Deborah Swift's Blog, page 44

August 23, 2012

Bippity Boppety Blog Hop - Researching The Lady's Slipper

In honour of the Bippity Boppety Blog Hop, I am offering two copies of The Lady's Slipper worldwide, just leave a comment about my post to enter. Here is the US edition of the book, on sale next to Gulliver's Travels, sadly I am no relation to the famous Jonathan Swift.

In honour of the Bippity Boppety Blog Hop, I am offering two copies of The Lady's Slipper worldwide, just leave a comment about my post to enter. Here is the US edition of the book, on sale next to Gulliver's Travels, sadly I am no relation to the famous Jonathan Swift.

Research and Historical Fiction Many people have asked me about how I do my research and how much time it takes to write a historical novel. So in this post I will take a little about my process, and also tell you about some of the some of the books I found invaluable in my research for The Lady’s Slipper.

My approach was not to try to know everything, but to read some general books on the 17th Century to get a broad picture, and then to start to write the book, filling in the gaps in my knowledge later. I keep a large notebook which is full of questions, for example, “How much was a loaf of bread in 1660?” “In a small village would there have been a bakery, or did people bake at home?” “What sort of bread? Millet? Wheat? Rye?” The answer to the last question was that in Westmorland where the book is set bread was called “clapbread” and was a flat cake made of oats, and it would keep for nearly a month! They had special oak cupboards built into their cottages to keep it in over winter – frequently the answers are not what you expect but even more interesting.

So after getting the overview I write my story, but I am left with a bulging and quite daunting note book full of questions. I take a deep breath, start at the beginning again and find out the answers and facts and decide if they help or hinder the story. I think I enjoy the “detective” element of finding out the answers to obscure questions! I read a lot of non-fiction and I am eternally grateful to the “real” historians who supply me with the answers. Books such as The Weaker Vessel by Antonia Fraser which gives a record of women’s lives in the Civil War in their own voices, and Restoration London by Liza Picard which was indispensable for information about daily life. Another favourite was Birth, Marriage and Deathby David Cressy, which was always on my desk.

So after getting the overview I write my story, but I am left with a bulging and quite daunting note book full of questions. I take a deep breath, start at the beginning again and find out the answers and facts and decide if they help or hinder the story. I think I enjoy the “detective” element of finding out the answers to obscure questions! I read a lot of non-fiction and I am eternally grateful to the “real” historians who supply me with the answers. Books such as The Weaker Vessel by Antonia Fraser which gives a record of women’s lives in the Civil War in their own voices, and Restoration London by Liza Picard which was indispensable for information about daily life. Another favourite was Birth, Marriage and Deathby David Cressy, which was always on my desk. When I began writing The Lady’s Slipper I had no idea that my characters were going to end up on a ship, and of course I knew nothing at all about sailing ships, not even modern ones. No matter how many books I had read on the 17th century beforehand, it was unlikely I would have found out what I needed to know about Dutch Flute sailing ships without doing some very specific research. So I forced myself to read Patrick O’Brian’s books which are all set at sea, and what he doesn’t know about tall ships would probably fit on a postage stamp. They are the sort of historical fiction I would never normally pick up, but they are excellent. I also found out by emailing The Maritime Museum that the cow was stabled “aft”, and that foodstuffs were often sealed in dried mud to keep them fresh on board.

When I began writing The Lady’s Slipper I had no idea that my characters were going to end up on a ship, and of course I knew nothing at all about sailing ships, not even modern ones. No matter how many books I had read on the 17th century beforehand, it was unlikely I would have found out what I needed to know about Dutch Flute sailing ships without doing some very specific research. So I forced myself to read Patrick O’Brian’s books which are all set at sea, and what he doesn’t know about tall ships would probably fit on a postage stamp. They are the sort of historical fiction I would never normally pick up, but they are excellent. I also found out by emailing The Maritime Museum that the cow was stabled “aft”, and that foodstuffs were often sealed in dried mud to keep them fresh on board.

Wonderful Levens Hall, near where I live, on which I based Fisk Manor

Wonderful Levens Hall, near where I live, on which I based Fisk ManorTo write about people’s homes I spent time at a number of old houses including Levens Hall, which helped me to create Fisk Manor, the home of Geoffrey Fisk in the novel. There is nothing like walking down a 17thcentury staircase and feeling the polished wooden banisters and seeing the light pour in through mullioned windows. At Swarthmoor Hall I sat and wrote a scene at a gnarled and polished oak table where George Fox the Quaker leader may have sat when he lived there with Margaret Fell. After such an immersion in the past it feels very strange then to get in my car and zoom away!

The botanical facts about the orchid I researched through interviewing members of the Cypripedium Committee, a sort of plant mafia set up to protect the Lady’s Slipper. They meet behind closed doors and the location of the last remaining plant in Britainis a closely guarded secret even today. The single-minded enthusiasm of these men, and their dedication to preserving the plant for future generations gave me confidence in my heroine, Alice Ibbetson’s obsession with it. But I also read novels such as The Orchid Thiefand Tulip Fever, which treat similar themes.

The botanical facts about the orchid I researched through interviewing members of the Cypripedium Committee, a sort of plant mafia set up to protect the Lady’s Slipper. They meet behind closed doors and the location of the last remaining plant in Britainis a closely guarded secret even today. The single-minded enthusiasm of these men, and their dedication to preserving the plant for future generations gave me confidence in my heroine, Alice Ibbetson’s obsession with it. But I also read novels such as The Orchid Thiefand Tulip Fever, which treat similar themes. Being a costume designer I could not resist the Northampton Shoe Museum where there are many shoes on display. In The Lady’s Slipper Ella the maid is envious of her mistress’s slippers.Ella's story is told in The Gilded Lily, out in a few weeks time.

Often the research throws up new plotlines and then I will re-write scenes or chunks of the book to incorporate little-known or exciting research. I think to write historical fiction you have to enjoy this aspect of it because you are going to do an awful lot of it. When people ask me how long it takes to research the novel they are thinking in terms of a finite time, but actually I am researching all the time, my living room always has a pile of ten or twelve “current” books I am dipping into, not to mention photocopies and print-outs such as bits of the diaries of Pepys and George Fox and other helpful 17thcentury scribblers. Did I forget to mention the internet? The phone rings, and I half expect my husband to say, “Hang on, she’s googling.”

Often the research throws up new plotlines and then I will re-write scenes or chunks of the book to incorporate little-known or exciting research. I think to write historical fiction you have to enjoy this aspect of it because you are going to do an awful lot of it. When people ask me how long it takes to research the novel they are thinking in terms of a finite time, but actually I am researching all the time, my living room always has a pile of ten or twelve “current” books I am dipping into, not to mention photocopies and print-outs such as bits of the diaries of Pepys and George Fox and other helpful 17thcentury scribblers. Did I forget to mention the internet? The phone rings, and I half expect my husband to say, “Hang on, she’s googling.”This post first appeared on Amy Bruno's site Passages to the Past. Thank you Amy. Amy is organising

my Blog Tour for The Gilded Lily, find out more at http://www.hfvirtualbooktours.com/

Look to the right to grab the button for this blog hop!

<!-- end LinkyTools script --

Published on August 23, 2012 16:00

August 16, 2012

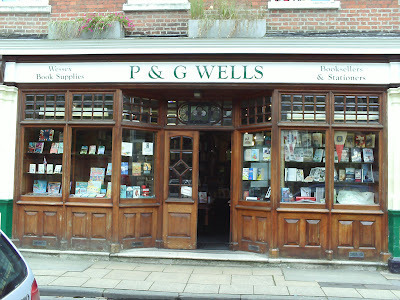

Buying from a Bookshop with Style

Last week I had the pleasure of visiting Winchester as part of my holidays. Just across the road from the Cathedral we came across this lovely bookshop, which to my mind is just what a bookshop should be. Each section had a hand-painted illustration above it.You can see the hand-painted signs above the shelves, including the spitfire for WWII, just under the bunting.

Last week I had the pleasure of visiting Winchester as part of my holidays. Just across the road from the Cathedral we came across this lovely bookshop, which to my mind is just what a bookshop should be. Each section had a hand-painted illustration above it.You can see the hand-painted signs above the shelves, including the spitfire for WWII, just under the bunting.

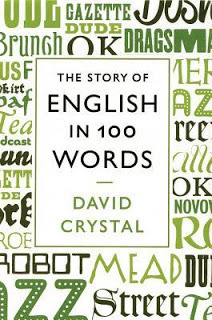

Of course we couldn't resist buying something and "The Story of English in 100 Words" by David Crystal seemed to be just the right sort of little hardback to get from this shop. I always enjoy books on etymology and words. He tells you a little more about the book in this article in The Telegraph

The book itself is fascinating.

The word so far that has caught my imagination is 'bone-house', a 10th century word-painting to describe a person by describing the body. This sort of description is called a 'kenning', from the old icelandic verb kenna - to know, where two words are put together to make a picture, as in a traveller being an 'earth-walker' or a ship being a 'wave-floater'. Further reading about the first word in the book can be found is here in a post on English Historical Fiction Authors by Richard Denning.

I could describe myself as a letter-tapper, a word-spewer, a coffee-gurgler, and a biscuit-muncher during my mornings at the keyboard, as well as a history-picker.

How would you describe yourself in a kenning?

Published on August 16, 2012 04:21

August 8, 2012

Men's Wars written by Women - Historical Fiction Reviews

Three of my favourite books this year feature male protagonists at war and a mostly male cast of characters - and interestingly all written by women. I'd recommend all three books to men and women, whatever you might think of their covers.

The first is "The Return of Captain John Emmett" by Elizabeth Speller.

This novel tells the story of an execution during the Great War. Laurence Bartram, himself consumed by grief at the loss of his wife and young son, is approached by a friend's wife to unravel the mystery of why he committed suicide. His investigations lead to the gradual piecing-together of an incident in the war. Similar to a detective mystery, most of the action is told by reports from characters who were at the scene, very much like examining the scene of a crime. In the novel references are made to Agatha Christie and Poirot, and this book has all the intricate plotting of a who-dunnit, except better, and with a much more moving revelation of the true conditions of war. As a historical fiction writer I enjoyed the fact that long parts of the book were reportage - how often are we told to show not tell? But these re-tellings in the characters own voices were gripping, and show that the author had really done her research. The horrors of trench warfare and the subsequent abandonment of trauma casualties post-war were brought chillingly to life. In the afterword she tells us that she used the papers of W.H.R Rivers who treated psychiatric casualties of the war and Jonathan Shay's Achilles in Vietnam as sources.

This novel tells the story of an execution during the Great War. Laurence Bartram, himself consumed by grief at the loss of his wife and young son, is approached by a friend's wife to unravel the mystery of why he committed suicide. His investigations lead to the gradual piecing-together of an incident in the war. Similar to a detective mystery, most of the action is told by reports from characters who were at the scene, very much like examining the scene of a crime. In the novel references are made to Agatha Christie and Poirot, and this book has all the intricate plotting of a who-dunnit, except better, and with a much more moving revelation of the true conditions of war. As a historical fiction writer I enjoyed the fact that long parts of the book were reportage - how often are we told to show not tell? But these re-tellings in the characters own voices were gripping, and show that the author had really done her research. The horrors of trench warfare and the subsequent abandonment of trauma casualties post-war were brought chillingly to life. In the afterword she tells us that she used the papers of W.H.R Rivers who treated psychiatric casualties of the war and Jonathan Shay's Achilles in Vietnam as sources.

Which brings me neatly to the second of my favourites - Madeline Miller's "Song of Achilles".

Of course this has won the Orange Prize for Fiction, but I was three-quarters through it when the prize was announced, so it did not influence my impressions of the book. Madeline Miller's version of the story of Achilles relies on building up an intimate picture of Achilles and Patroclus before the War at Troy actually starts. What I loved about this book from a writer's perspective was that the use of language was so lyrical. In a modern book it would be impossible to use terms such as 'the rosy gleam of his lip, the fevered green of his eyes' without it sounding ridiculous, yet in Miller's hands such language feels right. She has managed to make the book epic and Homerian. If the book has a weakness it is that the actual conflict (which in reality lasts ten years) takes a little too long to get going, but once it does the action is unputdownable. The early lyricism works just as well applied to battle, and the fact that some of the story is told from a dead man's point of view only increases its mystical effect.In this book we believe in the Gods, and in the terror of the Gods, and the power of human love.

Of course this has won the Orange Prize for Fiction, but I was three-quarters through it when the prize was announced, so it did not influence my impressions of the book. Madeline Miller's version of the story of Achilles relies on building up an intimate picture of Achilles and Patroclus before the War at Troy actually starts. What I loved about this book from a writer's perspective was that the use of language was so lyrical. In a modern book it would be impossible to use terms such as 'the rosy gleam of his lip, the fevered green of his eyes' without it sounding ridiculous, yet in Miller's hands such language feels right. She has managed to make the book epic and Homerian. If the book has a weakness it is that the actual conflict (which in reality lasts ten years) takes a little too long to get going, but once it does the action is unputdownable. The early lyricism works just as well applied to battle, and the fact that some of the story is told from a dead man's point of view only increases its mystical effect.In this book we believe in the Gods, and in the terror of the Gods, and the power of human love.

The third of my favourites is "Honour and the Sword" by AL Berridge.

Of the three, this is the most swashbuckling of my choices. It is written as a series of interviews or memoirs from France during the time of the 30 years war and so includes a number of different voices put together by a fictional professor - Edward Morton. Sounds complicated? Perhaps, but it works brilliantly. Like a patchwork this method gradually builds up the picture of events from all the partisan points of view. Told in the first person present tense, some of it is written in very modern-sounding English but this has the effect of drawing the reader in. Mostly told from the point of view of Jacques the stable lad, and his erstwhile employer's son, an aristocrat called Andre de Roland, the slow development of the relationship between these two boys is what glues the book together. We watch them through the highs and lows of warfare, through heroism and despair as Andre de Roland seeks to avenge his parents death at the hands of the Spanish. This book has some excellent set-piece action scenes, with gripping sword fights, pistols and cannon.At the climax the action zips from person to person in a few lines - and this filmic technique like cutting from shot to shot, was breathtaking.

Three great pieces of historical fiction, I recommend them all.

You can read an interview with AL Berridge here about why she enjoys to write books more normally associated with a male readership.

The first is "The Return of Captain John Emmett" by Elizabeth Speller.

This novel tells the story of an execution during the Great War. Laurence Bartram, himself consumed by grief at the loss of his wife and young son, is approached by a friend's wife to unravel the mystery of why he committed suicide. His investigations lead to the gradual piecing-together of an incident in the war. Similar to a detective mystery, most of the action is told by reports from characters who were at the scene, very much like examining the scene of a crime. In the novel references are made to Agatha Christie and Poirot, and this book has all the intricate plotting of a who-dunnit, except better, and with a much more moving revelation of the true conditions of war. As a historical fiction writer I enjoyed the fact that long parts of the book were reportage - how often are we told to show not tell? But these re-tellings in the characters own voices were gripping, and show that the author had really done her research. The horrors of trench warfare and the subsequent abandonment of trauma casualties post-war were brought chillingly to life. In the afterword she tells us that she used the papers of W.H.R Rivers who treated psychiatric casualties of the war and Jonathan Shay's Achilles in Vietnam as sources.

This novel tells the story of an execution during the Great War. Laurence Bartram, himself consumed by grief at the loss of his wife and young son, is approached by a friend's wife to unravel the mystery of why he committed suicide. His investigations lead to the gradual piecing-together of an incident in the war. Similar to a detective mystery, most of the action is told by reports from characters who were at the scene, very much like examining the scene of a crime. In the novel references are made to Agatha Christie and Poirot, and this book has all the intricate plotting of a who-dunnit, except better, and with a much more moving revelation of the true conditions of war. As a historical fiction writer I enjoyed the fact that long parts of the book were reportage - how often are we told to show not tell? But these re-tellings in the characters own voices were gripping, and show that the author had really done her research. The horrors of trench warfare and the subsequent abandonment of trauma casualties post-war were brought chillingly to life. In the afterword she tells us that she used the papers of W.H.R Rivers who treated psychiatric casualties of the war and Jonathan Shay's Achilles in Vietnam as sources.Which brings me neatly to the second of my favourites - Madeline Miller's "Song of Achilles".

Of course this has won the Orange Prize for Fiction, but I was three-quarters through it when the prize was announced, so it did not influence my impressions of the book. Madeline Miller's version of the story of Achilles relies on building up an intimate picture of Achilles and Patroclus before the War at Troy actually starts. What I loved about this book from a writer's perspective was that the use of language was so lyrical. In a modern book it would be impossible to use terms such as 'the rosy gleam of his lip, the fevered green of his eyes' without it sounding ridiculous, yet in Miller's hands such language feels right. She has managed to make the book epic and Homerian. If the book has a weakness it is that the actual conflict (which in reality lasts ten years) takes a little too long to get going, but once it does the action is unputdownable. The early lyricism works just as well applied to battle, and the fact that some of the story is told from a dead man's point of view only increases its mystical effect.In this book we believe in the Gods, and in the terror of the Gods, and the power of human love.

Of course this has won the Orange Prize for Fiction, but I was three-quarters through it when the prize was announced, so it did not influence my impressions of the book. Madeline Miller's version of the story of Achilles relies on building up an intimate picture of Achilles and Patroclus before the War at Troy actually starts. What I loved about this book from a writer's perspective was that the use of language was so lyrical. In a modern book it would be impossible to use terms such as 'the rosy gleam of his lip, the fevered green of his eyes' without it sounding ridiculous, yet in Miller's hands such language feels right. She has managed to make the book epic and Homerian. If the book has a weakness it is that the actual conflict (which in reality lasts ten years) takes a little too long to get going, but once it does the action is unputdownable. The early lyricism works just as well applied to battle, and the fact that some of the story is told from a dead man's point of view only increases its mystical effect.In this book we believe in the Gods, and in the terror of the Gods, and the power of human love.The third of my favourites is "Honour and the Sword" by AL Berridge.

Of the three, this is the most swashbuckling of my choices. It is written as a series of interviews or memoirs from France during the time of the 30 years war and so includes a number of different voices put together by a fictional professor - Edward Morton. Sounds complicated? Perhaps, but it works brilliantly. Like a patchwork this method gradually builds up the picture of events from all the partisan points of view. Told in the first person present tense, some of it is written in very modern-sounding English but this has the effect of drawing the reader in. Mostly told from the point of view of Jacques the stable lad, and his erstwhile employer's son, an aristocrat called Andre de Roland, the slow development of the relationship between these two boys is what glues the book together. We watch them through the highs and lows of warfare, through heroism and despair as Andre de Roland seeks to avenge his parents death at the hands of the Spanish. This book has some excellent set-piece action scenes, with gripping sword fights, pistols and cannon.At the climax the action zips from person to person in a few lines - and this filmic technique like cutting from shot to shot, was breathtaking.

Three great pieces of historical fiction, I recommend them all.

You can read an interview with AL Berridge here about why she enjoys to write books more normally associated with a male readership.

Published on August 08, 2012 09:19

July 16, 2012

Tracing the Tudors - Jenny Barden Talks at the RNA Conference

Apologies to Jenny for the slightly blurry photograph, caused by my over excitement at seeing a real pistol! I was lucky enough to hear Jenny Barden talk about how she researched her new Tudor novel, Mistress of the Sea at the Romantic Novelists Association Conference in Penrith.

Jenny's book features Sir Francis Drake, and she told us how his illustrious career actually began with a disaster at San Juan de Ulua, and that he spent years seeking revenge, "Vengeance is always a good theme," she said.

In tracing the real events for the sinking of Drake's ship at sea she showed us how she traced the story from modern historians colourful accounts, back to the almost contemporary reports, and from there even further back to the original source. Often the amount of material can be overwhelming for a novelist embarking on this sort of research, but as Jenny said, "Fear not and relax. The only things that matter are the primary sources." She then explained that the original account from the ship had been burnt in a later fire and that the account had been reconstructed from the fragments. This was demonstrated by slides on the screen.

In tracing the real events for the sinking of Drake's ship at sea she showed us how she traced the story from modern historians colourful accounts, back to the almost contemporary reports, and from there even further back to the original source. Often the amount of material can be overwhelming for a novelist embarking on this sort of research, but as Jenny said, "Fear not and relax. The only things that matter are the primary sources." She then explained that the original account from the ship had been burnt in a later fire and that the account had been reconstructed from the fragments. This was demonstrated by slides on the screen.Original sources can disagree about events, depending on which side they are on, but Jenny said she enjoys building a story around the parts where sources disagree.

Visits to real places are a large part of Jenny's research, such as visiting tall-ships to see how cramped the spaces are on board ship, and visits to the islands where Drake sailed. In Mistress of the Sea the character of Drake is drawn by the opinions of those around him, and Jenny told us that the evidence showed he could be both compassionate and ruthless - for example he was outraged at the treatment of a black servant, but hung some franciscan friars in a dispute.

Jenny treated us to slides from her research visits, showing us the mule tracks and mangrove swamps where Drake would have walked. Her talk included showing us the pistol (see the picture) along with a ruff and a boned bodice of the time, which Henri Gyland dutifully put on - sorry, I forgot to take a picture. We were also treated to the waft of rosemary, the sound of Thomas Tallis's music, and were allowed to handle a 16th century key - all to give us a flavour of the past. These little touches - to feel, smell, hear the past, brought the period more vividly to life.

Questions from the floor enabled Jenny to talk more about her cross-dressing heroine, Ellyn, who stows away on Drake's ship the Swan. For those interested in more nautical tales of cross-dressing heroines you might like to check out Linda Collison's blog.

For an hour's talk Jenny managed to cram an awful lot in, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I've always been a sucker for the romance of the sea, so I'm really looking forward to the book, which will be published by Ebury Press in September 2012. More about Jenny Barden and her research process can be found here

More about the Romantic Novelist's Association here

Jenny is organising the Historical Novel Society Conference in London in September, more about that here.

Mistress of the Sea Plymouth 1570; Ellyn Cooksley fears for her elderly father's health when he declares his intention to sail with Drake on an expedition he has been backing. Already yearning for escape from the loveless marriage planned for her, Ellyn boards the expedition ship as a stowaway.

Also aboard the Swan is Will Doonan, Ellyn's charming but socially inferior neighbour. Will has courted Ellyn playfully without any real hope of winning her, but when she is discovered aboard ship, dressed in the garb of a cabin boy, he is furious.

To Will's mind, Drake's secret plot to attack the Spanish bullion supply in the New World is a means to the kind of wealth with which he might win a girl like Ellyn, but first and foremost it is an opportunity to avenge his brother Kit, taken hostage and likely tortured to death by the Spanish. For the sake of the mission he supports Drake's plan to abandon Ellyn and her father on an island in the Caribbean until their mission is completed. But will love prove more important than revenge or gold?

Published on July 16, 2012 05:06

July 10, 2012

The Eleanor Crosses - More Miniature Gothic Cathedrals

Waltham Cross by Greig 1803I was doing some research into market crosses for a novel I am working on, when I came across these - the so-called Eleanor Crosses, in their time probably the most elaborate wayside crosses in England.

Waltham Cross by Greig 1803I was doing some research into market crosses for a novel I am working on, when I came across these - the so-called Eleanor Crosses, in their time probably the most elaborate wayside crosses in England.In 1290 Queen Eleanor of Castile, to whom Edward I was devoted, died at Harby in Nottinghamshire. The king directed that crosses should be set up at every station at which the funeral procession would stop on the way to Westminster.

At Westminster she was buried at the feet of her father-in-law Henry III. Although some of her internal organs had been removed for burial at Lincoln during the enbalming process, her heart travelled with her and was buried in the abbey church at Blackfriars, London.

Geddington CrossThe processional route went through Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans,Waltham and London (St Paul's) before Charing village and Westminster - twelve stations in all. At every halt, the office for the dead was celebrated.

Geddington CrossThe processional route went through Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans,Waltham and London (St Paul's) before Charing village and Westminster - twelve stations in all. At every halt, the office for the dead was celebrated.Of the twelve crosses, only three remain today - the ones at Geddington, Northampton and Waltham. All are three-storied with tall spires and gothic tracery. On the second level is a a niche, occupied by a statue of Eleanor. Geddington Cross is triangular and almost forty feet high, whereas Northampton's Cross is octagonal.

Northampton Cross has four statues of Queen Eleanor, and this cross commemorates Eleanor's resting at nearby Delapre Abbey. King Edward I stayed at Northampton Castle nearby. The cross was begun in 1291 by John of Battle; he worked with William of Ireland to carve the statues; William was paid five marks (£3 6s. 8d. or £3.33 in old English money) per figure.

The cross is set on steps, which are not original. The cross is built in three tiers and originally had something on top - probably a cross.

Daniel Defoe refers to it where he reports on the Great Fire of Northampton in 1675:

"... a townsman being at Queen's Cross upon a hill on the south side of the town, about two miles off, saw the fire at one end of the town then newly begun, and that before he could get to the town it was burning at the remotest end, opposite where he first saw it."

Its bottom tier features open books. These probably included painted inscriptions of Eleanor's biography and of prayers for her soul to be said by viewers, which are now lost.

Cheapside Cross

Cheapside CrossAs for the vanished crosses, Cheapside Cross probably has the most colourful and telling history. It featured in the pageant held to celebrate the birth of Edward III, where a tent was set before it where anyone who passed might drink from a tun of wine. It was rebuilt in 1486 with the statues of the Queen replaced with statues of the Saints and the Virgin Mary, but in 1600 with the advent of anti-Catholic feeling, Mary was replaced by a statue of a half-naked Diana. Later in May 1643 John Evelyn records in his diary how he saw a furious Puritan mob destroy this cross altogether.

The Puritan destruction of the market crosses is what made me first interested in them, as they seem to be sites of significance to so many. My other article about Market Crosses can be found at www.englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com

Find out more:

Wikipedia article.

Thanks to www.webhistoryofengland.com

Nicolas Pevsner

Published on July 10, 2012 03:09

June 17, 2012

Writing Historical Fiction - The Power of Then and the Power of Now

All historical fiction readers understand the power of Then. The lure of an unknown time or place which is only unknown because it happened to take place before we were born. Unlike fantasy, this is an unfamiliar world which, if we took them back far enough, our own flesh and blood ancestors would be able to recognise. The small everyday details are what represent for me the power of Then. The type of flax cloth used for washing your face, the way a fire was lit with a tinder-box, the particular smell of tallow candles, the tickle of a feather in your hat. As a novelist my job is to place the reader in that time, but only recently have I come to understand that the job of doing that is really all about the power of Now.

The best plots spring straight out of Character. In other words, if my characters have strong enough motivations, particularly opposing ones, then the plot will naturally arise from their thoughts and actions. My most convincing writing arises when I inhabit the character so well that I lose track of time and am fully in the Now with that person going about their daily life. When I am trying to force the character to conform to a plot idea, historical event or action, then the writing becomes harder and less natural. Much of it is about listening to the character's voice and letting them speak.

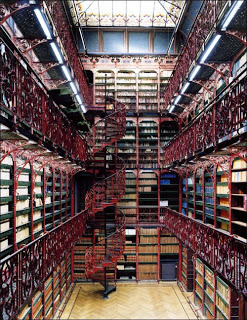

The British LibraryFor a historical novelist to find that voice might mean reading diaries of the time, listening to archive material or looking up dialect dictionaries - all things I did to try to find voices for my two country girls in The Gilded Lily. I also read plays by Aphra Behn and by Dryden. My previous characters had all been well-educated, spoke proper English and had broad philosophical and worldly horizons. Not so Ella and Sadie Appleby, my two working maids from a small isolated village in The Gilded Lily. Their vocabulary was of necessity smaller, many of their thoughts were conveyed by gestures - a shrug or a raise of the eyebrows. They had naive views about finding fame and fortune and their place in the world, but more complex views about justice and fairness and honesty.

The British LibraryFor a historical novelist to find that voice might mean reading diaries of the time, listening to archive material or looking up dialect dictionaries - all things I did to try to find voices for my two country girls in The Gilded Lily. I also read plays by Aphra Behn and by Dryden. My previous characters had all been well-educated, spoke proper English and had broad philosophical and worldly horizons. Not so Ella and Sadie Appleby, my two working maids from a small isolated village in The Gilded Lily. Their vocabulary was of necessity smaller, many of their thoughts were conveyed by gestures - a shrug or a raise of the eyebrows. They had naive views about finding fame and fortune and their place in the world, but more complex views about justice and fairness and honesty.And I wondered how this would change as they went on the run in the big city, whether they would learn new ways of speaking or new ideas, or yearn for new horizons. And of course they do - the city moulds them into someone different, but not just the city, the London characters they meet; the wigmaker, the pawnbroker, the astrologer.

Of course I live in the twenty first century so after my research the voices I heard in my head were not pure 17th century, but unique voices, a blend of 17th and 21st century expression. It is odd, but once I can hear my characters speak, then the characters become flesh and blood. Them surprising me is all part of the Power of Now. This is probably one of the reasons why I enjoy writing my books from several different contrasting viewpoints. I spend time in the company of each character, walk a few miles (or chapters) in his or her shoes.

For The Gilded Lily that meant becoming so familiar with my 17th century map of London that I could literally walk the city streets and turn left and right from Sadie and Ella's lodgings to the Pelican Coffee shop where Jay Whitgift, the handsome, but deadly, rogue did his business. As I went I practised walking as they might walk, looked up at the landmarks on the way.

For me, a narrative structure arises from the choices of my characters not from my own choices. How can that be, when I am both creator and created? This is the mystery and excitement of writing for me - the discovery of a great adventure, or that moment when I come back to myself and read it back, and see that the character is alive there on the page.The Power of Then, and the Power of Now.

THE GILDED LILY

Blurb:A novel of beauty and greed and surprising redemption, set in a London of atmospheric coffee houses, gilded mansions, and the shady pawnshops hidden from rich men’s view,

England, 1660. Ella Appleby believes she is destined for better things than slaving as a housemaid and dodging the blows of her violent father. When her employer dies suddenly, she seizes her chance - taking his valuables and fleeing the countryside with her sister for the golden prospects of London. But London may not be the promised land she expects. Work is hard to find, until Ella takes up with a dashing and dubious gentleman with ties to the London underworld. Meanwhile, her old employer's twin brother is in hot pursuit of the sisters, and soon a game of cat and mouse begins. As the net closes on the girls, danger looms from quite another unexpected horizon...

UK version out 13 Sept

US version out 27 Nov

Published on June 17, 2012 07:59

May 25, 2012

Books on The Pendle Witches - 400 years ago this year

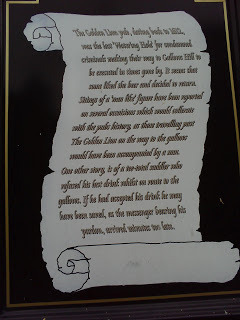

I parked in a car park opposite this pub, The Golden Lion, a few weeks ago on the way to the shops in Lancaster. As I passed it I remembered that this was the spot where the famous Pendle witches stopped for a last drink before being taken to Gallows Hill to be executed.

I parked in a car park opposite this pub, The Golden Lion, a few weeks ago on the way to the shops in Lancaster. As I passed it I remembered that this was the spot where the famous Pendle witches stopped for a last drink before being taken to Gallows Hill to be executed.I stopped to read the two plaques that are on the wall. The scroll gives the passer-by a little information, and the brass plaque is like a memorial and lists the names of those who were executed.

The year was 1612, exactly 400 years ago - a turbulent time in England's history, an era of religious persecution and superstition, under the reign of James I. At the foot of Pendle Hill, (later the inspiration to George Fox's Quaker Movement) nine villagers were accused of witchcraft following the deaths of several people in and around the Forest of Pendle, and they were later sent to trial at Lancaster Castle, where they were found guilty and then executed.

In both my books, The Lady's Slipper and The Gilded Lily, the shadow of witchcraft hangs over the women of Netherbarrow in Westmorland. In The Lady's Slipper Alice Ibbotson spends time in Lancaster Castle accused of witchcraft, just as the Pendle witches did, and in The Gilded Lily, Sadie Appleby is terrified of being accused of being a witch because of a birthmark on her face.

In the 17th century witchcraft was blamed for anything that could not be rationally explained, and the fact that James I was obsessed with finding witches did little to help the causes of those people, mostly women, who were accused.This extract showing how people were afraid of witchcraft is from the excellent Pendle Witches website, where there is a wealth of information on the women themselves and on the trials and executions. www.pendlewitches.co.uk

In the 17th century witchcraft was blamed for anything that could not be rationally explained, and the fact that James I was obsessed with finding witches did little to help the causes of those people, mostly women, who were accused.This extract showing how people were afraid of witchcraft is from the excellent Pendle Witches website, where there is a wealth of information on the women themselves and on the trials and executions. www.pendlewitches.co.uk "During the sixteenth century whole districts in some parts of Lancashire seemed contaminated with the presence of witches; men and beasts were supposed to languish under their charm, and the delusion which preyed alike on the learned and the vulgar did not allow any family to suppose that they were beyond the reach of the witch's power.

"During the sixteenth century whole districts in some parts of Lancashire seemed contaminated with the presence of witches; men and beasts were supposed to languish under their charm, and the delusion which preyed alike on the learned and the vulgar did not allow any family to suppose that they were beyond the reach of the witch's power.Was the family visited by sickness? It was believed to be the work of an invisible agency, which in secret wasted an image made in clay before the fire, or crumbled its various parts into dust.

Did the cattle sicken and die? The witch and the wizard were the authors of the calamity.Did the yeast refuse to ferment, either in the bread or the beer? It was the consequence of a 'bad wish'.

Did the butter refuse to come? The 'familiar' was in the churn.

Did the ship founder at sea? The gale or hurricane was blown by the lungless hag who had scarcely sufficient breath to cool her own pottage.

Did the river Ribble overflow its banks? The floods descended from the congregated sisterhood at Malkin Tower.

The blight of the season, which consigned the crops of the farmer to destruction, was the saliva of the enchantress, or distillations from the blear-eyed dame who flew by night over the field on mischief bent."

From History of Lancaster 1867 - Thomas Baines.

If you are interested in reading a novel about the Pendle witches then I can recommend Robert Neill's "Mist over Pendle". A nice review of it is over at What Kate's Reading.

Alternatively you might try "Daughters of the Witching Hill". You can read an interview with Mary Sharratt here about her process of writing.

Events to commemorate the Pendle Witches are happening throughout the year of 2012.

Events to commemorate the Pendle Witches are happening throughout the year of 2012.Those listed below are just a few. More information from Lancashire Witches 4000

"Sabbat" at the Dukes and Hoghton Tower

Witches Art Trails through the Forest of Bowland

`A Witch-Themed Murder Mystery` at Lancaster Castle

The Crucible by Arthur Miller at Lancaster Priory

Exhibition by Joe Hesketh – The Pendle Investigation, The Dukes

Lecture - Fair Trial or a Foul Bill - The Legal Significance of the Lancashire Witch Trials, Lancaster Priory

Service - In Solidarity with Victims of Persecution and Hate Crime, Lancaster Priory

Exhibition: Spellbound: Superstition, stories and the silver screen

Exhibition: A Wonderfull Discoverie: Lancashire Witches 1612-2012

Witches and Guy Fawkes Festival

Lancashire Witches Guided Walks around Lancaster City

Guided tours of Lancaster Castle.

A multimedia exhibition spanning time and place: “Witch Hunts, then and now”

h

h

Published on May 25, 2012 02:26

May 13, 2012

Spinning -The Roots of the Language of Writing

The language of story is peppered with references to the craft of spinning. We 'spin a yarn', and 'weave' a tale. The art of 'fabric'ation has very deep roots as one of the earliest forms of creation.

Spindles and spinning are also built into our mythology and folklore. Who can forget childhood tales of Rumplestiltskin or Sleeping Beauty? Plato says the axis of the universe is like the shaft of a spindle with the milky way as the whorl of wool in his Republic. In Greek mythology, Arachne challenges the goddess Minerva to a spinning and weaving contest and when she fails she is turned into a spider. Theseus follows a thread out of the Labyrinth. The three Fates, or Norns, spin, measure and cut the threads of life. The art of spinning is also identified with nature's spinner, the spider, and her web. Most of us writers use the web every day, without thinking much about its roots.

Spindles and spinning are also built into our mythology and folklore. Who can forget childhood tales of Rumplestiltskin or Sleeping Beauty? Plato says the axis of the universe is like the shaft of a spindle with the milky way as the whorl of wool in his Republic. In Greek mythology, Arachne challenges the goddess Minerva to a spinning and weaving contest and when she fails she is turned into a spider. Theseus follows a thread out of the Labyrinth. The three Fates, or Norns, spin, measure and cut the threads of life. The art of spinning is also identified with nature's spinner, the spider, and her web. Most of us writers use the web every day, without thinking much about its roots.

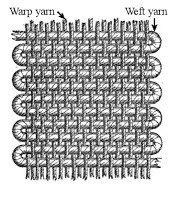

Before the spinning wheel, to make yarn, wool or plant fibre was twisted or spun by hand onto a stick or distaff and then wound onto a second stick or dropspindle. The act of turning the fibres bonded them together into a continuous thread. (Have you ever lost the thread of your story?) The female side of the family used to be called the "distaff" side of the family, the spinning of flax on a distaff being a female occupation. Warterhouse - La Fileuse

Warterhouse - La Fileuse

Thus, the dropspindle was 'the primary spinning tool used to spin all the threads for clothing and fabrics from Egyptian mummy wrappings to tapestries, and even the ropes and sails for ships, for almost 9000 years.' (http://kws.atlantia.sca.org/spinning.html)

In order to increase the spin, a whorl was added. The spindle, or rod, usually had a raised lip to hold the whorl. A wisp of prepared wool was twisted around the spindle, which was then spun and allowed to drop. They are amongst the most common Medieval finds, as the process of spinning was the most common occupation. The majority of whorls were made from stone or recycled pot but some were carved from wood or cast out of lead.

It was a natural evolution that spinners invented a way of speeding up the process - the spinning wheel. However, no one knows who invented the first one, but it probably originated in India between 500 and 1000 A.D. It is said that the hand spinners in India were able to spin almost half a million yards of yarn from a single pound of cotton (Hochberg), a fine quality that machines until recently were unable to do.

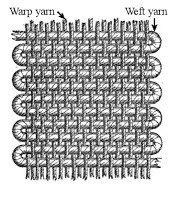

In the past spinning was mostly done by women.The resulting thread was woven by men onto looms to produce cloth. Hand loom weavers were men because of the strength needed to batten the cloth. Many superstitions abound about winding thread - for example fishermen's wives would not wind wool after sundown, for if they did they would soon be making their husband's winding sheets.(Dictionary of Superstitions).

In the past spinning was mostly done by women.The resulting thread was woven by men onto looms to produce cloth. Hand loom weavers were men because of the strength needed to batten the cloth. Many superstitions abound about winding thread - for example fishermen's wives would not wind wool after sundown, for if they did they would soon be making their husband's winding sheets.(Dictionary of Superstitions).

By the13th century spinning wheels appeared in Europe, putting an end to handspun thread, and in 1764, a British carpenter and weaver named James Hargreaves invented a hand-powered multiple spinning machine that was the first machine to improve upon the spinning wheel, ending the 'homespun' era for good and paving the way for modern machine produced goods.

Like Theseus, when writing I often feel I am following my own thread out of the maze of the plot, and after writing a book, I often think of editing as 'tidying up loose ends' and 'winding it up' neatly, both expressions which have probably originated in our lost spinning culture.

I can recommend this book, Women's Work, for those who want to know more about spinning and weaving in early history.

Want to try metal detecting to find some spindle whorls of your own?

http://www.colchestertreasurehunting.co.uk

Interesting You Tube video on spindle whorls http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6TGuypgXms

Spindles and spinning are also built into our mythology and folklore. Who can forget childhood tales of Rumplestiltskin or Sleeping Beauty? Plato says the axis of the universe is like the shaft of a spindle with the milky way as the whorl of wool in his Republic. In Greek mythology, Arachne challenges the goddess Minerva to a spinning and weaving contest and when she fails she is turned into a spider. Theseus follows a thread out of the Labyrinth. The three Fates, or Norns, spin, measure and cut the threads of life. The art of spinning is also identified with nature's spinner, the spider, and her web. Most of us writers use the web every day, without thinking much about its roots.

Spindles and spinning are also built into our mythology and folklore. Who can forget childhood tales of Rumplestiltskin or Sleeping Beauty? Plato says the axis of the universe is like the shaft of a spindle with the milky way as the whorl of wool in his Republic. In Greek mythology, Arachne challenges the goddess Minerva to a spinning and weaving contest and when she fails she is turned into a spider. Theseus follows a thread out of the Labyrinth. The three Fates, or Norns, spin, measure and cut the threads of life. The art of spinning is also identified with nature's spinner, the spider, and her web. Most of us writers use the web every day, without thinking much about its roots.Before the spinning wheel, to make yarn, wool or plant fibre was twisted or spun by hand onto a stick or distaff and then wound onto a second stick or dropspindle. The act of turning the fibres bonded them together into a continuous thread. (Have you ever lost the thread of your story?) The female side of the family used to be called the "distaff" side of the family, the spinning of flax on a distaff being a female occupation.

Warterhouse - La Fileuse

Warterhouse - La Fileuse

Thus, the dropspindle was 'the primary spinning tool used to spin all the threads for clothing and fabrics from Egyptian mummy wrappings to tapestries, and even the ropes and sails for ships, for almost 9000 years.' (http://kws.atlantia.sca.org/spinning.html)

In order to increase the spin, a whorl was added. The spindle, or rod, usually had a raised lip to hold the whorl. A wisp of prepared wool was twisted around the spindle, which was then spun and allowed to drop. They are amongst the most common Medieval finds, as the process of spinning was the most common occupation. The majority of whorls were made from stone or recycled pot but some were carved from wood or cast out of lead.

It was a natural evolution that spinners invented a way of speeding up the process - the spinning wheel. However, no one knows who invented the first one, but it probably originated in India between 500 and 1000 A.D. It is said that the hand spinners in India were able to spin almost half a million yards of yarn from a single pound of cotton (Hochberg), a fine quality that machines until recently were unable to do.

In the past spinning was mostly done by women.The resulting thread was woven by men onto looms to produce cloth. Hand loom weavers were men because of the strength needed to batten the cloth. Many superstitions abound about winding thread - for example fishermen's wives would not wind wool after sundown, for if they did they would soon be making their husband's winding sheets.(Dictionary of Superstitions).

In the past spinning was mostly done by women.The resulting thread was woven by men onto looms to produce cloth. Hand loom weavers were men because of the strength needed to batten the cloth. Many superstitions abound about winding thread - for example fishermen's wives would not wind wool after sundown, for if they did they would soon be making their husband's winding sheets.(Dictionary of Superstitions).By the13th century spinning wheels appeared in Europe, putting an end to handspun thread, and in 1764, a British carpenter and weaver named James Hargreaves invented a hand-powered multiple spinning machine that was the first machine to improve upon the spinning wheel, ending the 'homespun' era for good and paving the way for modern machine produced goods.

Like Theseus, when writing I often feel I am following my own thread out of the maze of the plot, and after writing a book, I often think of editing as 'tidying up loose ends' and 'winding it up' neatly, both expressions which have probably originated in our lost spinning culture.

I can recommend this book, Women's Work, for those who want to know more about spinning and weaving in early history.

Want to try metal detecting to find some spindle whorls of your own?

http://www.colchestertreasurehunting.co.uk

Interesting You Tube video on spindle whorls http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6TGuypgXms

Published on May 13, 2012 03:00

May 9, 2012

The History Room by Eliza Graham

I am delighted to welcome Eliza Graham today, to talk about her new novel, The History Room.

Hello Eliza, nice to have you here. Letchford, the private school in The History Room feels very genuine. Did you base the school on any particular place?

My children are at schools that sometimes play matches against various other schools in the South that look pretty amazing: acres of grounds, beautiful old buildings.Some of the pupils are pretty slick and amazing-looking, as well. It's easy to think that everything must be perfect. But of course, teenagers are teenagers wherever they are. I certainly had an idea of what the school looked like and it was fun building the world in my imagination.

I was interested in how you parallelled the effects of the past, particularly war, on two different generations. The repercussions of the injury to Meredith's husband and his rehabilitation must have been difficult to write. How did you go about tackling this subject?

We live quite near Wootton Bassett, to where repatriation of dead service personnel used to take place until recently. Every time I saw one of those big Globemasters overhead I'd feel a sense of dread and wonder who was waiting for a lost son or husband or father. I spent some time watching documentaries about how emergency medical transfers are operated between Camp Bastion and England to get the contemporary details right (I sincerely hope). Very sadly it seemed that almost every week there were details of casualties in the newspapers and it wasn't hard to learn about the work institutions such as Headley Court in Surrey, the rehabilitation centre, offer. It was tragic to read about the effects on relationships of injuries in warfare. But some of the stories of service personnel who'd survived appalling injuries were inspirational, too.

How did you research the Czechoslovakian wartime history? Were any of the events based on real incidents?

I read biographies to try and get a real sense of the tragic history of Czechoslovakia from 1938 and through the Soviet occupation and there were stories I came across that were similar to the one I tried to portray of young people deciding they couldn't bear to stay on in their own country once the Soviets smashed the Prague Spring. The escape stories were quite gripping in many cases. It must have such a hard decision to make: to leave your home or stay on.

Emily is a very dark character and pivotal to the plot. Please give us an insight into how her character developed.

Although she is dark she was actually really interesting to write, which sounds awful. But most of the other characters are more or less decent people, or aspiring to be so. So writing about someone who has no scruples was rather a release. I wanted to play a rather unpleasant stunt involving a very lifelike 'Reborn' doll and I needed someone who could do unpleasant things and was exploitative, preying on younger girls.

On a more serious note, I have read quite a lot about adolescent girls who cut themselves. I found it hard to understand at first but the more I read about it the more I wanted to know. So Emily was quite intriguing for me and I enjoyed writing her parts of the novel.

Thanks very much, Eliza.

Check out Eliza's other novels, Playing with the Moon, Restitution, and Jubilee

Review of The History Room

This is a novel where nearly everyone has a secret past, and their past impacts on the present to create a plot that gradually unfolds for the reader. The plot begins with a prank at a private school, which shocks the pupils and staff. In trying to find the culprit, Meredith Cordingley, a teacher at the school, must delve into the motives of her pupils and into her family's past. In doing so she discovers her father, the headmaster, is not the man she thought he was, and that the repercussions of war still haunt him. Not only must she contend with family secrets, but Emily, a teaching assistant at the school has an axe to grind, and will stop at nothing to get revenge for events of the past. Chilling and mysterious, this is a book I can highly recommend.

Published on May 09, 2012 10:45

I am delighted to welcome Eliza Graham today, to ta...

I am delighted to welcome Eliza Graham today, to talk about her new novel, The History Room.

Hello Eliza, nice to have you here. Letchford, the private school in The History Room feels very genuine. Did you base the school on any particular place?

My children are at schools that sometimes play matches against various other schools in the South that look pretty amazing: acres of grounds, beautiful old buildings.Some of the pupils are pretty slick and amazing-looking, as well. It's easy to think that everything must be perfect. But of course, teenagers are teenagers wherever they are. I certainly had an idea of what the school looked like and it was fun building the world in my imagination.

I was interested in how you parallelled the effects of the past, particularly war, on two different generations. The repercussions of the injury to Meredith's husband and his rehabilitation must have been difficult to write. How did you go about tackling this subject?

We live quite near Wootton Bassett, to where repatriation of dead service personnel used to take place until recently. Every time I saw one of those big Globemasters overhead I'd feel a sense of dread and wonder who was waiting for a lost son or husband or father. I spent some time watching documentaries about how emergency medical transfers are operated between Camp Bastion and England to get the contemporary details right (I sincerely hope). Very sadly it seemed that almost every week there were details of casualties in the newspapers and it wasn't hard to learn about the work institutions such as Headley Court in Surrey, the rehabilitation centre, offer. It was tragic to read about the effects on relationships of injuries in warfare. But some of the stories of service personnel who'd survived appalling injuries were inspirational, too.

How did you research the Czechoslovakian wartime history? Were any of the events based on real incidents?

I read biographies to try and get a real sense of the tragic history of Czechoslovakia from 1938 and through the Soviet occupation and there were stories I came across that were similar to the one I tried to portray of young people deciding they couldn't bear to stay on in their own country once the Soviets smashed the Prague Spring. The escape stories were quite gripping in many cases. It must have such a hard decision to make: to leave your home or stay on.

Emily is a very dark character and pivotal to the plot. Please give us an insight into how her character developed.

Although she is dark she was actually really interesting to write, which sounds awful. But most of the other characters are more or less decent people, or aspiring to be so. So writing about someone who has no scruples was rather a release. I wanted to play a rather unpleasant stunt involving a very lifelike 'Reborn' doll and I needed someone who could do unpleasant things and was exploitative, preying on younger girls.

On a more serious note, I have read quite a lot about adolescent girls who cut themselves. I found it hard to understand at first but the more I read about it the more I wanted to know. So Emily was quite intriguing for me and I enjoyed writing her parts of the novel.

Thanks very much, Eliza.

Check out Eliza's other novels, Playing with the Moon, Restitution, and Jubilee

Review of The History Room

This is a novel where nearly everyone has a secret past, and their past impacts on the present to create a plot that gradually unfolds for the reader. The plot begins with a prank at a private school, which shocks the pupils and staff. In trying to find the culprit, Meredith Cordingley, a teacher at the school, must delve into the motives of her pupils and into her family's past. In doing so she discovers her father, the headmaster, is not the man she thought he was, and that the repercussions of war still haunt him. Not only must she contend with family secrets, but Emily, a teaching assistant at the school has an axe to grind, and will stop at nothing to get revenge for events of the past. Chilling and mysterious, this is a book I can highly recommend.

Published on May 09, 2012 10:45