Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 272

December 17, 2015

The Case for Hamilton as Album of the Year

Hamilton initially began as “The Hamilton Mixtape,” a collection of songs about the man whom Lin-Manuel Miranda memorably christened the “10-dollar founding father without a father” at the White House in 2009. It then blossomed into a hugely successful Broadway musical, of course. But it’s worth remembering that the cultural phenomenon—the costumes and dancing, the sidewalk show, the memes, the late-night appearances, the celebrity endorsements, the Democratic fundraiser—started out as music.

And as music is how the majority of its fans are going to experience it, even if at some point tickets aren’t selling out months in advance at $300 apiece. The entire play happens in song, captured in a two-disc recording executive-produced by The Roots that quickly became the best-selling cast album in Nielsen history. A far smaller achievement is that it’s my favorite album of the year, and I’m one of the many people whose experience of the show has been limited to Spotify listens.

One of the biggest talking points about Hamilton is about how crazy, seemingly incongruous, it is for the tale of the guy who founded America’s banking system to be told through hip-hop. Creator and star Lin-Manuel Miranda has a stock reply: “It’s a hip-hop story.” That’s both because of the way that Alexander Hamilton created a verbally dense record over the course of his lifetime, and the way that he came from poor beginnings to challenge the status quo with plenty of boasting along the way.

You can find this Hamiltonian idea of hip-hop refracted through rap’s other great works this year. You hear it in the verbosity, the craft, the daringness, the desperate idealism, and the death-obsessed drive of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly. You hear Hamilton’s obsession with legacy, his unwillingness to back down when challenged, his profligacy—“why do you write as if you’re running out of time?”—in Drake’s multi-mixtape 2015 output. Musically, you hear the same sort of gleeful omnivorousness that Miranda practices—the belief that all sounds can be hip-hop if presented in the right spirit—in the grinning jazz of Donnie Trumpet & the Social Experiment’s Surf and the psychedelic swirl of A$AP Rocky’s LifeLongA$AP. In turn, all of these albums reflect essential features of Broadway musicals. Each tells a sustained story over multiple songs—even if in some cases it’s just an overarching story about the rapper himself—and they all refer back to themselves constantly, reprising lines and themes and sounds.

What you don’t hear elsewhere is quite the same style of rapping as on Hamilton. A lot of the rave reviews for the show have a line dismissing the idea that there’s something inherently embarrassing about guys in powdered wigs using Mobb Deep lines to talk about the Election of 1800 for Times Square tourists. “Schoolhouse Rock” comes up a lot, as an example of what this show isn’t. I actually wouldn’t venture that argument; on some level, Hamilton must be acknowledged as hokey. Its actors crisply enunciate each word, reflecting not how people actually talk nor the most cutting-edge rap cadences, but rather the need to be immediately understood by people at the back of the Richard Rodgers Theater. “For me, it’s like when you watch a sitcom from the '70s and everyone’s overacting—dramatic and loud—because they were doing it in front of a live studio audience,” Taleb Kweli said in an interview with Vulture in which he otherwise praised Hamilton. There’s also the fact of Miranda’s writing itself: self-consciously “smart,” multisyllabic, meant to show off the characters’ braininess.

All of this creates a sense of labor, of artifice. Listening to a rapper like Future, you feel like he’s transmitting directly from his brain. Listening to Hamilton, you hear writing. You hear work. Miranda said he spent a full year working on “My Shot,” and I believe it; it probably took a month alone to figure out the right phrase to rhyme with “revolutionary manumission abolitionists.” And work, according to a common cultural attitude, is not cool. People want their artists to appear effortless—recent buzzword: “sprezzatura”—or for them to virtuosically act on sudden bursts of inspiration. When the labor is visible, it’s often exalted only if it’s the service of some abstract muse. The sonic soup of To Pimp a Butterfly clearly took a lot of man hours to create, but they were spent in order to illustrate the jagged contours of Lamar’s own mind. It’s part of that album’s sales pitch that it doesn’t care about sales.

But Hamilton wants to do everything: entertain, inform, be the biggest thing on the planet. The fact that it succeeds, I would argue, justifies its intrinsic dorkiness. After all, the show itself is a monument to overachievement and old-fashioned ambition. The answer to the opening question—“How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor grow up to be a hero and a scholar?”—is, basically “relentless labor.” The American Dream in platonic form, no? The narrator Aaron Burr may be just as brilliant as Hamilton, but he’s reserved, cool, waiting for the right moment to make a move. Hamilton makes moves constantly and proclaims his ambitions openly, and that’s why he’s the hero—he’s breaking with decorum to achieve something great.

Hamilton’s music follows its main character’s lead, trying hard to max out on both quantity and quality. You don’t just happen into songs with hooks this gemlike, intertwining elements this complex, or arrangements that so perfectly strike the magic balance of familiarity and novelty. Nor is there any accident to the fact that the diversity of sounds here makes it so you never feel lost within the two-and-a-half hours of the production. Each and every line has been carefully sculpted so that you can hear new bits of cleverness in them each time you listen. And, perhaps most importantly, the emotional machinery just works, giving an authentic thrill at the Battle of Yorktown and a powerful feeling of sadness at the death of Philip Hamilton.

Quickly, a few highlights come to mind. There’s the dumb/brilliant simplicity of the motif “Aaron Burr, sir,” permuted again and again over the course of the play. There’s the astonishing vignette “Farmer Refuted,” where Hamilton tears Samuel Seabury’s words apart by literally speaking between them—basically, it’s Miranda proving the supremacy of rap as a form of expression. There’s the neat fact that the high points of excitement in the first act, which is about the Revolutionary War coalition, are crew raps; the pulse-quickeners in the second act, about the fractious aftermath, are diss tracks. There’s the epic wedding toast of “Satisfied,” which brackets songs within songs, speeding up and slowing down time as Angelica airs her regrets. There’s the way “Non-Stop” ends the first act by introducing a new melodic theme and then working the old themes in, while also packing its scenes with asterisk-like moments where Hamilton shows his delightful lack of chill (“okaaaay… one more thing,” “treasury or state?” “I was chosen for the Constitutional Convention!”).

Hamilton can achieve all of this because it’s not purely any one thing—it can use hip-hop’s rules and break them, use musical theater’s rules and break them, and thereby show how much genre conventions really shouldn’t matter. It’s also a bracing reminder that blockbuster mass entertainment can—with, yes, great effort—coexist with powerful art, in a year where some of music’s most brilliant minds (Lamar, Sufjan Stevens, Bjork) took the admirable but insular route. Here’s hoping Alexander Hamilton’s example goes on to inspire a generation of artists, and not just on Broadway.

New York's 'Historic Agreement' on Solitary Confinement

New York will enact major changes to its use of solitary confinement in prisons as part of a settlement with the New York Civil Liberties Union, the state announced Wednesday. The announcement from one of the nation’s largest prison systems caps the most successful year yet for solitary-reform advocates.

Under the agreement, about one-quarter of the state’s 4,000 prisoners in solitary confinement will be placed in less isolated housing. New York will also reduce the use of solitary for future inmates by limiting both the reasons they can be placed in it and the time they spend in it. Some of solitary confinement’s more troubling aspects will also be curtailed: Prison officials will no longer be allowed to use food as punishment, and pregnant inmates won’t be placed in solitary “except in exceptional circumstances.”

The agreement, which will needs approval from a federal judge before it goes into effect, was reached after two years of negotiations following a NYCLU lawsuit.

“Today marks the end of the era where incarcerated New Yorkers are simply thrown into the box to be forgotten under torturous conditions as a punishment of first resort,” Donna Lieberman, the NYCLU executive director, said in a statement announcing the settlement, “and we hope this historic agreement will provide a framework for ending the abuse of solitary confinement in New York State.”

New York’s powerful Correctional Officers and Police Benevolent Association expressed skepticism.

“While we have not had the opportunity to review the details of this settlement, our state’s disciplinary confinement policies have evolved over decades of experience, and it is simply wrong to unilaterally take the tools away from law enforcement officers who face dangerous situations on a daily basis,” Michael Powers, the union’s president, said in a statement.

New York first experimented with solitary confinement in 1821 in an attempt to replicate penal reforms in neighboring Pennsylvania. Quakers and other religiously minded prison advocates of the era supported keeping prisoners in prolonged isolation during their sentences. There, it was argued, criminals could mediate upon their crimes and become “penitent” before returning to society. They viewed this as a humane alternative to the deplorable conditions of American and European prisons at the time.

Intrigued by the idea, France’s restored Bourbon monarchy dispatched two writers, Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont, to the United States in 1831 to study the penitentiary model’s potential for French prisons. De Tocqueville later wrote his celebrated book Democracy in America based on his travels for this project. When he and de Beaumont returned to France in 1832, their report endorsed some of the efforts, but also described New York’s failed experiment at Auburn Prison a decade earlier.

The northern wing having been nearly finished in 1821, eighty prisoners were placed there, and a separate cell was given to each. This trial, from which so happy a result had been anticipated, was fatal to the greater part of the convicts: in order to reform them, they had been submitted to complete isolation; but this absolute solitude, if nothing interrupt it, is beyond the strength of man; it destroys the criminal without intermission and without pity; it does not reform, it kills,

During their prolonged isolation, de Tocqueville and de Beaumont wrote, the prisoners “fell into a state of depression so manifest that their keepers were [also] struck with it.” Five of the inmates died; others went insane. Eventually, the governor of New York intervened and ended the experiment by pardoning 26 of the inmates. Prison officials allowed the rest to leave their cells during the day to toil alongside other prisoners in Auburn’s workhouse.

By the late 19th century, solitary confinement largely fell out of use. The Supreme Court first noted its disturbing impact on prisoners’ mental health in In re Medley in 1890 when it was imposed on death-row inmates in Colorado. After a long quiescence, prolonged isolation enjoyed a modern renaissance in the 1970s and 1980s as the nation turned towards mass incarceration. Precise statistics are unavailable, but estimates suggest that between 70,000 and 100,000 inmates are kept in prolonged isolation in the United States.

In June, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote an unusual concurring opinion that all but urged the legal community to bring a case about long-term solitary confinement to the Supreme Court’s docket. Invoking Medley, Kennedy wrote that recent scholarship “still confirms what this Court suggested over a century ago: Years on end of near-total isolation exact a terrible price.” He described it even more bluntly during a congressional hearing three months earlier. Solitary confinement, Kennedy told legislators, “literally drives men mad.”

New York’s settlement follows a string of legal victories by other solitary-reform groups in the nation’s largest prison systems. In May, Illinois said it would sharply curtail the use of solitary confinement for juveniles as part of a settlement with the ACLU. California, which struggled with hunger strikes over its solitary policies in recent years, approved a broad slate of changes in September to settle a lawsuit brought by groups seeking changes in prisons.

Obama on San Bernardino: 'We Are in a New Phase of Terrorism'

President Obama visited Thursday the federal agency that has the task of analyzing all U.S. intelligence on terrorism as part of a weeks-long effort to calm a nervous public following deadly attacks in San Bernardino, Paris, and elsewhere.

“At this moment, our intelligence and counterterrorism professionals do not have any specific and credible information about an attack on the homeland,” Obama said at the National Counterterrorism Center in Virginia. “That said, we have to be vigilant ... we are in a new phase of terrorism, including lone actors and small groups of terrorists, like those in San Bernardino.”

Just weeks after after a team of Islamic State terrorists killed 130 people in Paris, a married couple killed 14 people and wounded 21 others in a shooting rampage in San Bernardino, California, allegedly in the name of foreign terrorist organizations. Unlike large-scale, carefully orchestrated attacks, an assault like the one in San Bernardino is “smaller, often self-initiating, self motivating” and “harder to detect,” Obama said Thursday.

“And that makes it harder to prevent,” he said. “But just as the threat evolves, so do we. We’re constantly adapting, constantly improving, upping our game, getting better.”

In the days after the attack in San Bernardino, federal investigators determined the shooters, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, were inspired by Islamist extremists and had spoken of jihad online as long ago as 2013. But those communications were “private direct messages,” the FBI said, and would not have been detected by U.S. intelligence employees.

Obama said national security officials will use the San Bernardino shooting to“learn whatever lessons we can and make any improvements that are needed.”

“In the meantime, what the world doesn’t always see are the successes, those terrorist plots that have been prevented,” he said. “And that’s how it should be. This work oftentimes demands secrecy.”

Obama said the government will tighten security surrounding the visa-waiver agreement, a program that allows citizens from 38, mostly Western, countries to visit the United States for three months without visa; and review the K-5 fiancee visa program under which Malik entered the country last year to marry Farook. The president said refugees entering the U.S. “will continue to get the most intensive scrutiny of any arrival.”

The president receives an update on potential threats from the National Counterterrorism Center before the holidays every year, but usually in the Situation Room in the White House. Obama was joined on stage during his remarks Thursday by Nicholas Rasmussen, the director of the center, Vice President Joe Biden, secretaries John Kerry of State and Jeh Johnson of Homeland Security, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, FBI Director James Comey, and James Clapper, director of the Office of National Intelligence.

The visit concluded a week of counterterrorism-focused meetings by the Obama administration. On Monday, Obama made a rare trip to the Pentagon, where he met with his cabinet officials and senior national-security advisers in a gathering billed as a “quick update” on the more than 18-month-old campaign against the Islamic State. On Tuesday, Kerry met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow to push for a diplomatic solution to the Syrian civil war, which could lead to cooperation between Washington and Moscow in their independent responses to the Islamist militant group.

On Wednesday, Defense Secretary Ash Carter met in Baghdad with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, to whom the administration has offered U.S. attack helicopters to help in ground offensives against the Islamic State in Ramadi. On the same day, Johnson activated a new terrorism warning system for the country, replacing an existing system that was introduced in 2011 but never activated because of its high threshold for credible or imminent threats. Under the new protocol, the homeland security department will issue periodic announcements about more general threats identified by federal officials.

“Particularly with the rise in use by terrorist groups of the Internet to inspire and recruit, we are concerned about the ‘self-radicalized’ actor(s) who could strike with little or no notice,” the department said on its website.

Obama heads to San Bernardino on Friday to meet privately with the families of the shooting victims, before flying to Hawaii for his annual two-week vacation.

‘Baker Street’: The Mystery of Rock's Greatest Sax Riff

In the summer of 1978, Gerry Rafferty's song “Baker Street” became a top-five hit in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

And for good reason. If there were an official anthem for playing darts alone in an empty roadside bar during a rainstorm, it would be “Baker Street.” And while there’s no data to back it up, “Baker Street” is undoubtedly the top song to idle to in a driveway before cutting the engine to your Dodge Aspen. (Both of these were popular hobbies in the year 1978.)

The video for “Baker Street” has been viewed over 5 million times. Its most popular comment is this: “This song makes me think of the Summer of 1978. Just graduated high school and was getting ready to head off to college. Nice memories.” (Thanks, Jack.)

Many listeners come to “Baker Street” (and stay) for its hypnotic saxophone line. It’s a haunting sound that drops bread crumbs from a listener’s pocket for their melancholy to follow. But few people know the origin story of rock’s most iconic sax riff, which is complicated, to say the least.

The man behind the saxophone was Raphael Ravenscroft, who in addition to having the best-ever name for a session saxophonist, claims to have authored the riff. According to his account, “Baker Street” had several gaps in it when he was hired to play, and he filled them.

“In fact, most of what I played was an old blues riff,” he once explained. “If you’re asking me: ‘Did Gerry hand me a piece of music to play?’ then no, he didn’t.”

The testimony of Ravenscoft, who died last year, seems to be refuted by the existence of an early demo of the song, where the guitar replaces the sax. That’s not to diminish Ravenscroft because, denuded of the sax, “Baker Street” sounds like another middling acid trip of a song in a decade full of them.

Given the song’s ubiquity and influence, it’s understandable that Ravenscroft might later fib about his role. Also, according to legend, he was only paid £27 for his contribution, while Rafferty was said to have made £80,000 in annual royalties until his death in 2011. But the song did benefit Ravenscoft’s career, and he went on to work with Pink Floyd, Marvin Gaye, and Daft Punk.

* * *

The guitarist Hugh Burns has scored movies like Die Another Day and The Hobbit, and played with the likes of Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson, Jack Bruce, and George Michael throughout his storied career. Burns is responsible for the blistering guitar solo on “Baker Street ” and considers working with Gerry Rafferty one of his life’s great honors.

“Quite frankly, I loved his songs. I regard it as a great good fortune that I was able to meet and contribute something to Gerry’s music,” he told me over the phone from England. “I did six albums with him. I probably did more music with him than any other musician.” He was also friends with Ravenscroft and toured with him.

Burns was performing on the road with Jack Bruce in 1978 when he made arrangements to visit the London studio where Rafferty’s album City to City was being recorded. “I went to the studio after I played the gig and I think one of the first songs we played was ‘Baker Street.’ And I said, ‘This is fantastic. This is a great song.’”

Burns told me that there’s no question that Rafferty came up with the music that became the famous riff line on “Baker Street.” After Burns laid down the solo, Rafferty asked him to “have a go at what obviously became very famous, which was the sax line.” Burns tried it on guitar, but the two men agreed that it would be better on the saxophone. “That’s the way I always saw it,” he remembers Rafferty telling him at the time.

“It’s important to say that in the case of that particular instrumental opening to ‘Baker Street,’ it was entirely Gerry’s line,” said Burns. He also referenced the demo, explaining that it was Rafferty himself playing the line on guitar.

Then, in the most offhand, glory-belying way, Burns dropped in this aside:

Strangely enough, another record that I played on, which was a massive hit, certainly in this country and I think in America as well, was called “Careless Whisper,” that also had a massive opening solo. And the interesting thing is that that sax solo, the line itself, was also given by the singer [George Michael]. There’s no question about that either.

* * *

So, it seems clear enough. Rafferty came up with the hook. But depending on whom you ask, the intrigue doesn’t quite end there. For decades in England, for instance, there was a widely believed urban myth that Bob Holness, the buttoned-up British gameshow host, had actually performed the saxophone solo in “Baker Street.”

And there’s still another wrinkle on the other side of the pond. Back in 1968, 10 years before “Baker Street” was recorded, Steve Marcus, a tenor sax player who toured with the jazz great Buddy Rich, released Tomorrow Never Knows, the first and only record under his own name.

The jazz-rock fusion album was almost exclusively of cover songs such as The Beatles’ title track. It also included a few original compositions, including a song called “Half a Heart.” The first nine seconds may give you chills.

The Internet is a conspiracy-theory clearing house, and yet the connection between “Baker Street” and the opening riff of “Half a Heart” lives in semi-ubiquity. Marcus passed away in 2005 and none of the tributes to him seem to make mention of it. It’s a topic that’s since been remaindered to the small music forums at the dusty edges of the Internet.

Curiously though, the composition of “Half a Heart” is credited to Gary Burton, a vibraphonist and composer, who went to Berklee College of Music with Marcus in the early 1960s and lived down the block from him when the two moved from Boston to New York to start their music careers.

When I reached out to Burton earlier this week to ask him if he or Marcus had ever made the connection to “Baker Street,” he was caught a little off-guard.

Honestly, until receiving your email, I had never heard of Gerry Rafferty, or the song “Baker Street,” so I’m pretty sure I don’t have any meaningful insight to offer specifically about the song. I just now went to the Internet and, sure enough, found out the history of Rafferty and “Baker Street,” and viewed a YouTube performance of it. The sax solo did sound vaguely familiar, so perhaps I have heard this in the past on the radio somewhere along the way.

He told me that he and Marcus had been best friends at a time and wanted to know what the connection to Steve Marcus was, since Ravenscroft is listed as the saxophonist on “Baker Street.” When I replied that Rafferty’s song sounded suspiciously familiar to Marcus’s song “Half a Heart,” he didn’t buy it on principle.

“Truthfully, I sort of doubt that a British saxophonist would have even of heard Marcus’s record, since it was little publicized and truly under the radar, even in the U.S.,” he wrote, later explaining that he thought the record had sold maybe 1,000 copies. “It disappeared.”

But when we spoke on the phone later, he’d changed his mind. “After listening to the two songs side-by-side, I have to say they are close enough that it seems almost certain that the British saxophone player [Ravenscoft] must have heard Steve’s record.” He added that since “Half a Heart” came out 10 years before “Baker Street,” someone must have heard the record. “It’s almost identical, only a little bit different and that wouldn’t happen by chance seeing as it was so close.”

Despite being credited with the song, at least across the Internet, Burton himself hadn’t been familiar with “Half a Heart.” Moreover, he was baffled when I told him that he had been listed as the song’s composer.

Isn’t that interesting because I definitely did not compose it. I never heard before until I just now listened, but I am sure if I had actually written the song back in the day I would have retained my copyright as I always did and would have been aware of it.

Burton surmised that if the credit weren’t a mistake, it constituted some kind of shoutout from Marcus. Though they had drifted apart by 1968, Burton visited in the studio while he was recording Tomorrow Never Knows. “It was a big deal for Steve to make a record on his own,” he said. “All his friends were kind of wishing him well.”

Hugh Burns hadn’t heard “Half a Heart,” but he was dismissive of the idea that it had been lifted from something else, at least intentionally.

“With due respect, there’s only 13 chromatic notes,” he said. “There are lots and lots of instances where things are very similar.” He added that in 30 years of playing, he never encountered anyone who asked for or wanted to specifically copy another piece of music.

In conversations with both Burns and Burton, a controversy and lawsuit involving George Harrison came up. In the “My Sweet Lord” case, Harrison admitted he simply hadn’t realized that the song so closely resembled “He’s So Fine,” made most famous by The Chiffons. Or as Burton put it, “You hear something, your brain forgets.”

“Musically, all the decisions on a Gerry Rafferty album, all the decisions on ‘yes, that stays,’ or ‘no, that goes’ were fundamentally his,” said Burns. “It’s important to understand that. He was an artist through and though.”

* * *

Seemingly alone in its era, “Baker Street” managed to stand out at the height of punk and new wave and also shined through the summer of Grease and the twilight of disco’s last saccharine gleaming. (The song spent six weeks stuck at No. 2 on the American Billboard charts behind Andy Gibb’s “Shadow Dancing.”)

No matter the true genesis of its sax riff, the song still endures. In 2010, “Baker Street” was honored by BMI for achieving 5 million radio plays worldwide. Its fellow honorees that year—“Come Together,” “Candle in the Wind,” and “Build Me Up Buttercup”—deliver some sense of the song’s real reach.

“Baker Street” has been covered by a wildly diverse set of outfits, most virtuously by Waylon Jennings and the London Symphony Orchestra, most sentimentally by Lisa Simpson, and most blandly by the Foo Fighters and Rick Springfield. It’s Springfield’s failure to make a glam-rock version song compelling in particular that helps in deciphering the extremely unconventional allure of “Baker Street,” a song ultimately about depression, transition, and weary aspiration.

I asked Burns why he thought “Baker Street” is still a staple nearly 40 years after its release.

First, he [Rafferty] wrote from his experience. So what you get is someone’s heartfelt experience and you put that into the lyric and into the song. The lyric and the melody fuse beautifully and the lyric is complemented by the melody. The music itself—the orchestration, so to speak— compliments the lyric in a perfect way.

Burns also nodded to the song’s unusual structure, which he compared in its unorthodox nature, to Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

“It’s not just opening, verse, chorus,” he said. “It doesn’t do that. It goes through a little kind of journey, it takes you through a journey and so, in some sense, it’s a very complete composition, which is unusual for popular music at that time. People weren’t quite used to that.”

Of course, there’s also something about the saxophone. In a 2011 episode of the NBC show 30 Rock, which aired the same year that Rafferty died, Tina Fey’s character paces the streets faced with the prospects of losing her job as a television writer. She encounters an unmerry troupe of subway-dwelling people “whose professions are no longer a thing.” Falling into that category are a travel agent, an American auto worker, the CEO of Friendster and, for the biggest punchline, a guy who “played dynamite saxophone solos in rock-and-roll songs.”

According to Burns, “a lot of the songs that seem to have some longevity tend to feature, for the most part, real instruments.” For a while, the saxophone was a key feature of that dynamic. Burns isn’t ruling out its return.

Musical is very cyclical. You never know a new generation of young musicians coming up [might bring back the sax]. I’ve got nothing against electronics. In the right music it sounds fantastic, it’s the only way to make certain kinds of music. But there’s something special about four or five guys in a studio and working with an artist and honing whatever it is that the song is and fine-tuning it. A lot of great music was made that way.

“Baker Street” and “Half a Heart” are songs that were made that way. We may never know if one influenced the other or it was just the alchemy of two different studios coming up with something unmistakably great. There’s enough evidence to be suspicious and more than enough time to enjoy them both.

The Arrest of the 'Pharma Bro'

Updated on December 17 at 11:19 a.m. ET

He raised the price of a life-saving drug from $13.50 to $750 and spent $2 million to buy the only copy of a Wu-Tang Clan album—making him the symbol of corporate excess and greed and earning him the monicker “Pharma Bro.” And on Thursday, federal agents arrested Martin Shkreli, 32, in connection with securities fraud linked to a company he started.

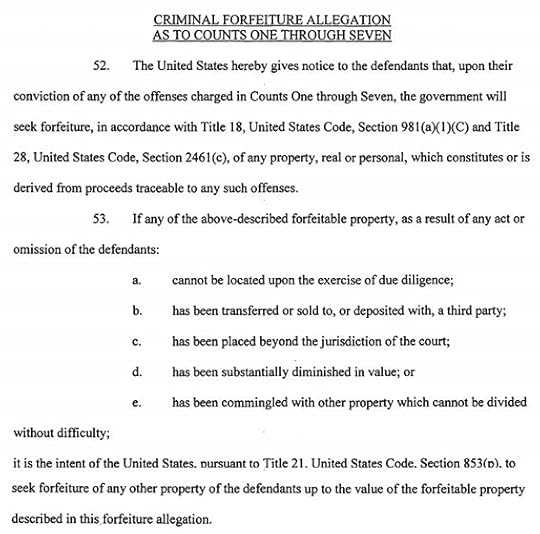

Shkreli and Evan Greebel, an associate, who was also arrested Thursday, were charged with two counts of securities fraud, three counts of conspiracy to commit securities fraud; and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. You can read the indictment against them here.

Shkreli ran his companies like “a Ponzi scheme,” and “lied to his investors,” Robert L. Capers, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York, said at a news conference in which the indictment against the two men was unsealed.

Bloomberg, which first reported the arrest, noted:

Prosecutors in Brooklyn charged him with illegally taking stock from Retrophin Inc., a biotechnology firm he started in 2011, and using it to pay off debts from unrelated business dealings. He was later ousted from the company, where he’d been chief executive officer, and sued by its board.

In the case that closely tracks that suit, federal prosecutors accused Shkreli of engaging in a complicated shell game after his defunct hedge fund, MSMB Capital Management, lost millions. He is alleged to have made secret payoffs and set up sham consulting arrangements. A New York lawyer, Evan Greebel, was also arrested early Thursday. He's accused of conspiring with Shkreli in part of the scheme.

Shkreli came into the public consciousness in September soon after his company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, bought the drug Daraprim, which is used to treat people with weakened immune systems, as in AIDS and during chemotherapy, and raised its price by 5,000 percent. In the backlash that followed, he was called “a spoiled brat,” and “the most hated man in America.”

At first, Shkreli appeared unapologetic about the backlash, but as it grew, he appeared to relent, only to backtrack.

“It’s a business,” he said at a health-care conference this month, “we’re supposed to make as much money as possible.”

He stayed in the news this month when he bought the only copy of Wu-Tang Clan’s new album, Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, and said his decision was prompted by “the opportunity to rub shoulders with celebrities and rappers who would want to hear it.”

As my colleague Spencer Kornhaber reported at the time: “The debate is now settled. Wu-Tang has made a horrible mistake.”

Bloomberg offers a rationale for Shkreli’s hold on our imagination:

But as my colleague James Hamblin noted soon after the controversy over the increased drug prices, Shkreli’s “may just as well be an imagined manifestation of national guilt over a broken health-care system, broken largely because of the costs of medications."The son of immigrants from Albania and Croatia who worked as janitors and raised him deep in working-class Brooklyn, Shkreli both epitomizes the American dream and sullies it. As a youth, he showed exceptional promise and independence and, after dropping out of an elite Manhattan high school, began his conquest of Wall Street before he was 20. …

Shkreli started his career interning for “Mad Money” host Jim Cramer while still a teenager. After recommending successful trades, Shkreli eventually set up his own hedge fund, quickly developing a reputation for trashing biotechnology stocks in online chatrooms and shorting them, to enormous profit.

Widely admired for his intellect and sharp eye, he pored over medical journals and self-trained in biology. He set up Retrophin to develop drugs and acquire older pharmaceuticals that could be sold for higher profits.

The little red guy with a pitchfork on our collective arthritic shoulder, Shkreli is a product, not a cause. Defeating him is treating a symptom, not creating a cure. In mocking his hubris we mock a person for operating within a system that we created and continue to subsidize. It took a firestorm of public outrage stoked by every national news outlet and multiple presidential candidates to get Shkreli to remit. But there are many more Shkrelis, and there will continue to be more Shkrelis.

Can the Feds Free Wu-Tang's Album From ‘Pharma Bro’?

Updated on Thursday, November 17 at 4:20 p.m.

Americans are a principled people. Gouge sick people for pharmaceuticals, and they’ll be angry. But buy the sole copy of a Wu-Tang Clan album for $2 million and they’ll start demanding action.

Thus with the arrest of Martin Shkreli—the reviled “pharma bro” famous for jacking up the prices of life-saving drugs—many people immediately had the same thought: Whither Once Upon a Time in Shaolin?

It was just last week that Businessweek revealed Shkreli had bought the sole copy of the album, paying around $2 million. My colleague Spencer Kornhaber took this as the final proof that Wu-Tang’s stunt of producing an album with only one copy and selling it to the highest bidder had backfired. (I’m not sure I agree: After all, what poetic justice is greater than price-gouging a price-gouger? But I digress.) Shkreli’s intentions for the album are unclear. On the one hand, he teased the idea he might play some pieces for the public; on the other hand, a recording was released in which he allegedly says, “I don’t know. I’ll probably never even hear it. I just thought it would be funny to keep it from people,” which would be fitting with the cartoon-villain profile he’s cultivated.

The question is, can the securities-fraud charges against Shkreli free the album? First, a quick rundown of the charges, for which he was arrested Thursday morning in (of course) Manhattan’s Murray Hill neighborhood. “Federal prosecutors accused Shkreli of engaging in a complicated shell game after his defunct hedge fund, MSMB Capital Management, lost millions,” Bloomberg reports. “He is alleged to have made secret payoffs and set up sham consulting arrangements.” Prosecutors allege that Shkreli stole stock from Retrophin, a biotech company he founded in 2011. After being ousted from Retrophin in 2014, Shkreli founded Turing, the company accused of price-gouging.

There are three immediately apparent ways this arrest and case might let Once Upon a Time into the public.

The first is asset forfeiture, a controversial practice in which law enforcement seizes cash and other goods without a warrant. Police might, for example, stop someone with thousands of dollars in cash, surmise that the money is involved in drug transactions, and seize the cash. The problem here becomes clear fairly quickly: Not everyone carrying cash is a drug kingpin; some are (for example) just traveling with their life savings. (Sarah Stillman tells some heartbreaking stories here.) In recent years, a coalition of leftist police reformers and libertarians has mounted a major charge against the practice. But with the Shkreli arrest, even some faithful liberals wondered if this was the one time when seizure might be justified, and the indictment suggests the feds just might try:

But experts seem to doubt it would work. Louis Rulli, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School who is an expert on forfeiture, explained in an email:

The government would need to either demonstrate that the property represented the direct proceeds of illegal activity or that there is a nexus—a substantial connection—between the underlying criminal offense with which he is charged and the property the government wishes to seize (and ultimately forfeit). As a general proposition, the government may only seize contraband (is the property per se illegal, such as drugs), the direct proceeds of illegal activity, or property used to facilitate illegal activity (did the property make the commission of the offense easier).

There’s one wisp of possibility: Where did the money come from to buy Once Upon a Time? Did it come from ill-gotten Retrophin gains? “I suspect that it would be very hard for the government in this case to directly tie the album (or its purchase funds) to the underlying offense, but I wouldn’t be surprised if prosecutors aren’t taking a hard look at all of Shkreli’s property and expenditures with this thought in mind,” Rulli said. U.S. Attorney Robert Capers said during a press conference Thursday that he did not know where Shkreli had acquired the money used to buy the album. The FBI also confirmed in a tweet (!) that it had not seized the record on Thursday:

#Breaking no seizure warrant at the arrest of Martin Shkreli today, which means we didn't seize the Wu-Tang Clan album.

— FBI New York (@NewYorkFBI) December 17, 2015

A second possibility is that Shkreli might need to fork over money at some point in the future. For example, he could sell the album to raise funds to pay for his defense. It’s hard to find a reliable tally of Shkreli’s worth, but it’s likely in the tens of millions of dollars, so that reselling an album he bought for $2 million might not raise much money; besides, he clearly enjoys owning it to spite others. That said, it might be a faster way to raise cash than selling off other properties; Once Upon a Time in Shaolin is a liquid sword asset; cash rules everything around him, too.

Alternatively, if Shkreli is convicted, he could lose the album when the case is resolved. “If the government secures a conviction and gets a money judgment against Shkreli, they can forfeit anything—even clean assets—to execute their judgment,” Steven L. Kessler, an attorney and forfeiture expert, wrote in an email. “If, at the end of the day, he has none of the proceeds of the crime, the government may then forfeit the Wu-Tang Clan album together with grandma’s inheritance to satisfy their judgment.”

But there’s one more possibility. What if the charges against Shkreli are part of an elaborate plot? According to the Internet (caveat lector!) there’s a clause in the contract for the sale of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin that reads as follows:

The buying party also agrees that, at any time during the stipulated 88 year period, the seller may legally plan and attempt to execute one (1) heist or caper to steal back Once Upon A Time In Shaolin, which, if successful, would return all ownership rights to the seller. Said heist or caper can only be undertaken by currently active members of the Wu-Tang Clan and/or actor Bill Murray, with no legal repercussions.

Sounds like a hoax, and yet the RZA tweeted this after the sale become public:

We're really getting the urge to call Bill Murray.

— RZA! (@RZA) December 11, 2015

Imagine a situation in which Shkreli’s arrest is a ploy, allowing members of the Wu-Tang Clan a chance to break into his apartment and snatch back the record. The group has been investigated for criminal plotting before. (Has anyone seen Bill Murray lately? I’m currently trawling the indictment for numerological hints.)

If this all sounds far-fetched, it’s wise to return to first principles: Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nuthin’ ta f’ wit.

Putin’s Wide-Ranging News Conference

Russian President Vladimir Putin held his annual news conference Thursday, a wide-ranging event that lasted more than three hours.

Putin didn’t mince his words when discussing his country’s military intervention in Syria, its relations with Turkey after the shooting down of a Russian warplane, and its presence in Ukraine. But he also touched on topics as diverse as the Russian economy, the U.S. presidential elections, his daughters, and Sepp Blatter, the embattled head of FIFA.

Here are some of the more interesting excerpts from the news conference that was conducted before a live studio audience and included both Russian and Western journalists:

Turkey

Relations between the once-close allies were strained even before Turkey shot down a Russian warplane last month, resulting in the death of the plane’s pilot. The two countries are on opposite sides of the Syrian civil war. Russian aircraft are targeting the Islamic State and other rebel groups, including those backed by the West and Turkey, on behalf of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Turkey and others, including the U.S., want Assad to step down as part of the political process to end the Syrian civil war.

Putin described Turkey’s actions as “an act of hostility,” saying the Turkish government was hiding behind its membership in NATO.

And, he added: “The Turks decided to lick the Americans in a certain place.” It’s unclear what “place” the Russian leader was referring to.

Putin added that relations with Turkey were unlikely to improve under that country’s present leadership.

American Presidential Elections

Putin was asked about Donald Trump, the Republican presidential front-runner, and he said he found the mogul to be “tremendous.”

“He is a very bright person, talented without any doubt,” he said after the news conference. “It is not our business to assess his worthiness, but he is the absolute leader of the presidential race. He says he wants to move to a different level of relations—a fuller, deeper [level]—with Russia, how can we not welcome this? Of course we welcome this.”

Last month, Trump said during the Republican presidential debate that he got to know the Russian president “very well, because we were both on 60 Minutes, we were stablemates and we did very well that night.”

But as others have pointed out, the Republican presidential candidate and the Russian president appeared in separate, taped segments for the CBS show. Trump was interviewed in New York; Putin in Russia.

At a previous Republican debate, in September, Trump said he would “get along” with Putin.

“I believe—and I may be wrong, in which case I’d probably have to take a different path—but I would get along with a lot of the world leaders that this country is not getting along with,” he said.

Ukraine

Putin also addressed his country’s role in Ukraine’s civil war, where Russia supports separatists in the Donetsk region. He acknowledged there were Russians in Ukraine, but denied they were military personnel.

“We never said we don’t have people in Ukraine solving military issues there,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean we have deployed regular troops there.”

The Russian Economy

The Russian president also discussed his country’s economy, which has been battered by record-low oil prices that have resulted in a 3.7-percent loss in Russian gross domestic product and a 12.3-percent rise in inflation over the past year.

“Statistics show that the Russian economy all in all has passed the crisis,” he said. “The peak of the crisis, in any case.”

He said investors “are beginning to show interest in working here,” and said Russia was “witnessing a net inflow of capital.”

Still, the price of oil must heavily weigh on the minds of Russian policymakers. Last year’s budget was predicated on oil costing $100 per barrel. But oil prices have been sliding, on the back of a glut in the market. Russia, one of the world’s top oil producers, had based this year’s budget on oil being priced at about $50 per barrel. They now stand at below $37.

“We counted the budget for next year using this figure, this is an optimistic mark for today—$50 per barrel,” Putin said. “But now … it is already 38. Therefore we will have to correct something here too.”

Other Issues

Putin rejected the idea that Russia pressured FIFA, soccer’s governing body, to grant Russia the World Cup in 2018, and he defended his ally, Sepp Blatter, the embattled head of the organization who has been suspended by FIFA’s ethics panel over a corruption scandal. Putin called Blatter a “respected man,” who has done a lot for the development of soccer worldwide.

“You know, his contribution in the humanitarian sphere in the world is enormous,” he said. “He always used or tried using football not just as a sport, but as an element of cooperation between countries and peoples. This is who should be given the Nobel Peace Prize.”

The Russian leader also discussed his daughters, about whom little is known or reported. He said they were educated and living in Russia.

“I’ve seen different reports about my daughters—the media were saying they are getting an education abroad and are living abroad,” he said. “Now, thank God, this isn’t the case. It’s true: My daughters are living in Russia; they do not have any other permanent residence. They’ve only been studying at Russian universities.”

He added that his daughters speak three European languages fluently, and “one or two oriental languages,” and use them “daily at work.”

The Year in Sports Scandals

From "Deflategate" in January, to Sepp Blatter's departure from FIFA, to charges of illegal gambling in fantasy sports, 2015 was another year filled with stories of big names in sports being dragged through the mud. 2014's reports of bullying in the Miami Dolphins locker room seem far away.

Allegations of corporate espionage, doping, and straight-up cheating dogged the sports world this year, tarnishing everything from baseball to boxing. Pristine legacies, of individual players as well as storied clubs, were marred, leaving fans with little left to unconditionally adore.

And so, in no particular order, we present you with a brief and absolutely non-comprehensive list of this year’s sporting shame:

December 16, 2015

Walmart, Whole Foods, and Slave-Labor Shrimp

On Monday, a major AP investigation shook the seafood-loving public when it implicated several major American food purveyors with selling shrimp that had been peeled using slave labor in Thailand.

The list of the companies involved, as well as the scope of the labor abuses, which involved children, is staggering. For now, here’s the former:

U.S. customs records show the shrimp made its way into the supply chains of major U.S. food stores and retailers such as Wal-Mart, Kroger, Whole Foods, Dollar General and Petco, along with restaurants such as Red Lobster and Olive Garden.

It also entered the supply chains of some of America's best-known seafood brands and pet foods, including Chicken of the Sea and Fancy Feast, which are sold in grocery stores from Safeway and Schnucks to Piggly Wiggly and Albertsons. AP reporters went to supermarkets in all 50 states and found shrimp products from supply chains tainted with forced labor.

As Roberto Ferdman of The Washington Post points out, this is neither the first nor the second time in recent years a spotlight has been shone on shrimping practices in Thailand. He adds that this latest report “holds that such abuses are still rampant in the Thai shrimp industry” and chastised major markets for not “keeping shrimp peeled by modern-day slaves out of their food system.” As the AP reports, shrimp remains a key part of Thailand $7 billion seafood export business.

On Tuesday, Red Lobster, which has a popular annual promotion called “Endless Shrimp,” became one of the few companies to deny buying shrimp from illicit processors. “We are confident based on our findings and assurances from Thai Union that our seafood supply was not associated with the abusive pre-processing facilities,” the company said in a statement.

In a vague tweet, Whole Foods also denied selling shrimp that is peeled using slave labor.

After thorough investigation, we're confident Thai Union shrimp at our stores did not come from illicit processing facility…

— Whole Foods Market (@WholeFoods) December 15, 2015

The company later clarified that it does not sell the kind of shrimp specified in the AP report. “All our shrimp is either raw with the shell on, or cooked in the shell and then peeled in approved production facilities,” CNN reported.

Nevertheless, Whole Foods isn’t severing its relationship with Thai Union. The company said it would support a Thai Union pledge to bring all of its shrimp-processing operations in-house by the end of 2015.

Wal-Mart, on the hand, did not deny that its supply chain may have involved forced labor.

We are aware of the Associated Press story, and we were horrified by the conditions and treatment of workers the reporters uncovered. The ethical recruitment and treatment of workers in the industry as a whole is extremely important to us, which is why we are working hard to form coalitions and partnerships that will help lead to sustainable improvements in the industry.

But, after so many exposés, it’s getting increasingly easy to ask if anything will really change? In a Reddit Ask-Me-Anything, Martha Mendoza, one of the four AP reporters who worked on the six-month investigation, concluded this: “There is more oversight in seafood to protect dolphins than there is to protect humans.”

Star Wars: The Cloned Reviews Awaken

When it comes to Star Wars, hype has always been an important part of the overall experience. A new installment in the beloved sci-fi franchise, for example, has been praised by critics for being “deliriously inventive,” “an astonishing achievement in imaginative filmmaking,” and “captivating.”

I am, of course, talking about The Phantom Menace, the first of the three Star Wars prequels, which most fans of the original movies pretend don’t exist.

The seventh movie in the series, The Force Awakens, comes out tomorrow, and already critics are rhapsodizing about its “strong performances,” “old-fashioned escapism,” and script that “has a better and sharper sense of humor than the original trilogy.” Which bodes well for fans. Except: The same thing happened in 1999, when the first Star Wars prequel met with almost universal acclaim, which turned into late-breaking disdain. The sneering carried over to its sequel, the laughably bad Attack of the Clones, a movie about which The Hollywood Reporter said: “The good news about George Lucas’ new Star Wars movie is that the universally loathed Jar Jar Binks is little more than a dress extra.”

By the time Revenge of the Sith rolled around in 2005, many were hopeful Lucas could rescue the franchise he’d created a long time ago, in a studio far, far away. At the time, The New York Times called it “by far the best film in the more recent trilogy, and also the best of the four episodes Mr. Lucas has directed. That’s right: it’s better than Star Wars.” Honestly, it’s not; a view that’s now less controversial than the debate over who shot first.

There were reviews that pilloried the movies, of course (especially the second installment), but, in general they were drowned out by those twin pillars of the Hollywood publicity machinery: hype and hope. And despite the disdain, and fans’ attempts to excise the films from the public consciousness, the three movies made about $2.5 billion at the worldwide box office.

Which brings me to the question: Is it possible to dislike Star Wars: The Force Awakens given that we already know that it’s going to be great, “epic, awesome, and perfect”? I bring all this up as someone who remembers the excitement surrounding Episode I. I wanted to love it, came out of the theater loving it, watched it again and again, and then slowly realized how bad it really was. I, like the film critics, turned my ire toward a worthy object, Episode II, and, to a lesser extent, Episode III. But by then, it was too late. Now, I just pretend those movies didn’t happen: Jar-Jar, midi-chlorians, intergalactic trade negotiations all relegated deep into the sarlacc’s digestive tract.

What must it have been like to watch the original movie, Episode IV: A New Hope, in 1977? It didn’t have the advantages of its sequels, and certainly not its prequels. It was George Lucas’s first film since American Graffiti in 1973. It came to screens with little of today’s advance publicity and was made at a cost of $11 million (about $40 million in today’s dollars). And not all reviews were glowing.

Here’s an early one:

Strip Star Wars of its often striking images and its high-falutin scientific jargon, and you get a story, characters, and dialogue of overwhelming banality, without even a "future" cast to them. Human beings, anthropoids, or robots, you could probably find them all, more or less like, that, in downtown Los Angeles today...

Still, Star Wars will do very nicely for those lucky enough to be children or unlucky enough never to have grown up.

But The Times was more positive at the time:

Star Wars, which opened yesterday at the Astor Plaza, Orpheum and other theaters, is the most elaborate, most expensive, most beautiful movie serial ever made. It's both an apotheosis of Flash Gordon serials and a witty critique that makes associations with a variety of literature that is nothing if not eclectic: Quo Vadis?, Buck Rogers, Ivanhoe, Superman, The Wizard of Oz, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, the legend of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table.

Similarly, the Los Angeles Times lauded the original movie, calling it “an exuberant and technically astonishing space adventure in which the galactic tomorrows of Flash Gordon are the setting for conflicts and events that carry the suspiciously but splendidly familiar ring of yesterday’s westerns, as well as yesterday’s Flash Gordon serials.” (Which tells you how far Flash Gordon has fallen in our cultural consciousness.)

Its two sequels, Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, came into a world where the Star Wars universe was a cultural and marketing phenomenon. Which brings me to The Force Awakens.

Can it justify—or even survive—the buildup that began in October 2012 with the announcement that Disney was buying Lucasfilm for $4 billion? The hype that continued when the cast of the new film was unveiled in April 2014? And that reached near-hysterical proportions when the movie’s title was revealed in November of that year? Disney released teaser after teaser, followed by trailer after trailer to whet fans’ collective appetites. And then there were the tie-ins: Adidas for your padawans, Kraft mac-n-cheese in a “room of lies,” and, yes, Covergirl makeup—prompting Wired to quip the marketing had “jumped the Gundark.” All of which proves, as was depressingly predicted before the release of The Phantom Menace, that The Force Awakens “will make money even if nobody buys a ticket to see it.”

Fans hope it will erase the painful memories of Episodes I, II, and III, but hopefully not make them more powerful than you could possibly imagine. Early reviews for the movie are good and expectations high. Fandango, the online ticket seller, says sales for Episode VII have already surpassed every other movie for which it has sold tickets. I’m one of those hopefuls. I plan to watch it on Friday, and then again over the weekend, with mixed emotions: I already know I have to like the movie, and that I probably will. But will that fondness carry over through decades, the way it did for the original trilogy, or is The Force Awakens a (marketing) trap that’s peddling on our collective nostalgia? As Yoda might say: Not what it used to be, nostalgia is.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower