Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 213

March 12, 2016

Down the Rabbit Hole: Alice in Wonderland’s Influence on Video Games

The bed is on the ceiling. The faucet is dripping up. A fish floats above you, bleating sonorous, pun-filled pronouncements. In the center of the room is a tiny door; on the table, a potion. “I’m constantly observing my declining behavior as if through a looking glass,” the protagonist mutters to himself.

I think you might know what happens next.

Why do video games love Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? Again and again they return to it as a reference point, regardless of genre, regardless of style. The scene I just described comes from The Slaughter: Act One, a point-and-click adventure game released in January that mixes noir with Victorian London, much as 1998’s Grim Fandango did with Aztec mythology. You play as Sydney Emerson, a private eye who likes to mutter ironies to himself between hitting the pub and pursuing … Jack the Ripper. The game arguably has more reason than most to toss out an Alice reference like it’s no big deal; it takes place, after all, in the historical setting that begat Alice in the first place. And yet, the dream sequence I’ve just described—referred to as “Lynchian” by its creator, because the only thing games love as much as Alice in Wonderland is Twin Peaks—is less immersed in the history of Victorian literature than in the history of video games themselves, which are rife with Alice moments just like it.

More From Our Partners

What Can Alice in Wonderland Tell Us About Gamification?

The Dismal Western Front of The Grizzled

Timruk Explores the Layers of Historic Violence Beneath Its Beauty

When things get druggy in 2012’s Far Cry 3, the game brings in Alice as epigraph and intertitle; the action stops and lines from the book pile on top of each other in that blocky blue font. When things get almost unmanageably disorienting in the 2014 first-person exploration game NaissanceE—a game almost as devoid of words as it’s devoid of color—you find yourself running through the same hallway over and over again, getting tinier and tinier as the camera is knocked askew. Alice is the very first world in 2002’s Kingdom Hearts, and the world that arguably sets the tone for all the illogical encounters after it—every Heartless derived from the Queen, every level subject to sudden and arbitrary reversals of the rules. In the Shin Megami Tensei series, Wonderland is sometimes a dungeon and Alice is sometimes a boss. In The Elder Scrolls series (especially 2007’s The Elder Scrolls IV: Shivering Isles), the books creep in via Sheogorath, the Daedric Prince of Madness, lord of his own wonderland where the laws of the mind take hold.

There are games that are based completely in Alice’s world: American McGee’s Alice (2000) and Alice: Madness Returns (2011)—sequels to the books that star a grim, dark Hot Topic version of Alice herself—as well as direct adaptations of the story on many different gaming platforms, going all the way back to Commodore 64. And yet, so much more often, the books seem to show up in games that are not about them, and in much more managed ways—as interludes, interpolations, allusions, shoutouts. A lot of games have a tendency to invoke them at penultimate moments. “Down the Rabbit Hole” is the second-to-last mission in 2011’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3; “Deeper into madness” is the second-to-last major section of 2014’s NaissanceE, a brutal kinetic gauntlet before the endless stasis of the desert. In The Slaughter, Sydney has his Alice dreams. But they’re premonitory, arriving before something horrible happens in reality.

The literary theorist Jonathan Culler once maintained that when poets begin with an apostrophe, “O whatever!” (e.g. “O wild West Wind”), they’re doing nothing so much as implicitly inserting themselves into the canon of every other big-name poet who begins poems with an apostrophe; they’re adding an aesthetic hashtag, a tacit marker of cultural seriousness. A lot of Alice references in games work in kind of the same way. Games like Madness Returns and Far Cry invoke Alice to reach for a marketable tone, casting themselves into a higher plane of mordant cynicism, as if to say, “We’re dark, man, like this famous children’s story about death and drugs.” Other games (like NaissanceE and The Slaughter) seem to invoke it at least in part because of its highbrow baggage—because to reappropriate Alice is to do something that avant-garde movements were doing throughout the 20th century, from modernism and surrealism and Dada to ’60s drug culture, psychedelic rock, and Jefferson Airplane (and to a lesser extent, 1999’s The Matrix).

A lot of Alice references in games add an aesthetic hashtag, a tacit marker of cultural seriousness.

Beloved cultural touchstones are beloved cultural touchstones, of course, and if people tend to invoke them it’s probably because they’re beloved. At the same time, I think it’s a lot like how puzzle games that want to be taken seriously as aesthetic experiences and intellectual achievements—2012’s Fez, this year’s The Witness, NaissanceE once again—have an extremely high chance of invoking the inscrutable black monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It profits the creator of something new and strange to be in good intertextual company, to be among the heavy-hitters. At least until you make too many Moby-Dick (1851) references and it gets a little stupid.

But there’s a much better reason for games to invoke Alice, and I think it’s a reason that ultimately underwrites their abiding tendency to do so: because Alice is itself a game. Alice might very well be the original attempt to resolve the “ludology vs. narratology” debate that game critics and designers have been trying to work through for the last 20 years—the original attempt to make storytelling game-like and gameplay a form of narrative experience.

The textual chessboard at the beginning of Through the Looking-Glass (1871) makes this crystal clear, establishing the whole book as a game—or maybe a metagame—that unfolds through the act of reading, each chapter corresponding to a “move” by Alice’s profoundly overwhelmed pawn. But the original is also fundamentally gamelike, not only in the way it contains games (e.g. the wacky croquet match between Alice and the Queen) but in the way it invites the reader to play language games at every turn. Just as Alice is asked to solve riddles by seemingly every vulgar, indignant animal she encounters in that topsy-turvy world, Alice’s author Lewis Carroll implicitly asks the reader to puzzle through the linguistic inversions, looking not necessarily for meaning—as Alice says about the poem “Jabberwocky,” “It fills my head with ideas—only I don’t know what they are!”—but for logical, or at least ludic, consistency.

It’s hard to see Alice clearly through the Genius-like cloud of its annotators and 20th-century interpreters, who often associate it with things that aren’t game-like at all—dreams, trips, the formlessness and illogicality of altered states—or even turn it into a straight-up drug allegory. But there’s an alternate tradition of commentators who attach themselves to the hard precision of its weirdness, and the clearly defined rules of its textual engagement. Like his fellow Victorian “nonsense poet” Edward Lear, Carroll (also known as Charles Dodgson) was a professional logician, and the genesis of his project can be traced not only to a deep love of order—apparently he kept an exhaustive database of all his incoming and outgoing letters for 37 years, totaling 98,000 entries by the time he died—but also to his proclivity for making word games for children. As the critic Elizabeth Sewell put it in her classic 1951 study The Field of Nonsense:

Nonsense as practiced by Lear and Carroll does not, even on a slight acquaintance, give the impression of being something without laws and subject to chance, or something without limits tending towards infinity.

On the contrary, it’s “a carefully limited world, controlled and directed by reason, a construction subject to its own laws.” The challenge of the books is to see those laws in any kind of clarity, and it’s a challenge that yields apparent (if fleeting) win-states. When the Cheshire Cat says, “You see a dog growls when it’s angry, and wags its tail when it’s pleased. Now I growl when I’m pleased, and wag my tail when I’m angry. Therefore I’m mad,” it’s ridiculous. But it’s also a perfect inversion, as beautifully self-enclosed as a square on a sheet of graph paper. To be “mad” is to be at the other end of a “therefore,” a clockwork determination. To be sane is to see what madness is and simply do the opposite.

What is nonsense, anyway? In the realm of language, the term designates a lack of meaning: words and phrases arranged into shapes and sequences that bear no definite (or at least obvious) semantic fruit. Yet that very definition puts emphasis on the “arrangement” part, which is what nonsense literature tends to have in paradoxical abundance: As the academic Hugh Haughton observed in 1988, “Nonsense is more shapely, more brazenly formalized and patterned than other kinds of language—not the reverse.” Nonsense is language unshackled from semantic reference and hyper-arranged according to some other internal system—probably one more organized, since meaning is itself so messy and infinite and prone to change over time. The result is a piece of language that’s gamelike almost by default, since games, in Sewell’s view, have three distinct components:

1. A desire, on the part of the player, to play;

2. Objects for the player to manipulate: chess pieces, cards, croquet balls, Companion Cubes;

3. A constrained field of possibility: a board, an arena, a battle, a level.

Nonsense invites sense-making; we feel a drive to crack the code. At the same time, it strips words of their usual meaning and context, making them manipulable, movable, in ways they weren’t before—hence all the puns in Alice, which allow words to move in a completely different direction (e.g. the “tale” of the mouse that Alice encounters early in Wonderland, both a piece of text and a piece of its body). And nonsense happens within its own frame, in a special field: a field of absurdity but also liberating possibility, enabled by conceptual constraint. Every page offers a new Zelda room full of blocks, levers, items, and switches, with no particular door to open. Reading becomes playing, no matter how fast you proceed.

Perhaps Alice is still rooted in the stuff of the subconscious, dredged up from a dark and merciless place beyond the light of reason. Theorists of nonsense tend to maintain nonetheless that its “nonsense” is opposed to dream-logic rather than the same thing—a way of containing and managing the disorder of the mind rather than giving it total, all-encompassing freedom. Games particularize the world, breaking it into manageable chunks. Video games do this with even greater intensity, bound as they are to the binary architecture of computers; the most realistic games are also the ones that most visibly abstract the real into manipulable units and blocks, like the wooden pallets in 2013’s The Last of Us. You can’t play a game unless it has objects you can control.

The disorder of dreams, by contrast, in Sewell’s view, offers nothing less than the prospect of everything being unmanageable and all-consuming—the prospect of the self or the mind being the thing “played with,” in a game far beyond its control. It would be wrong to say that there’s nothing dream-like about Alice, since the story takes place explicitly in a dreamscape. But it has a way of managing that dreamscape that staves off the most destabilizing qualities of dreams themselves. It divides them so that we might conquer them, even in moments of profound disorientation. “The game of Nonsense may, then, consist in the mind’s employing its tendency towards order to engage its contrary tendency towards disorder,” Sewell writes, “keeping the latter perpetually in play and so in check.”

Alice lives on in every game that uses Alice—or anything else—to make madness recognizable, to give it a face and a name.

Games often invoke Alice as a way of introducing disorder, a way of subverting their own carefully designed world-logics at the nadir of the player’s journey, when things get darkest before the dawn. Before its Alice chapter, NaissanceE works like any other first-person exploration game; you know the height and length of your jump, the speed of your walk, the general direction of your journey—forward and down, forward and down—even as the game impedes your path with labyrinths. In the Alice chapter, all bets are off; basic truths like gravity and perspective stop working the way they’re supposed to. And yet, I can’t help feeling that the very invocation of Alice in moments of despair like this is inevitably a way of keeping them corralled, contained, bound within a limited field of possibility. Things get weird in NaissanceE, but without an Alice reference they would be almost unimaginably weirder: The reference provides an implicit intertextual instruction manual, a way of navigating and understanding the disarray.

Things get weird in The Slaughter, but when Alice shows up, the weirdness becomes almost reassuring in its predictability, its containment. We find ourselves in a world already framed and divided by its ties to Wonderland. Its rules are strange—but there are rules. In this way, almost every game that invokes Alice as a reference point is true to the source material whether it wants to be or not, given that the source material is precisely about arranging disorder into manageable chunks, using play to contain the unbearable. Alice lives on in every game that uses Alice—or anything else—to make madness recognizable, to give it a face and a name.

VR is a realm of endless promises, and one of the things it promises is to give us a new breed of Alice game. The upcoming A.L.I.C.E. VR, yet another first-person game with explicit ties to the books, seems to follow NaissanceE by invoking them not only as a reference point but as a kind of template for the entire genre. You, like Alice, are wandering—this time on uncharted alien planets. Things are weird, and you can’t quite discern why from your limited, small perspective; the laws of reality are subject to sudden abrogation. I don’t doubt that it will be disorienting. Nor do I doubt that it will be a lot like Alice in Wonderland, even if it has nothing in particular to do with Alice in Wonderland: Not only because it is a game, but because it needs to be one.

This post appears courtesy of Kill Screen.

March 11, 2016

Libya, ISIS, and the Flow of Foreign Fighters

The UN Security Council is worried about Libya—and rightly so. As we noted in February, the country has seen a doubling of Islamic State forces in recent months, and ISIS has expanded its control of territory, including Sirte, the home city of deposed leader Muammar al-Qaddafi.

In a UN-issued report this week, the Security Council noted the Islamic State’s growing capacity, which has been buttressed by a flow of foreign fighters from places like Sudan, Tunisia, and Turkey. The development hasn’t gone unnoticed by the United States, which last month killed dozens of ISIS fighters (and two Serbian hostages) in airstrikes on a training camp.

Ironically, the Libyan branch of ISIS, which grew largely from local militias in the failed state, is now promoting itself as the most credible defenders of Libya from outside forces, even as it absorbs fighters from abroad.

“ISIL has been spreading a nationalistic narrative,” the UN report noted,

“portraying itself as the most important bulwark against foreign intervention.”

In the vacuum left by the U.S.-led intervention, the United Nations and a host of countries have been pushing Libya’s two governments and myriad competing militias to put aside their differences and help stabilize the country and its economy. Earlier this year, the head of Libya’s national oil company estimated the country had lost nearly $70 billion in potential revenue from petroleum exports because of the fighting.

If there’s a tiny, less dim note in the UN’s findings, it’s that while ISIS is certainly disrupting Libya’s ability to export oil, the group has not yet been able to profit off of Libya’s reserves.

“While ISIL does not currently generate direct revenue from the exploitation of oil in Libya, its attacks against oil installations seriously compromise the country's economic stability,” the report added. “Libyans have increasingly fallen victim to the terrorist group’s brutalities, culminating in several mass killings.”

Japan’s Moment of Silence

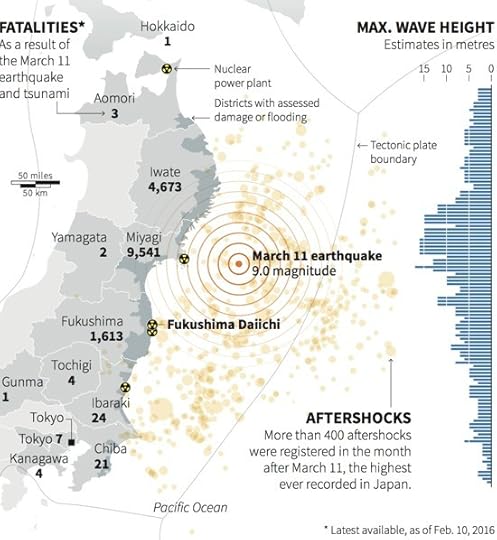

Japan paused at 2:46 p.m. local time to mark the fifth anniversary of the earthquake and tsunami that devastated the country in 2011.

More than 18,000 people died or went messing after a 9.0-magnitude quake off the northeastern coast of Japan, one of the largest in recorded history, triggered waves as high as 130 feet. The disaster also triggered a historic series of meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

Japan’s Earthquake and Tsunami

Reuters

More than 180,000 people are still displaced from the Fukushima region and the coast, including many who refuse to move back. Last month, we noted that Japan’s population has shrunk by nearly a million people over the past five years, impelled in large part by a low birthrate and a stringent immigration policy. Most notably, however, the Fukushima region posted a net loss of 115,000 people in the census figures.

Appropriately, Friday’s major memorial ceremony in Tokyo struck a somber note and also emphasized that the grief and trauma of the disaster are still deeply entrenched.

“Many of the people affected by the disaster are aging, and I worry that some of them may be suffering alone in places where our eyes and attention don’t reach,” said Emperor Akihito at a ceremony with survivors and Japanese officials.

In the eastern town of Rikuzentakata, where 1,700 residents went missing after the tsunami, religious services were held at a Buddhist temple that lost nearly 50 of its members.

“In form, perhaps reconstruction might happen, but in terms of recovering from the scars of the heart...’’ the temple’s chief monk told the AP, “I think there are some who might never heal.”

For more on the earthquake and tsunami, my colleague Alan Taylor has published a compelling series of photo collections documenting the tsunami’s unfolding and the recovery efforts as well as photographs from two weeks later, six months later, one year after, two years after, and an interactive feature with images of sites before and after the disaster.

Will Trump's Campaign Manager Face Criminal Charges?

Since his campaign manager was accused of assaulting a Breitbart reporter, Donald Trump has taken his case to the court of public opinion. Now, Corey Lewandowski, the accused staffer, may have to take his case to criminal court as well. Michelle Fields has filed a police report about the incident in Jupiter, Florida, the town’s police department confirmed in a statement. The news was first reported by the Independent Journal Review.

Related Story

Fields says she was grabbed and yanked out of Trump’s way Tuesday night as she tried to ask him a question at a post-election press conference. Washington Post reporter Ben Terris witnessed the incident. But the Trump campaign suggested Fields was lying and had fabricated in the incident. The Brietbart reporter, upset by the denials, then tweeted a picture of her bruises.

Trump again escalated his game of brinksmanship Thursday night after the Republican debate. “Perhaps she made the story up. I think that's what happened,” he said. Lewandowski, meanwhile, tweeted, “You are totally delusional. I never touched you. As a matter of fact, I have never even met you.”

Lewandowski’s alleged rough handling of Fields is one of two disturbing incidents of violence at Trump events in the last week. On Wednesday in Fayetteville, N.C., an attendee sucker-punched a protestor who was being removed by police and later told Inside Edition, “Next time, we might have to kill him.” There was near-violence outside that rally as well, as I reported.

Trump has gone to war with prominent media outlets and won before—most prominently Fox News, with which he has developed a love-hate relationship. But the Fields case is particularly bizarre because of the close relationship between Breitbart and the Trump campaign. The conservative outlet has been a cheerleader for Trump. In a recording obtained by Politico, Fields said just after the incident, “Yeah, I don’t understand. That looks horrible. You’re going after a Breitbart reporter, the people who are nicest to you?”

The fracas has riven Breitbart, with some staffers criticizing the Trump campaign, including its CEO. Yet on Friday, the site published a story suggesting that Fields, its own reporter, and Terris had incorrectly identified Lewandowski as the perpetrator. The Trump campaign released a somewhat nonsensical statement, written in the first person but without attribution, and a link to the Breitbart article alleging misidentification:

The accusation, which has only been made in the media and never addressed directly with the campaign, is entirely false. As one of the dozens of individuals present as Mr. Trump exited the press conference, I did not witness any encounter. In addition to our staff, which had no knowledge of said situation, not a single camera or reporter of more than 100 in attendance captured the alleged incident.

Now that’s one more question for the Jupiter police to sort out.

Is McDonald's Responsible for Its Franchise Workers?

An administrative law judge in New York City this week heard the first arguments in a case that has potential to reshape how workers fight for higher wages with giant franchisors like McDonald’s.

Specifically, the case deals with workers from five states (California, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana), at 29 locations, who say McDonald’s fired or threatened them after they joined a national day of fast-food employee protests asking for better pay in November 2012.

At issue is the nature of the relationship McDonald’s has with workers employed by its vast network of franchises. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a government agency whose job it is to investigate and remedy labor disputes, argued on Thursday that McDonald’s is ultimately responsible for the workers because of the extent to which it controls an individual franchise’s operations, down to when bathrooms should be cleaned and where food should be placed on the counters.

McDonald’s and its franchises disagree, calling the NLRB’s interpretation of the relationship “radical and unprecedented.” A ruling by administrative law Judge Lauren Esposito would decide whether McDonald’s is liable for violations of labor law at its franchises nationwide. A win for the workers would set a precedent for the fast-food industry, and possibly the franchise industry in general, because it would make corporate headquarters liable for the employees who work under their banners.

That hasn’t happened before. Until recently, it was the franchise owners who were responsible––and thus liable––for the employees behind the fry cookers. But slowly this has changed.

The U.S. has more than 14,000 McDonald’s locations, and it says 70 percent of its American employees are either women, or people of color. In fact, McDonald’s is often praised for its diverse workforce. The fast-food industry, as a whole, employs a disproportionate amount of black or Latino workers when compared to their share of the U.S. population. And the median pay for bottom-level fast-food jobs was $8.69 an hour, according to a University of California, Berkeley, study. This is why the fight for a $15 minimum has often been cast as not only a struggle to help the working poor, but to help the disproportionate amount of people of color who work in fast-food.

After the November 2012 national protests (The New York Times called it “the biggest wave of job actions in the history of America’s fast-food industry”) some McDonald’s workers who participated or tried to organize unions said they were later fired, warned against organizing, or even scolded for participating in rallies. The Service Employees International Union filed complaints on behalf of the workers with the NLRB. But instead of filing complaints against each franchise, as has been customary since the Reagan era, the NLRB’s lawyers named the McDonald’s Corporation as the responsible party, calling it a “joint employer.”

That phrasing is important. In July 2014, the NLRB’s general counsel said McDonald’s headquarters qualified as a joint employer because of how much it controls the way a franchise works. Then in 2015, another NLRB ruling broadened that interpretation further.

This was a reversal of the board’s Reagan-era interpretation of the standard in which a parent company had to show “direct and immediate” control over the employees of a franchise in order to be considered a joint operator. That created an insulating wall between the franchise owner and corporate headquarters. If workers unionized, they’d have to negotiate not with corporate, but with the many disparate franchises. But a change in that standard means proving McDonalds––or any corporation––has enough control over its franchises to be considered a joint employer became a lot easier.

Jamie Rucker, the lead lawyer for the NLRB in the McDonald’s case, said Thursday in court that top corporate staff tell franchises how to train employees, lay out employees’ job descriptions, and recommend how long they should spend on each task.

“The level of control this gives McDonald’s over its franchisees is very fine-grained and specific,” Rucker said.

Corporations like McDonald’s, as well as the franchises, are upset with this new logic.

“Millions of jobs and the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of independent franchise small businesses are now at risk due to the radical and unprecedented nature of this decision,” Steve Caldeira, the president and CEO of the International Franchise Association, said in a statement after the 2014 ruling. “Ruling that franchises are joint-employers will be a devastating blow to franchise businesses and the franchise model.”

Advocates of the new interpretation saw it as a chance to hold accountable––and to bargain with––corporations that had pulled the levers from behind a curtain, but were impervious to suit or negotiation.

“McDonald’s can no longer get away with reaping all the benefits and the profits while saddling their franchises with all the risks and the costs,” Micah Wissinger, the lawyer who brought the 2014 case to the NLRB, told The Washington Post at that time.

A win in this case would mean that cashiers and cooks could potentially address their grievances all the way up to the top. It would also mean fast-food workers in unions could have precedent to negotiate directly with headquarters.

But a ruling will probably not be made for years, Gary Burtless, a labor market policy researcher at the Brookings Institution, wrote me. In many cases, he said, a wealthy corporation can pay lawyers to help delay a decision. Meanwhile, workers would get no financial recompense while they await a decision.

The consequences of such a delay could be enormous: A change of political party in the White House may mean a change in the NLRB. And if the NLRB changes sufficiently that it comes around to McDonald’s point of view, workers will have little recourse left.

Hillary Clinton Turns Up the Heat in North Carolina

DURHAM, N.C.—The race for the Democratic presidential nomination was heating up at Hillside High School Thursday afternoon.

Not metaphorically—all indications suggest Hillary Clinton will win handily on Tuesday—but literally. With the mercury nearing 80 and thousands of Clinton fans packed into the Hillside gym, it was already warm. Then, with the candidate about to speak, someone turned off the roaring ventilation system so Clinton could be heard. Soon there began a slow but steady procession of people being helped out by EMTs after getting dizzy: an older white woman, somewhat heavyset, decked out in Hillary stickers; a man in a leather Uncle Sam hat that was an awesome fashion statement but in retrospect not ideal for the temperature.

With Florida and Ohio both voting on March 15, the North Carolina primary has taken a back seat to those larger, more decisive contests. Since its debacle of a loss in Michigan on Tuesday, the Clinton campaign has begun focusing on delegate counts rather than winning states. Her goal in North Carolina was to run up the score, securing as many delegates as she could here to offset close races, and potential losses, in Ohio and Illinois.

In 2008, the Old North State voted much later, in May, and Barack Obama’s victory was one of the final blows to Clinton’s bid for the nomination—brought on, in part, by black voters, who went more than 20-1 for Obama, according to exit polls. This time around, Clinton is looking for those same African American voters to buoy her against Sanders.

That’s why Clinton came to this historically black high school for a rally that was much more about getting out the vote than winning it. She was also joined by a roster of prominent local black politicians—Mayor Bill Bell, North Carolina House Democratic Leader Larry Hall, and U.S. Representative G.K. Butterfield, who chairs the Congressional Black Caucus. Over and over again, speakers emphasized the importance of getting to the polls. No one in attendance could have escaped without the mantra of “March 12”—the final day of early voting in the state—being drilled into their heads.

It’s another example of Clinton’s ability to draw on deep and long relationships with black Democrats, a resource that proved vital to her in South Carolina and other deep South states, where African Americans make up a huge portion of the Democratic electorate.

Clinton delivered a whole platter’s worth of red meat for the audience, taking aim at national Republicans, the state GOP, and Bernie Sanders.

“I am not a one-issue candidate because this is not a one-issue country,” she said, a standard line against Sanders. And she won hearty cheers when she attacked Sanders for voting for a 2005 law that granted gun manufacturers immunity from lawsuits by shooting victims.

But most of Clinton’s speech was spent praising public education and bashing the state’s Republican leadership. Since taking control of the state legislature in 2012, the GOP has enacted a full slate of conservative policy changes.

“There should not be a public school in this country where any person would not want to send a child,” she said. “Look in a mirror and say, would you send your child or grandchild to this school? And if the answer is no, do something about it!”

Clinton said that when her husband, then-Governor Bill Clinton, appointed her to lead an overhaul of Arkansas schools in the 1980s, she looked to North Carolina as an example, but said the system had been undermined.

“For the life of me I don’t know why Republicans have such a problem with funding public schools,” she said. “Public education remains the foundation of our democracy.”

The voting talk was not just about getting people to the polls. It, too, was red meat. Following the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision in 2013, striking down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, Republicans passed one of the strictest voter-ID laws in the nation. That law is currently being challenged in court by the NAACP, the Justice Department, and a handful of other plaintiffs, but this primary is the first where a photo-ID requirement is in place. Democrats are concerned the law will dampen turnout among their core supporters, because African Americans are most likely to vote Democratic and most likely not to have qualifying photo ID.

Clinton received an enthusiastic welcome at Hillside—despite the heat, and despite taking the stage more than hour later than expected. Even with the fans off, she was repeatedly drowned out by the din of applause. Whether that translates to the “100 percent turnout in Durham County” that Butterfield demanded remains to be seen. When I chatted with a gaggle of students in the hallway to ask why they were at the rally, the response was mostly nervous faces. “I want to see what she talks about,” one said finally.

Kendrick Lamar vs. Capitalism

Ever since Kendrick Lamar’s untitled unmastered arrived online a week ago, I’ve been walking around muttering “levitate, levitate, levitate, levitate”—one of the mantras Lamar repeats during the first couple minutes of “untitled 07 | 2014-2016” as a slow-rolling rhythm commands all who listen to bob their heads.

It’s possible to imagine a version of that song as a hit, booming from car windows in summertime as America learns to say “no, no-no-no” in the exact cadence Lamar does. But in the form it’s in now, a hit it shall likely not become. Two minutes and 30 seconds in, the groove disappears, a child sings a jingle about Compton, and the tempo resets for a whole different Lamar rap. Later, the song mutates yet again into what sounds like a live acoustic demo, featuring Lamar ad-libbing imaginary back-up singers and crowd sounds. The whole thing is kind of like “Bohemian Rhapsody,” if Freddie Mercury had just recorded himself saying “guitar solo goes here” where Brian May’s shredding currently is.

The (un)titles for this new album and its songs, the fact that its release apparently only happened because of a LeBron James tweet, and the fact that the music originated in the sessions for his 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly suggest that untitled unmastered should be approached as a bonus release. The arrangements are skeletal; the song structures are disorienting; the rapping is excellent. But after listening a bit, the album’s form and content together come to feel like Lamar’s starkest statement yet about the struggle for purity in the face of capitalist pressures to compromise. If it’s not always easily digested, that’s part of the message. Don’t be too surprised if all his songs are untitled from here out.

Lamar often raps as a form of dialectic, and on the opening track, he’s in the difficult position of arguing with God. After the singer Bilal demonically recites some dirty talk toward a “little lamb,” Lamar launches into a furious narrative about the Book of Revelations coming to pass while a gut-rumbling bass line and dread-making strings play behind him. When it comes time for Lamar to be judged by his creator, he points to his discography: “I made To Pimp a Butterfly for you told me to use my vocals to save mankind for you ... I tithed for you, I pushed the club to the side for you.” Pushed the club to the side for you: Avoiding pandering to the masses, according to this version of Lamar’s persona, is godliness.

And pander he didn’t. The most successful track off of the masterful To Pimp a Butterfly went no higher than 39 on the Hot 100. This seemed intentional; the album was a dense, noisy collage of experimental jazz over which Lamar rhymed—and gasped, and screamed—about shame, self-reliance, and social problems. Did it offer enough righteous, unvarnished truth to guarantee him a spot in heaven? At the end of untitled’s opening apocalyptic narrative, Lamar gets stuck on the way to salvation: “Life completely went in reverse/ I guess I’m running in place trying to make it to church.”

Maybe the stalemate comes from the fact that the club came to him even though he says he didn’t want it to. Lamar has moved millions of albums and is more or less a household name by now, and while “Alright” or “King Kunta” aren’t universal nightlife staples, they’ve achieved conscious-party-anthem status. This success sometimes allows him to swagger like any other rapper (well, better than most any other rapper), as when he methodically builds momentum through a litany of boasts custom-tailored to each of his label-mates on “untitled 02 | 06.23.2014.”

But other times, he’s anxious about having prospered. “Get that new money, and it’s breaking me down honey,” goes the chorus on “untitled 08 | 09.06.2014,” whose twitchy funk arrangement was first heard on Jimmy Fallon. For “untitled 03 | 05.28.2013,” he talks of receiving advice from members of different races; the white perspective comes from record-label man trying to leech off Lamar’s talents and encouraging him to sell out: “What if I compromise? He said it don’t even matter / you make a million or more, you living better than average.” It’s not the first time this theme has appeared; exploitation by the music industry was the subject of “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe” off 2012’s good kid, m.A.A.d. city. Years later, he’s still concerned about it.

You can understand why. Diluting his message for a hit, or even just making it so the surrounding music could be more easily commodified, wouldn’t just be uncool, according to his worldview—it would be a sin. He’s already morally tainted, his music sometimes suggests, because the same system he profits from has helped keep places like his home town of Compton down. On “untitled 05 | 09.21.2014,” he lambasts “genocism and capitalism” as he puts himself in the mindset of someone considering murder:

See I’m livin’ with anxiety, duckin’ the sobriety

Fuckin’ up the system I ain’t fuckin’ with society

Justice ain’t free, therefore justice ain’t me

So I justify his name on obituary

Lamar lives a sober life, so whomever he’s rapping about isn’t him in the moment. Society has, as far as it goes, treated him okay lately; at the same Grammys ceremony he debuted this song at, he went home with a fistful of awards. This is, of course, one of the ongoing paradoxes around political art in America. It’s very hard to spread a critique of capitalism without using capitalism; it’s very easy for revolutionary messages to be co-opted by the very institutions and forces an artist might set out to change. When Lamar talks about the devil—code-named “Lucy” on To Pimp a Butterfly—he’s talking in part about the allure of joining the rich-to-get-richer class. On untitled’s second track, he gets a raise, spends it all on himself, looks at the ailing streets of Compton, and wonders “where did we go wrong?” Later, he copies a signature Drake flow and threatens, “What if I empty my bank out and stunt? / What if I certified all of these ones?”

That last line might be a reference to new Recording Industry Association of America rules around album-sales certifications—rules that Lamar’s label boss has said amount to a “cheat code” that his artists would not honor, even though they would technically make To Pimp a Butterfly a platinum record. Lamar is grimly obsessed with the concept of easy gratification, and says it tempts him as much as it tempts many people in poor, black neighborhoods where 9-to-5 jobs are hard to come by and rarely pay well. The final track has him talking to a woman who has earned a scholarship but is still running a credit-card scam, and Lamar doesn’t judge her; as a “rapper chasing stardom,” he’s also a taker of risky shortcuts. At the end of the album, a low voice—maybe God?—cuts in: “When a blessing takes too long, that’s when you go wrong / You selfish motherfucker.”

If the world is full of temptations to enable injustice, he will at least try and make music that resists those forces.

But Lamar does have a tentative solution to the dilemmas he as an artist and his community more broadly face. “Head is the answer,” goes a refrain on a few tracks, which might be an oral sex joke but is also probably a call for conscientiousness. At one point, he references Kanye West and Jay Z’s song “Murder to Excellence,” which powerfully explains hip-hop’s money obsession as a natural response to poverty, violence, and oppression. Lamar has always stood apart from the flashy materialism of many other rappers, but instead of condemning big spending he wants to put it to good use: “It’s evident that I inspired a thousand emcees to do better / I blew cheddar on youth centers, buildings and Bimmers and blue leather.” And on “untitled 05 | 09.21.2014,” he has his colleague Punch sermonize for the power of uncompromising art. “I could speak the truth and I know the world would unravel,” Punch raps, before airing a very Lamar-ian second thought: “Wait—that’s a bit ambitious, maybe I’m trippin’.”

This is part of the genius of Lamar: recognizing the forces that keep people from living up to their ideals, while also embodying a certain kind of idealism. If the world is too full of temptations that, once indulged, end up enabling larger injustices, he will at least try and make music that resists those forces—sonically, lyrically, presentation-wise. untitled unmastered is expected to debut at No. 1 in the country, which would means his faith has been, yet again, rewarded.

10 Cloverfield Lane Is a Wicked, Witty Thriller

A woman packs her bags hurriedly, anxiously. She’s made a decision to leave, though whom or what isn’t exactly clear until she ditches her keys and engagement ring on the way out the door of her New Orleans apartment. As she drives her car into the Louisiana night, her phone rings, flashing the name “Ben.” “Michelle, please come back,” he implores. “Running away isn’t going to help anything.” She hangs up. As the car radio warns statically of a “power surge,” Ben calls again. Tearful, distracted, Michelle loses control of the vehicle, smashing through a guardrail and into blackness.

When Michelle awakens, she’s on a thin mattress on the floor of a cinder-block room. Her injured leg is in a brace that is chained to the wall; her belongings are just out of reach. A steel door clangs open heavily, and a man comes in bearing a tray of scrambled eggs. “What are you going to do to me?” she asks. His ominous response: “I’m going to keep you alive.”

The man explains that they are in an survivalist bunker beneath his farmhouse. There’s been an attack above, “a big one.” Maybe chemical, maybe nuclear. It could be the Ruskies, or it could be Martians. Regardless, “Everyone outside of here is dead.” He estimates that they’ll have to remain in the bunker for a year, or possibly two. Almost as an afterthought, he adds: “My name is Howard, by the way.”

Thus opens 10 Cloverfield Lane, a wicked, witty thriller by the first-time director Dan Trachtenberg. Is Howard a psychopath holding Michelle captive toward his own degenerate ends? Or has he truly saved her from a global Armageddon? Or maybe … both? The film dances nimbly between explanations, maintaining its balance even as it delights in knocking viewers off theirs.

Mary Elizabeth Winstead (The Thing, Smashed) is excellent as Michelle, self-sufficient without being superhuman, her eyes alert to any opportunity to escape. And as Howard, John Goodman gives one of his best performances in years, offering up a helping of the quasi-genial menace he deployed to such great effect in Barton Fink. Rounding out the tiny principal cast is John Gallagher Jr. (who was great in Short Term 12), as Emmett, a handyman who helped construct Howard’s bunker and now shares it with him and Michelle. (Bradley Cooper has a sub-cameo as the phone voice of Ben.)

10 Cloverfield Lane alternates moods seamlessly, ratcheting tension to the breaking point and then deflating it with black humor. One moment, the film raises uneasy questions about who exactly is the “Megan” to whom Howard keeps referring, and what became of her. The next, it segues into its cheery soundtrack of oldies, courtesy of the jukebox Howard has installed in the bunker: “Hey Venus,” “Tell Him,” and, most cunningly, a day-to-day montage of life underground set to “I Think We’re Alone Now.” This is a film savvy enough to recognize that there is nothing more intrinsically nerve-fraying—not abduction, not apocalypse—than a car alarm. And while it is not openly satirical in the vein of the terrific Cabin in the Woods, it shares that movie’s sharp, knowing sensibility. (Little wonder that the Cabin director Drew Goddard is one of the producers.)

The original script for the film, by Josh Campbell and Matt Stuecken, was titled The Cellar. When J.J. Abrams’s Bad Robot Productions began developing the picture in 2012, it brought in Damien Chazelle (Whiplash) for rewrites, and in the process noticed tonal similarities to the 2008 monster movie Cloverfield, which Abrams had produced. The new film’s name was altered accordingly, with Abrams explaining that while it is not a sequel to Cloverfield—nor even taking place in the same fictional universe—it is a “blood relative” and “spiritual successor.” It’s also a considerably better movie, and I say that as someone who enjoyed Cloverfield.

So, has the Earth been invaded? Is it all a monstrous hoax? I surely won’t tell. (Though be advised: Others—including the film’s own promotional materials—have not been so circumspect, and this is a movie best enjoyed with a minimum of foreknowledge.) I will merely recommend 10 Cloverfield Lane as a clever, canny thriller, and endorse an insight that Howard offers in a moment of uncharacteristic self-knowledge: “People are strange creatures.”

The Radical Democracy of the Reaction Video

Ancient leaders gauged their popularity with applause. In Rome, the clapping of a crowd was coded in such a way—variations in volume and in speed and in style—that applause doubled as feedback for the people performing, be they artists or politicians. The crowd’s audible reaction to someone (“audience,” from the Latin for “hear,” derives from the sonic connection between those onstage and off) revealed that person’s standing with extreme efficiency. So applause—an early form of polling, an ancient realization of “big data”—was also a way for citizens to communicate with their leaders, political and otherwise. Reacting to something, loudly and intentionally, was a way for the populace to make their voices heard—such a common way, indeed, as to lead Cicero to remark, “The feelings of the Roman people are best shown in the theater.”

* * *

In early February of 2016, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter released “Formation,” her pop song and anthem and call-to-arms. The song and its accompanying video dropped, though really it is more accurate to say that they descended, on the Saturday before the Super Bowl, as people were weekend-ing and working and otherwise doing their typical Saturday stuff. Suddenly, though, the day and its respective banalities—its jobs and its errands and its birthday parties and its weddings and its Netflix binges—were transformed into an ad hoc high holiday. People around the country and around the world stopped what they had been doing to take in what Beyoncé had put out.

Hierarchy and democracy, commercial culture and free, the death of the author and the ongoing life—there they all are, in 1s and 0s, dancing to Beyoncé.

Beyoncé had, yet again, rippled the culture. And she’d done it in a way that was independent of, but of course also utterly reliant upon, her atomized audience. In response to “Formation,” people began doing pretty much the same thing those feisty Romans had done hundreds of years before: They gathered together, as an audience. They watched “Formation,” performatively. They reacted to it, publicly. They found new ways to applaud.

In the month since “Formation” came into the world, Zachary Campbell, ColorMePynk, Tierian La’Shae, and seemingly hundreds of thousands of others have shared videos of their reactions to the song and its video and the cultural moment it represents. Women, men, boys, girls, friends, couples, groups—some of them critical of the video, most of them awed by it—have taken to YouTube to dance and gawk and exclaim and, all in all, consider the ways that Beyoncé has, once again, slayed. They have done, basically, what any audience will, in the end: They have taken a thing out there in the world and—casually, insistently, joyfully—made it about them.

* * *

The reaction video may well be the quintessential genre of the nascent digital age. Enabled by YouTube and smartphones and iMovie and a cultural and political climate that both enforces social hierarchies and resents them, it carries its own internal aesthetics and motivations. It includes not just “Music Video Reaction Videos,” but also “Movie Trailer Reaction Videos” and “Sports Moment Reaction Videos” and “TV Scene Reaction Videos” and also—the deeper cuts, category-wise—“Scary Prank Reaction Videos” and “Kissing Prank Reaction Videos” and “Marriage Proposal Reaction Videos” and “Post-Anesthesia Videos” and (ready your Kleenex) “Cochlear Implant Activation Reaction Videos.”

The reaction video is improv, played out at the scale of the Internet.

The reaction video is related to “David After Dentist” and unboxing videos and those uber-popular streams that allow their viewers to watch other people play video games, but it is, in the end, distinct: The reaction video takes the Internet’s implicit recursiveness—its genetically determined tendency to feast upon itself—and renders it as culture. It takes the unpredictability of human emotion and turns it into literature. It is improv, played out at the scale of the Internet.

So: Here are some kids trying out old technologies. Here are some older people trying out new ones. Here are some sheltered people sampling “foreign” foods. Here are people taking things in. Here are people sending things out. Here is the Internet, introverted and extroverted at once. The reaction video, a user-generated and radically democratized outgrowth of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and I Love the ’90s and the mockumentary style of The Office, does the same thing those ancient Romans did, centuries ago: It protests against the invisible audience. It insists that the people will have their say. “I know most of y’all just probably want to see the video and don’t want to see me talking away,” Tierian La’Shae remarks before sharing her “Formation” reaction with more than 120,000 viewers. “But. I will give my two cents.”

* * *

The “Formation” reactions, as varied as they are, tend to share a formal similarity: a distinctly, insistently DIY quality that includes abrupt editing, volumes that soar and drop without warning or apology, and performances that refuse to acknowledge themselves as performances. Often, the speakers wear earbuds, bringing an eerily literal interpretation to “dancing to the beat of your own drum.” Sometimes the camera is shaky, evidence of an invisible videographer. Sometimes it is still.

ColorMyPynk’s “Formation” reaction is shot while she’s putting her makeup on to get ready for a Mardi Gras party. Guarnata Bourjolly’s reaction features her sitting on a chair, reading from notes she’s jotted on a legal pad; it is interrupted, mid-way through, by a camera malfunction. (“We just need to do some minor touches with this,” she tells her audience, adjusting the camera while it is still running.) ChrisMcCullyTv’s video begins with him declaring, “I literally just woke up … so we’re gonna get my natural reaction right now. I’m watching it.” (He goes on to remark, in the course of watching the video, “I’m scared!” and then, later, “My armpits are itching!”)

Uneak Tershai’s video features a clacking noise in the background—a noise that is unexplained until another person pops into the frame to announce, “Y’all, I’m typing a paper.” The friend watches the video for a moment, nods, says, “Yeah, I like that part,” and then returns to her paper, never to be seen again.

If Beyoncé’s song is a call to arms, then the thousands of videos reacting to it are her troops, coming forward and revealing themselves.

Some of the “Formation” reactions reinforce the hierarchical dynamics of celebrity. (ColorMePynk to a phantom Queen Bey: “You have slayed once again! You slay!” She will add, a bit later: “I need to go in the corner and pray … and think about my life and my existence.”) Many more of them, however, emphasize the flattening capabilities of digital media. Keyon Elkins’s “YOU’RE GAY” video—this one has nothing to do with Beyoncé; it is a reaction, instead, to people in his own life—constantly interrupts its speech with fourth-wall-breaking asides (“Oh my God, I look horrible”; “Sorry if it’s kind of echo-y in here, because I’m in my bathroom”).

Look at the tones of humility and empowerment twisting and twining in the “Formation” reactions. Look at how, on the one hand, the reactors genuflect—“I need to go in the corner and pray”—at the altar of Queen Bey. Look at how, on the other, their speeches are premised on the fact that they have appointed themselves as her critics. And look at how, as a result of that appointment, their reactions have gotten hundreds of thousands of views (from people, of course, reacting to the reactions). Uneak Tershai’s video, the one interrupted midway by an otherwise invisible paper-writer, has itself gotten more than 1 million views so far.

In that sense, reaction videos emphasize the mercurial divisions separating, at this moment in culture, action from reaction, creator from audience, thing from assessment-of-thing. They insist, in their casual entitlement—“I will give my two cents”—that “remix culture” is also, simply, “culture.” They are fit for a time that finds technology enabling cultural participation as never before; they are also fit for a public that carries out its conversations not just through books and magazines and TV shows, but also through memes and Facebook updates and Tumblr posts and live-tweeted TV shows and live-GIFed awards shows, through thinkpieces and hot takes and the recognition that, as A.O. Scott recently argued, “criticism is an art form unto itself.” Idiosyncrasy and universality, hierarchy and democracy, commercial culture and free, the death of the author and the ongoing life—there they all are, in 1s and 0s, rendering and streaming and dancing to Beyoncé.

As ColorMePynk tells a phantom Queen Bey: “I need to go in the corner and pray … and think about my life and my existence.”

And—it’s long been the case, but the “Formation” reactions make it especially clear—reaction videos emphasize the blurred lines between that which we think of as “politics” and that which we think of as “culture.” “Formation” is both a pop song and a multimedia speech about race and violence and Black Lives Matter. The videos reacting to it—which derive much of their drama from their tone of invited intrusion—acknowledge, overtly and less so, its political dimensions. If Beyoncé’s song is a call to arms, then the thousands of videos reacting to it are her troops, coming forward and revealing themselves.

* * *

The reaction video as a genre was born, by most accounts, in early 2006, when the YouTuber raw64life uploaded a video—recorded in 1998—of a kid and his sister on Christmas Day. The kids unwrapped, this being ’98, a Nintendo 64. And they proceeded to freak out, adorably. Their video—“Nintendo Sixty-FOOOOOOOOOOUR,” it’s called—went viral. Today, it has more than 20 million views and more than 48,000 comments.

Any time a major cultural product—a Rihanna song, a Kanye album—comes out, videos reacting to it are de-facto extensions of that product.

A seeming formula for virality having been found, similar videos followed. And then … came “2 Girls 1 Cup.” The shock video—a trailer for the pornographic scat-fetish film Hungry Bitches, which is really all that needs to be said about that—became instantly (in)famous. And, almost immediately, reaction videos stepped in to fill the vacuum left by the flight of human decency: Instead of watching the shock video, people could watch other people watching it. “2 Girls 1 Cup,” the critic Sam Anderson noted, “generated a whole menu of human response: You could watch a grandmother watching it or a room full of Marines or a group of nursing students or the porn star Ron Jeremy or the ultimate fighting champion Rampage Jackson or—on the show Tosh.0—an entire studio audience. Soon it matured into a full-blown Internet meme, which means you could also watch the reactions of Super Mario, Darth Vader, Kermit the Frog, Stewie from Family Guy, and multiple cats.”

The reaction video was thus, via a combination of people wanting to be shocked and fearing it, newly recognizable as a genre. In late 2008, “reaction video” made its way onto Urban Dictionary (according to one Señor Giggles, a reaction video is “a recording of a reaction to a disturbing or frightening image or video”). In 2011, the genre got a spirited write-up in The New York Times (under the revealing headline “Reaction Videos as Anthropological Study of America”). Soon people were rushing to post reactions to Game of Thrones’s Red Wedding. And to the new Star Wars trailer. And to basically anything that was getting traction online. (Witness the bit of cultural anthropology that is “Funniest Reaction to ‘Scarlet Takes a Tumble’ Video.”) The reaction video became sort of ubiquitous. To the extent that any time a major cultural product—a Rihanna song, a Kanye album—comes out, videos reacting to it are de-facto extensions of that product.

There’s good reason for that. The reaction video may be about people watching people watching people; it is also, however, about the pleasures of watching as a group. As an audience. As a fandom. As a public. Reaction videos are popular for the same basic reason that 20 million people tuned in to watch the live simulcast of Kanye’s Yeezy Season 3: We’re social animals. We know that, in a profound way as well as the glib one, sharing is caring. Reaction videos allow us to take a thing and make it our thing.

As Kate Miltner, a scholar of Internet culture at the University of Southern California, told me in an email,

I know that when I share a video I love with someone I watch their faces (if we are in the same place or on video chat) more than I watch the video itself because I want them to love what I have sent them just as much as I do, and I *really* want them to specifically love those key moments—because if they do, then it’s a thing we can continually reference. It moves from media text to shared experience to personal reference/joke. Sharing media is about creating connection, and when we see total strangers react just like we did to a media text we love, there’s something really gratifying about that—it makes us feel part of something bigger while at the same time validating our own personal tastes and experiences. Toss a funny reaction or a cute kid in there and you’ve got YouTube gold.

Which is not to say that reaction videos are purely earnest, or purely DIY, or purely artistic in their impulse. Some of their success, YouTube-views-wise, must be attributed to people searching for the original video and mistakenly arriving at a reaction. (As one commenter noted in response to one of the “Formation” reactions: “hate when you’re thinking you GONNA watch the video and these things want to DAMN have a talk show.”)

And the videos can also, being produced both by and for the Internet, be ironically self-referential. The Fine Brothers—the creators of the immensely popular Teens React series on YouTube—also produce a show called, more generally, YouTubers React. One of its episodes, posted last year, is titled “YouTubers React to Every YouTube Video Ever.” And one of the show’s reactors, Tyler Oakley, recently uploaded his own video. Its title? “Tyler Oakley Reacts to Teens React to Tyler Oakley.”

The reaction video may be about people watching people watching people, but it is also about a simpler pleasure: people watching, together.

The legal scholar Tim Wu calls it “The Cycle”: the inevitable organic-to-institutionalized trajectory that most any media property will take as it moves from “disruptive” to “ubiquitous.” And, indeed, the reaction video, in short order, was co-opted by brands both corporate and personal. Buzzfeed adopted the premise of the reaction video for its “People Try X for the First Time” conceit. The creator of “HOW COULD YOU DO THIS KRISTEN?!” followed that video up with many more—significantly less trafficked—rants: repeated attempts, it seems, to make lightning strike again. Celebrities began to use the videos as personal brand extensions. (Thus, YouTube video titles like “Celebs React to the Red Wedding.” And headlines like “Arya Stark Posts Reaction Vine to Game of Thrones Red Wedding.”)

Celebrities also, of course, joined the chorus reacting, publicly, to “Formation.” John Legend. Uzo Aduba. Mindy Kaling. Sophia Bush. Raven-Symoné. Rudy Giuliani. Pop Sugar offered “9 Celebrity Reactions That Perfectly Describe How You Felt When Beyoncé Dropped ‘Formation.’” Southwest Airlines got in on the (re)action. So did, because of course, Red Lobster.

The reaction video cares very little about “box office” or Nielsen numbers; it cares instead about art’s ability to bring people together.

There’s a kind of inevitability to all this. As Clay Shirky, the author of Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations and Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age, told me in an email, “What YouTube showed us is that people your age and especially mine have no idea what makes for compelling viewing, because prior to now, no one has ever tried any sort of experimentation.” The reaction video is one way of engaging in this experimentation—a genre, essentially, that has arisen from the primordial YouTube and proved its Darwinian mettle. And its environmental fitness is unsurprising. “If people like domino vids, and they like Fail vids,” Shirky says, “then ‘The Ultimate Fail Compilation (Domino Edition)’ seems like something of an obvious move, no? And if domino fail compilation videos are obvious, then how much more obvious is collating the pleasure of watching someone else have surprising experiences?”

* * *

“Reaction,” as a term, suggests a kind of scientific automation: the action, the equal and opposite reaction. And while, as Shirky suggested, there is a kind of anthropological obviousness to the reaction video, what is perhaps most striking about the genre is how deeply unpredictable its individual videos have proven to be. Did you expect that watching a pop video would lead one woman to prayer? Probably not.

In that sense, the reaction video is a commercial phenomenon as well as a cultural one. It used to be that audiences—who are also, so often, consumers—“reacted” to something with the stark bilateralism of the commercial transaction: by buying the ticket or not, by buying the book or not. They belonged to a system in which audiences doubled as a collection of disembodied dollars: Creators created; consumers either yayed or nayed in response; the creators learned from the yay-nay dynamic; the circle moved on. It’s a cycle that is changing, slowly, but that has deeply infiltrated our mode of thinking when it comes to judging the value of artistic production: Even today, critics (and, in particular, “reviewers”) tend to make the mistake of conflating commercial success—“box office,” as a hazy yet very specific metric—and artistic.

The reaction video is, on top of so much else, a rebuke of the decision-via-dollar dynamic. It cares very little about “box office” or Nielsen numbers or what have you; it cares instead about art’s ability to bring people together in ad-hoc communities and fandoms. The videos may not be the stuff of high criticism—there is very little, in general, to be found of historical context or literary comparison or anything else that might otherwise be encountered in the New York Review of Books—but they do something that is just as valuable in the age of the quantified audience: They take an artistic product on its own terms. They reinforce the notion of art for art’s sake.

And: They do the same thing those ancient Romans did, when they cheered and booed and clapped for their leaders: They insist that “the audience,” in a culture of Yelp ratings and Uber stars and YouTube views, is not just a mess and a mass of demographics, but also a collection of humans. They transfer that audience from passive consumers of culture into active creators of it. And they celebrate the ability good art—high or pop or in-between—has of inspiring you and collecting you and making you say, as ColorMePynk did when she saw “Formation” for the first time: “I need to go in the corner and pray.”

March 10, 2016

Twisting the Media's Arm

Donald Trump’s campaign is taking on one of its enthusiastically supportive outlets in conservative media.

The Republican presidential front-runner’s campaign denied allegations that Corey Lewandowski, the campaign manager, assaulted Michelle Fields, a reporter for Breitbart News, after a Tuesday news conference in Florida. Trump campaign spokeswoman Hope Hicks then insinuated Fields fabricated the incident for attention, and that she had a pattern of making up allegations.

NEW: Trump campaign spokesperson Hope Hicks responds to allegations campaign manager assaulted Breitbart reporter: pic.twitter.com/LHRMKXzy3K

— ABC News Politics (@ABCPolitics) March 10, 2016

The altercation reportedly occurred during a press scrum after Trump’s evening news conference on Tuesday as Fields tried to ask the candidate a question about affirmative action. The Republican front-runner had just won the Michigan and Mississippi primaries.

“Trump acknowledged the question, but before he could answer I was jolted backwards,” Fields wrote Thursday. “Someone had grabbed me tightly by the arm and yanked me down. I almost fell to the ground, but was able to maintain my balance. Nonetheless, I was shaken.”

Another reporter present identified the man responsible as Lewandowski.

According to the Daily Beast, Lewandowski originally told another Breitbart reporter that he mistook Fields for “an adversarial member of the mainstream media” instead of a Breitbart reporter. After the Trump campaign denied the event took place on Thursday afternoon, Breitbart’s upper echelons, which received some criticism for not initially supporting Fields strongly enough, fired back with another statement.

“The Washington Post just published a very detailed, first-hand account from their senior reporter Ben Terris who is familiar with the campaign, the personalities involved, and was an eyewitness to the incident,” Breitbart News CEO Larry Solov said in the statement. “We are disappointed in the campaign’s response, in particular their effort to demean Michelle's previous reporting. Michelle Fields is an intrepid reporter who has covered tough and dangerous stories. We stand behind her reporting, her techniques, and call again on Corey Lewandowski to apologize.”

In the article referenced by Solov, Terris wrote clearly about what he witnessed:

As security parted the masses to give him passage out of the chandelier-lit ballroom, Michelle Fields, a young reporter for Trump-friendly Breitbart News, pressed forward to ask the GOP front-runner a question. I watched as a man with short-cropped hair and a suit grabbed her arm and yanked her out of the way. He was Corey Lewandowski, Trump’s 41-year-old campaign manager.

Fields stumbled. Finger-shaped bruises formed on her arm.

“I’m just a little spooked,” she said, a tear streaming down her face. “No one has grabbed me like that before.”

She took my arm and squeezed it hard. “I don’t even want to do it as hard as he did,” she said, “because it would hurt.”

Fields also responded to the Trump campaign’s denial on her personal Twitter account.

I guess these just magically appeared on me @CLewandowski_ @realDonaldTrump. So weird. pic.twitter.com/oD8c4D7tw3

— Michelle Fields (@MichelleFields) March 10, 2016

Will Trump reprimand or fire Lewandowski and rein in his staffers? It’s doubtful. As my colleague David Graham noted earlier, Trump himself often encourages those who attend his rallies to vent their anger at protesters and reporters. He frequently launches into verbal tirades against journalists in the same room as him, sometimes by name. And he once promised to pay the legal fees of supporters who “knock the hell out” of hecklers.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower