Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 208

March 20, 2016

The Walking Dead: It Comes Back Around

Every week for the sixth season of AMC’s post-apocalyptic drama The Walking Dead, Lenika Cruz and David Sims will discuss the latest threat—human, zombie, or otherwise—to the show’s increasingly hardened band of survivors.

David Sims: There comes a moment in every season when The Walking Dead kills time in preparation for a blockbuster finale. “Twice as Far” was it. It was a meandering hour, focusing on fringe characters and dwelling on plot developments that largely occurred off-screen, during the time jump between episodes nine and 10. It included a fairly unnecessary death and the baffling return of a character from the first half of season six, a one-episode villain who escaped with Daryl’s crossbow the last time we saw him. It grasped for emotional weight, but came off as confusing. It was, in short, a bad episode.

For some reason that final minute, and Carol’s voice-over monologue breaking up with her boyfriend Tobin, chafed the most of all. A lot of this season has focused on Carol’s tentative experiments with domesticity since arriving in Alexandria, and her relationship with Tobin was part of that (along with all her cookie-making). But Carol and Tobin’s romance has played out almost entirely in the background—I still have to think for a second to even remember his name—and whatever crucial decision they made to move forward as a couple, it happened during the months the show skipped, in between the pit of zombies and the war with Negan’s Saviors.

After Carol’s traumatic time fighting Negan’s lieutenants in the last episode, things have seemingly returned to normal in “Twice as Far,” with everyone now home safe in Alexandria and plotting their next move. But Carol is still haunted by the horrific murders they committed, particularly her battle with Paula, and can’t shake whatever survivor’s guilt she’s brought home with her, telling Tobin she has to leave him because she can’t kill for him, whatever that means. This all feels like bait for the audience more than anything, a sign that Carol could be marked for death in the upcoming season finale, but while last week’s episode was wrenching viewing, this week felt like an afterthought.

That’s especially strange considering an Alexandrian was killed off this week—the friendly town doctor Denise (Merritt Wever), who died in sudden, shocking fashion at the hands of the avenging Dwight (who claimed he was aiming to kill Daryl, but shot Denise in the eye instead). Denise is another character who made huge plot strides during the time jump, getting into a serious relationship with Tara that seemed very sweet but came largely out of nowhere. Wever is an Emmy winner and a super-talented actress, but the show never had much for her to do except fumble through medical supplies and seem out of place among the show’s constant misery and violence.

There’s nothing shocking about The Walking Dead offing a recurring character at this point, but the writers still seem to think there is.

That’s mostly what she did this week, going on a supply run with Rosita and Daryl and trying to become more comfortable with zombie-murdering. That prompted a reckless encounter with a walker that saw her nearly getting bitten, but that whole suspenseful episode was another bit of audience misdirection, setup for her shocking death. I’m sad to see Denise go, but I’m even more frustrated with how cutesy her departure was—there’s nothing shocking about The Walking Dead offing a recurring character at this point, but the writers still seem to think there is. Denise was killed by Dwight, the burn-scarred bandit that Daryl encountered back in season six, episode six—he had a diabetic wife and survived only because Daryl took pity on him.

I had basically forgotten Dwight existed, so his return didn’t feel too shocking—mostly just confusing. Perhaps there’s a lesson to be learned here about Daryl’s survival instinct, but this episode felt too random to be united by one common theme. Yes, Denise was trying to hone her survival skills, but that wasn’t what got her killed; in a pointless B-plot, Eugene got in a fight with Abraham over his own developing prowess, claiming he no longer needed Abraham’s help to dodge zombies. Then he was promptly captured by Dwight. Great job, Eugene.

In general, I was left confused and frustrated by “Twice as Far,” an episode that worked within the margins of the show and came off feeling pretty marginal. Lenika, am I being too harsh? Was there some grander theme to pick out here that related back to the show’s recent, strong run?

Lenika Cruz: I’m relieved you feel this way, David, because—even after three pretty terrific episodes—I found myself straining to care about anything that happened this hour. I really tried! When Rosita hooked up with Spencer. When Morgan talked to Rick for eight seconds about building a jail cell to give the group “options.” When Denise found the “Dennis” trinket and talked about her long-lost twin brother. When Abraham and Eugene had their falling out. When Denise’s inspirational, heavy-handed speech to Rosita and Daryl sputtered out thanks to the arrow that materialized in her eye socket. (That scene achieved comic levels of violence, as did Eugene’s inspired penis-biting attack. Blergh.)

The bookend scenes of vaguely idyllic life at Alexandria gestured at a degree of meaningfulness that was brutally absent this episode. “Twice as Far” seemed to try to reexplore the old contrast between the hardened survivors (Abraham, Daryl, Rosita) and the “weaker” but more intellectual ones (Eugene, Denise). Unfortunately, since Denise was neither a faceless secondary character, nor a beloved mainstay, her death had a weaker emotional impact than it could have, had the show waited a bit longer.

Still, her loss will have serious implications for the group, which now no longer has a doctor to tend to the many fatal injuries that are certain to arise in the future. After all, Rick and the gang have a rotten track record when it comes to steering clear of the most deranged post-apocalyptic survivors. Perhaps this could foreshadow the Alexandrians’ need to continue their relationship with the Hilltop colony, which at least has an obstetrician.

Just to avoid being a total bummer: The highlight for me was easily the zombie with the metal-melted head.

While the last few episodes advanced the characters and their situation in significant and novel ways, “Twice as Far” felt like a regression to the show’s old hangups. Far from just being lackluster, this episode was often plain confusing, as you pointed out, David. The return of the man who stole Daryl’s crossbow yielded more of a “huh?” than an “ah!” Even the more interesting moments were delivered in plodding fashion: The meh Eugene/Abraham storyline, for example, introduced the possibility of the Alexandrians venturing into ammo-manufacturing, since their supply is running low. This kind of world-building almost always enhances the show, but the ensuing dispute between Abraham and Eugene felt incredibly contrived and weighed down their scenes unnecessarily . Just to avoid being a total bummer: The highlight for me was easily the zombie with the metal-melted head. Say what you will about the show, but it’s virtually never at a loss for cool walkers (sewer zombie, fire zombie).

If “Twice as Far” is the one real dud of this half-season so far (along with the mid-season premiere), I can be okay with that. I just hope that the missteps of this episode don’t spill in to the next two weeks—the penultimate episode and then the season finale. It’s simply too late to begin stumbling, and a showdown with Negan and the Saviors looks inevitable at this point; Rick and the crew have far too much Savior blood on their hands to get away from this without losing more of their own.

The looming question is, of course, who will likely be killed off in the coming weeks. There are convincing cases to be made for Glenn, Carol, and/or Daryl meeting their end in the next couple weeks. Sadly, The Walking Dead isn’t great at concealing who’s imminently marked for death. But beyond the routine bloodbath to be expected, I’m excited to see how the show sets up its stakes for the next season. As the series heads into its seventh season, I’m hoping it chooses to become more ambitious in scope, more fully exploring the world and what it has become, rather than focusing so narrowly on a few people going through the same challenges and internal conflicts again and again. After all, the past few episodes have proven the show is more than capable of it.

Bienvenido a Cuba, Obama

The last time an American president went to Cuba, he took a battleship to get there.

President Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the country in almost 90 years when Air Force One touched down in Havana Sunday afternoon. The visit comes 15 months after a historic announcement by Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro that the two Cold War-era adversaries would normalize relations after half a century, a decision reached after months of secret conversations between diplomats on both sides.

Obama, who is joined by first lady Michelle and daughters Sasha and Malia, has a full schedule for the three-day trip. The first family will take a walking tour of Old Havana Sunday. The president will meet with Castro and attend a state dinner Monday, and give a speech directed at the Cuban people from the Alicia Alonso Grand Theater Tuesday.

Former U.S. President Calvin Coolidge delivered remarks at the same theater in 1928, after arriving in Cuba on the USS Texas. Back then, the U.S. controlled Cuba’s politics and economy. In 1959, Fidel Castro and his communist rebels took power, and two years later Dwight Eisenhower closed the American embassy in Havana and cut diplomatic ties between the two nations.

The embassy reopened last August, the first of a series of steps the Obama administration has taken to reopen Cuba to the U.S. Some of the biggest policy changes were announced in the weeks before his visit to Havana. The administration said it would resume commercial air travel between American and Cuban cities; lifted a ban on Cuban access to the international banking system, which would allow U.S. banks to process Cuban transactions in the U.S. financial system; restored direct mail service between the two countries; and eased restrictions on U.S. travel to Cuba. While tourism is still technically prohibited, the administration now allows “people-to-people educational travel,” which, as the Associated Press put it, “is so broad it can include virtually any activity that isn't lying on a beach drinking mojitos.”

Obama will meet with Cuban entrepreneurs Monday, and attend a baseball game between the Tampa Bay Rays and the Cuban National Team Tuesday. The administration has also allowed Cuban citizens to begin earning salaries in the U.S. without first starting the immigration process, a change that would allow Cuban athletes to play Major League Baseball and other professional sports in the U.S.

Obama’s visit is being billed as a gesture of good will and an attempt to further cement the two countries’ new relationship before the Oval Office receives its next occupant. But distrust and disagreements persist between the ideologically different governments. Obama will meet with Cuban political dissidents Tuesday, and is expected to raise concerns to Castro about his government’s human-rights record, which Human Rights Watch says “continues to repress dissent and discourage public criticism.” Obama will not meet with Fidel Castro, the 89-year-old brother of Raul whose revolution tore the ties between the U.S. and Cuba. The 1960s-era trade embargo on Cuba remains in place, and requires approval from Congress to lift it.

Still, Obama’s decision to reestablish ties bucked over five decades of bipartisan consensus, as The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg recently explained in his wide-ranging story on the president’s foreign-policy playbook. Obama “can see shades of gray in history,” Ben Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national-security adviser, told Goldberg. “We had used the black-and-white version of history to justify Cuba policy that didn’t make much sense; that was far past its expiration date,” Rhodes said.

Recent surveys of Cuban Americans show the majority support the administration’s efforts to normalize relations between the two countries—even in Florida, where the Cuban American community, particularly an older generation that remembers well the 1960s revolution, has lobbied for decades to keep the embargo intact. Younger Cuban Americans, linked to their home country by familial ties and considerably less history, are more likely to support the policy shift, pointing to the economic opportunities that may come with it.

Surveys of Cuban citizens suggest an overwhelming majority believe a better relationship with the U.S. would benefit Cuba. For many, a visit by a U.S. president was the stuff of science fiction, says Raul Moas, who runs an organization for youth empowerment in Cuba called Roots of Hope. Moas’s parents and grandparents fled Cuba and settled in Miami in the 1960s, and some of his relatives still feel uncomfortable talking about it.

“I think Cubans would find it more believable that a martian landed on the capitol steps in Havana than see the president of the United States getting there,” Moas told me, on his way to Cuba for the visit.

Spinoff City: Why Hollywood Is Built on Unoriginal Ideas

In 2010, industry publications reported that production on Battleship, a new blockbuster starring A-list actors including Liam Neeson and Alexander Skarsgård, had begun. The punch line, of course, was that the film was “loosely based” on the popular Hasbro board game of the same name. With this news, the blogosphere exploded with incredulity over commercial cinema’s seeming inability to come up with original ideas for motion pictures. Cinema Blend’s Eric Eisenberg lamented, “More than just being about the quality of Battleship, a big part of the reason people were turned off of the movie was because the idea of a film based on a board game is ridiculous. I understand that Hasbro loved all of the money they made from the Transformers movies, but seriously, we don’t need a Hungry, Hungry Hippos adaptation.”

Although Battleship went on to receive fairly positive reviews (many critics expressed surprise over how “not bad” the film was), the film did poorly at the box office, making only $300 million back on its $200 million investment. Nevertheless, shortly after its release, it was announced that several other board games would receive the big screen treatment, including Monopoly, Action Man, and yes, even Hungry Hungry Hippos. It isn’t strictly accurate to call these films “adaptations” of board games—Hungry Hungry Hippos and Battleship are brands, names, and images, but they’re not narratives or characters. And this seems to be precisely Eisenberg’s point: The problem with contemporary commercial cinema (epitomized by Hollywood) is that it’s more concerned with making money than it is with telling quality stories or creating indelible characters.

As demonstrated by the strong negative reaction to Battleship, commercial cinema’s attachment to the processes of repetition, replication, sequelization, and rebooting—to films that appear in multiplicities—is generally understood in a negative light in the popular press. With the announcement of every new sequel or reboot appears a response decrying the loss of creative innovation and the steady decay of the cinema. In a 2012 story in Vulture, Claude Brodesser-Akner describes the critical reaction to Universal’s multimillion-dollar deal with Hasbro toys this way: “The reaction from many in the creative community was scorn, followed by resignation: Had it come to this? A latex rubber doll filled with gelled corn syrup was now what passed for intellectual property?” There’s a generalized sense that commercial cinema is losing its ability to come up with new ideas and, in its drive for profits, is finally scraping the bottom of the story-property barrel.

But most of these reactions confuse the need to make action-heavy, dialogue-light tentpole films that do well internationally with the drive to make films out of known story properties, something now called “preawareness.” These are two different production strategies that just happen to work well together. Hollywood’s dysfunctional love affair with blockbusters—movies that can potentially make or break a studio—is a relatively modern phenomenon.

“Had it come to this? A latex rubber doll filled with gelled corn syrup was now what passed for intellectual property?”

Throughout the 1960s, the major U.S. studios lost money at the box office for several interrelated reasons, including the rising popularity and widespread availability of television, “white flight” to the suburbs, and the slow dissolution of the studio system form of production.

To recoup their losses, studios began investing production money in fewer, very expensive “event” pictures. This new mode of production proved problematic when these pictures failed to recover their production costs at the box office. Famous flops like Cleopatra (1963), Star! (1968), and Hello Dolly! (1969) put major studios such as 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., and United Artists on the brink of financial ruin. After a brief flirtation with making films for urban African American audiences, leading to the creation of the blaxploitation cycle of the 1970s, studios discovered that fans would go to see movies like Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) over and over, thus ushering in the era of the modern blockbuster.

Ironically, it was the directors of these first blockbusters, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who recently made headlines when they predicted disaster for the film industry. “There’s going to be an implosion where three or four or maybe even a half-dozen megabudget movies are going to go crashing into the ground, and that’s going to change the paradigm,” Spielberg reportedly said at the opening of a University of Southern California media center. In these formulations, multiplicities (or at least big-budget tentpole films, which are almost always part of a multiplicity) threaten not simply American cinema’s ability to be seen as art, but its very ability to exist. And so, as is often the case, history winds up repeating itself.

Although the U.S. blockbuster didn’t emerge until the 1970s, the practices of basing films on pop-cultural ephemera like popular board games and duplicating familiar story properties and characters have been common in filmmaking since its origins. In 1905, Thomas Edison released The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog, a film based on a popular souvenir postcard image. The movie’s appeal was predicated on its ability to create a moving, breathing version of a popular postcard series featuring a humorously named family. It isn’t a big leap from a successful film based on a souvenir postcard to a successful film based on a board game. The drive to exploit audience interests in comic strips, magic lantern shows, vaudeville, popular songs, and other films and then to replicate those successful formulas over and over until they cease to make money is foundational to the origins and success of filmmaking worldwide.

* * *

It isn’t just the film industry that relies on multiplicities to generate sure profits. Television also relies on the replication and repetition of successful formulas as a central part of its production strategies. Although this process of creative theft is central to capitalism itself, it is, as in the case of cinema, a generally denigrated process, as if the entry of capitalism somehow contradicts the possibility of art. Unoriginal art, in critical parlance, is an oxymoron.

In the 1950s, during the early days of television ownership, most American TV owners were upscale and urban. They were what we now call “first adopters,” and they had the money to invest in a new and untested form of home entertainment. The industry was based in New York, and for a variety of reasons, including sponsors’ ownership of time blocks, live televised theater was one of its dominant forms.

These teleplays featured adaptations of works by the nation’s most notable authors (Tennessee Williams, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald). Television playwrights, especially Rod Serling and Paddy Chayefsky, were national figures. This early programming was modernist in its insistence on the unique, isolated text, and hence was distinct from the forms of multiplicity—especially the situation comedy and the continuing dramatic series—that soon came to dominate. But the world of television changed as new forms of financing evolved and more Americans acquired sets. TV subsequently became understood as a lowbrow, commercial mass medium that could be experienced by anyone.

The scholars Michael Newman and Elana Levine argue that beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, when the concept of “quality television” increased the possibilities of targeting programming to desirable (read: affluent) audiences, television began to once again aspire to become a highbrow medium. Other technological changes, such as the practice of putting entire seasons on DVD, as well as the amount of serious writing that critics began to devote to their favorite shows, created the sense that American television was finally being appreciated as an art form. According to Levine and Newman, “Legitimation always works by selection and exclusion; TV becomes respectable through the elevation of one concept of the medium at the expense of the other.” Indeed, HBO’s famous ad campaign from the 1990s, “It’s not TV. It’s HBO,” is a good example of how television can be legitimated as art only if it’s distanced from the medium of television itself.

As the current demonization of reality-television stars reveals, we are inherently suspicious of the popular. Furthermore, the gatekeepers of the world of media appreciation, who are paid to dispense their good taste—film and television critics, but also media scholars—reify and limit the sphere of what constitutes good taste. So it makes sense that most of the texts that fit under the broad umbrella of multiplicities, such as film sequels and cycles, television remakes and spinoffs, are most frequently discussed as “guilty pleasures” (when they’re not dismissed outright as harbingers of the end times of cultural production).

“It’s not TV. It’s HBO,” is a good example of how television can be legitimated as art only if it’s distanced from the medium of television itself.

Since television is a younger medium than film, the field of television studies is currently grappling with the same conversations that film-studies scholars were having in the 1970s. Only recently has television itself reached the stage where it’s able to “legitimatize” itself and make claims for its status as art. Some critics feel that the current golden age of television (which many date to the premiere of HBO’s The Sopranos in 1999), like the “golden age” of cinema in the 1970s, is in a state of decline due to its insistence on repetition. But as Vox’s Todd VanDerWerff noted in a 2013 essay for A.V. Club, “The dirty little secret here is that essentially every decade except the 1960s has been proclaimed the ‘golden age of TV’ at one time or another.”

In other words, critics and historians of television, much like their counterparts in cinema studies, are constantly searching for that ideal moment when the art form they love was considered to be at its purest, to be reaching its richest potential. But to dismiss movies, or TV shows, because they’re inspired by, or part of, a preexisting franchise or series, is to ignore the entire history of the moving image. Cinema has always been rooted in the idea of multiplicities—that is, in texts that consciously repeat and exploit images, narratives, or characters found in previous texts. Self-cannibalizing cycles and sequels, and even the practice of making films out of toys and board games, are filmmaking strategies dating back to the industry’s first decade, not a symptom of contemporary culture’s inability to create anything new.

This article has been adapted from Amanda Ann Klein and R. Barton Palmer’s book, Cycles, Sequels, Spinoffs, Remakes, and Reboots: Multiplicities in Film & Television.

One Thing Considered: ‘Stressed Out,’ an Anthem of Millennial Anxiety

This is the inaugural “One Thing Considered,” an occasional attempt by Megan Garber and Conor Friedersdorf to talk through cultural artifacts that tickled their brains. In this edition, the artifact at hand is the song “Stressed Out,” the nostalgia-laced hit from the Ohio duo Twenty One Pilots (also known as Josh Dun and Tyler Joseph). It is the band’s first top 10 hit, having reached number two on the Billboard Hot 100.

Conor Friedersdorf: Would you trade the ups-and-downs of adult life for a soothing lullaby in your childhood bedroom? That’s the comforting fantasy that Twenty One Pilots conjure in “Stressed Out.” When I first heard the song, listening to KROQ on the 405 Freeway in Los Angeles, I thought, watch out Taylor Swift, this is the Millennial anthem.

“I was told when I get older all my fears would shrink,” it begins. “But now I’m insecure and I care what people think.” A later lyric notes, “Out of student loans and treehouse homes we all would take the latter.” Student loans loom large: They are the single specific stress the song mentions. This line comes a bit later: “Used to dream of outer space but now they’re laughing at our face / Saying, ‘Wake up, you need to make money.’”And then that wistful chorus: “Wish we could turn back time, to the good ol’ days / When our momma sang us to sleep but now we’re stressed out.”

The character singing all this is named Blurryface. The band’s frontman described him on MTV as a guy who “represents all the things that I as an individual, but also everyone around me, are insecure about.” The result is a catchy, interesting song. Does it say something about this stressed-out moment in our culture?

Megan Garber: First of all: I miss KROQ. Second: Listening to “Stressed Out,” I couldn’t help but think of Skee-Lo’s “I Wish”—not just because of its upbeat pace and sing-songy raps, but also the confessional nature of its lyrics. (Skee-Lo: “I wish I was a little bit taller/ I wish I was a baller/ I wish I had a girl who looked good, I would call her”). Skee-Lo emphasized the connection between physical prowess and economics—the frustrating fact that, for him, being relatively short and unathletic wasn’t just an unfortunate physical condition, but also a disadvantageous social one:

I wish I had a brand-new car

So far, I got this hatchback

And everywhere I go, yo, I gets laughed at

And when I’m in my car I’m laid back

I got an 8-track and a spare tire in the backseat, but that’s flat

And do you really wanna know what’s really whack?

See I can’t even get a date, so, what do you think of that?

Status, via stuff. It’s an almost Darwinian interpretation of consumer attainment: What the narrator can buy—and more to the point, what he’s not able to buy—directly affects his social standing. And also (Darwin!) his ability to get “a girl who looks good.”

“Stressed Out” both updates and rejects “I Wish.” It is entirely about aspiration, yet it’s about, actually, aspiration’s failure: “Wish we could turn back time, to the good ol’ days / When our momma sang us to sleep but now we’re stressed out.” In the song’s video, the pair sit on a curb, drinking that ultimate beverage of disaffected youth: Capri Sun. They ride bikes down a barren suburban street. They engage in complicated high-fives. Beyond that, they don’t do much of anything.

All of which says something sad about the present moment: “Stressed Out” reads as anthemic precisely because it is, upbeat tones notwithstanding, fairly hopeless. These guys aren’t dreaming of the things they could get, were they a little bit taller, more athletic, and fit for their world. They’re beyond striving for any of that. They’re something sadder than unsatisfied: They’re reconciled. All they can do, beset with loans, unsure of how to make the money that will free them from debt, is to mourn the very thing that Skee-Lo embodied: the ability to dream for something more.

But maybe (very, very possibly) I’m reading it too pessimistically? Maybe there’s a reason for hope lurking within “Stressed Out”?

Friedersdorf: That’s just it: I see no hope in “Stressed Out.” It’s so much more bleak than other songs grounded in wistfulness for childhood. Remember “Playdoh” by the Aquabats?

When I was a little man

Playdoh came in a little can

I was Star Wars’ biggest fan

Now I’m stuck without a plan

GI Joe was an action man

Shaggy drove the mystery van

Devo was my favorite band

Take me back to my happy land

There’s ambivalence about growing older and nostalgia for childish things. But Blurryface is longing for something more basic––feeling safe (“when the Mama sang us to sleep”), having aspirations (“we used to build a rocketship and fly it far away...”).

I remember the stress I felt packing up my dorm with no clue what job I would get or how long it would take to find. My student loan payments were about to start and continue for untold years. So it isn’t that I don’t relate to being stressed out by that unnerving moment when I had to “wake up and make money,” or else, for the first time.

But I still loved being 22. At 6, I may have taken comfort in my mom singing me to sleep, but I hated having a bedtime. At 16, I didn’t have to worry about student loans.

I did, however, have a curfew.

I remember being a teenager with a crush and nowhere more private to make out than a parked car. “Wouldn’t it be nice if we were older / Then we wouldn’t have to wait so long,” the Beach Boys sang. “You know its gonna make it that much better / When we can say goodnight and stay together.” At 16, I figured they were right.

At 22, I knew they were.

After graduation, I hung out in L.A. for a couple days with a woman I liked, sleeping on the hard floor of an apartment where a mutual friend had just moved. I wanted no more than to sit around drinking cheap beer and listening to music and talking all night. That was allowed! My friends and I could afford dollar tacos and beach camping. If we split gas we could drive anywhere we wanted. It was glorious.

Some years ago, when my Millennial cousin turned 16, I recall that she and a bunch of her friends were just uninterested in getting a driver's license. I couldn't fathom it. How could a freedom that generations had prized so zealously just lose its appeal? A part of me identifies with the anxieties so powerfully expressed in “Stressed Out.” But when Blurryface moves beyond nostalgia to an outright preference for treehouse homes over any adulthood that includes student loans, I don’t relate.

Garber: I hear that!

Given how obsessed the culture is with youth, I keep expecting to resent getting older—but so far, I never have. I love getting older! That said, one thing that strikes me about “Stressed Out”—one thing that makes it relatable, I think, even to non-Millennials and those blissfully free of student debt—is how easily it works as, yes, A Metaphor.

And not just for young people.

To backtrack a tiny bit: I’ve recently gotten interested in the idea of age as a social construct as opposed to a biological fact. Phases of life regulated by the cold, hard math of time’s passage are being challenged by a whole host of cultural shifts, from the rise of emerging adulthood to the availability of plastic surgery to the influence of the Kardashians to the collapsing of generations to the general death of adulthood. What does it mean to be “an adult,” right now? The answers used to be pretty easy: home ownership, marriage, kids, turning 21. They are no longer easy. People may still be turning 21, but otherwise: Home ownership is declining. Marriage and kids, if they come at all, are coming in general later than they used to.

And while that is wonderfully liberating on an individual level—if I have kids, I want it to be because I truly want them, not because I’m unlocking a Life Achievement merit-badge—it leaves many in a state of confusion about what growing up, or “coming of age,” actually entails. (Our colleague Julie recently wrote awesomely about all that.)

I think “Stressed Out” is tapping into all of that Adulthood Anxiety. Its narrator is doing what so many of us do now, which is to define adulthood by way of childhood. (Did you read all those stories about Adult Preschool in Brooklyn? I mean: #Brooklyn, yes, but also: They were on to something, I think!) And “Blurryface,” a synonym for “Anyone,” is also talking about really common anxieties that transcend age and generation. “Student loans,” after all, is fundamentally that most pervasive of things: “debt.” And many, many of us, whether we’re students or car-owners or parents whose kids have an annoying tendency to outgrow their clothes, know what the omnipresent baggage of debt can feel like.

Same, too, with the treehouse: It’s a structure of nostalgic youth, definitely, but you could also read it as an invocation of Escapism more broadly: the basic-cable procedural the 60-year-old woman watches to unwind after work; the beer the 70-year-old man looks forward to during an overtime shift at the factory. The ways people find to deal with the fact that they can’t retire, that adulthood’s responsibilities—responsibilities that, it used to be promised, have an expiration date—keep going well into the years formerly known as “golden.”

Who knows, non-Millennials might hear “Stressed Out” and dismiss it as a protest of over-indulged youth, or the whining of kids who haven’t yet learned, and perhaps never will learn, the quiet dignity of hard work. I’d wager, though, that they’d hear something familiar in the song’s despair, something resonant in its desire to return to a time that is simpler, easier, and more hopeful. A time when youth could afford to be young—and when age, just as importantly, could afford to be old.

Friedersdorf: You’re right that the desire to return to a simpler, easier, more hopeful time is close to universal. And when you wager that “Stressed Out” appeals to many when it taps into that––when you say that even older people would “hear something familiar in the song’s despair,”––I wouldn’t bet against you. But I’d wager that when they do yearn for simpler times, they aren’t thinking of being sung to sleep.

They don’t want to go quite that far back.

That factory worker is nostalgic for the “Summer of ’69,” before the band broke up, when he met the love of his life at the drive-in. Or the “Glory Days” that Bruce Springsteen sang about. Or days when the rain came, when he went down in the hollow. Or even just sneaking out mother’s backdoor with those hoodlum friends of his.

I’d wager that most older listeners better know what they’re stressed out about too. Whereas I don’t think Blurryface knows the real source of his stress. Notice his fantasy is a lullaby in a world where nothing matters, not a windfall to pay off his debt. He’s unsure, I think, of what matters in life. And not knowing is what has him stressed out, because he cares what others think and worries that they’re judging him.

You mentioned that the markers of adulthood are changing: “The answers used to be pretty easy: home ownership, marriage, kids, turning 21. They are no longer easy. People may still be turning 21, but otherwise: Home ownership is declining. Marriage and kids, if they come at all, are coming in general later than they used to.”

So many decisions! Of course I relate to feeling stressed about which ones to make. But, devil’s advocate: Surely the generation that was married with kids and a mortgage at 25 (or off fighting in World War II or Korea or Vietnam) had a lot more to be stressed out about than the one with more student debt but also a whole extra decade when they’re not responsible for anyone else’s life beyond their own. The answers used to be easier because there was no option but living a harder life.

I’m not criticizing the younger cohort. I am them. I spent my 20s responsible for no one but myself. And there were stretches where I was every bit as anxious as Blurryface. I just wish I could go back and tell myself to chill out; to keep things in perspective by remembering the cosmic joke that sooner or later, we’ll all die, as will everyone we know and love (yikes!); that even before that, life will give all of us terribly concrete problems; that failing to navigate one’s 20s optimally is not among them, even though for many there’s self-imposed pressure to excel or not disappoint.

Now, existential dread about what to make of one’s life isn’t a new phenomenon. I’ve read my Anna Karenina and Sons and Lovers and Middlemarch. I’ve listened to Pet Sounds and seen The Graduate. And struggling to find one’s place isn’t a bad thing, in moderation. Still, I worry that people who spend their 20s stressing over inchoate, existential fears will look back, when they have marital strife or a special-needs kid or an overdue mortgage or an arthritic knee, and realize they let awesome years pass them by and don’t have a “Summer of ’69” to look back on wistfully.

This is my theory of “Stressed Out.” Blurryface doesn’t need to wake up and make money. He needs to wake up and realize that he needn’t stress about what others think, because they’re not judging him so much as quietly sharing the very same anxieties. This is the song’s contribution. It’s a reminder that we’re not alone in our insecurities, even if it isn’t fleshed out enough to offer more than implicit commiseration.

Garber: I love that takeaway! Life brings many stresses, but we also have a sneaky way of compounding—and creating—the pressures that life puts on us. That’s the heart of this all, I guess—a kind of pseudo-Buddhist message in song that contains the line “wake up, you need to make money”: Caring can hurt. Keeping up—or not keeping up—with the Joneses can hurt. Living our lives with constant reference to other people is both supremely human and, often, supremely sucky.

I was just reading about Adolphe Quetelet, “the Isaac Newton of social physics,” and the rise of the concept of the “average person.” Its upshot is that normalcy, like so many things we take for granted, had to be, essentially, invented. And Quetelet’s attempts to define what made a person average—and, by extension, above and below average—were ultimately (and totally unsurprisingly) as confining as they were liberating. Defining what’s “normal” almost demands that you define what’s abnormal. And treating averageness as a scientific fact encourages people not just to strive to be exceptional, but also to strive toward conformity.

Your theory of “Stressed Out” taps into all that. Blurryface is reacting not just to very real social and economic circumstances, but also to perceived cultural pressures that are, frustratingly, as blurry as they are broad: in this case, “success,” “adulthood,” “manliness,” etc. To make matters worse, those pressures are transforming very quickly right now. What does success even look like anymore? What does adulthood look like? How does one become a man, or a woman?

We used to be able to understand our status through rituals (religious ceremonies, graduations), purchases (cars, homes), and relationships (spouses, kids). We still do, to some extent, but much less so than before. So we look to our peers, and to things we might call micro-attainments—buying a couch, becoming a godparent, taking a really awesome Instagram at a really nice restaurant—to mark our progress. We measure those tiny attainments against our friends in a Sisyphean effort to be normal and exceptional at the same time. We care what other people think—because that’s the glue that holds society together, and also because other people are, at this point, the last best gauge of our own status.

No wonder we’re all stressed out.

March 19, 2016

The Paradox of Daredevil

What is Daredevil, really? Is it a superhero show? Is it bloody torture porn? Is it a complex metaphor about religious guilt, Catholicism, and the impulse to “save” others by persuading them of their inner morality? Is it a lesser entry in the Marvel franchise weighed down by thudding pacing, unconscionably wooden dialogue, an unimaginative concept, and one-dimensional characters?

You might ask yourself these questions while watching season two, which was released in its entirety on Netflix Friday, and ponder why Daredevil, at this point in time, seems so much less inspired than Jessica Jones, which came out seven months after its Marvel universe sister show in 2015 but seemed light years ahead of it in vision and execution. While JJ was a gloomy, noir-ish detective show with powers thrown into the mix, it felt like a superhero show for its time, exploring issues like the meaning of consent, the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder, and the dynamics of power in same-sex relationships. Daredevil, by contrast, is … about a man with a savior complex who wrestles with the morality of violence, which the show portrays in gruesome, prolonged, visceral ways. In other words, it’s most superhero dramas, but clunkier, albeit with explicit, often fascinating nods to theology thrown into the mix.

Season one offered a simple enough origin story for the vigilante hero known as the Devil of Hell’s Kitchen. Matt Murdock (Charlie Cox) is a lawyer blinded in childhood by an accident involving radioactive chemicals that simultaneously heightened his other senses, particularly his hearing. His father, a boxer, was killed by a local gangster for refusing to lose a fight he was ordered to fix, after which young Matt was trained in martial arts by Stick (Scott Glenn), one of two important mentors in his life (the other is his priest). The first season leads toward his fully becoming Daredevil, as he fights a vicious local crime boss, Wilson Fisk (Vincent D’Onofrio), acquires a costume that doubles as body armor, and fights a variety of crooks, mobsters, and ninjas, nearly getting killed an exhausting number of times.

Cartoonish violence suffused the first season, and continues to define the second. If Netflix has a single problem with its dramas, it’s that they pad out 30 minutes of television into 50-minute episodes; on Daredevil, this means that fight scenes become feats of endurance, forcing the audience to watch a vulnerable human hero being pulverized over and over again. Season two doubles down by introducing the Punisher (Jon Bernthal), the series’s most compelling character to date, but also one who kills and maims with alacrity, and who amplifies the ferocity exponentially. When Irish gangsters are shot, blood explodes out of their bullet wounds in slow-motion spurts. One stabs another in the eye with a screwdriver, and twists it as you hear his skull crack open. The camera pans out slowly to reveal that we’ve been watching a scene unfold through a gaping bullet hole in a corpse. Matt, as Daredevil, finds a freezer full of Mexican cartel members slung up on meat hooks, their intestines spilling out of their bodies.

By the time a character’s tortured with an electric drill, which penetrates his foot as his bones and muscle tissue spill out, it’s clear that this is torture porn of an unmistakably Catholic variety. The holes forced into hands and feet. The way the camera lingers on a crucifix above Matt’s bed in a flashback to his childhood illness. The obsessive focus on his physical scars, and on the ritual maiming of the show’s heroes. But it’s also violence that’s sexually charged, and riddled with fears about emasculation (in one scene, Punisher chains Matt to a wall and repeatedly refers to him as “Red,” as if he were Joan Holloway offering coffee). By contrast, the show is skittish to the point of awkward about its hero’s sex life, or complete lack thereof.

JJ was open and unapologetic about its character’s sexual encounters; Daredevil is painfully chaste—a kiss in a rainstorm is visualized as an adolescent, hearts-and-flowers fantasy, while a flashback scene of Matt making love to his college girlfriend, Elektra (Elodie Yung) consists almost entirely of shots of Elektra shaking her hair in circles. (This isn’t sex so much as a shampoo ad.) Part of the problem is Matt’s lack of chemistry with his ostensible love interest, Karen Page (Deborah Ann Woll), but it’s also the fact that the only kind of lust the show is compelled to explore or act upon involves blood.

In many ways, Daredevil seems to represent the paradox of modern entertainment, where sex is taboo but violence is cheap.

In many ways, Daredevil seems to represent the paradox of modern entertainment, where sex is taboo but violence is cheap, and readily acceptable even on network television, let alone via Netflix. (It’s telling that Marvel mandated that Jessica Jones not feature nudity, or the word “fuck.”) But the problem also seems to point to a lack of clear vision for what the show is, or could be. Daredevil was conceived by Drew Goddard, who wrote the first two episodes of season one, but stepped down a year before it premiered, and was replaced as showrunner by Steven S. DeKnight. For season two, the writers Doug Petrie and Marco Ramirez replaced DeKnight, with Goddard continuing in an advisory role. (All 14 directors credited for the show on IMDB are male; all but one of the show’s 21 writers (Ruth Fletcher) are too, which may be why all of the eight episodes I’ve seen of season two so far fail the Bechdel Test.)

This swapping in and out of bosses might be fairly common in television, but most prestige dramas (which Daredevil and Netflix clearly aspire to emulate) share one thing: a creator with a singular concept. Daredevil’s messiness is no accident—its dramatic inconsistency, patchy writing, spotty visuals, and maddening pacing clearly seem to point to a case of too many cooks. Jessica Jones, by contrast, owes its psychological richness and narrative depth to its creator, Melissa Rosenberg, who’s spent much of her career fighting what she describes as a “boy’s club mentality” in TV’s writing rooms. What’s clear from watching Daredevil is that this mentality isn’t just bad for women—it’s bad for television.

Many will argue that Daredevil is simply a difficult character: Being tortured by Catholic guilt isn’t quite as compelling a character trait as having your entire family murdered in front of you (distressingly common in comic books). (Plus, his costume is dorky.) But it’s also all too easy for studio bosses and writers to take existing properties, add sophisticated visuals, and shoehorn in excessive brutality to add edge. It’s easy, and as Daredevil proves, it makes for remarkably lackluster entertainment.

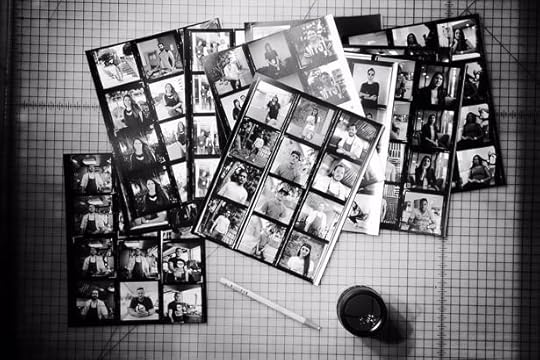

Puerto Ricans, Reframed

Edwin Torres describes his portraits of Puerto Rican Millennials as “a project about hope.” The 26-year-old photographer produced his series with help from a grant from The Ground Truth Project, a non-profit that offers narrative storytelling grants to young journalists. “A lot of these young people I’m photographing, their futures are uncertain, my future is uncertain,” Torres says. “But there’s lot of light that they’re emanating and putting out into the world.”

The black-and-white images are striking, yet simple. Their focus is on the people Torres photographs: a broad range of characters including doctors, hackers, and food truck entrepreneurs. Some are unemployed and looking for work. Some are college dropouts. One poses at a tech conference on the island, and another stands in the classroom where he teaches in The Bronx.

Torres’ work is informed by his personal background—he was raised by Puerto Rican migrants in the Hunts Point neighborhood of The Bronx. It also reflects Puerto Ricans’ complicated history both on the island and in the mainland United States. “Us Puerto Ricans, we’re a really prideful people, and we love our culture because we’re such a mix of so many different cultures,” Torres says. “But with that pride in our culture, and that richness, comes a lot of complexity ... When I’m in the U.S., I feel like a Puerto Rican even though I was born in New York. Going to a liberal arts private school, I felt like the ‘other.’ When I go back to the island I’m an American. You don’t really have a home anywhere you go, so you’re always in flux, in between.”

In the 1960s, Puerto Ricans moved to New York City in large numbers in search of jobs. Many were already mired in generational poverty by the collapse of the island’s sugar cane industry at the end of the 20th century. But they didn’t necessarily find the prosperity they were looking for in the U.S. In 2000, a report by the Community Service Society of New York found that young Puerto Ricans were faring far worse than other Latinos in New York, with “rates of school enrollment, educational attainment, and employment lower than any other comparable group.”

Today, the island remains in economic crisis. In January, it defaulted on payments for its massive debt for the second time in five months. As Puerto Rico continues to slip into recession, many residents on the island have chosen to move, more recently in record numbers, to the mainland. Last year, 84,000 people left the island for the U.S., a 38 percent increase from 2010, according to Pew Research Center.

In the midst of this moment, Torres hopes his project can serve as a “visual dialogue” between young Puerto Ricans on the island and those on the mainland, as both groups navigate a socioeconomic climate shaped by a history of poverty. To encourage this, he shares the portraits on social media and plans to exhibit them towards the end of the summer. Ultimately, he hopes other young Puerto Ricans today, wherever they are, see these stories and find inspiration, connections and a sense of community, despite the ocean separating them.

Torres shoots his portraits on a 30-year-old Hasselblad medium format film camera, which forces him to slow down and adjust his settings manually. He develops the black-and-white film himself in the basement of the Bronx Documentary Project, a nonprofit photography and film space where he also volunteers. It’s a painstakingly slow process compared to shooting digitally. Each roll he shoots makes just 12 images, so he has to be particularly thoughtful about each frame so as to not waste the expensive film. But his pace is intentional. “I thought it was the best way to do it to pay tribute to the people,” Torres says. “A medium-format black-and-white portrait empowers them, makes them look like they deserve the space on this negative.” The decelerated process also lends an air of intimacy to the images. With the extra time spent setting up the shot, Torres’ subjects can become comfortable with him as they share their stories.

Torres associates his project with the Spanish slang word pa’lante, which roughly translates to “onward” or “forward.” “As minorities, we tend to think less of ourselves or be less confident about the fact that our stories matter,” he said. “And I’ve felt that throughout times in the project as well. I keep reminding myself, no, it does matter, people need to see this stuff.”

“We need to see stories of hope every once in awhile,” he says.

Michelle Obama and L.A.’s Cool Girls: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Hustle Is a Political Act: Michelle Obama’s SXSW Keynote Shifted the Spotlight

Ann Powers | NPR

“Selecting two of hip-hop’s most beloved and influential female artists as her peers, Obama quietly suggested that a problem usually viewed as still to be solved can be recast, at least somewhat, by taking a different historical view. For a couple of hours, a different vision of music and popular culture dominated, one with women of color at the absolute center, and it didn’t feel unrealistic.”

Inside the Elite, Super-Secret World of L.A.’s Coolest Girls on Facebook

Kristen V. Brown | Fusion

“If you get invited into ‘Girls Night In,’ it will probably change your life. It’s like joining a sorority—a digital sisterhood where women vent, fight, offer advice, trade tips, crack jokes, and critique each other’s selfies. It’s an interactive, communal diary, and a support group for womanhood.”

‘Bro’-liferation

Wesley Morris | The New York Times Magazine

“The deployment of ‘bro’ as a means of disparagement is part of a generalized expression of fatigue with the wielding of white-male power, a feeling that has emboldened Clinton supporters. We’re no longer talking about the classic bro. We’re talking about trolls and, in lieu of a less printable word, jerks.”

Authoritarian Hold Music: How Donald Trump’s Banal Playlist Cultivates Danger at His Rallies

Chris Richards | The Washington Post

“And while the pundits have enjoyed some high-quality giggles over the quirkiness of Trump’s song selection, what matters far more is how this music shakes the air, how it shapes the psychology of the room … If anything, this is an important reminder that once a tune leaps off a singer’s lips, it becomes a sort of public utility, a container that can be filled with opposing ideas. Ultimately, a piece of music represents whoever’s listening to it.”

Why Better Call Saul Is the Anti-Breaking Bad

Matt Zoller Seitz | Vulture

“Money, status, satisfaction, and the possibility of behaving ethically in an unethical world are always at the heart of the characters’ choices … But it works because we have such affection for this world and these characters, and because every character struggle is ultimately about self-discovery, affirmation, and the unrelenting difficulty of surviving in a brutal, 21st-century economy.”

All Hail Comedy’s Takeover of TV

Maureen Ryan | Variety

“There’s a beguiling friskiness percolating through the TV comedy world right now: Dozens of shows feature open-hearted curiosity, a quiet devotion to craft, a willingness to break form, and an excitement when it comes to subverting expectations and trying new things. Comedies go to sad or even tragic places, and everywhere you look, there’s great physical comedy, sharp wordplay, weird sex, buoyant silliness, understated despair, and a sense of wonder. ”

Making Museums Moral Again

Holland Cotter | The New York Times

“It could wake people up; compel them to stop, look, and read when they might have passed by; and prompt them to see that art isn’t just about objects—it’s about ideas, histories, and ethical philosophies that they may have a stake in, and an opinion about. It seems to me that one point of museum programming is to get people to think, as opposed to endlessly snapping selfies.”

I Want You Still: Celebrating 40 Years of Marvin Gaye’s Sensual Classic

Jason King | Pitchfork

“Like no other record before or since, I Want You captures the distilled feeling and aesthetics of black sensuality, sex, and simmering erotic desire—right down to the seductive bump ‘n’ grind cover art by the late great Ernie Barnes. With its ambient soundscapes, yearning melodies, experimental tempos, elegant chord changes, and haunting lyrics, the album is, for my money, the sexiest rhythm and blues record ever made.”

Historical Fiction and the New Literary Taboo

Pauls Toutonghi | The Millions

“Walter Benjamin wrote that it is ‘more arduous to honor the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned.’ And there are a number of novels, right now, that are balancing these antipodes—that take significant, well-known historical moments, and show them through the lens of nearly powerless, ‘nameless’ protagonists. Through individuals buffeted by the afflictions of their age.”

Krisha: How a Home Movie Became an Indie Film Sensation

David Ehrlich | Rolling Stone

“It was also perfect for his highly autobiographical portrait of addiction that would rather examine raw wounds under a microscope than pretend that they aren’t still bleeding. Taking ‘write what you know’ to the next level, Krisha not only digs up a tragic episode from Shults’ recent family history—it stars the actual people who survived it.”

How Meaningful Is the ISIS 'Genocide' Designation?

After months of reviews and investigations, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry declared on Thursday that the atrocities committed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria amounted to “genocide.” It was just the second time in history the executive branch has ever attached that designation to an ongoing crisis.

Kerry’s statement, delivered just hours before a deadline put forth by Congress, inspires a new set of questions. Chief among them: Now what?

Following the speech, a senior State Department official clarified that Thursday’s declaration placed “no new obligations” on the United States in its ongoing campaign against the terrorist group. So what specifically is the purpose of the designation? It depends on whom you ask.

Cameron Hudson is the director of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the U.S. National Holocaust Museum, which was among the many institutions and organizations to lobby for the designation. Hudson called it a “good first step.”

“The designation is significant because we’re acknowledging not just the suffering of people on the ground, but we’re acknowledging that ISIS is more than just a terrorist group,” he said on Thursday. “It’s now a genocidal group that poses a national security threat to the United States, of course, but poses an existential threat the people who are tapped in their crosshairs and who are in the areas that they control.”

In other words, he added, the declaration represents a potential shift in U.S. thinking whereby ISIS transcends its definition as a traditional counterterrorism target and those entrapped by the group transcend their definition as traditional victims of a proximate war. Hudson added this historical note:

This harkens back to the Holocaust where the idea of saving Jews was not part of our war strategy in World War II. To the extent that we were going to save European Jewry, it was by winning the war and in the time that we made those statements, the Holocaust happened.

The idea that we can eliminate a genocidal threat simply by defeating ISIS, I’m concerned that this threat is going to continue and that more and more people are going to be eliminated in the time it takes to wipe out ISIS. I think the argument we would make is that we need to be doing both at the same time.

Eric Morris, who formerly worked for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and now teaches at Stanford University, was a little less sanguine about the designation.

He suggests that in the past, the debate over whether a crisis does or does not constitute genocide “was actually a way of delaying action” in the eyes of critics. Once declared, either by advocates or administrations, the designation does not always translate into action.

“When people use the word ‘genocide,’ at least implicitly, there is some kind of assumption that some form of obligation is involved, certainly for states that have signed onto the Geneva Convention,” Morris told me. “But the reality is that they have very, very imperfect obligations and that’s where the problem lies.”

Writing in The Atlantic back in 2011, Rebecca Hamilton noted the response of Warren Christopher, who served as secretary of state under President Clinton, to a question in 1994 about whether the ongoing massacres in Rwanda merited the designation. “If there is any particular magic in calling it genocide,” Christopher said, “I have no hesitancy in saying that.” (Hamilton notes that Christopher and the Clinton administration, scarred by the Black Hawk Down disaster in Somalia, avoided a formal declaration at all costs.)

Say the United States does use the genocide designation to seek to involve the UN Security Council, establish war-crimes tribunals, or push to have cases referred to the International Criminal Court, “the second problem,” Morris notes, “is that you have imperfect institutions.” (Hudson remarked that the two bills that overwhelmingly passed through the House earlier this week calling for the genocide designation and war-crimes tribunals were noteworthy because of Congress’s general skepticism about international justice.)

While Morris did concede the declaration is useful because it allows for these options, looking back at the only other time the executive branch of the United States government has ever formally declared a genocide in real time does not make for a heartening precedent. After facing months of pressure to declare the crisis in Darfur to be a “genocide,” then-Secretary of State Colin Powell said this to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in September of 2004:

Mr. Chairman, some seem to have been waiting for this determination of genocide to take action. In fact, however, no new action is dictated by this determination. We have been doing everything we can to get the Sudanese Government to act responsibly. So let us not be too preoccupied with this designation. These people are in desperate need and we must help them. Call it civil war; call it ethnic cleansing; call it genocide; call it "none of the above." The reality is the same. There are people in Darfur who desperately need the help of the international community.

“So the question is,” Morris posits, “Is the Kerry statement more or less like the Powell statement?”

March 18, 2016

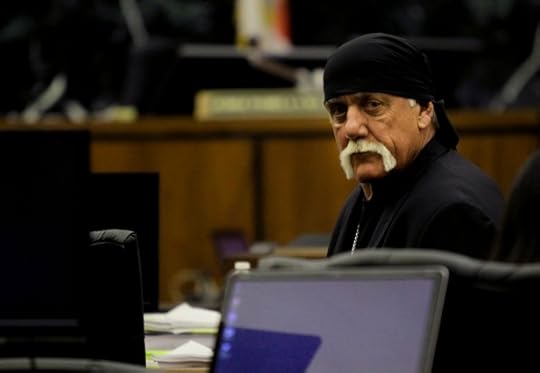

In First Round With Gawker, Hulk Hogan Prevails

Updated on March 19 at 1:20 a.m. ET

A Florida jury awarded Hulk Hogan $115 million in his lawsuit against Gawker Media for publishing part of a sex tape of him four years ago, handing the retired pro wrestler a resounding victory as the legal battle moves to the appellate courts.

Jurors found that the New York City-based outlet acted with reckless disregard when publishing the clip and awarded Hogan a hefty sum in compensatory damages: $60 million for emotional distress and $55 million for economic injury. That total could rise when the jury reconvenes to deliberate and award punitive damages.

In his lawsuit, Hogan accused Gawker of violating his privacy by publishing a one-minute and 41-second clip from a sex tape between him and a friend’s wife. Hogan said had been recorded without his knowledge or consent in 2007. He also sued the woman and her husband over the tape’s release; the two sides settled out of court.

Gawker said an anonymous source mailed them the tape years later, which then-editor-in-chief A.J. Daulerio published in 2012 with the title, “Even for a Minute, Watching Hulk Hogan Have Sex in a Canopy Bed Is Not Safe for Work but Watch It Anyway.” (Editors later excised the footage from the post, but not before it had been viewed five million times.)

While taking the stand during the two-week trial, Hogan testified that the footage’s release “turned my world upside down,” leaving him depressed and “completely humiliated.” Jurors deliberated on the verdict for six hours. Hogan openly wept as it was read.

“We’re exceptionally happy with the verdict,” Hogan’s lawyers said in a statement. “It represents a statement as to the public’s disgust with the invasion of privacy disguised as journalism. This verdict says no more.”

Gawker’s lawyers countered that Hogan’s frequent discussions of his sexual exploits—in interviews, autobiographies, and the like—made the tape a matter of legitimate public interest. They also warned of chilling First Amendment implications for journalism if Hogan’s lawsuit against them prevailed.

Nick Denton, the founder of Gawker, defended Daulerio’s decision to publish the article. “He made a contrast between an American icon and the man behind the icon,” Denton told the jury during his testimony. “And he made a self-critical point about the public's obsession with celebrity sex tapes and his own interest.” Gesturing to the constitutional aspect of the case, he also told the court that public interest “usually trumps a celebrity’s privacy.”

Beyond press-freedom concerns, the case’s sheer costs also loomed over Gawker as an existential threat. The New York Times reported last year that the site had to pay its legal fees in the Hogan case out of hand after exceeding its insurance cap. Denton also told the Times that there was a one-in-ten chance he would have to sell a controlling interest to keep the company solvent.

Gawker’s legal strategy always hinged on the appellate courts, which could be more favorable terrain for the company when raising First Amendment concerns and less susceptible to the case’s more salacious aspects.

“Given key evidence and the most important witness were both improperly withheld from this jury, we all knew the appeals court will need to resolve this case,” Denton said in a statement. The jury found him and Daulerio personally liable in their verdict.

Denton added that he “feels very positive about the appeal that we have already begun preparing, as we expect to win this case ultimately.”

Truth as Marketing: Gwen Stefani’s Pop Confession

In the press tour for her new solo album This Is What the Truth Feels Like, Gwen Stefani has told a few interviewers that she never planned on fame. When her band No Doubt released its commercial breakthrough Tragic Kingdom in 1995, “We knew we were making music that couldn’t get on the radio,” she said to EW. “It was pop in the middle of grunge—it made no sense!”

The notion of pop music as underdog might seem jarring today. But it’s true that in the mid-’90s, No Doubt’s brand of catchiness must have felt new. The authentic-seeming angst that had beat back synthpop and hair metal a few years earlier in the zeitgeist had started to feel like just another gimmick. No Doubt was everything the Nirvana knockoffs weren’t: airy, lively, vulnerable, feminine. Pop’s claim to honest expression is often asterisked by the specter of commercial calculation, but in the early days—watching, say, the “Don’t Speak” video—it felt like you could believe No Doubt.

Stefani very much wants people to believe her again. The pitch for This Is What the Truth Feels Like—from its name to the music video where Stefani tearily stares in the camera in one take—is that it’s the rare pop album where you’re not supposed to guess about the difference between art and author. She has said she initially set out to “curate a record … like every other pop girl does”—probably by enlisting Swedish songwriters and knocking out the vocals in a few afternoons—but scrapped the results after her 14-year marriage to the Bush frontman Gavin Rossdale imploded in 2015. Real life had happened; real music should result.

This may be an admirable artistic goal, but in a strange irony, its real significance may be as a marketing move. This Is What the Truth Feels Like does not sound like a departure for Stefani or for anyone seeking radio play at the moment. Instead of whatever industry pros she ditched after recording that earlier set of songs, she teamed up with … industry pros fresh off of No. 1 hits from Justin Bieber and Adele. A large portion of the album is presumably inspired by her new boyfriend Blake Shelton, the country star and fellow judge on NBC’s The Voice. Even in this, the notion of truth has been rendered janky thanks to the celebrity marketplace: Rumors about the rumors about “Gwake” say that it’s all a fauxmance to boost ratings; Stefani even cheekily endorsed that conspiracy theory in the period before she and Shelton went fully public. So, like with the average Taylor Swift or Bieber release, the fun of this album is improved by reading the tabloids.

In any case, Stefani’s recent drama helps her take a crack at doing what great love songs are supposed to do: nail a micro-moment or peculiar dynamic within a universal experience. Heartbreak-to-uplift is a common trope, but Stefani reinvigorates it a few times here by foregrounding feelings of surprise and gratitude. “Make Me Like You,” a strong single that adds a dash of her signature pout to Sheryl Crow strumminess, neatly charts three distinct emotional phases in verse, pre-chorus, and chorus. “Hey, wait a minute / No, you can’t do this to me,” she protests to an exciting new love interest during the second phase, perhaps also speaking for anyone trying to resist the song’s charm. On “Truth,” she acknowledges that everyone is going to write off her new squeeze as a rebound—a canny move, though somewhat ruined by a misplaced hint of raunch in the line when she commands that squeeze to “rebound all over me” (it’s not the only awkward maybe-double-entendre on the album: “I need some water, so water me” she says later).

The music—let’s call it “acoustic-tronica lite-reggae dancepop”—is uniformly crisp and tuneful, with occasional inventive touches. The album’s at its best when it uses its star’s distinctive voice for moments of multi-tracked beauty or play; often there’s a lovely sensation of floating upwards, as when Stefani coos the title of “Rare,” the album-closing ode to joy. On “Favorite,” an electro-toybox twinkle recalling “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” complements Stefani’s lyrics about romantic exploration.

But in other places, the professional polish does not serve the subject matter. A couple of songs clearly try to recapture the rude energy of “Hollaback Girl” or Rock Steady, but end up recalling the strained, cringe-worthy provocations of Iggy Azalea and recent Madonna. Most heartbreaking is “Used to Love You,” both because of its sentiment and its execution. Stefani has repeatedly told an anecdote about her record label complaining that the album had no hits and then going gaga with praise once she sent them “Used to Love You,” which she says is one of the most personal songs she’s ever written. Unfortunately, the results feel born of compromise: A raw observation and vocal squeak in the chorus might prompt tears like the ones in the accompanying video, but the rest of the song struggles, incongruously, for light toe-tapping. It should have been a true ballad.

Ultimately, the album succeeds and fails not on the amount of truth involved, but the amount of musical inspiration involved, which is mild. Stefani, of course, is not the first person to approach the public with the pretense of breaking with convention and then offering a mostly conventional product. The opening song, “Misery,” describes a head rush that you can’t find “at the grocery store.” Whatever that feels like, she hasn’t quite approximated it here.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower