Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 209

March 18, 2016

Pee-wee’s Misadventure

The Wikipedia entry for “Pee-wee Herman” begins by noting that the figure in question is “a comic fictional character” who is “best known for his two television series and film series during the 1980s.” The entry goes on to list Pee-wee’s species as “human” and his sex as “male.”

Related Story

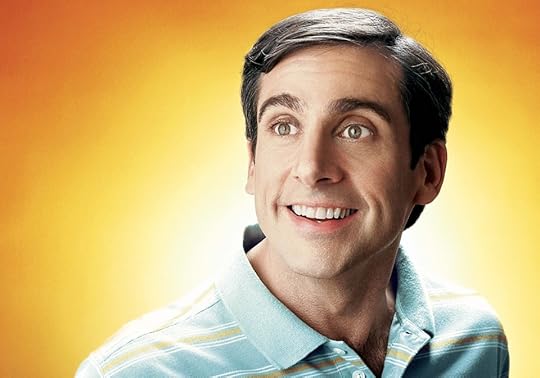

The 40-Year-Old Virgin Is 10—And All Grown Up

These classifications are true, for the most part, but they are also, as so many things are these days, complicated. Pee-wee, for all his human attributes, does not seem to engage in that most fundamental of human activities: aging. And he is a male who does not seem to be interested in that most fundamental of human preoccupations: sex. This—Pee-wee’s status as a man-child, a Peter Pan in pancake makeup—is the source of his charm; it is also, sometimes, the source of his menace. David Letterman, who first helped to propel Pee-wee—and his portrayer, Paul Reubens—to fame in the early 1980s, has observed that the character “has the external structure of a bratty little precocious kid, but you know it’s being controlled by the incubus—the manifestation of evil itself.”

That might be slightly overstating the case, but it helps to explain why Pee-wee has remained compelling and also confusing to audiences in the ’80s and ’90s and beyond: He embodies a tension that is understood both by kids who think the world is biased against them, and by adults who think the same. Every Pee-wee property (and there have been a lot of them over the years, from the TV show Pee-wee’s Playhouse to the films Pee-wee’s Big Adventure and Big Top Pee-wee) has somehow exploited that man-child dialectic. And you might think that the new one—Pee-wee’s Big Holiday, the Netflix feature produced by the bard of man-children everywhere, Judd Apatow—would be the most comprehensive exploration of them all. Here, you might think, is a perfect marriage of creators and subject matter: a film about an adult boy, created by people—the film was co-written by Reubens and Paul Rust, who, among other credits, was a writer for Arrested Development—who seem obsessed with the idea of, well, arrested development.

Pee-wee is a Peter Pan in pancake makeup. That is the source of his charm; it is also, sometimes, the source of his menace.

Certainly, Pee-wee’s childishness is on full display as he takes his Big Holiday. The plot goes like this: Pee-wee, frustrated to see everyone else in his hometown of Fairville growing up around him, has a chance encounter with Joe Manganiello (who is, extremely delightfully, playing himself (or, “himself”): a consummate Man’s Man, motorcycle and all, and also an actor who is extremely emotionally needy). Joe is having a birthday party in New York five days after he meets Pee-wee; in his capacity as a kind of karmic agent (a Hairy Godmother?), Joe invites Pee-wee to the party. (“The way I see it, Pee-wee Herman,” Joe sums it up, “you’ve got a choice to make: Stick around here, or live a little.”) And, because planes aren’t adventurous, Joe commands Pee-wee to make the trip on land.

Thus, a built-in bildungsroman, with the journey made via car and flying car and bus and river rapid and horse-and-buggy. Pee-wee’s trip features stops at a “snake farm,” and then an actual farm, and then New York City. It features encounters with a farmer’s daughters (because of course), and with the Amish (ditto), and with a wacky, aging heiress, and with the even wackier occupants of a mobile salon named “Free Wheelin’.” The trip offers Pee-wee, kind of, the chance to grow up.

Except: Does it? This is, throughout the movie, unclear. Here are some of the other things that take place over the course of Pee-wee’s holiday: Pee-wee rejects a woman who tries to ask him out; he develops a man-crush on Manganiello; he gets engaged, very much against his will, to one of the daughters of the farmer he encounters; and he has what may be his first kiss—with a bank robber (Alia Shawkat) with whom he shares an affinity because her nickname is ... Pee-wee.

One of the film’s many other instances of Pee-wee Ex Machina finds our hero, having arrived in New York, falling into a hole in Central Park. (It’s just there, perfectly Pee-wee-sized; don’t question it too much.) TV news crews find out about Pee-wee’s plight; they announce the news to their viewers with the chyron “BOY IN WELL.”

But, again: Is he a boy? It was, after all, mere moments earlier in Pee-wee’s Big Holiday that the Boy of “BOY IN WELL” fame was getting betrothed to a stranger. And, of course, the Boy in question has spent pretty much the entirety of his film dressed in that consummate uniform of masculine adulthood: a suit, a crisp shirt, a bow tie. And, it must also be said: The Boy in question is being played by an actor who is, no matter what good genes and good lighting and good makeup may have to say about it, 63 years old. It’s all a little too Cree-pee.

The to be sure part: The stage-in-life uncertainty here is, of course, at least part of the point. Pee-wee’s Big Holiday is on the one hand—like any Pee-wee adventure will be—a glorious, ridiculous monument to absurdity. Pee-wee will always be Dada. It’s silly to assign too much logic—too much cultural reasoning—to a character and a property that so insistently revel in their own madness. And there are, also, some decent jokes to be mined from the basic premise of a man-child navigating a world that that he doesn’t fully understand, and vice versa. When Pee-wee sits down to dinner with the farmer he meets, Farmer Brown, and his nine daughters, Brown asks him, “Would you like to say a few words?” Pee-wee doesn’t miss a beat. “Oh, sure,” he replies. “Encyclopedia. Pimple. And uh, hairball.”

Pee-wee hasn’t aged, but the rest of us have. And we’ve become a little more sensitive to the problems involved when grown men act like boys.

It’s funny! And it’s revealing! It’s making fun of Pee-wee, but it’s really making fun of all of us—and of our participation in a culture that is so strangely eager for its young people to grow up.

But none of that changes the fundamental weirdness: Here is a now-63-year-old man playing a character with the cognitive and social acuity of a prepubescent boy. Here is that man-boy having an early, electric kiss with a woman in her 20s (Alia Shawkat is 26). It’s awkward, but perhaps not in the way Reubens and his fellow creators intended. “The last time Pee-wee was in a movie, 1988’s Big-Top Pee-wee,” the L.A. Times points out, “Ronald Reagan was in the White House and O.J. Simpson was making Hertz commercials.” (And also: Jessica McClure, or “Baby Jessica,” had just captivated the American public by … falling into a well.) Pee-wee might not have aged since then, but the rest of us have. We’ve become a little more sensitive—thus making the hairdressers Pee-wee encounters in the “mobile salon,” who are basically walking stereotypes of gayness and blackness, not just unfunny, but troubling. We’ve become a little more savvy—making the film’s many jokes about farts and screams and heavy-set women read not as slapstick, but as laziness.

Mostly, though, we’ve become a little more leery of the regressive politics that will be involved, implicitly and otherwise, when grown men act like boys. We’ve lost some of the patience we once had for people who can’t seem to figure out how to grow up. It’s a good thing Pee-wee Herman, the “comic fictional character,” is not fully human. Because really: Imagine if he were.

Midnight Special: A Chase Movie With Supernatural Thrills

A boy wearing dark goggles and noise-canceling headphones, his father, and a mysterious driver get into a car and race into the night, perhaps running from something, or maybe in pursuit. Jeff Nichols’s new film Midnight Special is at its best when it keeps things simple: It’s a chase movie set in darkness, with a broken father-son dynamic that’s healing, and a history involving a religious cult that’s left largely unexplained. The weird thing is, the kid in the backseat of the car has glowing eyes, and Midnight Special is a sci-fi film—but you almost wish it wasn’t.

Related Story

The Moral Ambiguity of Foreclosure

Alton (played by Jaeden Lieberher, of Aloha and St. Vincent), is no ordinary kid. He’s Midnight Special’s emotional core and plot MacGuffin wrapped into one whole, a seemingly alien child plagued with all kinds of peculiar powers he can’t control. The film starts in the middle of an escape from the cult he called home, and barrels towards a loopy conclusion as Alton is chased by his former captors and the FBI. Why? We’re not entirely sure, and Nichols is very reluctant to explain, probably because the answers end up being so perfunctory and disappointing. When it’s on the road, Midnight Special is a largely thrilling ride, but whenever it stops to take a breath, the magic stops with it.

Like much of Nichols’s previous work, Midnight Special is set in an earthy American backwater, and co-mingles the mysterious with the mundane. Take Shelter (2011) was a Rust Belt thriller about a raving father plagued by apocalyptic visions he doesn’t fully trust; the more freewheeling Mud (2012) charted the relationship between two boys and a mysterious island dweller on the Arkansas River. Both featured Michael Shannon, the stony Oscar-nominated character actor with a face straight out of the Old Testament, and here he plays Alton’s father Roy, motivated to drive his son across the country by a deep well of unspoken guilt.

Roy is accompanied by Lucas (Joel Edgerton), a mysterious accomplice who’s almost as inscrutable but perhaps a little more confused by just what is going on. Alton is a quiet little gremlin in the back of the car, and he comes with a lot of unspoken rules: Don’t let the sunlight touch him. Don’t worry if he starts parroting radio signals and military code out of nowhere. And if he suddenly stops and looks directly at the sky, run away, because something crazy is about to happen. There are plenty more tricks, and the audience experiences them one by one, but at no point do Roy and Lucas display more than a hint of surprise at the supernatural goings-on around them.

Nichols seems fanatical about eking Alton’s complex backstory out as slowly as possible. Midnight Special keeps its parameters tight: Even as Alton is making satellites crash out of the sky and shooting mysterious blue energy out of his eyes, the focus stays on Roy and Lucas’s mission, to deliver him to an unknown location on the other side of the country, where … well, something will happen, we’re just not sure what.

Alton is no ordinary kid. He’s Midnight Special’s emotional core and plot MacGuffin.

There are shades of M. Night Shyamalan’s better work in Midnight Special, which focuses on a precocious child amid high-octane genre trappings. There’s more than a touch of Shyamalan’s forebear, Steven Spielberg, too—especially in the story that plays out around Roy, Lucas, and Alton, as the government tries to figure out just what’s so special about this kid, and what’s going to happen when he gets wherever he’s going. Adam Driver plays Paul Sevier, an NSA analyst who feels like an excitable cousin to Francois Truffaut’s extra-terrestrial scientist in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Driver’s nervy energy livens the film up whenever he’s onscreen, always one step behind Alton’s cross-country journey, but helping shed some light on his history for the befuddled audience.

Driver also gets to be funny—something Midnight Special could do with more of. In his promising career so far, Nichols hasn’t leaned on comedy too much, and while this film certainly cribs from Spielberg in some regards, it doesn’t carry over any of his whimsy. Roy is too haunted by past demons and his backstory in the religious cult created around his son, one that’s only marginally fleshed out through some conversations with Alton’s mother, Sarah (Kirsten Dunst), who shows up late in the film and doesn’t get nearly enough to do.

But Midnight Special is a chase movie, and like all chase movies it runs the risk of losing all narrative momentum once it arrives at a destination. Nichols does eventually offer an explanation, of sorts, but you almost wish he hadn’t. He gives his film several tense action scenes (thrilling shootouts, car chases conducted in night vision) executed at a perfect clip, but forgets to invest it with a larger sense of wonder. There’s technical verve a-plenty, and evidence that Nichols will continue to grow with his future projects, but Midnight Special feels more like a fun time at the movies that should have been an otherworldly blast.

March 17, 2016

Congress Plumbs the Depths of Flint’s Water Crisis

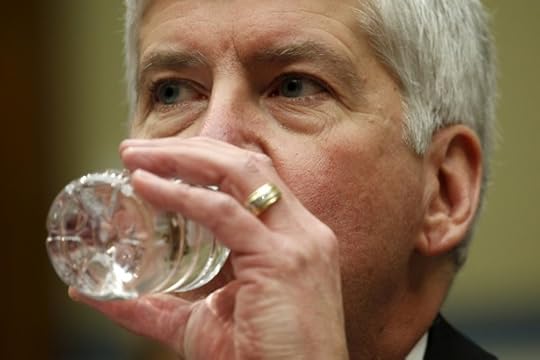

Rick Snyder didn’t want to do it.

The Michigan governor declined his first invite to testify before Congress about the Flint lead crisis. Then he reversed course and agreed to appear. Snyder’s trepidation was well placed. It was a tough day for Snyder on Thursday as he was battered by members of the House Oversight Committee.

Related Story

What Did the Governor Know About Flint's Water, and When Did He Know It?

Snyder, in his opening statement, tried to share blame with other authorities.

“Let me be blunt. This was a failure of government at all levels. Local, state, and federal officials—we all failed the families of Flint,” he said. “This is not about politics or partisanship. I am not going to point fingers or shift blame; there is plenty of that to share, and neither will help the people of Flint.”

The Republican said he learned of the crisis last fall. “It was on October 1, 2015, that I learned that our state experts were wrong. Flint’s water had dangerous levels of lead. On that day, I took immediate action.”

As Snyder’s critics have pointed out since the scandal broke, however, there was little real local authority in Flint, because the city was under the control of an emergency manager appointed by the governor. The city is only now working to regain all of its autonomy. Snyder admitted on Thursday “it would be a fair conclusion” to say that the emergency-manager law failed in Flint’s case.

Snyder’s account of when he learned about the poisoning raises eyebrows, too. Snyder accused the Environmental Protection Agency of stifling a report earlier in 2015 that would have blown the whistle; several EPA employees resigned when the incident came to light. Snyder has maintained he moved quickly once he learned about the crisis, but his timeline is undermined by emails and news reports. In essence, Snyder’s defense hinges on convincing the public that his aides did not inform him of a burgeoning crisis in the city and that he missed news reports about it.

In March 2015, for example, a Snyder aide was informed of an uptick in cases of Legionnaires’s disease, a bacterial infection that killed 10 people in Flint. The state Department of Environmental Quality downplayed any connection with the water supply. (Several department officials, including its chief, have been forced to resign.) In July, Snyder’s then-chief of staff complained in an email that residents of Flint were being shunted aside. The same month, my colleague Alana Semuels published a long article on the lead crisis.

During the hearing, Pennsylvania Democrat Matt Cartwright railed against Snyder and called on him to resign.

“I’ve had about enough of your false contrition and your phony apologies,” Cartwright said. “Plausible deniability only works when it’s plausible, and I’m not buying any of this that you didn’t know until October 2015. You were not in a medically induced coma for a year.”

So did Ranking Member Elijah Cummings of Maryland. “I’m going to have to live with this for the rest of my life,” Snyder said, to which Cummings replied: “You have to live with it, but many of these children will never be what God intended them to be when they were born.”

Whatever other ill effects the scandal has for Snyder’s conscience, it has derailed his political future. Once mentioned as a potential vice-presidential candidate for the GOP, his approval rating has tumbled 30 points in six months.

Republicans at the hearing had their own target, in EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy. Chairman Jason Chaffetz, in particular, had heated exchanges with her, accusing McCarthy of failing to use a provision to intervene.

“You failed. You had that under the law and you didn’t use it,” he said.

“No sir, I didn’t,” she responded, but he insisted she failed to use the tools at her disposal.

McCarthy and Republicans also tangled over whether the state had provided all the relevant information to her agency and over whether the employee who flagged the high lead levels had been disciplined. (He felt he had; Republicans said he had; McCarthy insisted he hadn’t.)

Depending on how cynical you are, Thursday’s hearing was a welcome moment of accountability, a cathartic but futile gesture, or feeble grandstanding by representatives. Congress could do more. There’s a $250 million bill for lead-affected communities under consideration. The bill represents a tiny fraction of the cost of stopping the threat to American water sources from lead, estimated at as high as $300 billion. But that bill has been blocked by Senator Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, who insists Michigan has all the money it needs. For the time being, hearings will have to do.

Did FBI Agents Lie About LaVoy Finicum's Shooting?

Given that it involved a weeks-long occupation of federal property by armed men, facing off against equally armed law enforcement, the standoff at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon ended almost as well as could be hoped—with the ringleaders, as well as Cliven Bundy, in jail, the refuge cleared, and only one death: that of LaVoy Finicum.

Finicum, who had become a de facto spokesman for the occupation, was shot on January 26 when Oregon State Police and FBI intercepted two cars that occupiers were driving to John Day, a nearby town. Both cars stopped. The occupants of one car surrendered, but Finicum, driving the other, drove ahead. When he encountered a roadblock, he tried to drive around it, but his SUV became lodged in snow. This was his vehicle’s second stop. Finicum jumped out of the vehicle and was shot. Even that shooting struck many observers as justified: Finicum had nearly hit agents with the truck, and as he was shot he was reaching for a pocket where a gun was found.

Related Story

Patience: The FBI's Strategy to End the Oregon Standoff and Nab Cliven Bundy

But now the clean finish isn’t looking so clean after all. A three-county investigation that wrapped up last week found that Finicum’s shooting by Oregon State Police was justified, but it also revealed the existence of two mystery shots, apparently fired by FBI agents. OSP officers apparently shot six shots—three at the truck as it barreled toward the roadblock, and then another three that struck Finicum after he left the car. But a cellphone recording by one of the people in the car, Shawna Cox, revealed two other shots, one of which blew out a window.

The problem is that FBI agents did not tell investigators they had fired the shots. Reportedly no one inventoried the FBI agents’ guns because none of the other people present had seen them shoot, and they didn’t say they had. Worse, there's some reason to believe the shots were intentionally concealed, The Oregonian reports. A state trooper reported seeing two bullet casings on the ground after the shooting. Those casings were copper-colored, while OSP uses only silver-colored casings. But those copper-colored casings were not found later in a sweep of the site.

Greg Bretzing, the FBI agent in charge of Oregon, issued a statement acknowledging the discrepancy:

The county’s investigation also indicated that, in between the two series of shots fired by OSP troopers, one, and possibly two, additional shots were fired by law enforcement as Mr. Finicum was exiting the vehicle after hitting the snow bank. As autopsy results confirm, neither of these shots struck Mr. Finicum. The question of who fired these shots has not been resolved. Upon learning this, and given the FBI presence on scene, I immediately contacted our Inspection Division which notified the United States Department of Justice’s Office of Inspector General which is currently investigating this matter.

Officials also released the video Cox shot. It’s a counterpart of the FBI’s video, which was filmed from a surveillance plane, and does a good job of capturing the broad outlines of the incident but little to illuminate the details. Cox’s video is also limited—it reveals some details about Finicum and the crash before he was shot, but it’s tough to tell what’s going on outside the truck.

The footage shows Finicum taunting officers during the first stop, when both vehicles were intercepted, holding his arms outside the window and telling them to go ahead and shoot him if they pleased but that he intended to go meet the Grant County sheriff in John Day. The passengers are heard complaining they don’t have cell service to get in touch with other people on the remote road. Then Finicum tells everyone to get down and guns the engine—unbeknownst to him, directly toward the roadblock.

“Hang on! Hang on!” Finicum says. Then comes the impact—and the second stop. He jumps out of the car and shouts, “Go ahead and shoot me!”

The people in the car scream as gunshots ring out and try to figure out what’s happening outside the car. There are sounds of explosions—possibly flash-bang grenades—and smoke starts to fill the car. The passengers still in the car can see the laser sights on guns dancing around the car. “I don’t dare get out, ’cause they’ll shoot me,” one woman says. The video then ends.

The four FBI agents were part of the bureau’s elite Hostage Rescue Team. As The Washington Post reports, the operators were shadowy and mysterious even to the state police working alongside them.

The revelations threaten to cast a new pall over the team. During the 1990s, the HRT was implicated in the two disasters at Waco and Ruby Ridge, where the government was universally acknowledged to have bungled standoffs. Those experiences were often cited as a reason for the FBI’s notably hands-off approach to the Malheur situation—keeping a distance, letting people come and go, and allowing the occupation to run for weeks. The general positive reaction to the standoff seemed to suggest a return to good graces for the HRT. The hiccups in the investigation point to what might be another blemish for the team—even as the rest of the occupation was resolved effectively.

Celebrity: The Obamas’ Smart Cultural Power

In July 2008, John McCain released an attack ad against Britney Spears and Paris Hilton. Well, against Barack Obama, too. The image of the then-senator from Illinois was juxtaposed with the two uber-famous blondes while a concerned narrator called Obama “the biggest celebrity in the world” who also happened to lack experience and would increase America’s dependence on foreign oil.

By that point Obama did indeed seem closer to the celebrity class, and more comfortably of celebrity status, than most previous presidential candidates. Will.i.am. had rounded up half of Hollywood to sing along to an Obama speech for a music video called “Yes We Can.” Oprah had given him her first political endorsement ever. And he’d recently toured Europe to great applause. McCain’s ad suggested there was something unseemly in all this human spectacle.

Why, exactly? Celebrities are celebrities, theoretically, because people like them. But Spears and Hilton, the bogeywomen of the McCain ad, embodied the ways that likability can curdle. The ad implied that Obama could turn out to be a Britney or a Paris. In the Britney scenario, he’d crack under pressure. In the Paris scenario, we’d get sick of his shtick. In either case, he’d be exposed as false.

Eight years later, whatever you might think of Obama’s job performance, his celebrity aura hasn’t seemed to hurt him much, if at all. The White House has become a bit hipper than it had been under previous presidents, with a number of young stars from the pop and hip-hop worlds stopping by (as well as a more typical array of venerated literary, musical, and artistic figures). The Obamas, in turn, have acted as performers themselves—slowjamming on Fallon, dancing on Ellen, impersonating Kevin Spacey—without triggering major scandal or outsized ridicule. In their engagement with pop culture, the Obamas have created the impression of edginess while also strategically exercising restraint. They’ve harnessed the entertainment-industrial complex without kowtowing to it.

The Obamas make culture work for them, not the other way around.

Never was that clearer than this week, when the White House hosted the cast of Hamilton and the first couple made their debut at the South by Southwest tech and music festivals. As America turns its attention to the election for their successors, we may be witnessing the final push in the Obamas’ cultural front. “This platform is so unique,” Michelle Obama told The Verge for a story about her social-media efforts that published on Monday. “We will never have it again. So we will spend these 12 months on every issue making sure we’re driving to the very end. We figure we want to drop the mic on some of this stuff.”

* * *

Hamilton is the Broadway smash that reinterprets the journey of America’s first treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, as a rollicking rap adventure largely cast with people of color. It’s also perhaps the strongest and most impressive claim Barack Obama can make to influencing pop culture. The first time the playwright Lin Manuel Miranda performed a Hamilton tune in public was at a 2009 White House poetry jam, where he tested out what would become the musical’s title song and opening number.

When introducing a performance from Manuel and other cast members in the East Room on Monday, Obama brought that fact up. He said that while his family is obsessed with Hamilton, Hamilton needed Obama to happen. “Not to take undue credit or anything, this is definitely the room where it happened,” he quipped. It was a classic Obama one-liner: a hip reference used for a dad joke, with the underlying punchline being less about the subject at hand than about Obama’s own power. Hamilton is the biggest musical in the world, but he’s not starstruck. He’s bigger than it. It owes him.

The truth is, they both owe each other some things. Hamilton has frequently been identified as the ultimate “Obama-era” cultural artifact, most substantively in a New Yorker piece by Adam Gopnik. On one level, there’s the fact that Hamilton’s portrayal of the founding fathers and mothers as black and brown takes on special significance when there’s a black commander-in-chief. “It is President Obama’s point about America’s open-ended and universally available narrative brought to life on stage,” Gopnik wrote.

On another level, Hamilton’s storyline spotlights the kind of oft-thwarted battle for progress—and to marry idealism with pragmatism—that has often agonized Obama’s supporters after hopey-changey 2008. Gopnik argued that Miranda had completed a long-brewing transition in historical interpretation among liberals from aligning themselves with Thomas Jefferson to aligning themselves with Hamilton:

... a Hamiltonian liberal is an ex-revolutionary who believes that the small, detailed procedural efforts of the federal government to seed and promote prosperity are the ideal use of the executive role. Triumphs of this kind, as the show demonstrates, are so subtle and manifold as to often be largely invisible—and are most often as baffling and infuriating to those whom the change is designed to serve as they are to those whom the compromises are meant to placate. [...] If Hamilton’s program could be reduced to a phrase, after all, it would simply be that the national government should try, directly or indirectly, to loan money to manufacturers. Obama’s efforts and triumphs in this direction have been, as Hamiltonian ones often are, obscured, but real.

Gopnik suggested that Miranda ended up offering this Obama-friendly message less by design than by intuition. If you look around at the major politically themed works of culture in the past seven years, you often find a similar focus on process, competence, and incremental change for the common good. Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln showed one of the most idealized presidents in bargaining mode; Zero Dark Thirty portrayed the defeat of Osama bin Laden as the result of scut work; even the cynical House of Cards has fun imagining a Democratic president murdering ideology in pursuit of concrete policy achievements. It’s not far-fetched to speculate that these are the sorts of works that result when Hollywood watches the charismatic force it helped elect labor unspectacularly, day after day, against gridlock.

Hamilton at the White House also stands as an example of the work that the Obamas have done to recognize hip-hop’s cultural centrality. Embracing rap has never been a politically neutral act, both because of lyrical content but also, many of the genre’s fans would argue, because of ingrained attitudes about race and class in much of the country. But Obama’s ’08 campaign involved the support of rappers and provided an iconic moment when Obama borrowed Jay Z’s “Dirt Off Ya Shoulders” move. In 2011, he invited the rapper Common to a White House poetry event, causing some backlash from conservatives despite the fact that Common is among the least controversial emcees imaginable.

A Washington Post column in 2015 by Erik Nielson and Travis L. Gosa argued that after the Common criticism, Obama backed away from rap, spotlighting no hip-hop in his 2012 campaign playlist and forgoing rap shows in the White House. This may well have been the case—an example of Obama’s caution about overdoing things when engaging pop culture. But in recent months, he’s shown his rap fandom again. Earlier this year, Obama invited Kendrick Lamar to the Oval Office after naming “How Much a Dollar Cost,” a deep cut on To Pimp a Butterfly, one of his favorite songs of 2015. Wale has performed at multiple presidential events. These gestures have gone appreciated in the rap world. On Instagram, the rapper Fabolous wrote:

Hip-hop used to be a political scapegoat, the black cat of America, the reason for everything wrong even while being the largest growing music and the corporate world getting rich off our style, jingles and consumers. We watched hip-hop become a universal language through all its backlash and ridicule. And Obama was the first President to even take pictures with our favorite artists, invite them to the White House, even drop lines in his speeches.

If there’s anything that underlines the idea of hip-hop as a newly universal language, it’s Hamilton—both the musical itself and its conquest of the Great White Way and the White House. To say Obama is responsible for the wider shift in America that has enabled Hamilton’s success would be incorrect, of course. He is a beneficiary of that shift, and he has in turn, subtly, helped it progress further. The best digital artifact to have come from the Hamilton cast’s D.C. visit is probably the video of Miranda freestyling based on cue-cards held by the president. Miranda, as is always the case, is frenetic, flustered, and brilliant. Obama puts in minimal energy, acting impressed but not too impressed. He knows what he’s giving and getting by simply participating. He only drops the facade for a moment, at the end: “You think that’s going viral? That’s going viral.”

* * *

It’s easy to forget that virality is a concept that barely existed in popular discourse prior to the Obama presidency: Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and Tumblr all either came about or grew to ubiquity in the past seven years. Celebrities of both the political and non-political sort have used these platforms to great success and to great accidental embarrassment. The Verge’s Michelle Obama profile this week offers a look at how the White House has tried to avoid the latter. At one point, the writer Kwame Opam asks Michelle to perform the Dab—Cam Newton’s famous touchdown move—on camera, with hopes of going viral. Hillary Clinton had done it on Ellen already, after all. But after some discussion with her team, Michelle declined the request on the grounds of “dabbing’s hazy connection to marijuana culture.” Maybe that’s a legitimate objection, or maybe it’s a front for some greater calculation about how much the First Lady should give and withhold from the public.

As the holder of no elected office, Michelle has, in the way of presidential wives before her, used her time in the White House on mostly non-partisan causes: helping veterans, reducing childhood obesity, encouraging college enrollment, and promoting education for girls around the world. She has no official budget to spend on these things, so she’s savvily instead cashed in on her celebrity to promote awareness. Athletes, actors, and major singers have put on exercise clinics, concerts, and fundraisers for the First Lady’s initiatives. In turn, pop culture has spontaneously reified her as the pinnacle of female badassery, most notably on Fifth Harmony’s hit “Bo$$.” The chorus: “Michelle Obama / purse so heavy getting Oprah dollars.”

Beyoncé rewriting and rechoreographing “Get Me Bodied” for a “Let’s Move” video distributed to schools across the country was a particularly deft move—and an example of yet another strategic partnership that subtly places the Obamas higher in the celebrity hierarchy than even the world’s biggest entertainers. Beyoncé provided the soundtrack for their first presidential dance; for the 2012 campaign, she wrote Michelle a fawning open letter and held an Obama fundraiser with Jay Z; she sang the National Anthem at the second inauguration. In return? When accused of exempting the Knowles-Carters from rules against traveling to Cuba, Obama laughed it off and the State Department provided the documents to show that no quid pro quo had taken place.

The latest Michelle Obama celebrity charm offensive is in service of her Let Girls Learn campaign, when she triggered a wave of spit-take headlines saying she was releasing a charity single featuring Missy Elliott, Kelly Clarkson, Zendaya, Janelle Monae, and other pop artists. When the song arrived online, it became clear that Obama herself was not actually on the song. Of course she wasn’t: The Obamas make culture work for them, not the other way around. In an essay for Lena Dunham’s newsletter, Obama said she didn’t sing on the track because she can’t carry a tune. But at the South by Southwest keynote panel where she sat alongside Elliott, Queen Latifah, the songwriter Diane Warren, and the actor Sophia Bush, she did sing a snippet of Boyz II Men’s “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday” when asked about having to leave the White House soon. The crowd not only whooped in delight—the other women on stage did.

The moment recalled what might be the out-and-out coolest moment of Obama’s presidency, when Barack crooned some Al Green onstage in the midst of a speech. The shock and the instant acclaim came in part from hearing the president sing so well. But it was also came from hearing him sing at all. “I’m so in love with you” he began, then stopped and grinned. Six words were all he’d give—an entertaining reminder that the president is not, despite occasional appearances, here to entertain.

Brazil’s Corruption Scandal Has It All

A federal judge in Brazil on Thursday of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to a Cabinet-level position.

Lula, who is currently ensnared in a billion-dollar corruption scandal, had been sworn in hours earlier as President Dilma Rousseff’s chief of staff following the controversial announcement of his appointment earlier this week. Rousseff, who succeeded Lula as president, was his hand-picked successor.

On Wednesday night, a prosecutor released dozens of recorded phone calls including one that appeared to show Lula was seeking to use his Cabinet post to shield himself from prosecution—a revelation that prompted the federal judge to issue an injunction against the appointment.

According to news reports, in one taped conversation on Wednesday afternoon, Rousseff told Lula she would send him his ministerial credentials “in case of necessity,” widely interpreted to be a reference to Lula’s potential arrest or detainment. (Earlier this month, Lula, who is the most prominent of the dozens of politicians implicated in the scandal, was taken in for questioning by police.)

The government argues the conversation merely meant Lula might not be able to attend the swearing-in ceremony and officials have promised to appeal the injunction against Lula’s appointment. Indeed, in a previous conversation, also taped, Lula is heard telling Rousseff he “would never enter government to protect myself.”

Lula’s alleged participation in a kickbacks and money-laundering scheme involves Petrobras, the crown jewel of Brazil’s state-owned enterprises. The illegal actions are alleged to have taken place largely during Lula’s presidency from 2003 until 2010.

Brazil remains in the throes of a deep recession and anti-corruption sentiment has frequently materialized in the form of national protests. On Sunday, more than a million people around the country took to the streets in record demonstrations where calls were made for Lula to be arrested and for Rousseff to resign.

This scandal, which threatens Brazil’s government, ironically harkens back to a quote delivered by Lula himself nearly 30 years ago.

“In Brazil,” he said, “when a poor man steals he goes to jail. When a rich man steals he becomes a minister.”

Listening to Montana

To the north, the first traffic light is 144 miles away.

To the south, the first traffic light is 92 miles away.

There are no traffic lights here in Chester, Montana.

View from the airport in Chester, Montana (Deb Fallows / The Atlantic)

This is how the musician Philip Aaberg introduced his hometown of Chester, Montana, in a short radio commentary he produced for KCRW a while back, along with his wife, Patty, and their son Jake.

Flying over the Bitterroot Mountains (Jim Fallows / The Atlantic)

A privilege of our American Futures journey is that, occasionally, we can fly our small propeller plane far, far away to places like Chester, Montana. Chester lies at the top of the country, 30 miles as the crow flies from the Canadian border. From even farther west, we flew over the Bitterroot Mountains, which then rolled away into the high plains, with fields of green, yellow, and gold. The rivers below us meandered. The rail tracks looked very important. The roads indeed didn’t need traffic lights. In the skies, there was not another plane in sight for hours.

Maya Lin’s “Listening Circle” in Chief Timothy Park, Washington (Jim Fallows / The Atlantic)

We had just spent some time along the Washington-Idaho border, to see one of the newly-finished Maya Lin installations for the Confluence Project, along the path of Lewis and Clark’s expedition some 200 years earlier than ours. And we were heading to the American Prairie Reserve in Northeastern Montana, to see the new rewilding of the American prairie with native bison, pronghorn antelope, and other animals. Chester was more or less on our way.

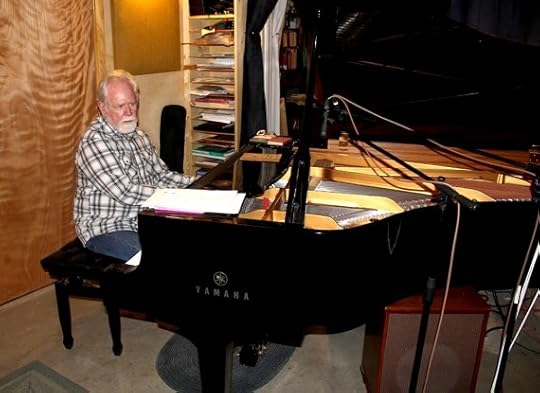

Our friends Phil and Patty Aaberg live in Chester. Phil is a musician—a pianist and composer with a collection of awards, performances, and collaborations that more than prove his bona fides to anyone who hasn’t had the good fortune yet to hear his music. Windham Hill Records, nominations for Grammies and an Emmy, and some 20 albums with names like From the Ground Up and Live from Montana.

Distance from Chester (Deb Fallows / The Atlantic)

After time on the east and west coasts, Phil and Patty moved to Chester, a town of about 1,000 people, to the house where Aaberg grew up, right across from his old school. Partly, they were looking for such a place to raise their young son (the older three were grown by then) and partly because, well, Montana always had a strong pull on Phil.

Back in the late 19th century, Chester was a stop for the steam engines of Great Northern Railroad to replenish coal and water. Homesteaders soon followed. Phil’s family has been there about a century. Already a serious music student as a young teenager, Phil would ride the train every few weeks to meet with his piano teacher in Spokane, a seven hour trip, or 10 if there were lots of stops.

Great Northern B&B and Aaberg’s music studio in a silo (Deb Fallows / The Atlantic)

When the Aabergs opened their Great Northern B&B, where we stayed with them, it doubled the number of lodging options for visitors and those just passing through. And then they opened another on First Street. Sometimes, people biking through the north will stop in Chester. Once, a biker stopped for a day, and ended up staying for a week, waiting to take delivery of some bike parts. It was one of those stories that you could imagine ending with something like, “And then he met my second cousin who runs the pharmacy, they fell in love, and he’s been here ever since.” That didn’t happen, but it was easy to believe it could have. Chester is that kind of town.

Landing over Chester, with airstrip at the far end of town (Deb Fallows / The Atlantic)

We flew into Chester’s tiny airport. It wasn’t unusual to find an airport there; some 5,000 small airports dot the country, a legacy of airstrips built for military pilot training around World War II, and then for civic and post office growth. Chester’s airport was even more convenient than most. When Phil heard our plane overhead, he could hop in his car with Jake, head the few blocks to the edge of town where the airport lay, and still have plenty of time left over to wait and see us land.

People who are from towns this small, this remote, and this beautiful grow up with a deep imprint of place on their lives, and for artists like Phil, on their work. I know this firsthand from my childhood in a small town on the shores of Lake Erie.

View toward the Sweetgrass Hills (Phil Aaberg)

In a formal interview he once gave, Aaberg talked about how this place—these northern plains and his hometown—has inspired the music he creates.

Sounds from Montana

Aaberg describes the early days of noticing music, when his mother and grandmother were choir directors at the Catholic Church. He heard a lot of music, including Gregorian chants. He recounts the first time, at 4 years old, when he ran home from church to the family piano to sound out a tune he had heard. He described the thrill of figuring that out all by himself, and recalling it vividly as the moment that he knew what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

When Aaberg is touring on the road, he builds in time to teach a little music to the schoolkids in the towns. He includes listening exercises, having the kids pause to just listen to the sounds around them for a whole minute. “Listening is the most important thing you can do,” he tells them. “If people in the world would listen to each other, the world would be a lot safer place.”

Time in Montana

Aaberg says, “I love this land. There is something about this country that really opens me up.” He talks about the amount of time and the quality of the time he spent in Chester. “When I was here, I was really here.” He talked about the relationship between his music and seeing the land here, watching the sky change, seeing the Sweetgrass Hills, watching the flights of birds. “All incredibly important to me,” he says, and a source of his inspiration.

Phil Aaberg at his piano in his studio (Deb Fallows / The Atlantic)

Phil built his studio, fittingly, from an old grain silo. He invited us in to look and listen a little while. He played some of the songs I knew; now that I had been in Montana, I recognized that they actually sound like Montana.

After we headed east to the American Prairie Reserve, I got an email from Phil. He said he was heading out to go camping in the Sweetgrass Hills. Lucky man. You can’t get to Chester, Montana, today, or probably even tomorrow. But you can bring a bit of Montana into your life through this music. You can listen here and here and here, and find more music here.

City of Gold and the Richness of the Melting Pot

“It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot think of one without the others,” M.F.K. Fisher writes in The Art of Eating. Jonathan Gold seems to agree. A mole he encounters is “as spicy as a novella and as bitter as tears.” A taco isn’t a dish so much as a verb—one long continuous motion from grill to dish to diner, preferably via a truck. Food writing isn’t service journalism, it’s cultural anthropology: a way of examining the manifold shades and textures of humanity without needing a Ph.D. or a passport.

So it’s no coincidence, perhaps, that the word “taste” describes both how humans perceive food and how we perceive culture. No food writer today seems to intuit this confluence better than Gold, the ostensible subject of Laura Gabbert’s new documentary, City of Gold. Gold is the Los Angeles Times’s restaurant critic, although that title implies a degree of white-tablecloth formality that doesn’t quite fit him—he is, as Andrew Zimmern states in the movie, one of the great democratizing forces of cultural criticism in the 20th century, proving that a roadside burrito can be as worthy of appraisal as a $200 tasting menu. As Gabbert follows Gold from hot-dog stand to strip-mall restaurant to a meeting at Momofuku, what becomes clear is that she’s using him as a lens to expose the richness of American culture, and the disproportionate role immigrants play in sweetening the melting pot.

Not that Gold himself isn’t an extraordinary subject. The movie premiered at Sundance in 2015, a week after Gold publicly abandoned his career-long attempts to remain anonymous, citing the impossibility of keeping your face a secret in the age of Instagram, as well as a belief that “the game of peekaboo is harmful both to critics and to the restaurants they write about.” This is just as well, because on camera he’s a resplendent figure with a mane of graying strawberry-blond hair, a freckled face, and keen eyes that light up when he peers through the window of a taco truck. “You’re not going to find cooking like this anywhere but L.A.,” he explains.

Gold grew up in South Central, and the movie reveals glimpses of his youth—the meticulous hierarchy regarding the Jewish deli his family shopped at, his time playing the cello in a punk band, how he fell into the exploration of ethnic cuisine because he was bored in an early job as a proof reader. But Gabbert seems less interested in Gold the person than Gold the critic, and his extraordinary influence as a champion for off-the-radar restaurants and chefs in Los Angeles. (For extra insight into the former, read Dana Goodyear’s 2009 New Yorker profile of Gold, which includes an anecdote about how he once burst into tears in a restaurant in an anxious fit after spending the day on a mission to sample the city’s espresso.) Gold and L.A., she proposes, are an almost impossibly perfect match of city and surveyor, where Gold, like Reyner Banham before him, maps out the complexities of its ethnic enclaves, one meal at a time.

As he drives around in his oversized Dodge truck, Gold points out highlights on the culinary map—a joint where they put boiled ox penis in your pho here, an “art-directed take on Korean street food” there. He stops to greet a man whose hot-dog spot has closed, but who continues to hawk butterflied dogs from a cart right outside. Gabbert interviews Ludo Lefebvre, whose face becomes cement-tight, and who starts berating a sous chef when he sees Gold sit down at a table. And, more tellingly, she talks to Genet Agonafer, an Ethiopian chef whose son funded her restaurant with loans he took after finishing medical school, and whose business was bleeding money until Jonathan Gold reviewed it. Suddenly, she says, “I could not cook the doro wat fast enough.”

Food, he seems to believe, is simply what keeps us alive; cooking is what makes us human.

Gold clearly has an extraordinary palate, but his interest in food comes across in the movie as almost abstract—you get the sense that it’s simply a vehicle for accessing his real subject, which is people. As a young reporter, he explains, he learned that if you try and talk to strangers in the street, they shut down, but if you strike up a conversation in the context of having a meal, you can more easily connect. He visits a restaurant four or five times before he writes a review, explaining that his mission is to achieve “exhilaration, infatuation, and, if you’re really lucky, understanding.” Food, he seems to believe, is simply what keeps us alive; cooking is what makes us human.

As a portrait of an artist, Gabbert’s film is moving, intriguing, and fragmented. There are hints at a larger narrative reveal that never unfurls: mentions of frequent writer’s block, missed deadlines, editors explaining how they have to psychotically stalk him to get him to finish a story. Everyone from David Chang to Ruth Reichl to Calvin Trillin praises his writing at length, but few seem able to offer much insight into what, beyond food, makes him tick. But as a portrait of a city, and a rapidly evolving moment in culture, City of Gold is endlessly fascinating. Gold’s Los Angeles is a vivid microcosm of the American Dream, where first-generation immigrants can build successful businesses—and raise their children to be doctors, bankers, maybe even food writers—by replicating the tastes and traditions that attach them to home.

You get the sense that he’s writing not for the millions who read his reviews, but for those who don’t. City of Gold, whose scenes are accompanied by gorgeous original music by Bobby Johnston that conveys a sense of the extraordinary diversity of L.A., captures the spirit of a vast metropolis of interconnected souls finding communion through food. “We are all citizens of the world,” Gold explains before the movie’s closing credits. “We are all strangers, together.”

The Long, Thorny Path to Calling ISIS 'Genocidal'

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry announced Thursday that the State Department had found ISIS responsible for genocide in areas it controls.

“My purpose here today is to assert in my judgment, Daesh is responsible for genocide against groups in areas under its control including Yazidis, Christians and Shiite Muslims,” he said at the State Department, referring to ISIS by one of the other names by which it is known.

The move has been a long time coming.

In August 2014, as the U.S. was launching its first strikes against ISIS fighters in Iraq, Kerry justified the escalation under the theory that ISIS’s activities bore “all the warning signs of genocide.” If American actions were meant to pre-empt such genocide, they apparently failed. In the past few months, ISIS’s campaign against the region’s ethnic and religious minorities, including the persecution of Assyrian Christians and Yazidis, has been formally declared “genocide” by the European Parliament and the United States National Holocaust Museum. (The former of these designations is particularly noteworthy since it was both unanimous and the first time a conflict had been categorized as a “genocide” in real time.)

Earlier this week, the U.S. House of Representatives joined the call, voting 393-0 to designate Islamic State crimes “genocide.” It’s the third time the House has attached the label to an ongoing crisis. As The Washington Post noted, “Roughly 30 percent of the [non-binding] resolution’s 218 co-sponsors are Democrats.”

So why didn’t the White House and State Department immediately follow suit? It’s complicated. Kerry, once wary of a potential genocide, appeared to have become wary of characterizing what’s come to pass in Iraq and Syria as genocidal.

“I have asked our legal department to evaluate, to re-evaluate actually, several observations that were circulating as part of the vetting process of this issue,” he told the AP earlier this week, adding that a judgment would come “very, very soon.” Ultimately, the designation came Thursday, in line with a Congress-set March 17 deadline for a declaration.

Still, it’s unclear what, if any, legal obligations the designation compels. That ISIS is a non-state actor is a complicating factor since the 1948 Convention on genocide, in the words of one expert, is “predicated on the notion that only states commit these crimes.”

Any decisions on what steps to take against ISIS would be influenced by the ultimately disastrous U.S.-led invasion of Libya in 2011 that was also undertaken on the grounds that it would prevent a massacre. It also comes nearly a year after Congress formally neglected to take up an authorization of military force proposal that would have formally granted (and potentially constrained) President Obama’s ongoing bombing campaign against Islamic State targets—a campaign that has since spread from Iraq and Syria to Libya.

Nevertheless, the House resolution not only put public pressure on the White House to act, but also advanced some political aims. Linking “genocide” with ISIS provides a broader rationale to step up the fight against the terrorist group, which a number of lawmakers and politicians have lobbied for, and, as John Hudson at Foreign Policy notes, would “also give momentum to humanitarian advocates arguing for a more welcoming refugee policy—an issue touted more often by Democrats.”

Obama, given his aversion to raising what he sees as excessive alarm about the terrorist group, doesn’t seem likely to bite. References to this line of thinking can be seen in April’s cover story for The Atlantic, in which Jeffrey Goldberg details the president’s hesitation to emphasize the dangers of ISIS, particularly in the wake of its attacks on Paris last November.

But he [Obama] has never believed that terrorism poses a threat to America commensurate with the fear it generates. Even during the period in 2014 when ISIS was executing its American captives in Syria, his emotions were in check. Valerie Jarrett, Obama’s closest adviser, told him people were worried that the group would soon take its beheading campaign to the U.S. “They’re not coming here to chop our heads off,” he reassured her. Obama frequently reminds his staff that terrorism takes far fewer lives in America than handguns, car accidents, and falls in bathtubs do. Several years ago, he expressed to me his admiration for Israelis’ “resilience” in the face of constant terrorism, and it is clear that he would like to see resilience replace panic in American society.

Thursday’s announcement by Kerry indicates that the president’s feelings about ISIS notwithstanding, the terrorist group will remain at the center of U.S. counterterrorism strategy for at least the immediate future.

Related Videos

Graeme Wood sits down to discuss "What ISIS Really Wants," his cover story about the ideology behind the Islamic State.

The End of SeaWorld's Orca-Breeding Program

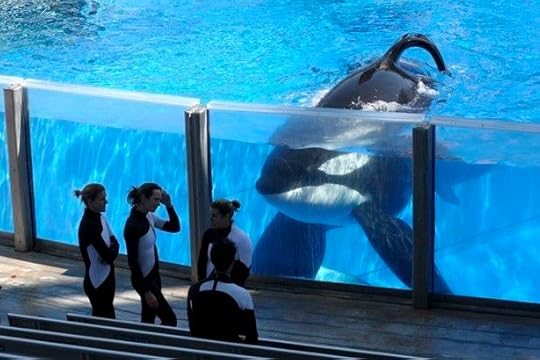

There’s big news this morning from SeaWorld:

Breaking News: The #orcas currently in our care will be the last generation of orcas at SeaWorld. Learn more: https://t.co/DxxAE7p6Ci

— SeaWorld (@SeaWorld) March 17, 2016

The move comes, in part, because of the backlash directed at the theme park following Blackfish, the 2013 documentary that alleged that orcas are suffering in confinement at the water parks. Subsequently, attendance at SeaWorld dropped and the company faced continued protests. The controversy prompted the resignation of Jim Atchison, SeaWorld’s CEO, in 2014.

In a statement on its website on Thursday, SeaWorld acknowledged that “[s]ociety is changing and we’re changing with it.”

Twenty-three of SeaWorld’s orcas were born in captivity at the theme park; a few have spent nearly their entire lives in human care. SeaWorld stopped the live capture of orcas from the wild decades ago.

Under the new plan, the orcas will spend the rest of their days at SeaWorld’s facilities because, the theme park said, “[t]hey could not survive in oceans to compete for food, be exposed to unfamiliar diseases or to have to deal with environmental concerns—including pollution and other man-made threats.”

Joel Manby, SeaWorld’s current CEO, said the organization would now “increase … [its] focus on rescue operations.”

SeaWorld worked on its policy with the Humane Society of the United States, which called the announcement “a major step forward toward a humane economy.”

Thursday’s announcement follows one in November in which SeaWorld announced it would end its “theatrical killer whale experience” at its flagship theme park in San Diego.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower