John Bengtson's Blog, page 11

November 6, 2019

How Mary Pickford Filmed Daddy-Long-Legs Part Two

[image error]In Daddy-Long-Legs (1919) Mary Pickford portrays an endearing young orphan later sent to college by an anonymous benefactor. Complications ensue when Mary meets her sponsor, unaware of his status, and they fall for each other. Pickford’s most financially successful production to date, this charming film reveals surprisingly varied glimpses of early Los Angeles history as described below.

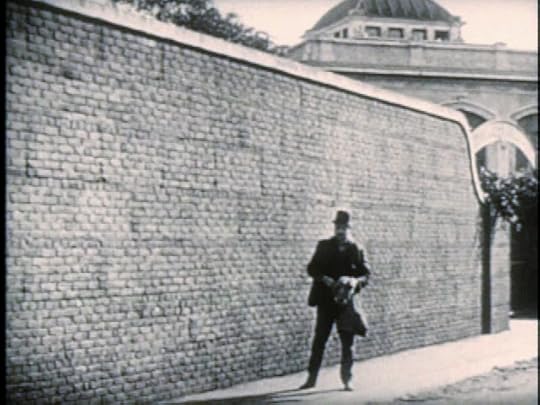

As revealed in Part One, Mary’s orphanage (upper left) was the same former Occidental College Hall of Letters building Charlie Chaplin would later use to portray a maternity hospital at the beginning of The Kid (1921) (lower left). The former college building was abandoned when Occidental moved to its new, larger Eagle Rock campus in 1914. By 1919 the hall had been vacant for years, and was perfectly cast to portray Mary’s orphanage. Mary filmed here first. You can read all about the deserted campus, and true orphanage locations HERE.

Mary’s 1919 production also traveled far and wide, from Malibu, to downtown, to a fashionable neighborhood near her own home at the time. Two beautiful mansions appearing in the film survive intact.

[image error]When wealthy trustees visit the orphanage, spunky Mary has a run-in with their spoiled brat daughter. Above, the family arrives back home at 450 S. Lucerne in Windsor Square, built in 1915. As seen to the left in this 1920 view north (click to enlarge), this Lucerne home (top box) stood just three blocks from Mary’s home in Fremont Place (bottom box), due south of Wilshire Blvd. running left – right. HollywoodPhotographs.com. Mary leased this home for a year in August 1918, moving out a few months after Daddy-Long-Legs premiered.

Above, parked on the 5th Street side of the house, the bratty daughter demands that her parents throw Mary out into the street. Residential historian Duncan Maginnis made this astonishing discovery. Duncan is the author of the amazingly rich and fascinating series of historical blog posts about classic Los Angeles neighborhoods, including BERKELEY SQUARE; WESTMORELAND PLACE; WILSHIRE BOULEVARD; ADAMS BOULEVARD; WINDSOR SQUARE; ST. JAMES PARK; and FREMONT PLACE. You can read more about 450 Lucerne at WINDSOR SQUARE.

Mary departs for college from the stately Southern Pacific Depot, opened late in 1914 (seen above, looking north), that once stood on Central Avenue at 5th. Unlike the far smaller and less formal Santa Fe Depot nearby, the Central Station had underground passages leading to numerous boarding platforms sheltered by distinctive awnings, visible at right. Both depots appeared frequently in early film. USC Digital Library.

Sadly, only narrow glimpses of the station appear in the movie. Above, Mary runs up a ramp from an underground passageway to one of the platforms. Notice the bystander in the central image wearing a conspicuous face mask, a precaution against the Spanish Influenza epidemic (1918-1919) raging during the time of filming. The outbreak cost more lives than were lost fighting World War One.

One of the depot’s twin waiting room clocks, depicted in Daddy-Long-Legs to the upper left, appears to the right in this scene from Souls for Sale (1923), where an extensive sequence was filmed inside the Central Station waiting room.

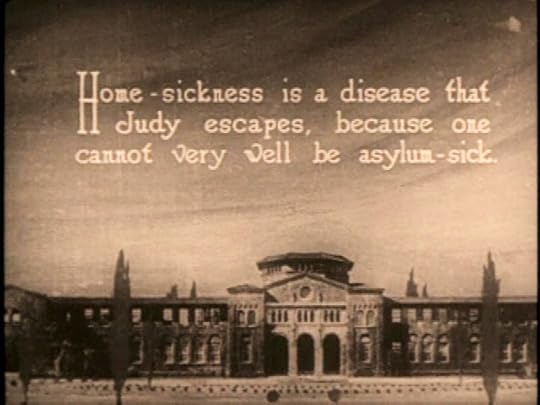

Above, this lovely title card depicting Mary’s college, painted by Ferdinand Pinney Earle, is nearly an exact represenation of the former Milspaugh Hall at the Los Angeles State Normal School, appearing here (right) in Buster Keaton’s 1927 feature comedy College. Located at Monroe Street and Vermont Avenue, the school was designated in 1919 as the Southern California Branch of the University of California (UCLA), before becoming Los Angeles Junior College in 1929 when the Westwood campus of UCLA opened. Still at the same site, the school is known today as Los Angeles City College.

[image error]Mary and her love interest (benefactor) played by Mahlon Hamilton share a quiet moment beside the rock pool at Malibu State Park, then known as Crags Country Club. Exterior filming locations expert Mike Malone, a retired national park ranger who leads fascinating tours and lectures about movies filmed in the Santa Monica Mountains and Paramount Ranch, confirmed the site (see matching red circle detail). The pool appeared in Buster Keaton’s The Paleface (1921) and decades later for scenes from The Planet of the Apes (1968). Color photo Mike Malone.

Click to rotate – 360° view above – when visiting the rock pool today people seem to leave behind their three-piece suits and floor length dresses.

[image error]Click to enlarge – above, a wide view of the once famous Busch Sunken Gardens in Pasadena. Huntington Digital Library. Mary filmed here at least twice, including her graduation scenes from Daddy-Long-Legs.

Mary’s graduation procession strolled along these curved paths at the Busch gardens, paired with a matching 1912 view. Mary had previously filmed many scenes here for Stella Maris as well. Millionaire beer brewer Adolphus Busch built the massive gardens in 1904. The park closed in 1938 and was sub-divided into numerous home sites. Pasadena Public Library.

Above, the closing scene from Stella Maris, with Conway Tearle and Mary beside the Busch gardens mill house. Known as “the Old Mill,” it still stands in Pasadena, part of a private residence. California State Library.

Now a wealthy and successful author, Mary boldly decides to confront her benefactor for the first time. She arrives at his home to repay him in full, and to confide in him that she has met a man she truly loves. All ends well when she discovers her true love and her benefactor are one and the same man.

Above, the benefactor’s home was portrayed by the Stearns residence, still standing at 27 St. James Park. Residential historian Duncan Maginnis, who discovered the Lucerne home above, provides a full history of the Stearns home and its environs at this post HERE.

Similar views as Mary exits the cab in front of the Stearns home, the iron fence and brick details still match.

[image error]Above, the view east from the cab also reveals at back a giant light post that once stood in the intersection of St. James Park and St. James Place. The small, secluded neighborhood was a popular filming site, appearing in several early comedy shorts. Also looking east (upper right above), the light post appears behind Harold Lloyd attempting suicide-by-automobile early in Haunted Spooks (1920). Looking west lower right above, towards the Stearns house to the far right, the back of the light post appears in Snub Pollard’s Where Am I? (1923).

Site of the happy ending, the benefactor’s home at 27 St. James Park.

October 23, 2019

Chaplin’s Earliest Scenes Beside the Selig Studio

When Charlie Chaplin began his film career at the Keystone Studio in 1914, the Selig Polyscope studio (above) stood just two blocks to the north, sandwiched between Clifford and Duane Streets along Allesandro (now Glendale Boulevard) in Edendale. Opening in 1909, Selig was reportedly the first permanent movie studio built in Los Angeles. I was unfamiliar with Selig, but when I first noticed it in a vintage photo, I realized it was the setting for several scenes from Chaplin’s Keystone career.

[image error]This rare photo looking NW, conveniently featuring a Clifford/Allesandro corner street sign, reveals the Selig Studio was enclosed by a stucco wall sloping uphill and topped with distinctive miniature turrets. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

A similar wall sloping uphill with matching turrets appears above as Charlie flirts with a pretty girl during Those Love Pangs (1914). Given the matching elements and its location two blocks from the Keystone Studio, I’m convinced Charlie filmed this scene looking west uphill along the Duane Street side of the Selig studio wall.

Next, using the Love Pangs frame (upper left) as a reference, I’m convinced these scenes from Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914) were also filmed on Duane Street, further uphill, along the back corner of the Selig studio wall. The short lattice fence beside the children in the Love Pangs frame appears clearly here in the Tillie frames. The two homes at back were 2212 and 2216 Duane Street, now the site of modern apartments.

[image error]One discovery often leads to another. During Tillie, Charlie and co-star Mabel Normand seek refuge in a movie theater after stealing Tillie’s (Marie Dressler) pocketbook. They panic when the plot onscreen involves similar thievery, and they find themselves seated next to a detective played by Charley Chase.

After learning that the Selig studio wall facing Allesandro was lined with a series of inset curved arches, it’s clear that the film-within-a-film drama (see above) that upset Charlie and Mabel was filmed alongside the studio wall.

Likewise, this film-within-a-film view from Tillie, above left, shows the Clifford/Allesandro corner gate entrance to the Selig Studio.

A final tidbit, just for fun. While King Vidor’s celebrated “everyman” drama The Crowd (1928) caused a minor stir for daring to show a flush toilet in the background of one domestic scene, often cited as the porcelain appliance’s screen debut, it appears Tillie beat this record by more than a dozen years. There must have been a hardware or plumbing store near the small restaurant where Marie Dressler works during Tillie. The children at back are too fascinated watching Charlie at work to notice they are standing behind a commode, apparently promoted for sale as a sidewalk display.

I detail many other Tillie locations in my book Silent Traces, and other “new” locations elsewhere in this blog (HERE).

Be sure to check out the wonderful Flicker Alley Chaplin at Keystone DVD collection that makes these discoveries possible.

Below, site of the former Selig Polyscope studio at 1845 Glendale Blvd.

October 11, 2019

Harpo, Chico, and James Cagney at the Brunswig Mansion

[image error]Imagine the star power – Harpo Marx, Chico Marx, and James Cagney all once stood on the same mansion front steps. Classic Los Angeles homes frequently played roles in golden-age films, and the former Brunswig Mansion, once standing at 3528 West Adams, appeared in two 1931 productions; Monkey Business starring the Marx Brothers, and Blonde Crazy with James Cagney and Joan Blondell. LAPL.

Above, Harpo and Chico arrive in style, compared to an establishing shot from Blonde Crazy.

The rose pattern window shades match with Harpo, Chico, and Jimmy.

Matching views east as Jimmy exits the Brunswig porch. The Guasti Mansion next door appears at back. You can read a full account of both homes at Duncan Maginnis’s Adams Boulevard blog posts; the Brunswig, and the Guasti.

Although the full Brunswig address was 3528, in both films the final digit “8” appears to have been knocked off of the pillar.

[image error]Although the Brunswig was demolished in 1955, its equally stunning next-door neighbor is still standing, the Gausti Mansion at 3500 West Adams, later owned by movie [image error]choreographer Busby Berkeley, and now home to the Peace Awareness Labyrinth and Garden. Among its many screen appearances, the Gausti is where Laurel & Hardy filmed Another Fine Mess (1930) (read more HERE) and Charley Chase filmed Fast Work (1930) (read more HERE).

Groucho and Harpo would visit another grand mansion to film scenes from Duck Soup (1933) at the Jewett Estate in Pasadena, where Buster Keaton filmed the opening joke from Cops (1922) beside the mansion gate (read more HERE).

Glamorous homes were often leased to studios as filming sites under the Assistance League’s Film Location Bureau, a charity established by Mrs. Hancock Banning. The Bureau maintained a directory of local mansions and estates available for filming. The studios paid rental fees directly to the Bureau, instead of the mansion owner, which the Bureau applied directly for charitable purposes. This efficient scheme for raising money saved studios the expense of building costly sets, and allowed homeowners to contribute to a worthy cause at no expense to themselves. The Los Angeles Times reports that the Film Location Bureau rented out the Brunswig Mansion for use in Pola Negri’s The Spanish Dancer (1923).

September 27, 2019

Early Thrill Comedies – Who Was First?

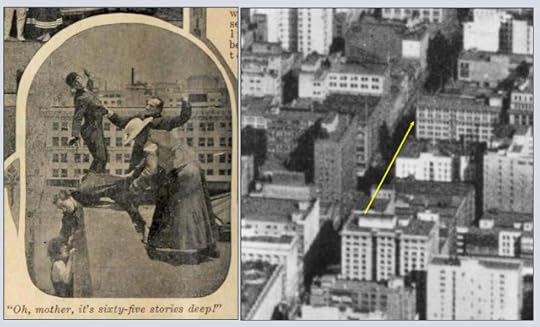

[image error]Thrill comedies featuring a star hanging from the side of a tall building have long been a staple of silent films. The photo at left from Play Ball (1925) eloquently explains the brilliant technique with a single image. Starting with Look Out Below in 1919, Harold Lloyd would become the master of the genre, capped by his masterpiece Safety Last! (1923) that still enthralls audiences today. But when was this effect first used in a movie? I pondered this when film historian Jack Theakston inquired about Ignatz’s Icy Injury (1916), one [image error]of the earliest thrill films of which he was aware. While it would be fun to declare Ignatz the earliest winner, it’s likely the effect had already been employed for years, perhaps as early as by George Melies.

Using Lantern Media to research Ignatz, the L-KO Kompany’s Billy Armstrong comedy promoted at right in Universal’s The Moving Picture Weekly trade magazine, I quickly happened upon two other contemporary L-KO stunt comedies promoted by Universal, Billie Ritchie’s A Bold, Bad, Breeze (1916), and Dan Russell’s Rough Stuff (1917). As we’ll see, these three films share much in common with each other and with other stunt comedies of the era.

Above, the two stunt images from Ignatz touted in the July 8, 1916 Moving Picture Weekly trade advertisement; (left) looking west down 8th at the Hamburger’s Department Store, and south down Broadway (right). Both scenes were staged from atop the 1912 Chapman Building at the NE corner of 8th and Broadway.

Matching views west – the extant Chapman Building (756 Broadway) has a small two story structure on its large rooftop, where Billy Armstrong crawled around presumably with scaffolding or nets below out of camera range, but far from the 13 story drop to the street.

Click to enlarge – above, looking north up Broadway towards the two story structure atop the Chapman (Investment) Building where the filming took place. The “Examiner” Building (orange) and the four tall buildings immediately behind it all remain standing. USC Digital Library.

Ignatz was filmed atop 756 S. Broadway looking south towards the same block appearing north behind Harold Lloyd, where he filmed the clock scene from Safety Last! atop 908 S. Broadway. Notice the opposite views of the Majestic Theater (M), Tally’s Theater (T), and Hamburger’s (M). Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

[image error]

Click to enlarge – next for discussion is Billie Ritchie’s A Bold, Bad Breeze, pictured here in the July 1, 1916 issue of The Moving Picture Weekly. Billie was filmed atop the extant Southern California Gas Company building at 950 S. Broadway, the same rooftop where Harold Lloyd staged the middle sequence of his climb in Feet First (1930). The “JOSEPH’S” wall sign at the left is where the “RADIO SUPPLY CO.” wall sign is to the right. The L.L. Burns building at back is 908 S. Broadway, where Lloyd staged the clock sequence from Safety Last! Both the 908 and 950 buildings remain standing, but a giant modern apartment complex has been built between them. USC Digital Library.

After solving this location the hard (but fun) way, I then found this full view photo depicting the view up Broadway. The white building behind Billie is where Harold Lloyd later filmed the clock scene from Safety Last!

Last comes Rough Stuff appearing in the August 4, 1917 issue of The Moving Picture Weekly. How did they film it? Again, from atop the same two story structure on the roof of the Chapman Building, only this time looking north. The beautiful white Hass Building in the background, at the NE corner of Broadway and 7th, remains standing, but has been “improved” with a modern facade. LAPL.

This other view from Rough Stuff also reveals the Bullock’s Building to the left, still standing on the NW corner of Broadway and 7th.

This absolutely convincing yet low-tech special effect no longer seems to be employed much today. One of the few (no longer modern) examples I’ve found was the 1985 pilot movie for the TV series Moonlighting with Cybill Shepperd and Bruce Willis. Looking south, the rooftop structure just to the right of Bruce is the same stairway entrance structure the cops are standing on, and pictured here to the right, both looking north.

A modern view from the two story structure atop the Chapman Building towards the Hamburger Building. (C) 2019 Microsoft.

September 12, 2019

Harry Houdini Solves a Charlie Chaplin Mystery!

[image error]Harry Houdini helped to discover where Charlie Chaplin filmed crucial scenes for his very first movie Making a Living (1914). The initial scene of Charlie’s entire career (below), discovered by Kevin Dale and reported HERE, was staged in front of a residential porch [image error]adjacent to the Keystone Studio that is now site for the driveway to a Jack-In-The-Box restaurant! The former house at 1722 Allesandro appears in five other Chaplin Keystone films and in many other Keystone films as well.

In his debut role, con man Charlie witnesses a spectacular automobile accident caught on film by a reporter, then steals the camera and rushes downtown to apply for work at a newspaper. Above, Charlie stands at the Broadway side of the former Los Angeles Times building on the corner of 1st Street. The building was then barely a year old, rebuilt after a horrific bomb blast destroyed it, killing over twenty people, during a labor dispute in 1910. My book Silent Traces reveals more locations and history from the film. LAPL.

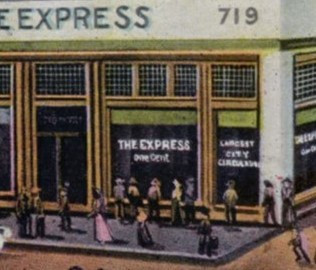

Exploiting the stolen photos, the newspaper churns out “extra” editions of Charlie’s front page story, which he eagerly helps to distribute. Above left, Charlie loads bales of the hot-off-the press edition into the newsboys bicycle carts in the alley beside the paper, and above right, hands out more copies to the newsies at the corner office of the paper, where “LARGEST CITY CIRCULATION” appears conspicuously in the window.

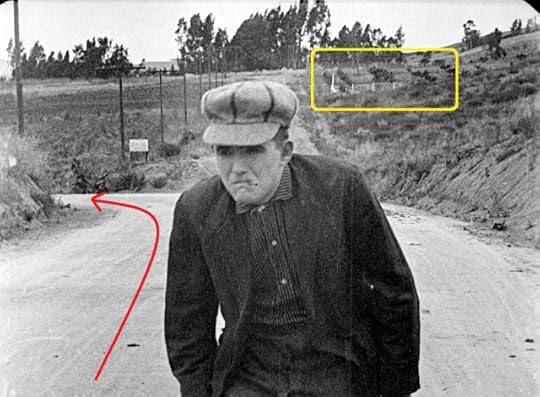

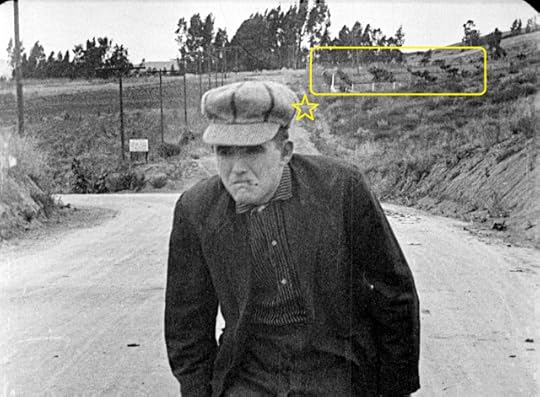

[image error]Despite the paper boasting of its “largest” circulation, its identity, and hence its location, eluded me for years. But then famed magician Harry Houdini, via champion Houdini historian and blogger John Cox, came to the rescue. In John’s recent Wild About Harry post, he proves Houdini performed a suspended straight-jacket escape in downtown LA on December 4, 1915. John writes how this stunt was frustratingly difficult to confirm until he finally located the story searching microfilm of the Los Angeles Tribune at the downtown public library. When Harry accepted the paper’s challenge to perform the stunt suspended from its headquarters building, it made the front page both when Houdini first tested the block and tackle rigging (at left), and again the next day when he escaped the straight-jacket in two minutes suspended in front of huge crowd. The only newspaper reporting the stunt was the difficult to access Tribune itself, because at the time the competing newspapers ignored the story completely. No wonder confirming the story had been so challenging.

[image error]While it was exciting to read Houdini had performed his signature escape in Los Angeles so early in his career, what caught my eye is that the front of the newspaper matched Chaplin’s corner paper office. Founded in 1871, the Los Angeles Express began operating at 719-721 S. Hill Street in 1911, the same year the Los Angeles Tribune morning paper began publishing from the same building. The two papers were later run by the Express-Tribune Company.

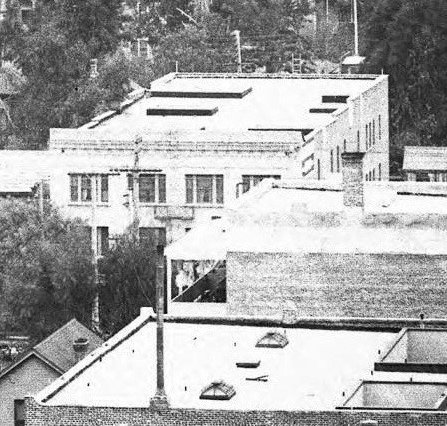

[image error]When Charlie filmed here the Express was the city’s oldest surviving daily paper. The building parapet reads 1871-1910, presumably to honor the years spent at its former headquarters. In 1917 the Express-Tribune Company advertised that the combined circulation for its two papers exceeded 115,000. Other newspapers complained these figures were fraudulent, and filed suit against the owner-publisher E. T. Earl. While some contemporary accounts of the 1917 lawsuit appear in the Los Angeles Times, I wasn’t able to determine its eventual outcome, and Mr. Earl died suddenly early in 1919. The photo detail at left, attributed to November 1917, shows for some reason the building now deserted, stripped of its EXPRESS name and up for lease. USC Digital Library.

Above, matching window details confirm the site. The 1913 postcard comes courtesy of author-historian Brent Dickerson, who manages the absolutely fascinating A VISIT TO OLD LOS ANGELES website, guiding readers up and down each block of 1900-1920 era downtown Los Angeles.

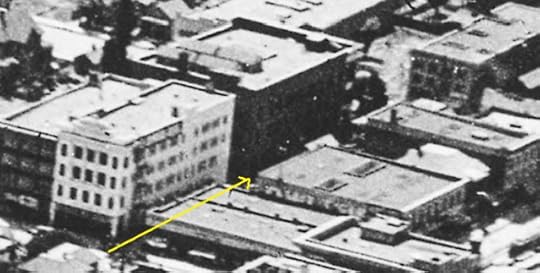

Above, this 1910 aerial view, a snippet of a wide panorama taken from a hot air balloon (!), shows the alley leading west from Hill Street to Olive Street alongside the Express building (arrow). USC Digital Library.

Looking closer, this frame from a different movie print shows two stories of the former Hotel Washington boarding house at 711 S. Olive Street across from the Hill-Olive alley, appearing (right) in this 1907 photo. The hotel was demolished in 1917 to make way for the Coulter’s Dry Good store building (more below), still standing at this spot today. USC Digital Library.

The Hill-Olive alley appearing in the film was defined by five buildings, those flanking each end of the alley, and the Hotel Washington across the street at back (see map, Charlie marked by the star). The area was a booming construction site at the time, and only one of these five buildings (dark gray on map) survives today, the corner at 716-722 S. Olive built in 1906 as headquarters for the Home Telephone & Telegraph Company. The building’s distinctive quartet of pitched roof skylights shown above remain today.

This wider view west down 7th reveals the filming site on Hill Street stood half a block from the Los Angeles Athletic Club at 7th and Olive where Charlie often resided. (Charlie wrote to his brother Syd from the club as early as August 4, 1914). Given the club’s prominent role in Chaplin’s life, and its proximity to where he began his career, it’s easy to imagine Charlie would reflect about his debut filming on Hill Street when visiting the club. Harold Lloyd filmed Never Weaken (1921) on the roof of the Ville de Paris department store (center), built in 1916 after Charlie filmed in the alley. The photo date is attributed to November 1917 – curious, since the center roof sign mentions “1920,” yet the right corner of 7th at Hill stands bare (a demolition permit was pulled in September 1917), in preparation for the future Warner Bros. Downtown – Pantages Theater which began construction there in 1919. USC Digital Library.

Looking east along 7th at Olive, this scene of Charlie and the drunk millionaire driving home in City Lights (1931) was staged across the street from the Los Angeles Athletic Club, and one block from Charlie’s debut performance site beside the former newspaper. The Ville de Paris appears at left, along with the Coulter Dry Goods store (built in part on the former Hotel Washington site around the corner).

Above, a final then and now view looking west at the alley side of the 1906 Home Telephone & Telegraph building, still standing. The Coulter Building, rather than the Hotel Washington, now appears at the far end across the street.

Houdini had connections to Buster Keaton as well, including this scene from Harry’s 1919 thriller The Grim Game (1919), filmed at the Chaplin-Keaton- Lloyd Hollywood Alley. I have several posts about the historic locations appearing in Houdini’s The Grim Game HERE.

Be certain to check out the fantastic Chaplin at Keystone DVD set from Flicker Alley.

Below, the 719 S. Hill Street corner where Charlie Chaplin AND Harry Houdini both once stood, creating history, is now a parking lot. But thanks to the work of John Cox and Brent Dickerson, and the incredible array of resources now available online, we can appreciate Charlie’s sense of what Los Angeles looked like over 100 years when he began his career.

August 31, 2019

How Mary Pickford Filmed Daddy-Long-Legs Part One

[image error]In Daddy-Long-Legs (1919) Mary Pickford portrays an endearing young orphan later sent to college by an anonymous benefactor. Complications ensue when Mary meets her sponsor, unaware of his status, and they fall for each other. In what was Pickford’s most financially successful production up to that time, this charming film reveals surprisingly varied glimpses of early Los Angeles history.

To begin, Mary’s orphanage (upper left) was the same former Occidental College Hall of Letters building Charlie Chaplin would later use to portray a maternity hospital at the beginning of The Kid (1921) (lower left). The former college building was abandoned when Occidental moved to its new, larger Eagle Rock campus in 1914. By 1919 the hall had been deserted for years, and was perfectly cast to portray Mary’s orphanage. Mary filmed here first, well before Chaplin. USC Digital Library.

Mary lines up her fellow orphans along the north, back side of the former hall. The projecting left side of the building in the movie frame was later trimmed flush to the back wall, as confirmed by the 1950 Sanborn fire insurance maps. Also trimmed of its upper floor and peaked roof, the building still stands, a modest apartment block in Highland Park, surrounded by bungalows and strip malls. Color photo Tony Barraza.

Mary chases a fellow orphan east along the south face of the building. The Sanborn fire insurance maps confirm the large projecting porch in the movie frame was removed by 1950. Color photo Brad Alexander.

Mary and fellow orphan actor Wesley Barry pose by the NW corner of the building, essentially unchanged but for the landscaping. Color photo Jeffrey Castel de Oro.

Mary runs beside what was likely a prop wall built for the production, at the back, east corner of the building. Color photo Jeffrey Castel de Oro.

Wesley runs east along the south face – the porch now removed and doorway replaced with the two smaller windows at center. Color photo Tony Barraza.

Upper left, Mary chases an orphan along the east side of the hall, the same side appearing with Edna Purviance in The Kid (center). Notice the matching left drain spout in each vintage image. Color photo Tony Barraza.

Mary leads Wesley back inside the west entrance. Color photo Tony Barraza.

Witnessing the anonymous, long-legged shadow of her benefactor inspires Mary to call him “Daddy-Long-Legs.”

As I detail in my Chaplin book Silent Traces, Presidents Taft and Teddy Roosevelt also visited this campus building. So, Mary, the world’s most beloved actress, Chaplin, the world’s most beloved comedian, and two United States Presidents, all once visited this humble site. You can visit the inside of the building at this post HERE. The west entrance to the building is reached by walking between the row of bungalows at 121 N. Avenue 50, in Highland Park. Occidental College Archives and Special Collections.

[image error]Above, the left (north) side of the former Charles M. Stimson Library appears in this scene where a bum throws a seemingly worthless jug of hard cider over the wall. Mary and fellow orphan Wesley Barry find the jug and innocently become inebriated. The matching left side of the library appears at left in the above photo. My sense is the towering wall was built for the production – it facilitates the story, and does not appear in vintage photos. The telephoto image left, displaying no wall, looks east at where the bum stood to the left of the corner library. Once part of the Occidental campus, the former Stimson Library occupied the north corner of N. Avenue 50 and N. Figueroa Street. Above USC Digital Library and left California State Library.

A final view showing the west entrance – the left side of the building. (C) 2019 Microsoft.

[image error]Not only did Mary film at Occidental before Chaplin, at the time she was living at 56 Fremont Place, across the street from 55 Fremont Place (above left), the mansion later appearing in The Kid when Edna Purviance abandons her infant in a millionaire’s limousine. Mary’s 56 Fremont Place home appears center above in The Red Kimono (1925) – a movie staged with incredible locations, and above right as Jean Harlow’s home in Bombshell (1933). Chaplin’s production records (right) for filming this Fremont Place scene in The Kid simply identifies the setting as “Pickford Street,” tying the location directly to Mary. Given their close association, one can’t help but imagine that Mary was instrumental in bringing these two crucial filming locations to Charlie’s attention.

Daddy-Long-Legs opens with establishing shots explaining some babies are nourished and cared for in beautiful surroundings, while others are born to misery and strife.

The beautiful surroundings pictured above are the conservatories at Eastlake Park east of downtown, renamed Lincoln Park in 1917. The site is now home to a Lincoln Park senior center.

Click to enlarge – the conservatories appear at back, center, in this vintage aerial view looking east at the park – N. Mission Road to the left and Valley Blvd. to the right. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

The next opening scene compares laboring orphans to prisoners in a chain gang. This brief shot from DDL reveals the true Los Angeles Orphanage once located at 917 S. Boyle Avenue near Hollenbeck Park. Notice the matching peaked side entrance and fire escape. USC Digital Library.

Later known as the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, this home for girls opened in 1890 and was in use until 1953. Long since demolished, Mary had also earlier staged scenes at this orphanage, above left, for Stella Maris in 1918. USC Digital Library.

Above, another true orphanage scene from Stella Maris. Mary stands by the arch beneath the side entrance stairs at the far lower left of the vintage image. It is fascinating (and frustrating) how often long lost iconic buildings are narrowly presented in silent film.

Now that we’ve covered DDL‘s deserted campus setting, its true orphanage cameos, and how Mary likely influenced Chaplin’s choice of two key scenes from The Kid, we’ll cover all of the MANY remaining locations, in Part Two, including two beautifully preserved mansions. Stay tuned.

Below, 121 N. Avenue 50, the former campus building, where Mary filmed at the west entrance shown here.

August 20, 2019

Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Schindler

Click to enlarge – north up Kings Road at Waring

Several years ago, following my introduction of Sherlock Jr. at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood, Los Angeles architect John Trautmann approached me to ask if I had noticed the famous Schindler house which appears in the background as Buster speeds along on his motorcycle. Located at 835. N. Kings Road, this home would come to be revered as one of the most influential structures of the 20th century.

[image error]

R.M Schindler (right), with architect Richard Neutra and Neutra’s wife Dionne and child in front of the house where the Neutras lived from 1925 until 1930.

R. M. Schindler was a progressive architect who emigrated from Vienna to work with Frank Lloyd Wright, first in Chicago in 1918, and then in Los Angeles in 1920. Setting off on his own, Schindler built the Kings Road House in 1922, and for the next three decades went on to experiment with shaping space and making liveable, iconoclastic houses and apartments, mostly throughout Los Angeles.

[image error]

835 N. Kings Road AD&A Museum – UC Santa Barbara

[image error]The Kings Road House is still standing with its grounds intact, although hemmed in now by modern apartment buildings. Organized on a “pinwheel” plan, in which vistas fly out from the core living spaces into the gardens beyond, it was built as a duplex, where each family could have its own indoor/outdoor realm. Concrete slabs were poured flat on the ground and tilted vertically to form the walls, in which vertical strips of glass serve as windows. The home’s rooftop sleeping porch is evident in the 1924 movie frame, but was yet to be constructed in the matching 1922 photo.

The Schindler House is now home to the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

July 18, 2019

The nearly last – Safety Last – joke

Three different Safety Last! rooftops for the closing scene, 548 S. Spring Street, 3rd and Spring, and 908 S. Broadway.

Surviving his heroic climb up a skyscraper during Safety Last!, Harold Lloyd falls into the arms of his loving fiancé Mildred Davis, waiting for him on the rooftop. As reported in another post, this satisfying conclusion was actually filmed from atop three different buildings all still standing in downtown, 548 S. Spring Street, the Washington Building at 3rd and Spring, and 908 S. Broadway. But as shown here, a fourth building was briefly involved in the final scene.

Harold’s roommate was supposed to make the climb (portrayed by real-life stunt climber Bill Strother), but Harold starts in his place when vengeful cop Noah Young chases Bill inside the building. At each floor of Harold’s climb Bill promises to switch places as soon as he can ditch the cop, a running gag.

[image error]

The 908 S. Broadway building owners recreate the closing scene – Harold losing his shoes and socks.

Once safe at last on the roof, the movie closes with Harold losing his shoes and socks to a sticky puddle of tar (at left), preceded by “drunken” character actor Earl Mohan helplessly entangled in a [image error]volleyball net (below). But the joke preceding Earl, the second to last joke of the entire movie, tops off the running gag by showing Noah still chasing after Bill on a faraway roof down below, with Bill still pleading to Harold in tiny intertitle print “I’ll be right back – Soon as I ditch the cop.”

[image error]

Noah Young chases Bill Strother along the roof of the former Mott Building.

This nearly last Safety Last joke was filmed looking down from the ten story Higgins Building, still standing at 2nd and Main, as Bill and Noah scramble north across rooftops from 141 S. Main to the Mott Building at 135 S. Main. Having studied the other Safety Last downtown locations, I knew this closing gag with Noah and Bill was not filmed near these other spots, and seemingly unsolvable, gave it no further thought.

Revisiting the scene years later, I realized from the light and angles that it was likely filmed looking north from the top of a fairly tall building. I also noticed trolley tracks in the street, and that one building had a finial (F) and a central, triangular parapet (P), while its neighbor had projecting twin bay windows, each sheltered by a curved roof (B) (see above). So I scrutinized vintage aerial photos for tall buildings near two story parapets and bay windows, and before long found the corner of 2nd and Main. Once identified, numerous ground level photos and vintage maps confirmed the location. This street level view above looks north up Main from 2nd towards City Hall. USC Digital Library.

Above (click to enlarge), this 1927 view is one of several vintage aerial views that helped to identify this closing scene. The arrow marks the camera’s point of view.

[image error]

Click to enlarge – another view from the Higgins Building looking down on where Noah chased Bill, with City Hall at back. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

Above, matching views up Main from Second, with City Hall at back. USC Digital Library and Palmer Conner collection Huntington Digital Library.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Below, a matching modern view north up Main Street from the Higgins Building on the left corner.

June 19, 2019

The Office – Film Noir – and Harold Lloyd

Click to enlarge. Harold Lloyd’s Speedy (1928) looking south down Witmer towards the Mayfair Hotel. Dwight, Erin, and Holly from The Office, shown below, stood by the stop sign on the right. (C) 2011 Google Inc.

What do the television show The Office, the 1950 film noir drama Edge of Doom, and Harold Lloyd’s final silent comedy Speedy (1928) have in common? They all filmed scenes looking southwest down Witmer Street towards the front of the Mayfair Hotel, at 1256 W. 7th Street, just west of downtown Los Angeles.

[image error]

The Office (2011) – Erin, Holly, and Dwight on Witmer Street beside the Prince Rupert Apartments. (C) 2011 Google Inc.

In a prior post I write all about the pivotal 2011 episode from The Office where characters Michael Scott and Holly Flax meet on the roof of the Mayfair Hotel, and declare their love for each other. Prior to that scene, Holly meets with characters Dwight Schrute and Erin Kemper on the street to devise a plan for locating Michael, who had wandered off dazed without his cell phone. The scene, shown above, was filmed at the NW corner of Witmer and Ingraham, beside what was once called the Prince Rupert Apartments. Notice the steep slope of the street.

[image error]

Click to enlarge. The prominent entrance to the Kensington Apartments, 668 Witmer Street, now lost, appears in Edge of Doom – left, and in Speedy – right. The Mayfair Hotel stands at the end in both shots. The Burton Arms Apartments, with the vertical white corner detail, still stands at 680 Witmer.

Harold Lloyd used the slope of Witmer Street to good advantage during an early scene in Speedy, where Harold recovers his idle taxi cab that had accidentally been towed away by a moving van. As Harold speaks with the truck driver, the taxi breaks loose and rolls down hill running over a traffic cop.

The unusual setting intrigued me, as it featured a downhill slope pointing towards a “T” intersection, capped by an uncommonly tall building, on which a trolley ran along the cross street. Although Speedy was filmed primarily on location in Manhattan, I also knew many taxi sequences were filmed on Flower Street in downtown Los Angeles. So I first checked the few trolley-line “T” intersections to be found along Bunker Hill, and in the downtown LA Historic Core, but nothing matched up. Since other scenes from this sequence were filmed in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, I checked nearby locales there as well to see if I could find this setting in New York, but it was another dead end.

[image error]

From Speedy – a cop about to be flattened by Harold’s taxi, and perhaps the only extant photo record showing the front of the lost Kensington Apartments.

My first break came when I noticed the Mayfair Hotel appeared at back during a scene in Edge of Doom (see above, left), as a troubled youth played by Farely Granger steps into the Kensington Apartments once located at 668 Witmer. With the Mayfair as a reference point, I now knew what the Kensington looked like, as it appeared on film, even though it is no longer standing. My second break was my realization (as discussed in my prior post about The Office) that in the 1920s there were tall buildings, such as the Mayfair, located just west of downtown Los Angeles, beyond the Historic Core. Then, while searching for a file, I somehow come upon the two above images from Edge of Doom and Speedy, and got a hunch to compare them side by side, making the match.

[image error]

The Burton Arms Apartments, 680 Witmer, as it appears in Speedy, 1928, and today. (C) 2011 Google Inc.

I find it fascinating how this one setting reappears over the decades. My sense is that “T” intersections are popular when filming for a number of reasons. First, it cuts down on traffic disruption, as through traffic can be more easily diverted. Next, it seems to be less visually distracting. Instead of the lines of the street stretching far off into the distance, drawing the viewer’s eye towards the vanishing point on the horizon, the cross street cuts across the view, creating a backdrop that contains the viewer’s eye.

[image error]

California Historical Society, Title Insurance and Trust Photo Collection, Department of Special Collections, University of Southern California. (c) 2012 Microsoft Corporation, Pictometry Bird’s Eye (c) 2010 Pictometry International Corp.

The aerial views above look to the north. The yellow arrow points SW down Witmer towards the Mayfair Hotel on 7th Street (yellow boxes), and the red ovals mark the corner stop sign where Dwight, Erin, and Holly stood (far above). The pin to the upper right shows the site of the lost Kensington Apartments, now a parking lot.

You can read about how Lloyd filmed Speedy all over Manhattan and Brooklyn, at Coney Island, and in Los Angeles, in my Harold Lloyd location book Silent Visions.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. The Office copyright (c) 2011 NBCUniversal Media, LLC. Edge of Doom Copyright 1950 The Samuel Goldwyn Company.

May 13, 2019

Chaplin, Keaton, and Lois Weber’s “Suspense” in Beverly Hills

[image error]The beautiful new Kino Lorber Blu-ray release Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers features dozens of early films created by women, many unseen for decades. One highlight is Lois Weber’s home invasion thriller Suspense (1913). As shown in a prior post, the film provides remarkable views of early Hollywood at the dawn of the movie industry, including below the Lasky-DeMille barn reflected in a side view mirror during the husband’s race home to rescue his threatened family. The “Barn” is now home to the Hollywood Heritage Museum, located on Highland Ave. across from the Hollywood Bowl. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

[image error]

The Lasky-DeMille barn at the corner of Selma and Vine – movie frame reversed for comparison

Leaving early Hollywood behind, the climax of the 1913 film takes place in Beverly Hills, at landmark locations that are today completely unrecognizable.

During his frantic race home, the husband hits a tramp pausing in the middle of an isolated dirt road to light a cigarette. Remarkably, this rural view looks west along Sunset Blvd. in eastern Beverly Hills, where Sunset bends left, south at Doheny Road. The matching tree, and bend in the road, appear in this vintage aerial view. LAPL.

Looking west, moments before the tramp is knocked over by the car. The box marks the same orderly rows of trees in both images, perhaps this was part of the Beverly Hills Nursery, see more below.

A 1922 view north, showing Sunset bending left, south at the “Y” intersection with Doheny Road. The perpendicular road to the right is Doheny Drive. The circle and box mark the same tree, and rows of trees, in the two frames above. LAPL.

Then and now, matching views where Sunset bends left, south, at Doheny Road.

Later during the race home the husband passes a billboard (above) that seems to say “Beverly Hills Nursery,” which once operated along Sunset Blvd. [image error]

This scene looking west, as the husband races along Sunset further east of Doheny Drive, appears to show in the distance the trio of domes (see below) spanning the entrance to the recently opened, and then completely isolated, Beverly Hills Hotel.

[image error]Above, the once remote Beverly Hills Hotel – USC Digital Library. The hotel appears prominently during Lois Weber’s Lost By A Hair (1914, see below), also part of the Pioneers Blu-ray set. As explained in my book Silent Traces, Charlie Chaplin would later film scenes from The Idle Class (1921, right) at the hotel, including this view of the hotel from what is now Will Rogers Memorial Park across the street.

Above, several 1914 scenes at the Beverly Hills Hotel from Lois Weber’s Lost By A Hair.

Looking north at Sunset Blvd. running from the Beverly Hills Hotel (left oval) to the Doheny Road corner (right oval), with the Beverly Hills Nursery possibly appearing mid-way in between. Santa Monica Blvd. runs diagonally from the lower left to upper right, while the former Beverly Hills Speedway race track stands in the foreground, sheltered from Wilshire Blvd. (running left-right above) by a row of trees. LAPL.

Above left, looking east down Doheny Road, towards where Sunset Blvd. bends to the right (south), as the police race towards the husband’s car (star). The view to the right looks west along Doheny, the star suggests where the husband’s car was parked.

We now throw a little Buster into the mix. This newly discovered footage from Keaton’s The Blacksmith (1922) was filmed nine years later, with a matching view east down Doheny Road (now paved) towards the Sunset Blvd. bend. The blue oval marks both sides of the entrance gate leading to “La Collina,” the Benjamin Meyers estate. You can read a detailed account of the estate HERE.

Contrast enhanced, the view from Suspense of the police racing north from Doheny Road towards the family home (left), and a matching view south from Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms (1918), both show tree-lined Doheny Drive leading at an angle south towards the left-right dark windbreak of trees along Wilshire Blvd. Doheny’s receding angle in each shot tells us Shoulder Arms was filmed further east, closer to Doheny Drive, than Suspense.

[image error]Looking north in 1922 reveals the gate to La Collina (blue), the likely site of the family home in Suspense (yellow), and the site where Charlie fooled the German soldiers disguised as a tree in Shoulder Arms (red), relative to perpendicular Doheny Drive to the right. You can read more about Chaplin filming here in my book Silent Traces.

Assuming this scene of the husband running towards the home was filmed where the other scenes were filmed on Doheny Road, then the house (yellow oval) appearing at back is likely the house (yellow oval) in the aerial view below.

[image error]Above – click to enlarge – this wider view looking north reveals the gate to La Collina (blue), the likely family home in Suspense (yellow), and the site where Charlie fooled the German soldiers disguised as a tree in Shoulder Arms (red). Nearby, the corner of Cynthia Street and Hammond Street (orange) marks the likely spot of another new scene from Keaton’s The Blacksmith, when Big Joe Roberts chases Buster past a street sign that seems to say “HAMMOND.” The view seems to be looking west down Cynthia from Hammond towards Doheny Drive, and is close to Buster’s scene beside La Collina (blue), below. I have several prior posts about the “new” scenes from The Blacksmith, read more HERE.

The gate to La Collina, looking east with Buster, and looking north in this 1922 view.

Another wide 1922 view showing the La Collina gate (blue), the likely site of the Suspense house – now removed (yellow), and the field where Chaplin disguised himself as a tree in Shoulder Arms (red). HollywoodPhotographs.com.

A final view – Buster, Lois Weber, and Chaplin all filmed near Doheny Road in east Beverly Hills, while it was undeveloped.

Matching views of the La Collina estate gate today.

Kino Lorber Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers. Check out Mary Mallory’s recent post about Lois Weber HERE.

Looking west at Sunset and Doheny Road.