Nerine Dorman's Blog, page 48

November 3, 2015

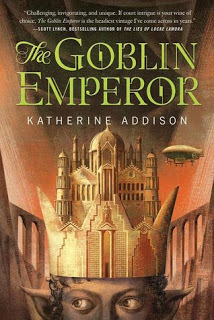

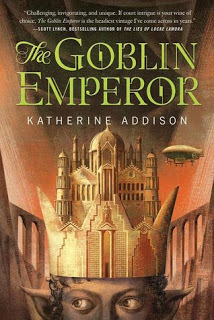

The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison #fantasy #review

Title:

The Goblin Emperor

Author: Katherine Addison

Publisher: Tor Books, 2014

Every once in a while, a fantasy novel comes around that doesn’t follow the trends that one almost comes to expect of the genre. If you’re the type who’s looking for sword and sorcery, flaming dragons and epic quests involving objects of power, this is not your novel. If, however, you’re looking for a slow-moving, gradually unfolding tale about an uncomplicated young man who finds himself quite suddenly thrust into the predicament of becoming an emperor, Maia’s story might just well be what you’re looking for.

Every once in a while, a fantasy novel comes around that doesn’t follow the trends that one almost comes to expect of the genre. If you’re the type who’s looking for sword and sorcery, flaming dragons and epic quests involving objects of power, this is not your novel. If, however, you’re looking for a slow-moving, gradually unfolding tale about an uncomplicated young man who finds himself quite suddenly thrust into the predicament of becoming an emperor, Maia’s story might just well be what you’re looking for.

Maia is the unwanted result of the marriage between the the Goblin princess Chenelo and the emperor of the Elflands. What was supposed to be a political marriage was never intended to produce an heir, let alone a halfbreed, and Maia has spent most of his childhood growing up in an isolate estate with only a relative to care for him (and not very well at that). When the emperor and his heirs die in freak airship accident, Maia is thrust from anonymity onto the emperor’s throne, as he is eldest heir.

Court politics, as he soon discovers, can be deadly, and not everyone is pleased that a half-Goblin is seated on the throne. What also counts against him is his complete naïveté when it comes to intrigue and yet, this very same weakness also proves to be his greatest strength while he establishes his rule. What is clear from the outset is that Maia is a good person. His honesty, his almost-painful lack of guile, elicited a need for me to see him succeed in the snake pit of the imperial court.

There are moments when his social ineptitude made me cringe, but by equal measure watching him grow into his role was ultimately rewarding, even if most of the action – this is partly a murder mystery – takes place offscreen, so to speak. Such action, as it occurs, is brief, and focus is rather placed on the subtle, interpersonal relations between the characters.

This is not a fast-moving novel by any measure. Katherine Addison’s prose is detailed and textured, and at times the array of names for people and places is bewildering (and possibly intentionally so, to create a sense of disorientation that Maia might feel at his situation). Yet the story is compelling, down to the last chapter, to be savoured for the rich world building and the slow weave of power play. The Goblin Emperor’s awarding of the 2015 Locus Award for “Best Fantasy Novel” is well deserved.

Author: Katherine Addison

Publisher: Tor Books, 2014

Every once in a while, a fantasy novel comes around that doesn’t follow the trends that one almost comes to expect of the genre. If you’re the type who’s looking for sword and sorcery, flaming dragons and epic quests involving objects of power, this is not your novel. If, however, you’re looking for a slow-moving, gradually unfolding tale about an uncomplicated young man who finds himself quite suddenly thrust into the predicament of becoming an emperor, Maia’s story might just well be what you’re looking for.

Every once in a while, a fantasy novel comes around that doesn’t follow the trends that one almost comes to expect of the genre. If you’re the type who’s looking for sword and sorcery, flaming dragons and epic quests involving objects of power, this is not your novel. If, however, you’re looking for a slow-moving, gradually unfolding tale about an uncomplicated young man who finds himself quite suddenly thrust into the predicament of becoming an emperor, Maia’s story might just well be what you’re looking for.Maia is the unwanted result of the marriage between the the Goblin princess Chenelo and the emperor of the Elflands. What was supposed to be a political marriage was never intended to produce an heir, let alone a halfbreed, and Maia has spent most of his childhood growing up in an isolate estate with only a relative to care for him (and not very well at that). When the emperor and his heirs die in freak airship accident, Maia is thrust from anonymity onto the emperor’s throne, as he is eldest heir.

Court politics, as he soon discovers, can be deadly, and not everyone is pleased that a half-Goblin is seated on the throne. What also counts against him is his complete naïveté when it comes to intrigue and yet, this very same weakness also proves to be his greatest strength while he establishes his rule. What is clear from the outset is that Maia is a good person. His honesty, his almost-painful lack of guile, elicited a need for me to see him succeed in the snake pit of the imperial court.

There are moments when his social ineptitude made me cringe, but by equal measure watching him grow into his role was ultimately rewarding, even if most of the action – this is partly a murder mystery – takes place offscreen, so to speak. Such action, as it occurs, is brief, and focus is rather placed on the subtle, interpersonal relations between the characters.

This is not a fast-moving novel by any measure. Katherine Addison’s prose is detailed and textured, and at times the array of names for people and places is bewildering (and possibly intentionally so, to create a sense of disorientation that Maia might feel at his situation). Yet the story is compelling, down to the last chapter, to be savoured for the rich world building and the slow weave of power play. The Goblin Emperor’s awarding of the 2015 Locus Award for “Best Fantasy Novel” is well deserved.

Published on November 03, 2015 11:58

October 28, 2015

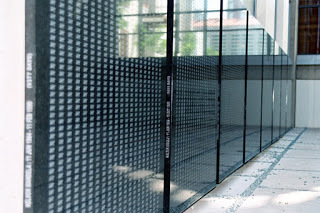

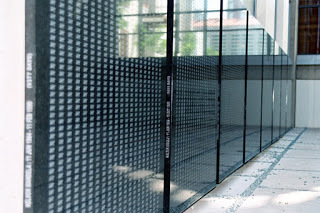

Thoughts on Prison Hacks/Prison Sentence by Willem Boshoff #art

For what it's worth, here's what I've written for my visual literacy module at varsity with regard to South African artist Willem Boshoff's Prison Hacks/Prison Sentence...

Picture: http://www.willemboshoff.com/document... a conceptual artist, Willem Boshoff challenges his viewers to consider the interplay of words, textures and visual elements, and in the case of Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences (2006, installation of black Zimbabwe granite slabs; Constitutional Court, Johannesburg) it’s important to take into consideration not only the name of the work and its execution, but the materials used and the location in which the work is installed, as all have bearing on the ultimate meaning and, consequently, the choice of name. It can also be argued that the decision to change the name of the work is also part of the overall presentation of the installation and the understanding that one can gain from discussion of this discourse.

Picture: http://www.willemboshoff.com/document... a conceptual artist, Willem Boshoff challenges his viewers to consider the interplay of words, textures and visual elements, and in the case of Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences (2006, installation of black Zimbabwe granite slabs; Constitutional Court, Johannesburg) it’s important to take into consideration not only the name of the work and its execution, but the materials used and the location in which the work is installed, as all have bearing on the ultimate meaning and, consequently, the choice of name. It can also be argued that the decision to change the name of the work is also part of the overall presentation of the installation and the understanding that one can gain from discussion of this discourse.

In considering Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences, attention should be paid to the materials used in the installation. Boshoff’s choice of black granite – a type of material used often for headstones in cemeteries – is not arbitrary, when he says: “I chose the black granite as it is the material of a graveyard. It is also the material used to build memorials.” (Boshoff 2012) Stone lends permanence; it is a lasting reminder that endures after brick has crumbled and wood has rotted. The use of granite and the reference to headstones draws viewers’ thoughts to other associations, such as death, and the memorialisation of lives that have passed. The location of the installation also has significance, in that it is situated on the premises of the Constitutional Court, the work therefore suggestive as memorial to the injustices of the past.

The granite slabs themselves have been polished to a high sheen and engraved with the kinds of marks used by prisoners to denote the passing of time – especially in an environment where an inmate has limited or no contact with the outside world. Boshoff states: “Each prisoner counts the days of his or her sentence already served by scoring a vertical hack through each day. After six days a diagonal is scored across the verticals to close a week of days. This is done on a wall, in a private place, perhaps in a cell or toilet.” (Boshoff 2012) This bears a direct correlation to the original title, Prison Hacks. To hack something suggests a crude movement, to cut, to carve, but connotations of the word also suggests the activity of someone who isn’t doing a particular good job of something (for instance, a bad writer is sometimes referred to as a hack). Perhaps at a stretch, the word “hack” can also relate to an activity of someone accessing information off a computer system without permission. According to Boshoff (Boshoff 2012) he preferred Prison Hacks “because a hack is a term for a person hired to do dull routine work, but also means a line that you draw through something”, with each ‘hack’ representing a day of the prisoner’s sentence.

Wordplay is an important element of Boshoff’s art, with many of his works featuring typographical elements: “Boshoff often refers to the etymological link between the words ‘text’, ‘texture’ and ‘textile’, which can all be traced to the Latin texere … textured surfaces often suggest that they can be read, with the eye or the hand.” (Vladislavic 2015, p. 28) which encourage a sense of engagement between the viewer and work that transcends a passive audience. Initially, Boshoff created three slabs covered in hacks, denoting the time served by Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada, however he was later commissioned to create the full complement of panels, and during that time Boshoff fell upon on a name change for the work. The wordplay associated with “sentences” can be read in two ways. The most obvious connection would be to the time periods indicated in the work, the actual prison sentence served by each of the men. The secondary meaning refers to the spirit of Boshoff’s work, that results in a dialogue between artist, work, and viewer – a dialogue, a conversation – a sentence. (Vladislavic 2015, p. 28)

This fluidity of meaning elicited by Boshoff’s work engages the senses. The work is tactile, and as the name change suggests, the work has been open to dialogue during the process of its creation. The name change can be viewed as a refinement, of taking the rough, unfinished work and completing it to initiate a conversation as opposed to the initial marks that were put down, suggestive of a finality, resignation. A sentence invites discussion, takes the “hacks” further and leads the viewer to make conclusions.

Bibliography:

Vladislavic, I. 2015. Willem Boshoff. Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing. Pages 26-32)

Willem Boshoff Artist 2012, Prison Sentences, Boshoff, W. Available from: < http://www.willemboshoff.com/document.... [16 August 2015].

Picture: http://www.willemboshoff.com/document... a conceptual artist, Willem Boshoff challenges his viewers to consider the interplay of words, textures and visual elements, and in the case of Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences (2006, installation of black Zimbabwe granite slabs; Constitutional Court, Johannesburg) it’s important to take into consideration not only the name of the work and its execution, but the materials used and the location in which the work is installed, as all have bearing on the ultimate meaning and, consequently, the choice of name. It can also be argued that the decision to change the name of the work is also part of the overall presentation of the installation and the understanding that one can gain from discussion of this discourse.

Picture: http://www.willemboshoff.com/document... a conceptual artist, Willem Boshoff challenges his viewers to consider the interplay of words, textures and visual elements, and in the case of Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences (2006, installation of black Zimbabwe granite slabs; Constitutional Court, Johannesburg) it’s important to take into consideration not only the name of the work and its execution, but the materials used and the location in which the work is installed, as all have bearing on the ultimate meaning and, consequently, the choice of name. It can also be argued that the decision to change the name of the work is also part of the overall presentation of the installation and the understanding that one can gain from discussion of this discourse.In considering Prison Hacks/Prison Sentences, attention should be paid to the materials used in the installation. Boshoff’s choice of black granite – a type of material used often for headstones in cemeteries – is not arbitrary, when he says: “I chose the black granite as it is the material of a graveyard. It is also the material used to build memorials.” (Boshoff 2012) Stone lends permanence; it is a lasting reminder that endures after brick has crumbled and wood has rotted. The use of granite and the reference to headstones draws viewers’ thoughts to other associations, such as death, and the memorialisation of lives that have passed. The location of the installation also has significance, in that it is situated on the premises of the Constitutional Court, the work therefore suggestive as memorial to the injustices of the past.

The granite slabs themselves have been polished to a high sheen and engraved with the kinds of marks used by prisoners to denote the passing of time – especially in an environment where an inmate has limited or no contact with the outside world. Boshoff states: “Each prisoner counts the days of his or her sentence already served by scoring a vertical hack through each day. After six days a diagonal is scored across the verticals to close a week of days. This is done on a wall, in a private place, perhaps in a cell or toilet.” (Boshoff 2012) This bears a direct correlation to the original title, Prison Hacks. To hack something suggests a crude movement, to cut, to carve, but connotations of the word also suggests the activity of someone who isn’t doing a particular good job of something (for instance, a bad writer is sometimes referred to as a hack). Perhaps at a stretch, the word “hack” can also relate to an activity of someone accessing information off a computer system without permission. According to Boshoff (Boshoff 2012) he preferred Prison Hacks “because a hack is a term for a person hired to do dull routine work, but also means a line that you draw through something”, with each ‘hack’ representing a day of the prisoner’s sentence.

Wordplay is an important element of Boshoff’s art, with many of his works featuring typographical elements: “Boshoff often refers to the etymological link between the words ‘text’, ‘texture’ and ‘textile’, which can all be traced to the Latin texere … textured surfaces often suggest that they can be read, with the eye or the hand.” (Vladislavic 2015, p. 28) which encourage a sense of engagement between the viewer and work that transcends a passive audience. Initially, Boshoff created three slabs covered in hacks, denoting the time served by Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada, however he was later commissioned to create the full complement of panels, and during that time Boshoff fell upon on a name change for the work. The wordplay associated with “sentences” can be read in two ways. The most obvious connection would be to the time periods indicated in the work, the actual prison sentence served by each of the men. The secondary meaning refers to the spirit of Boshoff’s work, that results in a dialogue between artist, work, and viewer – a dialogue, a conversation – a sentence. (Vladislavic 2015, p. 28)

This fluidity of meaning elicited by Boshoff’s work engages the senses. The work is tactile, and as the name change suggests, the work has been open to dialogue during the process of its creation. The name change can be viewed as a refinement, of taking the rough, unfinished work and completing it to initiate a conversation as opposed to the initial marks that were put down, suggestive of a finality, resignation. A sentence invites discussion, takes the “hacks” further and leads the viewer to make conclusions.

Bibliography:

Vladislavic, I. 2015. Willem Boshoff. Johannesburg: David Krut Publishing. Pages 26-32)

Willem Boshoff Artist 2012, Prison Sentences, Boshoff, W. Available from: < http://www.willemboshoff.com/document.... [16 August 2015].

Published on October 28, 2015 22:44

October 26, 2015

The Butcher Boys

Here's an idea of what I've been studying this year. This is one of the questions from my Visual Literacy module at varsity. (Also, my lecturer for some bizarre reason did NOT like me comparing these chaps to Frankenstein's monster, but I'll stand by my opinion on the matter.)

Picture: Wiki CommonsUpon first sight, the ominous figures of Jane Alexander’s The Butcher Boys (c. 1985/86. Mixed media, size unknown. Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town) strikes casual viewers with the vision of diabolical monsters lurking upon an ordinary wooden bench; however a closer view of the trio suggests that these so-called perpetrators of apartheid may also be considered victims of the very system they are proposed to uphold.

Picture: Wiki CommonsUpon first sight, the ominous figures of Jane Alexander’s The Butcher Boys (c. 1985/86. Mixed media, size unknown. Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town) strikes casual viewers with the vision of diabolical monsters lurking upon an ordinary wooden bench; however a closer view of the trio suggests that these so-called perpetrators of apartheid may also be considered victims of the very system they are proposed to uphold.

Alexander’s The Butcher Boys presents viewers with an undeniable, arresting focal point, especially considering where they have been placed in the Iziko Museums National Gallery – on their bench prominently positioned in the entrance hall, which makes them one of the first works that confronts visitors. A close examination of the sculpture reveals the figures’ lifelike poses and great attention to realism that has imbued the figures with physical menace. They are life sized and present an ominous blend of human and animal that immediately draws the eye and elicits a visceral response, much in the same way that bystanders feel compelled to stare at the scene of an accident. As passive bystanders, viewers are placed in a situation where they are confronted by a work that elicits a range of responses that are open to interpretation.

If anything, a viewer’s possible initial response of revulsion and macabre fascination, may lead to the sense that these entities pose a very real threat thanks to their powerful, well-defined musculature and positioning that give semblance to the potential of sudden movement made frightening by the unholy addition of horns. Their eyes, too, set them apart – dark and liquid, like that of an animal, possibly unthinking, fearful and feral. Their sickly, clay-like complexion suggests a skin tone that is neither black nor white, but is neutral and possibly diseased, even. Darker blemishes on their necks and by their damaged spines are suggestive of weeping wounds that have not healed. The figures represent an anomaly – constructs that should not be, like Frankenstein’s monster, composite beings made up of the discarded parts of others. Through a process of dehumanisation, these once well-proportioned human individuals have become perverted effigies; their physical bodies have been twisted into a parody of mankind by their taking on of bestial qualities. This is summed up by John Peffer, who writes, “Through the graphic distortion of the body and its metamorphosis into a beast, artists posed trenchant questions about the relation of corporeal experience to ideas about animality, community, and the sacred.” (Peffer 2009, p. 71) Alexander’s The Butcher Boys, through the addition of animal horns, bestial eyes, removal of ears, emasculation of the genitalia, and muting of the mouths, in addition to mutilation of the spine and throat, are a discomforting blend of human and animal that cannot simply be ignored. The choice of incorporating animal horns into the sculpture not only suggests the bestial metamorphosis akin to the Minotaur in its ancient Cretan Labyrinth – the product of a transgression against nature and the gods – but considered in a largely Western (and Christian) context, is also suggestive of the diabolical.

Context is important when viewing The Butcher Boys, especially considering the circumstances in which it was initially released. As Peffer writes, “During 1985 a state of emergency was declared in South Africa in response to renewed outbreaks of violent resistance, and was renewed yearly until 1990. The police were again given wide-ranging powers for the forceful suppression of popular protest, including the detention and interrogation of suspects without trial. Over thirty thousand people were detained between 1986 and 1987. During this period, Jane Alexander produced a sculptural group, The Butcher Boys (1985-86).” (Peffer 2009, p. 75) This climate of fear meant that South Africans could not be outspoken about or stand against conditions within the country. The Boys are mute – Alexander has created them without functioning mouths; it was not possible for South Africans to speak out against the oppressive government at the time, without fear of reprisal. With their ears removed, The Butcher Boys are incapable of hearing, suggesting that they’d be unable to hear pleas for mercy. The fact that their throats have been tampered with indicates that their vocal chords may be affected, on top of them not having functioning mouths. Exposed, damaged spines may also suggest a “spinelessness” or cowardice – further indication of either an inability or incapacity to resist, to act. Much can be read into the choice of their poses as well. The figure on the left seems relaxed, indifferent almost, as if he is waiting, resigned to his state of being. The figure in the middle, and the one on the far right, both give the appearance of paying attention to events the one on the far left hasn’t noticed (or won’t) yet. The Boy in the centre is alert, watchful, yet it is the one on the far right that suggests that he is about to move. Whether this reaction will result in a fight-or-flight response, is not made explicit, and it can be suggested that this conclusion can be left to the discretion of the viewer. The figures’ realism adds to the suggestion that each Boy is poised on the cusp of movement.

Friedrich Nietzsche's aphorism 146, from Beyond Good and Evil, resonates strongly a possible conception of Jane Alexander's The Butcher Boys: “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into the abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” (Nietzsche 1990, p. 102) The process of creating a monster goes two ways; through becoming the perpetrator of a broken, repressive system, of people who are shaped into tools for a greater evil, whose worldview is narrowed to the point where the “truth” that they are fed is limited (as illustrated by the Boys’ limited senses) the Boys themselves are victims, damaged and lashing out in much the same way as the Greek Minotaur or Frankenstein’s monster – unable to feel empathy and enslaved to their bestial natures that are enforced on them by authority figures.

Primarily, the Boys evoke horror. As Bick states, “Alexander’s work activates the space of viewership with the psychic and visceral experience of horror that continues to haunt us as we turn away, but more importantly, her work is itself haunted by experiences of untold, traumatic, and often irretrievable histories, which on the one hand seem outside the ethics and even capacity of representation … and on the other, without reflective and critical attention, are in danger of becoming lost to the past.” (Bick 2010, p. 32) We confront the Boys in a public space, in a gallery, where they lurk as a visible reminder of our inconvenient, unspoken past. Now, thirty years after their creation, they “confront the public secret of apartheid head on, not only by ‘giving evidence’ which could not be admitted in public or by the (white) public to itself. (Peffer 2009, p. 77) The Butcher Boys offers viewers a solid reminder, one that is presented, and based on the perception of the manner in which they are seated, of an unhurried watchfulness; their physicality suggests that they’re not just going to go away; they’re here, waiting, immovable, implacable. They evoke a primal reaction, of fear, very human yet reduced to instinctual responses. They have come into being through the action of a repressive system, to induce terror at a primal level, not only to be scorned but to be viewed with pity, for having been damaged so that they are no longer equipped to function within society nor adapt to changing circumstances.

Cognisance must also be taken of how socio-cultural context changes through the passage of time. Over the years, the possible meanings and interpretations of The Butcher Boys may shift thanks to the cultural biases of viewers; those who were born after 1994 may perhaps not draw upon the same sense of outrage as those who were present during the 1980s, when apartheid’s stranglehold experienced its last, reflexive gasps. There are those who are adult now, for whom the realities of detention without trial and enforced national service are relegated to a few lines in reference books. We are no longer faced with a visceral sucker punch of the intense horror, and though The Butcher Boys are mute, they linger as sentinels to this past – lest we forget.

As to whether The Butcher Boys were either victims or perpetrators of the apartheid system this question cannot, therefore, be considered as an either/or kind of situation. The Butcher Boys are both. As individuals they have been stunted by the system that has used them as enforcers of violence. Therein, ultimately, lies the tragedy, that through their dehumanisation they have been turned into the very monster that one should fear. Their contorted, physical forms are a reflection of the underlying social trauma that South Africans have faced under the yoke of an oppressive regime. The Butcher Boys are a reminder of the bestial actions perpetrated against thousands of South Africans, that have turned the perpetrators into monsters; yet at the same time we cannot forget that these so-called monsters were once human too, twisted into objects to fear and pity as a result of their actions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bick, T. 2010. Horror histories: apartheid and the abject body in the work of Jane Alexander. African Arts. Winter: 30-41.

Nietzsche. F. 1990. Beyond Good and Evil. Penguin Group: London. Page 102

Peffer, J. C2009. Art and the end of apartheid. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. (Chapter 2: Becoming Animal. Pages 41-72).

Picture: Wiki CommonsUpon first sight, the ominous figures of Jane Alexander’s The Butcher Boys (c. 1985/86. Mixed media, size unknown. Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town) strikes casual viewers with the vision of diabolical monsters lurking upon an ordinary wooden bench; however a closer view of the trio suggests that these so-called perpetrators of apartheid may also be considered victims of the very system they are proposed to uphold.

Picture: Wiki CommonsUpon first sight, the ominous figures of Jane Alexander’s The Butcher Boys (c. 1985/86. Mixed media, size unknown. Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town) strikes casual viewers with the vision of diabolical monsters lurking upon an ordinary wooden bench; however a closer view of the trio suggests that these so-called perpetrators of apartheid may also be considered victims of the very system they are proposed to uphold.Alexander’s The Butcher Boys presents viewers with an undeniable, arresting focal point, especially considering where they have been placed in the Iziko Museums National Gallery – on their bench prominently positioned in the entrance hall, which makes them one of the first works that confronts visitors. A close examination of the sculpture reveals the figures’ lifelike poses and great attention to realism that has imbued the figures with physical menace. They are life sized and present an ominous blend of human and animal that immediately draws the eye and elicits a visceral response, much in the same way that bystanders feel compelled to stare at the scene of an accident. As passive bystanders, viewers are placed in a situation where they are confronted by a work that elicits a range of responses that are open to interpretation.

If anything, a viewer’s possible initial response of revulsion and macabre fascination, may lead to the sense that these entities pose a very real threat thanks to their powerful, well-defined musculature and positioning that give semblance to the potential of sudden movement made frightening by the unholy addition of horns. Their eyes, too, set them apart – dark and liquid, like that of an animal, possibly unthinking, fearful and feral. Their sickly, clay-like complexion suggests a skin tone that is neither black nor white, but is neutral and possibly diseased, even. Darker blemishes on their necks and by their damaged spines are suggestive of weeping wounds that have not healed. The figures represent an anomaly – constructs that should not be, like Frankenstein’s monster, composite beings made up of the discarded parts of others. Through a process of dehumanisation, these once well-proportioned human individuals have become perverted effigies; their physical bodies have been twisted into a parody of mankind by their taking on of bestial qualities. This is summed up by John Peffer, who writes, “Through the graphic distortion of the body and its metamorphosis into a beast, artists posed trenchant questions about the relation of corporeal experience to ideas about animality, community, and the sacred.” (Peffer 2009, p. 71) Alexander’s The Butcher Boys, through the addition of animal horns, bestial eyes, removal of ears, emasculation of the genitalia, and muting of the mouths, in addition to mutilation of the spine and throat, are a discomforting blend of human and animal that cannot simply be ignored. The choice of incorporating animal horns into the sculpture not only suggests the bestial metamorphosis akin to the Minotaur in its ancient Cretan Labyrinth – the product of a transgression against nature and the gods – but considered in a largely Western (and Christian) context, is also suggestive of the diabolical.

Context is important when viewing The Butcher Boys, especially considering the circumstances in which it was initially released. As Peffer writes, “During 1985 a state of emergency was declared in South Africa in response to renewed outbreaks of violent resistance, and was renewed yearly until 1990. The police were again given wide-ranging powers for the forceful suppression of popular protest, including the detention and interrogation of suspects without trial. Over thirty thousand people were detained between 1986 and 1987. During this period, Jane Alexander produced a sculptural group, The Butcher Boys (1985-86).” (Peffer 2009, p. 75) This climate of fear meant that South Africans could not be outspoken about or stand against conditions within the country. The Boys are mute – Alexander has created them without functioning mouths; it was not possible for South Africans to speak out against the oppressive government at the time, without fear of reprisal. With their ears removed, The Butcher Boys are incapable of hearing, suggesting that they’d be unable to hear pleas for mercy. The fact that their throats have been tampered with indicates that their vocal chords may be affected, on top of them not having functioning mouths. Exposed, damaged spines may also suggest a “spinelessness” or cowardice – further indication of either an inability or incapacity to resist, to act. Much can be read into the choice of their poses as well. The figure on the left seems relaxed, indifferent almost, as if he is waiting, resigned to his state of being. The figure in the middle, and the one on the far right, both give the appearance of paying attention to events the one on the far left hasn’t noticed (or won’t) yet. The Boy in the centre is alert, watchful, yet it is the one on the far right that suggests that he is about to move. Whether this reaction will result in a fight-or-flight response, is not made explicit, and it can be suggested that this conclusion can be left to the discretion of the viewer. The figures’ realism adds to the suggestion that each Boy is poised on the cusp of movement.

Friedrich Nietzsche's aphorism 146, from Beyond Good and Evil, resonates strongly a possible conception of Jane Alexander's The Butcher Boys: “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into the abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” (Nietzsche 1990, p. 102) The process of creating a monster goes two ways; through becoming the perpetrator of a broken, repressive system, of people who are shaped into tools for a greater evil, whose worldview is narrowed to the point where the “truth” that they are fed is limited (as illustrated by the Boys’ limited senses) the Boys themselves are victims, damaged and lashing out in much the same way as the Greek Minotaur or Frankenstein’s monster – unable to feel empathy and enslaved to their bestial natures that are enforced on them by authority figures.

Primarily, the Boys evoke horror. As Bick states, “Alexander’s work activates the space of viewership with the psychic and visceral experience of horror that continues to haunt us as we turn away, but more importantly, her work is itself haunted by experiences of untold, traumatic, and often irretrievable histories, which on the one hand seem outside the ethics and even capacity of representation … and on the other, without reflective and critical attention, are in danger of becoming lost to the past.” (Bick 2010, p. 32) We confront the Boys in a public space, in a gallery, where they lurk as a visible reminder of our inconvenient, unspoken past. Now, thirty years after their creation, they “confront the public secret of apartheid head on, not only by ‘giving evidence’ which could not be admitted in public or by the (white) public to itself. (Peffer 2009, p. 77) The Butcher Boys offers viewers a solid reminder, one that is presented, and based on the perception of the manner in which they are seated, of an unhurried watchfulness; their physicality suggests that they’re not just going to go away; they’re here, waiting, immovable, implacable. They evoke a primal reaction, of fear, very human yet reduced to instinctual responses. They have come into being through the action of a repressive system, to induce terror at a primal level, not only to be scorned but to be viewed with pity, for having been damaged so that they are no longer equipped to function within society nor adapt to changing circumstances.

Cognisance must also be taken of how socio-cultural context changes through the passage of time. Over the years, the possible meanings and interpretations of The Butcher Boys may shift thanks to the cultural biases of viewers; those who were born after 1994 may perhaps not draw upon the same sense of outrage as those who were present during the 1980s, when apartheid’s stranglehold experienced its last, reflexive gasps. There are those who are adult now, for whom the realities of detention without trial and enforced national service are relegated to a few lines in reference books. We are no longer faced with a visceral sucker punch of the intense horror, and though The Butcher Boys are mute, they linger as sentinels to this past – lest we forget.

As to whether The Butcher Boys were either victims or perpetrators of the apartheid system this question cannot, therefore, be considered as an either/or kind of situation. The Butcher Boys are both. As individuals they have been stunted by the system that has used them as enforcers of violence. Therein, ultimately, lies the tragedy, that through their dehumanisation they have been turned into the very monster that one should fear. Their contorted, physical forms are a reflection of the underlying social trauma that South Africans have faced under the yoke of an oppressive regime. The Butcher Boys are a reminder of the bestial actions perpetrated against thousands of South Africans, that have turned the perpetrators into monsters; yet at the same time we cannot forget that these so-called monsters were once human too, twisted into objects to fear and pity as a result of their actions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bick, T. 2010. Horror histories: apartheid and the abject body in the work of Jane Alexander. African Arts. Winter: 30-41.

Nietzsche. F. 1990. Beyond Good and Evil. Penguin Group: London. Page 102

Peffer, J. C2009. Art and the end of apartheid. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. (Chapter 2: Becoming Animal. Pages 41-72).

Published on October 26, 2015 22:30

October 8, 2015

The Elfish Gene by Mark Barrowcliffe #review #memoirs

Title:

The Elfish Gene: Dungeons, Dragons and Growing Up Strange

Author: Mark Barrowcliffe

Publisher: Soho Press, 2009

Warning: If you’re hoping this is a book extolling the virtues of fantasy roleplaying as a positive outlet for socially marginalised teens then WRONG. This is not the book you’re looking for. Step away while you still can and go read some fanfiction. What The Elfish Gene is, however, is Mark Barrowcliffe’s memoirs of growing up in Coventry during the 1970s, and how as a completely gauche, socially maladjusted teen he fled into the world of fantasy RPGs because he simply couldn’t cope with reality.

Warning: If you’re hoping this is a book extolling the virtues of fantasy roleplaying as a positive outlet for socially marginalised teens then WRONG. This is not the book you’re looking for. Step away while you still can and go read some fanfiction. What The Elfish Gene is, however, is Mark Barrowcliffe’s memoirs of growing up in Coventry during the 1970s, and how as a completely gauche, socially maladjusted teen he fled into the world of fantasy RPGs because he simply couldn’t cope with reality.

This is a tragic book. And it made me incredibly sad. Mark comes across as bitter about his past, possibly bitter about the fact that he was so lost in the games that he wasn’t functioning in society. These are not the types of memory I have of my own gaming days, and after finishing this book, I almost feel tainted. I ask myself, is this how I am with regard to the books, games and films I get excited about? To the exclusion of participating in the world at large?

Then again, I don’t recall the sheer, blithering nastiness of my fellow gamers that Mark does. Possibly, one can say that boys will be boys, but I’m an anomaly in that regard – a girl who likes her fantasy RPGs a little too much. Sure, I met a few like Mark at the few events that we had in Cape Town during the 1990s, but I avoided them. The rest of the folks were just incredibly fun to be around, all student types, and we had really good times.

What I got from The Elfish Gene is mostly Mark’s bitterness, suggestive of deep-rooted self-loathing, that he had to dig deep and bring up all that was ugly. And, yes, it’s easy to see how games like D&D can create festering little dick-measuring contests among folks, but FFS, there’s more it than what he states.

Yes, there are bits that are genuinely laugh-out-loud funny, like Mark’s Ninja escapades, but most of the time I felt I was laughing *at* him for being such a sad puppy, and I was really glad to be done with the book. Yes, also to the fact that Mark pokes sticks at valid issues with the social interaction with *some* gamers, but yikes… I needed to read something uplifting and joy-making after this. As a snapshot into a particular era, however, and the mentality of the people at the time, this book is fascinating, in the same way as one is sometimes compelled to rubberneck at the scene of a gruesome motor vehicle accident involving a drunk pedestrian, errant livestock and a lorry transporting manure.

Author: Mark Barrowcliffe

Publisher: Soho Press, 2009

Warning: If you’re hoping this is a book extolling the virtues of fantasy roleplaying as a positive outlet for socially marginalised teens then WRONG. This is not the book you’re looking for. Step away while you still can and go read some fanfiction. What The Elfish Gene is, however, is Mark Barrowcliffe’s memoirs of growing up in Coventry during the 1970s, and how as a completely gauche, socially maladjusted teen he fled into the world of fantasy RPGs because he simply couldn’t cope with reality.

Warning: If you’re hoping this is a book extolling the virtues of fantasy roleplaying as a positive outlet for socially marginalised teens then WRONG. This is not the book you’re looking for. Step away while you still can and go read some fanfiction. What The Elfish Gene is, however, is Mark Barrowcliffe’s memoirs of growing up in Coventry during the 1970s, and how as a completely gauche, socially maladjusted teen he fled into the world of fantasy RPGs because he simply couldn’t cope with reality.This is a tragic book. And it made me incredibly sad. Mark comes across as bitter about his past, possibly bitter about the fact that he was so lost in the games that he wasn’t functioning in society. These are not the types of memory I have of my own gaming days, and after finishing this book, I almost feel tainted. I ask myself, is this how I am with regard to the books, games and films I get excited about? To the exclusion of participating in the world at large?

Then again, I don’t recall the sheer, blithering nastiness of my fellow gamers that Mark does. Possibly, one can say that boys will be boys, but I’m an anomaly in that regard – a girl who likes her fantasy RPGs a little too much. Sure, I met a few like Mark at the few events that we had in Cape Town during the 1990s, but I avoided them. The rest of the folks were just incredibly fun to be around, all student types, and we had really good times.

What I got from The Elfish Gene is mostly Mark’s bitterness, suggestive of deep-rooted self-loathing, that he had to dig deep and bring up all that was ugly. And, yes, it’s easy to see how games like D&D can create festering little dick-measuring contests among folks, but FFS, there’s more it than what he states.

Yes, there are bits that are genuinely laugh-out-loud funny, like Mark’s Ninja escapades, but most of the time I felt I was laughing *at* him for being such a sad puppy, and I was really glad to be done with the book. Yes, also to the fact that Mark pokes sticks at valid issues with the social interaction with *some* gamers, but yikes… I needed to read something uplifting and joy-making after this. As a snapshot into a particular era, however, and the mentality of the people at the time, this book is fascinating, in the same way as one is sometimes compelled to rubberneck at the scene of a gruesome motor vehicle accident involving a drunk pedestrian, errant livestock and a lorry transporting manure.

Published on October 08, 2015 11:31

October 6, 2015

Author profile: Elizabeth Myrddin

Today's featured author is Elizabeth Myrddin, who's part of the Guns & Romances anthology which is available at Amazon, Kobo and Smashwords, among others.

Who are you?

I live and work in San Francisco. I write for fun, with an emphasis on mysteries, suspense, horror, and dark fantasy, but I’ll try anything three times.

I live and work in San Francisco. I write for fun, with an emphasis on mysteries, suspense, horror, and dark fantasy, but I’ll try anything three times.

Tell us more about your story and what you enjoyed about writing it.

Romance and erotica stories are not my cup of tea, but I did want to challenge myself, and to stretch my writing limits. After a few halting starts (and a searing sense of frustration that nagged at me to give up), I went with the tried-and-true method of “write what you know.” Inspiration harvested from my life experiences, the various people, situations, and environments helped shape the story. The trickster demon transference idea came from a random article I read on the internet. It was a lot of fun figuring out how to incorporate that detail into the story.

I worried about relegating the guns to mere set dressing instead of as featured components in the action. I’ve gone to gun shows in the past, and loved the vintage firearms and war memorabilia booths, and the gun show setting was the first thing that popped into my mind when I began the story. I’m glad I stuck with it. Once I decided to pepper "Not Just Another Daddy’s Girl" with non-traditional or unusual elements, I was finally able to focus on the progression and accompanying uncertainties of the romance buildup between Vic and Haddie (and the strangeness that occurred later). Before I knew it, the story became a joy to write. This surprised and pleased me. The best result of this story, aside from its acceptance into the Guns and Romances anthology, was discovering that I could write a “romance-based” storyline and like it.

Why do you think short fiction is important?

Short fiction offers a wide variety of tales, characters, voices, and scenarios for the reader to choose from and enjoy. Short fiction provides an endless array of entertainment or escapism. Apéritifs for the imagination.

What is your favourite short story?

How can I limit it to one? I’ll go with the one that affected me the deepest upon first reading it. I now have more of her work in my bookcases than any other author. The story is "Stained With Crimson" in The Book of the Damned by Tanith Lee. In that same volume are "Malice In Saffron and Empires Of Azure" – stories that also brought me to tears upon first read. For me, the impact of Tanith Lee’s writing is indelible and her works will forever be awe-inspiring.

Have you got upcoming projects you'd like to talk about?

I wrote a two-part mystery story and those books are available on Amazon. That project was a blast, and I learned that with enough focus and effort, I could actually finish something longer than a short story. Currently, I’m reading and exploring gothic suspense and working on a novella. When needing a break from the WIP, I work on short stories to submit willy nilly. Two stories are out for submission and the wait to hear a yay or nay is ongoing.

Who are you?

I live and work in San Francisco. I write for fun, with an emphasis on mysteries, suspense, horror, and dark fantasy, but I’ll try anything three times.

I live and work in San Francisco. I write for fun, with an emphasis on mysteries, suspense, horror, and dark fantasy, but I’ll try anything three times.Tell us more about your story and what you enjoyed about writing it.

Romance and erotica stories are not my cup of tea, but I did want to challenge myself, and to stretch my writing limits. After a few halting starts (and a searing sense of frustration that nagged at me to give up), I went with the tried-and-true method of “write what you know.” Inspiration harvested from my life experiences, the various people, situations, and environments helped shape the story. The trickster demon transference idea came from a random article I read on the internet. It was a lot of fun figuring out how to incorporate that detail into the story.

I worried about relegating the guns to mere set dressing instead of as featured components in the action. I’ve gone to gun shows in the past, and loved the vintage firearms and war memorabilia booths, and the gun show setting was the first thing that popped into my mind when I began the story. I’m glad I stuck with it. Once I decided to pepper "Not Just Another Daddy’s Girl" with non-traditional or unusual elements, I was finally able to focus on the progression and accompanying uncertainties of the romance buildup between Vic and Haddie (and the strangeness that occurred later). Before I knew it, the story became a joy to write. This surprised and pleased me. The best result of this story, aside from its acceptance into the Guns and Romances anthology, was discovering that I could write a “romance-based” storyline and like it.

Why do you think short fiction is important?

Short fiction offers a wide variety of tales, characters, voices, and scenarios for the reader to choose from and enjoy. Short fiction provides an endless array of entertainment or escapism. Apéritifs for the imagination.

What is your favourite short story?

How can I limit it to one? I’ll go with the one that affected me the deepest upon first reading it. I now have more of her work in my bookcases than any other author. The story is "Stained With Crimson" in The Book of the Damned by Tanith Lee. In that same volume are "Malice In Saffron and Empires Of Azure" – stories that also brought me to tears upon first read. For me, the impact of Tanith Lee’s writing is indelible and her works will forever be awe-inspiring.

Have you got upcoming projects you'd like to talk about?

I wrote a two-part mystery story and those books are available on Amazon. That project was a blast, and I learned that with enough focus and effort, I could actually finish something longer than a short story. Currently, I’m reading and exploring gothic suspense and working on a novella. When needing a break from the WIP, I work on short stories to submit willy nilly. Two stories are out for submission and the wait to hear a yay or nay is ongoing.

Published on October 06, 2015 12:10

September 30, 2015

bitter + sweet by Mietha Klaaste, Niël Stemmet #review #foodie

Title: bitter + sweet

Authors: Mietha Klaaste, Niël Stemmet

Publisher: Human & Rousseau, 2015

bitter + sweet, which also has an Afrikaans edition bitter + soet, is the kind of book that simply begs you to pick it up and take a closer look. Not only is it, exactly as it says, a cookbook filled with, as Niël Stemmet names as heritage food, but it also serves as a record of stories about Niël and Mietha Klaaste’s remembrances. Hence the “bitter” to counteract the “sweet” of many of the traditional dishes offered by South Africa’s coloured people.

bitter + sweet, which also has an Afrikaans edition bitter + soet, is the kind of book that simply begs you to pick it up and take a closer look. Not only is it, exactly as it says, a cookbook filled with, as Niël Stemmet names as heritage food, but it also serves as a record of stories about Niël and Mietha Klaaste’s remembrances. Hence the “bitter” to counteract the “sweet” of many of the traditional dishes offered by South Africa’s coloured people.

Mietha was born on a farm in the Robertson district and cared for him from the day he was born until the time that his family left when he was 15. In many ways, it can be seen, she played a bigger role as nurturer in his life than his own mother, and in this book he has had the opportunity, as he says, to “put her memories into words, remember the recipes”.

We are tactile beings, and as we grow older, we also fall prey to nostalgia; therefore the tastes of our childhood become precious. For those of us who grew up during a certain era or among particular people, recipes such as baked sago pudding, dried beans with sugar and vinegar, tomato bredie, yellow rice with raisins or old-fashioned pancakes may conjure up visions of lazy Sunday lunches with relatives or even the church bazaars from childhood, with the taste of cinnamon sugar and lemon juice lingering on your lips.

Mietha takes readers on a culinary journey through the past, offering a glimpse into the historical context in which meals were served. Not only that, but we are offered a perspective of what life was like for coloured people living out in the countryside at time; and it’s important that her voice is heard, to lay down visceral memories of an era in which we experienced great social injustice.

Yet for all the sadness, there is the love – and there is no denying the special bond between Mietha and Niël, as heart-rending as some of the events were that they endured. For all the beautiful stories, there are the darker, painful ones, sustained by the meals.

Mention must also be made of Adriaan Oosthuizen’s photography and the food styling, which together present minimalistic yet lovingly vintage images of a number of the recipes – which work well with the bold, colourful layout.

Even for those who’re not great cooks but have an interest in culture, this is a must-read; for those whose passion involves cooking, you can’t go wrong – there are some timeless recipes included. bitter + sweet will linger in my mind for a long time, for the sadness and its joy.

Authors: Mietha Klaaste, Niël Stemmet

Publisher: Human & Rousseau, 2015

bitter + sweet, which also has an Afrikaans edition bitter + soet, is the kind of book that simply begs you to pick it up and take a closer look. Not only is it, exactly as it says, a cookbook filled with, as Niël Stemmet names as heritage food, but it also serves as a record of stories about Niël and Mietha Klaaste’s remembrances. Hence the “bitter” to counteract the “sweet” of many of the traditional dishes offered by South Africa’s coloured people.

bitter + sweet, which also has an Afrikaans edition bitter + soet, is the kind of book that simply begs you to pick it up and take a closer look. Not only is it, exactly as it says, a cookbook filled with, as Niël Stemmet names as heritage food, but it also serves as a record of stories about Niël and Mietha Klaaste’s remembrances. Hence the “bitter” to counteract the “sweet” of many of the traditional dishes offered by South Africa’s coloured people.Mietha was born on a farm in the Robertson district and cared for him from the day he was born until the time that his family left when he was 15. In many ways, it can be seen, she played a bigger role as nurturer in his life than his own mother, and in this book he has had the opportunity, as he says, to “put her memories into words, remember the recipes”.

We are tactile beings, and as we grow older, we also fall prey to nostalgia; therefore the tastes of our childhood become precious. For those of us who grew up during a certain era or among particular people, recipes such as baked sago pudding, dried beans with sugar and vinegar, tomato bredie, yellow rice with raisins or old-fashioned pancakes may conjure up visions of lazy Sunday lunches with relatives or even the church bazaars from childhood, with the taste of cinnamon sugar and lemon juice lingering on your lips.

Mietha takes readers on a culinary journey through the past, offering a glimpse into the historical context in which meals were served. Not only that, but we are offered a perspective of what life was like for coloured people living out in the countryside at time; and it’s important that her voice is heard, to lay down visceral memories of an era in which we experienced great social injustice.

Yet for all the sadness, there is the love – and there is no denying the special bond between Mietha and Niël, as heart-rending as some of the events were that they endured. For all the beautiful stories, there are the darker, painful ones, sustained by the meals.

Mention must also be made of Adriaan Oosthuizen’s photography and the food styling, which together present minimalistic yet lovingly vintage images of a number of the recipes – which work well with the bold, colourful layout.

Even for those who’re not great cooks but have an interest in culture, this is a must-read; for those whose passion involves cooking, you can’t go wrong – there are some timeless recipes included. bitter + sweet will linger in my mind for a long time, for the sadness and its joy.

Published on September 30, 2015 12:03

September 29, 2015

Kingdom by Robyn Young #reviews #historical

Title:

Kingdom (The Insurrection Trilogy #3)

Author: Robyn Young

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton, 2014

If there’s one thing that author Robyn Young has excelled at with Kingdom, it’s the sheer attention to detail that many writers of historical fiction would do well to learn from. If ever you wish to be dropped into the muck and mire, and pure visceral experience of what life was like in years gone by, complete with sights, sounds, smells and all the attendant discomfort, Young achieves this in bucketloads.

If there’s one thing that author Robyn Young has excelled at with Kingdom, it’s the sheer attention to detail that many writers of historical fiction would do well to learn from. If ever you wish to be dropped into the muck and mire, and pure visceral experience of what life was like in years gone by, complete with sights, sounds, smells and all the attendant discomfort, Young achieves this in bucketloads.

In Kingdom, she ties together the final conflicts faced by Scotland’s King Robert Bruce, as he struggles against the English King Edward, and strives for a united, independent Scotland. Consequently, it’s easy to see where so much of the enmity between the two nations stems from, and both sides have blood on their hands and treachery staining their souls.

Edward’s hunt for Robert drives the Scottish king close to his end so many times, it’s almost impossible to believe that Robert’s tenacity resulted in his survival. That he was able to bounce back at all is a miracle. Yet so history would lead us to believe, and this epic is brought to life in Kingdom in a way that is gripping.

That being said, the very qualities of this story that deliver such a vivid tableau of a Robert’s struggles are the very things that hamper it. I found it difficult to relate to any of the large cast of characters precisely because Young was attempting to paint in such broad strokes. Her voice is very much omniscient, which kept me from immersing in the story nor feeling any particular emotional investment.

People die, horribly and often in most gruesome fashions, yet I couldn’t bring myself to care for their deaths. In Young’s intention to capture the bigger picture, she has, unfortunately had to sacrifice the engagement with narrative arcs in favour of interpretation of the greater events. That being said, this is still a thrilling read with some interesting assessments that will no doubt give history buffs much to consider. Those who’re not completely au fait with the history of the British Isles and who haven’t read the preceding two books may, however, find all the name-dropping and references to past events bewildering, though savvy readers will jump right in and be swept away by the turmoil.

Author: Robyn Young

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton, 2014

If there’s one thing that author Robyn Young has excelled at with Kingdom, it’s the sheer attention to detail that many writers of historical fiction would do well to learn from. If ever you wish to be dropped into the muck and mire, and pure visceral experience of what life was like in years gone by, complete with sights, sounds, smells and all the attendant discomfort, Young achieves this in bucketloads.

If there’s one thing that author Robyn Young has excelled at with Kingdom, it’s the sheer attention to detail that many writers of historical fiction would do well to learn from. If ever you wish to be dropped into the muck and mire, and pure visceral experience of what life was like in years gone by, complete with sights, sounds, smells and all the attendant discomfort, Young achieves this in bucketloads.In Kingdom, she ties together the final conflicts faced by Scotland’s King Robert Bruce, as he struggles against the English King Edward, and strives for a united, independent Scotland. Consequently, it’s easy to see where so much of the enmity between the two nations stems from, and both sides have blood on their hands and treachery staining their souls.

Edward’s hunt for Robert drives the Scottish king close to his end so many times, it’s almost impossible to believe that Robert’s tenacity resulted in his survival. That he was able to bounce back at all is a miracle. Yet so history would lead us to believe, and this epic is brought to life in Kingdom in a way that is gripping.

That being said, the very qualities of this story that deliver such a vivid tableau of a Robert’s struggles are the very things that hamper it. I found it difficult to relate to any of the large cast of characters precisely because Young was attempting to paint in such broad strokes. Her voice is very much omniscient, which kept me from immersing in the story nor feeling any particular emotional investment.

People die, horribly and often in most gruesome fashions, yet I couldn’t bring myself to care for their deaths. In Young’s intention to capture the bigger picture, she has, unfortunately had to sacrifice the engagement with narrative arcs in favour of interpretation of the greater events. That being said, this is still a thrilling read with some interesting assessments that will no doubt give history buffs much to consider. Those who’re not completely au fait with the history of the British Isles and who haven’t read the preceding two books may, however, find all the name-dropping and references to past events bewildering, though savvy readers will jump right in and be swept away by the turmoil.

Published on September 29, 2015 12:47

September 24, 2015

Whispers of the World that Was by ES Wynn (Storm Constantine's Wraeththu Mythos) #review #fantasy

Title:

Whispers of the World that Was (Storm Constantine’s Wraeththu Mythos)

Author: ES Wynn

Publisher: Immanion Press, 2015

Those who’re into the gothic beauty of Storm Constantine’s creations may well recall the world of the Wraeththu with great fondness. Constantine was initially responsible for two trilogies, The Wraeththu Chronicles and The Wraeththu Histories, which were pretty much required reading among lovers of dark fantasy. Subsequently Constantine has gone on to release other titles in the same setting, but has also breathed new life into her mythos by opening it to select authors, of which ES Wynn is one.

Those who’re into the gothic beauty of Storm Constantine’s creations may well recall the world of the Wraeththu with great fondness. Constantine was initially responsible for two trilogies, The Wraeththu Chronicles and The Wraeththu Histories, which were pretty much required reading among lovers of dark fantasy. Subsequently Constantine has gone on to release other titles in the same setting, but has also breathed new life into her mythos by opening it to select authors, of which ES Wynn is one.

In my mind, the Wraeththu fall somewhere between vampire and angel – beings that inherited the Earth in Constantine’s post-apocalyptic, post-technological vision. Neither male nor female, the Wraeththu express qualities of both in addition to possessing the ability to shape reality magically. Naturally, a world in upheaval provides prime fodder for storytelling, as characters transition from the old to the new.

ES Wynn has more than done justice to the setting by telling the tale of Tyse who, when we meet him, works as a salvager aboard a vessel crewed by other Wraeththu. They sift through the debris of humanity for any useful items, which they then trade for their necessities. Things take a turn for the worse, however, when Tyse salvages a meteorite that has unusual properties. His discovery brings down the unwanted attention of a mysterious foe hellbent on destroying Wraeththu culture before it has had a chance to pick itself up out of the ashes of humankind.

Wynn’s writing is lush and detailed, and he effortlessly evokes a post-apocalyptic setting so vividly, that it’s possible to taste the dogwood berry wine, so to speak. If I dare to compare his style to another’s, I think back to the sensual textures I encountered in vintage Poppy Z Brite, and leave it at that. Readers with particular tastes will understand. Ghost and Steve. Um, Hello.

While those who’ve read the Chronicles and Histories will certainly get some of the more obscure canon references in Whispers of the World that Was, this knowledge is not a prerequisite, primarily because Tyse himself is largely ignorant of what it entails to be Wraeththu. All in all, this is a satisfying read, and a worthy addition to an established fantasy mythos that deviates from standard visions involving dragons, mages and elves.

Author: ES Wynn

Publisher: Immanion Press, 2015

Those who’re into the gothic beauty of Storm Constantine’s creations may well recall the world of the Wraeththu with great fondness. Constantine was initially responsible for two trilogies, The Wraeththu Chronicles and The Wraeththu Histories, which were pretty much required reading among lovers of dark fantasy. Subsequently Constantine has gone on to release other titles in the same setting, but has also breathed new life into her mythos by opening it to select authors, of which ES Wynn is one.

Those who’re into the gothic beauty of Storm Constantine’s creations may well recall the world of the Wraeththu with great fondness. Constantine was initially responsible for two trilogies, The Wraeththu Chronicles and The Wraeththu Histories, which were pretty much required reading among lovers of dark fantasy. Subsequently Constantine has gone on to release other titles in the same setting, but has also breathed new life into her mythos by opening it to select authors, of which ES Wynn is one.In my mind, the Wraeththu fall somewhere between vampire and angel – beings that inherited the Earth in Constantine’s post-apocalyptic, post-technological vision. Neither male nor female, the Wraeththu express qualities of both in addition to possessing the ability to shape reality magically. Naturally, a world in upheaval provides prime fodder for storytelling, as characters transition from the old to the new.

ES Wynn has more than done justice to the setting by telling the tale of Tyse who, when we meet him, works as a salvager aboard a vessel crewed by other Wraeththu. They sift through the debris of humanity for any useful items, which they then trade for their necessities. Things take a turn for the worse, however, when Tyse salvages a meteorite that has unusual properties. His discovery brings down the unwanted attention of a mysterious foe hellbent on destroying Wraeththu culture before it has had a chance to pick itself up out of the ashes of humankind.

Wynn’s writing is lush and detailed, and he effortlessly evokes a post-apocalyptic setting so vividly, that it’s possible to taste the dogwood berry wine, so to speak. If I dare to compare his style to another’s, I think back to the sensual textures I encountered in vintage Poppy Z Brite, and leave it at that. Readers with particular tastes will understand. Ghost and Steve. Um, Hello.

While those who’ve read the Chronicles and Histories will certainly get some of the more obscure canon references in Whispers of the World that Was, this knowledge is not a prerequisite, primarily because Tyse himself is largely ignorant of what it entails to be Wraeththu. All in all, this is a satisfying read, and a worthy addition to an established fantasy mythos that deviates from standard visions involving dragons, mages and elves.

Published on September 24, 2015 12:02

September 17, 2015

Rock Steady by Joanne Macgregor #review

Title:

Rock Steady

Author: Joanne Macgregor

Publisher: Protea Book House, 2013

Even though this is book two in what appears to be a series dealing with the adventures of friends who attend an exclusive girls’ boarding school up in the Drakensberg, Rock Steady can be read as a standalone adventure. From the get go, I must add that Joanne drew me into the story, told from the point of view of Samantha, who is attending Clifford House Private School for Girls on a scholarship. It goes without saying that she’s under a fair amount of pressure to perform academically, so when they get a new – and aptly named – maths and science teacher Mr Delmonico, that things begin to become unpleasant.

Even though this is book two in what appears to be a series dealing with the adventures of friends who attend an exclusive girls’ boarding school up in the Drakensberg, Rock Steady can be read as a standalone adventure. From the get go, I must add that Joanne drew me into the story, told from the point of view of Samantha, who is attending Clifford House Private School for Girls on a scholarship. It goes without saying that she’s under a fair amount of pressure to perform academically, so when they get a new – and aptly named – maths and science teacher Mr Delmonico, that things begin to become unpleasant.

Sam, Jessie and Nomusa navigate their Grade 9 year with all the usual trials and tribulations – sports events, school outings, boys, bullies and dances – and the banter between the three friends comes off incredibly refreshing and natural. It’s not often that an author manages to express the sheer energy of teenagers, but Joanne totally convinced me that she’s secretly a teenager herself.

The main narrative arc in this story isn’t so much the girls’ school year, however, but also how the three friends get tangled in the doings of a nefarious gang of thieves intent on plundering South Africa’s cultural heritage. For those who don’t know, the Drakensberg is a region in South Africa that has some of the highest concentrations of ancient rock art, which not only faces natural threats thanks to gradual (and totally natural) environmental erosion, but also suffers thanks to human agents who deface or attempt to steal it.

Joanne deftly weaves in the main plot with the secondary plots in a way that doesn’t feel forced. She drops hints throughout that savvy readers may pick up on so that when the final confrontation occurs, it’s not completely left of field. Joanne’s teens are bubbly, sensitive and are possessed of a lively curiosity and sense of fun, who worry about their schoolwork, about boys, about issues at home. They feel real. Too often I’ve read YA fiction where the teens’ world seems to vanish into a boy-induced solipsist nightmare, where everything just revolves around the boy. Um, hello, teens do have genuine interests beyond boys (even if boys do feature quite high up on the menu, so to speak).

All in all, this is a fun read that I’ll happily recommend to anyone who’s got a bookish kidlet from the age of ten and older. Yes, there is – *gasp* – a kiss, but the romance elements are slight. The story focuses on the eventual altercation with rock art thieves and also weaves in a fair deal of cultural history related to the rock art without being heavy handed about it. Joanne’s writing gets a big thumbs up from yours truly for South African youth literature.

Author: Joanne Macgregor

Publisher: Protea Book House, 2013

Even though this is book two in what appears to be a series dealing with the adventures of friends who attend an exclusive girls’ boarding school up in the Drakensberg, Rock Steady can be read as a standalone adventure. From the get go, I must add that Joanne drew me into the story, told from the point of view of Samantha, who is attending Clifford House Private School for Girls on a scholarship. It goes without saying that she’s under a fair amount of pressure to perform academically, so when they get a new – and aptly named – maths and science teacher Mr Delmonico, that things begin to become unpleasant.

Even though this is book two in what appears to be a series dealing with the adventures of friends who attend an exclusive girls’ boarding school up in the Drakensberg, Rock Steady can be read as a standalone adventure. From the get go, I must add that Joanne drew me into the story, told from the point of view of Samantha, who is attending Clifford House Private School for Girls on a scholarship. It goes without saying that she’s under a fair amount of pressure to perform academically, so when they get a new – and aptly named – maths and science teacher Mr Delmonico, that things begin to become unpleasant.Sam, Jessie and Nomusa navigate their Grade 9 year with all the usual trials and tribulations – sports events, school outings, boys, bullies and dances – and the banter between the three friends comes off incredibly refreshing and natural. It’s not often that an author manages to express the sheer energy of teenagers, but Joanne totally convinced me that she’s secretly a teenager herself.

The main narrative arc in this story isn’t so much the girls’ school year, however, but also how the three friends get tangled in the doings of a nefarious gang of thieves intent on plundering South Africa’s cultural heritage. For those who don’t know, the Drakensberg is a region in South Africa that has some of the highest concentrations of ancient rock art, which not only faces natural threats thanks to gradual (and totally natural) environmental erosion, but also suffers thanks to human agents who deface or attempt to steal it.

Joanne deftly weaves in the main plot with the secondary plots in a way that doesn’t feel forced. She drops hints throughout that savvy readers may pick up on so that when the final confrontation occurs, it’s not completely left of field. Joanne’s teens are bubbly, sensitive and are possessed of a lively curiosity and sense of fun, who worry about their schoolwork, about boys, about issues at home. They feel real. Too often I’ve read YA fiction where the teens’ world seems to vanish into a boy-induced solipsist nightmare, where everything just revolves around the boy. Um, hello, teens do have genuine interests beyond boys (even if boys do feature quite high up on the menu, so to speak).

All in all, this is a fun read that I’ll happily recommend to anyone who’s got a bookish kidlet from the age of ten and older. Yes, there is – *gasp* – a kiss, but the romance elements are slight. The story focuses on the eventual altercation with rock art thieves and also weaves in a fair deal of cultural history related to the rock art without being heavy handed about it. Joanne’s writing gets a big thumbs up from yours truly for South African youth literature.

Published on September 17, 2015 12:46

September 16, 2015

Guns & Romances author Kim Murphy

K Murphy Wilbanks wrote a short story that we included in the Guns & Romances anthology that bit me quite hard, in all the right spots, and I'm more than pleased to welcome here here today for a little Q&A. Pick up your copy at Amazon, Kobo or Smashwords.

Welcome! Tell us a little about yourself.

My name is K Murphy Wilbanks, and I'm from Chicago. Once upon a time I was a freelance court reporter, but these days I'm a stay-at-home parent. My story "Heavy Things" from the Guns & Romances anthology is my first published piece of fiction.

My name is K Murphy Wilbanks, and I'm from Chicago. Once upon a time I was a freelance court reporter, but these days I'm a stay-at-home parent. My story "Heavy Things" from the Guns & Romances anthology is my first published piece of fiction.

Tell us more about your story and what you enjoyed about writing it.

While brainstorming a song to use for inspiration, my husband was talking about all the different musical acts he met while working as a bartender on Beale Street in Memphis. He happened to mention Phish. I have a friend who's a big fan of theirs, who was always encouraging me to check them out, but I just never got around to it. I decided what the hell, now's as good a time as any, and Googled them. The first song that came up on YouTube was "Heavy Things." I listened to the lyrics and thought the mordant, madcap irony of the whole thing would fit well with the kind of story I wanted to write. I knew I wanted to set it in Chicago, and I thought about that title and how it could possibly relate to the general idea I had of this woman bartender who was romantically involved with her boss and finds out he's got a secret. The title brought to mind a memory of a strange tragedy that was big news back when I was working in downtown Chicago back in the '90s. Bingo! I had a climax, the nature of that particular news story gave me the season, and everything else just sort of fell together after that.

Why do you think short fiction is important?

The broader answer is that human beings like to tell stories. It's hardwired into our brains, and the earliest form, oral storytelling, was by necessity short fiction – you know, acting out around the campfire how Glargh the Unfortunate got his ass handed to him by a saber-toothed tiger while out on the tribe's big hunt. So I think we're born with a hunger for short stories, and that whets the appetite for longer, more immersive forms, like novels.

In a more personal sense, short fiction has helped me learn how to get my point across in fewer words than is my habit. And while laboring on my first novel, each short story I've written has become a message to myself, repeated over and over, that, yes, I really can finish stuff. If you've been at it a long time, you start to wonder after a while whether you're kidding yourself, so it's good to have some kind of concrete proof, however small.

What is your favourite short story?