Nerine Dorman's Blog, page 44

August 19, 2016

INSPIRE! In conversation with Cat Hellisen, author

Cat Hellisen and I go way back, all the way back to Cape Town's Sanctuary nights at the old Purple Turtle during the late 1990s where DJ Reanimator used to spin Bauhaus and Einstuerzende Neubauten ... okay, no, wait, that's ancient prehistory. But it's safe to say we've known each other for years, and Cat's one the people who's helped inspire me to attain the highs (and helped keep me going through the lows) of this thing called SFF publishing.

Not only is she the creator of some of the most profound, nuanced fantasy I've read in recent years, she also possesses a keen understanding of SFF as a genre, and I value her opinion when it comes to our discussions about this industry. If you've yet to check out her novels, go take a gander at her Amazon page .

So, without further ado, here's a transcript of a little dialogue we had this week, in which we discuss world building, theme and trends in SFF...

ND: Stories and the world around you – I've loved recognising bits of the world I know in your stories (like Pelimburg in your Hobverse) or even the way you've portrayed Joburg in

Charm

. With your recent move to Scotland, are there parts of your new space that inspire you? That may creep into the story?

ND: Stories and the world around you – I've loved recognising bits of the world I know in your stories (like Pelimburg in your Hobverse) or even the way you've portrayed Joburg in

Charm

. With your recent move to Scotland, are there parts of your new space that inspire you? That may creep into the story?

CH: I'm very much influenced by my environment (to the point that you can tell which of my books are written in what season) so there are definitely elements that are going to take root in the story soil. The book I'm working on now has a quasi-European setting, so it kinda helps to be in Scotland. Not that the landscape is Scottish particularly, but I know exactly what a jackdaw sounds like now, and elements like that will inform the text. It's also pretty amazing to be in a country where I can go walk around the ruins of castles and forts, where ancient churches are as much a part of the landscape as shopping malls. To be able to get close-up looks at old stone work and so on, or go into the caves where Saint Margaret went to pray - they help with building a mental picture for me as I write.

ND: Do you have any idée fixes? For instance, reading Marguerite Poland’s books, she often brings in the theme of birds that convey a theme. Are there any favourite, small details in real life that have crept into your stories – little Easter eggs as such that people have picked up on?

CH: I don't know if I'd call them idée fixes, but there are definitely recurring elements from my psychological landscape that litter my writing and I do rather like that. I always think of JG Ballard and his empty swimming pools, or John Irving and his bears. I don't set out to incorporate these motifs, but they're obviously things I fixate on: labyrinths, and the Space Between Worlds (which sometimes doubles as the labyrinth), masks, birds, and water. As far as themes go, I remember someone once telling me that my constant theme is broken boys saving each other, which is a little unfair because my girls are just as broken, but they wear better masks.

ND: We appear to be seeing what appears to be a new wave of readers (and authors) of SFF who're getting into the genre in the wake successes like Twilight, The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, yet when I've spoken to them, very few have heard of classics such as Ursula K LeGuin, CJ Cherryh, Katharine Kerr and others of their ilk. I know this discussion crops up often online on the lists, but if you had to make a checklist of must-read fantasy authors, who would you suggest and why do you think it's so important for others to read outside of their comfort zone?

CH: Read outside your comfort zone because you never know what wonder will strike, what new concept or thought. For fiction, if people are coming from a tradition of Harry Potter, I'd definitely suggest they read Diana Wynne Jones' Chrestomanci series, and le Guin's marvelous Earthsea books. I began my speculative education on my father's library hauls, so I had a grounding in classic SF - in Asimov, Aldiss, Poul Anderson, James Blish, etc, but I veered away from them and toward writers like Tanith Lee, Clive Barker, Octavia Butler, Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, Poppy Z Brite and Mary Gentle. If they're looking for more modern writers there is a wealth of new and less-new speculative authors - I'd suggest looking at presses like Small Beer, Apex, and Solaris.

Weightless Books

is an ebook store that stocks a range of good small press work.

CH: Read outside your comfort zone because you never know what wonder will strike, what new concept or thought. For fiction, if people are coming from a tradition of Harry Potter, I'd definitely suggest they read Diana Wynne Jones' Chrestomanci series, and le Guin's marvelous Earthsea books. I began my speculative education on my father's library hauls, so I had a grounding in classic SF - in Asimov, Aldiss, Poul Anderson, James Blish, etc, but I veered away from them and toward writers like Tanith Lee, Clive Barker, Octavia Butler, Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, Poppy Z Brite and Mary Gentle. If they're looking for more modern writers there is a wealth of new and less-new speculative authors - I'd suggest looking at presses like Small Beer, Apex, and Solaris.

Weightless Books

is an ebook store that stocks a range of good small press work.

I also encourage people to read widely on the subjects that fascinate them and go right back to the key works in that field. The more you know about the world and history and politics, the more informed and nuanced your work will be.

ND: What are some of the issues you pick up in contemporary SFF that you suspect are related to the paucity of authors’ source material? For instance I’ve encountered so many writers who’ve been inspired because they’ve read Twilight or The Hunger Games, and that is pretty much the first experience they’ve had with truly reading – and now they want to go out and create. Yet in one case, a lady returned to me saying that when I’d turned her onto reading Wuthering Heights, she’d struggled because of the unfamiliar vocabulary. And her writing showed this paucity that no amount of editing could fix.

CH: It depends what you're reading. Yes, some of the larger houses put out work that is strained by the writer's lack of familiarity with the genre, and these books end up reinventing the wheel, or serving us the same old pap in a plastic bowl, but there is also great stuff coming out, often from smaller presses. As you say though, the great stuff with the better ideas and higher level of writing comes from writers who are readers, and you can spot it instantly in their work. They are the writers who make Classical references that they expect their readers to get without hand-holding, or whose books are a conversation with the stories that have come before. They use language skilfully and play with words in a way a less-well read writer simply can't.

It's become a bit of a cliche to say it, but I believe that you cannot be a decent writer if you are not first and foremost a reader.

ND: Do you think the bigger houses should (or would) look at starting up smaller, boutique imprints or do you think those small presses and co-operatives that are starting up in this literary vacuum are going to fill that need for readers and authors? Considering, especially, the high overheads attached to even bringing out an anthology (there are hidden costs readers generally aren't aware of). What do you see as a possible future for publishing.

CH: I have no idea what the future holds. I'm tentatively going to suggest that it's going to carry on pretty much as-is, with the large presses putting out big names and sure-fire type sellers (celeb bios, On Topic Thrillers, etc) and taking the occasional chance when marketing allows, and the smaller presses will fill the niches with more interesting stuff, and some of those smaller presses are going to become larger and larger and forces to be reckoned with. And so it will go.

CH: I have no idea what the future holds. I'm tentatively going to suggest that it's going to carry on pretty much as-is, with the large presses putting out big names and sure-fire type sellers (celeb bios, On Topic Thrillers, etc) and taking the occasional chance when marketing allows, and the smaller presses will fill the niches with more interesting stuff, and some of those smaller presses are going to become larger and larger and forces to be reckoned with. And so it will go.

I am very excited about the co-operative model because I think this is where the mid-listers are going to congregate. In recent years the concept of the mid-list author who is not a household name, but built up a decent fan base over a collection of novels, and now sells consistently, has all but been eradicated. You either make it big out the box, or you're dumped for the next New Author Who Might Make It Big. Writing generally improves over time, so writers aren't really getting the opportunity anymore to build their audience and develop their voice. And I think that's where co-ops and small presses are going to come in.

ND: One thing that I've always appreciated about your writing is its layering and nuance – how do you approach this?

CH: Thank you kindly! It goes back to the reading non-fiction thing. Being curious about the world you actually live in is a great way to enrich your imaginary worlds. And twitter is not the world. Go walk outside, go explore aimlessly, go to the library and grab a book from the history section that looks interesting. Find out about your family secrets and stitch them into your own stories.

On a writing level, I approach it by revising, revising, revising. I need all that information in my brain to get embroidered into my writing, and that only happens with revision. Layering is one of the most important aspects of revision - going in and reworking the warp and weft, strengthening the story where it needs strengthening, unravelling the bits that are tangled nonsense. To drag this metaphor on to its inevitable conclusion - you don't make story out of just cloth tacked together, you need shape, you need strengthened seams, you need hidden pockets, silk linings, buttons and embroidery.

ND: I’ve always tried to explain to authors that adding layering is about engaging the physical senses – sight, sound, touch, taste, smell – but also about engaging with emotion and intellect. Often writers think it’s fine to have a ‘laundry list’ of descriptions but don’t quite immerse how environment or events relate to the character. How would you suggest they break through this barrier to making their writing flow?

CH: Ah, the laundry list. Description of physicality and mannerisms is not characterisation. If a person had to describe me as only "a loud chubster with dyed red hair, wearing mum-jeans." It might be accurate on some level, but it would tell you nothing about who I am. It would be fine if you were writing me as a once-off character who merely imparts some information to our Intrepid Hero, but if I was a main or secondary character, there needs to be more there to make me a human, to make me a character the reader feels they know.

CH: Ah, the laundry list. Description of physicality and mannerisms is not characterisation. If a person had to describe me as only "a loud chubster with dyed red hair, wearing mum-jeans." It might be accurate on some level, but it would tell you nothing about who I am. It would be fine if you were writing me as a once-off character who merely imparts some information to our Intrepid Hero, but if I was a main or secondary character, there needs to be more there to make me a human, to make me a character the reader feels they know.

That means adding dimensions that are more than just surface, superficial description. I talk about interiority - what emotion do they feel, how does it physically affect them, what do they sense. "Get inside their head" is a favourite critique which I think you know I've levelled at more than a few betas. Ask yourself questions about why a character does something in your book - build them a back story. Write it down if necessary. But a real character has a history, and it lies under the surface of everything you write about them, and informs every on-page decision they make.

ND: And for you, if you had to pick some of your all-time favourite characters/characterisation, who is this and why do you think the author nails it in this particular case(s).

CH: Ah wow this is a tough one. So many good works out there, and what's a favourite? My favourites change over time, though there are a few constants. I'm a sucker for a certain character type, I won't pretend otherwise. I love Howl and Sophie from Howl's Moving Castle , Pie'oh'pah from Barker's Imagica , Tenar (and Ged) from The Tombs of Atuan . Actually, Ged is a very good example of a character who grows and changes through the books. In A Wizard of Earthsea, he is cocksure and difficult to like, and power gives him an arrogance that ultimately is his downfall. I like Ged better in Atuan, where he's a little wiser and a little more broken. If you read the Under the Poppy trilogy by Kathe Koja, following her two puppeteers and sometime spies, you get a pretty good idea of the characters I love.

Follow Cat Hellisen on Twitter , support her on Patreon or friend her on Facebook .

Not only is she the creator of some of the most profound, nuanced fantasy I've read in recent years, she also possesses a keen understanding of SFF as a genre, and I value her opinion when it comes to our discussions about this industry. If you've yet to check out her novels, go take a gander at her Amazon page .

So, without further ado, here's a transcript of a little dialogue we had this week, in which we discuss world building, theme and trends in SFF...

ND: Stories and the world around you – I've loved recognising bits of the world I know in your stories (like Pelimburg in your Hobverse) or even the way you've portrayed Joburg in

Charm

. With your recent move to Scotland, are there parts of your new space that inspire you? That may creep into the story?

ND: Stories and the world around you – I've loved recognising bits of the world I know in your stories (like Pelimburg in your Hobverse) or even the way you've portrayed Joburg in

Charm

. With your recent move to Scotland, are there parts of your new space that inspire you? That may creep into the story?CH: I'm very much influenced by my environment (to the point that you can tell which of my books are written in what season) so there are definitely elements that are going to take root in the story soil. The book I'm working on now has a quasi-European setting, so it kinda helps to be in Scotland. Not that the landscape is Scottish particularly, but I know exactly what a jackdaw sounds like now, and elements like that will inform the text. It's also pretty amazing to be in a country where I can go walk around the ruins of castles and forts, where ancient churches are as much a part of the landscape as shopping malls. To be able to get close-up looks at old stone work and so on, or go into the caves where Saint Margaret went to pray - they help with building a mental picture for me as I write.

ND: Do you have any idée fixes? For instance, reading Marguerite Poland’s books, she often brings in the theme of birds that convey a theme. Are there any favourite, small details in real life that have crept into your stories – little Easter eggs as such that people have picked up on?

CH: I don't know if I'd call them idée fixes, but there are definitely recurring elements from my psychological landscape that litter my writing and I do rather like that. I always think of JG Ballard and his empty swimming pools, or John Irving and his bears. I don't set out to incorporate these motifs, but they're obviously things I fixate on: labyrinths, and the Space Between Worlds (which sometimes doubles as the labyrinth), masks, birds, and water. As far as themes go, I remember someone once telling me that my constant theme is broken boys saving each other, which is a little unfair because my girls are just as broken, but they wear better masks.

ND: We appear to be seeing what appears to be a new wave of readers (and authors) of SFF who're getting into the genre in the wake successes like Twilight, The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, yet when I've spoken to them, very few have heard of classics such as Ursula K LeGuin, CJ Cherryh, Katharine Kerr and others of their ilk. I know this discussion crops up often online on the lists, but if you had to make a checklist of must-read fantasy authors, who would you suggest and why do you think it's so important for others to read outside of their comfort zone?

CH: Read outside your comfort zone because you never know what wonder will strike, what new concept or thought. For fiction, if people are coming from a tradition of Harry Potter, I'd definitely suggest they read Diana Wynne Jones' Chrestomanci series, and le Guin's marvelous Earthsea books. I began my speculative education on my father's library hauls, so I had a grounding in classic SF - in Asimov, Aldiss, Poul Anderson, James Blish, etc, but I veered away from them and toward writers like Tanith Lee, Clive Barker, Octavia Butler, Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, Poppy Z Brite and Mary Gentle. If they're looking for more modern writers there is a wealth of new and less-new speculative authors - I'd suggest looking at presses like Small Beer, Apex, and Solaris.

Weightless Books

is an ebook store that stocks a range of good small press work.

CH: Read outside your comfort zone because you never know what wonder will strike, what new concept or thought. For fiction, if people are coming from a tradition of Harry Potter, I'd definitely suggest they read Diana Wynne Jones' Chrestomanci series, and le Guin's marvelous Earthsea books. I began my speculative education on my father's library hauls, so I had a grounding in classic SF - in Asimov, Aldiss, Poul Anderson, James Blish, etc, but I veered away from them and toward writers like Tanith Lee, Clive Barker, Octavia Butler, Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, Poppy Z Brite and Mary Gentle. If they're looking for more modern writers there is a wealth of new and less-new speculative authors - I'd suggest looking at presses like Small Beer, Apex, and Solaris.

Weightless Books

is an ebook store that stocks a range of good small press work.I also encourage people to read widely on the subjects that fascinate them and go right back to the key works in that field. The more you know about the world and history and politics, the more informed and nuanced your work will be.

ND: What are some of the issues you pick up in contemporary SFF that you suspect are related to the paucity of authors’ source material? For instance I’ve encountered so many writers who’ve been inspired because they’ve read Twilight or The Hunger Games, and that is pretty much the first experience they’ve had with truly reading – and now they want to go out and create. Yet in one case, a lady returned to me saying that when I’d turned her onto reading Wuthering Heights, she’d struggled because of the unfamiliar vocabulary. And her writing showed this paucity that no amount of editing could fix.

CH: It depends what you're reading. Yes, some of the larger houses put out work that is strained by the writer's lack of familiarity with the genre, and these books end up reinventing the wheel, or serving us the same old pap in a plastic bowl, but there is also great stuff coming out, often from smaller presses. As you say though, the great stuff with the better ideas and higher level of writing comes from writers who are readers, and you can spot it instantly in their work. They are the writers who make Classical references that they expect their readers to get without hand-holding, or whose books are a conversation with the stories that have come before. They use language skilfully and play with words in a way a less-well read writer simply can't.

It's become a bit of a cliche to say it, but I believe that you cannot be a decent writer if you are not first and foremost a reader.

ND: Do you think the bigger houses should (or would) look at starting up smaller, boutique imprints or do you think those small presses and co-operatives that are starting up in this literary vacuum are going to fill that need for readers and authors? Considering, especially, the high overheads attached to even bringing out an anthology (there are hidden costs readers generally aren't aware of). What do you see as a possible future for publishing.

CH: I have no idea what the future holds. I'm tentatively going to suggest that it's going to carry on pretty much as-is, with the large presses putting out big names and sure-fire type sellers (celeb bios, On Topic Thrillers, etc) and taking the occasional chance when marketing allows, and the smaller presses will fill the niches with more interesting stuff, and some of those smaller presses are going to become larger and larger and forces to be reckoned with. And so it will go.

CH: I have no idea what the future holds. I'm tentatively going to suggest that it's going to carry on pretty much as-is, with the large presses putting out big names and sure-fire type sellers (celeb bios, On Topic Thrillers, etc) and taking the occasional chance when marketing allows, and the smaller presses will fill the niches with more interesting stuff, and some of those smaller presses are going to become larger and larger and forces to be reckoned with. And so it will go.I am very excited about the co-operative model because I think this is where the mid-listers are going to congregate. In recent years the concept of the mid-list author who is not a household name, but built up a decent fan base over a collection of novels, and now sells consistently, has all but been eradicated. You either make it big out the box, or you're dumped for the next New Author Who Might Make It Big. Writing generally improves over time, so writers aren't really getting the opportunity anymore to build their audience and develop their voice. And I think that's where co-ops and small presses are going to come in.

ND: One thing that I've always appreciated about your writing is its layering and nuance – how do you approach this?

CH: Thank you kindly! It goes back to the reading non-fiction thing. Being curious about the world you actually live in is a great way to enrich your imaginary worlds. And twitter is not the world. Go walk outside, go explore aimlessly, go to the library and grab a book from the history section that looks interesting. Find out about your family secrets and stitch them into your own stories.

On a writing level, I approach it by revising, revising, revising. I need all that information in my brain to get embroidered into my writing, and that only happens with revision. Layering is one of the most important aspects of revision - going in and reworking the warp and weft, strengthening the story where it needs strengthening, unravelling the bits that are tangled nonsense. To drag this metaphor on to its inevitable conclusion - you don't make story out of just cloth tacked together, you need shape, you need strengthened seams, you need hidden pockets, silk linings, buttons and embroidery.

ND: I’ve always tried to explain to authors that adding layering is about engaging the physical senses – sight, sound, touch, taste, smell – but also about engaging with emotion and intellect. Often writers think it’s fine to have a ‘laundry list’ of descriptions but don’t quite immerse how environment or events relate to the character. How would you suggest they break through this barrier to making their writing flow?

CH: Ah, the laundry list. Description of physicality and mannerisms is not characterisation. If a person had to describe me as only "a loud chubster with dyed red hair, wearing mum-jeans." It might be accurate on some level, but it would tell you nothing about who I am. It would be fine if you were writing me as a once-off character who merely imparts some information to our Intrepid Hero, but if I was a main or secondary character, there needs to be more there to make me a human, to make me a character the reader feels they know.

CH: Ah, the laundry list. Description of physicality and mannerisms is not characterisation. If a person had to describe me as only "a loud chubster with dyed red hair, wearing mum-jeans." It might be accurate on some level, but it would tell you nothing about who I am. It would be fine if you were writing me as a once-off character who merely imparts some information to our Intrepid Hero, but if I was a main or secondary character, there needs to be more there to make me a human, to make me a character the reader feels they know.That means adding dimensions that are more than just surface, superficial description. I talk about interiority - what emotion do they feel, how does it physically affect them, what do they sense. "Get inside their head" is a favourite critique which I think you know I've levelled at more than a few betas. Ask yourself questions about why a character does something in your book - build them a back story. Write it down if necessary. But a real character has a history, and it lies under the surface of everything you write about them, and informs every on-page decision they make.

ND: And for you, if you had to pick some of your all-time favourite characters/characterisation, who is this and why do you think the author nails it in this particular case(s).

CH: Ah wow this is a tough one. So many good works out there, and what's a favourite? My favourites change over time, though there are a few constants. I'm a sucker for a certain character type, I won't pretend otherwise. I love Howl and Sophie from Howl's Moving Castle , Pie'oh'pah from Barker's Imagica , Tenar (and Ged) from The Tombs of Atuan . Actually, Ged is a very good example of a character who grows and changes through the books. In A Wizard of Earthsea, he is cocksure and difficult to like, and power gives him an arrogance that ultimately is his downfall. I like Ged better in Atuan, where he's a little wiser and a little more broken. If you read the Under the Poppy trilogy by Kathe Koja, following her two puppeteers and sometime spies, you get a pretty good idea of the characters I love.

Follow Cat Hellisen on Twitter , support her on Patreon or friend her on Facebook .

Published on August 19, 2016 11:53

August 14, 2016

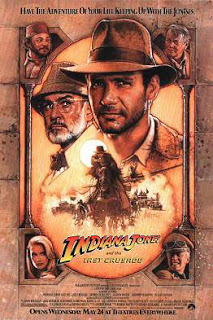

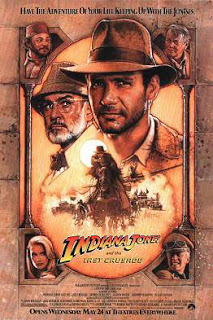

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) #film

When Dr. Henry Jones Sr. suddenly goes missing while pursuing the Holy Grail, eminent archaeologist Indiana Jones must follow in his father's footsteps and stop the Nazis.

Indy's entanglements with the Nazis as arch-villains are pretty much stock standard fare for his exploits. At least by the third in the series, it's on the verge of becoming – dare I say it? – old hat. Nevertheless, Last Crusade is, in my mind, a stronger film than its predecessor in that it delves into the complicated relationship Indy has with his father (played by Sean Connery), as well as a final test of faith. We see Indy on the trail of rescuing his dad from the Nazis, with the aid of a femme fatale archaeologist Dr Elsa Schneider. She *is* rather distracting but she's far from the damsel in distress.

Of course the rescue mission does not go off smoothly. There are comical moments, when Indy and his dad are tied to a chair with the room burning around them – possibly one of my favourite Indy routines. The humour is silly, but so charming.

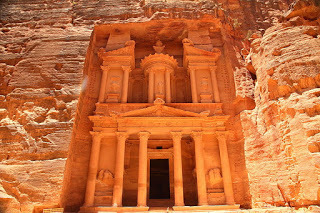

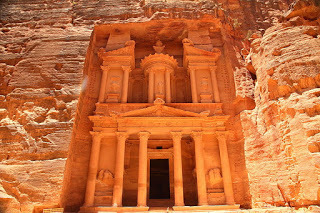

And of course the action, the stunts – they are typically edge-of-your-seat. Their journey eventually takes our heroes from Venice crypts and German castles to a mysterious city (in reality this is none other than The Treasury in Petra, Jordan, which is still on my bucket list of places to visit). As with each Indy film, there is a central theme and with this one it's a quest for the Holy Grail – which will allegedly gift the user with immortality. (Not a good thing for Hitler to have, no?) Indy and his dad take opposite stances, with Indy having chosen rationality his entire life while his dad has devoted his life to chasing a so-called magical object with all the fervour of a religious convert.

I need to digress here to this most excellent article by Leah Schnelbach about the religious themes running through this movie. Yes, it's a long article, but when you're done you'll possibly agree that the Indiana Jones films have far more substance than your bog-standard action films. Each time Indy has his brush with the supernatural, he clings stubbornly to science and reason, despite his experiences. Whether this is just his refusal to be swept away by that for which he has no logical explanation or him merely taking things in his stride, we're never quite sure, however he has perhaps his most important test in this film.

The Treasury in Petra, Jordan. Picture: Wiki CommonsThe pacing with Last Crusade is tight – there's often little respite from one challenge to the next. Though the mechanisms of the dangers they face are not authentic, yet they have that fantasy elements that blend well and add a hyper-real, epic feel to the films – none of this will happen in real life but it's thrilling to watch. The slight slapstick edge is just right without feeling overdone as it had in Temple of Doom.

The Treasury in Petra, Jordan. Picture: Wiki CommonsThe pacing with Last Crusade is tight – there's often little respite from one challenge to the next. Though the mechanisms of the dangers they face are not authentic, yet they have that fantasy elements that blend well and add a hyper-real, epic feel to the films – none of this will happen in real life but it's thrilling to watch. The slight slapstick edge is just right without feeling overdone as it had in Temple of Doom.

I admit that the first time I saw this film I didn't really love it as much as I did the previous ones. Second time round, I was assailed by the feels because of the father-son element. Harrison Ford is visibly older, and so is Indy – perhaps wiser but still the daredevil. I guess what makes Indy one of my perennial heroes is the fact that he thinks on his feet, often solving puzzles that I know for a fact would see me dead within instants. He has passion driving him – for knowledge, for discovering old secrets and revealing (and preserving) them for the good of mankind. Yes, he's a bit of a rogue, but his heart is in the right place. This film's a keeper.

Indy's entanglements with the Nazis as arch-villains are pretty much stock standard fare for his exploits. At least by the third in the series, it's on the verge of becoming – dare I say it? – old hat. Nevertheless, Last Crusade is, in my mind, a stronger film than its predecessor in that it delves into the complicated relationship Indy has with his father (played by Sean Connery), as well as a final test of faith. We see Indy on the trail of rescuing his dad from the Nazis, with the aid of a femme fatale archaeologist Dr Elsa Schneider. She *is* rather distracting but she's far from the damsel in distress.

Of course the rescue mission does not go off smoothly. There are comical moments, when Indy and his dad are tied to a chair with the room burning around them – possibly one of my favourite Indy routines. The humour is silly, but so charming.

And of course the action, the stunts – they are typically edge-of-your-seat. Their journey eventually takes our heroes from Venice crypts and German castles to a mysterious city (in reality this is none other than The Treasury in Petra, Jordan, which is still on my bucket list of places to visit). As with each Indy film, there is a central theme and with this one it's a quest for the Holy Grail – which will allegedly gift the user with immortality. (Not a good thing for Hitler to have, no?) Indy and his dad take opposite stances, with Indy having chosen rationality his entire life while his dad has devoted his life to chasing a so-called magical object with all the fervour of a religious convert.

I need to digress here to this most excellent article by Leah Schnelbach about the religious themes running through this movie. Yes, it's a long article, but when you're done you'll possibly agree that the Indiana Jones films have far more substance than your bog-standard action films. Each time Indy has his brush with the supernatural, he clings stubbornly to science and reason, despite his experiences. Whether this is just his refusal to be swept away by that for which he has no logical explanation or him merely taking things in his stride, we're never quite sure, however he has perhaps his most important test in this film.

The Treasury in Petra, Jordan. Picture: Wiki CommonsThe pacing with Last Crusade is tight – there's often little respite from one challenge to the next. Though the mechanisms of the dangers they face are not authentic, yet they have that fantasy elements that blend well and add a hyper-real, epic feel to the films – none of this will happen in real life but it's thrilling to watch. The slight slapstick edge is just right without feeling overdone as it had in Temple of Doom.

The Treasury in Petra, Jordan. Picture: Wiki CommonsThe pacing with Last Crusade is tight – there's often little respite from one challenge to the next. Though the mechanisms of the dangers they face are not authentic, yet they have that fantasy elements that blend well and add a hyper-real, epic feel to the films – none of this will happen in real life but it's thrilling to watch. The slight slapstick edge is just right without feeling overdone as it had in Temple of Doom.I admit that the first time I saw this film I didn't really love it as much as I did the previous ones. Second time round, I was assailed by the feels because of the father-son element. Harrison Ford is visibly older, and so is Indy – perhaps wiser but still the daredevil. I guess what makes Indy one of my perennial heroes is the fact that he thinks on his feet, often solving puzzles that I know for a fact would see me dead within instants. He has passion driving him – for knowledge, for discovering old secrets and revealing (and preserving) them for the good of mankind. Yes, he's a bit of a rogue, but his heart is in the right place. This film's a keeper.

Published on August 14, 2016 13:28

July 31, 2016

Royal Assassin (Farseer Trilogy #2)

Title:

Royal Assassin (Farseer Trilogy #2)

Author: Robin Hobb

Publisher: Voyager, 1997

I lose no time telling folks how much I love Robin Hobb's FitzChivalry stories, and this current review represents my second read through of Royal Assassin. Unfortunately, I'd let time slip between book 1 and 2, so I had to scramble a bit to pick up the threads – and this is most certainly a series that I recommend reading back to back. This is due to the huge cast of characters in addition to the multiple, nuanced plot threads.

I lose no time telling folks how much I love Robin Hobb's FitzChivalry stories, and this current review represents my second read through of Royal Assassin. Unfortunately, I'd let time slip between book 1 and 2, so I had to scramble a bit to pick up the threads – and this is most certainly a series that I recommend reading back to back. This is due to the huge cast of characters in addition to the multiple, nuanced plot threads.

We resume with Fitz in the Mountain Kingdom, after he has foiled a plot instigated by his half-uncle Prince Regal, whom we've all come to love to hate by now. Months pass before he is well enough to travel back to Buckkeep, and in that time he suffers seizures. He really has lost much confidence.

He returns to a castle where King Shrewd is ill, and it's clear that Regal is machinating to take power (and ruin the kingdoms while he's at it). Prince Verity is tied up trying to protect the duchies from the Red Ship Raiders and, if that's not enough, the woman Fitz loves now works for Patience – his biological father's widow. Plainly put, it's a tangled mess, and Fitz's decisions don't always work out for the best.

We learn more of Fitz's Wit magic in his relationship with the wolf Nighteyes, whom he rescues from a trapper – and to me, this symbiotic relationship is one of the most beautiful friendships I've ever encountered in the written word. Hobb understands her subjects, be they people or animal.

Fitz suffers terribly, that is all I will say for fear of spoiling the story. By the end of the book, he really has gone through a crucible – especially since Prince Verity is no longer there to protect him, as he's gone haring off hunting for the fabled Elderlings to help against the raiders. Hobb offers potential twists that lulled me into expecting one outcome, only to have my expectations dashed as the story plunges ever more into yet another nadir. So far as the Fitz stories go, this one is perhaps the bleakest. And yet it is not without a glimmer of hope, and the ending is just perfect.

My thoughts on having reread are that I'd missed a lot of the nuance when I'd read this when I was younger. Hobb's staggering ability to perceive the hearts of her characters blows me out of the water. Even Regal's motivations are understandable. He's not a one-dimensional Disney-esque villain but one would almost wish that twisted creature that he is, it would be possible to redeem him.

Those who're fiending after fast-paced, action-packed adventures had best move on. As always, Hobb's writing rewards the patient reader who revels in a slowly unfolding epic masterpiece. Not a single bit of information or action is without some sort of impact later on in the story. There was no saggy middle-book syndrome with this installment.

Author: Robin Hobb

Publisher: Voyager, 1997

I lose no time telling folks how much I love Robin Hobb's FitzChivalry stories, and this current review represents my second read through of Royal Assassin. Unfortunately, I'd let time slip between book 1 and 2, so I had to scramble a bit to pick up the threads – and this is most certainly a series that I recommend reading back to back. This is due to the huge cast of characters in addition to the multiple, nuanced plot threads.

I lose no time telling folks how much I love Robin Hobb's FitzChivalry stories, and this current review represents my second read through of Royal Assassin. Unfortunately, I'd let time slip between book 1 and 2, so I had to scramble a bit to pick up the threads – and this is most certainly a series that I recommend reading back to back. This is due to the huge cast of characters in addition to the multiple, nuanced plot threads.We resume with Fitz in the Mountain Kingdom, after he has foiled a plot instigated by his half-uncle Prince Regal, whom we've all come to love to hate by now. Months pass before he is well enough to travel back to Buckkeep, and in that time he suffers seizures. He really has lost much confidence.

He returns to a castle where King Shrewd is ill, and it's clear that Regal is machinating to take power (and ruin the kingdoms while he's at it). Prince Verity is tied up trying to protect the duchies from the Red Ship Raiders and, if that's not enough, the woman Fitz loves now works for Patience – his biological father's widow. Plainly put, it's a tangled mess, and Fitz's decisions don't always work out for the best.

We learn more of Fitz's Wit magic in his relationship with the wolf Nighteyes, whom he rescues from a trapper – and to me, this symbiotic relationship is one of the most beautiful friendships I've ever encountered in the written word. Hobb understands her subjects, be they people or animal.

Fitz suffers terribly, that is all I will say for fear of spoiling the story. By the end of the book, he really has gone through a crucible – especially since Prince Verity is no longer there to protect him, as he's gone haring off hunting for the fabled Elderlings to help against the raiders. Hobb offers potential twists that lulled me into expecting one outcome, only to have my expectations dashed as the story plunges ever more into yet another nadir. So far as the Fitz stories go, this one is perhaps the bleakest. And yet it is not without a glimmer of hope, and the ending is just perfect.

My thoughts on having reread are that I'd missed a lot of the nuance when I'd read this when I was younger. Hobb's staggering ability to perceive the hearts of her characters blows me out of the water. Even Regal's motivations are understandable. He's not a one-dimensional Disney-esque villain but one would almost wish that twisted creature that he is, it would be possible to redeem him.

Those who're fiending after fast-paced, action-packed adventures had best move on. As always, Hobb's writing rewards the patient reader who revels in a slowly unfolding epic masterpiece. Not a single bit of information or action is without some sort of impact later on in the story. There was no saggy middle-book syndrome with this installment.

Published on July 31, 2016 12:55

July 28, 2016

The Shining (1980) #review

A family heads to an isolated hotel for the winter where an evil and spiritual presence influences the father into violence, while his psychic son sees horrific forebodings from the past and of the future.

I have a terrible admission to make – but better late than never, amiright? I only watched The Shining for the first time this year. Yes. I’ve been lurking around on this planet for more than 30 years and I’d NEVER EVER EVER watched this masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick.

I have a terrible admission to make – but better late than never, amiright? I only watched The Shining for the first time this year. Yes. I’ve been lurking around on this planet for more than 30 years and I’d NEVER EVER EVER watched this masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick.

Also, I absolutely loathe Jack Nicholson. I don’t know what it is about him – his face, his voice. I agree he’s a fantastic actor but he makes my flesh crawl and he was perfect for this role as Jack Torrance, the author who simply cannot get into his novel. The true star of this film is his long-suffering wife Wendy, who somehow keeps it all together when everyone else around her is going completely stark-raving bonkers. Little Danny’s premonitions are creepy, but even creepier still is the location.

Kudos to the set dressers and builders – the interiors of the Overlook Hotel are phenomenal and a fitting tribute to all that is awful about late-1970s décor. Kubrick manages to make me feel horrifically claustrophobic and paranoid all at once. Trapped like Jack and his family, we can only sit back and watch how Jack spirals into madness, and we know things aren’t going to end well. All the while poor, dear Wendy comes to realise she needs to get herself and her son out of this place – easier said than done when the inevitable blizzard cuts them off from the rest of this world. And she’s resilient, tenacious, and she’s a mother who’s absolutely terrified beyond all belief yet she just doesn’t give up.

Yep, there are the tropes, like the magical negro and the psychic children tropes, but Kubrick plays them well. Besides, the tormented author with writers’ block is possibly one of the oldest literary tropes in the box.

I’ve heard so many people go on and on about why this film is a pinnacle of its art, and I can see why. Everything holds together – the tension, the dialogue, the characterisation. I’ll be honest and say it’s not my sort of film because I’m a shallow creature with simple tastes for nubile androgynous elves, but I watched it from start to finish without even getting distracted by my social media feeds because it was simply perfection. The horror is at times subtle, be it the growing sense of menace of a toxic environment or it’s overt, shocking in the flashes of atrocities that Kubrick depicts. (Let me not remember that hotel in Ireland where I had to hang my bedspread over the multiple mirrors before I could get to sleep.)

I’m also aware that this film has been picked apart to death by film aficionados who’ve read all sorts of meaning into things, and that in itself is a fascinating topic to delve into if you’ve got time to waste. Go trawl YouTube if you number among the idly curious. And if you’re a sad old fart like me who waited until her late-30s to see this film… I’m just going to shake my head at you. Watch this fucking film. Seriously.

No. I haven't read the fucking book yet. I'll get there. When I'm 50.

I have a terrible admission to make – but better late than never, amiright? I only watched The Shining for the first time this year. Yes. I’ve been lurking around on this planet for more than 30 years and I’d NEVER EVER EVER watched this masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick.

I have a terrible admission to make – but better late than never, amiright? I only watched The Shining for the first time this year. Yes. I’ve been lurking around on this planet for more than 30 years and I’d NEVER EVER EVER watched this masterpiece by Stanley Kubrick.Also, I absolutely loathe Jack Nicholson. I don’t know what it is about him – his face, his voice. I agree he’s a fantastic actor but he makes my flesh crawl and he was perfect for this role as Jack Torrance, the author who simply cannot get into his novel. The true star of this film is his long-suffering wife Wendy, who somehow keeps it all together when everyone else around her is going completely stark-raving bonkers. Little Danny’s premonitions are creepy, but even creepier still is the location.

Kudos to the set dressers and builders – the interiors of the Overlook Hotel are phenomenal and a fitting tribute to all that is awful about late-1970s décor. Kubrick manages to make me feel horrifically claustrophobic and paranoid all at once. Trapped like Jack and his family, we can only sit back and watch how Jack spirals into madness, and we know things aren’t going to end well. All the while poor, dear Wendy comes to realise she needs to get herself and her son out of this place – easier said than done when the inevitable blizzard cuts them off from the rest of this world. And she’s resilient, tenacious, and she’s a mother who’s absolutely terrified beyond all belief yet she just doesn’t give up.

Yep, there are the tropes, like the magical negro and the psychic children tropes, but Kubrick plays them well. Besides, the tormented author with writers’ block is possibly one of the oldest literary tropes in the box.

I’ve heard so many people go on and on about why this film is a pinnacle of its art, and I can see why. Everything holds together – the tension, the dialogue, the characterisation. I’ll be honest and say it’s not my sort of film because I’m a shallow creature with simple tastes for nubile androgynous elves, but I watched it from start to finish without even getting distracted by my social media feeds because it was simply perfection. The horror is at times subtle, be it the growing sense of menace of a toxic environment or it’s overt, shocking in the flashes of atrocities that Kubrick depicts. (Let me not remember that hotel in Ireland where I had to hang my bedspread over the multiple mirrors before I could get to sleep.)

I’m also aware that this film has been picked apart to death by film aficionados who’ve read all sorts of meaning into things, and that in itself is a fascinating topic to delve into if you’ve got time to waste. Go trawl YouTube if you number among the idly curious. And if you’re a sad old fart like me who waited until her late-30s to see this film… I’m just going to shake my head at you. Watch this fucking film. Seriously.

No. I haven't read the fucking book yet. I'll get there. When I'm 50.

Published on July 28, 2016 11:18

July 27, 2016

What We Do in the Shadows (2014) #reviews

A documentary team films the lives of a group of vampires for a few months. The vampires share a house in Wellington, New Zealand. Turns out vampires have their own domestic problems too.

It’s not often that I’ll laugh until my sides hurt, but directors Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi pushed all the right buttons for me with their mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows – and I dig vampires, as some of you may already know. I can compare this to The League of Gentlemen meets the vampire genre as we get to know Viago, Vladislav, Deacon, and Petyr, who cohabit in the prerequisite crumbling domicile in the midst of a Wellington suburb in New Zealand. Add their minion (and mum) Jackie to the mix (who clearly has ambitions to be undead) whose work includes procuring and disposing of suitable victims on the off-chance that they'll turn her. (Hint, they're far too comfortable with the status quo.)

It’s not often that I’ll laugh until my sides hurt, but directors Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi pushed all the right buttons for me with their mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows – and I dig vampires, as some of you may already know. I can compare this to The League of Gentlemen meets the vampire genre as we get to know Viago, Vladislav, Deacon, and Petyr, who cohabit in the prerequisite crumbling domicile in the midst of a Wellington suburb in New Zealand. Add their minion (and mum) Jackie to the mix (who clearly has ambitions to be undead) whose work includes procuring and disposing of suitable victims on the off-chance that they'll turn her. (Hint, they're far too comfortable with the status quo.)

Of course their idyll isn’t long-lived, and when one of the vampires accidentally creates a new (modern) vampire, the pecking order is thrown out of kilter, with side-splittingly hilarious consequences. (And of course there are many laughs at the Tweelighters’ expense.)

Okay, the gags are really silly, but if you know your tropes, you’ll end up with a belly ache, like I did. Especially when the werewolves entered stage right… Honestly, I don’t know when last I’d seen a film that was just so much fun (thank you, Netflix). And yeah, this is one I’ll watch again some time in the future. Considering how stolid and unwieldy most of the mainstream cinema fare is nowadays (especially from the US), this is a waft of bloody good (and gory) fun.

There’s not much else to say, other than the fact that the characters were incredibly well put together, and the humour is spot on. So many cringe-worthy awkward, and irreverent situations, but oh so worth it.

It’s not often that I’ll laugh until my sides hurt, but directors Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi pushed all the right buttons for me with their mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows – and I dig vampires, as some of you may already know. I can compare this to The League of Gentlemen meets the vampire genre as we get to know Viago, Vladislav, Deacon, and Petyr, who cohabit in the prerequisite crumbling domicile in the midst of a Wellington suburb in New Zealand. Add their minion (and mum) Jackie to the mix (who clearly has ambitions to be undead) whose work includes procuring and disposing of suitable victims on the off-chance that they'll turn her. (Hint, they're far too comfortable with the status quo.)

It’s not often that I’ll laugh until my sides hurt, but directors Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi pushed all the right buttons for me with their mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows – and I dig vampires, as some of you may already know. I can compare this to The League of Gentlemen meets the vampire genre as we get to know Viago, Vladislav, Deacon, and Petyr, who cohabit in the prerequisite crumbling domicile in the midst of a Wellington suburb in New Zealand. Add their minion (and mum) Jackie to the mix (who clearly has ambitions to be undead) whose work includes procuring and disposing of suitable victims on the off-chance that they'll turn her. (Hint, they're far too comfortable with the status quo.)Of course their idyll isn’t long-lived, and when one of the vampires accidentally creates a new (modern) vampire, the pecking order is thrown out of kilter, with side-splittingly hilarious consequences. (And of course there are many laughs at the Tweelighters’ expense.)

Okay, the gags are really silly, but if you know your tropes, you’ll end up with a belly ache, like I did. Especially when the werewolves entered stage right… Honestly, I don’t know when last I’d seen a film that was just so much fun (thank you, Netflix). And yeah, this is one I’ll watch again some time in the future. Considering how stolid and unwieldy most of the mainstream cinema fare is nowadays (especially from the US), this is a waft of bloody good (and gory) fun.

There’s not much else to say, other than the fact that the characters were incredibly well put together, and the humour is spot on. So many cringe-worthy awkward, and irreverent situations, but oh so worth it.

Published on July 27, 2016 11:40

July 26, 2016

Playing the Long Game #writerslife

A question I sometimes get is, “Oh, wow, you’ve written so many books. You must have made lots of money.”

At which point, I laugh and laugh … and then whimper slightly. Authors are not rich. Those who are, are the exception, not the rule.

At which point, I laugh and laugh … and then whimper slightly. Authors are not rich. Those who are, are the exception, not the rule.

Let’s say it again: Rich authors are the exception, not the rule. Now, write that in nice red ink and stick it above your workspace.

Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away, I ended up in an email exchange with John Everson. We were both hanging around the same Yahoo list during the mid-2000s, when FB was merely a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg's eye, and I remember being terribly impressed with the fact that he’d been published and where he was at the start of what appeared to be a promising career. He still warned me that it’s a lot of hard work without any guarantees, and I thought, “Yup, I’m up for this. I’ll make it. I'm awesome. The sun shines out of my arse.”

Yet here I am. I’ve published a bunch of books. None of them are best-sellers, and I make more money editing other people’s work than with my own writing.

But what do we mean by successful author? What do we mean when we say we’ve “made it”?

Good questions.

If you’re doing this under the assumption that you’re going to earn wads of cash, you might do better simply investing in guaranteed schemes or buying property. Publishing novels is a lot like gambling. Actually, who’m I kidding? It is gambling. You simply cannot guarantee whether readers will glomp onto your work. No one could predict that Harry Potter, Twilight or Fifty Shades of Grey, The Hunger Games or even adult colouring books would be the phenomena that they’ve turned out to be. But they are.

Hundreds of authors have tried to follow in these footsteps, to varying degrees of success. And I predict, that by the time the majority of those attempting to ride the coattails of the success stories get their novels out there, the wave will have passed.

(There’s a reason why I don’t write YA dystopias. Though I do admit that the genre itself has been surprisingly resilient despite me watching out for the Next Big Thing to take off.)

If you’re talking about financial success, then you need to write the more popular genres. Which means you’re going to look at erotic romance, crime/mystery, religious/inspirational, and fantasy … with horror lagging behind all of these… And it means you’ll have to immerse yourself in the genre you want to write so that you’re aware of the tropes. Readers are not stupid. They can tell the moment an author’s heart is not in the genre they’re writing and, nope, they’re not going to buy it if your offering is a lukewarm spinoff.

Some of the hardest-working authors I’ve ever met write in the erotic romance genre. These folks write a book every 2-3 months, with 6-8 releases a year in what is a highly competitive market with a huge turnover of newly published works every week. Their readers are voracious, and yet if an author misses a step, their name quickly sinks to the bottom of the pile. The ones who earn six-digit figures put in eight or more hours a day of writing, revising and promotion. It’s a huge industry, and frankly, I have to be honest with myself, I don’t have the stamina for it. I don’t have the love of this particular genre to push myself in this direction. The successful authors treat this with the same seriousness that they do any nine-to-five career. I don’t want this on the off-chance that I might make a financial “success” of it.

And yet ... Work ethic and talent most certainly help, but they’re no guarantee.

If you’re writing because you want people to tell you how amazeballs your stories are, think again. It’s easy to publish a novel these days. But getting people to read your work is difficult. Then getting them to leave reviews or ratings (those all-important algorithms Amazon loves so much before your book starts showing up in any promotion) is even more difficult. It simply doesn’t occur to many readers that they should leave reviews. Or they’re just not in the mood. Or they have better things to do. Your books don’t accimagically sell themselves, and only a select few (or incredibly savvy) ever make it onto the shelves of brick-and-mortar stores.

(Here’s a hint: go look at the SFF section at your local bookshop. Notice something? Yeah, it’s still mostly the same old names we’ve seen there for the past 10-20 years… The Hobbs, the GRRMs, the Tolkiens, the Jordans, the Canavans…)

The likelihood of you getting your small press or self-published book onto the shelves of your local bookstore are slim to none. Most of your sales will be from your ebooks. Which folks will only buy if they happen to stumble onto the book via a review or a mention on social media.

So, why are you writing?

I’ll tell you why I write. Maybe my story will resonate (and I'd love to hear yours – leave a comment below in the comments section). I’m playing the long game. I’ve decided I don’t want to wait until I become famous to write the kinds of books I enjoy reading. Unfortunately, many of my literary heroes are not runaway mainstream successes. By the same measure, the stories I tell are not mainstream. My readership is niche, but I love that niche – of rich, nuanced and slowly unfolding fantasy where there the conflict is often subtle and it’s not immediately possible to tell who’s the antagonist. I look to the writings of Storm Constantine, Neil Gaiman, Robin Hobb, Ursula Le Guin, Poppy Z Brite, CJ Cherryh and numerous others, and I express myself in a synthesis of what I love about their styles. Some of these authors you may have heard of. Others, perhaps not. But whether you have, doesn’t matter to me.

The point is I have stories I want to tell. I am a storyteller.

My rewards are subtle: It’s when one of my literary heroes tells me that she loves my voice. Or when I’ve read at an event, and a young boy walks up to me and tells me that my writing reminds him of Neil Gaiman’s. Or it’s when a reader writes to tell me that I made her forget to milk her goats. Or, it's that flash of inspiration when I pause in what I'm doing to daydream on a new idea then see its potential.

I write my own worlds, but I also write fiction that I cannot sell; my fanfiction often gives me so much pleasure because the response I have from readers is immediate and passionate. And for the same reasons, I read the fics of others, and I experience the same enthusiasm for our favourite worlds.

And my original fiction meets the fanfiction halfway, because I’ve written for existing intellectual properties in an official capacity, and it’s been awesome and financially rewarding.

I will close by sharing also that I’ve learnt to value my writing. I don’t submit to just any market that is out there. I don’t often give away my works for free. I always craft to my utmost ability then submit to the best markets. And, if for whatever reason these works doesn’t sell, I’ll later compile them into an anthology or release via my Patreon page. I aim high, for quality, not quantity.

I don’t make my living writing, though there are some opportunities that do pay well. Life is short, nasty and brutish, and I want to enjoy my writing while I’m alive. It’s not so much a stress of if a story will be published, but rather when, and how. If I value my art, and don’t sell it short, it means that there’s a better chance that others may cherish it too.

Am I a success? If you mean by am I writing the stories that I love reading, then my resounding answer is yes. I am a success.

Bio: After surviving a decade in the trenches of newspaper publishing, where she fought against the abuse of the English language, Nerine Dorman is now a freelance editor and designer who is passionate about words that not only sound good, but look damned good too. She’s also written a few books. You can stalk her on Twitter or, even better, support her authorly aspirations via Patreon. If you’re feeling particularly brave, and would like to inquire about her editing rates, you can email her at nerinedorman@gmail.com

At which point, I laugh and laugh … and then whimper slightly. Authors are not rich. Those who are, are the exception, not the rule.

At which point, I laugh and laugh … and then whimper slightly. Authors are not rich. Those who are, are the exception, not the rule.Let’s say it again: Rich authors are the exception, not the rule. Now, write that in nice red ink and stick it above your workspace.

Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away, I ended up in an email exchange with John Everson. We were both hanging around the same Yahoo list during the mid-2000s, when FB was merely a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg's eye, and I remember being terribly impressed with the fact that he’d been published and where he was at the start of what appeared to be a promising career. He still warned me that it’s a lot of hard work without any guarantees, and I thought, “Yup, I’m up for this. I’ll make it. I'm awesome. The sun shines out of my arse.”

Yet here I am. I’ve published a bunch of books. None of them are best-sellers, and I make more money editing other people’s work than with my own writing.

But what do we mean by successful author? What do we mean when we say we’ve “made it”?

Good questions.

If you’re doing this under the assumption that you’re going to earn wads of cash, you might do better simply investing in guaranteed schemes or buying property. Publishing novels is a lot like gambling. Actually, who’m I kidding? It is gambling. You simply cannot guarantee whether readers will glomp onto your work. No one could predict that Harry Potter, Twilight or Fifty Shades of Grey, The Hunger Games or even adult colouring books would be the phenomena that they’ve turned out to be. But they are.

Hundreds of authors have tried to follow in these footsteps, to varying degrees of success. And I predict, that by the time the majority of those attempting to ride the coattails of the success stories get their novels out there, the wave will have passed.

(There’s a reason why I don’t write YA dystopias. Though I do admit that the genre itself has been surprisingly resilient despite me watching out for the Next Big Thing to take off.)

If you’re talking about financial success, then you need to write the more popular genres. Which means you’re going to look at erotic romance, crime/mystery, religious/inspirational, and fantasy … with horror lagging behind all of these… And it means you’ll have to immerse yourself in the genre you want to write so that you’re aware of the tropes. Readers are not stupid. They can tell the moment an author’s heart is not in the genre they’re writing and, nope, they’re not going to buy it if your offering is a lukewarm spinoff.

Some of the hardest-working authors I’ve ever met write in the erotic romance genre. These folks write a book every 2-3 months, with 6-8 releases a year in what is a highly competitive market with a huge turnover of newly published works every week. Their readers are voracious, and yet if an author misses a step, their name quickly sinks to the bottom of the pile. The ones who earn six-digit figures put in eight or more hours a day of writing, revising and promotion. It’s a huge industry, and frankly, I have to be honest with myself, I don’t have the stamina for it. I don’t have the love of this particular genre to push myself in this direction. The successful authors treat this with the same seriousness that they do any nine-to-five career. I don’t want this on the off-chance that I might make a financial “success” of it.

And yet ... Work ethic and talent most certainly help, but they’re no guarantee.

If you’re writing because you want people to tell you how amazeballs your stories are, think again. It’s easy to publish a novel these days. But getting people to read your work is difficult. Then getting them to leave reviews or ratings (those all-important algorithms Amazon loves so much before your book starts showing up in any promotion) is even more difficult. It simply doesn’t occur to many readers that they should leave reviews. Or they’re just not in the mood. Or they have better things to do. Your books don’t accimagically sell themselves, and only a select few (or incredibly savvy) ever make it onto the shelves of brick-and-mortar stores.

(Here’s a hint: go look at the SFF section at your local bookshop. Notice something? Yeah, it’s still mostly the same old names we’ve seen there for the past 10-20 years… The Hobbs, the GRRMs, the Tolkiens, the Jordans, the Canavans…)

The likelihood of you getting your small press or self-published book onto the shelves of your local bookstore are slim to none. Most of your sales will be from your ebooks. Which folks will only buy if they happen to stumble onto the book via a review or a mention on social media.

So, why are you writing?

I’ll tell you why I write. Maybe my story will resonate (and I'd love to hear yours – leave a comment below in the comments section). I’m playing the long game. I’ve decided I don’t want to wait until I become famous to write the kinds of books I enjoy reading. Unfortunately, many of my literary heroes are not runaway mainstream successes. By the same measure, the stories I tell are not mainstream. My readership is niche, but I love that niche – of rich, nuanced and slowly unfolding fantasy where there the conflict is often subtle and it’s not immediately possible to tell who’s the antagonist. I look to the writings of Storm Constantine, Neil Gaiman, Robin Hobb, Ursula Le Guin, Poppy Z Brite, CJ Cherryh and numerous others, and I express myself in a synthesis of what I love about their styles. Some of these authors you may have heard of. Others, perhaps not. But whether you have, doesn’t matter to me.

The point is I have stories I want to tell. I am a storyteller.

My rewards are subtle: It’s when one of my literary heroes tells me that she loves my voice. Or when I’ve read at an event, and a young boy walks up to me and tells me that my writing reminds him of Neil Gaiman’s. Or it’s when a reader writes to tell me that I made her forget to milk her goats. Or, it's that flash of inspiration when I pause in what I'm doing to daydream on a new idea then see its potential.

I write my own worlds, but I also write fiction that I cannot sell; my fanfiction often gives me so much pleasure because the response I have from readers is immediate and passionate. And for the same reasons, I read the fics of others, and I experience the same enthusiasm for our favourite worlds.

And my original fiction meets the fanfiction halfway, because I’ve written for existing intellectual properties in an official capacity, and it’s been awesome and financially rewarding.

I will close by sharing also that I’ve learnt to value my writing. I don’t submit to just any market that is out there. I don’t often give away my works for free. I always craft to my utmost ability then submit to the best markets. And, if for whatever reason these works doesn’t sell, I’ll later compile them into an anthology or release via my Patreon page. I aim high, for quality, not quantity.

I don’t make my living writing, though there are some opportunities that do pay well. Life is short, nasty and brutish, and I want to enjoy my writing while I’m alive. It’s not so much a stress of if a story will be published, but rather when, and how. If I value my art, and don’t sell it short, it means that there’s a better chance that others may cherish it too.

Am I a success? If you mean by am I writing the stories that I love reading, then my resounding answer is yes. I am a success.

Bio: After surviving a decade in the trenches of newspaper publishing, where she fought against the abuse of the English language, Nerine Dorman is now a freelance editor and designer who is passionate about words that not only sound good, but look damned good too. She’s also written a few books. You can stalk her on Twitter or, even better, support her authorly aspirations via Patreon. If you’re feeling particularly brave, and would like to inquire about her editing rates, you can email her at nerinedorman@gmail.com

Published on July 26, 2016 07:24

July 24, 2016

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) #reviews

Archaeologist and adventurer Indiana Jones is hired by the U.S. government to find the Ark of the Covenant before the Nazis.

The first time I encountered anything about this film was via my then best friend Evan, when we were both six. There were collectible sticker books and he had one for Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was very envious of him because he came from the US and had all the Star Wars figurines.

The first time I encountered anything about this film was via my then best friend Evan, when we were both six. There were collectible sticker books and he had one for Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was very envious of him because he came from the US and had all the Star Wars figurines.

So, yes, my viewing of this film is very much mired in nostalgia for my childhood, and it formed part of my mission to watch all the Indiana Jones films in a set.

Raiders is the first of the Indiana Jones films and shows Indy going up against the best movie villains ever – the Nazis. The film draws on the Nazi fascination with the occult, and in this scenario the McGuffin is the fabled Ark of the Covenant that has been lost for millennia. That is, until the Nazis cotton on to the fact that it may have been buried in Egypt.

Indy does what Indy does best, and embarks on a treasure hunt that leads him to the rather fabulous Marion Ravenwood (the daughter of one his archaeologist buddies) and the two set off to Egypt to hunt for the treasure. Of course the ominous Nazi colonel is hot on their heels and Indy and co. enjoy a series of narrow squeaks in typical Indy fashion, aided and abetted by his somewhat eclectic friends.

There aren't many strong female characters in this film. There is Marion. But she's hardly the Damsel, which makes up for it. (But I can already hear the SJWs winding themselves up into a frothy.) But I like Marion. She punches hard. She's clever. She's tough. She's capable. From time to time she *does* need rescuing but then again, Indy's constantly getting into scrapes himself.

Everyone gets their just deserts, and typically, those who are greedy and overly ambitious in a selfish fashion come off second best. In the end. Cultural representations remain simplistic as per Hollywood but then again, don't forget the era within which this film was made, when being PC wasn't exactly high up on producers' agendas. We had quite a lively discussion about the problematic elements in the film – and whether shoehorning representation now would be forced or not – but in the end I agree to leave the film be for what it is. This is a swashbuckling, tongue-in-cheek action film and it's fun. (And it's most certainly inspired video games like Tomb Raider and Uncharted.) I watch films like this because I want to be entertained. Overthinking it ruins the enjoyment, and the devil alone knows there's enough BS in the world.

The first time I encountered anything about this film was via my then best friend Evan, when we were both six. There were collectible sticker books and he had one for Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was very envious of him because he came from the US and had all the Star Wars figurines.

The first time I encountered anything about this film was via my then best friend Evan, when we were both six. There were collectible sticker books and he had one for Raiders of the Lost Ark. I was very envious of him because he came from the US and had all the Star Wars figurines.So, yes, my viewing of this film is very much mired in nostalgia for my childhood, and it formed part of my mission to watch all the Indiana Jones films in a set.

Raiders is the first of the Indiana Jones films and shows Indy going up against the best movie villains ever – the Nazis. The film draws on the Nazi fascination with the occult, and in this scenario the McGuffin is the fabled Ark of the Covenant that has been lost for millennia. That is, until the Nazis cotton on to the fact that it may have been buried in Egypt.

Indy does what Indy does best, and embarks on a treasure hunt that leads him to the rather fabulous Marion Ravenwood (the daughter of one his archaeologist buddies) and the two set off to Egypt to hunt for the treasure. Of course the ominous Nazi colonel is hot on their heels and Indy and co. enjoy a series of narrow squeaks in typical Indy fashion, aided and abetted by his somewhat eclectic friends.

There aren't many strong female characters in this film. There is Marion. But she's hardly the Damsel, which makes up for it. (But I can already hear the SJWs winding themselves up into a frothy.) But I like Marion. She punches hard. She's clever. She's tough. She's capable. From time to time she *does* need rescuing but then again, Indy's constantly getting into scrapes himself.

Everyone gets their just deserts, and typically, those who are greedy and overly ambitious in a selfish fashion come off second best. In the end. Cultural representations remain simplistic as per Hollywood but then again, don't forget the era within which this film was made, when being PC wasn't exactly high up on producers' agendas. We had quite a lively discussion about the problematic elements in the film – and whether shoehorning representation now would be forced or not – but in the end I agree to leave the film be for what it is. This is a swashbuckling, tongue-in-cheek action film and it's fun. (And it's most certainly inspired video games like Tomb Raider and Uncharted.) I watch films like this because I want to be entertained. Overthinking it ruins the enjoyment, and the devil alone knows there's enough BS in the world.

Published on July 24, 2016 02:46

July 23, 2016

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) #review

A skirmish in Shanghai puts archaeologist Indiana Jones, his partner Short Round and singer Willie Scott crossing paths with an Indian village desperate to reclaim a rock stolen by a secret cult beneath the catacombs of an ancient palace.

I was six when my sister dragged me off to the cinema to watch Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (directed by Steven Spielberg). I’m sorry to report that I spent nearly ¾ of the film with my back to the screen. I was petrified, and after that I had nightmares about evil priests in horned headdresses who tried to haul my heart out of my ribcage with their bare hands.

I was six when my sister dragged me off to the cinema to watch Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (directed by Steven Spielberg). I’m sorry to report that I spent nearly ¾ of the film with my back to the screen. I was petrified, and after that I had nightmares about evil priests in horned headdresses who tried to haul my heart out of my ribcage with their bare hands.

Yet over the years this has been one of those films that I have rewatched several times (I’ve lost count), and as I’ve grown older, I’ve enjoyed Temple of Doom, because the Indiana Jones films are somewhat silly yet incredible fun. And, of course, because Harrison Ford makes my heart beat a little faster now that I’m a big person.

Okay, I lie, I kinda never really grew up. I’m only pretending to be a big person.

But I digress.

The Indiana Jones films hark from that glorious, pulpy era of Hollywood action heroes. They don’t take themselves too seriously, and combine hair-raising stunts with equal doses of humour. And, of course, SFX that have dated horribly. But that’s okay, because I often feel that contemporary cinema relies too heavily on the CGI to make up for poor writing and cinematography.

Viewed through a contemporary, regressive left lens, the Indiana Jones films can probably be regarded as problematic with the portrayals of gender and race, but they inhabit such a fond, nostalgic place in my childhood, when such concerns weren’t even discussed, that I’m not going to waste my energy. I’m pretty sure there are plenty of SJWs who’re going to froth and have already done so at great length.

Indiana Jones is one of my favourite characters. He’s got the brawn where it counts, but he’s a professor – the ultimate in geeks – and a lady’s man. And he can crack a one-liner like he cracks his trademark whip. We meet him in Shanghai, where a deal goes wrong, and he and the singer Willie Scott and intrepid pint-sized sidekick Short Round end up in India. From there they get dragged into a quest to retrieve a village’s sacred stones where they run into an evil Kali cult complete with human sacrifice. In defeating an evil priest and retrieving the sacred stones, they also free the village’s children, and everyone goes merrily on their way. Oh, and let's not forget the grossest dinner party ever, that involves monkey brain soup with floating eyeballs, and a main dish that features baby snakes wriggling out of a steaming cooked momma snake. That's after the bugs for starters – this elicited a huge eewwwwwww from six-year-old Nerine.

This film is all about the action and adventure. The bad guys are really bad, greedy and ambitious. Indy is no less ambitious, but his motives are more altruistic – he seeks treasure for his university (how noble) so that they can be preserved for posterity.