. The essential components of the assessment remain the same: On the plus side, the film’s performances are strong and pleasingly diverse, it boasts many lively sequences, and the overall result is way better than the second trilogy; on the minus side, the movie is ensnared in its own nostalgia and lack of originality. The balance, however, has shifted from emphasizing the former to emphasizing the latter. Even George Lucas has gotten in on the act, complaining that the movie is all recycled ideas, and that his experience of selling the franchise to Disney was akin to selling his children to “white slavers.” (Which mostly raises the question: Who’s worse? White slavers, or the person who sells his children to them?)

The litany of particulars is by now well documented, and I have no desire to add unnecessary spoilers for anyone who has (somehow) managed so far to avoid them. So briefly: The Force Awakens’s chief protagonist, Rey (Daisy Ridley), is essentially a female version of Luke Skywalker (and a marvelously understated feminist one: read our own Megan Garber on the subject here); its chief antagonist, Kylo Ren (Adam Driver), is a Darth Vader knockoff in more ways than one; Harrison Ford’s Han Solo fulfills pretty much the role this time out that Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi did last time; oedipal issues are once again resolved by means of a light sabre encounter witnessed by young heroes; it ultimately all comes down to an X-Wing assault on the minuscule weakness of an asteroidal, planet-killing super-weapon; etc., etc., etc.

All this has been known and acknowledged from the start. Yet what were once generally considered acceptable flaws are now viewed by some as defining failures. Let me offer a few examples out of the many available. And please be forewarned that this is going to get down into the weeds a bit.

I’ll begin at home, with The Atlantic. I saw The Force Awakens on Tuesday December 15 and wrote my review that day for publication when the embargo broke Wednesday morning. I described the movie as “less sequel than remix,” noted that it was “ensnared in its own nostalgia,” and explained that “much of the enjoyment it provides is by design derivative.” But my complaints were half-hearted at best. Ultimately, for me the movie accomplished two crucial goals: It transported me back to 1977, when I saw Star Wars on opening day as a 10-year-old boy; and it began the task of wiping away all cultural memory of the abominable prequel trilogy. Like most contemporaneous critics, I considered those accomplishments to be more than enough. My thoughts have since evolved somewhat—a second viewing played a significant role—and I’ll return to that evolution in a bit.

The Atlantic’s second bite at the Force Awakens-nostalgia apple was a debate the following Monday between my colleagues Spencer Kornhaber (mostly frustrated: “the lack of originality almost kills the film”) and David Sims (mostly happy: “the notes are familiar—but they’re still well-played”). I don’t know whether either might have written any differently had they done so during in the initial blush of enthusiasm for the movie. But their debate coincided precisely with the moment when the question of how badly The Force Awakens had over-indulged in nostalgia was coming to the fore. And it’s notable how little they actually disagreed on any particulars. Their dispute was almost exclusively a question of the relative weight given to merits and demerits. (Also worth noting is that Spencer, the harsher critic, liked the movie better the second time he saw it.)

Forget about the Force. Nothing in the galaxy is as powerful as expectations.Over the course of the previous week, Vox addressed the nostalgia question on no fewer than four occasions. On December 21, Todd VanDerWerff, in a piece neutrally titled “Five Ways the New Movie Copies the Original Film,” offered a cautiously balanced assessment. Next came a harsher take by Peter Suderman titled “Star Wars: The Force Awakens Is a Prime Example of Hollywood’s Nostalgia Problem.” Ezra Klein then weighed in with a sharply counterintuitive take (“Abrams’s baldfaced rip-off of the original Star Wars is, by far, the most innovative thing about The Force Awakens”). Finally, on December 26, Vox ran a piece by David Roberts titled “Critics Are Going Too Easy on The Force Awakens” that, as its title advertises, went after not merely the film itself but the critics who had oversold it. (Notably, like Spencer, he liked the movie better after a second viewing.)

Finally, the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has written two posts on The Force Awakens. The first, published on December 18 and titled “Requiem for Star Wars,” was notable in part because Douthat had not yet seen the movie and yet was already disappointed (pre-disappointed?) with it. That’s not to say that his critique was inaccurate, but rather that he wasn’t describing the movie itself but rather his already-deflated expectations for it. In his subsequent, post-viewing post, “Star Wars and Decadence,” Douthat confirmed what he had already written, though more ominously: In this self-described “rant,” The Force Awakens had become an object lesson (literally) in the decline of Western civilization. The complaints, again, were precisely the same as those that had been rehearsed many times before by many people; it was the vehemence that was new. Like Roberts in Vox, Douthat was frustrated not merely with the film itself, but with the critics who’d praised it despite its flaws: “This film has a 95 percent ‘Fresh’ rating from critics on Rotten Tomatoes. 95 percent … Decadence, man. Decadence.”

There are many possible responses to Douthat’s critique. One could point out, for instance, that Rotten Tomatoes is a mere up/down rating system, and thus doesn’t screen widely popular masterpieces from widely popular non-masterpieces. (Avatar, which is a genuinely awful movie, got an 83 percent rating.) But The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates made the most straightforward reply of all to Douthat in his post on Saturday:

I think this assessment doesn’t spend enough time considering three very important phrases. Those phrases are: Episode I, Episode II, and Episode III … Now it’s true that Abrams didn’t invent much and he borrowed quite a bit. But … he made something that critics, and fans, have been waiting on for over 30 years—a decent Star Wars film, and arguably the best Star Wars film since The Empire Strikes Back.

Finally, back to my own experience. After my review, I saw The Force Awakens a second time with my family, and I enjoyed the movie dramatically less than I had the first time. The elements that had delighted me initially (Ridley’s Skywalker routine, Driver’s petulant young Vader, Harrison Ford’s undiminished star appeal) delighted me less, and the problems that had bothered me (the many nostalgia-driven errors described above) bothered me more. By the time we got to the X-Wing assault on the DeathStarKiller Base—they couldn’t even come up with a new name for it! Just another variation on “star + death”—the movie had jumped the shark for me as utterly as it had for many others.

So what to take from all this? A few small lessons, I think: First, that with the exception of Ezra Klein’s iconoclastic take, every single writer cited—from me to Douthat to Coates and everyone in-between—agreed, on a nearly molecular level, about what was good about The Force Awakens and what was bad. This is a rare enough thing regarding a movie that is uniformly liked or disliked; for a movie eliciting such wildly different appraisals, it’s borderline astonishing. The varying assessments depended, pretty much in their entirety, on how heavily one weighted the agreed-upon strengths and weakness.

The Force Awakens had become an object lesson (literally) in the decline of Western civilization.Second, that expectations have played an outsized role in how people (or at least those people with online writing outlets) have responded to The Force Awakens. The rush of initial reviews was overwhelmingly positive, even when they cited flaws. But over the subsequent two weeks, those flaws have loomed evermore darkly over the film, in several cases in explicit pushback to the early reviews. Put another way, those of us who didn’t know what to expect from the movie were (for the most part) either pleasantly or joyously surprised; those who had their expectations raised by the reviews were (in some cases) disappointed or even angry about it. It’s noteworthy, too, I think, that those who enjoyed the movie most on first viewing (me, several other critics with whom I’ve spoken) tended to like it less the second time. And those who were initially disappointed (Spencer, David Roberts) often found themselves warming to it on a second viewing.

Eventually, a critical consensus will emerge, as it did with The Phantom Menace and its sequels. But that consensus will almost certainly depend on subsequent installments of the new trilogy: If they break new ground, and send our younger generation of heroes spinning off in novel directions, The Force Awakens will likely be seen as a much-needed reset, one that cleansed the palate of the prequels and rediscovered the cinematic flavor of the original trilogy. If, on the other hand, we again find our heroes lassoing AT-ATs on a snow-covered planet, the darkest predictions of our cultural decline may be vindicated.

Time will tell. But until then, forget about the Force. Nothing in the galaxy is as powerful as expectations.

The Heightened Security for New Year’s Eve Around the World

As people around the world prepare to ring in the new year, their governments and police forces have increased security measures at celebrations and gatherings or canceled them altogether amid fears of terrorist attacks.

The heightened holiday security comes after deadly assaults in Paris and San Bernardino in recent months, and after authorities in Belgium, Turkey, and the United States this week arrested people who were believed to be planning to carry out attacks during New Year celebrations in highly populated areas.

In Paris, the site of terrorist attacks claimed by the Islamic State that killed 130 people in November, officials called off an annual fireworks display on the Champs-Élysées, according to The Guardian. About 11,000 police, soldiers, and firefighters will patrol Paris, part of a total of 60,000 law-enforcement officers dispatched throughout the country Thursday night.

In Brussels, Belgian officials decided to cancel New Year fireworks and festivities, which drew about 100,000 people last year, “given information we have received,” said Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel Wednesday. The capital spent several days at the country’s highest terror alert level in November as police scoured neighborhoods for potential suspects in the Paris attacks.

In London, Scotland Yard dispatched about 3,000 officers to patrol the city as it rings in the New Year. In Moscow, Red Square, where revelers traditionally gather before midnight, was shut down. In New York City, about 6,000 police officers will be deployed—between 600 and 800 more than usual for New Year festivities—according to the police commissioner.

In Berlin, police presence is at its largest for New Year celebrations, according to Deutsche Welle. In Madrid, officials have for the first time imposed limits on the number of people allowed to attend celebrations on Puerta del Sol square, where thousands of people usually gather, and police will be patting down attendees and searching bags, according to El País. In Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, police banned outdoor parties after 8 p.m. Thursday night.

Vienna police said Saturday that it had received a warning from an unnamed, “friendly” intelligence service that terrorist attacks were possible in the days between Christmas and New Year’s Eve in multiple European cities, but did not name which had been mentioned. Police said they will conduct more thorough security checks in the Austrian capital, but celebrations will go on as planned.

On Thursday, New York police arrested an alleged supporter of the Islamic State who was believed to be planning to attack a bar in Rochester Thursday night.

The Ankara prosecutor’s office said Wednesday police detained two men, both Turkish nationals, who had allegedly planned to strike at the Ankara’s main square, where people are expected to gather to celebrate the New Year, and two locations near Kizilay, a shopping and restaurant district in the city’s center.

Earlier this week, Belgian police detained six people in raids that were believed to be plotting attacks on “symbolic places” during New Year celebrations in Brussels.

The War Over the War on Crime

The Disraeli and Gladstone of American policing are at it again. There’s Bill Bratton, the commissioner of the New York Police Department, currently in his second stint as the city’s top cop, and crowing over a decline in crime in 2015. And then there’s Ray Kelly, the man who Bratton has twice replaced at 1 Police Plaza, casting doubt on Bratton’s accomplishments. As debates over the the role of law enforcement in America go, this may not be the most consequential, but it is among the most heated and personal.

The current flare-up in the rivalry came in the last weeks of the year, after the city released year-end figures showing a 2 percent drop in crime, measured (per FBI guidelines) through several key categories of infractions. While murders rose a smidgen—rising from 333 in 2014, to 339 as of December 20 of the current year—it was still one of the lowest totals in memory. That all came with a 13-percent drop in the number of arrests in the city. All in all, they were numbers that Bratton could be proud of, and he didn’t hesitate to say so. “As we end this year, the City of New York will record the safest year in its history, its modern history, as it relates to crime,” he said.

Kelly wasn’t buying it. “I think you have to take a look at those numbers … because I think there is some issues with the numbers that are being put out,” he said on a radio show. He suggested that the NYPD had changed its criteria in order to juke the numbers—not counting graze-wounds from bullets, for example.

Bratton denied that any changes had been made. “Those comments were outrageous,” he said Tuesday. “My cops work ... very hard to reduce gun violence in the city. To claim in some fashion that we’re playing with the numbers? Shame on him …. If you’re gonna make [that allegation], stand up, be a big man and explain what you’re talking about.” Deputy Commissioner Dermot Shea, who heads up statistics for the department, said Kelly was wrong, noting he had worked for the former commissioner, and the department released a fact-sheet with more detailed rebuttals to Kelly’s claims.

Newseum

Newseum Kelly was undeterred: “It reveals an administration willing to distort the reality of what [cops] face on the street,” he said. The Daily News put the feud on Wednesday’s front page, with the headline “MACHINE GUN KELLY.”

What’s behind Kelly’s fusillade? Bratton had one suggestion, accusing his predecessor of talking trash in order to sell copies of his new book. “It’s amazing the comments you’ll make when you're selling a book,” he remarked—to which Kelly tartly replied, “I appreciate the promotion for my book. I mean, it’s nice of him.” Another idea comes from the New York Post, which promoted Kelly’s critique and has also promoted the idea that he would run against Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2017.

But the feud between New York’s two most-famed commissioners since Teddy Roosevelt seems to be in large about their respective legacies, and about how best to conduct police work. It’s a fascinating battle that cuts across decades and political parties.

Bratton returned to the department at the behest of de Blasio, a Democrat who had campaigned on reducing excessive, racially targeted use of stop-and-frisk techniques under Mayor Michael Bloomberg (a Republican-turned-Independent) and Kelly, who led the department throughout his tenure. When de Blasio appointed Bratton—a triumphant return for a man who’d been forced out of the gig after clashing with Mayor Rudy Giuliani—the commissioner immediately focused on reducing the number of police stops.

“The No. 1 issue we heard over and over again was that the black community—rich, poor, middle class—was concerned about this issue,” Bratton told The New Yorker’s Ken Auletta. “The commissioner, whom they liked quite a bit, and Mayor Bloomberg, who polled well for a long time, just weren’t listening. They were kind of tone-deaf to this issue. So we worked really hard, myself and Mayor de Blasio, to respond.”

Kelly didn’t like that, telling Auletta, “He ran an anti-police campaign. He parsed the electorate. He did it very skillfully. He aimed at the fringes.” The two men have engaged in an on-and-off war of words over the last two years.

The stakes are clear enough: Bloomberg and Kelly argued that the stop-and-frisks were essential to driving down the crime rate. De Blasio and Bratton argued that they were antagonistic to people of color and pointless besides. If the crime rate continues to drop even as the arrest rate drops, too, it risks making Kelly look hamhanded. The Harvard-credentialed cop takes pride in his image as a modern, smart, innovative commissioner, and that undermines his reputation. Worse, he risks looking racially divisive at best, and racist at worst, if he turns out to have been pursuing antagonistic tactics that didn’t make a difference. Thus Kelly has a vested interest in questioning the validity of the crime drop.

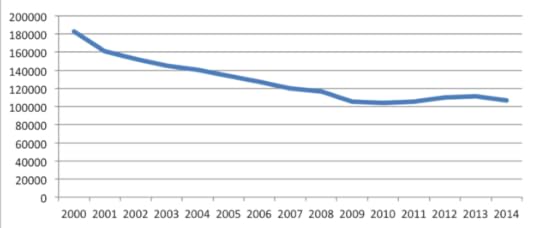

There’s also a legacy question. Kelly no doubt feels that the work he did for 12 years running the department went a long way toward producing the low levels of crime that Bratton is enjoying today. Certainly it’s true that the crime rate in the city dropped during Kelly’s second tenure, despite a small bump at the end:

Violent Crime in New York City

This must feel like deja vu for Kelly. During his first term as commissioner, under Democratic Mayor David Dinkins, crime in the city also dropped. Then Dinkins lost to Republican Giuliani, who brought Bratton in from Boston to replace Kelly. Geoffrey Gray reported in New York in 2010:

During the transition, Kelly attempted to dismantle his brain trust, sources say. “He wanted literally no institutional memory, a blank slate,” says a former aide from this period. “He wanted Bratton to fall on his ass.”

It didn’t work. “Bratton was innovative, flashy, and spectacularly successful at crime reduction,” William Finnegan wrote in The New Yorker in 2005. “His achievement eclipsed Kelly’s in the public’s memory.” He aggressively employed “broken-windows” policing, a style based on a 1982 Atlantic story that emphasizes the importance of going after minor crimes.

After years in various jobs—private-sector work, the federal government, Interpol—Kelly had another shot. Under Bloomberg, he oversaw yet another drop in crime, as New York lost the last vestiges of its reputation as a gritty, dangerous city and became mostly a glitzy palace of finance. Kelly, meanwhile, presented himself as a bold, innovative cop who was retooling the city’s force for the 21st century, a department that could fight both petty crime and terrorism. New York’s Chris Smith wrote in 2012, “Whenever Kelly leaves One Police Plaza—most likely in January 2014, when a newly elected mayor replaces Michael Bloomberg—he will be rightly celebrated as the greatest police commissioner in the city’s history.” Yet Smith’s story came in the context of police starting to turn on Kelly.

And now here’s Bratton again, swooping in and delivering record-setting numbers, and again threatening to eclipse Kelly’s legacy.

There are several ironies here. One is that Bratton is himself trying to outrun his legacy. Broken-windows policing has widely been seen as synonymous with stop-and-frisk, which complicates Bratton’s own efforts now:

Bratton is at pains to emphasize that broken-windows policing is not stop-and-frisk. With stop-and-frisk, he said, “an officer has a reasonable suspicion that a crime is committed, is about to be committed, or has been committed. Quality-of-life policing is based on probable cause—an officer has witnessed a crime personally, or has a witness to the crime. It’s far different.” The difference is irrelevant to many critics, who see an approach that presumes guilt and unfairly targets minorities.

Moreover, the steady drops in New York may owe something to the leadership of Kelly and Bratton, but other commissioners might have been similarly successful. Crime is decreasing around the country, a historic decades-long drop, and one not easily attributed to any single cause.

Finally, as Andy Cush pointed out, it’s a bit rich for either Kelly or Bratton to be lobbing accusations of statistical manipulations anywhere. Kelly might point out that during Bratton’s tenure at the Los Angeles Police Department, the city underreported the crime rate, according to the Los Angeles Times. But as Andy Cush notes, that would take some serious chutzpah—since Kelly’s NYPD was also forced to settle lawsuits over juking the numbers. There may be honor among thieves, but you can’t put as much faith in the people paid to count them.

Female Characters Don't Have to Be Likable

Shortly after Jill Alexander Essbaum’s novel Hausfrau was published in the spring, the New York Times book critic Janet Maslin dismissed the novel on the basis of the main female character being an “insufferable American narcissist.” The story, a modern Anna Karenina-Madame Bovary hybrid set in a suburb of Zürich, features a compulsively unfaithful housewife named Anna. While Maslin wasn’t a fan of Essbaum’s writing (which she compared to “a sink full of dishwater”), her criticism lingered on Anna’s unsavory traits. “This may be hard to believe, but Anna becomes even more myopic and selfish in the book’s later stages,” Maslin wrote. “[Anna’s husband] becomes more interesting, she grows less so, and still she snivels at center stage, whining about her bad luck and mistreatment.”

Yet in 2015 the publishing industry saw a bevy of novels, written by women, that feature ill-natured, brilliantly flawed female protagonists in the vein of Amy Dunne from 2012’s Gone Girl. And the reaction from readers and critics suggested that this unlikability was hardly a turnoff. The narrator of Paula Hawkins’s The Girl on the Train is a newly divorced woman who’s irrationally jealous of a stranger. The novel became a number one New York Times bestseller within a month of its release and its movie rights were quickly snapped up. Another instant bestseller, Jessica Knoll’s debut novel Luckiest Girl Alive, centers around Ani FaNelli, an unapologetic social climber. After Birth, the raw and celebrated account of motherhood by Elisa Albert, is driven by a slightly different Ani who’s conflicted about her new role as a parent. And Fates and Furies, a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award, ultimately reveals that the seemingly selfless Mathilde has long been raging behind the scenes of her own multi-decade marriage. Meanwhile, Hausfrau, insufferable narcissist and all, was named an Amazon Best Book of the Month in March.

These ladies scheme, swear, rage, transgress, deviate from convention—and best of all, they seldom genuinely apologize for it. It’s the literary equivalent of the feminist catchphrase originated by Amy Poehler: “I don’t fucking care if you like it.” More than being “unlikable,” these female characters directly challenge the institutions and practices frequently used to measure a woman’s value: marriage, motherhood, divorce, and career. They defy likability in their outlandish occupation of the roles to which women are customarily relegated—mother, wife, daughter—resisting sexist mythologies and social pressures. Perhaps most refreshingly, these novels aren’t so much heralding a new age of female-centric literature as they’re building on a much older English-language tradition of works about complex women.

For one, these novels allow their protagonists to navigate vulnerability, pain, and disappointment—and all the awful thoughts and behaviors that may arise. In After Birth, Ani adjusts to the toll motherhood can take on one’s relationships and psyche, dispelling the myth of delirious happiness emblematized by modern baby showers. While Hausfrau’s Anna loves her children, being a stay-at-home mother and the comfortable wife of a banker isn’t enough to cure her profound unhappiness. And Girl on the Train’s 32-year-old Rachel Watson simply gets to be a spiteful complicated mess: an addict who loses her job and routinely lies to her roommate.

These ladies scheme, swear, deviate from convention—and, best of all, they seldom apologize for it.Luckiest Girl Alive’s Ani FaNelli is acutely aware of the ridiculous expectations placed on her as a woman, but she’s willing to play the game anyway to get ahead: from extreme dieting to picking the “right” man to marry to improve her social status. Fates and Furies cleverly splits its narrative in two to show how two people in the same marriage can have grossly distorted views of their relationship: In the first part, told from the husband’s perspective, Mathilde is an angel who puts his career before her own, while the second part reveals Mathilde’s darker, more violent side. The end result in all these cases is a fairly uncommon one in literature: sympathy for a woman who has done terrible things.

Heightening the complexity of these novels is that their narrators and characters fall on a spectrum of unreliability—characters whose recounting of events, plots, and details might, or it is later revealed, be entirely inaccurate. There’s a certain appeal, as a reader, in being kept guessing or intentionally deceived by a character’s tenuous relationship with reality.

It’s worth noting that all of these transgressive fictional women are white and come from a very specific socioeconomic background. Still, what Hausfrau, Girl on the Train, After Birth, and Luckiest Girl Alive have in common with 2012’s Gone Girl is their attempts to examine and complicate their own version of white suburbia and upper-class normativity. Each protagonist toys with the notion of having “made it” (or conversely having lost it) in primarily upper-middle-class worlds with the traditional markers of house, spouse, children, and career.

The publishing industry remains regressive in many ways when it comes to embracing complex female characters. Earlier this year, after analyzing the last 15 years’ worth of winners of six major literary awards, the author Nicola Griffith determined that books about women are considerably less likely to win prestigious awards. Of her findings, she ultimately concluded that “the more prestigious, influential, and financially remunerative the [literary] award, the less likely the winner is to write about grown women. Either this means that women writers are self-censoring, or those who judge literary worthiness find women frightening, [or] distasteful.”

Which makes the very act of creating an unlikable female protagonist feel that much more meaningful. In 2012, Publisher’s Weekly interviewed Claire Messud about the angry, middle-aged lead character of her novel The Woman Upstairs, asking her, “I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you? Her outlook is almost unbearably grim.” Messud replied:

For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with Mickey Sabbath? Saleem Sinai? Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? Oscar Wao? Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in Infinite Jest? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities.

The construct of female likability may continue to influence which books earn the highest praise, but fiction has served up memorable examples of female characters known for their general lack of regard for “niceness.” Anna Karenina was unfaithful to her husband, left him and her son, and took up with a count who ultimately left her for an 18-year-old. Madame Bovary was no better: Even after “marrying up” from her humble farm origins and becoming a doctor’s wife, Emma found elegant balls and outings to the opera so boring that she had an affair with a landowner. (Motherhood turned out to be a total bore too.)

Meanwhile, Becky Sharp of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair is just about the biggest female opportunist English literature has ever seen, seducing wealthy men to advance her social status. In Pride and Prejudice, the witty and designing Elizabeth Bennet is clearly the enduring favorite over her saintly older sister, Jane, remembered for, yes, her niceness and beauty. In Little Women, the ambitious younger sister Jo March, who’s uninterested in marriage and (selfishly) wants a literary career, feels like the true main character.

The major difference is, of course, that many of these unlikable ladies were written by men. Today, much remains to be done to achieve anything close to gender parity in the literary world, with women far outnumbering men as book-buyers, but with men still dominating criticism. And yet authors like Essbaum and Hawkins are helping to fix things by giving life to protagonists who challenge the gendered boundaries of morality and normalcy. If enough writers do the same, literature might arrive at a day where book critics treat an angry, selfish, but ultimately compelling female character the way they would Hamlet or Oscar Wao—not as a deterrent but as an invitation to keep reading.

Remembered: A Few Notable Deaths of 2015

Laszlo Balogh / Reuters

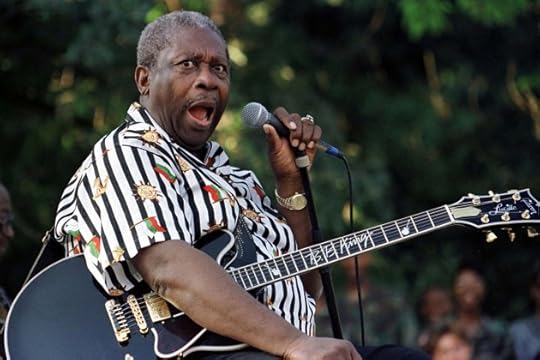

Laszlo Balogh / Reuters The life of B.B. King (b. 1925) is proof that to play the blues, it helps to have lived the blues. The son of a Mississippi sharecropper, King played his way out of the cotton fields to become one of the most popular and influential blues musicians of his day. King’s plaintive vocals and achingly expressive guitar licks—often played on a jet-black hollow-bodied Gibson guitar he named “Lucille”—gave him a signature sound that won him a worldwide following, 15 Grammy Awards, and the respect of legions of guitarists, including Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, and Keith Richards. King was a tireless ambassador of the blues, playing more than 200 gigs a year, even well into his 70s. B.B. made it all look easy, but as King once put it, “The blues are a mystery, and mysteries are never as simple as they look.”

Seth Wenig / Reuters

Seth Wenig / Reuters Albert Maysles (b. 1926), along with his younger brother David, pioneered a fly-on-the-wall style of documentary filmmaking that came to be known as “direct cinema.” Maysles would spend an inordinate amount of time simply observing his subjects, letting the story unfold organically rather than drawing up detailed plans about what to shoot. In Salesman (1969), Maysles documented the quiet desperation of traveling Bible salesmen; in Gimme Shelter (1970), he captured a fatal stabbing during the Rolling Stones’s Altamont concert; in Grey Gardens (1975), he detailed the curious lives of an upper class recluse and her daughter living in a crumbling Long Island estate. The subjects of Albert Maysles’s documentaries acted as though they were completely unaware that they were being filmed, which was part of Maysles’s genius.

University of Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment / Flickr

University of Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment / Flickr Grace Lee Boggs (b. 1915) learned early in life that if she wanted justice, she’d have to fight for it. Born to Chinese parents, Boggs received a Ph.D in philosophy from Bryn Mawr College in 1940, but was unable to land a job in academia as a woman and a minority. The early rejection led Boggs to a lifetime of dedication to the civil rights, labor, and Black Power movements. She worked as an organizer for tenants’ and workers’ rights, and authored books and articles on social justice and political philosophy. She was a fierce critic of the social and economic conditions that contributed to Detroit’s decline, and how the heaviest burden fell on the city’s underclass. Boggs and her husband founded Detroit Summer, a community projects program for youth to revitalize city neighborhoods, as well as the James and Grace Lee Boggs Center to Nurture Community Leadership. Her work lives on.

Richard Shotwell / Invision / AP

Richard Shotwell / Invision / AP Long before transgender actresses landed breakout roles in shows such as Orange Is the New Black and Hung, there was Holly Woodlawn (b. 1946). Born Haroldo Danhakl in Puerto Rico, she changed her name to Holly (after Audrey Hepburn’s character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s) and hitchhiked from Miami to New York City, a transformational journey later immortalized in the opening lines of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.” She was discovered by Andy Warhol and soon won critical acclaim for lead roles in Trash and Women in Revolt. Woodlawn never achieved blockbuster success, but lived to see the day when millions of viewers embraced nuanced transgender characters. Last year, Woodlawn appeared in two episodes of the acclaimed Amazon series Transparent.

Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

Jonathan Ernst / Reuters If Julian Bond (b. 1940) had been born a few decades later, he might have had a shot at being the nation’s first African American president. As it turned out, the civil-rights activist, longtime NAACP chair, and man President Obama called “a hero and friend” was too far ahead of his time. While a student at Morehouse College, he helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a group that would be on the front lines of protests that led to the nation’s landmark civil-rights laws. Bond served in the Georgia Legislature for more than two decades, and his name was placed into nomination as vice president at the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention. Bond became a widely respected activist and administrator, helping to turn around the NAACP at a time when the organization was mired in debt and criticized as being out of touch. In his later years, Bond was an ardent supporter of LGBT rights—characteristically about a decade before such a position gained mainstream acceptance.

Scott Audette / Reuters

Scott Audette / Reuters Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra (b. 1925) was one of baseball’s all-time greats, but his more enduring contribution may turn out to be to the English language. As a player, Berra had few rivals. Over a nearly two-decade long career as catcher for the New York Yankees, he was a perennial All Star and three-time winner of the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award—the best player on the best team in baseball. But Berra’s longest-lasting legacy may be his improbable Yogi-isms, which include, “It’s like déjà vu all over again,” “When you come to a fork in the road, take it,” and, “Baseball is 90 percent mental and the other half is physical.” Berra was characteristically modest about his contributions to the language, saying simply, “I really didn’t say everything I said.”

Lucas Jackson / Reuters

Lucas Jackson / Reuters When it came to music, Allen Toussaint (b. 1938) could do it all. The legendary New Orleans musician wrote songs that became hits for an astonishing variety of artists, ranging from the Pointer Sisters and Irma Thomas to Glen Campbell and Devo. He was also an accomplished pianist, singer, arranger, and producer, and his New Orleans recording studio attracted musicians from around the world who sought to capture the New Orleans sound. But Toussaint’s lasting legacy may be that he kept the Big Easy’s swampy R&B traditions alive for successive generations of artists to reinterpret. Toussaint remained fiercely loyal to New Orleans, even after Hurricane Katrina ravaged his home and studio in 2005. He teamed with Elvis Costello on the first major recording session to take place after the disaster, producing the critically acclaimed album The River in Reverse.

AP

AP The folk singer Jean Ritchie (b.1922) brought the sounds of her native Appalachia to a worldwide audience, and in the process, saved dozens of traditional songs that might otherwise have been lost to history. The youngest of 14 children born to a family of balladeers from eastern Kentucky, Ritchie moved to New York City in 1947, and met up with the folklorist Alan Lomax, who recorded her for the Library of Congress. Ritchie sang in a ringing crystalline voice, and also introduced audiences to the mountain dulcimer and autoharp. Ritchie became a fixture in the emerging folk music scene of the late ’50s and early ’60s, helped launch the first Newport Folk Festival, and counted Bob Dylan and Joan Baez as admirers. Ritchie became a collector of traditional folk songs and a respected authority on their origins, ensuring that even after her death, the music would survive.

Alessandro Garofalo / Reuters

Alessandro Garofalo / Reuters Chantal Akerman (b. 1950) wasn’t a household name in film, but few directors have been as influential as the Belgian-born auteur. Many of Akerman’s films examined the inner lives of women, and her originality and wide-ranging cinematic vision brought comparisons to Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard. Akerman’s reputation was made by her 1975 feature, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai de Commerce—1800 Bruxelles, a transgressive look at a widow who goes about the banal routines of daily life while supporting herself as a sex worker. Akerman, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, struggled with—and in many ways chronicled—depression. Her final film, No Home Movie, examines the waning days of her mother, who survived Auschwitz and died in 2014.

Susana Vera / Reuters

Susana Vera / Reuters Like every great novelist, Gunter Grass (b. 1927) knew how to write a surprise ending. For nearly half a century, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist was a voice of moral outrage in postwar Germany, beginning with The Tin Drum, Grass’s first novel, and among his best known. Many of Grass’s novels, plays, and essays dealt with Germany struggling to come to terms with its dark past, full of “rubble and cadavers,” as Grass once put it. An outspoken socialist, Grass was active in politics, and drew widespread criticism for opposing Germany’s reunification in 1990. The surprise ending to Grass’s life story was revealed in 2006, when the author stunned Germany by admitting that during the last months of World War II, he had been a member of Hitler’s Waffen SS, the combat arm of the notorious organization that orchestrated the Holocaust.

Back when I felt like me. #tbt

A photo posted by Lisa Bonchek Adams (@adamslisa) on Dec 11, 2014 at 9:26am PST

By describing what it was like to die, Lisa Bonchek Adams (b. 1969) taught many how to live. Adams, a mother of three from Connecticut, was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 2006 when she was 37 years old. Six years later, she learned that her cancer had metastasized. Adams chronicled it all in excruciating detail on her blog, lisabadams.com, her Facebook page, and on Twitter, where she posted more than 176,000 tweets. Some were unnerved by Adams’s willingness to make her battle so public; a controversial article in The Guardian questioned the propriety of turning a life-and-death struggle into a social-media phenomenon. But Adams’s many followers had no such qualms, touched by the raw honesty of her writing—to the end, a compelling blend of courage, fear, despair, and hope.

AP

AP The British-born lawmaker, social activist, and corruption fighter Elsie Tu (b. 1913) was the conscience of Hong Kong in an era of fading and indifferent colonial rule. Dubbed “the spirit of Hong Kong” for championing the rights of the underclass, she came to the then-British colony on missionary work in 1951 and entered local politics, representing one of Hong Kong’s first opposition groups. Tu will be remembered for her fight against systematic corruption in Hong Kong, particularly in the police force. Her efforts led to the establishment of an independent commission against corruption and to more critical scrutiny of British rule. In her later years, Tu was criticized for being pro-Beijing, and had a ready answer: “I’m not for China, I’m not for Britain. I’ve always been for the people of Hong Kong and for justice.”

December 30, 2015

In Defense of Food and the Rise of ‘Healthy-ish’

Abstinence, we are usually told around this time of year, makes the heart grow stronger. It’s why Dry January, which started in the green and pleasantly alcoholic land of Britain a few years ago before reaching the U.S., is increasingly being touted as a good and worthy thing to do, and why so many people are currently making plans to remove whole food groups from their diet: carbs, fat, Terry’s Chocolate Oranges. The key to health, books and websites and dietitians and former presidents reveal, is a process of elimination. It’s going without. It’s getting through the darkest, coldest month of the year without so much as a snifter of antioxidant-rich Cabernet.

The problem with giving things up, though, is that inevitably it creates a void in one’s diet that only Reese’s pieces and a family-sized wheel of brie can fill. Then there’s the fact that so many abstinence-espousing programs require spending money on things; on Whole 30 cookbooks and Weight Watchers memberships and $10 bottles of bone broth. For a process that supposedly involves cutting things out, there seems to be an awful lot to take in.

This, Michael Pollan posits, is the problem with food: It’s gotten extraordinarily complicated. The writer and sustainable-eating advocate has written several books on how the simple business of eating has become a minefield in which earnest Westerners try to tiptoe around gooey, genetically engineered sugar bombs without setting off an explosion of calories, corn sugar, and cancer. In Defense of Food, published in 2008, offers a “manifesto” for eaters (i.e. humans) that’s breathtaking in its seven-word simplicity: Eat Food. Not Too Much. Mostly Plants. This mantra is repeated once more in a documentary based on the book that airs Wednesday night on PBS, and it’s felt in the January issue of Bon Appetit, which is based almost entirely around the concept of “healthy-ish” eating: “delicious, comforting home cooking that just happens to be kinda good for you.”

Healthy-ish, as a concept, isn’t new. In fact, it’s the food industry’s equivalent of your mom telling you to finish your broccoli before you dive into the Twinkies, only dressed up with a sexy hyphenated coverline and some mouthwatering photos of chicken seared in a cast-iron skillet. “Healthy-ish” shouldn’t feel revolutionary. By its very definition it’s something of a big old foodie shrug—an acknowledgment that if we can’t all subsist on steamed fish and vegetables all of the time, we can at least offset the steak dinner for having salad for lunch. It is, as per Pollan at least, a philosophy that everything is best enjoyed in moderation, including moderation.

So why does it feel so subversive?

The reason, as explained by both manifestations of In Defense of Food, is that industries upon industries, even entire religions, have been predicated on the premise that eating (certain things) is bad and will kill you. The documentary draws on years of food-related quackery to illustrate how ingrained fearing food is. It looks back to John Harvey Kellogg’s sanitariums in the late 19th century, in which the renowned Seventh Day Adventist, convinced that protein was bad for you and that constipation was caused by a buildup of bacteria in the colon, gave prescriptions for yogurt enemas, all-grape diets, and chewing each bite of food 20 times before you swallow.

Kellogg is better-known now as the pioneer behind breakfast cereal, which he believed would help rid the world of the evil that is masturbation, but his experiments with fad diets have informed much of the thinking behind modern “healthy” eating regimes in the ways in which they take things to extremes. Paleo diets, although structured around an excess of protein that Kellogg would faint at, are based on the premise that humans haven’t yet evolved to eat grains, legumes, and dairy (the British Dietetic Association counters that they’re “a sure-fire way to develop nutrient deficiencies”). Veganism, by contrast, is touted by the Physician’s Committee for Responsible Medicine as “the optimal way to meet your nutritional needs” (this may well be true, but it’s also the optimal way to get disinvited from a dinner party). Both involve intensive planning and work. Neither allows any leeway for an 11 a.m. office Krispy Kreme.

“Healthy-ish” is a philosophy that everything is best enjoyed in moderation, including moderation.What’s so compelling about Pollan’s manifesto, by contrast, is that he obviously loves food, and not in a gets-orgiastic-over-fiber kind of way. Although the documentary is less nuanced and richly drawn than his writing, it communicates much of the passion he feels for simple pleasures like a crunchy, well-dressed salad, or a zesty hunk of warm sourdough bread. In a modern nutritional environment that still can’t decide whether protein is an important building block for human growth or a source of cancer-causing chemicals, there’s something comforting about seeing such a calming soul navigate his way between a golden rotisserie chicken and a buffalo wing, engineered in every way to tickle the relevant taste buds (sweet, salty, fatty, twice-fried).

What’s implicitly communicated by In Defense of Food, and wholly preached by Bon Appetit, is that the key to all this starts at home with the simple act of cooking. “If it came from a plant, eat it,” Pollan says. “If it was made in a plant, don’t.” The reason for this is that unlike large-scale food purveyors, humans are entirely less likely to put things like sodium stearoyl lactylate and soy lecithin in the meals they prepare at home. If you’re cooking dinner, chances are you’re baking potatoes rather than tossing them in a deep fryer, and steaming vegetables instead of dousing them in butter and salt.

“We’re not ascetic,” writes Bon Appetit’s editor, Adam Rapoport, in his January letter to readers. “Instead we think about what we eat, and when and why we eat it. We indulge when the situation arises ... and we try to eat smart other times.” It’s a food philosophy that’s sensible, moderate, conservative, and sound, none of which are particularly sexy qualities when you’re searching for a quick fix to atone for the sins of holiday overindulgence. But unlike going low-carb or alcohol-free, or (shudder) for a yogurt enema, eating healthy-ish is something most people can bear, even long after January rolls out.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower