Deborah Swift's Blog, page 45

May 3, 2012

Why is my Kindle Library so unappealing?

Like many other bookaholics I have bought a Kindle and have quite a few books on there waiting to be read. They are historical fiction books that were offered free for a limited time, other books I thought at the time I could not wait to read, and books about my craft of writing. I intend to get around to reading them all, or I wouldn't have downloaded them.

So why haven't I?

The answer is, there is an equally large To-Be-Read pile sitting on my bookcase. These are paperback books. More often than not, if I want a book I will go to this pile, rather than the Kindle. This is because I am in fact browsing again for my choice of book, and in this browsing process of what to read next, the cover and the blurb makes a big impact on my choice all over again.

Seeing a typed list of which clothes to wear in the morning is not the same as looking at them hanging in the wardrobe.

So very often it is a book from the paperback pile that I will choose, and the Kindle books stay unread unless I am going on a long-haul flight. After all, most of my reading is done at home, and when I am packing to go on a short trip, my choosing is done at home.

This lack of appeal on the device makes no difference to the publishers - after all they have already made their sale. But it does make a difference to writers. If someone buys a paper book, there is a good chance it will be read - or recycled via a charity or thrift shop to someone who will read it. On the kindle, a book can get lost in a list for a long time, and as it takes up little space, may never be read.

This lack of appeal on the device makes no difference to the publishers - after all they have already made their sale. But it does make a difference to writers. If someone buys a paper book, there is a good chance it will be read - or recycled via a charity or thrift shop to someone who will read it. On the kindle, a book can get lost in a list for a long time, and as it takes up little space, may never be read.

The World Book Night Books I gave away

The World Book Night Books I gave away

When I gave out books for World Book Day, they were all physical books. A physical book jogs the memory - hey, I'm here! So I like to think many of them will be read, even though I gave them away free. I collected them from Arnside Library where a big part of the Library experience is browsing. I cannot imagine a library where I just read titles.

Arnside Library As a writer, I want to be read, rather than just stored on a machine, so it seems to be that the more sensory data there is with a book, the more likely it is to be read. I like to browse my books, so the sooner the Kindle can come up with this browsing function, complete with colour cover image and graphics, the better.

Arnside Library As a writer, I want to be read, rather than just stored on a machine, so it seems to be that the more sensory data there is with a book, the more likely it is to be read. I like to browse my books, so the sooner the Kindle can come up with this browsing function, complete with colour cover image and graphics, the better.

What do others think? Have you many books sitting unread on the Kindle?

So why haven't I?

The answer is, there is an equally large To-Be-Read pile sitting on my bookcase. These are paperback books. More often than not, if I want a book I will go to this pile, rather than the Kindle. This is because I am in fact browsing again for my choice of book, and in this browsing process of what to read next, the cover and the blurb makes a big impact on my choice all over again.

Seeing a typed list of which clothes to wear in the morning is not the same as looking at them hanging in the wardrobe.

So very often it is a book from the paperback pile that I will choose, and the Kindle books stay unread unless I am going on a long-haul flight. After all, most of my reading is done at home, and when I am packing to go on a short trip, my choosing is done at home.

This lack of appeal on the device makes no difference to the publishers - after all they have already made their sale. But it does make a difference to writers. If someone buys a paper book, there is a good chance it will be read - or recycled via a charity or thrift shop to someone who will read it. On the kindle, a book can get lost in a list for a long time, and as it takes up little space, may never be read.

This lack of appeal on the device makes no difference to the publishers - after all they have already made their sale. But it does make a difference to writers. If someone buys a paper book, there is a good chance it will be read - or recycled via a charity or thrift shop to someone who will read it. On the kindle, a book can get lost in a list for a long time, and as it takes up little space, may never be read. The World Book Night Books I gave away

The World Book Night Books I gave awayWhen I gave out books for World Book Day, they were all physical books. A physical book jogs the memory - hey, I'm here! So I like to think many of them will be read, even though I gave them away free. I collected them from Arnside Library where a big part of the Library experience is browsing. I cannot imagine a library where I just read titles.

Arnside Library As a writer, I want to be read, rather than just stored on a machine, so it seems to be that the more sensory data there is with a book, the more likely it is to be read. I like to browse my books, so the sooner the Kindle can come up with this browsing function, complete with colour cover image and graphics, the better.

Arnside Library As a writer, I want to be read, rather than just stored on a machine, so it seems to be that the more sensory data there is with a book, the more likely it is to be read. I like to browse my books, so the sooner the Kindle can come up with this browsing function, complete with colour cover image and graphics, the better.What do others think? Have you many books sitting unread on the Kindle?

Published on May 03, 2012 04:15

April 10, 2012

Time-slip historicals - twice as hard to write?

"The huge advantage, as a novelist writing in both the present and the past, is that you can use both to shine a light on the other."' Kate Mosse.

I've recently finished Mariana by Susanna Kearsley, a novel in which a woman travels back in time to the 17th century after she buys an old manor house. The house acts as a portal to another era. Susanna Kearsley had been highly recommended to me and this is the first of her books I have read. However - a mystery - it must be a reprint as it was first published in 1994. This explained to me why it had a slightly dated feel in the modern sections with nobody owning a mobile phone or spending hours on the internet. So my first thoughts on writing a time-slip novel is that the contrasting times work well if the modern-day part is up-to-date, and that perhaps time-slip novels may date more easily than simple historicals.

However, The Mathematics of Love by Emma Darwin combines two periods - the 1970's and the 19th century with ease. Both parts of the story will have required research in order to create what she calls "a unique space where serious writers can explore fundamental desires and fears, while revelling in the nearness and otherness of worlds that we know were here, but can' t quite see."

Parallel narratives can allow the writer to do just that - draw parallels and make links between two periods for the enrichment of the story.

The knack with time-slip novels is to keep both stories ticking over and to persuade the reader to give equal amounts of emotional investment to both parts of the plot. I am currently reading Kate Mosse's Sepulchre, and one of the ways she achieves this investment is simply by making the book long enough so that both aspects of the story are in effect a full-length novel. The modern story of the american, Meredith Martin, researching Claude Debussy is satisfyingly familiar with online research and all the trappings of modern life.One of the reasons I enjoy time-slip books is that after sections in our "familiar" world, the world of the past feels fresh again when we revisit it. A bit like clearing the palate between courses.The contrasting periods thus enrich the novel.

On her website, Kate Mosse says

On her website, Kate Mosse says

"Timeslip novels are complicated to write, though. It's not just a matter of remembering where characters are, what's happening to them, how they connect together, but also keeping the 'voices' of the different periods separate and distinct. The way I work with the material, therefore, is to write the entire 1981 – 1897 historic story line (in the case of Sepulchre, Léonie and Anatole's story), then write the whole of Meredith's story, to ensure that the voices, the timbre and the cadences of each section stay distinct. I then start to put the sections together, ten chapters in one time period, ten in the next and so on, until I have a second draft. Finally – and this can be heartbreaking to see all your work going into the virtual rubbish bin – I cut half of it to produce a third draft, which I then edit!"

Wow, that sounds like a very long daunting process, doesn't it?

On the fiction Forum, Emma Darwin, author of "The Mathematics of Love" says "you need to make an extra-compelling case for having two separate stories in the same book......

"It's also not easy to do well because you're asking the reader to do the literary equivalent of patting their head and rubbing their tummy, understanding each strand as a stand alone story, even though it's chopped into chunks, but also making the thematic and other links across between them.

There's also the risk that the reader is more compelled by one strand than the other... it's a dangerous game... Many responses to my novels are that the reader preferred one strand to the other: the risk is that they get so fed up with plodding on with the one they don't like, in order to get to the one they do, that they give up altogether. Others resent the wrench when changing, even if they like both stories, or find it disorienting. Many settle down in the end but it makes many find it slow going to start with - and no doubt some give up. I do know that some people just find it too much like hard work, and some don't ever get why they're both in there. On the other hand, others love it, and love the extra dimension it adds."

The issues when writing a time-slip novel seem to be the same as when writing any historical - not only do you need accuracy of research to build a credible world, but also the switch of points of view between characters needs to be carefully handled when they are changing in time.The whole mood and way of talking are different in changing centuries. Dialogue in 1970 is not the same as dialogue in 1870. The flow of the narrative is especially hard to achieve I would imagine.

I would recommend all these novels as good examples of the time-slip phenomenon.If you would like more suggestions, then have a look at the Woman and Home top 5.

http://www.womanandhome.com/articles/travelandentertainment/books/385161/5-best-time-slip-novels.html

Read an interview with Susanna Kearsley

Emma Darwin's excellent writing blog

Last word on the subject from Kate Mosse:

"I also believe, strongly, that the past casts a shadow over the present, sometimes for the good, sometimes less so. Human experience is a continuum and we are linked with those who have gone before us. What links us together is greater than what divides us – religion, context, period of history, nationality – and the human heart does not change so very much."

www.katemosse.com

I've recently finished Mariana by Susanna Kearsley, a novel in which a woman travels back in time to the 17th century after she buys an old manor house. The house acts as a portal to another era. Susanna Kearsley had been highly recommended to me and this is the first of her books I have read. However - a mystery - it must be a reprint as it was first published in 1994. This explained to me why it had a slightly dated feel in the modern sections with nobody owning a mobile phone or spending hours on the internet. So my first thoughts on writing a time-slip novel is that the contrasting times work well if the modern-day part is up-to-date, and that perhaps time-slip novels may date more easily than simple historicals.

However, The Mathematics of Love by Emma Darwin combines two periods - the 1970's and the 19th century with ease. Both parts of the story will have required research in order to create what she calls "a unique space where serious writers can explore fundamental desires and fears, while revelling in the nearness and otherness of worlds that we know were here, but can' t quite see."

Parallel narratives can allow the writer to do just that - draw parallels and make links between two periods for the enrichment of the story.

The knack with time-slip novels is to keep both stories ticking over and to persuade the reader to give equal amounts of emotional investment to both parts of the plot. I am currently reading Kate Mosse's Sepulchre, and one of the ways she achieves this investment is simply by making the book long enough so that both aspects of the story are in effect a full-length novel. The modern story of the american, Meredith Martin, researching Claude Debussy is satisfyingly familiar with online research and all the trappings of modern life.One of the reasons I enjoy time-slip books is that after sections in our "familiar" world, the world of the past feels fresh again when we revisit it. A bit like clearing the palate between courses.The contrasting periods thus enrich the novel.

On her website, Kate Mosse says

On her website, Kate Mosse says"Timeslip novels are complicated to write, though. It's not just a matter of remembering where characters are, what's happening to them, how they connect together, but also keeping the 'voices' of the different periods separate and distinct. The way I work with the material, therefore, is to write the entire 1981 – 1897 historic story line (in the case of Sepulchre, Léonie and Anatole's story), then write the whole of Meredith's story, to ensure that the voices, the timbre and the cadences of each section stay distinct. I then start to put the sections together, ten chapters in one time period, ten in the next and so on, until I have a second draft. Finally – and this can be heartbreaking to see all your work going into the virtual rubbish bin – I cut half of it to produce a third draft, which I then edit!"

Wow, that sounds like a very long daunting process, doesn't it?

On the fiction Forum, Emma Darwin, author of "The Mathematics of Love" says "you need to make an extra-compelling case for having two separate stories in the same book......

"It's also not easy to do well because you're asking the reader to do the literary equivalent of patting their head and rubbing their tummy, understanding each strand as a stand alone story, even though it's chopped into chunks, but also making the thematic and other links across between them.

There's also the risk that the reader is more compelled by one strand than the other... it's a dangerous game... Many responses to my novels are that the reader preferred one strand to the other: the risk is that they get so fed up with plodding on with the one they don't like, in order to get to the one they do, that they give up altogether. Others resent the wrench when changing, even if they like both stories, or find it disorienting. Many settle down in the end but it makes many find it slow going to start with - and no doubt some give up. I do know that some people just find it too much like hard work, and some don't ever get why they're both in there. On the other hand, others love it, and love the extra dimension it adds."

The issues when writing a time-slip novel seem to be the same as when writing any historical - not only do you need accuracy of research to build a credible world, but also the switch of points of view between characters needs to be carefully handled when they are changing in time.The whole mood and way of talking are different in changing centuries. Dialogue in 1970 is not the same as dialogue in 1870. The flow of the narrative is especially hard to achieve I would imagine.

I would recommend all these novels as good examples of the time-slip phenomenon.If you would like more suggestions, then have a look at the Woman and Home top 5.

http://www.womanandhome.com/articles/travelandentertainment/books/385161/5-best-time-slip-novels.html

Read an interview with Susanna Kearsley

Emma Darwin's excellent writing blog

Last word on the subject from Kate Mosse:

"I also believe, strongly, that the past casts a shadow over the present, sometimes for the good, sometimes less so. Human experience is a continuum and we are linked with those who have gone before us. What links us together is greater than what divides us – religion, context, period of history, nationality – and the human heart does not change so very much."

www.katemosse.com

Published on April 10, 2012 04:40

April 6, 2012

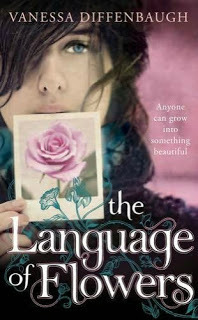

The Language of Flowers - Vanessa Diffenbaugh

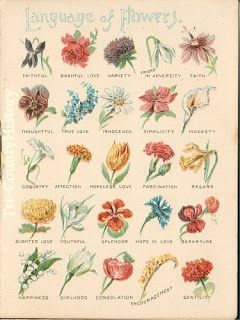

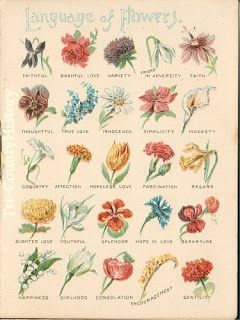

Common in the 19th century, the idea that flowers had symbolic meanings led people to convey their emotions through the gifts of the flowers they gave one another. Known as the art of "floriography", these symbolic bouquets became popular, and the posies were known as "tussie-mussies" in Victorian times. Today you can find more about the meanings of individual flowers from The Gardener

This Image comes from Joyce Tice's website

This Image comes from Joyce Tice's website

The Language of Flowers tells the story of Victoria, a homeless eighteen year old and her passion for the meanings of flowers.

The Language of Flowers tells the story of Victoria, a homeless eighteen year old and her passion for the meanings of flowers.

Victoria has been brought up in foster care, and the only adult with whom she had a meaningful relationship was Elizabeth, the woman who first introduced her to the language of flowers. Because of a catastrophe for which Victoria herself is to blame (I won't spoil it for you) they have become estranged, and now Victoria is living rough. Desperate for work, she ends up in a florist's shop where her gifts with ascribing meaning to flowers are appreciated at last.

But life is not that simple, and Grant, an acquaintance from the past turns up.From there, things grow more complicated, and after they begin a relationship, Victoria becomes pregnant. Through a series of flashbacks the reader begins to understand what happened during Victoria's childhood to make her so distrustful of herself and others.

This book has been available for a while and has won awards. I imagine by now it is a book club classic, because I thoroughly enjoyed it. It is a well-written and absorbing read. You can watch Vanessa talk about writing her novel here

Here is my floral review, taken from the dictionary at the back of the novel.

Lisianthus - appreciation

Lisianthus - appreciation

Rose, orange - fascination

Rose, orange - fascination

Sweet Pea - delicate pleasures

Sweet Pea - delicate pleasures

This Image comes from Joyce Tice's website

This Image comes from Joyce Tice's website The Language of Flowers tells the story of Victoria, a homeless eighteen year old and her passion for the meanings of flowers.

The Language of Flowers tells the story of Victoria, a homeless eighteen year old and her passion for the meanings of flowers.Victoria has been brought up in foster care, and the only adult with whom she had a meaningful relationship was Elizabeth, the woman who first introduced her to the language of flowers. Because of a catastrophe for which Victoria herself is to blame (I won't spoil it for you) they have become estranged, and now Victoria is living rough. Desperate for work, she ends up in a florist's shop where her gifts with ascribing meaning to flowers are appreciated at last.

But life is not that simple, and Grant, an acquaintance from the past turns up.From there, things grow more complicated, and after they begin a relationship, Victoria becomes pregnant. Through a series of flashbacks the reader begins to understand what happened during Victoria's childhood to make her so distrustful of herself and others.

This book has been available for a while and has won awards. I imagine by now it is a book club classic, because I thoroughly enjoyed it. It is a well-written and absorbing read. You can watch Vanessa talk about writing her novel here

Here is my floral review, taken from the dictionary at the back of the novel.

Lisianthus - appreciation

Lisianthus - appreciation Rose, orange - fascination

Rose, orange - fascination Sweet Pea - delicate pleasures

Sweet Pea - delicate pleasures

Published on April 06, 2012 10:36

April 3, 2012

Transparency for writers - how not to point at yourself

When writing a book, I am obsessed by the quality of my own writing. I agonize over choice of words, apposite phrases, clever ways to convey what I want to say. When a reader reads a book they don't want to see any of that - they want to hear the story. They want the author to be transparent. This is why we are urged to use the word "said" for our speech attributions - a word that is neutral, invisible. As soon as we say "retorted" or "quipped" or (heaven help us) "declaimed", then we are pointing at ourselves with the "look at me I'm a writer" finger. The more the writer gets in the way of the story, the less involved in the reality of the story the reader will be.

Likewise, too many adverbs or exclamation marks make the writer suddenly appear at the reader's shoulder as convincer -

e.g "Shut up!" he said crossly.

instead of, "Shut up," he said.

The writer is trying to force the reader to understand what they have probably already understood - thus making another unwanted appearance.

Too many similes or metaphors also point to our own cleverness, and can bring the reader up short.

eg Writer : "The water was black as treacle."

Reader: "Black as treacle? Is treacle black? What does she mean?"

Hey presto, the writer is muscling in again.

A lot of the knack of transparency is scrupulous awareness. If you are particularly proud of a phrase, view it with suspicion! It is probably a phrase where you are showing off, and therefore putting yourself between the reader and the page. Awareness for a writer is about being able to put yourself in the reader's seat and having the courage to remove your cleverness in favour of the truth of the story.

Many writers think that if they give up pointing at themselves they will lose their own unique voice. This is not so, as your voice will be there even more strongly if you get your ego out of the way of it.

This idea applies as much to life as it does to creativity.

The best book I can recommend on awareness in general is Awareness by Anthony de Mello. Eminently sane advice without any new-age nonsense.

The best book I can recommend on awareness in general is Awareness by Anthony de Mello. Eminently sane advice without any new-age nonsense.

For looking at this topic from a writer's perspective, the writer Dorothea Brande, (whose book, "Becoming a Writer" has been a classic for the inward journey since the 1930's) has another work, "Wake up and live!" available for free as a pdf here:

http://lesecret.net/DorotheaBrande-WakeUpAndLive.pdf

Although a little dated, it has some excellent ideas about how to succeed creatively.

As some people know, I am a great promoter of meditation in all its forms - here is a nice post by the writer Orna Ross on the benefits of meditation and awareness for writers: http://janefriedman.com/2012/01/02/meditation-increases-creativity/

And on a completely different topic, for anyone interested, my post on 17th Century Garden Design for Women is over at the English Historical Fiction Authors site. And you can win a copy of The Lady's Slipper at Brits United. (Until 5th April)

Likewise, too many adverbs or exclamation marks make the writer suddenly appear at the reader's shoulder as convincer -

e.g "Shut up!" he said crossly.

instead of, "Shut up," he said.

The writer is trying to force the reader to understand what they have probably already understood - thus making another unwanted appearance.

Too many similes or metaphors also point to our own cleverness, and can bring the reader up short.

eg Writer : "The water was black as treacle."

Reader: "Black as treacle? Is treacle black? What does she mean?"

Hey presto, the writer is muscling in again.

A lot of the knack of transparency is scrupulous awareness. If you are particularly proud of a phrase, view it with suspicion! It is probably a phrase where you are showing off, and therefore putting yourself between the reader and the page. Awareness for a writer is about being able to put yourself in the reader's seat and having the courage to remove your cleverness in favour of the truth of the story.

Many writers think that if they give up pointing at themselves they will lose their own unique voice. This is not so, as your voice will be there even more strongly if you get your ego out of the way of it.

This idea applies as much to life as it does to creativity.

The best book I can recommend on awareness in general is Awareness by Anthony de Mello. Eminently sane advice without any new-age nonsense.

The best book I can recommend on awareness in general is Awareness by Anthony de Mello. Eminently sane advice without any new-age nonsense.For looking at this topic from a writer's perspective, the writer Dorothea Brande, (whose book, "Becoming a Writer" has been a classic for the inward journey since the 1930's) has another work, "Wake up and live!" available for free as a pdf here:

http://lesecret.net/DorotheaBrande-WakeUpAndLive.pdf

Although a little dated, it has some excellent ideas about how to succeed creatively.

As some people know, I am a great promoter of meditation in all its forms - here is a nice post by the writer Orna Ross on the benefits of meditation and awareness for writers: http://janefriedman.com/2012/01/02/meditation-increases-creativity/

And on a completely different topic, for anyone interested, my post on 17th Century Garden Design for Women is over at the English Historical Fiction Authors site. And you can win a copy of The Lady's Slipper at Brits United. (Until 5th April)

Published on April 03, 2012 06:40

March 28, 2012

Writers in the 17th century were obsessed by character

A jobbing writer in the 17th century, just like me, was obsessed by characters. This is because the News Sheets of the day from London were dull and factual, designed to inform rather than entertain.

A jobbing writer in the 17th century, just like me, was obsessed by characters. This is because the News Sheets of the day from London were dull and factual, designed to inform rather than entertain.The Weekly News and the London Courant were the first papers (1622), followed by the London Gazette in 1663. But none of these papers ran what we would call today "human interest" stories.

So a new wave of character writing sprang up to give the public what we would call entertainment, or tabloid stories. Wycherley the playwright lists the common targets of this new breed of writer:

"lying jests against the common lawyer; handsome conceits against the fine courtier,delicate quirks against the rich cuckold and citizen."

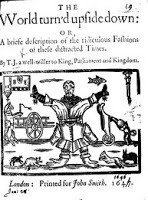

Also popular subjects were ridiculing the fads and fashions of the day, as in this pamphlet about ridiculous fashions, The World Turned Upside Down.In order to get material, the seventeenth century writer

"frequents clubs and coffeee houses, the markets of news, where he engrosses all he can light upon: and if that not prove sufficient, he is forced to add a lie or two of his own making.." (Samuel Butler)

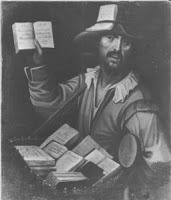

So, not so different from tabloid journalists of today then. The writer of the 17th century was mostly printed in pamphlets and chapbooks, pocket sized thin booklets that could be easily carried for sale on the street. On the left you can see a peddlar with a tray of books and chapbooks. The upright citizen's greatest fear was that he would feature in one of these and his reputation be ruined, a fact I exploited in my book The Gilded Lily.I used some of the larger than life characters in my book too - the avaricious pawnbroker, and the swaggering rake, as described by Rochester:

. Room, room for a Blade of the town,That takes delight in roaring,Who all day long rambles up and down,And at night in the streets lies snoring.

. Room, room for a Blade of the town,That takes delight in roaring,Who all day long rambles up and down,And at night in the streets lies snoring.

That for the noble name of SparkDoes his companions rally,Commits an outrage in the dark,Then slinks into an alley.

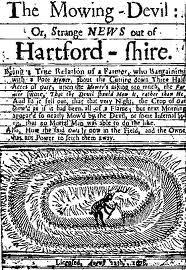

Apart from characters, the sensational and unbelievable made easy subjects, often with lurid woodcut illustrations. See below for The Mowing Devil and The Womanish Man.

Today pamphlets and chapbooks are popular for poetry, but there is a whole range of possibilities inherent in this medium, for a few ideas about chapbooks today, visit - The Book Designer

For more in depth information on 17th century pamphleteering I recommend The Function of the New Media in the 17th Century

Thanks to The Newberry, Chicago

Bodleian Library Collection article

Published on March 28, 2012 05:44

March 26, 2012

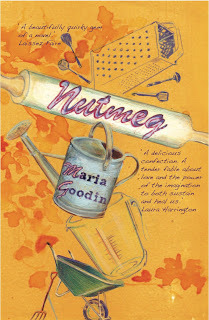

Nutmeg - a perfect little novel

I received Maria Goodin's debut novel via the Amazon Vine programme, having heard it was already set to be translated into four languages even before publication. Published by Legend Press - a small independent publisher, I can quite see why.

I was totally enchanted by this novel which is at once funny, moving and thought-provoking.

The story hinges around the relationship between Meg and her eccentric mother, who is terminally ill. The book is a sensory delight as Meg's mother is obsessed with cooking. What's more she has never told Meg the truth about her childhood but has told her stories that fictionalise Meg's life. Meg's memories are made from her mother's stories. Most of the stories involve food - the tastes and smells of pastry and cakes, herbs and spices. Rebelling against this fictional life, Meg takes refuge in science and cold hard facts. But cold hard facts cannot tell the truth as well as fiction can, and it is this that makes the book so engrossing.

Meg's mother is endearing precisely because of her story-telling and eccentricity, something which Meg's boyfriend, the rational Mark, sees as lies and mental illness. Mark is determined to cling to his own myth of scientific sanity, and his attempts to do so mean he rides rough shod over others sensibilities. When Meg eventually finds out the truth about her childhood, she is left wondering whether the memories her mother invented for her gave her a better start in life than the truth.

The divide between fact and fiction is a slippery one, and one which Maria Goodin exploits brilliantly. So much so, that at the end of the book when Meg's mother's funeral arrives you are left wondering how much of Meg's portrayal of it is real and how much of Meg's story was "True".

Tender, funny and poignant, this has definitely been the highlight of my reading year so far, and one I shall be recommending to all my friends.

Check out Legend Press's website for an extract, or to buy a copy.

Published on March 26, 2012 09:10

March 23, 2012

My New Book Resolutions

I've just finished book number three, eighteen months of research, and 150,000 words later and it is finally done and off to my editor. It always amazes me that what takes so long for me to write can be devoured so quickly by a reader. And isn't it sod's law that the moment the book has gone off, I suddenly remember lots of little errors I should have corrected.

And it hardly seems a minute since it was last September and I was on my research trip to Seville, to try to fill in the gaps in my research and geography that could only be done actually in Spain. The tapas and warm breezes seem a long time ago now after months of writing at the computer.

Outside the Museum in Seville, bag contains camera and notebook!The last few months I have thought of little else but the novel, and as soon as I had finished it I succumbed to the dreaded flu virus. So instead of all the enjoyable things I'd planned to do, like enjoy coffee with friends again and spend more time out side in the garden I've had six days in bed with the lemsip and too many hankies.

Outside the Museum in Seville, bag contains camera and notebook!The last few months I have thought of little else but the novel, and as soon as I had finished it I succumbed to the dreaded flu virus. So instead of all the enjoyable things I'd planned to do, like enjoy coffee with friends again and spend more time out side in the garden I've had six days in bed with the lemsip and too many hankies.

But it has allowed me to stop and think about the pressures on us as writers and to re-assess my priorities before I begin another novel. It also allowed me to read - and in doing that enjoy the creations of other writers. Somehow when I'm in the middle of a novel I don't make enough time for just reading.

The beautiful Alcazar, SevilleSo here are my 'new book' resolutions, which will hopefully prevent me from taking to my bed when the next one is done.

The beautiful Alcazar, SevilleSo here are my 'new book' resolutions, which will hopefully prevent me from taking to my bed when the next one is done.

i. Walk more. I live in a beautiful part of the world, but spend far too much time in front of a screen. To do this, I'll need to be organised, so that I waste less time on inessential computer tasks.

ii Rationalise my on-line social networking. When I first became a writer I joined every site that would have me, thinking that all publicity is good, right? But now I realise I can't possibly do it all if I want to have a life that isn't solely virtual. Although I have made some lovely contacts online, much social networking seems to be intensely competitive and motivated by the fear that if you don't do it your book will fail. But like most of us, I don't want to be under constant pressure, and from now on will only do social networking I think I can genuinely enjoy.And I hunger after the real - in life, in my fiction, and in my relationships with people.

iii. I miss my paintbrush now I'm no longer involved in scenography, so I thought I might join an art group. Getting out and about is essential if I'm not to turn into an unsociable hunched-over old lady who can only talk about her latest book.

iv. The writing is my greatest pleasure so I'm going to move my timetable to give me my optimum writing time (for me 9am - 1pm), and write my first draft quicker. I used to think eighteen months was a long time, but it goes so fast! I've realised I need much longer for the editing than I do for the drafting, so I'll aim to get all the research and a first draft done in nine months which will give me much more editing time. I love the editing, a chance to make it shine whilst knowing you do actually have a book in front of you.

v.Try to make the next book shorter! This morning Past Times Books (see logo on the right) let me know that they are now going to stock novellas of over 17,500 words. If only! I think I'm probably onto a loser with this one. I could write two short novels instead of one long one, I muse. Trouble is, I rather like the feel of a good meaty historical novel. And I really enjoyed Labyrinth and Pillars of the Earth and Wolf Hall, and had no trouble making it to the end. If the story grips you, then it grips you and I for one am quite happy with a big thick brick of a book.

vi. Eat a proper meal at least once a day without trying to read research papers or books at the same time.

Below you can see some of the books I used for my research during the last year. Most of them have the odd toast crumb or biscuit crumb between the pages as well as my markers. Though I have to say, I do look after my books!

As for my resolutions, I seem to remember making the same ones after I'd finished The Gilded Lily about eighteen months ago, so I'll see if I do better this time round.

What are your resolutions when you start a new project? And do you stick to them?

Which reminds me, it looks like lunch time. Off to make a healthy meal of pea and courgette soup.

And it hardly seems a minute since it was last September and I was on my research trip to Seville, to try to fill in the gaps in my research and geography that could only be done actually in Spain. The tapas and warm breezes seem a long time ago now after months of writing at the computer.

Outside the Museum in Seville, bag contains camera and notebook!The last few months I have thought of little else but the novel, and as soon as I had finished it I succumbed to the dreaded flu virus. So instead of all the enjoyable things I'd planned to do, like enjoy coffee with friends again and spend more time out side in the garden I've had six days in bed with the lemsip and too many hankies.

Outside the Museum in Seville, bag contains camera and notebook!The last few months I have thought of little else but the novel, and as soon as I had finished it I succumbed to the dreaded flu virus. So instead of all the enjoyable things I'd planned to do, like enjoy coffee with friends again and spend more time out side in the garden I've had six days in bed with the lemsip and too many hankies.But it has allowed me to stop and think about the pressures on us as writers and to re-assess my priorities before I begin another novel. It also allowed me to read - and in doing that enjoy the creations of other writers. Somehow when I'm in the middle of a novel I don't make enough time for just reading.

The beautiful Alcazar, SevilleSo here are my 'new book' resolutions, which will hopefully prevent me from taking to my bed when the next one is done.

The beautiful Alcazar, SevilleSo here are my 'new book' resolutions, which will hopefully prevent me from taking to my bed when the next one is done.i. Walk more. I live in a beautiful part of the world, but spend far too much time in front of a screen. To do this, I'll need to be organised, so that I waste less time on inessential computer tasks.

ii Rationalise my on-line social networking. When I first became a writer I joined every site that would have me, thinking that all publicity is good, right? But now I realise I can't possibly do it all if I want to have a life that isn't solely virtual. Although I have made some lovely contacts online, much social networking seems to be intensely competitive and motivated by the fear that if you don't do it your book will fail. But like most of us, I don't want to be under constant pressure, and from now on will only do social networking I think I can genuinely enjoy.And I hunger after the real - in life, in my fiction, and in my relationships with people.

iii. I miss my paintbrush now I'm no longer involved in scenography, so I thought I might join an art group. Getting out and about is essential if I'm not to turn into an unsociable hunched-over old lady who can only talk about her latest book.

iv. The writing is my greatest pleasure so I'm going to move my timetable to give me my optimum writing time (for me 9am - 1pm), and write my first draft quicker. I used to think eighteen months was a long time, but it goes so fast! I've realised I need much longer for the editing than I do for the drafting, so I'll aim to get all the research and a first draft done in nine months which will give me much more editing time. I love the editing, a chance to make it shine whilst knowing you do actually have a book in front of you.

v.Try to make the next book shorter! This morning Past Times Books (see logo on the right) let me know that they are now going to stock novellas of over 17,500 words. If only! I think I'm probably onto a loser with this one. I could write two short novels instead of one long one, I muse. Trouble is, I rather like the feel of a good meaty historical novel. And I really enjoyed Labyrinth and Pillars of the Earth and Wolf Hall, and had no trouble making it to the end. If the story grips you, then it grips you and I for one am quite happy with a big thick brick of a book.

vi. Eat a proper meal at least once a day without trying to read research papers or books at the same time.

Below you can see some of the books I used for my research during the last year. Most of them have the odd toast crumb or biscuit crumb between the pages as well as my markers. Though I have to say, I do look after my books!

As for my resolutions, I seem to remember making the same ones after I'd finished The Gilded Lily about eighteen months ago, so I'll see if I do better this time round.

What are your resolutions when you start a new project? And do you stick to them?

Which reminds me, it looks like lunch time. Off to make a healthy meal of pea and courgette soup.

Published on March 23, 2012 08:01

March 22, 2012

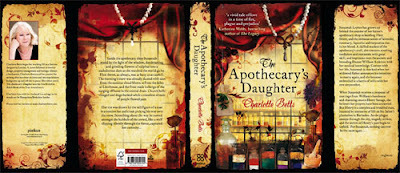

The Apothecary's Daughter

The Apothecary's Daughter delights the senses.

The Apothecary's Daughter delights the senses.I love the design of this book, which makes a change from headless women or vast expanses of flowing skirt. It is nicely designed inside too, with well-chosen period typography for the title pages and a good clear readable font.

You would not think London in the time of the plague would be good material for a romantic novel, but Charlotte Betts pulls it off superbly. The book tells the tale of Susannah, who, after the re-marriage of her father to the shallow and demanding Arabella, is forced to leave her erstwhile home to find marriage herself. As in all romances, the path of true love does not run smoothly, and in Charlotte Betts's novel, there are obstacles aplenty - not least her new husband, Henry Savage, who turns out to have quite a few secrets Susannah doesn't know about. The novel does not shirk from portraying the harsher realities of everyday life in the 17th century - slavery, the non-participation of women in society, and these aspects add depth to the story.

Unlike many other sketchily researched romances, this one really deserves the title "historical romance" as both aspects are in perfect balance.Vivid and engaging, the research is thoroughly done and succeeds in giving us an insight into this neglected period of English history, with all the smells of the apothecary's trade, the sage, the turpentine, the juniper. If you are looking for a cracking good story, and to be transported to another age, you really can't beat this.

Published on March 22, 2012 09:11

February 10, 2012

Blending Historical Fact with Fiction - an interview with Terence Morgan

Hello Terence, lovely to have you here.

Tell us a little bit about your research and how you weld the real history in your books to the fictional elements.

It's a bit like building a wall; you have these known historical facts, which are the bricks, and they have to be laid in a certain sequence. The stuff you make up is the cement that holds them together, and that can be thrown in where it fits. As long as it doesn't make the wall unsteady, it can go anywhere.

I start with the big scenes, writing things that I know have to appear in the book somewhere and developing them, sometimes in quite a lot of detail. In 'The Shadow Prince', that means the things which we know happened historically to Perkin -- his adventures in Ireland, his marriage in Scotland, his invasion of England, his capture by Henry VII and so on. That way I have a string of events with large gaps in

I start with the big scenes, writing things that I know have to appear in the book somewhere and developing them, sometimes in quite a lot of detail. In 'The Shadow Prince', that means the things which we know happened historically to Perkin -- his adventures in Ireland, his marriage in Scotland, his invasion of England, his capture by Henry VII and so on. That way I have a string of events with large gaps in

between. Then I start to look for what MIGHT have happened in the gaps, and what COULD have happened (and of course what could NOT have happened) and start to work on the ones that look most promising. That's always a lot of fun, and sometimes very rewarding. It can lead to total re-interpretation of why things happened they way they did. I tell the story in the afterword to 'The Shadow Prince' of how I bought two books for a total of 65p, one ('Cod', by Mark Kurlansky, 55p) in an Oxfam shop and the other ('The Columbus Myth' by Ian Wilson) for 10p in the parish jumble sale, and managed to get an enormous amount of information out of them that led to a complete rethink of the plot. They were a rich mine of ideas that in the end led to a complete re-write of the ending.

I also try to think thematically. In 'The Shadow Prince', for example, I had a clear theme of appearance and reality, disguise and role-playing, that ran right through it, so I looked for places where I could build on that or enhance it in some way, which in his case was relatively easy to do and fitted in with what I needed.Then I look for real people whom my protagonist might have met. In 'The Master of Bruges' I was lucky enough to be able to throw in all sorts of disparate historical characters from William Caxton to Richard III, from Charles the Bold to the magician Tremethius. 'The Shadow Prince' is the same (I won't put any spoilers in by telling you who he meets). I think I'm the despair of my editor, who tries to remove my knowing jokes. I managed to keep a couple this time, though (my favourite is on page 69).

What excited you about the fifteenth century and made you want to write The Shadow Prince?

It was the obvious thing to do. Macmillan wanted another book after 'The Master of Bruges', and I didn't really have anything in mind. Then someone suggested a sequel, and I realised that at the end of 'Master' I had left the door open for a follow-up with Prince Richard. The fact that there were big gaps in the story of Perkin Warbeck meant that I had a lot of leeway, the many unanswered or unsatisfactorily answered questions about him meant that I could choose the interpretation I wanted (or needed, as the case may be), and another major factor was that most of the groundwork for the research was already done, as I had covered Flanders and the Wars of the Roses in the first book and many of the same characters were involved with Perkin. I had had so much fun with 'Master' that I looked forward to repeating it -- frequent trips to Belgium, necessitating even more frequent sampling of Flemish beer - you get the picture.

Are you a plotter or a seat-of-the-pants writer? Tell us a bit about your writing process.

As you can tell from the above, I'm probably a bit of both. As at the moment I'm writing historical novels, there are obvious constraints that I have to observe - I can't have impossible things happening, for example, or characters meeting who lived at different times, so there is a clear plotting element to my books. On the other hand, I am constantly looking for new interpretations of history, so I do tend to go off down the highways and byways in search of the odd and the curious. Of course, not all of the stuff I find ends up in the finished manuscript, but enough does to make it worthwhile.

Have you always been a History buff?

Yes. I used to love it at school, but I enjoyed the peripheral bits rather than the political stuff. As a result it was the only O-level I failed, because I spent too long writing on battles rather than treaties, or individual feats of exploration rather than political takeovers -- the adventures of Lewis and Clark rather than the ramifications of the Louisana Purchase, and so on. About forty-five years ago I discovered the joys of historical wargaming, and that led to lots of researching of battles, uniforms, tactics and so on.

Who or what has made the most difference to your writing?

Who or what has made the most difference to your writing?

I've always enjoyed the sort of story which takes a minor character from history and weaves them into a plot involving major historical characters. I suppose Lew Wallace's 'Ben-Hur' was the first of this type I read as a boy, and then there was Robert Graves' 'I, Claudius'. Then when I was a student George MacDonald Fraser's 'Flashman' series started to appear, and I decided that if I ever wrote stories, that would be the type I would write. I was chuffed to bits when an earlier reviewer of 'The Master of Bruges' compared it to a Flashman.The biggest difference, though, was caused by retirement. I suddenly had time to work on plotting and writing and researching, and it's no coincidence that I didn't publish my first novel until I was sixty-five. I know many people are able to combine a full-time job with writing, and of course I have enormous respect for them, but I never could. I suppose I was just too lazy. I wrote articles for papers and magazines, but they are just short things you can toss off in an evening and don't impinge on family time, and similarly I wrote schoolbooks, but they were based on the lesson notes I had to write for class, so they didn't take up much time either. Novel writing is a different cauldron of cod altogether.

Do you have a special place to write or a special routine?

If I use the phrase 'book-lined study' then readers will get the wrong idea. I do have a study (a converted bedroom), and it is book-lined in the sense that I have seven enormous bookcases that I've picked up from jumble sales and charity shops and which are filled with an eclectic and completely disorganised host of tomes, but I defy anyone to find anything. (I, on the other hand, am blessed with one of those spatial memories than can recall exactly where I saw something, even if it was four years ago, and go straight to it. Having said that, my glasses are an exception to the rule.) I am an indiscriminately enthusiastic purchaser of books, and buy them far faster than I can read them. I discovered the Hakluyt Society a year ago, and now have about forty of their publications dotted about the room. A couple of them found their way into 'The Shadow Prince' by various circuitous routes.Routine? Perish the thought. I write when I remember to, when the agenbite of inwit pricks (am I using that correctly?) I am extremely disorganised.

What do you hope readers will love about your book?

I think it has a certain swashbucking charm, some humour, and a nice twist in the tale that I find pleasing. History students will, I hope, chuckle at the solutions I have postulated to a number of mysteries. I got a five-star review in the Telegraph soon after publication, and the reviewer seemed to find in the book all the things I hoped were there. If the readers have half as much fun reading it as I did writing it they're (I hope I'm not too presumptuous in using the plural!) in for a good time.

Thank you very much Terence for taking the time to answer my questions, and all the best with

The Shadow Prince.

Terence's other book, The Master of Bruges is also published by Macmillan.

Tell us a little bit about your research and how you weld the real history in your books to the fictional elements.

It's a bit like building a wall; you have these known historical facts, which are the bricks, and they have to be laid in a certain sequence. The stuff you make up is the cement that holds them together, and that can be thrown in where it fits. As long as it doesn't make the wall unsteady, it can go anywhere.

I start with the big scenes, writing things that I know have to appear in the book somewhere and developing them, sometimes in quite a lot of detail. In 'The Shadow Prince', that means the things which we know happened historically to Perkin -- his adventures in Ireland, his marriage in Scotland, his invasion of England, his capture by Henry VII and so on. That way I have a string of events with large gaps in

I start with the big scenes, writing things that I know have to appear in the book somewhere and developing them, sometimes in quite a lot of detail. In 'The Shadow Prince', that means the things which we know happened historically to Perkin -- his adventures in Ireland, his marriage in Scotland, his invasion of England, his capture by Henry VII and so on. That way I have a string of events with large gaps in between. Then I start to look for what MIGHT have happened in the gaps, and what COULD have happened (and of course what could NOT have happened) and start to work on the ones that look most promising. That's always a lot of fun, and sometimes very rewarding. It can lead to total re-interpretation of why things happened they way they did. I tell the story in the afterword to 'The Shadow Prince' of how I bought two books for a total of 65p, one ('Cod', by Mark Kurlansky, 55p) in an Oxfam shop and the other ('The Columbus Myth' by Ian Wilson) for 10p in the parish jumble sale, and managed to get an enormous amount of information out of them that led to a complete rethink of the plot. They were a rich mine of ideas that in the end led to a complete re-write of the ending.

I also try to think thematically. In 'The Shadow Prince', for example, I had a clear theme of appearance and reality, disguise and role-playing, that ran right through it, so I looked for places where I could build on that or enhance it in some way, which in his case was relatively easy to do and fitted in with what I needed.Then I look for real people whom my protagonist might have met. In 'The Master of Bruges' I was lucky enough to be able to throw in all sorts of disparate historical characters from William Caxton to Richard III, from Charles the Bold to the magician Tremethius. 'The Shadow Prince' is the same (I won't put any spoilers in by telling you who he meets). I think I'm the despair of my editor, who tries to remove my knowing jokes. I managed to keep a couple this time, though (my favourite is on page 69).

What excited you about the fifteenth century and made you want to write The Shadow Prince?

It was the obvious thing to do. Macmillan wanted another book after 'The Master of Bruges', and I didn't really have anything in mind. Then someone suggested a sequel, and I realised that at the end of 'Master' I had left the door open for a follow-up with Prince Richard. The fact that there were big gaps in the story of Perkin Warbeck meant that I had a lot of leeway, the many unanswered or unsatisfactorily answered questions about him meant that I could choose the interpretation I wanted (or needed, as the case may be), and another major factor was that most of the groundwork for the research was already done, as I had covered Flanders and the Wars of the Roses in the first book and many of the same characters were involved with Perkin. I had had so much fun with 'Master' that I looked forward to repeating it -- frequent trips to Belgium, necessitating even more frequent sampling of Flemish beer - you get the picture.

Are you a plotter or a seat-of-the-pants writer? Tell us a bit about your writing process.

As you can tell from the above, I'm probably a bit of both. As at the moment I'm writing historical novels, there are obvious constraints that I have to observe - I can't have impossible things happening, for example, or characters meeting who lived at different times, so there is a clear plotting element to my books. On the other hand, I am constantly looking for new interpretations of history, so I do tend to go off down the highways and byways in search of the odd and the curious. Of course, not all of the stuff I find ends up in the finished manuscript, but enough does to make it worthwhile.

Have you always been a History buff?

Yes. I used to love it at school, but I enjoyed the peripheral bits rather than the political stuff. As a result it was the only O-level I failed, because I spent too long writing on battles rather than treaties, or individual feats of exploration rather than political takeovers -- the adventures of Lewis and Clark rather than the ramifications of the Louisana Purchase, and so on. About forty-five years ago I discovered the joys of historical wargaming, and that led to lots of researching of battles, uniforms, tactics and so on.

Who or what has made the most difference to your writing?

Who or what has made the most difference to your writing?I've always enjoyed the sort of story which takes a minor character from history and weaves them into a plot involving major historical characters. I suppose Lew Wallace's 'Ben-Hur' was the first of this type I read as a boy, and then there was Robert Graves' 'I, Claudius'. Then when I was a student George MacDonald Fraser's 'Flashman' series started to appear, and I decided that if I ever wrote stories, that would be the type I would write. I was chuffed to bits when an earlier reviewer of 'The Master of Bruges' compared it to a Flashman.The biggest difference, though, was caused by retirement. I suddenly had time to work on plotting and writing and researching, and it's no coincidence that I didn't publish my first novel until I was sixty-five. I know many people are able to combine a full-time job with writing, and of course I have enormous respect for them, but I never could. I suppose I was just too lazy. I wrote articles for papers and magazines, but they are just short things you can toss off in an evening and don't impinge on family time, and similarly I wrote schoolbooks, but they were based on the lesson notes I had to write for class, so they didn't take up much time either. Novel writing is a different cauldron of cod altogether.

Do you have a special place to write or a special routine?

If I use the phrase 'book-lined study' then readers will get the wrong idea. I do have a study (a converted bedroom), and it is book-lined in the sense that I have seven enormous bookcases that I've picked up from jumble sales and charity shops and which are filled with an eclectic and completely disorganised host of tomes, but I defy anyone to find anything. (I, on the other hand, am blessed with one of those spatial memories than can recall exactly where I saw something, even if it was four years ago, and go straight to it. Having said that, my glasses are an exception to the rule.) I am an indiscriminately enthusiastic purchaser of books, and buy them far faster than I can read them. I discovered the Hakluyt Society a year ago, and now have about forty of their publications dotted about the room. A couple of them found their way into 'The Shadow Prince' by various circuitous routes.Routine? Perish the thought. I write when I remember to, when the agenbite of inwit pricks (am I using that correctly?) I am extremely disorganised.

What do you hope readers will love about your book?

I think it has a certain swashbucking charm, some humour, and a nice twist in the tale that I find pleasing. History students will, I hope, chuckle at the solutions I have postulated to a number of mysteries. I got a five-star review in the Telegraph soon after publication, and the reviewer seemed to find in the book all the things I hoped were there. If the readers have half as much fun reading it as I did writing it they're (I hope I'm not too presumptuous in using the plural!) in for a good time.

Thank you very much Terence for taking the time to answer my questions, and all the best with

The Shadow Prince.

Terence's other book, The Master of Bruges is also published by Macmillan.

Published on February 10, 2012 03:02

January 26, 2012

The Last Summer by Judith Kinghorn - sweeping historical romance

I read the paperback version of this which had a different cover showing a large country house, but I don't think that is out in shops yet. (I got it from Amazon Vine) But you can pre-order!

I read the paperback version of this which had a different cover showing a large country house, but I don't think that is out in shops yet. (I got it from Amazon Vine) But you can pre-order!I read it on a train to London, and it took me two journeys to demolish it - a substantial novel then.

The Last Summer is set during the beginnings of World War I and tells the story of Clarissa, who loses her luxurious lifestyle and her home during the book.Impeccably written and well-researched this is an atmospheric and haunting read. It takes the reader from languorous summer days by the lake on a country estate to the horror of the trenches with equal aplomb.

The love story at its heart unfolds over sixteen years or so, so this is no flash in the pan romance but the real thing. Judith Kinghorn skilfully navigates our journey through love and loss, and despite the fact the reader knows that Clarissa and Tom must somehow find the inevitable happy ending the tension is nicely built through all the different episodes.Part of the story unfolds through letters which hold a secret not revealed until the end.

The social and historical background feels real. Clarissa's journey from society debutante to independent woman who wants to work for herself must be the journey many women took in this period and the book highlights this nicely. The back of the novel says it was "the end of a belle epoque" and Clarissa senses this before it is made real to her through the events in the story. People have likened this book to Downton Abbey, but it is not quite as cosy. Death and duty are here too, and the stifling repression of the moneyed classes.

This is a perfect balance of romance and grit, by a great new writer. Don't miss it.

Published on January 26, 2012 14:40