Deborah Swift's Blog, page 46

January 18, 2012

Bringing your inner artist to heel - the long haul

Last week I read a great article in the Guardian called "unleash your inner artist" in which well-respected artists from different disciplines told the reader what inspired them. Each had ideas for setting the right conditions, and they varied from "Find a studio with more than one window" to "go on a journey with someone who is as different from you as chalk from cheese".

Last week I read a great article in the Guardian called "unleash your inner artist" in which well-respected artists from different disciplines told the reader what inspired them. Each had ideas for setting the right conditions, and they varied from "Find a studio with more than one window" to "go on a journey with someone who is as different from you as chalk from cheese".As a writer I have no trouble at all finding inspiration. I could start twenty books tomorrow. But the question is, could I sustain them? Never mind unleashing the inner artist, how do I bring it to heel?

For novelists, most of their work of their first draft happens in the middle of the book. For me the pattern looks a little like this:

Inspiration! (The beginning! I write feverishly.)

Hard graft,

H a r d G r a f t,

H a r d G r a f t,

H a r d G r a f t,

H a r d G r a f t

Aha! The End is in sight.

The End - breathes a sigh of relief.

So a lot of the trick of it is about keeping inspired through the long middle. The characters or subject must have viability for the long haul, and be fascinating enough to sustain my interest over the eighteen months it takes me to research and write the book.

One of the best quotes in the Guardian article was from Guy Garvey, singer/guitarist with Elbow, who quoted in turn some advice he'd been given by songwriter Mano McLaughlin.

"The song is all, he said. Don't worry about what the music sounds like; you have a responsibility to the song. I found that really inspiring: it reminded me not to worry about whether a song sounds cool or fits with everything we've done before - but just to let the song be what it is."

When I start out I have an idea of what the book will be.As I approach the middle I realise that the book is moving away from my vision of it. I try to bring it back. It persists in going its own way. Much of the hard graft in the middle of the book is about the battle between my control of the story and my imagination which wants to take a looser journey.Somewhere near the end of the hard graft phase I realise I have to "let the song be what it is" and allow the story that wants to be told to have free rein. Just about then, I glimpse the end.

Subsequent drafts are about letting go of previous rigid ideas that I had about what my book might be, and who I might be as a writer. I have had to let go of ideas that I might be a) as brillliant and respected as Hilary Mantel b) as popular and best-selling as Dan Brown c) about to be tipped as the next TV book club read, or d) the ground-breaking quirky new voice of the 21st century.

You might have to do the same. Maybe you thought it was literary fiction, until you found you had written a fast-moving convoluted thriller with a crazed psychopath. Maybe you thought you would like to write a romance, until you found it impossible to force those love scenes and ended up with a murder instead.Maybe you became so interested in the motivations of your central couple that the plot never happened and it became a meditation instead and you found you had written a literary novella.

I write historical fiction so here are my top tips for inspiring myself in the long haul.

Surprise, surprise, they all involve leaving the computer and going out, and none of them are hard-line research. They are what I call "dabbling."

Browse your subject in a second-hand bookshop.Don't rush, allow lots of time for diversions.

Wander round a place your character might have lived.

Look up his/her name on Ancestry.com and find out what his/her namesakes did

Go horse-riding. (In my books most people travel by horse)

Go to an Antique shop, auction or museum and handle objects from the period.

Find a spot to daydream about your book and make a point of allowing time for the mind to drift.

Let the song be what it is.

Published on January 18, 2012 02:53

January 2, 2012

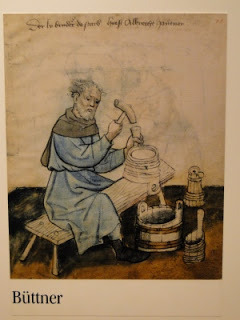

Three old trades - trunk-maker, wheelwright and hawker

Whilst researching The Gilded Lily, and London low-life of the 17th century, I was often impressed by how labour-intensive simple manufacturing was, before the industrial revolution, and also how ideas of ethical ways of making a living have shifted over the centuries. I thought I'd share some of the trades that are now almost lost to us in England.

The Trunk-Maker

A trunk-maker made trunks, chests, portmanteaux and cases for holding knifes or weaponry. He needed to be skilled in woodworking, metalwork and leatherwork in order to carry out his craft. So that although it was not highly regarded, he must have had to master a number of different skills.The wood needed to be shaped in the same way a barrel-maker made barrels, and then the structure covered with horse or sealskin with the hair left on, or hide tanned in the tannery. To stretch the leather over the wooden frame it was first boiled and pummelled with a mallet to soften it. Once it was stretched over, metal bands secured the whole thing in place. The bands were heated in the fire and hammered and nailed on. Travelling trunks had rings to strap or chain them before or behind the carriage. Portmanteaux and buckets were made solely of leather. The Portmanteaux carried linen clothing or hats, gloves and stockings, and could be shaped to sit over the horses back or attach to the saddle. Buckets for watering horses, or carrying other liquids were also stitched together by hand and then sealed with rabbit-skin glue and the seams greased to make them watertight.

A trunk-maker made trunks, chests, portmanteaux and cases for holding knifes or weaponry. He needed to be skilled in woodworking, metalwork and leatherwork in order to carry out his craft. So that although it was not highly regarded, he must have had to master a number of different skills.The wood needed to be shaped in the same way a barrel-maker made barrels, and then the structure covered with horse or sealskin with the hair left on, or hide tanned in the tannery. To stretch the leather over the wooden frame it was first boiled and pummelled with a mallet to soften it. Once it was stretched over, metal bands secured the whole thing in place. The bands were heated in the fire and hammered and nailed on. Travelling trunks had rings to strap or chain them before or behind the carriage. Portmanteaux and buckets were made solely of leather. The Portmanteaux carried linen clothing or hats, gloves and stockings, and could be shaped to sit over the horses back or attach to the saddle. Buckets for watering horses, or carrying other liquids were also stitched together by hand and then sealed with rabbit-skin glue and the seams greased to make them watertight.The Wheelwright

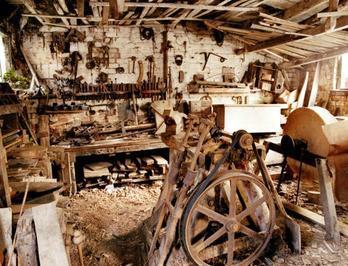

The wheelwright made wheels for road-waggons, carriages and carts.This is why the name "Wheeler" was quite common. I used the name Wheeler in The Lady's Slipper for one of my characters who I felt 'turned' from his original ideals. When making a wheel, it consisted of several parts.There was the nave or centrepiece, a circular wooden boss, and the spokes which were inserted into the nave, and also into the fellies or outside rim of the wheel. An iron tyre was fitted to the outside edge whilst red hot so that it moulded well, and also so that it burnt a small depression into the wood.This made it lay flat with the wood and roll easily.Considerable strength was required to bend the wood to make the fellies, and for the stretching of the iron band around the rim. Picture and more information about wheelwrights from

The wheelwright made wheels for road-waggons, carriages and carts.This is why the name "Wheeler" was quite common. I used the name Wheeler in The Lady's Slipper for one of my characters who I felt 'turned' from his original ideals. When making a wheel, it consisted of several parts.There was the nave or centrepiece, a circular wooden boss, and the spokes which were inserted into the nave, and also into the fellies or outside rim of the wheel. An iron tyre was fitted to the outside edge whilst red hot so that it moulded well, and also so that it burnt a small depression into the wood.This made it lay flat with the wood and roll easily.Considerable strength was required to bend the wood to make the fellies, and for the stretching of the iron band around the rim. Picture and more information about wheelwrights fromhttp://apetcher2.blogspot.com/2011/03/life-in-year-3rd-february-worshipful.html

The Hawker

A street seller of birds called himself a "hawker" from which we get the name for any person who travels door to door selling his wares.There is evidence that goldfinches were caught just outside London at Chalk Farm (then an actual farm rather than a Tube station!) and also at Finchley. Goldfinches were favoured because they looked pretty and lived the longest of caged birds - about fifteen or sixteen years, and were therefore better value than the average bird which survived three to nine years in captivity.Birds were also sold in bird shops, where as many as five hundred birds could be displayed. The hawkers skill was to catch the birds by means of a bird net fastened to the ground by stars - iron pins - and open at one end. A caged call-bird was put in the middle of the net. Hours went into the training of this decoy.The bird was trained to sing loudly to attract other birds, and when sufficient birds had congregated under the net the catcher pulled a line and the net fell.Birds were caught and sold for their song especially in London, where bird-song was prized. Linnets were very popular, but catching them was cold work as it could only be done in winter. Thrushes nests were plundered for their eggs, and the fledgelings were hand-reared in country cottages specifically for sale to the hawkers who would then sell them on at a profit.

A street seller of birds called himself a "hawker" from which we get the name for any person who travels door to door selling his wares.There is evidence that goldfinches were caught just outside London at Chalk Farm (then an actual farm rather than a Tube station!) and also at Finchley. Goldfinches were favoured because they looked pretty and lived the longest of caged birds - about fifteen or sixteen years, and were therefore better value than the average bird which survived three to nine years in captivity.Birds were also sold in bird shops, where as many as five hundred birds could be displayed. The hawkers skill was to catch the birds by means of a bird net fastened to the ground by stars - iron pins - and open at one end. A caged call-bird was put in the middle of the net. Hours went into the training of this decoy.The bird was trained to sing loudly to attract other birds, and when sufficient birds had congregated under the net the catcher pulled a line and the net fell.Birds were caught and sold for their song especially in London, where bird-song was prized. Linnets were very popular, but catching them was cold work as it could only be done in winter. Thrushes nests were plundered for their eggs, and the fledgelings were hand-reared in country cottages specifically for sale to the hawkers who would then sell them on at a profit. Birds and cage images from http://www.christmasballs.com and http://allaboutbirds.com

Birds and cage images from http://www.christmasballs.com and http://allaboutbirds.com

Published on January 02, 2012 10:45

December 18, 2011

Writing an Icon - an unusual art

I was reading in our free Parish Magazine that one of the nuns from our local monastery has been commissioned to write an icon for the local church. Of course it is a painting, but the terminology for producing a religious icon is to "write" it. I wondered why the word "writing" was used, so I did a little investigation.

An icon (from the Greek eikon - an image) is like a picture, but is not supposed to be an actual representation of the person, more like a window into our understanding of the qualities that the saint or holy person represents, and a window into our own soul and relationship with God. An icon can be compared to a carefully constructed poem. Every element, like a word in a poem, fits very concisely and precisely to add to the overall meaning and harmony of the whole.

Each icon is supposed to be unique and written with a prayerful attitude, requiring many hours of painstaking work, including contemplating the symbolism of that particular saint.

Each icon is supposed to be unique and written with a prayerful attitude, requiring many hours of painstaking work, including contemplating the symbolism of that particular saint.

"It's very important to be at peace with yourself and with the world around you. Writing an icon is a form of prayer. Each brushstroke is like a form of meditation. You have to have that inner peace. Otherwise, you can't do it." Maria Leontovitsh Manley, icon painter.

Not all icons are portraits, although this is the most common form. Above - a 12th Century Icon showing monks ascending a ladder to a welcoming Jesus. Note the devils trying to pull them off!

Nothing artificial is used in the production of an icon, which is usually painted on a wood panel that represents the Tree of Life or the Tree of Knowledge, and sometimes it is called an ark to recall the Ark of the Covenant.

Nothing artificial is used in the production of an icon, which is usually painted on a wood panel that represents the Tree of Life or the Tree of Knowledge, and sometimes it is called an ark to recall the Ark of the Covenant.

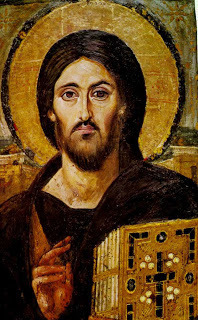

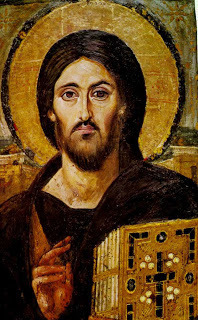

The board is covered with linen cloth which represents the shroud of Jesus and then the whole thing is painted with gesso and egg tempera in the required design. On the right is the earliest known icon of Christ from the 6th century.

Colour plays an important role in the design. Red represents divine life, and blue human life, whilst white is the pure essence of God, only used in resurrection and transmigration scenes. If you look at icons of Jesus and Mary, often Jesus wears red undergarments with a blue outer (God become human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red overgarment (human granted holy gift by God).

Often elaborate gilding is used, made from real 24 carat gold leaf. Gold, which does not tarnish is supposed to represent the Holy Spirit, or breath of life, because you have to breathe on the fine gold leaf to get it to settle into the glue before it can be burnished to a high shine.

There is a specific order to writing the icon: from the most general space (background) to the most specific (the face).

In an interview with iconographer Marek Csarnecki he says:

"There is a pragmatic reason for painting the face last. Although the face is the most important part of the icon, every detail in the icon is part of the transfigured reality, and has to receive the same level of focus and attention. Experience has shown me that if I start with the face, I obsessively work on it to the detriment of the rest of the icon, and it loses its overall harmony or wholeness and develops lopsided.

It's best to work from the outside to the inside, giving every aspect of the work its due. Painting the face first is like having dessert before dinner. You might lose your appetite for the rest of the meal."

I had no idea icons were so complex, or that they had such a rich history and tradition. I am looking forward to seeing what Sister Mary Stella writes for our local church. Apparently her icon will be of Saint Oswald and St Aidan (The patron saint of the local church and St Aidan has links to the North of England.) Pictures are from wikipedia commons.

An icon (from the Greek eikon - an image) is like a picture, but is not supposed to be an actual representation of the person, more like a window into our understanding of the qualities that the saint or holy person represents, and a window into our own soul and relationship with God. An icon can be compared to a carefully constructed poem. Every element, like a word in a poem, fits very concisely and precisely to add to the overall meaning and harmony of the whole.

Each icon is supposed to be unique and written with a prayerful attitude, requiring many hours of painstaking work, including contemplating the symbolism of that particular saint.

Each icon is supposed to be unique and written with a prayerful attitude, requiring many hours of painstaking work, including contemplating the symbolism of that particular saint."It's very important to be at peace with yourself and with the world around you. Writing an icon is a form of prayer. Each brushstroke is like a form of meditation. You have to have that inner peace. Otherwise, you can't do it." Maria Leontovitsh Manley, icon painter.

Not all icons are portraits, although this is the most common form. Above - a 12th Century Icon showing monks ascending a ladder to a welcoming Jesus. Note the devils trying to pull them off!

Nothing artificial is used in the production of an icon, which is usually painted on a wood panel that represents the Tree of Life or the Tree of Knowledge, and sometimes it is called an ark to recall the Ark of the Covenant.

Nothing artificial is used in the production of an icon, which is usually painted on a wood panel that represents the Tree of Life or the Tree of Knowledge, and sometimes it is called an ark to recall the Ark of the Covenant.The board is covered with linen cloth which represents the shroud of Jesus and then the whole thing is painted with gesso and egg tempera in the required design. On the right is the earliest known icon of Christ from the 6th century.

Colour plays an important role in the design. Red represents divine life, and blue human life, whilst white is the pure essence of God, only used in resurrection and transmigration scenes. If you look at icons of Jesus and Mary, often Jesus wears red undergarments with a blue outer (God become human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red overgarment (human granted holy gift by God).

Often elaborate gilding is used, made from real 24 carat gold leaf. Gold, which does not tarnish is supposed to represent the Holy Spirit, or breath of life, because you have to breathe on the fine gold leaf to get it to settle into the glue before it can be burnished to a high shine.

There is a specific order to writing the icon: from the most general space (background) to the most specific (the face).

In an interview with iconographer Marek Csarnecki he says:

"There is a pragmatic reason for painting the face last. Although the face is the most important part of the icon, every detail in the icon is part of the transfigured reality, and has to receive the same level of focus and attention. Experience has shown me that if I start with the face, I obsessively work on it to the detriment of the rest of the icon, and it loses its overall harmony or wholeness and develops lopsided.

It's best to work from the outside to the inside, giving every aspect of the work its due. Painting the face first is like having dessert before dinner. You might lose your appetite for the rest of the meal."

I had no idea icons were so complex, or that they had such a rich history and tradition. I am looking forward to seeing what Sister Mary Stella writes for our local church. Apparently her icon will be of Saint Oswald and St Aidan (The patron saint of the local church and St Aidan has links to the North of England.) Pictures are from wikipedia commons.

Published on December 18, 2011 14:01

December 16, 2011

Unputdownable - The Courtesan's Lover by Gabrielle Kimm

The Courtesan's Lover is exactly the sort of book to keep you occupied over Christmas as you sip mulled wine before a cosy fire. In fact I would liken it to mulled wine - rich, deep and satisfying!

The Courtesan's Lover is exactly the sort of book to keep you occupied over Christmas as you sip mulled wine before a cosy fire. In fact I would liken it to mulled wine - rich, deep and satisfying!Set in a beautifully realised Renaissance Italy, it tells the story of Francesca Felizzi, a wealthy courtesan, who decides to 'go straight.' The first section of the book shows us her life as a courtesan - the glamour and the potential danger are neatly interwoven. For the book to work this part has to be believable and the author spends some time setting this up, so we understand just what a courtesan's life would have been like, right down to how a citrus fruit is used as a contraceptive device!.The setting of Napoli is impeccably researched; the nitty-gritty of Francesca's business is described frankly, but there is nothing here that would shock the average reader.

Once Francesca falls in love, the rest of the book is concerned with how her former clients interact with each other, and how each past encounter now poses a danger to the one true relationship in her life. The reader is kept on tenterhooks wondering which of her lovers will betray her. There are plenty of colourful characters, not least her servant Modesto, a eunuch, whose plight is both touching and sad. There can be few books that examine the tragedy of these young boys whose voices were preserved by the worst kind of intervention.

There is plenty of danger to add spice to this romance.

We fear for Francesca's life when she entertains the sadistic Michele - the client from hell, and fear for her daughters at the hands of the irrational Carlo, her lover's son. Gabrielle Kimm racks up the tension and the pace so it builds nicely to its conclusion.

The Courtesan's Lover is a well-written pageturner, a good old fashioned story with action, romance and a sumptuous setting. Very highly recommended.

Published on December 16, 2011 11:03

December 8, 2011

The UK Historical Writers Association Dinner

How much noise do fifty writers make when they are gathered together for dinner? The answer is - it's deafening! It could be that we are desperate to speak after staring at our computer screens and notepads in our solitary imaginary worlds, or it could be that historical fiction writers are just loud, but lip-reading skills would have certainly been a bonus!

On the way in to The Westbourne I got chatting with Cassandra Clark, who then introduced me to more people. It was hard to read everyone's name-badges, without missing chunks of the conversation, but over drinks we spoke of agents good and bad, of promotional postcards, and booksignings, and the fact that some plots never seem to go where we want them to go. In short, lovely to share experiences and know that others are travelling the same path.

When we finally say down to dinner and people were eating, the noise abated enough for us to have a proper conversation. I was seated at one of the smaller tables along with what I shall call the "Roman cohort". I found out some interesting facts about roman armour from Lindsay Powell - that it was chain mail, or individually made, not always the plate armour we see in films, and as an added bonus he filled us in on not-so-ancient American politics.

Also on my table was Ben Kane, who not only writes best-sellers but seems to be a great organiser,as it was he who had master-minded the evening. Ruth Downie was opposite me, all the way from Devon, and it was interesting to hear that she has the same trouble with slaves in her books as I have with servants and chaperones. We have to get rid of them if we want a scene to be between just two people, and then bring them back whenever the character needs to go anywhere.

Also on my table was Ben Kane, who not only writes best-sellers but seems to be a great organiser,as it was he who had master-minded the evening. Ruth Downie was opposite me, all the way from Devon, and it was interesting to hear that she has the same trouble with slaves in her books as I have with servants and chaperones. We have to get rid of them if we want a scene to be between just two people, and then bring them back whenever the character needs to go anywhere.

Gabrielle Kimm was next to me and we already know each other from a long while back when we were both short-listed for the same prize. (Neither of us won, but it made us friends.) I had her latest book with me to persuade her to sign it for me, and on the way home I finished reading it, so a review is coming soon.

What was going on at the other tables I have no idea, but looking over my shoulder it seemed everyone was engrossed in conversation with somebody. Thanks to Stella for her warm welcome. It was lovely to meet all those writers. And thanks to everyone I met for a great evening. At the top are the books of the folks I met, if you are looking for a Christmas present for someone, why not choose one of these....

Find out more about the Association:http://www.thehwa.co.uk/

On the way in to The Westbourne I got chatting with Cassandra Clark, who then introduced me to more people. It was hard to read everyone's name-badges, without missing chunks of the conversation, but over drinks we spoke of agents good and bad, of promotional postcards, and booksignings, and the fact that some plots never seem to go where we want them to go. In short, lovely to share experiences and know that others are travelling the same path.

When we finally say down to dinner and people were eating, the noise abated enough for us to have a proper conversation. I was seated at one of the smaller tables along with what I shall call the "Roman cohort". I found out some interesting facts about roman armour from Lindsay Powell - that it was chain mail, or individually made, not always the plate armour we see in films, and as an added bonus he filled us in on not-so-ancient American politics.

Also on my table was Ben Kane, who not only writes best-sellers but seems to be a great organiser,as it was he who had master-minded the evening. Ruth Downie was opposite me, all the way from Devon, and it was interesting to hear that she has the same trouble with slaves in her books as I have with servants and chaperones. We have to get rid of them if we want a scene to be between just two people, and then bring them back whenever the character needs to go anywhere.

Also on my table was Ben Kane, who not only writes best-sellers but seems to be a great organiser,as it was he who had master-minded the evening. Ruth Downie was opposite me, all the way from Devon, and it was interesting to hear that she has the same trouble with slaves in her books as I have with servants and chaperones. We have to get rid of them if we want a scene to be between just two people, and then bring them back whenever the character needs to go anywhere.Gabrielle Kimm was next to me and we already know each other from a long while back when we were both short-listed for the same prize. (Neither of us won, but it made us friends.) I had her latest book with me to persuade her to sign it for me, and on the way home I finished reading it, so a review is coming soon.

What was going on at the other tables I have no idea, but looking over my shoulder it seemed everyone was engrossed in conversation with somebody. Thanks to Stella for her warm welcome. It was lovely to meet all those writers. And thanks to everyone I met for a great evening. At the top are the books of the folks I met, if you are looking for a Christmas present for someone, why not choose one of these....

Find out more about the Association:http://www.thehwa.co.uk/

Published on December 08, 2011 06:36

November 30, 2011

The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey

For the time of year you can't do better than this stunning debut by Eowyn Ivey. The Snow Child is a beautifully written novel of longing and loss, and the battle of human beings to make their place at the edge of habitable nature.

In the wilds of Alaska Jack and Mabel build a snowman - a girl - on the night of the first snowfall. After this a little girl mysteriously enters their life. From the book I gather the Russian myth of the snow girl was collected by Arthur Ransome (of Swallows and Amazon's fame), and this myth has been skilfully interleaved with the narrative in Ivey's book.

The tale borders on the mythic and shifts between what is real and what is imaginary, and this is what gives it its uncanny power. The snow child herself is like nature, not easily tamed, and for most of the book we are not sure whether they are taming the girl or nature herself. For example Jack and Mabel's speech is in speech marks, but the snow girl's is not. This gives a sense in which we almost imagine we are hearing her voice, that it half-blends with the background. Masterful.

The book portrays the realities of survival, the killing of animals and the sheer hard work with an unflinching eye as Jack and Mabel eke out an existence where neighbours can mean the difference between survival and failure. I enjoyed Esther and George, the rumbustious neighbours, and the portrayal of Garrett, the boy who turns into a man before our eyes.

For me the star of the book is the landscape, reflected beautifully in the bare-boned prose.

Very highly recommended.

Published on November 30, 2011 02:11

November 17, 2011

The Creation of a Master-piece - Guilds in England

From the 14th century right up until the 18th century in England, no master-craftsman could set up in a particular craft unless he became a member of its Guild.

From the 14th century right up until the 18th century in England, no master-craftsman could set up in a particular craft unless he became a member of its Guild. So what were these Guilds that had such a stranglehold on craftsmanship and production?

The Guilds were controlled by a self-elected oligarchy, or confraternity of craftsmen, a system greased by bribery and favouritism.

Above, a bootmaker from Northampton shows his wares.

Guild Laws restricted a man to the manufacture of only one article, for example weavers were not allowed to dye their cloth, shoemakers were not permitted to mend shoes and bowyers could not make arrows for their bows, only the fletchers could do that. This was supposedly to protect each craftsman's job, but in practice led to much dispute and difficulty.

If you became a member of a Guild you would have to make your goods from specified materials, employ a specified number of apprentices, and sell at the Guild's fixed prices. If you failed to do this, or produced shoddy goods or work not approved by the Guild you would face penalties such as a fine, punishment in the pillory or imprisonment. Each Guild had a Court, and cases not satisfied in the Court would go before the Mayor who would arbitrate.

Only freemen of a particular town could join the Guild for their craft. Even if you had been a Guild member in another town, you still had to serve 5 years bound to a recognised master in the new town before you could prove yourself by making your "master-piece" and finally being admitted to join.

No one was allowed to sell their goods by candlelight, in case of passing off faulty workmanship under cover of darkness, and no work could be done after eight o'clock Saturday night until Monday morning, to respect the Sabbath.

Guilds were social as well as business institutions, and concerned themselves with the welfare of their workers and founded schools and alms-houses, even occasionally in some crafts supplying dowries for poorer women workers. Each Guild had its own Chaplain to conduct the services, and its own patron saint - St Anthony for grocers, St Patrick for saddlers, St Clement for tanners, St Stephen for weavers, and so forth.

Crafts were highly specialised, there were Guilds of longbow-string makers, salters, horners, patten makers, quilters and pin makers. Above you can see the Guild of Painters, of 1695. As you can see they are all dressed alike. Each Guild had its own costume, with variations for the different ranks. Apprentices wore blue cloaks in the winter and blue gowns in the summer. Nobody was allowed to wear cloaks below calf-length until they reached old age.Many of England's finest buildings are the Guild Halls quite a few of which survive. The one pictured is Leicester's Guild Hall, a fine Elizabethan example.

"a haberdasher and a carpenter,A webber, dyer and a papicerWere with us eke, clothed in a liveryOf a solemn and great fraternity. Full fresh and new their gear apyked was,Their knives were ychaped not with brass,but all with silver wrought full clean and weel.Their girdles and their puches every deal.Well seemed each of them a fair burgessTo sitten in a Guild Hall on a dais"Chaucer

Published on November 17, 2011 02:07

November 15, 2011

A gentle undemanding stroll through an English Village

This small undemanding guide to the English Village would make an ideal gift for a townie or visitor to England just before they drive off into our rural byways. Divided neatly into 10 chapters, each section conveys a sense of the traditions and formation of the features of a typical english village. The Village green, the pub, the church and the big house are all here. I particularly enjoyed the section on the big house - the legacy of manor houses has been frequently undervalued and Wainwright makes us understand what they contributed and underlines the appeal of such series as Downton Abbey or Cranford.

This small undemanding guide to the English Village would make an ideal gift for a townie or visitor to England just before they drive off into our rural byways. Divided neatly into 10 chapters, each section conveys a sense of the traditions and formation of the features of a typical english village. The Village green, the pub, the church and the big house are all here. I particularly enjoyed the section on the big house - the legacy of manor houses has been frequently undervalued and Wainwright makes us understand what they contributed and underlines the appeal of such series as Downton Abbey or Cranford.Simplistic black and white woodcuts serve as illustrations - colour pictures would have helped bring the text to life (my only quibble). As will be apparent from its size, this is more of a general guide than an in-depth examination, but it packs a lot of information into a small space.

And talking of houses - I highly recommend Simon Jenkins paperback book England's Thousand Best Houses, a brick-shaped county by county guide to the big houses referred to in Wainwright's book. Jenkins is chairman of the National Trust and gives succint descriptions of each house's history, quirks and claim to fame.

Each house warrants at the most a couple of pages in this paperback, but again it is surprising just how much information can be compressed into such a small space. For historical fiction writers, this is your best guide to where to see period houses. All the houses in the book are open to the public and helpfully graded with stars to denote their importance. Oddly enough, I have often found the houses rated 1 star such as Lancaster's Cottage Museum to be more interesting than those rated with 5 stars, an accolade reserved for edifices such as Windsor Castle.

Published on November 15, 2011 07:47

November 13, 2011

The Darling Strumpet by Gillian Bagwell

Only another historical fiction writer could appreciate the amount of research that has gone into Gillian Bagwell's novel "The Darling Strumpet". And as I have researched a book in the same period I hope I could have spotted holes in the historical background had there been any - but the detail was impeccable, no holes here!The way the historical fact blended with the characterisation and story was excellent.

I am fascinated by Nell Gwynn and her journey from rags to riches via the English Theatre. I used to lecture students on a theatre course about the Restoration, so of course I could not wait to read this novel. Those interested in this aspect could do worse than visit the current National Portrait Gallery's exhibition of actresses - the scale of the portraits brings you quite literally face-to-face with Nell Gwynn. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jun/07/national-portrait-gallery-first-actresses

But, back to the book -

Nell begins this novel poor and hungry, but soon realises she has a commodity she can sell. Her first encounter does not go entirely to plan, but we all know that she will end up in the bed of a King. Gillian Bagwell is skilful at keeping the reader's interest although of course we all know what will happen to Nell. In an age where violence was the norm, it is no use being coy about sexual relationships, and these are dealt with frankly. Most of the explicit encounters are at the beginning of the book and they lend the book its necessary earthy tone. The whole point of Nell Gwynn was how she used her 'charms', after all.

Once Nell Gwynn is established as a royal mistress the book examines how she is still, as a woman - not to mention the King's whore, excluded from all the decisions and intrigue of life at court. In many ways Nell was better cut out for the role of aspiring courtesan than established mistress. Gillian Bagwell draws these contrasts nicely, and I admired the way she did not let the reader's interest flag.

The novel gives you the sights, sounds and smells of Restoration London and brought Nell's journey vividly to life.

Very highly recommended.

Published on November 13, 2011 08:46

November 10, 2011

The Jazz Age of the 17th Century

Under Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth, there had been little spending. No gambling on horses, no visits to the theatre, no music or dancing - even Christmas Day was banned. One of the broadsheets of the time lamented,

We are serious people now and full of cares,as melancholy as cats, as glum as hares.

But after ten years of gloom, how did England celebrate? Well, with an intensification of all the old delights. Fashion was at its most outrageous, with new styles brought from France and Spain, in an outburst of feverish spending.

Charles II tried to bring in a standard costume for men at court, described by John Evelyn in his Diary of 1666 as "Eastern fashion of vest, changeing doublet, stiff collar, bands and cloake", but Pepy's wagered that it would be less than a year before the court was back into French frippery, and he was right.

Charles II tried to bring in a standard costume for men at court, described by John Evelyn in his Diary of 1666 as "Eastern fashion of vest, changeing doublet, stiff collar, bands and cloake", but Pepy's wagered that it would be less than a year before the court was back into French frippery, and he was right.The country was tired of restraint and wanted ostentation - the more extreme the fashion, the better. Clothes were adorned with ribbons and lace and plumes. Wigs came in, and the carrying of fancy-hilted dress swords.

Pastimes became not only frivolous but positively juvenile. A favourite indoor sport of the young townspeople was pillow and cushion fighting. Pepys reports:

"anon to supper; and then my Lord going away to write, the young gentlemen to flinging of cushions and other mad sports till towards twelve at night."

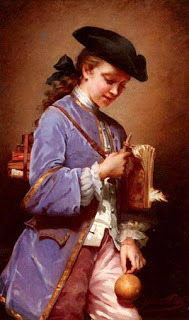

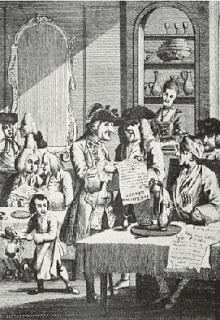

Another popular pastime was playing cup-and-ball - see all the ladies and gents playing it at the head of this page. Blind-man's buff was a fashionable indoor game, as was building houses of playing cards. The second Duke of Buckingham was apparently very skilled at this, and would spend hours erecting elaborate his elaborate "card palaces".(left 18th century painting of a boy with cup and ball)

Another popular pastime was playing cup-and-ball - see all the ladies and gents playing it at the head of this page. Blind-man's buff was a fashionable indoor game, as was building houses of playing cards. The second Duke of Buckingham was apparently very skilled at this, and would spend hours erecting elaborate his elaborate "card palaces".(left 18th century painting of a boy with cup and ball)Dancing was no longer stately as it had been before Puritan rule. Nobody wanted the dull old dances any more. New italian jigs and corantos were danced at a more lively tempo. It must have been the equivalent of the Jazz Age in the twenties after the staid waltzes of the Pre-war era.

And all at once three new beverages - tea, coffeee and chocolate, were imported within a few years of each other and at once became extremely sought after, despite their expense. Coffee houses became fashionable places for men to meet and discuss state affairs, so much so that the King became scared of what might be being said behind his back, and issued an order to ban them. But so numerous and popular had they become that enforcing the order was impossible and the King finally gave up the attempt.

And thank goodness, for we still use coffee shops as a place to meet and gossip with our friends, or to discuss the latest news.

Published on November 10, 2011 06:20